Abstract

The association between relational aggression and popularity during early adolescence is well established. Yet, little is known about why, exactly, relationally aggressive young adolescents are able to achieve and maintain high popular status among peers. The present study investigated the mediating role of humor in the association between relational aggression and popularity during early adolescence. Also considered was whether the association between relational aggression and humor varies according to adolescents’ gender and their friends’ levels of relational aggression. Participants were 265 sixth-grade students (48% female; 41% racial/ethnic minority; Mage = 12.04 years) who completed peer nomination and friendship measures in their classrooms at two time points (Wave 1: February; Wave 2: May). The results indicated that Wave 1 relational aggression was related to Wave 1 and 2 popularity indirectly through Wave 1 humor, after accounting for the effects of Wave 1 physical aggression, ethnicity, and gender. Additional analyses showed that relational aggression and humor were related significantly only for boys and for young adolescents with highly relationally aggressive friends. The results support the need for further research on humor and aggression during early adolescence and other mechanisms by which relationally aggressive youth achieve high popular status.

Keywords: Relational Aggression, Physical Aggression, Popularity, Humor

Introduction

The extant literature clearly indicates that relational aggression (e.g., spreading malicious rumors; behaviors that use relationships to harm others) and physical aggression (e.g., hitting others) are distinct forms of aggressive behavior during early adolescence (10–14 years), with unique peer and adjustment concomitants (e.g., Cillessen & Mayeux, 2004; Coie, Dodge, & Coppotelli, 1982; Lansford et al., 2012; Mayeux & Cillessen, 2008; Vaillancourt & Hymel, 2006). For example, unique associations between relational and physical aggression and later internalizing problems have been revealed (e.g., Crick, Ostrov, & Werner, 2006). Both forms of aggression are also related positively to popularity in concurrent and longitudinal studies, although recent research indicates that the association between physical aggression and popularity is rendered non-significant when relational aggression is controlled (Rose, Swenson, & Waller, 2004; Smith, Rose, & Schwartz-Mette, 2010).

The strong linkage between relational aggression and popularity is worrisome because popular young adolescents have considerable influence over their grademates. Indeed, there is growing evidence that popular young adolescents have the “power” to influence their peers’ norms and cognitions related to drug and alcohol use and deviancy, as well as their actual behaviors (Prinstein, Brechwald, & Cohen, 2011; Teunissen et al., 2012). Such delinquent and antisocial behaviors during adolescence predict similar negative adjustment outcomes during young adulthood (e.g., Pape & Hammer, 1996). However, few empirical studies have investigated why, exactly, relationally aggressive young adolescents are able to achieve and maintain high popular status among peers. We posit herein that humor is one mechanism by which relationally aggressive young adolescents become popular with peers. We test this hypothesized mediating association for the first time, to our knowledge, in this study. Two moderators (adolescents’ gender, friends’ relational aggression) of the association between relational aggression and humor are also evaluated. A greater understanding of factors that account for the strong association between relational aggression and popularity may be critical to better target interventions aimed at reducing relationally aggressive behavior (Leff & Crick, 2010; Leff et al., 2010), which has been shown to be psychologically damaging for its victims (Desjardins & Leadbeater, 2011; Nixon, Linkie, Coleman, & Fitch, 2011; You & Bellmore, 2012).

Relational Aggression, Humor, and Popularity

The expectation that humor will mediate the relation between relational aggression and popularity arises from several theories and lines of research. To begin, peer relations theory and research suggest that humor is an important feature of social interactions and relationships during childhood and adolescence (e.g., Asher, Parker, & Walker, 1996; Masten, 1986; Sanford & Eder, 1984). Being funny vis-à-vis jokes, funny story-telling and humorous behavior is not only common, but serves several important social functions (Masten, 1986; Ransohoff, 1975; Sanford & Eder, 1984). In one of the few observational studies of humor during adolescence, Sanford and Eder (1984) observed humor to help facilitate interaction with new friends, communicate information (about sexuality, adult and peer norms), to reinforce friendship bonds, and to show dislike for certain peers. Humor is also an oft-utilized coping strategy for adolescents (e.g., Erickson & Feldstein, 2007). Adults admire humorous individuals (e.g., Bressler & Balshine, 2006), and the same appears to be true of adolescents. Several cross-sectional studies also reveal significant linkages between peer-perceptions of humor and peer nominations of popularity, peer acceptance and social preference (Closson, 2009; Masten, 1986; Vaillancourt & Hymel, 2006).

There is some evidence that physically aggressive and delinquent adolescents are viewed by peers as having a good sense of humor (Dodge & Coie, 1987), and that their friends find their behavior to be humorous (as seen in the studies of delinquency training when adolescents respond to deviant talk with laughter as well as positive attention; Dishion, Spracklen, Andrews, & Patterson, 1996; Patterson, Dishion, & Yoerger, 2000; Snyder, Prichard, Schrepferman, Patrick, & Stoolmiller, 2004). One recent study found that adolescents reported that they bullied others online (which may involve relationally aggressive behavior) because it made them feel funny, popular, and powerful (Mishna, Cook, Gadalla, Daciuk, & Solomon, 2010). We could not locate a single study in which relationally aggressive behavior per se was examined in relation to peer-perceptions of humor, but linkages have been theorized (Klein & Kuiper, 2006) and some of the jokes observed by Sanford and Eder (1984) involved negative gossip, such as the telling of a story about the eating behavior of a classmate, which the girls found to be humorous. In addition, Sanford and Eder (1984) observed that practical jokes, which were often directed towards less desirable members of the peer group, were typically embarrassing or humiliating for the intended target, but brought about smiles and laughter from other members of the peer group.

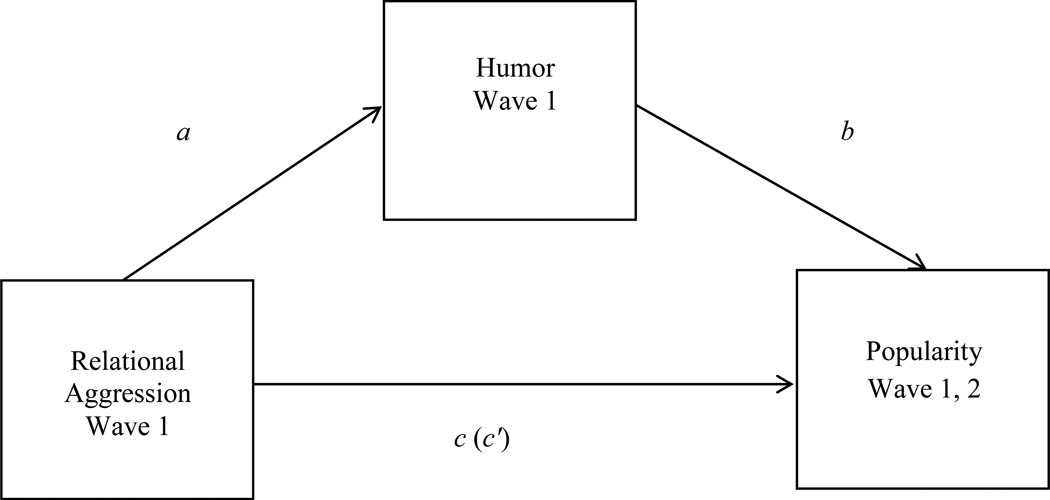

But why might relational aggression be viewed as funny? Psychological and social-cognitive theories of humor suggests that individuals of all ages come to enjoy and find things, people, and events funny when they are perceived to be violations of what is normal and typical (e.g., Geisler & Weber, 2010; Veatch, 1998). Thus, when a behavior/event is perceived to violate norms, perceptions of humor are thought to follow along with positive emotions and positive social regard (Geisler & Weber, 2010; Veatch, 1998). No studies have tested this conceptual model as it applies to relational aggression (relational aggression → humor → popularity; see Figure 1), but the model dovetails well with the “maturity gap” hypothesis (e.g., adolescents admire aggressive and assertive behavior because it is considered authority- and adult-defying; Moffitt, 1993) and literature demonstrating that relational aggression is a relatively uncommon behavior that is also valued and admired, at least during early adolescence (e.g., Bukowski, Sippola, & Newcomb, 2000; Werner & Hill, 2010). Klein and Kuiper (2006) suggest that relationally aggressive youth may diminish and degrade their victims, but that these youth use humor in a socially skilled way that allows them to maintain their positions and respect within their peer groups. It is also the case that, in Western societies, adolescents may become socialized to find aggressive youth or aggressive behavior funny by the media, internet messages and websites, and books and movies targeting children and adolescents, which often pair humor and physical and relational aggression (e.g., Bjorkqvist & Lagerspetz, 1985; Coyne, Ridge, Stevens, Callister, & Stockdale, 2012). Finally, many adults seem to enjoy hostile and aggressive humor, suggesting that it is also plausible that adolescents learn from their parents vis-à-vis social learning processes (such as observing their parents laugh at relationally aggressive behavior and later imitating such reactions to relational aggression; Bandura & Walters, 1963) that relationally aggressive youth are humorous, which, in turn, explains why this behavior affords them with high popular status.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model in which peer-perceptions of humor explain the concurrent and longitudinal asociations between relational aggression and popularity and preference.

Adolescents’ Gender and Friends’ Aggression as Moderators

The research on the significance of humor in the lives of young adolescents has been limited, with past studies focusing primarily on main effects. However, two moderators may operate on the first process in the mediation model by impacting the linkage between relational aggression and peers’ perceptions of humor. First, the gender-linked hypothesis of aggression (for review see Ostrov & Godleski, 2010) implicates gender as a potential moderator. It is well known that youth often associate female gender identity with relational aggression and male identity with physical aggression (e.g., French, Jansen, & Pidada, 2002); thus, boys engaging in relational aggression may be considered as engaging in gender nonnormative behavior. If individuals perceive things to be humorous when they violate norms and expectations (Veatch, 1998), it seems likely that the associations between relational aggression and humor might be stronger for boys than girls.

It is also plausible that the degree to which adolescents’ friends are relationally aggressive moderates the association between relational aggression and humor such that the association is the strongest for adolescents with highly relationally aggressive friends. This hypothesis is based on recent evidence that friends’ aggressiveness plays a critical role in adolescent adjustment (e.g., Bowker, Ostrov, & Raja, 2012; Werner & Crick, 2004). For instance, one study found that friends’ relational aggression scores predict later relational aggression (Werner & Crick, 2004). In addition, we reasoned that relationally aggressive behavior may be viewed as more socially acceptable and less harmful when the behavior is enacted by two friends who may be engaging in greater relational aggression together (than if they were alone) and directing some of the behavior toward each other (Crick & Nelson, 2002), similar to how the frequency of behavior impacts positively the degree to which aggressive youth are accepted by peers (e.g., Boivin, Dodge, & Coie, 1995; Chang, 2004). Indeed, Veatch (1998) argues that behaviors are judged to be humorous when the behavior violates a norm but in a relatively socially acceptable way that is not personally threatening. Thus, although tentative, our hypothesis is that two relationally aggressive friends might be perceived as funnier because together they violate social norms and expectations in a way that is perceived as more socially acceptable and as less threatening than one relationally aggressive adolescent alone.

Hypotheses

In the current study, we test whether peer-perceptions of humor mediate the association between relational aggression and popularity in a sample of sixth-grade students. Adolescents’ gender and friends’ relational aggression are evaluated as moderators of the expected linkage between relational aggression and humor. Data were collected twice in a three month period, and thus this short-term longitudinal study allowed us to test the models concurrently and prospectively. Consistent with recommendations (e.g., Bowker et al., 2012), physical aggression was controlled in analyses. Drawing from past theory and research on humor, peer relationships, and relational aggression (Bukowski et al., 2000; Geisler & Weber, 2010; Moffitt, 1993; Veatch, 1998), humor is expected to emerge as a significant mediator in both the concurrent and longitudinal analyses. In addition, particularly strong associations between relational aggression and humor are expected for boys and for young adolescents with highly relationally aggressive friends. The conceptual model for the present study was developed from theory and research on humor and peer relationships in which certain behaviors/events are posited to lead to laughter and perceptions of humor and later social consequences (e.g., Veatch, 1998). However, popularity has been shown to predict relational aggression during early adolescence (e.g., Rose, et al., 2004). Thus, we tested alternative causal models in which humor and relational aggression are related vis-à-vis popularity.

Method

Participants

Participants were 265 (126 girls) sixth-grade students (M age at start of study = 12.04 years) from two public middle schools who were participating in a longitudinal study on peer relationships. All sixth-grade students from both schools were invited to participate in the study. To encourage the return of permission forms, all students who returned their forms, regardless of their decision to participate, received a University at Buffalo t-shirt and were eligible to win a gift certificate to a local retail store. Approximately 59% of participants indicated that they were Caucasian, 21% were African-American, and the 20% remaining self-identified as belonging to a different minority group or as being biracial. Six participants dropped out the study due to moving away from their schools and were therefore not included in analyses (overall consent rate = 70%).

Procedure

This study was part of a larger study on changes in friendship involvement. Participants for this study completed measures in their schools at two time points in their individual classrooms or large school rooms, such as a cafeteria (Wave 1: February; Wave 2: May). Waves were spaced three months apart to study short-term changes in friendship involvement, which were not of interest in the present study. At each wave, trained research assistants administered the measures; teachers and school staff were not involved in the data collections. No instructions or items were read aloud but research assistants closely monitored the completion of the measures and participants were instructed to raise their hands if they had any questions or difficulty. Students took approximately 30–45 minutes to complete the paper-and-pencil measures. Participants were told that their answers were confidential and that they could skip any item and choose to stop completing the measures at any time.

Measures

Friendship (Wave 1)

Participants wrote the names of their same-gender “very best friend” and “second best friend,” and three same- or other-gender “good” or “close” friends from their grade and school (Bukowski, Hoza, & Boivin, 1994). Friendships were considered mutual if the nominations were reciprocated (either as a “best” or “good” friend). Consistent with past studies on friendship during early adolescence (e.g., Parker & Asher, 1993), 70% of participants (143/205) in the present study had at least one mutual friend, with girls being significantly more likely to have a mutual friendship than boys, χ2 (1) = 11.70, p = .001, η2 = 0.24. Mutual friendship could not be determined for 20 adolescents (13 boys) either because all of their friendship nominations were for non-participating students or for participating students who did not complete the friendship nomination measure at Wave 1. Forty additional participants did not complete friendship nominations at Wave 1 due to absenteeism and/or failure to complete all of the questionnaires. The relational aggression scores of participants’ first mutual friend (e.g., if a participant’s first/”best” friendship nomination was not reciprocated, the mutuality of the next nomination was examined until a mutual friendship was identified) were utilized in analyses. It is important note that there were no significant differences in the study variables between adolescents who had friendship data and those who did not; the missing friend data decreased only the sample size for the moderated mediation analyses testing friends’ relational aggression as a moderator (N = 143).

Peer Nominations (Waves 1 and 2)

Peer nomination items were used to assess relational and physical aggression, humor, and popularity and social preference. For all peer nomination items, participants were allowed to make unlimited nominations of same-gender and other-gender peers from their grade and school. Self-nominations were permitted but excluded from analyses. Nominations received by each participant were first summed, proportionalized, and then standardized within grade and school (Cillessen, 2009).

Relational aggression

Two peer nomination items assessed relational aggression: “Someone who spreads rumors so that other people won’t like them “; and “Someone who keeps certain kids from being in their group when it is time to play or do an activity” (Rose et al., 2004; Smith, Rose, & Schwartz-Mette, 2010). The internal consistency of the averaged relational aggression scale approached acceptable levels at Wave 1 (α = .64) and was adequate at Wave 2 (α = .73).

Physical aggression

Two peer nomination items assessed physical aggression: “Someone who hits, kicks or punches others”; “Someone who pushes or shoves others” (Crick, Casas, & Mosher, 1997; Rose et al., 2004). Mean scores were calculated; the internal consistency for the averaged scale was excellent (Wave 1: α = .94; Wave 2: α = .94).

Humor

A single-item peer nomination was used to evaluate humor, “A person with a good sense of humor” (Gest, Graham-Bermann, & Hartup, 2001). Due to the multiple-informant nature of peer nominations, single-item peer nomination assessments are considered reliable (Coie, Dodge, & Kupersmidt, 1990).

Popularity

Students were asked to make unlimited nominations for classmates who were popular and not popular (Cillessen & Mayeux, 2004; Lease, Musgrove, & Axelrod, 2002). “Not popular” nominations were subtracted from “popular” nominations, and restandardized to yield popularity scores for each participant (Cillessen & Mayeux, 2004).

Results

Zero-order Correlations

The zero-order correlations among the study variables are presented in Table 1. As expected, the relational aggression, physical aggression, humor, and popularity variables demonstrated moderate temporal stability across the two assessments. At each wave, relational aggression was associated positively with popularity. At Wave 1, relational aggression was associated significantly with physical aggression as well as peer-perceptions of humor. At Waves 1 and 2, the humor variables were associated significantly with popularity. Also of note, ethnicity was related significantly with relational and physical aggression, friends’ relational aggression at Wave 1, and humor at Wave 2, and adolescents’ gender was related to humor and physical aggression at Wave 1. Friends’ relational aggression was related significantly with all variables, with the exception of popularity at Wave 1 and gender. Finally, it should be noted that the aggression and humor variables were skewed significantly. Inverse transformations were applied, and analyses were then performed with untransformed and transformed data; however, due to the similarity of the results, the results using untransformed data are presented.

Table 1.

Zero-order Correlations Among Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. RelAggW1 | .45** | .66** | .58** | .20** | .05 | .35** | .31** | .19* | .02 | .31** | |

| 2. RelAggW2 | .34** | .38** | .15* | .06 | .33* | .31** | −.01 | .02 | .27** | ||

| 3. PhyAggW1 | .85** | .12 | −.02 | .22** | .13* | .17* | −.14* | .29** | |||

| 4. PhyAggW2 | .15* | .05 | .18* | .12 | .16* | −.15* | .33** | ||||

| 5. HumorW1 | .56** | .20** | .33** | −.08 | −.14* | .32** | |||||

| 6. HumorW2 | .07 | .19** | −.15* | .01 | .25** | ||||||

| 7. PopW1 | .59** | −.12 | .11 | .16 | |||||||

| 8. PopW2 | −.01 | .04 | .29 | ||||||||

| 9. Ethnicity | .03 | .19* | |||||||||

| 10. Gender | .05 | ||||||||||

| 11. FrRelAggW1 |

Note. RelAgg and PhyAgg refer to relational and physical aggression, respectively; Pop refers to popularity; FrRelAgg refers to the mutual friends’ relationally aggressive scores at Wave 1; W1 and W2 refer to Waves 1 and 2; Gender is coded as 0 = boys and 1 = girls

p < .05

p < .001

Meditated and Moderated Mediation Models

Mediation analyses tested whether peer-perceptions of humor mediated the association between relational aggression and popularity (see Figure 1). Two concurrent models (at Wave 1 and Wave 2) and two longitudinal models (one controlling for Wave 1 popularity) were tested. These analyses utilized the procedures outlined by Preacher and Hayes (2008; Hayes, 2013) and their available SPSS macro to perform bootstrapping, with 5,000 resamples, which produces 95% confidence intervals to evaluate the significance of the indirect effects of relational aggression on popularity. Significant indirect effects are present when confidence intervals do not include zero. The macro also tested the significance of the direct effects of relational aggression on humor (a in Figure 1) and humor on the dependent variables (b in Figure 1) as well as the total (c in Figure 1) and direct effects (c' in Figure 1, which accounts for the presence of the mediator, humor) of relational aggression on the dependent variables. The moderated mediation models also utilized the available SPSS macro and bootstrapping procedures (with 5,000 resamples) to determine whether adolescents’ gender and friends’ relational aggression moderated the association between relational aggression and humor when popularity served as the dependent variable. Consistent with recommendations (Preacher, Rucker, & Hayes, 2007), significant moderated mediation effects involving friends’ relational aggression were probed at high (1 SD above the mean), medium (at the mean), and low (1 SD below the mean). In all analyses, ethnicity and physical aggression were controlled. In addition, in one of the longitudinal models in which Wave 2 (W2) popularity was the dependent variable, W1 popularity was controlled. Adolescents’ gender was included as a covariate in the mediation models and the moderated mediation models in which friends’ relational aggression was tested as the moderator variable.

Mediation Models

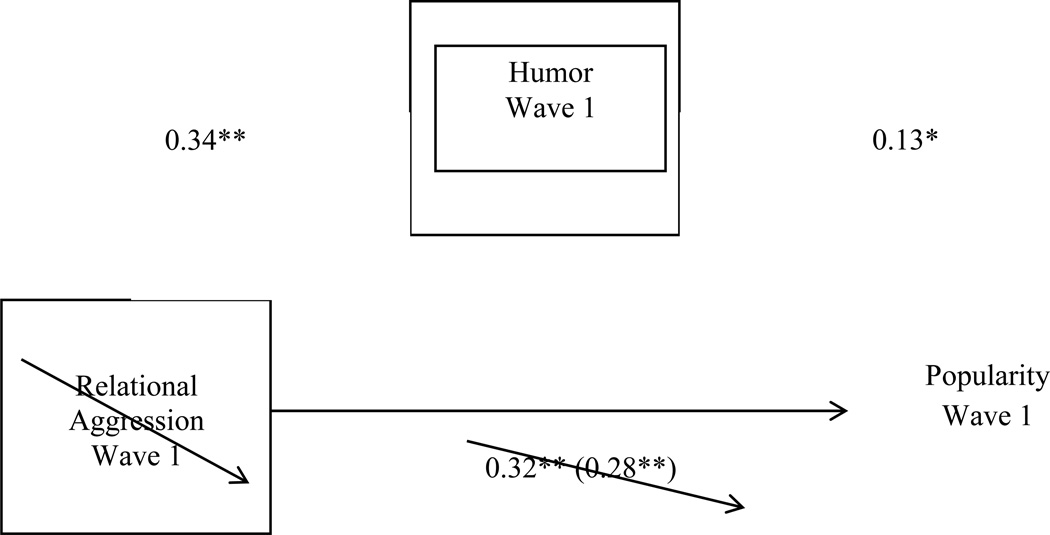

Wave 1

When W1 popularity served as the dependent variable, the direct effects of W1 relational aggression on W1 humor and W1 humor on popularity were significant (see Figure 2). The total effect of W1 relational aggression on W1 popularity was reduced when W1 humor was entered into the model; the 95% confidence interval for the indirect effect was between [0.01–0.12], indicating that W1 humor is a significant mediator of the association between W1 relational aggression and W1 popularity (B = 0.04), after controlling for the effects of W1 physical aggression, gender, and ethnicity.

Figure 2.

Wave 1 humor as a mediator of the association between Wave 1 relational aggression and Wave 1 popularity.

*p < .05, ** p < .001

Wave 2

When W2 popularity was the dependent variable and W2 physical aggression, gender, and ethnicity were controlled, the direct effects of W2 relational aggression on W2 humor was not significant (unstandardized coefficient B = 0.10, p = .30) but the direct effect of W2 humor on W2 popularity was significant (B = 0.18, p = .004). The total effect of W2 relational aggression on W2 popularity (B = 0.18, p = .04) was reduced to non-significant when W2 humor was entered into the model (B = 0.16, p = .06); however, the 95% confidence interval for the indirect effect was between [-0.02–0.13].

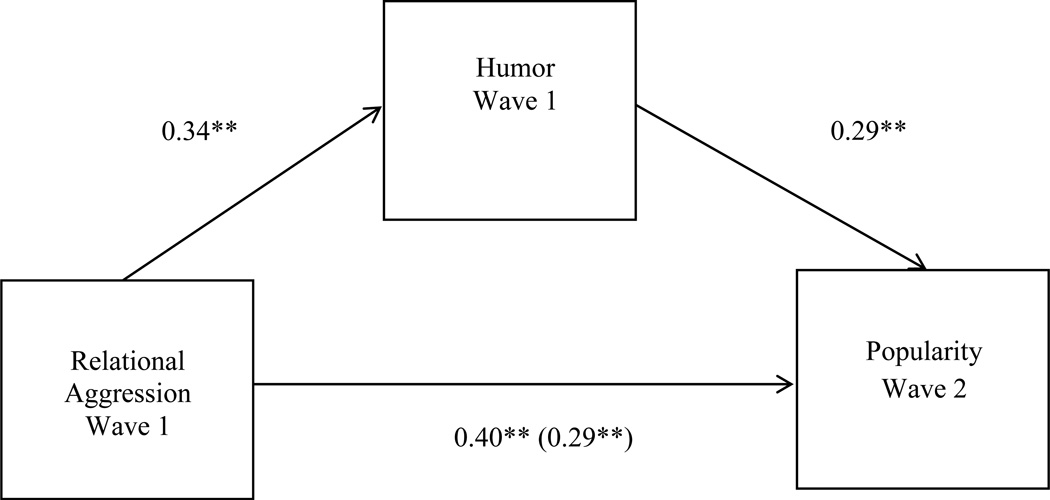

Wave 1 to Wave 2

The first longitudinal model evaluated W2 popularity as the dependent variable, W1 relational aggression as the independent variable, and W1 humor as the mediator variable. In this model, W1 physical aggression, gender, and ethnicity were controlled, and the direct effects of W1 relational aggression on W1 humor and W1 humor on W2 popularity were significant (see Figure 3). The total effect of W1 relational aggression on W2 popularity was reduced when W1 humor was entered into the model. The 95% confidence interval for the indirect effect was between [0.02–0.25], suggesting that W1 humor is a significant mediator of the association between W1 relational aggression and W2 popularity (B = 0.10), after controlling for the effects of W1 physical aggression, gender, and ethnicity.

Figure 3.

Wave 1 humor as a mediator of the association between Wave 1 relational aggression and Wave 2 popularity.

*p < .05, ** p < .001

One additional mediation model was tested in which W2 popularity served as the dependent variable, and the corresponding W1 popularity variable, W1 physical aggression, gender, and ethnicity were controlled. This model tested whether humor can explain why some relationally aggressive young adolescents become increasingly popular over time. In this model, the direct effects of W1 relational aggression on W1 humor (B = 0.24, p = .01), and W1 humor on W2 popularity were significant (B = 0.23, p = .001). The total effect of relational aggression on W2 popularity (B = 0.21, p = .02) was reduced to non-significant after W1 humor was entered into the model (B = 0.15, p = .08). However, the indirect effect was not significant (B = 0.06; 95% CI [-0.01–0.21]). Of note, the direct effects of W1 and W2 physical aggression on humor were not significant in any of the mediation models (ps > .24) and the results did not differ in terms of significance when physical aggression was not controlled in the models.

Moderated Mediation Models

In the concurrent (focusing on W1 data: B = 0.21, 95% CI [0.07–0.34]) and longitudinal models (e.g., controlling for W1 popularity: B = 0.24, 95% CI [0.10–0.37]) with popularity as the outcome, W1 friends’ relational aggression emerged as a significant moderator of the association between W1 relational aggression and W1 humor. Adolescents’ gender (coded as 0 = boys, 1 = girls) also emerged as a significant moderator in the concurrent (focusing on W1 data: B = −0.71, 95% CI [-1.09-(-0.32)]) and longitudinal models (e.g., controlling for W1 popularity: B = −0.68, 95% CI [-1.06-(-0.30)] in which popularity served as the dependent variables. Because the three-way interactions between relational aggression, friends’ relational aggression, and adolescents’ gender were not significant, the moderators were tested in separate models which allowed gender to be tested as a moderator for all study participants and not only those with mutual friends (which allowed the entire sample to be evaluated). Inspection of the bootstrapping estimates and slope coefficients for the conditional indirect effects revealed that relational aggression at W1 was associated significantly with peer-perceptions of humor at W1 for boys (B = 0.09,95% CI [0.02–0.25]) but not for girls (B = 0.01, 95% CI [-0.01–0.06]). Also, W1 relational aggression was found to be associated significantly with W1 humor for young adolescents with highly relationally aggressive friends at Wave 1 (B = 0.05, 95% CI [0.004–0.31]) but not for those adolescents whose friends are average (B = 0.03, 95% CI [-0.001–0.17) and low in their relational aggression levels (B = 0.01, 95% [-0.02–0.17]).

Alternative Models

Because it is also possible that relationally aggressive adolescents come to be perceived as funny because they are popular and their behaviors are visible, two additional alternative models were tested in which W1 relational aggression served as the predictor variable, W1 popularity was the mediator, and W1 and W2 humor were the dependent variables. However, none of the indirect effects in these models were statistically significant. The indirect effects were also not significant when W1 humor was tested as the independent variable, W1 popularity served as the mediator variable, and W1 and W2 relational aggression were the dependent variables (output available from the first-author by request).

Discussion

Researchers for some time have been interested in the linkages between relational aggression and popularity (for recent review, see Crick, Murray-Close, Marks, & Mohajeri-Nelson, 2009). The present study represents a novel addition to the extant literature on relational aggression and popularity by testing the hypothesis that humor might explain why many relationally aggressive young adolescents are able to attain and maintain popular status among peers. The theoretical and causal framework for this investigation was formulated by integrating past theory and research on humor (Geisler & Weber, 2010; Sanford & Eder, 1984; Veatch, 1998), which suggests that individuals find things/events/people to be funny when they perceive them to violate social norms and expectations, with the literature on peer relationships and aggression (e.g., Bukowski et al., 2000; Moffitt, 1993). While most prior research on humor has focused on main effects, we also considered adolescents’ gender and friends’ relational aggression as moderators of the association between relational aggression and peer-perceptions of humor.

The results generally supported our initial hypotheses in that direct effects were found between relational aggression and humor in both the Wave 1 concurrent and longitudinal models. These findings are consistent with the results from past studies demonstrating that humor during adolescence often involves negative gossip and embarrassing practical jokes (Sanford & Eder, 1984) as well as sarcasm and mocking (Cameron, Fox, Anderson, & Cameron, 2010). Of note, physical aggression was not related significantly to humor in the correlational analyses or the mediation models, suggesting that there may be something uniquely funny about relationally aggressive behavior during the early adolescent developmental period. Both forms of aggression are thought to be relatively infrequent during childhood and adolescence (Crick et al., 2009). However, there is some indication that physical aggression becomes even less common and viewed as more unacceptable relative to relational aggression beginning in middle childhood (Murray-Close & Ostrov, 2004). In addition, physical aggression is more overt and noticeable than relational aggression, and there is some evidence suggesting that the physical aggression is perceived as more harmful than certain forms of indirect aggression (Coyne, Archer, & Eslea, 2006). Thus, it may be that the social unacceptability and perceived harm tempers the degree to which physical aggression is perceived as humorous, especially during early adolescence when the harmful behaviors are directed at peers and friends. Of course, it is also possible that it is not relationally aggressive behavior per se that is perceived as funny but that relationally aggressive young adolescents engage in other types of humor that are not relationally aggressive in nature (e.g., memorized jokes; Sanford & Eder, 1984). Our study was limited by its lack of specific questions about what adolescents find funny and why, and addressing this significant study limitation should be the goal of future research.

The findings from this investigation also suggest that researchers should further consider individual and relationship factors that might impact the association between relational aggression and humor in future studies. In the current investigation, we found that adolescents’ gender and friends’ relational aggression were significant moderators of the link between relational aggression and humor such that relational aggression was associated significantly with humor only for boys and those young adolescents with highly relationally aggressive friends.

Because relational aggression is typically considered more nonnormative for boys than girls and norm-violating behavior is often considered funny (Crick, Bigbee, & Howes, 1996; Ostrov & Godleski, 2010; Sanford & Eder, 1984), boys who are relationally aggressive may be perceived as funnier than similarly aggressive girls, for whom relationally aggressive behavior is more typical or expected. The gender nonnormativeness of the behavior for boys may also cause young adolescents to focus less on the harmful aspects of relationally aggressive boys' behavior and more on the surprising and humorous aspects of it. Furthermore, it should be acknowledged that gender differences have been identified in regards to adolescent humor. Generally, humorous behavior may be expected from boys more than girls (Ziv, 1981), and it is more common for boys to use humor more aggressively (whereas girls may use humor more to feel better; Führ, 2002), with evidence that even proactively aggressive boys are viewed as humorous by their peers (Dodge & Coie, 1987). The studies of adults have also shown that men have a greater appreciation for hostile humor than do females (e.g., Mundorf, Bhatia, Zillmann, Lester, & Robinson, 1988). Because of the differences in expectations for boys and girls in levels of relational aggression and use of humor, relationally aggressive behavior may be more likely to be interpreted as humor when emanating from boys.

With regard to friends’ relational aggression, two relationally aggressive friends might be more noticeable in their norm-violating behavior, and thus more readily perceived as funnier. It is also plausible that their behavior is viewed as less personally threatening (a requirement for humor; Veatch, 1998) because some of their relationally aggressive behaviors are directed at each other. Consistent with this notion, Tragesser and Lippmann (2005) found that teasing between friends is often times interpreted as a sign of closeness, rather than a sign of hostility or danger. Finally, it may be that two relationally aggressive friends engage in aggressive banter, joke-telling and teasing together, which, in turn, makes the behaviors appear to be more socially acceptable, and therefore funnier. Past research on aggressive humor in adults has implicated other individual and relationship characteristics (e.g., ethnicity; liked versus disliked, outgroup versus in-group member; e.g., Hodson, Rush, & MacInnis, 2010) that could also explain variation in the degree to which relational aggression is related to humor during early adolescence and should be considered in future research.

The most significant findings of this investigation were that peer-perceptions of humor emerged as a significant mediator of the relation between Wave 1 relational aggression and popularity at Wave 1 and Wave 2 (when not controlling for Wave 1 popularity). And, no tests of indirect effects in the alternative causal models were significant. Thus, it appears that humor helps to explain, in part, why some relationally aggressive young adolescents are able to obtain high popular status with peers. There are at least two possible explanations that might account for the mediation effect. First, relationally aggressive young adolescents may become popular with peers simply because their relationally aggressive behaviors are viewed as funny, and engaging in humorous behaviors is valued by peers and one way to achieve popularity with peers during adolescence (Masten, 1986; Ziv, 1981). Second, relationally aggressive young adolescents may become popular with peers because they also engage in other non-relationally aggressive behaviors that are viewed as humorous and valued by the peer group.

It should be acknowledged, however, that significant mediation was not found in the Wave 2 concurrent or the longitudinal model in which earlier popularity was controlled. Mediation was not significant in the Wave 2 model, perhaps because the perception of relational aggression as harmful (and awareness of its consequences) steadily increases throughout the school year. There is still much to be learned about when and why humor mediates the association between relational aggression and humor, but the difference between the results from the Wave 1 and Wave 2 concurrent models highlight the importance of considering the linkages between relational aggression, humor, and popularity at different times during the academic school year in future research.

The lack of significant mediation in the longitudinal model controlling for earlier popularity suggests that humor is not a mechanism of change in popularity associated with relational aggression, particularly across a 3 month period. Indeed, factors that are more obvious and visible than humor, such as overt forms of delinquency and rule-breaking (e.g., alcohol use), may better account for the short-term changes in the popularity of relationally aggressive youth found in this study. These results also could be attributed to the timing of the relational aggression and popularity assessments. It would have been preferable to statistically control for popularity that was assessed prior to the assessment of relational aggression. Nevertheless, we believe that the study findings are newsworthy in their suggestion that: (1) humor may be important for young adolescents’ attainment of (but not gains in) popularity, particularly in the middle of the school year, and (2) humor should be more carefully considered in future studies on relational aggression and popularity during early adolescence.

A first limitation of this study was its short-term two wave longitudinal design. Behaviors and peer reputations tend to be stable across several months (Crick et al, 2006; Prinstein, Rancourt, Guerry, & Browne, 2009), and a longer-term longitudinal design may have revealed additional change, and perhaps also significant mediation in the longitudinal model predicting change in popularity. A three-wave study would have provided a statistically stronger test of mediation and the study hypotheses (MacKinnon, 2008). A related measurement limitation is that our single-item assessment of humor likely underrepresented the complex nature of the construct, as evidenced by the research with adolescents and adults in which different forms and functions of humor have been revealed (e.g., Martin, Puhlik-Doris, Larsen, Gray, & Weir, 2003)). In addition, no definition of humor was provided to the participants. Yet, it is likely that the participants differed in their evaluations of what constitutes a “good sense of humor,” which may have impacted the study findings. Another limitation is the sample, which was fairly homogeneous in age and ethnicity, and from one geographic location. The current findings should be replicated with more diverse samples to determine whether the associations between relational aggression, humor, and popularity vary or are similar across different developmental periods, cultures, and geographic locations.

Understanding how humor relates to relational aggression and popularity may have several important applied implications. For example, the linkages between relational aggression, humor, and popularity found in this study suggest that it may be helpful to educate young adolescents about the destructive nature of seemingly funny jokes and comments at the expense of others. In such teachings, it might be especially important to focus on the relationally aggressive behavior of boys and between friends, and how such behaviors are harmful (and not humorous). School interventions aimed at decreasing relationally aggressive behavior (e.g., Leff et al, 2010) may also consider including examples of behavior that straddles the line between harmful and humorous, particularly during the middle of the school year when relational aggression appears to be most strongly associated with peer-perceptions of humor. Moreover, depending on the type and how it is used, humor can have either favorable or detrimental implications for individual adjustment (Martin et al, 2003). Although the present study was unable to tease apart whether humor was independent from or entwined with relationally aggressive behavior, past research has indicated that young adolescents who use negative forms of humor, such as aggressive or self-deprecating humor, may do so to avoid coping with negative feelings and situations (Führ, 2002), and are at heightened risk for experiencing psychological distress (Erickson & Feldstein, 2007; Martin et al, 2003). However, humor can also be used to foster relationships with others (i.e., affiliative humor), enhance self-concept and self-esteem (Cameron et al, 2010; Martin et al, 2003; Ziv, 1981), and to cope with developmental stressors (Cameron et al, 2010; Erickson & Feldstein, 2007; Martin et al, 2003). Thus, providing young adolescents with examples of humor associated with these “positive” outcomes as opposed to aggressive forms of humor may help to attenuate its association with relational aggression and teach young adolescents that it is possible to be funny and be popular amongst peers without hurting others.

Conclusions

This study takes a first step toward understanding why relationally aggressive young adolescents are able to achieve popularity, implicating humor as one mechanism. It was noteworthy that humor was not a significant mediator in the concurrent Wave 2 model or after controlling for prior popularity, suggesting that humor may be a stronger mediator in the middle relative to the end of the school year and not responsible for changes in popularity over time. The results also indicated that relationally aggressive boys and relationally aggressive young adolescents with highly relationally aggressive friends are perceived as more humorous than relationally aggressive girls and those without highly relationally aggressive friends. Even though being perceived as funny could be seen as desirable during early adolescence (e.g., Masten, 1986), findings from this study suggest that humor might also be a developmental risk factor when paired with relational aggression. Thus, the efficacy of programs aimed at reducing relational aggression may be enhanced with specific instruction about why relationally aggressive youth and their behavior should not be viewed as funny. The findings further suggest that new research insight about why harmful behaviors such as relational aggression are socially rewarded may be gained by more careful consideration of how such behaviors are interpreted, received, and responded to by young adolescents, and how relationship (e.g., friends’ characteristics) and individual factors (e.g., gender) impact such evaluations.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the students, principals, teachers, and counselors who participated in this study and funding by NICHD (1R03 HD056524-01; PI: Julie Bowker). Matt Bowker is also acknowledged for his helpful comments on an earlier draft.

Biographies

Dr. Julie Bowker received her BS in Human Development from Cornell University and her PhD in Human Development from the University of Maryland, College Park. She is currently an Associate Professor of Psychology at the University at Buffalo, SUNY. Her research program focuses on the roles that peer relationships, particularly friendships, play in social and emotional development during late childhood and early adolescence.

Rebecca Etkin is a clinical doctoral student at the University at Buffalo, SUNY. Her research interests focus on the interplay between family and peer relationships when predicting adolescent adjustment.

Footnotes

Author contributions

JB conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, performed the statistical analyses, and drafted the manuscript; RE participated in the design and interpretation of the data and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA US: Sage Publications, Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Asher SR, Parker JG, Walker DL. Distinguishing friendship from acceptance: Implications for intervention and assessment. In: Bukowski WM, Newcomb AF, Hartup WW, editors. The company they keep: Friendship in childhood and adolescence. New York, NY US: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 366–405. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A, Walters RH. Social learning and personality development. New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Björkqvist K, Lagerspetz K. Children's experience of three types of cartoon at two age levels. International Journal of Psychology. 1985;20:77–93. doi: 10.1002/j.1464-066X.1985.tb00015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin M, Dodge KA, Coie JD. Individual-group behavioral similarity and peer status in experimental play groups of boys: The social misfit revisited. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1995;69:269–279. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.2.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowker JC, Ostrov JM, Raja R. Relational and overt aggression in urban India: Associations with peer relations and best friends’ aggression. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2012;36:107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Bressler ER, Balshine S. The influence of humor on desirability. Evolution and Human Behavior. 2006;27:29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski WM, Hoza B, Boivin M. Measuring friendship quality during pre- and early adolescence: The development and psychometric properties of the Friendship Qualities Scale. Journal of Social And Personal Relationships. 1994;11:471–484. [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski WM, Sippola LK, Newcomb AF. Variations in patterns of attraction of same- and other-sex peers during early adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:147–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron E, Fox JD, Anderson MS, Cameron C. Resilient youths use humor to enhance socioemotional functioning during a day in the life. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2010;25:716–742. [Google Scholar]

- Chang L. The role of classroom norms in contextualizing the relations of children’s social behaviors to peer acceptance. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:691–702. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.5.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cillessen AH. Sociometric methods. In: Rubin HK, Bukowski WM, Laursen B, editors. Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups. New York: Guilford; 2009. pp. 82–99. [Google Scholar]

- Cillessen AHN, Mayeux L. From censure to reinforcement: Developmental changes in the association between aggression and social status. Child Development. 2004;75:147–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Closson LM. Status and gender differences in early adolescents’ descriptions of popularity. Social Development. 2009;18:412–426. [Google Scholar]

- Coie J, Dodge K, Coppotelli H. Dimensions and types of social status: A cross-age perspective. Developmental Psychology. 1982;18:557–570. [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Dodge KA, Kupersmidt JB. Peer group behavior and social status. In: Asher SR, Coie JD, editors. Peer rejection in childhood. New York, NY US: Cambridge University Press; 1990. pp. 17–59. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne SM, Archer J, Eslea M. 'We're Not Friends Anymore! Unless…’: The Frequency and Harmfulness of Indirect, Relational, and Social Aggression. Aggressive Behavior. 2006;32:294–307. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne SM, Ridge R, Stevens M, Callister M, Stockdale L. Backbiting and bloodshed in books: Short-term effects of reading physical and relational aggression in literature. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2012;51:188–196. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.2011.02053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Casas JF, Mosher M. Relational and overt aggression in preschool. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:579–588. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.4.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Bigbee MA, Howes C. Gender differences in children's normative beliefs about aggression: How do I hurt thee? Let me count the ways. Child Development. 1996;67:1003–1014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Murray-Close D, Marks PEL, Mohajeri-Nelson N. Aggression and peer relationships in school-age children: Relational and physical aggression in group and dyadic contexts. In: Rubin KH, Bukowski WM, Laursen B, editors. Handbook of peer interactions, relationships and groups. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2009. pp. 287–302. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Nelson DA. Relational and physical victimization within friendships: Nobody told me there’d be friends like these. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:599–607. doi: 10.1023/a:1020811714064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Ostrov JM, Werner NE. A longitudinal study of relational aggression, physical aggression, and children’s social-psychological adjustment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:131–142. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-9009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desjardins T, Leadbeater B. Relational victimization and depressive symptoms in adolescence: Moderating effects of mothers, father and peer emotional support. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011:531–544. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9562-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Spracklen KM, Andrews DW, Patterson GR. Deviancy training in male adolescents friendships. Behavior Therapy. 1996;27:373–390. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Coie JD. Social information processing factors in reactive and proactive aggression in children’s peer groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;53:1146–1158. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.53.6.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson SJ, Feldstein SW. Adolescent humor and its relationship to coping, defense strategies, psychological distress, and well-being. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2007;37:255–271. doi: 10.1007/s10578-006-0034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French DC, Jansen EA, Pidada S. United States and Indonesian children's and adolescents' reports of relational aggression by disliked peers. Child Development. 2002;73:1143–1150. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Führ M. Coping humor in early adolescence. Humor: International Journal of Humor Research. 2002;15:283–304. [Google Scholar]

- Geisler FM, Weber H. Harm that does not hurt: Humour in coping with self-threat. Motivation and Emotion. 2010;34:446–456. [Google Scholar]

- Gest SD, Graham-Bermann SA, Hartup WW. Peer experience: Common and unique features of number of friendships, social network centrality, and sociometric status. Social Development. 2001;10:23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. New York: The Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hodson G, Rush J, MacInnis CC. A joke is just a joke (except when it isn't): Cavalier humor beliefs facilitate the expression of group dominance motives. Journal of Personality And Social Psychology. 2010;99:660–682. doi: 10.1037/a0019627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, Kuiper NA. Humor styles, peer relationships, and bullying in middle childhood. Humor: International Journal of Humor Research. 2006;19:383–404. [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Skinner AT, Sorbring E, Giunta LD, Dodge KA, Malone PS, Oburu P, et al. Boys’ and girls’ relational and physical aggression in nine countries. Aggressive Behavior. 2012;38:298–308. doi: 10.1002/ab.21433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lease A, Musgrove KT, Axelrod JL. Dimensions of social status in preadolescent peer groups: Likability, perceived popularity, and social dominance. Social Development. 2002;11:508–533. [Google Scholar]

- Leff SS, Crick NR. Interventions for relational aggression: Innovative programming and next steps in research and practice. School Psychology Review. 2010;39:504–507. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leff SS, Waasdorp TE, Paskewich B, Gullan RL, Jawad AF, MacEvoy JP, Feinberg BE, Power TJ. The Preventing Relational Aggression in Schools Everyday Program: A preliminary evaluation of acceptability and impact. School Psychology Review. 2010;39:569–587. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group/Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Martin RA, Puhlik-Doris P, Larsen G, Gray J, Weir K. Individual differences in uses of humor and their relation to psychological well-being: Development of the Humor Styles Questionnaire. Journal of Research In Personality. 2003;37:48–75. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS. Humor and competence in school-aged children. Child Development. 1986;57:461–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1986.tb00045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayeux L, Cillessen AN. It's not just being popular, it's knowing it, too: The role of self-perceptions of status in the associations between peer status and aggression. Social Development. 2008;17:871–888. [Google Scholar]

- Mishna F, Cook C, Gadalla T, Daciuk J, Solomon S. Cyber bullying behaviors among middle and high school students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2010;80:362–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review. 1993;100:674–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundorf N, Bhatia A, Zillman D, Lester P, Robertson S. Gender differences in humor appreciation. Humor: International Journal of Humor Research. 1988;1:231–243. [Google Scholar]

- Murray-Close D, Ostrov JM. A longitudinal study of forms and functions of aggressive behavior in early childhood. Child Development. 2009;80:828–842. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon CL, Linkie CA, Coleman PK, Fitch C. Peer relational victimization and somatic complaints during adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;49:294–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrov JM, Godleski SA. Toward an integrated gender-linked model of aggression subtypes in early and middle childhood. Psychological Review. 2010;117:233–242. doi: 10.1037/a0018070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape H, Hammer T. How does young people’s alcohol consumption change during the transition to early adulthood? A longitudinal study of changes at aggregate and individual level. Addiction. 1996;91:1345–1357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JG, Asher SR. Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: Links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:611–621. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Dishion TJ, Yoerger K. Adolescent growth in new forms of problem behavior: Macro- and micro-peer dynamics. Prevention Science. 2000;1:3–13. doi: 10.1023/a:1010019915400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Brechwald WA, Cohen GL. Susceptibility to peer influence: Using a performance-based measure to identify adolescent males at heightened risk for deviant peer socialization. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:1167–1172. doi: 10.1037/a0023274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Rancourt D, Guerry JD, Browne CB. Peer reputations and psychological adjustment. In: Rubin KH, Bukowski WM, Laursen B, editors. Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 2009. pp. 548–567. [Google Scholar]

- Ransohoff R. Some observations on humor and laughter in young adolescent girls. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1975;4:155–170. doi: 10.1007/BF01537439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, Swenson LP, Waller EM. Overt and relational aggression and perceived popularity: Developmental differences in concurrent and prospective relations. Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:378–387. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.3.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanford S, Eder D. Adolescent humor during peer interaction. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1984;47:235–243. [Google Scholar]

- Smith RL, Rose AJ, Schwartz-Mette RA. Relational and overt aggression in childhood and adolescence: Clarifying mean-level gender differences and associations with peer acceptance. Social Development. 2010;19:243–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00541.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J, Prichard J, Schrepferman L, Patrick M, Stoolmiller M. Child impulsiveness-inattention, early peer experiences, and the development of early onset conduct problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:579–594. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000047208.23845.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teunissen H, Spijkerman R, Prinstein MJ, Cohen G, Engels RCME, Scholte RHJ. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2012;36:1257–1267. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01728.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tragesser SL, Lippman LG. Teasing: for superiority or solidarity? Journal of General Psychology. 2005;132:255–266. doi: 10.3200/GENP.132.3.255-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillancourt T, Hymel S. Aggression and social status: The moderating roles of sex and peer-valued characteristics. Aggressive Behavior. 2006;32:396–408. [Google Scholar]

- Veatch TC. A theory of humor. Humor. 1998;11:161–215. [Google Scholar]

- Werner NE, Crick NR. Maladaptive peer relationships and the development of relational and physical aggression during middle childhood. Social Development. 2004;13:495–514. [Google Scholar]

- Werner NE, Hill LG. Individual and peer group normative beliefs about relational aggression. Child Development. 2010;81:826–836. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You J, Bellmore A. Relational peer victimization and psychosocial adjustment: The mediating role of best friendship qualities. Personal Relationships. 2012;19:340–353. [Google Scholar]

- Ziv A. The self concept of adolescent humorists. Journal of Adolescence. 1981;4:187–197. doi: 10.1016/s0140-1971(81)80038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]