Abstract

An 84-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with fever, jaundice, and itching. He had been diagnosed previously with chronic renal failure and diabetes, and had been taking allopurinol medication for 2 months. A physical examination revealed that he had a fever (38.8℃), jaundice, and a generalized maculopapular rash. Azotemia, eosinophilia, atypical lymphocytosis, elevation of liver enzymes, and hyperbilirubinemia were detected by blood analysis. Magnetic resonance cholangiography revealed multiple cysts similar to choledochal cysts in the liver along the biliary tree. Obstructive jaundice was suspected clinically, and so an endoscopic ultrasound examination was performed, which ruled out a diagnosis of obstructive jaundice. The patient was diagnosed with DRESS (Drug Rash with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms) syndrome due to allopurinol. Allopurinol treatment was stopped and steroid treatment was started. The patient died from cardiac arrest on day 15 following admission.

Keywords: DRESS syndrome, Allopurinol, Jaundice

INTRODUCTION

Drug Rash with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS) syndrome is an extremely serious adverse effect caused by medications, characterized by skin rash, fever, and lymphadenopathy. It generally occurs 2 to 4 weeks after treatment with the reactive medication.1 It occurs most often with the use of anticonvulsants such as phenytoin and phenobarbital, though it can also be caused by sulphasalazine, nevirapine, penicillamine, and allopurinol.1,2 Allopurinol is generally considered a safe treatment medication commonly used to protect renal function by dropping proteinuria and blood pressure when administered in low doses to patients with mild degrees of chronic renal disease.3 We report a case of a patient who had been taking low-dose allopurinol for several months due to chronic renal disease, was admitted to the emergency room with a complaint of jaundice, and was diagnosed with DRESS syndrome after confirming there was no bile duct obstruction according to endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRC).

CASE REPORT

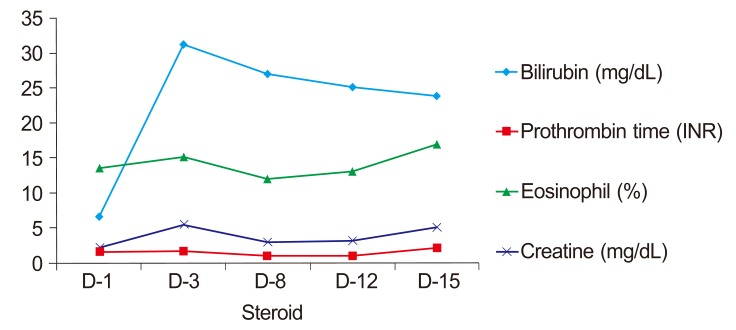

An 84 year old patient was admitted to the emergency room in our hospital with complaints of fever and jaundice. Two months ago, this patient was diagnosed with stage 3 chronic renal disease and prescribed allopurinol 100 mg/day and torasemide 2.5 mg/day. His vital signs upon admission to the emergency room were 170/70 mmHg for blood pressure, 80/min for pulse rate, 20/min for respiratory rate, and 38.8℃ for body temperature. Consciousness was clear, and severe scleral jaundice and systemic diffuse types of papule were observed (Fig. 1). According to peripheral blood tests, leukocytes were 6,020/µL (atypical lymphocyte 4%), eosinophil count was 840/µL (13.6%), hemoglobin was 13.3 g/dL, and platelet count was 64,000/µL. Blood chemical tests showed a blood urea nitrogen level of 48.4 mg/dL, serum creatinine of 2.2 mg/dL, AST/ALT of 140/343 U/L, alkaline phosphatase of 210 U/L, total bilirubin of 6.6 mg/dL, direct bilirubin of 4.7 mg/dL, and a prothrombin time of 55% (INR 1.52). According to serum tests, all HBsAg, including Anti-HBs and Anti-HCV, were negative. An electrocardiography was within the normal limits. The patient's previously normal liver function and creatinine levels were slightly elevated (1.3-1.5 mg/dL).

Figure 1.

Skin lesion. Generalized variably sized erythematous macules were evident.

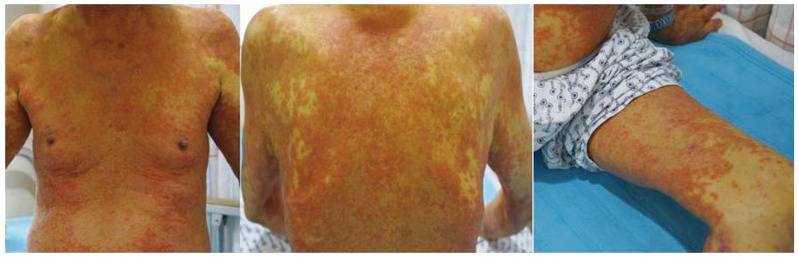

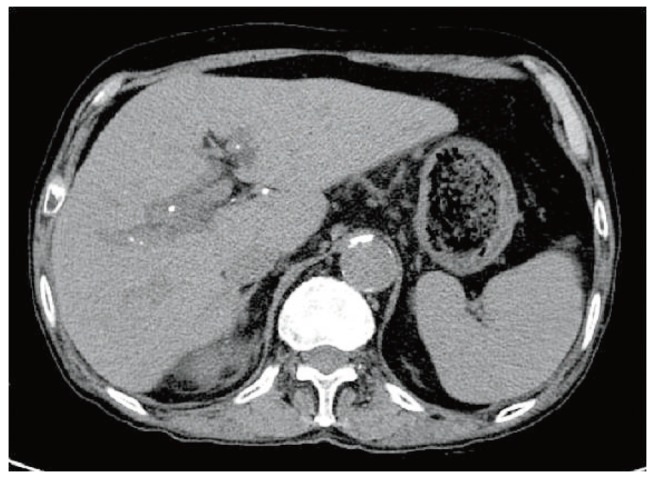

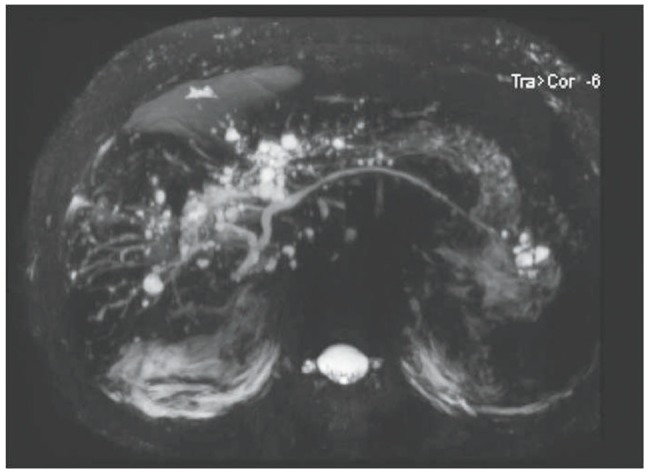

Obstructive jaundice was clinically suspected; therefore, non-enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) was performed to rule this out. We were unable to use a contrast medium due to potential nephrotoxicity. The CT scan showed multiple calcifications along the periportal areas of both hepatic lobes and the hepatic hilum (Fig. 2). We suspected biliary obstruction due to intrahepatic bile duct stones. The patient was hospitalized and underwent MRC. No bile duct obstructions or calcifications were detected, but multiple cysts were seen in the liver along the biliary tree (Fig. 3). An EUS was then performed to rule out obstructive jaundice, but this did not reveal any evidence of biliary obstruction. The numbers of atypical lymphocytes increased to 6% 3 days after admission, and both liver function and renal function worsened, showing serum creatinine of 5.5 mg/dL, total bilirubin of 31.3 mg/dL, direct bilirubin of 21.5 mg/dL, and AST/ALT of 155/303 U/L. A diagnosis of DRESS syndrome was made, and methylprednisolone 40 mg/day was administered. Serial changes in laboratory findings are shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 2.

Nonenhanced abdominal computed tomography revealed multiple calcifications along the periportal areas of both hepatic lobes and the hepatic hilum.

Figure 3.

Magnetic resonance cholangiography revealed multiple cysts in the liver along the biliary tree.

Figure 4.

The clinical course of the patient, showing bilirubin, prothrombin-time, eosinophils, and creatine values.

Although the patient was slightly improved 8 days later, with serum creatinine of 3.0 mg/dL, AST/ALT of 53/30 U/L, total bilirubin of 27.1 mg/dL, direct bilirubin of 19.4 mg/dL, and prothrombin time of 98% (INR 1.01), liver function and renal function deteriorated again 15 days later (13 days after methylprednisolone administration), and the patient complained of chest pain. An electrocardiography revealed sinus tachycardia; cardiac enzymes were elevated (Troponin I 0.08 µg/L). Shortly thereafter, the patient died from sudden cardiac arrest.

DISCUSSION

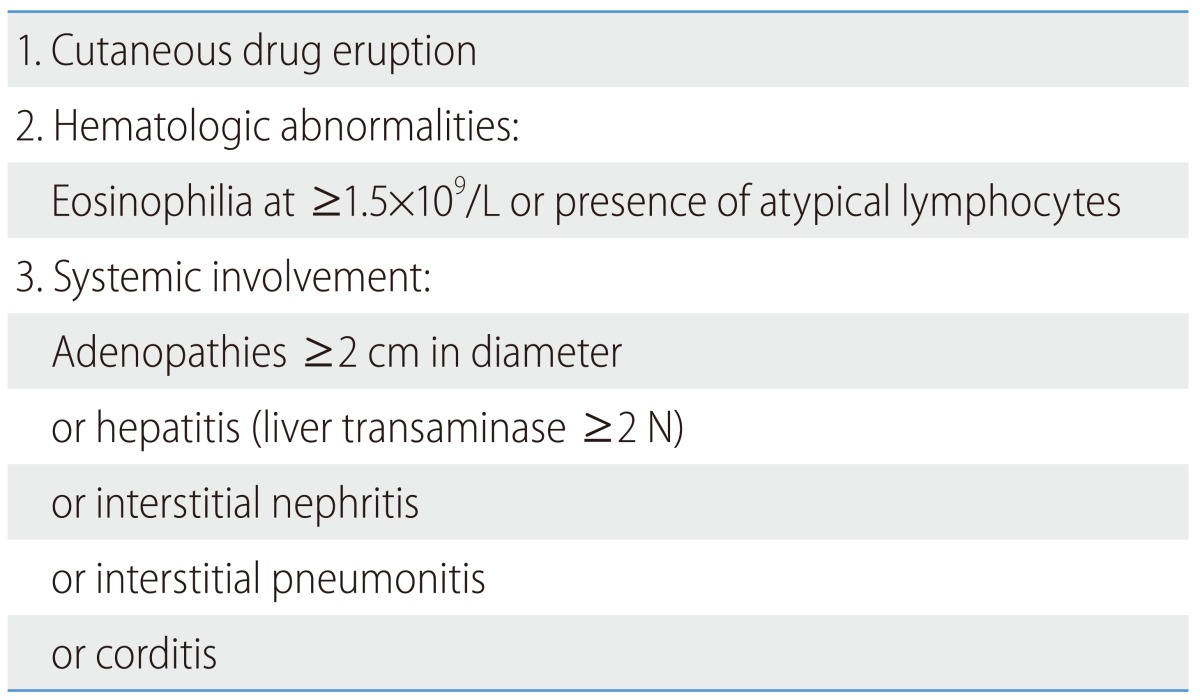

DRESS syndrome is a relatively rare disease caused by an adverse reaction to medications, referred to sometimes as drug hypersensitivity syndrome (DHS). It is characterized by a skin rash, lymphadenopathy, fever, and single- or multiple-organ involvement. In terms of hematology, eosinophilia and atypical lymphocytes are observed, and patchy papules appear over the skin of the entire body.4 It typically manifests 4 to 6 weeks after administering the associated medication. Bocquet et al5 suggested diagnosis criteria of DRESS syndrome (Table 1); when all three items are satisfied, DRESS is diagnosed. It is reasonable to conclude the diagnosis criteria are applicable to this case. The death rate is approximately 10%, and the most common cause of death is hepatic failure. The most common medications that cause DRESS syndrome are phenytoin, phenobarbital, carbamazepine, sulphasalazine, and allopurinal (as in this case).

Table 1.

Suggested criteria for the diagnosis of Drug Rash with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS) according to Bocquet et al.5

*The proposed classification is based on three criteria, such that a person is considered to have DRESS if three criteria are present.

There is some confusion regarding the diagnosis of DRESS syndrome vs. Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS)/toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN),6 although the skin lesions in SJS/TEN are different from those in DRESS. DRESS typically begins with a maculopapular rash, which progresses to an erythroderma or exfoliative dermatitis, often with edema on the face and limbs.7 A bullous appearance, which is caused by subepidermal edema and is not due to extensive necrosis of keratinocytes, may be observed in some cases. There is no hemorrhagic mucocutaneous involvement, as seen in SJS/TEN.

Cell-mediated immunity (type IV reaction) directed toward allopurinol, and more importantly, to its oxypurinol metabolite, is the mechanism involved in the pathogenesis of allopurinol-induced DRESS syndrome.8,9 This is supported by the fact that most patients with hypersensitivity to this drug developed the illness 4-6 weeks after the initiation of drug therapy. The pathophysiology of allopurinol-associated DRESS syndrome seems to be related to the accumulation of oxypurinol in patients with renal insufficiency. Hande and co-workers10 showed that the renal clearance of oxypurinol is directly proportional to the renal clearance of creatinine.

Patients with chronic renal failure and simultaneous use of diuretics, mainly thiazides, are at greatest risk for developing allopurinol-induced toxicity.11 By impairing allopurinol clearance, they increase allopurinol levels and may impair, as previously suggested, oxypurinol clearance.12

Hyperuricemia is known as one of the aggravating factors of chronic renal disease. Allopurinol administration in low doses is generally safe for patients with mild-to-moderate chronic renal disease and protects renal function by dropping proteinuria and blood pressure.13 For this reason, many chronic renal disease patients take allopurinol. However, there have been some reports14 that DRESS syndrome occurs in about 0.4% patients taking allopurinol, and the death rate in this case is 25%, which is significantly higher than that of DRESS syndrome induced by other medications.1 Many physicians are unaware of serious adverse events due to allopurinol-induced DRESS syndrome and thus forget adequate explanations, which can lead to lots of problems.

Arellano et al12 reported that out of 101 cases of DRESS syndrome, fever occurred in 95.1% of patients, skin rash in 93.1%, and eosinophilia in 93.1%. However, because the patient in this case complained of jaundice and blood tests revealed a direct bilirubin increase, it was necessary to exclude other diseases that could cause obstructive jaundice; consequently, EUS and MRC were performed to determine whether there was a bile duct obstruction, and DRESS syndrome was subsequently able to be diagnosed. An et al15 report a case of DRESS syndrome due to antibiotics and/or antiviral treatment following hepatitis A. By comparison, in this case, jaundice-presenting DRESS syndrome was mistaken for a bile duct obstruction.

The most important treatment for DRESS syndrome caused by medications is to discontinue medications as soon as possible. Chopra et al16 and Vittorio et al17 report that the potentially controversial use of steroids sometimes results in dramatic improvements in clinical symptoms and hematological examination findings after their use, while Markel et al2 report that caution should be given regarding potential recurrence after reducing steroid dosages. Although complete cure was not achieved, steroid treatment resulted in some improvements in laboratory and clinical situations during early periods of DRESS. Even though it has been reported that most DRESS syndrome deaths are due to liver damage,1 there have been reported cases of death caused by cardiac attack occurring due to fulminant myocarditis.18 The patient in this case indicated chest pain on the day of his death, there was a finding of increased Troponin I in blood tests right before death occurred, and the patient died from a sudden cardiac attack; consequently, it is assumed that his death was caused by cardiac damage that occurred due to DRESS syndrome. In hypersensitivity myocarditis, electrocardiography evaluation often shows nonspecific ST segments, T-wave abnormalities, conduction delays, or sinus tachycardia. Elevation of cardiac enzymes also occurs, and echocardiography shows systolic dysfunction and occasional pericardial perfusions. Sudden cardiac death has also been reported.19,20 In hypersensitivity myocarditis, an eosinophilic and a mixed lymphohistiocytic infiltrate without necrosis or fibrosis is seen.20 But, the diagnosis of myocarditis is still largely based on clinical criteria using ECG, echocardiography, and cardiac enzymes rather than biopsy.

In conclusion, allopurinol is a relatively safe medication; however, when DRESS syndrome occurs, it can be fatal. Therefore, close observation is required, along with adequate education, after its administration. In particular, if jaundice and fever are indicated as main symptoms, as seen in this case, there may be a potential delay in the diagnosis of DRESS; thus special cautions should be taken regarding the medication histories and symptoms of patients.

Abbreviations

- CT

computed tomography

- DRESS

drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms

- EUS

endoscopic ultrasound

- MRC

magnetic resonance cholangiography

- SJS

stevens-Johnson syndrome

- TEN

toxic epidermal necrolysis

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Tas S, Simonart T. Management of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome): an update. Dermatology. 2003;206:353–356. doi: 10.1159/000069956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Markel A. Allopurinol-induced DRESS syndrome. Isr Med Assoc J. 2005;7:656–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siu YP, Leung KT, Tong MK, Kwan TH. Use of allopurinol in slowing the progression of renal disease through its ability to lower serum uric acid level. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;47:51–59. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim BJ, Kim MN, Ro BI, Song KY. A case of allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome. Korean J Dermatol. 2003;41:251–254. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bocquet H, Bagot M, Roujeau JC. Drug-induced pseudolymphoma and drug hypersensitivity syndrome (Drug Rash with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms: DRESS) Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1996;15:250–257. doi: 10.1016/s1085-5629(96)80038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolf R, Matz H, Marcos, Orion E. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms vs. toxic epidermal necrolysis: the dilemma of classification. Clin Dermatol. 2005;23:311–314. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shiohara T, Inaoka M, Kano Y. Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS): a reaction induced by a complex interplay among herpesviruses and antiviral and antidrug immune responses. Allergol Int. 2006;55:1–8. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.55.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lockard O, Jr, Harmon C, Nolph K, Irvin W. Allergic reaction to allopurinol with cross-reactivity to oxypurinol. Ann Intern Med. 1976;85:333–335. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-85-3-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braden GL, Warzynski MJ, Golightly M, Ballow M. Cell-mediated immunity in allopurinol-induced hypersensitivity. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1994;70:145–151. doi: 10.1006/clin.1994.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hande KR, Noone RM, Stone WJ. Severe allopurinol toxicity. Description and guidelines for prevention in patients with renal insufficiency. Am J Med. 1984;76:47–56. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(84)90743-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young JL, Boswell RB, Nies AS. Severe allopurinol hypersensitivity. Association with thiazides and prior renal compromise. Arch Intern Med. 1974;134:553–558. doi: 10.1001/archinte.134.3.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arellano F, Sacristan JA. Allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome: a review. Ann Pharmacother. 1993;27:337–343. doi: 10.1177/106002809302700317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wortmann RL. Disorders of purine and pyrimidine metabolism. In: Brownwald E, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, editors. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 15th ed. Vol 2. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2005. pp. 2268–2273. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singer JZ, Wallace SL. The allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome. Unnecessary morbidity and mortality. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29:82–87. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.An J, Lee JH, Lee H, Yu E, Lee DB, Shim JH, et al. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome following cholestatic hepatitis A: a case report. Korean J Hepatol. 2012;18:84–88. doi: 10.3350/kjhep.2012.18.1.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chopra S, Levell NJ, Cowley G, Gilkes JJ. Systemic corticosteroids in the phenytoin hypersensitivity syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:1109–1112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vittorio CC, Muglia JJ. Anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:2285–2290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bourgeois GP, Cafardi JA, Groysman V, Pamboukian SV, Kirklin JK, Andea AA, et al. Fulminant myocarditis as a late sequela of DRESS: two cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:889–890. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taliercio CP, Olney BA, Lie JT. Myocarditis related to drug hypersensitivity. Mayo Clin Proc. 1985;60:463–468. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)60870-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burke AP, Saenger J, Mullick F, Virmani R. Hypersensitivity myocarditis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1991;115:764–769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]