Kusaba et al. provide additional evidence using genetic lineage analysis that epithelial cell dedifferentiation is responsible for repair of proximal tubules after injury in mouse (1). These data challenge the hypothesis of the implication of scattered stem cells in such a process or highlight a potential distinction between rodent and human. To substantiate their conclusion, the authors evaluated the expression of stem/progenitor (S/P) markers among which is CD133 (prominin-1), a cell surface antigen whose value in identifying S/P cells in various organs and neoplastic tissues is the subject of intense investigations. Beside S/P cells, it is documented that CD133 is expressed at the apical membrane of polarized cells found in numerous mouse and human terminally differentiated epithelia, notably kidney proximal tubules (2, 3) (see below). Kusaba et al. (1) surprisingly did not investigate the actual status of the CD133 protein, but instead let their work rely solely on PCR. However, the detection of CD133 transcripts, which may appear as different splice variants, is not necessarily correlated with the expression of its protein product (4). Moreover, the forward primer listed in this study (1) is not specific for CD133; it therefore remains to be determined whether CD133 transcripts are up-regulated in mouse tubular epithelia after injury, and it might be interesting to dissect the expression of CD133 variants within the nephron to see if one (or several) of them is specifically associated with tubular cell repair.

Contrary to the statement of Kusaba et al. (1), anti-mouse CD133 antibodies are commercially available. In fact, the first report on CD133 described not only its cloning from mouse adult kidney cDNA library, but also the characterization of the rat 13A4 monoclonal antibody (mAb) (2). This antibody does not show the apparent S/P cell-restricted pattern of some antibodies directed against human CD133 (e.g., AC133 mAb), but is a useful tool to dissect CD133 expression in healthy or damaged murine tissues (2). In normal kidney, 13A4 mAb labels the proximal straight tubules visualized with either a fluorophore-coupled lectin Lotus tetragonolobus agglutinin (LTA) or aquaporin-1 (AQP-1) staining. However, the morphologically defined proximal convoluted tubules seem devoid of 13A4 immunoreactivity (Fig. 1). An up-regulation of murine CD133 in dedifferentiating renal cells needs to be further documented. Although the function of CD133 is unknown, its impact on injury-induced dedifferentiation and repair may be evaluated using the CD133-null mouse line, as demonstrated in the hematopoietic system after myelotoxic stress (5).

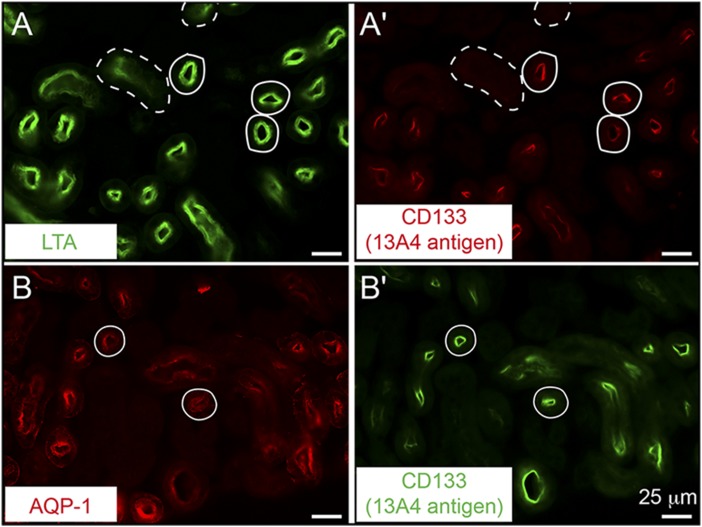

Fig. 1.

(A and B) CD133 is detected at the apical membrane of polarized cells found in proximal tubules of adult mouse. Cryosections of kidney tissues were double-labeled for either FITC-conjugated LTA (A, green) or AQP-1 (B, red) with CD133 using mAb 13A4 (A′, red; B′, green). Solid lines indicate double-positive proximal straight tubules and dashed lines delineate proximal convoluted tubules. Note that CD133 detection is restricted to the apical plasma membrane.

The abundant expression of CD133 in the healthy kidney questions whether CD133 is solely a marker of rare multipotent renal S/P cells. In other tissues, particularly glandular organs, such as liver, pancreas, and salivary glands, CD133 is physiologically expressed in ductal epithelia (intercalated ducts), which are proposed to host cells with dedifferentiation capacities, and hence, might highlight facultative stem cells acting during the regeneration. The increased CD133 expression upon epimorphic regeneration of the spinal cord of axolotl is consistent with such a role. Irrespective of the regeneration mechanism, CD133 seems to emerge as a pan stem and facultative stem cell marker with a clinical value for regenerative medicine.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Kusaba T, Lalli M, Kramann R, Kobayashi A, Humphreys BD. Differentiated kidney epithelial cells repair injured proximal tubule. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(4):1527–1532. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310653110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weigmann A, Corbeil D, Hellwig A, Huttner WB. Prominin, a novel microvilli-specific polytopic membrane protein of the apical surface of epithelial cells, is targeted to plasmalemmal protrusions of non-epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(23):12425–12430. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Florek M, et al. Prominin-1/CD133, a neural and hematopoietic stem cell marker, is expressed in adult human differentiated cells and certain types of kidney cancer. Cell Tissue Res. 2005;319(1):15–26. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-1018-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fargeas CA, et al. Identification of novel Prominin-1/CD133 splice variants with alternative C-termini and their expression in epididymis and testis. J Cell Sci. 2004;117(Pt 18):4301–4311. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arndt K, et al. CD133 is a modifier of hematopoietic progenitor frequencies but is dispensable for the maintenance of mouse hematopoietic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(14):5582–5587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215438110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]