Abstract

IMPORTANCE

The search for novel Alzheimer disease (AD) genes or pathologic mutations within known AD loci is ongoing. The development of array technologies has helped to identify rare recessive mutations among long runs of homozygosity (ROHs), in which both parental alleles are identical. Caribbean Hispanics are known to have an elevated risk for AD and tend to have large families with evidence of inbreeding.

OBJECTIVE

To test the hypothesis that the late-onset AD in a Caribbean Hispanic population might be explained in part by the homozygosity of unknown loci that could harbor recessive AD risk haplotypes or pathologic mutations.

DESIGN

We used genome-wide array data to identify ROHs (>1 megabase) and conducted global burden and locus-specific ROH analyses.

SETTING

A whole-genome case-control ROH study.

PARTICIPANTS

A Caribbean Hispanic data set of 547 unrelated cases (48.8% with familial AD) and 542 controls collected from a population known to have a 3-fold higher risk of AD vs non-Hispanics in the same community. Based on a Structure program analysis, our data set consisted of African Hispanic (207 cases and 192 controls) and European Hispanic (329 cases and 326 controls) participants.

EXPOSURE

Alzheimer disease risk genes.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES

We calculated the total and mean lengths of the ROHs per sample. Global burden measurements among autosomal chromosomes were investigated in cases vs controls. Pools of overlapping ROH segments (consensus regions) were identified, and the case to control ratio was calculated for each consensus region. We formulated the tested hypothesis before data collection.

RESULTS

In total, we identified 17 137 autosomal regions with ROHs. The mean length of the ROH per person was significantly greater in cases vs controls (P = .0039), and this association was stronger with familial AD (P = .0005). Among the European Hispanics, a consensus region at the EXOC4 locus was significantly associated with AD even after correction for multiple testing (empirical P value 1 [EMP1], .0001; EMP2, .002; 21 AD cases vs 2 controls). Among the African Hispanic subset, the most significant but nominal association was observed for CTNNA3, a well-known AD gene candidate (EMP1, .002; 10 AD cases vs 0 controls).

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

Our results show that ROHs could significantly contribute to the etiology of AD. Future studies would require the analysis of larger, relatively inbred data sets that might reveal novel recessive AD genes. The next step is to conduct sequencing of top significant loci in a subset of samples with overlapping ROHs.

Alzheimer disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia, characterized by neurotoxic aggregates of tau and β-amyloid peptides in the brain.1 Known genetic factors account for only up to 40% of the risk for AD, half of which is attributable to APOE and approximately 3% to dominant mutations in APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2.2,3 Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have identified associations between late-onset AD (age >65 years) and single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in 9 loci (CLU, PICALM, BIN1, MS4A4/MS4A6E, CR1, CD2AP, CD33, EPHA1, and ABCA7)4–8 in which the pathogenic variants have not yet been revealed apart from CR1.9 In addition, a candidate gene approach discovered a reproducible association between AD and SORL1,10 and a recent exome study revealed AD risk variants in TREM2.11 Finally, the G4C2-repeat expansion in C9orf72 has been recently reported in a few patients with clinical AD12,13; however, this association remains to be validated.14

Intriguingly, a recent study on the concordance of AD among parents and offspring suggested that approximately 90% of early-onset AD cases are likely the result of autosomal recessive inheritance15; however, the p.A673V substitution in APP is the only known recessive AD mutation.16 Recessive inheritance has not been widely investigated for complex traits. The lack of inbred families in most North American or European data sets has made mapping of recessive loci challenging; however, the development of array technologies has recently helped to identify rare recessive mutations among long runs of homozygosity (ROHs), in which both parental alleles are identical.17,18 In addition, ROHs can harbor imprinted chromosomes19,20 or risk haplotypes that predispose to a disorder in a homozygous state.21,22 Runs of homozygosity could be inherited from a common ancestor many generations back,23 and longer ROHs are expected in closely related individuals (identical by descent) or inbred populations.24,25 Runs of homozygosity greater than 1 megabase (Mb) are relatively frequent in the general population and could arise without inbreeding as a result of common extended haplotypes at loci with rare recombination events.26 Small ROHs (<1 Mb) are too frequent (especially in inbred populations) to search for rare recessive loci, and therefore most ROH studies use a 1-Mb cutoff.27,28

At present, ROHs have been associated with a risk for rheumatoid arthritis,21 Parkinson disease,29 and schizophrenia.30 Recently, genome-wide measurements of ROHs (>1 Mb)were studied in 2 outbred AD data sets of North American and European origin.27,28 In both studies, the global burden analysis of ROHs did not reveal a significant association with AD. The only significant result in locus-specific analyses was obtained for a consensus ROH region on chr8p12 in the North American data set (P = .017; 40 AD cases vs 9 controls),27 but no loci survived correction for multiple testing in the European data set.28 Surprisingly, homozygosity mapping of a small data set from an isolated Arab community in Israel (Wadi Ara) detected that the controls were more inbred than the AD cases.31 In addition, a whole-genome study of 2 affected siblings from a consanguineous AD family revealed several shared ROHs; however, lack of data from unaffected family members complicated the result interpretation.32

In the present study, we investigated a late-onset AD data set of a Caribbean Hispanic population for global burden measurements of ROHs and the specific loci that could harbor recessive AD mutations or risk haplotypes. This data set was previously analyzed in an SNP-based GWAS that replicated several AD genes (APOE, CLU, PICALM, and BIN1).33 We also evaluated the data set for the incidence of rare (>100 kilobase [kb]) copy number variations, but only a nominal association with AD was detected for a duplication on chr15q11.34

The Caribbean Hispanic population in our study originates mainly from the Dominican Republic or from Puerto Rico, which share a complex heritage.35 The native populations of both islands dwindled owing to disease, warfare, and forced labor after the Spanish conquered them in the 15th century, and large numbers of slaves were later imported from West Africa.35–37 At present, the population of the Dominican Republic is 9.8 million; that of Puerto Rico, 3.7 million.38

Caribbean Hispanics are known to have a 3-fold-higher risk for AD compared with non-Hispanics in the same community39 and tend to have large families (≥6 siblings) with evidence of inbreeding, which makes this population very appropriate for an ROH study. A previous study found a single-founder PSEN1 mutation (p.G206A) that was unique to Caribbean Hispanics and responsible for 42% of early-onset AD families in this population.35 However, the high incidence of late-onset AD in this population is not explained by PSEN1.35,39 Hence, we tested the hypothesis that the late-onset AD in the Caribbean Hispanic population might be in part explained by the homozygosity of unknown loci.

Methods

Sample Collection and Genotyping

This study was approved by the institutional review boards of Columbia University and the University of Toronto. We examined a Caribbean Hispanic case-control data set.33,34 Briefly, the data set was composed of 542 unrelated control subjects (68.5% female) and 547 unrelated AD cases (70.7% female), including 267 cases who had at least 1 relative with AD, representing familial AD (FAD). Family history of AD was also recorded for 47 controls (8.7%); however, none had any AD symptoms at the time of examination (mean age, 82 years). The mean (SD) age at onset of AD was 80 (8) years, and the mean (SD) age at the last examination of the controls was 79 (6) years. Analysis with the STRUCTURE program (http://pritch.bsd.uchicago.edu/software.html) had previously determined that 207 AD cases were of African ancestry and 329 cases were of European ancestry; 192 controls were of African ancestry and 326 controls were of European ancestry (11 cases and 24 controls were of unknown ancestry).33 The proportion of both subgroups was similar in cases and controls: African Hispanics made up 37.8% of cases and 35.4% of controls, whereas European Hispanics made up 60.1% of cases and 60.1% of controls.

All DNA samples were isolated from whole blood and genotyped on the Illumina HumanHap 650Y array (Illumina, Inc). The genotyping success rate was greater than 99% for all samples, providing a reliable source to estimate the ROHs. We included in this study only samples that previously passed stringent SNP-based quality control.33 The raw genotype data have been submitted to the Gene Expression Omnibus, a public functional genomics data repository at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (GSE33528).

Identification and Analysis of ROHs

Runs of homozygosity were identified using a whole-genome association analysis toolset (PLINK; http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/~purcell/plink/), which has a reliable algorithm for ROH detection.40 As previously described, we used a sliding window of 50 SNPs across the genome with no more than 1 heterozygous SNP allowed in the window, and the minimal ROH size was defined as 1 Mb with an SNP density of at least 1 SNP per 50 kb.27,28 We calculated the total and mean lengths of the ROHs per sample and the total number of ROHs for each sample. Global burden measurements among autosomal chromosomes were investigated in cases vs controls with a 1-tailed test (10 000 permutations) for the number of ROHs and for the total and mean ROH lengths per individual (as in published ROH studies27,28). We used a 1-tailed test because the Caribbean Hispanic population has a high incidence of AD39 and is more suitable for the detection of risk and not of protective alleles.

Pools of overlapping ROH segments were identified for the entire data set, and we calculated the ratio of cases to controls for each consensus region, defined as a shared segment of greater than 100 kb (>3 SNPs)among cases and controls. Runs of homozygosity were checked globally among the entire data set and each subgroup using the PLINK regional test against the consensus regions. The PLINK grouping function was also applied to cluster the ROH segments if they were at least 99% identical by genotype.

The standardized, pairwise Lewontin disequilibrium co-efficient was used to estimate the strength of linkage disequilibrium between SNPs using the Haploview software package.41 In addition, we estimated inbreeding (F) using the SNPs from the Illumina HumanHap 650Y array to determine identity by descent as estimated by the genetic relationship matrix, which was implemented in the Genome-wide Complex Trait Analysis.42,43

Results

Global Burden Analysis of ROHs

In total, we identified 17 137 autosomal regions with ROHs greater than 1 Mb (8912 in 542 controls and 8225 in 547 AD cases), including 4041 ROHs in 267 FAD cases (Table). The global burden measurements of rate and total size of ROHs were not associated with AD. However, AD was significantly associated with a larger mean ROH size per person: 2133 kb in cases vs 1934 kb in controls (P = .0039). This association was stronger with FAD (P = .0005). Also, the total size of ROHs per person was marginally longer in FAD cases (40 Mb) vs controls (34 Mb) (P = .05), which could be the result of consanguineous marriages in this island population. Indeed, in our cohort, we observed a noticeable inbreeding comparable to second-cousin marriages (mean F = 0.020). The mean degree of inbreeding was even higher in the 2 subgroups, which was more evident in the European Hispanics (F = 0.055) than in the African Hispanics (F = 0.046).

Table.

Global Burden Analyses of ROHs

| Entire Data Set | |||

|

AD Cases (n = 547) |

Controls (n = 542) |

P Value | |

| No. of ROHs | 8225 | 8912 | |

| Rate, ROHs per person | 15.04 | 16.44 | .99 |

| Total distance spanned by ROHs per person, kb | 36 200 | 34 300 | .23 |

| Mean ROH size per person, kb | 2133 | 1934 | .0039 |

| Familial AD Subgroup | |||

|

AD Cases (n = 267) |

Controls (n = 542) |

P Value | |

| No. of ROHs | 4041 | 8912 | |

| Rate, ROHs per person | 15.13 | 16.44 | .94 |

| Total distance spanned by ROHs per person, kb | 39 600 | 34 300 | .05 |

| Mean ROH size per person, kb | 2260 | 1934 | .0005 |

| African Hispanic Subgroup | |||

|

AD Cases (n = 207) |

Controls (n = 192) |

P Value | |

| No. of ROHs | 1858 | 1700 | |

| Rate, ROHs per person | 8.98 | 8.85 | .39 |

| Total distance spanned by ROHs per person, kb | 21 180 | 17 640 | .07 |

| Mean ROH size per person, kb | 2014 | 1875 | .12 |

| European Hispanic Subgroup | |||

|

AD Cases (n = 329) |

Controls (n = 326) |

P Value | |

| No. of ROHs | 5949 | 5966 | |

| Rate, ROHs per person | 18.08 | 18.30 | .65 |

| Total distance spanned by ROHs per person, kb | 44 550 | 40 190 | .11 |

| Mean ROH size per person, kb | 2221 | 1994 | .013 |

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer disease; kb, kilobase; ROHs, runs of homozygosity.

The global burden analysis was extended to the population subgroups, as defined by the Structure program. Alzheimer disease was significantly associated with larger mean lengths of ROH in the European Hispanic subgroup (P = .013), which also had a 2-fold greater total ROH size per individual compared with the African Hispanic subgroup (Table).

Association Analysis of Gene-Intersecting ROHs

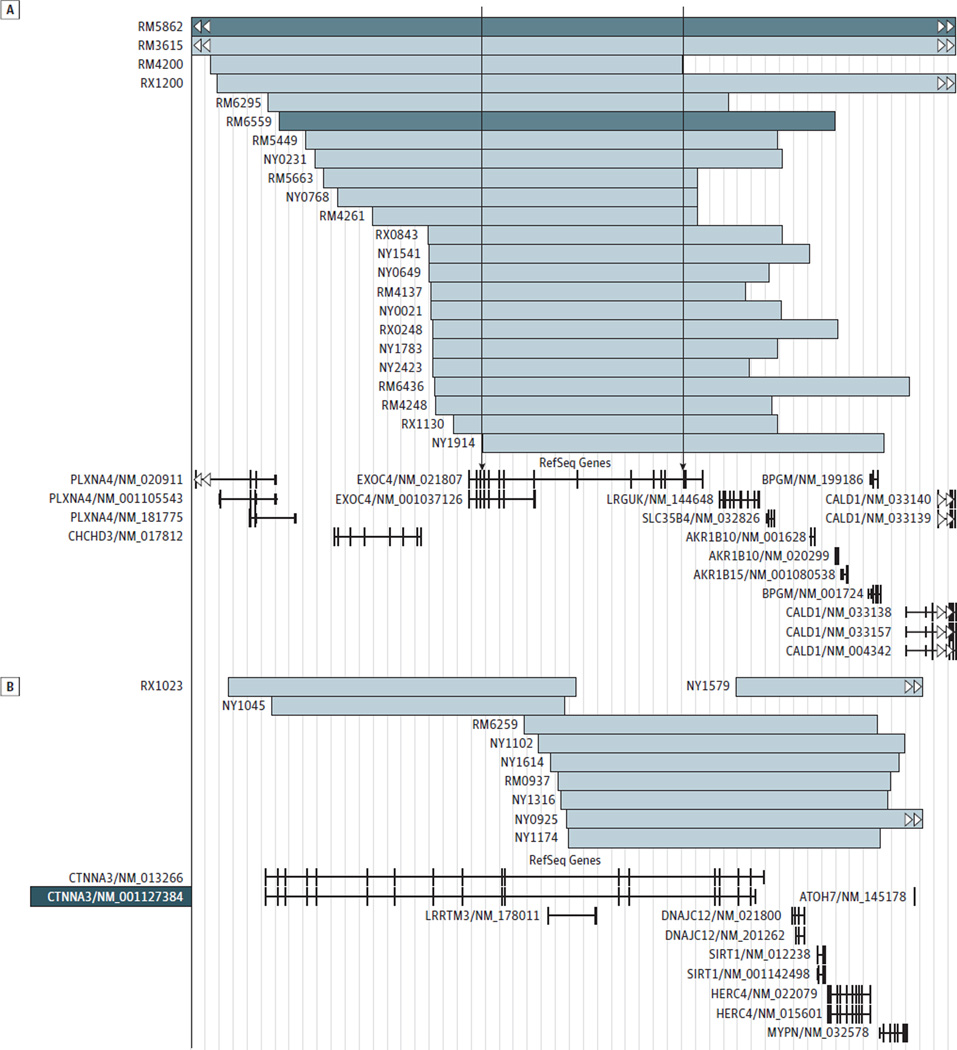

We estimated which genes were intersected by ROHs more frequently in cases vs controls. This locus-specific analysis of the entire data set did not reveal significant findings after correction for multiple testing. The most significant nominal association with AD was observed for the ROHs at chr7q33 intersecting EXOC4 (NM_021807.3) (empirical P value 1 [EMP1], .0006; 28 cases vs 8 controls). In the European Hispanic population, we observed a significant association between AD and EXOC4- intersecting ROHs even after correction for multiple tests (EMP1, .0001; EMP2, .009; 21 AD cases vs 2 controls) (Figure, A). The presence of EXOC4-intersecting ROHs was confirmed by manual inspection of the B-allele frequency and log R ratio plots in GenomeStudio Data Analysis Software (Illumina, Inc) (Supplement [eFigure 1]). Although no locus survived correction for multiple tests in the African Hispanic population, CTNNA3 (NM_013266.2) with its nested gene (LRRTM3 [NM_178011.3]) on chr10q21.3 revealed the strongest nominal association with AD (EMP1, .002). Runs of homozygosity–intersecting CTNNA3 were detected in 10 cases but not in controls (Figure, B). Based on previous copy number variation analysis, the homozygosity at the EXOC4 and CTNNA3 loci cannot be explained by the presence of large deletions.34

Figure. Runs of Homozygosity (ROHs) in a Subset of Caribbean Hispanic Samples.

Runs of homozygosity intersect the EXOC4 gene (A) and the CTNNA3 gene (B). Light blue bars represent ROHs in cases with Alzheimer disease; dark blue bars, ROHs in controls. The arrows represent the physical ROH consensus.

We did not detect any significant findings for ROHs intersecting SORL1, TREM2,APOE, or the 9 AD loci identified by recent large GWASs.4–8 Among known AD loci, the only nominal association with AD was detected in the European Hispanic subgroup for CLU (EMP1, .038; 7 cases vs 1 control). Of note, although AD in our cohort was strongly associated with the APOE ε4/ε4 genotype,33 we found no difference in the frequencies of APOE-intersecting ROHs between cases (5 individuals, including 3 with 3/3, 1 with 2/2, and 1 with 4/4 genotypes) and controls (4 individuals, all with genotype 3/3). Hence, in a Caribbean Hispanic population, the frequency of extended APOE haplotypes is low, as in other reported populations.27,28

Analyses of ROH Consensus Regions

In the entire data set, we identified 1415 consensus regions (defined as the region shared by all individuals carrying an ROH at a given locus), but none of them was associated with AD after correction for multiple testing(Supplement [eTable 1]). However, in the European Hispanic population, a homozygous segment overlapping EXOC4 was significantly associated with AD even after correction for multiple testing (EMP1, .0001; EMP2, .002; 21 cases vs 2 controls). This consensus region was flanked by rs7793621 and rs7792010 located at chr7:132988570-133681101 (hg19) (Supplement [eFigure 2 and eTable 2]). In the African Hispanic population, the most significant nominal association was observed for the consensus region overlapping CTNNA3 (EMP1, .004), but no region survived correction for multiple testing (Supplement [eTable 3]). Consensus regions of CTNNA3 and EXOC4 have several rare, potentially functional coding variations, including missense and nonsense SNPs, according to dbSNP137 (Supplement [eTable 4]).

In addition, we evaluated the samples with ROHs at EXOC4 for genotypic identity using the PLINK grouping function. The largest subgroup with more than 99% identical genotypes consisted of 11 cases (including 9 European Hispanics) and 1 control of African Hispanic ancestry (Supplement [eTable 5]). Manual inspection of the genotypes of these 12 individuals (Supplement [eTable 6]) confirmed the shared haplotype that extends from the 5′-untranslated region to exon 14 of EXOC4, including the Sec8-exocyst domain (PF04048). The controls of European Hispanic origin (n = 326) were used to study the linkage disequilibrium structure around EXOC4. The shared haplotype observed in the 9 European Hispanics belongs to a linkage disequilibrium block that contains only EXOC4(Supplement [eFigure 2]).

Discussion

Our results suggest the existence of recessive AD risk loci in the Caribbean Hispanic population. We detected an association between AD and a larger genome-wide mean ROH size (P = .0039), which was stronger with FAD (P = .0005). The previous studies on global burden measurements of ROHs did not identify any association with AD, likely owing to the outbred nature of the investigated North American and European data sets.27,28 In contrast, our study had greater power to detect association with ROHs because we studied a more homogeneous population with noticeable inbreeding. Of note, total ROH size was 2 times longer in the European Hispanic subset than in the African Hispanic subset, indicating closer relatedness in the European Hispanic population, in which we detected the association between AD and a larger mean ROH size (P = .013).

The association of ROHs with AD could reflect the cumulative effects of multiple ROHs widely distributed throughout the genome (as in schizophrenia44) or the contribution of specific loci harboring recessive mutations and/or risk haplotypes in a subset of patients with AD. In the gene-based approach, the most significant result (EMP2, .009) was observed in the European Hispanics for EXOC4, encoding a component of the exocyst complex involved in the trafficking of the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor.45–47 In the African Hispanic population, the strongest but nominal association was found for CTNNA3, which is a previously reported functional and positional AD gene candidate (also known as VR22 or α-3-catenin). The CTNNA3 protein is a binding partner of β-catenin, and the complex of α/β-catenin interacts with presenilin 1, promoting cadherin processing.48–52 The CTNNA3 gene is mapped to 10q22.2 within an AD locus (OMIM 605526).53,54 Furthermore, CTNNA3 was suggested as an APOE-dependent AD gene55–57 and reported to influence the level of β-amyloid 42 in late-onset AD families.58 Finally, an association between AD and a block of CTNNA3 SNPs in our Caribbean Hispanic data set was recently described.59 Hence, the present study further supports the role of CTNNA3 in AD.

The EXOC4 and CTNNA3 proteins are part of a pathway responsible for the “stabilization and expansion of the E-cadherin adherens junction,” according to the Pathway Interaction Database (http://pid.nci.nih.gov/index.shtml). Also, both proteins are implicated in the “Arf6 trafficking events” pathway, involved in endocytosis and vesicular transport by acting on membrane lipid composition and actin organization.60,61

In the analysis of ROH consensus regions, only the EXOC4 locus among European Hispanics survived correction for multiple testing. In total, we observed 61 consensus regions nominally associated with AD, which could not be explained by the presence of large copy number variations.34 Some of these regions are mapped near known GWAS-significant SNPs (<1 Mb). For instance, the consensus region at chr8p21.1 (11 cases vs 1 control) is near the CLU gene.4,5,7,62 Two other consensus regions are close to the significant SNPs detected in the African American GWAS: rs10850408 (chr12q24.21) and rs2221154 (chr3p24.1).63 The regions on chr3p26.1 and chr4p15.1 were close to significant SNPs identified in a meta-analysis of AD age at onset (rs271066 and rs10517270, respectively).64 Finally, among the largest consensus regions (>1 Mb) on chr21q21.1, chr4p15.2, and chr8p23.3, the locus on chr21q21.1 (EMP1, .004; 8 AD cases vs 0 controls) contains the neural cell adhesion molecule 2 gene (NCAM2). Of note, the SNPs in NCAM2 were reported to be associated with β-amyloid levels in cerebrospinal fluid.65

In summary, we found that ROHs could significantly contribute to the etiology of AD in a population with noticeable inbreeding. Future studies would require the analysis of larger data sets, including association tests with regression analysis incorporating the principal components of a population (eg, age and sex). To characterize the molecular defects underlying AD, the next step is to conduct deep sequencing of top significant loci in a subset of samples with overlapping ROHs, followed by segregation studies in families affected by potential pathologic mutations.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This work was supported by grants R37-AG15473 (Dr Mayeux) and P01-AG07232 from the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health; by the Blanchett Hooker Rockefeller Foundation; by the Charles S. Robertson Gift from the Banbury Fund (Dr Mayeux); by the W. Garfield Weston Foundation (Dr Rogaeva); by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research; by the Wellcome Trust; by the Medical Research Council; by the National Institutes of Health; by the National Institute of Health Research; by the Ontario Research Fund; and by the Alzheimer Society of Ontario (Dr St George-Hyslop).

Footnotes

Supplemental content at jamaneurology.com

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Author Contributions: Study concept and design: St George-Hyslop, Rogaeva.

Acquisition of data: Ghani, Sato, Moreno, Mayeux, Rogaeva.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Ghani, Lee, Reitz, Rogaeva.

Drafting of the manuscript: Ghani, Lee, Reitz, St George-Hyslop, Rogaeva.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Sato, Lee, Reitz, Moreno, Mayeux, St George-Hyslop.

Statistical analysis: Ghani, Lee, Reitz.

Obtained funding: Ghani, Sato, Moreno, Mayeux, St George-Hyslop, Rogaeva.

Administrative, technical, and material support: Mayeux, Rogaeva.

Study supervision: St George-Hyslop, Rogaeva.

References

- 1.Glenner GG, Wong CW. Alzheimer’s disease: initial report of the purification and characterization of a novel cerebrovascular amyloid protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984;120(3):885–890. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(84)80190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Younkin SG. The role of Aβ42 in Alzheimer’s disease. J Physiol Paris. 1998;92(3–4):289–292. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4257(98)80035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rogaeva E, Kawarai T, George-Hyslop PS. Genetic complexity of Alzheimer’s disease: successes and challenges. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;9(3) suppl:381–387. doi: 10.3233/jad-2006-9s343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harold D, Abraham R, Hollingworth P, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and PICALM associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41(10):1088–1093. doi: 10.1038/ng.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lambert JC, Heath S, Even G, et al. European Alzheimer’s Disease Initiative Investigators. Genome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and CR1 associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41(10):1094–1099. doi: 10.1038/ng.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carrasquillo MM, Belbin O, Hunter TA, et al. Replication of CLU, CR1 and PICALM associations with Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2010;67(8):961–964. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naj AC, Jun G, Beecham GW, et al. Common variants at MS4A4/MS4A6E, CD2AP, CD33 and EPHA1 are associated with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43(5):436–441. doi: 10.1038/ng.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hollingworth P, Harold D, Sims R, et al. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative; CHARGE Consortium; EADI1 Consortium. Common variants at ABCA7, MS4A6A/MS4A4E, EPHA1, CD33 and CD2AP are associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43(5):429–435. doi: 10.1038/ng.803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hazrati LN, Van Cauwenberghe C, Brooks PL, et al. Genetic association of CR1 with Alzheimer’s disease: a tentative disease mechanism. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33(12):2949.e5–2949.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rogaeva E, Meng Y, Lee JH, et al. The neuronal sortilin-related receptor SORL1 is genetically associated with Alzheimer disease. Nat Genet. 2007;39(2):168–177. doi: 10.1038/ng1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guerreiro R, Wojtas A, Bras J, et al. Alzheimer Genetic Analysis Group. TREM2 variants in Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):117–127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Majounie E, Abramzon Y, Renton AE, et al. Repeat expansion in C9ORF72 in Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(3):283–284. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1113592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cacace R, Van Cauwenberghe C, Bettens K, et al. C9orf72 G4C2 repeat expansions in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34(6):1712.e1–1712.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xi Z, Zinman L, Grinberg Y, et al. Investigation of c9orf72 in 4 neurodegenerative disorders. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(12):1583–1590. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2012.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wingo TS, Lah JJ, Levey AI, Cutler DJ. Autosomal recessive causes likely in early-onset Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(1):59–64. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Di Fede G, Catania M, Morbin M, et al. A recessive mutation in the APP gene with dominant-negative effect on amyloidogenesis. Science. 2009;323(5920):1473–1477. doi: 10.1126/science.1168979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takata A, Kato M, Nakamura M, et al. Exome sequencing identifies a novel missense variant in RRM2B associated with autosomal recessive progressive external ophthalmoplegia. Genome Biol. 2011;12(9):R92. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-9-r92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winters KA, Jiang Z, Xu W, et al. Re-assigned diagnosis of D4ST1-deficient Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (adducted thumb-clubfoot syndrome) after initial diagnosis of Marden-Walker syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158A(11):2935–2940. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kearney HM, Kearney JB, Conlin LK. Diagnostic implications of excessive homozygosity detected by SNP-based microarrays: consanguinity, uniparental disomy, and recessive single-gene mutations. Clin Lab Med. 2011;31(4):595–613. ix. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papenhausen P, Schwartz S, Risheg H, et al. UPD detection using homozygosity profiling with a SNP genotyping microarray. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A(4):757–768. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang HC, Chang LC, Liang YJ, Lin CH, Wang PL. A genome-wide homozygosity association study identifies runs of homozygosity associated with rheumatoid arthritis in the human major histocompatibility complex. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e34840. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Casey JP, Magalhaes T, Conroy JM, et al. A novel approach of homozygous haplotype sharing identifies candidate genes in autism spectrum disorder. Hum Genet. 2012;131(4):565–579. doi: 10.1007/s00439-011-1094-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li LH, Ho SF, Chen CH, et al. Long contiguous stretches of homozygosity in the human genome. Hum Mutat. 2006;27(11):1115–1121. doi: 10.1002/humu.20399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gibson J, Morton NE, Collins A. Extended tracts of homozygosity in outbred human populations. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15(5):789–795. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirin M, McQuillan R, Franklin CS, Campbell H, McKeigue PM, Wilson JF. Genomic runs of homozygosity record population history and consanguinity. PLoS One. 2010;5(11):e13996. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Curtis D, Vine AE, Knight J. Study of regions of extended homozygosity provides a powerful method to explore haplotype structure of human populations. Ann Hum Genet. 2008;72(pt 2):261–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2007.00411.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nalls MA, Guerreiro RJ, Simon-Sanchez J, et al. Extended tracts of homozygosity identify novel candidate genes associated with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Neurogenetics. 2009;10(3):183–190. doi: 10.1007/s10048-009-0182-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sims R, Dwyer S, Harold D, et al. No evidence that extended tracts of homozygosity are associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2011;156B(7):764–771. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang S, Haynes C, Barany F, Ott J. Genome-wide autozygosity mapping in human populations. Genet Epidemiol. 2009;33(2):172–180. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kurotaki N, Tasaki S, Mishima H, et al. Identification of novel schizophrenia loci by homozygosity mapping using DNA microarray analysis. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e20589. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sherva R, Baldwin CT, Inzelberg R, et al. Identification of novel candidate genes for Alzheimer’s disease by autozygosity mapping using genome wide SNP data. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;23(2):349–359. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clarimón J, Djaldetti R, Lleó A, et al. Whole genome analysis in a consanguineous family with early onset Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30(12):1986–1991. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee JH, Cheng R, Barral S, et al. Identification of novel loci for Alzheimer disease and replication of CLU, PICALM and BIN1 in Caribbean Hispanic individuals. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(3):320–328. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghani M, Pinto D, Lee JH, et al. Genome-wide survey of large rare copy number variants in Alzheimer’s disease among Caribbean Hispanics. G3 (Bethesda) 2012;2(1):71–78. doi: 10.1534/g3.111.000869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Athan ES, Williamson J, Ciappa A, et al. A founder mutation in presenilin 1 causing early-onset Alzheimer disease in unrelated Caribbean Hispanic families. JAMA. 2001;286(18):2257–2263. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.18.2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tang H, Choudhry S, Mei R, et al. Recent genetic selection in the ancestral admixture of Puerto Ricans. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(3):626–633. doi: 10.1086/520769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Demographics of Puerto Rico. [Accessed May 2013]; http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demographics_of_Puerto_Rico. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dominican people (Dominican Republic) [Accessed May 2013]; http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dominican_people. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tang MX, Cross P, Andrews H, et al. Incidence of AD in African-Americans, Caribbean Hispanics, and Caucasians in northern Manhattan. Neurology. 2001;56(1):49–56. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Howrigan DP, Simonson MA, Keller MC. Detecting autozygosity through runs of homozygosity: a comparison of three autozygosity detection algorithms. BMC Genomics. 2011 Sep 23;12:460. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(2):263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88(1):76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang J, Benyamin B, McEvoy BP, et al. Common SNPs explain a large proportion of the heritability for human height. Nat Genet. 2010;42(7):565–569. doi: 10.1038/ng.608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keller MC, Simonson MA, Ripke S, et al. Schizophrenia Psychiatric Genome-Wide Association Study Consortium. Runs of homozygosity implicate autozygosity as a schizophrenia risk factor. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(4):e1002656. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Inoue M, Chang L, Hwang J, Chiang SH, Saltiel AR. The exocyst complex is required for targeting of Glut4 to the plasma membrane by insulin. Nature. 2003;422(6932):629–633. doi: 10.1038/nature01533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Apodaca G. Opening ahead: early steps in lumen formation revealed. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12(11):1026–1028. doi: 10.1038/ncb1110-1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sans N, Prybylowski K, Petralia RS, et al. NMDA receptor trafficking through an interaction between PDZ proteins and the exocyst complex. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5(6):520–530. doi: 10.1038/ncb990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.De Strooper B, Annaert W. Where Notch and Wnt signaling meet: the presenilin hub. J Cell Biol. 2001;152(4):F17–F20. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.4.f17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raurell I, Codina M, Casagolda D, et al. Gamma-secretase-dependent and -independent effects of presenilin1 on β-catenin·Tcf-4 transcriptional activity. PLoS One. 2008;3(12):e4080. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boo JH, Song H, Kim JE, Kang DE, Mook-Jung I. Accumulation of phosphorylated β-catenin enhances ROS-induced cell death in presenilin-deficient cells. PLoS One. 2009;4(1):e4172. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Georgakopoulos A, Marambaud P, Efthimiopoulos S, et al. Presenilin-1 forms complexes with the cadherin/catenin cell-cell adhesion system and is recruited to intercellular and synaptic contacts. Mol Cell. 1999;4(6):893–902. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80219-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marambaud P, Shioi J, Serban G, et al. A presenilin-1/γ-secretase cleavage releases the E-cadherin intracellular domain and regulates disassembly of adherens junctions. EMBO J. 2002;21(8):1948–1956. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.8.1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Myers A, Holmans P, Marshall H, et al. Susceptibility locus for Alzheimer’s disease on chromosome 10. Science. 2000;290(5500):2304–2305. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5500.2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ertekin-Taner N, Graff-Radford N, Younkin LH, et al. Linkage of plasma Aβ42 to a quantitative locus on chromosome 10 in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease pedigrees. Science. 2000;290(5500):2303–2304. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5500.2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bertram L, Mullin K, Parkinson M, et al. Is α-T catenin (VR22) an Alzheimer’s disease risk gene? J Med Genet. 2007;44(1):e63. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.039263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miyashita A, Arai H, Asada T, et al. Japanese Genetic Study Consortium for Alzheimer’s Disease. Genetic association of CTNNA3 with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease in females. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16(23):2854–2869. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Martin ER, Bronson PG, Li YJ, et al. Interaction between the α-T catenin gene (VR22) and APOE in Alzheimer’s disease. J Med Genet. 2005;42(10):787–792. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.029553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ertekin-Taner N, Ronald J, Asahara H, et al. Fine mapping of the α-T catenin gene to a quantitative trait locus on chromosome 10 in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease pedigrees. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12(23):3133–3143. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reitz C, Conrad C, Roszkowski K, Rogers RS, Mayeux R. Effect of genetic variation in LRRTM3 on risk of Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(7):894–900. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.2463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.D’Souza-Schorey C, Chavrier P. ARF proteins: roles in membrane traffic and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7(5):347–358. doi: 10.1038/nrm1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Klein S, Franco M, Chardin P, Luton F. Role of the Arf6 GDP/GTP cycle and Arf6 GTPase-activating proteins in actin remodeling and intracellular transport. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(18):12352–12361. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601021200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Antunez C, Boada M, Gonzalez-Perez A, et al. The membrane-spanning 4-domains, subfamily A (MS4A) gene cluster contains a common variant associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Genome Med. 2011;3(5):33. doi: 10.1186/gm249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Logue MW, Schu M, Vardarajan BN, et al. Multi-institutional Research on Alzheimer Genetic Epidemiology (MIRAGE) Study Group. A comprehensive genetic association study of Alzheimer disease in African Americans. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(12):1569–1579. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kamboh MI, Barmada MM, Demirci FY, et al. Genome-wide association analysis of age-at-onset in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(12):1340–1346. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Han MR, Schellenberg GD, Wang LS. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Genome-wide association reveals genetic effects on human Aβ42 and τ protein levels in cerebrospinal fluids: a case control study. BMC Neurol. 2010 Oct;10:90. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-10-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]