Abstract

SUMMARY

Clonal evolution and intratumoral heterogeneity drive cancer progression through unknown molecular mechanisms. To address this issue, functional differences between single T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) clones were assessed using a zebrafish transgenic model. Functional variation was observed within individual clones, with a minority of clones enhancing growth rate and leukemia propagating potential with time. Akt pathway activation was acquired in a subset of these evolved clones, which increased the number of leukemia propagating cells through activating mTORC1, elevated growth rate likely by stabilizing the Myc protein, and rendered cells resistant to dexamethasone, which was reversed by combined treatment with an Akt inhibitor. Thus, T-ALL clones spontaneously and continuously evolve to drive leukemia progression even in the absence of therapy-induced selection.

INTRODUCTION

Cancer is an evolutionary process whereby transformed cells continuously acquire genetic and/or epigenetic lesions to generate functionally distinct tumor cells. Natural selection then favors the clones with the best fitness for driving cancer progression, therapy resistance and relapse (Aparicio and Caldas, 2013). Genetic heterogeneity is increasingly recognized as an important biomarker of cancer progression and outcome. For example, increased tumor cell heterogeneity was recently correlated with chemotherapy resistance in renal cell carcinoma (Gerlinger et al., 2012) and metastasis in pancreatic adenocarcinoma (Yachida et al., 2010). Similar associations have been reported in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL), Acute Myelogenous Leukemia (AML) and Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL), where genetic diversity within the primary leukemia was correlated with an increased likelihood of drug resistance, disease progression, and relapse (Anderson et al., 2011; Ding et al., 2012; Landau et al., 2013; Mullighan et al., 2008; Notta et al., 2011). While these studies have provided valuable insight into intratumoral heterogentiy and patient outcome, analyses of bulk patient samples often identifies large numbers of mutations within a single tumor, making it difficult to determine how genetic diversity and acquired mutations promote cancer progression. Understanding the consequences of genetic heterogeneity necessarily require detailed functional analysis of multiple single cells contained within the same primary tumor.

Recent advances in genomic technologies have provided unique insights into the clonal relationships between cancer cells, and in some cases have documented the order by which genetic changes accumulate following progression and relapse. For example, the clonal relationship between primary and relapsed ALL was identified using copy number aberration analysis in matched patient samples. Continued clonal evolution and acquisition of new mutations occurred in a majority of relapse samples (Clappier et al., 2011; Mullighan et al., 2008), with most relapse disease arising from the evolution of an underrepresented clone contained within the primary leukemia. Whole genome sequencing studies have revealed that AML also undergoes clonal evolution from diagnosis to relapse, with 5 of 8 patients developing relapse from a genetically-distinct, minor clone that survived chemotherapy (Ding et al., 2012). Finally, 60% of CLL exhibited continued clonal evolution, where high clonal heterogeneity in the primary leukemia was associated with disease progression and prognosis (Landau et al., 2013), suggesting that clonal evolution is common and a likely an important driver of cancer progression. While these studies have detailed lineage relationships between leukemic clones and often identified genetic lesions correlated with progression and relapse, the functional effects of these mutations have not been fully assessed.

Cancer progression and relapse are driven by distinct and often-rare cancer cells referred to as tumor-propagating cells, or in blood cancers as leukemia-propagating cells (LPCs). If LPCs are retained following treatment, they will ultimately initiate relapse disease (Clarke et al., 2006). Despite the substantial number of genetic lesions that have been identified in relapse samples and the contention that these mutations likely modulate response to therapy, acquired mutations that increase the overall frequency of tumor-propagating cells following continued clonal evolution at the single cell level have not been reported. Such mutations would increase the pool of cells capable of driving continued tumor growth and progression, thereby increasing the likelihood of relapse. Although we have previously found that LPC frequency can increase in a given leukemia over time (Smith et al., 2010), it is unclear whether this was the result of continued clonal evolution or if a clone with inherently high LPC frequency simply outcompeted other cells within the leukemia.

T-ALL is an aggressive malignancy of transformed thymocytes with an overall good prognosis. Yet despite major therapeutic improvements for the treatment of primary T-ALL, a large fraction of patients relapse from retention of LPCs following therapy, often developing leukemia that is refractory to chemotherapies including glucocorticoids (Einsiedel et al., 2005; Pui et al., 2008). Importantly, T-ALL exhibits clonal evolution at relapse, suggesting that this process is an important driver of therapy resistance, enhanced growth, and leukemia progression (Clappier et al., 2011; Mullighan et al., 2008). Primary T-ALL is characterized by changes in several molecular pathways, including mutational activation of NOTCH and inactivation of CDKN2A, FBXW7, and PTEN (Van Vlierberghe and Ferrando, 2012). The Myc pathway is also a dominant oncogenic driver in vast majority of human T-ALL, resulting in part from NOTCH1 pathway activation (Palomero et al., 2006). Myc has also been recently shown to be a critical regulator of T-ALL progression (King et al., 2013), suggesting that identifying collaborating genetic events that synergize with Myc to enhance LPC frequency, leukemic cell growth, and resistance to therapy will likely be important to understanding human disease.

RESULTS

Continued clonal evolution generates subclonal variation to enhance LPC frequency and shorten disease latency

To gain insight into the functional role that tumor heterogeneity has on leukemia-propagating potential and latency, a cell transplantation-based screen was completed in which syngeneic zebrafish were engrafted with single, fluorescently-labeled clones isolated from primary Myc-induced T-ALL (Figure 1A). This approach mimics the process by which a single cell can reinitiate leukemia at relapse. Importantly, zebrafish Myc-induced T-ALL are molecularly similar to the subset of human T-ALL that expresses SCL and LMO2, mimicking an aggressive and common form of human disease (Blackburn et al., 2012; Langenau et al., 2005). Moreover, zebrafish Myc-induced T-ALL is heterogeneous and is often comprised of numerous clones that harbor unique T cell receptor beta (tcrβ) rearrangements, making it the ideal system with which to define the functional effects of intratumoral heterogeneity and clonal evolution. Myc-induced leukemias were generated to express a variety of fluorescent proteins including AmCyan, GFP, zsYellow, dsREDexpress, and mCherry. The monoclonality of each transplanted T-ALL was confirmed by genomic DNA analysis of tcrβ rearrangements (Table S1) and comparative genomic hybridization arrays (aCGH). Each monoclonal, primary transplanted T-ALL was then assessed for differences in latency, determined as the time required for >50% of the animal to be over-taken by fluorescently labeled T-ALL, and in the overall frequency of relapse-driving LPCs, as determined by limiting dilution transplantation into syngenic recipients (Figure 1A). Sort purity following FACS ranged from 87-98% and viability was >95% for all analyses. In total, 47 primary transplanted, fluorescently-labeled monoclonal T-ALL were derived from single LPC clones isolated from 16 different primary leukemias.

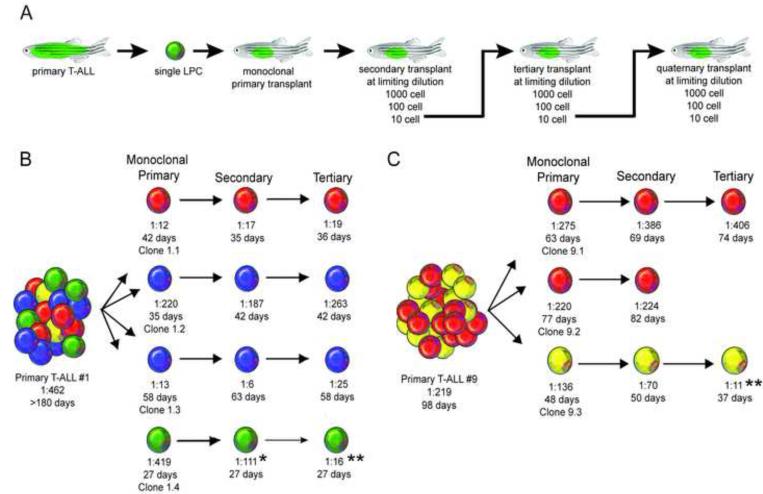

Figure 1. Clonal evolution drives intratumoral heterogeneity and can lead to increased leukemia propagating frequency.

(A) A schematic of the cell transplantation screen designed to identify phenotypic differences between single leukemic clones. (B, C) Schematic of results from primary T-ALL #1 (B) and T-ALL #9 (C). * denotes a significant reduction in LPC frequency from monoclonal primary to secondary transplant (p=0.02). ** denote a significant reduction in LPC frequency from monoclonal primary transplant T-ALL compared with tertiary transplanted leukemia (p<0.0001). Clones are color-coded based on tcrβ-rearrangements. See also Figures S1 and Table S1.

Array CGH analysis revealed that clones from the same leukemia often shared common focal amplifications and deletions irrespective of tcrβ rearrangement status. For example, all 4 clones from T-ALL #1 shared regional losses within chr1 and identical gains in chr2, chr7, chr12, chr 14, and chr25, despite harboring different tcrβ rearrangements (Figure S1A). Clones had additional genetic changes that were specific to each subclone, suggesting that zebrafish T-ALL clones were derived from a common ancestor and had undergone a branched evolution similar to that found in human patients (Mullighan et al., 2008 and Figure S1A-B). Clones isolated from the same primary T-ALL also commonly had different functional phenotypes. From primary T-ALL #1, clone 1.1 harbored a unique V15C1 tcrβ rearrangement and generated leukemias that contained 1 LPC for every 12 cells. By contrast, clone 1.4 was genetically distinct with a V17C2 rearrangement, and had a significantly lower LPC frequency of 1 in 419 cells (p<0.0001, Figure 1B and Table 1; Table S1). Functional variation was also observed within related clones. For example, clones 1.2 and 1.3 had the same V36C1 rearrangement, but had a nearly 17-fold difference in the overall numbers of LPCs (p<0.0001), suggesting that continued clonal evolution resulted in increased LPC function and frequency. Finally, individual clones isolated from T-ALL #1 also had significant differences in latency, with the median time to T-ALL onset ranging from 27 to 58 days in transplant animals (Figure 1B; Table S1, p<0.01). In total, functional variation between single clones was documented in 13 of 16 the primary T-ALL examined (Figures 1B-C; Figure S1B and Table S1), indicating that functional heterogeneity between leukemic clones is common.

Table 1.

Summary of clones that evolved increased LPC frequency.

| T-ALL | Limiting Dilution Transplant1 | LPC frequency2 | Latency (days)3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,000 cell | 100 cell | 10 cell | |||

| Primary 1 | 7/8 | 3/20 | 2/38 | 1:462 (871, 245) | >180 |

| Clone 1.4 | |||||

| primary transplant | 4/5 | 2/8 | 1/17 | 1:419 (1050, 167) | 27.1±2.1 |

| secondary transplant | 5/5 | 4/8 | 2/11 | 1:111 (259, 49) | 26.8±2.2 |

| tertiary transplant | 5/5 | 8/8 | 5/11 | 1:16 (36, 7) ** | 27.1±2.1 |

|

| |||||

| Primary 6 | 5/5 | 9/18 | 6/45 | 1:114 (193, 67) | 45 |

| Clone 6.1 | |||||

| primary transplant | 5/5 | 4/10 | 1/15 | 1:182 (417, 79) | 43.0±2.4 |

| secondary transplant | 3/3 | 6/6 | 3/10 | 1:25 (58, 10) | 53.4±2.9 |

| tertiary transplant | 3/3 | 6/6 | 6/20 | 1:26 (57, 13) *** | 45.0±3.0 |

|

| |||||

| Primary 8 | 4/5 | 5/34 | 5/82 | 1:447 (793, 251) | 115 |

| Clone 8.4 | |||||

| primary transplant | 3/3 | 2/6 | 2/10 | 1:267 (786, 91) | 35.0±3.1 |

| secondary transplant | 2/2 | 5/6 | 3/10 | 1:43 (88, 19) | 38.5±2.4 |

| tertiary transplant | 2/2 | 6/6 | 7/11 | 1:9 (21, 5) ** | 33.3±1.8 |

|

| |||||

| Primary 9 | 5/5 | 8/26 | 4/52 | 1:219 (378, 126) | 98 |

| Clone 9.3 | |||||

| primary transplant | 4/4 | 3/6 | 1/12 | 1:136 (365, 50) | 47.8±2.2 |

| secondary transplant | 2/2 | 4/6 | 2/8 | 1:70 (171, 29) | 50.2±2.8 |

| tertiary transplant | 2/2 | 5/5 | 6/10 | 1:11 (24, 4) ** | 37.6±2.9 |

|

| |||||

| Primary 10 | 5/5 | 6/20 | 3/42 | 1:225 (418, 121) | 49 |

| Clone 10.1 | |||||

| primary transplant | 3/3 | 2/6 | 0/10 | 1:263 (780, 88) | 78.4±4.1 |

| secondary transplant | 3/3 | 6/6 | 4/9 | 1:16 (42, 7) ** | 32.7±2.0 |

| tertiary transplant | 3/3 | 6/6 | 3/9 | 1:22 (58, 9) ** | 32.2±1.5 # |

|

| |||||

| Primary 14 | 6/7 | 5/36 | 3/72 | 1:509 (892, 290) | 82 |

| Clone 14.1 | |||||

| primary transplant | 3/3 | 1/5 | 0/10 | 1:356 (1101, 115) | 63.0±2.9 |

| secondary transplant | 3/3 | 4/6 | 2/10 | 1:74 (177, 31) | 51.3±4.3 |

| tertiary transplant | 2/2 | 5/5 | 5/9 | 1:12 (25, 5) ** | 37.1±2.7 ## |

The number of engrafted animals over the number of total animals transplanted at each dose.

The 95% confidence interval (CI) for LPC frequency is shown in parenthesis. Clones that increased the overall fraction of LPCs following serial passage are indicated.

, p<0.0001;

, p=0.0003.

Data are presented with ± standard error, where applicable. Clones that exhibited diminished latency from the primary to tertiary transplantation are noted.

, p<0.0001;

, p=0.016.

To directly assess if continued clonal evolution can impart functional consequences to LPC frequency and latency, T-ALL clones generated from single cells were serially passaged at limiting dilution, and recipient animals assessed for changes in time to leukemia regrowth and overall LPC frequency (n=3,767 transplant animals assessed). From this analysis, 6 of 47 clones underwent continued clonal evolution that resulted in an average 20-fold increase in LPC frequency when compared with the initial monoclonal, primary transplanted T-ALL (range: 7- to 30-fold, Figure 1B-C and Table 1). For example, clone 1.4 had an LPC frequency of 1:419, which increased following serial passaging to 1:16 (Figure 1B and Table 1). Further, two clones simultaneously evolved both elevated LPC frequency and reduced latency following serial passaging (clones 10.1 and 14.1, Table 1). Outgrowth of a contaminating clone was excluded in all cases by analysis of tcrβ rearrangements. The remaining 41 clones had no significant change in latency or LPC frequency following serial passaging (Table S1). Together, these data indicate that continued clonal evolution occurs in a small subset of T-ALL clones, and can lead to spontaneous changes within single cells to alter both LPC frequency and latency.

Independent pathways can regulate LPC frequency and growth rate

In analyzing the functional differences between clones and the subclonal variation acquired following serial passaging, we found that LPC frequency and latency often evolve independently, suggesting that these processes can be regulated by different molecular mechanisms (Table S1). To confirm this observation, equal numbers of LPCs from selected clones were transplanted into recipient fish and time to leukemia regrowth was assessed. From this analysis, we confirmed that clones with similar LPC frequency exhibited wide differences in time to leukemia onset (Figure 2A). Analysis of all serially passaged clones revealed no significant correlation between LPC frequency and latency (n=120, Figure 2B). EDU incorporation (Figure 2C) and phospo-H3 staining (data not shown) showed that proliferation rate correlated with time to leukemia regrowth in vivo, but did not correlate with overall LPC frequency. Apoptosis rates did not differ between clones (Figure S2A-B). Together, these data suggest that the pathways that regulate T-ALL latency/proliferation and LPC frequency need not be controlled by the same molecular mechanism; rather they can be evolved independently in a subset of T-ALL clones.

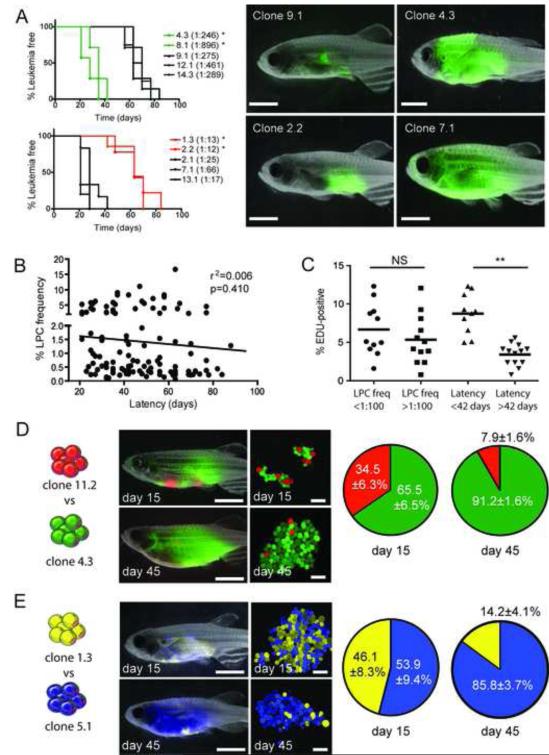

Figure 2. Mechanisms that drive leukemia propagating cell frequency and latency can evolve independently.

(A) Fish were transplanted with 25 LPCs from various clones and assessed for time to leukemia onset (n=8-10 animals transplanted per individual clone). * denotes significant differences in latency between clones that have low (upper left panel) or high (lower left panel) LPC frequencies (<0.001). Representative fluorescent images of animals following 28 days of engraftment are shown. (B) Correlation between LPC frequency and T-ALL latency across all clones. (C) EDU analysis of selected clones and correlation with LPC frequency and latency. Each datum point represents a single clone. NS=not significant. ** denote a significant difference in the percent of cells that are EDU-positive (p=0.0004). (D) Animals were transplanted with 25 LPCs from clone 11.2 (dsRED-positive, 1:78 LPC frequency, 88 days latency) and 25 LPCs from clone 4.3 (GFP-positive, 1:246 LPC frequency, 28 days latency). Representative images of whole fish and confocal images of T-ALL cells harvested at 15 days and 45 days post-transplantation. The percentages of dsRED-positive and GFP-positive cells at 15 days and 45 days were analyzed by FACS. Data are represented as ± SE (n= 4-7 transplant recipients per time-point). (E) 25 LPCs from clone 1.3 (zsYellow-positive, 1:13 LPC frequency, 58 days latency) were competed with 25 LPCs from clone 5.1 (amCyan-positive, 1:184 LPC frequency, 30 days latency), and analyzed as in (D). Scale bars, 5 mm in images of whole fish and 40 μm in confocal images. See also Figure S2.

To directly assess which of these processes dominate in driving T-ALL progression, in vivo competition experiments were performed between clones that exhibited inherent differences in latency and LPC frequency and differed in fluorescent protein expression. In each experiment, recipient fish were transplanted with 25 LPCs from two fluorescent clones and leukemia growth was assessed at 15 and 45 days post-transplantation. T-ALL clones with short latencies but low LPC frequency consistently outcompeted clones with longer latencies but high LPC frequency (Figure 2D-E). These data suggest that although leukemia propagating potential is required to re-initiate disease, clones with high proliferative capacity likely outcompete other cells during disease progression and relapse. Moreover, these data support our conclusion that T-ALL latency and leukemia-propagating potential need not be regulated by the same molecular mechanisms.

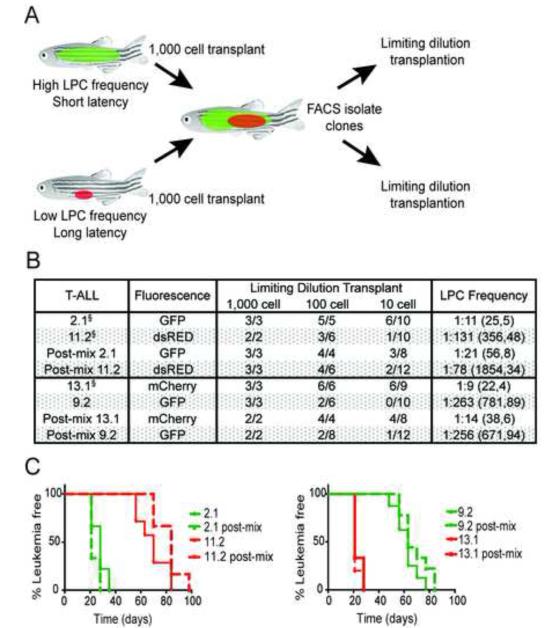

Cell intrinsic processes control LPC frequency and growth

We next performed a series of competition experiments to determine whether clones within a heterogeneous leukemia could functionally impact the LPC frequency and/or latency of other, genetically distinct clones. Clones that had different functional properties and labeled with different fluorescent proteins were transplanted into recipient animals at limiting dilution and assessed for the ability to alter the cellular fate of co-transplanted T-ALL cells. In the first set of experiments (Figure 3A), fluorescently-labeled clones with high LPC frequency and short latencies were co-transplanted with clones that had low LPC frequency and long latencies. After T-ALL formation, fluorescent T-ALL cells were isolated from recipient fish by FACS (>94% purity and >98% viability) and transplanted at limiting dilution. Mixing had no long-term effect on altering LPC frequency (Figure 3B) or latency (Figure 3C) in any clone tested. Next, we determined if continuous juxtacrine or paracrine signaling from clones with high LPC frequency was necessary to alter the frequency of LPCs in clones with low leukemia propagating potential. Specifically, T-ALL clones with high LPC frequency were transplanted into recipient fish and allowed to engraft for 7 days. Engrafted animals were then transplanted at limiting dilution with a clone with low LPC frequency (Figure S3A). Animals were assessed for engraftment of the second subclone at 45 days, and again, cell extrinsic signaling from clones with high LPC frequency did not impart elevated leukemia propagating potential to cells with low LPC frequency (Figure S3B). These data show that cell autonomous processes regulate growth kinetics and overall frequency of LPCs in most T-ALL clones.

Figure 3. LPC frequency and latency are regulated cell-autonomously in T-ALL.

(A) Schematic of the experimental design. (B) Summary of results with 95% confidence intervals shown in parenthesis. § indicates an independent limiting dilution cell transplantation experiment confirming similar results as those shown in Table S1. (C) Kaplan Meier analyses of leukemia re-growth in animals transplanted with individual clones alone or following mixing. Tumor-negative animals were excluded from analysis. See also Figure S3.

Clonal evolution can activate Akt signaling to increase both LPC frequency and growth in T-ALL

Although our data suggest that increased LPC frequency and growth rate can be acquired in clones through independent mechanisms, mutations in genes and pathways that simultaneously enhance both of these processes would likely be selected for within a heterogeneous leukemia. Thus, we completed a systematic genetic analysis to identify the pathways associated with elevated LPC frequency and reduced latency. We did not identify shared, recurrent genetic amplifications or deletions among the clones that had evolved high LPC frequency following serial passaging (n=5 clones analyzed by array CGH at both primary and tertiary transplant). We next analyzed 45 of 47 monoclonal primary transplanted T-ALL for recurrent point mutations common to human T-ALL pathogenesis, including six paired samples that consisted of a primary monoclonal transplanted T-ALL with low LPC frequency and the matched tertiary transplant that had evolved high LPC frequency. In total, notch1b, il7r, akt2, akt3, n-ras, h-ras, k-ras, fbxw7, ptpn11a, pik3ca, pikr1, pten-a and pten-b were assessed for known hotspot mutations in human T-ALL. Although we observed notch1 mutations in several clones (11 of 44), they were not exclusively associated with clones that had high LPC frequency, consistent with our previous report that activated Notch signaling does not elevate LPC frequency in Myc-driven T-ALL (Blackburn et al. 2012). Moreover, most notch1 mutations did not occur within the amino acid residues known to alter protein stability or lead to constitutively active Notch signaling (Table S2). Genetic alterations in other genes were not detected (Table S2).

Because our data suggested that both genetic and epigenetic modifications likely play a role in clonal evolution (Figure S4A-B), we next assessed clones with high LPC frequency for changes in the expression of a wide range of genes implicated in human T-ALL (Figure S4C and Table S3). Endogenous myc-a, myc-b or transgenic Myc expression were not altered following serial transplant, obviating the possibility that Myc transcript levels accounted for phenotypic changes in LPC frequency and/or latency in the Myc-induced zebrafish model (Figure S4C). Additionally, expression of genes that have been previously linked to T-ALL proliferation and self-renewal, including the Notch target gene hes1, and lmo2 and tal1 (McCormack et al., 2010; Van Vlierberghe and Ferrando, 2012), were not elevated in clones with high LPC frequency. In contrast, genes known to regulate the Akt pathway were frequently mis-expressed in clones with high LPC frequency (Table S3). For example, serially passaged clone 8.4 had acquired elevated expression of n-ras and h-ras, clone 10.1 increased expression of ptpn11, and clone 14.1 lost expression of both pten-a and pten-b (Figure S4C and Table S3).

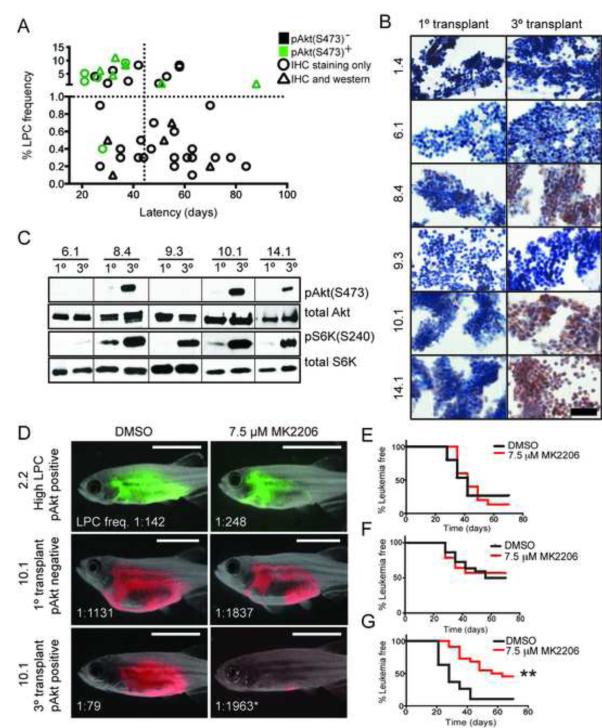

Based on these findings, we next assessed whether activation of the Akt pathway was directly associated with high LPC frequency. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) showed that 11 of 19 monoclonal T-ALL with high LPC frequency expressed high levels of phosphorylated Akt (pAkt), while only 1 of 26 clones with low LPC frequency exhibited pAkt staining (Figure 4A; Figure S4D). Western blot analysis confirmed IHC results for the subset of clones analyzed (Figure S4E). Additionally, 3 of 6 T-ALL clones showed a marked increase in pAkt staining following continued clonal evolution, concurrent with an increase in LPC frequency (Figure 4B). These same clones had exhibited robust gene expression changes associated with activation of the Akt pathway, noted above (clones 8.4, 10.1 and 14.1, Figure S4C). Acquired Akt activation in these evolved clones was confirmed by Western blot analysis for phosphorylation of Akt at serine 473 and phosphorylation of the downstream target S6-kinase (S6K, Figure 4C). Interestingly, treatment of evolved clone 10.1 with the epigenetic modifying drugs 5-azacytadine and sodium butyrate reduced LPC frequency and eliminated Akt signaling (Figure S4B and S4F), suggesting that the Akt signaling pathway can be regulated by epigenetic mechanisms and likely plays a functionally important role in regulating the overall numbers of LPCs in T-ALL.

Figure 4. Akt pathway activation is acquired by a subset of cells following clonal evolution and drives elevated LPC frequency and growth.

(A) Graphical summary of pAkt(S473) IHC from 46 monoclonal T-ALL. Green denotes samples that are pAkt-positive, and black have low or absent pAkt staining. Triangles represent clones that were confirmed for pAkt status by Western blot analysis. The vertical dotted line demarcates clones with short (<45 days) or long latencies, and the horizontal dotted line identifies clones with low (<1.0%) or high LPC frequency. pAkt-positivity is significantly associated with high LPC frequency (p<0.0001) and short latency (p=0.017), by Fisher Exact Test. (B) IHC analysis of pAkt staining in T-ALL clones. Scale bar, 50 μm. (C) Western blot analysis of selected clones from (B). (D) Animals were transplanted with the clones indicated and treated with MK2206 or DMSO for 5 days. Representative images at 28 days post-transplantation with LPC frequencies noted. * denotes a significant change in LPC frequency following MK2206 treatment (p<0.001). Scale bar, 5 mm. (E-G) Kaplan-Meier analyses for T-ALL regrowth following DMSO or MK2206 treatment for clone 2.2 (E), primary monoclonal transplant clone 10.1 (F), and tertiatry transplant clone 10.1 (G). ** denotes a significant change in T-ALL latency following MK2206 treatment (p<0.0001). See also Figure S4 and Table S2-S3.

To assess if clones had become dependent on Akt signaling for growth and LPC function in vivo, zebrafish were transplanted at limiting dilution with monoclonal primary transplant clone 10.1, which had low LPC frequency and was pAkt-negative, or tertiary transplant clone 10.1, which concurrently evolved high LPC frequency and pAkt-positivity. Transplanted animals were immediately placed in water containing DMSO or MK2206, an alloseric inhibitor of Akt, at a dose that effectively reduced phosphorylation of both Akt and S6K in vivo (Figure S4G). Zebrafish received drug treatment for 5 days, and transplanted animals were subsequently followed for altered LPC frequency (Figure 4D) and T-ALL latency (Figure 4E-G). MK2206 treatment had no effect on modulating LPC frequency or latency in clone 2.2, which exhibited high LPC frequency but lacked Akt pathway activation, or in the pAkt-negative primary monoclonal transplanted clone 10.1. However, MK2206 treatment reduced the overall frequency of LPCs by 25-fold in evolved, pAkt-positive clone 10.1, reverting it to a similar LPC frequency and latency as its pAkt-negative ancestral clone (Figure 4D and 4F-G; Figure S4H). Importantly, 15 of 17 zebrafish transplanted with pAkt-positive serially passaged clone 10.1 and treated with DMSO developed T-ALL, while only 11 of 21 zebrafish treated with the MK2206 developed T-ALL (p=0.034, Fisher Exact Test, Figure S4H). These data suggest that the Akt inhibitor not only reduced LPC frequency, but also efficiently killed LPCs, and provide further evidence that Akt plays an important role in LPC function.

Akt pathway activation enhances the frequency of LPCs through mTORC1

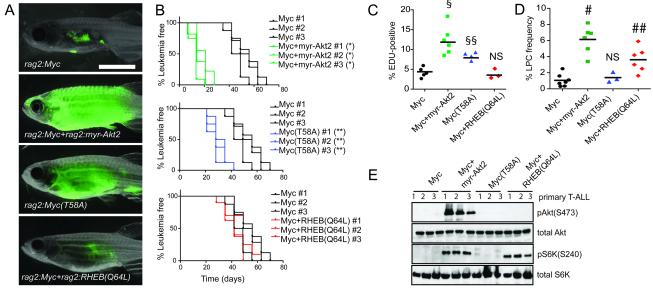

To provide conclusive genetic evidence that Akt signaling enhances LPC frequency, transgenic zebrafish were generated that expressed 1) rag2:Myc+rag2:GFP, 2) rag2:Myc+rag2:myristoylated-Akt2 (myr-Akt2)+rag2:GFP or 3) rag2:myr-Akt2+rag2:GFP. The myristoylated-Akt2 transgene leads to constitutive activation of Akt signaling in the Myc-induced zebrafish T-ALL model (Gutierrez et al., 2009) and significantly enhanced time to primary T-ALL onset when compared to Myc-alone expressing T-ALL (25 +/−4 days compared with 62 +/−17 days, Figure S5A-B). In contrast, zebrafish that expressed only rag2:myr-Akt2 failed to develop T-ALL over the 180 days of observation (n=7), and are in agreement with earlier work indicating that Akt signaling induces T-ALL in zebrafish with very low penetrance (Gutierrez et al., 2011). Upon transplantation of 25 LPCs, T-ALL that expressed both Myc and myr-Akt2 reformed leukemia 35 days faster than those that expressed Myc alone (Figure 5A-B), likely due to a substantial increase in proliferation in Myc+myr-Akt2 cells (Figure 5C). Constitutive Akt signaling also increased the overall LPC frequency by an average of 5.8-fold when compared to those that expressed only Myc (Figure 5D and Table S4). Activation of the Akt pathway by the myr-Akt2 transgene was verified by Western blot analysis for phosphorylated Akt and S6K (Figure 5E). Importantly, constitutive activation of Akt also shortened latencies in both primary and transplant T-ALL in the notch1aICD-induced zebrafish model (Figure S5C-D), and significantly increased the LPC frequency by 12-fold when compared to notch1aICD-alone expressing T-ALL (Figure S5E and Table S4), demonstrating that the Akt pathway can synergize with multiple oncogenes to enhance LPC frequency.

Figure 5. The Akt pathway increases LPC frequency through downstream activation of mTORC1 and shortens latency by augmenting Myc stability.

(A) Representative images of zebrafish that were transplanted with 25 LPCs from T-ALL expressing GFP and the indicated constructs (3 T-ALL per genotype, n=35 animals transplanted per primary leukemia) at 28 days post-transplantation. (B) Kaplan-Meier analyses of time to T-ALL regrowth for each genotype and compared to Myc alone expressing T-ALL. * denotes a significant difference in latency of p<0.0001, and ** indicate a significant difference in latency of p=0.003. (C) EDU analysis of transgenic T-ALL. Each datum point represents the percent EDU-positive cells for one T-ALL. § represents a significant difference of p<0.0001 and §§ denote a significant difference of p=0.004, when compared to Myc alone expressing T-ALL. (D) Graph showing LPC frequency within each transgenic group. Each point represents data for one primary T-ALL. # denotes a significant difference in LPC frequency of p<0.0001 and ## indicate a significant difference in LPC frequency of p=0.0025 when compared to Myc alone expressing T-ALL. NS denotes no significant difference. (E) Western blot analysis. See also Figure S5 and Table S4.

To rapidly identify candidate molecular pathways acting downstream of Akt that are required for continued T-ALL maintenance and growth, monoclonal T-ALL were treated ex vivo with inhibitors to various Akt target pathways. All pAkt-positive clones could be partially killed with MK2206 and the mTORC1 inhibitors Torisel and Rapamycin, but not with β-catenin or NF-κβ pathway inhibitors (Figure S5F). These compounds had no effect on the pAkt-negative clones. Efficacy of Torisel in blocking S6K phosphorylation was verified by Western blot analysis (Figure S5G). Based on this data, transgenic zebrafish were generated that over-expressed constitutively active RHEB(Q64L), which specifically activates the mTORC1 pathway (Jiang and Vogt, 2008). Akt is also known to stabilize the Myc protein through down-regulation of GSK-3β, preventing phosphorylation of Myc at threonine 58 and blocking its degradation through the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway (Bonnet et al., 2011). Additionally, we had observed that a subset of pAkt-positive clones over-expressed the Myc target genes ocd1, cd25a and cad, without concurrent increase in transgenic or endogenous Myc transcript levels (Figure S4C and Table S3), suggesting that Myc protein may be stabilized in these cells. Therefore, zebrafish T-ALL were also generated that over-expressed Myc(T58A), a mutant that is inefficiently degraded by the proteasome and mimics the effects of pAkt stabilization. Zebrafish expressing either rag2:Myc+rag2:RHEB(Q64L)+rag2:GFP and rag2:Myc(T58A)+rag2:GFP developed early onset primary T-ALL when compared with animals that expressed only rag2:Myc+rag2:GFP (Figure S5A-B). Importantly, rag2:RHEB(Q64L)+rag2:GFP animals did not develop T-ALL over 180 days of observation, indicating that mTORC1 activation alone may not be sufficient for T-ALL formation (n=9).

To assess the effects of pAkt regulated pathways on leukemia regrowth and LPC frequency, T-ALL cells from each genotype were transplanted at limiting dilution and assessed for time to leukemia onset or overall LPC frequency. T-ALL expressing Myc(T58A) re-initiated leukemia 19±4.3 days faster than Myc-expressing T-ALL, while RHEB(Q64L) over-expression had no effect on latency (Figure 5A-B). Similarly, Myc(T58A) but not RHEB(Q64L) T-ALL cells were significantly more proliferative than Myc-induced T-ALL (Figure 5C). Apoptosis rates did not differ between any transgenic T-ALL (Figure S5H), suggesting that proliferation rather than apoptosis rates are largely responsible for differences in latency. Limiting dilution cell transplantation experiments revealed that stabilized Myc(T58A) had no effect on LPC frequency. By contrast, RHEB(Q64L) expression significantly enhanced LPC frequency by an average of 4-fold when compared to Myc-alone expressing leukemias (Figure 5D; Table S4). Phosphorylation of S6K and expression of Myc target genes were verified in all transgenic T-ALL analyzed (Figure 5E; Figure S5I). No overt differences in morphology and T-ALL molecular subtype were observed between any transgenic T-ALL (Figure S5J-K). These data show that the Akt signaling may act through two independent downstream pathways to increase T-ALL growth, likely by stabilizing Myc protein to enhance proliferation rates, and to increase the overall frequency of LPCs through activation of mTORC1.

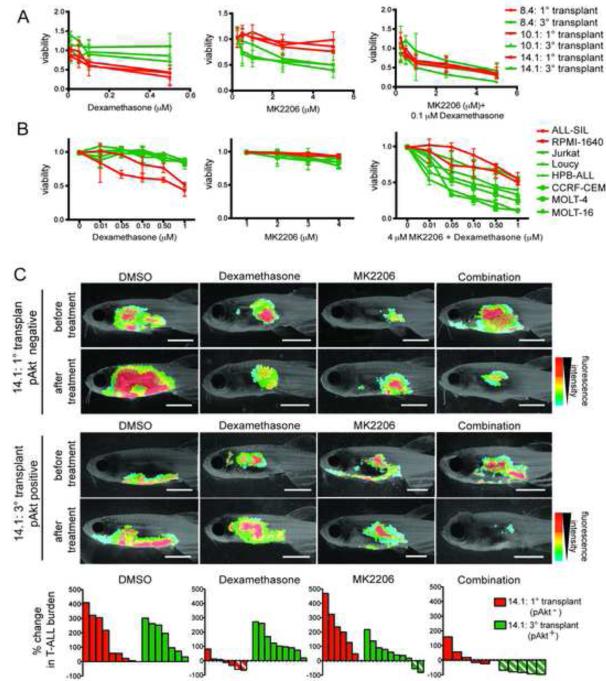

Akt activation following clonal evolution also renders cells resistant to glucocorticoid therapy

Treatment of T-ALL with the glucocorticoid dexamethasone often leads to acquired drug resistance in patients, which can be partly attributed to PTEN loss and activation of the Akt pathway (Beesley et al., 2009; Piovan et al., 2013; Schult et al., 2012; Silva et al., 2008). Based on these reports, we questioned if T-ALL clones spontaneously developed dexamethasone resistance following clonal evolution and activation of the Akt signaling pathway. Indeed, ex vivo drug treatment showed that the three T-ALL clones that were pAkt-negative as primary monoclonal T-ALL were killed by dexamethasone, while these same clones had become refractory to glucocortocoid-induced cell killing following clonal evolution and Akt pathway activation (Figure 6A). Combined treatment with either the Akt inhibitor MK2206 or the PIK3C inhibitor PI103 re-sensitized pAkt-positive clones to dexamethasone-induced killing (Figures 6A; Figure S6A), suggesting that inhibition of Akt is responsible for the reduced viability of these clones. Similar results were also obtained using additional pAkt-positive and pAkt-negative primary monoclonal transplant clones (Figure S6B), and human T-ALL cells (Figure 6B), where pAkt status predicted a reduced response to dexamethasone-induced killing, which could be restored with the addition of MK2206 (Chan et al., 2007; Palomero et al., 2007). Finally, drug combinations were also tested in vivo. Similar to the ex vivo results, dexamethasone treatment killed T-ALL in animals transplanted with pAkt-negative, primary monoclonal transplant clone 14.1, but the evolved, pAkt-positive cells were largely refractory to treatment (Figure 6C). The pAkt-positive T-ALL was effectively killed by the combination of dexamethasone and MK2206, resulting in almost complete T-ALL regression. These experiments provide evidence that an Akt inhibitor can re-sensitize refractory T-ALL cells to dexamethasone-induced killing in vivo and demonstrate that T-ALL clones can spontaneously develop resistance to chemotherapy as a result of clonal evolution and that this can occur without selection induced by prior drug exposure.

Figure 6. Dexamethasone resistance is acquired following Akt pathway activation in clonally evolved cells and can be overcome by combined treatment with MK2206.

(A) Primary monoclonal T-ALL that were pAkt-negative (red) and tertiary transplanted T-ALL that were pAkt-positive (green) were treated ex vivo as indicated and assessed for viability (n=6 replicates per clone). Error bars are ± SE. (B) Human cell lines with (green) or without (red) active Akt signaling were treated in vitro as indicated. Each point is the average viability after 24 hr of drug treatment (n=3 replicates per cell line). Error bars ± SE. (C) Representative images of leukemic fish prior to or 4 days after drug treatment with DMSO, 350 mg/L Dexamethasone, 3.5 μM MK2206 or 350 mg/L Dexamethasone+3.5 μM MK2206. Clone name and pAkt status are shown to the left. Waterfall plots at the bottom summarize the in vivo T-ALL responses. Each bar denotes the percent change in T-ALL burden within a single animal, those with diagonal lines indicate >50% reduction in T-ALL burden. See also Figure S6.

DISCUSSION

The transformation from a normal to a tumorigenic cell is generally thought to follow a Darwinian evolutionary model, ultimately culminating in clonal evolution producing tumor cells that are well-adapted to proliferate and to overcome the selective pressures of metabolic stress, hypoxia, radiotherapy and chemotherapy (Gerlinger and Swanton, 2010). In response to therapy, established cancers can continue to amass genetic and epigenetic lesions to enhance their propensity to form relapse. In support of this theory, genetic heterogeneity has been described in most cancer types and continued clonal evolution at relapse has been documented in several cancers. Moreover, heterogeneity has been correlated with important clinical features including progression, therapy resistance, and relapse (Almendro et al., 2013; Gerlinger and Swanton, 2010). Although the acquisition of genetic mutations at relapse has been well described, few studies have documented continued clonal evolution in the absence of therapy and the spontaneous acquisition of drug-resistant clones. For example, untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemias exhibit continued clonal evolution, ultimately resulting in spontaneous acquisition of genetic lesions that impart drug-resistance (Landau et al., 2013). However, these studies failed to correlate clonal evolution with specific features of progression, including shortened latency and enhanced LPC frequency, nor did they identify mechanistic drivers responsible for therapy resistance following continued clonal evolution. Our work follows clonal evolution within single leukemic cells and directly associates functional consequences of clonal evolution with specific cellular features including therapy resistance. Moreover, we have discovered key oncogenic pathways responsible for changing the cellular phenotypes of leukemic cells following clonal evolution.

Utilizing the zebrafish transgenic T-ALL model and large-scale cell transplantation experiments, leukemias were generated from single LPCs isolated from heterogeneous primary T-ALL samples. This process of single cell cloning effectively created a homogenous background in which additional mutational events could be readily identified and directly associated with cellular phenotype. This large-scale screen allowed us to answer fundamental questions regarding the role that tumor cell heterogeneity has in cancer progression at the single cell level. First, we found that continued clonal evolution reduced latency, increased the frequency of LPCs, and modulated chemotherapy resistance, all of which can contribute to disease progression and relapse. These processes were independently evolved in a subset of T-ALL clones, yet in others, they were co-evolved simultaneously through activation of the Akt signaling pathway. Our data suggest that multiple, parallel pathways can modulate each of these processes within a single leukemic cell. Additionally, while it is widely recognized that LPCs are required for malignancy and relapse (Clarke et al., 2006), a role for continued clonal evolution in enhancing the overall frequency of LPCs has gone largely unreported. In vivo competition experiments further suggest that mechanisms regulating LPC frequency and latency are regulated cell autonomously, without influence from secreted factors or continued juxtacrine signaling from neighboring clones. Our data also show that highly proliferative clones have the greatest fitness to regrow in a transplantation setting, which may explain, in part, why relapsed cancers are often more aggressive than primary disease.

Although we found that three of the six clones that evolved increased LPC frequency acquired Akt pathway activation, we were unable to pinpoint the precise mechanism of Akt pathway activation in zebrafish, besides a correlation with loss of pten expression, and elevated expression of ras family members and ptpn11a. In humans, the primary activator of Akt signaling is likely PTEN inactivation, which occurs in >18% of T-ALL and is associated with poor prognosis (Gutierrez et al. 2009). PTEN deletion was also acquired upon relapse in 12% of matched primary and relapse patient xenograft samples, and PTEN knock-down in a single primary human T-ALL provided a competitive growth advantage and increased engraftment potential upon xenograft transplant (Clappier et al., 2011), suggesting that PTEN loss and Akt activation plays an important role in T-ALL progression and relapse. Additionally, RAS is known to activate the PI3K/Akt signaling cascade and is activated in a subset of human T-ALL (Kawamura et al., 1999; Trinquand et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2012). Activation of the RAS pathway potently induced T-ALL in mouse models, largely though activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway (Kong et al., 2013; Shieh et al., 2013). Together, these data suggest that the RAS and PI3K/Akt pathways may be more commonly activated in T-ALL than previously thought. As suggested by our data, Akt pathway activation likely plays a critical role in human T-ALL progression by shortening T-ALL latency and enhancing the overall frequency of LPCs contained within the leukemia, both of which would provide a selective advantage to clones during disease progression and relapse. Importantly, we observed that Akt signaling synergized with both the Myc and intra-cellular notch1a oncogenes to drive T-ALL progression in the zebrafish models, suggesting that the Akt pathway likely collaborates with a variety of oncogenic drivers to enhance LPC frequency in T-ALL. Finally, transgenic epistasis experiments showed that Myc stabilization reduced T-ALL latency while mTORC1 acts downstream of pAkt to regulate LPC frequency. Although it is well known that mTORC1 regulates normal hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and has prominent roles in leukemia initiation (Kalaitzidis et al., 2012), a role for mTORC1 in regulating the frequency of LPCs in T-ALL is largely unkown.

Acquired Akt pathway activation also rendered clonally-evolved T-ALL cells insensitive to dexamethasone, a glucocorticoid used as a front-line therapy for T-ALL. Remarkably, inhibition of Akt or PI3K could restore sensitivity to dexamethasone-induced killing and specifically targets the LPC fraction. While Akt pathway activation is known to render T-ALL cells resistant to dexamethasone (Beesley et al., 2009; Chiarini et al., 2010; Piovan et al., 2013), our data demonstrate that T-ALL clones can also spontaneously develop chemotherapy resistance without any prior exposure to drug. Thus, Akt pathway activation is likely stochastically activated in a subset of clones following continued clonal evolution and selected within untreated, primary leukemias based on its role in elevating LPC frequency and overall growth. Sadly, patients with clones that have Akt pathway activation would likely already contain cells that are insensitive to dexamethasone therapy. As an important corollary, T-ALL clones found in patients undergoing dexamethasonse therapy likely encounter extreme selection pressure to activate the PI3K/Akt pathway in an effort to suppress responses to dexamethasone. Once the PI3K/Akt pathway is activated, T-ALL cells become simultaneously resistant to therapy, have shortened latency, and have increased numbers of LPCs capable of driving relapse. While MK2206 has met with limited success in clinical trials for leukemia and solid tumors due to toxicity issues (Yap et al., 2011), our data provide a strong rationale for utilizing PI3K/Akt inhibitors in pre-clinical testing against T-ALL in combination with glucocorticoids, providing powerful combinatory therapies that will eradicate T-ALL cells, reduce the overall numbers of LPCs, and decrease T-ALL growth.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animal use, creation of transgenic zebrafish and T-ALL transplantation

Zebrafish studies were approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital Subcommittee on Research Animal Care, under protocol #2011N000127. CG1-strain zebrafish were used exclusively for these studies. Creation of mosaic transgenic animals and DNA constructs have been described previously (Blackburn et al., 2012) and are fully described in Supplemental Experimental Procedures. Because primary Myc-induced zebrafish T-ALL contains, on average, less than 1 LPC per 100 FACS isolated cells (Smith et al., 2010), monoclonal T-ALL could be generated from animals engrafted with 10 T-ALL cells, and in some cases 100 cells. The statistical likelihood of generating T-ALL from a single LPC by 10- or 100-cell transplants is noted for each clone in Table S1. Monoclonality was verified by detection of a single tcrβ rearrangement (Blackburn et al., 2012, Table S1) and in some cases by array CGH. Serial passaging of monoclonal T-ALL was accomplished using similar protocols as outlined previously (Blackburn et al., 2011). Kaplan Meier analyses were performed using a Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test in GraphPad Prism. Analyses of limiting dilution cell transplantation data and calculation of 95% confidence intervals were completed using Extreme Limiting Dilution Analysis software (Hu and Smyth, 2009). All other statistical calculations were completed using Student’s T-test, except where noted.

Chemical treatment of T-ALL cells and T-ALL bearing zebrafish

Human T-ALL cell lines were cultured as described (Blackburn et al., 2012) and drug treated as outlined in Supplemental Experimental Procedures. Ex vivo drug treatment of zebrafish T-ALL cells was completed using zebrafish kidney stromal (ZKS) conditioned media as described in Supplemental Experimental Procedures. For in vivo drug treatment, drugs were mixed in zebrafish system water and animals submersed in drug containing water at the doses and times described in the main text. Additional experimental conditions are described within the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Immunohistochemistry, Western blot analysis, EDU Staining, realtime RT-PCR and genomic DNA sequencing

Paraffin embedding, sectioning and immunohistochemical analysis of zebrafish tissue were performed essentially as described (Langenau et al., 2003). Antibodies and dilutions used for Western blot analysis are noted in Supplemental Experimental Procedures. EDU staining was performed using the Click-iT Alexa Fluor 647 imaging kit (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Realtime RT-PCR and sequencing of genomic DNA was performed as previously described (Blackburn et al. 2012), utilizing gene specific primers (Supplemental Experimental Procedures). Gene expression was normalized to ef1-α and β-actin controls to obtain relative transcript levels using the 2−ΔΔCT method. For all analyses, cells were isolated from fish with >50% T-ALL burden.

Accession numbers generated in this study

The aCGH data discussed in this publication have been deposited in NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE54482 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE54482).

Supplementary Material

SIGNFICANCE.

Uncovering the consequences of acquired mutations resulting from clonal evolution will be critical for understanding tumor progression and relapse. Our findings demonstrate that a subset of single T-ALL cells spontaneously acquired Akt pathway activation, which decreased latency, increased the frequency of relapse-driving leukemia-propagating cells (LPCs), and mediated resistance to chemotherapy in the absence of prior drug exposure. These data suggest that diagnosis clones can stochastically acquire mutations necessary to survive treatment and drive relapse even before a patient recieves therapy, with acquired mutations being independently selected based on important cancer phenotypes. Our work also identifies combination therapies that utilize dexamethasone and Akt inhibitor can kill LPCs in a subset of refractory and relapse T-ALL.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Spontaneous and continued clonal evolution occurs within single T-ALL cells

Clonal evolution enhances LPC frequency, growth and therapy resistance

Clonal evolution can activate the Akt/mTORC1 pathway to increase LPC frequency

Akt inhibitors sensitize LPCs to dexamethasone-induced killing

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Ravi Mylvaganam for expert advice and assistance with FACS, and Eric Stone and Marcellino Pena for excellent zebrafish husbandry. We thank Dr. Alejandro Gutierrez and Dr. Hui Feng for reagents and technical advice, and Dr. Donna Neuberg for assistance with statistical analyses. J.S.B. is supported by the Alex Lemonade Stand Foundation Young Investigator Award, the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Special Fellow Award, the Massachusetts General Hospital Toteson Fund for Medical Discovery Post-doctoral Fellowship, and NIH grant 1K99CA181500-01. F.E.M. is supported by NIH grant F32DK098875. D.M.L. received funding for this project from the American Cancer Society, the Leukemia Research Foundation, the Harvard Stem Cell Institute, the MGH Goodman Fellowship, and the Alex Lemonade Stand Foundation Innovation Grant.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Almendro V, Marusyk A, Polyak K. Cellular heterogeneity and molecular evolution in cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2013;8:277–302. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-020712-163923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson K, Lutz C, van Delft FW, Bateman CM, Guo Y, Colman SM, Kempski H, Moorman AV, Titley I, Swansbury J, et al. Genetic variegation of clonal architecture and propagating cells in leukaemia. Nature. 2011;469:356–361. doi: 10.1038/nature09650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio S, Caldas C. The Implications of Clonal Genome Evolution for Cancer Medicine. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;368:842–851. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1204892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beesley AH, Firth MJ, Ford J, Weller RE, Freitas JR, Perera KU, Kees UR. Glucocorticoid resistance in T-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukaemia is associated with a proliferative metabolism. Br. J. Cancer. 2009;100:1926–1936. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn JS, Liu S, Langenau DM. Quantifying the frequency of tumor-propagating cells using limiting dilution cell transplantation in syngeneic zebrafish. J Vis Exp. 2011:e2790. doi: 10.3791/2790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn JS, Liu S, Raiser DM, Martinez SA, Feng H, Meeker ND, Gentry J, Neuberg D, Look AT, Ramaswamy S, et al. Notch signaling expands a pre-malignant pool of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia clones without affecting leukemia-propagating cell frequency. Leukemia. 2012;26:2069–2078. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet M, Loosveld M, Montpellier B, Navarro J-M, Quilichini B, Picard C, Di Cristofaro J, Bagnis C, Fossat C, Hernandez L, et al. Posttranscriptional deregulation of MYC via PTEN constitutes a major alternative pathway of MYC activation in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2011;117:6650–6659. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-336842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan SM, Weng AP, Tibshirani R, Aster JC, Utz PJ. Notch signals positively regulate activity of the mTOR pathway in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2007;110:278–286. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-039883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiarini F, Grimaldi C, Ricci F, Tazzari PL, Evangelisti C, Ognibene A, Battistelli M, Falcieri E, Melchionda F, Pession A, et al. Activity of the novel dual phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor NVP-BEZ235 against T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8097–8107. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clappier E, Gerby B, Sigaux F, Delord M, Touzri F, Hernandez L, Ballerini P, Baruchel A, Pflumio F, Soulier J. Clonal selection in xenografted human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia recapitulates gain of malignancy at relapse. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208:653–661. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke MF, Dick JE, Dirks PB, Eaves CJ, Jamieson CHM, Jones DL, Visvader J, Weissman IL, Wahl GM. Cancer stem cells--perspectives on current status and future directions: AACR Workshop on cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9339–9344. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L, Ley TJ, Larson DE, Miller CA, Koboldt DC, Welch JS, Ritchey JK, Young MA, Lamprecht T, McLellan MD, et al. Clonal evolution in relapsed acute myeloid leukaemia revealed by whole-genome sequencing. Nature. 2012;481:506–510. doi: 10.1038/nature10738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einsiedel HG, von Stackelberg A, Hartmann R, Fengler R, Schrappe M, Janka-Schaub G, Mann G, Hählen K, Göbel U, Klingebiel T, et al. Long-term outcome in children with relapsed ALL by risk-stratified salvage therapy: results of trial acute lymphoblastic leukemia-relapse study of the Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster Group 87. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23:7942–7950. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlinger M, Swanton C. How Darwinian models inform therapeutic failure initiated by clonal heterogeneity in cancer medicine. Br. J. Cancer. 2010;103:1139–1143. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlinger M, Rowan AJ, Horswell S, Larkin J, Endesfelder D, Gronroos E, Martinez P, Matthews N, Stewart A, Tarpey P, et al. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:883–892. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez A, Sanda T, Grebliunaite R, Carracedo A, Salmena L, Ahn Y, Dahlberg S, Neuberg D, Moreau LA, Winter SS, et al. High frequency of PTEN, PI3K, and AKT abnormalities in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2009;114:647–650. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-206722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez A, Grebliunaite R, Feng H, Kozakewich E, Zhu S, Guo F, Payne E, Mansour M, Dahlberg SE, Neuberg DS, et al. Pten mediates Myc oncogene dependence in a conditional zebrafish model of T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208:1595–1603. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Smyth GK. ELDA: extreme limiting dilution analysis for comparing depleted and enriched populations in stem cell and other assays. J. Immunol. Methods. 2009;347:70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Vogt PK. Constitutively active Rheb induces oncogenic transformation. Oncogene. 2008;27:5729–5740. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaitzidis D, Sykes SM, Wang Z, Punt N, Tang Y, Ragu C, Sinha AU, Lane SW, Souza AL, Clish CB, et al. mTOR complex 1 plays critical roles in hematopoiesis and Pten-loss-evoked leukemogenesis. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:429–439. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura M, Ohnishi H, Guo SX, Sheng XM, Minegishi M, Hanada R, Horibe K, Hongo T, Kaneko Y, Bessho F, et al. Alterations of the p53, p21, p16, p15 and RAS genes in childhood T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk. Res. 1999;23:115–126. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(98)00146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King B, Trimarchi T, Reavie L, Xu L, Mullenders J, Ntziachristos P, Aranda-Orgilles B, Perez-Garcia A, Shi J, Vakoc C, et al. The Ubiquitin Ligase FBXW7 Modulates Leukemia-Initiating Cell Activity by Regulating MYC Stability. Cell. 2013;153:1552–1566. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong G, Du J, Liu Y, Meline B, Chang Y-I, Ranheim EA, Wang J, Zhang J. Notch1 gene mutations target KRAS G12D-expressing CD8+ cells and contribute to their leukemogenic transformation. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:37368. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.475376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau DA, Carter SL, Stojanov P, McKenna A, Stevenson K, Lawrence MS, Sougnez C, Stewart C, Sivachenko A, Wang L, et al. Evolution and impact of subclonal mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cell. 2013;152:714–726. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenau DM, Traver D, Ferrando AA, Kutok JL, Aster JC, Kanki JP, Lin S, Prochownik E, Trede NS, Zon LI, et al. Myc-induced T cell leukemia in transgenic zebrafish. Science. 2003;299:887–890. doi: 10.1126/science.1080280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenau DM, Feng H, Berghmans S, Kanki JP, Kutok JL, Look AT. Cre/lox-regulated transgenic zebrafish model with conditional myc-induced T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:6068–6073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408708102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack MP, Young LF, Vasudevan S, de Graaf CA, Codrington R, Rabbitts TH, Jane SM, Curtis DJ. The Lmo2 oncogene initiates leukemia in mice by inducing thymocyte self-renewal. Science. 2010;327:879–883. doi: 10.1126/science.1182378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullighan CG, Phillips LA, Su X, Ma J, Miller CB, Shurtleff SA, Downing JR. Genomic analysis of the clonal origins of relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science. 2008;322:1377–1380. doi: 10.1126/science.1164266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notta F, Mullighan CG, Wang JCY, Poeppl A, Doulatov S, Phillips LA, Ma J, Minden MD, Downing JR, Dick JE. Evolution of human BCR-ABL1 lymphoblastic leukaemia-initiating cells. Nature. 2011;469:362–367. doi: 10.1038/nature09733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palomero T, Lim WK, Odom DT, Sulis ML, Real PJ, Margolin A, Barnes KC, O’Neil J, Neuberg D, Weng AP, et al. NOTCH1 directly regulates c-MYC and activates a feed-forward-loop transcriptional network promoting leukemic cell growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:18261–18266. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606108103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palomero T, Sulis ML, Cortina M, Real PJ, Barnes K, Ciofani M, Caparros E, Buteau J, Brown K, Perkins SL, et al. Mutational loss of PTEN induces resistance to NOTCH1 inhibition in T-cell leukemia. Nat. Med. 2007;13:1203–1210. doi: 10.1038/nm1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piovan E, Yu J, Tosello V, Herranz D, Ambesi-Impiombato A, Da Silva AC, Sanchez-Martin M, Perez-Garcia A, Rigo I, Castillo M, et al. Direct Reversal of Glucocorticoid Resistance by AKT Inhibition in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2013;24:766–776. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pui C-H, Robison LL, Look AT. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet. 2008;371:1030–1043. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60457-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schult C, Dahlhaus M, Glass A, Fischer K, Lange S, Freund M, Junghanss C. The dual kinase inhibitor NVP-BEZ235 in combination with cytotoxic drugs exerts anti-proliferative activity towards acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:463–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shieh A, Ward AF, Donlan KL, Harding-Theobald ER, Xu J, Mullighan CG, Zhang C, Chen S-C, Su X, Downing JR, et al. Defective K-Ras oncoproteins overcome impaired effector activation to initiate leukemia in vivo. Blood. 2013;121:4884–4893. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-432252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva A, Yunes JA, Cardoso BA, Martins LR, Jotta PY, Abecasis M, Nowill AE, Leslie NR, Cardoso AA, Barata JT. PTEN posttranslational inactivation and hyperactivation of the PI3K/Akt pathway sustain primary T cell leukemia viability. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:3762–3774. doi: 10.1172/JCI34616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ACH, Raimondi AR, Salthouse CD, Ignatius MS, Blackburn JS, Mizgirev IV, Storer NY, de Jong JLO, Chen AT, Zhou Y, et al. High-throughput cell transplantation establishes that tumor-initiating cells are abundant in zebrafish T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2010;115:3296–3303. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-246488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinquand A, Tanguy-Schmidt A, Ben Abdelali R, Lambert J, Beldjord K, Lengliné E, De Gunzburg N, Payet-Bornet D, Lhermitte L, Mossafa H, et al. Toward a NOTCH1/FBXW7/RAS/PTEN-Based Oncogenetic Risk Classification of Adult T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Group for Research in Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013;31:4333–4342. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.5292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Vlierberghe P, Ferrando A. The molecular basis of T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:3398–3406. doi: 10.1172/JCI61269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yachida S, Jones S, Bozic I, Antal T, Leary R, Fu B, Kamiyama M, Hruban RH, Eshleman JR, Nowak MA, et al. Distant metastasis occurs late during the genetic evolution of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2010;467:1114–1117. doi: 10.1038/nature09515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap TA, Yan L, Patnaik A, Fearen I, Olmos D, Papadopoulos K, Baird RD, Delgado L, Taylor A, Lupinacci L, et al. First-in-man clinical trial of the oral pan-AKT inhibitor MK-2206 in patients with advanced solid tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29:4688–4695. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.5263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Ding L, Holmfeldt L, Wu G, Heatley SL, Payne-Turner D, Easton J, Chen X, Wang J, Rusch M, et al. The genetic basis of early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2012;481:157–163. doi: 10.1038/nature10725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.