Abstract

A culturally diverse sample of formerly homeless youth (ages 6 – 12) and their families (n=223) participated in a cluster randomized controlled trial of the Early Risers conduct problems prevention program in a supportive housing setting. Parents provided 4 annual behaviorally-based ratings of executive functioning (EF) and conduct problems, including at baseline, over 2 years of intervention programming, and at a 1-year follow-up assessment. Using intent-to-treat analyses, a multilevel latent growth model revealed that the intervention group demonstrated reduced growth in conduct problems over the 4 assessment points. In order to examine mediation, a multilevel parallel process latent growth model was used to simultaneously model growth in EF and growth in conduct problems along with intervention status as a covariate. A significant mediational process emerged, with participation in the intervention promoting growth in EF, which predicted negative growth in conduct problems. The model was consistent with changes in EF fully mediating intervention-related changes in youth conduct problems over the course of the study. These findings highlight the critical role that EF plays in behavioral change and lends further support to its importance as a target in preventive interventions with populations at risk for conduct problems.

Keywords: Preventive intervention, conduct problems, executive functioning, homelessness, mediation

Targeted preventive interventions for conduct problems in children have shown promise in both reducing theory-based risk factors and promoting associated protective factors. One example is the Early Risers “Skills for Success” Program, a multiyear, multicomponent preventive intervention for children at elevated risk for the development of conduct problems. This program has produced beneficial child outcomes in a program of research including an efficacy trial (August, Realmuto, Hektner, & Bloomquist, 2001), two effectiveness trials (August, Bloomquist, Lee, Realmuto, & Hektner, 2006; August, Lee, Bloomquist, Realmuto, & Hektner, 2003); and most recently, a going-to-scale trial (Bloomquist, August, Lee, Lee, Realmuto, & Klimes-Dougan, 2013).

An important next step in conduct problems prevention research is to identify mediators that link intervention-induced changes with key outcomes. Such demonstrations can further our understanding of etiological processes and their developmental trajectories and may suggest proximal targets (i.e., mechanisms for change) for increased emphasis when delivering conduct problems prevention programs (Hinshaw, 2002). Earlier work with the Early Risers program showed that improvements in children's social skills and parent's effective discipline mediated reduction in subsequent oppositional defiant disorder symptoms (Bernat, August, Hektner, & Bloomquist, 2007). However, these mediators explained only a modicum of variance, suggesting that other unexplored mediators may be involved.

One potential mediator that may be causally linked to the development of conduct problems is child executive functioning (EF). EF can be broadly defined as the processes underlying the conscious control of one's thoughts, behaviors, and emotions in goal-directed activity (Zelazo & Mueller, 2002). EF is thought to have a role in self-regulation within externalizing disorders (Teichner & Golden, 2000). It has also been implicated in the development of early-onset and persistent antisocial behavior (Moffitt, 1993) with links shown in early childhood (Riggs, Blair, & Greenberg, 2003), and later in preadolescence (Giancola, Moss, Martin, Kirisci, & Tarter, 1996). Finally, there is evidence for environmental influences on the development of EF, including parenting (Bernier, Carlson, & Whipple, 2010), schooling (McCrea, Mueller, & Parrilla, 1999) and socioeconomic factors (Noble, McCandliss, & Farah, 2007). In view of the above, EF has heuristic importance in the search for mediators of conduct problems development and as such, may serve as a proximal target in prevention efforts.

A variety of child-focused interventions have been demonstrated to improve EF in children (see Diamond & Lee, 2011 for a review). However, few interventions have conducted mediation analyses to directly link program-induced improvements in EF to observed behavioral change (Riggs, Jahromi, Razza, Dillworth-Bart, & Mueller, 2006). In the Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies (PATHS; Kusché & Greenberg, 1994) program, a single component social-emotional skills curriculum, improvements on EF tasks were found to mediate ratings of problem behaviors in young children (Riggs, Greenberg, Kusché, & Pentz, 2006). PATHS also improved ratings of social competence and aggression in preschoolers (Bierman, Domitrovich et al., 2008), which were mediated by task orientation ratings and performance on a set-shifting task (Bierman, Nix, Greenberg, Blair & Domitrovich, 2008). The PATHS program is theorized to support EF development through intervening with relevant curriculum during a time of rapid frontal lobe structural organization in the early school-age years (Riggs, Greenberg et al., 2006).

The current study examined the role of EF as a mediator of program effects from 2 years of the Early Risers conduct problems prevention program for 6- to 12-year-old children living in family supportive housing due to homelessness (Gewirtz, 2007). This population was selected because homelessness in childhood is associated with multiple risk factors for the development of conduct problems (Rafferty & Shinn, 1991). In addition to extreme poverty, children with a history of homelessness are more likely to have poor school attendance and academic achievement, a history of witnessing violence, a history of physical and sexual abuse, as well as parental mental illness and substance abuse (Gewirtz, Hart-Shegos, & Medhanie, 2008). Like other populations at risk for conduct problems, homeless and highly mobile youth have been found to be at risk for and impacted by executive dysfunction (Masten et al., 2012).

Early Risers is well suited to address the multiple risk factors present in youth with a history of homelessness. Child, family and academic functioning are comprehensively addressed through the four primary components in the Early Risers intervention framework: Child Skills, Child School Support, Parent Skills and Family Support (August et al., 2001). EF has not been previously evaluated as an outcome or mediator of effects within Early Risers. Previous analyses with the implementation of Early Risers detailed in this manuscript showed that after 2 years of Early Risers intervention, children demonstrated reduced symptoms of depression and parents showed improved parenting self-efficacy, relative to controls (Gewirtz, DeGarmo, Lee, & August, 2013).

In the current study, measures of conduct problems and EF were collected across time to allow for longitudinal analysis, not only of the trajectory of conduct problems and EF over time, but also how one trajectory can mediate change in the other. Traditional mediation analyses typically rely on two time points to assess mediator and outcome variables. However, this approach may be misleading in understanding longitudinal changes as considerable data further detailing the change process over time is omitted. Using longitudinal growth modeling provides better estimation of individual change by simultaneously modeling both change in the mediator and change in the outcome across all available data points (Rogosa, Brandt, & Zimowski, 1982). Through this approach, the impact of program participation on the trajectory of the mediator and how that trajectory in turn is related to trajectory of the outcome may be assessed. Thus far, few studies have applied this process to assess mediation (Cheong, MacKinnon, & Khoo, 2003). Using this approach, it was hypothesized that changes in EF over the course of the study related to participation in the Early Risers programming would mediate changes observed in youth conduct problems. Specifically, it was believed that those youth who participated in the intervention would demonstrate positive growth in EF when compared to youth in the control group, which would be associated with reduced growth in conduct problems.

Methods

Intervention Sites

A cluster randomized trial to test the effectiveness of the Early Risers was conducted in a supportive housing context. Participating sites were 16 private, non-profit family supportive housing agencies, serving more than 95% of formerly homeless families resident in family supportive housing units in a large metropolitan area in the Midwest. Families were required to be residents in a participating supportive housing unit at the onset of the intervention in order to participate in the study. The 16 housing sites were randomly assigned to intervention or treatment as usual comparison conditions. Treatment as usual services varied across sites, but most commonly included case management services to support families to maintain their housing, manage finances, and access jobs, education and/or training, health insurance and routine medical services, and other needed community resources. Some sites provided childcare or offered after-school programming. Of the 16 agencies, 12 provided permanent family supportive housing and three provided temporary supportive housing (up to a 24 month stay). The remaining agency was a temporary shelter with a 6-month maximum length of stay, but was utilized in the current study as it was the only supportive housing provider in the county it serves.

Participants

In each of the 16 housing sites, all caregivers living with at least one 6 – 12 year old child were invited to participate in the study. One site assigned to the control condition had no families with children within the required age range, and therefore was dropped from the study, leaving 15 sites included in analyses. A detailed description of the participant recruitment process is provided elsewhere (Gewirtz, DeGarmo, Plowman, August, & Realmuto, 2009) and is briefly summarized here. At baseline, 154 families with 256 children provided consent/assent to enroll in the program. Immediately after recruitment and prior to baseline assessment, seventeen of these families (with 33 children) relocated or dropped out of the study and did not provide any data over the course of the study. Over the four assessment points included in current analyses, 137 families with 223 children provided data. Of this sample, mean child age was 8.12 years (SD = 2.3), and 49% of children were girls. More than two-thirds (68%) of children had a sibling also in the study, and the number of children per family varied from 1 to 5 with a mean of 1.6 children per family. All of the participating families were single-headed, and overwhelmingly female-headed (98.5%). The number of families per study site ranged from 1 to 34 with a mean of 14.87 children per study site. Average annual parent income was $10,457.22 (SD = $5,594.65). On average, parents were high school graduates or equivalent (M = 12.00 years of education, SD = 1.66). African-Americans (48%) were the largest ethnic group in the sample, followed by multiracial (21%), Caucasian (19%), and other minority group (12%) participants. During the year prior to baseline enrollment, families had moved an average 1.4 times (SD = 1.4) with 18.5% of the sample having moved three or more times in the past year. Approximately one third (34%) of youth in the sample had an open child protection case at the baseline assessment.

In order to qualify for supportive housing, families must have been homeless at the time of application (i.e., living in a shelter, on the streets, or in a car). The vast majority of families came through the shelter system to access supportive housing. While there was some variability in entrance requirements across the different supportive housing sites, most sites required families to meet the federal criteria for long-term homelessness, which is four homelessness episodes in 3 years, or one episode of homelessness lasting no less than 12 months. Additional criteria required of families by most of the supportive housing agencies included mental illness, substance use, or HIV infection, or (for one of the agencies) a mother fleeing domestic violence (see Gewirtz, 2007, and Gewirtz et al., 2009 for more information).

Intervention

Early Risers is a multicomponent, early-age-targeted, preventive system of care framework with embedded interventions designed to meet the early, multiple, and changing needs of children (and their families) at risk for serious and chronic conduct problems (August et al., 2001). Most intervention services were provided within the supportive housing agencies or within schools. The number of sessions offered to youth and their families for each intervention component was consistent across agency sites. For the few families who left their agency during the course of the study, they were invited to return to the agency for group-based services and other individualized family-based services were generally provided in their new home. The Early Risers intervention model includes two child-focused components, Child Skills and Child School Support, and two-parent/family-focused components, Parent Skills and Family Support, that are delivered as a coordinated package over a two-year period.

Child Skills

The Child Skills component is designed to teach skills that enhance children's emotional and behavioral self-regulation, peer relationships, and academic success Three skills curricula are delivered as a part of Child Skills: Child Social-Emotional Skills, Child Literature Appreciation, and Child Creative Activities. These curricula are offered within the context of coordinated summer and school-year programming. The summer camp program includes 1 hour of each of the three skills curricula per day (72 total hours recommended over the full summer of programming). During the regular school year, children continue to receive Social-Emotional Skills and Literature Appreciation curricula. These curricula are offered after the school day for two hours weekly (32 hours recommended for each component).

The Social-Emotional Skills curriculum involves the Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies (PATHS) program (Kusché & Greenberg, 1994). PATHS is designed to facilitate (a) self-control, (b) emotional awareness and understanding, (c) positive self-esteem, (d) social relationships, and (e) interpersonal problem solving skills. The Literature Appreciation curriculum features reading activities among children. Creative activities, including artistic, athletic, and outdoor experiences, allow for structured practice of developing social-emotional skills.

Child School Support

Child School Support identifies areas of school adjustment challenges and creates individualized plans to address these areas during normal school activities. The practitioner (i.e., family advocate) meets with the child's classroom teacher on a regularly-scheduled basis and assesses academic progress, social-emotional functioning, behavior, and parent involvement in school activities. Services provided include practical assistance, goal setting, emotional support, behavioral problem solving, social skills training, and referrals for specialized services. During the first year, the child is monitored a minimum of three times. Thereafter, the amount of School Support provided varies according to need.

Parent Skills

The Parent Skills component promotes parents' capacity to support their child's healthy development by building nurturing parent-child relations, improving parenting practices, and enlisting parent involvement in the child's schooling. While all other components were consistent over both years of the Early Risers program, the Parent Skills program included unique first and second year programming. During the first year, content was delivered to parents within the context of five “Family Fun Nights” that offered information on key child development topics along with parent-child activities. Topics of individual sessions include (1) effective parenting practices, (2) promoting prosocial relationships, (3) reading with your child, (4) the influence of media, and (5) family rituals.

In the second year, parents were invited to participate in the Parenting Through Change program (PTC; Forgatch & DeGarmo, 1999), a 14-week parent training program modified for this population (Gewirtz & Taylor, 2009). The PTC curriculum includes 14 sessions delivered in an individual family format. PTC targets five core parenting practices: skill encouragement, discipline, monitoring, problem solving, and positive involvement.

Family Support

Family Support is a tailored intervention that identifies basic living needs and health concerns in families, sets up goals to address these needs, and implements individualized plans to achieve positive outcomes. The advocate regularly meets with each family to assess and provide services related to child health/support, child school functioning, family basic needs, parent health/support, and parenting effectiveness. During the first year, the family is contacted three times. Subsequent Family Support provided varies according to need.

The average child attendance was 50.1% (SD = 26.9; Median = 50.6%; range = 1.2 – 99.4). Most parents (n = 68; 84%) attended at least one parent session (Family Fun nights or PTC) with average attendance of 7.96 sessions (SD = 5.80; Median = 6; range = 0 – 21). On average, children received 20.47 hours of school-based monitoring and mentoring (SD = 21.89; Median = 15.68; range = 0.03 – 103.55) and parents received 7.63 hours of family support services (SD = 6.42; Median = 5.67; range = 0.08 – 27.27).

Interventionists

Family advocates, who were hired as employees of the housing agencies and had prior experience providing case management or advocacy services to homeless families, delivered the Early Risers program. A total of five family advocates provided services across all intervention sites. Two out of the five had bachelor's degrees, and the other three had completed some relevant higher education or were working towards bachelor's degrees. Each family advocate generally provided services to two sites. Each family was assigned a single family advocate who provided all services. Family advocates provided one or two Child Skills groups at each site depending upon the number of children present at a site. Advocates received training in the overall Early Risers program, as well as specific training in PATHS and PTC, and met weekly with the Early Risers Program Manager for coaching. Fidelity to the Early Risers model, as well as to PATHS and PTC components, was assessed using observational measures (Knutson, Forgatch, Rains, & Sigmarsdóttir, 2009; Lee et al., 2008).

Assessment Procedures

Written consent was obtained from parents in accordance with procedures approved by the IRB. Study research assistants completed assessments in the family's home, either within their apartment in their supportive housing agency or within their home in another location if the family no longer lived on the agency site. Individual assessment sessions were conducted for each child and their parent(s). Each parent received a $50 gift card for completing each assessment. Measures of conduct problems and EF were assessed at multiple time points including (i) baseline, (ii) after 1 year of intervention, (iii) after 2 years of intervention, and (iv) after 1 year of post-intervention follow-up.

Measures

Child conduct problems and EF were assessed using scales from the Behavior Assessment System for Children (2nd Ed.) – Parent Rating Scale (BASC-2-PRS; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004). The BASC-2 is a widely-administered, multidimensional system used to assess broad domains of externalizing problems, internalizing problems, and adaptive skills. Items are rated on a 4-point scale, ranging from 0 = never to 3 = almost always. Gender-specific normative scores are provided in the form of T-scores with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10. The Conduct Problems scale is a clinical scale on the BASC-2 PRS. It includes 9 items (e.g., “Disobeys,” “Steals,” “Lies to get out of trouble,”). From a large normative sample, Reynolds and Kamphaus (2004) found evidence for excellent reliability of this scale (coefficient alphas = .83. ages 6–7; .88. ages 8–11; .87, ages 12–14).

The Executive Functioning scale is included in the BASC-2 PRS as a content scale. The scale includes 10 items (e.g., “Cannot wait to take turn,” “Is a self-starter,” “Acts without thinking”). Using a large normative sample, Reynolds and Kamphaus (2004) found evidence for strong reliability (coefficient alphas = .80. ages 6–7; .82. ages 8–11; .82, ages 12–14). As described in Reynolds and Kamphaus (2004), an earlier version of the EF scale derived from the BASC (Barringer & Reynolds, 1995) was shown to correlate well with other commonly used questionnaire measures of EF, and was also sensitive to EF deficits in children with externalizing disorders (Sullivan & Riccio, 2006).

Two different age levels of the BASC-2 rating scale were utilized in the present study: the child version for youth up through age 11 at baseline, and the adolescent version for age 12 at baseline. Participants' parents received the same version of the questionnaire throughout the study for longitudinal consistency of items. Because of the age range of the sample, only a small number of participants (n = 25) required the adolescent version of the BASC-2-PRS (i.e., those youth who were age 12 at the baseline assessment point) throughout the study. The child version of the BASC-2-PRS has fully independent Executive Functioning and Conduct Problems scales. However, the adolescent version has a single item of overlap between the two scales (“Cannot wait to take turn.”). For those youth who received the adolescent version of the BASC, this item was dropped from the Executive Functioning scale. In order to compute corrected norm-referenced T scores for these participants, a score was imputed for the dropped item by using the average item score from the other items in the scale and adding that to the total raw score.

Because youth were administered the same version of the BASC questionnaire throughout the study, this approach required an extension of the childhood norms into early adolescence for multiple participants as they reached age 12 and older. Twelve participants “aged out” of the child version at the one-year assessment point, 20 additional participants at the two-year assessment, and 19 additional participants at the final three-year assessment, leaving 51 total participants affected by the use of the childhood norms after age 11 at some point during the study. In order to investigate the impact of the use of age norm extensions for these participants on analyses, all analyses were also run with a subsample excluding this group (n=172). All results remained consistent with analyses using the full sample. Given this equivalence, it was decided to retain these participants in analyses.

Results

Analytic Strategy

Intent-to-treat analyses were used to examine intervention effects. Latent growth models (LGM) were estimated using the structural equation modeling program Mplus version 6 (Muthén & Muthén, 2010). Analyses were based in part on the parallel process LGM approach to examining mediational effects of intervention outcomes as described by Cheong et al. (2003). In this approach, two parallel processes (i.e., growth in conduct problems and EF) were modeled over 4 time points of the Early Risers program. Mediation is demonstrated in a parallel process LGM by the intervention effect influencing the growth of the outcome (i.e., conduct problems) indirectly through its effect on growth in the mediator (i.e., EF).

A step-wise approach was used to establish the presence of mediation utilizing the framework proposed by Baron and Kenny (1986). Mediation is successfully demonstrated if: 1) the intervention demonstrates a direct effect on the rate of growth of conduct problems; 2) the intervention demonstrates a direct effect on the rate of growth of EF; 3) When examined simultaneously, a) the intervention continues to demonstrate a direct effect on growth in EF, b) growth in EF demonstrates a direct effect on growth in conduct problems, and c) the intervention no longer demonstrates a reliable direct effect on growth in conduct problems. As an additional step in establishing mediation, a significant indirect effect of the intervention on growth in conduct problems through growth in EF will be noted. Intervention effect sizes were calculated using the mean differences in growth rates for the intervention and control groups divided by the standard deviation of the growth rates, which is equivalent to Cohen's d (Feingold, 2009).

The multilevel nature of the dataset was accounted for in all primary analyses. Three levels were present in the dataset, including 1) individual participants (n=223), 2) participants nested within families (n=137), and 3) families nested within intervention sites (n=15). The data collected from children within the same family or families sharing an intervention site are not fully independent and could therefore violate standard assumptions of independence. Therefore, these groupings were taken into account when estimating each structural equation model.

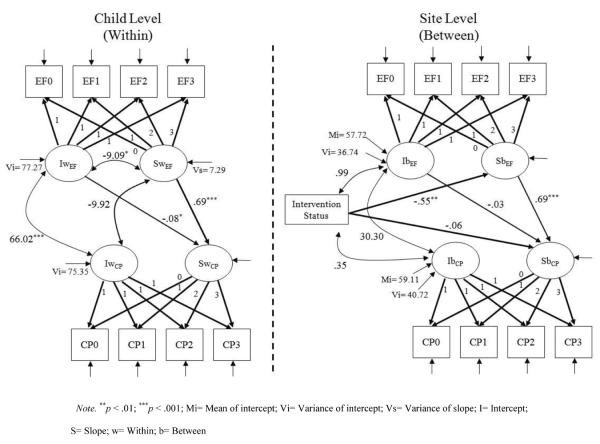

Given the complex nature of the planned analyses, two approaches were utilized to account for the multilevel nature of the dataset. First, in accounting for the nesting of individual participants within families, the “TYPE IS COMPLEX” feature was utilized to compute adjusted standard errors of parameters and chi-square tests of model fit taking into account the multilevel nature of complex data. This approach is recommended when examining very complex multilevel mediational models (MacKinnon, 2008). However, the COMPLEX feature is only able to account for single clustering variable and cannot incorporate an additional level of analysis (Muthén & Muthén, 2010). Therefore, the additional level of the dataset (nesting within intervention sites) was accounted for using a more traditional two-level modeling approach (e.g., Duncan et al., 1997) in conjunction with the COMPLEX feature (COMPLEX TWOLEVEL). This required the estimation of all growth models at both the individual child level (i.e., Within) and at the site level (i.e., Between). Note that Mplus does not treat repeated measures on individual subjects as a level of analysis in clustered data (Muthén & Muthén, 2010). Because of the cluster randomized design, all intervention effects were examined at the site level of analysis. Within the parallel process model, the relationship between growth in EF and conduct problems was evaluated at the individual child level. See Figures 1 and 2 for more information. A method described by Preacher, Zyphur, & Zhang (2010) was used to evaluate the indirect effect of the intervention on growth in conduct problems through growth in EF in the context of a two-level mediational model. In this approach, the indirect effect is estimated at the Between level through constraining the Between path between the mediator and the outcome to be equivalent to the same path at the Within level. See Preacher, Zyphur, & Zhang (2010) for additional details.

Figure 1.

A two-level latent growth model of conduct problems (CP) with intervention status as a between-level covariate.

Figure 2.

A two-level parallel process latent growth model demonstrating the mediation of intervention effects on growth in conduct problems (CP) by changes in executive functioning (EF).

Missing values were present in the dataset due to the longitudinal nature of the design, but adequate covariance coverage was present (ranging from .55 to .96). A missing value analysis was conducted using the PASW (SPSS) software version 18.0.2. The Little's MCAR test conducted on all measures included in the models was consistent with values missing completely at random, χ2(32) = 29.39, p =.60. Missing data in all models were managed with the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) procedure used by Mplus version 6. This method has been shown to be very efficient when analyzing data from samples with moderate levels of missing values. When using FIML, the estimation of each parameter is made on the basis of all available information from each participant. Consequently, we can retain in the analysis participants with missing data so they contribute to model estimation.

The fit of each estimated model to the data was evaluated. A good model fit should yield a nonsignificant χ2 value, but this test often does not provide a complete picture of model fit and other fit indices may be preferred (Kline, 2005). Other fit indices were evaluated according to Hu & Bentler (1999), with a CFI greater than .95 and an RMSEA below .05 indicating good fit, and a CFI greater than .90 and an RMSEA below .08 indicating adequate fit.

After testing the model fit on the overall sample, we examined the role that demographic factors may play in predicting key model parameters. Models were run including gender, age (a continuous variable), and ethnicity (a dichotomous African-American versus European American variable) as covariates in predicting each latent intercept and slope. We also examined the generalizability of the model across age, genders and across ethnic groups by using multiple group analyses. However, because there was variability on each of these demographic variables within families, multiple group analyses were not possible within Mplus when using the COMPLEX TWOLEVEL analysis type. Therefore, group differences were examined using a subsample of one child randomly selected from each family (n=137). This allowed the data to be organized into a single hierarchical feature (i.e., children nested within sites) in which the COMPLEX analysis type could be utilized. In order to examine potential differences by age, the sample was divided into two groups representing those youth who at recruitment were ages 8 and up (n = 73) and those youth who were ages 7 and younger (n = 62). Because a majority of the sample was African-American (n=82; 51%), African-American participants were compared to European Americans, the next largest ethnic group in the sample (n= 27; 17%). The other ethnic groups represented in the sample did not have an adequate number of participants for individual comparisons in multiple group analyses. The chi-square difference test (Δχ2) and change in comparative fit index (Δ CFI) were used to assess the significance of the differences between the multiple group “constrained” models, in which the two groups are assumed to have equivalent parameters, and the multiple group “unconstrained” models, in which the groups are not assumed to have identical model parameters. The Δχ2 test indicates a significant difference between models for χ2 distribution p values of less than .05, consistent with an unconstrained parameter resulting in a superior model fit. According to Cheung and Rensvold (2002), Δ CFI of .01 or greater indicates a significant difference between the two models. Key parameters were examined for group differences within this framework, including mediation paths as well as means and variances of latent slope and intercept factors.

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 includes correlations and descriptive statistics of key study variables. Correlations of study variables with demographic factors are also provided. Sample characteristics were also examined at baseline for those participants whose parents provided baseline data (n=215). At baseline, approximately 55% (n=119) of the sample fell into borderline or clinical range (T-score ≥ 60) on either the Conduct Problems or Executive Functioning scales.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

| Measure | EF Baseline (n=215) | EF Year 1 (n=161) | EF Year 2 (n=139) | EF Year 3 (n=127) | CP Baseline (n=215) | CP Year 1 (n=161) | CP Year 2 (n=139) | CP Year 3 (n=127) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EF Baseline | – | |||||||

| EF Year 1 | .76 | – | ||||||

| EF Year 2 | .72 | .79 | – | |||||

| EF Year 3 | .63 | .71 | .81 | – | ||||

| CP Baseline | .69 | .58 | .57 | .47 | – | |||

| CP Year 1 | .51 | .63 | .51 | .46 | .73 | – | ||

| CP Year 2 | .52 | .52 | .63 | .53 | .63 | .73 | – | |

| CP Year 3 | .40 | .40 | .49 | .59 | .59 | .63 | .78 | – |

| Age at Recruitment | .03ns | −.03ns | −.06ns | −.07ns | −.05ns | −.09ns | −.02ns | .01ns |

| Male Gender | .04ns | .05ns | −.01ns | .02ns | .05ns | .12ns | .02ns | .12ns |

| African American Ethnicity | −.17* | −.20* | −.24* | −.27** | −.10ns | −.13ns | −.12ns | −.04ns |

|

| ||||||||

| MEAN | 57.69 | 56.50 | 55.20 | 54.46 | 59.23 | 57.75 | 57.24 | 55.97 |

| SD | 11.49 | 11.65 | 11.67 | 11.29 | 12.29 | 10.63 | 9.92 | 10.39 |

Note. EF = Executive Functioning; CP = Conduct Problems; All correlations are significant p < .001, unless noted.

= p>.05;

= p<.01;

= p<.05

Attrition over the course of the intervention was examined for the two conditions. Attrition was due to loss of families at follow up or a family's decision to drop out of the study. Over the four assessment points, 223 total participants provided data, including 215 at baseline, 161 at 1 year, 139 at 2 years, and 127 at 3 years. A few participants (often siblings) entered the study after the baseline assessment. An analysis comparing participants who attritted at any point during the study (n=96) with those participants who provided data in the third year of data collection (i.e., the final assessment point used in the current study; n=127) was conducted. No significant group differences were found on any variables included in the present analyses, including intervention condition or in demographic variables (i.e., gender, ethnicity, and family income).

Primary Analyses

Prior to examining intervention effects, two-level LGM were estimated separately for conduct problems and EF in order to examine model fit to the data. These models included parent-reported data for the full sample (n=223) collected over the four assessment points as indicators of latent intercept and slope factors. The LGM were simultaneously estimated at both the child and site levels of analysis. The conduct problems LGM was an acceptable fit for the data, χ2(8) = 12.10, p = .15, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .05. The latent intercept and slope factors were not significantly correlated at either the individual or site levels, indicating that initial levels of conduct problems were not predictive of the subsequent rate of change. The slope demonstrated a significant negative value (M = −.90; p <.001), indicating an overall downward trend in conduct problems over the course of the study. The EF LGM was also an acceptable fit for the data, χ2(8) = 15.06, p = .06, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .06. The latent intercept and slope factors were again not significantly correlated at either the individual or site levels, indicating that initial levels of EF were not predictive of the subsequent rate of change. The slope of EF also demonstrated a significant negative value (M = −.94; p =.001), reflective of general improvement in ratings of EF (i.e., higher values reflect more impaired EF) over the course of the study.

Next, the impact of intervention status was examined on the rate of change of conduct problems and EF over the course of the study. The two LGM described above were each estimated with the inclusion of intervention status as a covariate at the site level of analysis. Figure 1 illustrates the two-level conduct problems LGM including intervention status as a covariate. Note that all parameter estimates are unstandardized. This model was a strong fit for the data, χ2(12) = 10.55, p = .48, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00. Intervention status demonstrated a significant direct effect on the latent slope factor (b= −.52, p=.007), indicating that children within intervention sites demonstrated a stronger negative rate of change in conduct problems over the course of the study. This intervention effect was consistent with a small effect size (d=.35). The latent intercept factor was uncorrelated with intervention status, reflecting no baseline differences in conduct problems between the intervention and control groups. An EF LGM was also estimated including intervention status as a covariate. This model demonstrated an acceptable fit for the data, χ2(11) = 18.67, p = .07, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .06. Intervention status demonstrated a significant direct effect on the latent slope factor (b= −.60, p<.001), indicating that children at the intervention sites demonstrated a stronger negative rate of change on the EF scale (i.e., reflecting improvements in EF) over the course of the study. This intervention effect was consistent with a medium effect size (d=.56). The intercept reflected no baseline differences in EF by intervention condition.

A mediational model was next examined utilizing a two-level parallel process LGM (Cheong et al., 2003). Figure 2 illustrates this model, which simultaneously modeled the EF and conduct problems LGM at both the individual and site levels of analysis along with the intervention status covariate at the site level. Mediation was assessed by evaluating the impact of intervention status on the slopes of the EF LGM and the conduct problems LGM at the site level along with the impact of the EF slope on the conduct problems slope at the individual level. Additional paths from the intercept of the EF LGM to the slope of the conduct problems LGM were included at both levels of the model order to control for baseline levels of EF potentially influencing subsequent rate of growth of conduct problems. Aside from a significant chi-square value indicating poor statistical fit, other model fit indices indicated an adequate fit for the data, χ2(48) = 104.42, p < .001, CFI = .96, RMSEA = .07.

Evidence for mediation was assessed in the model. At the site level, intervention status had a significant direct effect on the slope of EF, (b= −.55, p=.002), with the intervention group demonstrating a reduced rate of growth of problematic EF. In the context of the mediational model, this intervention effect was consistent with a medium effect size (d=.79). Also at the site level, intervention status no longer had a reliable impact on conduct problems slope. At the individual level, EF slope was strongly associated with conduct problems slope (b= .69, p<.001), indicating that changes in EF were highly predictive of associated changes in conduct problems. The indirect effect of the intervention on conduct problems slope through EF slope was also significant (b= −.38, p=.018). Thus, the model was consistent with a mediational process, with the rate of change of EF fully mediating the intervention impact on the rate of change of conduct problems.

Several additional findings emerged within the mediational model. At the site level, intervention status was not associated with either intercept. At the individual level, the EF intercept predicted the conduct problems slope (b= −.07, p= .026), indicating that those youth with poorer initial levels of EF tended to show larger improvements in conduct problems over the course of the study. Also at the individual level, the EF slope was reliably associated with the EF intercept (cov. = −9.09, p=.028), indicating that those youth with poorer initial EF demonstrated greater improvements over time. At the individual level, initial levels of EF and conduct problems were also reliably associated, with the intercepts of the two LGM demonstrating a significant covariance (cov. = 66.02, p<.001).

In order to examine the role of demographic factors in predicting key model parameters, models were run including gender, age (a continuous variable), and ethnicity (a dichotomous African-American versus European American variable) as covariates in predicting each latent intercept and slope. Age and gender did not predict any of the latent variables included in the models. Ethnicity was significant predictor of the intercepts of EF (b= −8.63, p<.001) and conduct problems (b= −7.17, p=.003), with African American ethnicity predicting lower intercepts (consistent with fewer endorsed problems with EF and conduct problems at baseline). All key effects were consistent with the inclusion of demographic variables. However, the inclusion of demographic variables into the model (both independently and as a group) resulted in poor model fit. Therefore, these demographic variables were not retained in the final models.

Multiple group models were estimated for all models to examine any differences in model parameters by age, gender or ethnicity. Due to these demographic variables demonstrating variability within families, multiple group two-level models were not able to be estimated using the full sample. Therefore, a subsample of a single child per family (n=137) was used to run multiple group models. When compared to European-American participants, African American participants demonstrated a lower mean intercept of EF problems (Δχ2(5) = 22.25, p<.001; ΔCFI = .034), meaning that parents of African American participants tended to initially rate fewer concerns about EF. No significant differences emerged when comparing older versus younger participants and male versus female participants.

Discussion

This study examined changes in youth EF and conduct problems as a result of participating in the Early Risers program, delivered in supportive housing settings for formerly homeless families. Using an intent-to-treat approach, children who participated in the intervention along with their families demonstrated reduced growth in parent-rated conduct problems over the course of the study, including 2 years of intervention and an additional follow-up assessment one year after completing the intervention. Participation in the intervention was also associated with improved parent-reported child EF over the course of the study. A primary goal of the current study was to examine whether EF mediated program effects for the Early Risers program. Using an innovative methodological approach to examine simultaneous change associated with mediation, a parallel process latent growth model revealed that changes in EF fully mediated changes in youth conduct problems over four annually-spaced time points. This finding was consistent across age, gender, and ethnicity. This finding highlights the critical role that EF plays in behavioral change and lends further support to its importance as a proximal target in preventive interventions with high-risk populations. The current findings extend previous literature of multicomponent, early-age, targeted conduct problems prevention programs by demonstrating that EF can play a mediational role in outcomes in these programs.

It is noteworthy that the Early Risers program resulted in reduced growth of conduct problems for elementary-age children in population with a history of homelessness. This finding is consistent with prior findings for elementary-age children observed with the Early Risers program (August et al., 2001; Bernat et al., 2007) and other conduct prevention programs for this age (Boisjoli, Vitaro, Lacourse, Barker, & Tremblay 2007; Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2011; Lochman & Wells, 2004). The results of the current study extend previous findings primarily derived from indicated risk samples by showing that a high selective risk sample of children in supportive housing context also benefits from preventive services. Notably, the current results also extend a recent analysis of outcomes of this intervention by incorporating an additional year of follow-up data and documenting a direct effect on trajectories of child conduct problems (Gewirtz et al., 2013).

The direct impact of the intervention on improving EF over time is a new finding for the Early Risers program. This is an important result given that EF has been implicated in the development of early-onset and persistent antisocial behavior (Giancola et al., 1996; Moffitt, 1993; Riggs et al., 2003). An intervention that slows the growth of problematic EF might provide protective effects for these children. This is in keeping with resilience research showing that behavioral and emotional regulation capacity (related to EF) can buffer the impact of myriad risk factors (Masten & Coatsworth, 1998). In addition, the current findings mesh with research showing that EF can be positively modified through targeted short-term training (Diamond & Lee, 2011) and through universal or single component prevention programs (Bierman, Nix et al., 2008; Diamond, Barnett, Thomas, & Munro, 2007; Riggs, Greenberg et al., 2006) with preschool and elementary ages.

Because Early Risers is a comprehensive intervention with four components (i.e., Child Skills, Child School Support, Parent Skills, and Family Support), it is difficult to ascertain if any one component or combinations of components account for the effects on EF in this study. It stands to reason that children learned EF-related self-regulation skills via the Child Skills component that used the PATHS curriculum (Kusché & Greenberg, 1994). PATHS has shown positive effects on EF as well as mediation effects of EF on other social and behavioral outcomes (Bierman, Domitrovich et al., 2008; Riggs, Greenberg et al., 2006). We further speculate that the Parent Skills component likely contributed to children's development of EF-related self-regulation via external management, an early precursor of internal self-control related to EF development (see Vygotsky, 1978). This is also consistent with previous naturalistic research showing that EF is malleable by parenting (Bernier et al., 2010). It may well be that in Early Risers, EF is influenced by child- and parent-focused interventions in combination.

The mediational result from this study informs theory more broadly pertaining to the development and prevention of antisocial behavior (Masten & Cicchetti, 2010). The concept of developmental cascades, in which interacting systems have a cumulative effect on developmental pathways, is particularly relevant to the current findings (Masten & Cicchetti, 2010). Poor EF development is associated with impaired social and emotional competence, including conduct problems (See Riggs, Jahromi et al., 2006 for a review). An intervention that promotes individual development in EF is likely to have positive effects on multiple “downstream” outcomes, including interpersonal, academic, and behavioral functioning. While the present findings only examined one such outcome (i.e., conduct problems), a cascade theory promotes the conceptualization that competence or deficits in areas such as EF have a progressive and cumulative impact on many developmental outcomes. This is consistent with the early starter pathway of antisocial behavior, in which early deficits in areas such as EF in combination with psychosocial risk may lead youth towards life-course-persistent antisocial behavior (Moffitt, 1993). Future work in this area may better understand the larger developmental implications of improved EF through a cascade modeling approach incorporating outcomes such as social, academic, and family functioning.

Despite the unique nature of the current sample, it is believed that the current findings are generally relevant to youth coming from other populations at high risk for conduct problems. Lee et al. (2010) reported on the psychosocial characteristics of a sample of children and their mothers who were living in urban supportive housing. This selective risk sample was compared to a demographically similar sample of children from a school-based prevention study where children were recruited based on teacher ratings of children's aggressive/disruptive behavior. The children living in supportive housing context had comparable levels of externalizing, internalizing, and school problems as the indicated risk, school-based sample.

This study highlights an innovative methodology for studying mediational effects involved in developmental processes. Parallel process latent growth modeling allowed for the developmental trajectories of EF and conduct problems to be modeled simultaneously. Mediation analyses conducted with prevention studies most often rely on two time points to assess mediator and outcome variables rather than understanding how those variables change over time. The present approach not only allows for the incorporation of considerably more data in understanding such processes, it is also more consistent with a developmental model of intervention and associated behavioral change. With this approach, it is important to note that temporal causality may not be assumed between the trajectories of the mediator and the outcome variables because of their simultaneous measurement. While existing theory is strongly suggestive of an etiological role of EF in the development of conduct problems, the current analyses do not allow us to make such an interpretation.

The present study is not without limitations. First, only parent-reported data are utilized. Because of the young age and highly mobile nature of the study population, parent report allowed for a consistent source of information over multiple time points. However, relying exclusively on parent report may have inflated some of the associations between these constructs and introduced some potential reporter biases due to the possibility of shared measurement error. Relatedly, EF was examined only through parent-reported questionnaire data and not through performance-based tasks. While the incorporation of such tasks would have strengthened the assessment of EF, the use of behaviorally-based questionnaires has been advocated as a more ecological-relevant and practical approach to assessing EF in youth (Garcia-Barrera, Kamphaus, & Bandalos, 2011). Also notable is recent research by Toplak and colleagues (2013) who describe performance-based tasks and behavioral ratings as each assessing unique aspects of EF with little overlapping variance. Rating scales best captured individual goal pursuit whereas performance-based tasks reflected processing efficiency. Performance-based tasks may be incorporated in future studies to determine if the current findings are supported with these tasks.

Further limitations included the extension of childhood age norms for multiple participants in computing standardized scores from questionnaire data. While results remained consistent when excluding those youth for whom this was necessary, it would be preferable to avoid such extensions of age norms. Furthermore, the sample size utilized for the described analyses is smaller than ideal and parameter estimates would be more accurate with a larger sample. Relatedly, the use of a cluster-randomized trial design represented a limitation with respect to analysis and power. The number of sites used in the study design was suboptimal for the analyses conducted, such that resulting biases in model parameters cannot be ruled out. Logistical considerations of conducting the intervention necessitated this design for the current study, but future work may benefit from a study design associated with greater power to detect intervention effects.

Taken together, the current results are strongly supportive of continued efforts to understand the mechanisms of behavioral change resulting from preventive interventions. Through the identification of such mechanisms, preventive interventions may be increasingly targeted towards proximal agents of change. Furthermore, efforts towards this goal will not only guide prevention efforts, but can also greatly inform our understanding of more basic etiologic processes in developmental psychopathology. It is through such synergism between these two fields that we may most effectively understand and promote positive development in youth.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants to Gerald J. August from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH074610 and P20 MH085987). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute Of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to thank Nicole Morrell, the project manager, for her major contribution to this effort, as well as David DeGarmo for his generous statistical consultation.

References

- August GJ, Bloomquist ML, Lee SS, Realmuto GM, Hektner JM. Can evidence-based prevention programs be sustained in community systems-of-care? The Early Risers advanced-stage effectiveness trial. Prevention Science. 2006;7:151–165. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-0024-z. doi:10.1007/s11121-005-0024-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- August GJ, Lee SS, Bloomquist ML, Realmuto GM, Hektner JM. Dissemination of an evidence-based prevention innovation for aggressive children living in culturally diverse, urban neighborhoods: The Early Risers effectiveness study. Prevention Science. 2003;4:271–286. doi: 10.1023/a:1026072316380. doi:10.1023/A:1026072316380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- August GJ, Realmuto GM, Hektner JM, Bloomquist ML. An integrative components intervention for aggressive elementary school children: The Early Risers Program. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:614–626. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.69.4.614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barringer MS, Reynolds CR. Behavior ratings of frontal lobe dysfunction. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the National Academy of Neuropsychology; Orlando, FL. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bernat D, August GJ, Hektner JM, Bloomquist ML. The Early Risers preventive intervention: Six year outcomes and mediational processes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35:605–617. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9116-5. doi:10.1007/s10802-007-9116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier A, Carlson SM, Whipple N. From external regulation to self- regulation: Early parenting precursors of young children's executive functioning. Child Development. 2010;81:326–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01397.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierman KL, Domitrovich CE, Nix RL, Gest SD, Welsh JA, Greenberg MT, Gill S. Promoting academic and social-emotional school readiness: The Head Start REDI program. Child Development. 2008;79:1802–1817. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01227.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01227.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierman KL, Nix RL, Greenberg MT, Blair C, Domitrovich CE. Executive functions and school readiness intervention: Impact, moderation, and mediation in the Head Start REDI program. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:821–843. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000394. doi:10.1017/S0954579408000394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomquist ML, August GJ, Lee SS, Lee C-YS, Realmuto GM, Klimes-Dougan B. Going-to-scale with the Early Risers conduct problems prevention program: Use of a comprehensive implementation support (CIS) system to optimize fidelity, participation and child outcomes. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2013;38:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2012.11.001. doi:10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisjoli R, Vitaro F, Lacourse E, Barker ED, Tremblay RE. Impact and clinical significance of a preventive intervention for disruptive boys: 15-year follow-up. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;191:415–419. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.030007. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.106.030007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong J, MacKinnon DP, Khoo ST. Investigation of mediational processes using parallel process latent growth curve modeling. Structural Equation Modeling. 2003;10:238–262. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM1002_5. doi:10.1207/S15328007SEM1002_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, Rensvold RB. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:233–255. [Google Scholar]

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group The effects of the Fast Track Preventive Intervention on the development of conduct disorder across childhood. Child Development. 2011;82:331–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01558.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01558.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A, Barnett S, Thomas J, Munro S. Executive function can be improved in preschoolers by regular classroom teachers. Science. 2007;318:1387–1388. doi:10.1126/science.1151148. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A, Lee K. Interventions shown to aid executive function development in children 4 to 12 years old. Science. 2011;333:959–964. doi: 10.1126/science.1204529. doi:10.1126/science.120452910.1126/science.1204529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Albert A, Hops H, Stoolmiller M, Muthen B. Latent variable modeling of longitudinal and multilevel substance use data. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1997;32:275–318. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3203_3. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr3203_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feingold A. Effect sizes for growth-modeling analysis for controlled clinical trials in the same metric as for classical analysis. Psychological Methods. 2009;14:43–53. doi: 10.1037/a0014699. doi:10.1037/a0014699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, DeGarmo DS. Parenting through change: An effective prevention program for single mothers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:711–724. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.5.711. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.67.5.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Barrera MA, Kamphaus RW, Bandalos D. Theoretical and statistical derivation of a screener for the behavioral assessment of executive functions in children. Psychological Assessment. 2011;23:64–79. doi: 10.1037/a0021097. doi:10.1037/a0021097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz A. Promoting children's mental health in family supportive housing: A community-university partnership for formerly homeless children and families. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2007;28:359–374. doi: 10.1007/s10935-007-0102-z. doi:10.1007/s10935-007-0102-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz AH, DeGarmo DS, Lee SS, August GA. Twenty-four month outcomes of the Early Risers prevention trial with formerly homeless families residing in supportive housing. 2013. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz A, DeGarmo D, Plowman E, August G, Realmuto G. Parenting, parental mental health, and child functioning in families residing in supportive housing. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79:336–347. doi: 10.1037/a0016732. doi: 10.1037/a0016732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz AH, Hart-Shegos E, Medhanie A. Psychosocial status of children and youth in supportive housing. American Behavioral Scientist. 2008;51:810–823. [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz A, Taylor T. Participation of homeless and abused women in a parent training program. In: Hindsworth Mildred F., Lang Trevor B., editors. Community Participation and Empowerment. Nova; Hauppage, NY: 2009. pp. 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR, Moss HB, Martin CS, Kirisci L, Tarter RE. Executive cognitive functioning predicts reactive aggression in boys at high risk for substance abuse: A prospective study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1996;20:740–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01680.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP. Intervention research, theoretical mechanisms, and causal processes related to externalizing behavior patterns. Developmental and Psychopathology. 2002;14:789–818. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402004078. doi:10.1017.S0954579402004078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L.-t., Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Knutson NM, Forgatch MS, Rains LA, Sigmarsdóttir M. Fidelity of Implementation Rating System (FIMP): The manual for PMTO™. Revised ed. Oregon Social Learning Center; Eugene, OR: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kusché CA, Greenberg MT. The PATHS curriculum. Developmental Research and Programs, Inc; Seattle: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, August G, Realmuto G, Horowitz J, Bloomquist M, Klimes-Dougan B. Fidelity at a distance: Assessing implementation fidelity of the Early Risers Prevention Program in a going-to-scale intervention trial. Prevention Science. 2008;9:215–229. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0097-6. doi:10.1007/s11121-008-0097-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SS, August GJ, Gewirtz AH, Klimes-Dougan B, Bloomquist ML, Realmuto GM. Identifying unmet mental health needs in children of formerly homeless mothers living in a supportive housing community sector of care. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;38:421–432. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9378-1. doi:10.1007/s10802-009-9378-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Wells KC. The Coping Power Program for preadolescent aggressive boys and their parents: Outcome effects at the 1-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:571–578. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.571. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Cicchetti D. Developmental cascades. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:491–495. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000222. doi:10.1017/S0954579410000222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Coatsworth JD. The development of competence in favorable and unfavorable environments: Lessons from research on successful children. American Psychologist. 1998;53:205–220. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.205. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.53.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Herbers JE, Desjardins CD, Cutuli JJ, McCormick CM, Sapienza JK, Zelazo PD. Executive function skills and school success in young children experiencing homelessness. Educational Researcher. 2012;41:375–384. [Google Scholar]

- McCrea SM, Mueller JH, Parilla RK. Quantitative analyses of schooling effects on executive function in young children. Child Neuropsychology. 1999;5:242–250. doi: 10.1076/0929-7049(199912)05:04;1-R;FT242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. The neuropsychology of conduct disorder. Development and Psychopathology. 1993;5:135–151. doi:10.1017.S0954579402004078. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user's guide. Sixth Edition Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Noble KG, McCandliss BD, Farah MJ. Socioeconomic gradients predict individual differences in neurocognitive abilities. Developmental Science. 2007;10:464–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00600.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Zyphur MJ, Zhang Z. A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychological Methods. 2010;15:209–233. doi: 10.1037/a0020141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafferty Y, Shinn M. The impact of homelessness on children. American Psychologist. 1991;46:1170–1179. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.46.11.1170. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.46.11.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Kamphaus RW. Behavior Assessment System for Children. 2nd ed American Guidance Service; Circle Pines, MN: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Riggs NR, Blair CB, Greenberg MT. Concurrent and 2-year longitudinal relations between executive function and the behavior of 1st and 2nd grade children. Child Neuropsychology. 2003;9:267–276. doi: 10.1076/chin.9.4.267.23513. doi:10.1076/chin.9.4.267.23513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs NR, Greenberg MT, Kusché CA, Pentz MA. The meditational role of neurocognition in the behavioral outcomes of a social-emotional prevention program in elementary school students: Effects of the PATHS Curriculum. Prevention Science. 2006;7:91–102. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-0022-1. doi:10.1007/s11121-005-0022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs NR, Jahromi LB, Razza RP, Dillworth-Bart JE, Mueller U. Executive function and the promotion of social-emotional competence. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2006;27:300–309. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2006.04.002. [Google Scholar]

- Rogosa D, Brandt D, Zimowski M. A growth curve approach to the measurement of change. Psychological Bulletin. 1982;92:726–748. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.92.3.726. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan JR, Riccio CA. An empirical analysis of the BASC Frontal Lobe/Executive Control scale with a clinical sample. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2006;21:49–501. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teichner G, Golden CJ. The relationship of neuropsychological impairment to conduct disorder in adolescence: A conceptual review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2000;5:509–528. doi:10.1016/S1359-1789(98)00035-4. [Google Scholar]

- Toplak ME, West RF, Stanovich KE. Practitioner review: Do performance-based measures and ratings of executive function assess the same construct? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013;54:131–143. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12001. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky LS. Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Zelazo PD, Muller U. Executive function in typical and atypical development. In: Goswami U, editor. Handbook of childhood cognitive development. Blackwell; Oxford, UK: 2002. pp. 445–469. [Google Scholar]