Abstract

Unconjugated monoclonal antibodies that target hematopoietic differentiation antigens have been developed to treat hematologic malignancies. Although some of these have activity against chronic lymphocytic leukemia and hairy cell leukemia, in general, monoclonal antibodies have limited efficacy as single agents in the treatment of leukemia. To increase their potency, the binding domains of monoclonal antibodies can be attached to protein toxins. Such compounds, termed immunotoxins, are delivered to the interior of leukemia cells based on antibody specificity for cell surface target antigens. Recombinant immunotoxins have been shown to be highly cytotoxic to leukemic blasts in vitro, in xenograft model systems, and in early-phase clinical trials in humans. These agents will likely play an increasing role in the treatment of leukemia.

Introduction

A growing number of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) have been approved for the treatment of hematologic malignancies.1 Newer constructs have been designed to improve activity, for example, through the engineering of Fc domains with improved antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity function. Although some of these agents have activity against chronic lymphocytic leukemia2 and hairy cell leukemia (HCL),3 in general, mAbs have limited efficacy as single agents in the treatment of other leukemia subtypes. However, the binding domains of mAbs, including variable fragments (Fvs) and antigen binding fragments (Fabs), can be used to deliver highly cytotoxic substances to cells that express cognate antigens on their surface. mAb-based conjugates have been developed by using plant and bacterial toxins, drugs, and radioisotopes. This review focuses on the development of high-molecular-weight protein toxin conjugates to treat leukemia. (Antibody drug conjugates and radioimmunotherapy are reviewed elsewhere.4-6) Toxin conjugates are attractive as anticancer agents because of the potency of their enzymatic domains. However, the clinical development of immunotoxins has been hindered by a variety of problems, including poor antigen specificity, low cytotoxicity, nonspecific toxicities, immunogenicity, and production difficulties. Many of these have been overcome through protein engineering, and this review covers advances over the past 5 years.

Immunotoxin structure

Immunotoxins have 2 primary components: targeting and killing moieties. Antibody fragments or whole antibodies may be used for targeting, and larger constructs have longer pharmacokinetic half-lives in comparison with Fv-based conjugates. Linkage options include gene fusions, peptide bonds, disulfide bonds, and thioether bonds. Importantly, toxin attachment to the antibody must not interfere with antigen binding. Furthermore, the hybrid protein must remain intact while in the systemic circulation, but it must disassemble inside the target cell in order to release the toxin. Uncoupling the toxin from the antibody is accomplished by protease degradation, disulfide bond reduction, or hydrolysis of an acid-labile bond.

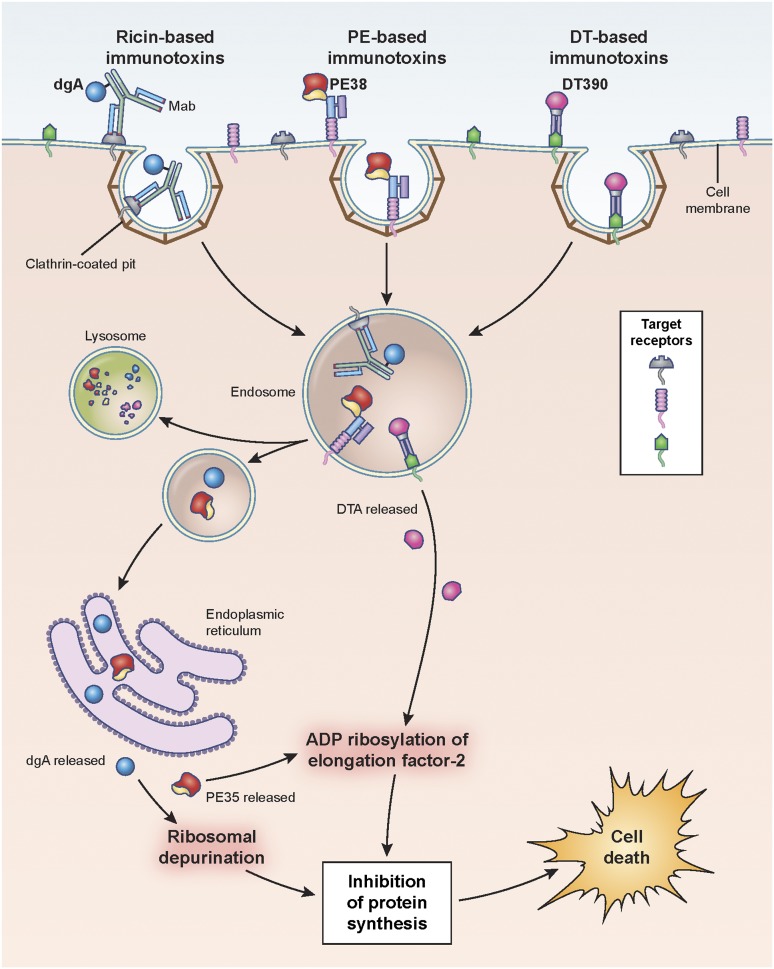

Hematopoietic differentiation antigens and receptors that are expressed on the surface of leukemia cells are excellent targets, provided they are not expressed on normal vital tissues (Table 1). Additionally, antigen targets must be internalized after mAb binding in order for the immunotoxin to be transported intracellularly so that the toxin domain can mediate its cytotoxic action (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Immunotoxins for leukemia

| Antigen | Target leukemia | Agent | Conjugate | ClinicalTrials.gov identifier (12/2013) | References (2009-2013) | Toxicities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD3 | T-lineage ALL | A-dmDT390-bisFv(UCHT1) | Diphtheria toxin A | NCT00611208 | Fever, chills, nausea, hepatic, hypoalbuminemia, lymphopenia, viral reactivation | |

| CD19, CD22 | B-lineage ALL, CLL | Combotox (mixture of HD37-dgA and RFB4-dgA) | Ricin-dgA | NCT00450944 NCT01408160 | 39, 40 | Pancreatitis, anaphylaxis, graft-versus-host disease exacerbation, hypoalbuminemia, CLS |

| DT2219ARL(bispecific) | Diphtheria toxin | NCT00889408 | Unavailable | |||

| CD22 | B-lineage ALL, CLL, HCL | Moxetumomab pasudotox, (HA22, CAT- 8015) | Pseudomonas exotoxin A | NCT01891981 NCT01829711 NCT00659425 | 35 | Hypoalbuminemia, peripheral edema, hepatic, CLS, HUS fever |

| BL22 (CAT-3888) | Pseudomonas exotoxin A | 30, 32 | Hypoalbuminemia, hepatic, HUS | |||

| CD25 | ALL, ATL | LMB-2 | Pseudomonas exotoxin A | NCT00924170 NCT00321555 | 22 | Hepatic, hypoalbuminemia, fever, cardiomyopathy |

| RFT5-dgA (IMTOX-25) | Ricin-dgA | NCT01378871 | CLS, allergy, myalgia, nausea | |||

| CD25, CD122, CD132 | ALL, ATL | Denileukin difititox (Ontak)* | IL-2 conjugated to diphtheria toxin | 19, 20 | Rigors, fever, nausea, CLS | |

| CD33 | AML, CML | HUM-195/rGEL | Gelonin | 44 | Allergy, fever, hypoxia, hypotension |

Clinical trials published between 2009 and 2013 and active clinical trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov as of December 2013 are included. Toxicity summary includes common or severe adverse events associated with the specific agent based on published reports.

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ATL, adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CML. chronic myeloid leukemia; dgA: deglycosylated ricin A chain.

Approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in adults.

Figure 1.

Pathways of binding, internalization, and processing by immunotoxins leading to the killing of target cells. Shown are ricin-, Pseudomonas- and diphtheria-based immunotoxins. Immunotoxins bind the target antigen, are internalized via clathrin-coated pits, and are processed within endosomal compartments. Ricin and Pseudomonas toxin derivatives must traffic through the endoplasmic reticulum to the cytosol where they enzymatically inactivate protein synthesis. Pseudomonas exotoxin A ADP-ribosylates EF2, while ricin depurinates ribosomal RNA. Diphtheria-based toxins are internalized to endosomes where the A chain of the toxin translocates directly to the cytosol and ADP-ribosylates EF2. Cell death follows inhibition of protein synthesis. dgA: deglycosylated ricin A chain; EF2: elongation factor 2.

Protein toxins are highly potent enzymes, and only a small number of molecules need to be delivered to the site of action, the cell cytosol.7 Once delivered, the turnover rate of the enzyme will allow many substrate molecules to be modified for each toxin molecule. Protein toxins can be attached directly to antibodies via peptide bonds, and they can be modified easily through gene engineering, which is particularly useful when designing improved versions.7

However, because toxins are foreign proteins, they can induce antibody formation.4 Although this is a potential problem, protein engineering can be used to modify immunogenic epitopes to reduce immunogenicity. Examples of clinically relevant immunotoxins that have undergone or are currently undergoing study in humans are provided in Table 1.

The majority of the protein toxins in clinical development are different types of enzymatic inhibitors of protein synthesis. Diphtheria toxin (DT) and Pseudomonas exotoxin A (PE) catalyze the adenosine 5′-diphosphate (ADP)-ribosylation of elongation factor 2 at the diphthamide-modified histidine 715, which halts the elongation of growing peptide chains. Plant toxins inactivate ribosomes via glycosidase activity. Specifically, ricin hydrolyzes the N-glycosidic bond of the adenine residue at position 4324. Ricin-like toxins exhibit similar activities.

Using gene-engineering techniques, truncated DT and PE genes are fused with complementary DNAs encoding antibody Fvs or Fabs to make recombinant immunotoxins.8 To accomplish this, the toxin’s native binding domain is deleted and replaced with the antibody gene sequence. To preserve essential toxin functions, the Fv or Fab is inserted in the same location as the toxin-binding domain (eg, at the N-terminus of PE and C-terminus of DT) (Figure 2). The preferred construct of DT includes the first 388-389 amino acids followed by a cell-binding moiety. For PE-based immunotoxins, the Fv is followed by a toxin fragment that includes a processing domain followed by its ADP-ribosylating domain. For PE, but not DT, a C-terminal sequence that binds the KDEL receptor is needed for cytotoxic action. Ricin is not easily engineered into functional gene fusions. Therefore ricin-based immunotoxins rely on chemical conjugation of deglycosylated ricin A chain (dgA) to intact antibodies or Fabs. A variation on this theme attaches whole ricin, with its sugar-binding sites blocked via chemical modification, to intact antibodies, thereby producing “blocked ricin” immunotoxins.9

Figure 2.

Molecular structures of Pseudomonas exotoxin (1IQK.pdb), diphtheria toxin (1TOX.pdb), and ricin toxin (2AAI.pdb). From left to right (blue to red), sequences are shown from the N-terminus to the C-terminus of each protein. To construct immunotoxins, the binding domain of each toxin is removed and replaced with an antibody or antibody fragment. The enzyme domains of PE, DT, and ricin are shown as either ADP-ribosylation or RNA N-glycosidase, as indicated. Middle domains for PE and DT are shown in yellow-green and include a furin processing site (white arrows): the furin site of DT is not ordered in the crystal structure so its approximate location is indicated. For DT, helical structures in the middle domain facilitate toxin translocation. The translocation activity of PE has not been definitively determined. Ricin apparently contains translocation sequences within the enzyme (blue) domain. The enzyme domain of ricin toxin is equivalent to deglycosylated ricin A chain. Intact ricin toxin contains tandem C-terminal binding modules (red).

Mechanism of action

For immunotoxins to function as cytotoxic agents, the molecule must first be internalized. Importantly, the kinetics of internalization affect cytotoxicity, and immunotoxins are generally more active when targeted to antigens that are efficiently internalized.10 Inside the cell, the toxin must then be released and transported to the cytosol. Endosomes, lysosomes, and the endoplasmic reticulum play critical roles in the fate of these molecules. However, unlike certain antibody-drug conjugates,11,12 protein toxins must stay intact and avoid lysosomal degradation.13 Although the percentage of toxin trafficked to lysosomes has not been quantified, early studies of the delivery efficiency of PE indicated that ∼4% of cell-associated toxin molecules reached the cytosol.14 Deletion of most of domain II of PE, which contains several lysosomal cleavage sites, produces a protease-resistant immunotoxin with increased cytotoxic activity suggesting that this domain may contribute to inefficiencies of PE-based immunotoxins.13 DT, specifically the diphtheria toxin A chain, translocates to the cytosol from acidic endosomes while PE requires a KDEL-like sequence to traffic to the endoplasmic reticulum from which it can then enter the cytosol. The ricin pathway to the cytosol more closely resembles the PE pathway than the DT one (Figure 1).15

Toxins are released from antibodies in several ways: by proteases, by disulfide bond reduction, or by exposure to an acidic environment. Protein toxins joined to antibodies via peptide bonds require proteolytic cleavage. Toxins attached chemically by disulfide bonds require reduction. Some acid labile linkers favor toxin release in endosomes or lysosomes. Release of DT- and PE-related proteins depend on a furin-like cleavage followed by the reduction of a key disulfide bond.16,17

In living cells, delivery to the appropriate intracellular location for toxin release appears to be a key factor in determining the effectiveness of the immunotoxin. For example, immunotoxins directed to CD22 are more potent than those to CD19, despite the fact that the number of cell-associated surface molecules is greater for CD19, related at least in part to more rapid CD22-mediated internalization.10

Immunotoxins in clinical trials

Targeting the interleukin-2 receptor

The interleukin-2 receptor (IL-2R) complex, which consists of 3 subunits—α (CD25), β (CD122), and γ (CD132)—is expressed on T lymphocytes and natural killer cells.18 Denileukin diftitox (DD) is a protein composed of IL-2 fused to the first 388 amino acids of DT. Although it has IL-2 instead of an Fv, it targets and functions like an immunotoxin. DD is approved for the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in adults, and activity has been reported in other hematologic malignancies, including IL-2R–expressing leukemias.19 In a trial for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia in which the levels of IL-2R are low, DD produced partial responses in only 2 (11%) of 18 patients.20 DD binds tightly to the IL-2R complex but less tightly to the α subunit, which is most commonly found at high levels in T-cell malignancies. Newer constructs have been developed in an attempt to target this lower-affinity IL2 receptor α (CD25).21

LMB-2 (anti-Tac(Fv)-PE38) is a fusion protein in which the Fv portion of an antibody to CD25 is fused to a 38-kDa truncated PE (PE38). LMB-2 was originally evaluated in a phase 1 trial where a maximum-tolerated dose (MTD) of 50 μg/kg given every other day ×3 doses per cycle was established, and an objective response rate (ORR) of 23% including 4 of 4 patients with HCL was seen.22 A phase 2 study of LMB-2 for HCL is in progress. A phase 2 combination trial for adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL) uses cyclophosphamide and fludarabine in an attempt to decrease anti–LMB-2 antibody formation and reduce tumor burden.23 Complete responses (CRs) have been observed on this trial, which is ongoing.24

A ricin-based immunotoxin targeting CD25 (RFT5-dgA, IMTOX-25) has been developed, and a phase 2 study for adults with ATL is underway.

Targeting CD22

CD22 is a lineage-restricted differentiation antigen expressed on B cells and in most B-cell malignancies. Following binding, CD22 is rapidly internalized, making this an excellent target for immunotoxins.10

RFB4-dgA is an immunotoxin composed of a deglycosylated A chain of ricin chemically attached to the RFB4 anti-CD22 antibody.25 This agent has been tested alone and in combination with an anti-CD19 immunotoxin in B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).26 Capillary/vascular leak syndrome (CLS) is a major side effect, and construct modifications have been developed in an attempt to reduce vascular-associated toxicities.27

BL22 (CAT-3888) is a recombinant immunotoxin in which the Fv of the anti-CD22 antibody RFB4 is fused to PE38.28 In the phase 1 trial conducted in adults, 31 patients with HCL showed an ORR of 81% with 61% CRs.29 The dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) was hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), which was completely reversible. In a phase 2 study in HCL, the high response rate was confirmed with an ORR of 72% and 47% CRs.30 CD22 is expressed in nearly all cases of B-lineage ALL in children.31 A pediatric phase 1 trial of BL22 was conducted in which no MTD was defined, although 2 patients treated at the highest dose level developed brief grade 4 alanine aminotransferase elevations. Transient clinical activity was seen in 16 (70%) of 23 patients, but no objective responses were observed on that trial.32

To improve the activity of BL22, a modified agent with higher affinity was developed (moxetumomab pasudotox [HA22; CAT-8015]) by mutating 3 amino acids in the Fv heavy chain CDR3 region from serine-serine-tyrosine (SSY) to threonine-histidine-tryptophan (THW).33,34 Twenty-eight adults with HCL were treated on a phase 1 trial of moxetumomab pasudotox.35 The agent was administered as a 30-minute intravenous infusion every other day ×3 doses with cycles repeated every 4 weeks at doses between 5 and 50 μg/kg. Common drug-related toxicities included grade 1/2 hypoalbuminemia, aminotransferase elevations, edema, headache, hypotension, nausea, and fatigue. DLT was not observed, but completely reversible grade 2 HUS was noted in 2 patients during re-treatment. Major responses were seen at all dose levels, including CRs beginning at 10 μg/kg. The ORR was 86% with a CR rate of 46%. Responses were durable with the median disease-free survival time not reached at 26 months. Neutralizing antibodies developed in 10 (38%) of 26 patients. A phase 2 trial has been completed, and a phase 3 trial is being conducted.36

A pediatric phase 1 trial of moxetumomab pasudotox is in progress. In comparison with the dosing schedule for adults, a more intensive dosing schedule has been developed for children with ALL (every other day ×6 to 10 doses every 21 days). Because 2 of 7 patients treated at 30 μg/kg experienced grade 3/4 CLS, the trial was amended to include prophylactic corticosteroids during the first cycle of therapy. Interim analysis reported clinical activity in 8 (67%) of 12 patients including 3 CRs (25%).37 Phase 2 trials for pediatric ALL are in development, and a phase 1/2 trial for adults with ALL is underway. Preclinical studies indicate that moxetumomab pasudotox is synergistic with standard chemotherapy against childhood ALL blasts, and combination testing is planned.38

Targeting CD19

CD19 is expressed in most B-cell malignancies, and this antigen is internalized sufficiently well to bring cytotoxic compounds into the cell. A number of immunotoxins that target CD19 have undergone early-phase testing in adults and children with leukemia, with some responses and significant toxicity reported. More recently the deglycosylated ricin A chain immunotoxin HD37-dgA has been studied in combination with an anti-CD22 immunotoxin.

Targeting CD19 and CD22

The combination of HD37-dgA and RFB4-dgA (Combotox) has been studied in adults and children with B-lineage hematologic malignancies. In a trial in children with ALL, 17 patients were treated, and an MTD of 5 mg/m2 was established. Three CRs (18%) were observed, and hematologic activity was noted in other patients. There was a high incidence of severe adverse events, and 2 (18%) of 11 developed antidrug antibodies.39 In a phase 1 study in adults with ALL, the MTD was 7 mg/m2 with CLS as the DLT. One patient achieved a partial response, and all patients demonstrated reduction in peripheral blasts.40 A clinical trial of this agent in combination with cytarabine for adults with B-lineage ALL is in progress.41

A bivalent recombinant diphtheria-based immunotoxin has been developed in which one Fv targets CD19 and the other targets CD22 (DT2219ARL). This agent has shown activity in preclinical models and is now in phase 1 testing in adolescents and adults with B-lineage hematologic malignancies including ALL.42

Targeting CD3

CD3 is widely expressed in T-cell malignancies. An anti-CD3 recombinant immunotoxin A-dmDT390-bisFv(UCHT1) is constructed of a divalent molecule consisting of 2 single-chain antibody fragments reactive with the extracellular domain of CD3ε fused to the catalytic and translocation domains of DT.43 This agent is in clinical trials for adults with T-cell malignancies including leukemia.

Targeting CD33

CD33 is expressed on the surface of early multilineage hematopoietic progenitors, myelomonocytic precursors, cells of the monocyte/macrophage system, some lymphoid cells, 80% to 90% of cases of acute myeloid leukemia, and some cases of B-cell precursor and T-cell ALL.

An anti-CD33 immunotoxin consisting of humanized mAb M195 conjugated to recombinant gelonin (HUM-195/rGEL) was tested in a phase 1 study in adults with myeloid leukemias. Dose levels between 12 and 40 mg/m2 were studied, and an MTD of 28 mg/m2 was defined. Dose-limiting infusion-related allergic reactions, hypoxia, and hypotension were observed. Seven of 28 patients showed some reduction in blasts, and 1 patient had platelet count normalization. Anti-gelonin antibodies developed in 2 of 23 patients.44

Newer immunotoxins and combinations

A growing number of new immunotoxins have shown promise in preclinical investigations in myeloid and lymphoid leukemias.45-52 mAb conjugates composed of mammalian toxins such endonucleases, granzymes, and tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligands have also been developed and have been shown to be active against human leukemia in preclinical studies.53-55 Protein engineering has been used to develop new immunotoxin constructs with increased activity and reduced nonspecific toxicities and immunogenicity.13,56,57 Additionally, immunotoxins combined with chemotherapy, novel agents, and immunosuppression offer the potential to increase cytotoxic activity and reduce immunogenicity.23,38,58-60

Immunogenicity and antidrug antibodies

Immunotoxins contain foreign proteins that can induce neutralizing antibody formation in patients with functional immunity. In our experience, the vast majority of individuals with solid tumors treated with protein immunotoxins have made antitoxin antibodies after 1 or 2 cycles of treatment.60 However, when immunotoxins are given to patients with hematologic malignancies, the incidence of antitoxin antibody development is lower (15% to 50%) and generally is not seen until multiple cycles of therapy are administered. For protein toxins to be useful over multiple cycles, especially in patients who are able to mount an immune response, immunogenicity needs to be reduced or suppressed. This can be accomplished in several ways, including immunotoxin construct mutagenesis to remove immunodominant B- and/or T-cell epitopes and coadministration with immunosuppressive agents.

In the case of immunotoxins made from PE, we have been able to identify and remove immunodominant B-cell epitopes recognized by the mouse immune system resulting in an active immunotoxin that can be given repeatedly to mice without inducing antibody formation.61,62 This was accomplished by mutation of specific large hydrophilic amino acids (Arg, Gln, Glu, Lys) to Ala, Ser, or Gly. Human B-cell epitopes have also been mapped and silenced by using a similar approach to that used to eliminate mouse epitopes. The major difference was that antibody phage display technology was used to isolate Fvs from human B-cell RNA and the phage-expressing Fvs used to map the epitopes.63 A recombinant immunotoxin with modified human B-cell epitopes is currently being developed for the treatment of solid tumors.

Coadministration of immunosuppressive drugs can also effectively reduce the incidence of immunogenicity.60 Such approaches to reduce immunogenicity will enable the use of immunotoxins at an earlier point in treatment when patients are less likely to be immunosuppressed.

Pharmacology

In general, the plasma half-life of immunotoxins in humans is relatively short, ranging from approximately 30 minutes to 4 hours. Recombinant immunotoxins were originally designed to be small with the goal of enhancing penetration into solid tumor masses.64 While small size may be useful, it also causes these agents to be rapidly removed from the circulation. It is possible to make recombinant immunotoxins of larger size with improved pharmacology by fusing the toxin to Fabs or to entire antibody molecules and producing these in Escherichia coli.65,66 As indicated above, neutralizing antidrug antibodies commonly develop and, depending on the antibody titer, these can dramatically reduce immunotoxin levels. Notably, patients with preexisting antitoxin antibodies (eg, from diphtheria vaccination or Pseudomonas infection) can develop rapid anamnestic high-titer antibody responses after treatment with the associated immunotoxin.

Mechanisms of resistance

Although recombinant immunotoxins are highly active, not all patients respond, and others develop resistance after prior response. The mechanisms of resistance are likely multifactorial and variable, and these have not yet been fully elucidated. The most well-demonstrated cause of resistance is the development of neutralizing antibodies directed against the toxin component, which leads to rapid clearance of circulating drug levels. Low or absent surface expression of the cognate antigen is another obvious explanation for resistance. For example, occasional cases of MLL-rearranged ALL have been shown to have CD22-negative blast subpopulations.31 Total loss of target antigen expression has been observed after treatment with CD19-targeted bispecific antibodies and chimeric antigen transduced T cells,67,68 although this has not yet been reported after treatment with immunotoxins. Multitargeting with immunotoxins against 2 or more antigens might be used to counter such expression-related resistance mechanisms.

Clearance of peripheral blasts with persistence of bone marrow disease has been seen in patients treated with immunotoxins,32,39 raising the possibility of a protective effect within the marrow. Notably, incomplete immunotoxin-mediated cytotoxicity has been observed when ALL blasts are cultured on bone marrow stromal cells.69 The bone marrow microenvironment could provide survival factors or trigger intracellular signaling pathways that might rescue blasts from immunotoxin-induced apoptosis.70,71 Anatomic factors related to densely packed marrow blasts could also confer resistance, for example through physical or pharmacologic gradients against immunotoxin penetration, which might be offset by combination with chemotherapy.23,72

Reversible resistance to immunotoxin-mediated cytotoxicity in ALL cell lines has been established and demonstrated to be caused by methylation-induced silencing of diphthamide synthesis genes that prevents ADP-ribosylation of elongation factor 2.73,74 This can be prevented and reversed by epigenetic modifiers, which raises the prospect for efficacy of combination therapy if this mechanism is found to be operative in humans. Gene loss of a diphthamide synthesis gene has also been demonstrated in a Burkitt lymphoma line rendered resistant to immunotoxin.75

Toxicities

In general, newer immunotoxin constructs have improved safety profiles in comparison with earlier-generation agents. Common side effects in patients treated with immunotoxins include hepatic aminotransferase elevation, hypoalbuminemia, and infusion reactions. Additionally, there are a few distinct toxicity syndromes associated with immunotoxin therapy.

CLS

The incidence and severity of CLS associated with immunotoxins vary with the specific agent. In the case of ricin-based immunotoxins, this side effect has been attributed to carbohydrate residues on the toxin binding to endothelial cells, which has been diminished but not eliminated by using forms of ricin that do not contain carbohydrate modifications (ie, deglycosylated). Further, a 3-amino-acid motif in deglycosylated ricin toxin A contributes to CLS. While the modification of this sequence reduces pulmonary vascular leak in preclinical models,76 this construct has not been tested in humans. In the case of PE-based immunotoxins, CLS has only rarely been dose limiting, but this syndrome is nonetheless a significant side effect. In a pediatric phase 1 trial of moxetumomab pasudotox, dose-limiting CLS was seen in 2 of 7 patients treated without corticosteroid prophylaxis, which seems to have been eliminated by the use of dexamethasone pretreatment.37 The efficacy of steroid prophylaxis against PE-induced CLS has been demonstrated in a preclinical model.77 Weldon et al have reported on an immunotoxin that has a deletion of a large portion of domain II of PE that is fully cytotoxic yet its nonspecific toxicities in mice, which may reflect the ability of these immunotoxins to cause CLS in patients, are greatly diminished.13

HUS

The occurrence of HUS has been reported in adults and children treated with immunotoxins. In most cases, this has been reversible.30 The mechanism of HUS development is unknown.

Summary

Many years of study and development have led to the use of antibodies or antibody fragments to target potent toxin molecules to leukemia cells. CRs have been observed in many patients, and now additional studies are required to define the optimal dose, schedule, and combinations for specific leukemia subtypes. Several problems have been identified, including immunogenicity, which may be solved by removing immunogenic epitopes through protein engineering. Immunotoxin resistance might be overcome through a variety of modifications and/or combinations. With further improvements, it is anticipated that immunotoxins will have an increasing impact in the treatment of leukemia.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research. Research support for development of some of the immunotoxins described was provided through a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement between the National Cancer Institute and MedImmune, LLC.

Authorship

Contribution: All authors cowrote and edited the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.S.W., R.J.K., D.J.F., and I.P. are inventors of some of the immunotoxins described in this report with all patents held by the National Institutes of Health.

Correspondence: Alan S. Wayne, Children’s Center for Cancer and Blood Diseases, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, 4650 Sunset Blvd, Mailstop #54, Los Angeles, CA 90027; e-mail: awayne@chla.usc.edu.

References

- 1.Scott AM, Allison JP, Wolchok JD. Monoclonal antibodies in cancer therapy. Cancer Immun. 2012;12:14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robak T. Emerging monoclonal antibodies and related agents for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Future Oncol. 2013;9(1):69–91. doi: 10.2217/fon.12.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naik RR, Saven A. My treatment approach to hairy cell leukemia. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(1):67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.FitzGerald DJ, Wayne AS, Kreitman RJ, Pastan I. Treatment of hematologic malignancies with immunotoxins and antibody-drug conjugates. Cancer Res. 2011;71(20):6300–6309. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chu YW, Polson A. Antibody-drug conjugates for the treatment of B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and leukemia. Future Oncol. 2013;9(3):355–368. doi: 10.2217/fon.12.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharkey RM, Goldenberg DM. Cancer radioimmunotherapy. Immunotherapy. 2011;3(3):349–370. doi: 10.2217/imt.10.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antignani A, Fitzgerald D. Immunotoxins: the role of the toxin. Toxins (Basel). 2013;5(8):1486-1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Pastan I, Hassan R, FitzGerald DJ, Kreitman RJ. Immunotoxin treatment of cancer. Annu Rev Med. 2007;58:221–237. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.58.070605.115320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roy DC, Griffin JD, Belvin M, Blättler WA, Lambert JM, Ritz J. Anti-MY9-blocked-ricin: an immunotoxin for selective targeting of acute myeloid leukemia cells. Blood. 1991;77(11):2404–2412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Du X, Beers R, Fitzgerald DJ, Pastan I. Differential cellular internalization of anti-CD19 and -CD22 immunotoxins results in different cytotoxic activity. Cancer Res. 2008;68(15):6300–6305. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erickson HK, Park PU, Widdison WC, et al. Antibody-maytansinoid conjugates are activated in targeted cancer cells by lysosomal degradation and linker-dependent intracellular processing. Cancer Res. 2006;66(8):4426–4433. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sutherland MS, Sanderson RJ, Gordon KA, et al. Lysosomal trafficking and cysteine protease metabolism confer target-specific cytotoxicity by peptide-linked anti-CD30-auristatin conjugates. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(15):10540–10547. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510026200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weldon JE, Xiang L, Chertov O, et al. A protease-resistant immunotoxin against CD22 with greatly increased activity against CLL and diminished animal toxicity. Blood. 2009;113(16):3792–3800. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-173195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ogata M, Chaudhary VK, Pastan I, FitzGerald DJ. Processing of Pseudomonas exotoxin by a cellular protease results in the generation of a 37,000-Da toxin fragment that is translocated to the cytosol. J Biol Chem. 1990;265(33):20678–20685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moreau D, Kumar P, Wang SC, et al. Genome-wide RNAi screens identify genes required for Ricin and PE intoxications. Dev Cell. 2011;21(2):231–244. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiron MF, Ogata M, FitzGerald DJ. Pseudomonas exotoxin exhibits increased sensitivity to furin when sequences at the cleavage site are mutated to resemble the arginine-rich loop of diphtheria toxin. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22(4):769–778. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.d01-1721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKee ML, FitzGerald DJ. Reduction of furin-nicked Pseudomonas exotoxin A: an unfolding story. Biochemistry. 1999;38(50):16507–16513. doi: 10.1021/bi991308+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malek TR, Castro I. Interleukin-2 receptor signaling: at the interface between tolerance and immunity. Immunity. 2010;33(2):153–165. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manoukian G, Hagemeister F. Denileukin diftitox: a novel immunotoxin. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2009;9(11):1445–1451. doi: 10.1517/14712590903348135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frankel AE, Surendranathan A, Black JH, White A, Ganjoo K, Cripe LD. Phase II clinical studies of denileukin diftitox diphtheria toxin fusion protein in patients with previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. 2006;106(10):2158–2164. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Potala S, Verma RS. Modified DT-IL2 fusion toxin targeting uniquely IL2Ralpha expressing leukemia cell lines - Construction and characterization. J Biotechnol. 2010;148(2-3):147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kreitman RJ, Wilson WH, White JD, et al. Phase I trial of recombinant immunotoxin anti-Tac(Fv)-PE38 (LMB-2) in patients with hematologic malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(8):1622–1636. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.8.1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh R, Zhang Y, Pastan I, Kreitman RJ. Synergistic antitumor activity of anti-CD25 recombinant immunotoxin LMB-2 with chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(1):152–160. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kreitman RJ, Singh R, Stetler-Stevenson M, Waldmann TA, Pastan I. Regression of adult T-cell leukemia with anti-CD25 recombinant immunotoxin LMB-2 preceded by chemotherapy [abstract]. Blood. 2011;118(21) Abstract 2575. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amlot PL, Stone MJ, Cunningham D, et al. A phase I study of an anti-CD22-deglycosylated ricin A chain immunotoxin in the treatment of B-cell lymphomas resistant to conventional therapy. Blood. 1993;82(9):2624–2633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Messmann RA, Vitetta ES, Headlee D, et al. A phase I study of combination therapy with immunotoxins IgG-HD37-deglycosylated ricin A chain (dgA) and IgG-RFB4-dgA (Combotox) in patients with refractory CD19(+), CD22(+) B cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6(4):1302–1313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu XY, Pop LM, Schindler J, Vitetta ES. Immunotoxins constructed with chimeric, short-lived anti-CD22 monoclonal antibodies induce less vascular leak without loss of cytotoxicity. MAbs. 2012;4(1):57–68. doi: 10.4161/mabs.4.1.18348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mansfield E, Amlot P, Pastan I, FitzGerald DJ. Recombinant RFB4 immunotoxins exhibit potent cytotoxic activity for CD22-bearing cells and tumors. Blood. 1997;90(5):2020–2026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kreitman RJ, Wilson WH, Bergeron K, et al. Efficacy of the anti-CD22 recombinant immunotoxin BL22 in chemotherapy-resistant hairy-cell leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(4):241–247. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107263450402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kreitman RJ, Stetler-Stevenson M, Margulies I, et al. Phase II trial of recombinant immunotoxin RFB4(dsFv)-PE38 (BL22) in patients with hairy cell leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(18):2983–2990. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.2630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haso W, Lee DW, Shah NN, et al. Anti-CD22-chimeric antigen receptors targeting B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2013;121(7):1165–1174. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-438002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wayne AS, Kreitman RJ, Findley HW, et al. Anti-CD22 immunotoxin RFB4(dsFv)-PE38 (BL22) for CD22-positive hematologic malignancies of childhood: preclinical studies and phase I clinical trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(6):1894–1903. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salvatore G, Beers R, Margulies I, Kreitman RJ, Pastan I. Improved cytotoxic activity toward cell lines and fresh leukemia cells of a mutant anti-CD22 immunotoxin obtained by antibody phage display. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(4):995–1002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kreitman RJ, Pastan I. Antibody fusion proteins: anti-CD22 recombinant immunotoxin moxetumomab pasudotox. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(20):6398–6405. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kreitman RJ, Tallman MS, Robak T, et al. Phase I trial of anti-CD22 recombinant immunotoxin moxetumomab pasudotox (CAT-8015 or HA22) in patients with hairy cell leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(15):1822–1828. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kreitman RJ. Hairy cell leukemia-new genes, new targets. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2013;8(3):184–195. doi: 10.1007/s11899-013-0167-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wayne AS, Bhojwani D, Silverman LB, et al. A novel anti-CD22 immunotoxin, moxetumomab pasudotox: Phase I study in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) [abstract]. Blood. 2011;118(21):1317a. Abstract 248. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahuja Y, Stetler-Stevenson M, Kreitman RJ, Pastan I, Wayne AS. Pre-clinical evaluation of the anti-CD22 immunotoxin CAT-8015 in combination with chemotherapy agents for childhood B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Pre-B ALL) [abstract]. Blood. 2007;110(11):265a. Abstract 865. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herrera L, Bostrom B, Gore L, et al. A phase 1 study of Combotox in pediatric patients with refractory B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2009;31(12):936–941. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181bdf211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schindler J, Gajavelli S, Ravandi F, et al. A phase I study of a combination of anti-CD19 and anti-CD22 immunotoxins (Combotox) in adult patients with refractory B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2011;154(4):471–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08762.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barta SK, Zou Y, Schindler J, et al. Synergy of sequential administration of a deglycosylated ricin A chain-containing combined anti-CD19 and anti-CD22 immunotoxin (Combotox) and cytarabine in a murine model of advanced acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53(10):1999–2003. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2012.679267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vallera DA, Chen H, Sicheneder AR, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Taras EP. Genetic alteration of a bispecific ligand-directed toxin targeting human CD19 and CD22 receptors resulting in improved efficacy against systemic B cell malignancy. Leuk Res. 2009;33(9):1233–1242. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frankel AE, Zuckero SL, Mankin AA, et al. Anti-CD3 recombinant diphtheria immunotoxin therapy of cutaneous T cell lymphoma. Curr Drug Targets. 2009;10(2):104–109. doi: 10.2174/138945009787354539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Borthakur G, Rosenblum MG, Talpaz M, et al. Phase 1 study of an anti-CD33 immunotoxin, humanized monoclonal antibody M195 conjugated to recombinant gelonin (HUM-195/rGEL), in patients with advanced myeloid malignancies. Haematologica. 2013;98(2):217–221. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.071092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhu X, Tao K, Li Y, et al. A new recombinant immunotoxin hscFv-ETA' demonstrates specific cytotoxicity against chronic myeloid leukemia cells in vitro. Immunol Lett. 2013;154(1-2):18-24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Li S, Tang Y, Zhang J, Guo X, Shen H. 3A4, a new potential target for B and myeloid lineage leukemias. J Drug Target. 2011;19(9):797–804. doi: 10.3109/1061186X.2011.572973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kato J, Satake N, O’Donnell RT, Abuhay M, Lewis C, Tuscano JM. Efficacy of a CD22-targeted antibody-saporin conjugate in a xenograft model of precursor-B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk Res. 2013;37(1):83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dave H, Anver MR, Butcher DO, et al. Restricted cell surface expression of receptor tyrosine kinase ROR1 in pediatric B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia suggests targetability with therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12):e52655. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baskar S, Wiestner A, Wilson WH, Pastan I, Rader C. Targeting malignant B cells with an immunotoxin against ROR1. MAbs. 2012;4(3):349–361. doi: 10.4161/mabs.19870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tur MK, Huhn M, Jost E, Thepen T, Brümmendorf TH, Barth S. In vivo efficacy of the recombinant anti-CD64 immunotoxin H22(scFv)-ETA’ in a human acute myeloid leukemia xenograft tumor model. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(5):1277–1282. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Polito L, Bortolotti M, Farini V, Pedrazzi M, Tazzari PL, Bolognesi A. ATG-saporin-S6 immunotoxin: a new potent and selective drug to eliminate activated lymphocytes and lymphoma cells. Br J Haematol. 2009;147(5):710–718. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dalmazzo LF, Santana-Lemos BA, Jácomo RH, et al. Antibody-targeted horseradish peroxidase associated with indole-3-acetic acid induces apoptosis in vitro in hematological malignancies. Leuk Res. 2011;35(5):657–662. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2010.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mathew M, Zaineb KC, Verma RS. GM-CSF-DFF40: a novel humanized immunotoxin induces apoptosis in acute myeloid leukemia cells. Apoptosis. 2013;18(7):882–895. doi: 10.1007/s10495-013-0840-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schiffer S, Letzian S, Jost E, et al. Granzyme M as a novel effector molecule for human cytolytic fusion proteins: CD64-specific cytotoxicity of Gm-H22(scFv) against leukemic cells. Cancer Lett. 2013;341(2):178–185. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.ten Cate B, Bremer E, de Bruyn M, et al. A novel AML-selective TRAIL fusion protein that is superior to Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin in terms of in vitro selectivity, activity and stability. Leukemia. 2009;23(8):1389–1397. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kawa S, Onda M, Ho M, Kreitman RJ, Bera TK, Pastan I. The improvement of an anti-CD22 immunotoxin: conversion to single-chain and disulfide stabilized form and affinity maturation by alanine scan. MAbs. 2011;3(5):479–486. doi: 10.4161/mabs.3.5.17228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pastan I, Onda M, Weldon J, Fitzgerald D, Kreitman R. Immunotoxins with decreased immunogenicity and improved activity. Leuk Lymphoma. 2011;52(Suppl 2):87–90. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2011.573039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fitzgerald DJ, Moskatel E, Ben-Josef G, et al. Enhancing immunotoxin cell-killing activity via combination therapy with ABT-737. Leuk Lymphoma. 2011;52(Suppl 2):79–81. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2011.569961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Biberacher V, Decker T, Oelsner M, et al. The cytotoxicity of anti-CD22 immunotoxin is enhanced by bryostatin 1 in B-cell lymphomas through CD22 upregulation and PKC-βII depletion. Haematologica. 2012;97(5):771–779. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.049155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hassan R, Miller AC, Sharon E, et al. Major cancer regressions in mesothelioma after treatment with an anti-mesothelin immunotoxin and immune suppression. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(208):208ra147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Onda M, Beers R, Xiang L, Nagata S, Wang QC, Pastan I. An immunotoxin with greatly reduced immunogenicity by identification and removal of B cell epitopes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(32):11311–11316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804851105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Onda M, Beers R, Xiang L, et al. Recombinant immunotoxin against B-cell malignancies with no immunogenicity in mice by removal of B-cell epitopes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(14):5742–5747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102746108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu W, Onda M, Lee B, et al. Recombinant immunotoxin engineered for low immunogenicity and antigenicity by identifying and silencing human B-cell epitopes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(29):11782–11787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209292109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pastan I, Hassan R, Fitzgerald DJ, Kreitman RJ. Immunotoxin therapy of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(7):559–565. doi: 10.1038/nrc1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bera TK, Pastan I. Comparison of recombinant immunotoxins against LeY antigen expressing tumor cells: influence of affinity, size, and stability. Bioconjug Chem. 1998;9(6):736–743. doi: 10.1021/bc980028o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hakim R, Benhar I. “Inclonals”: IgGs and IgG-enzyme fusion proteins produced in an E. coli expression-refolding system. MAbs. 2009;1(3):281–287. doi: 10.4161/mabs.1.3.8492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Topp MS, Kufer P, Gökbuget N, et al. Targeted therapy with the T-cell-engaging antibody blinatumomab of chemotherapy-refractory minimal residual disease in B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients results in high response rate and prolonged leukemia-free survival. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(18):2493–2498. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.7270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Grupp SA, Kalos M, Barrett D, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells for acute lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(16):1509–1518. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mussai FJ, Campana D, Bhojwani D, et al. Cytotoxicity of the anti-CD22 immunotoxin HA22 (CAT-8015) against paediatric acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2010;150(3):352–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08251.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hsieh YT, Gang EJ, Geng H, et al. Integrin alpha4 blockade sensitizes drug resistant pre-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia to chemotherapy. Blood. 2013;121(10):1814–1818. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-406272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pramanik R, Sheng X, Ichihara B, Heisterkamp N, Mittelman SD. Adipose tissue attracts and protects acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells from chemotherapy. Leuk Res. 2013;37(5):503–509. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang Y, Hansen JK, Xiang L, et al. A flow cytometry method to quantitate internalized immunotoxins shows that taxol synergistically increases cellular immunotoxins uptake. Cancer Res. 2010;70(3):1082–1089. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hu X, Wei H, Xiang L, et al. Methylation of the DPH1 promoter causes immunotoxin resistance in acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell line KOPN-8. Leuk Res. 2013;37(11):1551–1556. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wei H, Xiang L, Wayne AS, et al. Immunotoxin resistance via reversible methylation of the DPH4 promoter is a unique survival strategy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(18):6898–6903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204523109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wei H, Bera TK, Wayne AS, et al. A modified form of diphthamide causes immunotoxin resistance in a lymphoma cell line with a deletion of the WDR85 gene. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(17):12305–12312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.461343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Smallshaw JE, Ghetie V, Rizo J, et al. Genetic engineering of an immunotoxin to eliminate pulmonary vascular leak in mice. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21(4):387–391. doi: 10.1038/nbt800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Siegall CB, Liggitt D, Chace D, Tepper MA, Fell HP. Prevention of immunotoxin-mediated vascular leak syndrome in rats with retention of antitumor activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91(20):9514–9518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]