Abstract

Objective

To identify those patients with gynecologic cancers and intestinal perforation in whom conservative management may be appropriate.

Methods

A retrospective review was performed of all gynecologic oncology patients with intestinal perforation at our institution between 1995 and 2011. The Kaplan-Meier method and Cox proportional hazards models were used to analyze factors influencing survival.

Results

Forty-three patients met the study criteria. The mean age was 59 years (range: 38-82 years). A large number of patients had peritoneal carcinomatosis and history of bowel obstruction. Surgery was performed in 28 patients, and 15 were managed conservatively. Overall mortality at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months was 26%, 40%, 47%, and 59%, respectively. Only cancer burden at the time of perforation was independently predictive of mortality. Patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis, distant metastasis, or both were at 42 times higher risk of death than those with no evidence of disease (95% CI: 3.28-639.83), and at 7 times higher risk of death than those with microscopic/localized disease (95% CI: 1.77-29.94). When adjusted for the extent of disease spread, management approach (conservative vs. surgical) was not a significant predictor of survival (p≥0.05). The length of hospital stay (19 days vs. 7 days) and the complication rate (75% vs. 26.7%) were significantly higher in the surgical group than in the non-surgical group (p<0.05).

Conclusions

Patients who develop intestinal perforation in the setting of widely metastatic disease have a particularly poor prognosis. Aggressive surgical management is unlikely to benefit such patients and further impairs their quality of life.

Keywords: Intestinal perforation, Management, Survival

Introduction

Patients with gynecologic malignancies are especially prone to bowel injury, which can occur in various forms. One, intestinal perforation, is generally considered an emergent condition associated with high mortality [1, 2]. Any part of the gastrointestinal tract may become perforated and cause spillage of the intestinal contents into the peritoneal cavity, leading to the development of peritonitis, intra-abdominal abscess, or both. In some instances, the perforation may be small and effectively walled off by surrounding abdominal structures, thus localizing the inflammation and infection. Although the exact cause cannot be determined for every single patient, several mechanisms explain the prevalence of bowel injuries in gynecologic cancer. First, tumor invasion of the bowel is common in advanced stage ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancers. Second, radiation is frequently administered in patients with cervical cancer and can potentially cause radiation-related bowel complications. Third, intestinal perforation is a well-known complication of bevacizumab (Avastin by Genentech, San Francisco, CA, USA), a humanized monoclonal antibody against vascular endothelial growth factor that is increasingly being used in patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer.

Immediate surgery is often necessary in the event of bowel injury except when the leak is walled off; in these cases conservative treatment with careful observation may be justified. However, patients with gynecologic cancers are often of advanced age and frequently have concurrent co-morbidities. In addition, the life expectancy of some may already be limited due to an extensive cancer burden that has been treated with multiple chemotherapy regimens. A few studies, including one from our own institution, have evaluated the outcomes in gynecologic oncology patients diagnosed with bowel injury [3-5]. The previous studies have suggested that prognosis is poor in such patients and that management approaches should be carefully considered. This current study specifically identifies those patients with gynecologic cancers in whom an aggressive surgical management of bowel injury may be counterproductive, and thus provides important information to aid decision-making in these difficult clinical situations.

Methods

After obtaining approval from the Institutional Review Board, a retrospective chart review was performed of all patients treated at our institution for gynecologic cancer and intestinal perforation between January 1, 1995 and December 31, 2011. ICD-9 codes were used to identify the study subjects. The following data were abstracted from the patients' charts: demographic information, medical co-morbidities, cancer type and treatment history, date of last contact, and vital status at last follow-up. The details regarding the bowel injury, including presenting symptoms, laboratory values, management, and outcome of the patients, were also recorded. Patients were divided into three groups based on the disease status at the time of perforation as determined by the findings recorded in the CT scan and/or operative reports. Patients with no evidence of disease were placed in one group, those with microscopic disease or localized disease (e.g., an isolated pelvic mass) were in the second group, and patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis, distant metastasis, or both constituted the third group. Bowel injury was diagnosed by either free air on abdominal radiograph or CT scan, evidence of contrast extravasation on a CT scan, or presence of bowel contents in the abdomen on surgical exploration. Patients who underwent a surgical treatment for their cancer were considered to have undergone a cancer-directed surgery. Information on use of radiation and chemotherapy was also collected and included administration of these therapies at any time during the cancer treatment. We also included in our analyses a modified version of the Charlson comorbidity index, which was based on the ten conditions captured from the past medical history of all patients [6].

Statistical analyses were performed by using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institutes, Cary, NC). Simple descriptive statistics were used to describe the study cohort. The Student's t-test was used for the continuous variables, and the Fisher's exact test was used for categorical variables. Survival time was defined from the date of diagnosis of intestinal perforation to the date of last contact or date of death. The Kaplan-Meier method with log-rank and Wilcoxon tests was used for univariate analysis of differences between the groups. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used for multivariate analysis. All p-values reported are two-tailed, and a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

The study group comprised 43 patients. The mean age was 59.4 years (range 38-82 years). The demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort are shown in Table 1. Most patients were white and had a BMI of less than 30. The Charlson co-morbdity index score was 0 in 63% of the patients. The patient population was fairly evenly distributed across different time periods (1995-2000, 2001-2006, and 2007-2011). Ovarian/fallopian tube/primary peritoneal cancers were more common than cancers originating in other parts of the female genital tract. Cancer-directed surgery was performed in 72% of the patients, 49% received radiation treatment, and chemotherapy was administered in about 79% of the patients. A total of 40% of the cohort was treated with both chemotherapy and radiation (either concurrently or at different time points). Most patients had received only one prior regimen at the time of perforation, with platinum/taxane being the most commonly used combination. Although most perforations occurred in the small bowel (49%), the sigmoid colon was involved in 21% of the patients. A large number of the patients (51%) had widespread disease as determined by the presence of peritoneal carcinomatosis, distant metastasis, or both at the time of perforation. Bowel obstruction, either prior or concurrent, was noted in about 56% of the patients. The treatment for perforation was surgical in 65% of the patients and conservative in the remaining 35%. Of the 28 patients who underwent surgery, 4 had failed an initial attempt at conservative management. Surgical procedures performed were abdominal exploration and bowel resection in 19 patients, ileostomy in four patients, colostomy in four patients, and G-tube placement in one patient. Among the 15 patients treated conservatively, 4 had a walled-off collection, 1 declined surgery, and the other 10 were considered unsuitable for surgical management because of their poor performance status, advanced cancer, or both. Conservative management consisted of nasogastric or colonic decompression, bowel rest, intravenous fluid hydration, and administration of antibiotics. Additionally, radiology-guided drainage was performed in five patients.

Table 1. Patient and Disease Characteristics.

| Variable | Number (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age at diagnosis (range) | 59.4 years (38-82 years) | |

| Race | White | 35 (81.4%) |

| Black | 8 (18.6%) | |

| BMI | <30 | 32 (74.4%) |

| ≥30 | 11 (25.6%) | |

| Charlson co-morbidity index | 0 | 27 (62.8%) |

| ≥1 | 16 (37.2%) | |

| Year of diagnosis | 1995-2000 | 11 (25.6%) |

| 2001-2006 | 17 (39.5%) | |

| 2007-2011 | 15 (34.9%) | |

| Cancer type | Uterine | 13 (30.2%) |

| Cervix | 11 (25.6%) | |

| Ovarian/Fallopian tube/Primary peritoneal | 17 (39.5%) | |

| Vulva/Vagina | 2 (4.7%) | |

| Stage | I/II | 16 (37.2%) |

| III/IV | 21 (48.8%) | |

| Unknown | 6 (14.0%) | |

| Cancer-directed surgery | Yes | 31 (72.1%) |

| No | 11 (25.6%) | |

| Unknown | 1 (2.3%) | |

| Radiation | Yes | 21 (48.8%) |

| No | 20 (46.5%) | |

| Unknown | 2 (4.7%) | |

| Chemotherapy | Yes | 34 (79.1%) |

| No | 6 (14.0%) | |

| Unknown | 3 (6.9%) | |

| Chemotherapy Regimen | <2 | 17 (50.0%) |

| ≥2 | 14 (41.2%) | |

| Unknown | 3 (8.8%) | |

| Site of perforation | Small bowel | *21 (48.8%) |

| large bowel | *10 (23.3%) | |

| Sigmoid colon | 9 (20.9%) | |

| Stomach | 1 (2.3%) | |

| Unknown | 4 (9.3%) | |

| Extent of cancer present at the time of perforation | No evidence of disease | 8 (18.6%) |

| Microscopic disease/Localized disease | 10 (23.3%) | |

| Peritoneal carcinomatosis/Distant metastasis | 22 (51.1%) | |

| Unknown | 3 (7.0%) | |

| Ca-125 | <100 | 10 (23.3%) |

| ≥100 | 16 (37.2%) | |

| Unknown | 17 (39.5%) | |

| Prior or concurrent bowel obstruction | Yes | 24 (55.8%) |

| No | 17 (39.5%) | |

| Unknown | 2 (4.7%) | |

| Management of perforation | Conservative | 15 (34.9%) |

| Surgical | 28 (65.1%) | |

Perforation was present in small- and large bowel in 2 patients.

The clinical presentation of the patients was as shown in Table S1. Abdominal pain was the most commonly reported symptom. A large percentage of patients also complained of having nausea and vomiting. Alteration of bowel movements was relatively rare. Similarly, documentation of positive peritoneal signs could be found for only 9% of the patients. Most of the vital signs were normal on admission with the exception of heart rate, which was elevated in a large number of patients. Conversely, abnormalities in the results of the laboratory tests were quite common.

Seven patients received bevacizumab as part of their cancer treatment (Table 2). All had recurrent/progressive disease at the time of initiation of bevacizumab, except one patient who was being treated in a neo-adjuvant setting. Prior or concurrent bowel obstruction was recorded in five out of the seven patients (72%). Similarly, peritoneal carcinomatosis was present in all patients except one, whose primary diagnosis was cervical cancer. Most patients were heavily pretreated, with a median of four prior chemotherapeutic regimens. Two patients (one with cervical cancer and the other with fallopian tube cancer) also received radiation. The median number of bevacizumab cycles received before perforation was one. Treatment of perforation involved surgery in three patients, whereas the remaining four were managed conservatively. Major complications in the form of sepsis, shock, and respiratory distress occurred in two out of the three patients in the surgery group and one out of the four patients in the no-surgery group. The three patients treated surgically died at 26 days, 56 days, and 58 days post-surgery. Of the four patients treated conservatively, one was still alive at last follow-up (2.7 years); the other three died at 3 days, 34 days, and 126 days after diagnosis.

Table 2. Clinical Characteristics of Patients with Bevacizumab-Associated Gastrointestinal Perforation.

| Patient number |

Age | Cancer Type (stage) |

Prior cytotoxic regimens |

Prior bowel surgery |

Prior or concurrent bowel obstruction | Disease status at the time of initiation of bevacizumab | Peritoneal carcinomatosis | CA-125 | Number of bevacizumab cycles before perforation | Site of perforation | Management of perforation | Follow-up in days | Vital status at last follow -up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 51 | Ovary (III) | 4 | No | Yes | Recurrent/Progressive | Yes | 984 | 1 | Small bowel | Conservative | 126 | Dead |

| 2 | 56 | Cervix (II) | 2 | No | No | Recurrent/Progressive | No | N/A | 4 | Small bowel | Conservative | 972 | Alive |

| 3 | 60 | Uterus (IV) | 4 | No | Yes | Recurrent/Progressive | Yes | 1067 | 1 | Small bowel | Conservative | 3 | Dead |

| 4 | 44 | Ovary (I) | 5 | Yes | Yes | Recurrent/Progressive | Yes | 89 | 3 | Large bowel | Surgical | 56 | Dead |

| 5 | 62 | Ovary (III) | 1 | No | Yes | Recurrent/Progressive | Yes | 273 | 5 | Unknown | Conservative | 34 | Dead |

| 6 | 74 | Primary Peritoneal (Unknown) | 4 | Yes | No | Recurrent/Progressive | Yes | 343 | 1 | Sigmoid colon | Surgical | 26 | Dead |

| 7 | 77 | Ovary (IV) | 0 | No | Yes | New diagnoses | Yes | 2038 | 1 | Small bowel | Surgical (Failed conservative) | 58 | Dead |

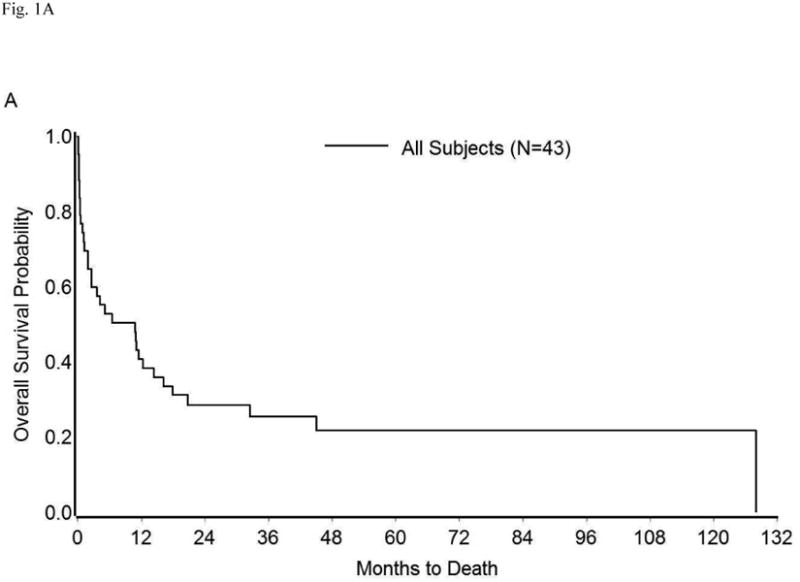

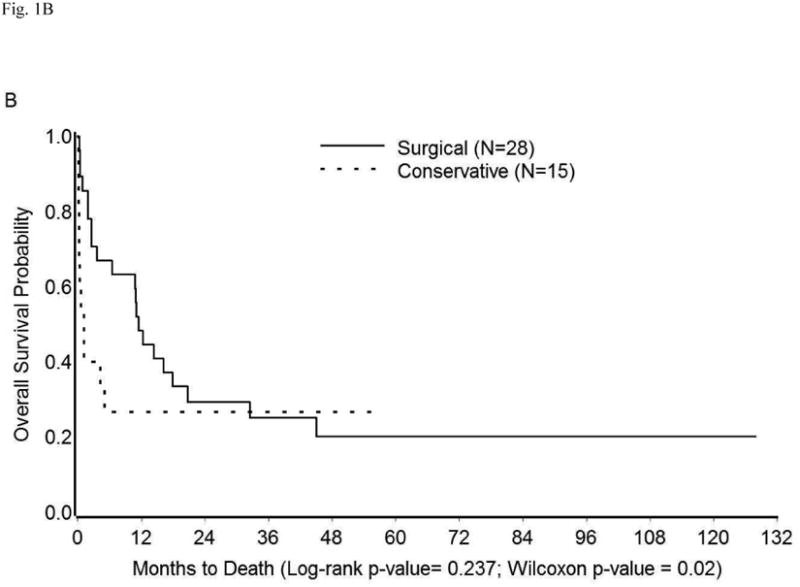

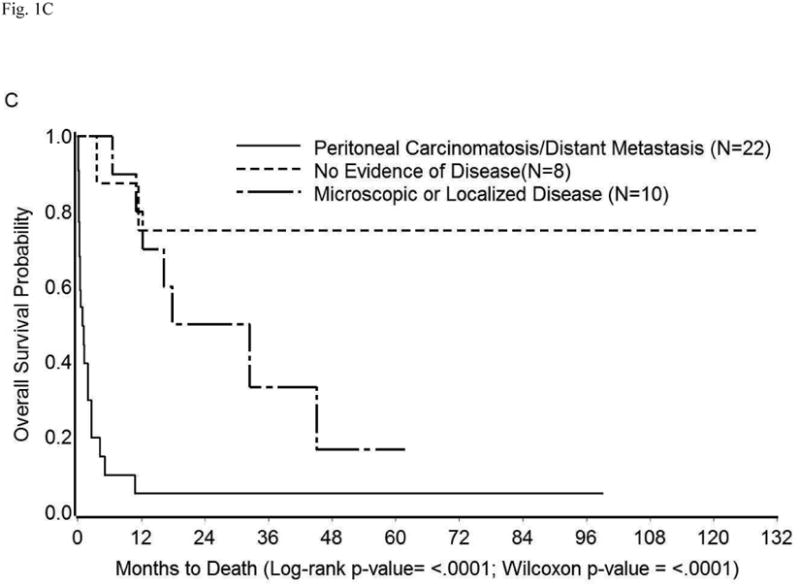

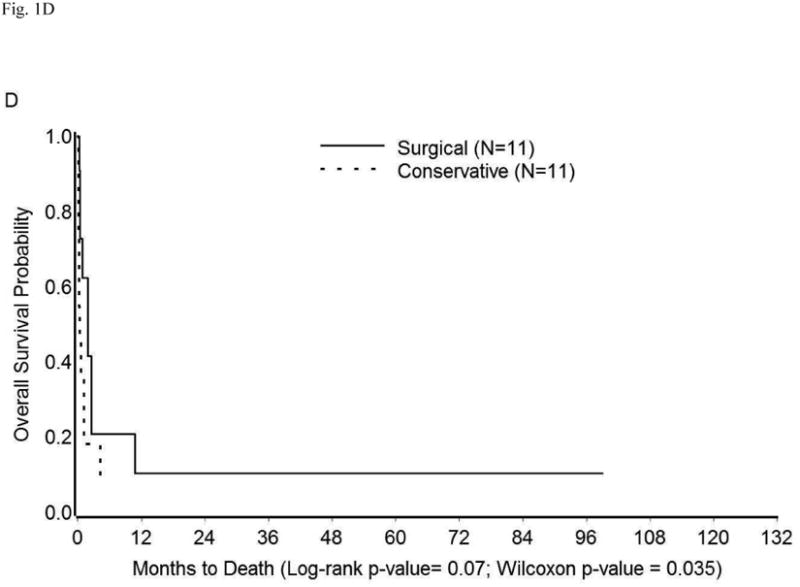

The survival in the entire cohort was as shown in Figure 1A. Overall mortality at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months was 26%, 40%, 47%, and 59%, respectively. The median survival was 10.73 months (95% CI: 1.93-16.17 months). The impact on survival of various demographic and clinico-pathologic factors (described in Tables 1 and S1) was assessed in univariate analysis. Compared to surgical treatment, conservative management of perforation was associated with significantly shorter survival (median survival 11.43 months vs. 1.93 months, p=0.02) (Table 3, Figure 1B). Similarly, an extensive cancer burden at the time of perforation portended poor outcomes. Specifically, survival time was significantly shorter among patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis, metastatic disease, or both (median survival: 0.87 months) than among those with localized disease/microscopic disease (median survival: 25.13 months), or no evidence of disease (median survival: 128.07 months, p<0.0001) (Table 3, Figure 1C). Other factors found significantly correlated with poor survival were performance of cancer-directed surgery, higher number of chemotherapy regimens, advanced cancer stage, and high CA-125 levels (p<0.05) (Table 3). On multivariate analysis, only extent of cancer at the time of perforation was found to be an independent predictor of survival (Table 4). The risk of death in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis, distant metastasis, or both was 42-fold higher than in those with no evidence of disease at the time of perforation (95% CI: 3.28-639.83, p<0.05), and 7-fold higher than in those with microscopic/localized disease (95% CI: 1.77-29.94, p<0.05). Importantly, when adjusted for the extent of disease spread, management of perforation was not a significant predictor of survival (p≥0.05) (Table 4). The survival among patients with widely metastatic disease was poor irrespective of the management approach used (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier Overall Survival in (A) Entire cohort; (B) Entire cohort by management approach; (C) Entire cohort (except three who were excluded because cancer extent was unknown) by extent of cancer present at the time of perforation; (D) Patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis, distant metastasis, or both by management approach.

Table 3. Univariate Analysis of Factors Associated with Survival.

| Variable | Median survival in months (95% CI) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log-Rank | Wilcoxon | |||

| Management of perforation | Surgical (n=28) | 11.43 (2.60-20.77) | 0.24 | 0.02 |

| Conservative (n=15) | 1.93 (0.20-**) | |||

| Extent of cancer present at the time of perforation | No evidence of disease (n=8) | 128.07 (3.57-128.07) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Microscopic disease/Localized disease (n=10) | 25.13 (6.47-**) | |||

| Peritoneal carcinomatosis/Distant metastasis (n=22) | 0.87 (0.30-1.93) | |||

| Cancer-directed surgery | Yes (n=31) | 4.20 (1.13-12.23) | 0.02 | 0.06 |

| No (n=11) | 128.07 (0.40-128.07) | |||

| Number of chemotherapy regimens | <2 (n=17) | 16.17 (3.57-**) | 0.03 | 0.004 |

| ≥2 (n=14) | 0.87 (0.20-1.87) | |||

| None/Unknown (n=12) | 10.92 (0.40-32.43) | |||

| Stage | I/II (n=16) | 32.43 (6.47-128.07) | 0.002 | 0.005 |

| III/IV (n=21) | 2.57 (0.40-10.97) | |||

| Unknown (n=6) | 1.73 (0.10-17.83) | |||

| CA-125 | <100 (n=10) | 10.87 (0.40-**) | 0.004 | 0.002 |

| ≥100 (n=16) | 1.17 (0.20-4.20) | |||

| Unknown (n=17) | 17.83 (3.57-128.07) | |||

Number of events too small to obtain an estimate.

Both log-rank and Wilcoxon methods were used for statistical analysis as the data were not normally distributed due to a small sample size.

Table 4. Multivariate Analysis of Factors Associated with Survival.

| Variable | Multivariate Analysis Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Management of perforation | Conservative (n=15)) | Referent |

| Surgical (n=28) | 0.88 (0.32-2.57) | |

| Extent of cancer present at time of perforation | No evidence of disease (n=8) | Referent |

| Microscopic disease/Localized disease (n=10) | 6.13 (0.78-60.11) | |

| Peritoneal carcinomatosis/Distant metastasis (n=22) | *42.20 (3.28-639.83) | |

| Cancer-directed surgery | No (n=11) | Referent |

| Yes (n=31) | 0.54 (0.08-4.74) | |

| Number of Chemotherapy regimens | <2 (n=17) | Referent |

| ≥2 (n=14) | 0.92 (0.27-3.25) | |

| None/Unknown (n=12) | 0.29 (0.07-1.22) | |

| Stage | I/II (n=16) | Referent |

| III/IV (n=21) | 0.98 (0.22-5.53) | |

| Unknown (n=6) | 2.23 (0.34-18.29) | |

| CA-125 | <100 (n=10) | Referent |

| ≥100 (n=16) | 1.90 (0.51-7.29) | |

| Unknown (n=17) | 1.21 (0.21-6.52) | |

p<0.05

The hospital course of patients who underwent conservative versus surgical management of perforation was also examined (Table 5). The length of hospital stay was significantly longer for patients who underwent surgical treatment than for those managed conservatively (19 days vs. 7 days, p=0.002). Similarly, more patients in the surgery group than in the no-surgery group developed complications (75% vs. 26.7 %, p=0.004). Admission to the Intensive Care Unit was also significantly more common among the patients who underwent surgical intervention than among their non-surgically managed counterparts (68% vs. 20%, p=0.004).

Table 5. Comparison of Hospital Course of Patients Treated with Conservative versus Surgical Management.

| Variable | Conservative (n=15) | Surgical (n=28) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean length of hospital stay in days (range) | 7 (2-16) | 19 (6-74) | 0.002 | |

| Complications | None | 11 (73.3%) | 7 (25.0%) | 0.004 |

| Shock | 2 (13.3%) | 6 (21.4%) | 0.69 | |

| Sepsis | 3 (20.0%) | 12 (42.9%) | 0.19 | |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0 | 3 (10.7%) | 0.54 | |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 1 (6.7%) | 9 (32.1%) | 0.13 | |

| Febrile morbidity/Infection | 0 | 4 (14.3%) | 0.28 | |

| Altered mental status | 2 (13.3%) | 1 (3.6%) | 0.28 | |

| Coagulopathy | 0 | 1 (3.6%) | 1.0 | |

| Ischemic complications | 0 | 3 (10.7%) | 0.54 | |

| Other | 0 | 3 (10.7%) | 0.54 | |

| Intensive Care Unit admission | 3 (20.0%) | 19 (67.9%) | 0.004 | |

After recovering from their bowel perforation, a total of nine patients went on to receive further chemotherapy; all except one had undergone surgical management of their bowel perforation. Of these, eight patients survived for at least one year.

Discussion

Our results indicate that bowel injury in the form of intestinal perforation carries a grave prognosis in patients with gynecologic malignancies. The biggest determinant of survival in these patients is the amount of cancer burden present at the time of perforation. Of the 22 patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis or distant metastasis, only 4 lived beyond three months. Disease status at the time of perforation has been shown to be an important prognostic factor by other investigators as well [3, 4]. In our cohort, the survival among patients with widely metastatic disease was poor regardless of the management approach used (conservative vs. surgical) (Fig 1D). On the other hand, more patients in the surgery group experienced major complications, including ICU admission, than did those who were treated conservatively. This is not surprising as often such patients are of advanced age and have a poor functional reserve, thus placing them at increased risk for post-operative complications. The length of hospital stay was also significantly longer in the surgery group. This is particularly important as prolonged hospitalization not only increases the incidence of adverse consequences such as delirium, nosocomial infections, and medication errors or adverse interactions, but also diminishes the quality of life of these patients. Other studies have found that when surveyed, all patients with imminent death chose home as their preferred place of death. The main reasons cited were a preference for being in a comfortable home environment, spending time with their families, and living a more “normal life” [7]. Taken together, these results strongly argue in favor of pursuing a conservative approach among patients known to have extensive disease at the time of perforation.

Bevacizumab is associated with a higher perforation rate in patients with ovarian cancer than in those with other cancer types (e.g., colorectal, pancreatic, non-small cell lung, breast cancer) [8-12]. In the current study, at least 15% of the perforations were related to the use of bevacizumab. Most patients were heavily pretreated, had peritoneal carcinomatosis, and had a history of either prior or concurrent bowel obstruction; these factors are all known to increase the risk of bowel perforation [13-15]. Administration of bevacizumab further increases the susceptibility for bowel perforation by promoting tumor regression/necrosis, or compromising the structure and function of the gastrointestinal vasculature, including possible generation of micro-emboli [8, 16-22]. Considering that multiple clinical trials have demonstrated the effectiveness of bevacizumab in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer [9, 12, 23, 24], identification of suitable candidates on the basis of clinical risk factors will help minimize the associated adverse events. In our study, only one patient in the bevacizumab-treated group survived beyond 6 months. This patient did not have peritoneal carcinomatosis or distant metastasis and underwent a conservative management. This suggests that the same conservative paradigm as described above for the management of gynecologic oncology patients diagnosed with perforation might apply to the management of bowel injury resulting from treatment with bevacizumab.

Although our study addresses an important question, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, it is a retrospective study with all its inherent biases. Additionally, because of the small number of subjects included, our study may be underpowered to detect differences in some of the outcomes examined, and the possibility of a type II error cannot be reliably excluded. Finally, although a co-morbidity index was incorporated in the analyses, performance status at the time of diagnosis of perforation could not be obtained. Performance status scores are based on a patient's ability to perform daily tasks and therefore, provide a better measure of functional impairment or so called “patient frailty”. Since frailty has been shown to be predictive of surgical outcomes in older patients [25, 26], the lack of adjustment for it might have influenced some of our results.

In summary, bowel injury in patients with gynecologic cancers portends a poor outcome. The main determinant of survival in these patients is the extent of disease at the time of perforation. Among patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis or distant metastasis, survival is notably poor irrespective of the type of management approach pursued. In discussions between the physician and the patient or family, due consideration should be given to the amount of cancer present at the time of diagnosis and the likelihood of the patient deriving benefit from aggressive surgery.

Supplementary Material

Research Highlights.

Bowel injury in patients with gynecological cancers portends a poor prognosis.

The main determinant of survival is the extent of disease at the time of perforation.

Surgical management is unlikely to benefit patients with widely metastatic disease.

Acknowledgments

“The Siteman Cancer Center is supported by NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA91842”.

“The CTSA award grant UL1RR024992”

We thank Deborah J. Frank for constructive criticism of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosure: None of the authors have a conflict of interest

Conflict of interest statement: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Gunjal Garg, Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Washington University School of Medicine and Siteman Cancer Center, St. Louis, MO, USA.

L. Stewart Massad, Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Washington University School of Medicine and Siteman Cancer Center, St. Louis, MO, USA.

Shabnam Pourabolghasem, Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Washington University School of Medicine and Siteman Cancer Center, St. Louis, MO, USA.

Gongfu Zhou, Division of Biostatistics, Washington University School of Medicine and Siteman Cancer Center, St. Louis, MO, USA.

Matthew A. Powell, Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Washington University School of Medicine and Siteman Cancer Center, St. Louis, MO, USA.

Premal H. Thaker, Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Washington University School of Medicine and Siteman Cancer Center, St. Louis, MO, USA.

Andrea R. Hagemann, Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Washington University School of Medicine and Siteman Cancer Center, St. Louis, MO, USA.

Ivy Wilkinson-Ryan, Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Washington University School of Medicine and Siteman Cancer Center, St. Louis, MO, USA.

David G. Mutch, Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Washington University School of Medicine and Siteman Cancer Center, St. Louis, MO, USA.

References

- 1.Bielecki K, Kaminski P, Klukowski M. Large bowel perforation: morbidity and mortality. Tech Coloproctol. 2002;6:177–82. doi: 10.1007/s101510200039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orringer RD, Coller JA, Veidenheimer MC. Spontaneous free perforation of the small intestine. Dis Colon Rectum. 1983;26:323–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02561708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horowitz NS, Cohn DE, Herzog TJ, Mutch DG, Rader JS, Bhalla S, Gibb RK. The significance of pneumatosis intestinalis or bowel perforation in patients with gynecologic malignancies. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;86:79–84. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2002.6728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tung CS, Sun CC, Schlumbrecht MP, Meyer LA, Bodurka DC. Survival after intestinal perforation: can it be predicted? Gynecol Oncol. 2009;115:349–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramirez PT, Levenback C, Burke TW, Eifel P, Wolf JK, Gershenson DM. Sigmoid perforation following radiation therapy in patients with cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;82:150–5. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang ST. When death is imminent: where terminally ill patients with cancer prefer to die and why. Cancer Nurs. 2003;26:245–51. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200306000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hapani S, Chu D, Wu S. Risk of gastrointestinal perforation in patients with cancer treated with bevacizumab: a meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:559–68. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cannistra SA, Matulonis UA, Penson RT, Hambleton J, Dupont J, Mackey H, Douglas J, Burger RA, Armstrong D, Wenham R, McGuire W. Phase II study of bevacizumab in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer or peritoneal serous cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5180–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.0782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright JD, Hagemann A, Rader JS, Viviano D, Gibb RK, Norris L, Mutch DG, Powell MA. Bevacizumab combination therapy in recurrent, platinum-refractory, epithelial ovarian carcinoma: A retrospective analysis. Cancer. 2006;107:83–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Badgwell BD, Camp ER, Feig B, Wolff RA, Eng C, Ellis LM, Cormier JN. Management of bevacizumab-associated bowel perforation: a case series and review of the literature. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:577–82. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nimeiri HS, Oza AM, Morgan RJ, Friberg G, Kasza K, Faoro L, Salgia R, Stadler WM, Vokes EE, Fleming GF Chicago Phase IIC, Consortium PMHPI, California Phase IIC. Efficacy and safety of bevacizumab plus erlotinib for patients with recurrent ovarian, primary peritoneal, and fallopian tube cancer: a trial of the Chicago, PMH, and California Phase II Consortia. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;110:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richardson DL, Backes FJ, Hurt JD, Seamon LG, Copeland LJ, Fowler JM, Cohn DE, O'Malley DM. Which factors predict bowel complications in patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer being treated with bevacizumab? Gynecol Oncol. 2010;118:47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanyi JL, McCann G, Hagemann AR, Coukos G, Rubin SC, Liao JB, Chu CS. Clinical predictors of bevacizumab-associated gastrointestinal perforation. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;120:464–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Randall LM, Monk BJ. Bevacizumab toxicities and their management in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;117:497–504. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lordick F, Geinitz H, Theisen J, Sendler A, Sarbia M. Increased risk of ischemic bowel complications during treatment with bevacizumab after pelvic irradiation: report of three cases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:1295–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamba T, Tam BY, Hashizume H, Haskell A, Sennino B, Mancuso MR, Norberg SM, O'Brien SM, Davis RB, Gowen LC, Anderson KD, Thurston G, Joho S, Springer ML, Kuo CJ, McDonald DM. VEGF-dependent plasticity of fenestrated capillaries in the normal adult microvasculature. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H560–76. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00133.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y, Fei D, Vanderlaan M, Song A. Biological activity of bevacizumab, a humanized anti-VEGF antibody in vitro. Angiogenesis. 2004;7:335–45. doi: 10.1007/s10456-004-8272-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heinzerling JH, Huerta S. Bowel perforation from bevacizumab for the treatment of metastatic colon cancer: incidence, etiology, and management. Curr Surg. 2006;63:334–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cursur.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gray J, Murren J, Sharma A, Kelley S, Detterbeck F, Bepler G. Perforated viscus in a patient with non-small cell lung cancer receiving bevacizumab. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:571–3. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31805fea51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abbrederis K, Kremer M, Schuhmacher C. Ischemic anastomotic bowel perforation during treatment with bevacizumab 10 months after surgery. Chirurg. 2008;79:351–5. doi: 10.1007/s00104-007-1339-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mir O, Mouthon L, Alexandre J, Mallion JM, Deray G, Guillevin L, Goldwasser F. Bevacizumab-induced cardiovascular events: a consequence of cholesterol emboli syndrome? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:85–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia AA, Hirte H, Fleming G, Yang D, Tsao-Wei DD, Roman L, Groshen S, Swenson S, Markland F, Gandara D, Scudder S, Morgan R, Chen H, Lenz HJ, Oza AM. Phase II clinical trial of bevacizumab and low-dose metronomic oral cyclophosphamide in recurrent ovarian cancer: a trial of the California, Chicago, and Princess Margaret Hospital phase II consortia. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:76–82. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burger RA, Sill MW, Monk BJ, Greer BE, Sorosky JI. Phase II trial of bevacizumab in persistent or recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer or primary peritoneal cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5165–71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farhat JS, Velanovich V, Falvo AJ, Horst HM, Swartz A, Patton JH, Jr, Rubinfeld IS. Are the frail destined to fail? Frailty index as predictor of surgical morbidity and mortality in the elderly. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72:1526–30. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182542fab. discussion 1530-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Makary MA, Segev DL, Pronovost PJ, Syin D, Bandeen-Roche K, Patel P, Takenaga R, Devgan L, Holzmueller CG, Tian J, Fried LP. Frailty as a predictor of surgical outcomes in older patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:901–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.