Abstract

Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) plays a critical role in the pathophysiology of ovarian cancers. Previous studies have shown that LPA stimulates the proliferation of ovarian cancer cells via Gα12. The present study utilizing Protein/DNA array analyses of LPA-stimulated HeyA8 cells in which the expression of Gα12 was silenced, demonstrates for the first time that Gα12-dependent mitogenic signaling by LPA involves the atypical activation cAMP-response element binding protein (CREB). Results indicate that the robust activation of CREB by LPA is an early event that can be monitored by the phosphorylation of SER133 of CREB as early as 3 minutes. The findings that the expression of the constitutively activated mutant of Gα12 stimulates CREB even in the absence of LPA in multiple ovarian cancer cell lines confirms the direct role of Gα12 in in the activation of CREB. This is further substantiated by the observation that the silencing of Gα12 drastically attenuates LPA-stimulated phosphorylation of CREB. Our results also establish that LPA-Gα12-dependent activation of CREB is through a cAMP-independent, but Ras-ERK-dependent mechanism. More significantly, our findings indicate that the expression of the dominant negative S133A mutant of CREB leads to a reduction in LPA-stimulated proliferation of HeyA8 ovarian cancer cells. Thus, results presented here demonstrate for the first time that CREB is a critical signaling node in LPA-LPAR and Gα12/gep proto-oncogene stimulated oncogenic signaling in ovarian cancer cells.

Keywords: LPA, Gα12, Ovarian Cancer, Oncogene, CREB

INTRODUCTION

Ovarian cancer remains as the most fatal gynecological cancers in the world with a five-year survival rate of only approximately 45% [1]. This is primarily due to our poor understanding of the disease in addition to the asymptomatic nature of this cancer in the early stages. In this context, the identification of the lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) as a novel “ovarian cancer activating factor” present in ascetic fluid samples from ovarian cancer patients is a highly significant finding [2, 3] that led to the characterization of LPA as a potential biomarker for ovarian cancers [4–7] in addition to being considered as a as well as a possible therapeutic target for ovarian cancers [8–11].

LPA is known to elicit its diverse cellular responses by stimulating specific set of heterotrimeric G proteins via a distinct family of G protein coupled receptors [12–15]. Studies from several laboratories, including ours, have shown that LPA plays a crucial role in the progression, if not in the genesis, of ovarian cancer [8, 13, 16–20]. We have previously shown that LPA stimulates the proliferation of ovarian cancer cells through GNA12, the gep proto-oncogene, Gα12 [19]. Our previous study, using a model system that utilizes a panel of ovarian cancer cells in which the expression of Gα12 was stably silenced has established the critical role of Gα12 in LPA-mediated oncogenic proliferation of ovarian cancer cells [19]. Therefore, our present study is focused on defining whether the mitogenic pathways stimulated by LPA via Gα12 involve any novel, thus far uncharacterized, signaling pathway(s). Towards this goal, we carried out a Protein/DNA array analysis using LPA-stimulated, but Gα12-silenced, HeyA8 (shGα12-Hey8A) cells. Our results presented here demonstrate that LPA stimulates the potent activation of CREB via the proto-oncogene Gα12 by stimulating the phosphorylation of Ser133 of CREB, leading to activation of CREB, which has been implicated in ovarian cancer cell proliferation [21]. We also show that the activation of CREB by LPA is very rapid that can be observed at least as early as 3 minutes following LPA-treatment. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the expression of the constitutively activated mutant of Gα12 stimulates the phosphorylation of CREB even in the absence of LPA, whereas silencing of Gα12 abrogates LPA-stimulated activation of CREB. Our results further establish that LPA-mediated activation of CREB via Gα12 is through a cAMP-independent mechanism involving a Ras-ERK-dependent signaling pathway. More importantly, we also show that the expression of the dominant negative S133A mutant CREB leads to an attenuation of LPA-stimulated proliferation of ovarian cancer cells. Taken together with the previous finding that the LPA-Gα12 signaling axis is critically involved in ovarian cancer cell proliferation, our present study unravels a unique Gα12-dependent mechanism through which LPA signaling converges on CREB to stimulate the proliferation of ovarian cancer cells.

METERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, Plasmids, and Transfections

The ovarian cancer cell lines SKOV3, and HeyA8 and OVCAR-3 were were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Cellgro, Manassas, VA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gemini Bio-Products, West Sacramento, CA), 50 units / mL penicillin, and 50 µg/mL streptomycin at 37° C in a 5 % CO2 incubator as previously described [20]. LPA was obtained from (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL). It was dissolved into 20 mM stock solutions in sterile water, and stored at −20°C until use. shRNA-mediated silencing of Gα12 were carried out according to previously published methods [19]. Briefly, pLKO.1 vectors encoding a set of human shRNA targeting Gα12 (RHS4533-NM_007353) and the control shRNA-vector were obtained from Open Biosystems (Huntsville, AL). SKOV3, HeyA8, and OVCAR3 cells were transfected with pLKO.1-shRNA /Gα12 or pLKO.1 vector control, respectively using Amaxa Nuclearfector II system. To select for stably transfected shRNA-Gα12 cell colonies, puromycin (2 µg/ml; MP Biomedicals, Solon, Ohio) was added 24 hours post-transfection. Single clones were scored and the silencing of Gα12 expression was determined by immunoblot analysis. pCMV Vectors encoding wild-type CREB and CREBS133A mutant constructs (631925) were obtained from Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA. The transfection studies presented here were carried out using an Amaxa Nucleofector II system (Lonza, Walkersville, MD) using the manufacture’s protocol for the respective cell types.

Protein/DNA array

HeyA8 cells that were stably expressing either shRNA directed against Gα12 or vector backbone alone (pcDNA3) were plated at a density of 1.5 × 106 cells on 100mm plates. The cells were allowed to adhere for approximately 8 hours, then washed thrice with PBS, and then placed in serum-free media. The cells were left in serum-free media overnight. The following day, the cells were either treated with 20 µM of LPA (one group of vector control cells and the stably silenced Gα12 cells) or left in serum-starvation conditions. The cells were incubated for 16 hours with LPA or left in serum free media for this time. After 16 hours, the cells were lysed and the nuclear extract was obtained using the Affymetrix Nuclear Extraction Kit (Santa Clara, CA) according to the manufacture’s instructions. The nuclear lysate was then analyzed for transcription factor activation using an Affymetrix Combo Protein/DNA Array (MA1215; Santa Clara, CA) according to the manufacture’s instructions. Briefly, nuclear extracts from unstimulated, LPA-stimulated or LPA-stimulated, but Gα12-silenced HeyA8 cells were incubated with biotin-labeled DNA probe encoding the binding motifs of specific transcription factors. The transcription factors/proteins bound to the probes were isolated and the bound probes were released and hybridized to an array membrane containing 345 distinct spots for different transcription factor consensus sites. The hybridized biotin-labeled probe, indicative of the activated transcription factors in the lysates, were identified by streptavidin-HRP based chemiluminescence detection method. The intensities of the spots in each of the arrays were quantified using Carestream Molecular Imaging Software version 5 (Rochester, NY).

qRT-PCR analysis

HeyA8 stably-silenced cell clones 1 through 3 and the vector control cells were plated at 700,000 cells on 100mm plates. The cells were allowed to adhere and grow overnight at 37°C with 5% CO2. The cells were then lysed using the Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit (Valencia, CA) according to the manufacture’s instructions. The quantity of RNA was quantified using an Implen NanoPhotometer (Westlake Village, CA). The integrity of isolated RNA was analyzed using Bio-Rad’s Experion automated electrophoresis system (Hercules, CA) according to the manufacture’s instructions. Two step qRT-PCR was performed by first strand synthesis with SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis, primed with Oligo(dT) from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. All samples were processed at the same time to avoid batch-batch variation. A minus reverse transcriptase (RT) control was also generated for each sample. The cDNA constructs were then stored at −80°C until qRT-PCR was performed. qRTPCR was performed using BioRad’s iQ SYBR green supermix kit (Hercules, CA). qRT-PCR mixtures consisted of 1x SYBR Green, 300 nM of each primer, 1µl of template cDNA and water to 10 µl. The thermal profile for all genes was as follows: 95°C for 3 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 seconds and 58°C for 30 seconds. Ct was determined by single threshold for each well. Each sample was done in triplicate on the plate. Negative RT controls for each stably silenced Gα12 clone and the vector control were also done at the same time. A nontemplate control was also included to ensure there was not primer dimers or template contamination. Six endogenous reference genes: actB, alas1, gusB, hprt, PP1A, and tbp were also amplified during the reaction. PCR was carried out using the following primers:

-

ACTB

FWD: GTCTTCCCCTCCATCGTG

REV: GTACTTCAGGGTGAGGATGC

-

ALAS1

FWD: TCTGCAAAGCCAGTCTTGAG

REV: CCTCCATCGGTTTTCACACTA

-

GNA12

FWD: AAGTCCACGTTCCTCAAGC

REV: CCAAGGAATGCCAAGCTTATC

-

GUSB

FWD: TCGCTCACACCAAATCCTTG

REV: AACAGATCACATCCACATACGG

-

HPRT

FWD: GACCAGTCAACAGGGGACAT

REV: CCTGACCAAGGAAAGCAAAG

-

PP1A

FWD: AGACAAGGTCCCAAAGAC

REV: ACCACCCTGACACATAAA

-

TBP

FWD: TGCACAGGAGCCAAGAGTGAA

REV: CACATCACAGCTCCCCACCA

The reference genes with the most stable expression were chosen for normalization using the geNorm method [22] by obtaining the M value for each reference gene and using the M value to stepwise exclude those with the highest M value until the stepwise inclusion did not contribute to the calculated normalization factor. Quality control for the qRT-PCR reaction involved checking the negative RT samples for a Ct less than 40, the NTC had a Ct less than 38, the positive control had a Ct greater than 30, there was not efficiency greater than 110 or less than 90 and each replicate group Ct had a standard deviation less than 0.20. A melting curve analysis was conducted from 55°C to 90°C with 0.5°C increases per cycle insure there was no mis-annealing or contaminated cDNA in the sample.

cAMP Chemiluminescent Immunoassay

A 96-well plate was used to plate out 1 × 105 HeyA8, SKOV3, and stably-silenced Gα12 HeyA8 cells per well into three treatment groups. The three treatment groups were serum-starved (untreated), LPA (20 µM), and Forskolin (20 µM). Each treatment group had six replicates plated out per cell line. The cells were counted and allowed to adhere overnight. The following day the cells were washed 2 times in serum-free media and then left in serum-free media overnight. The following day, the serum-free media was aspirated off the LPA and Forskolin treatment groups. The cells were then incubated in serum free media that contained either LPA or Forskolin for 10 minutes. The untreated group of each cell line was left in the serum free media. After 10 minutes, all the media was aspirated from the wells and the cells were lysed using the lysis buffer provided by the manufacture. After lysis, cAMP levels were determined using Invitrogen’s cAMP Chemiluminescent Immunoassay Kit (Carlsbad, CA) following the manufacture’s instructions.

Cell proliferation assays

Quantification of cell proliferation was carried out using crystal violet staining according to previously published protocols [19]. Equal number of cells (2.5 × 104) were seeded in 12-well culture dishes overnight, serum-deprived for 24 hours, then stimulated as described above. At the indicated time-point, cells were fixed using 10% formalin (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) dissolved in PBS for 10 minutes. Triplicate samples were fixed in this manner immediately before stimulation (0 hour) and at 24, 48, and 72-hours. After fixation, all of the samples were stored in sterile PBS at 4°C. At the conclusion of the experiment, the fixed samples were stained with 0.1 % crystal violet (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 6 hours. The samples were then washed extensively to remove excess dye, and dried overnight. The cell-associated dye was then extracted by incubation with 1 mL acetic acid (Fisher Scientific) for 60 seconds.

Immunoblot analysis

Immunoblot analyses with specific antibodies were carried out following the previously published procedures [19, 20]. The antibodies that were used for immunoblot analyses of Ser133-phospho-CREB (9198), CREB (9197), MSK1 (3489), phospho-MSK1 (9595), AKT (9272), phospho-AKT (9271), phospho-ERK (9106), phospho-p38MAPK (9211), HA-tag (2367), and GAPDH (2118) antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Boston, MA). Antibodies to ERK (sc-93), p38MAPK (sc-535), and Gα12 antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) were from Ambion, Austin, TX (GAPDH antibody #4300) and Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA (Gα12 # sc-409 and HA-epitope # sc-805). Peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (W401B) and anti-mouse IgG (NA93IV) were purchased from Promega (Madison, WI) and GE Healthcare (Buckinghamshire, UK), respectively.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (La Jolla, CA) by two-tailed student’s t-test with Welch’s correction.

RESULTS

LPA stimulates multiple transcription factors through Gα12

Since our previous studies have shown that LPA stimulates cell proliferation via Gα12 [19], we investigated whether there is any novel, thus far unidentified, Gα12-specific unique transcriptionally-regulated event regulated by LPA. To identify transcription factors potentially activated by Gα12, we stably silenced Gα12 in HeyA8 ovarian cancer cells [19]. First, we verified the silencing of Gα12 in these cells by immunoblot analysis and by quantitative RT-PCR (Figure 1A & B). Clone number 2 showed the highest level of Gα12-silencing and was selected for all the studies presented hereafter. The stably silenced Gα12 HeyA8 cells were subjected to a Protein/DNA interaction array analysis. Of the 345 transcription factors analyzed in this array, 34 transcription factors showed a 5-fold or greater increase in their activation profile, as inferred by the increase in their DNA-binding activity, upon LPA-treatment in a Gα12-dependent manner (Figure 1C; Table 1). It is significant to note here that the DNA-binding activity of these transcription factors were greatly reduced or absent in lysates derived from the cells in which the Gα12 was silenced (Figure 1C middle panel versus bottom panel), indicating that they are activated by LPA via a Gα12-dependent mechanism. Analyzing the previously published physiological roles of these transcription factors [23–59], it can be seen that the aberrant expression and activation of many of the transcription factors identified in our study have previously been associated with the genesis and/or progression of many cancers, including ovarian cancer (Table 2), potentially indicating their importance in LPA-mediated oncogenic signaling.

Figure 1. LPA stimulates the activation of diverse transcription factors via Gα12.

A. Silencing of Gα12 in HeyA8 cells using Gα12-specific shRNA was monitored by immunoblot analysis using lysates of 25 µg protein derived from three distinct clones of Gα12-silenced cells along with cells from vector control clone. B. Gα12-shRNA-HeyA8 clones were analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR for Gα12 expression. The expression levels of Gα12 for each clone in relation to vector control cells are presented in the bar graph. C. Hey cells stably expressing shRNA against Gα12 or the vector alone (non-specific scrambled shRNA vector) were serumstarved overnight. The stably silenced Gα12 cells were treated with 20 µM of LPA for 16 hours along with one group of HeyA8 cells stably-expressing the vector alone. Additionally, one group of the vector control cells was left in serum-free media for the 16-hour treatment period. After the 16-hour treatment, nuclear lysate was obtained from each cell group and analyzed by a Protein/DNA array according to manufacturer’s protocol. Representative array data from two independent experiments are presented. Each spot on the array that corresponds to a specific transcription factor was identified according to manufacturer’s protocol. Transcription factors stimulated by LPA but absent or down-regulated in Gα12-silenced cells are scored. The arrows indicate the spots corresponding to CREB. The profiles of activated transcription factors as indicated by the binding of the respective transcription factors to the DNA-elements printed in the array were analyzed in serum-starved HeyA8 cells (Upper Panel), HeyA8 cells stimulated with LPA (Middle Panel), and LPA-stimulated HeyA8 cells in which the expression of Gα12 was silenced (Lower Panel).

Table 1. LPA-stimulated and Gα12-dependent Transcription Factors in HeyA8 Cells.

Control HeyA8 cell expressing non-specific sh-vector or HeyA8 cells in which Gα12 were stimulated with 20 µM LPA for 16 hrs. Nuclear extracts from these cells along with unstimulated controls were analyzed for the activation of different transcription factors using “Affymetrix Combo Protein/DNA Array” as described under Methods section. Representative array data from two independent experiments are presented here. Each spot on the array, which corresponds to a specific transcription factor, was identified using the template from the user manual. The intensities of the spots were quantified using Carestream Molecular Imaging Software version 5. Transcription factors stimulated by LPA but absent or down-regulated in Gα12-silenced cells were scored, quantified, and tabulated.

| Transcription Factor |

Description | Fold Increase |

% Inhibition by shGα12 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Brn-3 | Brain-specific homeobox/POU domain protein 3 | 27.18 | 100 |

| 2 | AP-2 | AP-2 family of transcription factors | 21.08 | 100 |

| 3 | CEBP | CCAAT/enhancer binding protein | 15.99 | 100 |

| 4 | LyF | Ets-1 interacting transcription factor | 15.78 | 100 |

| 5 | MDBP | Methylated DNA-binding protein | 15.78 | 100 |

| 6 | GATA | Globin transcription factor | 12.77 | 100 |

| 7 | CREB | cAMP response element-binding protein | 12.31 | 100 |

| 8 | SMAD-3/4 | Sma-and Mad-related protein-3/4 | 11.74 | 100 |

| 9 | E4BP-4 | b-Zip family of transcription factor/ Nuclear Factor, interleukin 3 regulated | 11.07 | 100 |

| 10 | PRE | Progestereone Response Element binding protein | 10.72 | 100 |

| 11 | RREB | Ras-responsive element-binding protein | 10.54 | 100 |

| 12 | Stat-1 | Signal transducers and activators of transcription 1 | 10.15 | 100 |

| 13 | NFIL-2 | b-Zip family of transcription factor/Nuclear Factor, interleukin 2 regulated | 10.14 | 100 |

| 14 | TFIID | Transcription factor IID | 9.79 | 100 |

| 15 | NF-E2 | Nuclear factor erythroid-derived 2 | 9.11 | 100 |

| 16 | XRE | Xenobiotic response element binding protein | 8.62 | 100 |

| 17 | GAS/ISRE | γ-activated site/interferon stimulated response element binding protein | 8.54 | 100 |

| 18 | CdxA/NKK2 | Homeodomain transcription factor | 8.49 | 100 |

| 19 | Pbx1 | pre-B-cell leukemia homeobox 1 binding protein | 7.94 | 100 |

| 20 | Fra-1/JUN | Fos-related antigen/c-Jun | 7.8 | 100 |

| 21 | CBF | C-repeat binding family of transcription factors | 7.75 | 100 |

| 22 | HSE | Heat shock element binding proteins | 7.59 | 100 |

| 23 | Stat-3 | Signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 | 7.57 | 100 |

| 24 | AML-1 | Hematopoetic/leukemia factor | 7.49 | 100 |

| 25 | HFH-8 | Forkhead box F1a(HNF-3/Fkh Homolog-8) | 7.29 | 100 |

| 26 | HINF | Histone nuclear factor | 7.05 | 100 |

| 27 | c-Myb | Transforming oncogene | 6.93 | 100 |

| 28 | E4F/ATF | Activating transcription factor | 6.62 | 100 |

| 29 | TR | Thyroid hormone receptor | 6.52 | 100 |

| 30 | Stat-1/3 | Signal transducers and activators of transcription 1/3 | 6.27 | 100 |

| 31 | IRF-1/2 | Interferon Regulatory Factor | 6.25 | 100 |

| 32 | XBP-1 | X-box binding protein-1 | 6.05 | 100 |

| 33 | Stat-4 | Signal transducers and activators of transcription 4 | 5.91 | 100 |

| 34 | SP-1/ASP | Sp 1 transcription factor | 5.77 | 100 |

Table 2. LPA-responsive and Gα12-dependent Transcription Factors associated with Cancer.

Based on previously published data, at least seventeen of the transcription factors tabulated here have been shown to be either overexpressed or activated in different cancers.

| Transcription Factor |

Cancer | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Brn-3 | Neuroectodermal (70), Neuroblastoma (29), Ovarian (1), Prostate (14), |

| 2 | GATA | Breast, Gastrointestinal (3, 84) |

| 3 | CREB | Lung (61), Myeloid leukemia, Ovarian |

| 4 | SMAD-3/4 | Pancreatic (40), Prostate (38) |

| 5 | RREB | Prostate (51, 86), thyroid, pancreatic, bladder |

| 6 | Stat-1 | Breast (75), Glioblastoma (25), Leukemia (34), Melanoma (62), Ovarian (68) |

| 7 | TFIID | Breast, Lung (73) |

| 8 | NF-E2 | myeloproliferative neoplasms (32) |

| 9 | Pbx1 | Breast (39), Leukemia (2), Ovarian (52), |

| 10 | Fra-1/JUN | Breast (8), Lung, Melanoma (87) Ovarian (26), |

| 11 | Stat-3 | Ovarian (28), Endometrial (7) Pancreatic |

| 12 | HFH-8 | Breast, Lung (60) |

| 13 | c-Myb | Multiple Cancers |

| 14 | E4F/ATF | Colon, Pancreatic |

| 15 | TR | Basal Cell Carcinoma (76), Ovarian (56) |

| 16 | XBP-1 | Colorectal (17), Breast (16, 64), Endometrial (64) |

| 17 | SP-1/ASP | Breast, Colorectal, Ovarian (59) |

Activation of CREB by LPA is Gα12-dependent early signaling event

Our finding that CREB is one of the transcription factors stimulated by LPA via a Gα12-dependent mechanism is quite intriguing and novel. Indeed, Gα12 has never been associated with the stimulation of cAMP or CREB-dependent mitogenic pathways [60, 61]. Taking into account of the recent findings that CREB is overexpressed in ovarian cancer and its suppression leads to a decrease in ovarian cancer cell proliferation [21] and that CREB has been linked to inducing oncogenesis in several different cancer types [62], we focused on investigating the role of CREB in LPA-Gα12-mediated oncogenic proliferation of ovarian cancer cells. Since the Protein/DNA array analysis presented in Figure 1C was carried out with cells that were exposed to LPA for 16 hours, we reasoned that it is of critical importance to clarify whether the activation of CREB by LPA is an early event or an event occurring much later. Our reasoning for clarifying this was if CREB activation occurs early in LPA-mediated signaling, this would indicate CREB activation is more than likely due to immediate downstream signaling of Gα12. However, if CREB activation occurs much later, e.g. after 1 hour, this would potentially indicate CREB-activation via Gα12 is due to a sequential relay of temporal signaling events and thus indirectly activated by Gα12. Therefore, we carried out a time course analysis of LPA-stimulated CREB-activation in HeyA8 cells using Ser133 phosphorylation of CREB as an index of CREB-activation [63]. As shown in Figure 2A, we found the phosphorylation of Ser133 on CREB could be observed from 3 minutes onwards following LPA-stimulation and persisted beyond six hours.

Figure 2. LPA-stimulated activation of CREB is an early event.

A. HeyA8 cells (1 × 106) were stimulated with 20 µM LPA for varying lengths of time as indicated. Lysates from these cells were analyzed by immunoblot for the phosphorylation of CREB on Ser133. The blot was stripped and analyzed for total CREB and GAPDH, as loading controls. B. The phosphorylated levels of CREB were quantified from three independent experiments using HeyA8 cells as shown in the time course in part A.

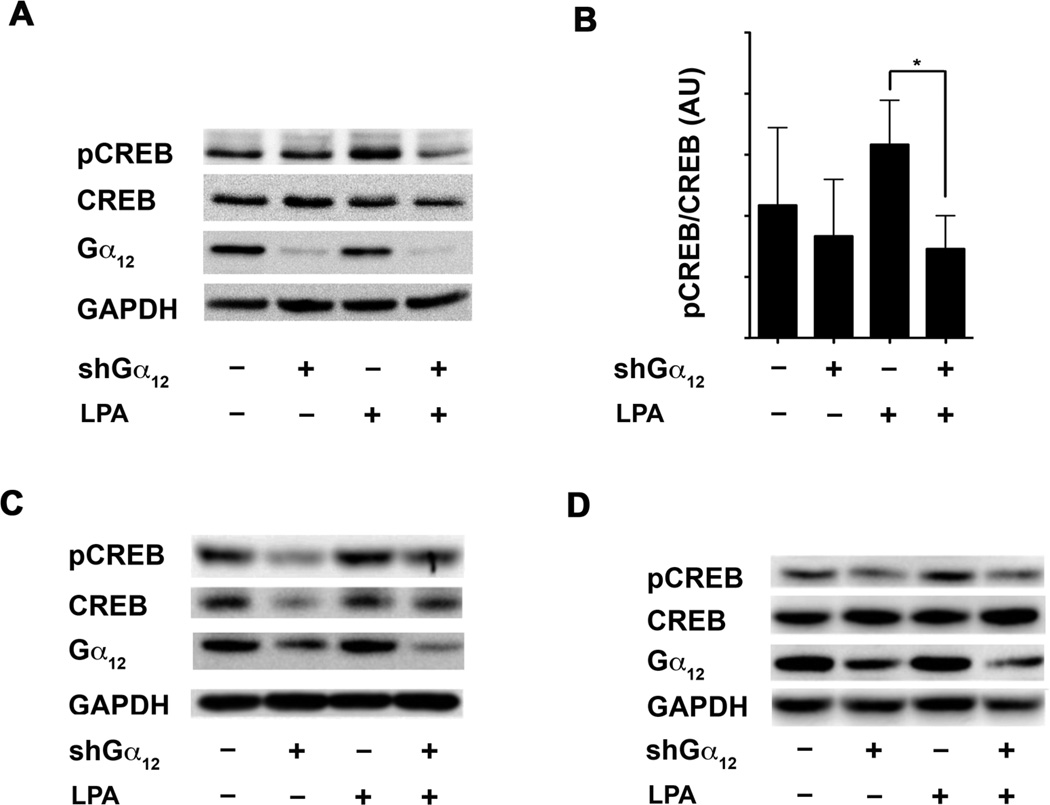

LPA-stimulated phosphorylation of CREB requires Gα12

To further validate that the CREB activation is a Gα12-mediated event, an immunoblot analysis was carried out to test whether the silencing of Gα12 abrogates LPA-stimulated Ser133-phosphorylation of CREB. Our results indicated that the stimulation of the control HeyA8 cells with LPA resulted in the phosphorylation of Ser133 by 3 minutes (Figure 2B, Lane 1 versus Lane 3), whereas silencing of Gα12 led to a drastic reduction in LPA-mediated activation of CREB (Fig. 2B Lane 3 versus Lane 4). Quantification of these results indicated that the silencing of Gα12 attenuated LPA-stimulated phosphorylation of CREB by more than 50% (Fig. 2B, Lower Panel). Similar attenuation of LPA-stimulated phosphorylation of CREB-Ser133 was observed, albeit to a varying extent, in Gα12-silenced-SKOV-3 cells (Fig. 2C), indicating that the observed Gα12- dependent activation of CREB by LPA is not unique to HeyA8 cells alone.

To rule out the possibility that the results obtained were due to a compensatory mechanism induced by the persistent silencing of Gα12 in these cells, we analyzed LPA-stimulated CREB phosphorylation in HeyA8 cells in which the expression of Gα12 was transiently silenced for only 24 hours via Gα12-targeting shRNA. As shown in Figure 2C and 2D, transient silencing of Gα12 led to the abrogation of LPA-stimulated phosphorylation of CREB-Ser133. These results further confirm that the activation of Gα12 by LPA initiates a signaling cascade(s) that leads to the downstream phosphorylation of CREB.

Constitutively activated mutant of Gα12 stimulates the phosphorylation of Ser-133 of CREB

In order to directly demonstrate that the activation of Gα12 is sufficient for the observed Ser133-phosphorylation of CREB, we utilized another approach involving the expression of the constitutively active, GTPase-deficient mutant of Gα12, Gα12Q229L (Gα12QL) in ovarian cancer cell lines. Since the GTPase deficient mutant of Gα12 would be analogous to LPA-activated GTP-bound configuration of Gα12, if Gα12 is truly involved in the activation of CREB, the expression of such a constitutively active mutant should lead to the Ser133-phosphorylation of CREB. Following this rationale, HeyA8, OVCAR3, or SKOV3 cells were transiently transfected with a vector encoding Gα12QL for 48 hours. The lysates from the transfected cells were resolved by SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblot analysis using antibodies specific to Ser133-phosphorylated CREB. Our results indicated that the expression of Gα12QL stimulated a significant increase (> 60 %) in the phosphorylation of CREB in all of the tested cell lines (Fig. 4). These results, together with the data obtained with the use of Gα12-silenced ovarian cancer, confirm that the activation of Gα12 – whether it is through mutational activation or via LPALPAR- mediated activation – plays a determinant role in the activation of CREB.

Figure 4. Activated Mutant of Gα12 stimulates the Phosphorylation of CREB.

A.) 1 × 106 HeyA8, SKOV3, and OVCAR3 cells were transiently transfected with vectors encoding Gα12QL for 48 hours. Lysates from these transfectants were resolved by SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblot analysis using antibodies specific to Ser133-phosphorylated CREB. The same respective blots were stripped and re-probed for total CREB and GAPDH to ensure equal loading. Levels of Gα12 were also probed to ensure expression of the constitutively active mutant. B.) The phosphorylated levels of CREB in relation to total levels of CREB were quantified and presented as bar graph in which the bars represent mean ± SEM (n = 3). An unpaired two-tail t-test with Welch’s correction was performed to determine statistical significance. * p < 0.05.

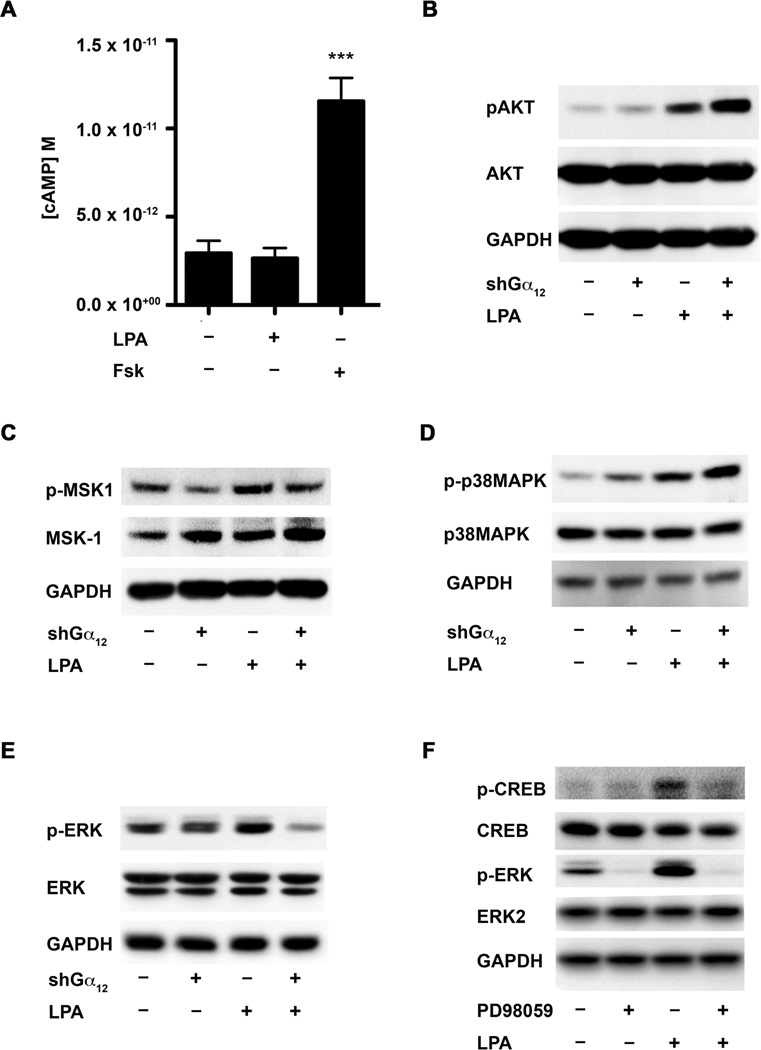

Stimulation of CREB by LPA involves is via cyclic AMP-independent bur ERK-dependent pathway

Canonical signaling involved in the activation of CREB involves the generation of cyclic AMP (cAMP) and subsequent activation of PKA is one of the major pathways known to activate CREB. On the other hand, past studies have shown that Gα12 activation does not lead to the production of cAMP [60, 64]. This led us to hypothesize that LPA activation of CREB was independent of cAMP signaling. To test this hypothesis, we performed a chemiluminescent Immunoassay to determine if LPA signaling and/or LPA-Gα12-dependent signaling activated cAMP in HeyA8 and SKOV3 cells. Briefly, Gα12-silenced HeyA8 or SKOV3 cells were plated and allowed to adhere overnight, then serum-starved overnight and then stimulated with LPA (20 µM) for 10 minutes along with an untreated control group and a positive control of Forskolin (20 µM) treated cells, which activates adenylyl cyclase independent of receptor/G protein coupling, was used as a positive control. Lysates from these cells were analyzed for cAMP levels using a chemiluminescent cAMP-immunoassay. As expected, Forskolin stimulated an increase in cAMP levels in the cells, however LPA-stimulation of these cells failed to elicit any significant changes in cAMP levels (Fig. 5A). Our observation that cAMP-levels were not effected by LPA stimulation pointed to a signaling mechanism independent of cAMP in LPA-Gα12-mediated activation of CREB in these cells.

Figure 5. LPA stimulates the phosphorylation of CREB via cyclic AMP-independent but ERK-dependent pathway.

A. LPA-Gα12-mediated activation of CREB is independent of cAMP-signaling. A 96-well plate was used to plate out 1 × 105 HeyA8 cells per well into three treatment groups. The three treatment groups were [1] serum-starved (untreated), [2] LPA (20 µM), and [3] Forskolin (20 µM) with each treatment group having a six replicates. The cells were counted and allowed to adhere overnight. The following day cells were washed 2-times in serum-free media and left to incubate overnight. The following day, the serum-free media was aspirated off and the cells were treated with either LPA or Forskolin prepared in serum-free media for 10 minutes or cells were treated with with serum-free media alone. After 10 minutes of treatment, the media was aspirated and the cells were lysed using the lysis buffer provided by the manufacturer. After lysis, cAMP levels were determined using a cAMP Chemiluminescent Immunoassay Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantification of the data was done via GraphPad by interpolating the unknowns from a standard curve using the log(inhibitor) vs. response function. *** p = 0.0007.

Control cells expressing non-specific scrambled sh-vector or HeyA8 cells stably expressing shRNA targeting Gα12 cells were serum starved for 16 hours followed by stimulation with 20 µM of LPA for 10 min. The cells were lysed with RIPA buffer and blotted for p-AKT (B), p-MSK-1 (C), p-P38MAPK (D), and p-ERK (E), respectively. The same blot was stripped and re-probed for total protein for AKT (B), MSK-1 (C), P38MAPK (D), ERK (E) and GAPDH. F. To validate whether ERK is activating CREB, a pharmacological inhibitor of the ERK pathway (PD98059) was used. HeyA8 cells (1 × 106) were pre-treated with 10 µM PD98059 for one hour followed by stimulation with 20 µM of LPA for 10 minutes. These cells were lysed and analyzed by immunoblot for phosphorylation of CREB on Ser133, then stripped and re-probed for total CREB and GAPDH to ensure equal loading of protein.

Although CREB can be activated by the phosphorylation of Ser133 by various kinases including the canonical signaling pathways involving cAMP and protein kinase A [65, 66], previous studies have also shown LPA can stimulate the phosphorylation of CREB via cAMP-dependent [67] as well as -independent mechanisms [68]. It has been shown that cAMP-independent Ser133 phosphorylation of CREB can be mediated via AKT or via ERK/p38MAPK-dependent pathways that result in the activation of the kinase MSK1[63]. To identify the candidate pathway that was activating CREB in our system, we first monitored which of these these aforementioned kinases were activated by LPA in a Gα12-dependent manner. The activation profiles of these kinases in response to LPA were analyzed by immunoblot analysis using antibodies specific to the activated, phosphorylated forms of these kinases. Vector control or Gα12-silenced HeyA8 cells (2 × 106) were serum starved and stimulated with 20 µM LPA for 10 minutes. Lysates from these cells were analyzed for the activation of ERK, p38MAPK, or AKT. As shown in Figure 4, LPA-stimulation of HeyA8 cells resulted in the activation of AKT (Fig. 5B), p38MAPK (Fig. 5C), MSK1 (Fig. 5D) and ERK (Fig. 5E) to a varying extent. However, the silencing of Gα12 in these cells abrogated only the activation of ERK (Fig. 5E), suggesting the possible role for ERK in LPA-Gα12-mediated CREB activation. To test whether ERK is truly involved in LPA-mediated activation of CREB, we analyzed Ser133 phosphorylation of CREB in response to LPA in cells treated with PD98059, a potent inhibitor of MEK, the upstream activator of ERK. Immunoblot analyses revealed treatment of cells with PD98059 resulted in significant attenuation of CREB phosphorylation (Fig. 5F), indicating the activation of CREB by LPA in these cells is ERK-dependent.

LPA-Gα12-stimulated phosphorylation of Ser133-CREB involves Ras

Thus far our study has demonstrated LPA-mediated activation of CREB involves Gα12 and ERK and we therefore wanted to determine if Gα12-meidated activation of ERK followed the stereotypical activation of the MAP kinase pathway via Ras. Previous studies have established Ras plays a determinant role in the activation of ERK [69–71]. Furthermore, our laboratory as well as others, has shown Gα12 can activate Ras as well as the Ras-ERK signaling nexus [72–74]. Therefore, due to the well-characterized involvement of Ras in activating ERK and ERK-mediated downstream signaling involved in the direct activation of CREB we tested whether inhibition of Ras led to attenuation of CREB phosphorylation. In addition, we investigated whether any of the other Gα12-responsive GTPases such as CDC42, Rac-1, and RhoA were involved in the activation of CREB. To characterize the involvement of these small GTPases in LPA-Gα12 mediated activation of CREB, HeyA8 cells were transiently transfected with dominant negative mutants of H-Ras- (N17-H-Ras), Rac-1- (N17-Rac-1), CDC42- (N17-CDC42), and RhoA (N19-RhoA)-GTPases with subsequent immunoblot analyses being carried out to analyze the effect of expressing these dominant negative mutants on LPA-stimulated phosphorylation of Ser133-CREB. Our results indicated that the stimulation of CREB by LPA was drastically inhibited by the expression of the dominant negative mutant of Ras (Fig. 6A). In contrast, LPA-stimulated phosphorylation of CREB was not attenuated by the expression of the dominant negative mutants of CDC42, Rac, or RhoA (Fig. 6B). To confirm the specific role of Gα12 in transmitting signals through Ras to stimulate CREB, we analyzed the effect of the dominant negative mutant of Ras on phosphorylation of CREB stimulated by the expression of the constitutively activated Gα12QL mutant on the activation of CREB. Our results indicated that the expression of dominant negative Ras attenuated Gα12QL-stimulated phosphorylation of CREB in two different ovarian cancer cell lines (Fig. 6C), establishing Gα12-mediated activation of CREB is via the Ras-ERK signaling pathway.

Figure 6. LPA and Gα12 stimulated phosphorylation of CREB requires Ras.

A.) 1 × 106 SKOV3 cells were transfected for 48 hours either with vector alone or with dominant-negative mutant HA-RasN17. The cells were serum starved for 16 hours and were then stimulated with 20 µM of LPA for 10 min. These cells were lysed and immunoblotted for phosphorylated CREB (S133). The same blot was stripped and re-probed for total CREB and GAPDH to ensure equal loading. The stripped blots were also probed for the HA-tag to confirm expression of the dominant-negative Ras constructs. The phosphorylated levels of CREB in relation to total levels of CREB were quantified and presented as bar graph in which the bars represent mean ± SEM (n = 3). An unpaired two-tail t-test with Welch’s correction was performed to determine statistical significance. * p < 0.05. B.) 1 × 106 SKOV3 cells were transfected for 48 hours either with vector alone or with dominant-negative mutant HA-CDC42N17 (Upper Panel), HA-RacN17 (Middle Panel), and HA-RhoN19 (Lower Panel), respectively. The cells were serum starved for 16 hours and were then stimulated with 20 µM of LPA for 10 min. These cells were lysed and immunoblotted for phosphorylated CREB (S133). The same blot was stripped and re-probed for total CREB and GAPDH to ensure equal loading. The stripped blots were also probed for the HA-tag to confirm expression of the dominant-negative constructs. C.) SKOV3 cells were transfected with Gα12QL, along with HA-RasN17, or vector alone. These cells were lysed and immunoblotted for phosphorylated CREB (S133). The same blot was stripped and re-probed for total CREB and GAPDH to ensure equal loading. The stripped blots were also assayed for total Gα12, to show expression the Gα12QL construct and for the HA-tag to confirm expression of the dominant-negative Ras construct.

CREB is involved in LPA-mediated ovarian cancer cell proliferation

It is significant to note here that our previous studies have shown that LPA stimulates the proliferation of ovarian cancer cells via Gα12. Similarly, CREB has been shown to be involved in the regulation of ovarian cancer cell proliferation [21]. In conjunction with our results presented here that LPA-Gα12 signaling axis stimulates the phosphorylation of CREB, it can be hypothesized that the activation of CREB plays a crucial role in LPA-mediated proliferation of ovarian cancer cells. To characterize the involvement of CREB in LPA-mediated proliferation we utilized a dominant negative mutant of CREB. The CREB dominant negative mutant was created by mutating serine 133 of CREB to alanine (S133A), which has been well characterized as a dominant negative inhibitor of CREB that exerts its inhibitory effect by sequestering the upstream kinase involved in Ser133-phosphorylation of CREB [75–78].

To test the hypothesis that CREB plays a role in LPA-mediated proliferation, HeyA8 cells were transfected with vectors encoding S133A-mutant CREB or a control vector. After 24 hours, the transfected cells were plated at 2 × 104, allowed to adhere overnight then serum-starved the following day. After serum-starvation the transfected cells were stimulated with 20 µM LPA for the indicated times and proliferation of these cells were quantified following previously published methods [19]. The lysates from these transfected cells were also analyzed for the expression levels of Cyclin A, which is known to be regulated by CREB and as an additional marker of proliferation [79]. The dominant negative inhibitory effect of CREB-S133A was verified by its ability to inhibit Ser-133 phosphorylation of endogenous CREB in these cells. Analysis of the proliferation of these cells indicated that the expression of the dominant negative CREB-mutant reduced the proliferation of ovarian cancer cells by 40 percent compared to both vector control cells (Fig. 7A) with the concomitant analogous reduction in Cyclin A levels (Fig. 7B), thus establishing a role for CREB in LPA-stimulated proliferation of these cells.

Figure 7. LPA-induced proliferation of ovarian cancer cells requires CREB.

A. HeyA8 cells (1 × 106) were transfected for 24 hours either with vector alone or with dominant-negative CREB mutant (S133A). 2.5 × 104 of the transfected cells were seeded in triplicate into 12-well culture dishes and the cells were serum-starved for 16 hours and were then stimulated with 20 µM of LPA. At the indicated time-point, cells were fixed using 10% formalin dissolved in PBS for 10 minutes. Triplicate samples were fixed in this manner immediately before stimulation (0 hour) and at 24, 48, and 72-hours, respectively. The fixed samples were stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 6 hours. The samples were then washed extensively to remove excess dye, and dried overnight. The cell-associated dye was then extracted by incubation with 1 mL acetic acid for 60 seconds and absorbance at 590 nm was quantified (Uppper Panel). To confirm the expression and the dominant-negative inhibitory effect of the S133A-CREB mutant, lysates from S133A-CREB transfectants (CREB-S133A) along with those obtained from vector control cells (pCMV) were subjected to immunoblot analysis using antibodies to CREB and SER133-phospho-CREB respectively. The blot was stripped and reprobed with antibodies to GAPDH to monitor equal loading (Lower Panel). B. The cells were lysed and immunoblotted for Cyclin A (Upper Panel) following which it was stripped and reprobed for total GAPDH to ensure equal loading. The expression levels of Cyclin A in relation to total levels of GAPDH were quantified and presented as bar graph (Lower Panel) in which the bars represent mean ± SEM (n = 3). An unpaired two-tail t-test with Welch’s correction was performed to determine statistical significance. ** p = 0.0018.

DISCUSSION

Although the potential oncogenic role of LPA in ovarian cancer pathophysiology is increasing being realized, its role and the underlying mechanism in promoting ovarian cancer cell proliferation is not fully clarified. In this context, a recent report from our laboratory was one of the first to clearly demonstrate the LPA-LPAR-Gα12 signaling axis specifically induces proliferation in ovarian cancer cells, but not in normal epithelial ovarian cells [19]. Our current study expands our previous finding further by establishing here for the first time that Gα12- dependent proliferative signaling stimulated by LPA involves the activation of CREB. In this study, we were able to show that stimulation with LPA activates the transcription factor CREB in a Gα12-dependent manner by the DNA/protein array based functional assay – which is based on the ability of activated CREB binding to the CRE-containing DNA-fragment printed in the array - as well as Ser133-phosphorylation of CREB (Fig. 1 & 2). Furthermore, by using three different strategies, namely, 1) shRNA-mediated silencing of Gα12-expression (Fig. 1 & 3 A–C, 2) dominant negative mutant-mediated inhibition of receptor-mediated activation of Gα12 (Fig. 3D) and 3) expression of constitutively activated mutant of Gα12 (Fig. 4), we firmly establish that the phosphorylation of Ser133 is indeed mediated by Gα12. Our studies using the dominant negative inhibitory mutant of Gα12 that exerts its inhibitory effect by competing with the endogenous Gα12 [19, 80, 81]in its interaction with the receptor further confirms LPA-LPAR-Gα12 signaling axis involved in Ser133-phosphorylation and subsequent activation of CREB. In addition, our results presented here suggests that this phosphorylations is dependent on Ras, which in turn involves ERK-mediated activation of CREB. Although our present study does not focus on the mechanism by which ERK stimulate the phosphorylation of Ser133 of CREB, it has bee previously shown that ERK-mediated phosphorylation of Ser133 of CREB involves either MAPKAP-K1/RSK2 [82] or MSK1[83]. Relatedly, Figure 5D indicated the silencing of Gα12 does not modulate MSK1 activation; therefore, it is more likely that the phosphorylation of CREB-Ser-133 involves MAPKAP-K1. In fact, our preliminary data indicate that LPAmediated SER-133 phosphorylation of CREB is also sensitive to Ro-318220, which is known to inhibit MAPKAP-K1/RSK2 (Ha and Dhanasekaran, unpublished observation). However, since Ro-318220 can also inhibit other protein kinases such as MSK1, PKC, GSK3, and S6K1 [84], further studies should identify the kinase downstream of ERK in LPA-Gα12-mediated activation of CREB. Finally, we show that inhibition of CREB in ovarian cancer cells leads to a marked decrease in proliferation compared to LPA-stimulated cells. We show that LPA-mediated proliferation involves CREB.

Figure 3. LPA-stimulated phosphorylation of CREB is Gα12-dependent.

A. HeyA8 cells (1 × 106) in which Gα12 was silenced by stable expression of shRNA to Gα12 were stimulated with 20 µM of LPA for 10 minutes or left unstimulated. Vector control HeyA8 cells (1 × 106) were also treated with 20 µM of LPA for 10 minutes as a positive control or left unstimulated, as a negative control. Immunoblots were performed for phosphorylation of CREB on Ser133 The blots were then sequentially stripped and probed for the expressions of CREB, Gα12 and GAPDH. B. The phosphorylated levels of CREB in relation to total levels of CREB were quantified for each group and presented as bar graph in which the bars represent mean ± SEM (n = 3). An unpaired two-tail t-test with Welch’s correction was performed to determine statistical significance. * p < 0.05. C. Similar analysis was carried out in SKOV3 cells in which the expression of Gα12 was silenced by the stable expression of shRNA directed against Gα12. The experiment was repeated 3 times and a representative immunoblot is shown. D. Transient silencing of Gα12 was carried out by transfecting HeyA8 cells with shRNA specific for Gα12 or scrambled shRNA control for 48 hours. These transfectants were stimulated with 20 µM of LPA for 10 minutes or left unstimulated. Immunoblot analysis was carried out to monitor the phosphorylation of Ser133 of CREB. The blot was then sequentially stripped and probed for the expressions of CREB, Gα12 and GAPDH. The experiment was repeated three times and a representative immunoblot is shown.

It is worth noting that this is the first study, to our knowledge, to show CREB is activated by LPA signaling in a Gα12-dependent manner via the Ras-ERK signaling conduit (Fig. 8). The signaling paradigm presented here is consistent with a recent observation that CREB is both overexpressed and active in ovarian cancer patient samples and RNAi-mediated silencing of CREB significantly reduced proliferation of ovarian cancer cells while having no effect on cell death [21]. In addition, our data presented here identifies the potential mechanism underlying the hyperactive CREB levels seen in ovarian cancer patients. Due to the fact that CREB can activate conservatively over 1,000 different genes [63], it is a definite possibility that CREB can induce other phenotypic effects of LPA beside proliferation, including migration, invasion and survival, that warrants future investigation. Although our present study does not focus on the other identified transcription factors stimulated by LPA via Gα12 (Tables 1 & 2), contextual characterization of these transcription may provide further insight to the mechanisms by which Gα12 and LPA signaling contribute to the oncogenesis and progression of ovarian and other cancers. Since Gα12 stimulates the generation and coordination of multiple, often oncogenic, signaling inputs, it is more likely that the transcription factors identified in our array analyses are activated by different branches of the signaling network coordinated by Gα12.

Figure 8. Schematic model for Gα12-dependent activation of CREB.

LPA binds to one or more LPA receptors that activate Gα12 and Gα12 then mediates the activation of ERK1/2 via Ras. Activation of ERK1/2 leads to Ser133-phosphorylation of CREB. CREB, thus activated in an LPA-Gα12 dependent manner, stimulates the proliferation of ovarian cancer cells through the transcriptional activation of proliferation-specific genes. However, the kinase(s) that transmits signals from ERK1/2 to CREB remains to be clarified.

Since the identification of Gα12 as a potential oncogene that can induce neoplastic transformation [85], several studies including ours have shown the ability of Gα12 in regulating multiple growth promoting activities [86]. In this regard, Gα12 acts as a typical oncogene in coordinating the regulation multiple growth-promoting signaling nodes. The findings presented here provide another set of evidence that the aberrant or asynchronous activation of Gα12 by increased levels of LPA could lead to the activation of multiple oncogenic pathways (Table 1 and 2). Although an activating mutation in Gα12 has not been reported in any cancers including ovarian cancer, overexpression as well as hyper-activation of Gα12 has been observed in ovarian cancer cell lines [19]. Therefore it appears that the increased receptor-activation of Gα12 is likely to play an oncogenic role in ovarian cancer pathophysiology. Interestingly, this is in agreement with the earlier findings that led to the characterization of Gα12 as an oncogene in Ewing’s sarcoma cells in which increased expression rather than mutational activation of Gα12 was shown to be the causative factor for oncogenic transformation [85]. At present, we are pursuing studies to test whether an overexpression or activation of Gα12 can be seen in ovarian cancer samples in addition to defining the LPAR(s) that transmits mitogenic signaling via Gα12 and the signaling network coordinated by this system involving the multiple transcription factors identified here in promoting ovarian cancer progression.

Overall, this study conclusively demonstrates silencing Gα12 can attenuate the signaling inputs involved in ovarian cancer cell proliferation and that Gα12-Ras-ERK-dependent signaling leads to activation of the transcription factor CREB, in a cAMP-independent manner. Additionally, our studies also suggest the interesting possibility that the delivery of a minigene or a small molecular inhibitor that could inhibit the LPAR-Gα12 interaction, or delivery of siRNA against Gα12 to ovarian cancer cells could represent a novel way to block the pathogenic proliferation of ovarian and potentially other types of cancers that involve pathological LPA-meditated signaling.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (CA116984, CA123233) and The World Class University project funded by Ministry of Education, Science and Technology Development, S. Korea [No.R32-2008-000-10098-0].

ABBREVIATIONS

- LPA

Lysophosphatidic Acid

- LPAR

LPA-receptor

- CREB

Cyclic-AMP Response Element Binding Protein

- ERK

Extracellular-signal Regulated Kinase

- MSK1

Mitogen and Stress-activated protein Kinase-1

- p38MAPK

p38-Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu Y, Gaudette DC, Boynton JD, Frankel A, Fang XJ, Sharma A, Hurteau J, Casey G, Goodbody A, Mellors A, et al. Clin Cancer Res. 1995;1:1223–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Westermann AM, Havik E, Postma FR, Beijnen JH, Dalesio O, Moolenaar WH, Rodenhuis S. Ann Oncol. 1998;9:437–442. doi: 10.1023/a:1008217129273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu Y, Shen Z, Wiper DW, Wu M, Morton RE, Elson P, Kennedy AW, Belinson J, Markman M, Casey G. JAMA. 1998;280:719–723. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.8.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meleh M, Pozlep B, Mlakar A, Meden-Vrtovec H, Zupancic-Kralj L. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2007;858:287–291. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bese T, Barbaros M, Baykara E, Guralp O, Cengiz S, Demirkiran F, Sanioglu C, Arvas M. J Gynecol Oncol. 2010;21:248–254. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2010.21.4.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sedlakova I, Vavrova J, Tosner J, Hanousek L. Tumour Biol. 2011;32:311–316. doi: 10.1007/s13277-010-0123-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mills GB, Eder A, Fang X, Hasegawa Y, Mao M, Lu Y, Tanyi J, Tabassam FH, Wiener J, Lapushin R, Yu S, Parrott JA, Compton T, Tribley W, Fishman D, Stack MS, Gaudette D, Jaffe R, Furui T, Aoki J, Erickson JR. Cancer Treat Res. 2002;107:259–283. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-3587-1_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogata S, Morishige K, Sawada K, Hashimoto K, Mabuchi S, Kawase C, Ooyagi C, Sakata M, Kimura T. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:1473–1480. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181c03909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cai Q, Zhao Z, Antalis C, Yan L, Del Priore G, Hamed AH, Stehman FB, Schilder JM, Xu Y. FASEB J. 2012;26:3306–3320. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-207597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gotoh M, Fujiwara Y, Yue J, Liu J, Lee S, Fells J, Uchiyama A, Murakami-Murofushi K, Kennel S, Wall J, Patil R, Gupte R, Balazs L, Miller DD, Tigyi GJ. Biochem Soc Trans. 2012;40:31–36. doi: 10.1042/BST20110608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takuwa Y, Takuwa N, Sugimoto N. J Biochem. 2002;131:767–771. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a003163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mills GB, Moolenaar WH. Nature reviews. Cancer. 2003;3:582–591. doi: 10.1038/nrc1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mutoh T, Chun J. Subcell Biochem. 2008;49:269–297. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-8831-5_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Houben AJ, Moolenaar WH. Cancer metastasis reviews. 2011;30:557–565. doi: 10.1007/s10555-011-9319-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fang X, Schummer M, Mao M, Yu S, Tabassam FH, Swaby R, Hasegawa Y, Tanyi JL, LaPushin R, Eder A, Jaffe R, Erickson J, Mills GB. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1582:257–264. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00179-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang K, Zheng D, Deng X, Bai L, Xu Y, Cong YS. J Cell Biochem. 2008;105:1194–1201. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murph MM, Liu W, Yu S, Lu Y, Hall H, Hennessy BT, Lahad J, Schaner M, Helland A, Kristensen G, Borresen-Dale AL, Mills GB. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldsmith ZG, Ha JH, Jayaraman M, Dhanasekaran DN. Genes Cancer. 2011;2:563–575. doi: 10.1177/1947601911419362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ward JD, Dhanasekaran DN. Genes & cancer. 2012;3:578–591. doi: 10.1177/1947601913475360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linnerth NM, Greenaway JB, Petrik JJ, Moorehead RA. International journal of gynecological cancer : official journal of the International Gynecological Cancer Society. 2008;18:1248–1257. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.01177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vandesompele J, De Preter K, Pattyn F, Poppe B, Van Roy N, De Paepe A, Speleman F. Genome Biol. 2002;3 doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. RESEARCH0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Theil T, McLean-Hunter S, Zornig M, Moroy T. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:5921–5929. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.25.5921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Irshad S, Pedley RB, Anderson J, Latchman DS, Budhram-Mahadeo V. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:21617–21627. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312506200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmed N, Latifi A, Riley CB, Findlay JK, Quinn MA. J Ovarian Res. 2010;3:17. doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diss JK, Faulkes DJ, Walker MM, Patel A, Foster CS, Budhram-Mahadeo V, Djamgoz MB, Latchman DS. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2006;9:83–91. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ayanbule F, Belaguli NS, Berger DH. World J Surg. 2011;35:1757–1765. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0950-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng R, Blobel GA. Genes Cancer. 2010;1:1178–1188. doi: 10.1177/1947601911404223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sakamoto KM, Frank DA. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2583–2587. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gubbay O, Rae MT, McNeilly AS, Donadeu FX, Zeleznik AJ, Hillier SG. J Endocrinol. 2006;191:275–285. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matthaios D, Zarogoulidis P, Balgouranidou I, Chatzaki E, Kakolyris S. Oncology. 2011;81:259–272. doi: 10.1159/000334449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu S, Lee J, Revelo M, Wang X, Lu S, Dong Z. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5692–5702. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zou J, Milon BC, Desouki MM, Costello LC, Franklin RB. Prostate. 2011 doi: 10.1002/pros.21368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oxford G, Smith SC, Hampton G, Theodorescu D. Oncogene. 2007;26:7143–7152. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watson CJ, Miller WR. Br J Cancer. 1995;71:840–844. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haybaeck J, Obrist P, Schindler CU, Spizzo G, Doppler W. Anticancer Res. 2007;27:3829–3835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kovacic B, Stoiber D, Moriggl R, Weisz E, Ott RG, Kreibich R, Levy DE, Beug H, Freissmuth M, Sexl V. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schultz J, Koczan D, Schmitz U, Ibrahim SM, Pilch D, Landsberg J, Kunz M. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2010;27:133–140. doi: 10.1007/s10585-010-9310-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stronach EA, Alfraidi A, Rama N, Datler C, Studd JB, Agarwal R, Guney TG, Gourley C, Hennessy BT, Mills GB, Mai A, Brown R, Dina R, Gabra H. Cancer Res. 2011;71:4412–4422. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wada C, Kasai K, Kameya T, Ohtani H. Cancer Res. 1992;52:307–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaufmann KB, Grunder A, Hadlich T, Wehrle J, Gothwal M, Bogeska R, Seeger TS, Kayser S, Pham KB, Jutzi JS, Ganzenmuller L, Steinemann D, Schlegelberger B, Wagner JM, Jung M, Will B, Steidl U, Aumann K, Werner M, Gunther T, Schule R, Rambaldi A, Pahl HL. J Exp Med. 2012;209:35–50. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Magnani L, Ballantyne EB, Zhang X, Lupien M. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002368. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aspland SE, Bendall HH, Murre C. Oncogene. 2001;20:5708–5717. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park JT, Shih Ie M, Wang TL. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8852–8860. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chiappetta G, Ferraro A, Botti G, Monaco M, Pasquinelli R, Vuttariello E, Arnaldi L, Di Bonito M, D'Aiuto G, Pierantoni GM, Fusco A. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zoumpourlis V, Papassava P, Linardopoulos S, Gillespie D, Balmain A, Pintzas A. Oncogene. 2000;19:4011–4021. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hein S, Mahner S, Kanowski C, Loning T, Janicke F, Milde-Langosch K. Oncol Rep. 2009;22:177–183. doi: 10.3892/or_00000422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang M, Page C, Reynolds RK, Lin J. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;79:67–73. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.5931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen CL, Hsieh FC, Lieblein JC, Brown J, Chan C, Wallace JA, Cheng G, Hall BM, Lin J. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:591–599. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saito RA, Micke P, Paulsson J, Augsten M, Pena C, Jonsson P, Botling J, Edlund K, Johansson L, Carlsson P, Jirstrom K, Miyazono K, Ostman A. Cancer Res. 2010;70:2644–2654. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wendling DS, Luck C, von Schweinitz D, Kappler R. Int J Mol Med. 2008;22:787–792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ramsay RG, Gonda TJ. Nature reviews. Cancer. 2008;8:523–534. doi: 10.1038/nrc2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fujimoto T, Onda M, Nagai H, Nagahata T, Ogawa K, Emi M. Breast Cancer. 2003;10:301–306. doi: 10.1007/BF02967649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fujimoto T, Yoshimatsu K, Watanabe K, Yokomizo H, Otani T, Matsumoto A, Osawa G, Onda M, Ogawa K. Anticancer Res. 2007;27:127–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sengupta S, Sharma CG, Jordan VC. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig. 2010;2:235–243. doi: 10.1515/HMBCI.2010.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Song HY, Lee MJ, Kim MY, Kim KH, Lee IH, Shin SH, Lee JS, Kim JH. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rae MT, Gubbay O, Kostogiannou A, Price D, Critchley HO, Hillier SG. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:322–327. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Dam H, Castellazzi M. Oncogene. 2001;20:2453–2464. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Safe S, Abdelrahim M. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:2438–2448. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dhanasekaran N, Dermott JM. Cell Signal. 1996;8:235–245. doi: 10.1016/0898-6568(96)00048-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu N, Bradley L, Ambdukar I, Gutkind JS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:6741–6745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Conkright MD, Montminy M. Trends in cell biology. 2005;15:457–459. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Johannessen M, Delghandi MP, Moens U. Cell Signal. 2004;16:1211–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xu N, Gutkind JS. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;201:603–609. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shaywitz AJ, Greenberg ME. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:821–861. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Michael LF, Asahara H, Shulman AI, Kraus WL, Montminy M. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1596–1603. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.5.1596-1603.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rhee HJ, Nam JS, Sun Y, Kim MJ, Choi HK, Han DH, Kim NH, Huh SO. Neuroreport. 2006;17:523–526. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000209011.16718.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lee CW, Nam JS, Park YK, Choi HK, Lee JH, Kim NH, Cho J, Song DK, Suh HW, Lee J, Kim YH, Huh SO. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;305:455–461. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00790-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McKay MM, Morrison DK. Oncogene. 2007;26:3113–3121. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kolch W. Biochem J. 2000;351(Pt 2):289–305. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pouyssegur J, Volmat V, Lenormand P. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002;64:755–763. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01135-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Prasad MV, Dermott JM, Heasley LE, Johnson GL, Dhanasekaran N. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:18655–18659. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.31.18655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Collins LR, Minden A, Karin M, Brown JH. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17349–17353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.29.17349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mitsui H, Takuwa N, Kurokawa K, Exton JH, Takuwa Y. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:4904–4910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.8.4904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gaiddon C, Tian J, Loeffler JP, Bancroft C. Endocrinology. 1996;137:1286–1291. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.4.8625901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kamiya K, Sakakibara K, Ryer EJ, Hom RP, Leof EB, Kent KC, Liu B. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:3489–3498. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00665-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liao H, Hyman MC, Baek AE, Fukase K, Pinsky DJ. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:14791–14805. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.116905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhu DY, Lau L, Liu SH, Wei JS, Lu YM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9453–9457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401063101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mayr B, Montminy M. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2001;2:599–609. doi: 10.1038/35085068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gilchrist A, Bunemann M, Li A, Hosey MM, Hamm HE. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:6610–6616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.10.6610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Radhakrishnan R, Ha JH, Dhanasekaran DN. Genes & cancer. 2010;1:1033–1043. doi: 10.1177/1947601910390516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.De Cesare D, Jacquot S, Hanauer A, Sassone-Corsi P. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:12202–12207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wiggin GR, Soloaga A, Foster JM, Murray-Tait V, Cohen P, Arthur JS. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:2871–2881. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.8.2871-2881.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Davies SP, Reddy H, Caivano M, Cohen P. Biochem J. 2000;351:95–105. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3510095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chan AM, Fleming TP, McGovern ES, Chedid M, Miki T, Aaronson SA. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:762–768. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.2.762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Goldsmith ZG, Dhanasekaran DN. Oncogene. 2007;26:3122–3142. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]