Abstract

We studied 2332 individuals with monoallelic mutations in MUTYH among 9504 relatives of 264 colorectal cancer (CRC) cases with a MUTYH mutation. We estimated CRC risks, through 70 y of age, of 7.2% for male carriers of monoallelic mutations (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.6%–11.3%) and 5.6% for female carriers of monoallelic mutations (95% CI, 3.6%–8.8%), irrespective of family history. For monoallelic MUTYH mutation carriers with a first-degree relative with CRC, diagnosed by 50 y of age who does not have the MUTYH mutation, risks of CRC were 12.5% for men and (95% CI, 8.6%–17.7%) and 10% for women (95% CI, 6.7%–14.4%). Risks of CRC for carriers of monoallelic mutations in MUTYH with a first-degree relative with CRC are sufficiently high to warrant more intensive screening than for the general population.

Keywords: colon cancer, genetics, base excision repair gene, DNA damage response

MUTYH is a base excision repair gene that detects and protects against oxidative DNA damage.1 Individuals with germline mutations in both alleles (biallelic mutation carriers), whether they are homozygotes or compound heterozygotes, develop MUTYH-associated polyposis, an autosomal recessive disorder with substantially increased risk of CRC.2 Individuals with germline mutations in one allele (monoallelic mutation carriers) have a small increased risk of CRC3–5. Due to the rarity of these mutations,4, 6 previous studies have had limited ability to provide precise estimates of age- and sex-specific CRC risks for MUTYH mutation carriers. Further, the variability in CRC risk between carriers has not been quantified. Modelling of this variability can indicate a potential role for modifiers of risk.

RESULTS

We identified 9504 relatives (4613 females) from the families of the 264 (236 population-based and 28 clinic-based) probands with a monoallelic or biallelic MUTYH mutation from the Colon Cancer Family Registry; 138 (52%) from USA, 81 (31%) from Canada, and 45 (17%) from Australia and New Zealand. In the relatives, we observed 261 CRCs (114 females) whose ages at diagnosis had a median of 65 (range 26–98) years. MUTYH mutation status was known for 340 relatives (13 biallelic mutation carriers, 142 monoallelic mutation carriers, and 185 non-carriers). We estimated an additional 43 biallelic and 2190 monoallelic mutation carriers among non-genotyped relatives, giving a total estimated number of 56 biallelic and 2332 monoallelic mutation-carrying relatives in our sample.

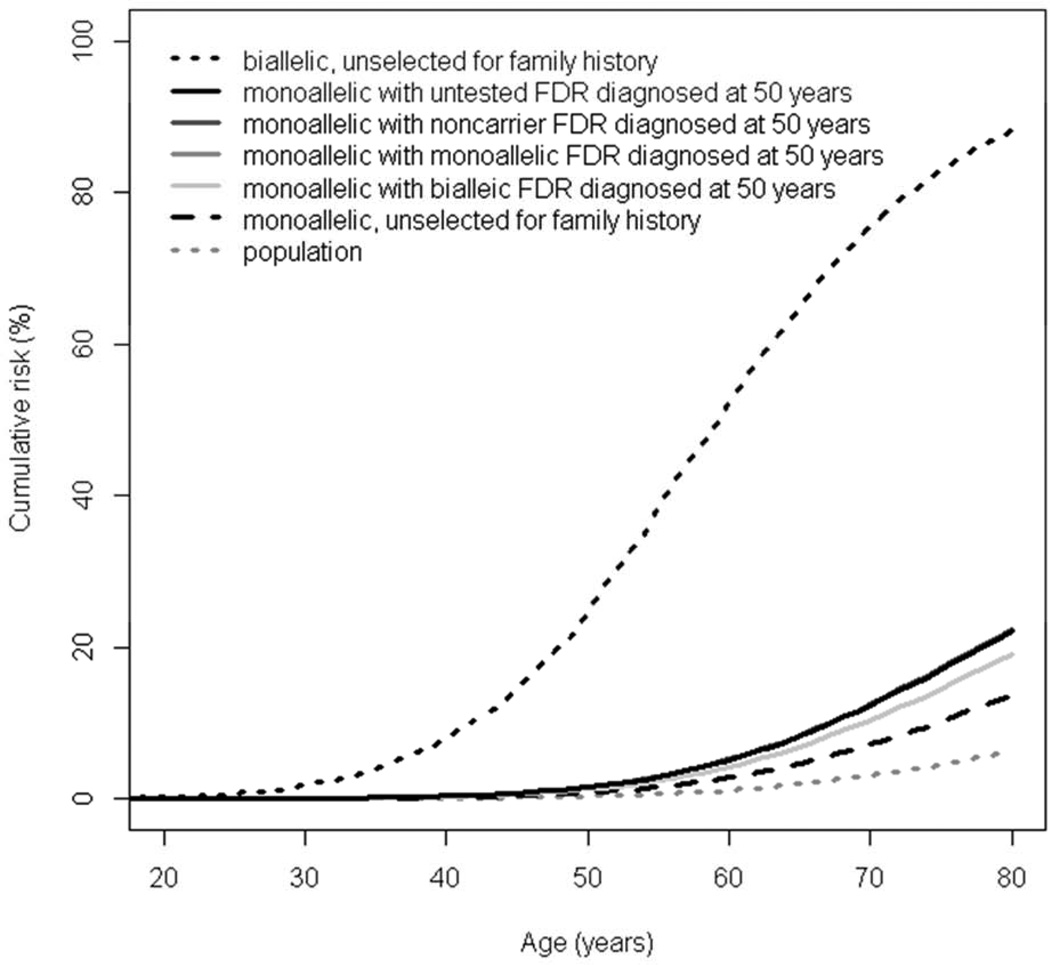

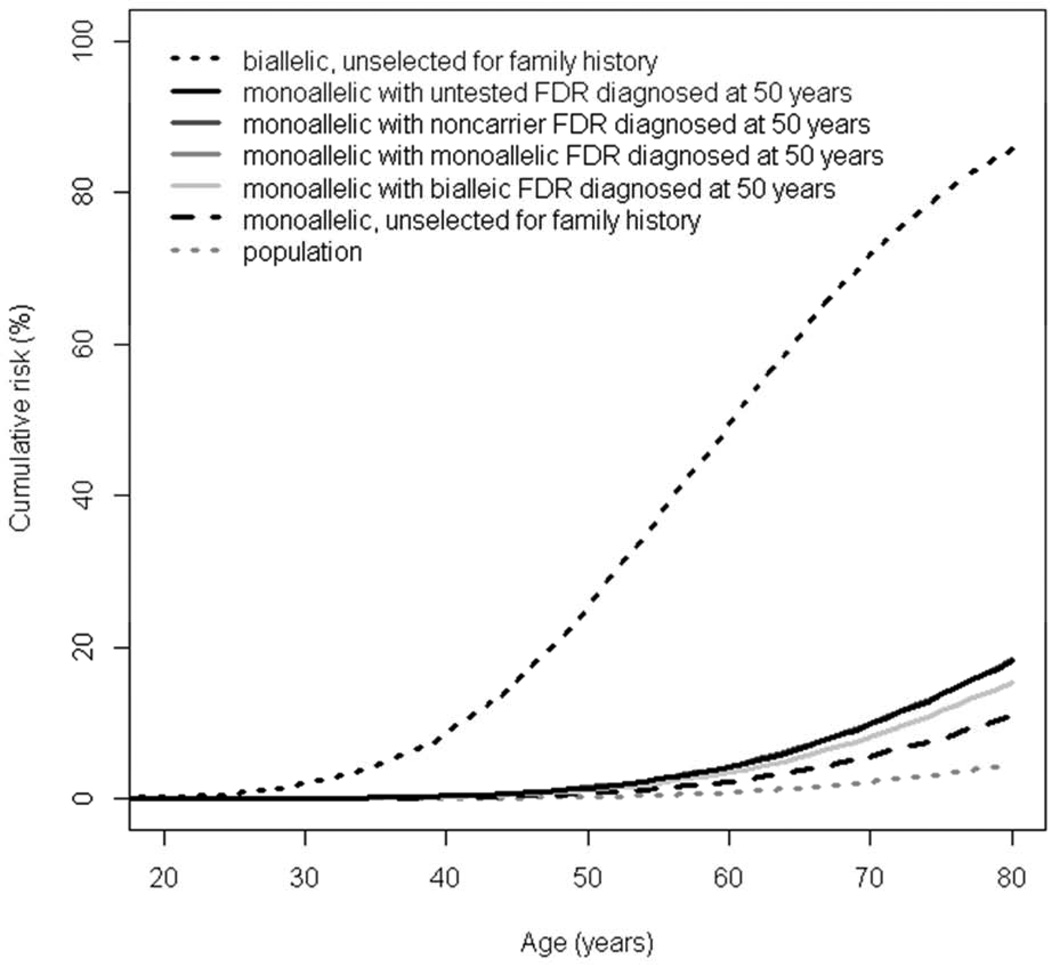

Our methods allowed for CRC risk estimation in mutation families to be due to the MUTYH mutation as well as polygenic factors (combination of a large number of CRC-associated genetic susceptibility loci).7 We estimated CRC risks, through 70y of age, for male and female to be: 75.4% (95%CI, 41.2%–96.6%) and 71.7% (95%CI, 44.5%–92.1%), respectively, for biallelic mutation carriers, and 7.2% (95%CI, 4.6%– 11.3%) and 5.6% (95%CI, 3.6%–8.8%), respectively, for monoallelic mutation carriers (Figure 1). The estimated CRC risks, through 70y of age, for monoallelic mutation carriers with a first-degree relative with CRC were similar whether the relative was untested or a non-carrier or a monoallelic mutation carrier: approximately 12% (95%CI, 9%–18%) and 10% (95%CI, 7%–14%) respectively for males and females in comparison with males and females from the general population (2.9% and 2.1% respectively). However, if their affected first-degree relative was a biallelic mutation carrier then risks of CRC, through 70y of age, for monoallelic mutation carriers was estimated to be 10.4% (95%CI, 7.0%–15.0%) and 8.2% (95%CI, 5.4%–12.0%) respectively for males and females (Table 1). In addition, we estimated CRC risks for six other scenarios (Supplementary Figure 1). The highest risk of CRC for a monoallelic mutation carrier corresponded to having two affected first-degree relatives: one is a biallelic mutation carrier and one is a noncarrier (Supplementary Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Cumulative risk of colorectal cancer for (A) male and (B) female MUTYH mutation carriers. Note that the risks for a monoallelic carrier with an affected firstdegree relative (FDR) who is either untested, a noncarrier or a monoallelic carrier are virtually identical (see Table 1) so the unbroken, darker grey lines cannot be distinguished in the figure.

Table 1.

Cumulative risks (95% confidence intervals) of colorectal cancer for biallelic and monoallelic MUTYH mutation carriers

| Age (years) |

General population |

Biallelic mutation carriers irrespective of family history |

Monoallelic mutation carriers |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| irrespective of family history |

with untested FDR diagnosed at 50 years |

with non-carrier FDR diagnosed at 50 years |

with monoallelic FDR diagnosed at 50 years |

with bialleic FDR diagnosed at 50 years |

|||

| Male | |||||||

| 30 | 0.01 | 1.8 (0.4–6.8) | 0 (0–0.1) | 0.1 (0.1–0.1) | 0.1 (0–0.1) | 0.1 (0–0.1) | 0.1 (0–0.1) |

| 40 | 0.07 | 8.1 (2.1–25.2) | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) | 0.4 (0.3–0.6) | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) | 0.4 (0.2–0.6) | 0.3 (0.2–0.5) |

| 50 | 0.3 | 24.8 (7.7–57.1) | 0.8 (0.5–1.3) | 1.6 (1.0–2.5) | 1.6 (1.0–2.5) | 1.6 (1.0–2.5) | 1.3 (0.8–1.9) |

| 60 | 1.1 | 52.3 (21.8–85.4) | 2.8 (1.8–4.5) | 5.2 (3.4–7.8) | 5.2 (3.4–7.9) | 5.2 (3.4–7.7) | 4.2 (2.8–6.3) |

| 70 | 2.9 | 75.4 (41.2–96.6) | 7.2 (4.6–11.3) | 12.4 (8.6–17.5) | 12.5 (8.6–17.7) | 12.4 (8.6–17.4) | 10.4 (7.0–15.0) |

| 80 | 6.2 | 88.2 (58.4–99.3) | 13.6 (8.8–21.1) | 22.2 (16–29.8) | 22.3 (16.1–30) | 22.2 (16.1–29.9) | 19.1 (13.2–26.6) |

| Female | |||||||

| 30 | 0.01 | 2 (0.7–5.5) | 0 (0–0.1) | 0.1 (0.1–0.1) | 0.1 (0.1–0.1) | 0.1 (0.1–0.1) | 0.1 (0–0.1) |

| 40 | 0.06 | 8.7 (3.1–20.7) | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) | 0.4 (0.2–0.6) | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) | 0.4 (0.2–0.6) | 0.3 (0.2–0.5) |

| 50 | 0.3 | 25.4 (10.8–49.1) | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) | 1.5 (0.9–2.3) | 1.5 (0.9–2.4) | 1.5 (0.9–2.4) | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) |

| 60 | 0.8 | 49.4 (25.3–76.3) | 2.3 (1.5–3.7) | 4.3 (2.8–6.4) | 4.3 (2.8–6.6) | 4.3 (2.8–6.5) | 3.5 (2.2–5.2) |

| 70 | 2.1 | 71.7 (44.5–92.1) | 5.6 (3.6–8.8) | 9.9 (6.7–14.2) | 10 (6.7–14.4) | 9.9 (6.7–14.2) | 8.2 (5.4–12.0) |

| 80 | 4.4 | 85.7 (61.8–97.8) | 10.9 (7–16.8) | 18.2 (12.8–24.9) | 18.3 (12.9–25.2) | 18.2 (12.8–25.0) | 15.4 (10.4–21.9) |

FDR, first-degree relative; CRC, colorectal cancer.

We found no evidence for a difference in hazard ratios of CRC for biallelic mutation carriers between males and females (108 (95%CI, 25.9–454) vs 129 (95%CI, 43.7–380); p=0.85), nor for monoallelic mutation carriers between males and females (2.46 (95%CI, 1.54–3.93) vs 2.67 (95%CI, 1.67–4.26); p=0.81). Hazard ratio of CRC for Y179C monoallelic carriers was higher than for G396D monoallelic carriers (4.81 (95%CI, 3.00–7.71) vs 2.42 (95%CI, 1.48–3.98); p=0.05), but there was no difference between biallelic carriers of Y179C and G396D (p=0.84) (Supplementary Table 1).

The standard deviation of the polygenic component was estimated to be 1.11 (0.74–1.49, p<0.001); see the Materials and Methods for a general formula relating this standard deviation to the hazard ratio. At ages less than 50y this formula reduces to Pharoah’s formula for early-onset disease7 and says that monoallelic MUTYH mutation carriers with an affected first-degree relative have CRC incidences approximately 4.58 (for males) or 4.97 (for females) times the population incidences. However, Supplementary Figure 2 gives precise hazard ratios for all ages and shows that by age 70y, Pharoah’s formula over-estimates relative risks by roughly 30%.

DISCUSSION

Our finding of almost complete penetrance for biallelic MUTYH mutation carriers is consistent with previous studies.8–10 There is some evidence that biallelic mutation carriers move rapidly along a mutator phenotype progression to cancer.11 These findings support the recommendation that biallelic mutation carriers should consider prophylactic total colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis depending on the individual, age of presentation and number and size of polyps present.12

We estimated monoallelic mutation carriers had on average, an approximately 2.5-fold increased risk of CRC compared with the general population, consistent with one previous study.13 This level of increased risk for monoallelic mutation carriers is similar to that for people with a first-degree relative with CRC, who are recommended 5-yearly colonoscopy starting 10y younger than the youngest case in the family and before age 50y.13 However, monoallelic mutation carriers who have an affected first-degree relative were at approximately 5-fold increased risk. For these carriers, colonoscopy beginning at age 40y, with follow-up at intervals dependent on the presence or absence of polyps but no less often than every 5 years, may be reasonable.

We observed strong evidence that CRC risks for carriers are highly heterogeneous. The observed heterogeneity in risk could also be caused by environmental factors shared between family members or by differences in risk between mutations. To our knowledge, thus far the only study investigating modifiers of CRC risks for MUTYH mutation carriers was on the relationship with hormone replacement therapy, which reported no evidence of interaction between hormone replacement therapy and MUTYH mutations.3

In this study of 12 variants of MUTYH mutations, 93% of the MUTYH mutations were Y179C and G396D (Supplementary Table 2); consistent with a previous study of Caucasians.14 We found CRC risk was higher for monoallelic carriers of Y179C than for G396D; consistent with previous studies.3, 15 However, given our approach of genotyping for 12 mutations by MS and WAVE followed by confirmatory Sanger sequencing of MUTYH in carriers (Materials and Methods), there is the possibility that we missed other pathogenic mutations in MUTYH that were not one of the 12 mutations genotyped. Although we identified additional variants from Sanger sequencing, their pathogenicity was considered inconclusive (unclassified variants) and therefore not included in this analysis. Additional MUTYH mutations may reside in different ethnic groups however this cohort was predominantly Caucasian.

We used sophisticated statistical techniques to adjust for ascertainment, to account for residual familial aggregation of disease and therefore avoid bias, and to use data for all family members, whether genotyped or not, and therefore maximized statistical power and avoided survival bias.

In conclusion, using the largest international study to date we have produced unbiased estimates of CRC risks for MUTYH mutation carriers which are the most precise and reliable currently available. In addition to the confirmed very high risk of CRC to biallelic MUTYH mutation carriers, CRC risk for monoallelic mutation carriers depends on family history and can be sufficiently high to warrant consideration of more intensive CRC screening than for the general population.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank all study participants of the Colon Cancer Family Registry and staff for their contributions to this project.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health under RFA #CA-95-011 and through cooperative agreements with members of the Colon Cancer Family Registry and Principal Investigators. Collaborating centers include Australasian Colorectal Cancer Family Registry (U01 CA097735), Familial Colorectal Neoplasia Collaborative Group (U01 CA074799) [USC], Mayo Clinic Cooperative Family Registry for Colon Cancer Studies (U01 CA074800), Ontario Registry for Studies of Familial Colorectal Cancer (U01 CA074783), Seattle Colorectal Cancer Family Registry (U01 CA074794), and University of Hawaii Colorectal Cancer Family Registry (U01 CA074806). This work was also supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute, USA (R01CA170122) and a Centre for Research Excellence grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), Australia (APP1042021). AKW is supported by the Picchi Brothers Foundation Cancer Council Victoria Cancer Research Scholarship, Australia. MAJ is an NHMRC Senior Research Fellow. JLH is a NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellow. CR is a Jass Pathology Fellow.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DISCLAIMER

The content of this manuscript does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the National Cancer Institute or any of the collaborating centers in the CFRs, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government or the CFR. Authors had full responsibility for the design of the study, the collection of the data, the analysis and interpretation of the data, the decision to submit the manuscript for publication, and the writing of the manuscript.

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare with respect to this manuscript.

Authors’ Contributions

Aung Ko Win: study concept and design; acquisition of data; statistical analysis; interpretation of data; drafting and critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final version of the manuscript

James G. Dowty: study concept and design; statistical analysis; interpretation of data; drafting and critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final version of the manuscript

Sean P. Cleary: acquisition of data; interpretation of data; critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final version of the manuscript

Hyeja Kim: acquisition of data; interpretation of data; critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final version of the manuscript

Daniel D. Buchanan: acquisition of data; interpretation of data; critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final version of the manuscript

Joanne P. Young: acquisition of data; interpretation of data; critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final version of the manuscript

Mark Clendenning: acquisition of data; interpretation of data; critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final version of the manuscript

Christophe Rosty: acquisition of data; interpretation of data; critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final version of the manuscript

Robert J. MacInnis: acquisition of data; interpretation of data; critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final version of the manuscript

Graham G. Giles: acquisition of data; interpretation of data; critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final version of the manuscript

Alex Boussioutas: acquisition of data; interpretation of data; critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final version of the manuscript

Finlay A. Macrae: acquisition of data; interpretation of data; critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final version of the manuscript

Susan Parry: acquisition of data; interpretation of data; critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final version of the manuscript

Jack Goldblatt: acquisition of data; interpretation of data; critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final version of the manuscript

John A. Baron: acquisition of data; interpretation of data; critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final version of the manuscript

Terrilea Burnett: acquisition of data; interpretation of data; critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final version of the manuscript

Loïc Le Marchand: acquisition of data; interpretation of data; critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final version of the manuscript

Polly A. Newcomb: acquisition of data; interpretation of data; critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final version of the manuscript

Robert W. Haile: acquisition of data; interpretation of data; critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final version of the manuscript

John L. Hopper: acquisition of data; interpretation of data; critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final version of the manuscript

Michelle Cotterchio: acquisition of data; interpretation of data; critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final version of the manuscript

Steven Gallinger: acquisition of data; interpretation of data; critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final version of the manuscript

Noralane M. Lindor: acquisition of data; interpretation of data; critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final version of the manuscript

Katherine M. Tucker: acquisition of data; interpretation of data; critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final version of the manuscript

Ingrid M. Winship: acquisition of data; interpretation of data; critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final version of the manuscript

Mark A. Jenkins: study concept and design; acquisition of data; interpretation of data; critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final version of the manuscript

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Tassan N, et al. Nat Genet. 2002;30:227. doi: 10.1038/ng828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cleary SP, et al. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1251–1260. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Theodoratou E, et al. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:1875–1884. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Win AK, et al. Fam Cancer. 2011;10:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10689-010-9399-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Win AK, et al. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:2256–2262. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grover S, Kastrinos F, et al. JAMA. 2012;308:485–492. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.8780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pharoah PDP, et al. Nat Genet. 2002;31:33–36. doi: 10.1038/ng853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lubbe SJ, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3975–3980. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.6853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farrington SM, Tenesa A, et al. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:112–119. doi: 10.1086/431213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nieuwenhuis MH, et al. Gut. 2012;61:734–738. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.229104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macrae F, et al. Gut. 2013;62:657–659. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buecher B, et al. Fam Cancer. 2012;11:321–328. doi: 10.1007/s10689-012-9511-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones N, et al. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:489–494. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheadle JP, Sampson JR. DNA Repair. 2007;6:274–279. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balaguer F, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:379–387. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.