Abstract

Background

Computerized chronic disease management systems (CDMSs), when aligned with clinical practice guidelines, have the potential to effectively impact diabetes care.

Objective

The objective was to measure the difference between optimal diabetes care and actual diabetes care before and after the introduction of a computerized CDMS.

Methods

This 1-year, prospective, observational, pre/post study evaluated the use of a CDMS with a diabetes patient registry and tracker in family practices using patient enrolment models. Aggregate practice-level data from all rostered diabetes patients were analyzed. The primary outcome measure was the change in proportion of patients with up-to-date “ABC” monitoring frequency (i.e., hemoglobin A1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol). Changes in the frequency of other practice care and treatment elements (e.g., retinopathy screening) were also determined. Usability and satisfaction with the CDMS were measured.

Results

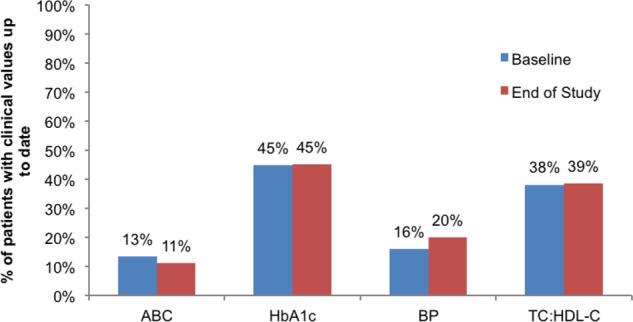

Nine sites, 38 health care providers, and 2,320 diabetes patients were included. The proportion of patients with up-to-date ABC (12%), hemoglobin A1c (45%), and cholesterol (38%) monitoring did not change over the duration of the study. The proportion of patients with up-to-date blood pressure monitoring improved, from 16% to 20%. Data on foot examinations, retinopathy screening, use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blockers, and documentation of self-management goals were not available or not up to date at baseline for 98% of patients.

By the end of the study, attitudes of health care providers were more negative on the Training, Usefulness, Daily Practice, and Support from the Service Provider domains of the CDMS, but more positive on the Learning, Using, Practice Planning, CDMS, and Satisfaction domains.

Limitations

Few practitioners used the CDMS, so it was difficult to draw conclusions about its efficacy. Simply giving health care providers a potentially useful technology will not ensure its use.

Conclusions

This real-world evaluation of a web-based CDMS for diabetes failed to impact physician practice due to limited use of the system.

Plain Language Summary

Patients and health care providers need timely access to information to ensure proper diabetes care. This study looked at whether a computer-based system at the doctor’s office could improve diabetes management. However, few clinics and health care providers used the system, so no improvement in diabetes care was seen.

Background

Objective

The objective of this study was to measure the difference between optimal diabetes care (as recommended by clinical practice guidelines [CPGs]) and actual diabetes care (as provided in primary care clinical practice) before and after the introduction of a computerized chronic disease management system (CDMS).

Clinical Need and Target Population

Description of Disease

Diabetes is a chronic metabolic condition characterized by hyperglycemia, and it affects more than 2 million Canadians. (1;2) Left uncontrolled, hyperglycemia can lead to serious complications (e.g., kidney disease, blindness, amputation, cardiovascular disease) and, ultimately, premature death. (3) In 2008, the Canadian Diabetes Association published the updated Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Diabetes in Canada, (1) providing evidence-based guidelines for optimal diabetes management.

The government of Ontario has been investing in numerous initiatives to help improve the delivery of recommended diabetes care (e.g., diabetes education centres, insulin pumps for type 1 diabetes, medications for people aged 65 years and older). (4) Despite such efforts, however, a gap still remains between evidenced-based recommendations and actual patient care. (5-7)

Technology/Technique

Optimal diabetes care involves management by health care professionals, as well as patient education and self-management, and it depends heavily on the flow of timely, accurate information to both providers and patients. However, it can be difficult for clinicians in a busy clinical practice to consistently adhere to CPGs. In fact, doing so may be nearly impossible without a clinical information system that can compare biomedical patient data with applicable CPGs to enable, facilitate, and sustain chronic disease management. Computerized CDMSs aligned with the recommendations of CPGs may play a role in improving diabetes care. (8)

Chronic Disease Management Systems

To be effective, a CDMS must be multifaceted and give clinicians ongoing support driven by clinical data. In particular, data-integrating and data-reporting CDMSs can help to better direct timely communication between patients and health care teams, focusing on elements of care that need the most improvement and attention. An effective CDMS should include the following: (9;10)

electronic patient registries to identify and track patients grouped by subpopulation (e.g., by chronic disease)

clinician reminders for care that is due and overdue, organized by patient (for use in opportunistic care) and by registry (for use in proactive care management at the practice level)

patient reminders for care that is due and overdue

ongoing self-audit performance measurement and feedback reporting for clinicians at the practice level

a foundation in evidence-based CPGs

In 2007, the Medical Advisory Secretariat (now Health Quality Ontario) reviewed the published literature on the efficacy and effectiveness of multifaceted information technology aimed at improving the outcomes of patients with type 2 diabetes (2007 unpublished report, Medical Advisory Secretariat). One of the aims of the review was to evaluate an integrated approach that used multiple types of information technology to target patients and/or health care providers and increase adherence to CPGs for diabetes management. The review found that although integrated information technology appeared to be promising, no definitive conclusion could be reached about its role in improving hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels, reducing complication rates, or improving survival in people with type 2 diabetes. In response to these findings, the current study was designed to evaluate whether a CDMS introduced in Ontario primary care practices as a part of routine clinical management could improve the proportion of diabetes patients who received HbA1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol monitoring as recommended by the CPGs.

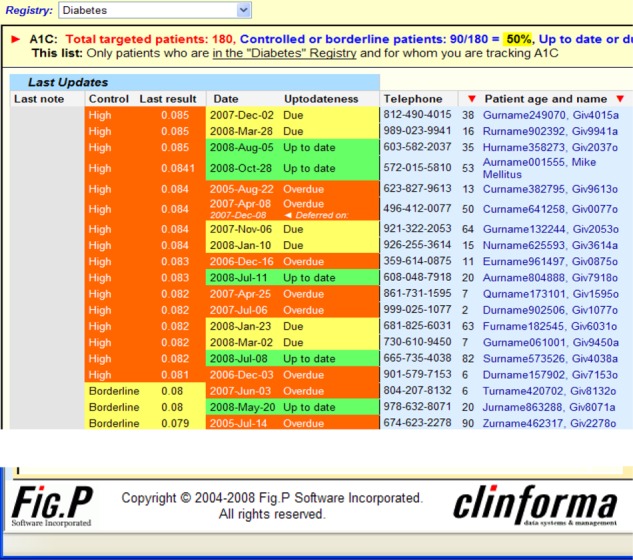

P-PROMPT

The electronic CDMS evaluated in this study was initially developed to manage preventative care. It was first used to acquire and integrate data from external sources and provide data-driven supports to clinicians and patients, as a way of fostering systematic and timely regular Pap testing and screening mammography in eligible patients. An evaluation of this system demonstrated substantial improvements in preventive-care quality gaps in patients whose health care provider received the CDMS (i.e., patients were significantly more up to date on screening). (11) Based on these findings, the scope of the CDMS was fully extended to support over 20 of the most common chronic diseases, including diabetes, congestive heart failure, cigarette smoking, hypertension, and osteoporosis. This CDMS was called Provider and Patient Reminders in Ontario: Multi-Strategy Prevention Tools (P-PROMPT).

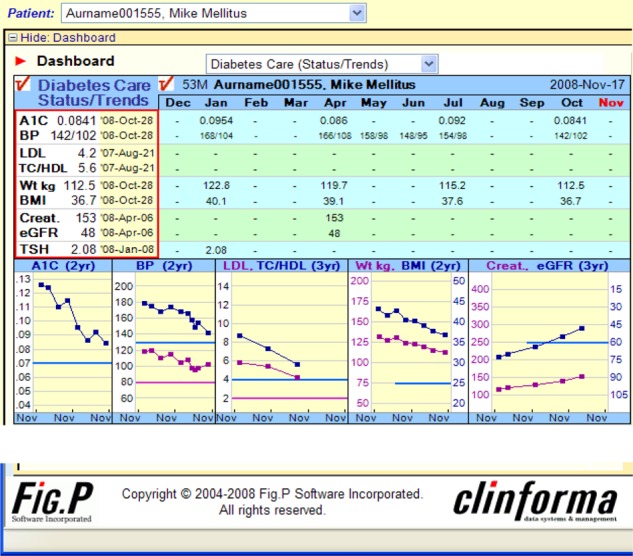

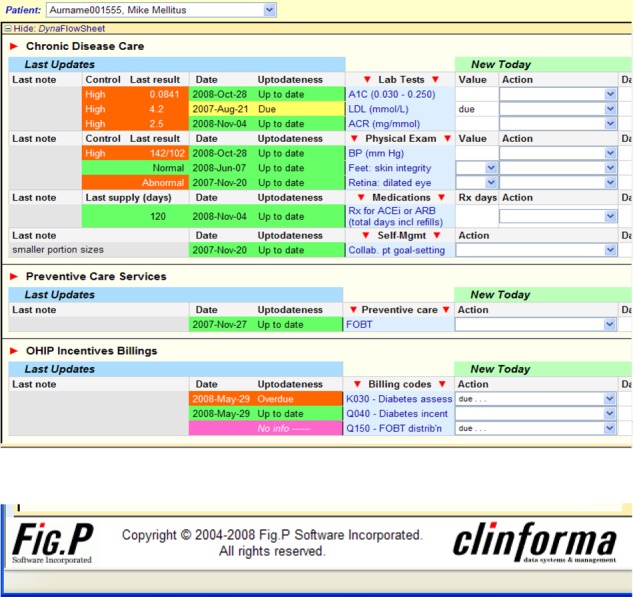

P-PROMPT is a secure web application with a centralized data repository and extensive clinical data warehousing that together provides large-scale, multi-source clinical data throughput; embedding and maintenance of diverse current CPGs; and ongoing feedback summary and detail reporting at the patient, provider, care team, regional, and provincial aggregate levels. It maintains an electronic registry of all patients rostered to a primary care practitioner; can enter individuals in multiple disease registries; and integrates all patient comorbidities and their combined care targets.

At the patient level, the system tracks, displays, and reports the last result and time since the last result for each care component (e.g., tests, examinations, counselling/education, prescriptions); colour-codes results (green, yellow, red) according to compliance with relevant guidelines; provides a dashboard summary of the patient’s current overall care status and a flow sheet of recent progress; accepts and integrates new clinical data into the patient’s flow sheet; assembles a care episode summary note for transfer into the electronic medical record; and automatically acquires and integrates all relevant electronic laboratory results.

At the disease level, P-PROMPT displays and reports lists of all patients, sorted in order of urgency of need, based on either lack of control or time elapsed since care; provides a dashboard summary of the registry’s current overall care performance measures and a chart of recent performance progress; and permits approval of a patient list for reminder letters.

At the practice level, P-PROMPT captures and integrates data automatically from multiple sources, including electronic files uploaded from laboratories, Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care roster data, billing claims codes, and others. It then provides accountable claims-eligibility reports for Ontario Health Insurance Plan performance-bonus and incentive-fee billings.

The development of P-PROMPT was aligned with the Quality Improvement and Innovation Program, an Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care Quality Management Collaborative, which is now under Health Quality Ontario. The tracking tools in P-PROMPT are aligned with the 2008 Canadian Diabetes Association CPGs for diabetes (1) and the Ontario Health Insurance Plan physicians’ chronic disease management incentive fees.

Field Evaluation

Research Questions

What was the absolute change from baseline in the proportion of patients in each practice who had up-to-date monitoring of HbA1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol (“ABC”) in practices using a CDMS for 1 year?

What was the mean change from baseline in up-to-date clinical values for HbA1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol (total cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [HDL-C] ratio, HDL-C, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol [LDL-C])?

What was the mean change from baseline in use of other care and treatment elements (foot examination, retinopathy screening, use of angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers [ARBs], microalbuminuria testing, and documentation of self-management goals)?

What was the primary health care team’s evaluation of P-PROMPT with respect to Learning, Training, Using, Usefulness, Daily Practice, Practice Planning, CDMS, Support from Service Provider, and Satisfaction?

Research Methods

Study Design

This 1-year prospective, observational, pre/post, comparative study evaluated the use of a CDMS with a diabetes patient registry and tracker in family practices using patient enrolment models. The unit of evaluation was the individual primary care practitioner. The study analyzed aggregate practice-level data from all rostered diabetes patients in each practice.

Study Population

Primary care practitioners (physicians or nurse practitioners) working in a patient enrolment model in Ontario who met all inclusion and exclusion criteria were invited to participate in the study. For the purpose of the study, a site consisted of 1 or more primary care practitioners enrolled in the study, along with associated team members. Sites were recruited across the province over a 13-month period and followed prospectively for 1 year.

Inclusion Criteria

Ontario primary care practitioners with a patient roster who were able to provide a list of patients in their practice

high-speed Internet access in the practice environment, or willingness to obtain high-speed Internet access (required to access the web-based CDMS)

physicians willing to use the CDMS or already using it at the time of recruitment

Exclusion Criteria

To avoid interference with other provincial diabetes initiatives, Ontario primary care practitioners involved in the Quality Improvement and Innovation Program Learning Collaborative who were practicing in 1 of the following Local Health Integration Networks were excluded: South West, Toronto Central, Champlain, and North West.

Study Intervention

The intervention evaluated in this study was the provision of access to P-PROMPT, a web-based CDMS to evaluate the effect of its deployment and routine use on the quality of diabetes care (the system included the Canadian Diabetes Association 2008 CPGs (3)). Except for a study-specific information session, participating sites were set up with the CDMS in the same manner as sites that subscribe to the system. Setup involved a short initial training and demonstration session, including cases; an automated initial prepopulation of the system with the site’s complete electronic patient roster; an initial 3-year back-population of pertinent clinical laboratory test result data and Ontario Health Insurance Plan incentive-fee billings, where available; and automated ongoing data updates throughout the study period. User support was provided as normal, but no training beyond the level provided to regular CDMS subscribers was offered.

Outcomes of Interest

Primary Outcome

Proportion of “ABC” (HbA1c, Blood Pressure, and Cholesterol) Values Up To Date

The primary outcome measure was change from baseline in the proportion of patients in each practice with optimal “ABC” monitoring for diabetes care: HbA1c at least once per 184-day period, blood pressure at least once per 365-day period, and cholesterol at least once per 184-day period. This composite outcome was considered more appropriate than individual measures, because practice-level monitoring processes should be adopted across multiple measures to improve diabetes care. To assess this composite outcome, the proportion of patients with up-to-date monitoring in each practice was calculated for all 3 parameters simultaneously, both at baseline and 1 year. Then, the absolute difference in proportion of patients with up-to-date monitoring between the 2 time points was calculated.

Secondary Outcomes

Proportion of HbA1c, Blood Pressure, and Cholesterol Values Up To Date

The proportion of patients with up-to-date monitoring for each of the individual clinical values (i.e., HbA1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol) was also calculated at baseline and 1 year. (1) These data were used to determine the absolute difference in proportion of patients with up-to-date monitoring between the 2 time points.

Mean Change in HbA1c, Blood Pressure, and Cholesterol Values

Aggregate practice-level data and patient-level data were used to examine the mean change in clinical values across and within practices from baseline to 1 year for HbA1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol (TC:HDL-C, HDL-C, and LDL-C).

Care and Treatment Elements

Aggregate practice-level data were used to calculate the mean change from baseline in use of other care and treatment elements: the percentage of patients with an up-to-date foot examination, up-to-date retinopathy screening, use of ACE inhibitors or ARBs, and documentation of self-management goals.

P-PROMPT Implementation, Training, and Impact

The primary health care team’s appraisals of P-PROMPT were examined via questionnaire with respect to the following domains: Learning, Training, Using, Usefulness, Daily Practice, Practice Planning, CDMS, Support from the Service Provider, and Satisfaction. Each domain was evaluated using several questions.

All questions were phrased using a 5-point Likert scale in a positive direction, where completely agree was a positive response and completely disagree was a negative response (Appendix 1). All physicians enrolled in the study were asked to complete periodic questionnaires, at 2 months, 6 months, and 12 months.

Data Management

Primary Care Practice Data

Permission was requested from primary care practitioners for access to a de-identified copy of their electronic practice patient dataset, available only at the CDMS vendor’s site, for the purpose of completing analyses of practice and clinical outcomes. Aggregate monthly practice-level summary data were obtained from the CDMS vendor. A 3-way agreement between primary care practitioners, the Programs for Assessment of Technology in Health (PATH) Research Institute, and Fig.P Software Inc. described the terms of the data sharing.

Questionnaires

Anonymized questionnaires were received from participating primary care practice team members using a fax service provider (PROTUS, Ottawa, Ontario). Transmissions were stored on PROTUS servers for 30 days, and then old transmissions were purged when the storage period ran out. PROTUS uses industry-standard means to safeguard the confidentiality of transmissions, including firewalls and SSL technology. All documents faxed to PATH’s designated 1-800 number were forwarded to PATH directly via a secure server with SSL encryption (using Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act standards Section 4.7[11] 3) onto a data server with 128-bit Verisign SSL Certification and 1024 Bit RSA public keys.

Statistical Analysis

Sample Size Calculation

According to an Ontario Health Quality Council report, patients with diabetes were receiving the following levels of care, on average: 48% received regular HbA1c checks; 35% received blood pressure checks and related medication evaluations; and 64% received cholesterol checks and related medication evaluations. (12) Overall, an average of 49% of patients were receiving the recommended frequency of diabetes care. (12)

To produce an increase of 5% (from 49% to 54%) in the percentage of patients who met care guidelines, a sample size of 2,138 was required to achieve 90% power. Accounting for a 10% loss to follow-up, a sample size of 2,376 patients with diabetes was targeted for the study. The average roster size of primary care practitioners is estimated to be 1,244 patients. (13) In the 2005 Canadian Community Health Survey, 4.8% of people in Ontario reported being diagnosed with diabetes by a physician—or 60 diabetes patients per roster. (6) Therefore, the target number of primary care practices required to achieve the target patient population was 40.

Statistical Methods

The unit of evaluation was the primary care practice, and both aggregate practice-level data and patient-level analyses were obtained for statistical analysis. Using a before-and-after design, changes from the beginning of the study to the end in each of the monitoring parameters of interest were calculated. Values at the beginning of the study were subtracted from values at the end, and the average change for the population was calculated, with an associated measure of variance. Statistical comparisons were made using paired t-tests or chi-squared tests, and results reported as means and standard deviations or percentages, respectively. All test instruments were scored according to recommendations for the particular tests. The change in shift of distribution of ordinal scales was analyzed using the Goodman and Kruskal’s gamma test. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA Statistical Software, Release 13 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Post Hoc Analyses

Login and screening viewing data for each participating health care provider were obtained from the vendor to examine the frequency of use of the CDMS. Both practice- and provider-level analyses were conducted. Data were normalized by the number of patients identified in the diabetes registries.

Results

Participating Primary Care Sites

Sites: Baseline Characteristics

Eleven primary care practices were enrolled. However, 1 site discontinued the study prior to activating the CDMS. Ten sites activated the CDMS and provided baseline characteristics (Table 1). Of the 39 participating health care providers, 35 were physicians and 4 were nurse practitioners. Each site had an average of 4 health care providers (minimum, 1; maximum, 14). The total number of diabetes patients at baseline represented approximately 9.8% of the total patient roster (range, 3.0% to 19.8%).

Table 1: Baseline Characteristics of Enrolled Sites.

| Sites | Physicians/Nurse Practitioners per Site | Patients With Diabetes | Mean Number of Patients With Diabetes per Provider | Practice Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 186 | 186 | Family health team |

| 2 | 3 | 381 | 127 | Family health team |

| 3 | 6 | 424 | 71 | Family health team |

| 4 | 14 | 248 | 18 | Family health team |

| 5 | 8 | 675 | 84 | Family health team |

| 6 | 1 | 23 | 23 | Family health team |

| 7 | 2 | 208 | 104 | Family health team |

| 8 | 2 | 67 | 34 | Family health team |

| 9 | 1 | 48 | 48 | Community health centre |

| 10 | 1 | 108 | 108 | Family health team |

| Total | 39 | 2,368 | 61 | — |

The sites had used 7 different types of electronic medical record systems for approximately 3.5 years (minimum, 6 months; maximum, 6 years). None of the sites had used the P-PROMPT CDMS prior to enrolling in the study, and 9 of the 10 sites received electronic laboratory results.

One site withdrew prior to validation of the diabetes patient list. As a result, analysis of the clinical data and utilization patterns was conducted on the 9 remaining sites (N = 2,320). Of the 9 sites, 6 were followed up for at least 12 months, 1 for 10 months, and 2 for 9 months.

Sites: Practice Participation/Engagement

Table 2 presents staff participation rates by specialty. The median number of medical and administrative staff who had access to the CDMS and who logged into the system at least once at each site was 1 physician, half a nurse practitioner, and 1 nurse, from a total staff complement of 5. Overall, only 51% of the staff complement at the sites participated in the study.

Table 2: Study Participation by Specialty.

| Health Care Provider | Total at Site, n | Participating, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Physicians | 43 | 22 (51) |

| Nurse practitioners | 15 | 7 (47) |

| Nurses | 29 | 22 (76) |

| Dietitians | 8 | 3 (38) |

| Pharmacists | 2 | 1 (50) |

| Respiratory therapists | 2 | 1 (50) |

| Administrative staff | 22 | 9 (41) |

| Clerical/billing staff | 26 | 6 (23) |

Patients: Baseline Characteristics

The demographic characteristics of the diabetes patients were similar across the 9 sites, with an overall mean age of 63 years (standard deviation 14 years). Fifty-two percent of subjects were male, and mean patient body mass index was 31.1 kg/m2 (in the obese range).

Primary Outcome (ABC)

At baseline, only 13% of patients (311/2,320) had all 3 measures up to date (Figure 1). The proportion of patients with up-to-date measurements varied by site, from 0% to 59.1%. At the end of the study, the proportion of patients with ABC monitoring up to date had decreased to 11% (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Proportion of Patients With Clinical Values Up to Date in the CDMS.

Abbreviations: ABC, hemoglobin A1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol; BP, blood pressure; CDMS, chronic disease management system; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TC, total cholesterol.

Secondary Outcomes

Proportion of HbA1c, Blood Pressure, and Cholesterol Values Up To Date

At baseline, HbA1c was most frequently up to date (n = 1,030) (Figure 1), but of those with up-to-date HbA1c measurements, only 28% of the values were within the target range. Blood pressure was up to date in only 368 patients, and 16% of those measurements were in the target range. Cholesterol measurements were up to date in 883 patients, and 24% of those measurements were in the target range. The percentage of patients with up-to-date clinical values varied by site (HbA1c, 12.1% to 74.1%; blood pressure, 0% to 90.3%; cholesterol, 11.3% to 65.1%).

At the end of the study, the proportion of patients with HbA1c and cholesterol measurements up to date remained unchanged (Figure 1). The proportion of patients with up-to-date blood pressure monitoring increased by 4%.

Mean Change in HbA1c, Blood Pressure, and Cholesterol Values

For patients who had at least 2 test results and measurements up to date, mean baseline and end-of-study values for HbA1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol are presented in Table 3. At the end of the study, there was a statistically significant reduction from baseline in diastolic blood pressure and TC:HDL-C. Mean HbA1c levels increased slightly over the study period.

Table 3: Change in Clinical Values From Baseline to End of Study.

| Clinical Parameter | N | Baseline Mean (SD) | 12 Months Mean (SD) | Change | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | 95% CI | P value | ||||

| HbA1c, % | 761 | 7.07 (1.30) | 7.08 (1.25) | 0.01 (0.96) | –0.06, 0.08 | 0.809 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 308 | 128.7 (15.2) | 127.1 (17.3) | –1.5 (18.2) | –3.5, 0.5 | 0.129 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 308 | 76.5 (10.9) | 75.3 (11.4) | –1.2 (10.5) | –2.4, 0.0 | 0.042 |

| TC:HDL-C | 584 | 3.81 (1.18) | 3.66 (1.10) | –0.16 (0.90) | –0.23, –0.09 | 0.001 |

Abbreviations: HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; BP, blood pressure; CI, confidence interval; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; SD, standard deviation; TC, total cholesterol.

Care and Treatment Elements

The proportion of patients with up-to-date foot examinations, up-to-date retinopathy screening, use of ACE inhibitors and/or ARBs, and documentation of self-management goals was also measured. At baseline, data were unavailable or not up to date almost all patients (Table 4). By the end of the study, the proportion of patients with up-to-date monitoring had decreased for all care and treatment elements.

Table 4: Care and Treatment Elements (N = 2,320).

| Element | Up to Date at Baseline, N (%) | Up to Date at End of Study, N (%) | Mean Change, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Foot examination | 28 (1.2) | 5 (0.2) | –1 |

| Retinopathy screening | 13 (0.6) | 1 (0.04) | –0.56 |

| Use of ACE inhibitors/ARBs | 46 (2.0) | 10 (0.4) | –1.6 |

| Documentation of self-management goals | 55 (2.4) | 0 (0) | –2.4 |

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker.

Satisfaction/Usability of P-PROMPT, Training and Impact

Of the 38 health care providers included in the analysis, 21 (55%) completed the baseline (2-month) questionnaire. The percentage of positive responses (mostly agree and completely agree) was higher than that of negative responses (strongly disagree and somewhat disagree) in 6 of the 9 categories (Table 5): Learning, Using, Practice Planning, CDMS, Support from the Service Provider, and Satisfaction. All categories had a positive trend, except for Daily Practice (e.g., “I use it during patient visits,” “It assists in determining which tests and/or procedures are overdue for patients with diabetes”), where the group seemed to be divided.

Table 5: Evaluation of the CDMS: Baseline Site Questionnaire (N = 21)a.

| N | Completely Disagree | Somewhat Disagree | Slightly Agree | Mostly Agree | Completely Agree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Learning | 11.6% | 12.2% | 21.8% | 43.5% | 10.9% | |

| I quickly learn how to use it | 21 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 12 | 1 |

| I easily remember how to use it | 21 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 13 | 1 |

| It provides the ease of learning I need | 21 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 10 | 1 |

| It would be easy for me to improve my skill at using it | 21 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 12 | 3 |

| I am confident that I can learn new functions of it | 21 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 12 | 2 |

| I would like to learn more about how to use it | 21 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 8 |

| I am proficient in using it | 21 | 5 | 4 | 10 | 2 | 0 |

| Training | 19.8% | 21.0% | 21.0% | 34.6% | 3.7% | |

| I am satisfied with the training I received | 21 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 0 |

| It is easy for me to train someone to use it | 21 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 1 |

| It is easy for me to receive training from co-workers on how to use it | 20 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 2 |

| Supplemental reference material is easy to follow | 19 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 0 |

| Using | 14.3% | 16.2% | 28.6% | 38.1% | 2.9% | |

| I find it easy to use | 21 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 10 | 1 |

| I can use it without written instructions | 21 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 9 | 1 |

| I recover from mistakes quickly and easily | 21 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 0 |

| I can use it successfully every time | 21 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 6 | 0 |

| Performing tasks are straightforward | 21 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 7 | 1 |

| Usefulness | 17.6% | 16.8% | 36.0% | 24.8% | 4.8% | |

| It helps my performance in my role | 21 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 5 | 1 |

| It helps me to be more productive in my role | 21 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 1 |

| It helps me be more effective in my role | 21 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 3 | 1 |

| It provides me useful information to do my job well | 21 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 2 |

| It provides more control over my daily work activities | 21 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 3 | 1 |

| It does everything I would expect it to do | 20 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 7 | 0 |

| Daily Practice | 34.6% | 11.3% | 13.8% | 34.6% | 5.7% | |

| I use it during patient visits | 20 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| It is easy to check patient data | 20 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 1 |

| It assists me to provide patient diabetes education | 20 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 1 |

| It helps me to quickly review the patient’s diabetes status | 20 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 1 |

| It helps me to quickly review the patient’s diabetes trends | 20 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 1 |

| It assists in determining which tests and/or procedures are overdue for patients with diabetes | 20 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 2 |

| It improves the quality of time with the patient | 20 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 1 |

| I am confident that it protects patient data confidentiality | 19 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 11 | 1 |

| Practice Planning | 14.5% | 19.6% | 26.8% | 33.0% | 6.1% | |

| It assists in setting practice goals | 20 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 6 | 0 |

| It assists in achieving practice goals | 20 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 7 | 0 |

| It helps me to quickly obtain an overview the practice status | 20 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 9 | 1 |

| It helps me to quickly review my practice improvements over time | 20 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 5 | 0 |

| It provides sufficient information to evaluate my overall performance in diabetes management | 19 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 1 |

| It represents patient-centred care | 20 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 9 | 1 |

| It allows team members to work at an enhanced professional level | 20 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 2 |

| It will assist the practice with obtaining incentive fees | 20 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 3 |

| It assists with preparing the monthly reports | 20 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 |

| CDMS | 14.8% | 10.9% | 19.5% | 49.0% | 5.9% | |

| It is easy to read the characters on the screens | 21 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 9 | 3 |

| Highlighting simplifies what I should focus on as important information | 21 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 9 | 3 |

| Organization of display screens is easy to follow | 21 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 2 |

| Arrangement of screens is simple to follow | 21 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 10 | 2 |

| It provides a user-friendly interface | 21 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 11 | 1 |

| Program pop-up messages are easy to understand | 21 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 10 | 1 |

| The output options (e.g. print chart notes, print patient list, transfer to EMR) are sufficient for my use | 21 | 4 | 2 | 8 | 6 | 1 |

| Automated data input functions (e.g., incentive code billings, laboratory data) are sufficient for my use | 20 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 8 | 1 |

| System speed is fast enough | 21 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 13 | 1 |

| It is reliable | 20 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 12 | 1 |

| Correcting mistakes is easy | 21 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 10 | 0 |

| It is easy to display the current status of a single patient | 20 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 12 | 1 |

| It is easy to update a single element of a patient’s records | 20 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 9 | 2 |

| It is easy to update multiple elements of a patient’s record | 20 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 2 |

| It is easy to display patient summary dashboards | 21 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 11 | 1 |

| It is easy to add (roster) a new patient | 21 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 11 | 1 |

| It is easy to remove (de-roster) a new patient | 21 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 10 | 2 |

| It is easy to display a patient’s history of a single care element | 21 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 9 | 2 |

| It is easy to display a list of patients in a registry | 21 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 11 | 2 |

| It is easy to create registry list(s) and action/recall lists for printout | 21 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 10 | 0 |

| It is easy to update the care element status list(s) | 21 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 11 | 1 |

| It is easy to display practice registry summary dashboards | 21 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 11 | 1 |

| It is easy to display registry summary statistics | 21 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 12 | 0 |

| It is easy to edit care/tracking plans of patient(s) in a registry | 20 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 8 | 1 |

| It is easy to display a list of all patients in MD roster | 21 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 12 | 1 |

| It is easy to display lists of available registries with editable MD activations and default care/tracking plans | 21 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 12 | 0 |

| It is easy to display lists of patients who have invalid data, with editable data | 19 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 8 | 0 |

| I am satisfied with the way the information is organized | 21 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 11 | 1 |

| Support from the Service Provider | 6.0% | 11.9% | 19.4% | 35.8% | 26.9% | |

| I am always treated courteously and in a professional manner by the service provider | 17 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 6 |

| The technical support provided by the service provider is helpful to resolve my problems | 17 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 4 |

| The service provider resolves my questions within a reasonable time | 17 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 4 |

| Additional training is available when I ask for it | 16 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| Satisfaction | 10.1% | 13.8% | 27.5% | 44.2% | 4.3% | |

| It provides the precise information I need to manage patients more effectively | 19 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 11 | 1 |

| It is fun to use | 20 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 7 | 1 |

| I would recommend it to others | 20 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 2 |

| It works the way I want it to work | 20 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 11 | 0 |

| If I would like to continue to use it in my daily practice | 19 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 1 |

| It is designed for all levels of computer users | 20 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 0 |

| Overall, I am satisfied with it | 20 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 10 | 1 |

Abbreviations: EMR, electronic medical record.

Percentages may appear inexact due to rounding.

Nine health care providers (24%) also completed the end-of-study questionnaire and expressed satisfaction with the CDMS; more than 50% of respondents indicated that they either “mostly” or “completely” agreed in all of the categories but Usefulness (Table 6).

Table 6: Evaluation of the CDMS: Change From Baseline to End of Study (N = 9)a.

| Completely Disagree | Somewhat Disagree | Slightly Agree | Mostly Agree | Completely Agree | Gamma | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Learning | 2 months | 0.0% | 4.8% | 20.6% | 55.6% | 19.0% | ||

| 12 months | 3.3% | 3.3% | 21.3% | 49.2% | 23.0% | |||

| Change | 3.3% | –1.5% | 0.7% | –6.4% | 3.9% | 0.008 | 0.149 | |

| Training | 2 months | 0.0% | 6.1% | 33.3% | 51.5% | 9.1% | ||

| 12 months | 5.7% | 11.4% | 25.7% | 40.0% | 17.1% | |||

| Change | 5.7% | 5.4% | –7.6% | –11.5% | 8.1% | –0.042 | 0.190 | |

| Using | 2 months | 0.0% | 6.7% | 35.6% | 51.1% | 6.7% | ||

| 12 months | 0.0% | 11.6% | 20.9% | 48.8% | 18.6% | |||

| Change | 0.0% | 5.0% | –14.6% | –2.3% | 11.9% | 0.210 | 0.170 | |

| Usefulness | 2 months | 0.0% | 5.6% | 55.6% | 27.8% | 11.1% | ||

| 12 months | 0.0% | 31.5% | 29.6% | 29.6% | 9.3% | |||

| Change | 0.0% | 25.9% | –25.9% | 1.9% | –1.9% | –0.228 | 0.143 | |

| Daily Practice | 2 months | 9.5% | 6.3% | 20.6% | 49.2% | 14.3% | ||

| 12 months | 14.1% | 20.3% | 12.5% | 42.2% | 10.9% | |||

| Change | 4.5% | 14.0% | –8.1% | –7.0% | –3.3% | –0.195 | 0.123 | |

| Practice Planning | 2 months | 0.0% | 8.3% | 41.7% | 37.5% | 12.5% | ||

| 12 months | 0.0% | 15.5% | 26.8% | 42.3% | 15.5% | |||

| Change | 0.0% | 7.2% | –14.9% | 4.8% | 3.0% | 0.062 | 0.123 | |

| CDMS | 2 months | 0.0% | 0.0% | 30.2% | 56.7% | 13.1% | ||

| 12 months | 0.5% | 5.4% | 17.6% | 42.8% | 33.8% | |||

| Change | 0.5% | 5.4% | –12.6% | –13.9% | 20.7% | 0.280 | 0.070 | |

| Support from the Service Provider | 2 months | 0.0% | 0.0% | 17.1% | 40.0% | 42.9% | ||

| 12 months | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 71.4% | 28.6% | |||

| Change | 0.0% | 1.8% | –7.9% | 5.4% | –20.0% | –0.172 | 0.208 | |

| Satisfaction | 2 months | 0.0% | 0.0% | 36.1% | 54.1% | 9.8% | ||

| 12 months | 0.0% | 6.9% | 34.5% | 32.8% | 25.9% | |||

| Change | 0.0% | 6.9% | –1.6% | –21.3% | 16.0% | 0.052 | 0.146 | |

Abbreviation: CDMS, chronic disease management system.

The population analyzed includes only those sites that completed both baseline and end-of-study questionnaires.

For the 9 health care providers who completed both the 2-month and the 12-month questionnaires, the differences between baseline and end-of-study responses were evaluated for change (Table 6). A negative gamma coefficient indicates a movement toward the negative questions, and a positive gamma coefficient indicates a movement toward the positive questions. The magnitude of the gamma coefficient ranges from –1 to +1, similar to the Pearson correlation of nominal data, with 0.0 to 0.2 indicating “Very weak to negligible correlation” and 0.2 to 0.4 indicating “Weak or low correlation.” Of the 9 domains, 3 had weak correlation from Month 2 to Month 12, while the other 6 had negligible gamma correlation. Weak negative gamma shifts were present for Usefulness, while weak positive gamma shifts were present for Using and CDMS. Negligible negative shifts occurred for Training, Daily Practice, and Support from the Service Provider; negligible positive shifts occurred for Learning, Practice Planning, and Satisfaction.

Post Hoc Analysis

Due to the lack of observed change in the outcome variables during the study period, it was decided to explore a number of factors that might help explain this result. An unexpectedly low rate of CDMS use across sites was found and could be an important factor in explaining the lack of improvement in diabetes management.

Overall CDMS Use

The 9 study sites were enrolled for an average of 11 months (minimum, 8; maximum, 12). Table 7 shows the total number of views of each CDMS screen over the study period, as well as the mean views per month. The Patient/Care Status page was viewed most often, and made up 72% of usage.

Table 7: Mean Number of Views and CDMS Entries per Month.

| CDMS Screen | Total Views, n | Mean Views/Month, n | Minimum, n | Maximum, n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Dashboard | 493 | 45 | 4 | 165 |

| Registry/Registry Status | 5,889 | 541 | 45 | 3,023 |

| Patient/Care Status | 16,498 | 1,515 | 32 | 6,725 |

| Manual entries | 4,031 | 370 | 0 | 2,709 |

Abbreviation: CDMS, chronic disease management system.

CDMS Use by Site

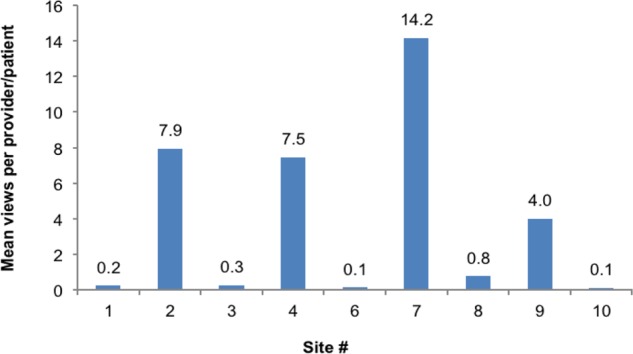

To get a sense of the level of use by site and by health care provider within each site, it was determined that views of the Patient/Care Status screen would be a good indication of P-PROMPT use for the treatment and management of patients with diabetes (although it could also indicate use for updating documentation other than at the point and time of care). Three of the 9 sites (2, 7, and 8) appeared to have used the CDMS the most during the study period (Table 8). Sites 1 and 6 appeared not to have used the CDMS at all.

Table 8: Use of the CDMS by Sitea.

| Site # | Total Views | Number of Providers | Mean Views/Provider | Mean Views/Provider/Monthb | Number of Patients | Mean Views/Patient | Mean Views/Patient/Month |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 32 | 1 | 32 | 3 | 186 | 0.2 | 0.01 |

| 2 | 6,002 | 3 | 2,001 | 167 | 381 | 15.8 | 1.31 |

| 3 | 1,281 | 5 | 256 | 21 | 424 | 3.0 | 0.25 |

| 4 | 1,057 | 14 | 76 | 6 | 248 | 4.3 | 0.36 |

| 6 | 158 | 8 | 20 | 2 | 675 | 0.2 | 0.02 |

| 7 | 607 | 1 | 607 | 76 | 23 | 26.4 | 3.30 |

| 8 | 6,725 | 2 | 3,363 | 280 | 208 | 32.3 | 2.69 |

| 9 | 353 | 2 | 177 | 22 | 67 | 5.3 | 0.66 |

| 10 | 283 | 1 | 283 | 28 | 108 | 2.6 | 0.26 |

Abbreviation: CDMS, chronic disease management system.

Site 5 withdrew prior to completion of the study.

Sites 7, 9, and 10 data were based on 9, 9, and 10 months of follow-up, respectively. Data for the other sites were based on 12 months of follow-up.

Figure 2 shows the mean number of views of the Patient Care Status screen per health care provider per patient over the course of the study. The most engaged site (site 7) logged into the system about 14 times per patient per year (1.2 times per month). Healthcare providers at two other sites (sites 2 and 4) appeared to use the tool frequently as well, logging into the system to view patient status about 8 times per patient per year.

Figure 2: Mean Number of Views of the Patient/Care Status Screen per Provider per Patienta.

Site 5 withdrew prior to completion of the study.

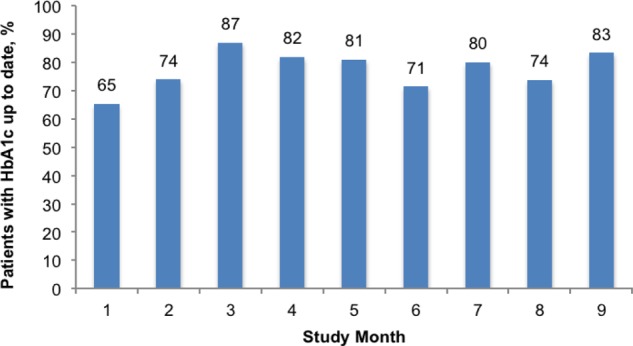

For the site that used the CDMS most frequently (site 7), the percentage of diabetes patients with HbA1c values up to date was 65% at the beginning of the study and increased to 83% by the end of the study (Figure 3). The proportion of patients at this site with blood pressure and cholesterol values up to date at the end of the study also increased, by 15% and 0.2%, respectively.

Figure 3: Proportion of Patients With HbA1c Up to Date at a Site That Used the CDMS Frequently (Site 7).

Abbreviation: CDMS, chronic disease management system; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c.

Discussion

Application of health informatics–based technologies holds great promise for positively influencing diabetes care. In Ontario, a recent before-and-after study of the routine use of CDMS in ambulatory diabetes patient care by Ontario diabetes specialists showed significant improvements in the quality of patient care as measured by the completeness of documented care delivered. (14) Information technology provides a means for the rapid and easy dissemination of information to patients and health care providers, and it improves communication between them as well. (15)

This community-based, real-world evaluation of a web-based CDMS for the treatment and management of diabetes failed to impact physician practice due to limited engagement and use of the system in the majority of practices. However, it was intriguing to note that at the site that used the CDMS to a meaningful extent, substantial improvement in patient care was observed. It was also instructive to note that in the responses to the questionnaire, most participants indicated that they used the system rarely or not at all during patient visits, but also indicated that they would like to learn more about the CDMS and wanted more training. This suggests that clinicians may not be averse to using health informatics–based CDMS technology, but will not use it if they are only given the tool and not given additional in-depth training and follow-up.

A few items were identified that may have negatively impacted the successful implementation of the CDMS: not all laboratories provide electronic data feed; there was significant heterogeneity across the sites with respect to data systems and flow of information; and some of the data needed to be entered into the CDMS manually (e.g., foot examination and blood pressure). A thorough analysis of factors that led to limited commitment to the CDMS would be very helpful. For example, Green et al (2006) (16) evaluated the successful implementation of web-based CDMS for diabetes care in Victoria, British Columbia, using a critical success factor analysis. The authors found that in addition to features of effective clinical decision support systems (e.g., automatic provision of decision support as part of clinician workflow), an array of systemic factors were also necessary for success (e.g., project management from clinical, project and information technology; health delivery system readiness for reform).

In addition to evaluating the efficacy, effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness of information technology aimed at improving patient outcomes with diabetes, it would be beneficial for decision makers to attempt to identify the determinants of implementation success prior to investing in the technology.

Conclusions

This community-based, real-world evaluation of a web-based CDMS for the treatment and management of diabetes failed to impact physician practice due to limited engagement and use of this system in the majority of practices. Simply giving health care providers a potentially useful technology will not ensure its use. Organizational readiness and implementation strategies should be developed prior to introducing a CDMS.

Acknowledgements

Editorial Staff

Jeanne McKane, CPE, ELS(D)

The authors would like to thank the physicians and staff at each of the practice sites for their participation in the study and for their efforts and opinions regarding data collection and evaluation of the chronic disease management system. We would also like to thank Dr. Les Levin and the Evidence Development and Standards Team (formerly the Medical Advisory Secretariat), Health Quality Ontario, and the Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee for their comments and their support of this study.

Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care funding was acquired through an independent Health Technology Assessment and Economic Evaluation Program research grant awarded to Professor Ron Goeree and the research team (Grant 06129) at the Programs for Assessment of Technology in Health (PATH) Research Institute, St. Joseph’s Healthcare, Hamilton, and dedicated study was funding awarded to Dr. Daria O’Reilly for this study. Dr. O’Reilly was the recipient of a Career Scientist Award from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care during this study.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Site Team Follow-up Questionnaire

Challenging the Ontario Diabetes Care Quality Gap: Evaluation and Long-Term Cost-Utility Analysis of Using a Chronic Disease Management System (CDMS) in Primary Health Care Practices in Ontario (ODIAC-CDMS)

Site Team Follow-up Questionnaire

Study ID#:___________ Date (DD/MMM/YY): ___________________

Follow-up: □ 2 month □ 6 month □ 12 month

Your Current Role

| □ | Physician | □ | Nurse practitioner | □ | Nurse | □ | Dietician |

| □ | Physiotherapist | □ | Occupational therapist | □ | Respiratory therapist | ||

| □ | Chiropodist | □ | Optometrist | □ | Administrative | □ | Clerical/billing |

| □ | Pharmacist | □ | Other___________________________ | ||||

For each of the for the following questions regarding the P-PROMPT Chronic Disease Management System (CDMS), check 1 response that corresponds most closely to your desired answer for the following statements (the term “it” in the questions below refers to the P-PROMPT Chronic Disease Management System).

| Completely Disagree | Somewhat Disagree | Slightly Agree | Mostly Agree | Completely Agree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Learning | |||||

| 1. I quickly learn new skills to use it | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 2. I easily remember my new skills to use it | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 3. It provides the ease of learning I need | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 4. It would be easy for me to become better skilled at using it | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 5. I am confident that I can learn new parts of it | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 6. I would like to learn more about how to use it | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 7. I am proficient in using it | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Training | |||||

| 8. I am satisfied with the training I received | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 9. It is easy for me to train someone to use it | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 10. It is easy for me to receive training from co-workers on how to use it | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 11. Supplemental reference material was easy to follow | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Using | |||||

| 12. I find it easy to use | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 13. I can use it without written instructions | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 14. I recover from mistakes quickly and easily | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 15. I can use it successfully every time | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 16. Performing tasks is straightforward | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Usefulness | |||||

| 17. It helps my performance in my role | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 18. It helps me be more productive in my role | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 19. It helps me be more effective in my role | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 20. It provides useful information to do my job well | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 21. It provides more control over my work daily activities | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 22. It does everything I would expect it to do | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Daily Practice | |||||

| 23. I use it during patient visits | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 24. It helps me to increase patient education content regarding their diabetes | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 25. It helps me to quickly overview the patient’s diabetes status | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 26. It helps me to quickly overview the patient’s diabetes trends | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 27. It is easy to check patient data | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 28. It assists in determining what tests and/or procedures are overdue for diabetic patients | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 29. It improves the quality of time with the patient | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 30. I am confident that it protects patient data confidentiality | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Practice Planning | |||||

| 31. It assists in setting practice goals | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 32. It assists in achieving practice goals | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 33. It helps me to quickly overview the practice status | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 34. It helps me to quickly overview my practice improvements over time | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 35. It provides sufficient information to evaluate my overall performance in diabetes care management | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 36. It represents patient-centered care | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 37. It allows team members to work at an enhanced professional level | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 38. It will assist the practice with obtaining incentive fees | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 39. It assists with preparing the monthly reports | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| CDMS | |||||

| 40. It is easy to read the characters on the screens | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 41. Highlighting simplifies what I should focus on as important information | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 42. Organization of display screens is easy to follow | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 43. Arrangement of screens is simple to follow | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 44. It provides a user-friendly interface | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 45. Program pop-up messages are easy to understand | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 46. The output options (e.g., print chart notes, print patient list, transfer to EMR) are sufficient for my use | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 47. Automated data input function (e.g., incentive code billings, laboratory data) are sufficient for my use | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 48. System speed is fast enough | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 49. It is reliable | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 50. Correcting mistakes is easy | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 51. It is easy to display the current status of a single patient | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 52. It is easy to update a single element of a patient’s record | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 53. It is easy to update multiple elements of a patient’s record | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 54. It is easy to display patient summary dashboards | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 55. It is easy to add (roster) a new patient | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 56. It is easy to remove (de-roster) a new patient | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 57. It is easy to display a patient’s history of a single care element | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 58. It is easy to display a list of patients in a registry | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 59. It is easy to create registry list(s) and action/recall lists for printout | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 60. It is easy to update the care element status list(s) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 61. It is easy to display practice registry summary dashboards | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 62. It is easy to display registry summary statistics | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 63. It is easy to edit care/tracking plans of patient(s) in a registry | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 64. It is easy to display a list of all patients in MD roster | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 65. It is easy to display a list of available registries with editable MJD activations and default care/tracking plans | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 66. It is easy to display lists of patients who have invalid data, with editable data | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 67. I am satisfied with the way the information is organized | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Support from the Service Provider | |||||

| 68. I am always treated courteously and in a professional manner by the service provider | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 69. The technical support provided by the service provider is helpful to resolves my problems | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 70. The service provider resolve my questions within a reasonable time | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 71. Additional training is available when I ask for it | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Satisfaction | |||||

| 72. It provides the precise information I need to manage patients more effectively | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 73. It is fun to use | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 74. I would recommend it to others | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 75. It works the way I want it to work | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 76. I would like to continue to use it in my daily practice | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 77. It is designed for all level of computer users | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 78. Overall, I am satisfied with it | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Comments | |||||

Appendix 2: Patient Dashboard View

Appendix 3: Registry/Registry Status View

Appendix 4: Patient/Care Status (Dynaflow sheet)

Suggested Citation

This report should be cited as follows:

O’Reilly DJ, Bowen JM, Sebaldt RJ, Petrie A, Hopkins RB, Assasi N, MacDougald C, Nunes E, Goeree R. Evaluation of a chronic disease management system for the treatment and management of diabetes in primary health care practices in Ontario: an observational study. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser [Internet]. 2014 April;14(3):1–37. Available from: http://www.hqontario.ca/evidence/publications-and-ohtac-recommendations/ontario-health-technology-assessment-series/cdms-diabetes.

Permission Requests

All inquiries regarding permission to reproduce any content in the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series should be directed to EvidenceInfo@hqontario.ca.

How to Obtain Issues in the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series

All authors in the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series are freely available in PDF format at the following URL: http://www.hqontario.ca/evidence/publications-and-ohtac-recommendations/ontario-health-technology-assessment-series.

Conflict of Interest Statement

All reports in the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series are impartial. There are no competing interests or conflicts of interest to declare.

Indexing

The Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series is currently indexed in MEDLINE/PubMed, Excerpta Medica/Embase, and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination database.

Peer Review

All reports in the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series are subject to external expert peer review. Additionally, Health Quality Ontario posts draft reports and recommendations on its website for public comment prior to publication. For more information, please visit: http://www.hqontario.ca/en/mas/ohtac_public_engage_overview.html.

About Health Quality Ontario

Health Quality Ontario is an arms-length agency of the Ontario government. It is a partner and leader in transforming Ontario’s health care system so that it can deliver a better experience of care, better outcomes for Ontarians, and better value for money.

Health Quality Ontario strives to promote health care that is supported by the best available scientific evidence. The Evidence Development and Standards branch works with expert advisory panels, clinical experts, scientific collaborators, and field evaluation partners to conduct evidence-based reviews that evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of health interventions in Ontario.

Based on the evidence provided by Evidence Development and Standards and its partners, the Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee—a standing advisory subcommittee of the Health Quality Ontario Board—makes recommendations about the uptake, diffusion, distribution, or removal of health interventions to Ontario’s Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, clinicians, health system leaders, and policy-makers.

Health Quality Ontario’s research is published as part of the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series, which is indexed in MEDLINE/PubMed, Excerpta Medica/Embase, and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination database. Corresponding Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee recommendations and other associated reports are also published on the Health Quality Ontario website. Visit http://www.hqontario.ca for more information.

About the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series

To conduct its comprehensive analyses, Evidence Development and Standards and its research partners review the available scientific literature, making every effort to consider all relevant national and international research; collaborate with partners across relevant government branches; consult with expert advisory panels, clinical and other external experts, and developers of health technologies; and solicit any necessary supplemental information.

In addition, Evidence Development and Standards collects and analyzes information about how a health intervention fits within current practice and existing treatment alternatives. Details about the diffusion of the intervention into current health care practices in Ontario add an important dimension to the review.

The Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee uses a unique decision determinants framework when making recommendations to the Health Quality Ontario Board. The framework takes into account clinical benefits, value for money, societal and ethical considerations, and the economic feasibility of the health care intervention in Ontario. Draft Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee recommendations and evidence-based reviews are posted for 21 days on the Health Quality Ontario website, giving individuals and organizations an opportunity to provide comments prior to publication. For more information, please visit: http://www.hqontario.ca/evidence/evidence-process/evidence-review-process/professional-and-public-engagement-and-consultation.

Disclaimer

This report was prepared by the Evidence Development and Standards branch at Health Quality Ontario or one of its research partners for the Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee and was developed from analysis, interpretation, and comparison of scientific research. It also incorporates, when available, Ontario data and information provided by experts and applicants to HQO. The analysis may not have captured every relevant publication and relevant scientific findings may have been reported since the development of this recommendation. This report may be superseded by an updated publication on the same topic. Please check the Health Quality Ontario website for a list of all publications: http://www.hqontario.ca/evidence/publications-and-ohtac-recommendations.

Health Quality Ontario

130 Bloor Street West, 10th Floor

Toronto, Ontario

M5S 1N5

Tel: 416-323-6868

Toll Free: 1-866-623-6868

Fax: 416-323-9261

Email: EvidenceInfo@hqontario.ca

ISSN 1915-7398 (online)

ISBN 978-1-4606-3034-1 (PDF)

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2014

List of Tables

| Table 1: Baseline Characteristics of Enrolled Sites |

| Table 2: Study Participation by Specialty |

| Table 3: Change in Clinical Values From Baseline to End of Study |

| Table 4: Care and Treatment Elements (N = 2,320) |

| Table 5: Evaluation of the CDMS: Baseline Site Questionnaire (N = 21)a |

| Table 6: Evaluation of the CDMS: Change From Baseline to End of Study (N = 9)a |

| Table 7: Mean Number of Views and CDMS Entries per Month |

| Table 8: Use of the CDMS by Sitea |

List of Figures

List of Abbreviations

- ACE

Angiotensin-converting enzyme

- ARB

Angiotensin II receptor blocker

- CDMS

Chronic disease management system

- CPG

Clinical practice guideline

- HDL-C

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HbA1c

Hemoglobin A1c

- LDL-C

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- P-PROMPT

Provider and Patient Reminders in Ontario: Multi-Strategy Prevention Tools

- PATH

Programs for Assessment of Technology in Health

Footnotes

Presented to the Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee on March 22, 2013.

Final report submitted to Health Quality Ontario March 2013.

References

- 1.Canadian Diabetes Association Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee. Canadian Diabetes Association 2008 clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of diabetes in Canada. Can J Diabetes. 2008;32(suppl 1):S1–S201. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Public Health Agency of Canada. Diabetes in Canada: facts and figures from a public health perspective. Ottawa (ON): PHAC. 2011. p. 123 p..

- 3.Canadian Diabetes Association Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee. Canadian Diabetes Association 2013 clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of diabetes in Canada. Can J Diabetes. 2013;37(suppl 1):S1–S212. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Health coverage: helpful options for people with diabetes. Toronto: MOHLTC; 2009. [[cited 2014 March 6]. 4 p.]. [Internet]. Available from: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/public/programs/diabetes/docs/diabetes_factsheets/English/Covera ge_21july09.pdf .

- 5.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Diabetes care gaps and disparities in Canada. Ottawa (ON): CIHI. 2009. p. 21 p..

- 6.Sanmartin C, Gilmore J. Diabetes—prevalence and care practices. Health Rep. 2008;19(3):59–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris SB, Worrall G, Macauley A, et al. Diabetes management in Canada: baseline results of the Group Practice Diabetes Management Study. Can J Diabetes. 2006;30(2):131–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shojania KG, Ranji SR, McDonald KM, Grimshaw JM, Sundaram V, Rushakoff RJ, et al. Effects of quality improvement strategies for type 2 diabetes on glycemic control: a meta-regression analysis. JAMA. 2006;296(4):427–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA. 2002;288(14):1775–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Eff Clin Pract. 1998;1(1):2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sebaldt RJ, Kaczorowski J, Burgess K, Donald F, Goeree R, Lohfeld L. P-PROMPT: provider & patient reminders: multi-strategy prevention tools. American Medical Informatics Association Symposium. Chicago (IL). Bethesda (MD): AMIA; 2007. 1198 p. 2007. Nov, pp. 10–14.

- 12.Ontario Health Quality Council. 2008 report on Ontario’s health system. Toronto: OHQC. 2008. [[cited 2014 Mar 6]. 109 p.]. [Internet]. Available from: http://www.hqontario.ca/portals/0/Documents/pr/qmonitor-full-report-2008-en.pdf .

- 13.Fleming M. Ontario patient rostering. Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement: Picking Up the Pace. Montreal (QC) Ottawa (ON): CFHI; 2010. 2010. Nov, pp. 1–2.

- 14.Roshanov PS, Gerstein HC, Hunt DL, Sebaldt RJ, Haynes RB. Impact of a computerized system for evidence-based diabetes care on completeness of records: a before-after study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:63. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-12-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson CL, Bolen S, Brancati FL, Batts-Turner ML, Gary TL. A systematic review of interactive computer-assisted technology in diabetes care. Interactive information technology in diabetes care. J Gen Intern Med. 2006 Feb;21(2):105–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00310.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Green CJ, Fortin P, Maclure M, Macgregor A, Robinson S. Information system support as a critical success factor for chronic disease management: necessary but not sufficient. Int J Med Inform. 2006 Dec;75(12):818–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2006.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]