Abstract

Correlational studies consistently report relationships between childhood trauma (CT) and most personality disorder (PD) criteria and diagnoses. However, it is not clear whether CT is directly related to PDs or whether common familial factors (i.e., shared environment and/or genetic factors) better account for that relationship. The current study used a co-twin control design to examine support for a direct effect of CT on PD criterion counts. Participants were from the Norwegian Twin Registry (N = 2,780), including a subset (n = 898) of twin pairs (449 pairs, 45% monozygotic [MZ]) discordant for CT meeting DSM–IV Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Criterion A. All participants completed the Norwegian version of the Structured Interview for DSM–IV Personality. Significant associations between CT and all PD criterion counts were detected in the general sample; however, the magnitude of observed effects was small, with CT accounting for no more than approximately 1% of variance in PD criterion counts. A significant, yet modest, interactive effect was detected for sex and CT on Schizoid and Schizotypal PD criterion counts, with CT being related to these disorders among women but not men. After common familial factors were accounted for in the discordant twin sample, CT was significantly related to Borderline and Antisocial PD criterion counts, but no other disorders; however, the magnitude of observed effects was quite modest (r2 = .006 for both outcomes), indicating that the small effect observed in the full sample is likely better accounted for by common genetic and/or environmental factors. CT does not appear to be a key factor in PD etiology.

Keywords: trauma, personality disorders, co-twin control analysis, stress, twin study

Stressful and potentially traumatic life events have been implicated in theories of psychopathology etiology and maintenance (Cicchetti & Cohen, 1997; Linehan, 1993). Exposure to potentially traumatic events during childhood has been related to a number of personality disorder (PD) diagnoses and symptoms (Battle et al., 2004), with Borderline PD receiving the most empirical attention. For example, individuals with clinical or subclinical Borderline PD symptoms are more likely to endorse having experienced childhood abuse compared to nonclinical controls (Bandelow et al., 2005; Laporte, Paris, Guttman, & Russell, 2011; Sansone, Hahn, Dittoe, & Wiederman, 2011). Additionally, etiologic theories of Borderline PD highlight the importance of the role of childhood trauma (CT; Linehan, 1993).

Associations between CT and other PDs also have been documented. For example, childhood maltreatment and abuse are related to Schizotypal PD symptoms (Berenbaum, Thompson, Milanek, Boden, & Bredemeier, 2008; Powers, Thomas, Ressler, & Bradley, 2011), specifically paranoia and unusual perceptual experiences (Steel, Marzillier, Fearon, & Ruddle, 2009). Childhood abuse and witnessing domestic violence have been associated with greater self-reported antisocial behaviors in adolescence (Sousa et al., 2011) and Antisocial PD symptoms in adulthood (Bierer et al., 2003). Other studies have reported broad associations between childhood abuse and the majority of categories of PD symptoms (Battle et al., 2004; Tyrka, Wyche, Kelly, Price, & Carpenter, 2009), even when participants were selected on the basis of having no history of Axis I psychopathology (Grover et al., 2007). Furthermore, childhood abuse and maltreatment are prospectively related to a range of PD symptoms and diagnoses (Cohen, Crawford, Johnson, & Kasen, 2005; Johnson, Cohen, Brown, Smailes, & Bernstein, 1999).

It is tempting to assume that the observed associations between CT and PDs are causal. Although associations have been well documented, a direct effect of CT on PDs has not been established. An alternative explanation is that common mechanisms explain significant covariation between CT and features of PDs (Chapman, Leung, & Lynch, 2008; New et al., 2009). The observed relationship between CT and PDs could also result from common environmental factors (e.g., stressful family environments) and/or shared genetic factors that predispose to both (Button, Scourfield, Martin, Purcell, & McGuffin, 2005; McGuigan & Pratt, 2001; Sartor et al., 2012). Indeed, likelihood of exposure to traumatic events is moderately influenced by genetic factors (Kendler & Baker, 2007), and it is possible that some of these same factors play a role in the development of PDs. Unique environmental influences may also play a role in the CT – PD relationship (e.g., impact of parental reactions on the trauma-exposed child; Nugent, Ostrowski, Christopher, & Delahanty, 2007). Individuals with PDs compared to those without PDs may also be more likely to report a history of CT because of greater negative emotionality, which may bias retrospective reporting (Hardt & Rutter, 2004).

Genetically informative samples consisting of twins who are discordant for CT may provide some insight into the role of CT in PDs, given that shared genetic and environmental factors may be accounted for statistically (Kendler & Campbell, 2009). For example, as traumatic events have been shown to correlate with multiple family background risk factors that are shared by twins (e.g., interpersonal loss, family discord, economic adversity), these factors are statistically controlled for in this model. Without sufficient control in epidemiological samples, which necessitate the measurement of all confounding factors, some of which are unknown, the clustering of traumatic events would likely serve to overestimate the association between CT and PDs. In the one study to our knowledge that addresses trauma and PDs using this design, Bornovalova and colleagues (2013) found that the relationship between childhood abuse and adult Borderline PD traits was likely noncausal and better accounted for by genetic factors. However, this study utilized a questionnaire to assess Borderline traits and did not assess a full range of CT events or PD categories. In fact, the heterogeneity of the assessment and definition of CT in the literature more broadly is problematic. Most notably, many studies fail to assess DSM-IV PTSD Criterion A for trauma exposure (Battle et al., 2004), resulting in a variable that could be assessing stressful life events or negative aspects of the family environment more generally. Past research also focuses largely on child maltreatment and abuse, without assessment or inclusion of other forms of CT that fall within the scope of DSM-IV Criterion A events (Grover et al., 2007). The current investigation sought to address several outstanding limitations of the existing literature by utilizing a genetically informed sample, employing a conservative definition of CT (i.e., DSM-IV PTSD Criterion A), allowing for inclusion of a broad range of CT event types, and using a clinical interview to assess CT and PD criterion counts.

The first aim of the current study was to detect and quantify an association between CT and PD criterion counts in a large sample of adult Norwegian twins obtained from the Norwegian Twin Registry (NTR). It was hypothesized that CT would evidence significant associations with PD criterion counts, above and beyond the effects of age, education level, and participant sex. Given that past studies consistently evidence sex differences in PD prevalence and expression (Torgersen, Kringlen, & Cramer, 2001; Verona, Sprague, & Javdani, 2012), we also evaluated an interaction between CT and participant sex in relation to PD criterion counts. The second aim of the study was to clarify the nature of an association between CT and PD criterion counts in a sample of twins discordant for CT. Specifically, we aimed to evaluate whether CT exerted a direct (i.e., potentially causal) or indirect (i.e., better accounted for by shared environmental and/or genetic factors) effect on PD criterion counts.

Method

Sample and Assessment Method

The Norwegian National Medical Birth Registry, established on January 1, 1967, receives mandatory notification of all live births. The NTR identified and recruited twins from the registry, with participants completing questionnaire studies in 1992 (including twins born between 1967 and 1974) and 1998 (including twins born between 1967 and 1979). Of the 6,442 eligible twins that agreed to be contacted again after the second questionnaire, approximately 44% (2,794 twins) participated in an interview study initiated in 1999 (Tambs et al., 2009). This sample also included 68 twin pairs who had not completed the second questionnaire study, but were still recruited (due to technical problems). Data for the current investigation included all participants who completed the interview study and had complete data on PD criterion counts and CT (N = 2,780). This included a subset (n = 616) of twin pairs (46% monozygotic [MZ]) that were discordant for CT. Participants in the general sample (63.5% women) had a mean age of 28.2 (SD = 3.9) at the time of the interview and reported approximately 14.9 years of education (SD = 2.6).

Approval was received from The Norwegian Data Inspectorate and the Regional Ethical Committee approved the study. All participants provided written informed consent. Interviewers were primarily senior clinical psychology graduate students at the end of their 6-year training course (including at least 6 months of clinical practice; 75%) with the remainder (25%) being experienced psychiatric nurses, with the exception of two medical students. The interview training, conducted by one psychiatrist and two psychologists, consisted of a formal presentation on personality disorders, in-class demonstrations of the interview, multiple supervised role plays and test interviews, and group discussion of possible problems and scoring issues. The interviews, mostly face-to-face, were carried out between June, 1999 and May, 2004. For practical reasons, 231 interviews (8.3%) were done by phone. A different interviewer interviewed each twin in a pair.

Assessment of PDs

A Norwegian version of the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality (SIDP-IV; Pfohl, Blum, & Zimmerman, 1995), a comprehensive semistructured diagnostic interview, was used to assess all 10 DSM-IV PDs. The SIDP-IV has been successfully used in previous large-scale studies in Norway (Helgeland, Kjelsberg, & Torgersen, 2005; Torgersen et al., 2001). The SIDP-IV contains nonpejorative questions organized into topical sections rather than by individual PD to improve interview flow, and uses the “5-year rule,” meaning that behaviors, cognitions, and feelings that predominated for most of the past 5 years are judged to be representative of an individual's personality. Each DSM-IV criterion is scored on a 4-point scale (0 = absent, 1 = subthreshold, 2 = present, or 3 = strongly present). Only the A criterion was assessed for Antisocial PD, given the 5-year assessment timeframe (i.e., Criterion C—presence of conduct disorder prior to age 15— was not assessed).

Given the low base rate of PDs, ordinal symptom counts were created that reflect the number of positively endorsed criteria for each disorder. Results from multiple threshold tests of these 10 PDs indicate that the four response options scored as successive integers represent increasing levels of “severity” on a single continuum of liability (Reichborn-Kjennerud et al., 2007; Torgersen et al., 2008). Because few individuals endorsed (scored 2 or greater) most of the criteria for individual PDs, high criterion counts were infrequent. These low frequency, high symptom counts were collapsed so that variation for all PDs was represented as six ordinal categories. This approach has been successfully utilized in past research using the current sample (Reichborn-Kjennerud et al., 2007). Previous studies using the current data have reported high interrater reliability (range of intraclass correlations for endorsed criterion counts = .81–.96) for the assessed PDs obtained by two raters (one psychologist and one psychiatrist interview trainer) scoring 70 audiotaped interviews (Kendler et al., 2008).

Assessment of CT

A Norwegian computerized version of the Munich-Composite International Diagnostic Interview (M-CIDI; (Wittchen & Pfister, 1997), a comprehensive structured diagnostic interview assessing Axis I diagnoses, was administered. The M-CIDI has good test—retest and interrater reliability (Wittchen, 1994; Wittchen, Lachner, Wunderlich, & Pfister, 1998). In the PTSD module of the M-CIDI, participants were asked if they had personally experienced or witnessed any of the following traumas: 1) a terrible experience at war, 2) serious physical threat (with a weapon), 3) rape, 4) sexual abuse as a child, 5) a natural catastrophe, 6) a serious accident, 7) being imprisoned, taken hostage, or kidnapped, or 8) another event. We defined CT as an event occurring before the age of 17 that met DSM-IV PTSD Criteria A1 (i.e., “the person experienced, witnessed, or was confronted with an event or events that involved actual or threatened death or serious injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of self or others) and A2 (i.e., “the person's response involved intense fear, helplessness, or horror”; American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Approximately 17% (n = 467) of the total sample met these criteria.

Individuals' worst CT were: 35.0% childhood sexual assault, 15.8% rape, 13.1% an accident, 12.6% an “other” traumatic event, 10.9% physical threat to oneself, 10.9% witnessing a traumatic event, 1.1% a natural disaster, and 0.5% being held hostage.

Data Analytic Plan

Analyses for the current study were conducted in SAS. First, the association between CT and PD criterion counts was examined in the general sample. A series of linear regression models was conducted, with age, education level, participant sex (1 = male, 2 = female), and CT (1 = no CT, 2 = CT) entered in level 1. To examine potential sex differences in the relationship between CT and PD criterion counts, the interaction of participant sex and CT was entered at level 2. A square root transformation was conducted for all PD criterion counts prior to inclusion in the regression models.

Second, a series of fixed effects regressions was conducted to examine CT–PD criterion count relationships among the subset of twin pairs discordant for CT, with twin pair serving as the fixed between-groups factor. This method allows for statistical control of unobserved between-family variation (e.g., genetic factors, family stressors, parenting style, socioeconomic factors, etc.). The relationships between CT and PD criterion counts were compared in the general and discordant twin samples. Based on such comparison, one may determine whether the observed relationship between CT and PD criterion counts in the general sample is likely direct or indirect (i.e., better accounted for by familial factors). Specifically, if the magnitude of the relationship between CT and PD criterion counts were comparable in the general and discordant twin samples, the effect is likely to be direct. If the relationship is significantly lesser in magnitude or nonexistent in the discordant twin sample, the effect is likely to be indirect, or accounted for by shared familial factors. The current investigation was not sufficiently powered to examine discordant MZ and DZ twin pairs separately, which would allow for speculation regarding whether shared environmental or genetic factors were responsible for observed indirect effects. For a more comprehensive overview of the co-twin control design, see K.S. Kendler et al.(1993). A total of 20 regression models (10 in the full sample, 10 in the discordant twin subsample) were conducted. Bonferroni correction for multiple testing indicated statistical significance at p = .003.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Zero-Order Correlations (General Sample)

See Table 1. Sex was significantly related to CT, with men being more likely to endorse a CT. Men also were more likely to endorse a greater number of criteria for Narcissistic, Antisocial, and Obsessive-Compulsive PDs, while women were more likely to endorse criteria for Schizotypal, Histrionic, Borderline, and Dependent PDs. Age and years of education were significantly related to various PD criterion counts with no particular pattern being observed. CT was significantly, yet modestly, related to a greater number of criteria for all PDs, with the exception of Avoidant PD.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics and Zero-Order Correlations in the Total Sample.

| Variablea | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | Mean (SD) or % | Observed range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sex | 1 | 63.5% women | |||||||||||||

| 2. Age (years) | −.02 | 1 | 28.2 (3.9) | 19–36 | |||||||||||

| 3. Years of education | −.04 | .08** | 1 | 14.9 (2.6) | 9–26 | ||||||||||

| 4. Childhood trauma | −.06** | .00 | − .03 | 1 | 16.8% positive | ||||||||||

| 5. Paranoid PD | .03 | .00 | − .06** | .08** | 1 | .78 (1.15) | 0–5 | ||||||||

| 6. Schizoid PD | −.03 | −.03 | − .08** | .06** | .24** | 1 | .37 (.73) | 0–5 | |||||||

| 7. Schizotypal PD | .04* | .01 | − .11** | .10** | .48** | .36** | 1 | .40 (.81) | 0–5 | ||||||

| 8. Histrionic PD | .04* | −.03 | .02 | .06** | .36** | .11** | .29** | 1 | 1.03 (1.31) | 0–5 | |||||

| 9. Narcissistic PD | −.14** | −.05* | .06** | .09** | .35** | .21** | .28** | .46** | 1 | .87 (1.20) | 0–5 | ||||

| 10. Borderline PD | .06** | −.07** | − .13** | .13** | .44** | .24** | .40** | .43** | .36** | 1 | .98 (1.34) | 0–5 | |||

| 11. Antisocial PD | −.20** | −.10** | − .10** | .10** | .22** | .12** | .18** | .25** | .30** | .37** | 1 | .30 (.76) | 0–5 | ||

| 12. Avoidant PD | .02 | −.02 | − .11** | .03 | .31** | .33** | .33** | .09** | .19** | .33** | .09** | 1 | .93 (1.33) | 0–5 | |

| 13. Obsessive-Compulsive PD | −.08** | .05* | .04* | .11** | .33** | .20** | .27** | .31** | .35** | .29** | .13** | .18** | 1 | 1.89 (1.54) | 0–5 |

| 14. Dependent PD | .08** | −.03 | − .09** | .04* | .30** | .21** | .34** | .29** | .28** | .42** | .13** | .49** | .20** | .75 (1.13) | 0–5 |

Sex coded as 1 = male, 2 = female; Childhood trauma = DSM-IV PTSD Criterion A status for event experienced before age 16 (1 = no childhood trauma history, 2 = childhood trauma history); PD = Personality disorder criterion counts with high counts collapsed, resulting in a possible score from 0-5.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Trauma Exposure and PD Criterion Counts

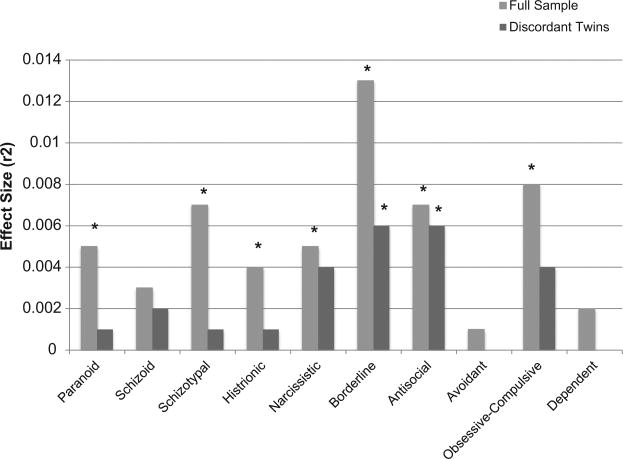

See Table 2 for regression statistics for the main effect of CT on PD criterion counts in the full and discordant twin samples. CT was significantly related to all PD criterion counts in the full sample, after covarying for sex, age, and education level, with the exception of Schizoid, Avoidant, and Dependent PDs. The greatest effects were observed for Borderline (r2 = .013), Obsessive-Compulsive (r2 = .008), Schizotypal (r2 = .007), and Antisocial PDs (r2 = .007; see Figure 1 for a comparison of effect sizes for all PD criterion counts). An interaction between CT and sex was statistically significant for Schizoid (β = .25, t = 2.95, p = .003) and Schizotypal PDs (β = .26, t = 3.16, p = .002). CT was significantly, yet modestly, related to Schizoid and Schizotypal PD criterion counts among women (β = .10, t = 4.10, sr2 = .01, p < .001; and β = .13, t = 5.31, sr2 = .02, p < .001, respectively) but not men (β = −.01, t = −.44,p = .661; and β = .01, t = .42, p = .678, respectively).

Table 2. Childhood Trauma Predicting Personality Disorder Criterion Counts.

| Full samplea (N = 2,780) | Discordant twin sample (n = 616) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| β | SE | t | pb | β | SE | t | pb | |

| Paranoid PD | .07 | .04 | 3.67 | <.001 | .03 | .02 | 1.44 | .149 |

| Schizoid PD | .05 | .03 | 2.81 | .005 | .03 | .01 | 2.08 | .038 |

| Schizotypal PD | .08 | .03 | 4.37 | <.001 | .02 | .02 | 1.25 | .210 |

| Histrionic PD | .07 | .04 | 3.54 | <.001 | .02 | .02 | 1.07 | .285 |

| Narcissistic PD | .07 | .04 | 3.82 | <.001 | .05 | .02 | 2.77 | .006 |

| Borderline PD | .12 | .04 | 6.16 | <.001 | .07 | .02 | 3.76 | <.001 |

| Antisocial PD | .08 | .02 | 4.49 | <.001 | .05 | .01 | 3.47 | <.001 |

| Avoidant PD | .03 | .04 | 1.49 | .135 | .01 | .02 | .70 | .486 |

| Obsessive-Compulsive PD | .09 | .04 | 4.80 | <.001 | .05 | .02 | 2.77 | .006 |

| Dependent PD | .04 | .03 | 2.32 | .020 | .01 | .02 | .63 | .531 |

Note. Childhood trauma coded dichotomously (1 = no childhood trauma history, 2 = childhood trauma history); PD = Personality disorder criterion counts with high counts collapsed, resulting in a possible score from 0–5.

Effect of childhood trauma on PD criterion counts was examined above and beyond the covariates of age, education level, and sex in the full sample.

Statistical significance at p < .003.

Figure 1.

Magnitude of relationship between childhood trauma and personality disorder criterion counts. Note: * p < .003, indicating statistical significance after Bonferroni correction for multiple testing within the indicated sample; analyses in the full sample represent the effect of childhood trauma on criterion counts above and beyond the variance accounted for by participant age, education level, and sex.

Results of the fixed effects regressions indicated that after accounting for family and genetic factors in the discordant twin sample, the relationship between CT and PD criterion counts was quite modest (see Table 2). Overall, the magnitude of the effect of CT on PD criterion counts was quite small prior to accounting for familial liability, not accounting for more than 1% of variance for any given disorder, and upon controlling for familial factors, the relationship between CT and PD criterion counts was essentially nonexistent (see Figure 1 for a comparison of effect sizes in the two samples). The potential exceptions to this pattern are for Borderline and Antisocial PD criterion counts, for which CT appears to account for a slight proportion of unique variation (<1%) beyond shared familial liability.

Discussion

Our first aim was to examine associations between CT and PD criterion counts in the general sample. Consistent with past work, CT was significantly associated with the majority of PD criterion counts, after accounting for sex, age, and education (Battle et al., 2004; Grover et al., 2007; Tyrka et al., 2009). Significant associations were not detected for Schizoid, Avoidant, or Dependent PDs. The strongest associations were detected for Borderline, Obsessive-Compulsive, Schizotypal, and Antisocial PD criterion counts; however, CT accounted for less than 2% of variance in these disorders, even without the inclusion of rigorous covariates (e.g., life stressors, parenting style, etc.). In contrast, trait-level neuroticism accounts for approximately 45% of variance in Borderline PD traits prior to accounting for shared genetic factors (Distel et al., 2009).

The relationship between CT and Schizoid and Schizotypal PD criterion counts varied by sex, with a significant trauma–PD association being detected among women but not men. It is possible that CT is associated with factors promoting a decreased capacity for or interest in close relationships among women. However, the magnitude of effects was consistent with the pattern observed in the full sample, with CT accounting for no more than 2% of variance in these disorders. Prior to controlling for the role of familial factors, CT appears to exert quite modest influence on PD criterion counts.

Second, we sought to explain the nature of the observed effects through the use of a co-twin control design, which relies on comparing the magnitude of effects in the general sample with that observed in twins discordant for CT. The relationships between CT and Antisocial and Narcissistic PDs were comparable in the two samples. It is possible that the very small (i.e., r2 < .01) effect of CT is causal in nature for these disorders. CT also was significantly related to Borderline PD criterion counts in the discordant twin sample; although, the magnitude of the effect in the discordant twins was 50% of that observed in the full sample, suggesting that a substantial portion of the relationship is likely better accounted for by familial factors rather than a direct effect of CT. The role of CT in the remaining PD criterion counts was essentially nonexistent in the discordant twin sample. It does not appear that CT plays a substantial role in the development of PD symptoms.

These findings are at odds with existing theories and clinical intuition regarding PD etiology, particularly in the case of Borderline PD. For example, one review paper on CT in Borderline PD concluded that, “the evidence suggests that childhood trauma should be included in a multifactorial model of BPD” (Ball & Links, 2009). It is worth noting that the studies reviewed by the authors were purely correlational and did not account for the role of familial factors. Marsha Linehan cites CT as a “prototypic invalidating experience” contributing to a biosocial model of Borderline PD etiology, with an entire stage of treatment being devoted to addressing CT and reducing trauma-related behaviors in Dialectical Behavior Therapy (Linehan, 1993). Finally, there has been empirical interest in discovering a biological link between CT and PDs. It has been suggested that CT may lead to neurobiological alterations (e.g., disruption of serotonin function), which in turn may lead to emotional and behavioral deficits in PDs (Lee, 2006). The current findings would suggest that focus on CT as a key risk factor in PDs may not be particularly fruitful. Indeed, this study replicates and extends the only other investigation to our knowledge that addresses CT and PDs using a discordant twin design, in which little to no direct relationship between CT and Borderline PD symptoms was detected (Bornovalova et al., 2013). Investigation of traumatic events in the etiology of Axis I psychopathology using genetically informed designs is needed.

The current project has a number of limitations. First, the base rate of high criterion counts in the current sample was quite low, preventing analysis at the diagnostic level. Future studies utilizing large samples and diverse methodologies are needed. Second, this study was underpowered to examine trauma type or severity in relation to PD criterion counts. Similarly, this study did not have data on familial response to CT. Parental response to trauma may influence the trauma-exposed child's unique environment. For example, parental posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and general parental distress may exert unique influence on children's reactions to trauma (Nugent et al., 2007). Future studies investigating trauma characteristics and responses of the individual and his or her family to CT may be useful. Third, the ethnic and age composition of the current sample is relatively homogenous. Fourth, this study relied on retrospective reporting of CT. However, one would expect this reporting method to inflate the relationship between CT and PD symptoms; therefore, it is possible that the very modest effects detected in the current sample are upwardly biased by recall effects. Fifth, this study did not include a social desirability measure, which may be useful for future investigations in order to account for potential reporting bias. Sixth, this study was underpowered to analyze MZ and DZ twins separately, which would have provided additional information on whether genetic or shared environmental factors accounted for the relationship between CT and PD criterion counts. Finally, this study did not assess for a history of conduct disorder symptoms as related to Antisocial PD. Despite these limitations, the current study provides novel data on the relationship between CT and PD criterion counts.

Correction to Cuthbert and Kozak (2013).

In the article “Constructing Constructs for Psychopathology: The NIMH Research Domain Criteria” by Bruce N. Cuthbert and Michael J. Kozak (Journal of Abnormal Psychology, Vol. 122, No. 3, pp. 928–937. doi: 10.1037/a0034028), the footnote containing the RDoC workgroup members was incomplete. The members of the NIMH RDoC workgroup are as follows: Bruce Cuthbert (chair), Marjorie Garvey, Robert Heinssen, Michael Kozak, Sarah Morris, Kevin Quinn, Daniel Pine, Janine Simmons, Charles Sanislow, Rebecca Steiner, and Philip Wang. External consultants are: Deanna Barch, Will Carpenter, and Michael First.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by NIH Grant MH-068643 and grants from the Norwegian Research Council, the Norwegian Foundation for Health and Rehabilitation, the Norwegian Council for Mental Health, and the European Commission under the program “Quality of Life and Management of the Living Resources” of the Fifth Framework Program (QLG2-CT-2002-01254).

Contributor Information

Erin C. Berenz, Department of Psychiatry, Virginia Institute of Psychiatric and Behavioral Genetics, Virginia Commonwealth University

Ananda B. Amstadter, Department of Psychiatry, Virginia Institute of Psychiatric and Behavioral Genetics, Virginia Commonwealth University

Steven H. Aggen, Department of Psychiatry, Virginia Institute of Psychiatric and Behavioral Genetics, Virginia Commonwealth University

Gun Peggy Knudsen, Division of Mental Health, Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Oslo, Norway.

Ted Reichborn-Kjennerud, Division of Mental Health, Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Oslo, Norway and The Institute of Psychiatry, University of Oslo, Norway.

Charles O. Gardner, Department of Psychiatry, Virginia Institute of Psychiatric and Behavioral Genetics, Virginia Commonwealth University

Kenneth S. Kendler, Department of Psychiatry, Virginia Institute of Psychiatric and Behavioral Genetics and Department of Human and Molecular Genetics, Virginia Commonwealth University

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ball JS, Links PS. Borderline personality disorder and childhood trauma: Evidence for a causal relationship. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2009;11:63–68. doi: 10.1007/s11920-009-0010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandelow B, Krause J, Wedekind D, Broocks A, Hajak G, Ruther E. Early traumatic life events, parental attitudes, family history, and birth risk factors in patients with borderline personality disorder and healthy controls. Psychiatry Research. 2005;134:169–179. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.07.008. doi:10.1016/j .psychres.2003.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battle CL, Shea MT, Johnson DM, Yen S, Zlotnick C, Zanarini MC, Morey LC. Childhood maltreatment associated with adult personality disorders: Findings from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2004;18:193–211. doi: 10.1521/pedi.18.2.193.32777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berenbaum H, Thompson RJ, Milanek ME, Boden MT, Bredemeier K. Psychological trauma and schizotypal personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:502–519. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.3.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierer LM, Yehuda R, Schmeidler J, Mitropoulou V, New AS, Silverman JM, Siever LJ. Abuse and neglect in childhood: Relationship to personality disorder diagnoses. CNS Spectrums. 2003;8:737–754. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900019118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornovalova MA, Huibregtse BM, Hicks BM, Keyes M, McGue M, Iacono W. Tests of a direct effect of childhood abuse on adult borderline personality traits: A longitudinal discordant twin design. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122:180–194. doi: 10.1037/a0028328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Button TM, Scourfield J, Martin N, Purcell S, McGuffin P. Family dysfunction interacts with genes in the causation of antisocial symptoms. Behavior Genetics. 2005;35:115–120. doi: 10.1007/s10519-004-0826-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman AL, Leung DW, Lynch TR. Impulsivity and emotion dysregulation in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2008;22:148–164. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2008.22.2.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Cohen D. Perspectives on developmental psychopathology. In: Luthar SS, Burak JA, Cicchetti D, Weisz JR, editors. Developmental psychopathology: Perspectives on adjustment, risk, and disorder. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1997. pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Crawford TN, Johnson JG, Kasen S. The Children in the Community Study of developmental course of personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2005;19:466–486. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2005.19.5.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Distel MA, Trull TJ, Willemsen G, Vink JM, Derom CA, Lynskey M, Boomsma DI. The five-factor model of personality and borderline personality disorder: A genetic analysis of comorbidity. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;66:1131–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.017. doi:10.1016/j .biopsych.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover KE, Carpenter LL, Price LH, Gagne GG, Mello AF, Mello MF, Tyrka AR. The relationship between childhood abuse and adult personality disorder symptoms. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2007;21:442–447. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2007.21.4.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardt J, Rutter M. Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: Review of the evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:260–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgeland MI, Kjelsberg E, Torgersen S. Continuities between emotional and disruptive behavior disorders in adolescence and personality disorders in adulthood. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1941–1947. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.10.1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Cohen P, Brown J, Smailes EM, Bernstein DP. Childhood maltreatment increases risk for personality disorders during early adulthood. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:600–606. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Aggen SH, Czajkowski N, Roysamb E, Tambs K, Torgersen S, et al. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for DSM–IV personality disorders: A multivariate twin study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65:1438–1446. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.12.1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Baker JH. Genetic influences on measures of the environment: A systematic review. Psychological Medicine. 2007;37:615–626. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Campbell J. Interventionist causal models in psychiatry: Repositioning the mind-body problem. Psychological Medicine. 2009;39:881–887. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Neale MC, MacLean CJ, Heath AC, Eaves LJ, Kessler RC. Smoking and major depression: A causal analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1993;50:36–43. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820130038007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laporte L, Paris J, Guttman H, Russell J. Psychopathology, childhood trauma, and personality traits in patients with borderline personality disorder and their sisters. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2011;25:448–462. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2011.25.4.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R. Childhood trauma and personality disorder: Toward a biological model. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2006;8:43–52. doi: 10.1007/s11920-006-0080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- McGuigan WM, Pratt CC. The predictive impact of domestic violence on three types of child maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2001;25:869–883. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(01)00244-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New AS, Fan J, Murrough JW, Liu X, Liebman RE, Guise KG, et al. A functional magnetic resonance imaging study of deliberate emotion regulation in resilience and posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;66:656–664. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.05.020. doi:10.1016/j .biopsych.2009.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nugent NR, Ostrowski S, Christopher NC, Delahanty DL. Parental posttraumatic stress symptoms as a moderator of child's acute biological response and subsequent posttraumatic stress symptoms in pediatric injury patients. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32:309–318. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfohl B, Blum N, Zimmerman M. Structured Interview for DSM–IVPersonality: SIDP-IV. Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa, Department of Psychology; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Powers AD, Thomas KM, Ressler KJ, Bradley B. The differential effects of child abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder on schizotypal personality disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2011;52:438–445. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Czajkowski N, Neale MC, Orstavik RE, Torgersen S, Tambs K, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on dimensional representations of DSM–IV cluster C personality disorders: A population-based multivariate twin study. Psychological Medicine. 2007;37:645–653. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansone RA, Hahn HS, Dittoe N, Wiederman MW. The relationship between childhood trauma and borderline personality symptomatology in a consecutive sample of cardiac stress test patients. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 2011;15:275–279. doi: 10.3109/13651501.2011.593263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartor CE, Grant JD, Lynskey MT, McCutcheon VV, Waldron M, Statham DJ, Martin NG. Common heritable contributions to low-risk trauma, high-risk trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, and major depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69:293–299. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa C, Herrenkohl TI, Moylan CA, Tajima EA, Klika JB, Herrenkohl RC, Russo MJ. Longitudinal study on the effects of child abuse and children's exposure to domestic violence, parent-child attachments, and antisocial behavior in adolescence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26:111–136. doi: 10.1177/0886260510362883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel C, Marzillier S, Fearon P, Ruddle A. Childhood abuse and schizotypal personality. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2009;44:917–923. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tambs K, Ronning T, Prescott CA, Kendler KS, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Torgersen S, Harris JR. The Norwegian Institute of Public Health twin study of mental health: Examining recruitment and attrition bias. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2009;12:158–168. doi: 10.1375/twin.12.2.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torgersen S, Czajkowski N, Jacobson K, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Roysamb E, Neale MC, Kendler KS. Dimensional representations of DSM–IV cluster B personality disorders in a population-based sample of Norwegian twins: A multivariate study. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38:1617–1625. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torgersen S, Kringlen E, Cramer V. The prevalence of personality disorders in a community sample. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:590–596. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrka AR, Wyche MC, Kelly MM, Price LH, Carpenter LL. Childhood maltreatment and adult personality disorder symptoms: Influence of maltreatment type. Psychiatry Research. 2009;165:281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verona E, Sprague J, Javdani S. Gender and factor-level interactions in psychopathy: Implications for self-directed violence risk and borderline personality disorder symptoms. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2012;3:247–262. doi: 10.1037/a0025945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU. Reliability and validity studies of the WHO– Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): A critical review. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1994;28:57–84. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU, Lachner G, Wunderlich U, Pfister H. Test-retest reliability of the computerized DSM–IV version of the Munich-Composite International Diagnostic Interview (M-CIDI) Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1998;33:568–578. doi: 10.1007/s001270050095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU, Pfister H. DIA-X-Interviews (M-CIDI): Manual fur Screening-Verfahren und Interview; InterviewheftLangsschnittuntersuchung (DIA-X-Lifetime); Erganzungsheft (DIA-X lifetime); InterviewheftQuerschnittuntersuchung (DIA-X 12 Monate); Erganzungsheft (DIA-X 12 Monate); PC-ProgrammzurDurchfuhrung des Interviews (Langs-und Querschnittuntersuchung); Auswertungsprogramm. Frankfurt, Germany: Swets & Zeitlinger; 1997. [Google Scholar]