Abstract

Objectives

We sought to determine the contemporary prevalence and management of coronary chronic total occlusions (CTO) in a veteran population.

Background

The prevalence and management of CTOs in various populations has received limited study.

Methods

We collected clinical and angiographic data in consecutive patients that underwent coronary angiography at our institution between January 2011 and December 2012. Coronary artery disease (CAD) was defined as ≥50% diameter stenosis in ≥1 coronary artery. CTO was defined as total coronary artery occlusion of ≥3 month duration.

Results

Among 1,699 patients who underwent angiography during the study period, 20% did not have CAD, 20% had CAD and prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) and 60% had CAD but no prior CABG. The prevalence of CTO among CAD patients with and without prior CABG was 89% and 31%, respectively. Compared to patients without CTO, CTO patients had more comorbidities, more extensive CAD and were more frequently referred for CABG. Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) to any vessel was performed with similar frequency in those with and without CTO (50% vs. 53%). CTO PCI was performed in 30% of patients without and 15% of patients with prior CABG with high technical (82% and 75%, respectively) and procedural success rates (80% and 73%, respectively).

Conclusions

In a contemporary veteran population, coronary CTOs are highly prevalent and are associated with more extensive comorbidities and higher likelihood for CABG referral. PCI was equally likely to be performed in patients with and without CTO.

Keywords: coronary occlusion, percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery disease

Introduction

The contemporary prevalence and management of coronary chronic total occlusions (CTO) has received limited study and vary significantly in different patient populations (1–4). Patients with CTOs are more likely to be referred for coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) and less likely to undergo percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) (1,5,6), however, the choice of coronary revascularization strategy is highly dependent on local practice patterns and expertise. Recent developments in CTO PCI techniques have enabled high procedural success rates, while maintaining low risk for procedural complications (7–11). These developments are especially important for the veteran population, which is known to have high coronary artery disease (CAD) burden (12). The goal of the present study was to evaluate the prevalence and contemporary management of coronary CTOs at a Veterans Affairs tertiary referral center with expertise in CTO PCI.

Materials and Methods

Patients

We retrospectively reviewed the coronary angiograms and medical records of all consecutive patients who underwent diagnostic coronary angiography at our institution between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2012. Clinical information such as demographics, cardiac history, comorbidities, procedural data and outcomes, and cardiac catheterization results were collected and analyzed to evaluate for the prevalence and clinical management of patients with coronary CTOs. Of the patients who had multiple cardiac catheterizations during the study period, only the first procedure was included in the present analysis. Patients who underwent angiography as part of a research protocol were excluded if the index cardiac catheterization occurred prior to January 1, 2011. The study was approved by the institutional review board of our institution.

Significant CAD was defined as ≥1 lesion of ≥50% luminal diameter stenosis. CTO was defined as a total coronary artery occlusion of ≥3 month duration with Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 0 flow. Estimation of occlusion duration was based on first onset of anginal symptoms, prior history of myocardial infarction in the target vessel territory, or comparison with a prior angiogram. The decision to undergo CTO revascularization was at the discretion of the interventional cardiologist and the patient. CTO PCI technical success was defined as successful CTO revascularization with achievement of <30% residual diameter stenosis within the treated segment and restoration of TIMI grade 3 antegrade flow. CTO PCI procedural success was defined as technical success without in-hospital major adverse cardiac events (MACE). In-hospital MACE included any of the following adverse events prior to hospital discharge: death from any cause, Q-wave myocardial infarction, recurrent angina requiring urgent repeat target vessel revascularization with PCI or coronary bypass surgery, tamponade requiring pericardiocentesis or surgery, or stroke.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous parameters were presented as mean ± standard deviation and compared using the student’s t test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test, as appropriate. Nominal parameters were presented as percentages and compared using Pearson’s chi-square test. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using JMP 10.0.2 software (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Patients

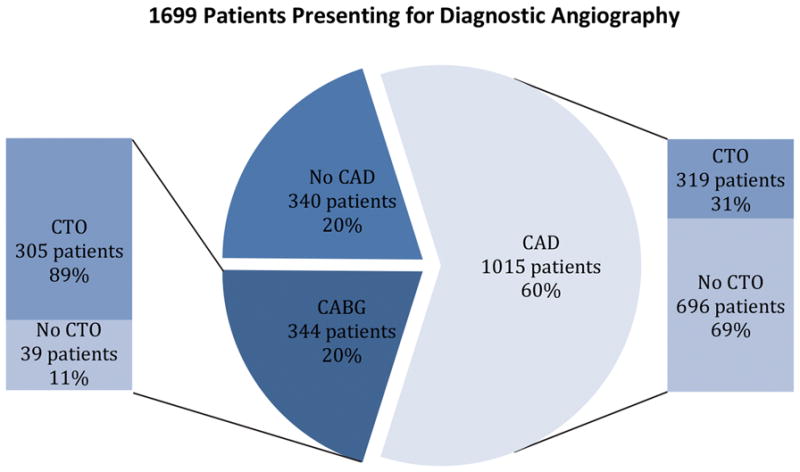

Between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2012, 1,699 consecutive patients underwent diagnostic coronary angiography at our institution; 80% of them had CAD (20% with and 60% without prior CABG, Figure 1). At least one coronary CTO (total of 1,003 CTO lesions) was present in 624 patients. The prevalence of CTO was 37% among all patients and 46% among patients with CAD. The prevalence of coronary CTOs among CAD patients without prior CABG was 31% while the prevalence of coronary CTOs among CAD patients with prior CABG was 89% (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patients Presenting for Diagnostic Angiography

Prevalence of coronary artery disease and coronary chronic total occlusions in the study population.

CABG=coronary artery bypass graft; CAD=coronary artery disease; CTO=chronic total occlusion

CTO in patients with CAD and without prior CABG

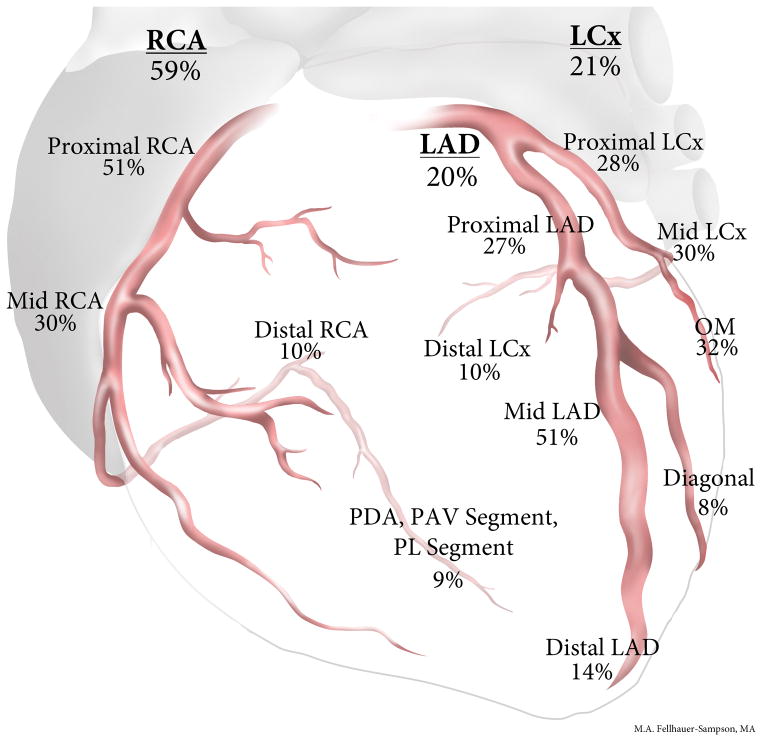

At least one CTO was present in 319 of 1,015 patients (31%), who had a total of 402 CTOs (24% of patients had >1 CTO). Compared to patients without a CTO, patients with a CTO were more likely to have both cardiac and non-cardiac comorbidities, presented more frequently with stable angina and had more extensive CAD (Table I). In the 244 patients with 1 CTO, most CTOs were located in the right coronary artery (RCA) (59%), followed by the circumflex (21%) and left anterior descending artery (LAD) (20%). Most RCA and LAD CTOs were located in the proximal or mid-vessel segment, whereas circumflex CTOs were more evenly distributed along the vessel (Figure 2). Thirty-two of the 402 CTOs (8%) were due to in-stent restenosis (ISR) in 31 patients.

Table I.

Baseline characteristics of non-CABG patients with coronary artery disease in the study population, classified according to the presence of a coronary chronic total occlusion.

| Variable | Non-CTO Group (n = 696 patients) | CTO Group (n = 319 patients) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 64 ± 9 | 65 ± 8 | 0.07 |

| Male | 687 (99%) | 318 (100%) | 0.14 |

| Ethnicity | 0.92 | ||

| Caucasian | 504 (72%) | 234 (73%) | |

| Black | 152 (22%) | 67 (21%) | |

| Hispanic | 28 (4%) | 14 (4%) | |

| Other | 12 (2%) | 4 (1%) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30 ± 6 | 30 ± 6 | 0.79 |

| Hypertension | 623 (90%) | 281 (88%) | 0.50 |

| Dyslipidemia | 596 (86%) | 280 (88%) | 0.36 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 317 (46%) | 167 (52%) | 0.04 |

| Prior CVA | 78 (11%) | 55 (17%) | 0.008 |

| Prior CHF | 167 (24%) | 106 (33%) | 0.002 |

| Prior MI | 181 (26%) | 125 (39%) | <0.001 |

| Prior PCI | 232 (33%) | 111 (35%) | 0.65 |

| Tobacco Use | |||

| Past | 552 (79%) | 275 (86%) | 0.009 |

| Current | 264 (38%) | 138 (43%) | 0.11 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 98 (14%) | 77 (24%) | <0.001 |

| Family history of early CAD | 176 (25%) | 64 (20%) | 0.07 |

| CKD | 105 (15%) | 55 (17%) | 0.38 |

| Clinical presentation | 0.03 | ||

| Stable angina | 212 (30%) | 118 (37%) | |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 259 (37%) | 102 (32%) | |

| Other | 225 (32%) | 99 (31%) | |

| Ejection fraction (%) | <0.001 | ||

| LVEF ≥ 40% | 551 (82%) | 211 (66%) | |

| LVEF < 40% | 123 (18%) | 107 (34%) | |

| 3-vessel disease | 140 (20%) | 177 (55%) | <0.001 |

| Left Main disease | 73 (10%) | 59 (19%) | <0.001 |

| Treatment chosen | <0.001 | ||

| Medical/No Intervention | 216 (31%) | 61 (19%) | |

| PCI to any vessel | 368 (53%) | 161 (50%) | |

| CABG | 112 (16%) | 97 (30%) | |

| Medications | |||

| Aspirin | 660 (95%) | 316 (99%) | 0.001 |

| Beta-blocker | 635 (91%) | 305 (96%) | 0.01 |

| ACEI/ARB | 506 (73%) | 227 (71%) | 0.61 |

| Statin | 652 (94%) | 307 (96%) | 0.15 |

| Long-acting nitrate | 152 (22%) | 76 (24%) | 0.48 |

| Insulin | 147 (21%) | 78 (24%) | 0.24 |

Data is presented as mean ± standard deviation or number (percent).

ACEI=angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB=angiotensin-receptor blocker; BMI=body mass index; CABG=coronary artery bypass graft; CAD=coronary artery disease; CHF=congestive heart failure; CKD=chronic kidney disease; CTO=chronic total occlusion; CVA=cerebrovascular accident; LVEF=left ventricular ejection fraction; MI=myocardial infarction; PCI=percutaneous coronary intervention

Figure 2.

Distribution of CTOs in patients with one CTO

Distribution of coronary chronic total occlusions among the study patients.

CTO=chronic total occlusion; LAD=left anterior descending artery; LCx=left circumflex artery; OM=obtuse marginal artery; PAV=posterior atrio-ventricular vessel; PDA=posterior descending artery; PL=posterolateral; RCA=right coronary artery

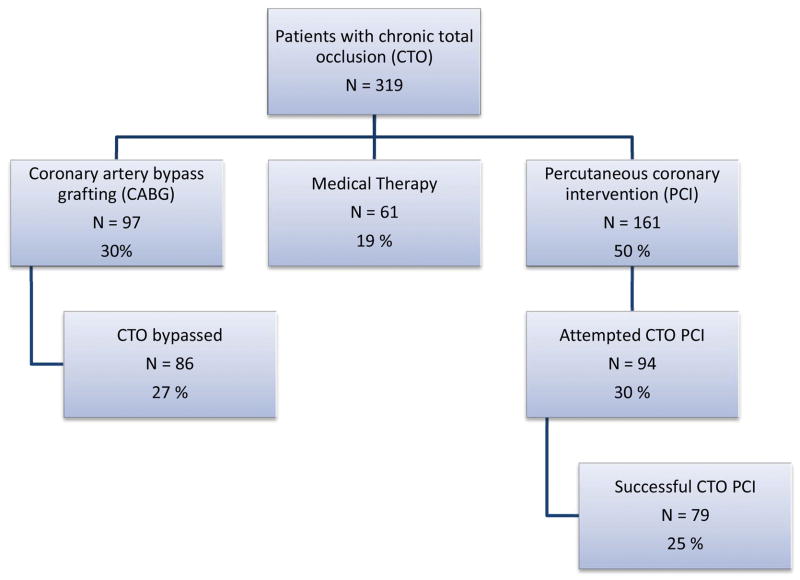

Coronary revascularization was performed in 81% of the CTO patients versus 69% of the non-CTO patients (p<0.001, Table I and Figure 3). CTO patients were more likely to undergo CABG, but equally likely to undergo PCI to any vessel compared to patients without a CTO. CTO PCI was attempted in 30% of the CTO patients with 84% per patient procedural success rate (79 of 94 patients, Figure 3). Patients with prior myocardial infarction, peripheral arterial disease, and chronic kidney disease were more likely to receive medical therapy without coronary revascularization (Table II). Patients with left main disease, 3-vessel disease, or a circumflex CTO were more likely to undergo CABG than PCI, whereas patients with 1 or 2-vessel disease CAD and LAD CTOs were more likely to undergo PCI.

Figure 3.

Revascularization Strategy in non-CABG patients

Flow chart depicting coronary revascularization strategies for patients with coronary chronic total occlusion(s) who did not have prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery.

CABG=coronary artery bypass graft; CTO=chronic total occlusion; PCI=percutaneous coronary intervention

Table II.

Coronary revascularization among patients without prior CABG who were found to have a coronary chronic total occlusion.

| Variable | Medical Therapy (n = 128 patients) | PCI (n = 94 patients) | CABG (n = 97 patients) | Overall P | P for Medical therapy vs. PCI | P for Medical therapy vs. CABG | P for PCI vs. CABG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 66 ± 9 | 64 ± 9 | 64 ± 7 | 0.26 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.63 |

| Male | 127 (99%) | 94 (100%) | 97 (100%) | 0.47 | 0.39 | 0.38 | N/A |

| Ethnicity | 0.19 | 0.07 | 0.43 | 0.41 | |||

| Caucasian | 92 (72%) | 79 (78%) | 69 (71%) | ||||

| Black | 32 (25%) | 14 (15%) | 21 (22%) | ||||

| Hispanic | 4 (3%) | 4 (4%) | 6 (6%) | ||||

| Other | 0 (0%) | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29 ± 7 | 31 ± 6 | 30 ± 6 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.22 | 0.48 |

| Hypertension | 109 (85%) | 83 (88%) | 89 (92%) | 0.32 | 0.50 | 0.13 | 0.43 |

| Dyslipidemia | 112 (88%) | 82 (87%) | 86 (89%) | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.79 | 0.76 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 69 (54%) | 47 (50%) | 51 (53%) | 0.85 | 0.56 | 0.84 | 0.72 |

| Prior CVA | 26 (20%) | 13 (14%) | 16 (16%) | 0.44 | 0.21 | 0.47 | 0.61 |

| Prior CHF | 52 (41%) | 35 (37%) | 19 (20%) | 0.003 | 0.61 | <0.001 | 0.007 |

| Prior MI | 69 (54%) | 30 (32%) | 26 (27%) | <0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.44 |

| Prior PCI | 56 (44%) | 30 (32%) | 25 (26%) | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.005 | 0.35 |

| Tobacco History | 114 (89%) | 77 (82%) | 84 (87%) | 0.31 | 0.13 | 0.57 | 0.37 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 39 (30%) | 15 (16%) | 23 (24%) | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.26 | 0.18 |

| CKD | 31 (24%) | 12 (13%) | 12 (12%) | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.93 |

| Clinical presentation | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.04 | 0.10 | |||

| Stable angina | 32 (25%) | 47 (50%) | 39 (40%) | ||||

| Acute coronary syndrome | 50 (39%) | 21 (22%) | 31 (32%) | ||||

| Ejection fraction (%) | 0.009 | 0.07 | 0.003 | 0.25 | |||

| LVEF ≥ 40% | 73 (57%) | 64 (69%) | 74 (76%) | ||||

| LVEF < 40% | 55 (43%) | 29 (31%) | 23 (24%) | ||||

| Number of vessels with CAD | <0.001 | 0.04 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| 1 | 23 (18%) | 27 (29%) | 2 (2%) | <0.001 | 0.06 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 41 (32%) | 35 (37%) | 14 (14%) | 0.001 | 0.42 | 0.002 | <0.001 |

| 3 | 64 (50%) | 32 (34%) | 81 (84%) | <0.001 | 0.02 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Left Main disease | 18 (14%) | 4 (4%) | 37 (38%) | <0.001 | 0.02 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| CTO Artery | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.88 | 0.002 | |||

| RCA | 67 (64%) | 38 (51%) | 40 (62%) | 0.23 | 0.10 | 0.77 | 0.23 |

| LAD | 14 (13%) | 27 (36%) | 8 (12%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.85 | <0.001 |

| LCx | 24 (19%) | 9 (13%) | 17 (26%) | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.63 | 0.03 |

| >1 CTO | 23 (18%) | 20 (21%) | 32 (33%) | 0.03 | 0.54 | 0.009 | 0.07 |

Data is presented as mean ± standard deviation or number (percent).

BMI=body mass index; CABG=coronary artery bypass graft; CAD=coronary artery disease; CHF=congestive heart failure; CKD=chronic kidney disease; CTO=chronic total occlusion; CVA=cerebrovascular accident; LAD=left anterior descending artery; LCx=left circumflex artery; LVEF=left ventricular ejection fraction; MI=myocardial infarction; PCI=percutaneous coronary intervention; RCA=right coronary artery

Forty-six patients presented with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, eight of whom (17%) had a non-culprit CTO. All eight patients underwent primary PCI of the culprit vessel and one patient subsequently underwent CABG. CTO PCI was later attempted in two patients (29%) with a technical success rate of 50%.

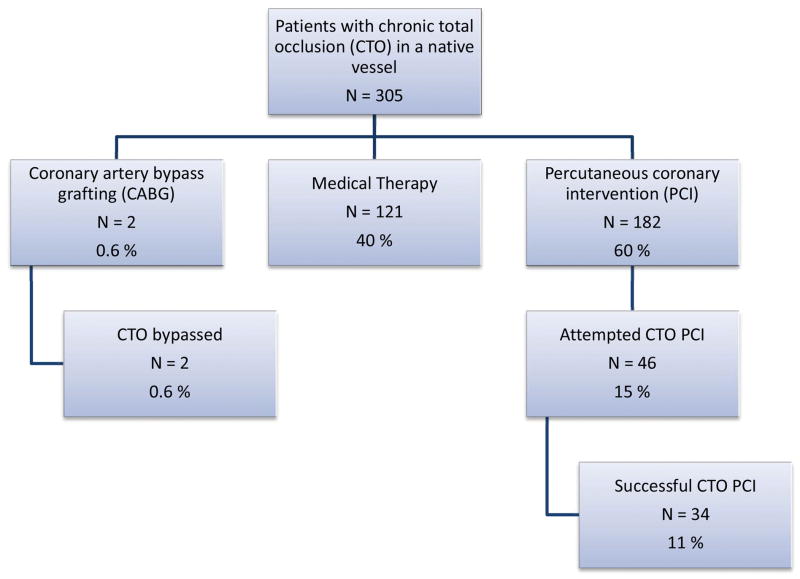

CTO in patients with CAD and prior CABG

During the study period, 305 of 344 patients (89%) with prior CABG were found to have 601 CTO lesions (66% of whom had >1 CTO). A total of 21 CTO lesions (3.5%) in 19 patients were due to in-stent restenosis. PCI was performed in 182 patients (60%) of whom 46 patients (15% of total) underwent CTO PCI (Figure 4). Two patients (0.6%) underwent redo CABG, whereas the remaining 40% received medical therapy only.

Figure 4.

Revascularization Strategy in prior CABG patients

Flow chart depicting coronary revascularization strategies for patients with coronary chronic total occlusion(s) who had prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery.

CABG=coronary artery bypass graft; CTO=chronic total occlusion; PCI=percutaneous coronary intervention

CTO PCI outcomes

During the study period, 152 CTO PCI attempts were made in 140 patients with an 80% technical success rate (78% procedural success). Technical success was 82% among non-prior CABG patients and 75% in prior CABG patients (80% and 73% procedural success rates, respectively). The CTO PCI attempt rate was significantly higher among patients without prior CABG (58% vs. 25%, p<0.001). Major complications in CTO PCI patients occurred in four patients (2.9%): two patients had post-procedural myocardial infarction (one of whom died), one patient had concomitant PCI of a non-CTO lesion which required urgent revascularization due to stent thrombosis, and one patient had an acute stroke.

Discussion

The main findings of this study are that: (a) the prevalence of CTO in non-CABG patients with CAD was 31%; (b) LAD and RCA CTOs were located mostly in the proximal and mid-vessel segments, whereas circumflex CTOs were more evenly distributed throughout the vessel; (c) patients with CTO were more likely to be referred for CABG but were equally likely to receive PCI to any vessel as those without CTO; and (d) CTO recanalization was attempted in nearly one third of patients with CTO lesions with high success and low complication rates.

The reported prevalence of CTOs among patients undergoing cardiac catheterization varies widely. In the largest study reported to date (prospective 3-center Canadian registry), the prevalence of CTO was 18.4% among patients with CAD (defined as ≥50% stenosis in ≥1 vessel) without prior CABG and 54% among patients with prior CABG (1). Using the same definition of CAD, Kahn et al. identified a CTO in 35% of 287 patients with CAD at a single institution within one year (2). In a German multicenter prospective registry spanning 64 hospitals and private practices, Werner et al. reported a CTO prevalence of 33% in 2,002 patients presenting with stable angina and first angiographic diagnosis of CAD (4). In a previous study investigating the frequency of CTO in a veteran population, Christofferson et al. reported a CTO prevalence of 52% in patients with CAD (defined as ≥70% stenosis in ≥1 vessel) and an overall prevalence of 24.5% in 8,004 non-CABG patients undergoing diagnostic angiography over a ten year period (3). The contemporary prevalence of CTOs in our veteran population was 31% among non-CABG patients presenting with CAD, which is higher than the prevalence reported by Fefer et al., but similar to the prevalence reported by Kahn et al. and by Werner et al. Moreover, nearly all (89%) patients with prior CABG had a CTO, which is higher than the prevalence reported by Fefer et al. for prior CABG patients (54%). One potential explanation may be greater CTO burden in this group prior to CABG; however, an alternative explanation may be the rapid progression of proximal disease with subsequent occlusion of the bypassed vessels (13,14).

Approximately half of the CTO lesions in our study were located in the RCA territory with the majority in the proximal and mid-vessel segments of the coronary vasculature. This is similar to what has been reported in other populations, in which RCA CTOs account for 47% to 64% of all CTO lesions; moreover, more than half of these occlusions are located within the proximal or mid coronary artery segment (1–4).

Similar to prior studies (1,15), patients with CTOs in our cohort were more likely to undergo CABG compared to non-CTO patients (30% vs. 16%, p<0.001), which is consistent with the superior clinical outcomes of CABG compared to PCI among patients with advanced multivessel coronary artery disease (16). In contrast to prior studies, the rate of PCI to any vessel in patients with a CTO was comparable to that of patients without a CTO (50% vs. 53%, p=0.48). The CTO PCI attempt rate in our population (15% and 30% for patients with and without prior CABG, respectively) is significantly higher than the attempt rate reported in prior studies (10%–13.6%) (1,5). This is likely related to (a) the high prevalence of CTO in our population; (b) high cardiac and non-cardiac disease burden of the study patients; and (c) local expertise in treating CTOs. Our study did not perform longitudinal follow-up to detect long-term outcomes post PCI, however, successful CTO PCI has been associated with significant improvements in angina and left ventricular ejection fraction as well as a reduced need for subsequent CABG (17,18). A decision to proceed with CTO PCI should always take into account the risk for complications (7). CTO PCI success rates were lower among prior CABG patients, consistent with a recent report from a multicenter CTO PCI registry (19).

Limitations

Our study has important limitations. Nearly all patients were men (as expected in a veteran population) and the study findings may not be extrapolated to women. Clinical outcomes and improvement in symptoms related to management chosen are not reported, therefore no conclusion can be made on the effect of increased percutaneous revascularization rates of CTOs in this population. Moreover, coronary revascularization (with either PCI or CABG, including CTO PCI) carries risks for complications that should be carefully weighed against the potential benefits. The external validity of our study findings may be limited by the wide variability in the CTO attempt and success rates among various institutions and various populations.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that in a contemporary cohort of veterans referred for cardiac catheterization, nearly one in three non-CABG patients with significant CAD were found to have a CTO. Compared to patients without a CTO, CTO patients had more comorbidities, were more likely to undergo CABG, but were equally likely to undergo PCI to any vessel. CTO PCI was associated with high success and low complication rates.

Table III.

Published studies reporting the prevalence of coronary chronic total occlusions.

| Country | CTO prevalence among CAD patients without prior CABG | CTO prevalence among prior CABG patients | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fefer et al.(1) | Canada | 18.4% | 54% |

| Kahn et al.(2) | USA | 35% | NR |

| Werner et al.(4)* | Germany | 33% | NR |

| Christofferson et al.(3)† | USA | 52% | NR |

| Present study | USA | 31% | 89% |

CABG=coronary artery bypass graft; CAD=coronary artery disease (≥50% stenosis in ≥1 vessel); CTO=chronic total occlusion; NR=not reported

In patients presenting with stable angina

CAD defined as ≥70% stenosis in ≥1 vessel

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- CABG

coronary artery bypass graft

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- CHF

congestive heart failure

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- CTO

chronic total occlusion

- CVA

cerebrovascular accident

- ISR

in-stent restenosis

- LAD

left anterior descending artery

- LCx

left circumflex artery

- LVEF

left ventricular ejection fraction

- MACE

major adverse cardiac event

- MI

myocardial infarction

- OM

obtuse marginal artery

- PCI

percutaneous coronary intervention

- RCA

right coronary artery

- TIMI

Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction

Footnotes

Disclosures:

Dr. Jeroudi: none

Dr. Alomar: none

Dr. Michael: Cardiovascular Training Grant from the National Institutes of Health Award Number T32HL007360.

Dr. El Sabbagh: none

Dr. Patel: none

Dr. Mogabgab: none

Dr. Fuh: none

Dr. Sherbet: none

Dr. Lo: none

Ms. Roesle: none

Dr. Rangan: none

Dr. Abdullah: none

Dr. Hastings: none

Dr. Grodin: none

Dr. Banerjee: Speakers’ Bureau for St. Jude Medical Center, Medtronic Corp., and Johnson & Johnson; research grant from Boston Scientific.

Dr. Brilakis: consulting fees/speaker honoraria from St Jude Medical, Terumo, Janssen, Sanofi, Asahi, Abbott Vascular, and Boston Scientific; research support from Guerbet; spouse is an employee of Medtronic

References

- 1.Fefer P, Knudtson ML, Cheema AN, Galbraith PD, Osherov AB, Yalonetsky S, Gannot S, Samuel M, Weisbrod M, Bierstone D, Sparkes JD, Wright GA, Strauss BH. Current perspectives on coronary chronic total occlusions: the Canadian Multicenter Chronic Total Occlusions Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(11):991–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kahn JK. Angiographic suitability for catheter revascularization of total coronary occlusions in patients from a community hospital setting. Am Heart J. 1993;126(3 Pt 1):561–4. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(93)90404-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christofferson RD, Lehmann KG, Martin GV, Every N, Caldwell JH, Kapadia SR. Effect of chronic total coronary occlusion on treatment strategy. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95(9):1088–91. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.12.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Werner GS, Gitt AK, Zeymer U, Juenger C, Towae F, Wienbergen H, Senges J. Chronic total coronary occlusions in patients with stable angina pectoris: impact on therapy and outcome in present day clinical practice. Clin Res Cardiol. 2009;98(7):435–41. doi: 10.1007/s00392-009-0013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grantham JA, Marso SP, Spertus J, House J, Holmes DR, Jr, Rutherford BD. Chronic total occlusion angioplasty in the United States. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2(6):479–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abbott JD, Kip KE, Vlachos HA, Sawhney N, Srinivas VS, Jacobs AK, Holmes DR, Williams DO. Recent trends in the percutaneous treatment of chronic total coronary occlusions. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97(12):1691–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel VG, Brayton KM, Tamayo A, Mogabgab O, Michael TT, Lo N, Alomar M, Shorrock D, Cipher D, Abdullah S, Banerjee S, Brilakis E. Incidence of Angiographic Success and Procedural Complications in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Chronic Total Occlusion Interventions: A Weighted Meta-Analysis of 18,061 Patients from 65 Studies. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2012.10.011. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson CA, Jayne JE, Robb JF, Friedman BJ, Kaplan AV, Hettleman BD, Niles NW, Lombardi WL. Retrograde techniques and the impact of operator volume on percutaneous intervention for coronary chronic total occlusions an early U.S. experience. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2(9):834–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morino Y, Kimura T, Hayashi Y, Muramatsu T, Ochiai M, Noguchi Y, Kato K, Shibata Y, Hiasa Y, Doi O, Yamashita T, Morimoto T, Abe M, Hinohara T, Mitsudo K. In-hospital outcomes of contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with chronic total occlusion insights from the J-CTO Registry (Multicenter CTO Registry in Japan) JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3(2):143–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2009.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michael TT, Karmpaliotis D, Brilakis ES, Fuh E, Patel VG, Mogabgab O, Kirkland BL, Lembo N, Kalynych A, Carlson H, Banerjee S, Lombardi W, Kandzari DE. Procedural Outcomes of Revascularization of Chronic Total Occlusion of Native Coronary Arteries (From a Multicenter United States Registry) Am J Cardiol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.04.008. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galassi AR, Tomasello SD, Reifart N, Werner GS, Sianos G, Bonnier H, Sievert H, Ehladad S, Bufe A, Shofer J, Gershlick A, Hildick-Smith D, Escaned J, Erglis A, Sheiban I, Thuesen L, Serra A, Christiansen E, Buettner A, Costanzo L, Barrano G, Di Mario C. In-hospital outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with chronic total occlusion: insights from the ERCTO (European Registry of Chronic Total Occlusion) registry. EuroIntervention. 2011;7(4):472–9. doi: 10.4244/EIJV7I4A77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boatman DM, Saeed B, Varghese I, Peters CT, Daye J, Haider A, Roesle M, Banerjee S, Brilakis ES. Prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery patients undergoing diagnostic coronary angiography have multiple uncontrolled coronary artery disease risk factors and high risk for cardiovascular events. Heart Vessels. 2009;24(4):241–6. doi: 10.1007/s00380-008-1114-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hwang MH, Meadows WR, Palac RT, Piao ZE, Pifarre R, Loeb HS, Gunnar RM. Progression of native coronary artery disease at 10 years: insights from a randomized study of medical versus surgical therapy for angina. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;16(5):1066–70. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90533-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rupprecht HJ, Hamm C, Ischinger T, Dietz U, Reimers J, Meyer J. Angiographic follow-up results of a randomized study on angioplasty versus bypass surgery (GABI trial). GABI Study Group. Eur Heart J. 1996;17(8):1192–8. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aziz S, Stables RH, Grayson AD, Perry RA, Ramsdale DR. Percutaneous coronary intervention for chronic total occlusions: improved survival for patients with successful revascularization compared to a failed procedure. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2007;70(1):15–20. doi: 10.1002/ccd.21092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohr FW, Morice MC, Kappetein AP, Feldman TE, Stahle E, Colombo A, Mack MJ, Holmes DR, Jr, Morel MA, Van Dyck N, Houle VM, Dawkins KD, Serruys PW. Coronary artery bypass graft surgery versus percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with three-vessel disease and left main coronary disease: 5-year follow-up of the randomised, clinical SYNTAX trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9867):629–38. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60141-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joyal D, Afilalo J, Rinfret S. Effectiveness of recanalization of chronic total occlusions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am Heart J. 2010;160(1):179–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borgia F, Viceconte N, Ali O, Stuart-Buttle C, Saraswathyamma A, Parisi R, Mirabella F, Dimopoulos K, Di Mario C. Improved cardiac survival, freedom from mace and angina-related quality of life after successful percutaneous recanalization of coronary artery chronic total occlusions. Int J Cardiol. 2012;161(1):31–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Michael TT, Karmpaliotis D, Brilakis ES, Abdullah SM, Kirkland BL, Mishoe KL, Lembo N, Kalynych A, Carlson H, Banerjee S, Lombardi W, Kandzari DE. Impact of prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery on chronic total occlusion revascularisation: insights from a multicentre US registry. Heart. 2013 doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-303763. published online before print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]