Abstract

Importance

Racial disparities in receipt of minimally invasive surgery (MIS) persist in the United States and have been shown to also be associated with a number of driving factors, including insurance status. However, little is known as to how expanding insurance coverage across a population influences disparities in surgical care.

Objective

To evaluate the impact of Massachusetts health care reform on racial disparities in MIS.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A retrospective cohort study assessed the probability of undergoing MIS vs an open operation for nonwhite patients in Massachusetts compared with 6 control states. All discharges (n = 167 560) of nonelderly white, black, or Latino patients with government insurance (Medicaid or Commonwealth Care insurance) or no insurance who underwent a procedure for acute appendicitis or acute cholecystitis at inpatient hospitals between January 1, 2001, and December 31, 2009, were assessed. Data are from the Hospital Cost and Utilization Project State Inpatient Databases.

Intervention

The 2006 Massachusetts health care reform, which expanded insurance coverage for government-subsidized, self-pay, and uninsured individuals in Massachusetts.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Adjusted probability of undergoing MIS and difference-in-difference estimates.

Results

Prior to the 2006 reform, Massachusetts nonwhite patients had a 5.21–percentage point lower probability of MIS relative to white patients (P < .001). Nonwhite patients in control states had a 1.39–percentage point lower probability of MIS (P = .007). After reform, nonwhite patients in Massachusetts had a 3.71–percentage point increase in the probability of MIS relative to concurrent trends in control states (P = .01). After 2006, measured racial disparities in MIS resolved in Massachusetts, with nonwhite patients having equal probability of MIS relative to white patients (0.06 percentage point greater; P = .96). However, nonwhite patients in control states without health care reform have a persistently lower probability of MIS relative to white patients (3.19 percentage points lower; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

The 2006 Massachusetts insurance expansion was associated with an increased probability of nonwhite patients undergoing MIS and resolution of measured racial disparities in MIS.

Introduction

Laparoscopic surgery has become the standard of care for the treatment of acute cholecystitis and acute appendicitis, with fewer complications, shorter hospitalizations, and faster recovery times relative to open procedures.1–4 However, payer status and nonwhite race/ethnicity have both been shown to be associated with inferior utilization of laparoscopic surgery for both diagnoses relative to privately insured and white patients.5–7 These disparities span pediatric populations, Medicare beneficiaries, and patients within the Veterans Affairs health care system.8–11

The United States is unique among industrialized countries in that access to health care coverage is mediated in large part through employer-purchased insurance or individually purchased plans. While federal- and state-subsidized insurance plans such as Medicaid assist in access to coverage for low-income residents, income eligibility standards vary considerably between states. Lack of health insurance in the United States has become increasingly common during the past decade and has been the impetus for major health care reform at the federal and state levels. The 2009 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act aims to expand insurance coverage to more than 30 million uninsured people in the United States and is modeled in large part on the 2006 Massachusetts legislation. Both laws aimed to increase insurance coverage primarily for nonelderly adults who are ineligible for subsidized insurance programs, including state-subsidized insurance programs for children (State Children’s Health Insurance Program) or federally subsidized Medicare for individuals older than 65 years. While studies have documented benefits of gaining insurance on the management of medical conditions, little is known about how gaining insurance affects the delivery of surgical care. Specifically, sparse data exist on the effect of coverage expansion on disparities in surgical care by payer status or patient race.

The 2006 Massachusetts health care reform serves as a unique natural experiment to analyze the impact of expanded health insurance coverage on the delivery of surgical care for government-subsidized and uninsured patients. The legislation in Massachusetts expanded Medicaid coverage to those living below 150% of the federal poverty level, created a state-subsidized insurance program (Commonwealth Care) for individuals whose income is less than 300% of the federal poverty level but who remain ineligible for Medicaid, and established an individual mandate requiring the purchase of health insurance. As a result, Massachusetts saw a reduction in the number of uninsured residents from 548 000 in 2006 to 247 000 in 2009.12 The majority of newly insured residents enrolled in either Medicaid or Commonwealth Care (eFigure 1 in Supplement). Minority groups particularly benefited from expanded insurance coverage. In 2006, approximately 18% of black and Hispanic residents were uninsured compared with just 6.8% of white residents.13 By 2010, fewer than 5% of black residents and 10% of Hispanic residents were uninsured, while uninsurance rates in white patients decreased to around 3% (eFigure 2 in Supplement).14,15 Since reform, there has been an increase in the use of major inpatient procedures for lower-income residents and Hispanic patients.16 Yet, questions remain about how diminishing disparities in insurance coverage will affect variations in clinical care and specific surgical procedures.17

The primary objective of this study is to evaluate the impact of the Massachusetts health insurance expansion on the disparate receipt of minimally invasive surgery (MIS) for nonwhite patients who have government-subsidized insurance, are uninsured, or self-pay. We performed an analysis of administrative databases from Massachusetts and 6 control states. Our hypothesis is that expanded health insurance increases the utilization of MIS and decreases disparities in MIS for government-subsidized and uninsured nonwhite patients.

Methods

We used data from the Hospital Cost and Utilization Project State Inpatient Databases (SID) for Massachusetts and 6 control states (Maryland, New York, New Jersey, Arizona, Florida, and Washington). Control states were selected for their relative geographic proximity, similar rates of cholecystectomy and appendectomy, or similar insurance distribution among government-subsidized and uninsured residents.12,18 The SID capture an estimated 98% of all inpatient discharges annually within respective states. Our study period included all discharges from January 1, 2001, to December 31, 2009. Each patient record represents a unique hospital discharge and includes age, sex, race, primary payer, diagnoses, procedures, admission type (emergent, urgent, or elective), and hospital type (urban vs rural, private vs not for profit, and total hospital beds). The study was exempt from institutional review board review and informed consent as it involved existing, publicly available data recorded in a manner in which subjects cannot be identified directly or indirectly.

The study population included all white, black, or Hispanic patients aged 18 to 64 years who were discharged with an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision diagnosis code for acute cholecystitis (574.00, 574.01, 574.30, 574.31, 574.60, 574.61, 574.80, 574.81, 575.0, or 575.12) or acute appendicitis (540.0, 540.1, 540.9, 541, or 542). International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision procedure codes were used to determine whether patients underwent a laparoscopic cholecystectomy (512.3 or 512.4), laparoscopic appendectomy (470.1 or 470.9 with an associated general laparoscopy code of 542.1), open cholecystectomy (512.1 or 512.2), or open appendectomy (470.9). Only patients with both appropriate diagnosis and procedure codes were included in the final analysis. Patients with Medicare were excluded given that their insurance status was unlikely to have been affected by the health care reform legislation. Patients were also excluded if they were discharged in the second or third quarter of 2006, the periods of considerable variation around enactment of the Massachusetts reform.

Indicator variables were created for white vs nonwhite (black or Hispanic) race/ethnicity and for Massachusetts vs control states. An additional variable was created to discern discharges before and after the 2006 Massachusetts health care reform (prereform being defined as before the second quarter of 2006 and postreform being defined as after the third quarter of 2006). Diagnosis codes were used to calculate the Elixhauser comorbidity index, which was used for risk assessment and risk adjustment consistent with previously described methods.19 An additional categorical variable was created for patients with complicated disease. Acute cholecystitis was defined as complicated if carrying an associated diagnosis of perforation of gallbladder, cholangitis, perforation or fistula of the bile duct, septic shock, sepsis, or severe sepsis. Acute appendicitis was defined as complicated if associated diagnoses included peritoneal or retroperitoneal abscess, perforation of intestine, sepsis, or septic shock.

We used ordinary least squares regression models to predict the probability of undergoing MIS, adjusting for patient factors including age, sex, admission type, Elixhauser comorbidity index, and complex disease presentation. Rather than probit or logit models, we elected to use ordinary least squares regression to minimize additional transformation of both dependent and independent variables while also providing a more accurate measurement of population means. The subsequent model output represents absolute differences in the probability of undergoing MIS. Analogous risk-adjusted difference-in-difference estimates were then used to assess for changes in racial disparities with the probability of undergoing MIS as the dependent variable and patient race/ethnicity as the primary independent variable. Difference-in-difference models were developed based on previously described models.20 Sensitivity analyses were performed to evaluate for any differences in preintervention trends in the probability of undergoing MIS for white and nonwhite patients within and between intervention groups.

Disparities by patient race/ethnicity are reported as the percentage point difference in probabilities of undergoing laparoscopic surgery between nonwhite and white patients. We looked specifically at government-subsidized, uninsured nonwhite patients relative to government-subsidized, uninsured white patients, as this was the subgroup most directly affected by the insurance expansion.

Secondary analyses of cost of care were determined using the available charge variable capturing total charges billed to the patient and the Hospital Cost and Utilization Project cost to charge ratio. The cost to charge ratio was developed to better assess total costs as opposed to charges, which can vary considerably by primary payer, hospital purchasing and market power, and hospital location. Cost data are calculated using hospital accounting reports collected by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Data were analyzed using Stata version 12 statistical software (StataCorp LP). All results are reported with 95% confidence intervals or P values as appropriate. The threshold for significance was 2-tailed P < .05.

Results

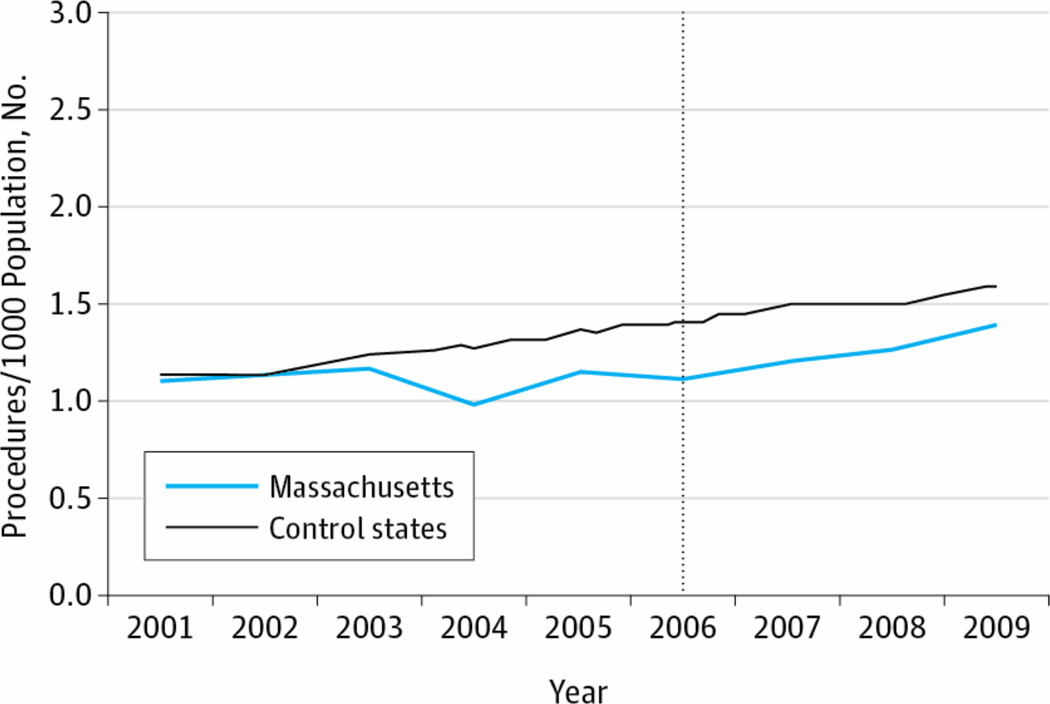

Between January 1, 2001, and December 31, 2009, we identified 167 560 nonelderly adults who underwent an inpatient procedure for acute cholecystitis or acute appendicitis in addition to meeting inclusion criteria (Table 1). Massachusetts had a lower percentage of nonwhite patients and emergent admissions. Patient age, sex, comorbidity indices, and rates of complicated presentation were comparable between Massachusetts and control states. There was no differential change in the rates of surgical procedures for appendicitis and cholecystitis in Massachusetts vs control states during the study period (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Massachusetts N (%) |

Control N (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Total Patients | 10,917 | 156,642 |

| Age mean (std) | 34.5 (12.3) | 34.5 (12.2) |

| Female | 5,907 (54.1) | 86,780 (55.4) |

| Race | ||

| White | 6,519 (59.7) | 68,101 (43.5) |

| Minority | 4,398 (40.3) | 88,542 (56.5) |

| Elixhauser Comorbidity Index mean (std) | 0.63 (1.1) | 0.62 (1.1) |

| Appendectomy | 6,939 (63.6) | 89,742 (57.3) |

| Cholecystectomy | 3,983 (36.5) | 67,002 (42.8) |

| Hospital Type | ||

| NFP, Rural 100+ beds | 178 (1.6) | 2,723 (3.6) |

| NFP, Urban <100 beds | 724 (6.6) | 1,138 (1.5) |

| NFP, Urban 100–299 beds | 4,499 (41.2) | 23,697 (31.7) |

| NFP, Urban 300+ beds | 4,840 (44.3) | 45,857 (61.2) |

| Admission Type | ||

| Emergent | 8,176 (74.9) | 140,438 (89.68) |

| Urgent | 2,519 (23.1) | 10,930 (6.98) |

| Elective | 2220 (2.0) | 5,100 (3.26) |

| Complicated Presentation | 568 (5.2) | 9,184 (5.9) |

Trend in Inpatient Appendectomy and Cholecystectomy for Uninsured and Government-Subsidized Patients The rate of procedures indicates the number of procedures captured divided by the total population with no insurance, Medicaid, or Commonwealth Care insurance coverage (in Massachusetts). The vertical dashed line indicates the 2006 Massachusetts health care reform.

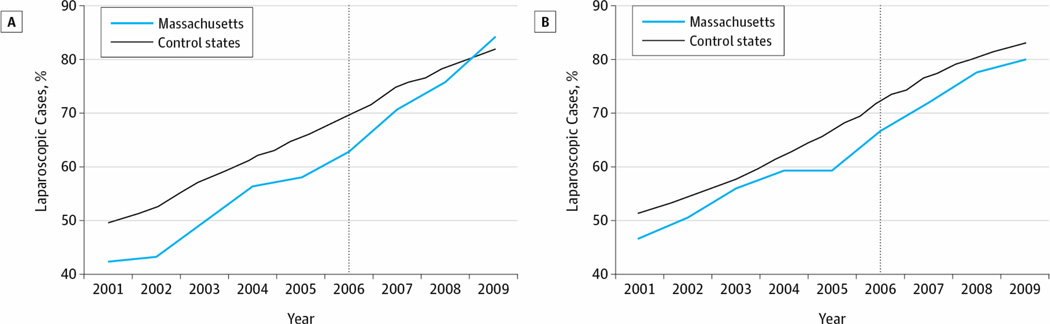

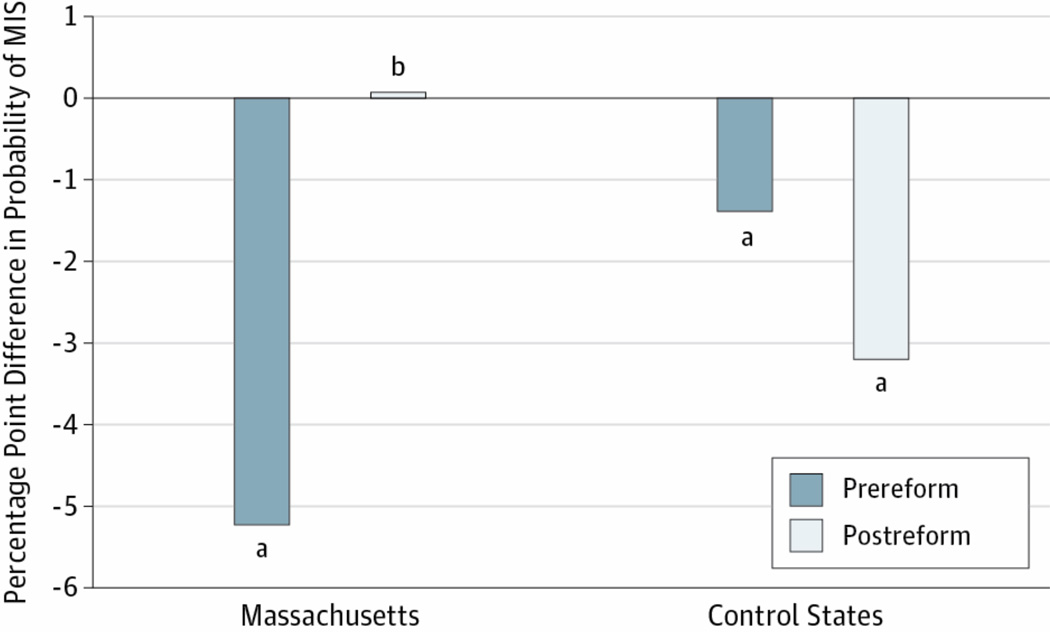

The percentage of patients undergoing laparoscopic procedures increased markedly in both Massachusetts and control states (Figure 2). Prior to reform, nonwhite patients had a 5.21–percentage point lower probability of MIS relative to white patients in Massachusetts (P < .001) (Figure 3). Within control states, nonwhite patients had a 1.39–percentage point lower probability of undergoing laparoscopic surgery compared with white patients (P = .007). After insurance expansion in Massachusetts, nonwhite patients had a 0.06–percentage point greater probability of MIS relative to white patients (P = .96). However, in control states, nonwhite patients had a 3.19–percentage point lower probability of MIS compared with white patients (P < .001). Therefore, the measured racial disparity in MIS disappeared in Massachusetts after health care reform while persisting in control states.

Trends in Minimally Invasive Surgery A, Nonwhite patients. B, White patients. The vertical dashed lines indicate the 2006 Massachusetts health care reform.

Effect of Nonwhite Race/Ethnicity on the Probability of Undergoing Minimally Invasive Surgery. The percentage point difference in the probability of undergoing minimally invasive surgery (MIS) is between government-subsidized and self-pay nonwhite patients and government-subsidized and self-pay white patients, controlling for age, sex, comorbidities, hospital type, admission type, and complicated presentation. aP < .05. bP = .96.

Difference-in-difference analysis is another statistical way to analyze this issue, comparing the change in probability of undergoing MIS in Massachusetts with the change in control states. Difference-in-difference analyses show that the policy was associated with a 3.71–percentage point increase in MIS for nonwhite patients in Massachusetts compared with concurrent trends for nonwhite patients in control states (P = .01) (Table 2). Within Massachusetts, nonwhite patients had a 4.63–percentage point increase in MIS relative to white patients (P = .01) (Table 2). Complete difference-in-difference model output is shown in eTables 1 through 4 in the Supplement. There was no differential change in the probability of privately insured patients in Massachusetts undergoing MIS after reform relative to privately insured patients in control states (data not shown). Sensitivity analyses revealed no differential trends in the probability of laparoscopic surgery prior to reform in comparing nonwhite patients in Massachusetts vs control states (P = .55), white patients in Massachusetts vs control states (P = .33), nonwhite vs white patients in Massachusetts (P = .11), and nonwhite vs white patients in control states (P = .85).

Table 2.

Change in percentage of patients receiving laparoscopic surgery before and after 2006 health reform.

| Massachusetts (% Cases Laparoscopic) |

Control (% Cases Laparoscopic) |

Difference-in-Difference (% Cases Laparoscopic) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Diff | Pre | Post | Diff | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||

| Mass-M* vs Cont-M† | 50.94 | 76.97 | +26.03 | 58.60 | 78.23 | +19.63 | +6.4 | +3.71 (P=0.013) | |

| Massachusetts Minority (% Cases Laparoscopic) |

Massachusetts-White (% Cases Laparoscopic) |

||||||||

| Pre | Post | Diff | Pre | Post | Diff | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||

| Mass-M* vs Mass-W‡ | 50.94 | 76.97 | +26.03 | 55.21 | 76.61 | +21.4 | +4.63 | +4.63 (P=0.011) | |

Minority patients in Massachusetts

Minority patients in control states

White patients in Massachusetts

Overall cost for hospitalization was markedly lower for patients undergoing MIS compared with open surgery. Controlling for confounding factors including complicated presentation and secular trends, MIS was associated with a cost $1551.34 lower than that for open procedures (P < .001). Within Massachusetts, MIS was associated with costs $2744.77 lower than open procedures before health care reform and $1893.52 lower than open procedures after health care reform (both P < .001).

Discussion

Laparoscopic surgery has become the standard management for both acute appendicitis and acute cholecystitis. However, disparities in undergoing MIS persist by both payer status and patient race/ethnicity. The Massachusetts experience provides a unique quasi-experimental model to evaluate the impact of insurance expansion on surgical care delivery and to determine possible ramifications of the federal health care reform to be phased into effect in the coming years. To our knowledge, this study is the first to date examining changes in MIS after the 2006 Massachusetts health care reform.

These data highlight the rapid expansion of laparoscopic surgery in both Massachusetts and control states, possibly due to increased physician comfort for the techniques, shorter hospitalizations for patients, and comparable clinical outcomes. However, our data show that after health care reform in Massachusetts, racial/ethnic disparities in the probability of undergoing MIS disappeared in Massachusetts, while variation by patient race/ethnicity persisted in other states. Specifically, the probability of undergoing laparoscopic surgery increased by 3.71 percentage points for government-subsidized, uninsured nonwhite patients in Massachusetts relative to concurrent changes in control states. Within Massachusetts, nonwhite patients had a 4.61–percentage point increase in laparoscopic procedures relative to white patients.

Since the Institute of Medicine’s 2002 landmark publication Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care21 was released, disparities in health care have come under increasing scrutiny. Evaluation of such disparities has proven to be challenging given the multitude of factors connected with patient race/ethnicity, including variations in health beliefs and behavior, inequitable access to health care, and systemic, institutional, or health care provider biases against minority and uninsured populations. Our findings could therefore be attributed to a number of possible explanations.

One reason for the increase in laparoscopic procedures is that after health care reform, nonwhite patients may present earlier, before they develop complicated disease, which might not make them candidates for a laparoscopic approach. Newly insured patients report improved access to primary care providers, increased utilization of preventive care, better management of chronic comorbid conditions, and less utilization of emergency departments.22–26 Recent studies suggest that since the 2006 reform, government-subsidized and self-pay patients are also more likely to be referred for surgical procedures.16 As previously uninsured patients—disproportionately minority patients—gain access to health care systems, patient populations could become increasingly homogeneous in terms of overall health status, operative suitability, or severity of condition at presentation. While we attempted to control for comorbidities, admission type, and complicated disease, our findings could represent decreases in the variability of the presentation or health status of nonwhite patients at the time of initial hospital presentation. Such an effect on patient presentation would nonetheless provide optimistic evidence for narrowing disparities in MIS by patient race/ethnicity.

Alternatively, differential changes in health beliefs and health care–seeking behavior for nonwhite patients in Massachusetts could have disproportionately increased demand for MIS by nonwhite patients during the study period. However, such a statistically significant shift is unlikely to have occurred in such a short period. Institutional or health care provider bias against nonwhite patients could also have differentially changed after 2006. However, the Massachusetts reform acted almost exclusively through insurance expansion to low-income residents with limited provisions altering other aspects of health care delivery. Our findings therefore point away from health care provider or hospital-level discrimination as a primary driver of racial/ethnic disparities in the management of acute cholecystitis and acute appendicitis, conversely suggesting that expanding insurance coverage may decrease variation in health care delivery.

Hospitals and health care providers caring for the majority of nonwhite patients may now feel more comfortable with laparoscopic approaches or may now be identifying the merits of a laparoscopic approach. Minority and low-income patients have been shown to disproportionately receive health care within certain clusters of hospitals, namely large urban or safety-net hospitals. Previous studies have shown that newly insured patients in Massachusetts preferentially maintain care at large urban or safety-net hospitals.27 It is therefore possible that differential changes in practice patterns within these Massachusetts hospitals account for the closing disparities in MIS rates. However, our analysis did control for hospital type and also suggested that there were no significant changes in the volume of cholecystectomies or appendectomies performed at safety-net hospitals.

As a retrospective study of administrative data, our study has a number of limitations that must be considered. First, we used a nonrandom sample as our control group by selecting only 6 states outside Massachusetts. These control states may not truly represent the counterfactual against which our policy effect is derived. Even if our findings hold true in Massachusetts, health care system dynamics vary significantly by state and country. Additional factors outside of insurance coverage could play a more prominent role in health disparities elsewhere in the country, limiting the effectiveness of insurance expansion alone on racial/ethnic disparities within other respective states. Data from the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care and the US Census Bureau suggest similar rates of surgical procedures and similar insurance distribution among low-income residents between Massachusetts and control states.28 Furthermore, the economic recession of 2008 overlapped our study period and affected individual states to varying degrees. However, data available through the US Bureau of Labor Statistics suggest similar trends in unemployment between Massachusetts and our 6 control states (eFigure 3 in Supplement).29 While studies have highlighted the decreased disparities in acute appendicitis outcomes in Canada (with universal insurance coverage), the absence of international controls also limits the generalizability of our findings outside the United States.30

Selection bias cannot be fully discounted. However, the Hospital Cost and Utilization Project SID capture approximately 97% of all discharges annually across respective states, greatly minimizing such bias. Coding errors including inaccurate capture of procedure received and overlap between procedure codes could have potentially introduced uncontrolled bias, although they are unlikely to do so in a directional fashion.

Our data reinforce previous studies showing that MIS is associated with lower overall cost of hospitalization, primarily through decreased length of stay. Comparison of costs in Massachusetts relative to our control states is challenging in this data set given the strikingly different market power of hospitals in Massachusetts. However, our data provide no clear evidence that the increased utilization of MIS in Massachusetts was associated with changes in overall cost of care for patients admitted with acute cholecystitis or acute appendicitis. Additional analyses with more economically robust models are needed to comprehensively evaluate trends in cost before and after the 2006 health care reform.

Our results reveal disparities in MIS by patient race/ethnicity prior to the 2006 health insurance expansion in both Massachusetts and control states. After the expansion, however, the probability of government-subsidized or uninsured nonwhite patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery increased significantly more in Massachusetts relative to concurrent trends in control states. Furthermore, racial/ethnic disparities in laparoscopic surgery resolved in Massachusetts after health care reform, while such variation persisted elsewhere in the country. Additional studies are needed to more comprehensively dissect the multifactorial drivers of disparities in surgical care and the generalizability of the Massachusetts experience elsewhere in the country. However, our findings provide optimistic evidence for decreased variation in MIS by patient race/ethnicity after expansion of health insurance coverage in Massachusetts.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Lujan JA, Parrilla P, Robles R, Marin P, Torralba JA, Garcia-Ayllon J. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy vs open cholecystectomy in the treatment of acute cholecystitis: a prospective study. Arch Surg. 1998;133(2):173–175. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.133.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Golub R, Siddiqui F, Pohl D. Laparoscopic vs open appendectomy: a metaanalysis. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;186(5):545–553. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(98)00080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wei B, Qi CL, Chen TF, et al. Laparoscopic vs open appendectomy for acute appendicitis: a metaanalysis. Surg Endosc. 2011;25(4):1199–1208. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1344-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rattner DW, Ferguson C, Warshaw AL. Factors associated with successful laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Ann Surg. 1993;217(3):233–236. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199303000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenstein AJ, Moskowitz A, Gelijns AC, Egorova NN. Payer status and treatment paradigm for acute cholecystitis. Arch Surg. 2012;147(5):453–458. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varela JE, Nguyen NT. Disparities in access to basic laparoscopic surgery at US academic medical centers. Surg Endosc. 2011;25(4):1209–1214. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1345-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guller U, Jain N, Curtis LH, Oertli D, Heberer M, Pietrobon R. Insurance status and race represent independent predictors of undergoing laparoscopic surgery for appendicitis: secondary data analysis of 145,546 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199(4):567–577. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hagendorf BA, Liao JG, Price MR, Burd RS. Evaluation of race and insurance status as predictors of undergoing laparoscopic appendectomy in children. Ann Surg. 2007;245(1):118–125. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000242715.66878.f8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kokoska ER, Bird TM, Robbins JM, Smith SD, Corsi JM, Campbell BT. Racial disparities in the management of pediatric appenciditis. J Surg Res. 2007;137(1):83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jha AK, Fisher ES, Li Z, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. Racial trends in the use of major procedures among the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(7):683–691. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa050672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arozullah AM, Ferreira MR, Bennett RL, et al. Racial variation in the use of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the Department of Veterans Affairs medical system. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;188(6):604–622. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(99)00047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaiser Family Foundation. [Accessed May 13, 2012];State health facts. http://kff.org/statedata/.

- 13.Massachusetts Division of Health Care Finance and Policy. [Accessed May 13, 2012];Massachusetts household survey on health insurance status. 2007 http://archives.lib.state.ma.us/bitstream/handle/2452/58018/ocn690284055.pdf?sequence=1.

- 14.Massachusetts Division of Health Care Finance and Policy. [Accessed May 13, 2012];Health insurance coverage in Massachusetts: results from the 2008–2010 Massachusetts Health Insurance Surveys. http://www.mass.gov/chia/docs/r/pubs/10/mhis-report-12-2010.pdf.

- 15.Long SK, Stockley K. [Accessed May 13, 2012];Health reform in Massachusetts: an update as of fall. 2009 http://bluecrossmafoundation.org/sites/default/files/MHRS%20Report%20Aug24.pdf.

- 16.Hanchate AD, Lasser KE, Kapoor A, et al. Massachusetts reform and disparities in inpatient care utilization. Med Care. 2012;50(7):569–577. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31824e319f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu J, Brawarsky P, Lipsitz S, Huskamp H, Haas JS. Massachusetts health reform and disparities in coverage, access and health status. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(12):1356–1362. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1482-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice. [Accessed October 11, 2012];Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/.

- 19.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wooldridge JM. Econometric Analysis of Cross-section and Panel Data. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. In: Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Unequal, editor. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Long SK, Masi PB. Access and affordability: an update on health reform in Massachusetts, fall 2008. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(4):w578–w587. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.w578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finkelstein A, Taubman S, Wright B, et al. Oregon Health Study Group. The Oregon Health Insurance Experiment: Evidence From the First Year. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2011. NBER working paper 17190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolstad JT, Kowalski AE The Impact of Health. Care Reform on Hospital and Preventive Care: Evidence From Massachusetts. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2010. NBER working paper 16012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pande AH, Ross-Degnan D, Zaslavsky AM, Salomon JA. Effects of health care reforms on coverage, access, and disparities: quasi-experimental analysis of evidence from Massachusetts. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smulowitz PB, Lipton R, Wharam JF, et al. Emergency department utilization after the implementation of Massachusetts health reform. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58(3):225–234. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ku L, Jones E, Shin P, Byrne FR, Long SK. Safety-net providers after health care reform: lessons from Massachusetts. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(15):1379–1384. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.US Census Bureau. [Accessed January 11, 2013];Health insurance historical tables. http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/hlthins/data/historical/HIB_tables.html.

- 29.US Bureau of Labor Statistics. [Accessed February 1, 2013];Local area unemployment statistics. http://www.bls.gov/lau/#tables.

- 30.Krajewski SA, Hameed SM, Smink DS, Rogers SO., Jr Access to emergency operative care: a comparative study between the Canadian and American health care systems. Surgery. 2009;146(2):300–307. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.