Abstract

Purpose: To investigate the antioxidant properties and biological functions of ascorbic acid (AA) on trabecular meshwork (TM) cells.

Methods: Primary cultures of porcine TM cells were supplemented for 10 days with increasing concentrations of AA. Antioxidant properties against cytotoxic effect of H2O2 were evaluated by monitoring cell viability. Redox-active iron was quantified using calcein-AM. Intracellular reactive oxygen species (iROS) production was quantified using H2DCFDA. Ferritin and cathepsin protein levels were analyzed by Western blot. Autophagy was evaluated by monitoring lipidation of LC3-I to LC3-II. Lysosomal proteolysis and cathepsins activities were quantified using specific fluorogenic substrates.

Results: AA exerts a dual effect against oxidative stress in TM cells, acting as an anti-oxidant or a pro-oxidant, depending on the concentration used. The pro-oxidant effect of AA was mediated by free intracellular iron and correlated with increased protein levels of ferritin and elevated iROS. In contrast, antioxidant properties correlated with lower ferritin and basal iROS content. Ascorbic acid supplementation also caused induction of autophagy, as well as increased lysosomal proteolysis, with the latter resulting from higher proteolytic activation of lysosomal cathepsins in treated cultures.

Conclusions: Our results suggest that the reported decrease of AA levels in plasma and aqueous humor can compromise lysosomal degradation in the outflow pathway cells with aging and contribute to the pathogenesis of glaucoma. Restoration of physiological levels of vitamin C inside the cells might improve their ability to degrade proteins within the lysosomal compartment and recover tissue function.

Introduction

It is well established that ascorbic acid (AA) is present in the ocular tissues of many animals at concentrations several times higher than plasma levels. In the aqueous humor (AH), a wide range of AA levels has been found among different species, with the AH concentrations of AA in diurnal animals being higher than in nocturnal animals.1 Although it widely varies among individuals and the methodology used, the typical concentration of AA in the human AH is estimated to be 150–250 μg/mL. Such high concentration, together with its known oxyradical scavenging properties, suggest a major function of AA in the AH to be that of protecting against oxidative damage, in particular light-induced damage. Indeed, AA has been proposed to be the major contributor to the antioxidant activity of porcine and bovine AH.2 In addition to its protective role against free-radical damage, a plethora of biological and physiological functions have been attributed to AA, the majority of which are mediated by acting as a cofactor for a variety of enzymes, including hydrolases, hypoxia inducible factor system, and histone demethylation.3 Rather than participating as a catalyst, it is believed that the role of AA in all these biochemicals reactions is to keep metal transitions, as iron or copper, associated with the enzymes in their required reduced conditions.

The specific function of AA in the outflow pathway is not clear. A number of studies in the literature have reported a lowering intraocuIar pressure (IOP) effect of AA following oral, topical, or intravenous application of the vitamin in different species, as well as in human glaucoma patients.4–6 The physiological and molecular mechanisms by which AA decreases IOP are unknown. Suggested mechanisms include a reduction in the rate of AH flow, bulk drainage of posterior uveoscleral routes, increased facility, and antioxidant function. In addition, experiments conducted in cultured trabecular meshwork (TM) cells and perfused organ culture have shown the ability of AA to modulate the synthesis of various extracellular matrix molecules such as collagen, elastin, laminin, fibronectin, and glycosaminoglycans.7–9

Several investigators have reported reduced levels of AA in the AH of patients with primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) and secondary glaucomas.10–12 Lower AA plasma concentrations have also been found in POAG patients as well as in patients with normal-tension glaucoma.13,14 Very interestingly, a very recent study has demonstrated a significant association between a polymorphism in the AA transporter SLC23A2 with such lower plasma concentrations of AA and with higher risk of POAG.14 Based on all this evidence, it is of paramount importance to define the exact roles of AA in the outflow pathway tissue and physiology. Here we investigate the antioxidant properties of AA in TM cells.

Methods

Reagents

Ascorbic acid, calcein-acetoxymethyl ester (calcein-AM), desferoxamine (DFO), leupeptin, cloroquine, and H2O2 were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Salicylaldehyde isonicotinoyl hydrazone (SIH) was kindly provided by Katherine J. Franz (Department of Chemistry, Duke University).

Cell culture

Primary cultures of porcine TM cells were prepared from porcine cadaver eyes, obtained from a local abattoir less than 5 hours postmortem, and maintained as previously described.15 Briefly, the TM was dissected and digested with 2 mg/mL of collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich, C2674) for 1 h at 37°C. The digested tissue was placed in gelatin-coated 35-mm dishes and cultivated in low-glucose Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium with l-glutamine and 110 mg/L sodium pyruvate (Gibco, 11885), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, 10082-147), 100 mM nonessential amino acids (Gibco, 11140-050), 100 units/mL penicillin and 100 mg/mL streptomycin sulfate, and 0.25 mg/mL amphotericin B (Gibco, 15240-062). Cells were maintained and propagated until passage three at 37°C in humidified air with 5% CO2 incubator. Cell lines were subcultivated 1:2 when confluent.

Drug treatments

Confluent cultures of porcine TM cells were supplemented with 100, 250, or 500 μg/mL of AA added to the culture medium every 3 days for up to 10 days, in the presence or absence of the iron chelator SIH (10 μM) as indicated in each particular experiment. Untreated cells were used as control. These experimental conditions were empirically established by unpublished previous tests. To evaluate the antioxidant potential of AA, AA-treated cultures were exposed to a bolus dose of H2O2 (0, 500, 1,000, and 1,500 μM). In some instances, the lysosomal iron chelator DFO (500 μg/mL) was added for 2 hours prior to H2O2 treatment.

Cell viability and cytotoxicity

Cell viability and cytotoxicity were quantified with a cytotoxicity assay (MultiTox-Fluor Multiplex Cytotoxicity Assay; Promega) that simultaneously measures the relative number of live and dead cells in cell populations. Assays were conducted in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

Western blot analysis

Cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing Halt Protease Inhibitor Cocktail and Halt Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Pierce). Protein concentration was determined with a protein assay kit (Micro BCA; Pierce). Protein samples (1–20 μg) were separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (15% in the case of LC3 immunoblots) and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk and incubated overnight with anti-ferritin L (SC-14422, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-LC3B (3868S, Cell Signaling), anti-cathepsin B (ab58802–100, Abcam), and anti-tubulin (T5293, Sigma-Aldrich). Bands were detected by incubation with a secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase and chemiluminescence substrate (ECL Plus; GE Healthcare). Blots were scanned and densitometric analysis was calculated using Image J.

Quantification of intracellular reactive oxygen species production

Intracellular reactive oxygen species (iROS) production was quantified using the cell-permeant ROS indicator 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2 DCFDA; Invitrogen). Briefly, cells (1×106) were trypsinized and incubated in 1 mL PBS containing 20 μM H2DCFDA for 30 minutes. After this loading period, cells were washed, and the mean green fluorescence of 10,000 cells was immediately recorded and quantified by flow cytometry (FL-1 channel; CellQuest software; BD Biosciences). Nonstained control cells were included to evaluate baseline fluorescence.

Measurement of intracellular labile iron pool

Levels of the cytosolic chelatable iron pool were assayed using calcein-AM, a fluorescent iron-sensitive probe.16 For this, cells were washed and incubated with 0.15 M calcein-AM for 10 minutes at 37°C in PBS containing 1 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.3. After calcein loading, cells were trypsinized, washed, and resuspended in this buffer without calcein-AM. Calcein fluorescence was monitored in a fluorescence spectrophotometer (excitation, 488 nm; emission, 518 nm).

Assessment of lysosomal enzyme activity

Cells grown in a 24-well plate were washed in PBS and lysated for 30 minutes at 4°C with shaking in 100 μL of 50 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.5), 0.1 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.2% Triton X-100. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation and immediately used for determination of proteolytic activity. For this, 1 μL of cell lysates was incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes in lysis buffer (100 μL) in the presence of the appropriate fluorogenic substrate. The following cathepsin substrates were used in this study: z-FR-AMC (20 μM; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, SC-3136), z-RR-AMC (20 μM, Enzo Life Sciences, P-137), z-VVR-AMC (20 μM, Enzo Life Sciences, P-199), z-GPR-AMC (20 μM, Enzo Life Sciences, P-142), and Cathepsin D and E substrate (10 μM, Enzo Life Sciences, P-145). The 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (AMC) released as a result of proteolytic activity was quantified with a microtiter plate reader (exc: 380 nm; em: 440 nm), and normalized by total protein content. The AMC released as a result of cathepsin D (CTSD) and cathepsin E (CTSE) proteolytic activity was read at 340 nm (exc) and 420 nm (em).

Monitoring lysosomal proteolytic degradation

Lysosomal proteolytic degradation was quantified using DQ-BSA (Invitrogen), a self-quenched red BODIPY dye conjugated to BSA, which is uptaken by endocytosis and delivered to amphisomes and autolysosomes, whereby it is enzymatically degraded by lysosomal proteases rendering fluorescence.17 For this, DQ-BSA (10 μg/mL) was added to the culture media for 24 hours. Cells were then washed, trypsinized, and resuspended in PBS. DQ-BSA fluorescence was monitored by confocal microscopy and quantified by flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis

All experimental procedures were repeated at least three times in independent experiments using different cell lines. The percentage of increase of the experimental conditions compared with the control was calculated and averaged. Data are represented as mean±SD. Statistical significance was calculated using Student's t-test for 2-group comparisons and 1-way or 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni's post-hoc comparisons tests for multiple group comparisons (Prism; GraphPad, San Diego, CA). P<5% was considered statistically significant.

Results

Dual effect of AA on H2O2-induced TM cell damage

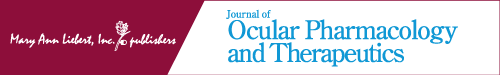

To evaluate the antioxidant effect of AA on TM cells, we supplemented confluent cultures of porcine TM cells with 100, 250, or 500 μg/mL of the vitamin added to the culture medium every 3 days for up to 10 days. Cultures were then exposed to a bolus dose of H2O2 (500, 1,000, and 1,500 μM). Cell viability was assayed at 3 hours post-treatment. As shown in Fig. 1A, AA alone did not have any significant effect on cell viability. In a couple of instances, we observed high levels of cytotoxicity (>80% cells dead) with 500 μg/mL of AA in a particular cell line, which were excluded from this analysis. In the presence of H2O2, AA demonstrated a dual effect depending on the dose used. At 100 and 250 μg/mL, the vitamin exerted a protective effect against H2O2-induced cell death; however, at the highest dose, AA acted as cytotoxic significantly increasing the H2O2-induced cell death.

FIG. 1.

Effect of ascorbic acid (AA) on H2O2-induced cytotoxicity. (A) Primary cultures of porcine trabecular meshwork (TM) cells were cultured for 10 days in the presence of increasing concentrations of AA (0, 100, 250, and 500 μg/mL), and then exposed to a bolus dose of H2O2 (0, 500, 1,000, and 1,500 μM). Cell viability was assayed at 3 hours. (B) Experiments were performed as in (A), but cells were incubated for 2 hours with the iron chelator desferoxamine (DFO) (500 μg/mL) prior to H2O2 treatment. Results are expressed as percentage of alive cells. Bars with asterisks compare AA-treated versus untreated cultures, with two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni's post-hoc comparisons tests. Bars with crosshatch symbols compare DFO-treated versus DFO-nontreated cultures, t-test. *,#P<0.05; ##P<0.01; ***,###P<0.001; n=4.

The pro-oxidant effect of AA is mediated by iron-catalyzed Fenton reactions

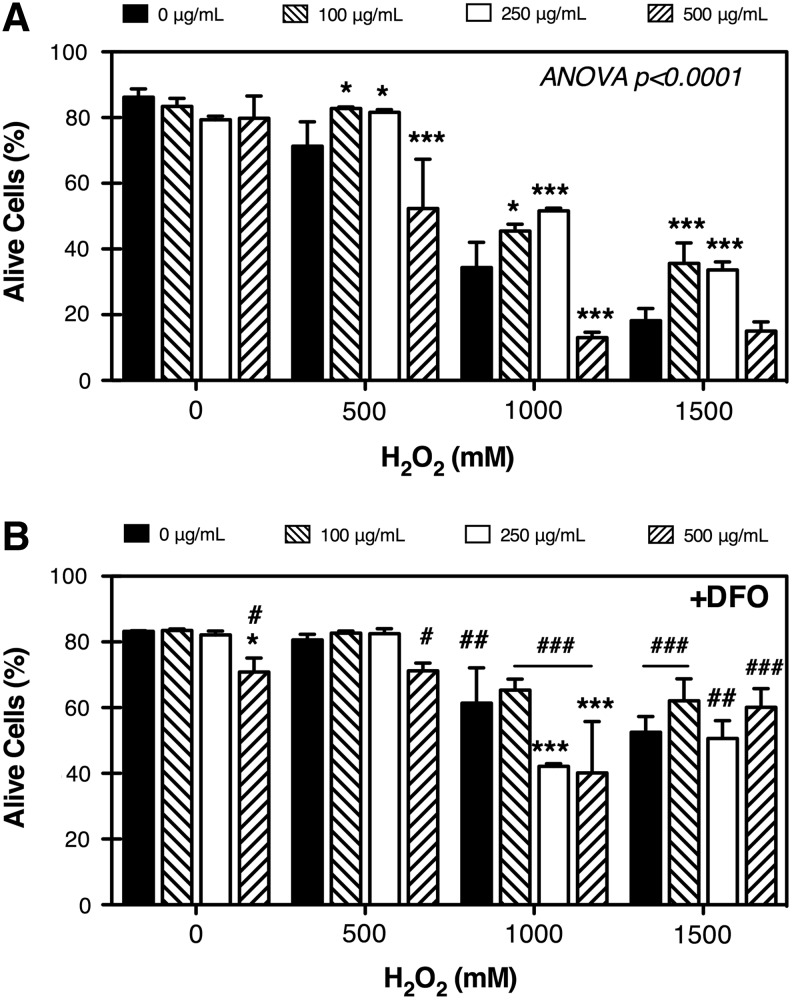

Generally, ascorbate is regarded as a reducing agent; it is able to serve as an antioxidant in free-radical-mediated oxidation processes. However, as a reducing agent it is also able to reduce redox-active metals such as copper and iron, thereby increasing the pro-oxidant chemistry of these metals (Fig. 2A).18,19 Our laboratory has previously shown a key role of lysosomal iron in the molecular mechanisms accompanying H2O2-induced cell death in TM cells.20 To evaluate whether redox-active iron might be involved in the pro-oxidant effect of AA on TM cells, we incubated primary cultures of TM cells supplemented with AA for 10 days, with the lysosomal iron chelator DFO (500 μg/mL) for 2 hours prior to H2O2 treatment. As observed in Fig. 1B, iron chelation suppressed the cytotoxic effect of high-dose AA with H2O2.

FIG. 2.

(A) The pro-oxidant chemistry of AA. (B) Representative Western blot showing protein levels of ferritin light chain (FTL) in trabecular meshwork (TM) cells supplemented for 10 days with AA. TUBB, beta-tubulin. (C) Free chelatable iron content in TM cells treated for 10 days with AA as quantified using the calcein-acetoxymethyl ester (AM) assay. Note that quenched calcein relative fluorescence units (RFU) reflect increased iron content. (D) Basal intracellular reactive oxygen species (iROS) levels in TM cells treated for 10 days with AA expressed as percentage of nontreated cultures. *P<0.05, ***P<0.01, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni's post-hoc comparisons tests, n=4.

To prevent iron from participating in oxidizing reactions, cells keep intracellular iron bound to ferritin, a high-affinity iron-storage protein, composed of ferritin heavy chain and ferritin light chain (FTL), which expression is controlled by free-iron content itself.21 We indirectly monitored free cellular iron content (labile iron pool, LIP), by analyzing the protein levels of ferritin. Western-blot analysis showed a decrease in the protein levels of FTL with low AA concentrations compared to untreated cultures. In contrast, supplementation of TM cells with 500 μg/mL of AA caused a significant increase in the levels of ferritin (Fig. 2B). We additionally quantified the LIP using the calcein-AM assay.16 As observed in Fig. 2C, calcein-AM fluorescence was significantly quenched in cells treated with 500 μg/mL of AA, suggesting increased free cellular iron content in these cultures. Moreover, while 100 μg/mL lowered the basal levels of iROS, supplementation with 500 μg/mL of AA led to higher basal iROS formation (Fig. 2D). Treatment with 250 μg/mL of AA also decreased iROS production, although no statistical significance was reached in this case.

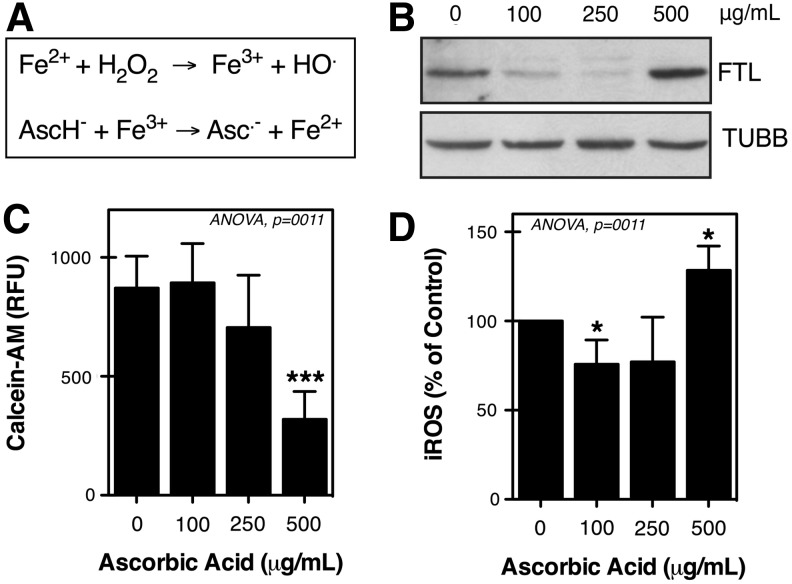

Pharmacological concentrations of AA activates the autophagic-lysosomal pathway in TM cells

Some recent studies have suggested autophagy to play a role in ascorbate-induced cell death, in particular in some cancer cell types.3,22–26 To investigate induction of autophagy in TM cells with AA, we monitored by Western-blot analysis the lipidation of the autophagosome marker LC3B-I to LC3B-II.27 A dose-dependent increase in LC3B-II levels was found in TM primary cultures supplemented with AA, reaching a peak at 250 μg/mL and returning to almost basal levels at 500 μg/mL (Fig. 3A, B). Further increase was observed in the presence of the lysosomal basifying agent chloroquine, indicating that the higher LC3B-II levels in the treated cultures primarily results from induction of autophagy rather than decreased lysosomal degradation (Fig. 3C). Supplementation of AA together with the membrane permeable iron chelator SIH (10 μM) completely blocked the increase in LC3B-II levels (Fig. 3A and B), suggesting a role of free chelatable iron in the induction of autophagy by AA in TM cells.

FIG. 3.

(A) Protein expression levels of LC3-I and LC3-II in TM cells treated for 10 days with increasing concentrations of AA in the absence or presence of the iron chelator salicylaldehyde isonicotinoyl hydrazone (SIH) (10 μM). (B) Normalized relative protein levels of LC3B-II calculated from densitometric analysis of the blots. (C) Autophagic flux as evaluated by monitoring expression levels of LC3-I and LC3-II in TM cells incubated for 10 days with AA (250 μg/mL) followed by a 3-hour treatment with chloroquine (CQ) (30 nM). Blots are representative from 3 different experiments. *,#P<0.05, **,##P<0.01, ###P<0.001, one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post-hoc comparisons tests, n=3. ACTB, β-actin.

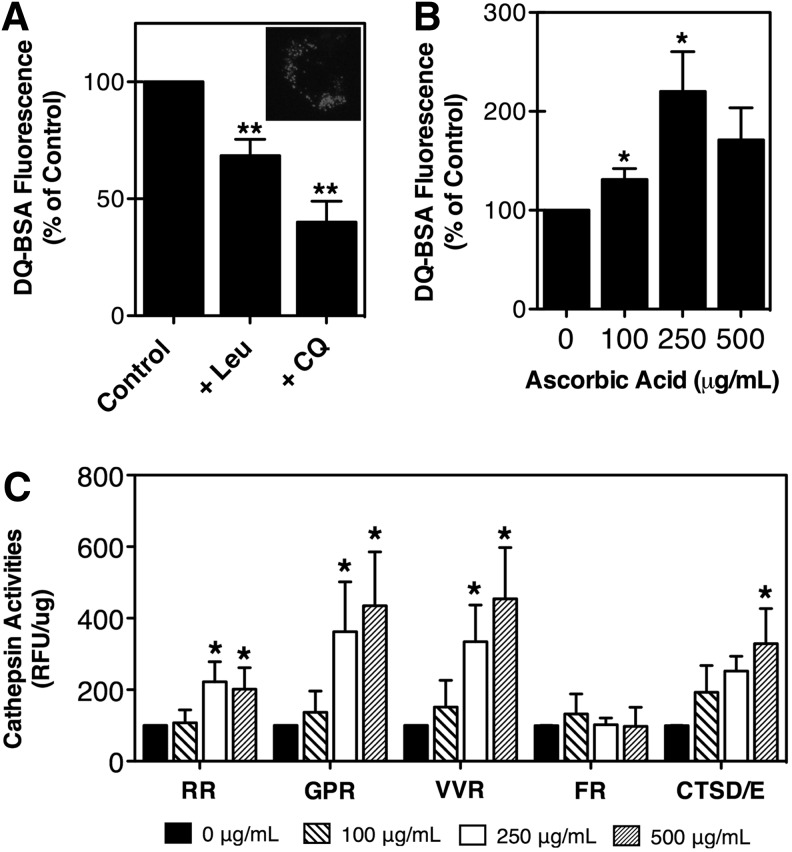

We next tested whether the induction of autophagy with the vitamin was translated into increased autophagic lysosomal degradative capacity. For this, TM cells supplemented for 10 days with increasing concentrations of AA were exposed for 16 hours to DQ-BSA (10 μg/mL), a nonfluorescence derivative of BSA that becomes fluorescent following enzymatic degradation by lysosomal proteases in amphisomes and autolysosomes.17 Cell cultures treated with chloroquine (30 nM) or leupeptin (10 μM), a lysosomal protease inhibitor, were used as positive controls. As expected, a red punctate staining in the perinuclear region was observed in TM cells exposed to the dye (Fig. 4A, inset), the intensity of which diminished in the presence of leupeptin or chloroquine (Fig. 4A). In contrast, supplementation of TM cells with AA resulted in a dose-dependent elevation of DQ-BSA fluorescence, which peaked with 250 μg/mL of the vitamin (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

(A) Lysosomal proteolysis in TM cells in the absence or presence of Leu (10 μM) or CQ (30 nM). Inset: Representative confocal image showing DQ-BSA fluorescence in the perinuclear region. (B) Lysosomal proteolysis in TM cells treated for 10 days with AA quantified using DQ-BSA (10 μg/mL). (C) Lysosomal enzyme activity determined in cell lysates of TM cells supplemented for 10 days with AA using the following fluorogenic substrates: Z-FR-AMC, Z-RR-AMC, Z-GPR-AMC, Z-VVR-AMC, and CTSD/E. Relative fluorescence units (RFU) were normalized by total proteins. Graphs represent the percentage of increase compared with untreated cells. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, one-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni's post-hoc comparisons tests, n=4.

Based on these results, we quantified the activity of several lysosomal cathepsin enzymes using fluorogenic substrates. As shown in Fig. 4C, culturing TM cells in the presence of AA caused a very consistent, significant, and dose-dependent increase in the activity of the cysteine (CTSB, RR-AMC; cathepsin K, GPR-AMC; cathepsin S, VVR-AMC) and aspartyl (CTSD/E) proteases. The activity of serine proteases, which include cathepsins, kalikrein, and plasmin (FR-AMC), was not significantly altered by the vitamin.

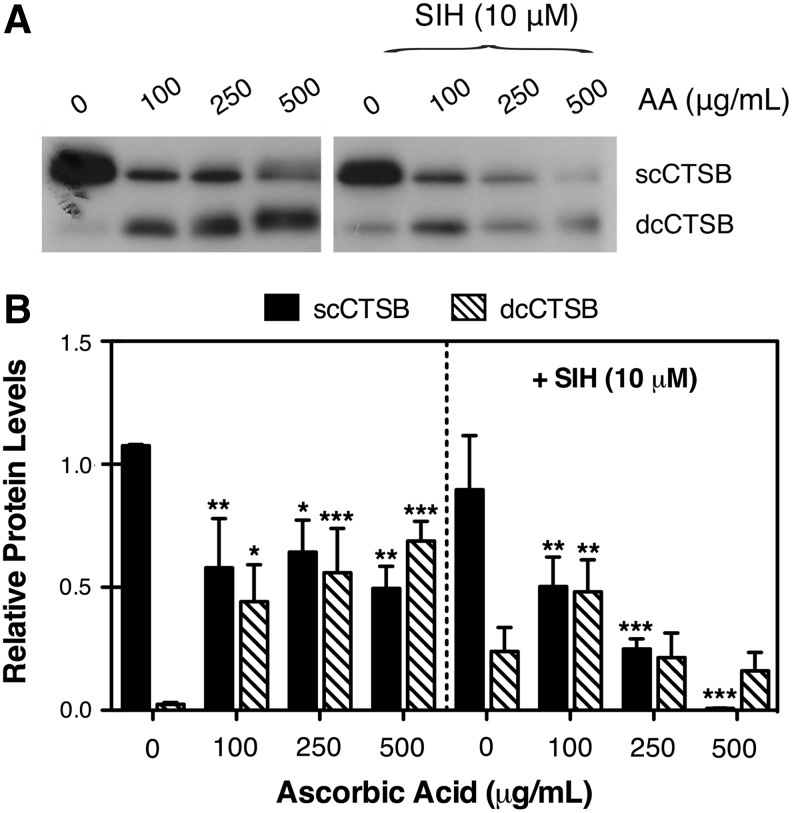

Cathepsins are synthesized as inactive precursor, which are activated by proteolytic removal of the propeptide to yield the mature single-chain form. This mature form is further cleaved in the lysosomes rendering the double-chain (dc) form.28 Protein levels and proteolytic activation of CTSB were monitored by Western-blot analysis. As observed in Fig. 5A and B, CTSB was predominantly found in its single-chain form (scCTSB) in control cultures. However, a dose-dependent increase in dcCTSB protein levels was observed in the AA-treated cells, concomitant with a decrease in scCTSB. Similar results, in terms of lower scCTSB content in AA-treated cells, were observed in the presence of the iron chelator SIH, although in this case, such decrease in scCTSB was not accompanied by elevated dcCTSB levels.

FIG. 5.

(A) Protein expression levels of cathepsin B (CTSB) in trabecular meshwork cells treated for 10 days with increasing concentrations of ascorbic acid in the absence or presence of the iron chelator SIH (10 μM). (B) Normalized relative protein levels of single-chain form (sc)CTSB/double-chain form (dc)CTSB calculated from densitometric analysis of the blots LC3B-II calculated from densitometric analysis of the blots. Blots are representative from 3 different experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, one-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni's post-hoc comparisons tests, n=3.

Discussion

Here we reported for the first time 2 novel and different roles of AA in TM cell metabolism. First, we showed a dose-dependent dual effect of AA against oxidative insult, mediated by modulation of iron homeostasis and iROS formation. Second, our results demonstrate the activation of the autophagic lysosomal pathway and increased lysosomal degradation with AA in TM cells. Furthermore, our data indicate that this latter effect results from an, until now, unknown ability of AA to enhance proteolytic activation of lysosomal enzymes.

Ascorbic acid is generally regarded as a protective antioxidant due at least in part to its direct oxyradical-scavenging properties. Despite this antioxidant potential, ascorbate, the most abundant form of AA at physiological conditions, can function as a pro-oxidant as it participates in the generation of ROS through its autoxidation (Asc+O2→dehydroAsc+H2O2), or reduction of ferric iron (Fe3+) to ferrous iron (Fe2+), which in turn reacts with H2O2 to generate hydroxyl radical (Fig. 2A).3 Autoxidation of ascorbate is also greatly accelerated in the presence of iron or other divalent metals, such as copper. Both ascorbate and dehydroascorbate are transported intracelullarly via Na+-dependent and Na+-independent transporters, respectively. Our data show that, in the presence of H2O2, AA can act both as a pro-oxidant or an anti-oxidant in TM cells, depending on the concentration used. The pro-oxidant effect of AA with H2O2 was mostly abolished in the presence of an iron chelator. The lower doses of AA used in this study fall within the physiological range. Although it widely varies among individuals, the typical concentration of AA in the AH is 150–250 μg/mL. At this level, AA would be expected to function as an antioxidant. However, the prooxidant effects of ascorbate might be important in vivo, depending on the availability of catalytic metal ions. Elevated levels of catalytic metal ions have been demonstrated during aging and in chronic inflammatory diseases.29,30 While there is no direct evidence of changes in iron content with age or in disease in the outflow pathway, prior data from our laboratory have shown changes in expression of the iron homeostasis gene in the glaucomatous TM cells as well as in the outflow pathway tissue.20 Moreover, a recent cross-sectional study has shown an association between glaucoma prevalence and supplementary iron intake.31

To prevent iron from participating in oxidizing reactions, cells keep intracellular iron in this “inactive” ferrous state, bound to ferritin, a high-affinity iron-storage protein, the expression of which is controlled by free-iron content itself.21 Interestingly, our experiments show that AA differentially modulates the amount of ferritin in TM cells based on the concentration used. Moreover, such differential effect was correlated with its role as either an antioxidant or as a pro-oxidant. Thus, TM cultures supplemented with concentrations of AA that protected against H2O2 insult showed lower levels of ferritin, as well as diminished basal iROS formation. In contrast, cultures supplemented with 500 μg/mL, a dose that exacerbated the cytotoxic effect of H2O2, showed an increase in ferritin levels concomitant with elevated LIP and basal iROS levels. The exact mechanisms by which AA alters the expression of ferritin in TM cells are not known. Incubation of lens epithelial cells with AA induces ferritin synthesis at the translational level.32 However, in other cell types, AA treatment leads to high ferritin content by delaying its degradation through the autophagic–lysosomal pathway.33 It has been suggested that by retarding ferritin degradation, ascorbate promotes oxidative processes, given its ability to reduce and therefore mobilize iron from the crystalline core. As explained earlier, this bioavailable iron can in turn participate in Fenton's reaction. This is in agreement with our own results showing increased FTL, LIP, and iROS content with high AA concentrations. Why diminished FTL levels were found in TM cells treated with lower AA doses, and whether this decrease in FTL is associated with its antioxidant role, are not currently known.

Autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved mechanism that allows for the degradation of long-lived proteins and organelles within lysosomes by lysosomal hydrolases. An emerging role of autophagy as a survival pathway against different types of stress, including oxidative stress, has been reported in the literature.34 Indeed, our laboratory has recently demonstrated activation of autophagy in response to chronic oxidative stress in TM cells.35 Interestingly, the results presented here clearly indicate the induction of autophagy with AA supplementation. Furthermore, higher LC3-II levels, and therefore a greater level of induction, were observed with those concentrations in which AA behaves as an antioxidant. Based on this, it is very tempting to speculate that activation of autophagy might be, at least in part, one of the mechanisms by which AA protects against oxidative stress. Moreover, since cellular ferritin is known to be degraded through the autophagic lysosomal pathway,36 it is plausible that the observed decrease in FTL with low AA doses results from the induction of autophagy. Excessive ferritin degradation, however, could lead to intralysosomal accumulation of free iron with subsequent lysosomal membrane permeabilization and cell death.20 Since iron content controls the expression of ferritin, lysosomal permeabilization and leakage of lysosomal iron into the cytosol could additionally explain the higher levels of FTL with high AA doses by inducing ferritin synthesis at the translational level.

The molecular events that lead to the activation of autophagy with ascorbate are not clear. The latest studies have indicated that generation of iROS is required for proper activation of autophagy.37–39 Ascorbic acid is capable of generating iROS directly through its autoxidation, or indirectly by increasing iron availability, as described earlier. However, we found lower iROS basal levels with those concentrations of AA that greatly activated autophagy. One potential explanation is that for detection of iROS, we used H2DCFDA, which primarily detects H2O2, but poorly detects superoxide radical, the major ROS regulating autophagy.39 Additional studies will be required to test whether this is the case or other molecular events are involved.

One of the most unexpected findings of our study was the dose-dependent increase in lysosomal degradation and lysosomal cathepsin activities in the AA-supplemented cultures. Furthermore, we found that, at least for CTSB, such increase in lysosomal activity correlated with the conversion of the mature form single-chain to double-chain, the most biologically active form of the enzyme. Although accelerated lysosomal degradation with physiological concentrations of AA mediated by intralysosomal pH stabilization has been described in glial cells,40 this is the first time that proteolytic cleavage of lysosomal cathepsins with AA supplementation has been reported. Unfortunately, we were unable to confirm this result in other cathepsins, other than CTSB, since the antibodies available in our laboratory do not recognize the double-chain form.

The pathophysiological relevance of these studies is tremendous. The lysosomal compartment is responsible for the degradation of long-lived proteins, as well as extracellular and membrane-bound proteins uptaken by phagocytosis and endocytosis, respectively. Lysosomal proteolysis can contribute to as much as 90% of the protein degradation. Most importantly, lysosomes constitute the only cellular proteolytic system capable of degrading worn-out and/or damaged organelles. Increased protein breakdown may be desirable in all these conditions in which abnormal or damaged proteins accumulate inside cells (e.g., during aging or under oxidative stress conditions). Interestingly, our laboratory has reported diminished autophagic degradation capacity and impaired proteolytic activation of cathepsins, in particular CTSB, in TM cells subjected to chronic oxidative stress.35 Ongoing experiments are being conducted to determine whether supplementation of the TM cell cultures with AA could prevent or revert such an impaired autophagic capacity.

Impaired lysosomal function has been suggested in the pathogenesis of POAG,15,41 indirectly supported by the finding of increased abnormal β-galactosidase activity in the glaucomatous outflow pathway,42 and more directly supported by the observed diminished autophagic degradative capacity in glaucomatous TM cells in vitro (Porter K, et al. Association for Research in Vision & Ophthalmology; Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci., 2013; Abstract 3548). Poor nutritional status and low levels of antioxidants, including vitamin C, are common among the elderly population and have been associated with several neurodegenerative diseases. Similarly, a reduction of the levels of vitamin C in plasma as well as in the AH of patients with POAG and secondary glaucoma has also been documented by several investigators.10–12 Additional evidence of the potential relevance of AA in outflow pathway physiology and pathophysiology comes from the observed IOP-lowering effect of AA,4–6 and from the recent work by Zanon-Moreno et al.14 reporting an association between a polymorphism in the AA transporter SLC23A2 with lower plasma concentrations of AA and with higher risk of POAG. Based on the data obtained here, it is plausible that such diminished levels of ascorbate or deficient AA cellular uptake can compromise lysosomal degradation in the outflow pathway cells with aging and contribute to the pathogenesis of glaucoma. Restoration of physiological levels of vitamin C inside the cells might improve their ability to degrade proteins within the lysosomal compartment and recover tissue function.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Eye Institute of Health (R01EY020491, P30EY005722), Brightfocus (G2012022), Alcon Foundation Young Investigator Award, and Research to Prevent Blindness.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Reiss G.R., Werness P.G., Zollman P.E., and Brubaker R.F.Ascorbic acid levels in the aqueous humor of nocturnal and diurnal mammals. Arch. Ophthalmol. 104:753–755, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Erb C., Nau-Staudt K., Flammer J., and Nau W.Ascorbic acid as a free radical scavenger in porcine and bovine aqueous humour. Ophthalmic Res. 36:38–42, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Du J., Cullen J.J., and Buettner G.R.Ascorbic acid: chemistry, biology and the treatment of cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1826:443–457, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linner E.The pressure lowering effect of ascorbic acid in ocular hypertension. Acta. Ophthalmol. 47:685–689, 1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyd H.H.Eye pressure lowering effect of vitamin C. J. Orthomolec. Med. 10:165–168, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esilä R., Tenhunen T., and Tuovinen E.The effect of ascorbic acid on the intraocular pressure and the aqueous humour of the rabbit eye. Acta. Ophthalmol. 44:631–636, 1966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou L., Higginbotham E.J., and Yue B.Y.Effects of ascorbic acid on levels of fibronectin, laminin and collagen type 1 in bovine trabecular meshwork in organ culture. Curr. Eye Res. 17:211–217, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sawaguchi S., Yue B.Y., Chang I.L., Wong F., and Higginbotham E.J.Ascorbic acid modulates collagen type I gene expression by cells from an eye tissue–trabecular meshwork. Cell. Mol. Biol. (Noisy-le-grand). 38:587–604, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schachtschabel D.O., and Binninger E.Stimulatory effects of ascorbic acid on hyaluronic acid synthesis of in vitro cultured normal and glaucomatous trabecular meshwork cells of the human eye. Z. Gerontol. 26:243–246, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferreira S.M., Lerner S.F., Brunzini R., Evelson P.A., and Llesuy S.F.Antioxidant status in the aqueous humour of patients with glaucoma associated with exfoliation syndrome. Eye (Lond). 23:1691–1697, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koliakos G.G., Konstas A.G.P., Schlötzer-Schrehardt U., Bufidis T., Georgiadis N., and Ringvold A.Ascorbic acid concentration is reduced in the aqueous humor of patients with exfoliation syndrome. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 134:879–883, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leite M.T., Prata T.S., Kera C.Z., Miranda D.V., de Moraes Barros S.B., and Melo L.A.Ascorbic acid concentration is reduced in the secondary aqueous humour of glaucomatous patients. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 37:402–406, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuki K., Murat D., Kimura I., Ohtake Y., and Tsubota K.Reduced-serum vitamin C and increased uric acid levels in normal-tension glaucoma. Graefes. Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 248:243–248, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zanon-Moreno V., Marco-Ventura P., Lleo-Perez A., et al. Oxidative stress in primary open-angle glaucoma. J. Glaucoma. 17:263–268, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liton P.B., Lin Y., Luna C., Li G., Gonzalez P., and Epstein D.L.Cultured porcine trabecular meshwork cells display altered lysosomal function when subjected to chronic oxidative stress. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 49:3961–3969, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cabantchik Z.I., Glickstein H., Milgram P., and Breuer W.A fluorescence assay for assessing chelation of intracellular iron in a membrane model system and in mammalian cells. Anal. Biochem. 233:221–227, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vázquez C.L., and Colombo M.I.Assays to assess autophagy induction and fusion of autophagic vacuoles with a degradative compartment, using monodansylcadaverine (MDC) and DQ-BSA. Meth. Enzymol. 452:85–95, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buettner G.R., and Jurkiewicz B.A.Catalytic metals, ascorbate and free radicals: combinations to avoid. Radiat. Res. 145:532–541, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duarte T.L., and Jones G.D.D.Vitamin C modulation of H2O2-induced damage and iron homeostasis in human cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 43:1165–1175, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin Y., Epstein D.L, and Liton P.B.Intralysosomal iron induces lysosomal membrane permeabilization and cathepsin D-mediated cell death in trabecular meshwork cells exposed to oxidative stress. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 51:6483–6495, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salahudeen A.A., and Bruick R.K.Maintaining mammalian iron and oxygen homeostasis: sensors, regulation, and cross-talk. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1177:30–38, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Du J., Martin S.M., Levine M., et al. Mechanisms of ascorbate-induced cytotoxicity in pancreatic cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 16:509–520, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cullen J.J.Ascorbate induces autophagy in pancreatic cancer. Autophagy. 6:421–422, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheung F.W.K., Che C.T., Sakagami H., Kochi M., and Liu W.K.Sodium 5,6-benzylidene-L-ascorbate induces oxidative stress, autophagy, and growth arrest in human colon cancer HT-29 cells. J. Cell Biochem. 111:412–424, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen P., Yu J., Chalmers B., et al. Pharmacological ascorbate induces cytotoxicity in prostate cancer cells through ATP depletion and induction of autophagy. Anticancer Drugs. 23:437–444, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hong S.-W., Lee S.-H., Moon J.-H., et al. SVCT-2 in breast cancer acts as an indicator for L-ascorbate treatment. Oncogene. 32:1508–1517, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klionsky D.J., Abdalla F.C., Abeliovich H., et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy. 8:445–544, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nishimura Y., Tsuji H., Kato K., Sato H., Amano J., and Himeno M.Biochemical properties and intracellular processing of lysosomal cathepsins B and H. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 18:829–836, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacKenzie E.L., Iwasaki K., and Tsuji Y.Intracellular iron transport and storage: from molecular mechanisms to health implications. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 10:997–1030, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Altamura S., and Muckenthaler M.U.Iron toxicity in diseases of aging: Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease and atherosclerosis. J. Alzheimers Dis. 16:879–895, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang S.Y., Singh K., and Lin S.C.The association between glaucoma prevalence and supplementation with the oxidants calcium and iron. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 53:725–731, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goralska M., Harned J., Grimes A.M., Fleisher L.N., and McGahan M.C.Mechanisms by which ascorbic acid increases ferritin levels in cultured lens epithelial cells. Exp. Eye Res. 64:413–421, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bridges K.R.Ascorbic acid inhibits lysosomal autophagy of ferritin. J. Biol. Chem. 262:14773–14778, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moore M.N.Autophagy as a second level protective process in conferring resistance to environmentally-induced oxidative stress. Autophagy. 4:254–256, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Porter K., Nallathambi J., Lin Y., and Liton PB.Lysosomal basification and decreased autophagic flux in oxidatively stressed trabecular meshwork cells: implications for glaucoma pathogenesis. Autophagy. 9:581–594, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kidane T.Z., Sauble E., and Linder M.C.Release of iron from ferritin requires lysosomal activity. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 291:C445–C455, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang J., Lam G.Y., and Brumell J.H.Autophagy signaling through reactive oxygen species. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 14:2215–2231, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scherz-Shouval R., Shvets E., Fass E., Shorer H., Gil L., and Elazar Z.Reactive oxygen species are essential for autophagy and specifically regulate the activity of Atg4. EMBO J. 26:1749–60, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen Y., Azad M.B., and Gibson S.B.Superoxide is the major reactive oxygen species regulating autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 16:1040–1052, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martin A., Joseph J.A., and Cuervo A.M.Stimulatory effect of vitamin C on autophagy in glial cells. J. Neurochem. 82:538–549, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liton P.B., Lin Y., Gonzalez P., and Epstein DL.Potential role of lysosomal dysfunction in the pathogenesis of primary open angle glaucoma. Autophagy. 5:122–124, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liton P.B., Challa P., Stinnett S, Luna C., Epstein D.L., and Gonzalez P.Cellular senescence in the glaucomatous outflow pathway. Exp. Gerontol. 40:745–748, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]