Palliative care suffers from an identity problem. Seventy percent of Americans describe themselves as “not at all knowledgeable” about palliative care, and most health care professionals believe it is synonymous with end-of-life care.1 This perception is not far from current medical practice, because specialty palliative care — administered by clinicians with expertise in palliative medicine — is predominantly offered through hospice care or inpatient consultation only after life-prolonging treatment has failed. Limiting specialty palliative care to those enrolled in hospice or admitted to the hospital ignores the majority of patients facing a serious illness, such as advanced cancer, who have physical and psychological symptoms throughout their disease. To ensure that patients receive the best care throughout their disease trajectory, we believe that palliative care should be initiated alongside standard medical care for patients with serious illnesses.

For palliative care to be used appropriately, clinicians, patients, and the general public must understand the fundamental differences between palliative care and hospice care. The Medicare hospice benefit provides hospice care exclusively to patients who are willing to forgo curative treatments and who have a physician-estimated life expectancy of 6 months or less.2 In contrast, palliative care is not limited by a physician’s estimate of life expectancy or a patient’s preference for curative medication or procedures. According to a field-tested definition developed by the Center to Advance Palliative Care and the American Cancer Society, “Palliative care is appropriate at any age and at any stage in a serious illness, and can be provided together with curative treatment.”1 Several clinical trials have shown benefits of early specialty palliative care in patients with advanced cancer.3 The effect of early specialty palliative care in other patient populations is less well studied, but there are data suggesting a beneficial role in patients with multiple sclerosis4 and congestive heart failure.5,6

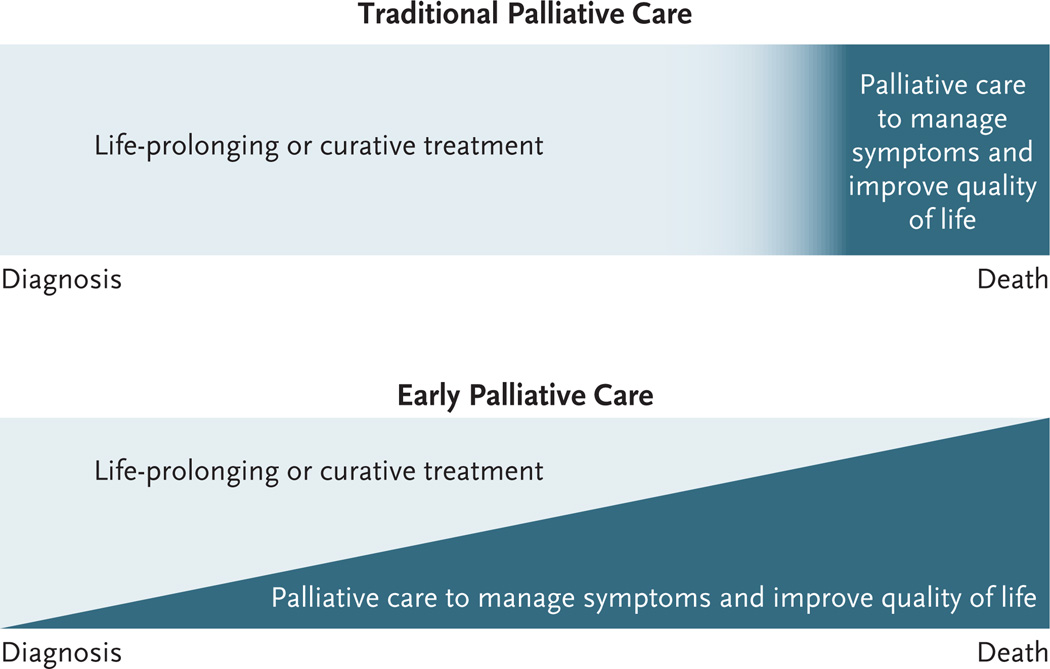

Although there are salient differences between hospice care and palliative care, notably the limitations on prognosis and use of curative therapies with hospice care, most palliative care is currently provided at the end of life. This perceived association between palliative care and end-of-life care has led to a marginalization of palliative care.1 Debates over “death panels,” physician-assisted suicide, and reimbursement for advance care planning have made policymakers reluctant to devote resources to initiatives perceived to be associated with “death and dying.” For example, National Institutes of Health allocations for research focused on palliative care remain far behind funding for procedure-oriented specialties.7 The practice and policy behind palliative care must be considered independently from end-of-life care. Palliative care should no longer be reserved exclusively for those who have exhausted options for life-prolonging therapies (Fig. 1).8

Figure 1. Traditional versus Early Palliative Care.

In the traditional care model, palliative care is instituted only after life-prolonging or curative treatment is no longer administered. In the integrated model, both palliative care and life-prolonging care are provided throughout the course of disease. Adapted from the Institute of Medicine.8

We present three separate cases — clinical, economic, and political — focused predominantly on data in patients with advanced cancer to show the value of earlier specialty palliative care. We then use these data to propose initial priorities for clinicians and policymakers to achieve early integration of palliative care across all populations with serious illness.

THE CLINICAL CASE

Several randomized studies involving patients with advanced cancer show that integrating specialty palliative care with standard oncology care leads to significant improvements in quality of life and care and possibly survival (Table 1).6,9–12 Patients with advanced cancer who receive palliative care consultations early in the course of their disease report better symptom control than those not receiving consultations.11,12 Several prospective trials have also shown that early palliative care improves patients’ quality of life.10–12 For example, patients with metastatic lung cancer who receive outpatient palliative care from the time of diagnosis and throughout the course of their illness report better quality of life and lower rates of depression than do controls.11,13

Table 1.

Randomized Trials of Early Specialty Palliative Care Interventions in Patients with Cancer.

| Trial | Population | Intervention | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brumley et al.6 | 298 homebound patients with a prognosis of <1 yr to live and a recent hospital or ED visit; included 138 patients with cancer | Usual care + in-home multidisciplinary PC (frequency of visits based on individual needs of patients) vs. usual care | Patients assigned to PC had lower rates of ED visits (P = 0.01) and hospital admissions (P<0.001) and lower medical costs (difference in mean cost, $7,552; P = 0.004) and were more likely to die at home (P<0.001). There was no significant between-group difference in hospice enrollment. |

| Gade et al.9 | 517 patients with ≥1 life-limiting diagnosis and their physician “would not be surprised” if the patient died ≤1 yr; included 159 patients with cancer | Usual care + inpatient multidisciplinary PC consultation vs. usual care | Patients receiving PC reported more satisfaction with care (P<0.001), had fewer ICU stays on hospital readmission (P = 0.04), and had a 6-mo net cost savings of $4,855 per patient (P = 0.001). There were no significant between-group differences in hospice use, completion of advanced directives, symptoms and quality of life, or survival. |

| Bakitas et al.10 | 322 patients with a life-limiting cancer and a prognosis of approximately 1 yr to live | Usual care + phone-based PC administered by advanced-practice nurse in 4 structured sessions and at least monthly follow-up vs. usual care | Patients assigned to PC reported better quality of life (P = 0.02) and mood (P = 0.02). There were no significant between-group differences in symptom burden or intensity of service (hospital and ICU days or number of ED visits). |

| Temel et al.11 | 151 patients within 8 wk after diagnosis of metastatic lung cancer | Usual care + outpatient PC (provided by physician or advanced-practice nurse) at least monthly and PC consultation if patient hospitalized vs. usual care | Patients receiving early PC had better quality of life (P = 0.03), lower rates of depression (P = 0.01), less aggressive end-of-life care (P = 0.05), and longer median survival (P = 0.02). |

| Zimmermann et al.12 | 442 patients with metastatic cancer and a physician-provided prognosis of 6 mo to 2 yr to live | Usual care + early ambulatory PC at least monthly vs. usual care with routine PC | Patients receiving early PC reported greater satisfaction with care (P<0.001), better quality of life (P = 0.008), and less severe symptoms (P = 0.05) at 4 mo. |

ED denotes emergency department, ICU intensive care unit, and PC palliative care.

Initiating palliative care upon diagnosis of advanced cancer also improves patients’ understanding of their prognosis.14 Patients with serious illness often feel that their doctors do not provide all available information about their illness and treatment options.1 These information gaps can lead patients to misunderstand their treatment goals. For example, recent studies show that the majority of patients with metastatic cancer incorrectly report that their cancer can be cured with chemotherapy or radiation.15,16 Palliative care clinicians can remedy this situation by helping patients develop a more accurate assessment of their prognosis.14 Improved prognostic understanding may explain why patients with advanced cancer who receive early palliative care consultations are less likely to receive chemotherapy near the end of life than are controls.14,17

THE ECONOMIC CASE

Cost savings are never the primary intent of providing palliative care to patients with serious illnesses, for whom ensuring the best quality of life and care is paramount. Nevertheless, it is necessary to consider the financial consequences of serious illness, because 10% of the sickest Medicare beneficiaries account for nearly 60% of total program spending.18 The growing cost of hospital care is the main driver of the spending growth observed for seriously ill patients.19 Fortunately, the quality improvements offered by early specialty palliative care may also lead to lower total spending on inpatient health care.20 Hospitals with specialty palliative care services have decreased lengths of stay, admissions to the intensive care unit, and pharmacy and laboratory expenses.9,21–23 One study estimated that inpatient palliative care consultations are associated with more than $2,500 in net cost savings per patient admission.23

Similarly, outpatient palliative care services have been estimated to reduce overall treatment costs for seriously ill patients by up to 33% per patient.6 Early outpatient palliative care achieves these savings by decreasing the need for acute care services, leading to fewer hospital admissions and emergency department visits.11,24 The site of death may be another mediator of savings, because patients receiving early specialized palliative care are more likely to forgo costly inpatient care at the end of life than are other patients.6 Outpatient palliative care may thus lower health care spending by reducing patients’ need for hospital and acute care. The goal of early palliative care, both in and out of the hospital, is to provide a better quality of life; cost savings through reduced resource use are an epiphenomenon of this better care.

THE POLITICAL CASE

These data show that earlier specialized palliative care services meet the “triple aim” of better health, improved care, and lower cost.25 Despite such positive outcomes, legislative efforts to support the delivery of palliative care have lagged behind clinical interest. High-profile and controversial legal cases, such as those of Terry Schiavo and Dr. Jack Kevorkian, have heightened public sensitivity about medical care perceived to hasten death. Similarly, the inflammatory language surrounding “death panels” that surfaced during the Affordable Care Act debate left legislators wary of addressing policies perceived as promoting end-of-life care.

However, policy momentum is now building, bolstered by evidence establishing the quality-of-life benefit of palliative care for patients with advanced cancer. Federal legislative proposals, including the Patient Centered Quality Care for Life Act and the Palliative Care and Hospice Education and Training Act, have built bipartisan support for federal and state legislation that addresses palliative care research, the palliative care workforce, and barriers to accessing care. These efforts foreshadow more legislative initiatives that prioritize quality of life and survivorship.

Although legislation is a key step toward changing policy regarding palliative care, the main impediment remains a matter of messaging. Reframing the policy and professional discussion around palliative care as a means to improve quality of life without decreasing survival is essential to make this advocacy agenda more politically tenable. More than 90% of Americans react favorably to a definition of palliative care that emphasizes it as “an extra layer of support” that is appropriate at “any stage in a serious illness.”1 Advocacy groups, practitioners, and researchers should use this language consistently to advance this effort to integrate palliative care earlier in illness.

SOLUTIONS TO MAKE THE TRANSITION

Although data to date support the use of early specialty palliative care for patients with advanced cancer, the clinical and economic benefits are likely to apply to other patient populations. Randomized trials of early palliative care have shown benefit for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, and multiple sclerosis.4,6,9 Further investigation of the role of early specialty palliative care in patients with other serious illnesses is clearly warranted. In addition, all clinicians caring for patients with serious illness, not just pal- liative care specialists, must be capable of practicing “primary palliative care,” which includes managing illness- and treatment-related symptoms to improve quality of life and assessing treatment preferences and prognostic understanding.26

INCENTIVE CHANGES

To reinforce the practice of early palliative care for all serious illnesses, hospitals, insurance providers, and the government would need to provide practice and payment incentives for clinicians. Medicare reimbursement for clinicians to counsel patients about their goals and options for care throughout their illness is necessary to encourage and reinforce early palliative care. Unfortunately, congressional efforts to reimburse for this service have been unsuccessful. Hospital administrators have also identified several barriers to implementing consultative specialty palliative care teams, including limited institutional budgets, poor reimbursement, and few trained staff.27 Although public awareness of the clinical benefits of palliative care may itself drive hospital- level integration, increased reimbursement would most strongly convince hospitals and physicians to integrate primary and specialty palliative care into routine practice.

More broadly, reimbursement structures should encourage coordinated medical care that aligns treatments with patients’ goals. Health care systems that provide structured palliative care services in coordination with disease-centered treatment have enjoyed tremendous success. The Aetna Compassionate Care Program of early nurse-managed palliative care and advanced care planning alongside usual care has decreased hospital lengths of stay and admissions while decreasing costs at the end of life by 22%.28,29 The success of such initiatives should convince Medicare and commercial insurers to reimburse for palliative care services regardless of prognosis and treatment goals.

EDUCATIONAL REFORM

Dedicated clinical exposure to seriously ill patients, in combination with structured didactic teaching, improves medical students’ attitudes toward palliative care.30 A study based on survey data from 1998 through 2006 from the Association of American Medical Colleges showed greater student exposure to palliative care training over the past decade.31 However, current curricula generally focus exclusively on care at the end of life. Instead, we believe that health professional schools should establish content areas in palliative care during the preclinical and clinical years and train students in managing symptoms, providing psychosocial support, and discussing prognosis and treatment preferences for all seriously ill patients. Furthermore, lawmakers should adjust the current cap on training positions in graduate medical education and increase funding for fellowship programs in palliative care to expand the palliative care workforce.

EXPANDING HOSPITAL-BASED PALLIATIVE CARE TEAMS

Integrated palliative care requires patients to have access to palliative care services in the inpatient and outpatient settings, across both the acute and chronic phases of disease. Although hospital-based palliative care teams improve quality of care while reducing inpatient costs, their prevalence varies considerably according to geographic region and is quite low in some locations. Among adult-care hospitals with 50 or more beds, the statewide prevalence of inpatient palliative care teams ranges from 20 to 100% across the United States.32 Small, for-profit, and public hospitals are far less likely to have palliative care teams than large and nonprofit institutions.22 Hospital leaders should ensure that all hospitals have access to integrated palliative care services within the next decade. Data suggest that this trend has already begun: more than half of administrators at major cancer centers plan to increase palliative care professional recruitment in the short term.27 The American Hospital Association and Center to Advance Palliative Care have released guidelines advocating the use of specialist palliative care services for the management of complex conditions in inpatient settings.33 These efforts, coupled with strong external incentives such as Medicare Conditions of Participation and Joint Commission accreditation requirements, will reinforce hospital penetration of palliative care.

CONCLUSIONS

Early provision of specialty palliative care improves quality of life, lowers spending, and helps clarify treatment preferences and goals of care for patients with advanced cancer. However, widespread integration of palliative care with standard medical treatment remains unrealized, and more evidence is needed to show the potential gains of early palliative care in other populations. This will require improved public and professional awareness of the benefits of palliative care and coordinated action from advocacy groups, health professionals, educators, and policymakers. Patients who access earlier specialty palliative care have better clinical outcomes at potentially lower costs — a compelling message for providers, policymakers, and the general public.

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.2011 Public opinion research on palliative care: a report based on research by public opinion strategies. New York: Center to Advance Palliative Care; 2011. ( http://www.capc.org/tools-for-palliative-care-programs/marketing/public-opinion-research/2011-public-opinion-research-on-palliative-care.pdf). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medicare hospice benefits. Baltimore: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 2013 ( http://www.medicare.gov/publications/pubs/pdf/02154.pdf).

- 3.Greer JA, Jackson VA, Meier DE, Temel JS. Early integration of palliative care services with standard oncology care for patients with advanced cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013 Jul 15; doi: 10.3322/caac.21192. (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higginson IJ, Costantini M, Silber E, Burman R, Edmonds P. Evaluation of a new model of short-term palliative care for people severely affected with multiple sclerosis: a randomised fast-track trial to test timing of referral and how long the effect is maintained. Postgrad Med J. 2011;87:769–775. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2011-130290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hauptman PJ, Havranek EP. Integrating palliative care into heart failure care. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:374–378. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.4.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brumley R, Enguidanos S, Jamison P, et al. Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: results of a randomized trial of in-home palliative care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:993–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Overall appropriations. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, Office of Budget; 2013. ( http://officeofbudget.od.nih.gov/pdfs/FY13/Vol%201%20Tab%202%20-%20Overall%20Appropriations.pdf). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Improving palliative care for cancer: summary and recommendations. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2003. ( http://iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2003/Improving-Palliative-Care-for-Cancer-Summary-and-Recommendations/PallativeCare 8pager.pdf). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gade G, Venohr I, Conner D, et al. Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: a randomized control trial. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:180–190. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:741–749. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zimmermann C, Swami N, Rodin G, et al. Cluster-randomized trial of early palliative care for patients with metastatic cancer. Presented at the 2012 American Society for Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting, Chicago. 2012 Jun 1–5; abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pirl WF, Greer JA, Traeger L, et al. Depression and survival in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: effects of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1310–1315. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.3166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S, et al. Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a randomized study of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2319–2326. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.4459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, et al. Patients’ expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1616–1625. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1204410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen AB, Cronin A, Weeks JC, et al. Expectations about the effectiveness of radiation therapy among patients with incurable lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2730–2735. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.5748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greer JA, Pirl WF, Jackson VA, et al. Effect of early palliative care on chemotherapy use and end-of-life care in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:394–400. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.7996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Medicare spending and financing fact sheet. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2012. ( http://www.kff.org/medicare/upload/7305-07.pdf). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meier DE, Isaacs SL, Hughes R, editors. Palliative care: transforming the care of serious illness. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meier DE. Increased access to palliative care and hospice services: opportunities to improve value in health care. Milbank Q. 2011;89:343–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00632.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ciemins EL, Blum L, Nunley M, Lasher A, Newman JM. The economic and clinical impact of an inpatient palliative care consultation service: a multifaceted approach. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:1347–1355. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldsmith B, Dietrich J, Du Q, Morrison RS. Variability in access to hospital palliative care in the United States. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:1094–1102. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morrison RS, Penrod JD, Cassel JB, et al. Cost savings associated with US hospital palliative care consultation programs. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1783–1790. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.16.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brumley RD, Enguidanos S, Cherin DA. Effectiveness of a home-based palliative care program for end-of-life. J Palliat Med. 2003;6:715–724. doi: 10.1089/109662103322515220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The IHI Triple Aim initiative. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2013. ( http://www.ihi.org/offerings/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care — creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1173–1175. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1215620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hui D, Elsayem A, De la Cruz M, et al. Availability and integration of palliative care at US cancer centers. JAMA. 2010;303:1054–1061. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spettell CM, Rawlins WS, Krakauer R, et al. A comprehensive case management program to improve palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:827–832. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krakauer R, Spettell CM, Reisman L, Wade MJ. Opportunities to improve the quality of care for advanced illness. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:1357–1359. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morrison LJ, Thompson BM, Gill AC. A required third-year medical student palliative care curriculum impacts knowledge and attitudes. J Palliat Med. 2012;15:784–789. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sulmasy DP, Cimino JE, He MK, Frishman WHUS. U.S. medical students’ perceptions of the adequacy of their schools’ curricular attention to care at the end of life: 1998–2006. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:707–716. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.A state-by-state report card on access to palliative care in our nation’s hospitals. New York: Center to Advance Palliative Care; 2011. ( http://www.capc.org/reportcard). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palliative care services: solutions for better patient care and today’s health care delivery challenges. Chicago: American Hospital Association; 2012. ( http://www.hpoe.org). [Google Scholar]