Abstract

School-based interventions for young people with emotional/mental health problems are often provided by external practitioners and their relationship with host schools is a key influence on implementation. Poor integration within school systems, schools' tendency to define interventions around pupils' behaviour and teachers' control over access, may undermine therapeutic relationships. This study examines how one school-based intervention—Bounceback—addressed these challenges. Methods comprised interviews with programme staff, school staff and service users. Bounceback sought to develop therapeutic relationships through creating a safe, welcoming place and maximising pupils' choice about how they engaged with it. To ensure Bounceback was delivered as intended, staff developed five conditions which schools were asked to meet: adhering to referral criteria, ensuring that attendance was voluntary, appropriate completion of referral forms, mechanisms for contacting pupils and private accommodation to maintain confidentiality. Pupils reported high levels of acceptability and described relationships of trust with Bounceback staff. Although pupils had choice about most aspects of Bounceback, teachers controlled access to it, partly in order to manage demand. The study highlights the need for external agencies to communicate their aims and needs clearly to schools and the importance of peripatetic practitioners being well integrated within their parent organisations.

Keywords: adolescent health, emotional health, evaluation, mental health, school

Introduction

The high prevalence of emotional/mental health problems amongst young people is a global health issue (Rones & Hoagwood, 2000; Blum & Nelson-Mmari, 2004; Patel et al., 2007), and recent decades have witnessed the proliferation of prevention/treatment interventions (Adelman & Taylor, 1998; Durlak & Wells, 1998; Weisz et al., 2004). However, many young people do not access support (Rones & Hoagwood, 2000; Baruch, 2001; Waters et al., 2001; Langley et al., 2010; Pinto-Foltz et al., 2011), and significant barriers to utilisation exist, including inappropriate delivery settings (Patel et al., 2007), uncoordinated services (e.g. transitions from child to adult services) (Davis, 2003), help-seeking stigma (Browne et al., 2004; Pinto-Foltz et al., 2011) and lack of knowledge about services (Shandley et al., 2010). Therapeutic relationships also influence young people's use of services, including trust, confidentiality and being listened to (Le Surf & Lynch, 1999; Fox & Butler, 2007; Kidger et al., 2009; Shandley et al., 2010).

Schools are expected to function as health-promoting institutions through cultivating emotionally supportive environments, delivering health-related curricula and providing targeted support to individuals with emotional/mental health problems (Wyn et al., 2000; Bond et al., 2004; Stewart et al., 2004; Allegrante, 2008; Kimber et al., 2008; Kidger et al., 2009; Spratt et al., 2010). Schools facilitate contact with large numbers of young people (Dickinson et al., 2003; Spence & Shortt, 2007; Kidger et al., 2009), both directly and via staff who engage with pupils over extended periods. Locating services in schools can normalise and reduce the stigma of support seeking (Baruch, 2001), coordinate multiple services (Weist et al., 2001) and facilitate access (Baruch, 2001).

Whilst most schools have pastoral teams to address the needs of pupils with emotional/mental health problems, external practitioners such as counsellors, psychotherapists, youth workers and nurses play an important role in providing specialist support (Baruch, 2001; Kay et al., 2006; Fox & Butler, 2007; Weist et al., 2012). However, a number of important gaps remain in the literature. In the case of school counselling, for instance, Cooper (2009) notes that despite the growth in its provision, ‘little empirical evidence is available on the kinds of clients that attend these services, their outcomes or how they experience the counselling’. (p. 137). Similarly, Fox and Butler (2009) suggest that ‘very few studies have focused on school-based counselling, and only one study, to our knowledge, has been carried out in the United Kingdom’ (p. 96). The role of such external agencies also raises questions about how they are integrated into schools (Adelman & Taylor, 1998; Patton et al., 2000; Baruch, 2001; Ringeisen et al., 2003; Kay et al., 2006; Spratt et al., 2006; Spratt et al., 2010). The increased presence of health-promoting activities and agencies in schools makes these questions particularly pertinent, but as long ago as the 1970s Hamblin's (1974) exploration of The Teacher and Counselling argued that school counsellors needed to be integrated within school systems and to understand how schools' expectations had the potential to constrain or facilitate counselling work. For Hamblin, integration was important, because it helped to ensure schools understood that counselling was for any pupil (not for particular groups or problems) and should not be used as a form of discipline (Hamblin, 1974). More recently, authors such as Spratt et al. (2006) and Adelman and Taylor (1998) have suggested that there is a tendency for schools to frame emotional support in terms of individual pupils' behaviour and their inability to conform to educational norms, rather than how such norms and school environments affect pupils' ability to learn. This can result in external support services being ‘bolted on’ to the periphery of existing school systems, with little opportunity to bring about change in approaches to emotional health issues (Adelman & Taylor, 1998; Spratt et al., 2006). External agencies that are not well integrated within schools may find it difficult to communicate the aims of their services and what they need to deliver them, such as appropriate accommodation to maintain confidentiality. Spratt et al. (2010) argue that whilst health practitioners often promote young people's agency in deciding if and how to use services, schools may control access by managing referral processes. If teachers retain responsibility for determining who needs support—and frame this around unacceptable behaviour and individual pupils' non-conformity with school norms—it may restrict access and create negative perceptions amongst pupils about who services are for, potentially undermining therapeutic relationships and trust (Spratt et al., 2010).

Relationships between practitioners and the schools in which they work are therefore critical barriers to, and facilitators of, effective implementation of mental health services (Forman et al., 2009; Langley et al., 2010; Weist et al., 2012). Langley et al. (2010) suggest that one important direction for future studies is to move beyond identifying key barriers to implementation and ‘to shift the focus onto what sets of conditions make it more or less likely that barriers can be surmounted’ (p. 112). Accordingly, in this study, we seek to contribute to current research by examining how one school-based emotional health service—Bounceback—addressed key implementation challenges. The study considers, firstly, the ways in which Bounceback sought to develop elements of the therapeutic relationship, which have previously been identified as important, including trust, listening and maximising choice over how pupils used the service. Secondly, we examine the challenges Bounceback encountered in relation to communicating with school staff about the service's aims and eligibility criteria, referral processes and provision of suitable accommodation; and explore how practitioners articulated a set of minimum requirements to enable the service to be delivered with fidelity. The third section of the study examines the receipt and acceptability of the service.

Bounceback was delivered by a children's charity—Barnardo's—and provided one-to-one sessions to pupils in years 10–11 (aged 14–16) who were experiencing stressful situations. It aimed to create a ‘safe place’ where young people could determine the focus of the sessions, talk through issues which concerned them and find solutions. Programme staff suggested that Bounceback was distinctive from counselling, in terms of its informality, the degree of control which pupils could exercise over the focus of sessions and the fact that it incorporated practical help and advice (e.g. on employment), as well as emotional support. This is not to say, however, that there were not significant overlaps or similarities between Bounceback's approach and that adopted by counselling practitioners. In exploring how Bounceback interacted with school systems, we highlight the broad relevance of our findings for a range of health practitioners who provide school-based support for young people.

The service operated in three schools in south Wales, United Kingdom, which served economically disadvantaged city populations and taught large percentages of pupils from ethnic minority backgrounds. Two had 800–900 pupils and the other nearly 1600. All had relatively large proportions of pupils below average academic ability (based on Estyn school inspection reports: to maintain schools' anonymity these are not referenced). Bounceback sessions lasted 30 minutes and were delivered during lesson time. Staff would see 5–6 young people each week in each school. Timing of appointments was flexible to accommodate those who needed more/less time, arrived late or without an appointment. Day trips/fun days were organised for service users, and Bounceback also provided awareness-raising workshops for groups of pupils/staff on mental/emotional health issues such as self-harm.

Methods

The research sought to establish Bounceback's aims/theory, feasibility and acceptability and had four aims: to explore the views of young people who had used the service in terms of acceptability and perceived outcomes; to examine Bounceback's potential to prevent emotional/mental health issues in young people from becoming more serious; to examine the relationship between Bounceback and schools in which it operated and to identify young people's support needs during the transition from school to independent adulthood. All data collection and analysis were conducted by university-based researchers who had no involvement in the delivery of Bounceback. Interviews were conducted with all five members of Bounceback staff; four staff from the three schools where Bounceback operated and seven service users. These were recorded and transcribed (with participants' permission). At each school, the senior teacher responsible for co-operation with Bounceback was interviewed, and in one school, a pastoral care assistant participated in the interview. Tables 1 and 2 provide details of school-based participants. Bounceback staff approached service users/ex-users to ask whether they were willing for the researchers to contact them (it was not possible for us to contact service users directly). They were asked for a cross-section from all schools, a balance of males/females and also young people who no longer used the service. Twelve young people allowed their contact details to be shared (Table 3) and contact was established with nine, of whom seven took part. Participants, and parents of Bounceback users, gave written consent. Interviews with young people explored whether Bounceback had helped them, if there were aspects of the service that could be changed, and the availability of other support in the school setting (interview guides are available from the corresponding author). Ethical approval for the study was given by a university ethics committee.

Table 1.

Details of school-based interview participants

| Interview participants | Schools |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | S2 | S3 | |

| Teachers | School staff 1 School staff 2 (joint interview) |

School staff 3 | School staff 4 |

| Bounceback users | YP3 (female, current user) YP7 (male, ex user) |

YP5 (male, current user) YP6 (male, current user) |

YP1 (male, current user) YP2 (female, current user) YP4 (female, ex user) |

Table 2.

Roles of school staff interviewees

| Job title | Job description |

|---|---|

| Assistant head teacher | Designated officer for child protection; responsible for implementation of SEAL strategy throughout the school; manager of mentoring scheme |

| Emotional support coach | Providing one-to-one support for pupils; liaison with outside agencies working at the school |

| Head of key stage 3 | Teaching duties with additional responsibility for developing the role of outside agencies within the school |

| Head of school, pupil conduct | Management responsibility for teaching staff; managing and teaching ‘alternative curriculum’ for less academically able pupils |

Table 3.

Characteristics of young people who allowed their contact details to be shared with the researchers (service users and ex-service users)

| Schools |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| Current users | Ex users | Current users | Ex users | Current users | Ex users | |

| Females | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Males | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

A coding framework (Table 4) was developed based on interview schedule questions. Two interviews were coded by one researcher and reviewed by a second, leading to adjustments to the framework. All transcripts were then coded using Atlas.ti 6.1.2. Themes were explored in relation to differences in participants' roles in providing, using or hosting Bounceback.

Table 4.

Analytical framework

| Themes | Subsidiary themes | Codes |

|---|---|---|

| The Bounceback service | Service background; service organisation future plans; aims | |

| Challenges in organisation of service delivery | Service organisation; challenges; School/Bounceback relationship | |

| Referral process | Referral process; targeting; inappropriate referrals | |

| Facilities provided | Facilities; facilitating attendance | |

| Relationship with schools | Fitting in with school routines | School/Bounceback relationship; other support at school; school priorities; school rationale; snags; Service organisation |

| Communication | School/Bounceback relationship; service organisation; snags | |

| Barnardo's organisational background | Caterpillar; support for staff | |

| Confidentiality | Confidentiality; stigma | |

| Advertising | Advertising | |

| Demand for | Demand | |

| Bounceback | Before year 10 | Before year 10 |

| After year 11 | After year 11 | |

| Caterpillar | Caterpillar | |

| Acceptability | Demand | Opinions; long term service |

| Best/most important | Best thing; most important; punctuality; reliability | |

| Areas for improvement | Areas for improvement | |

| How Bounceback works | Activities and materials used | How Bounceback works Activities/materials |

| Benefits of Bounceback | Pupils Schools |

Outcomes; examples School priorities; personal background; school rationale |

| Key implications for practice and research | Future plans |

Findings

Organisation of service delivery

Approximately 50 people had used Bounceback during the year preceding the evaluation. They were dealing with a range of difficulties, including abuse, homelessness, parental illness and bereavement. Bounceback was a free service, but schools provided accommodation and managed referrals (including information about reasons for referral) and sought parental consent for pupils' attendance. A member of pastoral support staff in each school liaised with Bounceback, managed by a senior teacher. The main referral route was teachers noticing something amiss with a pupil and informing the head of year, who notified the senior teacher responsible for pastoral care. The senior teacher decided what kind of support was appropriate. School staff completed a form stating reasons for referral that the young person knew why they were being referred, and that they agreed to see Bounceback. Overall, Bounceback staff felt that referrals were appropriate and that teachers were good at identifying underlying problems like low self-esteem affecting pupils who were outwardly confident/doing well academically. Young people who did not agree to be referred were told that they could come back at any time if they changed their mind.

Pastoral teachers in two schools did not want to advertise Bounceback to pupils because it would be more difficult to preserve confidentiality (school staff 1, school staff 4); there was insufficient capacity to absorb self-referrals in addition to staff referrals (school staff 4); and enough people were already aware of Bounceback (school staff 1). In the third school (S2), Bounceback had been mentioned in a community newsletter featuring services provided at school and the pastoral teacher had spoken to Year 10/11 pupils in their assembly about Bounceback and other services (school staff 3). Bounceback had also run a stall at parents' evening (school staff 3). On the whole, Bounceback staff favoured raising awareness of the service through personal contact with groups of teachers/pupils in years 10/11 or presenting theme-based assemblies, rather than advertising through posters/newsletters (BB Staff 5).

Bounceback staff described how they supported each other day-to-day by talking things over and contributing to planning support for young people. The Bounceback manager had an open door policy, and staff working on other projects were also available informally to listen and provide support (BB Staff 1–5). Team meetings and managerial supervision provided a more formal framework for staff to talk through issues (BB Staff 3, BB Staff 4, BB Staff 5). Bounceback was one of a number of linked services within Barnardo's Caterpillar project, including schools-based counselling, and individual and group support for young people with mental health issues or who were in crisis, and this appeared to influence the quality of support it was able to offer through ease of referral (BB Staff 1) and its capacity to support young people during school holidays (BB Staff 3, 4, YP2) and after leaving school (school staff 4). Caterpillar involved young people in running the service and they had open access to the manager to discuss any issues (BB Staff 3). Caterpillar focused on providing a safe, happy environment for young people, and there was no compulsion for them to talk about their problems. In turn, Caterpillar shared accommodation with other Barnardo's services for vulnerable young people (to whom Bounceback users could be referred) (BB Staff 4).

Working with young people

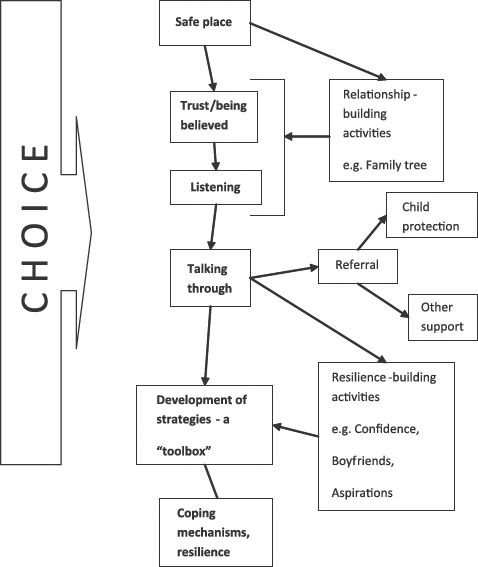

Interviews with Bounceback staff generated a picture of how they thought the service achieved its aims. A logic model was produced and shared with staff, who agreed that it was an accurate representation. The model (Figure 1) shows how key processes described by the staff (in italic text below) might form a causal pathway leading to young people becoming more resilient. Staff emphasised that choice and creation of a safe place were foundations of the communication through which they provided support and that within this environment young people began to trust them and talk about their worries. The quality of listening then became a key feature of the helping process, after which staff would help young people talk through their problems and ways of dealing with them.

Figure 1.

How Bounceback is intended to work

Interviews with Bounceback staff indicated that choice was an ongoing process, rather than single occasions when young people were asked to make decisions. They had a choice about whether to accept referral to Bounceback, and whether they wished to keep subsequent appointments (BB Staff 3). Staff described giving young people the maximum possible control over who had access to information about issues discussed, and asked for consent to make a record of what was said during appointments. No information was shared outside the team, but at the first appointment, staff explained confidentiality/child protection procedures.

Bounceback staff estimated that six or seven young people had decided not to continue after attending one or two Bounceback sessions, with most attrition occurring during the early days of service delivery, linked to unsuitable accommodation and inappropriate referrals for classroom misbehaviour. They described how young people could talk to Bounceback staff or not during appointments, and if they did it could be about anything they wished. They had a choice about whether they wanted to do the activities that were suggested or if they wanted to be referred to other agencies. At the end of term, they could choose whether to continue with Bounceback during school holidays and, at the end of year 11, whether to finish with the service or continue into year 12. Those who finished had the option of going back if they needed to.

Passes given to Bounceback users who needed to be released from lessons stated that they had an ‘appointment’ or ‘interview’. At one school, form teachers were told if pupils were attending Bounceback and in another a list of pupils needing to be excused from lessons was posted in the staffroom, but without details of where they were going. Interviews with Bounceback staff indicated that this was done so that Bounceback users could choose whether they wanted to tell anyone else they were attending, or discuss their problems with them. Their aim was to create a safe, comfortable and informal environment in which young people felt relaxed and cared for (BB Staff 1, 4, 5).

Bounceback staff described how they gave young people as long as they needed to get to know the staff, to trust them and to start to talk, sometimes offering activity worksheets to help this process. Whilst focusing on worksheets, young people had the chance to chat naturally, rather than feeling the pressure of an expectation that they would engage in a conversation. Eventually, a relationship of trust could be formed. Staff sought to demonstrate trustworthiness and empathy through focused attention to what young people said, and by listening without interruption. They believed that time spent talking about general topics was important because it was the quality of the listening environment, as much as problem-specific help, which mattered.

Staff supported young people by talking through issues and prompting them to reflect on their experience and explore alternative ways of dealing with situations. Equality in the relationship was seen as a crucial influence on the acceptability of such guidance. For young people who needed more support, staff would explore options with each other and research topics on the internet (BB Staff 5). As a minimum, the service aimed to give young people leaving Bounceback a ‘toolbox’ of skills and strategies, and a list of contact numbers of agencies that could help them.

Working with schools

Bounceback staff described how during the early stages of programme delivery, conditions in schools had shown potential to undermine its work. Over time, they identified five conditions that needed to be specified in order for the service to run as intended. Firstly, the schools needed to understand and follow referral criteria. Teachers should refer young people with emotional difficulties/mental health issues, which had the potential to cause a crisis or have a negative effect on emotional well-being. It was not acceptable to refer young people because they disrupted lessons by expressing anger or showing off. Secondly, attendance was voluntary and although teachers may have thought it was in pupils' best interests to use Bounceback, they should not put pressure on them to do so. Thirdly, referral forms needed to be passed to Bounceback before the first appointment since lack of information about a person's circumstances could lead to distress and loss of trust. Fourthly, mechanisms were needed for contacting pupils who were due to attend Bounceback. The final issue concerned accommodation—the same room should be available every week so that young people knew where to go. It should not be used as a route into other rooms. There should be no window in the door and other windows should not be overlooked by public areas.

There was a tendency in all the schools for communication to be driven mainly by Bounceback staff and to be restricted to a few contacts within the school. Teachers were unable to devote much time to planning or monitoring how the service operated. They responded well to requests from Bounceback staff but contacting them was often difficult because they had other commitments. Communication became easier when support workers were allocated as Bounceback contacts in each school, with a remit to help organise sessions and pass through referrals (BB Staff 1, 2). Bounceback staff sought regular meetings to discuss school staff's views on the service, facilities provided by the school and referrals and important information affecting young people's welfare. In one school, meetings were organised every half term, but in another, Bounceback staff were able to arrange only two or three meetings a year, and only with staff assigned as key contacts. Many teachers were supportive of the service (YP1, BB Staff 3). However, Bounceback staff felt that communication more generally with teachers would help avoid situations where some were reluctant for young people to miss class-work to attend Bounceback or did not believe that they had a valid reason to leave the class. Pastoral care teams had introduced passes to make it easier for pupils to leave lessons, or arranged appointments so that pupils did not miss the same lesson two weeks running. Bounceback staff also worked around the problem by seeing pupils during break time or using two members of staff to see people simultaneously in separate areas. Whilst pastoral staff acknowledged that some teachers could be ‘awkward’ about releasing young people from lessons (school staff 4), they did not seem to perceive the importance of improving communication (BB Staff 2).

Receipt and acceptability

Some young people were able to compare Bounceback with other services and said support from Bounceback was much better than they had received from Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services [CAMHS] (YP2, YP4, YP5), social services (YP2) and a private counsellor (YP4). One service user spoke of the staff's kindness in anticipating young people's needs by arranging free taxis and providing spending money for the trips they organised (YP4). Other comments confirmed the importance of key aspects of Bounceback's model of working. Interviewees valued the way in which Bounceback sessions created a safe environment, in which they could choose what to talk about:

… you can take as long as you want, you can talk about whatever you want. ‘You're here because you have this problem, that's what we want to talk about. But if you're not comfortable talking we won't.’ And that's the most important thing in it I think. (YP1)

Well all the other services I did … you know the NHS, and … it was all very clinical and it wasn't comfortable. I mean [Bounceback] made the effort sort of thing; it was little things like, you know, you could sit and you could eat with them … It's like you go in and they know how to make you feel warm and welcome. (YP4)

Another strength of the service for young people was the way in which Bounceback practitioners formed strong therapeutic relationships, based on trust and being listened to:

I sort of know it will be private cos I know [BB Staff 4]'s the kind of guy who won't just go blabbing out ‘Oh yeah I went to the school yeah and this guy's Nan died’. I know he's not that sort of person, I know my information is safe with him. I just feel really trusted with him. (YP6)

The willingness of the staff to base this relationship on a sense of equality and to talk through issues was also appreciated:

Barnardo's are more on your level. My counsellor would like look down at me—at one occasion he threw a pen at me and I asked him why. He told me it was to teach me about mistakes! Whereas Barnardo's will sit down and talk through it and say ‘Well maybe that wasn't the right thing to do’. (YP2)

… it was nice to know that they are not always going to have the answers… You kind of felt that even though they were older than you, you were kind of in the same boat, you were on the same level. (YP4)

Young people appreciated the support they had received to gain confidence (YP5) and to cope with a bereavement (YP6). They said that they felt better in terms of their emotional wellbeing and confidence and more able to deal with challenging issues and tasks. One felt that Bounceback had ‘inspired’ them to achieve more (YP4), whilst another described being able to join in conversations with ‘complete strangers' where before they would have said nothing. (YP5) Two said Bounceback had helped them to solve problems so that they were able to concentrate more on school work (YP6, YP7).

School staff remarked on differences in pupils' self-esteem and confidence. Some young people who rarely attended school started to stay longer in school, using Bounceback as a support base (BB Staff 1). These changes were seen as giving young people more chance of gaining qualifications that would enable them to secure jobs or further education (school staff 3, 4, BB Staff 3). Teaching staff also perceived benefits to the school more generally including helping to demonstrate their strategic commitment to the Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning (SEAL) scheme. Another teacher pointed out that Bounceback reduced the burden of trying to help children to cope with a range of problems that affected their capacity to learn well in school (school staff 4). Staff at all schools wanted Bounceback to continue indefinitely. They mentioned Bounceback's reliability and punctuality (school staff 1 & 2), the individual attention it provided (school staff 3) and its continuity of care for young people (school staff 4) as some of the best aspects of the service.

Discussion

To prevent harm from emotional/mental health problems, services such as Bounceback must ensure that young people feel able to engage with practitioners and accept help. The value of Bounceback to schools and pupils and the high levels of acceptability and it achieved appeared to be closely associated with the quality of relationships it built with pupils. This is in line with previous studies that have emphasised the centrality of therapeutic relationships to the delivery of support services, including the cultivation of trust, preservation of confidentiality, and a commitment to listening to young people (Le Surf & Lynch, 1999; Kay et al., 2006; Fox & Butler, 2007; Kidger et al., 2009). These were essential precursors to the therapeutic work that Bounceback undertook to increase in young people's emotional resilience—the ability to ‘bounce back from chronic or acute risk exposure’ (Meschke & Patterson, 2003). Resilience theory postulates that life brings events and disruptions that cause disorganisation in individuals' ways of dealing with the world. How an individual integrates new experiences influences how they cope with future challenges. The best response is resilience—the ability to learn from experiences and develop capacity to cope with further stressors. Individual skills/traits and support from someone who has resilient characteristics are important influences on the integration process (Richardson et al., 1990; Kaplan, 1999). Bounceback's emphasis on equipping young people with a ‘toolbox’ of strategies, together with emotional and practical support from a trusted person may increase their resilience. Its focus on the individual, rather than a particular problem, also fits well with the concept of resilience as a quality that varies with the nature of the challenge and the resources available to deal with it.

The building of relationships between Bounceback and schools was critical in order to allow the programme to be delivered as intended, mirroring the findings of previous studies which have highlighted how such relationships can affect the quality of accommodation provided (Kay et al., 2006), the extent of integration within school systems (Spratt et al., 2006) and schools' perceptions of external agencies' purpose (Baruch, 2001; Spratt et al., 2010). As Spratt et al. (2010) suggest, where schools focus on individualised problems at the expense of school environments, external agencies may occupy a peripheral space to which pupils with problems can be referred, but lack the necessary integration to influence school policies, secure suitable accommodation or achieve teachers' awareness of their aims. Langley et al. (2010) argue that a key strategy for increasing school ‘buy in’ is to arrange activities and in-service training for school staff. However, Bounceback staff—whilst valued by schools—were not fully integrated and struggled to establish regular communication and meetings. Through articulating a set of minimum criteria (around programme aims, referral processes and accommodation) they were able to run the programme as intended, but this was achieved only after persistent effort. There was no evidence that schools anticipated the needs of the service, had procedures in place for hosting services provided by external agencies or that they went beyond responding ad hoc to requests regarding accommodation and communication. Previous studies have suggested that external health practitioners can become isolated, especially if they are not well integrated within schools (Catron & Weiss, 1994; Adelman & Taylor, 1998; Baruch, 2001). Whilst relatively isolated within schools, the Bounceback programme was well integrated within its parent organisation (Barnardo's), which appeared to help it maintain its commitment to a particular set of values and ways of working with young people, echoing the findings of previous research that has identified the importance of clinical supervision and peer networks (Langley et al., 2010). Bounceback's wider organisational background gave the service access to resources which enabled staff to provide practical support and days out for young people—resources which not all practitioners might have access to.

Choice, too, was ‘isolated’ within the Bounceback service and did not extend to young people being able to decide independently of teachers that they wanted to access it. Spratt et al. (2010) argue that if schools control access to emotional/mental health services and refer on the basis of bad behaviour, this can create negative perceptions amongst pupils. They suggest that allowing pupils to engage independently and informally with support services (such as through drop-in sessions, social activities or just a place to eat lunch) is important, since these ‘zones of engagement’ allow relationships of trust to develop, and for pupils to make decisions about whether to seek formal help with a problem. Whilst Bounceback appeared to succeed in communicating to staff what constituted an appropriate referral, teachers retained the power to identify and prioritise pupils' problems. Schools rationalised a teacher-led referral system partly on the basis of maintaining the confidentiality of the service and avoiding stigmatisation processes that might occur if knowledge of its purpose was widespread. Another issue (acknowledged by all groups of participants in our study) was that raising awareness of the service and creating multiple routes of access could create a demand which could not be met from available resources. Like the informal zones of engagement described in Spratt et al.'s study, Bounceback sought to allow young people to define their needs and how they wanted to address them, and to build trust in practitioners. But although creating an informal space in which young people could talk about anything, or just eat lunch, formed an important aspect of Bounceback's work, it took place after referral by a teacher, not before/instead of such a referral.

Our findings echo those of previous studies that have drawn attention to the centrality of understanding how external agencies interact with schools and the challenges of integrating the values and systems of educational and health/welfare systems. Services such as Bounceback that operate in schools need to secure the basic conditions necessary for implementation (accommodation, a flow of referrals/applications and staff agreement to release pupils from class). As Cromarty and Richards (2009) argue in relation to school counsellors, building strong relationships with school staff can help facilitate implementation, and secure ‘good referrals' that are based on an accurate understanding of a service's ‘role and process' and Bounceback appears to have secured these conditions. External practitioners can be faced with a difficult decision about whether to optimise their service within existing school structures or to try and re-shape those structures, especially where they conflict with or undermine their work. Our research suggests it may be unrealistic for services such as Bounceback to take on this process, a finding which echoes those of Harris (2009) who also noted the significant emotional demands such conflicts can generate in practitioners such as school-based counsellors. Schools are tasked with and primarily judged by their educational success, with multiple time pressures and the need to timetable activities. But whilst external providers need to work flexibly within these constraints, the interdependence between educational achievement and well-being suggests a need for pastoral care and emotional support to be an integrated part of school's core function (Spratt et al., 2006). Optimising such support might benefit from a whole school approach which addresses all aspects of its life, including the social environment and school ethos and how these impact on the well-being and engagement of individual pupils (Wyn et al., 2000; Spratt et al., 2006). As Stewart et al. (2004, p. 27) argue in relation to the Health Promoting School (HPS):

The organisational and social factors inherent in the HPS approach foster children's emotional or psychological resilience by building resilience at an organisational level, such that resilient schools are healthy schools. A number of studies have found that factors inherent in the HPS framework, such as school organisational structures, educational practices, school climate and school–family and school–community relationships, are associated with the promotion of students' critical reflection, sense of belonging and sense of being socially supported, thus in turn promoting their resilience and mental health. (Battistich et al., 1995; Solomon et al., 1996)

Conclusion

The findings of this study suggest that Bounceback is a promising intervention, with the potential to improve young people's emotional health through promoting resilience. However, further research would be needed to ascertain Bounceback's impact on intended outcomes. Our exploratory study also has a number of other limitations, including the small number of schools and pupils that participated in the research and the fact that the research team could not approach Bounceback service users directly, due to data protection regulations. Whilst the interviews with young people highlighted key aspects of Bounceback which they found valuable, we cannot assume that their experiences are representative of all those who had used the service, nor of the views of those who had used other services such as counsellors and CAMHS. It is possible that the pupils who took part in the study were those most satisfied with Bounceback. On the other hand, the consistency of reports from different participant groups (pupils, school and Bounceback staff) lends strength to our data, and the absence of critical comments from young people's narratives (even when offered the opportunity to provide them) echoes the findings of previous studies (Cooper, 2009; McKenzie et al., 2011).

This study highlights a number of important issues concerning how support services for young people in schools are implemented. To provide support to young people Bounceback needed to develop relationships of trust. In turn, these relationships could not fully develop without schools' understanding of what it was trying to achieve and how they could help to create the necessary conditions. For instance, although young people may trust practitioners to maintain confidentiality (including the fact they are using a service), this could be undermined when the accommodation being used lacks privacy.

External practitioners working in schools therefore need to be skilled in securing the conditions necessary to work effectively within a complex organisational environment with a different core function. They should have a clear understanding of their service's remit and be able to articulate clearly to schools what is needed to achieve implementation as intended. Based on our findings, we suggest two other characteristics of externally-provided school support services that may enhance their implementation. Firstly, they need to have effective support from their parent organisation to minimise practitioners' feelings of isolation and to retain adherence to delivery models in challenging environments. Secondly, practitioners should assume that schools will not easily anticipate all their service's needs, but that over time school systems can be modified incrementally to enable them to be delivered as intended. Simply locating practitioners in schools will not automatically bring about integration of mental health provision, or remove barriers to service utilisation (Adelman & Taylor, 1998; Baruch, 2001; Spratt et al., 2010). Hawe et al. (2009, p. 270) suggest that interventions are ‘events' in complex, dynamic systems, which produce effects through interaction with particular contexts, and that ‘… the way an intervention comes to seep into or saturate its context becomes a way to view the extent of its implementation’. Bounceback's interaction was limited to a small number of staff in each school and could be likened to a droplet with high surface tension as opposed to ‘saturation’ in a challenging environment. This is not meant to detract from Bounceback staff's achievement in maintaining the coherence and values of their work. As our data suggest, Bounceback had gone some way to ensuring that staff understood the aims of the service and were thus making what Cromarty and Richards (2009) describe as ‘good referrals'. Communication channels were essential to achieving this, but they were focused on creating the necessary conditions for Bounceback to help young people, rather than a direct attempt to change school policies and procedures. Bringing about this wider change would appear to be a complex task requiring significant resources. But more pupils, as well as services such as Bounceback, could benefit from a ‘whole-school’ approach to emotional well-being that addresses environmental influences on pupils' well-being and demonstrates awareness and readiness to welcome external services wholeheartedly, because they contribute something valuable and relevant to school life.

Acknowledgements

DECIPHer is a UKCRC Public Health Research Centre of Excellence (http://www.decipher.uk.net/en/content/cms/about-decipher/ukcrc-public-health-/). Funding from the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Economic and Social Research Council (RES-590-28-0005), Medical Research Council, the Welsh Government and the Wellcome Trust (WT087640MA), under the auspices of the UK Clinical Research Collaboration, is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- Adelman H. S., Taylor L. Reframing mental health in schools and expanding school reform. Educational Psychologist. 1998;33:135–152. [Google Scholar]

- Allegrante J. P. Advancing the science and practice of school-based health promotion. Health Education Research. 2008;23:915–916. doi: 10.1093/her/cyn052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baruch G. Mental health services in schools: The challenge of locating a psychotherapy service for troubled adolescent pupils in mainstream and special schools. Journal of Adolescence. 2001;24:549–570. doi: 10.1006/jado.2001.0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battistich V., Solomon D., Kim D. I., Watson M., Schaps E. Schools as communities, poverty levels of student populations, and students' attitudes, motives, and performance—a multilevel analysis. American Educational Research Journal. 1995;32:627–658. [Google Scholar]

- Blum R. W., Nelson-Mmari K. The health of young people in a global context. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;35:402–418. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond L., Patton G., Glover S., Carlin J. B., Butler H., Thomas L., Bowes G. The gatehouse project: Can a multilevel school intervention affect emotional wellbeing and health risk behaviours? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2004;58:997–1003. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.009449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne G., Gafni A., Roberts J., Byrne C., Majumdar B. Effective/efficient mental health programs for school-age children: A synthesis of reviews. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;58:1367–1384. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00332-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catron T., Weiss B. The Vanderbilt school-based counseling program—an inter-agency, primary-care model of mental-health-services. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 1994;2:247–253. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M. Counselling in UK secondary schools: A comprehensive review of audit and evaluation data. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research. 2009;9:137–150. [Google Scholar]

- Cromarty K., Richards K. How do secondary school counsellors work with other professionals? Counselling and Psychotherapy Research. 2009;9:182–186. [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. Addressing the needs of youth in transition to adulthood. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2003;30:495–509. doi: 10.1023/a:1025027117827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson P., Coggan C., Bennett S. TRAVELLERS: A school-based early intervention programme helping young people manage and process change, loss and transition. Pilot phase findings. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;37:299–306. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2003.01181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlak J. A., Wells A. M. Evaluation of indicated preventive intervention (secondary prevention) mental health programs for children and adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1998;26:775–802. doi: 10.1023/a:1022162015815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman S. G., Olin S. S., Hoagwood K., Crowe M., Saka N. Evidence-based interventions in schools: Developers' views of implementation barriers and facilitators. School Mental Health. 2009;1:26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Fox C. L., Butler I. ‘If you don't want to tell anyone else you can tell her’: Young people's views on school counselling. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling. 2007;35:97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Fox C. L., Butler I. Evaluating the effectiveness of a school-based counselling service in the UK. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling. 2009;37:95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Hamblin D. The teacher and counselling. Oxford: Basil Blackwell; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Harris B. ‘Extra appendage’ or integrated service? School counsellors' reflections on their professional identity in an era of education reform. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research. 2009;9:174–181. [Google Scholar]

- Hawe P., Shiell A., Riley T. Theorising interventions as events in systems. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2009;43:267–276. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9229-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan H. B. Toward an understanding of resilience: A critical review of definitions and models. In: Glantz M. D., Johnson J. L., editors. Resilience and development: Positive life adaptations. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 1999. pp. 17–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kay C. M., Morgan D. L., Tripp J. H., Davies C., Sykes S. To what extent are school drop-in clinics meeting pupils' self-identified health concerns? Health Education Journal. 2006;65:236–251. [Google Scholar]

- Kidger J., Donovan J. L., Biddle L., Campbell R., Gunnell D. Supporting adolescent emotional health in schools: A mixed methods study of student and staff views in England. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:403. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimber B., Sandell R., Bremberg S. Social and emotional training in Swedish schools for the promotion of mental health: An effectiveness study of 5 years of intervention. Health Education Research. 2008;23:931–940. doi: 10.1093/her/cyn040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley A. K., Nadeem E., Kataoka S. H., Stein B. D., Jaycox L. H. Evidence-based mental health programs in schools: Barriers and facilitators of successful implementation. School Mental Health. 2010;2:105–113. doi: 10.1007/s12310-010-9038-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Surf A., Lynch G. Exploring young people's perceptions relevant to counselling: A qualitative study. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling. 1999;27:231–243. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie K., Murray G. C., Prior S., Stark L. An evaluation of a school counselling service with direct links to child and adolescent mental health (CAMH) services. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling. 2011;39:67–82. [Google Scholar]

- Meschke L. L., Patterson J. M. Resilience as a theoretical basis for substance abuse prevention. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2003;23:483–514. [Google Scholar]

- Patel V., Flisher A. J., Hetrick S., McGorry P. Adolescent health 3—mental health of young people: A global public-health challenge. Lancet. 2007;369:1302–1313. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60368-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton G. C., Glover S., Bond L., Butler H., Godfrey C., Di Pietro G., Bowes G. The gatehouse project: A systematic approach to mental health promotion in secondary schools. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;34:586–593. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2000.00718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto-Foltz M. D., Logsdon M. C., Myers J. A. Feasibility, acceptability, and initial efficacy of a knowledge-contact program to reduce mental illness stigma and improve mental health literacy in adolescents. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;72:2011–2019. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson G. E., Neiger B. L., Jensen S., Kumpfer K. L. The resiliency model. Health Education. 1990;21:33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ringeisen H., Henderson K., Hoagwood K. Context matters: Schools and the ‘research to practice gap’ in children's mental health. School Psychology Review. 2003;32:153–168. [Google Scholar]

- Rones M., Hoagwood K. School-based mental health services: A research review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2000;3:223–241. doi: 10.1023/a:1026425104386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shandley K., Austin D., Klein B., Kyrios M. An evaluation of ‘Reach Out Central’: An online gaming program for supporting the mental health of young people. Health Education Research. 2010;25:563–574. doi: 10.1093/her/cyq002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon D., Watson M., Battistich V., Schaps E., Delucchi K. Creating classrooms that students experience as communities. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1996;24:719–748. [Google Scholar]

- Spence S. H., Shortt A. L. Research review: Can we justify the widespread dissemination of universal, school-based interventions for the prevention of depression among children and adolescents? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48:526–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spratt J., Shucksmith J., Philip K., Watson C. ‘Part of Who we are as a School Should Include Responsibility for Well-Being’: Links between the school environment, mental health and behaviour. Pastoral Care. 2006;24:14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Spratt J., Shucksmith J., Philip K., Watson C. ‘The Bad People Go and Speak to Her’: Young people's choice and agency when accessing mental health support in school. Children & Society. 2010;24:483–494. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart D., Sun J., Patterson C., Lemerle K., Hardie M. Promoting and building resilience in primary school communities: Evidence from a comprehensive ‘Health Promoting School Approach’. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion. 2004;6:26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Waters E. B., Salmon L. A., Wake M., Wright M., Hesketh K. D. The health and well-being of adolescents: A school-based population study of the self-report child health questionnaire. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;29:140–149. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weist M. D., Lowie J. A., Flaherty L. T., Pruitt D. Collaboration among the education, mental health, and public health systems to promote youth mental health. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:1348–1351. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.10.1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weist M. D., Mellin E. A., Chambers K. L., Lever N. A., Haber D., Blaber C. Challenges to collaboration in school mental health and strategies for overcoming them. Journal of School Health. 2012;82:97–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz J. R., Chu B. C., Polo A. J. Treatment dissemination and evidence-based practice: Strengthening intervention through clinician-researcher collaboration. Clinical Psychology-Science and Practice. 2004;11:300–307. [Google Scholar]

- Wyn J., Cahill H., Holdsworth R., Rowling L., Carson S. MindMatters, a whole-school approach promoting mental health and wellbeing. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;34:594–601. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2000.00748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]