Abstract

Cognitive operations are thought to emerge from dynamic interactions between spatially distinct brain areas. Synchronization of oscillations has been proposed to regulate these interactions, but we do not know whether this large-scale synchronization can respond rapidly to changing cognitive demands. Here we show that as task demands change during a trial, multiple distinct networks are dynamically formed and reformed via oscillatory synchronization. Distinct frequency-coupled networks were rapidly formed to process reward value, maintain information in visual working memory, and deploy visual attention. Strong single-trial correlations showed that networks formed even before the presentation of imperative stimuli could predict the strength of subsequent networks, as well as the speed and accuracy of behavioral responses seconds later. These frequency-coupled networks better predicted single-trial behavior than either local oscillations or event-related potentials. Our findings demonstrate the rapid reorganization of networks formed by dynamic activity in response to changing task demands within a trial.

Keywords: cross-frequency coupling, synchrony, reward, visual working memory, visual attention

INTRODUCTION

Goal-directed behavior arises from cognitive operations carried out by networks of spatially distributed brain areas, but the orchestration of different networks as a complex task unfolds and cognitive demands change remains a mystery. Oscillatory synchronization has been proposed to dynamically establish large-scale networks among brain areas (Canolty & Knight, 2010; Engel, Fries, & Singer, 2001; Friston, 1997; Salinas & Sejnowski, 2001; Varela, Lachaux, Rodriguez, & Martinerie, 2001). However, the viability of these proposals depend upon whether these oscillatory networks can be rapidly formed, dissolved, and new networks formed as cognitive demands rapidly change in our constantly changing environments.

Our aim in the present study was to determine whether cortical synchronization coordinates the large-scale networks that carry out critical cognitive operations across multiple phases of a task, with the task placing different cognitive demands on subjects as each trial unfolds. Moreover, we sought to characterize the temporal-spatial structure and spectral properties of each identified network and provide behavioral evidence for the functional significance of each.

We had subjects perform a task in which the information that needed to be processed was different across the different epochs of each trial. As shown in Figure 1A, each trial began with a reward cue indicating the monetary value of the current trial. Next, a target cue was presented briefly so that subjects would have in memory the appropriate representations allowing search for that item in the final display. Finally, a complex scene was presented in which subjects needed to determine if the target was present among distractors. The three phases of this experimental design required subjects to process the reward signal, instantiate a memory representation of the upcoming target, and then process the visual scene by guiding visual attention to the target ending with the behavioral response. We utilized cross-frequency coupling analyses of the oscillations of subject’s electroencephalogram (EEG) and inverse source reconstruction modeling to examine both the large-scale network interactions and their potential neuronal sources that support the processing of the different types of information across the epochs of each trial. We hypothesized that the oscillatory synchronization of the human brain should coordinate different large-scale, network-level mechanisms to perform these different operations (Canolty & Knight, 2010; Engel et al., 2001; Friston, 1997; Salinas & Sejnowski, 2001; Varela et al., 2001). That is, the network relevant to each cognitive operation should form and dissolve through dynamically regulating the strength of functional connectivity between brain areas via oscillatory synchronization or coupling (i.e., fast rhythmic temporal correlations of neuronal activity). If we can identify such synchronizing networks, then, is it possible to use our cross-frequency coupling measures of functional connectivity strength to predict patterns of subsequent network activity and behavior as subjects search cluttered visual scenes for the target objects?

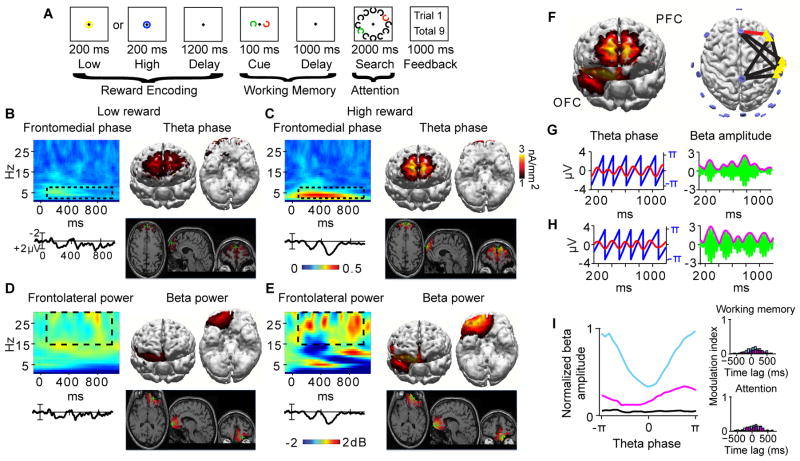

Figure 1.

Task and the oscillations, source estimates, and inter-regional synchrony of reward encoding. (A) Subjects fixate a central point for the duration of the trial. A blue or yellow circle signaled whether the trial was low or high reward. The task-relevant object in the cue array (red or green Landolt-C) signaled the shape of the target in the search array. Feedback was given at the end of each trial. Grand average reward cue-locked frontomedial (Fz) phase locking (B–C) and right frontolateral (F4) power (D–E) for low and high reward. Insets show ERPs. Current density estimates are projected onto the cortical surface of 3D reconstructions and MRI slices intersecting the location of greatest density of current flow (i.e., warmer colors/crosshair) for theta phase locking (3–6 Hz, B–C) and beta power (15–30 Hz, D–E), 100–1000 ms following low and high reward. (F) Combined current density results show activations in orbitofrontal and dorsomedial prefrontal cortices. Significant high reward theta phase (without triangle) beta amplitude (with triangle) coupling (red line, q = 0.01; black line, q = 0.05). Grand average reward cue-locked frontomedial theta rhythm (red) with overlaying phase angles (blue), and right frontolateral beta rhythm (green) with overlaying amplitude envelope (magenta) for low (G) and high reward (H). (I) Beta amplitudes sorted according to theta phase in π/30 intervals, for low reward (magenta), high reward (blue), and a surrogate control (black). Insets show the absence of reward cue-locked inter-regional cross-frequency coupling using the frequency bands and electrode locations critical for forming the working memory and attention networks (Figs. 2–3).

METHODS

Subjects and stimuli

Thirty paid volunteers (18–32 years of age, normal or corrected acuity and color vision) provided informed consent of procedures approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board.

Stimuli were presented on a gray background (54.3 cd/m2) at a viewing distance of 114 cm. A black fixation cross (<0.01 cd/m2, 0.4° × 0.4° of visual angle) was visible throughout each trial. Reward stimuli were outlined circles (0.88° diameter, 0.13° thick) presented to the center of the monitor. Low and high rewards were distinguished by color (blue x = 0.146, y = 0.720, 6.41 cd/m2; yellow x = 0.408, y = 0.505, 54.1 cd/m2), with the assignment of color to reward value counterbalanced across subjects.

The elements in the cue and search arrays were Landolt-C stimuli (0.88° diameter, 0.13° thick, 0.22° gap width), of eight possible orientations (0°, 22.5°, 45°, 67.5°, 90°, 112.5°, 135°, 157.5°), one of which was green (x = 0.281, y = 0.593, 45.3cd/m2) and the other red (x = 0.612, y = 0.333, 15.1 cd/m2). The task-relevant color of the cue stimulus was determined prior to the start of each experiment, counterbalanced across subjects. Each cue stimulus was presented 2.2° to the left or right of the center of the monitor. The search array contained one red, one green and 10 black distractor Landolt-C stimuli (<0.01 cd/m2) arranged similar to the number locations on a clock face (centered 4.4° from the middle of the monitor) (see Fig. 1A). The target orientation could only appear in the task-relevant color.

Task and procedure

Each trial began with the presentation of the fixation cross for 1200–1600 ms (randomly jittered using a rectangular distribution). The reward-cue stimulus was presented next for 200 ms, followed by a 1200-ms interval. Next, the target-cue stimuli were presented for 100 ms, followed by a 1000-ms interval. We then presented the search array for 2000 ms. The final stimulus event of each trial was feedback displaying the current and total cents earned. On low-reward trials, subjects earned $0.01 for a correct response within 2000 ms, and no penalty for an incorrect or missed response, whereas on high-reward trials subjects earned $0.05 for a correct response, and were penalized $0.50 for an incorrect response, comparable to the reward schedule used in previous research (Della Libera & Chelazzi, 2006, 2009). Subjects were aware that bonus money earned for fast and accurate performance added to their hourly compensation ($10). Because error responses were infrequent (8% of trials across subjects), the penalty for incorrect, high-reward trials rarely occurred. However, to verify that the effects we observed were due to the reward payoffs and not the avoidance of losses, we ran half of the subjects (i.e., 15) through the same experiment except that no penalties existed and only differential reward occurred for low versus high-reward trials (1 versus 5 cents gains for correct responses within the 2 second window). The behavioral results, event-related potentials, and patterns of oscillatory activity did not significantly differ between these versions of the experiment so their data were collapsed.

The target cue stimulus remained the same color, orientation, and location throughout each run of 7 trials. The target presented during visual search matched the orientation of the task-relevant cue on half the total number of trials. The cued target orientation and target presence (present or absent) were randomly selected on each trial for all experiments. Target location was randomized on each trial. 75% of all trials were preceded by low-reward cues with the rest having high-reward cues, consistent with the reward structure of other studies examining reward effects on attention (e.g., Della Libera & Chelazzi, 2006, 2009; Hickey, Chelazzi, & Theeuwes, 2010; Serences, 2008). To avoid any effects due to trial number differences across the reward manipulation, the number of trials was matched across trial types by excluding randomly selected low-reward trials. Participants were instructed to respond to the search array by pressing one button on a handheld gamepad (Logitech Precision) to indicate target presence and a different button to indicate target absence, using the thumb of their right hand, giving equal importance to speed and accuracy. Each participant performed 2 blocks of 420 trials.

EEG was recorded (250 Hz sampling rate; 0.01–100 Hz band pass filter) using an SA Instrumentation amplifier and 21 electrodes (Electro-Cap International), including 3 midline (Fz, Cz, Pz), 7 lateral pairs (F3/F4, C3/C4, P3/P4, PO3/PO4, T3/T4, T5/T6, O1/O2), and 2 nonstandard sites: OL (midway between O1 and T5) and OR (midway between O2 and T6), arrayed according to the International 10–20 System. Signals were right mastoid referenced and re-referenced offline to the average of the left and the right mastoids (Luck, 2005). Horizontal and vertical eye positions were monitored by recording the electro-oculogram from bipolar electrodes located at the outer canthus of each eye, and above and below the orbit of the left eye, respectively. We used a two-step ocular artifact rejection method (Woodman & Luck, 2003) that resulted in the replacement of two subjects due to eye movement artifacts on more than 25% of trials. Trials accompanied by incorrect behavioral responses or ocular or myogenic artifacts were excluded from the averages resulting in an average of 13.8% of trials rejected per subject.

Data analysis

Within electrode time frequency analyses were performed with a continuous Morlet wavelet transform using FieldTrip software (Oostenveld, Fries, Maris, & Schoffelen, 2011). The Morlet wavelet has a Gaussian envelop that is defined by a constant ratio ( ) and a wavelet duration (4σt), where f is the center frequency and . After obtaining complex time frequency data for every individual trial, these data were transformed into measures of within electrode cross trial phase locking and total power. We divided each complex data point by its corresponding magnitude, generating a new series of complex data where the phase angles are preserved, but the magnitudes are transformed to one (i.e., unit normalized). These magnitude-normalized complex values were then averaged, yielding a measure of cross trial phase locking for a particular frequency, time point, and electrode. A value of 0 in this measure represents an absence of phase synchronization across trials, whereas 1 indicates perfect phase alignment across trials. Similarly, following single trial EEG spectral decomposition, the magnitude lengths of the complex number vectors were extracted, squared, and averaged, yielding a measure of cross trial total power for a given frequency, time point, and electrode. Phase locking and power estimates were then computed from −200 to 1000 ms centered on the triggering event in 4 ms bins and from 2 to 30 Hz in 1 Hz bins. Baseline correction, centered 100 – 200 ms before stimulus onset, involved dividing the values at each time point in the epoch by the baseline value and then taking the log10 transform of this quotient and multiplying it by 20, yielding values expressed in units of decibels (dB) (Delorme & Makeig, 2004). Consistent with previous work (e.g., Mazaheri & Jensen, 2008; van Dijk, Van der Werf, Mazaheri, Medendorp, & Jensen, 2010), the visual working memory and attention EEG responses were hemisphere specific as expected given the lateral presentation of task-relevant stimuli. As a result, activity from both left and right lateral electrodes was average based on the hemifield of stimulus presentation (i.e., contralateral versus ipsilateral).

All methods for detecting coupled oscillations rely on band pass filtering and the Hilbert transform (Penny, Duzel, Miller, & Ojemann, 2008). First, data from each electrode site were filtered using a two way, zero phase lag, finite impulse response filter to avoid phase distortion (i.e., eegfilt.m function in EEGLAB toolbox, see Delorme & Makeig, 2004). The Hilbert transform was then applied to each resulting time series, yielding a complex time series,

where ax[n] are the instantaneous amplitudes and φx[n] are the instantaneous phases. The phase time series φx contains values from −π to π radians with a cosine phase where 0 radians is the peak and π radians is the trough. Given our interest in the dependence between cross-frequency coupling changes and behavior, it was desirable to have a modulation index of phase-amplitude cross-frequency coupling, which would enable us to assess the magnitude of coupling, in addition to detecting its existence. We implemented the method employed by Lakatos et al. (2005), recommended by Tort, Komorowski, Eichenbaum, & Kopell (2010) and Canolty & Knight (2010) for these purposes. In brief, this approach involves identifying all data points whose low-frequency phases fall in one of the 60 phase intervals of width between −π and π. Mean high-frequency amplitudes of the respective data points were then assigned to each low-frequency phase interval.

We calculated the time lag cross correlation across trials using the squared amplitude envelopes between frequency bands (i.e., amplitude-amplitude cross-frequency coupling (Bruns, Eckhorn, Jokeit, & Ebner, 2000; Friston, 1997). The cross correlation function for time series xn and yn, n = 1, …, N, is defined as

where x̄ denotes the mean, σx denotes the variance, and τ denotes the time lag. The cross correlation function is essentially the inner product between two normalized signals which provides a measure of the linear synchronization between the two signals as a function of time lag. Its absolute value ranges from zero (no synchronization) to 1 (maximum synchronization) and it is symmetric (i.e., cxy (τ) = cyx (τ)). The cross correlation provides sensitive information on the time coupling and waveform similarity between the two signals (Quian Quiroga, 2009).

Inverse source modeling

Current density topographical analyses were performed in CURRY 6 (Compumedics Neuroscan, Singen, Germany). The interpolated Boundary Element Method (BEM) model (Fuchs, Drenckhahn, Wischmann, & Wagner, 1998) was derived from averaged magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data from the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI). It consisted of 9300 triangular meshes overall or 4656 nodes, which describe the smoothed inner skull (2286 nodes), the outer skull (1305 nodes), and the outside of the skin (1065 nodes). The mean triangle edge lengths (node distances) were 9mm (skin), 6.8mm (skull), and 5.1mm (brain compartment). Standard conductivity values for the three compartments were set to: skin = 0.33 S/m, skull = 0.0042 S/m, and brain = 0.33 S/m. The Standardized low resolution electromagnetic tomography (sLORETA) Weighted AccuRate minimum norm Method (SWARM) was estimated using sensor positions based on the International 10–20 System and a cortical surface obtained from a segmentation of the CURRY 6 individual reference brain. SWARM uses the methods of diagonally weighted minimum norm least squares (Dale & Sereno, 1993) and sLORETA (Pascual-Marqui, 2002) to compute a current density vector field (Wagner, Fuchs, & Kastner, 2007), resulting in values scaled in amperes (Am) for each 5.1 mm3 voxel in brain space. Although current density reconstructions can often provide a reasonable estimate of the actual pattern of activity generating the surface potentials, inverse source modeling carries with it several ambiguities and source estimates are not intended as strong claims about the location of neuronal generation.

Using all scalp electrodes, the reward network current density distributions were drawn from theta (3 – 7 Hz) and beta (15 – 30 Hz) reward cue related data, 100 – 1000 ms poststimulus onset. Similarly, the visual working memory current density distributions were drawn from theta (3 – 7 Hz) and alpha (8 – 13 Hz) target cue related data, 100 – 1000 ms poststimulus onset. The visual attention current density distributions were drawn from theta (3 – 7 Hz) and alpha (8 – 13 Hz) search array related data, 100 – 400 ms post array onset. Prior to our analyses, the lateralized visual working memory and attention responses were collapsed across left and right hemifield stimulus locations and averaged using a procedure that preserved the electrode location relative to the stimulus location. All contralateral current density activity was projected onto the right hemisphere of a 3D reconstruction of the cortical surface and all ipsilateral activity was projected onto the left hemisphere. That is, although current density activity is shown in Figures 2–3 as right lateralized, this activity contains trials in which both left and right visual field stimuli were presented. This same procedure was applied for the presentation of coupling topographies shown in Figures 2–3. The SWARM procedure was performed separately for imaginary and real time-frequency components and figures show the grand average SWARM results.

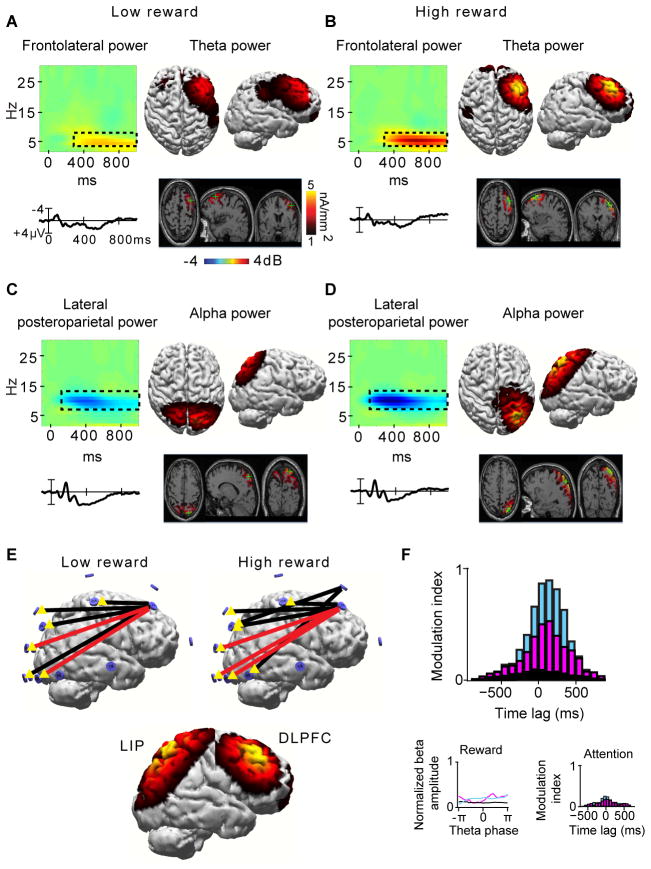

Figure 2.

The oscillations, source estimates, and inter-regional synchrony of visual working memory. Grand average target cue-locked frontolateral (F3/4, A–B) and lateral posteroparietal power (OL/R, C–D) contralateral to the remembered location of the target for low and high reward. Insets show ERPs. Current density estimates are projected onto the cortical surface of 3D reconstructions and MRI slices intersecting the location of greatest density of current flow (i.e., warmer colors/crosshair) for frontolateral theta (4–6 Hz, A–B) and lateral posteroparietal alpha (8–12 Hz, C–D), 100–1000 ms post-target cue. (E) Significant theta (without triangle) and alpha (with triangle) coupling (red line, q = 0.01; black line, q = 0.05) for low and high reward. Combined current density results show activations in lateral intraparietal and dorsolateral prefrontal cortices. Although both left and right visual field trials are included in all source models and coupling topographies, for visualization purposes all contralateral activity is projected onto right hemisphere. (F) Normalized cross correlation estimates between frontolateral theta and posterolateral alpha power envelopes for low reward (magenta), high reward (blue), and control (black). Insets show the absence of target cue-locked inter-regional cross-frequency coupling using the frequency bands and electrode locations forming the reward and attention networks (Figs. 1 and 3).

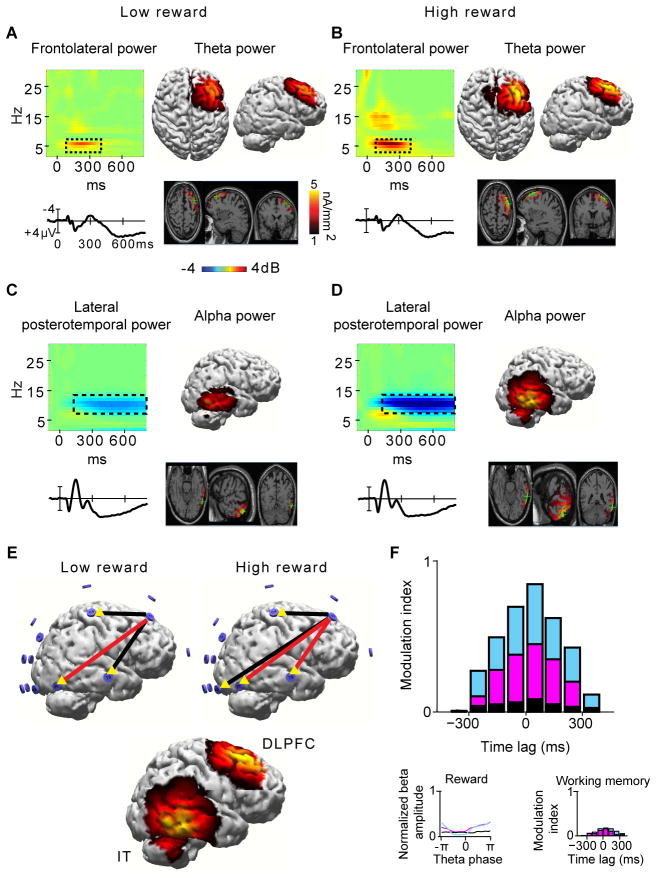

Figure 3.

The oscillations, source estimates, and inter-regional synchrony of attention. Grand average search array-locked frontolateral (F3/4, A–B) and lateral posterotemporal power (T5/6, C–D) contralateral to the remembered location of the target in the search array for low and high reward. Insets show ERPs. Current density estimates are projected onto the cortical surface of 3D reconstructions and MRI slices intersecting the location of greatest density of current flow (i.e., warmer colors/crosshair) for frontolateral theta (4–7 Hz, A–B) and lateral posterotemporal alpha (8–13 Hz, C–D), 100–400 ms post-search array. (E) Significant theta (without triangle) and alpha (with triangle) coupling (red line, q = 0.01; black line, q = 0.05) for low and high reward. Combined current density results show activations in inferior temporal and dorsolateral prefrontal cortices. Although both left and right visual field electrodes are included in all source models and coupling topographies, for visualization purposes all contralateral activity is projected onto right hemisphere. (F) Normalized cross correlation estimates between theta and alpha power envelopes for low reward (magenta), high reward (blue), and control (black). Insets show the absence of search array-locked inter-regional cross-frequency coupling using the frequency bands and electrode locations critical for forming the reward and working memory networks (Figs. 1–2).

Statistical analysis

Identifying oscillations

An electrode was considered to exhibit significant phase locking or power at a given frequency (i.e., theta, 3 – 7 Hz, alpha, 8 – 13 Hz, beta, 15 – 30 Hz) if the phase or power peak values during the 100 – 1000 ms poststimulus onset deviated from an uncorrected preevent baseline (−100 to −200 ms) using ANOVAs with p-values adjusted using Greenhouse Geisser correction for nonsphericity (Jennings & Wood, 1976).

We estimated the number of electrodes exhibiting phase locking or power modulations separately for each stimulus epoch (reward cue, target cue, search array) and used a bootstrap method to gauge the Type-I error in this estimate. To estimate the Type-I error at each frequency, the phase or power of EEG activity within each trial was randomly shuffled across sampled time points and reanalyzed 100 times by using the same parameters, producing a distribution of the number of electrodes exhibiting phase locking or power for each task epoch. For a given frequency to obtain significance, the true number of electrodes showing phase locking or power had to exceed the 99th percentile of this distribution (p < 0.01). The following significant oscillations were identified from each task epoch: frontomedial (Fz) reward cue related theta phase locking (3 – 7 Hz); right frontolateral (F4) reward cue related beta power (15 – 30 Hz); frontolateral (F3/4) target cue related theta power (3 – 7 Hz); occipitotemporal (OL/R) target cue related alpha power (8 – 13 Hz); frontolateral (F3/4) search array related theta power (3 – 7 Hz); and posterotemporal (T5/6) search array related alpha power (8 – 13 Hz).

Constructing functional networks

For coupling analysis, the identified EEG responses were divided into discrete windows based on their temporal profiles (i.e., 100 – 1000 ms post reward cue, 100 – 1000 ms post target cue, 100 – 400 ms post search array). We chose these window sizes to balance signal stationarity and accurate assessment of the coupling measures. Moreover, these relatively long time windows reduce the influence of artifactual coupling based on random fluctuations of the signal, such as post-event nonstationarities (Tort, Komorowski, Eichenbaum, & Kopell, 2010). Within each window, the data were normalized from each electrode to have zero mean and unit variance before coupling analysis. To measure electrode associations between the time series recorded at two electrodes, we use two measures of linear coupling: the amplitude-amplitude cross-frequency coupling via time lag cross correlation and phase-amplitude cross-frequency coupling via phase-sorted amplitude height, as described above. These measures of cross-frequency coupling were applied to all epochs (i.e., reward cue, target cue, and search array) and maximal cross-frequency coupling values were computed for all electrode pairs. Significant coupling was determined against a chance distribution derived from the analysis of surrogate time series that share statistical properties with the original data, consistent with established methods (Pereda, Quiroga, & Bhattacharya, 2005; Quian Quiroga, Kreuz, & Grassberger, 2002; Canolty et al., 2006; Tort, Komorowski, Eichenbaum, & Kopell, 2010).

A trial-shuffling procedure allowed us to infer the coupling chance distribution (Tort, Komorowski, Eichenbaum, & Kopell, 2010). Specifically, we created shuffled versions of the time series by associating the phase (or amplitude) series of a randomly chosen trial with the amplitude series of another randomly chosen trial. We then generated a 1,000 surrogate coupling values, from which we could infer the coupling chance distribution. As shown in Figures 1–3, the trial shuffling procedure breaks the appearance of cross-frequency coupling, which is indicated by relatively low coupling values. To minimize a possibility of the Type I error, false discovery rate correction was applied using a threshold set to q = 0.01. Thus, 1% of the network connections were expected to be falsely declared (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995). We cross-validated this method for determining the presence of significant coupling by computing another null distribution, this time by shuffling the order of the trial-wise phase (or amplitude) values with respect to the amplitude values at the same time point and calculating the coupling values 1,000 times.. We assessed whether original coupling values were significantly higher than the 99th percentile of the null distribution. Similar results were obtained using both trial-shuffling procedures for generating null distributions.

Volume conduction of signals coming from a common neuronal source is known to lead to spuriously coupled EEG signals. An effective strategy for minimizing the confounding factor of electrical field spread is to remove information from times series data that is more likely to be explained by a common source (Nunez et al., 1997; Stam, Nolte, & Daffertshofer, 2007). To address this problem we removed all significant coupling values in which the maximum absolute value of the coupling measures occurred at zero time lag between the time series being compared. This method effectively removes spurious coupling values due to volume conduction. However, this method also likely removes some real coupling values. Post hoc analysis showed a high similarity between the average networks generated using coupling measures in which values at zero time lag were included and those networks generated from coupling measures in which the same identified values were removed (ps > 0.34). This strategy therefore allows us to detect the presence of frequency-coupled networks without the effects of volume conduction and with minimal impact on the overall functional networks.

RESULTS

Behavior

Subjects responded significantly faster following high-reward cues (mean ± SEM, 734 ± 7 ms) compared to low-reward cues (750 ± 6 ms; F(1,29) = 5.18, η2 = 0.19, p < 0.03), and performed the task at a similarly high level of accuracy across the high and low-reward trials (mean ± SEM, 96.25% ± 3.3%, p > 0.6). This pattern of behavior is consistent with previous work examining the influences of reward on attentional selection measured behaviorally (e.g., Della Libera & Chelazzi, 2006, 2009; Hickey et al., 2010; Serences, 2008). These behavioral effects provide us with leverage to reveal how the high versus low reward cues at the beginning of the trial influenced the subsequent network dynamics.

Reward-related neural data

Time-frequency analyses in the time window locked to the onset of the reward cue revealed two robust oscillatory responses over frontal cortex both beginning at approximately 100 ms poststimulus. First, the phase locking analysis identified a sustained frontal midline response in the theta band (3 – 7 Hz, Fig. 1C). Second, the total power analysis identified a right frontolateral response in the beta band (15 – 30 Hz, Fig. 1E) that exhibited cyclical bursts of power. Both oscillations were significantly stronger in high- relative to low-reward trials in the 100 – 1000 ms time window following the onset of the reward cue (theta phase locking F(1,29) = 4.57, η2 = 0.13, p < 0.04, beta power F(1,29) = 5.71, η2 = 0.16, p < 0.03). Moreover, theta phase locking (F(1,29) = 5.70, η2 = 0.16, p < 0.03) and beta power (F(1,29) = 6.58, η2 = 0.20, p < 0.02) were significant following a high-reward cue, but not a low-reward cue (ps > 0.3). It is noteworthy that these modulations were not clear in the event-related potentials (ERPs) time locked to the reward cue, indicating a greater sensitivity of spectral analysis in revealing the distributions of phase angle and magnitude information in the time-frequency domain (Fig. 1B–E insets, see also below). These results demonstrate that both frontal theta and beta activities rapidly discriminated the meaning of the reward cue. This is striking given that the reward cues were simple colored circles and the physical stimuli were counterbalanced across subjects.

To further examine the nature of these reward-related theta and beta rhythms, we modeled their potential neural generators. Figure 1B–E illustrates the spatial profile in distributed current density for each frequency-specific response and level of reward, with the center of mass of activity (i.e., warmer colors and crosshair) representing a plausible spatial location of neuronal generation. The theta-band response exhibited a frontomedial distribution over the frontal pole of the cortical surface, with a gravity center located in dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (95% explained variance, Fig. 1B–C). In contrast, beta-band activity revealed a concentration of high-magnitude current densities in ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, constituting most of the orbital gyri (94% explained variance, Fig. 1D–E). These findings suggest that the frontal theta and beta activities triggered by a reward-predictive cue can be measured in areas related to reward expectation (Kahnt, Heinzle, Park, & Haynes, 2010; Vickery, Chun, & Lee, 2011) with the high temporal resolution provided by electrophysiological recordings.

Next, we examined the dynamic temporal structure between theta and beta oscillations for all electrode pairs between 100 – 1000 ms post reward cue. We used cross-frequency coupling indices that directly measure the presence and intensity of phase-amplitude (Lakatos et al., 2005) and amplitude-amplitude (Bruns et al., 2000; Friston, 1997) cross-frequency coupling. Only phase-amplitude coupling was detected. Specifically, using a stringent correction criterion (i.e., 1% false discovery rate or FDR), one electrode pair exhibited significant phase-amplitude cross-frequency coupling relative to values generated from a surrogate control distribution: frontomedial (Fz) and right frontolateral (F3) (Fig. 1F red line). We observed that right frontolateral beta amplitude bursts occurred preferentially during troughs of simultaneous frontomedial theta waves following high-reward cues, but not low-reward cues (Fig. 1G–I). These phase amplitude cross-frequency coupling results were significantly different between high- and low-reward trials (F(1,29) = 7.97, η2 = 0.25, p < 0.01). This effect of reward was unlikely due to differences in the power of oscillatory responses because coupling measures were normalized, and moreover, no significant difference in the signal-to-noise ratios were observed between high and low reward trials (p > 0.21). A more liberal thresholding criterion (i.e. 5% FDR) implicated neighboring electrode pairs, but critically the midline theta phase to right frontolateral beta amplitude network organization remained the same (Fig. 1F black lines). Analysis of theta-phase beta-amplitude coupling within the critical electrode sites (i.e., Fz and F3) revealed no significant results (i.e., mean coupling values did not exceed even the 90th percentile of the null distribution), indicating that the effect was not a strictly local phenomenon. Additionally, outlier analysis showed that average cross-electrode coupling values per subject did not exceed 2.5 SDs, indicating that no particular individuals were driving these effects. In sum, our results show that the potential for high reward on a given trial triggers a specific oscillatory network structure between theta and beta frequencies over prefrontal cortex.

Working memory-related neural data

Our next analysis focused on the visual working memory period directly following the reward prediction period described above. The critical stimulus presented during this epoch was a lateral target object, which instructed subjects to remember the shape of this target for the subsequent visual search task. We found that the time-frequency analyses during the time window locked to the target object cue revealed two prominent lateralized oscillatory responses in the power spectra over frontoparietal areas. Specifically, arising approximately 150 ms post target cue, a sustained and stable posterior alpha power reduction (8 – 13 Hz) contralateral to the remembered location of the target cue was evident during the interval in which this target was held in memory in anticipation of the upcoming visual search array. Similarly, beginning approximately 300 ms post target cue, a sustained and stable frontal theta power enhancement (3 – 7 Hz) contralateral to the remembered location of the target appeared throughout the memory retention interval.

The power of frontolateral theta (low F(1,29) = 4.93, η2 = 0.14, p < 0.04, high F(1,29) = 6.61, η2 = 0.19, p < 0.02, Fig. 2A–B) and the power of lateral posteroparietal alpha oscillations (low F(1,29) = 4.69, η2 = 0.13, p < 0.04, high F(1,29) = 8.25, η2 = 0.21, p < 0.01, Fig. 2C–D) were significantly different from baseline, and significantly different between high versus low-reward trials (theta F(1,29) = 4.23, η2 = 0.11, p < 0.05, alpha F(1,29) = 14.90, η2 = 0.33, p < 0.01; for a discussion regarding the behavioral relevance of these oscillations in comparison to the target cue-locked ERPs shown in Fig. 2A–D insets see below). Moreover, mapping both frequency-specific power responses, as previously done for the reward-related oscillations, revealed neuroanatomical loci across key frontoparietal structures implicated in visual working memory maintenance (Rowe, Toni, Josephs, Frackowiak, & Passingham, 2000; Sakai, Rowe, & Passingham, 2002; Todd & Marois, 2004). Specifically, theta-band current densities exhibited a frontolateral distribution with a focus identified in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (96% explained variance, Fig. 2A–B), whereas the alpha-band response generated a posterolateral distribution of current densities with a gravity center located in lateral intraparietal cortex (96% explained variance, Fig. 2C–D). In sum, after structuring a network approximately 1 second prior for the processing of reward information, the brain enlisted a new set of rhythms with a different temporal-spatial profile and estimated anatomical loci to actively maintain task-relevant information needed to process the upcoming complex scene.

To assess large-scale network connections between theta and alpha frequencies during working memory maintenance, we computed phase-amplitude and amplitude-amplitude cross-frequency coupling for every electrode pair. Only amplitude-amplitude coupling was present. Specifically, using a strict threshold criterion (i.e., 1% FDR), multiple electrode pairs spanning frontolateral (F3/4) to posterolateral areas (PO3/4, O1/2, OL/R) exhibited significant cross correlations relative to surrogate control estimates (Fig. 2E, red lines). That is, we found for both low and high reward that the decrease in posterior alpha activity was linearly synchronized to the increase in frontal theta activity during the memory retention interval (100 – 1000 ms), contralateral to the cue location in the visual field (Fig. 2F). The mean theta-alpha cross-frequency coupling values were significantly greater on high relative to low reward (F(1,29) = 7.21, η2 = 0.19, p < 0.02). This was unlikely due to differences in the power of oscillatory responses given the normalization procedure for coupling and comparable signal-to-noise ratios between high and low reward trials (p > 0.370). The time lag between frontoparietal oscillations was approximately 200 ms for both high and low reward with the frontal theta activity following the posterior alpha activity. A more lenient correction criterion (i.e., 5% FDR) increased the number of significant electrode pairs over frontoparietal regions revealing a similar large-scale network direction and organization (Fig. 2E, black lines). Analysis of subject outliers (> 2.5 SDs) showed that no individual’s data were driving these effects. Moreover, analysis of theta-alpha coupling within frontoparietal electrode sites yielded no significant results (i.e., mean coupling values did not exceed the 86th percentile of the null), indicating that the effect was not local but rather a trial-by-trial interaction between independent neural responses. Thus, oscillatory coupling revealed a long-range neuronal exchange between theta and alpha rhythms during visual working memory maintenance.

Attention-related neural data

The next epoch of each trial was the presentation of a visual search array containing the target object as well as task-irrelevant distractor objects. As subjects maintained central fixation and performed visual search, we found that two robust lateralized oscillations were evident in the power spectra over frontotemporal areas. Beginning approximately 100 ms after the onset of the search array, a sustained yet relatively short-lived increase in theta power (3 – 7 Hz) appeared over frontal areas contralateral to the location of the search target. Also, arising approximately 150 ms following the search array over posterotemporal areas, a sustained decrease in alpha power (8 – 13 Hz) appeared contralateral to the location of the search target.

The power of frontolateral theta (low F(1,29) = 5.33, η2 = 0.16, p < 0.03, high F(1,29) = 8.03, η2 = 0.22, p < 0.01, Fig. 3A–B) and the power of lateral posterotemporal alpha oscillations (low F(1,29) = 4.63, η2 = 0.14, p < 0.05, high F(1,29) = 10.02, η2 = 0.26, p < 0.01, Fig. 3C–D) were significantly different from baseline, and significantly different between high and low reward (theta F(1,29) = 4.23, η2 = 0.13, p < 0.05, alpha F(1,29) = 27.76, η2 = 0.46, p < 0.01). Insets show the corresponding search array-locked ERPs (see below for a discussion of the behavioral relevance between ERPs and oscillations). Source modeling estimated the neuroanatomical regions giving rise to both attention-related rhythms, 100 – 400 ms post-search array. Note that this measurement interval was approximately 350 ms prior to the manual response of the subjects, indicating that these oscillations are related to the visual processing of the array and are unlikely to reflect processing at the response stage. The theta-band response exhibited a frontolateral current density distribution with a potential generator identified in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (93% explained variance, Fig. 3A–B). The alpha-band response exhibited a lateral posterotemporal distribution with a neural source estimated in the inferior temporal lobe (97% explained variance, Fig. 3C–D). Thus, despite partial overlap with one oscillation from the previous working memory network, using attention to select an object from a complex visual scene engaged a unique set of rhythms with a distinct time course, spatial profile and estimated neural sources.

To assess the temporal relationship between the frontal and posterotemporal rhythms elicited by searching for the target in the scenes, we computed phase-amplitude and amplitude-amplitude cross-frequency coupling for every electrode pair. We found only significant amplitude-amplitude coupling. Specifically, significant cross correlation estimates (using 1% FDR) were observed across the following electrode pairs: frontolateral (F3/4) and lateral posterotemporal (T3/4, T5/6) (Fig. 3E, red lines). That is, we observed that the decrease in alpha activity along the ventral visual pathway (i.e., electrode T3/4, T5/6) was synchronized to an increase in theta activity over prefrontal cortex (i.e., electrode F3/4) during the allocation of visual attention (i.e., 100 – 400 ms), contralateral to search target location in the visual field (Fig. 3F). A more liberal threshold (i.e., 5% FDR) revealed additional significant electrode pairs with the same general direction and pattern of amplitude coupling (Fig. 3E, black lines). No significant theta-alpha coupling was observed within any of these electrodes, suggesting that the effect was not local in nature. Moreover, no outliers were found in the distribution of subjects’ average cross-correlation values. Due to the extended time course of the posterotemporal alpha power reduction we also assessed functional connectivity beyond the window of visual attention deployment (i.e., 400 – 750 ms), but found no significant frontotemporal coupling, suggesting a role for posterior alpha in further downstream information processing.

Finally, we found that the reward cue that was presented at the beginning of the trial modulated the strength of the theta-alpha attentional network almost three seconds later. We observed significant differences between high and low reward (F(1,29) = 8.20, η2 = 0.18, p < 0.01), with high reward resulting in greater mean synchronization strength between areas during visual search, despite similar signal-to-noise ratios for these trial types (p > 0.284) and the normalization of our synchronization measures. The time lag between these widely distributed oscillations was approximately 50 ms for both high and low reward, with the frontal theta activity leading the posterotemporal alpha activity. In sum, the formation of a network controlling visual attention was revealed via oscillatory synchrony between theta and alpha rhythms spanning frontotemporal regions and modulated by monetary incentive.

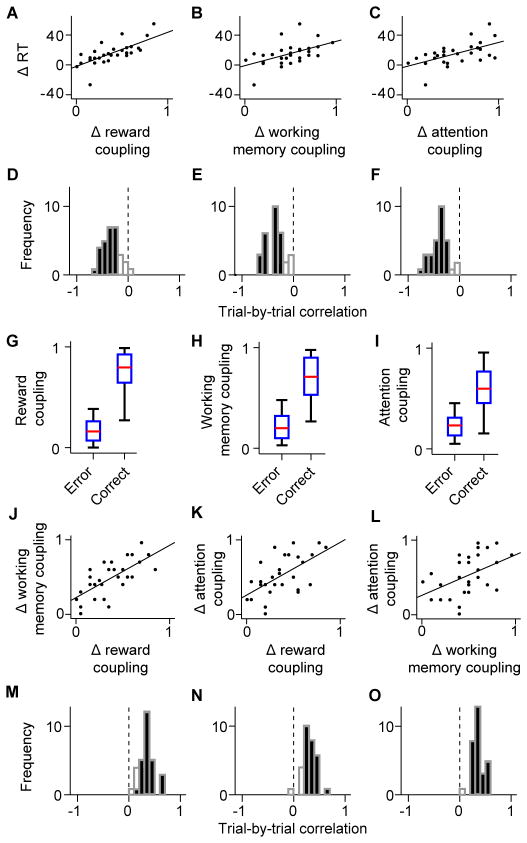

Network relationships and behavior

If inter-regional interactions regulated by oscillatory synchrony serve a functional role, then such high-level network activity should influence the ultimate behavior of the subject. Given the robust effects of our reward manipulation on subjects’ speed of responding to the target object in the complex scene, we first focused on the relationship between reward-triggered behavioral benefits (i.e., RT speeding) and the preceding inter-regional interactions on high compared to low reward trials. We found that those subjects with the strongest cross-frequency coupling exhibited the largest reward-triggered RT improvements during reward encoding (r = 0.712, p < 0.01, ~3 seconds before response, Fig. 4A), visual working memory maintenance (r = 0.511, p < 0.01, ~2 seconds before response, Fig. 4B) and the deployment of visual attention (r = 0.572, p < 0.01, ~0.7 seconds before response, Fig. 4C). Critically, strong trial-by-trial relationships between RT and network coupling strength were observed (Fig. 4D–F, Fisher’s z test, p < 0.05) for a majority of individual subjects (mean r ± SE, reward −0.299 ± 0.031, 24 of 30 subjects, memory −0.363 ± 0.033, 25 of 30 subjects, attention −0.379 ± 0.030, 27 of 30 subjects). However, relationships between single-trial RT and the networks inactive during each epoch was not significant for any subjects, including after reward cue onset (memory 0.023 ± 0.117; attention −0.013 ± 0.118), during the memory retention interval (reward 0.039 ± 0.133; attention 0.042 ± 0.140), and after visual search array onset (reward 0.065 ± 0.106; memory −0.025 ± 0.088) indicating that each network is unique to each epoch of interest.

Figure 4.

Inter-regional synchrony and performance. Individual subject correlations between RT and interregional cross-frequency coupling following reward cue (A), target cue (B), and search array (C) in high minus low-reward trials. Trial-by-trial correlations between RT and inter-regional cross-frequency coupling following reward cue (D), target cue (E), and search array (F). Significant correlation coefficients are shown in dark bars. Dashed vertical lines represent a correlation of zero. Inter-regional cross-frequency coupling following reward cue (G), target cue (H), and search array (I) for all error and correct trials. The central red bar indicates the median, and the edges of boxes indicate 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. Individual subject inter-regional cross-frequency coupling correlations between reward and working memory networks (J), reward and attention networks (K), and working memory and attention networks (L) on high- minus low-reward trials. Trial-by-trial correlations between the inter-regional cross-frequency coupling of the reward and working memory networks (M), reward and attention networks (N), and working memory and attention networks (O). Conventions are as in D–F.

To determine the reliability of these single-trial relationships, we calculated the significance of the observed correlations against a surrogate distribution of r values based on 10,000 shuffles of trial and coupling values. We found that the observed r values could not have been derived from the surrogate distribution (zs > 3.1, ps < 0.001). Interestingly, the few subjects that did not exhibit significant single-trial effects appeared to simply be poor couplers in general, as they were the same individuals with weak single-trial correlations across the three epochs of the trials. These results reveal that network synchronization strength can predict the reward-triggered behavioral advantage and serve as a more general trial-by-trial predictor of the speed of the behavioral responses.

To further investigate the hypothesis that network-level neuronal interactions are instrumental to task performance, we examined inter-regional cross-frequency coupling on error versus correct trials of all subjects (Fig. 4G–I). Correct trials were associated with increased coupling across the reward, working memory, and attention networks. We found that the average coupling on correct trials (reward 0.80, working memory 0.70, attention 0.60) was approximately triple that observed on error trials (reward 0.18, working memory 0.20, attention 0.22). Across all subjects and trials, correct and error trials were distinguished by significantly different coupling values in reward, working memory and attention networks (η2s > 0.22, ps < 0.01), and coupling values above a certain threshold (reward 0.40, working memory 0.48, attention 0.45) were associated exclusively with correct performance. In all, our results demonstrate that stronger inter-regional cross-frequency coupling leads to more successful task performance, and conversely, when the coupling strength of these networks breaks down, this is reflected in the subsequent behavioral output.

Next, we computed the relationships between networks. Given that reward-triggered performance gains are predicted by the strength of various networks that form and dissolve throughout the course of the task, as described above, then how are the reward-triggered gains in network activity strength related? We found significant subject-wise, reward-triggered relationships between reward and visual working memory networks (r = 0.696, p < 0.01, Fig. 4J), reward and visual attention networks (r = 0.615, p < 0.01, Fig. 4K), and between visual working memory and attention networks (r = 0.475, p < 0.01, Fig. 4L). Moreover, strong trial-by-trial correlations between networks were observed (Fig. 4M–O; Fisher’s z test, p < 0.05) for a majority of individual subjects (mean r ± SE, reward vs. working memory 0.326 ± 0.025, 26 of 30 subjects, reward vs. attention 0.262 ± 0.025, 25 of 30 subjects, working memory vs. attention 0.365 ± 0.025; 29 of 30 subjects), again with overlapping, non-significant results coming from the same individuals who exhibited poor coupling in general. Using the same method mentioned above for evaluating the reliability of these single-trial correlations, we found that the probability that these observed r values were derived from a surrogate distribution was < 0.001. The above results are based on networks measured during each epoch, such as the theta phase beta amplitude frequency coupled network measured directly after reward cue onset. However, we also examined the relationships between the currently active network and networks active during the other epochs of each trial. No subject showed significant trial-by-trial correlations between current-epoch network and other-epoch networks during reward encoding (reward vs. memory −0.060 ± 0.107, reward vs. attention 0.007 ± 0.113), visual working memory maintenance (memory vs. reward −0.020 ± 0.125, memory vs. attention −0.008 ± 0.125), or attentional selection phases of the trials (attention vs. reward 0.015 ± 0.105, attention vs. memory −0.046 ± 0.095). These results demonstrate the interplay between dynamic, selectively activated networks, and show that a network formed even before the presentation of task-relevant stimuli can predict the strength of subsequent networks involved in processing the imperative stimuli.

Finally, we asked whether our measures of inter-regional cross-frequency coupling were better at predicting the upcoming behavior than more traditional electrophysiological measures. First, we examined the within-electrode phase and power measures of frequency-band oscillations of theta, alpha, and beta that we had identified specific to reward, working memory, and attention. We found that significant single-trial relationships between the basic frequency-band signals (power and phase) and accuracy were present in a dramatically fewer number of subjects (< 7 out of 30 per test, Fisher z test, p < 0.05, mean r ± SE, −0.183 ± 0.019), and that the variance in the RT data of these same subjects were better accounted for using our measure of network connectivity strength (mean r ± SE, −0.376 ± 0.026). Across all subjects and trials, correct and error trials were only significantly distinguished by frontolateral theta (F(1,29) = 4.56, η2 = 0.15, p < 0.04) and posterolateral alpha power responses (F(1,29) = 6.23, η2 = 0.18, p < 0.02) during the visual working memory maintenance stage of the task. However, these signals were significantly less predictive than our measure of working memory network coupling strength (F(1,29) = 17.80, η2 = 0.35, p < 0.01).

Next, we performed the same RT and accuracy analyses on the amplitude of the visual attention and working memory ERP components elicited in the task. The N2pc is a negative-going ERP waveform observed over posterior cortex, contralateral to where in the visual field attention is focused (Luck, Fan, & Hillyard, 1993; Luck & Hillyard, 1990). The contralateral delay activity (or CDA) is an ERP component characterized as a sustained posterior negativity, contralateral to the location where an object had appeared, as it is actively maintained in visual working memory (Vogel & Machizawa, 2004; Vogel, McCollough, & Machizawa, 2005; Woodman & Vogel, 2008). We found significant (Fisher z test, p < 0.05) single-trial RT correlations in only 4 subjects using the N2pc (mean r ± SE: −0.304 ± 0.021) and in only 7 subjects using the CDA to predict response speed (−0.334 ± 0.037). Moreover, inter-regional coupling explained more average variance in these subjects’ RT data (4 subjects mean r ± SE: −0.427 ± 0.029; 7 subjects mean r ± SE: −0.466 ± 0.034). Additionally, neither the N2pc nor the CDA could distinguish between correct and error trials across all subjects and trials (ps > 0.19). Thus, our analyses of the raw frequency power and ERPs demonstrate that network synchronization strength is a superior predictor of the speed and success of subjects’ behavioral responses.

DISCUSSION

We found that when a subject was given the opportunity to earn a large reward, theta and beta oscillations over prefrontal regions formed a distributed network defined by the coupling of these distinct frequencies. Next, we found that as subjects maintained a representation of the target object in visual working memory, theta and alpha oscillations across frontoparietal areas formed a network distinct from that related to processing the reward cue. This network had its own temporal code allowing for inter-regional communication between the areas maintaining the memory representation of the task-relevant information in the brain. Then, as the subjects searched for the target object in the complex visual scenes, theta and alpha oscillations across frontotemporal areas formed a third spatially distinct network related to the deployment of visual attention and perceptual analysis of the search array.1 Each of the observed networks was absent during the formation of the others (see insets in Figs. 1I, 2F, and 3F), and only predictive of behavior and other network activity when selectively activated during the relevant stage of the task. The behavior of these networks is consistent with the transient coding hypothesis, which proposes that functional interactions between neuronal populations are mediated by temporal-spatial dynamics that endure over relatively brief time periods (i.e., ~100 – 1000 ms) (Friston, 1997; Vaadia et al., 1995).

Our study breaks new ground in demonstrating reward-dependent inter-regional synchrony in the cortex and the influence of this reward network on the synchronous oscillations underlying visual working memory maintenance (see also Palva, Monto, Kulashekhar, & Palva, 2010; Sarnthein, Petsche, Rappelsberger, Shaw, & von Stein, 1998) and attentional selection (Gross et al., 2004; Siegel, Donner TH, Oostenveld, Fries, & Engel, 2008). Specifically, our results show that medial prefrontal theta and nested orbitofrontal beta form a relational code supporting the processing of reward information in the human brain. The phase locking of theta appears to temporally align activity in the medial prefrontal area with the beta oscillations in targeted orbitofrontal areas. This type of coupling can enhance the impact of the observed activity across regions. Animal studies report that the neural activity in the amygdala and medial prefrontal cortex are synchronized by theta oscillations during reward prediction or the delivery of reward (e.g., Siapas, Lubenov, & Wilson, 2005). Also consistent with our results, human frontal beta activity has been associated with motivation and relative evaluation of reward values (Cohen, Elger, & Ranganath, 2007; Marco-Pallares et al., 2008). A similar sustained and phasic temporal pattern of reward triggered frontal beta activity has been observed within a single electrode in one other human study (Kawasaki & Yamaguchi, 2012), and is characteristic of midbrain dopaminergic responses and straital activity within the brain circuit for reward (Fiorillo, Tobler, & Schultz, 2003; McClure, Berns, & Montague, 2003). The present findings suggest that it is possible to measure the activity of this reward-related network noninvasively in humans performing a variety of tasks.

Most surprisingly, the signal-to-noise ratios of these coupling measures were high. As evidence of this, our measures of network synchronization strength showed high single-trial predictive power. Specifically, the activity of the reward and working memory networks, formed even before the presentation of task-relevant scene stimuli, could predict the strength of the subsequent network active while the imperative stimuli were processed, as well as behavioral success and response speed. Moreover, our network synchronization measures significantly outperformed more conventional electrophysiological measures of brain activity (i.e., individual oscillations and event-related potentials) in the ability to predict the ultimate behavior on each trial. By revealing the behavioral significance of precise cross-frequency interactions organizing different large-scale networks, our results join of growing body of work (Siegel, Donner, & Engel, 2012), suggesting that large-scale network activity is a critical intermediate level of neural organization linking circuit-level computation to higher-order experience and behavior.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01- EY019882, P30-EY08126, and P30-HD015052) and National Science Foundation (BCS-0957072).

Footnotes

We have replicated these primary findings showing separate frequency-coupled networks related to reward encoding, visual working memory maintenance, and attentional selection in an independent sample of subjects (N = 14) using the same general task and analysis procedures. We again found that the network strengths from each epoch significantly correlated with single-trial RT (mean r ± SE, reward −0.240 ± 0.027, 11 of 14 subjects, memory −0.229 ± 0.026, 11 of 14 subjects, attention −0.294 ± 0.032, 12 of 14 subjects).

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

None declared

References

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bruns A, Eckhorn R, Jokeit H, Ebner A. Amplitude envelope correlation detects coupling among incoherent brain signals. Neuroreport. 2000;11(7):1509–1514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canolty R, Knight R. The functional role of cross-frequency coupling. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2010;14(11):506–515. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canolty RT, Edwards E, Dalal SS, Soltani M, Nagarajan SS, Kirsch HE, et al. High gamma power is phase-locked to theta oscillations in human neocortex. Science. 2006;313:1626–1628. doi: 10.1126/science.1128115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M, Elger C, Ranganath C. Reward expectation modulates feedback-related negativity and EEG spectra. Neuroimage. 2007;35:968–978. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.11.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale AM, Sereno MI. Improved localization of cortical activity by combining EEG and MEG with MRI cortical surface reconstruction: A linear approach. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1993;5:162–176. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1993.5.2.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della Libera C, Chelazzi L. Visual selective attention and the effects of monetary reward. Psychological Science. 2006;17:222–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della Libera C, Chelazzi L. Learning to attend and to ignore is a matter of gains and losses. Psychological Science. 2009;20:778–784. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delorme A, Makeig S. EEGLAB: An open source toolbox for analysis of singel-trial EEG dynamics including independent component analysis. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2004;134(1):9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel AK, Fries P, Singer W. Dynamic predictions: oscillations and synchrony in top-down processing. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2001;2:704–716. doi: 10.1038/35094565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorillo C, Tobler P, Schultz W. Discrete coding of reward probability and uncertainty by dopamine neurons. Science. 2003;299:1898–1902. doi: 10.1126/science.1077349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston K. Another neural code? Neuroimage. 1997;5:213–220. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1997.0260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs M, Drenckhahn R, Wischmann HA, Wagner M. An improved boundary element method for realistic volume-conductor modeling. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1998;45(8):980–997. doi: 10.1109/10.704867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross J, Schmitz F, Schnitzler I, Kessler K, Shapiro K, Hommel B, et al. Modulation of long-range neural synchrony reflects temporal limitations of visual attention in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2004;101:13050–13055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404944101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickey C, Chelazzi L, Theeuwes J. Reward changes salience in human vision via the anterior cingulate. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30:11096–11103. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1026-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings JR, Wood CC. The e-adjustment procedure for repeated-measures analyses of variance. Psychophysiology. 1976;13:277–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1976.tb00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahnt T, Heinzle J, Park S, Haynes JD. The neural code of reward anticipation in human orbitofrontal cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2010;107(13):6010–6015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912838107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki M, Yamaguchi Y. Frontal theta and beta synchronizations for monetary reward increase visual working memory capacity. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2012:1–8. doi: 10.1093/scan/nss027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakatos P, Shah A, Knuth K, Ulbert I, Karmos G, Schroeder C. An oscillatory heirarchy controlling neuronal excitability and stimulus processing in the auditory cortex. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2005;94(3):1904–1911. doi: 10.1152/jn.00263.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luck SJ. An introduction to the event-related potential technique. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Luck SJ, Fan S, Hillyard SA. Attention-related modulation of sensory-evoked brain activity in a visual search task. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1993;5:188–195. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1993.5.2.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luck SJ, Hillyard SA. Electrophysiological evidence for parallel and serial processing during visual search. Perception & Psychophysics. 1990;48:603–617. doi: 10.3758/bf03211606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marco-Pallares J, Cucurell D, Cunillera T, Garcia R, Andres-Pueyo A, Munte T, et al. Human oscillatory activity associated to reward processing in a gambling task. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46:241–248. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazaheri A, Jensen O. Asymmetric amplitude modulations of brain oscillations generate slow evoked responses. Joural of Neuroscience. 2008;28:7881–7787. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1631-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure S, Berns G, Montague P. Temporal prediction errors in a passive learning task activate human striatum. Neuron. 2003;38:339–346. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00154-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez PL, Srinivasan R, Westdorp AF, Wijesinghe RS, Tucker DM, Silberstein RB, et al. EEG coherency. I. Statistics, reference electrode, volume conduction, Laplacians, cortical imaging, and interpretation at multiple scales. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 1997;103:499–515. doi: 10.1016/s0013-4694(97)00066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oostenveld R, Fries P, Maris E, Schoffelen JM. FieldTrip: Open source software for advanced analysis of MEG, EEG, and invasive electrophysiological data. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience. 2011;2011:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2011/156869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palva J, Monto S, Kulashekhar S, Palva S. Neuronal synchrony reveals working memory networks and predicts individual memory capacity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2010;107:7580–7585. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913113107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual-Marqui RD. Standardized low-resolution brain electromagnetic tomography (sLORETA): technical details. Methods & Findings in Experimental & Clinical Pharmacology. 2002;24:5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penny W, Duzel E, Miller K, Ojemann J. Testing for nested oscillation. Joural of Neuroscience Methods. 2008;174:50–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereda E, Quiroga RQ, Bhattacharya J. Nonlinear multivariate analysis of neurophysiological signals. Progress in Neurobiology. 2005;77(1–2):1–37. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quian Quiroga R. Bivariable and multivariable analysis of EEG signals. In: Tong S, Thakor N, editors. Quantitative EEG Analysis: Methods and Applications. Artech House; 2009. pp. 109–120. [Google Scholar]

- Quian Quiroga R, Kreuz TK, Grassberger P. Performance of different synchronization measures in real data: A case study on electroencephalographic signals. Physical Review E. 2002;65(4):1–14. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.65.041903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe J, Toni I, Josephs O, Frackowiak R, Passingham R. The prefrontal cortex: Response selection or maintenance within working memory. Science. 2000;288:1656–1660. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5471.1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai K, Rowe J, Passingham R. Active maintenance in prefrontal area 46 creates distractor-resistant memory. Nature Neuroscience. 2002;5(5):479–484. doi: 10.1038/nn846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salinas E, Sejnowski T. Correlated neuronal activity and the flow of neural information. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2001;2:539–550. doi: 10.1038/35086012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarnthein J, Petsche H, Rappelsberger P, Shaw G, von Stein A. Synchronization between prefrontal and posterior association cortex during human working memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1998;95:7092–7096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serences J. Value-based modulations in human visual cortex. Neuron. 2008;60:1169–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siapas A, Lubenov E, Wilson M. Prefrontal phase locking to hippocampal theta oscillations. Neuron. 2005;46:141–151. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel M, Donner TH, Oostenveld R, Fries P, Engel A. Neuronal synchronization along the dorsal visual pathway reflects the focus of spatial attention. Neuron. 2008;60:709–719. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel M, Donner TH, Engel AK. Spectral fingerprints of large-scale neuronal interactions. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2012;13:121–134. doi: 10.1038/nrn3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stam CJ, Nolte G, Daffertshofer A. Phase lag index: assessment of functional connectivity from multi channel EEG and MEG with diminished bias from common sources. Human Brain Mapping. 2007;28:1178–1193. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd JJ, Marois R. The capacity limit of visual short-term memory in human posterior parietal cortex. Nature. 2004;428:751–753. doi: 10.1038/nature02466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tort A, Komorowski R, Eichenbaum H, Kopell N. Measuring phase-amplitude coupling between neuronal oscillations of different frequencies. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2010;104(2):1195–1210. doi: 10.1152/jn.00106.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlhaas P, Singer W. Abnormal neural oscillations and synchrony in schizophrenia. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2010;11(2):100–113. doi: 10.1038/nrn2774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaadia E, Haalman I, Abeles M, Bergman H, Prut Y, Slovin H, et al. Dynamics of neuronal interactions in monkey cortex in relation to behaviourial events. Nature. 1995;373:515–518. doi: 10.1038/373515a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk H, Van der Werf J, Mazaheri A, Medendorp P, Jensen O. Modulations in oscillatory activity with amplitude asymmetry can produce cognitively relevant event-related responses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2010;107(2):900–905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908821107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varela F, Lachaux JP, Rodriguez E, Martinerie J. The brainweb: phase synchronization and large-scale integration. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2001;2:229–239. doi: 10.1038/35067550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickery T, Chun M, Lee D. Ubiquity and specificity of reinforcement signals throughout the human brain. Neuron. 2011;72:166–177. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel EK, Machizawa MG. Neural activity predicts individual differences in visual working memory capacity. Nature. 2004;428:748–751. doi: 10.1038/nature02447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel EK, McCollough AW, Machizawa MG. Neural measures reveal individual differences in controlling access to working memory. Nature. 2005;438:500–503. doi: 10.1038/nature04171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner M, Fuchs M, Kastner J. SWARM: sLORETA-weighted accurate minimum norm inverse solutions. International Congress Series. 2007;1300:185–188. [Google Scholar]

- Woodman GF, Luck SJ. Serial deployment of attention during visual search. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2003;29:121–138. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.29.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodman GF, Vogel EK. Top-down control of visual working memory consolidation. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2008;15:223–229. doi: 10.3758/pbr.15.1.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]