Abstract

Background: Minority race and lower socioeconomic status are associated with poorer patient ratings of health care quality and provider communication.

Objective: To examine the association of race/ethnicity or socioeconomic status with patients' and families' ratings of end-of-life care and communication about end-of-life care provided by physicians-in-training.

Methods: As a component of a randomized trial evaluating a program designed to improve clinician communication about end-of-life care, patients and patients' families completed preintervention survey data regarding care and communication provided by internal medicine residents and medical subspecialty fellows. We examined associations between patient and family race or socioeconomic status and ratings they gave trainees on two questionnaires: the Quality of End-of-Life Care (QEOLC) and Quality of Communication (QOC).

Results: Patients from racial/ethnic minority groups, patients with lower income, and patients with lower educational attainment gave trainees higher ratings on the end-of-life care subscale of the QOC (QOCeol). In path models, patient educational attainment and income had a direct effect on outcomes, while race/ethnicity did not. Lower family educational attainment was also associated with higher trainee ratings on the QOCeol, while family non-white race was associated with lower trainee ratings on the QEOLC and general subscale of the QOC.

Conclusions: Patient race is associated with perceptions of the quality of communication about end-of-life care provided by physicians-in-training, but the association was opposite to our hypothesis and appears to be mediated by socioeconomic status. Family member predictors of these perceptions differ from those observed for patients. Further investigation of these associations may guide interventions to improve care delivered to patients and families.

Introduction

The perception of racial discrimination in health care settings has been associated with lower patient ratings of health care quality1–3 as well as lower ratings of provider communication.4,5 Socioeconomic status has also been associated with disparities in physician–patient communication and may mediate associations by race and ethnicity.6,7 While disparities have been identified within a broader health care context, limited data are available to describe the relationship between patient and family member race or socioeconomic status and ratings of end-of-life care and communication. The distinction between “race” and racial disparities is important, as the assessment of differences by race may not necessarily capture important characteristics that influence variation in care related to both discrimination and perceived discrimination. However, the examination of associations between race or socioeconomic status and ratings of end-of-life care and communication may provide valuable information about factors that influence patient and family perceptions of quality. Quality communication is an essential component of excellent end-of-life care,8 and efforts to enhance training in this area will require an increased understanding of influential factors that may help guide and refine outcome measures and support interventions to improve end-of-life care and communication.

As a component of a 5-year, randomized trial evaluating a training program designed to improve clinician communication skills, preintervention survey data were collected from patients and patients' families. In this observational analysis, we investigated associations between patient and family race/ethnicity or socioeconomic status and the ratings they provided for trainees on the validated Quality of End-of-Life Care (QEOLC) and the Quality of Communication (QOC) questionnaires.9–11 We hypothesized that patient and family non-white race and lower socioeconomic status would be associated with decreased ratings of end-of-life care and communication.

Materials and Methods

Study design

Data for this study were drawn from preintervention surveys completed by patients and patients' families during the Improving Clinician Communication Skills (ICCS) trial, a 5-year randomized trial evaluating a training program designed to improve communication about end-of-life care provided by internal medicine residents, subspecialty fellows, and nurse practitioner students. The trial was conducted at the University of Washington and the Medical University of South Carolina. All procedures were approved by Institutional Review Boards at each institution.

Participants and setting

Trainees

The sample for the present study was restricted to the internal medicine residents (n=232) and subspecialty fellows (n=25) who participated in the ICCS trial and for whom we had data by August 16, 2012, the time at which data for these analyses were compiled. Residents ranging from postgraduate year 1–5 and fellows from geriatrics, nephrology, oncology, palliative medicine, and pulmonary and critical care medicine were invited to participate. Three recruitment attempts were completed for nonrespondents including mail, phone, and e-mail reminders.

Patients

Eligible participants were identified by examining medical records of individuals receiving care from enrolled trainees. Patient–trainee encounters included those occurring in both inpatient and outpatient settings, either during primary care clinics, subspecialty clinics, or during admission to inpatient services. Patient eligibility criteria for the ICCS trial sought to identify a variety of patients for whom end-of-life care discussions would be appropriate, including patients with advanced life-limiting disease, numerous chronic comorbidities, or critical illness; complete criteria are outlined in Appendix A. Patients were provided with a photograph of the trainee to ensure that they recognized the trainee with whom they had a clinical encounter and were able to provide an evaluation of his or her communication skills. Mail and in-person procedures were used to obtain patient participation, with three recruitment attempts for nonrespondents.

Family members

Three different recruitment strategies were utilized to identify family members for participation: (1) referral from participating patients who provided names of family members involved in their medical care; (2) identification of family members of noncommunicative but otherwise eligible inpatients; and (3) screening of the medical record to identify family members of deceased patients. Family members were provided with a photograph of the appropriate trainee and asked to acknowledge recognition of the individual and an ability to provide an evaluation of his or her communication skills. Nonrespondent family members were contacted up to three times, including in-person and mailed approaches.

Data collection and variables

For the ICCS study, survey data were collected from patients for whom the trainee had provided care and from those patients' families. Patients and family members could be asked to evaluate up to two trainees with whom they had documented clinical encounters. Data for the present study included evaluations provided by patients (n=695) and families (n=345) receiving care from a trainee during his/her preintervention period. Survey completion dates span 4.5 years, from October 2007 through April 2012.

Outcome Variables

Three outcome variables were selected from self-reported patient and family surveys: (1) the total score from the validated QEOLC questionnaire; (2) the general communication score from the QOC questionnaire (QOCgen); and (3) the end-of-life care communication score from the QOC questionnaire (QOCeol; Appendix B). Two additional outcomes variables included: the number of QOCeol items patients and family members felt that a trainee did not perform and the average ratings for only the items noted to have occurred.

The QEOLC score is made up of ten items, appropriate for both patients and families, measuring five domains of physician skills in end-of-life care: communication, symptom management, affective skills, patient-centered values, and patient-centered systems.11 QEOLC scale values could range from 0 (poorest possible quality of end-of-life care) to 10 (best possible end-of-life care). This instrument has acceptable internal consistency and construct validity was suggested through correlation with conceptually related measures: physician knowledge of palliative care; patient and family satisfaction with care; and nurse ratings of physician's care.11

The QOC questionnaire includes two component scores, a general communication scale (QOCgen) with six items and an end-of-life care communication scale (QOCeol) with seven items for patients and six items for family members.9 Previous studies support the construction of two scales based upon good factor convergence and discrimination, percent of variance explained, and reliability of component scores.9 The two QOC scales could range from 0 (poorest possible quality of communication) to 10 (best possible quality of communication). For the QOC, participants were offered two additional response options: the “doctor did not do this” and “don't know.” The answer “my doctor did not do this” was replaced by a score of 0. A respondent answer of “don't know” implied that the item was performed but unable to be rated. Thus, items reported as “don't know” were counted as having occurred and were replaced with the median domain score of the valid items for that respondent. This instrument has acceptable internal consistency and its construct validity was supported through correlations with the following conceptually-related measures: number of discussions with the clinician about end-of-life care; the extent to which the clinician knows the patient's treatment preferences; and single-item rating of the overall quality of communication.9

Predictor variables

Predictor variables for this study included patient or family race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. On their surveys, patients and family members self-identified as either non-Hispanic or Hispanic and as members of one or more of the following racial groups: white, African American, Asian, Pacific Islander, Native American, or other. For purposes of analysis, we computed three mutually exclusive racial/ethnic categories: (1) African American (including mixed); (2) other minority (including all respondents who did not endorse African American, but who endorsed Hispanic or at least one of the following minority races: Asian, Pacific Islander, Native American, or other); and (3) non-Hispanic white. For patients who did not respond to the race/ethnicity questions on their surveys, we substituted parallel information from the medical record. Socioeconomic status, obtained exclusively from surveys, was estimated by two ordinal variables: education level for patient and families, and for patients only, average monthly household income from all sources before taxes. There were six education levels, ranging from eighth grade or less to graduate or professional school, and seven income levels, ranging from less than $500 per month to greater than $4000 per month.

Potential confounders

We also investigated several patient, family, and trainee characteristics as potential confounders of the predictors of interest. Patients' self-rated health status came from their responses to the single-item SF1 general health status question (self-rated health, first question of the SF-12™ questionnaire [QualityMetric, Lincoln, RI]), which was included on the patient survey. The medical record provided information on patient age, gender, site of care (inpatient versus outpatient) and select patient disease states, including: advanced malignancy, advanced lung disease (advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and restrictive lung disease), congestive heart failure, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and end-stage liver disease (Appendix A). These disease states were chosen to evaluate as potential confounders based upon existing literature that suggests a potential impact of these illnesses on end-of-life care and quality of communication about end-of-life care.12,13 Family surveys contributed data on the family member's age and gender. Trainee variables obtained from self-report included the trainee's age, gender, and race; we also obtained data from program offices for postgraduate year and training site (University of Washington or Medical University of South Carolina).

Data analysis

The primary analyses for this study utilized regression models, based on cross-classified hierarchical analysis. Cross-classified analysis allowed the simultaneous use of evaluations from multiple respondents for a given trainee and the use of evaluations for multiple trainees from a given respondent. We conducted separate analyses of outcomes derived from patient surveys and those derived from family-member surveys.

For each outcome, we first built unadjusted regression models that involved a single predictor (or in the case of race, two dummy predictors) and the outcome. Then for each outcome we separately tested each of the potential confounders for its effect on the primary predictor's coefficient when compared with the coefficient from the unadjusted model. If addition of the new variable to the single-predictor model changed the coefficient of the predictor of interest by more than 20%, the new variable was defined as a confounder and used as a covariate in a final adjusted model. Because we defined the socioeconomic status variables (i.e., patient and family education, patient income) as potential mediators of the associations between race and our outcomes, we did not adjust for those variables in final models of associations between the outcomes of interest and race. In all tests of the significance of race, we used a likelihood ratio test, comparing the deviance of a model that included the two dummy indicators for race as predictors with that of a model that omitted the race indicators. To enhance our understanding of mediated models for the QOCeol, we evaluated two hypothesized path models linking the predictors and mediators of interest to one another and the following outcomes: the total score on the QOCeol (with zero imputed for items rated as “doctor did not do”) and the number of items not performed for the QOCeol.

In an effort to evaluate the effects of cross-classified nesting, we also performed pure two-level models based on a reduced sample that retained only one evaluation per respondent. Because these models produced results similar to those based on the cross-classified nesting, and because the cross-classified analysis made more complete use of our data, we report only the cross-classified analyses.

Regression analyses were produced with HLM for Windows, Version 7.0 (Scientific Software International, Skokie, IL) using full maximum likelihood estimation for continuous outcomes and penalized quasi-likelihood for discrete (count) outcomes. Path models were constructed with a combination of HLM, for the effects on the outcome of interest, Mplus Version 7 (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA) for effects on mediators, and SPSS Statistics Release 19.0.0 (IBM, Somers, NY) for associations among correlated exogenous variables. IBM SPSS was also used to construct descriptive tables. Statistical significance for all hypothesis tests was set at p<0.05.

Results

Preintervention survey data were available for 257 trainees (residents, n=232; subspecialty fellows, n=25). One hundred sixty-one trainees (63%) were located at the University of Washington with the remainder at the Medical University of South Carolina. Seventy-seven percent (n=197) were non-Hispanic white, and 51% (n=130) were female. Mean trainee age was 29.7 (standard deviation [SD] 4.7) years and 62% (n=158) were in their first postgraduate year (Table 1). Two hundred thirty-eight trainees received a median of 3 patient evaluations per trainee, and 176 received a median of 2 family member evaluations per trainee.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Physician Trainees

| Total | Evaluated by patients | Evaluated by family members | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of trainees | 257 | 238 | 176 |

| Number of evaluations per trainee, median (range) | 3 (1–10) | 2 (1–6) | |

| University of Washington, n (%) | 161 (62.6) | 146 (61.3) | 99 (56.3) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| African American | 9 (3.5) | 8 (3.4) | 8 (4.5) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 197 (76.7) | 182 (76.5) | 141 (80.1) |

| Other minority | 51 (19.8) | 48 (20.2) | 27 (15.3) |

| Female, n (%) | 130 (50.6) | 120 (50.4) | 88 (50.0) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 29.7 (4.7) | 29.6 (4.4) | 29.7 (5.2) |

| Postgraduate year n (%) | |||

| 1 | 158 (61.5) | 144 (60.5) | 110 (62.5) |

| 2 | 37 (14.4) | 36 (15.1) | 24 (13.6) |

| 3 | 31 (12.1) | 31 (13.0) | 24 (13.6) |

| 4 | 13 (5.1) | 9 (3.8) | 10 (5.7) |

| 5 | 8 (3.1) | 8 (3.4) | 3 (1.7) |

| 6 | 9 (3.5) | 9 (3.8) | 5 (2.8) |

| 8 | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) |

SD, standard deviation.

Surveys were collected from 1040 unique evaluators, of whom 695 (67%) were patients and 345 (33%) were family members. Sixty-six percent of patients were non-Hispanic white, and 24% were African American with similar proportions for family members. Education level ranged from eighth grade or less to graduate or professional degree, with a majority of patient and family members within the categories of high school diploma or equivalent and some college or trade school. For patients, average pre-tax monthly income was reported across the full range, with 21% of patients reporting an income above $4000 and 5% reporting an income of $500 or less. Of the patients completing surveys, 50% had one of the diagnoses evaluated for confounding. Those who did not have one of these conditions met one or more of the following inclusion criteria: a Charlson comorbidity score of 5 or higher (79%), inpatient status with age more than 80 years (21%), documentation of end-of-life communication or physician's ordes for life-sustaining treatment/do-not-resuscitate order (POLST/DNR) completion (13%), an intensive care unit stay of 3 days or more (6%), or enrollment in hospice or evaluation by palliative care (3%).

Up to two surveys were allowed per respondent, thus the total number of evaluations included 731 from patients and 355 from family members. Response rates were defined as the number of usable surveys returned by eligible evaluators divided by the number of surveys distributed to those evaluators. Response rates were 45% for patients (731/1612) and 75% for family members (355/475). Ratings for the QEOLC and general component of the QOC questionnaire were almost twice those documented for the end-of-life component of the QOC (Table 2). Lower overall scores on the QOCeol were largely related to the fact that patients and family members reported that many of these items had not been discussed and thus these items were assigned a value of zero. Between-group differences for each QOCeol component are described for both patient and family member surveys by race/ethnicity or socioeconomic status in Appendix C.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Patients and Family Members

| Patients | Family members | |

|---|---|---|

| Unique-evaluator characteristics: | ||

| Number of evaluators | 695 | 345 |

| Northwestern U.S. study site, n (%) | 403 (58.0) | 194 (56.2) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| African American | 167 (24.0) | 81 (23.5) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 455 (65.5) | 217 (62.9) |

| Other minority | 73 (10.5) | 31 (9.0) |

| Not reported | 0 (0.0) | 16 (4.6) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 380 (54.7) | 94 (27.2) |

| Female | 315 (45.3) | 247 (71.6) |

| Not reported | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.2) |

| Age, mean (SD)a | 65.4 (4.3) | 57.5 (13.6) |

| Education, n (%) | ||

| Eighth grade or less | 47 (6.8) | 6 (1.7) |

| Some high school | 74 (10.6) | 23 (6.7) |

| High school diploma or equivalent | 151 (21.7) | 61 (17.7) |

| Some college or trade school | 206 (29.6) | 121 (35.1) |

| Four-year college degree | 94 (13.5) | 67 (19.4) |

| Graduate or professional school | 97 (14.0) | 47 (13.6) |

| Not reported | 26 (3.7) | 20 (5.8) |

| Average monthly pre-tax income, past year, n (%) | ||

| ≤$500 | 33 (4.7) | |

| $501–$1000 | 129 (18.6) | |

| $1,001–$1,500 | 84 (12.1) | |

| $1,501–$2,000 | 64 (9.2) | |

| $2,001–$3,000 | 70 (10.1) | |

| $3,001–$4,000 | 61 (8.8) | |

| $4,001+ | 148 (21.3) | |

| Not reported | 106 (15.3) | |

| Seen in inpatient or outpatient setting | ||

| Inpatient | 522 (75.1) | 294 (85.2) |

| Outpatient | 171 (24.6) | 51 (14.8) |

| Both | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Diagnosed withb., n (%) | ||

| Advanced cancer | 176 (25.3) | |

| Advanced lung disease | 48 (6.9) | |

| Congestive heart failure | 61 (8.8) | |

| End-stage liver disease | 52 (7.5) | |

| Autoimmune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) | 25 (3.6) | |

| Family member also completed evaluation, n (%) | 202 (29.1) | |

| # Evaluations per evaluator, median (range) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) |

| Evaluation-specific characteristics: | ||

| Number of evaluations | 731 | 355 |

| Single-item self-rated health status, median (IQR)c | 2 (2) | |

| Rating of quality of end-of-life care,d mean (SD) | 8.3 (1.9) | 8.4 (2.0) |

| Rating of quality of communication, mean (SD) | ||

| General communicatione | 8.5 (1.9) | 8.5 (2.0) |

| End-of-life communicationf | 4.6 (3.2) | 5.3 (3.4) |

Ages were reported by only 322 of the 345 family members.

Of the patients completing surveys, 49.1% had none of the five diagnoses listed, 49.8% had one, and 1.2% had two.

Respondent's rating of current health (reversed scoring): 1=poor, 2=fair, 3=good, 4=very good, 5=excellent. Ratings were provided on 693 surveys.

Ten-item scale applicable to all respondent types; computed as the mean of available items from the 10-item pool, with original response range 0 (poor) to 10 (absolutely perfect). Scores were available from 725 patient surveys and 352 family member surveys.

Six-item scale computed as mean of available items: 0 (very worst) to 10 (very best). Scores were available from 704 patient surveys and 344 family member surveys.

Seven-item scale computed as mean of available items: 0 (very worst) to 10 (very best). Scores were available from 623 patient surveys and 300 family member surveys.

SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile ratio.

Patient perceptions of end-of-life care and communication

Among patients, no significant associations were identified between race/ethnicity or socioeconomic status and patient ratings on the QEOLC or the QOCgen. However, all three predictors of interest were significantly associated with patient ratings on the QOCeol, with higher scores provided by patients from racial/ethnic minority groups, patients with lower income, and patients with lower educational attainment (Table 3). However, when evaluating whether or not a patient reported performance of a communication aspect, we found that patients from minority groups and those with lower income and education were significantly more likely to report that a communication aspect had occurred than were non-Hispanic white patients and those with higher income and education levels. Assessing only the items that patients reported as occurring, ratings on the QOCeol did not differ significantly by race or socioeconomic status (Table 4).

Table 3.

Race and Socioeconomic Status: Associations with Ratings of End-of-Life Care and Communicationa

| Patient ratings | Family ratings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Predictors | b | p | b | p |

| QEOLC | Evaluator race/ethnicityb | 0.500 | 0.006 | ||

| African American | −0.180 | −0.646 | |||

| Other minority | −0.132 | −0.948 | |||

| Evaluator educationc | −0.019 | 0.731 | −0.162 | 0.098 | |

| Evaluator incomed | 0.042 | 0.320 | |||

| QOCgen | Evaluator race/ethnicitye | >0.500 | 0.009 | ||

| African American | −0.136 | −0.567 | |||

| Other minority | −0.006 | −0.935 | |||

| Evaluator educationf | 0.010 | 0.861 | −0.086 | 0.370 | |

| Evaluator incomeg | 0.031 | 0.436 | |||

| QOCeol | Evaluator race/ethnicityh | 0.026 | 0.110 | ||

| African American | 0.831 | 1.088 | |||

| Other minority | 0.516 | −0.041 | |||

| Evaluator educationi | −0.273 | 0.006 | −0.687 | <0.001 | |

| Evaluator incomei | −0.390 | <0.001 | |||

Associations were based on cross-classified (evaluator by trainee) hierarchical models, using full maximum likelihood estimation, with continuous linear outcomes and with level-1 slopes fixed over cross-classified level-2 units.

Patient model adjusted for recruitment site; trainee age, postgraduate year, and race; patient gender, SF1 health rating, inpatient vs. outpatient site of patient-trainee interaction, and four diagnoses (cancer, congestive heart failure, end-stage liver disease, and AIDS). Family model adjusted for recruitment site.

Patient model adjusted for recruitment site and inpatient/outpatient. Family model adjusted for patient race and recruitment site.

Model adjusted for two patient diagnosis indicators (cancer and AIDS), education, SF1 health rating, inpatient/outpatient, recruitment site, and the trainee's postgraduate year.

Patient model adjusted for recruitment site; trainee's postgraduate year and race; one patient diagnosis (AIDS), inpatient/outpatient, and SF1. Family model adjusted for recruitment site.

Patient model adjusted for recruitment site and inpatient/outpatient. Family model adjusted for recruitment site, trainee age, and family race.

Model adjusted for recruitment site, trainee's post-graduate year, patient education, SF1, and inpatient/outpatient.

Patient model adjusted for patient age and inpatient/outpatient. Family model adjusted for recruitment site; trainee age, postgraduate year, and race; family gender, age, and inpatient/outpatient.

Patient model for education adjusted for patient race. There were no confounders of the family education or patient income model.

QEOLC, Quality of End-of-Life Care Questionnaire; QOCgen, general communication score from the Quality of Communication questionnaire; QOCeol, end-of-life care communication score from the Quality of Communication questionnaire.

Table 4.

Race and Socioeconomic Status: Evaluation of QOCeol Items Not Performed and Ratings of Only Items Performeda

| Patients | Family members | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome (QOCeol) | Predictors | b | Ratiob | p | b | Ratiob | p |

| Number of aspects not performedc | Evaluator race/ethnicityd | <0.001 | 0.001 | ||||

| African American | −0.330 | 0.719 | <0.001 | −0.529 | 0.589 | <0.001 | |

| Other minority | −0.249 | 0.780 | 0.045 | −0.300 | 0.741 | 0.138 | |

| Evaluator educatione | 0.119 | 1.126 | <0.001 | 0.119 | 1.126 | 0.021 | |

| Evaluator incomef | 0.131 | 1.140 | <0.001 | ||||

| Average rating of performanceg | Evaluator race/ethnicityh | >0.500 | 0.006 | ||||

| African American | −0.057 | 0.827 | −0.868 | 0.013 | |||

| Other minority | −0.420 | 0.189 | −1.068 | 0.021 | |||

| Evaluator educationi | 0.055 | 0.478 | −0.244 | 0.045 | |||

| Evaluator incomej | 0.069 | 0.220 | |||||

Associations were based on cross-classified (evaluator by trainee) hierarchical regression models and with level-1 slopes fixed over cross-classified level-2 units.

Event-rate ratio.

Modeled as an over-dispersed Poisson outcome, using a nonlinear log link and penalized quasi-likelihood estimation.

There were no confounders of race in either the patient or family model. Because the Poisson model offered no test for the overall significance of race, the reported test was based on a cross-classified linear model. The reported tests for significance of the separate dummy indicators for race were based on Wald's tests from the Poisson model, and were similar to those from the linear model.

There were no confounders of education in the patient model; the family model included adjustment for evaluator race.

There were no confounders of income.

Average was based on aspects the trainee was reported to have performed; modeled as a continuous outcome, using an identity link and full maximum likelihood estimation.

The patient model included adjustment for patient gender, cancer diagnosis, the SF-1 health rating, inpatient/outpatient, trainee age, and recruitment site. The family model included adjustment for recruitment site and inpatient/outpatient.

The patient model included adjustment for patient gender, diagnosis of cancer and/or lung disease, inpatient/outpatient, recruitment site, and trainee age. The family model included adjustment for evaluator's race and recruitment site.

The model included adjustment for patient gender and education, cancer diagnosis, inpatient/outpatient, and recruitment site.

QOCeol, end-of-life care communication score from the Quality of Communication questionnaire.

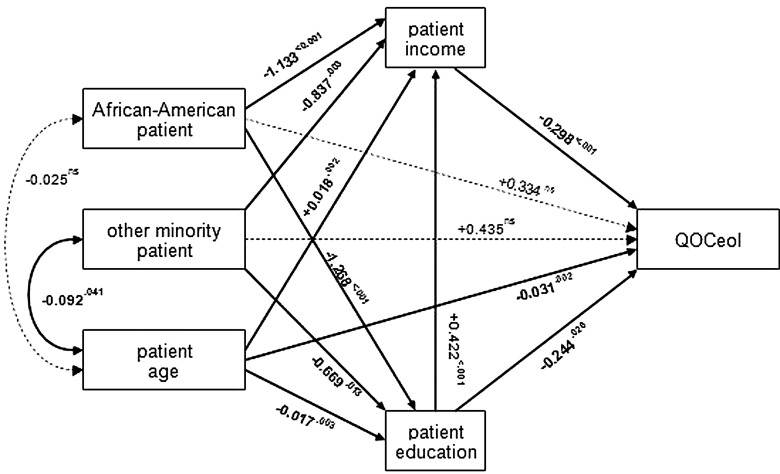

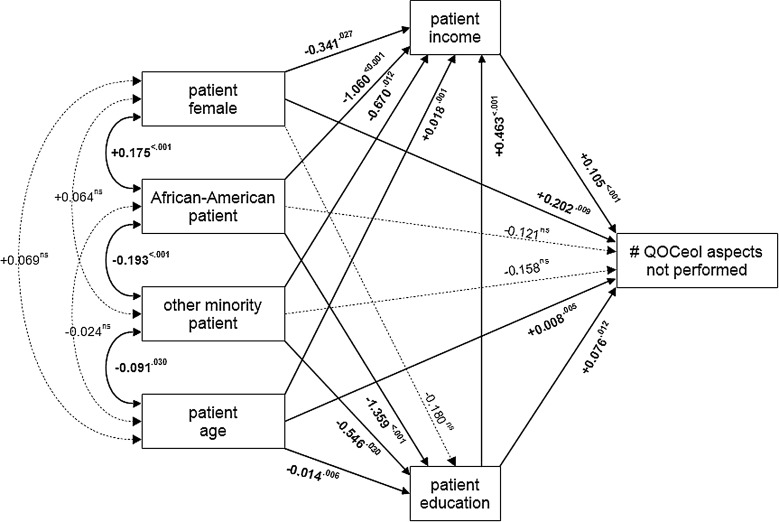

In order to further explore potential relationships between race and socioeconomic status and their associations with patients' ratings of their physician's end-of-life communication, we tested the path model shown in Figure 1. In this model, we assumed the patient's race and age to be exogenous variables, with the socioeconomic variables functioning as mediators. We tested all direct paths from the exogenous and mediating variables to the outcome, as well as all paths between the exogenous variables and the mediators. All structural (i.e., unidirectional) coefficients were statistically significant except the direct paths from the race indicators to the outcome, suggesting that patient educational attainment and income may act as mediators of the association between patient race/ethnicity and QOCeol ratings. In this model, race/ethnicity had no independent effect apart from its covariance with socioeconomic status. Similar procedures were performed to assess potential relationships between race or socioeconomic status and their associations with the number of QOCeol aspects that were not performed (Fig. 2). As in the first model, all structural coefficients were statistically significant except the direct paths from the race indicators to the outcome.

FIG. 1.

Path model of associations between patient factors and the Quality of Communication (QOC) Questionnaire's end-of-life communication (QOCeol) ratings.

FIG. 2.

Path model of associations between patient predictors and the number of Quality of Communication Questionnaire's (QOC) end-of-life communication (QOCeol) items that were not performed.

Family member perceptions of end-of-life care and communication

Unlike patients, family members' race/ethnicity was significantly associated with their QEOLC ratings and their QOCgen scores, with lower ratings provided when the patient was from a racial/ethnic minority group. Like patients, no significant associations were identified between family members' education level and their ratings on the QEOLC or the QOCgen (Table 3).

As seen with patients, family members with lower educational attainment provided significantly higher ratings on the QOCeol (Table 3). Like patients, family members from racial/ethnic minority groups and those with lower educational levels were more likely to report that an aspect of communication about end-of-life care occurred, with the difference for African-Americans achieving statistical significance. However, unlike patients, when assessing only the items that family members reported as occurring, significant associations between both race/ethnicity and educational attainment persisted. Racial/ethnic minorities and those with higher educational attainment provided lower ratings of trainee performance than did their counterparts (Table 4).

Discussion

We performed an observational analysis to detect associations between race/ethnicity or two indicators of socioeconomic status (i.e., education, income) with patient and family perceptions of end-of-life care provided by physicians-in-training. To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess these associations. We identified several significant relationships that underscore the complicated nature of ratings of health care as it relates to race, income, and education, and hypothesized path models provided information describing the role of socioeconomic status as a mediator in this complex interplay.

Evaluations of factors affecting satisfaction with health care have identified associations between race or socioeconomic status and ratings of overall health care quality and access to care, with lower ratings among minority patients and those with lower income.14,15 Although studies have addressed the impact of perceived racial discrimination on general ratings of health care, limited information is available to enrich our understanding of the impact of race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status on perceptions about care and communication that are specific to end-of-life care. Available information would suggest findings similar to those experienced in the broader healthcare context, where minority individuals and those with lower income perceive a lack of communication about end-of-life care.16–18 However, we replicated these results for only some of the associations we tested. Family members from racial/ethnic minority groups rated their physicians significantly lower on the QEOLC score and the general communication component of the QOC. They also gave lower ratings on the end-of-life communication component of the QOC when considering only those aspects of care that the physician was reported to have performed.

With regard to the outcome that was most specifically relevant to communication about end-of-life care (QOCeol item descriptions in Appendix B), our results showed associations that were the opposite of expected findings. Among patients, we found that racial minority status, lower income, and lower education level were associated with significantly higher ratings of physicians' communication about end-of-life care. We further discovered that these differences were primarily attributable to the number of issues reported as discussed and not to the ratings of discussions that did occur. Among family members, higher summary ratings were significantly associated with lower education, but not with race/ethnicity. When the number of communication issues addressed and their ratings were considered separately, family results were mixed. Respondents from racial/ethnic minority groups and with lower educational attainment reported the discussion of more end-of-life issues; and those with lower education gave higher ratings to the discussions that occurred. However, family members from racial/ethnic minority groups gave lower ratings to discussions that occurred. Differences between family and patient considerations of end-of-life issues have been described,19,20 and the observed discordance between family and patient ratings of care and communication emphasizes the importance of perspective. These differences may occur in part because patients and family members witness different communication or care events with clinicians. Even when patients and family members are a part of the same encounter, both parties approach the discussion from different vantage points and this may affect assessments of the experience.

It is interesting to consider potential explanations for our unexpected finding that, when compared to minority patients and those with lower income and education levels, individuals of non-Hispanic white race and with higher socioeconomic status were more likely to report that a physician failed to address issues related to end-of-life care. These findings conflict with prior research demonstrating that information sharing and decision making occur more frequently between physicians and white patients with higher levels of education than with minorities and those with limited education.6,21,22 One potential explanation for our findings may relate to the level of engagement in discussing end-of-life care that patients with higher education and income levels expect from their physicians. Physicians-in-training may lack the experience and confidence needed to broach in-depth discussions about end-of-life care with ease and comfort,23,24 potentially resulting in unmet expectations among patients with higher income and education levels. This could contribute to a discounting of conversations that may have occurred, but that the patient felt inadequately met their informational and emotional needs. Furthermore, health literacy has been identified as a factor that influences preferences about end-of-life care, and an important relationship exists between education level and the ability to process and understand healthcare information.25 There is also evidence that individuals trained to provide ratings of communication provide more accurate and critical ratings than untrained patients.26 Together, these findings suggest that patient expectations, education, and training may have an important influence on ratings of end-of-life communication skills. Results of hypothesized path models suggest that future investigations of associations between race and provision of end-of-life care and communication would benefit from consideration of education level and income as potential mediators between race/ethnicity and measures of physician–patient communication.

Another important consideration in the evaluation of communication about end-of-life care relates to the site of care where physician–patient encounters occur. Prior research has demonstrated that non-Hispanic white patients and those from higher socioeconomic strata have better access than their counterparts to outpatient care,27,28 a location where communication about end-of-life issues is often limited.29,30 Had such patients been similarly overrepresented in the outpatient setting in our study, this might have explained their reports that fewer end-of-life topics were addressed. However, in our sample, it was minorities and patients of lower socioeconomic status who were overrepresented in the outpatient setting. Therefore, adjustment for site of care (inpatient versus outpatient) did not account for the observed associations.

This study has several important limitations. First, the degree to which each patient's underlying illness affected the amount of patient–physician communication regarding end-of-life care is unknown. However, the eligibility criteria aimed to include patients for whom end-of-life conversations would be appropriate regardless of specific diagnosis. Second, our response rate for these seriously ill patients is relatively low at 45%, likely reflecting their frailty; this low response rate could introduce responder bias. Third, lack of information about trainee socioeconomic status impairs our ability to assess its effect on the evaluated associations. Trainee race/ethnicity was evaluated as a potential confounder of the relationship between respondent race/ethnicity or socioeconomic status and ratings of care and was included in our final, adjusted models. Last, we did not account for multiple comparisons that may have led to spurious associations but attempted to minimize the chance of false-positive associations by specifying the predictors of interest a priori.

In conclusion, although we found all three of our predictors of interest—race/ethnicity, income, and education—to have associations with patient ratings of care and communication that specifically addressed end-of-life issues, we found that these associations may be related more to differences in reports of whether various aspects of communication about end-of-life care occurred, as opposed to the conduct of poor quality communication. We also present evidence that some of the identified associations between race/ethnicity and ratings of communication may be mediated by income and education, which suggests the importance of including these variables in future studies of racial disparities in patient–physician communication about palliative and end-of-life care. Finally, we found that the associations between race/ethnicity or socioeconomic status and ratings of end-of-life care seemed to be different for patients compared to family members and these differences warrant further investigation. Our results provide interesting insights regarding care delivered by trainees and this complex topic warrants further investigation to better understand how these factors should be considered when developing outcome measures as well as interventions to improve the quality of end-of-life care.

Appendix A. Improving Clinician Communication Skills

Screening Checklist—Patient

Patient Title: Mr. / Mrs. / Ms. / Dr. Patient name: ______________________________

Sex: M / F Patient MRN: _______________________________________

| Patient contact info: | _______________________________________ | in hospital:______________________________ |

| _______________________________________ | room number:______________________________ | |

| _______________________________________ |

□ Patient has died

| Patient DOB: | ___ / ___ / ______ |

| Patient ethnicity: | ___Hispanic |

| ___Non-Hispanic | |

| ___Undocumented | |

| ___Documented as “not known” | |

| Patient race: | ___White |

| ___Black/African American | |

| ___Asian | |

| ___Pacific-Islander | |

| ___Native American/Alaska Native | |

| ___Other: __________________________________________ | |

| ___Undocumented | |

| ___Documented as “not known” |

Resident/NP student name: __________________________________

R1/ R2 /R3/NP Pre/Post Today's date: ____________________

Clinical rotation site/service: ___________________________________

# of pt visits to date: ____________________ with this provider

Date of last note by this provider: ____________________

Number of days in hospital documented on last note by this provider: ______________

| Exclusion criteria: | □ significant dementia or delirium |

| □ psychosis | |

| □ hospitalization for suicidal ideation in the last year | |

| □ fewer than 3 outpatient visits with the resident | |

| □ less than 3 days in hospital (acute care only) | |

| □ non-English speaking | |

| □ less than 18 years of age | |

| □ no address in medical record | |

| □ prisoner | |

| □ other:__________________________________________ |

Inclusion criteria (must have one):

□ Enrolled in a hospice program or seen by a palliative care service

□ Documentation of end-of-life communication or POLST/DNR completion

□ Advanced Cancer

• any stage IV cancer, or

• metastatic cancer, or

• recurrent cancer (except skin cancer), or

• cancer with low functional status (too sick for treatment)

□ Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD, emphysema, chronic bronchitis)

• FEV1<35% predicted, or

• oxygen dependent

□ Restrictive Lung Disease

• fibrotic lung disease: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) with TLC<50% predicted, or

• ALS with chronic respiratory failure, hypercapnia, or respiratory muscle weakness

□ Congestive Heart Failure (CHF)

• ejection fraction equal or less than 30%, or

• functional deficits matching NYHA class III or IV

□ End-Stage Liver Disease (ESLD)

• MELD score ≥18, or

• Childs class C cirrhosis, or

• variceal bleed, or

• refactory ascites, or

• spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP)

□ Has a Charlson comorbidity score* (CCS) point value of ≥5 below (please check all that apply):

___ Myocardial Infarction=1 point

___ Congestive heart failure=1 point

___ Peripheral vascular disease=1 point

___ Cerebrovascular disease=1 pt point

___ Dementia=1 point

___ COPD=1 point

___ Connective tissue disease=1 point

___ Peptic ulcer disease=1 point

___ Mild liver disease=1 point

___ Diabetes=1 point

___ Hemiplegia 2=points

___ Moderate to severe renal disease=2 points

____ Diabetes with organ damage=2 points

___ Any tumor within the last 5 years=2 points

___ Lymphoma=2 points

___ Leukemia=2 points

___ Moderate to severe liver disease=3 points

___ Metastatic solid tumor=6 points

___ AIDS (HIV C3)=6 pt points

___ Points for age (50+=1 pt point; 60+=2 points; 70+=3 points; 80+=4 points; 90+=5 pt points; 100+=6 points)

___ Point Total

□ Inpatients only: ≥80 years old (no disease-specific criteria required)

□ Inpatients only: UHC Risk of Mortality (ROM) score of major or extreme

Additional inclusion criteria for ICU (if applicable):

□ mechanical ventilation ≥72 hours

□ ICU stay ≥7 days

□ APACHE score >25

Patient status: □ able to communicate

□ unable to communicate

Family (complete only if patient is unable to communicate)

Exclusion criteria: □ non-English speaking

□ less than 18 years of age

*Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR: A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–383.

Appendix B. Instruments (Details Provided from Surveys Given to Patients)

Quality of End-of-life Care Questionnaire (QEOLC)

• Circle or check one number for each item

• Scale from 0 (Poor) to 10 (Absolutely perfect)

• Rate your doctor for each of the following:

∘ Helps you and your family get consistent information from the entire health care team

∘ Makes you feel confident that you will not be abandoned prior to death

∘ Talks with you in an honest and straightforward way

∘ Openly and willingly communicates with your family

∘ Takes into account your wishes when treating pain and symptoms

∘ Knowledgeable about the care you need during the dying process

∘ Responsive to your emotional needs

∘ Treats the whole person, not just the disease

∘ Admits when he/she does not know something

∘ Acknowledges and respects your personal beliefs

Quality of Communication Questionnaire: General Communication (QOCgen)

• Circle or check one number for each item

• Scale from 0 (Poor) to 10 (Absolutely perfect)

• How good is this resident at:

∘ Using words that you can understand

∘ Looking you in the eye

∘ Answering all questions about your illness and treatment

∘ Listening to what you have to say

∘ Caring about you as a person

∘ Giving you his or her full attention

Quality of Communication Questionnaire: End-of-Life Communication (QOCeol)

• Circle or check one number for each item

• Scale from 0 (Poor) to 10 (Absolutely perfect)

• How good is this resident at:

∘ Talking with you about your feelings concerning the possibility that you may get sicker

∘ Talking with you about the details concerning the possibility that you may get sicker

∘ Talking to you about how long you may have to live

∘ Talking with you about what dying might be like

∘ Involving you in decisions about the treatments that you want if you get too sick to speak for yourself

∘ Asking about the things in life that are important to you

∘ Asking about your spiritual or religious beliefs

Appendix C. Respondent Race/Ethnicity by Reports that Specific Aspects of End-of-Life Communication Did Not Occur

| African American | Other Minority | Non-Hispanic White | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RACE Patient Surveys | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Did not talk with you about your feelings concerning the possibility that you may get sicker | 25 | 14.5 | 10 | 13.0 | 124 | 25.7 |

| Did not talk with you about the details concerning the possibility that you may get sicker | 26 | 15.1 | 14 | 18.2 | 136 | 28.2 |

| Did not talk with you about how long you may have to live | 75 | 43.6 | 34 | 44.2 | 266 | 55.2 |

| Did not talk with you about what dying may be like | 80 | 46.5 | 37 | 48.1 | 288 | 59.8 |

| Did not involve you in decisions about treatments you want if you get too sick to speak for yourself | 67 | 39.0 | 28 | 36.4 | 215 | 44.6 |

| Did not ask about the things in life that are important to you | 49 | 28.5 | 21 | 27.3 | 172 | 35.7 |

| Did not ask about your spiritual or religious beliefs | 53 | 30.8 | 32 | 41.6 | 242 | 50.2 |

| Family Surveys | ||||||

| Did not talk with you about your feelings that the patient might get sicker | 14 | 17.1 | 6 | 18.2 | 78 | 34.8 |

| Did not talk with you about when or how the patient might get sicker | 17 | 20.7 | 6 | 18.2 | 75 | 33.5 |

| Did not talk with you about how long the patient might have to live | 29 | 35.4 | 15 | 45.5 | 117 | 52.5 |

| Did not ask about the kinds of treatments the patient would want if unable to communicate | 12 | 14.6 | 6 | 18.2 | 59 | 26.3 |

| Did not ask about the things in life that are important to the patient | 21 | 25.6 | 11 | 33.3 | 94 | 42.0 |

| Did not ask about your spiritual or religious beliefs | 23 | 28.0 | 16 | 48.5 | 123 | 54.9 |

| High school or less | Trade school or some college | College degree or higher | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDUCATIONPatient Surveys | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Did not talk with you about your feelings concerning the possibility that you may get sicker | 46 | 16.4 | 48 | 21.8 | 62 | 30.2 |

| Did not talk with you about the details concerning the possibility that you may get sicker | 50 | 17.9 | 52 | 23.6 | 71 | 34.6 |

| Did not talk with you about how long you may have to live | 127 | 45.4 | 115 | 52.3 | 130 | 63.4 |

| Did not talk with you about what dying may be like | 141 | 50.4 | 124 | 56.4 | 135 | 65.9 |

| Did not involve you in decisions about treatments you want if you get too sick to speak for yourself | 102 | 36.4 | 94 | 42.7 | 109 | 53.2 |

| Did not ask about the things in life that are important to you | 83 | 29.6 | 65 | 29.5 | 90 | 43.9 |

| Did not ask about your spiritual or religious beliefs | 100 | 35.7 | 101 | 45.9 | 121 | 59.0 |

| Family Surveys | ||||||

| Did not talk with you about your feelings that the patient might get sicker | 13 | 14.4 | 40 | 32.0 | 44 | 36.7 |

| Did not talk with you about when or how the patient might get sicker | 14 | 15.6 | 44 | 35.2 | 39 | 32.5 |

| Did not talk with you about how long the patient might have to live | 33 | 36.7 | 62 | 49.6 | 65 | 54.2 |

| Did not ask about the kinds of treatments the patient would want if unable to communicate | 17 | 18.9 | 23 | 18.4 | 36 | 30.0 |

| Did not ask about the things in life that are important to the patient | 22 | 24.4 | 54 | 43.2 | 49 | 40.8 |

| Did not ask about your spiritual or religious beliefs | 30 | 33.3 | 62 | 49.6 | 70 | 58.3 |

| $1,000/month or Less | $1,000–$3,000/month | More than $3,000/month | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INCOMEPatient Surveys | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Did not talk with you about your feelings concerning the possibility that you may get sicker | 17 | 9.9 | 47 | 20.8 | 68 | 30.1 |

| Did not talk with you about the details concerning the possibility that you may get sicker | 18 | 10.5 | 51 | 22.6 | 76 | 33.6 |

| Did not talk with you about how long you may have to live | 64 | 37.4 | 117 | 51.8 | 137 | 60.6 |

| Did not talk with you about what dying may be like | 74 | 43.3 | 122 | 54.0 | 151 | 66.8 |

| Did not involve you in decisions about treatments you want if you get too sick to speak for yourself | 53 | 31.0 | 85 | 37.6 | 124 | 54.9 |

| Did not ask about the things in life that are important to you | 34 | 19.9 | 74 | 32.7 | 95 | 42.0 |

| Did not ask about your spiritual or religious beliefs | 53 | 31.0 | 94 | 41.6 | 134 | 59.3 |

Acknowledgments

Funding provided by: NIH-NINR R01NR009987, NIH-NHLBI T32 HL007287, TPM 61-037

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.LaViest TA, Nickerson KJ, Bowie JV. Attitudes about racism, medical mistrust, and satisfaction with care among African American and white cardiac patients. Med Care Res Rev 2000;57Suppl 1:146–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weech-Maldonado R, Hall A, Bryant T, Jenkins KA, Elliott MN: The relationship between perceived discrimination and patient experiences with health care. Med Care 2012;50:S62–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sorkin DH, Ngo-Metzger Q, De Alba I: Racial/ethnic discrimination in health care: Impact on perceived quality of care. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25:390–396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hausmann LR, Hannon MJ, Kresevic DM, Hanusa BH, Kwoh CK, Ibrahim SA: Impact of perceived discrimination in healthcare on patient-provider communication. Med Care 2011;49:626–633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perez D, Sribney WM, Rodríguez MA: Perceived discrimination and self-reported quality of care among Latinos in the United States. J Gen Intern Med 2009; 24:548–554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siminoff LA, Graham GC, Gordon NH: Cancer communication patterns and the influence of patient characteristics: Disparities in information-giving and affective behaviors. Patient Educ Couns 2006;62:355–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiscella K, Goodwin MA, Stange KC: Does patient educational level affect office visits to family physicians? J Natl Med Assoc 2002;94:1571–65 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Truog RD, Campbell ML, Curtis JR, Haas CE, Luce JM, Rubenfeld GD, Rushton CH, Kaufman DC, American Academy of Critical Care Medicine: Recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: A consensus statement by the American College [corrected] of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med 2008;36:953–963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engelberg R, Downey L, Curtis JR: Psychometric characteristics of a quality of communication questionnaire assessing communication about end-of-life care. J Palliat Med 2006;9:1086–1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curtis JR, Wenrich MD, Carline JD, Shannon SE, Ambrozy DM, Ramsey PG: Understanding physicians' skills at providing end-of-life care perspectives of patients, families, and health care workers. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:41–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Engelberg RA, Downey L, Wenrich MD, Carline JD, Silvestri GA, Dotolo D, Nielsen EL, Curtis JR: Measuring the quality of end-of-life care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010;39:951–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wachter RM, Luce JM, Hearst N, Lo B: Decisions about resuscitation: Inequities among patients with different diseases but similar prognoses. Ann Intern Med 1989;111:525–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curtis JR, Wenrich MD, Carline JD, Shannon SE, Ambrozy DM, Ramsey PG: Patients' perspectives on physician skill in end-of-life care: Differences between patients with COPD, cancer, and AIDS. Chest 2002;122:356–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chou WY, Wang LC, Finney Rutten LJ, Moser RP, Hesse BW: Factors associated with Americans' ratings of health care quality: What do they tell us about the raters and the health care system? J Health Commun 2010;15:147–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haviland MG, Morales LS, Dial TH, Pincus HA: Race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and satisfaction with health care. Am J Med Qual 2005;20:195–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fischer SM, Sanaia A, Min SJ, Kutner J. Advance directive discussions: Lost in translation or lost opportunities? J Palliat Med 2012;15:86–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Caldwell E, Greenlee H, Collier AC: The quality of patient-doctor communication about end-of-life care: A study of patients with advanced AIDS and their primary care clinicians. AIDS 1999;13:1123–1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Welch LC, Teno JM, Mor V: End-of-life care in black and white: Race matters for medical care of dying patients and their families. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:1145–1153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, McIntyre L, Tulsky JA: Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA 2000; 284:2476–2482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heyland DK, Dodek P, Rocker G, Groll D, Gafni A, Pichora D, Shortt S, Tranmer J, Lazar N, Kutsogiannis J, Lam M; Canadian Researchers End-of-Life Network(CARENET): What matters most in end-of-life care: Perceptions of seriously ill patients and their family members. CMAJ 2006;174:627–633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Willems S, De Maesschalck S, Deveugele M, Derese A, De Maeseneer J: Socio-economic status of the patient and doctor-patient communication: Does it make a difference? Patient Educ Couns 2005;56:139–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaplan SH, Gandek B, Greenfield S, Rogers W, Ware JE: Patient and visit characteristics related to physicians' participatory decision-making style. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Med Care 1995;33:1176–1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weissman DE, Ambuel B, Norton AJ, Wang-Cheng R, Schiedermayer D: A survey of competencies and concerns in end-of-life care for physician trainees. J Pain Symptom Manage 1998;15:82–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sullivan AM, Lakoma MD, Block SD: The status of medical education in end-of-life care: A national report. J Gen Intern Med 2003;18:685–695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow M, Gillick MR, Cook EF, Shaykevich S, Abbo ED, Lehmann L: Health literacy not race predicts end-of-life care preferences. J Palliat Med 2008;11:754–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fiscella K, Franks P, Srinivasan M, Kravitz RL, Epstein R: Ratings of physician communication by real and standardized patients. Ann Fam Med 2007;5:151–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shi L, Tsai J, Higgins PC, Lebrun LA: Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in access to care and quality of care for US health center patients compared with non-health center patients. J Ambul Care Manage 2009;32:342–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Politzer RM, Yoon J, Shi L, Hughes RG, Regan J, Gaston MH: Inequality in America: The contribution of health centers in reducing and eliminating disparities in access to care. Med Care Res Rev 2001;58:234–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Nielsen EL, Au DH, Patrick DL: Patient-physician communication about end-of-life care for patients with severe COPD. Eur Respir J 2004;24:200–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Janssen DJ, Spruit MA, Schols JM, Wouters EF: A call for high-quality advance care planning in outpatients with severe COPD or chronic heart failure. Chest 2011;139:1081–1088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]