Significance

Canopy trees are keystone organisms that create habitat for an enormous array of flora and fauna and dominate carbon storage in tropical forests. Determining the functional diversity of tree canopies is, therefore, critical to understanding how tropical forests are assembled and predicting ecosystem responses to environmental change. Across the megadiverse Andes-to-Amazon corridor of Peru, we discovered a large-scale nested pattern of canopy chemical assembly among thousands of trees. This nested geographic and phylogenetic pattern within and among forest communities provides a different perspective on current and future alterations to the functioning of western Amazonian forests resulting from land use and climate change.

Keywords: Amazon basin, leaf traits, biological diversity, chemical phylogeny, community assembly

Abstract

Patterns of tropical forest functional diversity express processes of ecological assembly at multiple geographic scales and aid in predicting ecological responses to environmental change. Tree canopy chemistry underpins forest functional diversity, but the interactive role of phylogeny and environment in determining the chemical traits of tropical trees is poorly known. Collecting and analyzing foliage in 2,420 canopy tree species across 19 forests in the western Amazon, we discovered (i) systematic, community-scale shifts in average canopy chemical traits along gradients of elevation and soil fertility; (ii) strong phylogenetic partitioning of structural and defense chemicals within communities independent of variation in environmental conditions; and (iii) strong environmental control on foliar phosphorus and calcium, the two rock-derived elements limiting CO2 uptake in tropical forests. These findings indicate that the chemical diversity of western Amazonian forests occurs in a regionally nested mosaic driven by long-term chemical trait adjustment of communities to large-scale environmental filters, particularly soils and climate, and is supported by phylogenetic divergence of traits essential to foliar survival under varying environmental conditions. Geographically nested patterns of forest canopy chemical traits will play a role in determining the response and functional rearrangement of western Amazonian ecosystems to changing land use and climate.

Foliage is a locus of chemical investment undertaken by plants to capture and use sunlight for carbon gain under changing environmental conditions and compete with coexisting individuals and species. Plants acquire essential chemical elements from soils, and they synthesize a wide variety of compounds in their leaves to support multiple interdependent physiological processes. Uptake of nitrogen and phosphorus plus the internal production of photosynthetic pigments, including chlorophyll and carotenoids, are required for light capture and carbon fixation in foliage (1). Soluble carbon, primarily comprised of sugars, starch, pectins, and lipids, is then synthesized to meet the energy requirements of the entire plant (2). Other macro- and micronutrients (e.g., calcium) underpin critical leaf functions, such as stomatal conductance and cell wall development. To support the carbon capture process, foliar structural compounds, such as lignin and cellulose, are synthesized to provide strength and longevity (3), and polyphenols are generated for chemical defense (4). Variation in this leaf chemical portfolio expresses multiple strategies evolved in plants to maximize fitness through growth and longevity in any given environment.

Despite our understanding of plant chemical and physiological processes, the way that environment and evolution interact to determine geographic variation in plant canopy chemistry remains a mystery. In turn, this shortfall sets a fundamental limit on our knowledge of the core determinants of functional diversity in and across ecosystems, with cascading limits on our understanding of biogeographic and biogeochemical processes. Although much research has either focused on plant functional trait differentiation among coexisting species in communities (5) or emphasized trait convergence in response to environmental filters, such as climate and soils (6), few studies have examined the interconnections between phylogeny and environment in determining functional diversity by way of canopy chemistry (7). This gap is particularly true in the tropics, where our understanding of the interplay between evolution and environmental factors is perhaps weakest because of high plant diversity and a poor understanding of plant community assembly (8). Today, we know very little about canopy chemical traits at community to biome scales in the tropics (9).

Western Amazonian forests are a case in point. The forested corridor stretching from Colombia to Bolivia and from the Andean tree line to the Amazon lowlands harbors thousands of plant species arranged in communities distributed across widely varying elevation, geologic, soil, and hydrologic conditions (10, 11). Although the general biological diversity of the region is coming into focus (12, 13), the functional diversity of the forest remains unknown. To understand the regional assembly of forest functional traits and their underlying controls in Amazonia, we must determine the degree to which canopy chemistry is environmentally filtered and phylogenetically partitioned as well as how chemical traits are organized within and among communities. If chemical traits are plastic among coexisting taxa, then biological diversity may be decoupled from functional diversity. Alternatively, if there exists strong phylogenetic organization of canopy chemical traits, then biological diversity may express functional trait diversity and vice versa. Determining the connection between functional and biological diversity may help to explain how so many species coexist within communities and how communities differ throughout the region (14).

Here, we are interested in chemical diversity among coexisting tropical canopy tree species and their evolved responses to regional environmental filters thought to limit functional trait divergence. Thus, we developed chemical trait portfolios for tree canopies spread along a 3,500-m elevation gradient stretching from lowland Amazonia to the Andean tree line in Peru (SI Methods and Tables S1 and S2). We assessed the role of taxonomy as well as within- (intraspecific) and between-species (interspecific) variations in determining community and regional chemical assembly. Our study incorporated 2,420 canopy tree species in 19 forests along the elevation gradient, and our sampling included the majority of canopy tree species known to occur in the western Amazon (11, 12). Because submontane to montane Andean forests exist primarily on younger geologic surfaces, whereas lowland forests occur on a mosaic of young to old substrates, we also considered the role of soils in mediating canopy chemical trait distributions. We asked two questions. (i) How does the canopy chemistry of western Amazonian forests vary with elevation? (ii) How much of the variation is explained by taxonomy compared with plasticity within taxa? We focused on light capture and growth traits (including N, P, and photosynthetic pigments) as well as structure and defense traits (total C, lignin, cellulose, and phenols). We also considered Ca as a key element regulating foliar metabolism and nutrient cycling in humid tropical ecosystems (15, 16), and we measured δ13C and soluble carbon as indicators of performance (17). Finally, we assessed sources of variation in leaf mass per area (LMA), a foliar structural property expressing plant investment strategies based on multiple chemical and physiological traits (18).

Results

Regional Chemical Diversity.

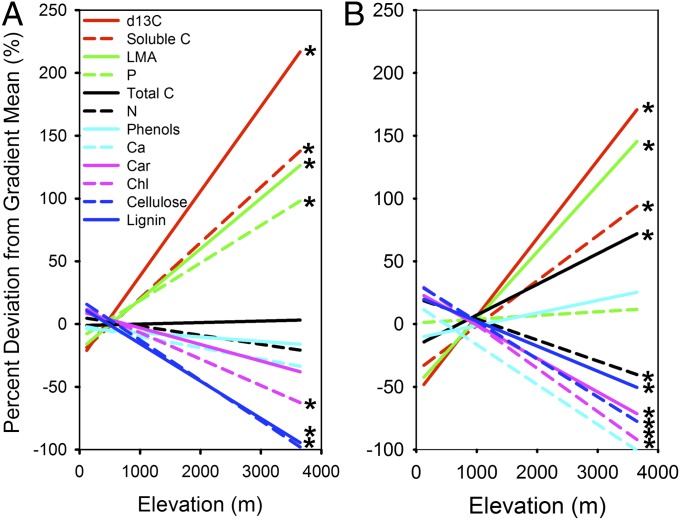

Canopy chemical traits varied widely among the thousands of trees surveyed along the Andes–Amazon elevation gradient (Table 1 and Table S3). Foliar N, P, and lignin spanned an order of magnitude in value, whereas Ca and phenols varied by two orders of magnitude. Community-scale variation in many chemical traits tracked changes in elevation (Fig. S1) and at times, was closely related to climate (Table S4). Intercomparison of elevational trends in canopy chemistry was made possible by applying a gradient normalization procedure to the data, which shows the percentage increase or decrease in a community’s average trait value relative to the gradient mean (SI Methods). By doing this normalization, elevational trends among all forests were found to differ from observed trends among high-fertility sites alone, revealing the central role of soils in determining community-level canopy chemistry in the region (Fig. 1). Most notably, foliar P and Ca concentrations on higher-fertility lowland sites were two times that measured on lower-fertility lowland sites, and soluble C concentrations were elevated in higher-fertility areas (Table 2). In contrast, total C, phenols, and lignin were suppressed in the higher-fertility sites.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for canopy foliar traits in forests along the Andes–Amazon elevation gradient in Peru

| Foliar traits | Mean (SD) | Minimum | Maximum |

| All forests (2,420 species) | |||

| δ13C (per mil) | −31.5 (1.5) | −36.2 | −25.4 |

| LMA (g m−2) | 104.09 (32.55) | 33.43 | 296.61 |

| Total C (%) | 49.4 (3.2) | 34.8 | 58.6 |

| Soluble C (%) | 43.05 (11.17) | 16.87 | 80.58 |

| Chlorophyll (mg g−1) | 7.03 (2.42) | 1.47 | 18.04 |

| Carotenoid (mg g−1) | 1.49 (0.48) | 0.40 | 5.86 |

| N (%) | 2.08 (0.67) | 0.57 | 5.54 |

| P (%) | 0.12 (0.07) | 0.03 | 0.82 |

| Ca (%) | 0.93 (0.85) | 0.02 | 7.25 |

| Phenols (mg g−1) | 104.76 (53.25) | 1.23 | 321.11 |

| Lignin (%) | 25.95 (10.00) | 2.98 | 62.15 |

| Cellulose (%) | 18.96 (5.40) | 5.98 | 43.23 |

| Higher-fertility soils (919 species) | |||

| δ13C (per mil) | −31.4 (1.6) | −35.3 | −25.4 |

| LMA (g m−2) | 98.46 (34.39) | 33.43 | 296.61 |

| Total C (%) | 47.9 (3.1) | 35.7 | 55.3 |

| Soluble C (%) | 47.38 (11.43) | 16.87 | 80.58 |

| Chlorophyll (mg g−1) | 7.61 (2.54) | 1.47 | 18.04 |

| Carotenoid (mg g−1) | 1.61 (0.49) | 0.41 | 3.42 |

| N (%) | 2.18 (0.68) | 0.63 | 5.23 |

| P (%) | 0.17 (0.08) | 0.05 | 0.82 |

| Ca (%) | 1.43 (0.92) | 0.07 | 6.38 |

| Phenols (mg g−1) | 89.94 (49.69) | 1.23 | 238.79 |

| Lignin (%) | 21.72 (8.55) | 3.89 | 54.58 |

| Cellulose (%) | 17.59 (5.08) | 5.98 | 40.00 |

The data are presented for all 19 forest sites and for a subset of 10 sites that occur on high-fertility soils (SI Methods).

Fig. 1.

Changes in average canopy foliar traits along a 3,500-m Andes to Amazon elevation gradient for (A) all sites on all soil types and (B) a subset of sites on high-fertility soils. The lines are ordinary least squares regression fits for each trait after normalization of the data to their elevation gradient mean values (site mean − gradient mean)/gradient SD (SI Methods). *Linear regression fits to foliar data that are significant at the P < 0.05 level. Car, carotenoid; Chl, chlorophyll.

Table 2.

ANOVAs comparing higher- and lower-fertility soils in Amazonian lowland forests (<300-m elevation)

| Higher fertility | Lower fertility | F | P | |

| δ13C (per mil) | −31.5 (0.3) | −31.9 (0.3) | 7.00 | 0.03 |

| LMA (g m−2) | 90.73 (9.17) | 108.95 (10.53) | 8.29 | 0.02 |

| Total C (%) | 47.09 (0.57) | 50.32 (1.17) | 26.00 | <0.01 |

| Soluble C (%) | 44.9 (1.2) | 40.7 (1.5) | 21.55 | <0.01 |

| Chl (mg g−1) | 7.93 (0.58) | 6.6 (0.79) | 8.45 | 0.02 |

| Car (mg g−1) | 1.66 (0.08) | 1.41 (0.15) | 9.55 | 0.01 |

| N (%) | 2.25 (0.05) | 1.98 (0.23) | 5.08 | 0.05 |

| P (%) | 0.18 (0.02) | 0.09 (0.02) | 47.70 | <0.01 |

| Ca (%) | 1.48 (0.16) | 0.63 (0.34) | 22.19 | <0.01 |

| Phenols (mg g−1) | 79.4 (12.94) | 114.19 (13.47) | 17.39 | <0.01 |

| Lignin (%) | 18.81 (0.99) | 19.78 (0.52) | 25.96 | <0.01 |

| Cellulose (%) | 22.23 (0.97) | 28.35 (2.25) | 4.71 | 0.06 |

Mean (± SD) of each chemical trait (mass basis) is provided along with F statistic and the significance (P value) of the comparison. Table S1 shows a listing of higher- and lower-fertility sites. Car, carotenoid; Chl, chlorophyll.

We also discovered elevation-dependent tradeoffs in canopy foliar C allocation throughout the region. Up the elevation gradient, cellulose and lignin decreased 100% relative to their region-wide mean. Soluble C increased by almost 150% with elevation (Fig. 1), and this change occurred in parallel to a nearly 200% increase in LMA. Changes in C allocation were tightly linked to mean annual temperature and precipitation along the gradient (Table S4).

We found opposing patterns for P and Ca—two rock-derived nutrients often thought to limit growth in tropical forests (16). With increasing elevation, foliar P increased 100% above the gradient mean value (Fig. 1A), but this elevational pattern disappeared after the removal of the low-fertility sites from the analysis (Fig. 1B). In contrast, mean foliar Ca concentration decreased by 100% from the Amazonian lowlands to tree line in the Andes. Foliar N declined only slightly with elevation. Additional analyses revealed decreasing P and Ca on a leaf area basis, despite the fact that LMA increased with elevation (Fig. S2 and Table S5). Finally, foliar δ13C increased by about 200% with elevation relative to its mean gradient value, and this trend occurred independent of site fertility (Fig. 1).

Taxonomic Partitioning of Chemical Traits.

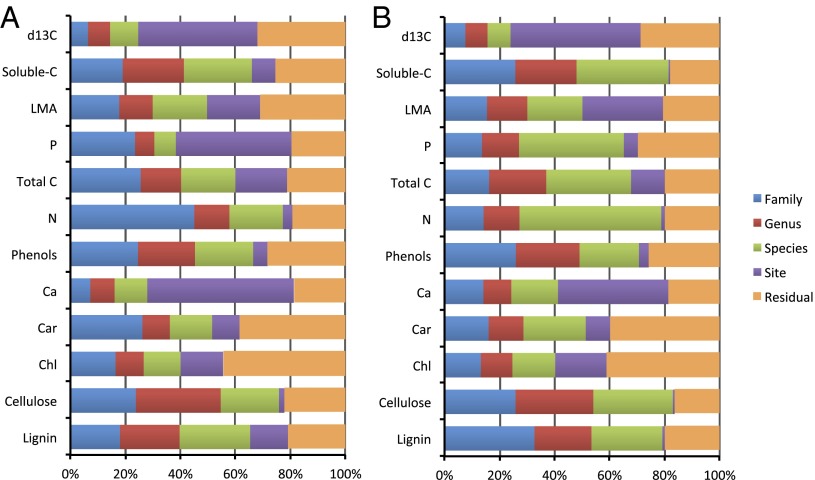

Beyond the average community-scale changes in canopy chemical traits throughout the region, we found strong taxonomic partitioning of chemical variance—a general surrogate for phylogeny (SI Methods)—within communities and across the elevation gradient (Fig. 2). Structure and defense compounds, including lignin, cellulose, and phenols as well as total and soluble C, displayed the strongest taxonomic partitioning (66–79%) in all forests. Among these chemicals, the partitioning of variance was evenly distributed at family, genus, and species levels. The strength of taxonomic partitioning increased further when considering only the higher-fertility sites (Fig. 2B). For example, taxonomy accounted for about 50% and 80% of the variation in LMA and N, respectively, in higher-fertility sites.

Fig. 2.

Partitioning of the variance for each tree canopy chemical trait into phylogenetic (family/genus/species), site, and unexplained residual components for (A) all sites on all soil types and (B) a subset of sites on high-fertility soils. The site component incorporates variation in soils, geology, topography, and tree and foliage selection among other factors. Unexplained residuals are comprised of measurement error and other nonsite-related sources of uncertainty.

Site characteristics were a relatively small contributor—less than 20%—to the explained variance in most canopy chemical traits (Fig. 2), indicating that, within any given community along the elevation gradient, phylogeny dominates over local differences in soils, microclimate, and other factors. Here, the term “site” also incorporates variation among replicates within species, including variability caused by leaf, branch, or canopy selection during our field collections. Important exceptions included δ13C, P, and Ca. Foliar δ13C displayed the weakest phylogenetic partitioning. Canopy P and Ca patterns were also dominated by site conditions, especially soils; this soil fertility effect is evidenced by the fact that phylogeny played a much stronger role in determining foliar P and Ca when only considering high-fertility sites. Regressing the model components against elevation, it is also clear that the taxonomic partitioning of most canopy chemical traits is invariant with elevation (Table S6).

Inter- vs. Intraspecific Variation.

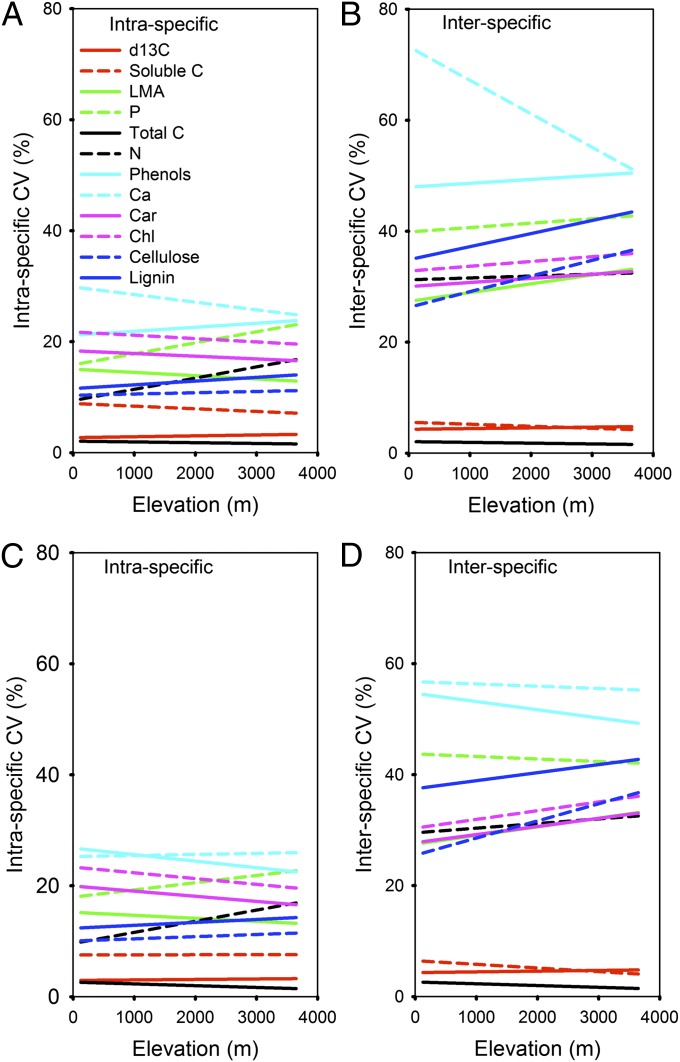

Interspecific (between-species) variation in canopy chemical traits was consistently two to three times greater than intraspecific (within-species) variation, and intraspecific variation was often very low in canopy trees at all sites (Fig. 3 and Table S7). Moreover, there were very few elevation-dependent trends in either intra- and interspecific variation (Tables S8 and S9). Maximum intraspecific variation was recorded for Ca (24–29%), phenols (21–22%), and P (16–21%). δ13C, total C, and soluble C showed extremely low intra- and interspecific variations of less than 10%.

Fig. 3.

Mean intra- and interspecific variations in tree canopy foliar traits along the Andes to Amazon elevation gradient for (A and B) all sites on all soil types and (C and D) a subset of sites on high-fertility soils (SI Methods). These regressions are computed using averaged coefficients of variation (CVs) on chemical data collected along the elevation gradient.

Discussion

Regional Chemical Diversity.

The geography of forest canopy chemical traits in the western Amazon is driven by a combination of topoedaphic variability and phylogenetic diversity. Patterns of foliar nutrients known to constrain rates of canopy CO2 fixation (e.g., P and Ca) are organized by community-scale differences in soil fertility in lowland forests and elevational changes that combine the effects of soils and climate. Foliar C allocation and defense are, however, partitioned at multiple levels of evolutionary divergence, and most Amazonian canopy trees display low within-species variation in many chemical traits. These findings suggest that the high phylogenetic diversity of the western Amazon is interconnected with high functional diversity.

One of our most unexpected results is the extremely high level of chemical diversity found among canopy tree species throughout the region (Table 1). Foliar N, phenols, lignin, cellulose, and LMA span one to two orders of magnitude in value. Leaf P and Ca cover ranges that are 27 and 363 times greater than the lowest values in the study, respectively. Such high chemical diversity exceeds the variation reported from pan-tropical synthesis studies (19, 20), reaching a degree of trait variation reported for global terrestrial and aquatic vegetation (18, 21). Despite this unprecedented breadth of canopy chemical variability among Amazonian trees, we found that canopies tend toward community-level average trait values that track changes in elevation and soil fertility as well as climate. In the lowlands, foliar P and Ca are at least two times as high in canopies on high-fertility landscapes, particularly on floodplain Inceptisols, than on low-fertility sites, such as clayey Ultisols and white sand Entisols (Table 2). On high-fertility soils, canopies have leaves with lower average LMA than canopies on low-fertility soils, and high-fertility canopies invest far less in foliar phenol and lignin production (22)—traits supporting longevity as well as pest and pathogen defense (23).

Ascending into the Andes, soils shift from the lowland mosaic of widely varying fertilities to more consistent, younger soils at the highest elevations. As a result, we found that the low-fertility sites in the lowlands mask elevation-dependent trends in canopy chemistry on the high-fertility substrates found at all elevations. When we removed the dystrophic lowland sites from the gradient analyses, we uncovered strong elevation-dependent decreases in foliar Ca that were accompanied by little change in foliar P and only a very slight decrease in foliar N (Fig. 1). This change in foliar Ca occurred in coordination with decreasing lignin and cellulose allocations and enormous increases in soluble C concentrations with increasing elevation. This previously undocumented pattern may be driven by at least three processes. First, there may exist selective pressure to reduce the storage of soluble C in lowland Amazonian canopies, while at the same time, to increase cellulose and lignin investments as a defensive strategy to minimize losses of high-energy labile carbon to herbivores (24). Herbivore pressure is much greater in the Amazonian lowlands than the Andean forests (25). Second, waxes are contributors to the soluble C pool, and we observed increased numbers of waxy-leaved plants at high elevation, perhaps as defense against cold nighttime temperatures (26). Third, Ca is critical to foliar cell wall development (27, 28), and therefore, our results suggest that reduced Ca supply at higher elevations may impede the conversion of soluble C to nonlabile, structural C compounds, such as lignin and cellulose. Each explanation is plausible, and might reinforce the other.

Regionally, we also found a large and highly significant increase in foliar δ13C with increasing elevation (Fig. 1), whereas intra- and interspecific variations in δ13C were very low and nearly constant across the gradient. These findings are indicative of leaf stomatal and/or internal resistance effects on C-isotope discrimination associated with a decrease in CO2 partial pressure at higher elevations (17). Elevation-dependent increases in δ13C also suggest increased carboxylation efficiency when there also exists an associated higher N per unit leaf area (29, 30), which did occur with increasing elevation. In turn, this finding suggests that the efficiency of C fixation is maintained, or perhaps increases at higher elevation, which would explain the relatively constant and high photosynthetic capacity recently reported along a similar Andes to Amazon elevation gradient (31–33). Such high-growth rate environments likely create the conditions under which competition and defense are the most critical factors determining how maximum productivity is achieved and maintained. If this reasoning is correct, we expect that traits associated with foliar structure and defense would be phylogenetically organized within communities, expressing limits to similarity among coexisting taxa, and a divergence in functional strategies to ensure high growth rates under varying abiotic conditions (9).

Chemical Diversity Within Tree Communities.

Within each community along the elevation gradient, we found that chemical variation between species exceeded the variation within species by two to three times. Intraspecific chemical variation was often quite low as well (Fig. 3). Moreover, we found evidence for general phylogenetic organization of multiple chemical traits operating independent of community responses to regional abiotic filters, such as soils, elevation, and climate (Fig. 2). This finding applied mainly to leaf structure and defense compounds, such as total C, lignin, cellulose, and phenols; the phylogenetic partitioning of variance among these chemicals was about evenly distributed at family, genus, and species levels. Reciprocally, we found a strongly partitioned phylogenetic pattern in soluble C. These findings are indicative of selective pressure among coexisting species to diverge in C-allocation strategy (for example, by maintaining contrasting levels of soluble C, cellulose, and lignin in the presence of host-specific herbivores) (22, 34). Complementary studies suggest that the degree of phylogenetic partitioning of defense traits is mediated by soil fertility (22, 35), although our analyses were unable to detect a clear response.

The phylogenetic partitioning of chemical variance was very weak for foliar P and Ca (Fig. 2), both of which also showed elevated intra- and interspecific plasticity (Fig. 3). Higher phenotypic plasticity in P and Ca likely reflects a need to negotiate the scarcity and patchiness of these rock-derived nutrients in many of the communities that we sampled (36). This hypothesis is strongly supported by an observed doubling of the phylogenetic attribution of variance in foliar P and Ca when we constrained the analysis to high-fertility sites alone (Fig. 2B). In contrast to P and Ca, foliar N displayed strong phylogenetic organization, which has been found in several other tropical studies (37, 38). Here, we note that the majority of the variance partitioning for nitrogen occurs at the family level, reflecting the particularly dominant role of N-fixing trees (Fabaceae) in the western Amazon.

Nested Chemical Assembly in Western Amazonia.

Across western Amazonia, we have established (i) systematic, community-scale shifts in average canopy chemical traits along regional gradients of elevation and soils; (ii) high chemical diversity among coexisting trees within communities that is driven by differences between species rather than intraspecific variation; and (iii) strong phylogenetic partitioning of foliar C fractions and defense chemicals, but not P, Ca, or δ13C, within forest communities. Together, these findings suggest the existence of a nested regional pattern that links soils and elevation to foliar nutrients and foliar nutrients to carbon and defense compound allocation and functional diversification.

At the broadest scales, environmental filtering of canopy chemistry occurs in response to rock-derived nutrient availability in soils. Foliar P and Ca track differences in soil type in the lowlands (39), whereas Ca also decreases with increasing elevation (Fig. 1). Decreasing Ca availability with elevation was observed in the work by Homeier et al. (40), but it was not seen in other tropical elevation gradients (41). Our study did not incorporate soil nutrient analyses, and therefore, we can only hypothesize that decreased Ca availability might occur from slow weathering at high elevation or transport losses of Ca to lower elevations. Whatever the case, our results strongly suggest that patterns of rock-derived nutrient concentrations in foliage reflect geologic source variation (16, 42) and not phylogeny. Our taxonomic analyses support this conclusion, because regional variation in P and Ca was clearly dominated by site, which incorporates variation in geologic substrate and soils in the absence of phylogenetic control (Fig. 2).

Regional variation in canopy P and Ca concentrations is, in turn, linked to canopy adjustments in C and defense compound allocation at the community level (Fig. 1). In the lowlands, where P varies widely, communities on low-fertility soils preferentially allocate to lignin and phenol production. This strategy supports increased leaf longevity under low-nutrient conditions and drives up leaf construction costs (35, 37, 43). With increasing elevation in the Andean Amazon, foliar Ca concentrations decline, with associated increases in soluble C and declines in lignin and cellulose allocations but increased LMA. The increased LMA may be caused by proportionally more soluble C being allocated to cuticle waxes at higher elevations, but we did not separate out waxes in our laboratory assays.

Against this regional backdrop of community-scale adjustment to rock-derived nutrient availability, climatological growth conditions are generally good, even with increasing elevation (31–33, 44), and foliar N is generally high everywhere. Such productive conditions go hand in hand with high pest and pathogen pressure on foliage (9, 25, 45). In turn, fine-scale biotic interactions between trees and pests or pathogens drive diverse strategies in defense compound and carbon allocations, which are expressed in phylogenetically organized patterns as shown. Although these underlying processes are recognized (9, 46–48), such patterns have not been reported in canopies across a wide range of environmental conditions in the humid tropics.

Ecological Implications.

The nested geographic and phylogenetic pattern of chemical assembly in forest communities of the western Amazon provides a perspective on the potential response of the region to ongoing and future changes in land use and climate. This region is a mosaic of functionally unique communities existing on specific combinations of soils and elevation, with each community undergoing chemical convergence driven largely by variation in rock-derived nutrients and climate. Land use decisions tend to be made on a similar basis of constraining abiotic filters. For example, gold mining dominates in portions of the warm lowland landscape containing nutrient- and gold-rich alluvium, including on river floodplains (49). These areas harbor communities with regionally distinct functional attributes, which we have determined, including relatively high growth and low-defense compound chemical investment. In contrast, deforestation for cattle ranching is largely focused on terra firme terraces that harbor communities on older, lower-fertility clays with trees evolved to invest more in defense and longevity (50). In the Andean submontane to montane region, forest clearing occurs for agricultural products requiring cooler temperatures (e.g., cacao and coffee). Rapid deforestation in these zones means yet other losses of communities with chemical traits unique from the lowlands. Given that these forms of land use often do not overlap geographically, each activity removes a different portion of the Amazonian functional diversity mosaic that has assembled through time.

Beyond land use effects on Amazonian functional losses, if tree canopy chemistry is adaptive to host abiotic environments over long periods of time, climate change may facilitate shifts in communities of tree species to analogous conditions under which they have functionally assembled. This potential driver of change is largely dependent on the rate of chemical trait adaptation, which may be quite slow (51). If too slow, lagged chemical trait adaptations could reinforce the process of biogeographic migration that is mediated by not only elevation and climate but also by soils that are not uniformly distributed throughout the region. The background soil template could impart both opportunity for and barriers against the movement of communities as required by the rapid velocity of climate change (52).

Finally, a clearer sense of the diversity and organization of canopy chemical traits may help us to forecast winners and losers within specific communities in response to climate change. Predicted warmer temperatures may favor species that have evolved to invest more in light capture and growth chemicals or species without the energetic burden of maintaining strong defense chemistries (53). Evidence already exists at the growth form level to support this idea: lianas (woody vines) are proliferating under warmer, drier, and/or sunnier conditions (54). To help explain observations of increasing liana cover or abundance, recent phytochemical surveys reveal that lianas are genetically predisposed to invest more in light capture and growth chemicals at the expense of structure and defense, which may support positive responses to warmer and drier conditions (19, 53). Beyond such growth form-specific responses, recent reports of highly variable rates of upward Andean migration among coexisting tree species (55, 56) hint that a phylogeny of functional traits will play a critical role in determining which species will migrate, persist, or disappear with climate change.

Methods

We collected top of canopy leaf samples from 3,856 individual trees comprised of 2,420 species (and 445 species with three to five replicates) in 19 forest sites arrayed by elevation and soil type in northern, central, and southern Peru (SI Methods and Tables S1 and S2). Our collection represents the majority of canopy tree species found throughout the western Amazon. Along the elevation gradient, mean annual precipitation ranges from 2,448 to 5,020 mm y−1. Mean annual temperature varies from 8.0 °C at the Amazonian tree line in the Andes to 26.6 °C in the warmest lowland site. Comparison of mean annual temperature from weather stations and elevation data at each site indicate a negative linear relationship (R = −0.96; P < 0.001).

Soils are consistent at higher elevations, comprising the US Department of Agriculture soil orders Inceptisol and Entisol above ∼600-m elevation (Table 1). In the lowlands (<600 m above sea level), soils vary among three broad classes: Ultisols on terra firme clay substrates, Inceptisols on inactive high-fertility floodplains of the late Holocene age, and Entisols in two locales in northern Peru. These Entisols were the well-known white sand substrates associated with very low nutrient availability (57). We analyzed the canopy data with respect to all sites as well as considering only the higher-fertility substrates. These higher-fertility sites have a history of scientific research, including soil studies (22, 58), indicating that they could be treated as nutrient-rich relative to the remaining lower-fertility sites. Our selection of the higher-fertility sites was also supported by our canopy foliar N:P values (Table S1)—N:P values below 14–16 in these sites indicate weak P limitation of primary production (42).

Only fully sunlit canopy tree species were included in this study, because many canopy chemicals and LMA are highly sensitive to vertical light gradients within forests (18). Combining sun and shade leaves confuses chemical trait comparisons within species, among species, and between communities. Leaf collections were conducted using tree-climbing techniques with strict leaf selection standards. Field cryogenetic treatment of samples, transport and preparation, and laboratory assays are described in SI Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Ackerly, K. D. Chadwick, Y. Malhi, D. Nemergut, M. Silman, P. Taylor, and A. Townsend for comments that greatly improved the manuscript. The Spectranomics project is supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1401181111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Evans JR. Photosynthesis and nitrogen relationships in leaves of C3 plants. Oecologia. 1989;78(1):9–19. doi: 10.1007/BF00377192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapin FS., III Integrated responses of plants to stress. Bioscience. 1991;41(1):29–36. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Melillo JM, Aber JD, Muratore JF. Nitrogen and lignin control of hardwood leaf litter decomposition dynamics. Ecology. 1982;63(3):621–626. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coley PD, Kursar TA, Machado J-L. Colonization of tropical rain forest leaves by epiphylls: Effects of site and host-plant leaf lifetime. Ecology. 1993;74:619–623. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tilman D. Competition and biodiversity in spatially structured habitats. Ecology. 1994;75(1):2–16. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vitousek PM, Turner DR, Kitayama K. Foliar nutrients during long-term soil development in Hawaiian montane rain forest. Ecology. 1995;76:712–720. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dahlin KM, Asner GP, Field CB. Environmental and community controls on plant canopy chemistry in a Mediterranean-type ecosystem. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(17):6895–6900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215513110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kraft NJB, Valencia R, Ackerly DD. Functional traits and niche-based tree community assembly in an Amazonian forest. Science. 2008;322(5901):580–582. doi: 10.1126/science.1160662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coley PD, Kursar TA. Ecology. On tropical forests and their pests. Science. 2014;343(6166):35–36. doi: 10.1126/science.1248110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tuomisto H, et al. Dissecting amazonian biodiversity. Science. 1995;269(5220):63–66. doi: 10.1126/science.269.5220.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gentry AH. Changes in plant community diversity and floristic composition on environmental and geographical gradients. Ann Mo Bot Gard. 1988;75(1):1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silman MR. Plant species diversity in Amazonian forests. In: Bush M, Flenly J, editors. Tropical Rain Forest Responses to Climate Change. London: Springer-Praxis; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.ter Steege H, et al. Hyperdominance in the Amazonian tree flora. Science. 2013;342(6156):1243092. doi: 10.1126/science.1243092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baraloto C, et al. Using functional traits and phylogenetic trees to examine the assembly of tropical tree communities. J Ecol. 2012;100(3):690–701. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skulan J, DePaolo DJ, Owens TL. Biological control of calcium isotopic abundances in the global calcium cycle. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1997;61(12):2505–2510. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vitousek PM, Sanford RL., Jr Nutrient cycling in moist tropical forest. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 1986;17:137–167. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu Y, Siegwolf RT, Durka W, Körner C. Phylogenetically balanced evidence for structural and carbon isotope responses in plants along elevational gradients. Oecologia. 2010;162(4):853–863. doi: 10.1007/s00442-009-1515-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poorter H, Niinemets U, Poorter L, Wright IJ, Villar R. Causes and consequences of variation in leaf mass per area (LMA): A meta-analysis. New Phytol. 2009;182(3):565–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asner GP, Martin RE. Contrasting leaf chemical traits in tropical lianas and trees: Implications for future forest composition. Ecol Lett. 2012;15(9):1001–1007. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asner GP, et al. Spectroscopy of canopy chemicals in humid tropical forests. Remote Sens Environ. 2011;115(12):3587–3598. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reich PB, Walters MB, Ellsworth DS. From tropics to tundra: Global convergence in plant functioning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(25):13730–13734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fine PV, et al. The growth-defense trade-off and habitat specialization by plants in Amazonian forests. Ecology. 2006;87(7) Suppl:S150–S162. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87[150:tgtahs]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agrawal AA. Induced responses to herbivory and increased plant performance. Science. 1998;279(5354):1201–1202. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5354.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Lacerda LD, et al. Leaf chemical characteristics affecting herbivory in a New World mangrove forest. Biotropica. 1985;18(4):350–355. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Metcalfe DB, et al. Herbivory makes major contributions to ecosystem carbon and nutrient cycling in tropical forests. Ecol Lett. 2014;17(3):324–332. doi: 10.1111/ele.12233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shepherd T, Wynne Griffiths D. The effects of stress on plant cuticular waxes. New Phytol. 2006;171(3):469–499. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Demarty M, Morvan C, Thellier M. Calcium and the cell wall. Plant Cell Environ. 1984;7(6):441–448. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taiz L, Zeiger E. Plant Physiology. 4th Ed. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Körner C, Bannister P, Mark AF. Altitudinal variation in stomatal conductance, nitrogen content and leaf anatomy in different plant life forms in New Zealand. Oecologia. 1986;69(4):577–588. doi: 10.1007/BF00410366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vitousek PM, Field CB, Matson PA. Variation in δ13C in Hawaiian Metrosideros polymorpha: A case of internal resistance? Oecologia. 1990;84(3):362–370. doi: 10.1007/BF00329760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Girardin CAJ, et al. Comparison of biomass and structure in various elevation gradients in the Andes. Plant Ecol Divers. 2013;6(3):100–110. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huasco WH, et al. Seasonal production, allocation and cycling of carbon in two mid-elevation tropical montane forest plots in the Peruvian Andes. Plant Ecol Divers. 2013;7(1-2):125–42. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Girardin CAJ, et al. Net primary productivity allocation and cycling of carbon along a tropical forest elevational transect in the Peruvian Andes. Glob Chang Biol. 2010;16(12):3176–3192. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marquis RJ. Leaf herbivores decrease fitness of a tropical plant. Science. 1984;226(4674):537–539. doi: 10.1126/science.226.4674.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Asner GP, Martin RE. Canopy phylogenetic, chemical and spectral assembly in a lowland Amazonian forest. New Phytol. 2011;189(4):999–1012. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Condit R, Engelbrecht BM, Pino D, Pérez R, Turner BL. Species distributions in response to individual soil nutrients and seasonal drought across a community of tropical trees. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(13):5064–5068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218042110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Asner G, Martin R, Suhaili A. Sources of canopy chemical and spectral diversity in lowland Bornean forest. Ecosystems. 2012;15(3):504–517. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Asner GP, Martin RE, Ford AJ, Metcalfe DJ, Liddell MJ. Leaf chemical and spectral diversity in Australian tropical forests. Ecol Appl. 2009;19(1):236–253. doi: 10.1890/08-0023.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fyllas N, et al. Basin-wide variations in foliar properties of Amazonian forest: Phylogeny, soils and climate. Biogeosciences. 2009;6(11):2677–2708. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Homeier J, Breckle S-W, Günter S, Rollenbeck RT, Leuschner C. Tree diversity, forest structure and productivity along altitudinal and topographical gradients in a species-rich ecuadorian montane rain forest. Biotropica. 2010;42(2):140–148. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kitayama K. An altitudinal transect study of the vegetation on Mount Kinabalu, Borneo. Vegetation. 1992;102(2):149–171. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Townsend AR, Cleveland CC, Asner GP, Bustamante MMC. Controls over foliar N:P ratios in tropical rain forests. Ecology. 2007;88(1):107–118. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2007)88[107:cofnri]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Poorter H, et al. Construction costs, chemical composition and payback time of high- and low-irradiance leaves. J Exp Bot. 2006;57(2):355–371. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Asner GP, et al. Landscape-scale changes in forest structure and functional traits along an Andes-to-Amazon elevation gradient. Biogeosci Discuss. 2013;10(9):15415–15454. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coley PD, Aide T. Comparison of herbivory and plant defenses in temperate and tropical broad-leaved forests. In: Price PW, Lewinsohn TM, Fernandes GW, Benson WW, editors. Plant–Animal Interaction: Evolutionary Ecology in Tropical and Temperate Regions. New York: Wiley; 1991. pp. 5–49. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Janzen DH. Herbivores and the number of tree species in tropical forests. Am Nat. 1970;104(940):501–528. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Coley PD. Herbivory and defensive characteristics of tree species in a lowland tropical forest. Ecol Monogr. 1983;53(2):209–234. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Coley PD, Barone JA. Herbivory and plant defenses in tropical forests. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 1996;27:305–335. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Asner GP, Llactayo W, Tupayachi R, Luna ER. Elevated rates of gold mining in the Amazon revealed through high-resolution monitoring. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(46):18454–18459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318271110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oliveira PJC, et al. Land-use allocation protects the Peruvian Amazon. Science. 2007;317(5842):1233–1236. doi: 10.1126/science.1146324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martin RE, Asner GP, Sack L. Genetic variation in leaf pigment, optical and photosynthetic function among diverse phenotypes of Metrosideros polymorpha grown in a common garden. Oecologia. 2007;151(3):387–400. doi: 10.1007/s00442-006-0604-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Loarie SR, et al. The velocity of climate change. Nature. 2009;462(7276):1052–1055. doi: 10.1038/nature08649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gornish ES, Prather CM. 2014. Foliar functional traits that predict plant biomass response to warming. J Veg Sci, 10.1111/jvs.12150.

- 54.Schnitzer SA, Bongers F. Increasing liana abundance and biomass in tropical forests: Emerging patterns and putative mechanisms. Ecol Lett. 2011;14(4):397–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Feeley KJ, et al. Upslope migration of Andean trees. J Biogeogr. 2011;38:783–791. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Feeley KJ, Davies SJ, Perez R, Hubbell SP, Foster RB. Directional changes in the species composition of a tropical forest. Ecology. 2011;92(4):871–882. doi: 10.1890/10-0724.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fine PVA, Mesones I, Coley PD. Herbivores promote habitat specialization by trees in Amazonian forests. Science. 2004;305(5684):663–665. doi: 10.1126/science.1098982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Quesada C, et al. Regional and large-scale patterns in Amazon forest structure and function are mediated by variations in soil physical and chemical properties. Biogeosciences. 2009;6(2):3993–4057. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.