Abstract

Aims

Relatively little is known about the use of medication for the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) events in China, and the relevance to it of socioeconomic, lifestyle and health-related factors.

Methods and results

We analysed cross-sectional data from the China Kadoorie Biobank (CKB) of 512,891 adults aged 30–79 years recruited from 1737 rural and urban communities in China. Information about doctor-diagnosed ischaemic heart disease (IHD) and stroke, and the use of medication for the secondary prevention of CVD events, were recorded by interview. Multivariate logistic regression was used to estimate odds ratios (ORs) for use of secondary preventive treatment, adjusting simultaneously for age, sex, area and education. Overall, 23,129 (4.5%) participants reported a history of CVD (3.0% IHD, 1.7% stroke). Among them, 35% reported current use of any of 6 classes of drug (anti-platelet, statins, diuretics, ACE-I, β-blockers or calcium-channel blockers) for the prevention of CVD events, with the rate of usage greater in those with older age, higher levels of income, education, BMI or blood pressure. The use of these agents was associated positively with history of diagnosed hypertension (OR 7.5; 95% confidence intervals: 7.08–8.06) and diabetes (1.40; 1.28–1.52) and inversely with self-rated health status, but there was no association with years since diagnosis.

Conclusions

Despite recent improvements in hospital care in China, only one in three individuals with prior CVD was routinely treated with any proven secondary preventive drugs. The treatment rates were correlated with the existence of other risk factors, in particular evidence of hypertension.

Keywords: Ischemic heart disease, Stroke, Secondary prevention, Cardiovascular medication, Rural and urban communities, China

1. Introduction

Worldwide, about 17 million people die from cardiovascular disease (CVD) each year, chiefly from ischemic heart disease (IHD) and stroke, with about three-quarters of these deaths now occurring in low- or middle-income countries, including China [1–3]. In most Western countries, the mortality rates from CVD have declined progressively in the last few decades, due partly to widespread and long-term use of proven medication, such as antiplatelet therapy, statins, β-blockers and ACE-inhibitors (ACE-I), for the secondary prevention of CVD events, and partly due to favourable changes in underlying risk factors, such as smoking and dietary patterns [4–9]. Although the acute hospital management of patients with CVD in China is generally similar to that in most Western countries [10], relatively little is known about the use of drug treatment for secondary prevention of CVD events in the community in China. We examined cross-sectional data about the use of medication for secondary prevention of CVD (which is defined as IHD and or stroke throughout this paper) among adults who were recruited in the China Kadoorie Biobank (CKB) Study from over 1737 rural and urban communities in China [11,12]. The aims of the present study were to examine the use of six specific classes of drug treatment for secondary prevention of CVD and relevance to it of a range of demographic, socioeconomic, lifestyle and health-related factors.

2. Methods

2.1. Study participants

The present study population consisted of 23 129 participants in the CKB who reported having a history of doctor-diagnosed IHD and/or stroke (including transient ischemic attack [TIA]) at the baseline survey. Details of the design, survey methods and baseline characteristics of the CKB participants have been reported previously [11,12]. In brief, the CKB study involved 512 891 people who were recruited during 2004–8 from 1737 communities in 10 geographically diverse regions (5 urban and 5 rural) of China, chosen according to local disease patterns, exposure to certain risk factors, population stability, quality of death and disease registries, local commitment and capacity. In each region, all men and women aged 35–74 years were identified through official residential records and invited to attend study clinics set up specifically in local residential community centres (with a small number slightly outside of this age range when recruited).

2.2. Data collection

The baseline survey included a face-to-face interview by trained study staff with a laptop-administrated questionnaire, physical examination (e.g., height, weight, blood pressure, heart rate and lung function) and collection of blood for storage and future analysis. At the interview, apart from a range of questions related to demographic and lifestyle factors (e.g., smoking, alcohol, diet and physical activity) a detailed medical history was sought from participants, with the question: “Has a doctor EVER told you that you had the following disease?” followed by a list of about 20 major conditions, including IHD and stroke. If a study participant had a prior history of IHD and/or stroke, they were then asked about the age of first diagnosis and whether they were currently taking any drug treatment, and if so, whether this included any of six specific classes of drug (anti-platelet, statins, diuretics, ACE-I, β-blockers and calcium-channel blockers) that are used for the secondary prevention of CVD events. To facilitate the recording of drugs that were used a detailed list of possible drug names (including generic and commercial names) for each of these six classes of drug was provided to participants. All participants provided written informed consent to take part in the CKB study. Ethics approvals were obtained from Central Ethical Committee of the Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Beijing, China, and the University of Oxford UK, as well as from the Institutional Research Boards in the 10 study regions.

2.3. Statistical analysis

The proportions of participants with prior CVD who were using the six classes of drug were calculated separately for participants who had either IHD or stroke, or both, and were adjusted for age, gender, geographical region and education. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to estimate rates of use of these drugs, calculate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) among participants with prior CVD both overall and for IHD or stroke, in different categories of baseline variables (including CVD risk factors). Odds ratio (and 95% CI) of use of six proven CVD medications by levels of systolic blood pressure (SBP) were estimated for each group relative to the lowest and are shown as “floating absolute risks” (which does not alter their values but merely ascribes a 95% confidence interval [CI] to the RR in every group) [13]. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 (SAS institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the study population

Overall, 23 129 (4.5%) of the CKB participants reported a prior history of CVD, including 15 472 (3.0%) with IHD and 8884 (1.7%) with stroke (Table 1). The prevalence of IHD was higher in women (3.4%) than in men (2.5%) and, consistently, also in those with higher levels of education or of household income (Table 1). For stroke, the prevalence was higher in men (2.2%) than women (1.4%) and, in contrast to IHD, in those with lower levels of education and income. The prevalence of IHD and stroke were both strongly and positively associated with increasing levels of systolic blood pressure and body mass index (BMI) (Table 1). Participants who had poor self-rated health status had a higher prevalence of either IHD or stroke (14.1%) compared with those who had good self-rated health status (2.0%).

Table 1.

Selected baseline characteristics of study participants, by history of IHD, stroke and either or both.

| All (n = 512 891) |

History of IHD (n = 15 472) |

History of stroke (n = 8884) |

History of either or both (n = 23 129) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | No. | (%)a | No. | (%)a | No. | (%)a | |

| Age (years) | |||||||

| < 50 | 230 553 | 1510 | (0.6) | 798 | (0.4) | 2277 | (1.0) |

| 50–59 | 157 556 | 4502 | (3.0) | 2690 | (1.8) | 6938 | (4.6) |

| 60–69 | 91 771 | 6416 | (7.0) | 3664 | (4.0) | 9481 | (10.4) |

| 70–79 | 33 011 | 3044 | (8.6) | 1732 | (4.6) | 4433 | (12.5) |

| Mean (SD) | 61.4 (8.7) | 61.5 (8.4) | 61.2 (8.6) | ||||

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 210 222 | 5714 | (2.5) | 4912 | (2.2) | 10 069 | (4.5) |

| Female | 302 669 | 9758 | (3.4) | 3972 | (1.4) | 13 060 | (4.5) |

| Region | |||||||

| Rural | 286 705 | 4963 | (2.8) | 3615 | (1.2) | 8347 | (3.8) |

| Urban | 226 186 | 10 509 | (3.3) | 5269 | (2.4) | 14 782 | (5.3) |

| Education | |||||||

| No formal school | 95 221 | 2399 | (2.3) | 1518 | (1.7) | 3758 | (3.7) |

| Primary school | 165 216 | 4958 | (2.9) | 3053 | (1.8) | 7689 | (4.5) |

| Middle school | 144 913 | 3804 | (3.2) | 2322 | (1.8) | 5783 | (4.7) |

| High school | 77 527 | 2645 | (3.7) | 1292 | (1.6) | 3712 | (5.0) |

| College/university | 30 014 | 1666 | (3.9) | 699 | (1.3) | 2187 | (4.9) |

| Household income (Yuan/year) | |||||||

| < 4999 | 50 203 | 1232 | (2.6) | 1133 | (2.0) | 2272 | (4.4) |

| 5000–9999 | 94 629 | 2263 | (2.8) | 1505 | (1.9) | 3630 | (4.5) |

| 10 000–19 999 | 149 013 | 5099 | (3.0) | 2937 | (1.8) | 7625 | (4.5) |

| 20 000–34 999 | 126 721 | 4101 | (3.1) | 2026 | (1.6) | 5781 | (4.5) |

| 35 000 + | 92 325 | 2777 | (3.4) | 1283 | (1.5) | 3821 | (4.7) |

| Cigarette smoking | |||||||

| Never | 317 614 | 10 079 | (3.1) | 4458 | (1.7) | 13 845 | (4.5) |

| Ex | 30 563 | 1901 | (4.4) | 1612 | (2.9) | 3274 | (7.1) |

| Current | 164 714 | 3492 | (2.7) | 2814 | (1.6) | 6010 | (4.0) |

| Alcohol drinking | |||||||

| Never | 235 199 | 7853 | (3.4) | 4024 | (2.2) | 11 270 | (5.4) |

| Ex | 9256 | 647 | (6.6) | 754 | (6.3) | 1317 | (13.1) |

| Current | 268 436 | 6972 | (2.5) | 4106 | (1.2) | 10 542 | (3.5) |

| SBP (mm Hg) | |||||||

| < 120 | 163 260 | 3046 | (2.5) | 1065 | (0.9) | 3950 | (3.2) |

| 120–139 | 201 619 | 5578 | (3.1) | 2851 | (1.6) | 8050 | (4.5) |

| 140–159 | 96 713 | 4185 | (3.5) | 2731 | (2.4) | 6517 | (5.6) |

| 160 + | 51 299 | 2663 | (3.7) | 2237 | (3.5) | 4612 | (6.8) |

| Mean (SD) | 140.0 (22.6) | 145.5 (23.6) | 141.2 (23.1) | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||||

| < 22.0 | 168 547 | 3000 | (2.0) | 1901 | (1.2) | 4720 | (3.1) |

| 22.0–24.9 | 175 414 | 4660 | (2.9) | 2953 | (1.8) | 7240 | (4.4) |

| 25.0–26.9 | 85 856 | 3255 | (3.6) | 1853 | (2.1) | 4846 | (5.4) |

| 27 + | 83 074 | 4557 | (4.6) | 2177 | (2.4) | 6323 | (6.7) |

| Mean (SD) | 25.1 (3.7) | 24.7 (3.4) | 24.9 (3.6) | ||||

| Self-reported hypertension | 59 703 | 6749 | (8.6) | 5212 | (7.6) | 11 141 | (15.7) |

| Self-reported diabetes | 16 162 | 2053 | (6.9) | 1107 | (4.0) | 2849 | (10.3) |

| Self-rated poor health status | 53 105 | 4297 | (8.4) | 3300 | (6.2) | 7028 | (14.1) |

| Short of breath during walking | 30 351 | 3341 | (10.8) | 1274 | (3.9) | 4305 | (14.1) |

Adjusted for age, gender, region and education except when the variable is in question.

3.2. Use of proven drug therapy in participants with prior CVD

Among participants with a prior history of CVD (IHD and/or stroke), the median interval since diagnosis was 5.0 (IQR 2.0–10.0) years and about half of them (55.5%) reported current use of any drug treatment, but only about one-third (35.3%) reported current use of any of the six proven categories of drug treatment for CVD event prevention (Table 2). Among these six drug categories, the reported current use were 1.4% for statins, 2.3% for diuretics, 7.6% for ACE-I, 10.1% for β-blockers, 10.6% for anti-platelet (chiefly aspirin) and 18.2% for calcium channel blockers. Only 9% of these high-risk patients reported concurrent use of two of these drug categories and 2.7% reported concurrent use of three or more. There was little difference in the proportions having individual or combined use of such treatments between those with IHD and stroke.

Table 2.

Use of any secondary prevention drug treatment among participants with a prior history of IHD, stroke and either or both at baseline.

| IHD (n = 15 472) |

Stroke (n = 8884) |

Either or both (n = 23 129) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | (%) | No. | (%) | No. | (%) | |

| Any treatment | 8739 | (56.4) | 4598 | (51.8) | 12 841 | (55.5) |

| Any of six drugs | 5382 | (34.8) | 3396 | (38.2) | 8156 | (35.3) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 2722 | (17.6) | 1824 | (20.5) | 4211 | (18.2) |

| β-Blockers | 1903 | (12.3) | 634 | (7.1) | 2341 | (10.1) |

| ACE-I | 1045 | (6.8) | 857 | (9.6) | 1761 | (7.6) |

| Diuretics | 351 | (2.3) | 246 | (2.8) | 536 | (2.3) |

| Anti-platelet | 1557 | (10.1) | 1098 | (12.4) | 2447 | (10.6) |

| Statins | 215 | (1.4) | 137 | (1.5) | 319 | (1.4) |

| Year since diagnosis Median (IQR) |

6.5 (2.5–11.5) | 4.5 (1.5–8.5) | 5.0 (2.0–10.0) | |||

3.3. Correlate of use of secondary prevention treatments for CVD

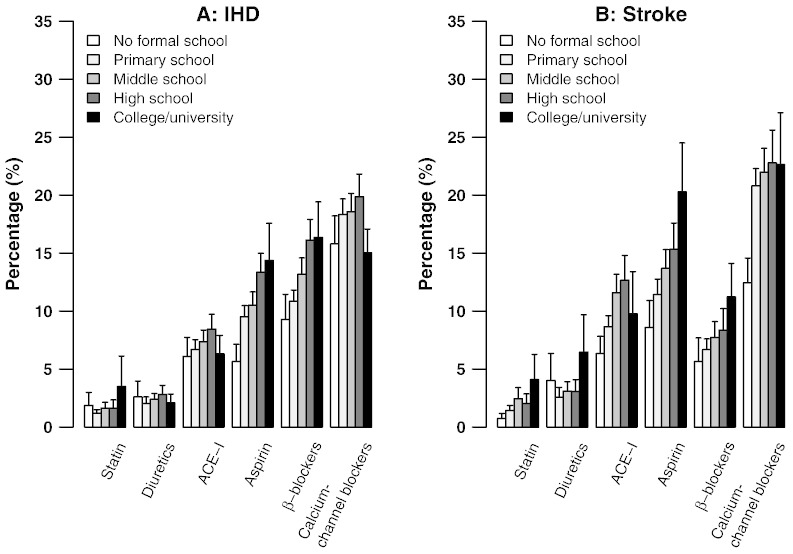

Table 3 shows the OR (and 95% CI) for use of any of the six proven drug treatment categories by demographic factors (age, gender and region) and socioeconomic status (education level, annual household income) among people with prior CVD adjusted for age, gender, region and education except that when the variable is in question. For IHD, all else being equal, there was lower usage among younger people (e.g., OR 0.44; 95% CI: 0.39–0.50 for < 50 years versus 70 + years), in women (0.87; 0.80–0.93), and in those living in urban areas (0.78; 0.72–0.85). Less education was associated strongly with less use of any of the six established drug treatments, and of each specific drug category, for both IHD (Fig. 1, left) and stroke (Fig. 1, right). By contrast, annual household income was positively associated with use of any of the six drug treatments (Table 3).

Table 3.

Use of any secondary prevention drug treatment among participants with a prior history of IHD, stroke and either or both at baseline by demographic and socioeconomic characteristics.

| Baseline measure | IHD (n = 15 472) |

Stroke (n = 8 884) |

Either or both (n = 23 129) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | %a | OR (95% CI)a | No. | %a | OR (95% CI)a | No. | %a | OR (95% CI)a | |

| Age group (years) | |||||||||

| < 50 | 362 | 22.6 | 0.44 (0.39–0.50) | 306 | 34.6 | 0.81 (0.69–0.94) | 652 | 26.3 | 0.56 (0.51–0.62) |

| 50–59 | 1471 | 31.7 | 0.71 (0.66–0.75) | 1 057 | 37.7 | 0.92 (0.85–1.00) | 2 397 | 33.3 | 0.78 (0.75–0.82) |

| 60–69 | 2395 | 37.5 | 0.91 (0.87–0.96) | 1 407 | 38.7 | 0.96 (0.90–1.03) | 3 496 | 37.1 | 0.93 (0.89–0.97) |

| 70 + | 1154 | 39.6 | 1.00 (0.92–1.09) | 626 | 39.7 | 1.00 (0.90–1.11) | 1 611 | 38.9 | 1.00 (0.93–1.07) |

| P (Trend) | < 0.0001 | 0.14 | < 0.0001 | ||||||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 2207 | 36.8 | 1.00 | 1 913 | 37.4 | 1.00 | 3 823 | 36.3 | 1.00 |

| Female | 3175 | 33.6 | 0.87 (0.80–0.93) | 1 483 | 39.2 | 1.08 (0.98–1.19) | 4 333 | 34.4 | 0.92 (0.87–0.98) |

| P (Heterogeneity) | < 0.0001 | 0.11 | < 0.01 | ||||||

| Region | |||||||||

| Rural | 1807 | 38.6 | 1.00 | 1 607 | 46.8 | 1.00 | 3 264 | 41.3 | 1.00 |

| Urban | 3575 | 33.0 | 0.78 (0.72–0.85) | 1 789 | 32.4 | 0.54 (0.49–0.60) | 4 892 | 31.9 | 0.67 (0.62–0.71) |

| P (Heterogeneity) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||

| Education level | |||||||||

| No formal | 684 | 26.6 | 1.00 (0.90–1.11) | 471 | 27.3 | 1.00 (0.87–1.15) | 1 080 | 26.0 | 1.00 (0.92–1.09) |

| Primary | 1830 | 33.7 | 1.40 (1.32–1.50) | 1 242 | 36.1 | 1.51 (1.39–1.63) | 2 887 | 33.8 | 1.45 (1.38–1.53) |

| Middle | 1335 | 37.1 | 1.63 (1.52–1.74) | 895 | 41.2 | 1.87 (1.71–2.04) | 2 069 | 38.0 | 1.74 (1.65–1.84) |

| High | 974 | 39.7 | 1.82 (1.68–1.98) | 527 | 46.1 | 2.28 (2.02–2.56) | 1 389 | 41.2 | 1.99 (1.86–2.14) |

| College/university | 559 | 36.6 | 1.59 (1.43–1.78) | 261 | 46.7 | 2.33 (1.98–2.75) | 731 | 38.8 | 1.80 (1.64–1.99) |

| P (Heterogeneity) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||

| Household income (Yuan/year) | |||||||||

| < 4999 | 361 | 27.7 | 1.00 (0.87–1.14) | 415 | 34.5 | 1.00 (0.87–1.15) | 735 | 30.2 | 1.00 (0.91–1.10) |

| 5000–9999 | 744 | 32.6 | 1.26 (1.15–1.38) | 601 | 38.0 | 1.16 (1.04–1.30) | 1 276 | 34.3 | 1.21 (1.12–1.30) |

| 10 000–19 999 | 1826 | 35.7 | 1.45 (1.36–1.53) | 1 091 | 37.5 | 1.14 (1.05–1.23) | 2 700 | 35.4 | 1.27 (1.21–1.33) |

| 20 000–34 999 | 1457 | 35.5 | 1.44 (1.34–1.54) | 793 | 40.2 | 1.28 (1.16–1.41) | 2 071 | 36.2 | 1.31 (1.24–1.39) |

| 35 000 + | 994 | 36.9 | 1.53 (1.39–1.67) | 496 | 40.5 | 1.29 (1.13–1.47) | 1 374 | 37.4 | 1.38 (1.28–1.49) |

| P (Trend) | < 0.0001 | 0.05 | < 0.0001 | ||||||

Adjusted for age, gender, region and education except when the variable is in question.

Fig. 1.

Percentage use of six proven CVD medication categories by level of education in participants with a history of IHD (left) or stroke (right). Vertical lines indicate 95% CIs.

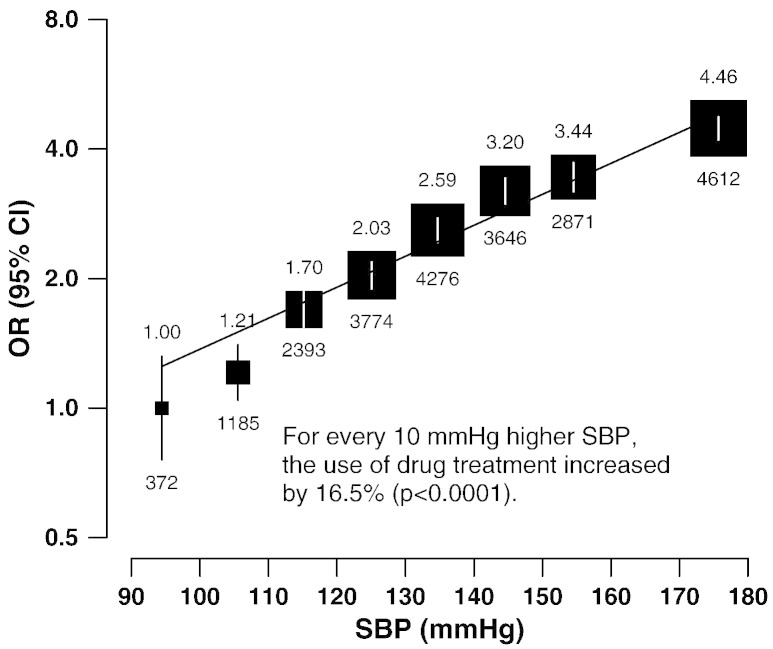

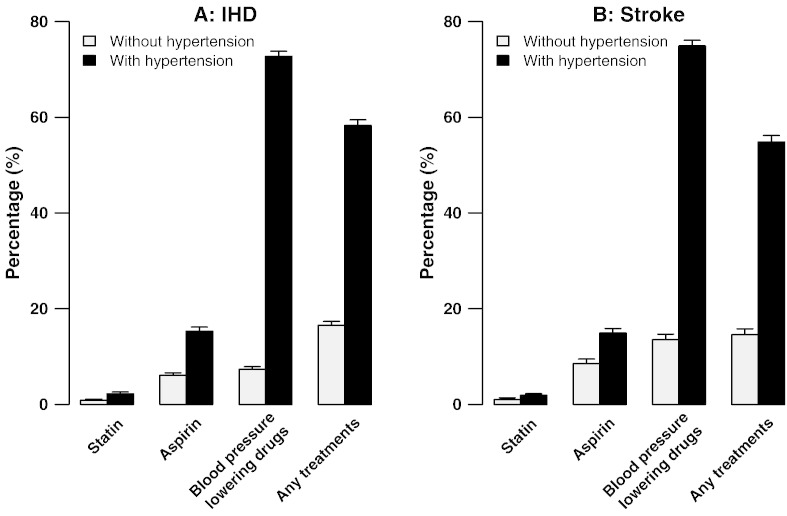

Table 4 shows the adjusted ORs for use of any of the six classes of drug by alcohol, smoking, SBP, hypertension, BMI, and diabetes mellitus (DM). Usage rates were moderately lower in current smokers (0.84; 0.79–0.89) and current drinkers (0.76; 0.73–0.79), but strongly positively associated with measured BMI and SBP (p for trend < 0.0001). For every 10 mm Hg higher baseline SBP, the use of these treatments was 16.5% higher (p < 0.0001; Fig. 2). Moreover, individuals with self-reported hypertension were almost 8 fold (7.55; 7.08–8.06) as likely to report use of such therapy as those without such a diagnosis, not only for agents with BP-lowering effects (40.7% vs 12.0%) but also for statins (2.1% vs 0.8%) and aspirin (15.4% vs 5.9%) (Fig. 3, left). The pattern was similar for participants with a history of stroke (Fig. 3, right). This would leave 56% of IHD patients and 41% of stroke patients in the present study that had not been diagnosed previously with hypertension under-treated despite a high risk of recurrence of IHD or stroke. Higher use of these six drugs also was associated with prior history of DM (1.40; 1.48–1.52) and the pattern was similar for participants with a history of stroke and/or IHD. Years of diagnosis has no significant effect in the use of the six drugs among participants with a history of either IHD or stroke (Table 4). Health status self-rated as good was strongly associated with lower use of the six drugs in individuals with prior IHD (0.52; 0.48–0.57) or stroke (0.58; 0.52–0.65).

Table 4.

Odds ratios for use of any secondary prevention drug treatment by lifestyle and physical measurements.

| IHD (n = 15 472) (n = 5 382) |

Stroke (n = 8 884) |

Either or both (n = 23 129) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | %a | OR (95% CI)a | No. | %a | OR (95% CI)a | No. | %a | OR (95% CI)a | |

| Cigarette smoking | |||||||||

| Never | 3431 | 35.8 | 1.00 (0.92–1.09) | 1711 | 38.6 | 1.00 (0.89–1.12) | 4785 | 36.0 | 1.00 (0.93–1.08) |

| Ex | 761 | 36.9 | 1.05 (0.95–1.15) | 662 | 42.5 | 1.17 (1.06–1.30) | 1299 | 38.3 | 1.11 (1.03–1.19) |

| Current | 1190 | 30.8 | 0.80 (0.74–0.86) | 1023 | 35.1 | 0.86 (0.79–0.93) | 2072 | 32.0 | 0.84 (0.79–0.89) |

| P (Trend) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||

| Alcohol drinking | |||||||||

| Never | 2899 | 40.6 | 1.00 (0.94–1.06) | 1632 | 39.9 | 1.00 (0.92–1.08) | 4215 | 37.8 | 1.00 (0.95–1.05) |

| Ex | 287 | 30.9 | 1.13 (0.96–1.33) | 351 | 46.6 | 1.32 (1.13–1.54) | 590 | 42.9 | 1.23 (1.10–1.38) |

| Current | 2 196 | 34.8 | 0.74 (0.70–0.78) | 1413 | 35.1 | 0.81 (0.76–0.87) | 3351 | 31.6 | 0.76 (0.73–0.79) |

| P (Heterogeneity) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||

| SBP (mm Hg) | |||||||||

| < 120 | 695 | 23.3 | 1.00 (0.92–1.09) | 254 | 23.6 | 1.00 (0.86–1.16) | 888 | 22.6 | 1.00 (0.93–1.08) |

| 120–139 | 1760 | 31.3 | 1.50 (1.42–1.59) | 972 | 33.9 | 1.66 (1.54–1.80) | 2560 | 31.5 | 1.57 (1.50–1.65) |

| 140–159 | 1663 | 39.5 | 2.16 (2.03–2.30) | 1116 | 41.4 | 2.29 (2.12–2.48) | 2562 | 39.5 | 2.23 (2.12–2.35) |

| 160 + | 1264 | 47.9 | 3.04 (2.80–3.29) | 1054 | 46.9 | 2.87 (2.62–3.13) | 2146 | 46.8 | 3.02 (2.84–3.20) |

| P (Trend) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||||||

| < 22.0 | 785 | 23.2 | 1.00 (0.92–1.09) | 594 | 27.2 | 1.00 (0.90–1.11) | 1308 | 24.5 | 1.00 (0.93–1.07) |

| 22.0–24.9 | 1626 | 33.8 | 1.69 (1.59–1.80) | 1097 | 36.1 | 1.52 (1.40–1.64) | 2541 | 34.0 | 1.59 (1.52–1.67) |

| 25.0–26.9 | 1173 | 36.4 | 1.89 (1.76–2.04) | 737 | 41.1 | 1.87 (1.70–2.06) | 1777 | 37.3 | 1.84 (1.73–1.95) |

| 27.0 + | 1798 | 42.3 | 2.42 (2.27–2.59) | 968 | 48.3 | 2.50 (2.28–2.74) | 2530 | 43.2 | 2.35 (2.23–2.49) |

| P (Trend) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||

| Years since diagnose | |||||||||

| < 3 | 1418 | 35.0 | 1.00 (0.94–1.07) | 1288 | 38.6 | 1.00 (0.93–1.08) | 2449 | 35.3 | 1.00 (0.95–1.05) |

| 3 to < 7 | 1518 | 34.3 | 0.97 (0.91–1.03) | 1147 | 38.9 | 1.01 (0.94–1.09) | 2448 | 35.0 | 0.99 (0.94–1.04) |

| 7 + | 2446 | 35.0 | 1.00 (0.95–1.06) | 961 | 37 | 0.93 (0.86–1.01) | 3259 | 35.4 | 1.01 (0.96–1.06) |

| P-Trend | 0.69 | 0.29 | 0.88 | ||||||

| Self-reported diabetes | |||||||||

| No | 4512 | 33.6 | 1.00 | 2914 | 37.2 | 1.00 | 6979 | 34.3 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 870 | 42.4 | 1.45 (1.32–1.60) | 482 | 45.4 | 1.41 (1.23–1.61) | 1177 | 42.2 | 1.40 (1.28–1.52) |

| P (Heterogeneity) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||

| Self-reported hypertension | |||||||||

| No | 1428 | 15.9 | 1.00 | 525 | 13.7 | 1.00 | 1861 | 15.0 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 3954 | 59.2 | 7.69 (7.10–8.31) | 2871 | 55.5 | 7.88 (7.04–8.82) | 6295 | 57.1 | 7.55 (7.08–8.06) |

| P (Heterogeneity) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||

| Self-rated health status | |||||||||

| Poor | 1777 | 42.2 | 1.00 (0.94–1.07) | 1428 | 43.1 | 1.00 (0.93–1.07) | 2883 | 41.3 | 1.00 (0.95–1.05) |

| Fair | 2744 | 33.7 | 0.70 (0.67–0.73) | 1498 | 37.2 | 0.78 (0.73–0.84) | 3992 | 34.4 | 0.74 (0.12–0.78) |

| Good | 861 | 27.5 | 0.52 (0.48–0.57) | 470 | 30.7 | 0.58 (0.52–0.65) | 1281 | 28.3 | 0.56 (0.52–0.56) |

| P (Heterogeneity) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||

Adjusted for age, gender, region and education.

Fig. 2.

Odds ratio of use of six proven CVD medication categories by levels of systolic blood pressure in participants with a history of cardiovascular disease. Numbers of people with prior CVD are also given for each group. Odds ratios are plotted on a floating absolute scale. Each closed square has an area inversely proportional to the effective variance of the log of the odds ratio. Vertical lines indicate 95% CIs.

Fig. 3.

Percentage use of six proven CVD medication categories in participants with and without doctor-diagnosed hypertension among those with IHD (left) and stroke (right). Vertical lines indicate 95% CIs.

4. Discussion

This is the largest community-based study carried out in China on the use of drug therapy for secondary prevention in people with prior IHD and stroke. It shows that only about one-third of patients with CVD in the community were taking any proven medication for secondary prevention of CVD events. The use of 6 proven drug treatments for secondary prevention of CVD was unrelated to the years since diagnosis, but associated with a number of socio-economic (especially low education), lifestyle (e.g., smoking, alcohol drinking) and physiological factors (e.g., BMI and blood pressure). The effect of blood pressure on the use of treatment was particularly striking, and those reporting having a doctor-diagnosed hypertension were almost 8 times as likely to report use of such treatment as those without such a diagnosis.

Although the reported use of various treatments for secondary prevention of IHD and stroke in the present study was generally lower than that reported in clinical settings from particular Chinese cities [14,15], our study findings are broadly consistent with the results of the PURE study [1] among 46 285 participants, aged 35–70 years recruited during 2004–9 from 115 urban and rural communities across China (in addition to participants from 16 other countries). In that study, 3070 (6.6%) of the Chinese participants reported having a history of IHD (5.2%) or stroke (1.9%) and, among them, 18.6%, 6.2%, 8.6%, 14.3%, 14.9% and 1.7%, reported taking antiplatelet drug, β-blockers, ACE-I, diuretics, calcium-channel blockers and statins [1] compared with 10.6%, 10.1%, 7.6%, 2.3%,18.2% and 1.4% respectively in the present study. In both the PURE-China study and CKB, the use of anti-platelet agents (18.6% and 10.6%) and any of the BP-lowering drugs (38.2% and 34.4%) for participants with a history of either IHD or stroke in China was much lower than participants in the PURE study from North America (antiplatelet drugs: 52.2%, BP-lowering medication: 69.2%), Middle East (49.7%, 64.3%) and South Americans (29.0%, 57.8%) and only slightly better than among participants from South Asia (9.3%, 18.8%), Malaysia (13.6%, 23.9%) and Africa (5.7%, 15.9%). In addition, there was also virtually no long-term use of statins among patients with IHD and/or stroke in the communities of China (IHD: 2% in PURE-China and 1.4% in CKB; stroke: 0.8% in both studies) during 2004–2008. These figures were similar to these for PURE in Africa (1.4% for IHD; 0% for stroke), but much lower than those observed in North America and Europe (56.7%; 38.7%).

Several factors could affect the use of drug therapy for secondary prevention of CVD events after discharge from hospital, including local treatment guidelines, doctors' knowledge and beliefs, concerns about adverse effects, uncertainty about diagnosis and disease severity, affordability, patients' awareness of the risks and self-perceived health status. Firstly, the six proven drugs for secondary prevention of CVD events selected in the present study are all recommended by Chinese guidelines, not only for IHD [16] but also for ischemic stroke and TIA [17]. Indeed, a recent nationwide survey in China found that over 95% of doctors across over 1029 different types of hospitals said that they would prescribe a statin at discharge for long-term secondary prevention of IHD or stroke [10]. So, it seems unlikely that the knowledge or beliefs of hospital doctors in China would influence its long-term use, even though there is recent evidence that use of higher doses of statins (e.g., simvastatin > 40 mg) would lead to much greater risk of myopathy in Chinese [18] than in Western populations [19]. On the other hand, the uncertainty of diagnosis and disease severity may contribute to the relatively lower use in urban than in rural areas in the present study, which is opposite to that seen in the PURE-China study [1].

As in PURE [1], we also found the use of the drug treatment was associated with socioeconomic status, smoking and alcohol drinking. The significantly lower use of medication among regular smokers or drinkers may reflect the so-called “crowding out effect” [20] where the costs of smoking and drinking compromised the allocation of expenditure for essential treatment. Although most of the CKB participants had certain health insurance cover at baseline, no specific information was available at baseline about type of health insurance cover and level of reimbursement. In China, health insurance coverage has risen rapidly during the last 10 year, from 29.7% in 2003 to > 90% in 2010 [21], but in most rural areas the average reimbursement rate for outpatient care under the New Rural Cooperative Health Scheme (NCMS) is only about 10% [22]. As secondary treatments were mostly prescribed in the outpatient clinic, their use is more likely to be affected by the price of the drugs and the reimbursement policy. Of the six proven drug treatment categories, statins were the most expensive, costing for example 2555 RMB (~£270) a year for daily treatment with 20 mg simvastatin between 2004 and 2008 [23], with little difference in price between generic and non-generic drugs, which may account for its extremely low use in the present study population during that period.

Self-rated health status has been recognised as a useful index for use of health services [24,25] and a predictor for future vascular events and mortality [25]. The present study is, to our knowledge, the first to report the association between self-rated health status and usage of long-term medication. Those who self-rated their health status as “poor” were nearly twice as likely to be on secondary prevention treatments compared with those with “good” health status, suggesting that feeling good about their health is an important determinant of non-medication or non-adherence to medication in individuals. It is not clear in the present study population whether the self-reported health status is correlated with the severity of the disease diagnosed.

The most important finding in the present study is, perhaps, that the treatment rate in secondary prevention is influenced strongly by the awareness of the individual risk factors rather than overall absolute risk. Many CVD patients even in the “so-called” normal range of distribution of blood pressure and cholesterol are at substantial absolute risk of developing further cardiovascular events. There is well-established randomised evidence that blood pressure [26] and lipid lowering treatments confer substantial benefit regardless of pre-treatment levels of blood pressure or blood cholesterol [27]. On the other hand, some drug classes that are widely used for blood pressure lowering treatment (such as β-blocker and ACE-I) have also been shown to be particularly effective for secondary prevention following IHD [6,7]. It is not clear whether the treatment pattern observed in this study reflects a lack of understanding by Chinese doctors about the effects of these treatments, or is driven mainly by reimbursement policies, or both.

One of the limitations of the present study is that it was not designed to be nationally representative, so the findings should be generalized with caution to the overall Chinese population. Moreover, the diagnosis of CVD and use of six proven drug categories were based on self-reported data without any objective validation. However, both the prevalent rates of self- reported IHD and stroke, as well as the treatment patterns, in the present study were comparable to those reported by the PURE-China study, in which 89% of the participants with self-reported IHD and/or stroke had their diagnoses confirmed by central adjudication [1]. There is also good evidence from many other studies in different populations that self-reported IHD and stroke have a high degree of specificity [28–32].

In summary this large community-based survey of 1737 rural and urban communities of China found that only 1 in 3 individuals with a history of CVD receive any established secondary preventive treatments. While lack of appropriate awareness of perceived risk among patients may contribute to substantial under-use of such therapy, several other factors could also play an important role, including inappropriate reimbursement policies (e.g., short period of reimbursement for statins following CVD) which should be addressed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Judith MacKay in Hong Kong; Yu Wang, Gonghuan Yang, Zhengfu Qiang, Lin Feng, Maigen Zhou, Wenhua Zhao, and Yan Zhang at the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); Lingzhi Kong, Xiucheng Yu, and Kun Li at the Ministry of Health of China; and Sarah Clark, Martin Radley, Hongchao Pan, Jill Boreham, Paul Sherliker, and Sarah Lewington at the Clinical Trial Service Unit, Oxford, for assisting with the design, planning, organization, conduct of the study, and data analysis. In particular we would like to thank Gary Whitlock for his advice in drafting the manuscript. We especially thank the participants in the study and the members of the survey teams in each of the 10 regional centres; the project development and management teams based at Beijing, Oxford; and the 10 regional centres. The Clinical Trial Service Unit and Epidemiological Studies Unit acknowledges support from the British Heart Foundation Centre of Research Excellence, Oxford.

Members of the CKB collaborative group are as follows:

Study Coordinating Centres

International Co-ordinating Centre, Oxford: Zhengming Chen, Garry Lancaster, Xiaoming Yang, Alex Williams, Margaret Smith, Ling Yang, Yumei Zhang, Iona Millwood, Yiping Chen, Qiuli Zhang, Sarah Lewington, Gary Whitlock

National Co-ordinating Centre, Beijing: Yu Guo, Guoqing Zhao, Zheng Bian, Can Hou, Yunlong Tan

Regional Co-ordinating Centres, 10 areas in China:

Qingdao

Qingdao Centre for Disease Control: Zengchang Pang, Shanpeng Li, Shaojie Wang

Licang Centre for Disease Control: Silu lv

Heilongjiang

Provincial Centre for Disease Control: Zhonghou Zhao, Shumei Liu, Zhigang Pang

Nangang Centre for Disease Control: Liqiu Yang, Hui He, Bo Yu

Hainan

Provincial Centre for Disease Control: Shanqing Wang, Hongmei Wang

Meilan Centre for Disease Control: Chunxing Chen, Xiangyang Zheng

Jiangsu

Provincial Centre for Disease Control: Xiaoshu Hu, Minghao Zhou, Ming Wu, Ran Tao,

Suzhou Centre for Disease Control: Yeyuan Wang, Yihe Hu, Liangcai Ma

Wuzhong Centre for Disease Control: Renxian Zhou

Guanxi

Provincial Centre for Disease Control: Zhenzhu Tang,Naying Chen, Ying Huang

Liuzhou Centre for Disease Control: Mingqiang Li, Zhigao Gan, Jinhuai Meng, Jingxin Qin

Sichuan

Provincial Centre for Disease Control: Xianping Wu, Ningmei Zhang

Pengzhou Centre for Disease Control: Guojin Luo, Xiangsan Que, Xiaofang Chen

Gansu

Provincial Centre for Disease Control: Pengfei Ge, Xiaolan Ren,Caixia Dong

Maiji Centre for Disease Control: Hui Zhang, Enke Mao, Zhongxiao Li

Henan

Provincial Centre for Disease Control: Gang Zhou, Shixian Feng

Huixian Centre for Disease Control: Yulian Gao,Tianyou He, Li Jiang, Huarong Sun

Zhejiang

Provincial Centre for Disease Control: Min Yu, Danting Su, Feng Lu

Tongxiang Centre for Disease Control: Yijian Qian, Kunxiang Shi,Yabin Han,Lingli Chen

Hunan

Provincial Centre for Disease Control: Guangchun Li, Huilin Liu, Yin Li

Liuyang Centre for Disease Control: Youping Xiong, Zhongwen Tan, Weifang Jia

Funding

The baseline survey and first re-survey in China were supported by a research grant from the Kadoorie Charitable Foundation in Hong Kong; follow-up of the project during 2009–14 is supported by the Wellcome Trust in the UK (grant 088158/Z/09/Z); and the National Key Technology Research and Development Program in the 12th Five-Year Plan, Ministry of Science and Technology, People's Republic of China (reference: 2011BAI09B01); the Clinical Trial Service Unit and Epidemiological Studies Unit (CTSU) at Oxford University also receives core funding for it from the UK Medical Research Council, the British Heart Foundation, and Cancer Research UK.

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Contributor Information

Yiping Chen, Email: yiping.chen@ctsu.ox.ac.uk.

Liming Li, Email: lmlee@vip.163.com.

References

- 1.Yusuf S., Islam S., Chow C.K. Use of secondary prevention drugs for cardiovascular disease in the community in high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries (the PURE Study): a prospective epidemiological survey. Lancet. 2011;9798(378):1231–1243. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61215-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Critchley J., Liu J., Zhao D., Wei W., Capewell S. Explaining the increase in coronary heart disease mortality in Beijing between 1984 and 1999. Circulation. 2004;110(10):1236–1244. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140668.91896.AE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Unal B., Critchley J.A., Capewell S. Explaining the decline in coronary heart disease mortality in England and Wales between 1981 and 2000. Circulation. 2004;109(9):1101–1107. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000118498.35499.B2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wijeysundera H.C., Machado M., Farahati F. Association of temporal trends in risk factors and treatment uptake with coronary heart disease mortality, 1994–2005. JAMA. 2010;303(18):1841–1847. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ford E.S., Ajani U.A., Croft J.B. Explaining the decrease in U.S. deaths from coronary disease, 1980–2000. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(23):2388–2398. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yusuf S., Peto R., Lewis J., Collins R., Sleight P. Beta blockade during and after myocardial infarction: an overview of the randomized trials. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1985;27(5):335–371. doi: 10.1016/s0033-0620(85)80003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dagenais G.R., Pogue J., Fox K., Simoons M.L., Yusuf S. Angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors in stable vascular disease without left ventricular systolic dysfunction or heart failure: a combined analysis of three trials. Lancet. 2006;368(9535):581–588. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baigent C., Blackwell L., Emberson J. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376(9753):1670–1681. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61350-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yusuf S., Sleight P., Pogue J., Bosch J., Davies R., Dagenais G. Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(3):145–153. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001203420301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Y.P., Jiang L.X., Zhang Q., Wei X., Li X., Smith M., Chen Z.M. Doctor-reported hospital management of acute coronary syndrome in China: a nationwide survey of 1029 hospitals in 30 provinces. World J Cardiovasc Dis. 2012;2:168–176. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Z., Lee L., Chen J. Cohort profile: the Kadoorie Study of Chronic Disease in China (KSCDC) Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34(6):1243–1249. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Z.M., Chen J., Collins R., Guo Y., Peto R., Wu F., Li L. China Kadoorie Biobank of 0.5 million people: survey methods, baseline characteristics and long-term follow-up. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(1):1652–1666. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plummer M. Improved estimates of floating absolute risk. Stat Med. 2004;23(1):93–104. doi: 10.1002/sim.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang L.X., Li X., Li J. A cross-sectional study on the use of statin among patients with atherosclerotic ischemic stroke in China. Chin Med J. 2010;31(8):925–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang L.X., Li X., Li J. A cross-sectional study on the use of statin among patients with atherosclerotic ischemic stroke in China. Chin J Epidemiol. 2010;31:925–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu J. Chinese guideline for secondary prevention of hyperlipidemia in adulthood. Chin J Cardiovasc Dis. 2007;35(4):295–304. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y. Chinese guideline for secondary prevention of ischemic stroke and TIA. Chin J Neurol. 2010;43(2):154–157. [Google Scholar]

- 18.HPS2-THRIVE Collaboration Group HPS2-THRIVE randomized placebo-controlled trial in 25 673 high-risk patients of ER niacin/laropiprant: trial design, pre-specified muscle and liver outcomes, and reasons for stopping study treatment. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(17):1279–1291. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hopewell J.O.A., Parish S., Haynes R. Environmental and genetic risk factors for statin-induced myopathy in Chinese participants from HPS2-THRIVE. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(Suppl. 1):339–653. [Google Scholar]

- 20.John R.M. Crowding out effect of tobacco expenditure and its implications on household resource allocation in India. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(6):1356–1367. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang S., Tao J., Bekedam H. Controlling cost escalation of healthcare: making universal health coverage sustainable in China. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(Suppl. 1):S8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-S1-S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barber S.L., Yao L. Development and status of health insurance systems in China. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2011;26(4):339–356. doi: 10.1002/hpm.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drug price 315 net. http://www.315jiage.cn/x-WeiFenLei/85346.htm [June 24 2013]

- 24.Gross R., Brammli-Greenberg S., Remennick L. Self-rated health status and health care utilization among immigrant and non-immigrant Israeli Jewish women. Women Health. 2001;34(3):53–69. doi: 10.1300/J013v34n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grool A.M., van der Graaf Y., Visseren F.L., de Borst G.J., Algra A., Geerlings M.I. Self-rated health status as a risk factor for future vascular events and mortality in patients with symptomatic and asymptomatic atherosclerotic disease: the SMART study. J Intern Med. 2012;272(3):277–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2012.02521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Randomised trial of a perindopril-based blood-pressure-lowering regimen among 6,105 individuals with previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack. Lancet. 2001;358(9287):1033–1041. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06178-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joshi R., Chow C.K., Raju P.K. Fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular disease and the use of therapies for secondary prevention in a rural region of India. Circulation. 2009;119(14):1950–1955. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.819201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bergmann M.M., Byers T., Freedman D.S., Mokdad A. Validity of self-reported diagnoses leading to hospitalization: a comparison of self-reports with hospital records in a prospective study of American adults. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147(10):969–977. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okura Y., Urban L.H., Mahoney D.W., Jacobsen S.J., Rodeheffer R.J. Agreement between self-report questionnaires and medical record data was substantial for diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction and stroke but not for heart failure. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(10):1096–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamagishi K., Ikeda A., Iso H., Inoue M., Tsugane S. Self-reported stroke and myocardial infarction had adequate sensitivity in a population-based prospective study JPHC (Japan Public Health Center)-based Prospective Study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(6):667–673. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lampe F.C., Walker M., Lennon L.T., Whincup P.H., Ebrahim S. Validity of a self-reported history of doctor-diagnosed angina. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52(1):73–81. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00146-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heckbert S.R., Kooperberg C., Safford M.M. Comparison of self-report, hospital discharge codes, and adjudication of cardiovascular events in the Women's Health Initiative. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(12):1152–1158. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]