Abstract

Previous work has shown that the obligate intracellular amoebal endosymbiont Neochlamydia S13, an environmental chlamydia strain, has an amoebal infection rate of 100%, but does not cause amoebal lysis and lacks transferability to other host amoebae. The underlying mechanism for these observations remains unknown. In this study, we found that the host amoeba could completely evade Legionella infection. The draft genome sequence of Neochlamydia S13 revealed several defects in essential metabolic pathways, as well as unique molecules with leucine-rich repeats (LRRs) and ankyrin domains, responsible for protein-protein interaction. Neochlamydia S13 lacked an intact tricarboxylic acid cycle and had an incomplete respiratory chain. ADP/ATP translocases, ATP-binding cassette transporters, and secretion systems (types II and III) were well conserved, but no type IV secretion system was found. The number of outer membrane proteins (OmcB, PomS, 76-kDa protein, and OmpW) was limited. Interestingly, genes predicting unique proteins with LRRs (30 genes) or ankyrin domains (one gene) were identified. Furthermore, 33 transposases were found, possibly explaining the drastic genome modification. Taken together, the genomic features of Neochlamydia S13 explain the intimate interaction with the host amoeba to compensate for bacterial metabolic defects, and illuminate the role of the endosymbiont in the defense of the host amoebae against Legionella infection.

Introduction

Obligate intracellular chlamydiae have evolved into two groups since the divergence of ancient chlamydiae 0.7–1.4 billion years ago. Pathogenic chlamydiae species (e.g. Chlamydia trachomatis) have adapted with their vertebrate hosts, whereas environmental chlamydiae (e.g. Neochlamydia species) have evolved as endosymbionts of lower eukaryotes, such as free-living amoebae (Acanthamoeba) [1]–[4]. Both types of chlamydiae have unique intracellular developmental cycles, defined by two distinct stages: the elementary body (EB), which is the form that is infectious to host cells, and the reticulate body (RB), which is the replicative form in the cells [4]. Interestingly, pathogenic chlamydiae have evolved through a decrease in genome size, with genomes of approximately 1.0–1.2 Mb, which may be a strategy to evade the host immune network, resulting in a shift to parasitic energy and metabolic requirements [1]–[4]. Meanwhile, the genome of the representative environmental chlamydia, Protochlamydia UWE25, is not decreasing and has stabilized at 2.4 Mb [4], implying that environmental chlamydiae still possess certain genes that pathogenic chlamydiae have lost. Therefore, environmental chlamydiae are useful tools for elucidating chlamydial evolution and obligate intracellular parasitism.

Recently, we isolated several environmental amoebae harboring endosymbiotic environmental chlamydiae from Sapporo, Hokkaido, Japan [5]. Of these, the amoebal endosymbiont Neochlamydia S13 was particularly interesting because its rate of amoebal infection was always 100%, but no amoebal lysis or transfer to other host amoebae was observed [5], [6]. This suggested an intimate mutualistic interaction of Neochlamydia S13 with its host amoebae, which is possibly a unique genomic feature. The reason why amoebae continually feed the endosymbiotic bacteria remains unknown, although the endosymbiotic bacteria may protect the host against Legionella, which also grow in and kill amoebae [7]–[9]. Therefore, in this study we evaluated the interaction of Neochlamydia S13 with the host amoebae, including its protective role against Legionella, through analysis of a draft genome of Neochlamydia S13.

Results and Discussion

Neochlamydia S13 intimately interacts with host amoebae and plays a significant role in the amoebal protection system against Legionella pneumophila infection

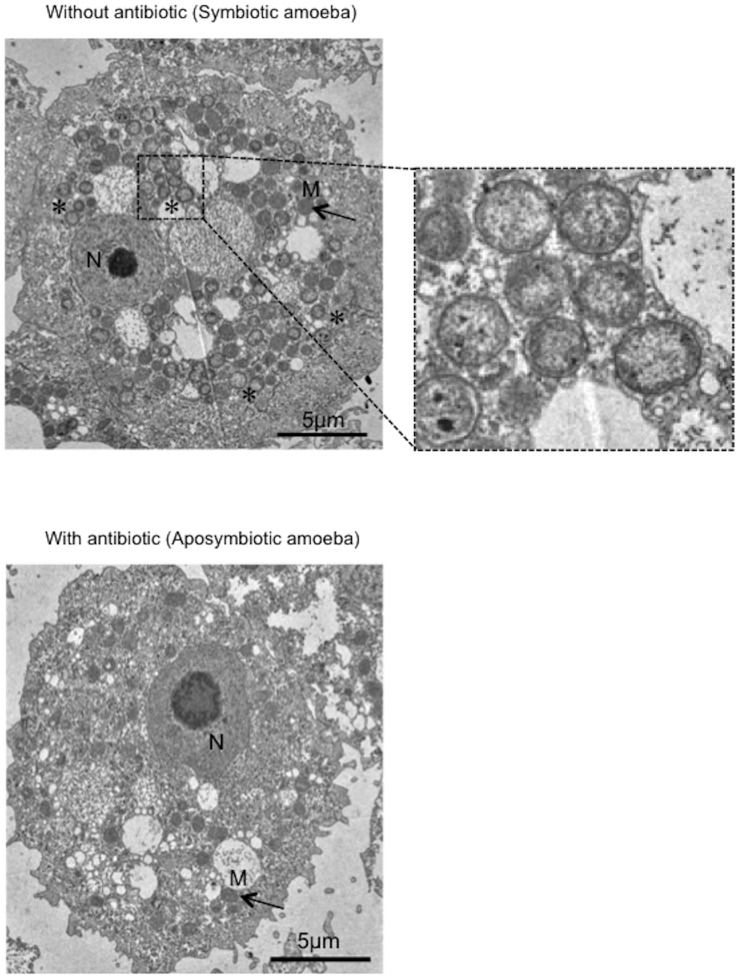

Transmission electron microscopic (TEM) analysis revealed a wide distribution of RBs in the amoebal cytoplasm, but no EBs were observed, suggesting persistent infection and an intimate interaction between the bacteria and the host amoeba (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Morphological traits of Neochlamydia S13 inside host amoebae.

Representative TEM images showing symbiotic amoebae harboring Neochlamydia S13 (up and right (enlarged)) and aposymbiotic amoebae constructed by treatment with antibiotics (down). Enlarged image in the square with a dotted line shows the bacterial reticular body (no elementary body was observed in the amoebae). *, bacteria. M, mitochondria (arrows). N, nucleus.

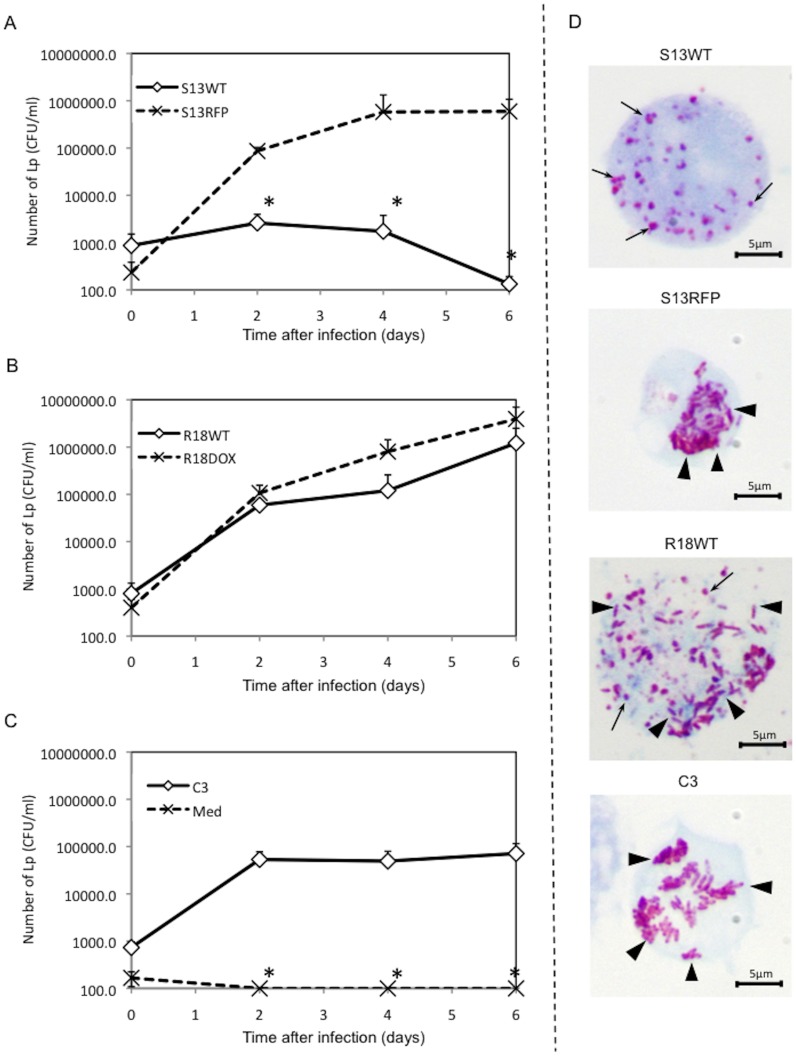

Why the amoebae allow Neochlamydia to persist within the cells remains unknown. We therefore assessed whether the amoebae harboring Neochlamydia S13 could resist infection by L. pneumophila, which can kill amoebae in natural environments [7]–[9]. In contrast to the extensive growth observed in the aposymbiotic strain of amoeba (S13RFP: treatment with rifampicin), L. pneumophila failed to replicate in amoebae harboring Neochlamydia S13 wild-type (WT) (Figure 2A). Another amoebal strain, harboring Protochlamydia R18 (R18WT) [5], also allowed intracellular growth of L. pneumophila, as did the aposymbiotic amoeba R18DOX (treatment with doxycycline) and the reference C3 amoebal strain, which lacks any endosymbiotic bacteria (Figure 2B and C). Gimenez staining showed that L. pneumophila failed to grow in amoebae harboring Neochlamydia S13 (Figure 2D, top (arrows, Neochlamydia S13)). Thus, the results strongly suggested that Neochlamydia S13 confers a survival advantage on the host by providing resistance to L. pneumophila infection in amoebal environments such as biofilms [10], [11].

Figure 2. Amoebae harboring Neochlamydia S13 are completely protected from L. pneumophila infection.

(A) L. pneumophila survival in Neochlamydia S13-infected amoebae (S13WT) and aposymbiotic amoebae (S13RFP). (B) L. pneumophila growth in Protochlamydia R18-infected amoebae (R18WT) and aposymbiotic amoebae (R18DOX). (C) L. pneumophila survival in C3 reference strain amoebae (C3), and PYG medium only (Med). Data are the means ± SD from at least three independent experiments performed in triplicate. * denotes p<0.05 at each of the time points. (D) Representative Gimenez staining images showing L. pneumophila replication into amoebae at 5 days post-infection. Arrows, Neochlamydia S13 (S13WT) or Protochlamydia R18 (R18WT). Arrowheads, replicated L. pneumophila.

Phylogenetic analysis of 16S rRNA sequences showed that Neochlamydia S13 belonged to its own cluster, sequestered from other chlamydiae (Figure S1, arrow). Thus, the phylogenetic data suggest unique genomic features in Neochlamydia S13.

General genome features and validity

A draft genome of Neochlamydia S13 was determined by Illumina GAIIx, assembled with ABySS-pe, and then annotated by the RAST server with manual local BLAST analysis. The draft genome of Neochlamydia S13 contained 3,206,086 bp (total contig size) with a GC content of 38.2% in 1,317 scaffold contigs (DDBJ accession number: BASK01000001–BASK01001342). The genome contains 2,832 protein-coding sequences (CDSs), 43 tRNAs, and six ribosomal RNAs (Table S1). About half of the CDSs (1,577; 57%) were classified as hypothetical proteins, including 1,030 unknown proteins (36.4%) that had no significant similarity to those of other chlamydiae (Protochlamydia amoebophila UWE25 (NC_005861.1), Parachlamydia acanthamoebae UV-7 (NC_015702.1), Simkania negevensis Z (NC_015713.1), Waddlia chondrophila WSU 86-1044 (NC_014225.1), Chlamydia trachomatis D/UW-3/CX (NC_000117.1), C. trachomatis L2 434/Bu (NC_010287.1), Chlamydia pneumoniae CWL029 (NC_000922.1), C. pneumoniae TW183 (NC_005043.1)) in public databases (E-value >1e−10) (Figure S2). This suggested that Neochlamydia S13 contains unique genomic features, which may provide hints for discovering the intimate mutual relationship underlying symbiosis.

Because of the presence of so many unknown genes with repeat sequences in the predicted genome, we were unable to fill all of the gaps to complete the genome of Neochlamydia S13. The validity of our system, including scaffold contig assembly and gene annotation, was confirmed by comparing the reference genome of Protochlamydia UWE25 (NC_005861.1) with the draft genome of its related amoebal endosymbiont, Protochlamydia R18 (originally isolated from a river in Sapporo City, Japan [5]), assembled using our system for this study. The draft genome of Protochlamydia R18 contained 2,727,392 bp with a GC content of 38.8% in 770 scaffold contigs (DDBJ accession number: BASL01000001–BASL01000795). An ORF annotation coverage of 87.6% was observed.

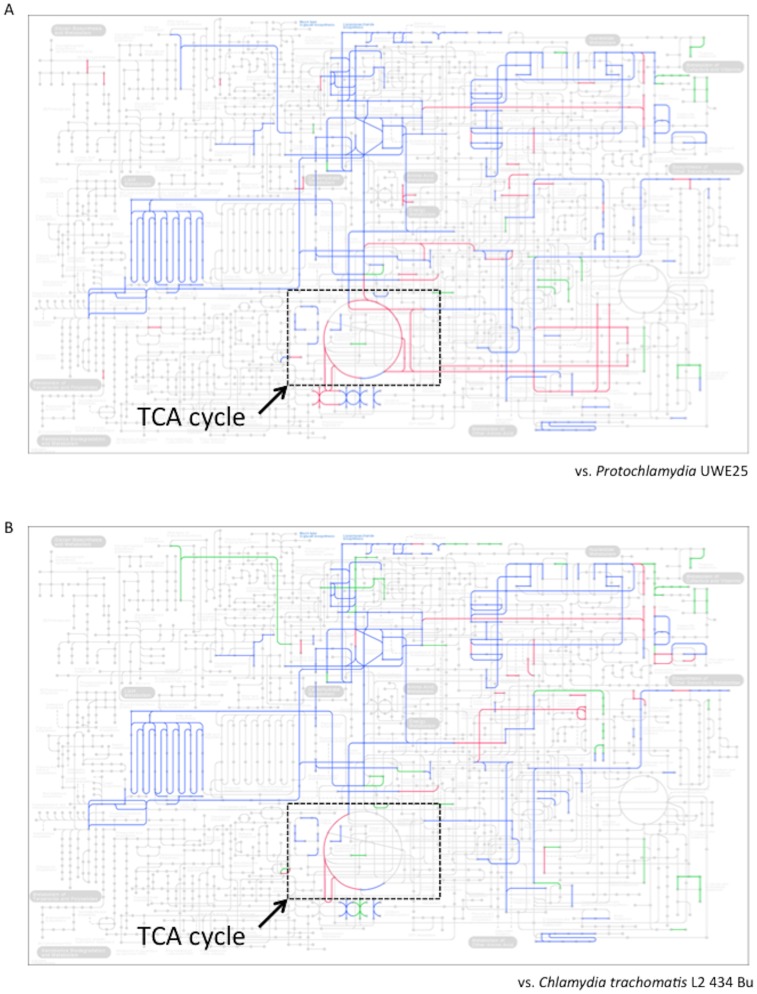

Glycolytic pathway, tricarboxylic acid cycle, and respiratory chain are incomplete

As mentioned above, the previous findings of an amoebal infection rate of 100% and absence of amoebal lysis and transferability to other host amoebae suggest a defective energy reserve system in Neochlamydia S13. We therefore used KEGG-module analysis to determine whether Neochlamydia S13 contained complete metabolic pathways. This showed that the Neochlamydia S13 modules that mapped onto the metabolic pathways differed significantly from those of other chlamydiae (Protochlamydia UWE25 and C. trachomatis L2) (Figure 3). While the glycolytic pathway from fructose 1,6-bisphosphate to pyruvate was complete in Neochlamydia S13, hexokinase and 6-phosphfructokinase were missing, indicating a truncated Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas pathway (Figure S3). Analysis also confirmed that while the Entner-Doudoroff pathway was truncated, the pentose phosphate pathway was intact, suggesting ribulose-5-phosphate synthesis with folate metabolic activity (Figure S3). Surprisingly, the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, which oxidizes acetyl-CoA to CO2, was almost entirely missing, except for malate dehydrogenase, the dihydrolipoamide succinyltransferase component (E2) of the 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex, and dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase of 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (Figure S3). As pathogenic chlamydiae are still viable when carrying at least half of the TCA cycle genes [2], [12], and all previously reported environmental chlamydiae possess complete TCA cycles [4], [13], [14], the lack of the cycle in the Neochlamydia S13 genome is unique. We also found a defective respiratory chain, equipped with only the NADH dehydrogenase complex, cytochrome c oxidase complex, and V-type ATPase units; the succinate dehydrogenase complex, cytochrome c reductase complex, and F-type ATPase units were completely missing (Figure S4). Thus, these data show that the central metabolic pathway of Neochlamydia S13 is drastically truncated, even when compared with pathogenic chlamydiae, indicating a strong dependence on host amoebae.

Figure 3. Comparison of metabolic pathways among representative chlamydiae.

(A) Neochlamydia S13 (this study) versus Protochlamydia amoebophila UWE25 (NC005861.1). (B) Neochlamydia S13 versus C. trachomatis L2 434 Bu (NC010287.1). Green lines, unique in the Neochlamydia active modules. Blue lines, shared modules. Red lines; modules specific for Protochlamydia or C. trachomatis. Squares surrounded with dotted line show TCA cycle.

Fatty acid biosynthesis pathways are conserved

As the genes of the fatty acid initiation and biosynthesis pathways were conserved, as in other chlamydiae (Figure S5), it seemed likely that Neochlamydia S13 could produce fatty acid. However, synthesis pathways for CoA, which is a starting material for the acetyl-CoA required for fatty acid initiation [15], [16], and biotin, which is a coenzyme required for fatty acid construction [17], [18] were lacking in Neochlamydia S13. These findings therefore suggest that both CoA and biotin may be transported from the amoebal cytoplasm into the bacteria by unknown transporters.

ATP/ADP translocases, ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters, the Sec-dependent type II secretion system, and the type III secretion systems, but not the type IV secretion system, are well conserved

Similar to pathogenic chlamydiae, Neochlamydia S13 lacked many key enzymes in the purine and pyrimidine metabolic pathways that are directly connected to nucleotide biosynthesis. It therefore seemed likely that Neochlamydia S13 might obtain ATP from the host amoebal cytoplasm via a number of ATP/ADP translocases. As expected, three translocases (NTT1–NTT3) similar to those of pathogenic chlamydiae (Figure S6A) were identified in the genome, although environmental chlamydia strain UWE25 contains five ATP/ADP translocases [19], [20]. We also found several ABC transport systems (spermidine/putrescine, zinc, mannan, lipopolysaccharide, and lipoprotein) in the annotated genome (Figure S6B). These findings suggest significant roles for the ABC transporters in compensating for the defective metabolic systems of the bacteria, possibly explaining the intimate symbiotic interaction and strong host dependency. Meanwhile, the number of ABC transporters identified in the draft genome was limited, although these transporters are generally widespread among living organisms and are highly conserved in all genera. They are responsible for essential biological processes such as material transport, translation elongation, and DNA repair [21]–[23].

We next assessed whether secretion systems (Sec-dependent type II, type III, and type IV) were conserved in the Neochlamydia S13 genome. As shown in Figure S7, the type III secretion system, which is widely distributed among chlamydiae [24]–[26], was well conserved in the Neochlamydia S13 genome, and the Sec-dependent type II secretion system was nearly completely conserved (Figure S8). These findings suggested that both systems aid Neochlamydia S13 survival in the host amoebae. Interestingly, in contrast to previously reported environmental chlamydiae [4], [13], [27], [28], no gene cluster encoding the type IV secretion system was found, similar to pathogenic chlamydiae, although the Protochlamydia R18 genome contained a complete type IV gene cluster (Figure S9, Protochlamydia UWE25 versus Protochlamydia R18). Recent works have strongly suggested that bacterial type IV secretion systems might induce inflammasome or caspase activation, resulting in bacterial elimination via accumulation of professional effector cells [29]–[31]. It is therefore possible that the type IV secretion system is harmful to the symbiotic interaction in host cells, as well as persistent infection that generally occurs in mammalian cells.

Predicted outer membrane proteins were truncated

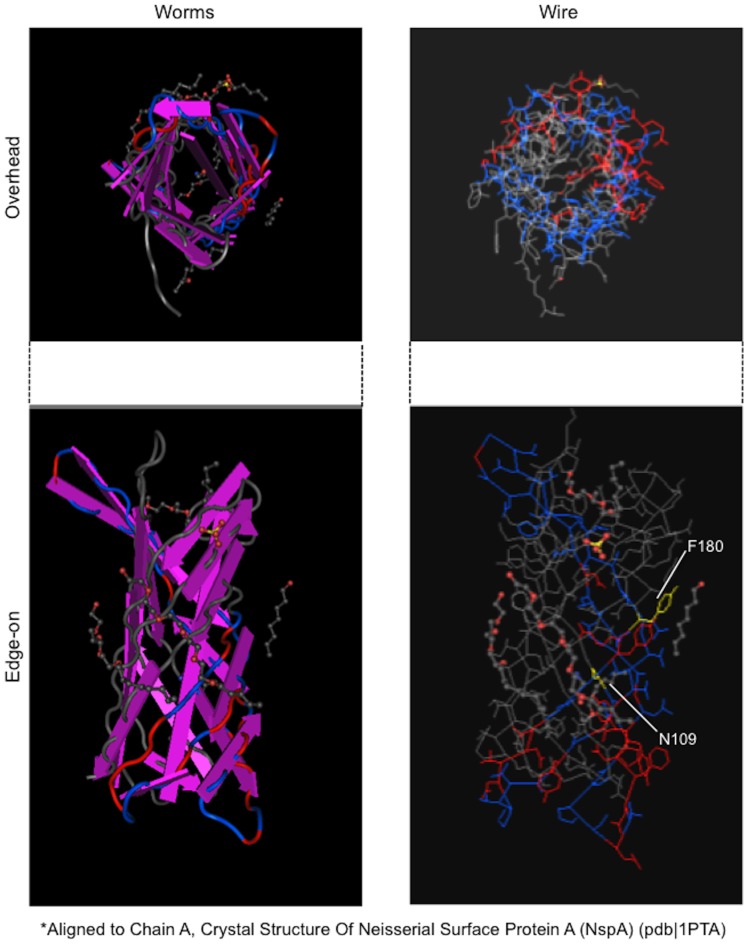

In contrast to Protochlamydia UWE25 [13], [32], [33], Neochlamydia S13 contained fewer annotated genes encoding outer membrane proteins, which presumably localize to the outer leaflet membrane and periplasmic space. These genes, pomS, the 76-kDa protein gene (Protochlamydia UWE25, pc0004), ompW, and omcB (Figure S10), indicate successful adaptation to the host amoebal cytoplasm through loss of redundant molecules. The predicted 3D model of PomS (NEOS13_1146), constructed using MMDB (see “Methods”), showed a porin with a β-barrel structure and a channel (Figure 4), suggesting an active transporter.

Figure 4. Predicted three-dimensional structure of PomS (NEOS13_1146), which presumably localizes to the outer membrane as a porin.

The structure was constructed by alignment with the crystal structure of chain A of Neisseria surface protein A (NspA) (pdb:1PTA). N109 (yellow), amino acid aligned at start position. F180 (yellow), amino acid aligned at end position.

Predicted proteins with leucine-rich repeats (LRRs) or ankyrin domains

As mentioned above, we found that amoebae harboring Neochlamydia S13 were never infected with L. pneumophila, which is a natural killer of amoebae [7]–[9], [10], [11]. We hypothesized that Neochlamydia S13 effector molecules secreted into the amoeba might be associated with protection against L. pneumophila infection. Recent studies have intriguingly revealed that pathogenic bacteria have evolved effector proteins with LRR or ankyrin domains that may mimic host signaling molecules when injected into host cells [34]–[36]. Therefore, we searched for unique molecules with LRRs [37], [38] or ankyrin domains [39]–[41], which may be responsible for protein-protein interaction and possibly for controlling L. pneumophila infection in host amoebae, in the Neochlamydia S13 genome. We identified 199 genes encoding predicted candidate molecules with LRRs, 30 of which were unique, showing no homology with other environmental chlamydiae (Table S2). This suggests possible expansion of these genes from a small number of ancestral genes containing LRRs, although the mechanism of expansion remains unknown. However, it is possible that L. pneumophila infection could stimulate the expansion of the Neochlamydia genes encoding LRR domains. Among these genes, 15 were well conserved with those of Micromonas (algae) and Nostoc punctiforme (a nitrogen-fixing cyanobacterium), with 45–74% identity (Table S2). These results suggest horizontal gene transfer between Neochlamydia S13 and such plant-related microbes, allowing us to hypothesize an ancestral relationship between chlamydiae and algae or cyanobacteria [42]–[44].

As it is well known that molecules with ankyrin domains play a critical role in protein-protein interaction, we also searched for these genes in the Neochlamydia S13 genome. RAST analysis with manual local BLAST analysis predicted eight genes (NEOS13_0151, NEOS13_0209, NEOS13_0435, NEOS13_0856, NEOS13_1517, NEOS13_1563, NEOS13_2364, NEOS13_2796) that encode molecules with ankyrin domains. Interestingly, NEOS13_0151 had a unique coiled-coil structure that was not similar to other chlamydial proteins (Table S1, Figure S11). Meanwhile, phylogenetic analysis of NEOS13_0151 revealed close similarity with functional molecules found in eukaryotes (Figure S12), presumably associated with host cell modification or cellular functions. Recent work has shown that the L. pneumophila (strain AA100/130b) F-box ankyrin effector is involved in eukaryotic host cell exploitation, allowing intracellular growth [45]. Thus, we suggest that Neochlamydia S13 possesses unique genes encoding ankyrin domains, possibly responsible for resisting L. pneumophila infection via host amoebae, although the underlying mechanism remains to be determined.

Presence of transposases implies drastic genome modification

We found 33 genes encoding transposases in the Neochlamydia S13 genome, as annotated by RAST analysis with manual local BLAST analysis (Table S1). It has been reported that Chlamydia suis possesses a novel insertion element (IScs605) encoding two predicted transposases [46], and that Protochlamydia UWE25 contains 82 transposases [47]. Thus, the features of the Neochlamydia S13 genome were unique, without genome reduction, but with specified genes for controlling host-parasite interaction, resulting in successful adaptation to the host amoeba. Although the reason why the Neochlamydia S13 genome size has not reduced remains unknown, such transposases may be responsible for genome modification without genome reduction.

Conclusions

We determined a draft genome sequence of Neochlamydia S13, which provided hints as to why the mutualistic interaction between the bacteria and the host amoebae is maintained, and how the bacteria manipulate the host amoebae. Such unique genome features of Neochlamydia S13 strongly indicate an intimate dependency on the host amoebae to compensate for lost bacterial metabolic activity, and a possible role for the bacterial endosymbiont in defense against L. pneumophila. These findings provide new insight into not only the extraordinary diversity between chlamydiae, but also why symbiosis occurred between the amoebae and environmental chlamydiae.

Materials and Methods

Amoebae

As described previously [5], two different amoebal (Acanthamoeba) strains persistently infected with Protochlamydia R18 or Neochlamydia S13 were isolated from a river water sample and a soil sample, respectively. The prevalence of amoebae with endosymbionts, as defined by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole staining, was always approximately 100% [6]. Acanthamoeba castellanii C3 (ATCC 50739) was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and used as a reference strain. Aposymbiotic amoebae derived from Protochlamydia R18-infected amoebae (designated R18DOX, established by treatment with doxycycline (64 µg/ml)) and Neochlamydia S13-infected amoebae (designated S13RFP, established by treatment with rifampicin (64 µg/ml)) [6] were also used for this study. All amoebae were maintained in PYG broth (0.75% (w/v) peptone, 0.75% (w/v) yeast extract, and 1.5% (w/v) glucose) at 30°C [5].

Bacteria

Human isolate L. pneumophila Philadelphia I (JR32), equipped with a complete dot/icm gene set encoding a type IV secretion system, which is required for intracellular amoebal growth [48], was kindly provided by Dr. Masaki Miyake of the University of Shizuoka, Japan. L. pneumophila was cultured on BCYE agar (OXOID, Hampshire, UK) at 37°C for 2 days.

Infection of amoebae with L. pneumophila

Amoebae (5×105 cells) were infected with L. pneumophila (5×105 colony-forming units [CFU]) at a multiplicity of infection of one for 2 h at 30°C, and then uninfected bacteria were killed by the addition of 50 µg/ml gentamycin. After washing with PYG medium, the infected amoebae were incubated for up to 6 days. The infected amoebae were collected every other day, and bacterial CFUs were estimated by serial dilution on BCYE agar.

Bacterial purification and genomic DNA extraction

Both Neochlamydia S13- and Protochlamydia R18-infected amoebae were collected by centrifugation at 1,500× g for 30 min. The resulting pellets were suspended in PYG medium. Each of the amoebae were disrupted by bead-beating for 5 min according to a previously described method [49], and then centrifuged at 150× g for 5 min to remove unbroken cells and nuclei. The supernatant including intact bacteria was incubated with DNase (Sigma) for 30 min at room temperature, and then the bacteria were washed and suspended in 10 mM HEPES buffer containing 145 mM NaCl. The suspension was carefully overlayed onto 30% Percoll. Following centrifugation at 30,000× g for 30 min, the bacteria were collected from the lower layer. Finally, bacterial pellets were stored at −20°C until use. DNA was extracted with a phenol-chloroform method.

Genome sequencing, annotation and prediction of metabolic pathway modules, and genome comparison

Bacterial 1 kb insert DNA libraries (Purified Neochlamydia S13 and Protochlamydia R18) were prepared using a genomic DNA Sample Prep Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA). DNA clusters were generated on a slide using a Cluster Generation Kit (ver. 4) on an Illumina Cluster Station, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Sequencing runs for 81-mer paired-end sequence were performed using an Illumina Genome Analyzer IIx (GA IIx). The 81-mer paired-end reads were assembled (parameters k64, n51, c32.1373) using ABySS-pe v1.2.0 [50]. Annotation of genes from the draft genome sequences was performed using Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology (RAST: http://rast.nmpdr.org/) [51] with a local manual BLASTp search. Metabolic pathway modules were predicted using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG: http://www.genome.jp/kegg/) [52]. Genome comparison was performed using RAST, and then manually visualized by GenomeMatcher 1.69 (http://www.ige.tohoku.ac.jp/joho/gmProject/gmhome.html) [53].

Prediction of 3D structure for annotated genes

Three-dimensional structures of annotated protein sequences of interest were predicted using a web program, protein BLAST with the Molecular Modeling Database (MMDB) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/MMDB/mmdb.shtml) [54]. Cn3D 4.3 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/CN3D/cn3dmac.shtml) was used to display the predicted structure [55].

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic analyses of all nucleotide sequences were conducted using the neighbor-joining method with 1,000 bootstrap replicates in ClustalW2 (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) [55]. The website viewer was also used to display the generated tree for Figure S12. Other tree in supplementary figure (Figure S1) was visualized using TreeViewX (version 0.5.0) [56].

TEM

For TEM analysis, amoebal cells were immersed in a fixative containing 3% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, for 24 h at 4°C. Following a brief wash with PBS, cells were processed by alcohol dehydration and embedding in Epon 813. Ultrathin cell sections were stained with lead citrate and uranium acetate prior to visualization by electron microscopy (Hitachi H7100; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) as described previously [57].

Statistical analysis

Data were compared using a Student's t-test. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Contig sequence accession numbers

The draft genome sequences for the Neochlamydia S13 and Protochlamydia R18 strains have been deposited in the DNA Data Bank of Japan [DDBJ accession numbers: BASK01000001–BASK01001342 (Neochlamydia S13), BASL01000001–BASL010 00795 (Protochlamydia R18)].

Supporting Information

Phylogenetic analysis of chlamydial 16S rRNA sequences. Bacterial names follow the accession numbers. Arrow denotes Neochlamydia 16S rRNA. The gene accession numbers are as follows: Chlamydia trachomatis D/UW_3/CX, NC_000117.1; Chlamydia trachomatis L2/434/Bu, NC_010287.1; Chlamydia pneumoniae TW-183, NC_005043.1; Simkania Z gsn131, NC_015713.1; Parachlamydia acanthamoebae UV7, NC_015702.1; endosymbiont Acanthamoeba UWC22, AF083616.1; endosymbiont Acanthamoeba TUME1, AF098330.1; Neochlamydia hartmannellae, AF177275.1; Parachlamydia acanthamoebae Bn9, NR_026357.1; Parachlamydia Hall's coccus, AF366365.1; Parachlamydia acanthamoebae Seine, DQ309029.1; Protochlamydia naegleriophila KNic, DQ632609.1.

(TIFF)

Venn diagram showing the numbers of common and unique proteins among three chlamydiae. Red, Chlamydia trachomatis D/UW_3/CX (NC000117.1). Green, Protochlamydia R18 (this study). Blue, Neochlamydia S13 (this study).

(TIFF)

Predicted genes annotated as glycolytic pathway and TCA cycle with pentose phosphate pathway and Entner-Doudoroff pathway. Black lines with arrows show predicted active modules. Gray lines show incomplete modules. Red names with numbers indicate Neochlamydia S13 gene IDs.

(TIFF)

Predicted genes annotated as oxidative phosphorylation pathway. Solid lines with arrows show predicted active modules. Gray lines show incomplete modules. Red names with numbers indicate Neochlamydia S13 gene IDs.

(TIFF)

Predicted genes annotated as fatty acid initiation and elongation. Black lines with arrows show predicted active modules. Red names with numbers indicate Neochlamydia S13 gene IDs.

(TIFF)

Predicted genes annotated as ATP/ADP translocases (NTTs) (A) and ABC transporters (B). Black lines with arrows show predicted active modules. Gray lines show incomplete modules. Red names with numbers indicate Neochlamydia S13 gene IDs.

(TIFF)

Comparison of genes encoding a type III secretion system from Neochlamydia S13 and Protochlamydia UWE25. The type III operon structures of the two chlamydiae are compared. Top panel, T3SS-T1; second panel, T3SS-A1; third panel, T3SS-A2; bottom panel, T3SS-A3. Right scale values show % identity estimated by BLASTp. Each of the gene cluster sequences in Protochlamydia amoebophila UWE25 (NC_005861.1) was obtained from NCBI (http:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome).

(TIFF)

Predicted genes annotated as Sec-dependent type II secretion machinery. Black line with arrow shows predicted active module. Gray boxes show incomplete molecules. Red names with numbers indicate Neochlamydia S13 gene IDs.

(TIFF)

Comparative analysis of genes encoding type IV secretion machinery from Protochlamydia UWE25 and Protochlamydia R18. No annotated type IV genes were found in the Neochlamydia S13 genome. Blue boxes indicate individual coding regions of the type IV cluster.

(TIFF)

Predicted outer membrane structures. Blue molecules were predicted to be active. Gray molecules are absent. Red names with numbers indicate Neochlamydia S13 gene IDs. This figure depicts the predicted outer membrane structure based on a findings described by Heinz et al. [34] and previous findings published by Aistleitner et al. [33].

(TIFF)

Characterization of a unique molecule with ankyrin domains (NEOS13_0151). (A) Detection of ankyrin domains in the molecule encoded by NEOS13_0151. (B) Alignment scores and 3D prediction. The scores and prediction were performed using the web program, protein BLAST with the MMDB (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/MMDB/docs/mmdb_search.html).

(TIFF)

Phylogenetic comparison of the predicted protein sequence encoded by NEOS13_0151 with other eukaryotic proteins. The predicted protein sequence encoded by NEOS13_0151 was phylogenetically compared with previously reported sequences obtained from the GenBank database using ClustalW2. The phylogenetic trees generated from the aligned sequences were constructed by neighbor-joining in ClustalW2, and then visualized with the website viewer.

(TIFF)

Neochlamydia S13 gene IDs with features.

(PDF)

Homologs of eukaryote genes in the Neochlamydia S13 genome encoding predicted LRR-molecules.

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at the Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Faculty of Health Sciences, Hokkaido University, for their assistance throughout this study.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by grants-in-aid for scientific research from KAKENHI, grant numbers 21590474, 24659194, and 24117501, “Innovation Areas (Matryoshika-type evolution)”. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Greub G, Raoult D (2003) History of the ADP/ATP-translocase-encoding gene, a parasitism gene transferred from a Chlamydiales ancestor to plants 1 billion years ago. Appl Environ Microbiol 69: 5530–5535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stephens RS, Kalman S, Lammel C, Fan J, Marathe R, et al. (1998) Genome sequence of an obligate intracellular pathogen of humans: Chlamydia trachomatis . Science 282: 754–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kalman S, Mitchell W, Marathe R, Lammel C, Fan J, et al. (1999) Comparative genomes of Chlamydia pneumoniae and C. trachomatis . Nat Genet 21: 385–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Horn M, Collingro A, Schmitz-Esser S, Beier CL, Purkhold U, et al. (2004) Illuminating the evolutionary history of chlamydiae. Science 304: 728–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Matsuo J, Kawaguchi K, Nakamura S, Hayashi Y, Yoshida M, et al. (2010) Survival and transfer ability of phylogenetically diverse bacterial endosymbionts in environmental Acanthamoeba isolates. Environ Microbiol Rep 2: 524–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Okude M, Matsuo J, Nakamura S, Kawaguchi K, Hayashi Y, et al. (2012) Environmental chlamydiae alter the growth speed and motility of host acanthamoebae. Microbes Environ 27: 423–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lau HY, Ashbolt NJ (2009) The role of biofilms and protozoa in Legionella pathogenesis: implications for drinking water. J Appl Microbiol 107: 368–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shin S, Roy CR (2008) Host cell processes that influence the intracellular survival of Legionella pneumophila . Cell Microbiol 10: 1209–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jules M, Buchrieser C (2007) Legionella pneumophila adaptation to intracellular life and the host response: clues from genomics and transcriptomics. FEBS Lett 2581: 2829–2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rodríguez-Zaragoza S (1994) Ecology of free-living amoebae. Crit Rev Microbiol 20: 225–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Declerck P (2010) Biofilms: the environmental playground of Legionella pneumophila . Environ Microbiol 12: 557–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nunes A, Borrego MJ, Gomes JP (2013) Genomic features beyond Chlamydia trachomatis phenotypes: What do we think we know? Infect Genet Evol 16: 392–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sixt BS, Heinz C, Pichler P, Heinz E, Montanaro J, et al. (2011) Proteomic analysis reveals a virtually complete set of proteins for translation and energy generation in elementary bodies of the amoeba symbiont Protochlamydia amoebophila . Proteomics 11: 1868–1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Horn M (2008) Chlamydiae as symbionts in eukaryotes. Annu Rev Microbiol 62: 113–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Heath RJ, Rock CO (1996) Regulation of fatty acid elongation and initiation by acyl-acyl carrier protein in Escherichia coli . J Biol Chem 271: 1833–1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Heath RJ, Rock CO (1996) Inhibition of beta-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase III (FabH) by acyl-acyl carrier protein in Escherichia coli . J Biol Chem 271: 10996–11000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zempleni J, Wijeratne SS, Hassan YI (2009) Biotin. Biofactors 35: 36–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Purushothaman S, Annamalai K, Tyagi AK, Surolia A (2011) Diversity in functional organization of class I and class II biotin protein ligase. PLoS One 6: e16850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Haferkamp I, Schmitz-Esser S, Linka N, Urbany C, Collingro A, et al. (2004) A candidate NAD+ transporter in an intracellular bacterial symbiont related to Chlamydiae. Nature 432: 622–6265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schmitz-Esser S, Linka N, Collingro A, Beier CL, Neuhaus HE, et al. (2004) ATP/ADP translocases: a common feature of obligate intracellular amoebal symbionts related to Chlamydiae and Rickettsiae. J Bacteriol 186: 683–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moraes TF, Reithmeier RA (2012) Membrane transport metabolons. Biochim Biophys Acta 1818: 2687–2706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hinz A, Tampé R (2012) ABC transporters and immunity: mechanism of self-defense. Biochemistry 51: 4981–4989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Erkens GB, Majsnerowska M, ter Beek J, Slotboom DJ (2012) Energy coupling factor-type ABC transporters for vitamin uptake in prokaryotes. Biochemistry 51: 4390–4396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Peters J, Wilson DP, Myers G, Timms P, Bavoil PM (2007) Type III secretion à la Chlamydia. Trends Microbiol 15: 241–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Betts-Hampikian HJ, Fields KA (2010) The Chlamydial Type III Secretion Mechanism: Revealing Cracks in a Tough Nut. Front Microbiol 1: 114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dean P (2011) Functional domains and motifs of bacterial type III effector proteins and their roles in infection. FEMS Microbiol Rev 35: 1100–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Greub G, Collyn F, Guy L, Roten CA (2004) A genomic island present along the bacterial chromosome of the Parachlamydiaceae UWE25, an obligate amoebal endosymbiont, encodes a potentially functional F-like conjugative DNA transfer system. BMC Microbiol 4: 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Eugster M, Roten CA, Greub G (2007) Analyses of six homologous proteins of Protochlamydia amoebophila UWE25 encoded by large GC-rich genes (lgr): a model of evolution and concatenation of leucine-rich repeats. BMC Evol Biol 7: 231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Casson CN, Copenhaver AM, Zwack EE, Nguyen HT, Strowig T, et al. (2013) Caspase-11 activation in response to bacterial secretion systems that access the host cytosol. PLoS Pathog 9: e1003400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Luo ZQ (2011) Striking a balance: modulation of host cell death pathways by Legionella pneumophila . Front Microbiol 2: 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Arlehamn CS, Evans TJ (2011) Pseudomonas aeruginosa pilin activates the inflammasome. Cell Microbiol 13: 388–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Aistleitner K, Heinz C, Hörmann A, Heinz E, Montanaro J, et al. (2013) Identification and characterization of a novel porin family highlights a major difference in the outer membrane of chlamydial symbionts and pathogens. PLoS One 8: e55010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Heinz E, Tischler P, Rattei T, Myers G, Wagner M, et al. (2009) Comprehensive in silico prediction and analysis of chlamydial outer membrane proteins reflects evolution and life style of the Chlamydiae. BMC Genomics 10: 634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singer AU, Schulze S, Skarina T, Xu X, Cui H, et al.. (2013) A pathogen type III effector with a novel E3 ubiquitin ligase architecture. PLoS Pathog 2013 9: e1003121, 2013s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Zhu Y, Li H, Hu L, Wang J, Zhou Y, et al. (2008) Structure of a Shigella effector reveals a new class of ubiquitin ligases. Nat Struct Mol Biol 15: :1302–1308, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou JM, Chai J (2008) Plant pathogenic bacterial type III effectors subdue host responses. Curr Opin Microbiol, 11: :179–185, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bierne H, Sabet C, Personnic N, Cossart P (2007) Internalins: a complex family of leucine-rich repeat-containing proteins in Listeria monocytogenes . Microbes Infect 9: 1156–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kobe B, Kajava AV (2001) The leucine-rich repeat as a protein recognition motif. Curr Opin Struct Biol 11: 725–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rikihisa Y, Lin M, Niu H (2010) Type IV secretion in the obligatory intracellular bacterium Anaplasma phagocytophilum . Cell Microbiol 12: 1213–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rikihisa Y, Lin M (2010) Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Ehrlichia chaffeensis type IV secretion and Ank proteins. Curr Opin Microbiol 13: 59–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Al-Khodor S, Price CT, Kalia A, Abu Kwaik Y (2010) Functional diversity of ankyrin repeats in microbial proteins. Trends Microbiol 18: 132–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Huang J, Gogarten JP (2007) Did an ancient chlamydial endosymbiosis facilitate the establishment of primary plastids? Genome Biol 8: R99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Moustafa A, Reyes-Prieto A, Bhattacharya D (2008) Chlamydiae has contributed at least 55 genes to Plantae with predominantly plastid functions. PLoS One 3: e2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Becker B, Hoef-Emden K, Melkonian M (2008) Chlamydial genes shed light on the evolution of photoautotrophic eukaryotes. BMC Evol Biol 8: 203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Price CT, Al-Quadan T, Santic M, Jones SC, Abu Kwaik Y (2010) Exploitation of conserved eukaryotic host cell farnesylation machinery by an F-box effector of Legionella pneumophila . J Exp Med 207: 1713–1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dugan J, Andersen AA, Rockey DD (2007) Functional characterization of IScs605, an insertion element carried by tetracycline-resistant Chlamydia suis . Microbiology 153(Pt 1): 71–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Greub G, Collyn F, Guy L, Roten CA (2004) A genomic island present along the bacterial chromosome of the Parachlamydiaceae UWE25, an obligate amoebal endosymbiont, encodes a potentially functional F-like conjugative DNA transfer system. BMC Microbiol 4: 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Harada T, Tanikawa T, Iwasaki Y, Yamada M, Imai Y, et al. (2012) Phagocytic entry of Legionella pneumophila into macrophages through phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate-independent pathway. Biol Pharm Bull 35: 1460–1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Matsuo J, Oguri S, Nakamura S, Hanawa T, Fukumoto T, et al. (2010) Ciliates rapidly enhance the frequency of conjugation between Escherichia coli strains through bacterial accumulation in vesicles. Res Microbiol 161: 711–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sekizuka T, Yamamoto A, Komiya T, Kenri T, Takeuchi F, et al. (2012) Corynebacterium ulcerans 0102 carries the gene encoding diphtheria toxin on a prophage different from the C. diphtheriae NCTC 13129 prophage. BMC Microbiol 12: 72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, et al. (2008) The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics 9: 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kanehisa M, Goto S (2000) KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 28: 27–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ohtsubo Y, Ikeda-Ohtsubo W, Nagata Y, Tsuda M (2008) GenomeMatcher: a graphical user interface for DNA sequence comparison. BMC Bioinformatics 9: 376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Madej T, Addess KJ, Fong JH, Geer LY, Geer RC, et al.. (2012) MMDB: 3D structures and macromolecular interactions. Nucleic Acids Res 40(Database issue): D461–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55. Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, et al. (2007) Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23: 2947–2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Peterson MW, Colosimo ME (2007) TreeViewJ: An application for viewing and analyzing phylogenetic trees. Source Code Biol Med 2: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Matsuo J, Hayashi Y, Nakamura S, Sato M, Mizutani Y, et al. (2008) Novel Parachlamydia acanthamoebae quantification method based on coculture with amoebae. Appl Environ Microbiol 74: 6397–6404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Phylogenetic analysis of chlamydial 16S rRNA sequences. Bacterial names follow the accession numbers. Arrow denotes Neochlamydia 16S rRNA. The gene accession numbers are as follows: Chlamydia trachomatis D/UW_3/CX, NC_000117.1; Chlamydia trachomatis L2/434/Bu, NC_010287.1; Chlamydia pneumoniae TW-183, NC_005043.1; Simkania Z gsn131, NC_015713.1; Parachlamydia acanthamoebae UV7, NC_015702.1; endosymbiont Acanthamoeba UWC22, AF083616.1; endosymbiont Acanthamoeba TUME1, AF098330.1; Neochlamydia hartmannellae, AF177275.1; Parachlamydia acanthamoebae Bn9, NR_026357.1; Parachlamydia Hall's coccus, AF366365.1; Parachlamydia acanthamoebae Seine, DQ309029.1; Protochlamydia naegleriophila KNic, DQ632609.1.

(TIFF)

Venn diagram showing the numbers of common and unique proteins among three chlamydiae. Red, Chlamydia trachomatis D/UW_3/CX (NC000117.1). Green, Protochlamydia R18 (this study). Blue, Neochlamydia S13 (this study).

(TIFF)

Predicted genes annotated as glycolytic pathway and TCA cycle with pentose phosphate pathway and Entner-Doudoroff pathway. Black lines with arrows show predicted active modules. Gray lines show incomplete modules. Red names with numbers indicate Neochlamydia S13 gene IDs.

(TIFF)

Predicted genes annotated as oxidative phosphorylation pathway. Solid lines with arrows show predicted active modules. Gray lines show incomplete modules. Red names with numbers indicate Neochlamydia S13 gene IDs.

(TIFF)

Predicted genes annotated as fatty acid initiation and elongation. Black lines with arrows show predicted active modules. Red names with numbers indicate Neochlamydia S13 gene IDs.

(TIFF)

Predicted genes annotated as ATP/ADP translocases (NTTs) (A) and ABC transporters (B). Black lines with arrows show predicted active modules. Gray lines show incomplete modules. Red names with numbers indicate Neochlamydia S13 gene IDs.

(TIFF)

Comparison of genes encoding a type III secretion system from Neochlamydia S13 and Protochlamydia UWE25. The type III operon structures of the two chlamydiae are compared. Top panel, T3SS-T1; second panel, T3SS-A1; third panel, T3SS-A2; bottom panel, T3SS-A3. Right scale values show % identity estimated by BLASTp. Each of the gene cluster sequences in Protochlamydia amoebophila UWE25 (NC_005861.1) was obtained from NCBI (http:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome).

(TIFF)

Predicted genes annotated as Sec-dependent type II secretion machinery. Black line with arrow shows predicted active module. Gray boxes show incomplete molecules. Red names with numbers indicate Neochlamydia S13 gene IDs.

(TIFF)

Comparative analysis of genes encoding type IV secretion machinery from Protochlamydia UWE25 and Protochlamydia R18. No annotated type IV genes were found in the Neochlamydia S13 genome. Blue boxes indicate individual coding regions of the type IV cluster.

(TIFF)

Predicted outer membrane structures. Blue molecules were predicted to be active. Gray molecules are absent. Red names with numbers indicate Neochlamydia S13 gene IDs. This figure depicts the predicted outer membrane structure based on a findings described by Heinz et al. [34] and previous findings published by Aistleitner et al. [33].

(TIFF)

Characterization of a unique molecule with ankyrin domains (NEOS13_0151). (A) Detection of ankyrin domains in the molecule encoded by NEOS13_0151. (B) Alignment scores and 3D prediction. The scores and prediction were performed using the web program, protein BLAST with the MMDB (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/MMDB/docs/mmdb_search.html).

(TIFF)

Phylogenetic comparison of the predicted protein sequence encoded by NEOS13_0151 with other eukaryotic proteins. The predicted protein sequence encoded by NEOS13_0151 was phylogenetically compared with previously reported sequences obtained from the GenBank database using ClustalW2. The phylogenetic trees generated from the aligned sequences were constructed by neighbor-joining in ClustalW2, and then visualized with the website viewer.

(TIFF)

Neochlamydia S13 gene IDs with features.

(PDF)

Homologs of eukaryote genes in the Neochlamydia S13 genome encoding predicted LRR-molecules.

(PDF)