Abstract

Movement disorders presenting in childhood are often complex and a heterogenous group of difficulties which can be a minefield for the primary care doctor.

The recent activities of the European Society for the Study of Tourette Syndrome (ESSTS) have included publication of European clinical guidelines for Tourette syndrome and other Tic disorders aimed at guiding paediatricians and psychiatrists in managing these children. This paper aims to summarise the key points for primary care teams and impart important facts and general information on related childhood movement disorders in early development.

Keywords: childhood, movement, Tourette, stereotypies, tics

INTRODUCTION

Movement disorders presenting in childhood are often a complex and heterogeneous group of difficulties which can be a minefield for the primary care doctor.

Families attending for diagnosis, explanation and reassurance of their child's unusual movements expect recognition and concise information from their healthcare provider. Making appropriate referrals and working alongside specialists to ensure accurate monitoring and delivery of treatment are also important roles for the primary care practitioner.

Box 1: Key Messages

Not all brief motor episodes are tics

Tics are neurological and do have defining features i.e. suggestible, suppressible, increase with stress and associated premonitory urge.

Motor Stereotypies are different and diagnosis is useful to access information for management.

Most Early Movement difficulties and Tic disorders improve with time

Consider behaviour and learning and the co-morbid conditions when assessing a child with unusual movements

The recent activities of the European Society for the Study of Tourette Syndrome (ESSTS) have included publication of European clinical guidelines for Tourette syndrome and other Tic disorders aimed at guiding paediatricians and psychiatrists in managing these children. This paper aims to summarise the key points for primary care teams and impart important facts on related childhood movement disorders.

This document will discuss the following conditions:

Motor Stereotypies

Chronic tic disorders and Tourette Syndrome

Compulsions

Paroxsymal Dyskinesias

Functional (psychogenic) movement disorders

Myoclonus dystonia syndrome

Akathisia

Paediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorder Associated with Streptococcal infection (PANDAS)

Infantile gratification syndrome

Shuddering Attacks

Hyperekplexia

CHILDHOOD MOTOR STEREOTYPIES

Motor Stereotypies are likely to begin in the early stages of life. A movement becomes a sterotypy when, according to The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-IV-TR) it is a repetitive, non functional motor disorder which interferes with normal activities or results in injury1. In clinical practice the definition is broader as usually children report enjoyment or are unaware of their actions.

Childhood Motor Stereotypies often consist of hand flapping or twisting, body rocking, head banging, face or mouth stretching sometimes appearing as a marked grimace. It is imperative to establish the presence of any co-existing developmental disorder. A detailed family history is also important, 25% children have an affected relative2 and there is also likely to be a family history of obsessive tendencies often in the form of counting rituals.

Stereotypies can present in those with normal development and without neurological disorder. Motor stereotypies are commonly seen in children with autism spectrum disorder but can also be seen in those with sensory impairment, social isolation and or learning disability.

In neurotypical children they are known as Primary Motor Stereotypies, they typically remain stable or regress with age as children become more aware of their social surroundings. There are several common types of movements including rocking, head banging and finger drumming. More complex themes include hand and arm flapping, waving and arm shaking. A rare presentation includes a rhythmical movement of the head and neck which can be up and down, side to side or shoulder to shoulder best termed ‘head nodding stereotypy’.

Secondary Stereotypies is a term often used when there is an additional developmental delay or neurological disorder and these may persist over time. Examples of movements in this group include: the characteristic hand twisting movements seen in Rett syndrome or the atypical gazing at fingers or objects seen in autism spectrum disorders.

Fig 1.

Secondary stereotypy affecting arms and face Photo kindly reproduced with permission from parents and Tandem clinic Evelina Children's hospital, London

Stereotypies also present in neurometabolic disorders alongside other movements such as dystonia, myoclonus, chorea and tremor.

Box 2. Differential Diagnosis of Motor Stereotypies

Tic Disorder or Tourette syndrome

Compulsions

Paroxysmal Dyskinesias (PKD/PKND)

Seizures

Myoclonus

Dystonia

Hyperekplexia

Functional Movement Disorder

Cataplexy/Narcolepsy

The neurobiological aetiologies underpinning stereotypies is not fully understood. It is likely that similar mechanisms will be identified to those proposed for related disorders affecting the fronto-striatal pathways including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), Obsessive compulsive behaviours (OCB) and tic disorders. The cerebellum may also have a role and emerging work in this field is likely to inform future hypotheses.

Lesions of the basal ganglia have been implicated through case reports describing stereotypies present in those with damage to the putamen, orbitofrontal cortex and thalamus. Excess Dopamine in ascending pathways is a possible candidate in the mediation of stereotypies and the link with tic spectrum has been well recognised sporting the theory of overlapping mechanisms. An aetiological basis for stereotypies has also been proposed in the literature3. Due to the presence of stereotypies in neuro-developmentally normal children and the fact that some children appear to have a genetic predisposition to stereotypies it is suggestive a bio-psycho-social model is yet to be elucidated.

It is likely that advances in functional neuro-imaging, genetics and neuropathology studies will allow these movements to be further categorised into specific genetically defined neuro-developmental phenotypes.

Isolated stereotypies do not usually warrant pharmacological treatment. In such cases behavioural strategies are usually of benefit, although under the age of seven they can be difficult to implement as the child may enjoy some aspects of the movement. There are several strategies which can be used. However, response is variable, these methods work most successfully when the children are motivated to stop and are socially aware.

When there are co-existing conditions or severely restrictive, self-injurous behaviours medication may be warranted but management of an underlying, co-morbid condition should be carefully considered. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) have been trialled. In some children with ADHD who are managed with stimulants a reduction has been reported in co-existing stereotypies.

Stereotypies are differentiated from tic disorders but can also co-exist.

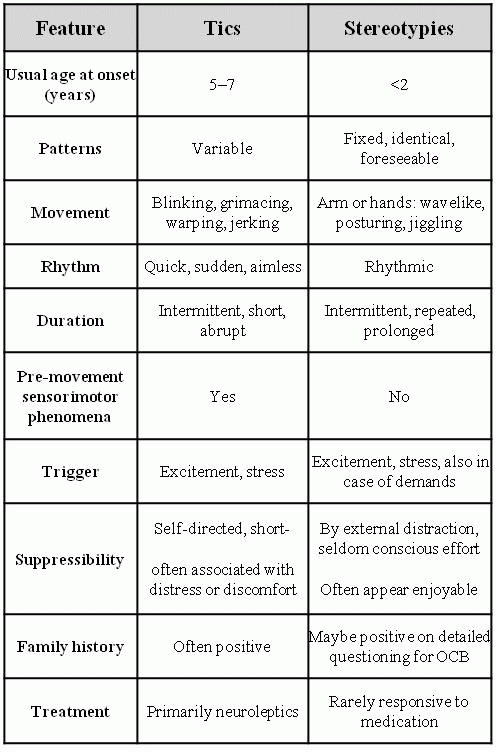

Fig 2.

Differentiating between tics and stereotypies Barry S, Baird G, Lascelles K, Bunton P, Hedderly T. Neuro-developmental Movement Disorders -An Update on Childhood Motor Stereotypies. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011; 53(11): 979-85

CHRONIC TIC DISORDER AND TOURETTE SYNDROME (TS)

Confusion exists amongst the lay public regarding tics and Tourette syndrome. Particularly the over-representation of coprolalia (vocal tic of expletives) in the media. The condition itself has fascinated clinicians and researchers over the decades.

The high variability of tics, the fact that many cases are mild and there is often spontaneous remission leads to misconception.

Throughout Europe there are specialist centres with a wealth of experience in diagnosis and management of Tic disorders and Tourette syndrome. The European Society for the Study of Tourette Syndrome (ESSTS) was formed to share this experience and they have now produced European Guidelines4, 5, 6, 7, 8 for use across Europe.

Tic disorders typically begin in childhood at around 4 to 5 years of age but often don't present until later at around 9 or 10 yrs. They are known to affect as many as 10% of children. Tics usually began as simple motor tics and in some progress to complex motor tics and phonic tics over a period of around 1-2 years9. Around 1% of children develops intrusive daily motor and phonic tics for over one year and therefore fulfils diagnostic criteria for TS. The most difficult period with maximum tic severity in this group is commonly at 8-12 years4. By age 18 yrs tics often wane and impairments due to the tics themselves have been documented to significantly reduce with either no or only mild tics remaining into adulthood. Unfortunately a small percentage of young people will not experience tic decline and may even go into adulthood experiencing further more debilitating tics. Some young people have associated mood disturbance or anxiety disorders such as OCB which can emerge or become more problematic in adulthood.

Motor Tics are defined as: sudden, rapid, non-rhythmic motor movements or vocalisations usually appearing in bouts whilst waxing and waning in frequency, intensity and type of tic.

Simple motor tics often involve the face, neck or shoulder muscles e.g eye blinking, mouth twitching or shoulder jerks

Complex motor tics have a repetitive or compulsive nature such as certain ways of touching an object or elaborate sequences of movement. They can include repetitive obscene movements (copropraxia) or mimicking others (echopraxia)

Phonic or Vocal tics are sounds elicited by the flow of air through the vocal cords, nose or mouth. Most common vocal tics are throat clearing, grunts, high pitched sounds or sniffing. Coprolalia (vocalisation of expletives) is the most well recognised vocal tic though this occurs in less than 20% of patients. There are other complex phonic tics such as repeating others (echolalia) and repeating oneself (palilalia)

Box 3. Key features of a tic

Key features of tics which are closely related:

Ability to suppress tics temporarily

Suppression may lead to discomfort or urge may precede the tic

Active participation is required in performing the tic

Often highly suggestible

The premonitory urge prior to performing the tic is increasingly recognised by children with tic disorders, usually by the age of 12. The presence of this urge aids in the differentiation of the movements from those present in hyperkinetic movement disorders.

Tourette Syndrome (TS) is when: tics are multiple, with motor tics and a phonic tic present at some point over a period of at least one year. They must have started before the age of 18, been present on a daily basis and not been related to a medical condition, medications or substance use.

Tourette syndrome is known to be under diagnosed meaning information and care given to patients is often inadequate. On average it takes 5 years from onset of tics to diagnosis10 this prolonged period often leads to psychosocial impairment and stigmatisation.

TS is thought to affect 0.3-1%4 of the population. Diagnosis is twice more likely in white non-Hispanic persons than Hispanic or black people. Males are affected more commonly than females with a ratio of around 3-4:15. There is a strong genetic component in Tic disorders and TS.

The pathophysiology of tic disorders and Tourette syndrome is thought to arise from the cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical circuits. The cerebellum may also have a role. MRI studies with differential techniques and electrophysiological investigations on neuronal inhibition have yielded exciting hypotheses.

Box 4. Taking a movement history

Age at onset of first movement

Site, course and progression of movements

Age at worst severity and frequency

Any debilitating or distressing features

Any physical consequences

Somatosensory phenomena e.g. Urges and suppression, suggestibility

Relation to infections or immune difficulties

Screen for co-morbid conditions

Consider differential diagnosis

Comorbidities are common (affecting around 80%) in those with tic disorders and TS. ADHD is present in many of the children, as are OCB'S and mood and sleep disorders. See box. Children with TS who develop obsessive compulsive symptoms may do so at a later stage and vigilance is recommended (usually after 10 years of age). When complex tics are present it can be difficult to delineate them from the compulsions of OCB, the key to this is demonstrating the cognitively driven, goal directed and anxiety relieving features of OCB behaviours.

ADHD symptoms are often present prior to tic onset and TS diagnosis. They may improve during adolescence but at a slower rate than tic behaviours. The presence of comorbidity predicts poorer psychosocial outcomes5. Female relatives of TS patient have elevated rates of OCB and it appears likely that OCB is an alternate expression for the TS phenotype11.

Box 5. Assessing Tourette syndrome

It is important to evaluate:

Tic or movement history – see key features

Descriptions or video recordings of tic behaviours

Full developmental history

Family history

Family functioning: parental coping styles, conflicts, social support, financial and housing situation

Drug, alcohol or other substance misuse

Screening for general psychopathology including self, parent led and teacher led reporting

OCB, ADHD, behaviour, mood, and sleep enquiry

Interestingly Autism spectrum is common in 1st degree relatives and more distant family members also suggesting a shared aetiology in some subgroups.

Investigations in Chronic Tic Disorders and TS

A full physical and neurological examination is needed to exclude progressive neurological disorders.

If typical tic or TS features are present without additional movement disorder then further investigations are not required. If atypical features such as adult onset, uncharacteristic deterioration or progression of symptoms are found then further detailed investigation is needed and must include EEG and neuro-imaging.

If there are unusual physical features, learning difficulties or autism spectrum present then referral to paediatrician, neurologist and clinical geneticist may be useful. Rare genetic and epigenetic factors are likely to account for these heterogeneous disorders and research continues to explore these factors.

Further details into the differential diagnosis for tics is beyond the scope of this article but interested readers will find a useful decision tree produced by ESSTS in the literature5.

Diagnosis of Tics and Tourette syndrome offers patients a level of understanding and the ability to explain their unusual behaviours to others.

Management of tics and TS

Treatment aims to diminish both tic severity and frequency. However, commencing treatment for tics must be a carefully balanced decision. Firstly, because subjective impairment does not equal objective tic severity. Secondly, due to the variation in tic intensity, fluctuations in tic frequency and high rate of comorbid conditions, monitoring response to treatment can be difficult. Often it is crucial to get conditions such as anxiety under control in a bid to reduce TS symptoms.

Following thorough psychoeducation, if problems still present the first line modality is behavioural and psychological intervention. Imparting a knowledge and understanding of tics increases tolerance of symptoms and reduces stress. Most evidence has been found for:

Habit reversal training

Exposure with Response Prevention Second line or ‘add-on’ therapies are:

Contingency management

Function based interventions

Relaxation training

Group work

New therapies are also being piloted. Full explanation of psychological therapies is beyond the scope of this article but interested readers can access further information in the European Guidelines9.

In the majority an acceptable pathway is education and reassurance followed by a period of watchful waiting. School liaison is useful to offer strategies and approaches for teachers.

Pharmacological and now even surgical treatment options are available but no cure exists.

Pharmacological options are used for symptomatic control but long term data is not available to address potential side effects, therefore drug therapy is reserved for severe cases.

Indications include:

Tics are causing pain or discomfort

Pain from performance of frequent or intense tics, is usually musculoskeletal or neuropathic in nature. Some tics may lead to injuries. Occasionally tics will subside in the presence of pain leading to self harm.

Tics leading to social stigmatisation

Particularly phonic or complex motor tics can lead to social isolation, bullying or difficulties in the classroom. Education of peers and teachers can be useful in this situation but drug suppression may be necessary.

Tics leading to psychological problems

As a result of negative reactions from peers and other members of society problems such as reactive depression, anxiety and social phobia can develop.

Tics causing functional impairment

The mechanical interference of tics is rare but tic suppression is tiring and can impact negatively on concentration and ability to complete homework. Phonic tics can impair pronunciation and ability to interact in the classroom.

As only a limited number of rigourous studies have taken place most centres use clinical experience to guide their choices. In the UK Clonidine is used most commonly as first line drug therapy. It is useful in coexisting behavioural disorders, sleep onset difficulties and in the presence of comorbid ADHD.

Risperidone and Aripiprazole are also helpful. Haloperidol and pimozide have both been examined in randomised double blind controlled trials but have been in more recent years over taken by Risperidone which has also passed rigorous trials and has an improved safety profile. Tiapride and sulpiride are recommended on broad clinical experience although more controlled studies are needed.

Risperidone has good results in coexisting OCB particularly when used alongside an SSRI.

If considering use of medication it is recommend that shared care occurs between the primary care practioner and a Tourette specialist service.

The Surgical option; Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) was first introduced early in the 21st century. At this time DBS was thought to be a promising treatment for severe TS. However large trials are still lacking and DBS in TS remains in its infancy.

It is currently only recommended for adult, treatment resistant, severely affected patients. tics should be present for 5 years and severe in nature for at least 1 year before DBS is considered. Much further work into DBS needs to be performed before guidelines for its use can be introduced.

COMPULSIONS

Compulsions are movements or ritualistic behaviours used to reduce stress. Examples include hand washing and fear of contamination, counting behaviours possibly associated with switches and arranging objects in a specific, perhaps symmetrical fashion. The movements are not stereotyped and are purposeful.

Their performance is usually present on a background of inflexible rules and intrusive thoughts12. The actions are voluntary but there is a need to perform them, patients describe a fear of impending doom if they are not carried out.

Tic and stereotypies may also be present due to the overlapping nature of these conditions.

PAROXYSMAL DYSKINESIAS

The paroxysmal dyskinesias are part of the group termed ‘hyperkinetic movement disorders’. A term which refers to abnormal, repetitive involuntary movements and encompasses most of the childhood movement disorders including tics, chorea/ballismus, dystonia, myoclonus, stereotypies and tremor. These movements are phenotypically linked by excess unwanted movements and are known to share common neural pathways involved in voluntary motor control. Including primary and secondary motor and sensory cortices, the basal ganglia, thalamus and cerebellum13.

Paroxysmal dyskinesias: kinesiogenic and non-kinesiogenic. These are episodic disorders where abnormal movements are only present at certain times. Between ‘attacks’ most people are well. Bouts of abnormal movements are not usually accompanied by a loss of consciousness. The movements can be of a variety of types or a combination of dystonia, choreic or ballistic movements. Paroxysmal kinesiogenic dyskinesia (PKD) is action induced, such as by a particular movement or as a result of a startle or sudden movement. PKD movements can occur up to a hundred times per day. There is often a preceding sensation in the affected limb and resulting movements are short, seconds to minutes in duration. Usually a particular side of the body or single limb will be affected and movements can be dystonic. The movements can mimic functional movement disorders so delineation between the two disorders is needed. It may be inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion. The 16p11.2 locus which encompasses the PRRT2 gene were recently implicated in both PKD and PNKD14.

In inherited cases the age of onset is usually between 5 and 15 years. In cases without family history onset can be more variable. These cases may be secondary due to a range of underlying medical conditions such as metabolic disorders, neurological conditions including cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis, encephalitis and cerebrovascular disease, physical trauma and miscellaneous conditions such as supranuclear palsy or HIV Infection. Drugs such as Cocaine and dopamine blocking agents may also induce Dyskinesias.

Paroxysmal Non Kinesiogenic Dyskinesia may also be inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion. Disordered movement of this sort can occur at any time between early childhood and early adulthood. Attacks of movement disorder occur less frequently than in PKD, often occurring on two or three occasions per year. Certain triggers may be identifiable such as caffeine, tiredness, alcohol or stress. Attacks last from a few seconds to a few hours and often begin in one limb them spread throughout the body to include the face. The affected individual may not be able to communicate during the attack but remains conscious and breathing rate is normal.

The pathophysiology of these paroxysmal dyskinesias is attributed to basal ganglia dysfunction. PKD has previously been classified as part of both epilepsy and an inherited episodic ataxia.

Treatment is difficult but is possible. Its aim is to reduce muscle spasms, pain, disturbed posture and dysfunction. Several different agents may need to be trialed before symptoms are alleviated. PKD generally responds to anticonvulsants such as low dose carbamzepine, other drugs such as levodopa or anticholinergics may be useful. In these complex cases specialist input is advised.

Box 6. Co-morbidities in Early Developmental Movement Disorders

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD)

Specific learning difficulties

Obsessive Compulsive Behaviours or disorder (OCBs/OCD)

Behavioural difficulty

Sleep problems

Rage attacks

ADHD

Depression/Anxiety/Emotional problems

Conduct disorder

FUNCTIONAL (PSYCHOGENIC) MOVEMENT DISORDERS

These movements can be either hyper- or hypokinetic in nature. They have not been accounted for by any known organic syndrome and are thought to have significant psychological and or psychiatric contributants15. They are usually deemed a Medically Unexplained Symptom and were previously termed ‘conversion disorder’16. The historical emphasis on emotional trauma, is not supported by epidemiological studies.

While there are several theories, it has been hypothesised there are faulty inhibitory circuits of motor control. Additionally, the intensity of the psychogenic movements worsen when patients are exposed to stressful and/or emotionally-charged situations17.

The similarity between physical signs in functional disorders and those that occur in feigned illness has raised important challenges for pathophysiological understanding and has challenged health professionals' attitudes toward patients with these disorders18. Diagnosis is a specialist centre is important so that cognitive underpinnings can be explored and identified. Managing the neuro-developmental associations is usually key and important before addressing the presenting symptom. Many children presenting acutely to paediatrics and neurology with functional symptoms have an unidentified specific learning problems, social communication difficulties or Tic disorder.

MYOCLONUS DYSTONIA SYNDROME

This condition is a rare childhood hyperkinetic movement disorder which presents as upper body myoclonus and dystonia. A proportion of cases are due to the maternally imprinted Sarcoglycan Epsilon (SGCE) gene19.

Onset is within the first two decades of life. In around 50% of cases there is Cervical Dystonia and/or Writer's cramp associated with the upper limb and trunk myoclonus.

Comorbid psychiatric conditions have been reported in a number of cases19 and are most commonly Obsessive compulsive behaviours, depression, suicide, psychosis, anxiety and alcohol misuse.

Investigations such as EEG, somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEP) and neuro-imaging are usually normal. It usually offers a variable but relatively benign course and is compatible with a normal, active life span.

Treatment options available would include:

Benzodiazepines such as Clonazepam can be used to treat the myoclonus and tremor. Valproate and Topiramate can improve myoclonus but the response is variable20. More invasive techniques such as Botulinum toxin injection for cervical dystonia, stereotactic thalotomy to improve myoclonus and deep brain stimulation have all been used with variable results and not without considerable risk of further morbidity.

AKATHISIA: ‘INNER RESTLESSNESS’

Akathisia makes the child feel as if they need to walk or move. There is a feeling of discomfort and movement eases this discomfort. Therefore the movement associated with Akathisia is voluntary and includes pacing up and down, rubbing the legs, face or scalp with the hands.

Akathisia can occur in children as a result of

Iron deficiency, thyroid disorders and as a side effect of drugs for example neuroleptic medications such as Haloperidol or Pimozide.

An underlying medical condition should be suspected and ruled out in the first instance.

PAEDIATRIC AUTOIMMUNE NEUROPSYCHIATRIC DISORDER ASSOCIATED WITH STREPTOCOCCAL INFECTION (PANDAS)

This is an interesting and controversial proposed immune mediated mechanism for the development of tics and Tourette Spectrum disorder in the paediatric population.

There is increasing evidence that these disorders are autoimmune and are mediated by antibodies that bind and cause dysfunction within the central nervous system, specifically in the basal ganglia. These antibodies are universal in acute Sydenham's chorea and post-streptococcal dystonia21. The hypothesis is that an antecedent group A Haemolytic streptococcal infection could lead to molecular mimicry at the basal ganglia and then produce a neuropsychiatric manifestation.

Box 7. Characteristic of PANDAs subgroup

Chronic tic disorder or OCB

Pre-pubertal onset

Episodic course with acute, severe onset and explosive exacerbations

Neurological abnormalities

A documented relationship between streptococcal infection and the presence of symptoms

New findings in relation to the cell and molecular biology of the neuroimmunological mechanisms could help improve understanding of environmental factors involved in the pathogenesis of movement and psychiatric disorders. Recent studies have also provided more systematic evidence of related psychopathology22. It now appears that a wide range of psychiatric and movement disorders can occur following streptococcal infection, in patients who do not meet diagnostic criteria for Sydenham's chorea.

There is currently intense interest in PANDAS and large clinical trials continue. There is no good evidence at present for treating with antibiotic prophylaxis although there are many unanswered questions. Immune mediated mechanisms do warrant further research. Interested readers should also consult reference 23 of this article.

INFANTILE GRATIFICATION SYNDROME

Also described as benign idiopathic infantile dyskinesia. This condition is rarely discussed in the literature although self stimulation in children is a variant of normal behaviour24. Episodes occur with starring and shaking, accompanied by limb twitching or jerking for several minutes at a time. Diagnosis is more difficult when children appear upset or in discomfort during the episode. Commonly mistaken as abdominal pain, epilepsy or dystonia.

It can occur at any time throughout childhood even in the very early months of life. It is important to look at triggers such as sitting in a car seat or high chair where straps are placed in between the child's legs. Video evidence is very helpful.

It is frequently over investigated and treated with anti-epileptic medication. Reassurance for parents and distracting the child from the trigger is the best form of treatment.

SHUDDERING ATTACKS

These benign paroxysmal events occurring during childhood are non epileptic in origin. Superficially they mimic many seizure types such as tonic-clonic, absence and myoclonic seizures. They are thought to be uncommon but may be under reported. Episodes are brief and consist of brief shivering movements affecting head, neck and occasionally the trunk. Events can occur hundreds of times in a day and can be precipitated by certain movements or activities such as eating.

The pathophysiology is unknown but a link to essential tremor has been hypothesised. EEG is normal but essential as this is a diagnosis of exclusion. Reassurance is crucial and episodes usually spontaneously resolve.

HYPEREKPLEXIA

This hereditary disorder of early movement is also known as ‘excessive startle’ and can be easily recognised and explained this way. However the condition encompasses further features which may be of concern to parents or caregivers and has the potential for serious complications raising its importance with healthcare professionals.

The excessive startle response is accompanied by hypertonicity. Symptoms are present at birth and usually improve in the first year of life. Affected individuals have stiffness in the trunk and limbs following an excessive startle and are left briefly unable to move. Loud or sudden acoustic, tactile or sensory stimuli will result in exaggerated startle response. Tapping the nose will reproduce these results, a sign which persists into adulthood. The startle response may be accompanied by apnoea leading to aspiration if occurring during feeding and a hypothesised link to sudden infant death syndrome25. Hypnagogic myoclonus or excessive limb movements during sleep may also be present.

The hereditary aspects of this disorder are well documented with links to glycine and sodium channel mutations.

Glycine acts as an inhibitory neurotransmitter In the brain and spinal cord26. It is important to bear in mind in an adulthood population because of the concerns that will arise in any offspring.

This is one of the treatable neuroinherited conditions and as symptoms persist into adulthood medication is often necessary to prevent ‘drop attacks’ which can be debilitating and socially isolating. Clonazepam is usually the treatment of choice and can limit much of the morbidity and mortality of this condition.

CONCLUSION

There are many different movements that present in childhood. Disordered movements can be difficult to delineate from those seen in normal development. In this paper we have highlighted the importance of appropriate assessment and when necessary thorough psychoeducation. Many of the movements discussed are managed with careful explanation, reassurance and watchful waiting. Where additional management and treatment is necessary we have emphasised the importance of joint working with specialist Tourette's services, Child and Adolescent Mental Health services (CAMHS) or tertiary neurology clinics. These centres can provide further support and up to date evidence based management including psychological therapies or psychopharmacological approaches for affected children and their families.

The movement disorders seen in early development are prone to under recognition and also conversely to over-investigation and by highlighting concerning or unusual features the aim is to reduce investigation in some cases whilst targeting appropriate investigation in others in order to lessen the care burden.

This is an area which is growing rapidly in terms of knowledge and expertise around the neurobiology underpinning these disorders. It forms part of a constantly evolving picture as more is known about the developmental processes taking place in the cortico-striatal-thalamo cortical pathways, basal ganglia and cerebellum. The full implications of the movements seen in early childhood together with the developmental differences and co-morbid difficulties is yet to be elucidated and provides many challenges for the interested practitioners in the field and the families and children involved.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders - Text Revision, DSM-IV TR. 4th revised ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association. 2000.

- 2.Mahone EM, Bridges D, Prahme C, Singer HS. Repetitive arm and hand movements (complex motor stereotypies) in children. J Pediatr. Sep. 2004;145(3):391–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Troster H, Bambring M, Beelmann A. Prevelance and situational causes of stereotyped behaviours in blind infants and preschoolers. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 19(5):569–590. doi: 10.1007/BF00925821. 1991 Oct. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verdellen C, van de Griendt J, Hartmann A, Murphy T. European Clinical Guidelines for Tourette Syndrome and other tic disorders. Part III behavioural and psychological interventions. Eur child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20:197–207. doi: 10.1007/s00787-011-0167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cath DC, Hedderly T, et al. European Clinical Guidelines for Tourette Syndrome and other tic disorders. Part I: Assessment. Eur child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20:155–171. doi: 10.1007/s00787-011-0164-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roessner V, Plessen KJ, et al. European Clinical Guidelines for Tourette Syndrome and other tic disorders. Part II: Pharmacological treatment. Eur child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20:173–196. doi: 10.1007/s00787-011-0163-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roessener V, Rothenberger A, Rickards H, Hoeskstra PJ. European Clinical Guidelines for Tourette Syndrome and other tic disorders. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20:153–154. doi: 10.1007/s00787-011-0165-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muller-Vahl KR, Cath DC, et al. l. European Clinical Guidelines for Tourette Syndrome and other tic disorders. Part IV: deep brain stimulation. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20:209–217. doi: 10.1007/s00787-011-0166-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shapiro AK, Shapiro ES, Young JG, Feinberg TE. Gilles de la Tourette syndrome 2nd Edn. New York: Raven Press; [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mol Debes NM, Hjalgrim H, Skov L. Limited Knowledge of Tourette Synrdome causes delay in diagnosis. Neuropediatrics. 39:101–105. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1081457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pauls DL, Raymond CL, Stevenson JM, Leckman JF. A Family Study of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Am J Hum Genetics. 1991;48:154–163. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahone EM, Bridges D, Prahme C, Singer HS. Repetative Arm and Hand Movements (Complex motor stereotypies) in children. J Pediatr. 2004;145(3):391–395. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walter BL, Vitek JL. Pathophysiology of Hyperkinetic movement disorders. Current Clinical Neurology. 2012:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 14. http://www.OMIM.org/entry/128200.

- 15.Williams DT, Ford B, Fahn S. Phenomenology and psychopathology related to psychogenic movement disorders. Adv Neurol. 1995;65:231–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carson AJ, Brown R, Schrag AE, et al. Functional (conversion) neurological symptoms: research since the millennium. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83(8):842–850. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2011-301860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. National institute of neurological disorders and stroke. http://www.ninds.nih.gov/jobs_and_training/summer/2008_student/Min_Wu_Abstract. htmAugust 26, 2008.

- 18.Edwards MJ, Kailash PB. Functional (psychogenic) movement disorders: merging mind and brain. The Lancet Neurology. 2012;11(3):250–260. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70310-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peall KJ, Smith DJ, et al. SGCE Mutations cause Psychiatric Disorders: Clinical and Genetic Characterization. Brain. 2013;136:294–303. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raymond D, Ozelius L. Synonyms: Hereditary Essential Myoclonus, Myoclonic Dystonia. Gene Reviews by Title. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1414/2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dale R, Heyman I. Editorial: Post-streptococcal autoimmune psychiatric and movement disorders in children. British Journal of Pyschiatry. 2002;181(3):188–190. doi: 10.1192/bjp.181.3.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swedo et al,. Paediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections: clinical description of first 50 cases. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1989;155:264–271. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.2.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marino D, Defazio G, Giovanni G. The PANDAS subgroup of tic disorders and child-hood onset obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2009;67:547–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leung AK, Robson WL. Childhood masturbation. Clin Pediatr. 993(32):238–41. doi: 10.1177/000992289303200410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindahl A. Neurological rarities:Startles, Jump. Practical Neurology. 2005;5(5):292–296. [Google Scholar]

- 26. hereditary hyperekplexia http://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/hereditaryhyperekplexia.