Abstract

Background and Purpose

Medical and endovascular treatment options for stroke prevention in patients with symptomatic intracranial stenosis have evolved over the past several decades, but the impact of 2 major multi-center randomized stroke prevention trials on physician practices has not been studied. We sought to determine changes in US physician treatment choices for patients with intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis (ICAS) following 2 NIH-funded clinical trials that studied medical therapies (antithrombotic agents and risk factor control) and percutaneous transluminal angioplasty and stenting (PTAS).

Methods

Anonymous surveys on treatment practices in patients with ICAS were sent to physicians at 3 time points: before publication of the NIH-funded Warfarin-Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease (WASID) Trial (pre-WASID, 2004); 1 year after WASID publication (post-WASID, 2006); and 1 year after the publication of the NIH-funded Stenting and Aggressive Medical Management for Preventing Recurrent stroke in Intracranial Stenosis (SAMMPRIS) Trial (post-SAMMPRIS, 2012). Neurologists were invited to participate in the pre-WASID survey (n=525). Neurologist and Neurointerventionists were invited to participate in the post-WASID (n=598) and post-SAMMPRIS (n= 2080) survey. The 3 surveys were conducted using web-based survey tools delivered by email, and a fax-based response form delivered by email and conventional mail. Data were analyzed using the chi-square test.

Results

Pre-WASID, there was equipoise between warfarin and aspirin for stroke prevention in patients with ICAS. The number of respondents who recommended antiplatelet treatment for ICAS increased across all 3 surveys for both anterior circulation (pre-WASID=44%, post-WASID=85%, post-SAMMPRIS=94%) and posterior circulation (pre-WASID=36%, post-WASID=74%, post-SAMMPRIS=83%). The antiplatelet agent most commonly recommended post-WASID was aspirin, but post-SAMMPRIS it was the combination of aspirin and clopidogrel. The percentage of neurologists who recommended PTAS in > 25% of ICAS patients increased slightly from pre-WASID (8%) to post-WASID (12%), but then decreased again post-SAMMPRIS (6%). The percentage of neurointerventionists who recommended PTAS in > 25% of ICAS patients decreased from post-WASID (49%) to post-SAMMPRIS (17%).

Conclusions

The surveyed US physicians’ recommended treatments for ICAS differed over the 3 survey periods, reflecting the results of the 2 NIH-funded clinical trials of ICAS and suggesting that these clinical trials changed practice in the US.

Keywords: Intracranial stenosis, Survey, Cerebral arteries, Treatment practices

INTRODUCTION

Intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis (ICAS) causes 8-10% of ischemic strokes in the US1 and is one of the most common causes of stroke worldwide2. Despite the high prevalence and high risk of recurrent stroke associated with ICAS, optimal treatment for this disease is still evolving. Over a decade ago, physician preferences regarding antithrombotic and endovascular treatment of ICAS were largely based on retrospective studies3 and expert opinion4, but since then, two large randomized trials have compared treatment strategies for this disease. First, the Warfarin Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease (WASID) trial compared aspirin vs. warfarin among patients with symptomatic 50-99% intracranial stenosis and found that aspirin was safer and as effective as warfarin for prevention of stroke and vascular death in patients with ICAS5. More recently, the Stenting and Aggressive Medical Management for Prevention of Recurrent stroke in Intracranial Stenosis (SAMMPRIS) trial compared aggressive medical management vs. aggressive medical management plus percutaneous transluminal angioplasty and stenting (PTAS) among patients with symptomatic 70-99% stenosis and found a high rate of periprocedural stroke after PTAS and a lower than expected rate of stroke on aggressive medical therapy6. The impact of these large randomized trials on clinical practice has not been quantified. Therefore, we sought to determine the impact of the results of these studies on treatment choices of US physicians managing patients with ICAS by surveying physicians before and after the publications of WASID and SAMMPRIS.

METHODS

Anonymous surveys of physician treatment choices were conducted at the following times: 1. Pre-WASID: prior to publication of WASID results (2004), 2. Post-WASID: 1 year after publication of the WASID results (2006), and 3. Post-SAMMPRIS: approximately 1 year after publication of the SAMMPRIS trial results (2012).

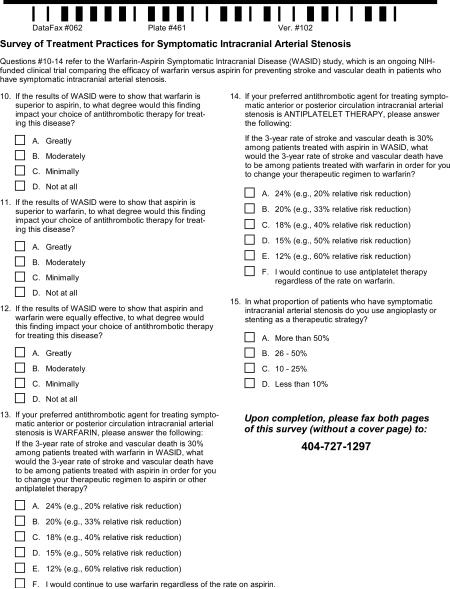

Pre-WASID Survey

The pre-WASID survey was conducted using a written questionnaire, sent by email or conventional mail (if no email). The survey was sent to neurologists and included WASID investigators (n=90) and American Academy of Neurology (AAN) Stroke Section members (n=435) and it was available for 8 weeks. One reminder was sent. Completed questionnaires were faxed to the WASID Datafax server. The survey included 15 multiple choice questions (Appendix A) on the following topics: physician's practice setting, experience treating stroke, preferred antithrombotic agent for ICAS, willingness to change practice based on the WASID results, current use of PTAS for ICAS.

Post-WASID Survey

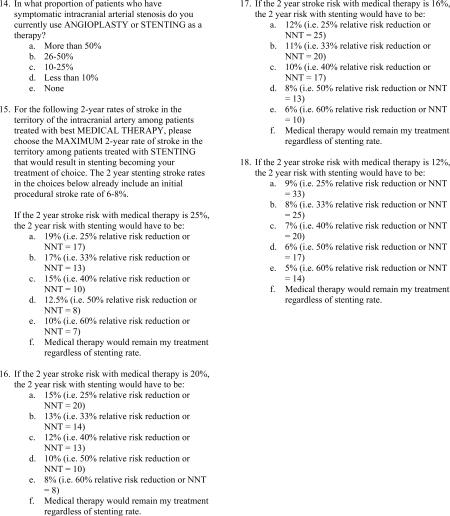

The post-WASID survey was administered using an internet-based survey tool (www.questionpro.com). The survey was sent to neurologists, including WASID investigators and AAN Stroke Section members with available email addresses (n=233), and neurointerventionists who were American Society of Interventional & Therapeutic Neuroradiology (ASITN) members with available email addresses (n=365) and it was available for 8 weeks. Not all email addresses were valid, but attempts were made to ascertain the correct contact information and remove duplicates. Email notification of the request to complete the survey and a link to the survey were sent and one reminder email was sent.

The post-WASID survey included multiple choice questions (Appendix B) on the same topics as the pre-WASID survey, but also included questions that asked respondents to choose the maximum 2-year rate of stroke in the territory of the symptomatic intracranial artery among patients treated with PTAS that would result in PTAS becoming their treatment of choice for the following 2-year stroke rates on medical therapy: 25%, 20%, 16%, and 12%. The response options reflected a 25%, 33%, 40%, 50%, and 60% relative risk reduction (RRR) from PTAS or “medical therapy would remain my treatment regardless of stenting rate”.

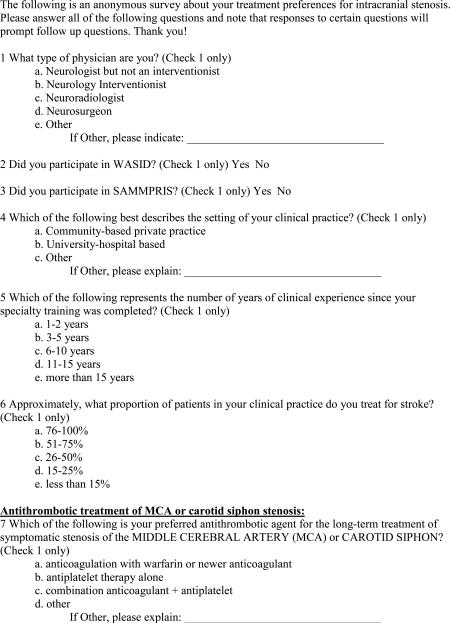

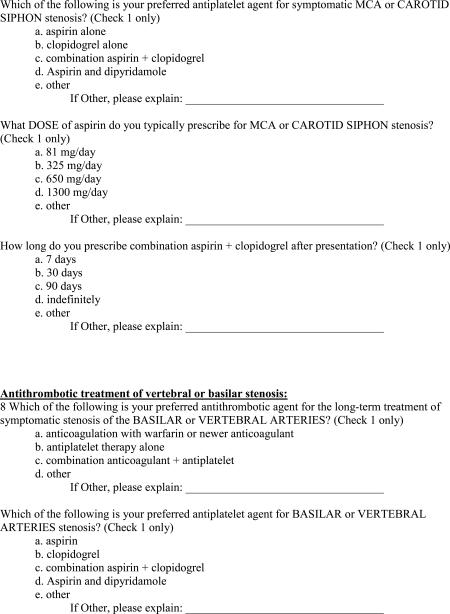

Post-SAMMPRIS Survey

The post-SAMMPRIS survey was administered using the internet-based Research and Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) survey tool7. The survey was sent to neurologists from previous email lists and AAN Stroke Section members with available email addresses (n=1400) and neurointerventionists from previous survey email lists and members of the Society of Vascular Interventional Neurologist (SVIN) and Society of Neurointerventional Surgeons (SNIS) (n=680) and it was available for one month. Attempts were made to ascertain the correct contact information and remove duplicate emails. Email notification of the request to complete the survey and a link to the survey were sent and one reminder email was sent.

The post-SAMMPRIS survey included multiple choice questions (Appendix C) on the topics of the prior surveys, but also included questions about the definition of “failure of medical therapy”, factors that influence treatment with PTAS, and the impact of SAMMPRIS on practice. Three questions asked respondents to choose the maximum 1-year rate of stroke in the territory of the symptomatic intracranial artery among patients treated with a “new endovascular procedure” that would result in that procedure becoming their treatment of choice for the following 1-year stroke rates on aggressive medical therapy: 25%, 20%, and 16%. The response options reflected a 25%, 33%, 40%, 50%, and 60% RRR from the “new endovascular procedure” or “aggressive medical therapy would remain my treatment regardless”.

Statistical Analysis

Responses were characterized by standard descriptive statistics (i.e. percentages). Survey questions required categorical responses, with limited fields for ‘other’ answers. All comparisons between groups were done using Chi-square analysis.

RESULTS

The overall response rates for the surveys were: pre-WASID, 34% (181/525); post-WASID, 33% (199/598), and post-SAMMPRIS, 15% (302/2080). While the target groups were similar between the surveys, the number of respondents who completed more than one of the surveys is unknown due to anonymity. As shown in Table 1, in all surveys, the majority of respondents had University-based practices, were in practice 10 years or more, and at least 25% of their practice involved treating stroke patients. Respondents differed significantly in practice type and years in practice since training, with more University-based respondents in the post-WASID survey.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the survey respondents

| Pre-WASID n=181 | Post-WASID n=199 | Post-SAMMPRIS n=302 | p-value* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Total | Total | ||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |||

| type of practice | ||||||||

| community | 43 | 25% | 37 | 19% | 82 | 27% | 0.0431 | |

| university hospital | 108 | 64% | 145 | 76% | 195 | 65% | ||

| other | 18 | 11% | 9 | 5% | 23 | 8% | ||

| years clinical experience since training | ||||||||

| 1-2 | 1 | 1% | 5 | 3% | 35 | 12% | <0.001 | |

| 3-5 | 22 | 13% | 16 | 8% | 48 | 16% | ||

| 6-10 | 35 | 21% | 62 | 32% | 31 | 10% | ||

| 11-15** | 111 | 66% | 30 | 16% | 50 | 17% | ||

| > 15** | - | 0% | 78 | 41% | 137 | 50% | ||

| Proportion of patients in clinical practice treated for stroke | ||||||||

| 76-100% | 45 | 26% | 60 | 31% | 90 | 30% | 0.3623 | |

| 51-75% | 39 | 23% | 49 | 26% | 70 | 23% | ||

| 26-50% | 39 | 23% | 33 | 17% | 58 | 19% | ||

| 15-25% | 37 | 22% | 27 | 14% | 54 | 18% | ||

| < 15% | 10 | 6% | 22 | 12% | 28 | 9% | ||

| Participation in clinical trial | ||||||||

| WASID (yes) | 55 | 30% | 70 | 35% | 65 | 22% | 0.0026 | |

| SAMMPRIS (yes) | - | - | - | - | 110 | 36% | ||

Chi-square p-value comparing characteristics across the 3 surveys

the Pre-WASID categories were 1-2, 3-5, 6-10, and >10 years.

Medical Management

Willingness to change practice

In the pre-WASID survey, the majority of neurologists (91%) indicated that if the 3-year stroke and vascular death rate was 30% on their preferred antithrombotic treatment, they would require a 20-33% RRR from the more effective antithrombotic agent to switch from their preferred agent, whether their preferred agent was warfarin or aspirin. Only 3.6% would continue to use warfarin and 1.4% would continue to use aspirin regardless of the WASID results.

Choice of antithrombotic medication

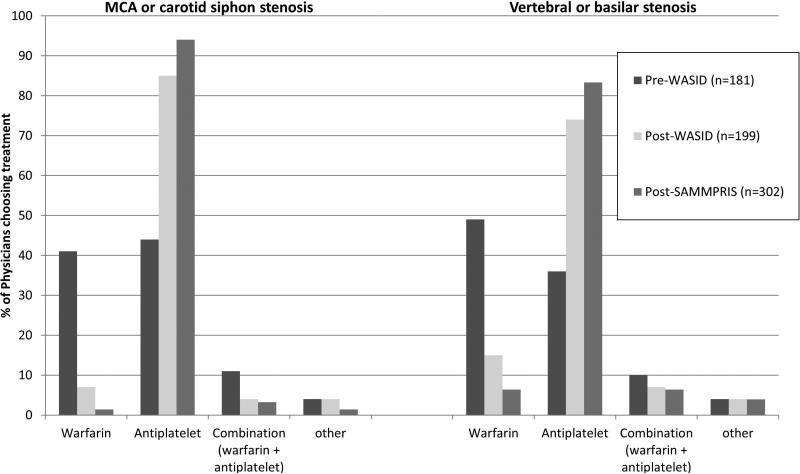

The neurologists’ preferred antithrombotic agent differed significantly between pre-WASID and post-WASID surveys for the treatment of both anterior circulation (p<0.001) and posterior circulation (p<0.001) stenoses. As shown in Figure 1, the pre-WASID neurologists’ preferred antithrombotic treatment was equally divided between warfarin and antiplatelet agents for anterior circulation stenosis, but more neurologists preferred warfarin for posterior circulation stenosis. Compared to the post-WASID respondents, more post-SAMMPRIS respondents preferred antiplatelet agents for stenosis in the anterior circulation (85% vs. 94%, p=0.0017) and posterior circulation (74% vs. 83%, p=0.0145).

Figure 1.

Antithrombotic medication treatment preferences for symptomatic intracranial stenosis is 3 surveys

Choice of antiplatelet agent

As shown in Table 2, the antiplatelet treatment most commonly preferred for ICAS post-WASID was aspirin (44% for anterior circulation, 43% for posterior circulation), whereas post-SAMMPRIS it was the combination of aspirin and clopidogrel (45% for anterior circulation, 43% for posterior circulation). The preferred dose of aspirin was 325 mg/day in both the post-WASID and post-SAMMPRIS surveys. The dose of aspirin used in WASID (1300 mg/day) was preferred by only 11% of post-WASID respondents and virtually no post-SAMMPRIS respondents. In the post-SAMMPRIS survey, the combination of aspirin and clopidogrel (which was used for 90 days after enrollment in SAMMPRIS) was recommended for 30 days, 90 days, and indefinitely by 5%, 45%, and 44% of respondents, respectively.

Table 2.

Post-WASID vs. Post-SAMMPRIS respondents preferred antiplatelet agent regimen

| MCA or carotid siphon stenosis | Vertebral or basilar stenosis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-WASID | Post-SAMMPRIS | Post-WASID | Post-SAMMPRIS | |

| Which of the following is your preferred antiplatelet agent? | ||||

| Aspirin | 75 (44%) | 93 (34%) | 66 (43%) | 95 (38%) |

| Clopidogrel (Plavix) | 25 (15%) | 34 (12%) | 24 (16%) | 32 (13%) |

| Aspirin and Clopidogrel* | 43 (25%) | 124 (45%) | 39 (25%) | 110 (43%) |

| Aspirin and Dipyridamole (Aggrenox) | 26 (15%) | 19 (7%) | 25 (16%) | 14 (6%) |

| Other | 1 (1%) | 4 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (1%) |

| p<0.0001 | p<0.0001 | |||

| What dose of aspirin do you typically prescribe? | ||||

| 81 mg/day | 21 (21%) | 93 (43%) | 17 (19%) | 81 (40%) |

| 325 mg/day | 64 (65%) | 118 (54%) | 58 (66%) | 118 (58%) |

| 650 mg/day | 2 (2%) | 1 (<1%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (<1%) |

| 1300 mg/day | 11 (11%) | 1 (<1%) | 10 (11%) | 1 (<1%) |

| Other | 1 (1%) | 4 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 4 (2%) |

| p<0.0001 | p<0.0001 | |||

In the Post-WASID survey, the selection choice was “Combination antiplatelet” and the most common combination selected was aspirin and clopidogrel. In the Post-SAMMPRIS survey, the choice was “Combination aspirin + clopidogrel”.

Definition and treatment of patients on “maximal medical therapy”

In the post-SAMMPRIS survey, the majority of respondents (61%) considered “maximal medical therapy” to include both “use of antithrombotic treatment” and “use of aggressive medical therapy to manage risk factors and achievement of SBP<140 and LDL<70”, which were the risk factor targets in SAMMPRIS8. Only 4% of respondents considered “maximal medical therapy” to include only “use of antithrombotic treatment”. For treatment recommendations in patients with symptomatic intracranial stenosis who have “failed medical therapy”, 50% of respondents reported that they “assess for compliance and/or intensity medical therapy”, whereas 45% “recommend treatment with angioplasty or stenting”.

Endovascular treatment

Neurologist PTAS recommendations

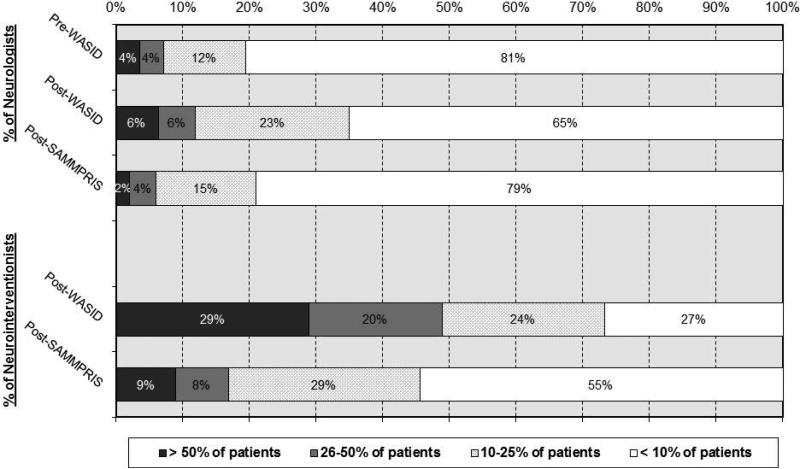

The proportion of patients for whom the neurologists recommended PTAS significantly increased from the pre-WASID to the post-WASID survey (p<0.0001) and then decreased in the post-SAMMPRIS survey (p=0.0135) to approximately pre-WASID levels, as shown in Figure 2. The majority of neurologists recommended PTAS in less than 10% of their ICAS patients in all surveys.

Figure 2.

Percentage of respondents who recommend angioplasty and stenting for a given proportion of patients with ICAS

Neurointerventionist PTAS recommendations

In the post-WASID survey, about half of neurointerventionists (51%) reported that they recommended PTAS in 25% or less of their patients with ICAS, but in the post-SAMMPRIS survey 84% recommended PTAS in 25% or less, as shown in Figure 2. The proportion of neurointerventionists who recommended PTAS in over half of their patients with ICAS decreased from 29% post-WASID to 9% post-SAMMPRIS.

Characteristics of patients selected for PTAS

In the post-SAMMPRIS survey, the patient characteristics that were most commonly selected as influencing the decision to recommend PTAS were: symptoms attributed to hypoperfusion (81%), severe stenosis (68%), impaired collaterals (59%), and recent symptoms (54%).

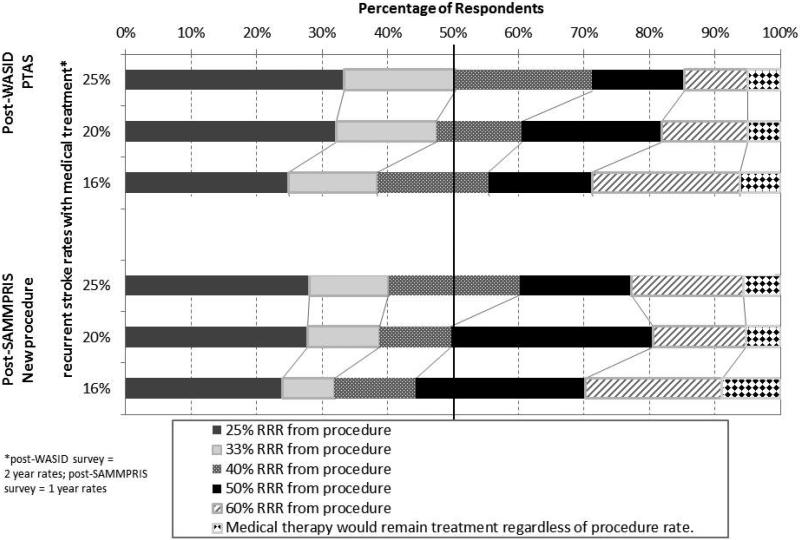

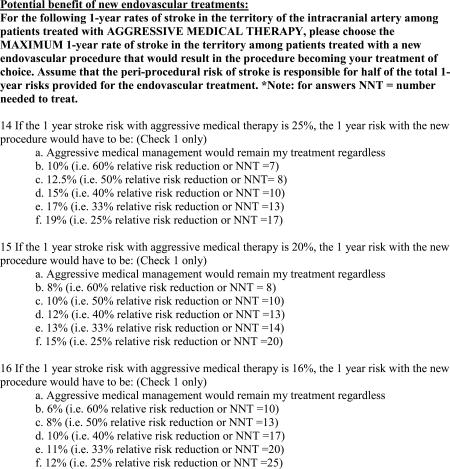

Required risk-reductions to change treatment of choice

Figure 3 shows the percentage of respondents in the post-WASID and post-SAMMPRIS surveys who selected each RRR for PTAS (post-WASID) or a “new endovascular procedure” (post-SAMMPRIS) for the proposed 2-year rates of stroke in the territory of the symptomatic stenotic artery on medical treatment. For a stroke rate of 25% on medical therapy, the majority of post-WASID respondents required a minimum RRR of 33% (corresponding to a number needed to treat (NNT) of 13) from PTAS to make PTAS their treatment of choice. As the stroke rate on medical therapy decreased, the RRR required increased. In the post-SAMMPRIS survey, the majority of respondents wanted a RRR of 40% (NNT of 10 for a stroke rate of 25% on medical therapy) from the “new procedure”, which is a higher RRR compared to the post-WASID survey respondents for the same event rate of 25% on medical therapy. For a medical therapy stroke rate of 16%, the majority of post-WASID respondents required a minimum RRR of 40% (NNT of 17) from PTAS to make PTAS their treatment of choice. In the post-SAMMPRIS survey, the majority of respondents wanted a RRR of 50% (NNT of 13 for a stroke rate of 16% on medical therapy) from the “new procedure”, which is also a higher RRR compared to the post-WASID survey respondents for the same event rate of 16% on medical therapy.

Figure 3.

Relative Risk Reduction (RRR) required by respondents to make the endovascular procedure the treatment of choice over medical therapy

Impact on practice

In the Post-SAMMPRIS survey, 91% (100/110) of respondents who participated in SAMMPRIS and 82% (228/277) of overall respondents indicated that the SAMMPRIS results changed the way they managed patients with ICAS.

DISCUSSION

Previous surveys have examined stroke prevention practices9-11, but our surveys focused on the impact of two large randomized clinical trials on physician treatment practices for ICAS in the US. We found significant differences in treatment choices for both medical and endovascular treatment of ICAS across the 3 surveys. While we found a tendency to adopt both medical and endovascular treatments supported by the clinical trial results, not all of the more effective treatment strategies in the trials were widely adopted.

Medical management of ICAS changed over the three study periods, which extended over more than a decade. After the publication of the WASID results, most neurologists preferred antiplatelet therapy over warfarin, and the preferred antiplatelet agent in the post-WASID survey was aspirin. However, despite the fact that aspirin was the only antiplatelet agent tested in WASID, a surprising number of respondents in the post-WASID survey (more than half) preferred other antiplatelet agents or combinations of antiplatelet agents over aspirin. This finding may be due to studies that showed other antiplatelet regimens may have a role in preventing stroke in patients with large artery atherosclerosis12, 13. The most commonly prescribed dose of aspirin in the post-WASID survey was 325 mg/day, despite the fact that the dose used in WASID was 1300 mg/day14. A stroke prevention guideline statement published around the time of the post-WASID survey (2006) recommended aspirin doses of 50-325 mg/day in patients with atherosclerotic stroke or TIA based on general safety and efficacy data15, suggesting that our survey results regarding aspirin dose are consistent with consensus expert opinion at the time.

The neurologists’ preference for dual antiplatelet (aspirin and clopidogrel) therapy in patients with ICAS increased from the post-WASID to the post-SAMMPRIS surveys. This is likely because of the lower early recurrent stroke rates in SAMMPRIS (when patients were on a combination of aspirin and clopidogrel) compared to WASID historical controls taking either aspirin or warfarin6. Results from the CLAIR study also that showed combined aspirin and clopidogrel decreased the number of microembolic signals on transcranial doppler compared to aspirin alone in patients with recently symptomatic ICAS 16, further supporting the use of dual antiplatelet therapy for early recurrent stroke prevention in ICAS. However, despite the fact that in the SAMMPRIS trial dual antiplatelet therapy was only used for 90 days, almost equal numbers of respondents in the post-SAMMPRIS survey recommended dual antiplatelet therapy for 90 days (45%) and indefinitely (44%). So, in both the post-WASID and post-SAMMPRIS surveys it appears that the general selection of anti-thrombotic agents may be influenced by the clinical trial results, but that the specifics of the trial treatment protocols (e.g. specific antiplatelet agent or duration of treatment) were not strictly adopted.

The post-SAMMPRIS survey respondents’ definitions of “maximal medical management” included risk factor modification as a component, with only 4% of respondents indicating that “failure of medical therapy” was limited to failure of antithrombotic agents alone. This finding probably reflects the respondents’ recognition of the benefit of intensive risk factor management for improving the outcomes in medically treated patients in the SAMMPRIS trial compared to WASID historical controls6 as well as previous analyses of WASID and SAMMPRIS data that have demonstrated that ‘failure of antithrombotic therapy’ is not a useful predictor of increased risk of recurrent stroke in patients with ICAS17, 18.

While the majority of neurologists recommend PTAS in < 10% of their patients with ICAS in all survey periods, the percentage of neurologists who recommended PTAS in > 10% of patients significantly increased from the pre- to the post-WASID surveys. This finding is consistent with a retrospective study that showed an increase in intracranial PTAS procedures after the publication of the WASID results19. The increased frequency of endovascular procedures for ICAS after WASID, despite lack of evidence for their efficacy for stroke prevention, may have reflected a perceived failure of medical therapies given the high risk of recurrent stroke in WASID and the availability of the Wingspan stenting system that was approved by the FDA under a humanitarian device exemption (August 3, 2005). However, in the post-SAMMPRIS survey, the percentage of neurologists who recommended PTAS in > 10% of patients returned to pre-WASID levels, likely due to the early SAMMPRIS results that showed no benefit from PTAS6.

The post-WASID and post-SAMMPRIS surveys asked respondents what benefit they would require from endovascular procedures (PTAS and a “new endovascular procedure”, respectively) over medical therapy to make the procedure their treatment of choice for ICAS. For carotid stenosis, the North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET)20 showed the 2-year risk of ipsilateral stroke in patients with symptomatic extracranial carotid stenosis was 26% on medical therapy and 9% with surgical therapy, resulting in a NNT with endarterectomy of 6 patients. In our survey of ICAS treatment preferences, for a risk of stroke on medical therapy similar to NASCET (25% at 2-years), the majority of our respondents required a NNT of 13 patients to make an endovascular procedure the treatment of choice over medical therapy. This finding suggests that physicians may incorporate the risk/benefit ratio of established stroke prevention interventions into their expected benefits of procedures or they may have an inherent threshold for benefit that they feel is optimal for similar high-risk conditions. As expected, the RRR from PTAS and the “new endovascular procedure” required by our survey respondents increased as the proposed risk of stroke on medical therapy decreased. In other words, as the rates of recurrent stroke with medical therapy decrease, the respondents require a much larger benefit from ICAS endovascular procedures to make the procedures their treatment of choice.

One of the reasons we undertook the post-WASID survey was to help design the “Stenting and Aggressive Medical Management for Preventing Recurrent stroke in Intracranial Stenosis (SAMMPRIS)” Trial21. Historically, the hypothesized benefit of one treatment over another in many trials has been selected by estimating the treatment effect that physicians and patients would deem important to adopt a new treatment and by considering the feasibility of recruiting the required sample size. We chose to quantify the minimum benefit from PTAS that would make it the treatment of choice by surveying physicians who take care of patients with ICAS. The use of physician surveys may provide a more scientific approach for determining the clinically meaningful benefit that physicians will require to adopt a new treatment, thereby increasing the impact of clinical trials on clinical practice.

Our study has some weaknesses, including the practice type and experience differences between the pre- and post-WASID survey respondents. The post-WASID survey included more University-based respondents than the other surveys, but the majority of respondents were at University centers in all 3 surveys. Additionally, we did not survey a random sample of physicians who take care of patients with ICAS and we limited the survey to physicians in the US. Given that the approach to patients with intracranial stenosis varies in different countries such as China22, our results may not be representative of physicians who treat patients with ICAS worldwide. Finally, our survey data are self-reported and therefore subject to the inherent biases of such data, such as social desirability bias and recall bias.

In summary, our study shows that after the publications of the NIH-funded WASID and SAMMPRIS trials, there was a significant change in physician self-reported medical and endovascular treatment practices for ICAS in the US. Based on these results, we expect that future clinical trials to determine the best management of patients with ICAS will likely have a significant impact on physician practices.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING:

Warfarin-Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease (WASID) was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) (R01NS36643). TNT, MJL, GC, SS, BJS, and MIC currently receive funding from the research grant (U01NS058728) from NINDS for the Stenting and Aggressive Medical Management for Prevention of Recurrent stroke in Intracranial Stenosis Trial (SAMMPRIS). The use of the REDCap survey tool was supported by NIH (NCATS UL1TR000062).

TNT receives funding from NINDS for research on intracranial stenosis (K23NS069668), BJS receives funding from NINDS for the Neurological Emergencies Treatment Trial Network, MIC received funding from NINDS for WASID (R01NS36643) and other research on intracranial stenosis (K24 NS050307 and R01NS051688)

Appendix A

Appendix B

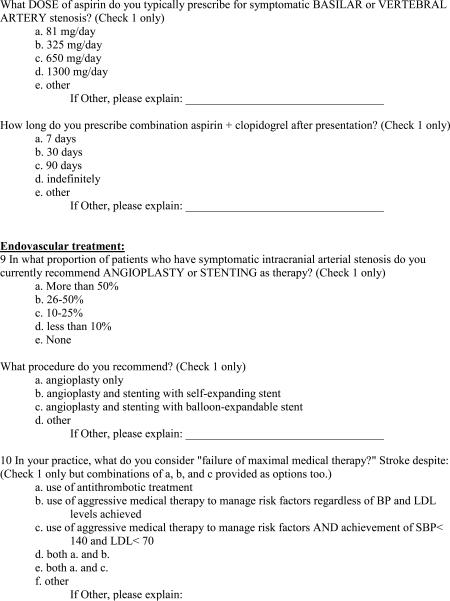

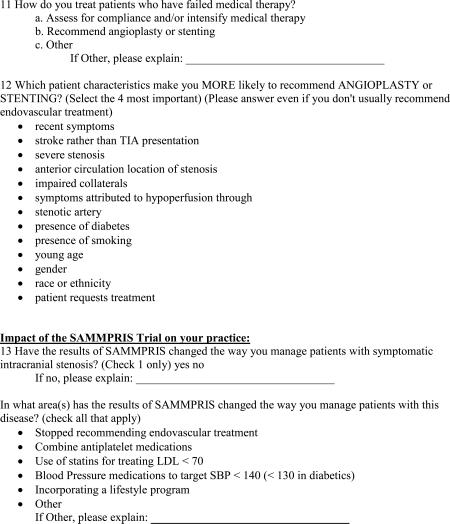

Appendix C: Intracranial Stenosis Treatment Post-SAMMPRIS

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES:

RHW, MJL, GC, JEW, and SS have no relevant conflicts to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sacco RL, Kargman DE, Zamanillo MC. Race-ethnic differences in stroke risk factors among hospitalized patients with cerebral infarction: The northern manhattan stroke study. Neurology. 1995;45:659–663. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.4.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorelick P, Wong K, Bae H, Pandey D. Large artery intracranial occlusive disease, a large worldwide burden but a relatively neglected frontier. Stroke. 2008;39:2396–2399. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.505776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chimowitz MI, Kokkinos J, Strong J, Brown MB, Levine SR, Silliman S, Pessin MS, Weichel E, Sila CA, Furlan AJ, et al. The warfarin-aspirin symptomatic intracranial disease study. Neurology. 1995;45:1488–1493. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.8.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caplan L, Babikian V, Helgason C, Hier DB, DeWitt D, Patel D, Stein R. Occlusive disease of the middle cerebral artery. Neurology. 1985;35:975–982. doi: 10.1212/wnl.35.7.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Howlett-Smith H, Stern BJ, Hertzberg VS, Frankel MR, Levine SR, Chaturvedi S, Kasner SE, Benesch CG, Sila CA, Jovin TG, Romano JG. Warfarin-Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease Trial Investigators. Comparison of warfarin and aspirin for symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;352:1305–1316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Derdeyn CP, Turan TN, Fiorella D, Lane BF, Janis LS, Lutsep HL, Barnwell SL, Waters MF, Hoh BL, Hourihane JM, Levy EI, Alexandrov AV, Harrigan MR, Chiu D, Klucznik RP, Clark JM, McDougall CG, Johnson MD, Pride GL, Jr., Torbey MT, Zaidat OO, Rumboldt Z, Cloft HJ. SAMMPRIS Trial Investigators. Stenting versus aggressive medical therapy for intracranial arterial stenosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365:993–1003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (redcap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turan TN, Lynn MJ, Nizam A, Lane B, Egan BM, Le NA, Lopes-Virella MF, Hermayer KL, Benavente O, White CL, Brown WV, Caskey MF, Steiner MR, Vilardo N, Stufflebean A, Derdeyn CP, Fiorella D, Janis S, Chimowitz MI. Rationale, design, and implementation of aggressive risk factor management in the stenting and aggressive medical management for prevention of recurrent stroke in intracranial stenosis (sammpris) trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:e51–60. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.966911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masuhr F, Busch M, Einhaupl KM. Differences in medical and surgical therapy for stroke prevention between leading experts in north america and western europe. Stroke. 1998;29:339–345. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldstein LB, Bonito AJ, Matchar DB, Duncan PW, Samsa GP. Us national survey of physician practices for the secondary and tertiary prevention of ischemic stroke : Carotid endarterectomy. Stroke. 1996;27:801–806. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.5.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldstein LB, Bonito AJ, Matchar DB, Duncan PW, DeFriese GH, Oddone EZ, Paul JE, Akin DR, Samsa GP. Us national survey of physician practices for the secondary and tertiary prevention of ischemic stroke : Design, service availability, and common practices. Stroke. 1995;26:1607–1615. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.9.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halkes PH, van Gijn J, Kappelle LJ, Koudstaal PJ, Algra A. Aspirin plus dipyridamole versus aspirin alone after cerebral ischaemia of arterial origin (esprit): Randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367:1665–1673. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68734-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Markus HS, Droste DW, Kaps M, Larrue V, Lees KR, Siebler M, Ringelstein EB. Dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin in symptomatic carotid stenosis evaluated using doppler embolic signal detection: The clopidogrel and aspirin for reduction of emboli in symptomatic carotid stenosis (caress) trial. Circulation. 2005;111:2233–2240. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000163561.90680.1C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warfarin-Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease Trial Investigators Design, progress and challenges of a double-blind trial of warfarin versus aspirin for symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis. Neuroepidemiology. 2003;22:106–117. doi: 10.1159/000068744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sacco RL, Adams R, Albers G, Alberts MJ, Benavente O, Furie K, Goldstein LB, Gorelick P, Halperin J, Harbaugh R, Johnston SC, Katzan I, Kelly-Hayes M, Kenton EJ, Marks M, Schwamm LH, Tomsick T. Guidelines for prevention of stroke in patients with ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack. Circulation. 2006;113:e409–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong KSL, Chen C, Fu J, Chang HM, Suwanwela NC, Huang YN, Han Z, Tan KS, Ratanakorn D, Chollate P, Zhao Y, Koh A, Hao Q, Markus HS. Clopidogrel plus aspirin versus aspirin alone for reducing embolisation in patients with acute symptomatic cerebral or carotid artery stenosis (clair study): A randomised, open- label, blinded-endpoint trial. The Lancet Neurology. 2010;9:489–497. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70060-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turan TN, Maidan L, Cotsonis G, Lynn MJ, Romano JG, Levine SR, Chimowitz MI. Failure of antithrombotic therapy and risk of stroke in patients with symptomatic intracranial stenosis. Stroke. 2009;40:505–509. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.528281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lutsep H, Barnwel lS, Larsen D, Lynn M, Turan T, Lane B, Janis S, Derdeyn C, Fiorella D, Chimowitz M. Outcome of patients in the sammpris trial who had failed antithrombotic therapy at study enrollment [abstract]. Stroke. 2012:LB5. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.007752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moskowitz SI, Kelly ME, Obuchowski N, Fiorella D. Impact of wasid and wingspan on the frequency of intracranial angioplasty and stenting at a high volume tertiary care hospital. Journal of neurointerventional surgery. 2009;1:165–167. doi: 10.1136/jnis.2009.000497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 1991;325:445–453. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108153250701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Turan TN, Fiorella D, Lane BF, Janis S, Derdeyn CP. Design of the stenting and aggressive medical management for preventing recurrent stroke in intracranial stenosis trial. Journal of stroke and cerebrovascular diseases. 2011;20:357–368. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu X, Xiong Y, Zhou Z, Niu G, Wang W, Xiao G, Lin M, Leung TW, Liu D, Liu W, Fan X, Yin Q, Zhu W, Ma M, Zhang R, Xu G. China interventional stroke registry: Rationale and study design. Cerebrovascular diseases (Basel, Switzerland) 2013;35:349–354. doi: 10.1159/000350210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]