Abstract

Background

The steroid hormone, progesterone, inhibits contractions of the pregnant uterus at all gestations. Antiprogestins (including mifepristone) have been developed to antagonise the action of progesterone, and have a recognised role in medical termination of early or mid‐trimester pregnancy. Animal studies have suggested that mifepristone may also have a role in inducing labour in late pregnancy.

Objectives

To determine the effects of mifepristone for third trimester cervical ripening or induction of labour.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register and reference lists of relevant papers (May 2009).

Selection criteria

Clinical trials comparing mifepristone used for third trimester cervical ripening or labour induction with placebo/no treatment or other labour induction methods.

Data collection and analysis

A strategy was developed to deal with the large volume and complexity of trial data relating to labour induction. This involved a two‐stage method of data extraction. For this update, two review authors independently assessed trial quality and extracted data.

Main results

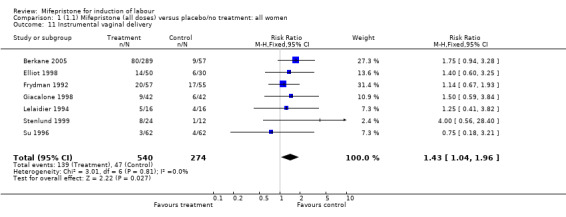

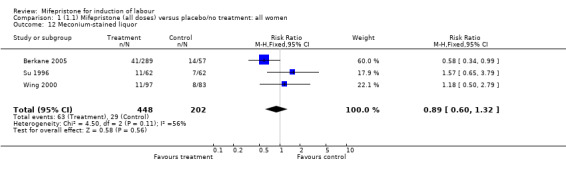

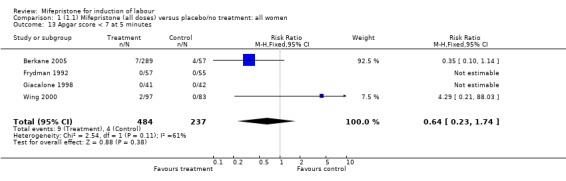

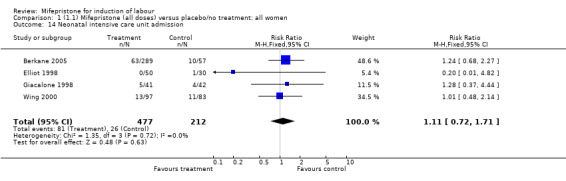

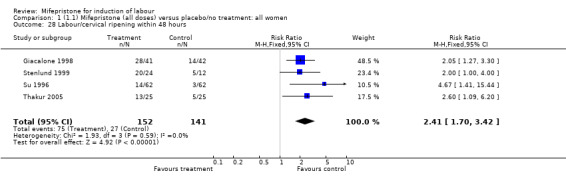

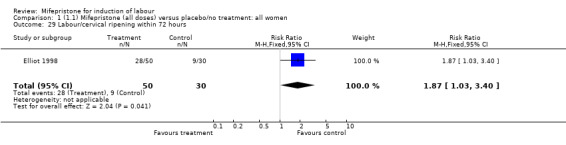

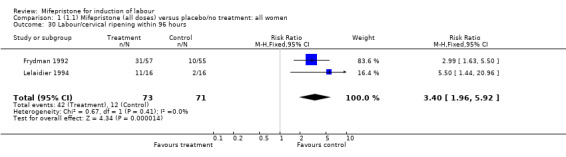

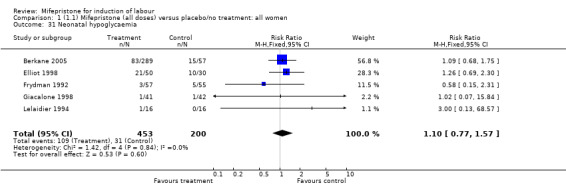

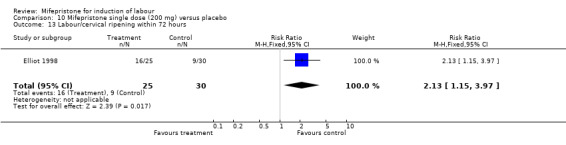

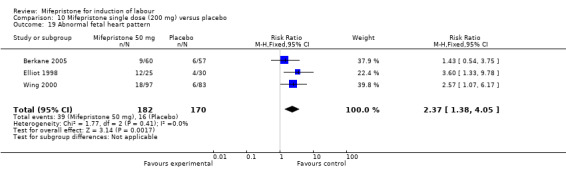

Ten trials (1108 women) are included. Compared to placebo, mifepristone treated women were more likely to be in labour or to have a favourable cervix at 48 hours (risk ratio (RR) 2.41, 95% confidence intervals (CI) 1.70 to 3.42) and this effect persisted at 96 hours (RR 3.40, 95% CI 1.96 to 5.92). They were less likely to need augmentation with oxytocin (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.97). Mifepristone treated women were less likely to undergo caesarean section (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.60 to 0.92) but more likely to have an instrumental delivery (RR 1.43, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.96). Women receiving mifepristone were less likely to undergo a caesarean section as a result of failure to induce labour (RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.80). There is insufficient evidence to support a particular dose but a single dose of 200 mg mifepristone appears to be the lowest effective dose for cervical ripening (increased likelihood of cervical ripening at 72 hours (RR 2.13, 95% CI 1.15 to 3.97). Abnormal fetal heart rate patterns were more common after mifepristone treatment (RR 1.85, 95% CI 1.17 to 2.93), but there was no evidence of differences in other neonatal outcomes. There is insufficient information on the occurrence of uterine rupture/dehiscence in the reviewed studies.

Authors' conclusions

There is insufficient information available from clinical trials to support the use of mifepristone to induce labour. However, the studies suggest that mifepristone is better than placebo in reducing the likelihood of caesarean sections being performed for failed induction of labour; therefore, this may justify future trials comparing mifepristone with the routine cervical ripening agents currently in use. There is little information on effects on the baby.

Plain language summary

Mifepristone for induction of labour

Not enough evidence on the effects of mifepristone (RU 486) to induce labour.

The female sex hormone, progesterone stops the uterus contracting during pregnancy. Drugs such as mifepristone have been used to stop the action of this hormone, either to induce labour or to allow the pregnancy to be terminated. The review of ten trials (1108 women) found there is not enough evidence to support the use of mifepristone to induce labour. There is little information about adverse effects for the mother or baby. However, there is evidence that mifepristone can reduce the need for a caesarean so further research is needed.

Background

The female steroid sex hormone, progesterone, inhibits contractility of the uterus. A new class of pharmacological agents (antiprogestins) has been developed to antagonise the action of progesterone. Of these, mifepristone (also called RU 486) is best known. Mifepristone is a 19 nor‐steroid which has greater affinity for progesterone receptors than does progesterone itself. It thus blocks the action of progesterone at the cellular level. The pharmacokinetics of mifepristone are characterised by rapid absorption and a long half‐life of 25 to 30 hours (Heikinheimo 1997). Key metabolites also have high affinity to progesterone receptors.

Mifepristone now has an established role in termination of pregnancy (in combination with prostaglandins) during the early first, and the second trimesters (Van Look 1995). Mifepristone is also being investigated as a possible contraceptive agent (both for planned and emergency contraception) (Hapangama 2003).

Mifepristone has potential also as a method of inducing labour in late pregnancy through its actions in antagonising progesterone, thus increasing uterine contractility and by increasing the sensitivity of the uterus to the actions of prostaglandins. Mifepristone has been shown to induce labour in rats (Fang 1997), through opposition to progesterone‐induced suppression of oxytocin receptors, and enhanced synthesis of prostaglandins. Mifepristone has also been shown to induce preterm birth in mice, associated with a rise in prostaglandins and cyokines (Dudley 1996). A randomised‐controlled trial in beef heifers found a mean time to delivery of 43 hours after mifepristone administration, compared to 182 hours in placebo treated controls (Dlamini 1995); interestingly, retained placenta was a problem in the experimental group. In a primate model (the macaque), mifepristone administration induced prostaglandin F2alpha production by decidua, but not prostaglandin E2 production by amnion (Haluska 1994).

In women, mifepristone combined with subsequent prostaglandins is also being commonly used for labour induction after fetal death in later pregnancy (Fairley 2005). The data from women undergoing termination of early pregnancy have shown that mifepristone is more effective in nulliparous women (Bartley 2000).

There is, thus, reason to anticipate from animal studies and termination studies in human pregnancies that mifepristone might prove an effective method of inducing labour in late human pregnancy.

This review is one of a series of reviews of methods of labour induction using a standardised protocol. For more detailed information on the rationale for this methodological approach, please refer to the published generic protocol (Hofmeyr 2003b).

Objectives

To determine, from the best available evidence, the effectiveness and safety of mifepristone for third trimester cervical ripening and induction of labour.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Clinical trials comparing mifepristone for cervical ripening or labour induction, with placebo/no treatment or other methods listed above it on a predefined list of methods of labour induction (see 'Methods'); the trials included some form of random allocation to either group; and they reported one or more of the prestated outcomes.

Types of participants

Pregnant women due for third trimester induction of labour, carrying a viable fetus.

Predefined subgroup analyses are (see list below): previous caesarean section or not; nulliparity or multiparity; membranes intact or ruptured, and cervix unfavourable, favourable or undefined. Only those outcomes with data will appear in the analysis tables.

Types of interventions

Mifepristone compared with placebo/no treatment or any other method above it on the predefined list of methods of labour induction.

Types of outcome measures

Clinically relevant outcomes for trials of methods of cervical ripening/labour induction have been prespecified by two authors of labour induction reviews (Justus Hofmeyr and Zarko Alfirevic). Differences were settled by discussion.

Five primary outcomes were chosen as being most representative of the clinically important measures of effectiveness and complications. Subgroup analyses were limited to the primary outcomes: (1) vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours; (2) uterine hyperstimulation with fetal heart rate (FHR) changes; (3) caesarean section; (4) serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death (e.g. seizures, birth asphyxia defined by trialists, neonatal encephalopathy, disability in childhood); (5) serious maternal morbidity or death (e.g. uterine rupture, admission to intensive care unit, septicemia).

Perinatal and maternal morbidity and mortality are composite outcomes. This is not an ideal solution because some components are clearly less severe than others. It is possible for one intervention to cause more deaths but less severe morbidity. However, in the context of labour induction at term this is unlikely. All these events will be rare, and a modest change in their incidence will be easier to detect if composite outcomes are presented. The incidence of individual components will be explored as secondary outcomes (see below).

Secondary outcomes relate to measures of effectiveness, complications and satisfaction:

Measures of effectiveness: (6) cervix unfavourable/unchanged after 12 to 24 hours; (7) oxytocin augmentation.

Complications: (8) uterine hyperstimulation without fetal heart rate changes; (9) uterine dehiscence/rupture; (10) epidural analgesia; (11) instrumental vaginal delivery; (12) meconium‐stained liquor; (13) Apgar score less than seven at five minutes; (14) neonatal intensive care unit admission; (15) neonatal encephalopathy; (16) perinatal death; (17) disability in childhood; (18) maternal side effects; (19) nausea; (20) vomiting; (21) diarrhoea; (22) other; (23) postpartum haemorrhage (as defined by the trial authors); (24) serious maternal complications (e.g. intensive care unit admission, septicaemia but excluding uterine rupture); (25) maternal death.

Measures of satisfaction: (26) woman not satisfied; (27) caregiver not satisfied.

While all the above outcomes were sought, only those with data appear in the analysis tables.

The terminology of uterine hyperstimulation is problematic (Curtis 1987). In these reviews we will use the term 'uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes' to include uterine tachysystole (> 5 contractions per 10 minutes for at least 20 minutes) and uterine hypersystole/hypertonus (a contraction lasting at least two minutes) and 'uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes' to denote uterine hyperstimulation syndrome (tachysystole or hypersystole with fetal heart rate changes such as persistent decelerations, tachycardia or decreased short‐term variability).

Outcomes were included in the analysis if: reasonable measures were taken to minimise observer bias, and data were available for analysis according to original allocation.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (May 2009).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL and MEDLINE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

The original search was performed simultaneously for all reviews of methods of inducing labour, as outlined in the generic protocol for these reviews (Hofmeyr 2003b).

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of trial reports and reviews by hand.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

A strategy was developed to deal with the large volume and complexity of trial data relating to labour induction. Many methods have been studied, in many different subgroups with particular characteristics such as nulliparous women, or those with ruptured membranes. Most trials are intervention‐driven, comparing two or more methods in various categories of women. Clinicians and parents need the data arranged by category of woman, to be able to choose which method is best for a particular clinical scenario. To extract these data from several hundred trial reports in a single step would be very difficult. We therefore developed a two‐stage method of data extraction. The initial data extraction was carried out in a series of reviews arranged by methods of induction of labour, following a standardised methodology. For the methods used when assessing the trials identified in the previous version of this review, seeAppendix 1.

To avoid duplication of data in the primary reviews, the labour induction methods have been listed in a specific order, from one to 27. Each primary review includes comparisons between one of the methods (from two to 27) with only those methods above it on the list. Thus, this review of mifepristone will include only comparisons with interventions 1 to 14 (placebo ‐ oral prostaglandins). Methods identified in the future will be added to the end of the list. The current list is as follows:

(1) placebo/no treatment; (2) vaginal prostaglandins (Kelly 2003); (3) intracervical prostaglandins (Boulvain 2008); (4) intravenous oxytocin (Kelly 2001b); (5) amniotomy (Bricker 2000); (6) intravenous oxytocin with amniotomy (Howarth 2001); (7) vaginal misoprostol (Hofmeyr 2003a); (8) oral misoprostol (Alfirevic 2006); (9) mechanical methods including extra‐amniotic Foley catheter (Boulvain 2001); (10) membrane sweeping (Boulvain 2005); (11) extra‐amniotic prostaglandins (Hutton 2001); (12) intravenous prostaglandins (Luckas 2000); (13) oral prostaglandins (French 2001); (14) mifepristone (Neilson 2000); (15) estrogens (Thomas 2001); (16) corticosteroids (Kavanagh 2006b); (17) relaxin (Kelly 2001c); (18) hyaluronidase (Kavanagh 2006a); (19) castor oil, bath, and/or enema (Kelly 2001a); (20) acupuncture (Smith 2004); (21) breast stimulation (Kavanagh 2005); (22) sexual intercourse (Kavanagh 2001); (23) homoeopathic methods (Smith 2003); (24) nitric oxide (Kelly 2008a); (25) buccal or sublingual misoprostol (Muzonzini 2004); (26) hypnosis; (27) other methods for induction of labour. The reviews are analysed by the following subgroups: (1) previous caesarean section or not; (2) nulliparity or multiparity; (3) membranes intact or ruptured; (4) cervix favourable, unfavourable or undefined.

For this update, we used the following methods when assessing the trials identified by the updated search:

Selection of studies

The review authors independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies we identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, both review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we would have consulted a third person. Data were entered into Review Manager software (RevMan 2008) and checked for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Both review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). Any disagreement was resolved by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

adequate (any truly random process e.g. random number table; computer random number generator),

inadequate (any non random process e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number) or

unclear.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

For each included study we described the method used to conceal the allocation sequence in sufficient detail and determined whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

inadequate (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear.

(3) Blinding (checking for possible performance bias)

For each included study we described the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. Studies were judged at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding could not have affected the results. Blinding was assessed separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate, inadequate or unclear for participants;

adequate, inadequate or unclear for personnel;

adequate, inadequate or unclear for outcome assessors.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or were supplied by the trial authors, we re‐included missing data in the analyses which we undertook. We assessed methods as:

adequate;

inadequate:

unclear.

(5) Selective reporting bias

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate (where it was clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

inadequate (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear.

(6) Other sources of bias

We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

yes;

no;

unclear.

(7) Overall risk of bias [See table 8.5c in the Handbook]

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2008). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it was likely to impact on the findings.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

For continuous data, we used the mean difference if outcomes are measured in the same way between trials. We used the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measure the same outcome, but used different methods.

Dealing with missing data

The included studies did not have high levels of missing data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We used the I² statistic to measure heterogeneity among the trials in each analysis. If we identified substantial heterogeneity we explored it by pre‐specified subgroup analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

Where we suspected reporting bias (see selective reporting bias above), we attempted to contact study authors asking them to provide missing outcome data. Where this was not possible, and the missing data were thought to introduce serious bias, the impact of including such studies in the overall assessment of results was explored by a sensitivity analysis.

Data synthesis

We carried statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2008).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We carried out the following subgroup analyses:

All primiparous women

All women with unfavourable cervix

Women with pre‐labour rupture of membranes beyond 36 weeks of gestation with unfavourable cervix

Women who had previous caesarean section with unfavourable cervix

Women who had dose of 50 mg mifepristone

Women who had dose of 100 mg mifepristone

Women who had dose of 200 mg mifepristone

Women who had dose of 400 mg mifepristone

Women who had dose of 600 mg mifepristone

The following outcomes were used in subgroup analysis: caesarean sections, uterine dehiscence or rupture, maternal side effects, Apgar scores less than seven at five minutes, admission to the neonatal intensive care unit, and uterine hyperstimulation. Non‐overlapping confidence intervals indicate a statistically significant difference in treatment effect between the subgroups.

Sensitivity analysis

We did not feel it was necessary to carry out a sensitivity analysis.

Results

Description of studies

Details of the studies are listed in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table. Doses of mifepristone varied in different trials. Most studies compared mifepristone with placebo. We have identified only one trial that compared mifepristone with an active induction agent ‐ oxytocin.

Risk of bias in included studies

The methodological quality of the trials appeared high.

Effects of interventions

Ten trials, that recruited 1108 women, are included. Eight trials compared mifepristone with placebo, one compared mifepristone with no treatment, and another compared mifepristone with oxytocin.

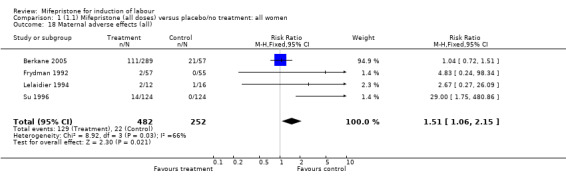

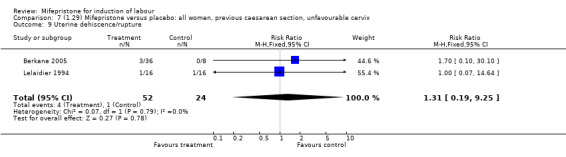

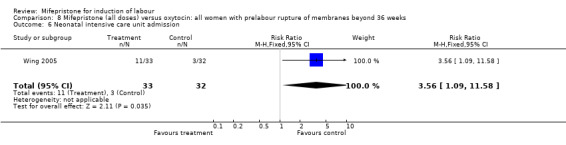

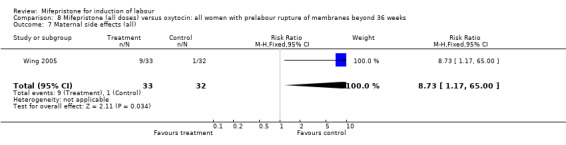

There is evidence, from the trials, that mifepristone does induce both ripening of the cervix, and labour. Compared to placebo, mifepristone treated women were more likely to be in labour or to have a favourable cervix at 48 hours (risk ratio (RR) 2.41, 95% confidence intervals (CI) 1.70 to 3.42) and this effect was persisted at 72 (RR 1.87, 95% CI 1.03 to 3.40) and 96 hours (RR 3.40, 95% CI 1.96 to 5.92). They were less likely to need augmentation with oxytocin (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.97). There are data on caesarean section rates from all ten included trials. Mifepristone treated women were less likely to undergo caesarean section (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.60 to 0.92) but more likely to have an instrumental delivery (RR 1.43, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.96). It was of further interest that women receiving mifepristone were less likely to undergo a caesarean section as a result of failure to induce labour (RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.80). There is insufficient evidence to support a particular dose but a single dose of 200 mg mifepristone appears to be the lowest effective dose for cervical ripening (increased likelihood of cervical ripening at 72 hours (RR 2.13, 95% CI 1.15 to 3.97). Not all studies reported on fetal outcome, although abnormal fetal heart rate patterns were more common after mifepristone treatment (RR 1.85, 95% CI 1.17 to 2.93), although there was no evidence of differences in admission to a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) (RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.71) or of neonates having Apgar scores less than seven at five minutes (RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.24 to1.74). There was no evidence that neonatal hypoglycaemia might be more common after exposure to mifepristone (it antagonises the action of glucocorticoids as well as progesterone), (RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.57). The incidence of all reported adverse events was higher in women receiving mifepristone than placebo (RR 1.51, 95% CI 1.06 to 2.15) however, these seem to be mainly minor gastro‐intestinal upsets (nausea, diarrhoea and vomiting). A further study (Wing 2003) has compared the use of mifepristone to oxytocin in inducing labour in pregnancies beyond 36 weeks with prelabour rupture of membranes and women after mifepristone were less likely to have a vaginal delivery within 24 hours (RR 0.30, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.88) and their babies had an increased likelihood of neonatal adverse outcomes with more NICU admissions (RR 4.83, 95% CI 1.20 to 19.44), and abnormal fetal heart rate patterns (RR 5.63, 95% CI 1.11 to 28.52). There is insufficient information on the occurrence of uterine rupture/dehiscence particularly when used in women who had previously undergone a caesarean section in the reviewed studies.

Discussion

See authors' conclusions.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is insufficient information available from clinical trials to support the use of mifepristone to induce labour.

Implications for research.

However, available data do show that mifepristone is better than placebo at ripening the cervix or inducing labour. There is evidence of a possible reduction in the incidence of caesarean section following mifepristone treatment (compared to placebo) that would justify further trials. There are no trial data that we have found (except for the one trial comparing mifepristone to oxytocin which did not show an advantage of mifepristone over oxytocin) that compare mifepristone with other methods of suitable cervical ripening/labour induction, e.g. prostaglandins. Any such comparison should assess formally the views of women recruited. If, for example, mifepristone were to produce less rapid onset of labour, but a process more akin to natural labour, then that might generate either frustration or satisfaction.

Theoretically, mifepristone has appeal as a method of inducing labour in women with previous caesarean section (if that is deemed important) as it does not involve administering exogenous oxytocic drugs that have the potential to over‐stimulate, and even rupture, the uterus. More work is this area may be justified. A single‐dose therapy of 200 mg is likely to be the preferred dose for such trial.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 7 May 2009 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | New author prepared this update. |

| 30 September 2008 | New search has been performed | Search updated. Six new trials identified. Five have been included (Berkane 2005; Lelaidier 1994; Thakur 2005;Wing 2000; Wing 2005) and one excluded (Jiang 1997). Another report of Frydman 1992 has been added. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2000 Review first published: Issue 4, 2000

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 4 November 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

As part of the pre‐publication editorial process, this review has been commented on by one peer (editor) and the Group's Statistical Adviser.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Methods used to assess trials included in the previous version of this review

Information is extracted regarding the methodological quality of trials on a number of levels. This process is completed without consideration of trial results. Assessment of selection bias examines the process involved in the generation of the random sequence and the method of allocation concealment separately. These are then judged as adequate or inadequate using the criteria described in Table 11 for the purpose of the reviews.

1. Methodological quality of trials.

| Methodological item | Adequate | Inadequate |

| Generation of random sequence | Computer‐generated sequence, random number tables, lot drawing, coin tossing, shuffling cards, throwing dice. | Case number, date of birth, date of admission, alternation. |

| Concealment of allocation | Central randomisation, coded drug boxes, sequentially sealed opaque envelopes. | Open allocation sequence, any procedure based on inadequate generation. |

Performance bias is examined with regards to whom was blinded in the trials, i.e. patient, caregiver, outcome assessor or analyst. In many trials the caregiver, assessor and analyst were the same party. Details of the feasibility and appropriateness of blinding at all levels is sought.

Individual outcome data are included in the analysis if they meet the prestated criteria in 'Types of outcome measures'. Included trial data are processed as described in the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook (Clarke 1999). Data extracted from the trials are analysed on an intention‐to‐treat basis (when this was not done in the original report, re‐analysis is performed if possible). Where data are missing, clarification is sought from the original authors. If the attrition was such that it might significantly affect the results, these data are excluded from the analysis. This decision rests with the authors of primary reviews and is clearly documented. Once missing data become available, they will be included in the analyses.

Data are extracted from all eligible trials to examine how issues of quality influence effect size in a sensitivity analysis. In trials where reporting is poor, methodological issues are reported as unclear or clarification sought.

Due to the large number of trials, double data extraction is not feasible and agreement between the three data extractors is therefore assessed on a random sample of trials.

Once the data have been extracted, they are distributed to individual authors for entry onto the Review Manager computer software (RevMan 2008), checked for accuracy, and analysed as above using the RevMan software. For dichotomous data, risk ratio and 95% confidence intervals are calculated, and in the absence of heterogeneity, results are pooled using a fixed‐effect model.

The predefined criteria for sensitivity analysis include all aspects of quality assessment as mentioned above, including aspects of selection, performance and attrition bias. Primary analysis is limited to the prespecified outcomes and subgroup analyses. In the event of differences in unspecified outcomes or subgroups being found, these are analysed post hoc, but clearly identified as such to avoid drawing unjustified conclusions.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. (1.1) Mifepristone (all doses) versus placebo/no treatment: all women.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

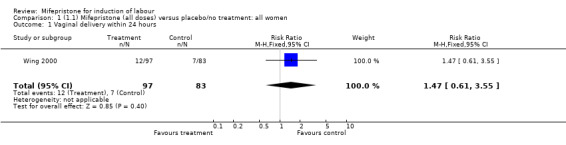

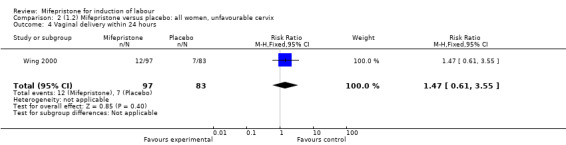

| 1 Vaginal delivery within 24 hours | 1 | 180 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.47 [0.61, 3.55] |

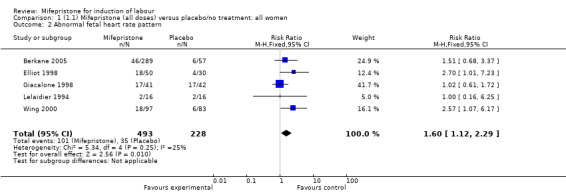

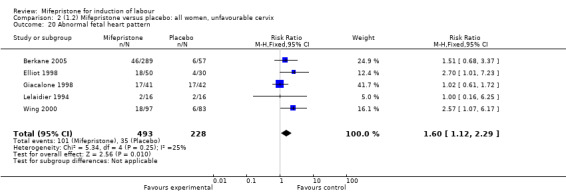

| 2 Abnormal fetal heart rate pattern | 5 | 721 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.60 [1.12, 2.29] |

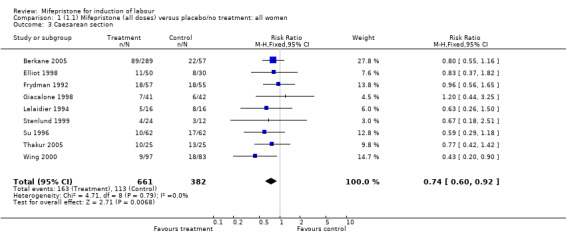

| 3 Caesarean section | 9 | 1043 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.74 [0.60, 0.92] |

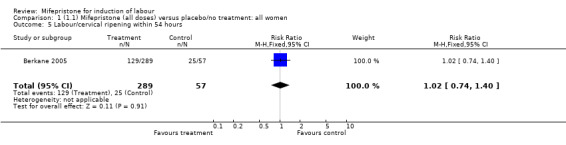

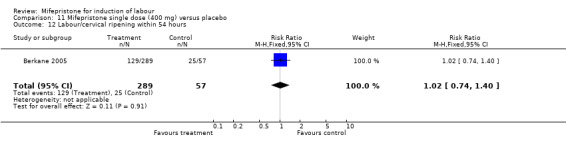

| 5 Labour/cervical ripening within 54 hours | 1 | 346 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.74, 1.40] |

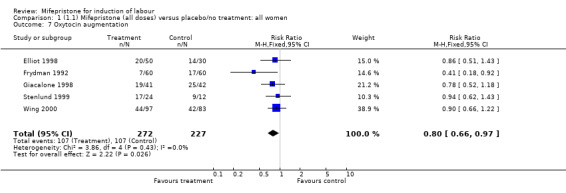

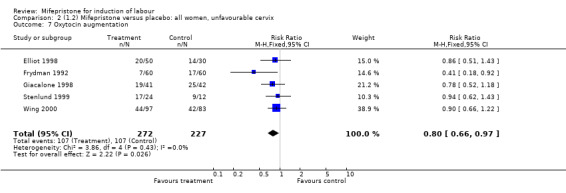

| 7 Oxytocin augmentation | 5 | 499 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.66, 0.97] |

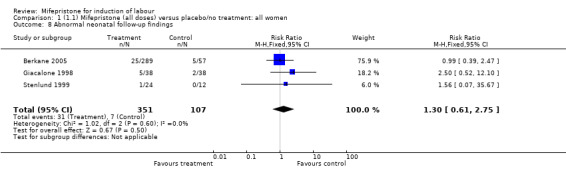

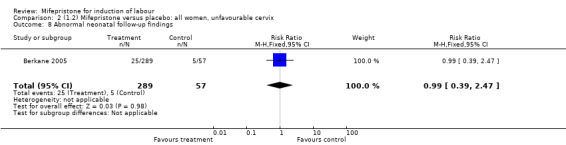

| 8 Abnormal neonatal follow‐up findings | 3 | 458 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.30 [0.61, 2.75] |

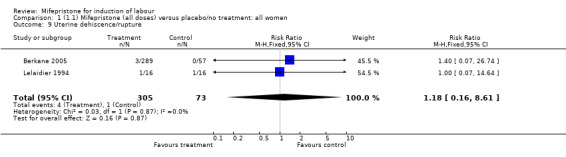

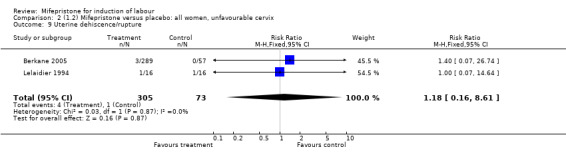

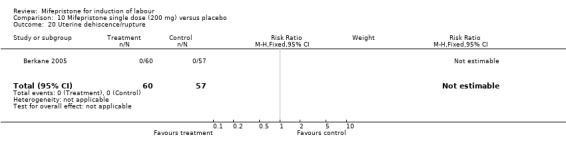

| 9 Uterine dehiscence/rupture | 2 | 378 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.18 [0.16, 8.61] |

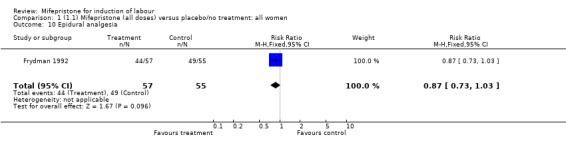

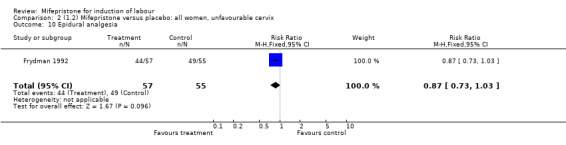

| 10 Epidural analgesia | 1 | 112 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.73, 1.03] |

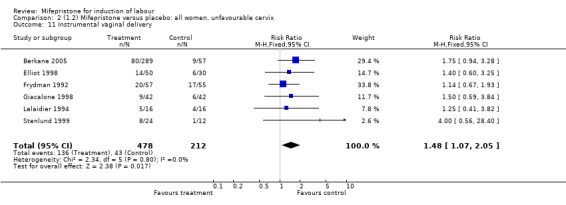

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 7 | 814 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.43 [1.04, 1.96] |

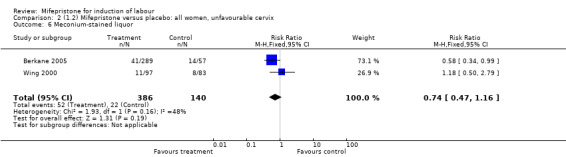

| 12 Meconium‐stained liquor | 3 | 650 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.60, 1.32] |

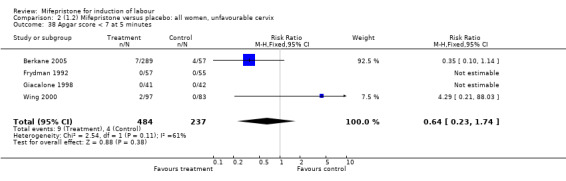

| 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 4 | 721 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.23, 1.74] |

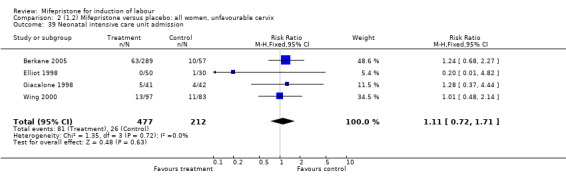

| 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 4 | 689 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.72, 1.71] |

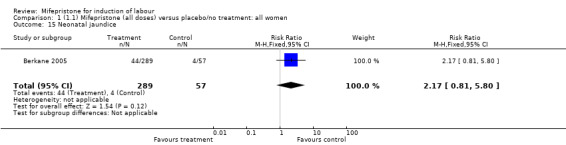

| 15 Neonatal jaundice | 1 | 346 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.17 [0.81, 5.80] |

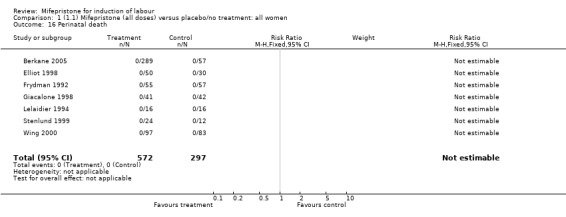

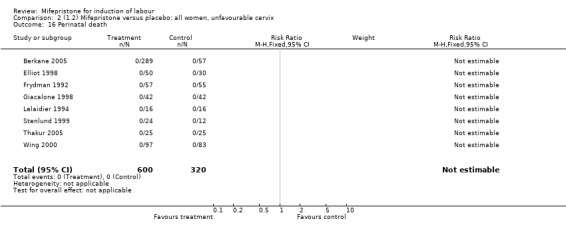

| 16 Perinatal death | 7 | 869 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

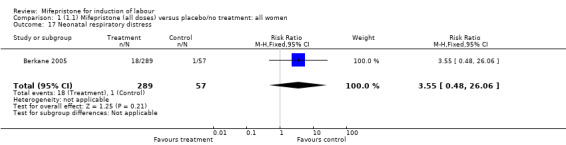

| 17 Neonatal respiratory distress | 1 | 346 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.55 [0.48, 26.06] |

| 18 Maternal adverse effects (all) | 4 | 734 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.51 [1.06, 2.15] |

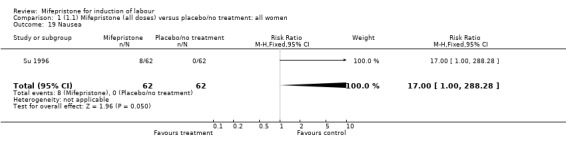

| 19 Nausea | 1 | 124 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 17.0 [1.00, 288.28] |

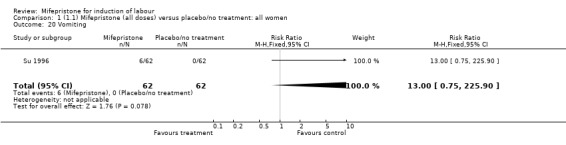

| 20 Vomiting | 1 | 124 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 13.0 [0.75, 225.90] |

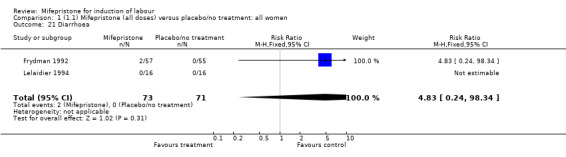

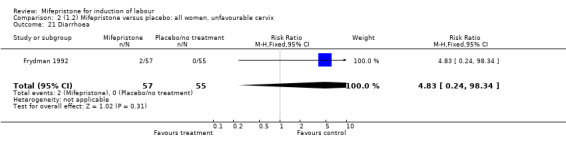

| 21 Diarrhoea | 2 | 144 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.83 [0.24, 98.34] |

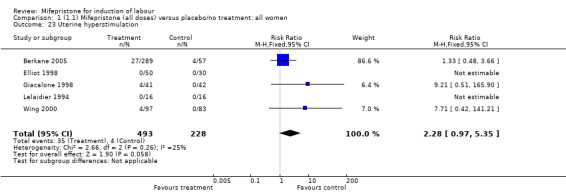

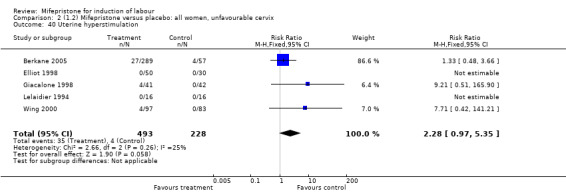

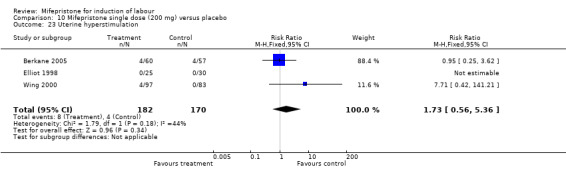

| 23 Uterine hyperstimulation | 5 | 721 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.28 [0.97, 5.35] |

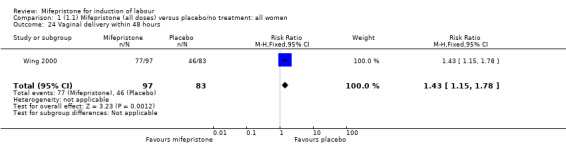

| 24 Vaginal delivery within 48 hours | 1 | 180 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.43 [1.15, 1.78] |

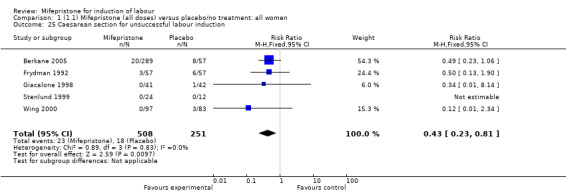

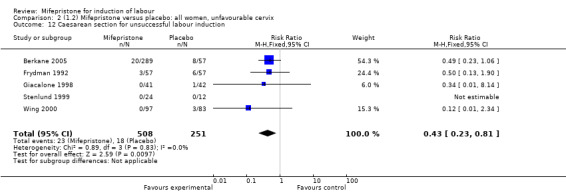

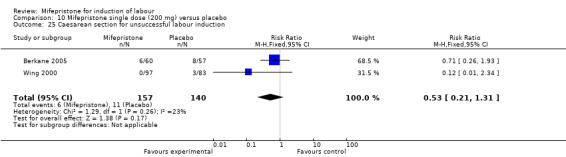

| 25 Caesarean section for unsuccessful labour induction | 5 | 759 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.43 [0.23, 0.81] |

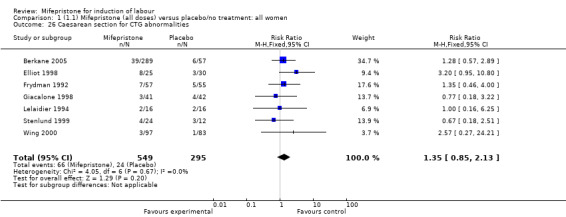

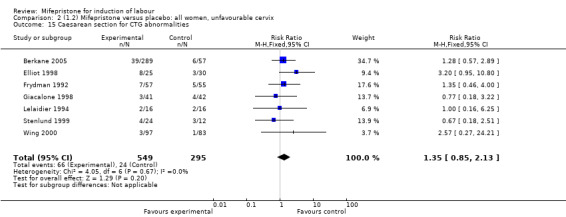

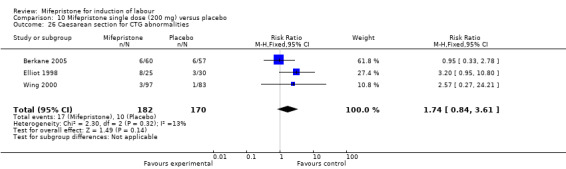

| 26 Caesarean section for CTG abnormalities | 7 | 844 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.35 [0.85, 2.13] |

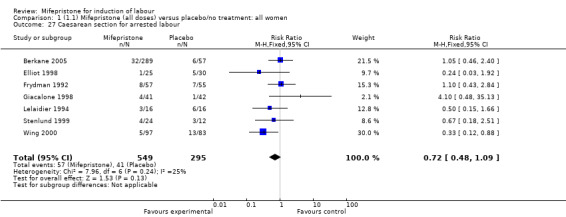

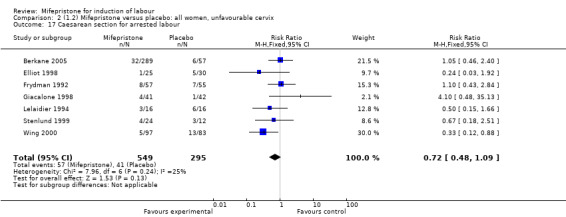

| 27 Caesarean section for arrested labour | 7 | 844 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.48, 1.09] |

| 28 Labour/cervical ripening within 48 hours | 4 | 293 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.41 [1.70, 3.42] |

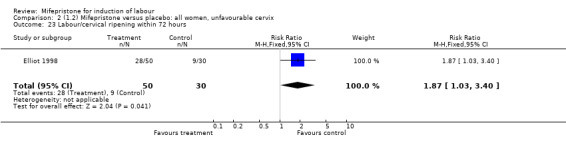

| 29 Labour/cervical ripening within 72 hours | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.87 [1.03, 3.40] |

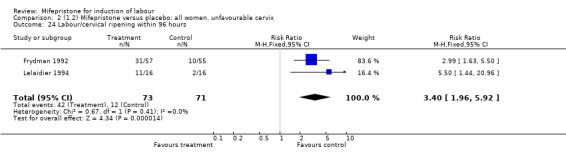

| 30 Labour/cervical ripening within 96 hours | 2 | 144 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.40 [1.96, 5.92] |

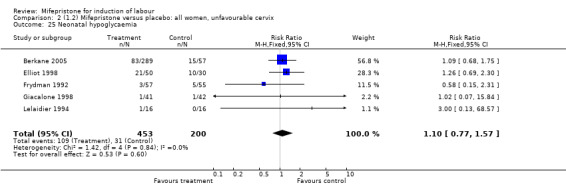

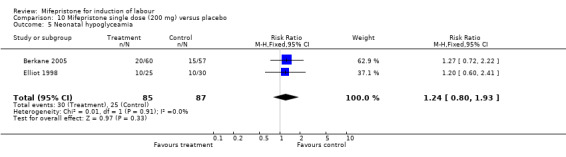

| 31 Neonatal hypoglycaemia | 5 | 653 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.77, 1.57] |

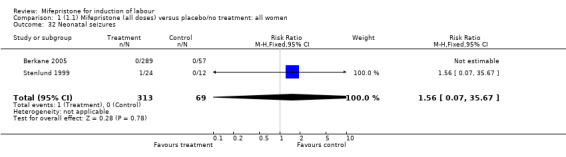

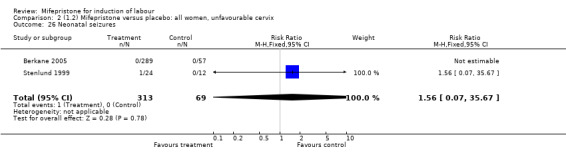

| 32 Neonatal seizures | 2 | 382 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.56 [0.07, 35.67] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1) Mifepristone (all doses) versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 1 Vaginal delivery within 24 hours.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1) Mifepristone (all doses) versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 2 Abnormal fetal heart rate pattern.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1) Mifepristone (all doses) versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1) Mifepristone (all doses) versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 5 Labour/cervical ripening within 54 hours.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1) Mifepristone (all doses) versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 7 Oxytocin augmentation.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1) Mifepristone (all doses) versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 8 Abnormal neonatal follow‐up findings.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1) Mifepristone (all doses) versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 9 Uterine dehiscence/rupture.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1) Mifepristone (all doses) versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 10 Epidural analgesia.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1) Mifepristone (all doses) versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1) Mifepristone (all doses) versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 12 Meconium‐stained liquor.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1) Mifepristone (all doses) versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1) Mifepristone (all doses) versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1) Mifepristone (all doses) versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 15 Neonatal jaundice.

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1) Mifepristone (all doses) versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 16 Perinatal death.

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1) Mifepristone (all doses) versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 17 Neonatal respiratory distress.

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1) Mifepristone (all doses) versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 18 Maternal adverse effects (all).

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1) Mifepristone (all doses) versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 19 Nausea.

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1) Mifepristone (all doses) versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 20 Vomiting.

1.21. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1) Mifepristone (all doses) versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 21 Diarrhoea.

1.23. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1) Mifepristone (all doses) versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 23 Uterine hyperstimulation.

1.24. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1) Mifepristone (all doses) versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 24 Vaginal delivery within 48 hours.

1.25. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1) Mifepristone (all doses) versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 25 Caesarean section for unsuccessful labour induction.

1.26. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1) Mifepristone (all doses) versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 26 Caesarean section for CTG abnormalities.

1.27. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1) Mifepristone (all doses) versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 27 Caesarean section for arrested labour.

1.28. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1) Mifepristone (all doses) versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 28 Labour/cervical ripening within 48 hours.

1.29. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1) Mifepristone (all doses) versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 29 Labour/cervical ripening within 72 hours.

1.30. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1) Mifepristone (all doses) versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 30 Labour/cervical ripening within 96 hours.

1.31. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1) Mifepristone (all doses) versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 31 Neonatal hypoglycaemia.

1.32. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1) Mifepristone (all doses) versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 32 Neonatal seizures.

Comparison 2. (1.2) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, unfavourable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

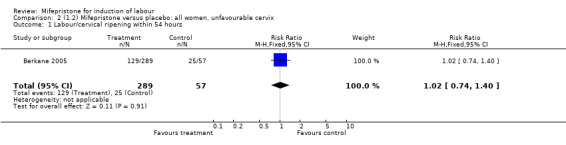

| 1 Labour/cervical ripening within 54 hours | 1 | 346 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.74, 1.40] |

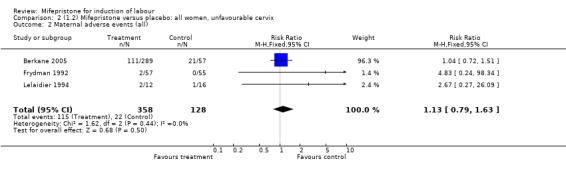

| 2 Maternal adverse events (all) | 3 | 486 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.13 [0.79, 1.63] |

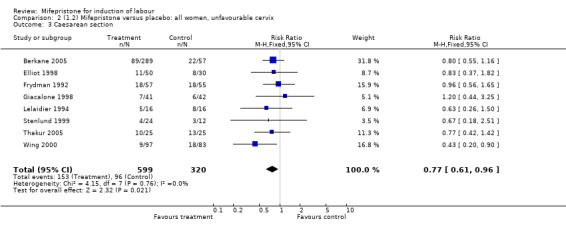

| 3 Caesarean section | 8 | 919 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.61, 0.96] |

| 4 Vaginal delivery within 24 hours | 1 | 180 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.47 [0.61, 3.55] |

| 6 Meconium‐stained liquor | 2 | 526 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.74 [0.47, 1.16] |

| 7 Oxytocin augmentation | 5 | 499 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.66, 0.97] |

| 8 Abnormal neonatal follow‐up findings | 1 | 346 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.39, 2.47] |

| 9 Uterine dehiscence/rupture | 2 | 378 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.18 [0.16, 8.61] |

| 10 Epidural analgesia | 1 | 112 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.73, 1.03] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 6 | 690 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.48 [1.07, 2.05] |

| 12 Caesarean section for unsuccessful labour induction | 5 | 759 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.43 [0.23, 0.81] |

| 15 Caesarean section for CTG abnormalities | 7 | 844 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.35 [0.85, 2.13] |

| 16 Perinatal death | 8 | 920 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 17 Caesarean section for arrested labour | 7 | 844 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.48, 1.09] |

| 20 Abnormal fetal heart pattern | 5 | 721 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.60 [1.12, 2.29] |

| 21 Diarrhoea | 1 | 112 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.83 [0.24, 98.34] |

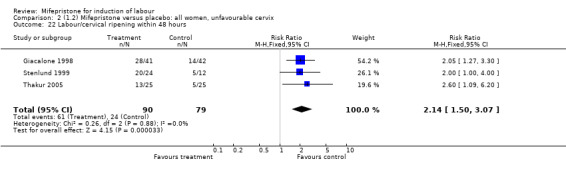

| 22 Labour/cervical ripening within 48 hours | 3 | 169 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.14 [1.50, 3.07] |

| 23 Labour/cervical ripening within 72 hours | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.87 [1.03, 3.40] |

| 24 Labour/cervical ripening within 96 hours | 2 | 144 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.40 [1.96, 5.92] |

| 25 Neonatal hypoglycaemia | 5 | 653 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.77, 1.57] |

| 26 Neonatal seizures | 2 | 382 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.56 [0.07, 35.67] |

| 38 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 4 | 721 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.23, 1.74] |

| 39 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 4 | 689 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.72, 1.71] |

| 40 Uterine hyperstimulation | 5 | 721 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.28 [0.97, 5.35] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 1 Labour/cervical ripening within 54 hours.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 2 Maternal adverse events (all).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 4 Vaginal delivery within 24 hours.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 6 Meconium‐stained liquor.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 7 Oxytocin augmentation.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 8 Abnormal neonatal follow‐up findings.

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 9 Uterine dehiscence/rupture.

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 10 Epidural analgesia.

2.11. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

2.12. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 12 Caesarean section for unsuccessful labour induction.

2.15. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 15 Caesarean section for CTG abnormalities.

2.16. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 16 Perinatal death.

2.17. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 17 Caesarean section for arrested labour.

2.20. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 20 Abnormal fetal heart pattern.

2.21. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 21 Diarrhoea.

2.22. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 22 Labour/cervical ripening within 48 hours.

2.23. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 23 Labour/cervical ripening within 72 hours.

2.24. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 24 Labour/cervical ripening within 96 hours.

2.25. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 25 Neonatal hypoglycaemia.

2.26. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 26 Neonatal seizures.

2.38. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 38 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

2.39. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 39 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

2.40. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 40 Uterine hyperstimulation.

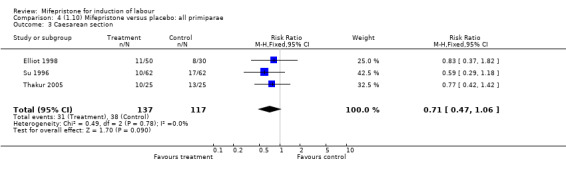

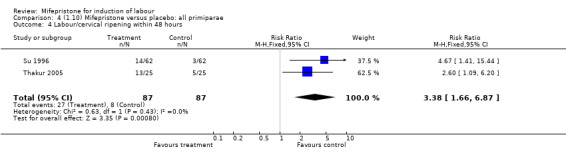

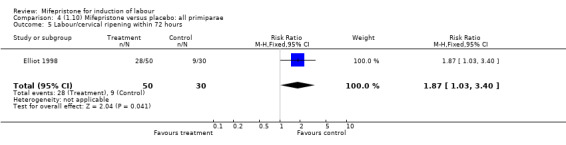

Comparison 4. (1.10) Mifepristone versus placebo: all primiparae.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Caesarean section | 3 | 254 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.47, 1.06] |

| 4 Labour/cervical ripening within 48 hours | 2 | 174 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.38 [1.66, 6.87] |

| 5 Labour/cervical ripening within 72 hours | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.87 [1.03, 3.40] |

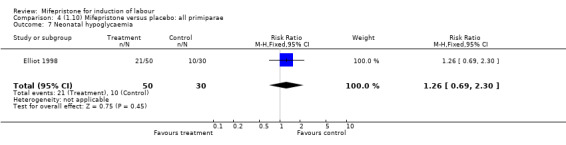

| 7 Neonatal hypoglycaemia | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.26 [0.69, 2.30] |

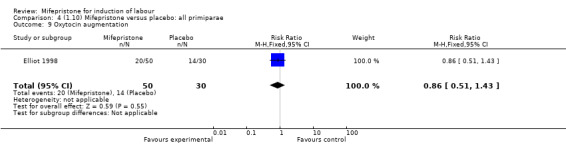

| 9 Oxytocin augmentation | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.51, 1.43] |

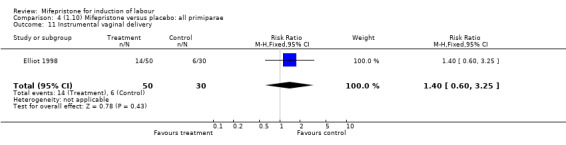

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.4 [0.60, 3.25] |

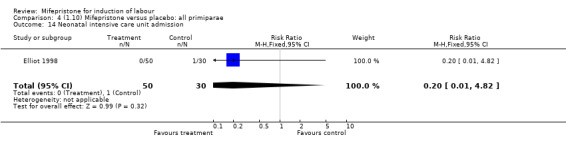

| 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.20 [0.01, 4.82] |

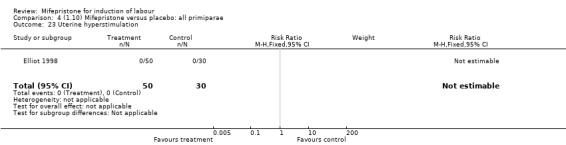

| 23 Uterine hyperstimulation | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

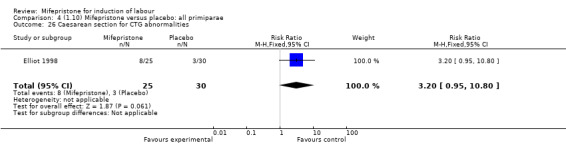

| 26 Caesarean section for CTG abnormalities | 1 | 55 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.2 [0.95, 10.80] |

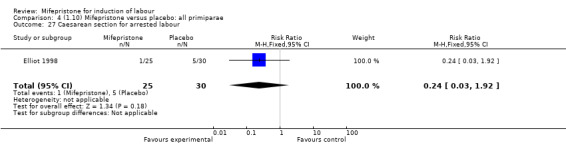

| 27 Caesarean section for arrested labour | 1 | 55 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.24 [0.03, 1.92] |

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 (1.10) Mifepristone versus placebo: all primiparae, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 (1.10) Mifepristone versus placebo: all primiparae, Outcome 4 Labour/cervical ripening within 48 hours.

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 (1.10) Mifepristone versus placebo: all primiparae, Outcome 5 Labour/cervical ripening within 72 hours.

4.7. Analysis.

Comparison 4 (1.10) Mifepristone versus placebo: all primiparae, Outcome 7 Neonatal hypoglycaemia.

4.9. Analysis.

Comparison 4 (1.10) Mifepristone versus placebo: all primiparae, Outcome 9 Oxytocin augmentation.

4.11. Analysis.

Comparison 4 (1.10) Mifepristone versus placebo: all primiparae, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

4.14. Analysis.

Comparison 4 (1.10) Mifepristone versus placebo: all primiparae, Outcome 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

4.23. Analysis.

Comparison 4 (1.10) Mifepristone versus placebo: all primiparae, Outcome 23 Uterine hyperstimulation.

4.26. Analysis.

Comparison 4 (1.10) Mifepristone versus placebo: all primiparae, Outcome 26 Caesarean section for CTG abnormalities.

4.27. Analysis.

Comparison 4 (1.10) Mifepristone versus placebo: all primiparae, Outcome 27 Caesarean section for arrested labour.

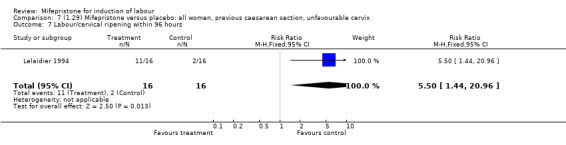

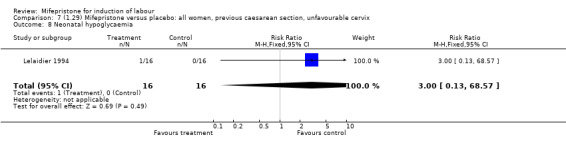

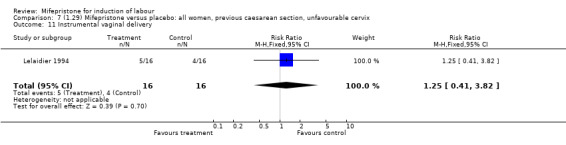

Comparison 7. (1.29) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, previous caesarean section, unfavourable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

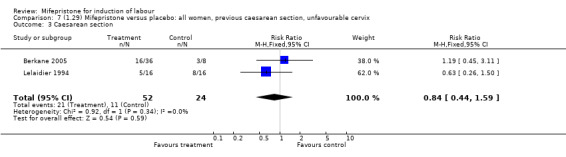

| 3 Caesarean section | 2 | 76 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.44, 1.59] |

| 7 Labour/cervical ripening within 96 hours | 1 | 32 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.5 [1.44, 20.96] |

| 8 Neonatal hypoglycaemia | 1 | 32 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 68.57] |

| 9 Uterine dehiscence/rupture | 2 | 76 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.31 [0.19, 9.25] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 32 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.41, 3.82] |

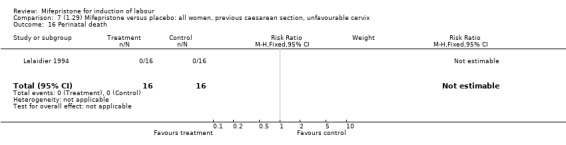

| 16 Perinatal death | 1 | 32 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

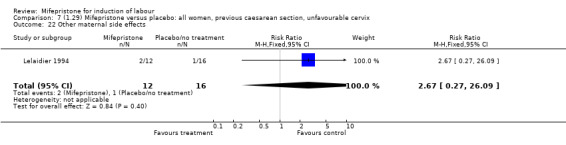

| 22 Other maternal side effects | 1 | 28 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.67 [0.27, 26.09] |

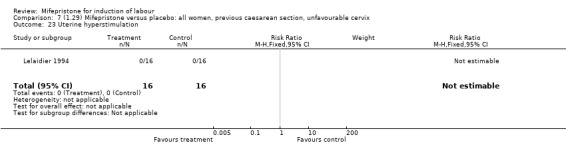

| 23 Uterine hyperstimulation | 1 | 32 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

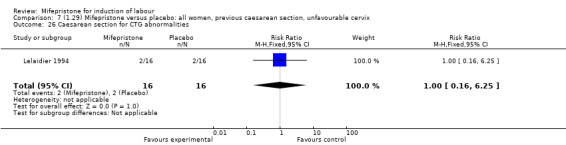

| 26 Caesarean section for CTG abnormalities | 1 | 32 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.16, 6.25] |

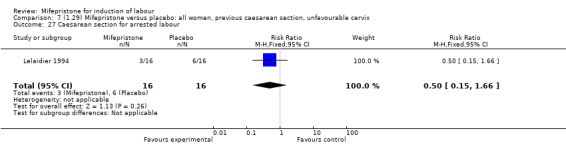

| 27 Caesarean section for arrested labour | 1 | 32 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.5 [0.15, 1.66] |

7.3. Analysis.

Comparison 7 (1.29) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, previous caesarean section, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

7.7. Analysis.

Comparison 7 (1.29) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, previous caesarean section, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 7 Labour/cervical ripening within 96 hours.

7.8. Analysis.

Comparison 7 (1.29) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, previous caesarean section, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 8 Neonatal hypoglycaemia.

7.9. Analysis.

Comparison 7 (1.29) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, previous caesarean section, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 9 Uterine dehiscence/rupture.

7.11. Analysis.

Comparison 7 (1.29) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, previous caesarean section, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

7.16. Analysis.

Comparison 7 (1.29) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, previous caesarean section, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 16 Perinatal death.

7.22. Analysis.

Comparison 7 (1.29) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, previous caesarean section, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 22 Other maternal side effects.

7.23. Analysis.

Comparison 7 (1.29) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, previous caesarean section, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 23 Uterine hyperstimulation.

7.26. Analysis.

Comparison 7 (1.29) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, previous caesarean section, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 26 Caesarean section for CTG abnormalities.

7.27. Analysis.

Comparison 7 (1.29) Mifepristone versus placebo: all women, previous caesarean section, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 27 Caesarean section for arrested labour.

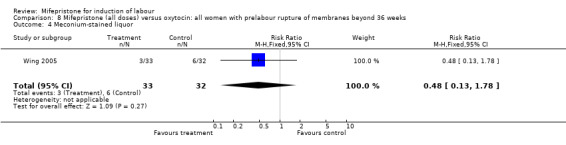

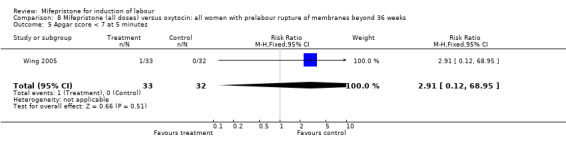

Comparison 8. Mifepristone (all doses) versus oxytocin: all women with prelabour rupture of membranes beyond 36 weeks.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

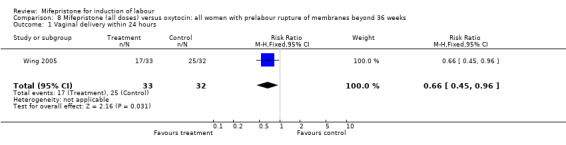

| 1 Vaginal delivery within 24 hours | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.45, 0.96] |

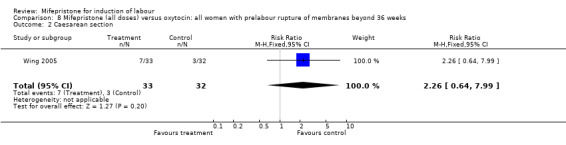

| 2 Caesarean section | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.26 [0.64, 7.99] |

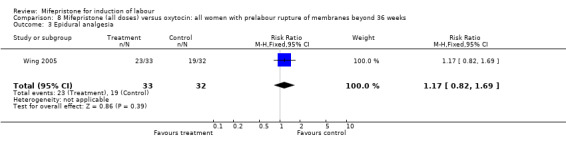

| 3 Epidural analgesia | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.17 [0.82, 1.69] |

| 4 Meconium‐stained liquor | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.48 [0.13, 1.78] |

| 5 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.91 [0.12, 68.95] |

| 6 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.56 [1.09, 11.58] |

| 7 Maternal side effects (all) | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 8.73 [1.17, 65.00] |

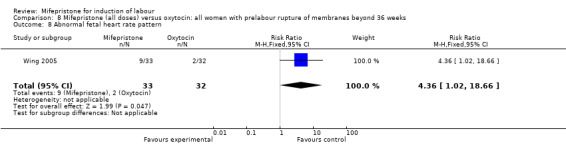

| 8 Abnormal fetal heart rate pattern | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.36 [1.02, 18.66] |

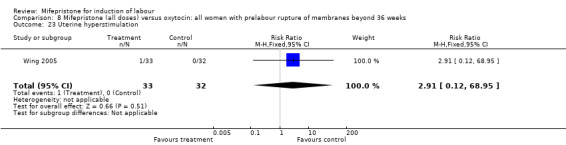

| 23 Uterine hyperstimulation | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.91 [0.12, 68.95] |

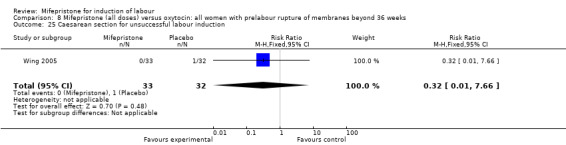

| 25 Caesarean section for unsuccessful labour induction | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.32 [0.01, 7.66] |

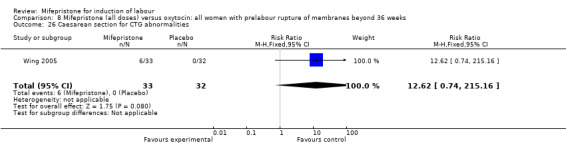

| 26 Caesarean section for CTG abnormalities | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 12.62 [0.74, 215.16] |

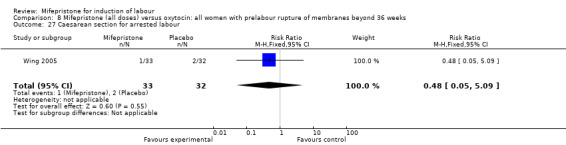

| 27 Caesarean section for arrested labour | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.48 [0.05, 5.09] |

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Mifepristone (all doses) versus oxytocin: all women with prelabour rupture of membranes beyond 36 weeks, Outcome 1 Vaginal delivery within 24 hours.

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Mifepristone (all doses) versus oxytocin: all women with prelabour rupture of membranes beyond 36 weeks, Outcome 2 Caesarean section.

8.3. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Mifepristone (all doses) versus oxytocin: all women with prelabour rupture of membranes beyond 36 weeks, Outcome 3 Epidural analgesia.

8.4. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Mifepristone (all doses) versus oxytocin: all women with prelabour rupture of membranes beyond 36 weeks, Outcome 4 Meconium‐stained liquor.

8.5. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Mifepristone (all doses) versus oxytocin: all women with prelabour rupture of membranes beyond 36 weeks, Outcome 5 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

8.6. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Mifepristone (all doses) versus oxytocin: all women with prelabour rupture of membranes beyond 36 weeks, Outcome 6 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

8.7. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Mifepristone (all doses) versus oxytocin: all women with prelabour rupture of membranes beyond 36 weeks, Outcome 7 Maternal side effects (all).

8.8. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Mifepristone (all doses) versus oxytocin: all women with prelabour rupture of membranes beyond 36 weeks, Outcome 8 Abnormal fetal heart rate pattern.

8.23. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Mifepristone (all doses) versus oxytocin: all women with prelabour rupture of membranes beyond 36 weeks, Outcome 23 Uterine hyperstimulation.

8.25. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Mifepristone (all doses) versus oxytocin: all women with prelabour rupture of membranes beyond 36 weeks, Outcome 25 Caesarean section for unsuccessful labour induction.

8.26. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Mifepristone (all doses) versus oxytocin: all women with prelabour rupture of membranes beyond 36 weeks, Outcome 26 Caesarean section for CTG abnormalities.

8.27. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Mifepristone (all doses) versus oxytocin: all women with prelabour rupture of membranes beyond 36 weeks, Outcome 27 Caesarean section for arrested labour.

Comparison 9. Mifepristone single dose (50 mg) versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

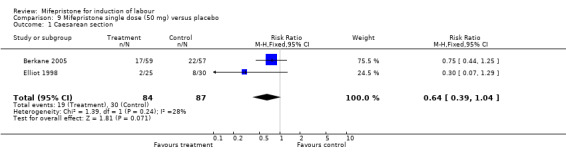

| 1 Caesarean section | 2 | 171 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.39, 1.04] |

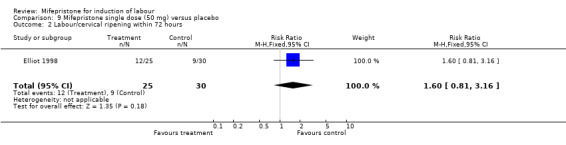

| 2 Labour/cervical ripening within 72 hours | 1 | 55 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.6 [0.81, 3.16] |

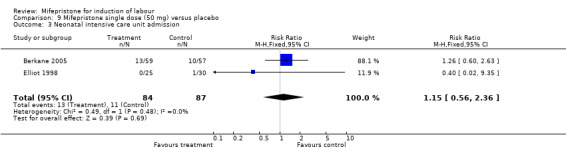

| 3 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 2 | 171 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.15 [0.56, 2.36] |

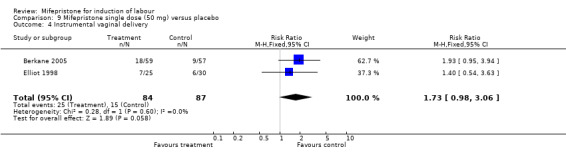

| 4 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 2 | 171 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.73 [0.98, 3.06] |

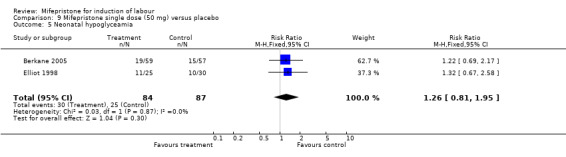

| 5 Neonatal hypoglyceamia | 2 | 171 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.26 [0.81, 1.95] |

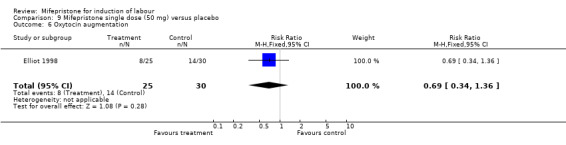

| 6 Oxytocin augmentation | 1 | 55 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.34, 1.36] |

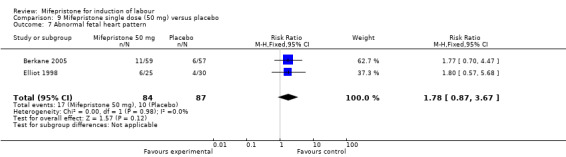

| 7 Abnormal fetal heart pattern | 2 | 171 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.78 [0.87, 3.67] |

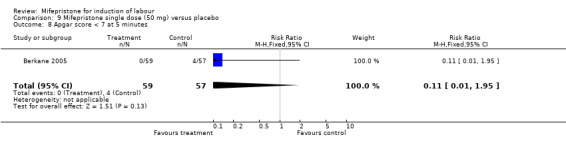

| 8 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 116 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.11 [0.01, 1.95] |

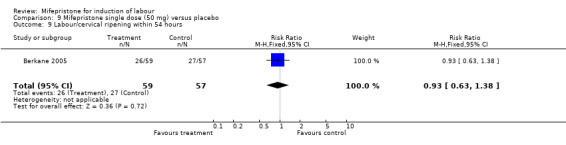

| 9 Labour/cervical ripening within 54 hours | 1 | 116 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.63, 1.38] |

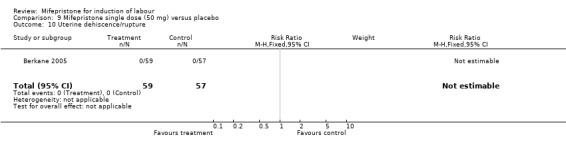

| 10 Uterine dehiscence/rupture | 1 | 116 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

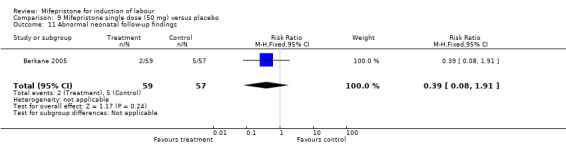

| 11 Abnormal neonatal follow‐up findings | 1 | 116 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.39 [0.08, 1.91] |

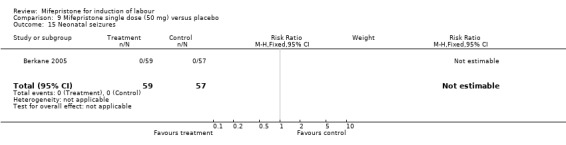

| 15 Neonatal seizures | 1 | 116 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

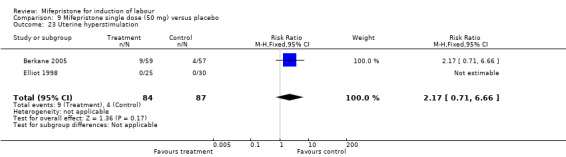

| 23 Uterine hyperstimulation | 2 | 171 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.17 [0.71, 6.66] |

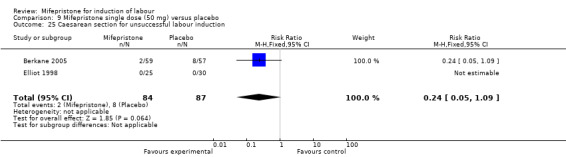

| 25 Caesarean section for unsuccessful labour induction | 2 | 171 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.24 [0.05, 1.09] |

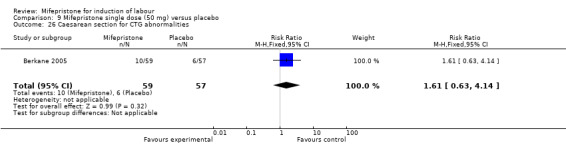

| 26 Caesarean section for CTG abnormalities | 1 | 116 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.61 [0.63, 4.14] |

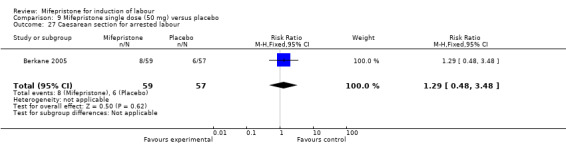

| 27 Caesarean section for arrested labour | 1 | 116 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.29 [0.48, 3.48] |

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Mifepristone single dose (50 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 1 Caesarean section.

9.2. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Mifepristone single dose (50 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 2 Labour/cervical ripening within 72 hours.

9.3. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Mifepristone single dose (50 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 3 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

9.4. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Mifepristone single dose (50 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 4 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

9.5. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Mifepristone single dose (50 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 5 Neonatal hypoglyceamia.

9.6. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Mifepristone single dose (50 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 6 Oxytocin augmentation.

9.7. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Mifepristone single dose (50 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 7 Abnormal fetal heart pattern.

9.8. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Mifepristone single dose (50 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 8 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

9.9. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Mifepristone single dose (50 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 9 Labour/cervical ripening within 54 hours.

9.10. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Mifepristone single dose (50 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 10 Uterine dehiscence/rupture.

9.11. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Mifepristone single dose (50 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 11 Abnormal neonatal follow‐up findings.

9.15. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Mifepristone single dose (50 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 15 Neonatal seizures.

9.23. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Mifepristone single dose (50 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 23 Uterine hyperstimulation.

9.25. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Mifepristone single dose (50 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 25 Caesarean section for unsuccessful labour induction.

9.26. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Mifepristone single dose (50 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 26 Caesarean section for CTG abnormalities.

9.27. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Mifepristone single dose (50 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 27 Caesarean section for arrested labour.

Comparison 10. Mifepristone single dose (200 mg) versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Caesarean section | 3 | 352 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.59, 1.30] |

| 3 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 3 | 352 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.16 [0.70, 1.92] |

| 4 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 2 | 172 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.78 [1.01, 3.13] |

| 5 Neonatal hypoglyceamia | 2 | 172 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.24 [0.80, 1.93] |

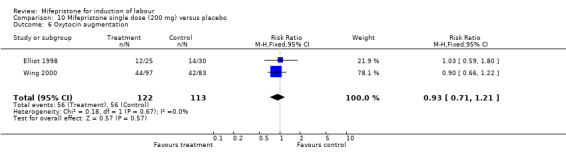

| 6 Oxytocin augmentation | 2 | 235 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.71, 1.21] |

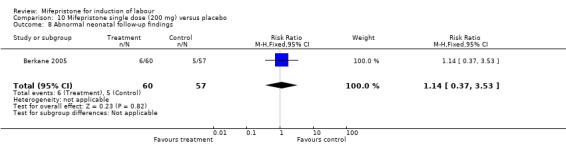

| 8 Abnormal neonatal follow‐up findings | 1 | 117 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.37, 3.53] |

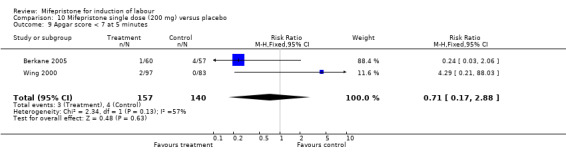

| 9 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 2 | 297 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.17, 2.88] |

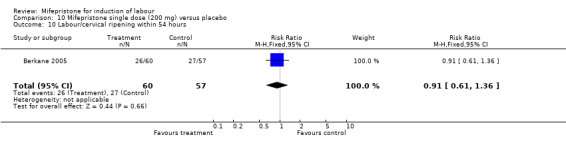

| 10 Labour/cervical ripening within 54 hours | 1 | 117 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.61, 1.36] |

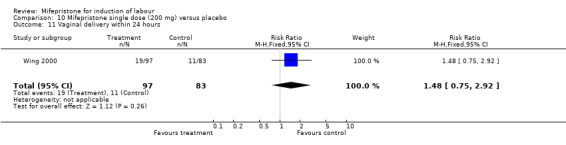

| 11 Vaginal delivery within 24 hours | 1 | 180 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.48 [0.75, 2.92] |

| 13 Labour/cervical ripening within 72 hours | 1 | 55 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.13 [1.15, 3.97] |

| 19 Abnormal fetal heart pattern | 3 | 352 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.37 [1.38, 4.05] |

| 20 Uterine dehiscence/rupture | 1 | 117 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 23 Uterine hyperstimulation | 3 | 352 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.73 [0.56, 5.36] |

| 25 Caesarean section for unsuccessful labour induction | 2 | 297 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.53 [0.21, 1.31] |

| 26 Caesarean section for CTG abnormalities | 3 | 352 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.74 [0.84, 3.61] |

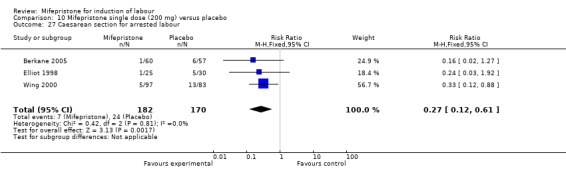

| 27 Caesarean section for arrested labour | 3 | 352 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.27 [0.12, 0.61] |

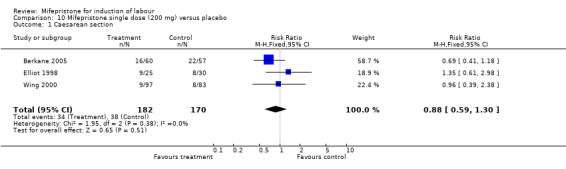

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Mifepristone single dose (200 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 1 Caesarean section.

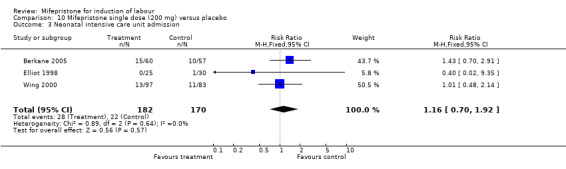

10.3. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Mifepristone single dose (200 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 3 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

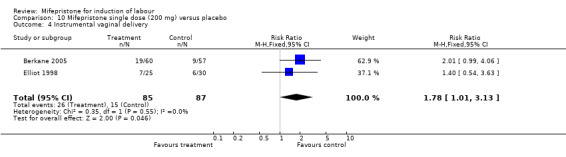

10.4. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Mifepristone single dose (200 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 4 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

10.5. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Mifepristone single dose (200 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 5 Neonatal hypoglyceamia.

10.6. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Mifepristone single dose (200 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 6 Oxytocin augmentation.

10.8. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Mifepristone single dose (200 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 8 Abnormal neonatal follow‐up findings.

10.9. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Mifepristone single dose (200 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 9 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

10.10. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Mifepristone single dose (200 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 10 Labour/cervical ripening within 54 hours.

10.11. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Mifepristone single dose (200 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 11 Vaginal delivery within 24 hours.

10.13. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Mifepristone single dose (200 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 13 Labour/cervical ripening within 72 hours.

10.19. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Mifepristone single dose (200 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 19 Abnormal fetal heart pattern.

10.20. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Mifepristone single dose (200 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 20 Uterine dehiscence/rupture.

10.23. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Mifepristone single dose (200 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 23 Uterine hyperstimulation.

10.25. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Mifepristone single dose (200 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 25 Caesarean section for unsuccessful labour induction.

10.26. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Mifepristone single dose (200 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 26 Caesarean section for CTG abnormalities.

10.27. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Mifepristone single dose (200 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 27 Caesarean section for arrested labour.

Comparison 11. Mifepristone single dose (400 mg) versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

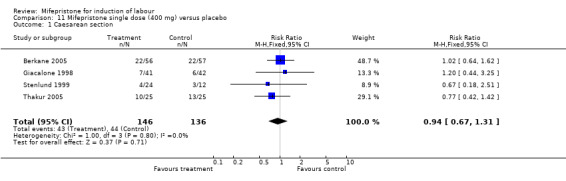

| 1 Caesarean section | 4 | 282 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.67, 1.31] |

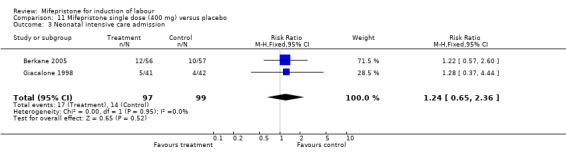

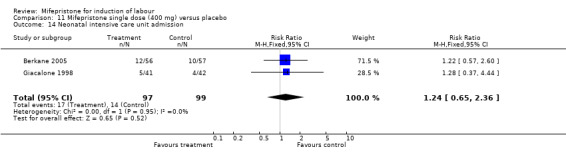

| 3 Neonatal intensive care admission | 2 | 196 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.24 [0.65, 2.36] |

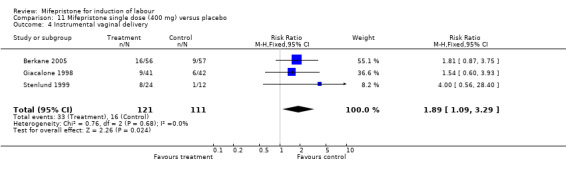

| 4 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 3 | 232 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.89 [1.09, 3.29] |

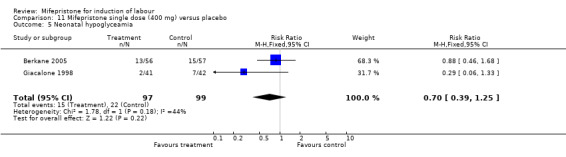

| 5 Neonatal hypoglyceamia | 2 | 196 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.39, 1.25] |

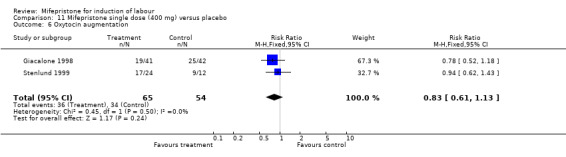

| 6 Oxytocin augmentation | 2 | 119 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.61, 1.13] |

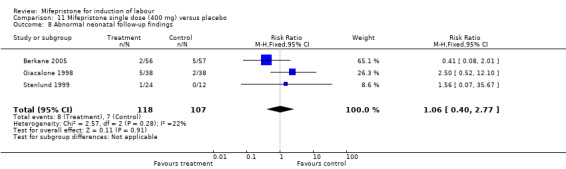

| 8 Abnormal neonatal follow‐up findings | 3 | 225 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.40, 2.77] |

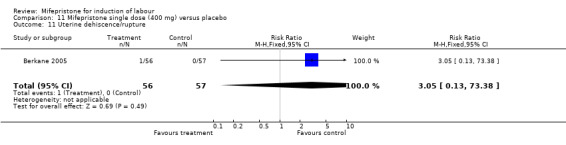

| 11 Uterine dehiscence/rupture | 1 | 113 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.05 [0.13, 73.38] |

| 12 Labour/cervical ripening within 54 hours | 1 | 346 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.74, 1.40] |

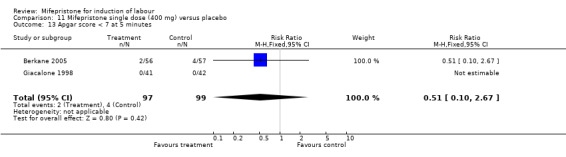

| 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 2 | 196 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.10, 2.67] |

| 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 2 | 196 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.24 [0.65, 2.36] |

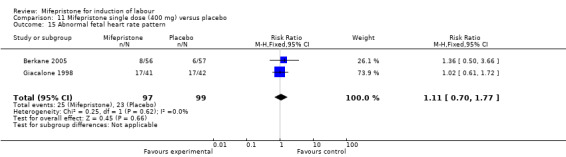

| 15 Abnormal fetal heart rate pattern | 2 | 196 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.70, 1.77] |

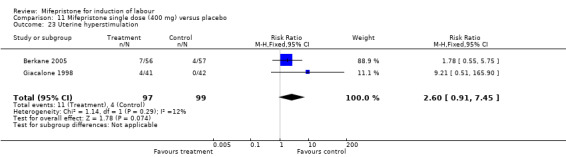

| 23 Uterine hyperstimulation | 2 | 196 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.60 [0.91, 7.45] |

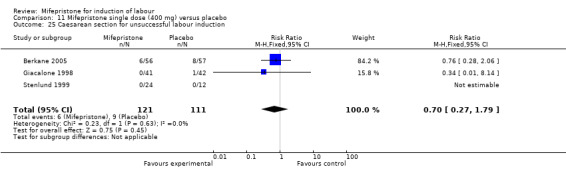

| 25 Caesarean section for unsuccessful labour induction | 3 | 232 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.27, 1.79] |

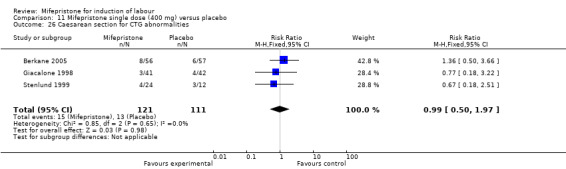

| 26 Caesarean section for CTG abnormalities | 3 | 232 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.50, 1.97] |

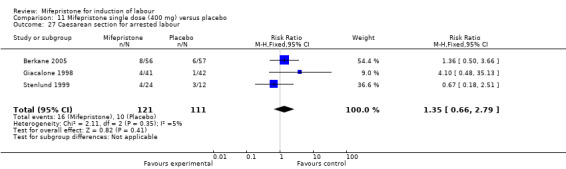

| 27 Caesarean section for arrested labour | 3 | 232 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.35 [0.66, 2.79] |

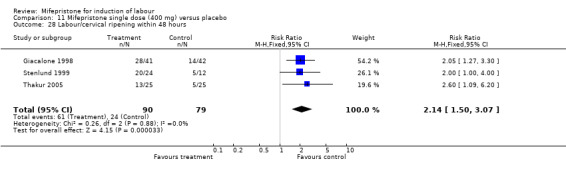

| 28 Labour/cervical ripening within 48 hours | 3 | 169 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.14 [1.50, 3.07] |

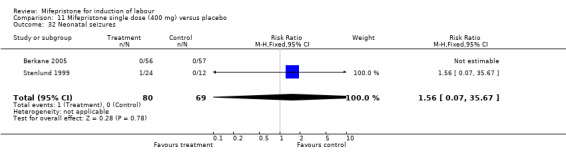

| 32 Neonatal seizures | 2 | 149 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.56 [0.07, 35.67] |

11.1. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Mifepristone single dose (400 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 1 Caesarean section.

11.3. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Mifepristone single dose (400 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 3 Neonatal intensive care admission.

11.4. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Mifepristone single dose (400 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 4 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

11.5. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Mifepristone single dose (400 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 5 Neonatal hypoglyceamia.

11.6. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Mifepristone single dose (400 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 6 Oxytocin augmentation.

11.8. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Mifepristone single dose (400 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 8 Abnormal neonatal follow‐up findings.

11.11. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Mifepristone single dose (400 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 11 Uterine dehiscence/rupture.

11.12. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Mifepristone single dose (400 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 12 Labour/cervical ripening within 54 hours.

11.13. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Mifepristone single dose (400 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

11.14. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Mifepristone single dose (400 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

11.15. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Mifepristone single dose (400 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 15 Abnormal fetal heart rate pattern.

11.23. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Mifepristone single dose (400 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 23 Uterine hyperstimulation.

11.25. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Mifepristone single dose (400 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 25 Caesarean section for unsuccessful labour induction.

11.26. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Mifepristone single dose (400 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 26 Caesarean section for CTG abnormalities.

11.27. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Mifepristone single dose (400 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 27 Caesarean section for arrested labour.

11.28. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Mifepristone single dose (400 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 28 Labour/cervical ripening within 48 hours.

11.32. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Mifepristone single dose (400 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 32 Neonatal seizures.

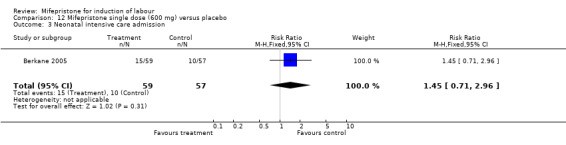

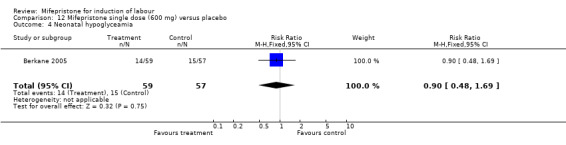

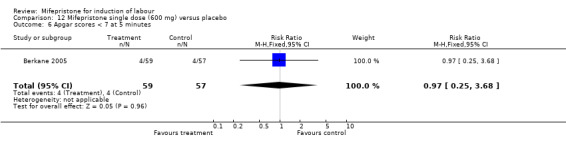

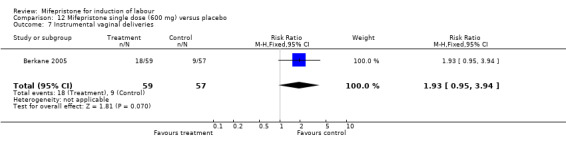

Comparison 12. Mifepristone single dose (600 mg) versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

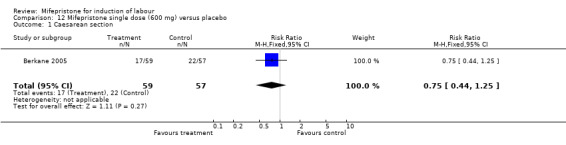

| 1 Caesarean section | 1 | 116 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.44, 1.25] |

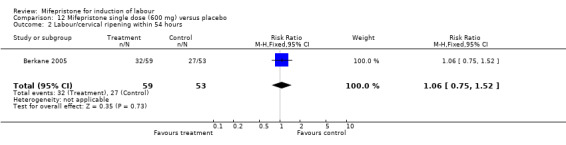

| 2 Labour/cervical ripening within 54 hours | 1 | 112 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.75, 1.52] |

| 3 Neonatal intensive care admission | 1 | 116 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.45 [0.71, 2.96] |

| 4 Neonatal hypoglyceamia | 1 | 116 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.48, 1.69] |

| 6 Apgar scores < 7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 116 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.25, 3.68] |

| 7 Instrumental vaginal deliveries | 1 | 116 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.93 [0.95, 3.94] |

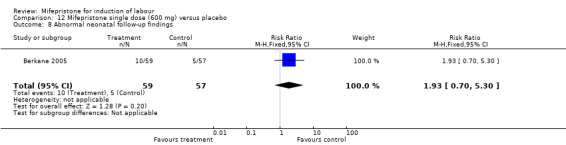

| 8 Abnormal neonatal follow‐up findings | 1 | 116 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.93 [0.70, 5.30] |

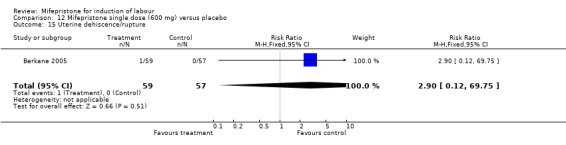

| 15 Uterine dehiscence/rupture | 1 | 116 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.9 [0.12, 69.75] |

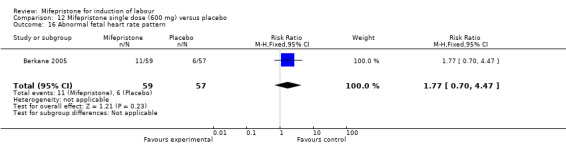

| 16 Abnormal fetal heart rate pattern | 1 | 116 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.77 [0.70, 4.47] |

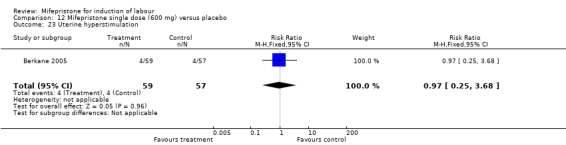

| 23 Uterine hyperstimulation | 1 | 116 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.25, 3.68] |

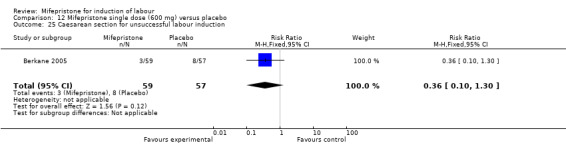

| 25 Caesarean section for unsuccessful labour induction | 1 | 116 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.36 [0.10, 1.30] |

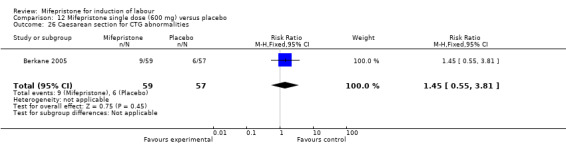

| 26 Caesarean section for CTG abnormalities | 1 | 116 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.45 [0.55, 3.81] |

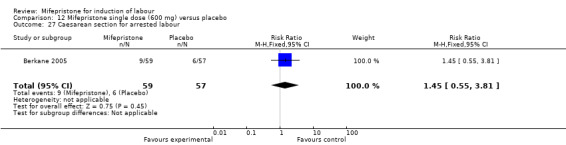

| 27 Caesarean section for arrested labour | 1 | 116 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.45 [0.55, 3.81] |

12.1. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Mifepristone single dose (600 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 1 Caesarean section.

12.2. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Mifepristone single dose (600 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 2 Labour/cervical ripening within 54 hours.

12.3. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Mifepristone single dose (600 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 3 Neonatal intensive care admission.

12.4. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Mifepristone single dose (600 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 4 Neonatal hypoglyceamia.

12.6. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Mifepristone single dose (600 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 6 Apgar scores < 7 at 5 minutes.

12.7. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Mifepristone single dose (600 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 7 Instrumental vaginal deliveries.

12.8. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Mifepristone single dose (600 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 8 Abnormal neonatal follow‐up findings.

12.15. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Mifepristone single dose (600 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 15 Uterine dehiscence/rupture.

12.16. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Mifepristone single dose (600 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 16 Abnormal fetal heart rate pattern.

12.23. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Mifepristone single dose (600 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 23 Uterine hyperstimulation.

12.25. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Mifepristone single dose (600 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 25 Caesarean section for unsuccessful labour induction.

12.26. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Mifepristone single dose (600 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 26 Caesarean section for CTG abnormalities.

12.27. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Mifepristone single dose (600 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 27 Caesarean section for arrested labour.

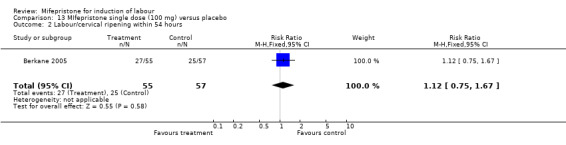

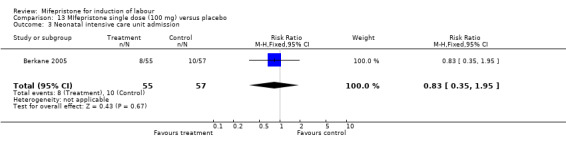

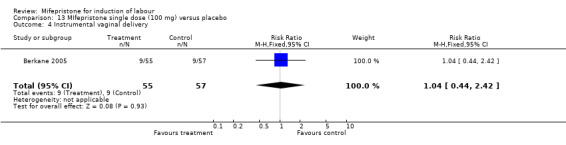

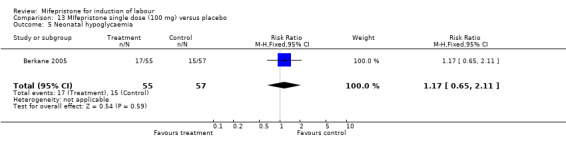

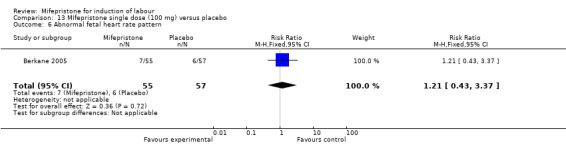

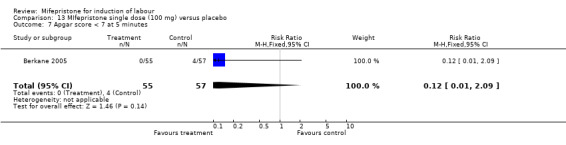

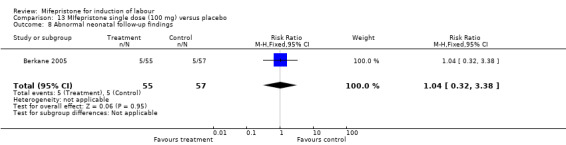

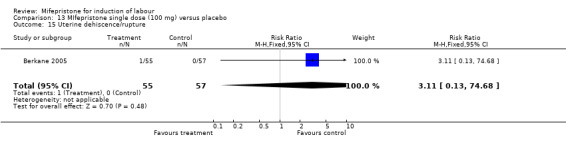

Comparison 13. MIfepristone single dose (100 mg) versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

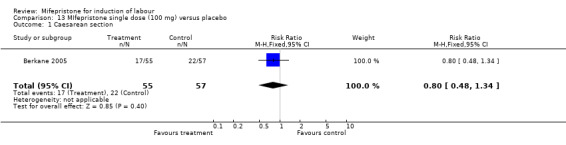

| 1 Caesarean section | 1 | 112 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.48, 1.34] |

| 2 Labour/cervical ripening within 54 hours | 1 | 112 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.12 [0.75, 1.67] |

| 3 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 1 | 112 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.35, 1.95] |

| 4 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 112 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.44, 2.42] |

| 5 Neonatal hypoglycaemia | 1 | 112 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.17 [0.65, 2.11] |

| 6 Abnormal fetal heart rate pattern | 1 | 112 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.21 [0.43, 3.37] |

| 7 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 112 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.12 [0.01, 2.09] |

| 8 Abnormal neonatal follow‐up findings | 1 | 112 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.32, 3.38] |

| 15 Uterine dehiscence/rupture | 1 | 112 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.11 [0.13, 74.68] |

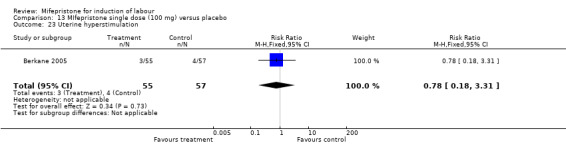

| 23 Uterine hyperstimulation | 1 | 112 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.18, 3.31] |

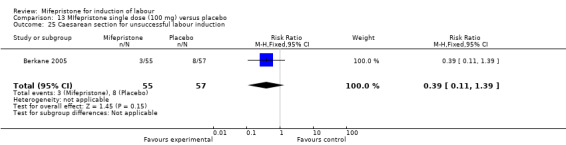

| 25 Caesarean section for unsuccessful labour induction | 1 | 112 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.39 [0.11, 1.39] |

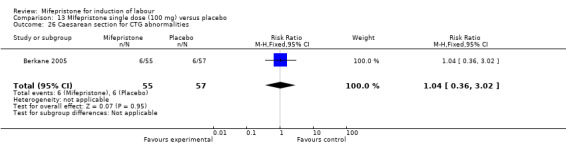

| 26 Caesarean section for CTG abnormalities | 1 | 112 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.36, 3.02] |

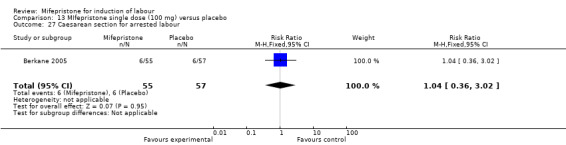

| 27 Caesarean section for arrested labour | 1 | 112 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.36, 3.02] |

13.1. Analysis.

Comparison 13 MIfepristone single dose (100 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 1 Caesarean section.

13.2. Analysis.

Comparison 13 MIfepristone single dose (100 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 2 Labour/cervical ripening within 54 hours.

13.3. Analysis.

Comparison 13 MIfepristone single dose (100 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 3 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

13.4. Analysis.

Comparison 13 MIfepristone single dose (100 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 4 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

13.5. Analysis.

Comparison 13 MIfepristone single dose (100 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 5 Neonatal hypoglycaemia.

13.6. Analysis.

Comparison 13 MIfepristone single dose (100 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 6 Abnormal fetal heart rate pattern.

13.7. Analysis.

Comparison 13 MIfepristone single dose (100 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 7 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

13.8. Analysis.

Comparison 13 MIfepristone single dose (100 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 8 Abnormal neonatal follow‐up findings.

13.15. Analysis.

Comparison 13 MIfepristone single dose (100 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 15 Uterine dehiscence/rupture.

13.23. Analysis.

Comparison 13 MIfepristone single dose (100 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 23 Uterine hyperstimulation.

13.25. Analysis.

Comparison 13 MIfepristone single dose (100 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 25 Caesarean section for unsuccessful labour induction.

13.26. Analysis.

Comparison 13 MIfepristone single dose (100 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 26 Caesarean section for CTG abnormalities.

13.27. Analysis.

Comparison 13 MIfepristone single dose (100 mg) versus placebo, Outcome 27 Caesarean section for arrested labour.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Berkane 2005.

| Methods | Double‐blind placebo controlled trial. 'Randomised'. Method unspecified. | |

| Participants | 346 women with cephalic, singleton pregnancies at term (37 ‐ 41 + 3 weeks' gestation) with an indication for induction of labour and an unfavourable cervix. | |

| Interventions | There were 6 intervention groups: oral mifepristone 50 mg (N = 59), oral mifepristone 100 mg (N = 55), oral mifepristone 200 mg (N = 60), oral mifepristone 400 mg (N = 56), oral mifepristone 600 mg (N = 59) and placebo (N = 57). Single‐dose therapy. Primary end point was the onset of labour at 45 or 54 hours post‐treatment. | |

| Outcomes | Sample size calculated from primary outcome measure onset of labour or Bishop score > 6 by 54 hours post‐treatment. Secondary measures of obstetrics, maternal, neonatal, and endocrine outcomes. | |

| Notes | 8 centre study in France, 35 patients were excluded from the analysis of efficacy but included in the analysis of tolerability. Authors were contacted and additional data on the outcomes of women with previous caesarean delivery, and the indication for caesarean sections are included. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Quote: "Patients were randomly allocated". No further information presented in the paper. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Unclear. No information given in the paper. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | Quotes: "double‐blind study"; "Each patient received a bottle containing 5 active or placebo tablets". Comment: probably done but unclear for personnel and outcome assessors. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "Thirty‐five patients were excluded from the analysis of efficacy but not from the analysis of tolerability". |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | All outcome data were reported or supplied by the authors on request. |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | Trial completed to include the intended sample size |

Elliot 1998.

| Methods | "Predetermined randomisation code". Double‐blind. | |

| Participants | 80 primigravid women, aged between 18 and 40 years, with normal, live, single baby with cephalic presentation. Gestation between 37 and 41.5 weeks, based on early ultrasound scan. Indication for induction of labour and Bishop score =/< 4. | |

| Interventions | There were 3 intervention groups: oral mifepristone 50 mg (N = 25), oral mifepristone 200 mg (N = 25), placebo (N = 30). Single‐dose therapy. Women were seen (on outpatient basis) at 24, 48, and 72 hours, and labour was induced by vaginal prostaglandins at 72 hours if labour had not occurred by then. | |

| Outcomes | Sample size calculated from primary outcome measure of 'spontaneous labour' or Bishop score > 6. The neonates were studied specifically for hypoglycaemia (definition: < 2.2 mmol/l). | |

| Notes | Dose in mifespristone group increased after interim analysis, from 50 to 200 mg. Further 5 control women recruited in second phase of trial. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Frydman 1992.

| Methods | Double‐blind randomised‐controlled trial. Tablets prepared by pharmacy. Randomisation based on permutation blocks of 4. | |

| Participants | 120 women with indication for induction of labour between 37 and 41 weeks. Bishop score < 4. Exclusion: medical conditions, non‐vertex presentation, > 1 previous caesarean section, multiple pregnancy, premature rupture of membranes. 112 women included in analyses: see Notes. | |

| Interventions | Mifepristone 200 mg orally for 2 days, or placebo. All women observed daily for 4 days; if not then in labour, induction by vaginal prostaglandins (cervix still unfavourable) or artificial rupture of membranes and oxytocin (favourable cervix). | |

| Outcomes | Duration of labour, obstetric and neonatal outcome, PGE2 tablets, oxytocin dose, neonatal glucose and blood pressure on days 1 and 2. | |

| Notes | 8 women required delivery by CS at < 12 hours after initial treatment because of fetal distress or severe hypertension (3 mifepristone; 5 placebo). They were not included in analyses. Preliminary results on 62 women published in Lancet letter. Full results published in French in 1993. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Quote: "women were randomly allocated". Comment: "detailed information included in paper". |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Adequate. "Used a balanced randomisation list obtained by premutation block". |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | Adequate, as placebo and mifepristone tablets were visually identical and externally produced. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | 8 patients excluded (3 in mifepristone group and 5 in placebo group) as they required caesareans for medical reasons within 12 hours. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | Adequate. All listed outcomes were reported on |