Summary

During protoplast regeneration, proteins related to cell morphogenesis, organogenesis and development adjustment were phosphorylated in Physcomitrella patens. These proteins play important roles in regulating postembryonic development in higher plants.

Key words: LC-MS/MS, Physcomitrella patens, phosphoproteome, postembryonic development, protoplast regeneration, TiO2 enrichment.

Abstract

The moss Physcomitrella patens is an ideal model plant to study plant developmental processes. To better understand the mechanism of protoplast regeneration, a phosphoproteome analysis was performed. Protoplasts were prepared from protonemata. By 4 d of protoplast regeneration, the first cell divisions had ensued. Through a highly selective titanium dioxide (TiO2)-based phosphopeptide enrichment method and mass spectrometric technology, more than 300 phosphoproteins were identified as protoplast regeneration responsive. Of these, 108 phosphoproteins were present on day 4 but not in fresh protoplasts or those cultured for 2 d. These proteins are catalogued here. They were involved in cell-wall metabolism, transcription, signal transduction, cell growth/division, and cell structure. These protein functions are related to cell morphogenesis, organogenesis, and development adjustment. This study presents a comprehensive analysis of phosphoproteome involved in protoplast regeneration and indicates that the mechanism of plant protoplast regeneration is similar to that of postembryonic development.

Introduction

Plant leaf mesophyll cells can be separated from their original tissue by cell-wall-degrading enzymes generating a large population of protoplasts that can then become totipotent and hence regenerate whole plants (Zhao et al., 2001). Becoming totipotent involves changes in DNA methylation pattern and increased transcription and reorganization of specific chromosomal subdomains (Zhao et al., 2001; Avivi et al., 2004), changes that are similar to those during embryo development, implying a similar mechanism. Protoplasts are also used to observe cellular processes and activities, such as cell-wall synthesis, cell cycle, and differentiation during regeneration, and hormone responses in various plant species (Sheen, 2001). These cellular processes might be similar to plant postembryonic development.

In plants, postembryonic development is organized by meristems, which both self-renew and produce daughter cells that differentiate and give rise to different organ structures. Mechanisms mediating postembryonic development have been mainly studied in seed plants. It has been established that the cell wall is responsible for organ shape and that the cytoskeleton plays an important role in cell division and expansion. Additionally, cell-cycle regulation is essential for development. Some cell-cycle regulators, such as cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases, are particularly numerous in plants, reflecting the remarkable ability of plants to modulate their development (Inze and De Veylder, 2006).

Organogenesis is a postembryonic process that occurs in a continuous manner throughout the entire lifespan. During organogenesis, organ identity genes play a key role. In the course of shoot propagation, a number of regulators have been identified, including KNOTTED1, SHOOT MERISTEMLESS (STM), KNOTTED-like from Arabidopsis thaliana 2 (KNAT2), and CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON 1 and 2 (CUC1 and CUC2) (Vollbrecht et al., 1991; Long et al., 1996; Pautot et al., 2001; Cary et al., 2002; Gordon et al., 2007). In contrast, for root formation, certain other proteins appear to play dominant roles, including the PINFORMED (PIN) family, transport inhibitor response1 (TIR1), and the Aux/IAA family of transcription factors (Geldner et al., 2001; Rogg et al., 2001; Friml et al., 2002a, b). During organogenesis, DNA methylation, histone methylation and acetylation are important for the enormous variation in cell-type-specific and stage-specific gene expression (Fransz and de Jong, 2002). However, much less is known the molecular mechanism of protoplast regeneration.

The moss Physcomitrella patens has been established as a model system for the study of plant development (Cove et al., 1997; Sakakibara et al., 2003). As with all plants, the form of the moss plant is determined by the pattern of growth and division. Protoplast cultures provide an ideal system for the study of development because following protoplast formation intact plants are produced at high frequency and rapidly. In protoplasts formed from seed plants, the process of regeneration has been associated with numerous events, including dedifferentiation and the loss of photoautotrophic metabolism (Fleck et al., 1980; Vernet et al., 1982; Criqui et al., 1992; Nagata et al., 1994), cell-wall synthesis (Meyer and Abel, 1975), and activation of the cell-cycle machinery (Galbraith et al., 1981, 1983). The cell cycle is regulated by key developmental regulators, which are themselves phosphoregulated (Joubes et al., 2000).

Protein phosphorylation is among the most important post-translational modifications in cells. It underlies many regulatory functions, such as cell-cycle control, receptor-mediated signal transduction, differentiation, and metabolism. For these regulatory functions, eukaryotic cells rely extensively on phosphorylating the hydroxyl group of the side chains of serine, threonine, and tyrosine (Hunter, 1995; Schlessinger, 2000).

Here, phosphoproteomics has been used to increase understanding of the machinery of protoplast regeneration in P. patens. The work examined the global changes in the phosphoproteome following protoplast development using titanium dioxide (TiO2) phosphopeptide enrichment strategies coupled with LC-MS/MS. The study reveals the integration of protoplast regeneration mechanisms in P. patens.

Materials and methods

Plant material and harvesting

P. patens (Hedwig) ecotype ‘Gransden 2004’ was grown in BCDA medium as described (Khandelwal et al., 2010). Protonemata were cultured at 25 °C under a 16/8 light/dark cycle. To produce protoplasts, 7-d-old protonemata were treated for 1h with 0.5% driselase dissolved in 8% mannitol. After filtration and washing, the protoplasts are regenerated on liquid BCDA medium with 8% mannitol under the same culture conditions. Protoplast isolation was repeated three times. For analysis of the next experiment, freshly prepared protoplasts and those cultured for 2 and 4 d were harvested.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis

For fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis, nuclei were stained with 2.86 μM 2-(4-amidinophenyl)-6-indolecarbamidine dihydrochloride (DAPI) and analysed on a two-laser FACStar Plus platform (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA, USA). An argon ion laser tuned to 488nm was used in the laser experiment and a detector with a 530 band pass filter was used for fluorescein isothiocyanate. Software compensation was applied to the collected data using CELLQUEST software (Becton Dickinson).

Protein extraction

Frozen plant material was suspended in 2ml extraction buffer containing 250mM sucrose, 20mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10mM EDTA, 1mM 1,4-dithiothreitol (DTT), and inhibitor cocktail for proteases (Sigma) and phosphatases (Sigma). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 8000 g for 10min at 4 °C. Supernatants were transferred to clean tubes and centrifuged at 120 000 g for 1h at 4 °C. The final supernatants were used for soluble protein extraction, as described previously (Wang et al., 2009). The pellets (membrane-associated proteins) were re-precipitated with acetone overnight at –20 °C. The precipitated membrane proteins were rinsed three times with ice-cold acetone containing 13mM DTT and subsequently lyophilized. Finally, both protein pellets were resuspended separately by adding 8M urea, 4% CHAPS, 65mM DTT, and 40mM Tris (pH 7.5). The protein concentration was determined according to Peterson (1977) using BSA as a standard. The supernatants were stored in aliquots at –80 °C or directly digested with trypsin.

Tryptic digestion and phosphopeptide purification

The tryptic digestion was processed as described previously (Dai et al., 2005). In brief, 500 μg of each protein sample (100 μl volume) were reduced with 20mM DTT at 37 °C for 2.5h and alkylated with 100mM iodoacetamide for 40min at room temperature in the dark. After that, the protein mixtures were spun and exchanged into 100mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer (pH 8.5), and then incubated at 37 °C for 16h with trypsin at an enzyme/substrate ratio of 1:50 (w/w) to produce a proteolytic digest. Finally, the digested peptide mixture was lyophilized and then diluted in a loading buffer containing 1M glycolic acid in 65% acetonitrile (ACN) and 2% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA).

Phosphopeptide purification was performed using TiO2 microcolumns (320 μm×50mm, Column Technology, Freemont, CA, USA; Thingholm and Larsen, 2009). The microcolumns were rinsed with 100 μl loading buffer and the samples (200 μl) were subsequently loaded by applying air pressure. After loading the sample onto the microcolumn, the columns were subsequently washed with 100 μl loading buffer, 100 μl washing buffer I (65% ACN and 0.5% TFA), and 100 μl washing buffer II (65% ACN and 0.1% TFA). The bound peptides were eluted with 100 μl elution buffer (300mM ammonium water and 50% ACN). The elution was acidified by adding 5 μl 100% formic acid prior to the desalting step.

Nano-LC/MS/MS analysis

Peptide separation was performed on a surveyor liquid chromatography system (Thermo Finnigan, San Jose, CA, USA), consisting of a degasser, MS pump, and autosampler and equipped with a C18 trap column (RP, 320 μm×20mm, Column Technology) and an analytical C18 column (RP, 75 μm×150mm, Column Technology). After sample loading, the column was washed for 30min with 98% mobile phase A (0.1% formic acid in water) to flush off remaining salt. Peptides were eluted using a linear gradient of increasing mobile phase B (0.1% formic acid in ACN) from 2 to 35% in 120min. A linear ion trap/Orbitrap hybrid mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher, San Jose, CA, USA) equipped with a NSI nanospray source was used for the MS/MS experiment. Spray voltage applying to the Nano needle was 1.85kV and ion transfer capillary temperature was 160 °C. Normalized collision energy for collision-induced dissociation was 35%. The number of ions stored in the ion trap was regulated by the automatic gain control. The instrument method consisted of one full MS scan from 400 to 2000 m/z followed by data-dependent MS/MS scan of the 10 most-intense ions from the MS spectrum with the following dynamic exclusion settings: repeat count of 2, repeat duration 30 s, exclusion duration 1.5min. The resolution of the Orbitrap mass analyser was set at 100 000 (m/Δm 50% at m/z 400) for the precursor ion scans.

Protein assignment

The strategy for identifying phosphorylated proteins in P. patens was as follows. The MS/MS spectra files from each LC run were centroided and merged to a single file using the TurboSEQUEST program in the BioWorks 3.2 software suite (Thermo Electron), and then the MS/MS spectra were searched against the NCBI A. thaliana and P. patens combined protein database (including normal and reversed) with carbamidomethylcysteine as a fixed modification. Oxidized methionine and phosphorylation (serine, threonine, and tyrosine) were searched as variable modifications. The searches were performed with tryptic specificity allowing one missed cleavage and the precursor ion m/z tolerances of 50 ppm and fragment ion m/z tolerances of ±1Da. Cysteine residues were searched as a fixed modification by 57.02146Da because of carboxyamidomethylation. Oxidation was set as a variable modification on methionine (15.99492Da). Dynamic modifications were permitted to allow for the detection of phosphorylated serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues (+79.96633). The phosphoric acid neutral loss peaks of serine and threonine was about –18.01056Da.

To provide high-confidence phosphopeptide sequence assignments, an accepted SEQUEST result had to have a ΔC n score of at least 0.1 (regardless of charge state). Peptides with a +1 charge state were accepted if they were fully digested and had a cross correlation (Xcorr) of at least 1.9. Peptides with a +2 charge state were accepted if they had a Xcorr ≥2.2. Peptides with a +3 charge state were accepted if they had a Xcorr ≥3.3. All output results were filtered and combined together using BuildSummary software to delete the redundant data (Tabb et al., 2002). All identified proteins (whether phosphorylated or not) were calculated separately and filtered by precursor ion tolerance m/z of 10 ppm and 1.0% false-positive rate (Elias and Gygi, 2007). The false-positive rate (FPR) was calculated as: FPR = 2[N rev/(N rev + N for)], where N rev is the number of hits to the ‘reverse’ peptide and N for is the number of hits to the ‘forward’ peptide. The proteins were classified to a protein group if the same peptides were assigned to multiple proteins after false peptides were filtered. A further manual check removed phosphopeptides with unclear MS/MS spectra.

For phosphorylation site identification, first a stricter peptide identification criteria (FPR≤0.01) was set. Second, a modified site was considered to be unique only when the corresponding modified peptides had a ΔC n >0.1 because a ΔC n >0.1 is significant for discriminating the first (top) candidate peptide from the second candidate peptide (Deng et al., 2010). In addition, this work checked the phosphoric acid neutral loss peaks for phosphorylation site identification (Ballif et al., 2004).

Analysis of gene expression by real-time reverse-transcription PCR

Total RNA was extracted using a RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). After extraction, RNA samples were treated with DNase (Ambion, USA). First-strand cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using a iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The P. patens actin3 cDNA gene was used as a standard to normalize the content of cDNA. Real-time reverse-transcription PCR was performed using gene-specific primers for phosphoproteins in the P. patens protein database and phosphoproteins in the A. thaliana protein database that had genes homologous to those in the P. patens database (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2, respectively, available at JXB online) on a Rotor Gene 3000 Real-Time Thermal Cycler (Corbet Research, Australia). SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Perfect Real Time) kit and reverse-transcription PCR reagents (Takara Bio) were used for quantification of differentially expressed gene sequences.

Results

Protoplast cell-cycle phase

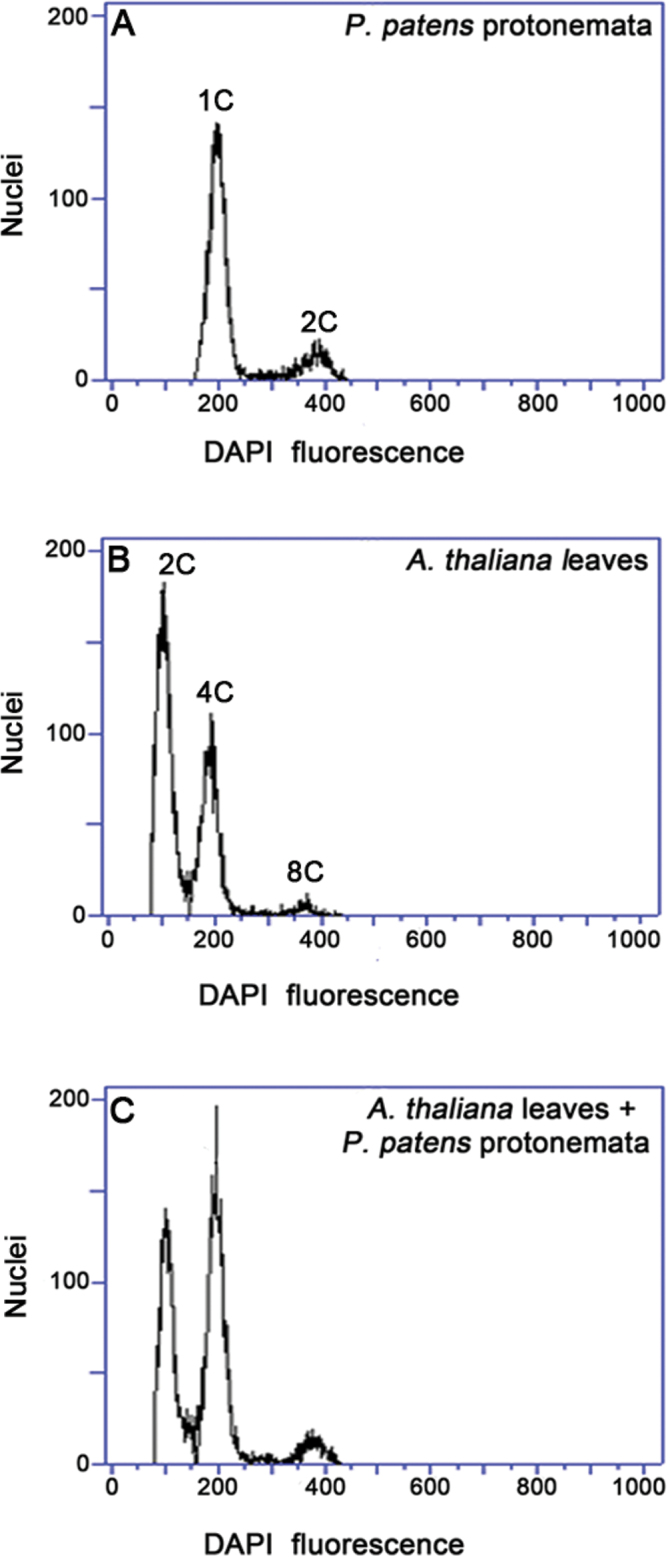

To identify the phase of the cell cycle for cells in P. patens protonemata, the DNA content of protonemata cell nuclei was measured with FACS. The standard phase of cell cycle was determined using nuclei from A. thaliana leaves. The nuclei from A. thaliana had three peaks and two peaks from P. patens, and the second peak in A. thaliana has approximately the same relative fluorescence value as that of P. patens protonemata in the first peak (Fig. 1A and B). The A. thaliana genome size is 125Mb and the leaves are diploid. The P. patens protonemata are haploid and its genome size is 490Mb. The nuclei in the second peak of A. thaliana leaves are in G2 phase (4C, 500Mb; Fig. 1B). So, it was speculated that the nuclei from P. patens protonemata were in G1 phase (1C, 490Mb; Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Identification of cell-cycle phases. Nuclei were prepared from Physcomitrella patens protonemata (A) and Arabiposis thaliana leaves (B) or a mixture of nuclei from both species (C), stained with DAPI, and subjected to FACS analysis.

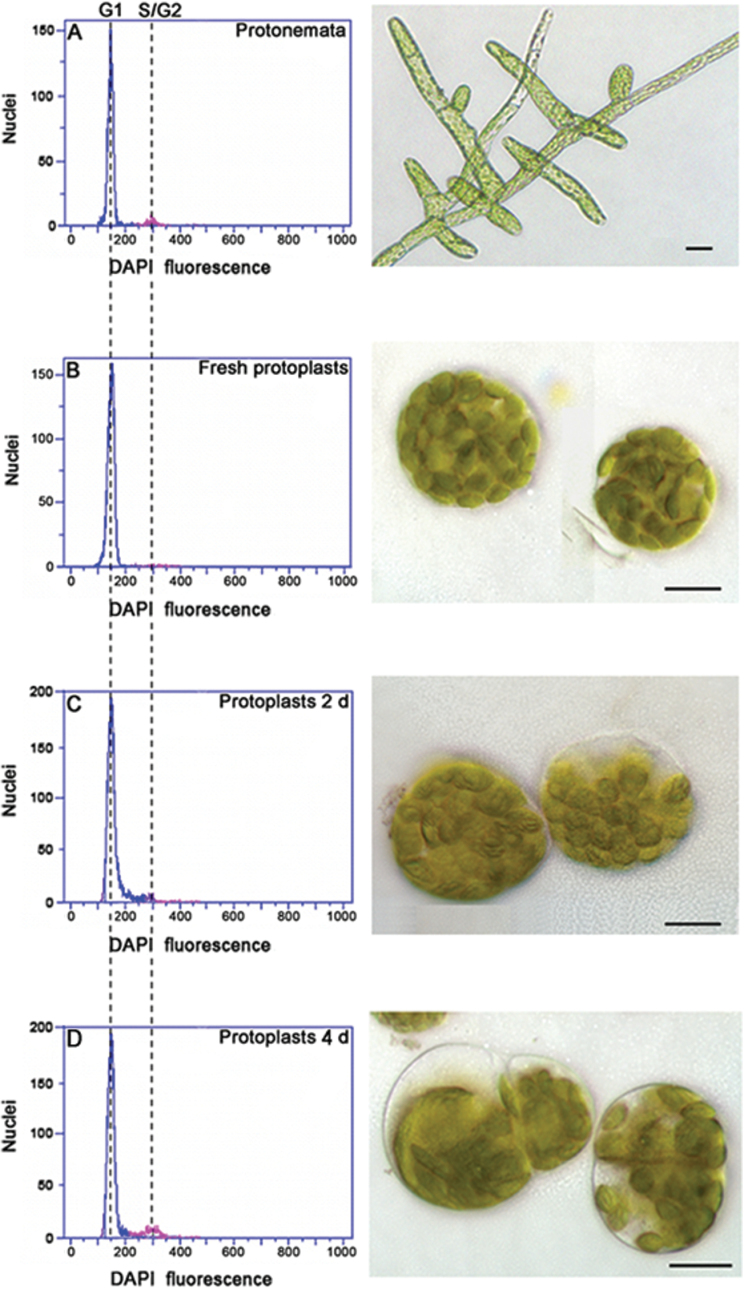

To investigate how P. patens protoplasts regenerate, 7-d-old protonemata were used to establish an efficient and reproducible ‘protoplast system’. FACS analysis showed that most protonemal nuclei (92%) had a DNA content corresponding to G1 phase and a small peak (8%) was present at a S/G2 level (Fig. 2A), whereas nearly 100% of the nuclei from freshly harvested protoplasts had a G1 level of DNA (Fig. 2B). This is consistent with previous report. Tobacco leaves were treated with cell-wall-degrading enzymes to produce a large population of protoplasts, which had a DNA content corresponding to G1 phase (Zhao et al., 2001). Fresh protoplasts appeared round and green. By 2 d of regeneration, the new polar axes were established and protoplasts with a S/G2 level of DNA were present (constituting about 8% of the population; Fig. 2C). By 4 d, asymmetric cell divisions were common and protoplasts with a S/G2 DNA content constituted about 13% of the population (Fig. 2D). Subsequently, the cultures were transferred to a regeneration medium (BCDA medium) for formation of protonemata.

Fig. 2.

Protoplast regeneration and the cell cycle. (A) Protonemata. (B) Protoplasts. (C) Protoplasts after regeneration for 2 d. (D) Protoplasts after regeneration for 4 d. Nuclei were isolated from Physcomitrella patens protonemata or protoplasts at the indicated times, stained with DAPI, and subjected to FACS analysis. Bright-field images show representative cells. Bars, 20 μm.

Phosphopeptide enrichment and LC-MS/MS identification

To analyse the P. patens phosphoproteome, this work used a TiO2 phosphopeptide enrichment strategy in combination with LC-MS/MS for identification. The resulting data were analysed using the TurboSEQUEST program in the BioWorks 3.2 software suite. From the three treatments altogether, more than 2000 phosphoproteins were identified (data not shown). This work focused on phosphoproteins in protoplasts regenerated for 4 d. There were more than 300 of these expressed in protoplasts regenerated for 4 d which were not present in fresh protoplasts or those regenerated for 2 d. Of this group of unique phosphoproteins, 108 of them were functional annotation proteins and others are predicted proteins. These 108 phosphoproteins were chosen for further analysis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Phosphoproteins in Physcomitrella patens unique to protoplast regenerated 4 d* indicates methionine oxidation; # indicates phosphorylation sites.

| Metabolic group | Protein no. | Theoretical mass (kDa) | Theoretical pI | Accession no. | Description | Subcellular localization | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolism (19.44%) | C1 | 32.1 | 5.05 | NP_194311 | XTR6 probable xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/ hydrolase protein 23 | Cell wall | M*Y#S#SLWNAEEWATR |

| C2 | 61.9 | 9.08 | NP_187947 | Sks11 (SKU5 Similar 11); copper ion binding/oxidoreductase | Membrane | NCWQDGT#PGT#MCPIMPGT#NYTYHFQPK | |

| C3 | 116.4 | 5.96 | NP_172637 | ATSS3 (starch synthase 3); starch synthase/transferase, transferring glycosyl groups | Chloroplast | DS#NATST#ATNEVSGISK | |

| C4 | 42.2 | 5.5 | NP_001031705 | CORI3 (CORONATINE INDUCED 1); cystathionine beta-lyase/transaminase | Apoplast | FSSIVPVVT#LGSISK | |

| C5 | 152.4 | 5.77 | NP_193817 | TPP2 (TRIPEPTIDYL PEPTIDASE II); tripeptidyl-peptidase | Unknown | VLDVIDCT#GSGDIDTST#VVK | |

| C6 | 72.1 | 6.31 | Q8RXN5 | tRNA wybutosine-synthesizing protein 1 homologue | Unknown | CMET#T#PS#LACANK | |

| C7 | 44.0 | 7.54 | NP_568193 | AtAGAL2 (Arabidopsis thaliana ALPHA-GALACTOSIDASE 2); alpha-galactosidase/catalytic/hydrolase, hydrolysing O-glycosyl compounds | Cell wall | FIAFT#LTITLT#QIADGFQS#R | |

| C8 | 61.5 | 8.93 | NP_196950 | Pseudouridine synthase/transporter | Chloroplast | GET#VELS#PR | |

| C9 | 7.04 | 6.05 | Q9C6T3 | Terpene synthase family protein, putative | Membrane | LIHLLVS#M*GISYHFDK | |

| C10 | 66.6 | 6.63 | NP_191966 | Malate oxidoreductase, putative | Mitochondrion | MAGIS#ES#EATK | |

| C11 | 87.6 | 6.37 | Q9FZI2 | Lupeol synthase 5 | Unknown | CCMLLS#T#M*PTDITGEK | |

| C12 | 38.3 | 4.61 | NP_849593 | Lipid-binding serum glycoprotein family protein | Membrane | DQIGS#SVEST#IAK | |

| C13 | 40.1 | 8.87 | NP_196027 | Short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR) family protein | Unknown | FNHS#HT#PVCVITGAT#SGLGK | |

| C14 | 60.2 | 8.74 | Q8W033 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase family 3 member I1 | Chloroplast | LFS#EYLDNTT#IR | |

| C15 | 79.9 | 6.12 | NP_566041 | Transketolase, putative | Chloroplast | S#IGIDT#FGASAPAGK | |

| C16 | 45.8 | 5.12 | NP_196694 | Monooxygenase family protein | Membrane | S#SEPPVGSPT#GAGLGLDPQAR | |

| C17 | 52.3 | 5.6 | Q9C7Z9 | Serine carboxypeptidase-like 18 | Membrane | T#EGYNGGLPSLVSTSYS#WTK | |

| C18 | 39.7 | 5.27 | NP_197540 | Oxidoreductase, 2OG-Fe(II) oxygenase family protein | Unknown | SLELEENSFLDM*Y#GESATLDT#R | |

| C19 | 25.8 | 8.79 | Q8VY52 | PsbP domain-containing protein 2 | Chloroplast | FFCFAQNPS#S#TVSINLSK | |

| C20 | 134.7 | 7.39 | NP_196999 | GMII (GOLGI ALPHA-MANNOSIDASE II); alpha-mannosidase | Golgi apparatus | PLNDS#NS#GAVVDITT#K | |

| C21 | 57.6 | 9.09 | NP_193230 | ATAO1 (ARABIDOPSIS THALIANA AMINE OXIDASE 1); amine oxidase/copper ion binding | Cell wall | VGVDLT#GVLEVK | |

| Transcription (22.22%) | C22 | 62.5 | 7.72 | NP_192756 | Light-mediated development protein DET1 | Nucleus | FGLFATSTAQIHDSS#SPS#NDAVPGVPS#IDK |

| C23 | 137.4 | 9.28 | NP_568624 | COP1-interacting protein-related | Membrane | VYT#LETEIIQIK | |

| C24 | 102.4 | 8.35 | EDQ54570.1 | Trithorax-like protein, histone–lysine N-methyltransferase | Nucleus | TDCLTY#QPPVT#S#SGCAR | |

| C25 | 70.3 | 4.44 | EDQ52478.1 | Paf1 complex protein | Nucleus | GLSPGY#LEDALEEEDEPDQYDR | |

| C26 | 110.5 | 4.91 | EDQ60631.1 | Putative histone deacetylase complex, SIN3 component | Nucleus | FM*QVLY#GLLDGSVDNSK | |

| C27 | 72.4 | 8.63 | NP_181971 | DNA-binding bromodomain-containing protein | Nucleus | SMNESNST#ATAGEEER | |

| C28 | 35.6 | 4.91 | P46640 | KNAT2 homeobox protein knotted-1-like 2 | Nucleus | AEDNFS#LSVIK | |

| C29 | 59.9 | 6.96 | NP_199123 | APUM13 (Arabidopsis Pumilio 13); RNA binding/binding | Nucleus | IMDAISSVALQLT#R | |

| C30 | 29.5 | 8.75 | EDQ59312.1 | Type I MADS-domain protein PPTIM4 | Nucleus | MS#TT#TSPPALT#VK | |

| C31 | 114.8 | 8.71 | NP_173522 | Squamosa promoter-binding-like protein 14 | Nucleus | GLDLNLGS#GLT#AVEETTTTTQNVR | |

| C32 | 40.2 | 5.70 | NP_198791 | AGL81 (AGAMOUS-LIKE 81); transcription factor | Nucleus | CSSS#SSS#SSYSLASTSLSNR | |

| C33 | 19.9 | 6.21 | NP_001078798 | AGL31 (AGAMOUS LIKE MADS-BOX PROTEIN 31); transcription factor | Unknown | TS#LEANSS#VDTQ | |

| C34 | 64.9 | 5.02 | NP_179283 | AMS (ABORTED MICROSPORES); DNA binding/transcription factor | Nucleus | LMEALDS#LGLEVT#NANTTR | |

| C35 | 176.3 | 5.65 | EDQ61350.1 | SNF2 family DNA-dependent ATPase | Nucleus | S#PENGS#PAQEYDSPS#R | |

| C36 | 108.1 | 6.84 | NP_564568 | SNF2 domain-containing protein/helicase domain-containing protein/RING finger domain-containing protein | Nucleus | LDGT#MS#LIAR | |

| C37 | 200.2 | 8.50 | EDQ61497.1 | SNF2 family chromodomain-helicase | Nucleus | NY#QEEGVTWLDHNFENR | |

| C38 | 102.1 | 9.52 | EDQ66080.1 | Argonaute family member | Unknown | LMSPLEGGSTTS#SS#SS#R | |

| C39 | 42.5 | 5.40 | NP_179397 | VND1 (VASCULAR RELATED NAC-DOMAIN PROTEIN 1); transcription factor | Unknown | FVASQLMS#QEDNGTS#SFAGHHIVNEDK | |

| C40 | 34.6 | 5.47 | NP_190248 | PCL1 (PHYTOCLOCK 1); DNA binding/transcription factor | Unknown | FGSMAS#Y#PSVGGGS#ANEN | |

| C41 | 263.8 | 5.34 | NP_171710 | Transcriptional regulator-related | Membrane | ETGT#SLQTLT#SAATM*ER | |

| C42 | 67.5 | 8.98 | NP_175971 | Transcription factor-related | Unknown | HFWSSY#PITTT#Y#LHTK | |

| C43 | 42.8 | 5.39 | NP_566737 | S1 RNA-binding domain-containing protein | Chloroplast | DT#S#DEASAAGPSDWK | |

| C44 | 36.5 | 6.91 | NP_188063 | CID9 (CTC-interacting domain 9); RNA binding/protein binding | Unknown | NFFES#ACGEVTR | |

| C45 | 38.2 | 8.81 | NP_567159 | DNA-binding storekeeper protein-related | Nucleus | T#LNS#PSAAVAVSDDSES#EK | |

| C46 | 36.8 | 8.33 | NP_174084 | CYCT1;3 (CYCLIN T 1;3); cyclin-dependent protein kinase | Nucleus | NVSLFESPQCET#S#K | |

| Signal transduction (12.96%) | C47 | 71.7 | 6.43 | Q8H0V1 | CDK5RAP1-like protein | Unknown | AT#HAS#SS#SSSALLPR |

| C48 | 49.6 | 6.37 | NP_568248 | CYC3B (MITOTIC-LIKE CYCLIN 3B FROM ARABIDOPSIS); cyclin-dependent protein kinase regulator | Nucleus | WT#LDQTDHPWNPT#LQHYTR | |

| C49 | 39.2 | 9.11 | Q9C9M7 | CAK4 cyclin-dependent kinase d-2 | Cytoplasm | T#IFPM*AS#DDALDLLAK | |

| C50 | 134.2 | 6.53 | NP_199264 | TAO1 (TARGET OF AVRB OPERATION1); ATP binding/protein binding/transmembrane receptor | Membrane | QFLVDT#EDICEVLTDDT#GT#R | |

| C51 | 20.3 | 6.59 | EDQ82848.1 | Arf6/ArfB family small GTPase | Unknown | NVNFT#VWDVGGQDK | |

| C52 | 33.5 | 5.72 | NP_200984 | ATIPK2BETA; inositol or phosphatidylinositol kinase/inositol trisphosphate 6-kinase | Nucleus | LPHLVLDDVVSGY#ANPS#VM*DVK | |

| C53 | 21.9 | 6.84 | EDQ74392.1 | Sar1 family small GTPase | Unknown | M*GY#GEGFK | |

| C54 | 188.8 | 5.47 | NP_195533 | Guanine nucleotide exchange family protein | Chloroplast | T#ALGPPPGSS#T#ILSPVQDITFR | |

| C55 | 52.5 | 6.11 | NP_001031307 | NHO1 (nonhost resistance to P. s. phaseolicola 1); carbohydrate kinase/glycerol kinase | Unknown | AVLES#M*CFQVK | |

| C56 | 109.4 | 5.43 | NP_849957 | AtRLP19 (receptor-like protein 19); kinase/protein binding | Membrane | LTGTLPSNMSSLS#NLK | |

| C57 | 75.5 | 9.02 | NP_565976 | TTL3 (TETRATRICOPETIDE-REPEAT THIOREDOXIN-LIKE 3); binding/protein binding | Unknown | GSASSSAAATPTS#SSGS#SGSAS#GK | |

| C58 | 21.9 | 6.10 | NP_172390 | ATSARA1A (ARABIDOPSIS THALIANA SECRETION-ASSOCIATED RAS SUPER FAMILY 1); GTP binding | Chloroplast | M*GY#GEGFK | |

| C59 | 22.6 | 9.41 | NP_196631 | Aminoacyl-tRNA hydrolase/protein tyrosine phosphatase | Unknown | FTTAS#PS#M*SQQTGEIDAVVDASSAEK | |

| Transport (10.19%) | C60 | 96.9 | 6.92 | Q38998 | Potassium channel AKT1 | Membrane | S#WFLLDLVSTIPSEAAM*R |

| C61 | 19.7 | 8.86 | NP_175324 | Plastocyanin-like domain-containing protein | Membrane | VMEVESTPQSPPPS#S#SLPAS#AHK | |

| C62 | 50.2 | 5.65 | NP_198698 | Amino acid transporter-like protein | Membrane | IMLQVS#ILVSNIGVLIVYM*IIIGDVLAGK | |

| C63 | 106.9 | 5.62 | NP_201066 | Transportin-SR-related | Nucleus | LDTVTYS#LLALTR | |

| C64 | 46.5 | 9.7 | NP_001078720 | APE2 (ACCLIMATION OF PHOTOSYNTHESIS TO ENVIRONMENT 2); antiporter/triose-phosphate transmembrane transporter | Chloroplast | QFS#TAS#SSSFS#VK | |

| C65 | 53.5 | 6.36 | Q6AWX0 | d-xylose-proton symporter-like 2 | Membrane | M*ALDPEQQQPISSVS#R | |

| C66 | 25.6 | 5.24 | Q9SP35 | Mitochondrial import inner membrane translocase subunit Tim17 | Membrane | EDPWNS#IIAGAATGGFLSMR | |

| C67 | 84.6 | 9.29 | Q9S9N5 | Putative cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel 7 | Membrane | FVS#S#GETEWIK | |

| C68 | 116.2 | 8.17 | EDQ55253.1 | Na+ P-type-ATPase | Membrane | INMVY#SS#T#TVAK | |

| C69 | 98.2 | 5.34 | NP_195035 | APM1 (AMINOPEPTIDASE M1); aminopeptidase | Membrane | MLQSY#LGAEVFQK | |

| C70 | 117.7 | 6.91 | NP_566869 | CEF (clone eighty-four); protein binding/transporter/zinc ion binding | COPII vesicle coat | T#FVGIATFDS#TIHFYNLK | |

| Cell growth/division (7.41%) | C71 | 137.2 | 6.45 | EDQ50619.1 | Condensin complex component SMC3 | Nucleus | AEMET#QLVDS#LTPEQR |

| C72 | 77.6 | 8.87 | NP_850846 | Kelch repeat-containing protein | Cytoplasm | S#SS#SAVLTSDES#VK | |

| C73 | 102.7 | 6.19 | NP_567236 | PMS1 (POSTMEIOTIC SEGREGATION 1); ATP binding/mismatched DNA binding | Nucleus | MQGDSS#PSPTT#TS#SPLIR | |

| C74 | 50.3 | 6.58 | NP_199003 | POLA3; DNA primase | Unknown | MDVDDDDS#DS#SLLGK | |

| C75 | 58.0 | 9.61 | P40602 | Anter-specific proline-rich protein APG | Unknown | NDIDSYT#TIIADSAAS#FVLQLY#GYGAR | |

| C76 | 82.7 | 7.60 | NP_194589 | NPGR2 (no pollen germination related 2); calmodulin binding | Membrane | DY#NGSSALST#AES#ENAK | |

| C77 | 34.5 | 6.76 | NP_564689 | Embryo-abundant protein-related | Unknown | FDT#NCVVT#TLK | |

| C78 | 16.3 | 9.38 | NP_564332 | SAUR68 (SMALL AUXIN UPREGULATED 68) | Unknown | S#NVFTS#SSS#TVEK | |

| Cell structure (9.26%) | C79 | 108.8 | 8.62 | NP_198947 | Kinesin-like protein | Microtubule associated complex | INVLETLASGT#TDENEVR |

| C80 | 98.7 | 9.34 | Q9FJX6 | Formin-like protein 6 | Membrane | EEVS#EALT#DGNPESLGAELLET#LVK | |

| C81 | 80.1 | 8.41 | NP_189792 | Myosin heavy chain-related | Unknown | ET#TGSVPFPS#VGGSR | |

| C82 | 106.3 | 5.60 | NP_567048 | VLN3 (VILLIN 3); actin binding | Unknown | LY#S#IADGQVESIDGDLSK | |

| C83 | 56.8 | 11.32 | NP_566340 | Proline-rich family protein | Unknown | GTSPSPTVNS#LS#K | |

| C84 | 20.0 | 6.16 | Q9SIX3 | Putative glycine-rich RNA-binding protein | Unknown | GGMVGGYGS#GGY#R | |

| C85 | 128.9 | 8.51 | NP_194467 | VIIIB; motor | Chloroplast | Y#S#QDLIY#SK | |

| C86 | 89.2 | 7.24 | NP_192428 | ATK5 (ARABIDOPSIS THALIANA KINESIN 5); microtubule motor | Mitochondrion | T#LM*FVNISPDPS#STGESLCSLR | |

| C87 | 82.9 | 4.84 | Q8L838 | Conserved oligomeric Golgi complex subunit 4 | Membrane | SCLSELGELS#S#T#FK | |

| C88 | 135.5 | 6.51 | NP_174461 | Actin binding | Unknown | S#GLS#TEMVYSMS#DK | |

| Protein destination and storage (6.48%) | C89 | 75.8 | 8.99 | NP_187752 | DNAJ heat shock N-terminal domain-containing protein/cell division protein-related | Unknown | EY#VPSFNS#Y#ANK |

| C90 | 105.5 | 5.55 | Q9LV01 | ETO1-like protein 2 | Unknown | LASS#LGHVYS#LAGVS#R | |

| C91 | 28.3 | 9.39 | NP_196816 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase CYP20–2 | Chloroplast | MAT#LS#M*TLSNPK | |

| C92 | 74.0 | 7.57 | NP_192255 | Ankyrin repeat family protein | Unknown | TMWQHSNNGS#S#STS#TLASK | |

| C93 | 46.9 | 9.73 | NP_566289 | PAPA-1-like family protein/zinc finger (HIT type) family protein | Chloroplast | T#LQT#NSEAGTYTK | |

| C94 | 32.1 | 9.42 | NP_199935 | Ubiquinol-cytochrome C chaperone family protein | Mitochondrion | Y#GY#ATVAPAAADPPSQK | |

| C95 | 67.4 | 4.47 | NP_191403 | Meprin and TRAF homology domain-containing protein/MATH domain-containing protein | Unknown | ET#VDINGFVVVSS#K | |

| Defence (5.56%) | C96 | 22.8 | 9.30 | Q8LEQ3 | Nectarin-like protein | Secreted protein | DS#TQIT#PEDFYFK |

| C97 | 29.7 | 9.54 | NP_178377 | WHY3 (WHIRLY 3); DNA binding | Nucleus | FGDS#S#S#SQNAEVSSPR | |

| C98 | 145.4 | 5.64 | NP_176378 | Galactolipase/phospholipase | Unknown | IIVFS#GTFGPTQAVVK | |

| C99 | 17.8 | 5.01 | NP_189276 | Major latex protein-related/MLP-related | Unknown | MAT#SGT#Y#VTQVPLK | |

| C100 | 62.6 | 8.9 | NP_001117315 | Jacalin lectin family protein | Unknown | PSS#PHNAIVPHNNSGT#AQIENS#PWANK | |

| C101 | 48.9 | 6.08 | O80998 | Myrosinase-binding protein-like | Unknown | VFGS#ES#SVIVMLK | |

| Protein synthesis (3.70%) | C102 | 55.6 | 9.10 | NP_186876 | eIF4-gamma/eIF5/eIF2-epsilon domain-containing protein | Unknown | IFT#HEIS#S#CYASR |

| C103 | 28.4 | 5.44 | NP_194797 | MA3 domain-containing protein | Unknown | FT#LSSSS#DLTNGGDAPS#FAVK | |

| C104 | 50.9 | 5.35 | NP_851097 | HCF109 (HIGH CHLOROPHYLL FLUORESCENT 109); translation release factor/translation release factor, codon specific | Chloroplast | Y#TLAMAS#AVTN | |

| C105 | 11.2 | 6.01 | NP_001031319 | LCR82 Putative defensin-like protein 86 | Membrane | CY#STPECNAT#CLHEGY#EEGK | |

| Unknown (2.78%) | C106 | 56.4 | 5.60 | NP_201248 | Octicosapeptide/Phox/Bem1p (PB1) domain-containing protein | Chloroplast | FS#Y#NS#YPDSTDSSPR |

| C107 | 21.4 | 5.44 | NP_172268 | LOB domain-containing protein 1 | Mitochondrion | S#DASVATTPIISSSSSPPPS#LS#PR | |

| C108 | 30.1 | 9.32 | NP_195061 | Chloroplast inner membrane import protein Tic22, putative | Chloroplast | SGTPTTT#LSPS#LVAK |

Phosphorylation site identification

Protein phosphorylation in eukaryotes predominantly occurs on serine and threonine residues, whereas phosphorylation on tyrosine residues is less abundant. As expected, the serine and threonine phosphorylation sites were predominant among the phosphoproteins associated with the protoplasts regenerated for 4 d (Table 1). Tyrosine phosphorylation accounted for nearly 12.5% of all phosphorylation events, a proportion that is nearly identical to that reported previously for protonemata (13%) of P. patens (Heintz et al., 2006). In contrast, for A. thaliana, phosphorylation on tyrosine residues was reported to constitute only 4.3% of protein phosphorylation events (Sugiyama et al., 2008), and for animal cells (2–3%) and yeast (<1%), tyrosine phosphorylation is even less (de la Fuente van Bentem and Hirt, 2009). Evidently, the moss has a high ratio of tyrosine phosphorylation compared to other eukaryotes but the reason for this remains to be determined. Additionally, this work found tyrosine phosphorylation in multiple phosphorylated peptides, results that are similar to those for A. thaliana (Sugiyama et al., 2008).

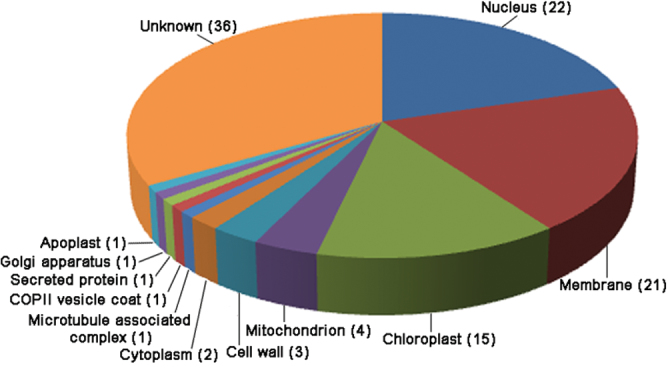

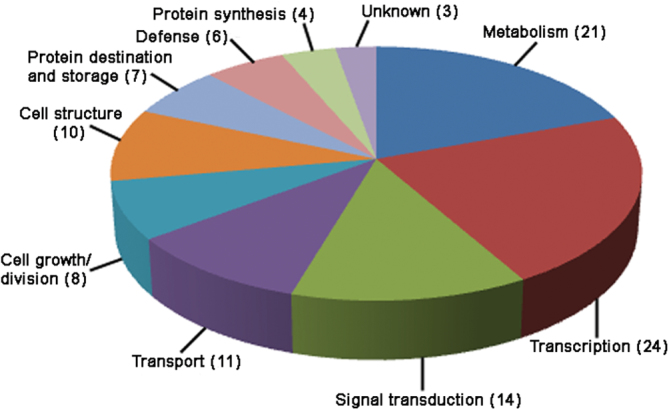

Predicted localization and categorization of phosphoproteins

The 108 phosphoproteins identified from the 4-d culture were categorized by cellular location, based on annotation within the NCBI database, and by function, based on the EU A. thaliana genome project (Bevan et al., 1998). The majority of the proteins were predicted to be located in membrane, nucleus, and chloroplast (Table 1 and Fig. 3). As for putative function, proteins could be sorted into 10 categories (Table 1 and Fig. 4), with more than half of the proteins being involved in transcription, signal transduction, growth/division, and structure.

Fig. 3.

Annotated subcellular localization of phosphoproteins, showing the percentage of the 108 phosphoproteins that were specific to 4 d of regeneration in each category. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of phosphoproteins in each subcellular localization. Localization was based on the NCBI database.

Fig. 4.

Annotated functional categorization of phosphoproteins, showing the percentage of the 108 phosphoproteins that were specific to 4 d of regeneration in each category. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of phosphoproteins in each functional category. Function was based on the EU Arabiposis thaliana genome project.

Phosphoproteins involved in cell-wall metabolism and cytoskeleton structure

Among the collection of identified phosphoproteins were several involved in cell-wall metabolism, arguably one of the characteristic metabolic processes of protoplast regeneration. This work identified a xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase (XTHs, C1) and a copper-binding oxidoreductase related to A. thaliana SKU5 (C2), proteins that have been previously implicated in cell-wall-loosening and expansion (Campbell and Braam, 1999; Sedbrook et al., 2002). This work also identified structural cell-wall proteins, including a proline-rich family protein (C83) and a glycine-rich protein (C84) although the NCBI database does not assign either to a cell-wall location.

The identified phosphoproteins included several that are cytoskeletal. These include two members of the kinesin superfamily (C79, C86), a formin-like protein (C80), and a myosin heavy chain (C81). Kinesins are microtubule-based motors, formin is involved in the organization of the actin cytoskeleton, and myosin is a motor protein that drives actin-dependent motility.

Phosphoproteins involved in signal transduction

At 4 d after protoplast formation, 14 proteins were categorized within the signal transduction group. Among these proteins, four are heterodimeric serine/threonine protein kinases. These kinases comprise a catalytic subunit, termed cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK, C46, C47), an activating subunit (CDK-activating kinase, CAK, C49), and a cyclin (C48). In addition, two proteins are putatively involved in signalling to the cytoskeleton. One of them is a putative homologue of TAO-1 (C50), a protein that, regulates microtubule dynamics and checkpoint signalling during mitotic progression (Draviam et al., 2007), and the other is annotated as a small GTPase of the Arf6/ArfB family (C51), which is well known to regulate actin cytoskeletal organization in animals and fungi (Myers and Casanova, 2008), although apparently not studied in plants.

Phosphoproteins associated with transcription

Among the 108 phosphoproteins, 24 of them were associated with transcription. Interestingly, the putative function of many of these transcription factors developmental. These identified transcription factors include putative homologues of the following proteins: A. thaliana DE-ETIOLATED1 (C22), a COP1-interacting protein (C23), a histone–lysine N-methyltransferase (C24), a paf1 complex subunit (C25), a bromodomain-containing protein (C27), KNOTTED OF ATHALIANA2 (KNAT2) (C28), a A. thaliana pumillio family member (C29), a squamosa promoter binding protein-like 14 (SPL, C31), a type I MADS-domain protein (C30), two AGAMOUS-LIKE (AGL) proteins (C32, C33), ABORTED MICROSPORES (C34), and three SNF2 family proteins (C35, C36, C37).

Phosphoproteins involved in growth and division

There are eight phosphoproteins involved in growth and division. These proteins include a putative condensin complex component SMC3 (C72), a Kelch repeat-containing protein (C72), a putative homologue of POSTMEIOTIC SEGREGATION 1 (C73), POLA3 (C74), a putative homologue of an anther-specific proline-rich protein (C75), a putative homologue of no pollen germination related 2 (C76), a protein related to embryo-abundant proteins (C77), and SMALL AUXIN UPREGULATED68 (C78).

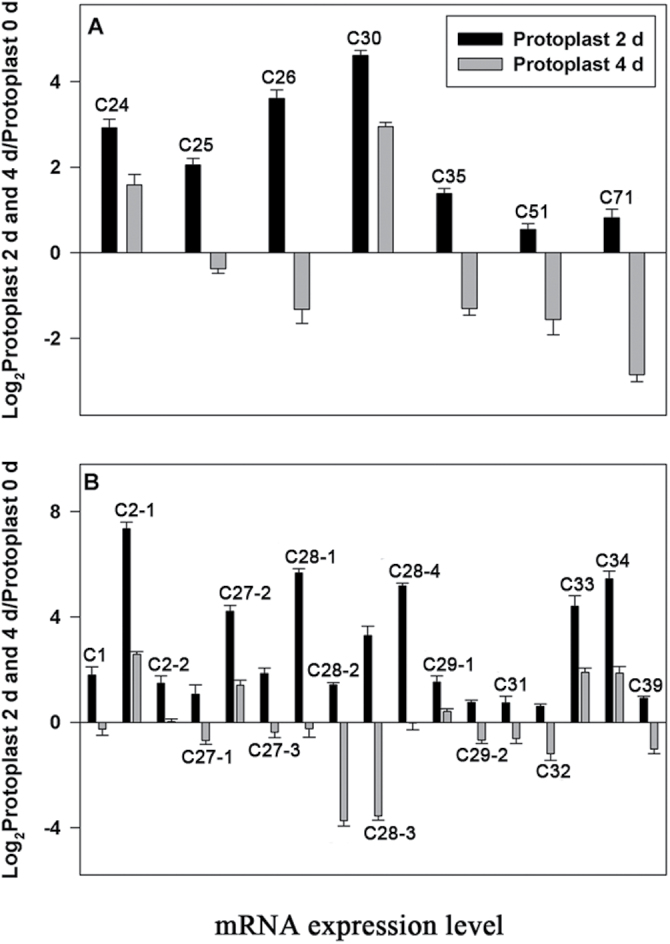

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of phosphoproteins

To correlate protein level with the corresponding mRNA level, this work performed quantitative real-time PCR to analyse the mRNA expression of 24 genes of the 108 proteins specifically phosphorylated on day 4 (Fig. 5). Expression of all of the tested genes was increased at 2 d but fell at 4 d, in many cases falling substantially below the level of the fresh protoplasts. This result indicates that the transcriptional response precedes the protein phosphorylation, a result that is consistent with cellular signal transduction.

Fig. 5.

Real-time quantitative PCR, showing mRNA changed patterns of selected proteins searched for Physcomitrella patens protein database (A) and of the Physcomitrella patens homologous genes of the selected proteins searched in Arabiposis thaliana protein database (B). Message level is expressed as log2 of the ratio of the expression level at day 2 (or day 4) to day 0. All expression levels were measured relative to P. patens actin3 cDNA gene. Values are mean±SD of three replicate experiments.

Discussion

Two major processes that are involved in plant development are morphogenesis and organogenesis. Morphogenesis is the formation of shapes and structures, and this depends on aspects of cell behaviour such as cell-wall synthesis, cell division, and elongation. Organogenesis is the specification of organ identity. Plants are characterized by having continuous postembryonic development, where both meristematic maintenance and growth are coupled with organogenesis and reproduction (Bowman and Eshed, 2000; Gutierrez, 2005). This study shows that the mechanism of protoplast regeneration is similar to that of postembryonic development.

Cell morphogenesis in the process of protoplast regeneration

Protoplast regeneration is accomplished by cell-wall synthesis, cytoskeleton construction, and regulation of the cell cycle. The primary cell wall consists of three coextensive polymer networks: the cellulose–xyloglucan framework, pectin, and structural protein. During protoplast regeneration, xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase (XTH, C1), SKU5 (C2), proline-rich family protein (C83), and glycine-rich protein (C84) are examples of phosphorylated proteins that have plausible roles in primary cell-wall synthesis. In addition, squamosa promoter binding protein-like 14 (C31) is involved in cell-wall regeneration from protoplasts (Yang et al., 2008).

Microtubules and actin filaments are essential components of the machinery required for nuclear division and cytokinesis. Cytokinesis in plant cells is achieved through the construction of a new cell wall between daughter nuclei after mitosis. This process is directed by the phragmoplast, a cytoskeletal structure that is made up in part by parallel microtubules and actin filaments. This work identified several phosphorylated proteins that are implicated in regulating the cytoskeleton, including TAO-1 (C49), a Arf6/ArfB family small GTPase (C50), two kinesins (C79, C86), and a Kelch repeat-containing protein (C72) that has been reported to influence cell shape through the actin cytoskeleton (Adams et al., 2000), and a formin-like protein (C80) and myosin heavy chain (C81) that have been implicated in tip growth in moss (Vidali and Bezanilla, 2012). It indicates that that these cytoskeletal proteins are involved in cell division during protoplast regeneration.

Additionally, this work found several cell-cycle-regulating proteins to be phosphorylated specifically at day 4, including two cyclin-dependent kinase catalytic subunits (CDK, C46, C47), a CDK-activating kinase (C49), and a cyclin (C48). The catalytic subunits do not act alone: their ability to trigger cell-cycle events depends completely on associated cyclin subunits. The timing of activation of the CDK is be controlled by the timing of expression of a particular cyclin subunit, which also contributes to substrate specificity (Harper and Adams, 2001), and by phosphorylation. CDK-activating kinase is such an enzyme that phosphorylates CDKs to activate them (Umeda et al., 2005). These versatile enzymes form the core of the cell-division cycle. Given that more than 90% of the protoplasts divide in the days after protoplast formation, it is not surprising to see evidence of protein phosphorylation among cell-cycle regulators.

Development adjustment in response to protoplast regeneration

In this study, there were several phosphoproteins associated with development and closely related to protoplast regeneration. DET1 (C22) and COP1 control the transcription of multiple genes involved in photomorphogenesis by regulating chromatin conformation (Lau and Deng, 2012). COP1-interacting protein-related (C23) together with COP1 mediates gene expression during photomorphogenesis. Histone–lysine N-methyltransferase (ATX1, C24) is a chromatin modifier that trimethylates lysine 4 of histone H3 of associated nucleosomes. Histone H3 methylation affects DNA methylation and chromatin structure in ways that are consequential for development (Tamaru and Selker, 2001; Jackson et al., 2002). Pumilio (C29) is a founder member of an evolutionarily conserved family of RNA-binding proteins that play an important role in embryo development, differentiation, and asymmetric division (Spassov and Jurecic, 2002).

Surprisingly, this study identified a number of transcription factors that are well known from studies of flowering in seed plants. FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC) is a MADS-box transcriptional regulator controlling flowering time (Michaels and Amasino, 1999). FLC transcription is controlled in part by the PAF1 complex (C25), which mediates histone methylation of FLC chromatin (Yu and Michaels, 2010). AGAMOUS-LIKE (AGL, C32, C33) is also a MADS-box protein required for the normal development of the internal two whorls of the flower (Mizukami et al., 1996). The specific function of these flowering genes in P. patens should be further studied.

Plant organs are formed continuously during development from meristems. ATX1 (C24) is required for the expression of homeotic genes involved in flower organogenesis (Alvarez-Venegas et al., 2003). Within the meristem, the family of KNOX (KNOTTED homeobox) genes plays a crucial role in regulating organogenesis of meristematic cells (Reiser et al., 2000). In A. thaliana, KNAT2 (KNOTTED-like from A. thaliana 2; C28) homeobox gene is expressed in the vegetative apical meristem. It is also active during flower development and plays a role in carpel development (Pautot et al., 2001). In P. patens, KNOX2 acts to prevent the haploid-specific body plan from developing in the diploid plant body (Sakakibara et al., 2013).

Several proteins related to chromosome stability and DNA repair were also identified. The SNF2 family of proteins (C35, C36, C37) plays roles in processes such as transcriptional regulation, maintenance of chromosome stability during mitosis, and various aspects of repairing DNA damage (Eisen et al., 1995). The condensing-complex component SMC3 (C71) is the core component of the tetrameric complex cohesin, which is required for the establishment of sister chromatid cohesion during S phase, maintenance of cohesion, and segregation of chromosomes in mitosis. PMS1 (C73) is a protein involved in the mismatch repair process after DNA replication (Nicolaides et al., 1994). These findings suggest that these proteins play a role in protecting cell stability during protoplast regeneration.

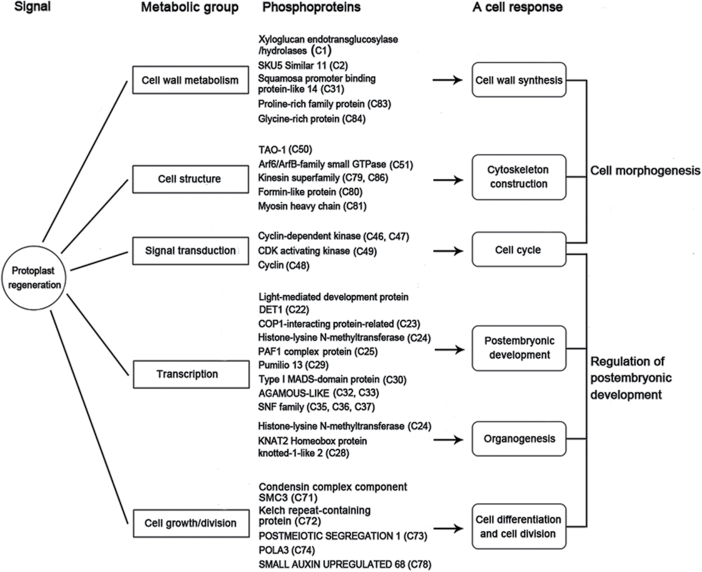

In conclusion, this study is, as far as is known, the first reported assessment of the phosphoproteome during of protoplast regeneration. A comprehensive analysis of the phosphoproteome involved in protoplast regeneration is presented (Fig. 6). This study indicates that there are similar mechanisms for plant protoplast regeneration and postembryonic development. Further studies of how these proteins direct the specific processes will provide deeper insight into plant protoplast regeneration.

Fig. 6.

Cell responses corresponding to phosphoproteins identified during protoplast regeneration in Physcomitrella patens.

Supplementary material

Supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Supplementary Table S1. Quantitative real-time PCR primer pairs for phosphoproteins in the P. patens protein database.

Supplementary Table S2. Quantitative real-time PCR primer pairs for phosphoproteins in the A. thaliana protein database homologous to genes in the P. patens database.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Project of Ministry Science and Technology of China (2013CB967300, 2007CB948201 to Y.H.), by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31371243 to X.W.), and Beijing University of Agriculture Improving Research Quality Foundation (GL2012001 to X.W.). The authors acknowledge editing from Dickinson Meadows.

References

- Adams J, Kelso R, Cooley L. 2000. The kelch repeat superfamily of proteins: propellers of cell function. Trends in Cell Biology 10, 17–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Venegas R, Pien S, Sadder M, Witmer X, Grossniklaus U, Avramova Z. 2003. ATX-1, an Arabidopsis homolog of trithorax, activates flower homeotic genes. Current Biology 13, 627–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avivi Y, Morad V, Ben-Meir H, Zhao J, Kashkush K, Tzfira T, Citovsky V, Grafi G. 2004. Reorganization of specific chromosomal domains and activation of silent genes in plant cells acquiring pluripotentiality. Developmental Dynamics 230, 12–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballif BA, Villen J, Beausoleil SA, Schwartz D, Gygi SP. 2004. Phosphoproteomic analysis of the developing mouse brain. Molecular and Cell Proteomics 3, 1093–1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevan M, Bancroft I, Bent E, et al. 1998. Analysis of 1.9Mb of contiguous sequence from chromosome 4 of Arabidopsis thaliana . Nature 391, 485–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman JL, Eshed Y. 2000. Formation and maintenance of the shoot apical meristem. Trends in Plant Science 5, 110–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell P, Braam J. 1999. Xyloglucan endotransglycosylases: diversity of genes, enzymes and potential wall-modifying functions. Trends in Plant Science 4, 361–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cary AJ, Che P, Howell SH. 2002. Developmental events and shoot apical meristem gene expression patterns during shoot development in Arabidopsis thaliana . The Plant Journal 32, 867–877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cove DJ, Knight CD, Lamparter T. 1997. Mosses as model systems. Trends in Plant Science 2, 99–105 [Google Scholar]

- Criqui MC, Plesse B, Durr A, Marbach J, Parmentier Y, Jamet E, Fleck J. 1992. Characterization of genes expressed in mesophyll protoplasts of Nicotiana sylvestris before the re-initiation of the DNA replicational activity. Mechanisms of Development 38, 121–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai J, Shieh CH, Sheng QH, Zhou H, Zeng R. 2005. Proteomic analysis with integrated multiple dimensional liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry based on elution of ion exchange column using pH steps. Analytical Chemistry 77, 5793–5799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Fuente van Bentem S, Hirt H. 2009. Protein tyrosine phosphorylation in plants: more abundant than expected? Trends in Plant Science 14, 71–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng WJ, Nie S, Dai J, Wu JR, Zeng R. 2010. Proteome phosphoproteome, and hydroxyproteome of liver mitochondria in diabetic rats at early pathogenic stages. Molecular and Cell Proteomics 9, 100–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draviam VM, Stegmeier F, Nalepa G, Sowa ME, Chen J, Liang A, Hannon GJ, Sorger PK, Harper JW, Elledge SJ. 2007. A functional genomic screen identifies a role for TAO1 kinase in spindle-checkpoint signalling. Nature Cell Biology 9, 556–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen JA, Sweder KS, Hanawalt PC. 1995. Evolution of the SNF2 family of proteins: subfamilies with distinct sequences and functions. Nucleic Acids Research 23, 2715–2723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias JE, Gygi SP. 2007. Target-decoy search strategy for increased confidence in large-scale protein identifications by mass spectrometry. Nature Methods 4, 207–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleck J, Durr A, Fritsch C, Lett MC, Hirth L. 1980. Comparison of proteins synthesized in vivo and in vitro by mRNA from isolated protoplasts. Planta 148, 453–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fransz PF, de Jong JH. 2002. Chromatin dynamics in plants. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 5, 560–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friml J, Benkova E, Blilou I, et al. 2002a. AtPIN4 mediates sink-driven auxin gradients and root patterning in Arabidopsis . Cell 108, 661–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friml J, Wisniewska J, Benkova E, Mendgen K, Palme K. 2002b. Lateral relocation of auxin efflux regulator PIN3 mediates tropism in Arabidopsis . Nature 415, 806–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith DW, Harkins KR, Maddox JM, Ayres NM, Sharma DP, Firoozabady E. 1983. Rapid flow cytometric analysis of the cell cycle in intact plant tissues. Science 220, 1049–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith DW, Mauch TJ, Shields BA. 1981. Analysis of the initial stages of plant protoplast development using 33258 Hoechst: reactivation of the cell cycle. Physiologia Plantarum 51, 380–386 [Google Scholar]

- Geldner N, Friml J, Stierhof YD, Jurgens G, Palme K. 2001. Auxin transport inhibitors block PIN1 cycling and vesicle trafficking. Nature 413, 425–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon SP, Heisler MG, Reddy GV, Ohno C, Das P, Meyerowitz EM. 2007. Pattern formation during de novo assembly of the Arabidopsis shoot meristem. Development 134, 3539–3548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez C. 2005. Coupling cell proliferation and development in plants. Nature Cell Biology 7, 535–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper JW, Adams PD. 2001. Cyclin-dependent kinases. Chemical Reviews 101, 2511–2526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heintz D, Erxleben A, High AA, Wurtz V, Reski R, Van Dorsselaer A, Sarnighausen E. 2006. Rapid alteration of the phosphoproteome in the moss Physcomitrella patens after cytokinin treatment. Journal of Proteome Research 5, 2283–2293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter T. 1995. Protein kinases and phosphatases: the yin and yang of protein phosphorylation and signaling. Cell 80, 225–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inze D, De Veylder L. 2006. Cell cycle regulation in plant development. Annual Review of Genetics 40, 77–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JP, Lindroth AM, Cao X, Jacobsen SE. 2002. Control of CpNpG DNA methylation by the KRYPTONITE histone H3 methyltransferase. Nature 416, 556–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joubes J, Chevalier C, Dudits D, Heberle-Bors E, Inze D, Umeda M, Renaudin JP. 2000. CDK-related protein kinases in plants. Plant Molecular Biology 43, 607–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khandelwal A, Cho SH, Marella H, Sakata Y, Perroud PF, Pan A, Quatrano RS. 2010. Role of ABA and ABI3 in desiccation tolerance. Science 327, 546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau OS, Deng XW. 2012. The photomorphogenic repressors COP1 and DET1: 20 years later. Trends in Plant Science 17, 584–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long JA, Moan EI, Medford JI, Barton MK. 1996. A member of the KNOTTED class of homeodomain proteins encoded by the STM gene of Arabidopsis . Nature 379, 66–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer Y, Abel WO. 1975. Importance of the wall for cell division and in the activity of the cytoplasm in cultured tobacco protoplasts Planta 123, 33–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaels SD, Amasino RM. 1999. FLOWERING LOCUS C encodes a novel MADS domain protein that acts as a repressor of flowering. The Plant Cell 11, 949–956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizukami Y, Huang H, Tudor M, Hu Y, Ma H. 1996. Functional domains of the floral regulator AGAMOUS: characterization of the DNA binding domain and analysis of dominant negative mutations. The Plant Cell 8, 831–845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers KR, Casanova JE. 2008. Regulation of actin cytoskeleton dynamics by Arf-family GTPases. Trends in Cell Biology 18, 184–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata T, Ishida S, Hasezawa S, Takahashi Y. 1994. Genes involved in the dedifferentiation of plant cells. International Journal of Developmental Biology 38, 321–327 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaides NC, Papadopoulos N, Liu B, et al. 1994. Mutations of two PMS homologues in hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer. Nature 371, 75–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pautot V, Dockx J, Hamant O, Kronenberger J, Grandjean O, Jublot D, Traas J. 2001. KNAT2: evidence for a link between knotted-like genes and carpel development. The Plant Cell 13, 1719–1734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson GL. 1977. A simplification of the protein assay method of Lowry et al. which is more generally applicable. Analytical Biochemistry 83, 346–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiser L, Sanchez-Baracaldo P, Hake S. 2000. Knots in the family tree: evolutionary relationships and functions of knox homeobox genes. Plant Molecular Biology 42, 151–166 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogg LE, Lasswell J, Bartel B. 2001. A gain-of-function mutation in IAA28 suppresses lateral root development. The Plant Cell 13, 465–480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakakibara K, Ando S, Yip HK, Tamada Y, Hiwatashi Y, Murata T, Deguchi H, Hasebe M, Bowman JL. 2013. KNOX2 genes regulate the haploid-to-diploid morphological transition in land plants. Science 339, 1067–1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakakibara K, Nishiyama T, Sumikawa N, Kofuji R, Murata T, Hasebe M. 2003. Involvement of auxin and a homeodomain-leucine zipper I gene in rhizoid development of the moss Physcomitrella patens . Development 130, 4835–48346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlessinger J. 2000. Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell 103, 211–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedbrook JC, Carroll KL, Hung KF, Masson PH, Somerville CR. 2002. The Arabidopsis SKU5 gene encodes an extracellular glycosyl phosphatidylinositol-anchored glycoprotein involved in directional root growth. The Plant Cell 14, 1635–1648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheen J. 2001. Signal transduction in maize and Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts. Plant Physiology 127, 1466–1475 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spassov DS, Jurecic R. 2002. Cloning and comparative sequence analysis of PUM1 and PUM2 genes, human members of the Pumilio family of RNA-binding proteins. Gene 299, 195–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama N, Nakagami H, Mochida K, Daudi A, Tomita M, Shirasu K, Ishihama Y. 2008. Large-scale phosphorylation mapping reveals the extent of tyrosine phosphorylation in Arabidopsis . Molecular Systems Biology 4, 193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabb DL, McDonald WH, Yates JR., 3rd 2002. DTASelect and Contrast: tools for assembling and comparing protein identifications from shotgun proteomics. Journal of Proteome Research 1, 21–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaru H, Selker EU. 2001. A histone H3 methyltransferase controls DNA methylation in Neurospora crassa . Nature 414, 277–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thingholm TE, Larsen MR. 2009. The use of titanium dioxide micro-columns to selectively isolate phosphopeptides from proteolytic digests. Methods in Molecular Biology 527, 57–66, xi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umeda M, Shimotohno A, Yamaguchi M. 2005. Control of cell division and transcription by cyclin-dependent kinase-activating kinases in plants. Plant Cell Physiology 46, 1437–1442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernet T, Fleck J, Durr A, Fritsch C, Pinck M, Hirth L. 1982. Expression of the gene coding for the small subunit of ribulosebisphosphate carboxylase during differentiation of tobacco plant protoplasts. European Journal of Biochemistry 126, 489–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidali L, Bezanilla M. 2012. Physcomitrella patens: a model for tip cell growth and differentiation. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 15, 625–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollbrecht E, Veit B, Sinha N, Hake S. 1991. The developmental gene Knotted-1 is a member of a maize homeobox gene family. Nature 350, 241–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XQ, Yang PF, Liu Z, Liu WZ, Hu Y, Chen H, Kuang TY, Pei ZM, Shen SH, He YK. 2009. Exploring the mechanism of Physcomitrella patens desiccation tolerance through a proteomic strategy. Plant Physiology 149, 1739–1750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Tu L, Zhu L, Fu L, Min L, Zhang X. 2008. Expression profile analysis of genes involved in cell wall regeneration during protoplast culture in cotton by suppression subtractive hybridization and macroarray. Journal of Experimental Botany 59, 3661–3674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Michaels SD. 2010. The Arabidopsis Paf1c complex component CDC73 participates in the modification of FLOWERING LOCUS C chromatin. Plant Physiology 153, 1074–1084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Morozova N, Williams L, Libs L, Avivi Y, Grafi G. 2001. Two phases of chromatin decondensation during dedifferentiation of plant cells: distinction between competence for cell fate switch and a commitment for S phase. Journal of Biological Chemistry 276, 22772–22778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.