Abstract

Objective

This study sought to explore the perceived influence of narrative medicine training on clinical skill development of fourth-year medical students, focusing on competencies mandated by ACGME and the RCPSC in areas of communication, collaboration, and professionalism.

Methods

Using grounded-theory, three methods of data collection were used to query twelve medical students participating in a one-month narrative medicine elective regarding the process of training and the influence on clinical skills. Iterative thematic analysis and data triangulation occurred.

Results

Response rate was 91% (survey), 50% (focus group) and 25% (follow-up). Five major findings emerged. Students perceive that they: develop and improve specific communication skills; enhance their capacity to collaborate, empathize, and be patient-centered; develop personally and professionally through reflection. They report that the pedagogical approach used in narrative training is critical to its dividends but misunderstood and perceived as counter-culture.

Conclusion/Practice implications

Participating medical students reported that they perceived narrative medicine to be an important, effective, but counter-culture means of enhancing communication, collaboration, and professional development. The authors contend that these skills are integral to medical practice, consistent with core competencies mandated by the ACGME/RCPSC, and difficult to teach. Future research must explore sequelae of training on actual clinical performance.

Keywords: Medical education, Narrative medicine, Communication, Physician/patient relationship, Medical humanities, Qualitative research, Values/attitudes, Competencies

1. Introduction

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) of the United States and the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (RCPSC-CanMEDS) have created an institutional mandate across North America to achieve competency in such areas as communication, collaboration, and professionalism [1–3]. Medical educators and students recognize that the formal medical school curriculum, at least in its traditional form, cannot on its own convey to students these essential skills [4–8]. Intuitively, development of these ACGME/CanMED competencies requires training both in medical expertise as well as in interpersonal, ethical, interpretive, and reflective capacities. The informal and hidden curricula, established in the literature to be one of the most powerful influences on student learning, may help teach some of these capacities [9–12]. Unfortunately, these curricula may also diminish students’ empathy, promote cynicism, and enable moral stagnation or erosion [12–22]. Currently, many medical schools rely on role-modeling, mentoring, and clinical simulations to convey and provide practice in ACGME/CanMED competencies [11,23–26]. However, these methods may create a false sense of measurement when applied to nuanced, context-based behaviors, and may encourage students to ‘perform’ exterior actions rather than function through critically examined internal attitudes [12,19,25,27–34]. There remains a need for a dependable means of training and assessing skills within the ACGME- and CanMEDS-mandated domains of medical practice.

The study of the humanities — literature, creative writing, history, philosophy, visual arts, and anthropology — has emerged in medical training as a means of conveying skill in the interpretive, relational, and reflective areas otherwise hard to teach. Numerous innovative programs have been described in the past two decades [14–17,35–41]. Included among the teaching methods to emerge is the field of narrative medicine. Narrative medicine is an offspring of literature-and-medicine and patient-centered care, defined by Charon as “medicine practiced with. . . narrative skills of recognizing, absorbing, interpreting, and being moved by the stories of illness.” [42] Narrative medicine uses an interdisciplinary, process-based approach to examine suffering, illness, disability, personhood, therapeutic relationships, and meaning in health care. Narrative medicine methods have demonstrated improvements in team cohesion and perception of others’ perspectives while decreasing burn-out and compassion fatigue [43–45].

Although there has been a rapid uptake of narrative medicine and reflective writing teaching methods in several US and Canadian medical schools, there is no clear statement available from learners themselves regarding the utility of the methods or the changes experienced as a result of the training. The importance of this deficit is revealed in the recent review by Shapiro et al. which indicates that many educational initiatives rooted in the humanities are limited in their capacity to succeed due to significant resistance posed by both students and faculty [46].

This study sought to explore the perceived influence of narrative medicine training on clinical skill development for medical students who were within months of starting internship. Using qualitative methods rooted in grounded theory [47], we asked students to report the perceived effectiveness of training in several categories of interest, focusing on those capacities that are singled out by ACGME and CanMEDS as critical to effective professional work. Specifically, we aimed to understand how medical students participating in a one-month narrative medicine elective during their fourth year of medical school would perceive its influence on their ability to communicate with patients and colleagues, to collaborate with patients and health care team members, and to develop professionally. Perhaps most importantly, we provided students with opportunities to reflect openly on unintended or unexpected consequences of their experience.

2. Methods

2.1. Narrative training method

The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University (P&S) offers an intensive month-long narrative medicine elective for fourth-year students. Twelve students (10 P&S students and 2 from outside P and S) enrolled in the elective. The students had completed undergraduate degrees in science (6), English (2), Sociology (1), History (1), Literature (1) and Economics (1). They had successfully applied for residencies in orthopedic surgery (3), emergency medicine (1), internal medicine (3), obstetrics/gynecology (1), radiology (1), primary care (1), pediatric medicine (1), and psychiatry (2). Six faculty members trained in narrative medicine used assigned and in-class readings (poems, fiction, non-fiction, doctors’ accounts of practice, and/or illness narratives) to invite small-group reflection, serve as a foundation for writing exercises, and foster discussion about aspects of illness or care (Table 1). Students were often invited to do in-class writing in response to a text and related prompt and to read aloud what they wrote. Sessions took place at the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University and were confidential, process-oriented, and collegial. Grades (Honors/Pass/Fail) were assigned based on participation and written work. No additional clinical work was required of the students during the month.

Table 1.

Summary of narrative medicine elective.

| Course description | Instructors | Use of class time | Sample course material +/− writing prompt | Hour/week |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Close reading of contemporary fiction novels | R.C. (internist and literary critic) | Close reading and discussion of novels | “So long, see you tomorrow” by William Maxwell | 2 |

| Affective dimensions of practice as experienced by patients and providers | J.A. (psychiatrist) | Discussion of assigned readings, reflective writing exercise and small group discussion of clinical work/writing | “The Ship of Death” by Lawrence Writing exercise: the doctors fear and the patient's fear | 2 |

| Fiction writing workshop | N.H. (novelist and writing teacher) W.M. (M.F.A. candidate) |

Workshop method for discussion of two student creative writing assignments; discussion of assigned readings | “Everything that Rises Must Converge” by Flannery O'Connor “The Beginnings of Grief” by Adam Haslett Personal creative writing submissions |

4 |

| Reflections on critical junctures in the formation of the doctor-self | S.A. (ob/gyn) K.S. (trauma-focused psychotherapist) |

Close reading and discussion of assigned and in-class readings, 3–5 min reflective writing to a prompt followed by discussion of writing/clinical work | Excerpts from “The Wounded Storyteller” by Arthur Frank with request to write reflectively on different illness narratives participants had witnessed; excerpts from “The things we carried” by Tim O'Brien with writing prompt: “How to tell a true medical story” | 2 |

2.2. Data collection

Study procedures were approved (IRB # AAAI1336, date: 03/31/2011, revision 10/06/12). Study methodology was rooted in grounded theory. Three methods were used to collect reflections from students regarding the process and influence of narrative medicine training on clinical skill development. Anonymous surveys composed of open-ended questions were given each week for four weeks in one of the seminars (Table 2). A focus group, conducted by an impartial facilitator trained in ethnographic methods, was held on the final day of the elective to collect students’ reflections of their experiences over the course of the month and to elaborate on findings from the surveys. Focus group questions were constructed based on a review of survey responses (Table 3). Participants were informed that the session would be audio-taped, with comments de-identified and tracked using numeric assignment. Finally, with IRB approval, the research team queried participants one and a half years following the elective. The team circulated two open-ended questions (Table 4) to the students – now residents – by email, with instructions to send responses to a member of the research team who had not had personal contact with the students. Responses were de-identified and distributed to the rest of the research team for thematic analysis. Completion of, and participation in, all methods was voluntary and independent of grading. All participants provided informed consent.

Table 2.

Questionnaire.

| 1. What was it like responding to this prompt? |

| 2. How can you imagine this session as influencing your capacity to |

| a. Respond to patients? |

| b. Relate to your peers? |

| 3. Define ‘a good communicator’. Rate yourself according to this definition, and explain how this session did or did not enable you to get closer to that definition. |

Table 3.

Focus group guide.

| 1. What are your overall impressions of the month? |

| 2. List/Identify skills or tools that you have gained that have already been or will be helpful to you (a) personally (b) professionally |

| 3. Is there an instance or moment or particular session that these things clicked for you, and if so, can you describe that moment? |

| 4. You've been asked every week whether this elective has been helping you relate to your peers–overall, what do you think? Please explain. |

| 5. With respect to your existing medical school curriculum, what about this elective was unique? What was redundant? |

| 6. Given your experience of this elective, if someone from another school asked you why courses like this are part of your curriculum, what would you say? |

| 7. How would you describe the purpose of NM in medical education? |

| 8. What is the reputation of NM as a field/concept in medical school – what reactions or comments do you hear amongst your peers? |

| 9. What is the reputation of this particular elective? |

| 10. What do you think is missing or could be better within this elective? |

| 11. What do you think is missing or could be better about the role of NM in your overall curriculum? |

| 12. Does anyone have additional thoughts or comments that they want to share? |

Table 4.

Follow-up questions posed to students 1 1/2 years after elective.

| 1. Please explain the extent to which narrative habits (reading, writing, awareness of story-telling in practice) continue to play a role in your life as a doctor. |

| 2. How do you think the narrative medicine elective influenced your clinical work? Please provide examples if possible. |

2.3. Data analysis

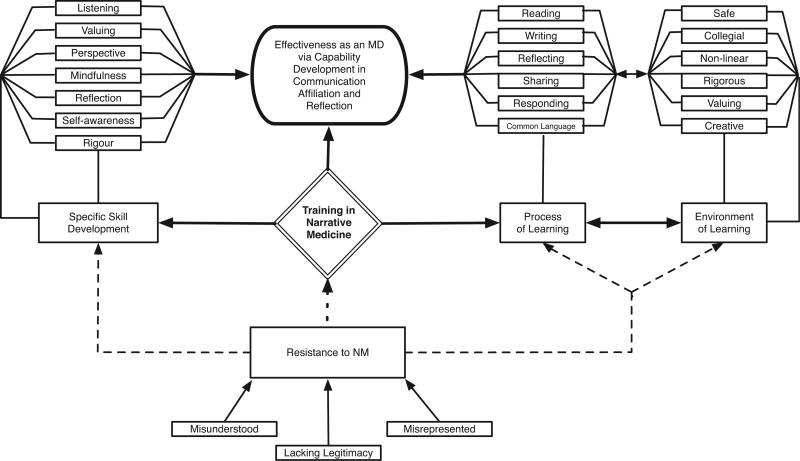

An inventory of the data was created for the surveys, the focus group, and the follow-up questions to enable thematic analyses by student (over their 4 weeks of survey responses), by question, and by method. An iterative thematic analysis of all three datasets was carried out by each of the authors independently, beginning with open coding and proceeding through focused coding. Data triangulation was achieved by referring to focus group transcripts, notes taken during the focus group, survey responses, and analyses of the focus group, survey responses, and follow-up questions with a common set of themes. Sequential member checking was performed for the results and discussion sections. Conceptual mapping was also performed (Fig. 1). Discrepancies in thematic analysis were addressed by returning to the raw data and discussing among all analysts.

Fig. 1.

This concept map was developed and used as an analytic tool to graphically depict the relationships among themes identified in the data. The direction and strength of connections is represented by arrows and by width of the adjoining lines; dotted lines represent antagonistic connections.

3. Results

3.1. Participation

There was a 91% response rate for the weekly survey (180 out of a possible 192 questions were answered). Six students elected to participate in the focus group, which ran for 1.5 h. Within the one-month period given for follow-up responses posed one and a half years after the elective, three participants (25%) responded.

Overall, students expressed that the process of training in narrative medicine was enjoyable and that the outcome was transformative. Many students described the experience as “refreshing,” “enlightening,” “revealing,” and “insightful,” yet they were quick to add that the training was “difficult” and “rigorous”. Participants in the focus group unanimously recognized tremendous value in the elective, “giving me the sense that the things that I find important — stories and people's lives — those are still valid parts of medicine,” as one commented.

We traced five emergent themes through survey and focus group data, as described below. Responses to the follow-up questions are described separately.

3.2. Specific communication skills were developed and improved

Students overwhelmingly reported an enhanced understanding of and capability in communication as a result of their narrative medicine training. According to both survey and focus group data, sessions provided practice and development of specific communication skills such as “self-awareness,. . . articulation,. . . observation,. . . patience,” and empathy toward the audience. Students volunteered that the training demonstrated the “importance of listening,” consideration for the “telling of stories,” the ability to listen and attend closely to narrative; and the ability to receive and value different perspectives. In the focus group, one student reported, “we have a large bag of tools now that we could [use to]. . . be able to understand our peers better, or our patients better.” Another student described feeling “more confident” as a communicator since the sessions helped refine existing communication skills.

Students reported experiencing the elective as enriching their interactions with patients and peers and strongly expressed their expectation that such skills would improve their practice as physicians: “being able to understand narrative will make me a better listener and a better provider” and “to listen to what a narrative is telling you about the person's situation and the way they feel about the illness. . . helps you take care of someone well.” Additionally, students’ definitions of “a good communicator” in the survey responses shifted from an emphasis on “explaining” and “listening” to “understanding,” “empathetic” explanation, “truth,” and the “purpose” and “entirety” of narrative at the concluding session. These latter responses reflect a nuanced understanding of communication: “A good communicator listens to what was said and tries not to deprive or insert the story into a simple box. This session helped stress that.”

3.3. The capacity to collaborate, empathize, and be patient-centered was enhanced as students developed increased awareness of differing perspectives

Students responding to the survey and focus group revealed a heightened awareness of different perspectives as a result of the elective. Having systematically imagined and considered the needs, background, and experience of others, they reported an expansion of their expected capacity to provide care to patients and to work with other physicians. As one student wrote, “even though my intentions are well meaning, I should stop and think about how the patient perceives me” and “be more conscious of their narratives and the context in which they are being told.” Students felt they developed an increased capacity to understand and empathize with patients and “see them as a person or narrative other than an illness.” Many emphasized the “humanity” of patients and the importance of interactions with them: “discussions like these help to reiterate that medicine is about person to person contact” and “helps to remind you that while you’re having just another day at the hospital. . . it's probably the worst day of that person's life, or one of them.”

Many students also reported enhanced awareness and understanding of their peers, and that narrative medicine training “will help to recognize chaos narratives of over-stressed, over-worked peers.” Several responses conveyed a sense of identification and affiliation with one another, and that a session “reconfirmed that we are all similar and prone to the same mistakes. Therefore, I should listen, help others see mistakes, and learn from each other's mistakes (no judgment).”

The applicability of sessions to interactions with other physicians was also reported, although not as frequently: “we also have to see our colleagues as more than, you know, your consulting nephrologist. . . I mean, that's a person as well, and how you interact with them is important. . . [W]e had a lot of time to do that.”

3.4. The opportunity to reflect on self and the practice of medicine was valued and felt to be important for personal and professional development

According to both survey and focus group data, students reported strongly valuing the opportunities presented throughout the elective to “establish a pattern” of reflecting on themselves and the practice of medicine. Many reported that the training provided skills of reflection, which they felt would enable them to become better physicians and avoid burnout: “Medical school is pretty intense. . . There's so much to learn and you’re going to lose a lot of what used to be yourself. I think [narrative medicine] can allow you to hold onto some of that and bring that into your practice of medicine. . . It's really valuable.” Students also linked reflection to the ability to maintain their sense of self, which was in turn connected to their ability to provide medical care. As one student noted, “Being forced into the habit of writing more. . . is a good way to process things that you’re dealing with. . . There are a lot of tough spots in medicine where you need to. . . come to grips with something. . . Writing it out may be a good way to do that.”

3.5. The method of training for narrative medicine was necessary for the dividends

The focus group and survey data indicate that the process of teaching narrative medicine replicates the very skills it seeks to teach. Writing, reflecting, responding to prompts, listening to and sharing with peers in a collegial, non-judgmental, and open environment allowed the students, they said, to first experience narrative medicine concepts and then to develop the skills that underlie the concepts. Practicing the skills of listening to and valuing both narratives and the people who share them inside the classroom was felt to enable the same process outside the classroom (Fig. 1): “The best part of this whole month is having the chance to listen to what everyone else has to say. . . I really feel this month has taught us how to communicate with other people and how to listen to other people.”

Students in the survey and focus group referred to two characteristics of narrative training in particular: a pedagogy that relies on learning from one another through interaction and reflection, rather than rigid subscription to particular teaching content or hierarchical student-teacher relationships; and a non-competitive environment in which diverse viewpoints, experiences, and ideas are shared and valued. Several students reported that classes were most effective and enjoyable when they were “safe” and “non-competitive” and when opportunities to write, listen and respond to their peers were maximized. Almost all students were disappointed when sessions failed to maintain this approach, reporting that learning potential was “lost” when they were unable to “share [their] interpretations.”

The dividends of narrative medicine coursework were reported to be dependent on this collegial, process-oriented atmosphere: “[we learned] from us interacting with each other, from sharing our own experiences and relating to each other's experiences.” As a result of the environment and pedagogy of the sessions, students also commented on more personal transformation: “. . . because I’ve lost that fear and apprehension, I’m a much better listener when others are speaking” and, “I felt very safe in this environment. . . to take risks and be myself and that was. . . invaluable.”

3.6. Narrative medicine training is misunderstood by others and perceived as counter-culture

Students overwhelmingly described narrative medicine in positive terms such as “invaluable,” “crucial,” “necessary,” “enlightening” and “rigorous.” One student said, “I believe wholeheartedly that narrative medicine is going to make us better doctors.” This near-unanimous opinion among the group contrasted greatly with the reputation participants reported hearing from others. When asked, “What is the reputation of narrative medicine as a discipline and/or as a component of your school curriculum?,” students in the focus group described many negative stereotypes. They cited three words in particular: “fluffy,” “unnecessary,” and “touchy-feely.” As one student said, “I think all of us in being here think it's very valuable [but]. . . a lot of people think of it as fluffy – as distracting from what's really important.” Another student reported and disagreed with the opinion that “narrative medicine is [just] good medicine, and that this is what everybody does.” Instead, this student asserted that there are “actual tools that we get in narrative medicine” that enable a preferred and distinctive kind of medical practice.

The starkly different perceptions of the field, held by those who have participated versus those who have not, was presented as a hurdle narrative medicine must overcome. Some students reported that participation might “make it harder to relate to our peers” because “they haven’t had that experience, and don’t value that viewpoint.” Students reported feeling strongly that it is necessary to “clarify what this is all about,” particularly the nature and rigor of the work, and the relevance to medical practice. Focus group participants discussed ways to address the portrayal of narrative medicine within the medical education community. One suggestion was that narrative medicine training be mandatory: “It's not optional to do pathophysiology. [I’m frustrated by] the message that narrative medicine is like an extra thing that's not as critical to being a doctor. . . If there is a component that was mandatory for everyone, it would increase the legitimacy of the practice.” Another student volunteered that he had very little humanities background and was not a likely candidate for the elective, yet “I got a lot out of it, so just the fact that it's coming from someone they wouldn’t have expected might carry a little weight as well.”

3.7. Responses to follow-up questions posed 1.5 years following the narrative medicine elective

Answers to question one (Please explain the extent to which narrative habits [reading, writing, awareness of story-telling in practice] continue to play a role in your life as a doctor) suggested lack of time for reading or writing associated with regret at this lack of time and a desire to read again. Nonetheless, these junior residents identified their skill in story-telling and story-listening to be tools in the work of medicine itself. They recognized the centrality of story-telling in their daily interactions with peers, superiors, patients, and families. One found that narrative interpretive skill allowed for culturally sensitive understanding of patients. The language itself is the critical narrative element — in writing notes and communicating to and about patients. One also found increased skill in interpreting patients’ clinical history and unraveling their chief complaints.

Answers to question two (How do you think the narrative medicine elective influenced your clinical work? Please provide examples if possible) included a student who had been moved by a patient's narrative of illness, wrote a description of the encounter, and published this in a medical publication. Another found that he or she used narrative training to improve the capacity to understand patients, extend empathic care, and communicate well with patients and families and other medical providers. One thought his or her training supported the use of silence, healing touch, and to say, “I don’t know.” Another recognized that medical documentation can include social and emotional dimensions in retrospect, and another recognized the personal benefits of reading.

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1. Discussion

This project provides consensual evidence from a group of 12 fourth-year medical students about the benefits of narrative medicine training through a grounded theory approach regarding the process, content, and experiences of learning narrative medicine. What emerged from the students is a clear statement of (1) their assertion that narrative medicine training helps equip them for ACGME and CanMEDS-required competencies specific to communication, collaboration, and professional development (2) their endorsement of the goals and methods; (3) their opinion that narrative medicine is misunderstood and seen as counter-culture.

Students explicitly linked the process and content of their learning to their perceived future effectiveness as physicians. While an empirical test of this association remains for future research, its face validity is suggested by the significant overlap between the attitudes and behaviors our student participants reported gaining and those indicated throughout the literature to be necessary for high quality medical care [1–19]. These findings provide the first available support for using narrative medicine to help meet the ACGME and CANMED competencies of communicator, collaborator, and professional. This qualitative work offers a foundation from which future studies can investigate the influence of narrative medicine not only on students’ perceptions of their skills and attitudes but also on actions that arise from those skills and attitudes in practice. Responses to the follow-up questions posed one and a half years after the elective suggests that at least some medical students take into their residency the narrative skills of attentive listening, forming interpersonal contact with patients and families, clinical accuracy in medical documentation, and bearing witness to patients’ suffering. These are exactly the skills that medical educators endeavor to teach through the use of learning portfolios, medical interviewing training, cultural competence training, or mindfulness training.

Unanticipated feedback suggested that the benefits of narrative medicine training can come about only through an environment that pedagogically relies upon and practices the skills and attitudes of interest. This belief in the reciprocity between method and dividend is supported by existing literature that reports the need for humanities-based education to occur in small groups [14,17,37,48,49], to be taught by respected and sufficiently trained facilitators [12,37,50,51], and to be process-based and facilitate active learning [14,16,35,52,53]. The process and environment of learning reported to be critical in our study is akin to the educational approach designed by Paulo Friere, who reasoned that education functions either as an oppressive or freeing force. The critical pedagogy he put forward has been shown to effect behavioral change [37,54–56], and can enable medical educators to simultaneously participate in, facilitate, and evaluate the curriculum and individuals exposed to it. In the age of competency-oriented education, this feature of narrative training may provide alternatives to ‘checklist’ evaluation methods, which may be ineffective or inappropriate when applied to behavioral learning objectives [27,30,53].

Students reported that narrative medicine is resisted by those unfamiliar with it even though the intended outcomes of training are consistent with ACGME/CanMED competencies. This disconnect likely arises out of the methods used for training which are viewed as counter-culture, a problem that is common to humanities-based programs in medicine [46]. This finding strengthens existing arguments that training in behavior-oriented, non-biomedical education must be a mandatory, longitudinal component of medical training if it is to influence the process of cultural adaptation that students undergo during their immersion into the formal, informal, hidden and null curricula [10,12,14,29,35,37,39,46,48,57,58].

Limitations of this study include the small number and self-selected nature of study participants. Students’ perceptions of the attitudinal and behavior changes influenced by the narrative medicine experience, however, are valuable and represent a necessary step of assessment in this educational innovation. The broad spectrum of undergraduate background and sub-specialty choice represented by our informants underlines the acceptability of the course.

Future research is needed on larger, non-self selected groups over longer periods of time. Specifically, future research must explore whether self-reported perceptions correspond with actual changes in attitude and behavior. The capacity for such research is necessarily linked to the extent that Narrative Medicine can be incorporated into educational curriculum.

4.2. Conclusions

Results from three modes of data collection revealed that fourth-year medical students perceive narrative medicine to be a valued and effective means to enhance communication, collaboration, and professional development. These skills are integral to medical practice, consistent with core competencies mandated by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (RCPSC-CanMEDs), and difficult to teach. This method is a promising addition to the current training strategies to prepare medical students for effective performance as resident physicians and practicing clinicians. Further research and strategies to address resistance to the field by those unfamiliar with it are required.

4.3. Practice implications

Narrative Medicine is a promising addition to the current training strategies to prepare medical students for effective performance as resident physicians and practicing clinicians. The capacity for future research in this field is necessarily linked to the extent that Narrative Medicine can be incorporated into educational curriculum.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Aubrie Swan (Ph.D, M. Ed) for conducting the Focus Group and Lorelei Lingard (Ph.D), Nancy Angoff (M.D.) and Phil Gruppuso (M.D.) for editorial suggestions.

Funding

Dr. Charon's time, and a portion of Dr Dickson's time, was supported in part by National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute (K07 HLB082628).

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted (IRB # AAAI1336) and the work was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Footnotes

Other disclosures

None.

Disclaimer

None.

Previous presentations

Oral presentation of the abstract was give in April 2012 in the “Creating Spaces” component of the Canadian Conference for Medical Education (CCME) in Banff, Alberta, Canada.

References

- 1.Batalden P, Leach D, Swing S, Dreyfus H, Dreyfus S. General competencies and accreditation in graduate medical education. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21:103. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. [6/30/2011];ACGME Outcome project [Internet] [updated 2011]. Available from: http://www.acgme.org/outcome/comp/compmin.asp.

- 3.Frank J. The Can MEDS 2005 physician competency framework. The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; Ottawa: 2005. [12.2.2008]. Available from: http://rcpsc.medical.org/canmeds/CanMEDS2005/CanMEDS2005\_e.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cassell EJ. The nature of suffering and the goals of medicine. Oxford University Press; London: 2004. p. 313. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lipkin M, Putnam SM, Lazare A, et al. The medical interview. Springer Verlag; 1995. p. 643. [Google Scholar]

- 6.IOM report Improving Medical Education. Enhancing the behavioral and social science content of medical school curricula. Off J Soc Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:230–1. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halpern J. From detached concern to empathy. Oxford University Press; London: 2011. p. 192. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spiro H, Peschel E, Curnen MGM, et al. Empathy and the practice of medicine. Yale University Press; New York: 1996. p. 222. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hafferty FW, Franks R. The hidden curriculum, ethics teaching, and the structure of medical education. Acad Med. 1994;69:861–71. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199411000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hundert EM, Hafferty F, Christakis D. Characteristics of the informal curriculum and trainees’ ethical choices. Acad Med. 1996;71:624–42. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199606000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones WS, Hanson JL, Longacre JL. An intentional modeling process to teach professional behavior: students’ clinical observations of preceptors. Teach Learn Med. 2004;16:264–9. doi: 10.1207/s15328015tlm1603_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wear D, Zarconi J. Can compassion be taught? Let's ask our students. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:948–53. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0501-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hojat M, Vergare MJ, Maxwell K, Brainard G, Herrine SK, Isenberg GA, et al. The devil is in the third year: a longitudinal study of erosion of empathy in medical school. Acad Med. 2009;84:1182–91. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b17e55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bell SK, Krupat E, Fazio SB, Roberts DH, Schwartzstein RM. Longitudinal pedagogy: a successful response to the fragmentation of the third-year medical student clerkship experience. Acad Med. 2008;83:467–75. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31816bdad5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krupat E, Pelletier S, Alexander EK, Hirsh D, Ogur B, Schwartzstein R. Can changes in the principal clinical year prevent the erosion of students’ patient-centered beliefs? Acad Med. 2009;84:582–6. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819fa92d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Branch WT, Kern D, Haidet P, Weissmann P, Gracey CF, Mitchell G, et al. The patient-physician relationship. Teaching the human dimensions of care in clinical settings. J Amer Med Assoc. 2001;286:1067–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.9.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karnieli-Miller O, Vu TR, Holtman MC, Clyman SG, Inui TS. Medical students’ professionalism narratives: a window on the informal and hidden curriculum. Acad Med. 2010;85:124–33. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c42896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Branch WT. Supporting the moral development of medical students. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:503–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.06298.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White CB, Kumagai AK, Ross PT, Fantone JC. A qualitative exploration of how the conflict between the formal and informal curriculum influences student values and behaviors. Acad Med. 2009;84:597–603. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819fba36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newton BW, Barber L, Clardy J, Cleveland E, O'Sullivan P. Is there hardening of the heart during medical school? Acad Med. 2008;83:244–9. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181637837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coulehan J, Williams PC. Vanquishing virtue: the impact of medical education. Acad Med J Assoc Amer Med Coll. 2001;76:598–605. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200106000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Treadway K, Chatterjee N. Into the water – the clinical clerkships. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1190–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1100674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deveugele M, Derese A, Maesschalck SD, Willems S, Driel MV, Maeseneer JD. Teaching communication skills to medical students, a challenge in the curriculum? Patient Educ Couns. 2005;58:265–70. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kenny NP, Mann KV, MacLeod H. Role modeling in physicians’ professional formation: reconsidering an essential but untapped educational strategy. Acad Med. 2003;78:1203–10. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200312000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robins LS, White CB, Alexander GL, Gruppen LD, Grum CM. Assessing medical students awareness of and sensitivity to diverse health beliefs using a standardized patient station. Acad Med. 2001;76:76–80. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200101000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McManus IC, Vincent CA, Thom S, Kidd J. Teaching communication skills to clinical students. Brit Med J. 1993;306:1322–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6888.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wear D, Varley JD. Rituals of verification: the role of simulation in developing and evaluating empathic communication. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;71:153–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karnieli-Miller O, Taylor AC, Cottingham AH, Inui TS, Vu TR, Frankel RM. Exploring the meaning of respect in medical student education: an analysis of student narratives. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:1309–14. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1471-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pence G. Can compassion be taught? J Med Ethics. 1983;9:189–91. doi: 10.1136/jme.9.4.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hodges B. Validity and the OSCE. Med Teach. 2003;25:250–4. doi: 10.1080/01421590310001002836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benbassat J, Baumal R. What is empathy and how can it be promoted during clinical clerkships? Acad Med. 2004;79:832–9. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200409000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coulehan J. Viewpoint: today's professionalism engaging the mind but not the heart. Acad Med. 2005;80:892–8. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200510000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beaudoin C, Maheux B, Côté L, Marchais JED, Jean P, Berkson L. Clinical teachers as humanistic caregivers and educators: perceptions of senior clerks and second-year residents. Can Med Assoc J. 1998;159:765–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tervalon M, Murray-García J. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multi cultural education. J Health Care Poor U. 1998;9:117–25. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shapiro J, Lie D, Gutierrez D, Zhuang G. That never would have occurred to me: a qualitative study of medical students’ views of a cultural competence curriculum. BMC Med Educ. 2006;6:31. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-6-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dobie S. Viewpoint: reflections on a well-traveled path: self-awareness, mindful practice, and relationship-centered care as foundations for medical education. Acad Med. 2007;82:422–7. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000259374.52323.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumagai AK. A conceptual framework for the use of illness narratives in medical education. Acad Med. 2008;83:653–8. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181782e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garrison D, Lyness JM, Frank JB, Epstein RM. Qualitative analysis of medical student impressions of a narrative exercise in the third-year psychiatry clerkship. Acad Med. 2011;86:85–9. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ff7a63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Epstein RM, Hundert EM. Defining and assessing professional competence. J Amer Med Assoc. 2002;287:226–35. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hobgood C, Sawning S, Bowen J, Savage K. Teaching culturally appropriate care a review of educational models and methods. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:1288–95. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Drolet BC, Rodgers S. A comprehensive medical student wellness program–design and implementation at Vanderbilt School of Medicine. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2010;85:103–10. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c46963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Charon R. Narrative medicine. Oxford University Press; New York: 2006. p. 266. [Google Scholar]

- 43.DasGupta S, Meyer D, Calero-Breckheimer A, Costley A, Guillen S. Teaching cultural competency through narrative medicine: intersections of classroom and community. Teach Learn Med. 2006;18:14–7. doi: 10.1207/s15328015tlm1801_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. [6/30/2011];A Narrative Intervention with Oncology Professionals: Stress and Burnout Reduction through an Interdisciplinary Group Process [Internet] [updated 2010]. Available from: http://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1006&context=edissertations_sp2.

- 45.Sands SA, Stanley P, Charon R. Pediatric narrative oncology interprofessional training to promote empathy, build teams, and prevent burnout. J Supportive Oncol. 2008;6:307–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shapiro J, Coulehan J, Wear D, Montello M. Medical humanities and their discontents: definitions, critiques, and implications. Acad Med. 2009;84:192–8. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181938bca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strauss A, Corbin J. Grounded theory methodology: an overview. handbook of qualitative research. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1994. p. 643. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Branch W, Kern D, Haidet P, Weissmann P, Gracey C, Mitchell G, et al. Teaching the human dimensions of care in clinical settings. J Amer Med Assoc. 2001;286:1067. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.9.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hojat M. Ten approaches for enhancing empathy in health and human services cultures. J Health Hum Serv Adm. 2009;31:412–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Branch WT, Frankel R, Gracey CF, Haidet PM, Weissmann PF, Cantey P, et al. A good clinician and a caring person: longitudinal faculty development and the enhancement of the human dimensions of care. Acad Med. 2009;84:117–25. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181900f8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bleakley A. ‘Good’ and ‘Poor’ communication in an OSCE education or training? Med Educ. 2003;37:186–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fraser S, Greenhalgh T. Coping with complexity: educating for capability. Brit Med J. 2001;323:799–803. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7316.799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hanna M, Fins JJ. Viewpoint: power and communication why simulation training ought to be complemented by experiential and humanist learning. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2006;81:265–70. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200603000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Freire P, Shor I. A pedagogy for liberation. Bergin & Garvey; Westport CT: 1987. p. 203. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Freire P, Ramos MB, Macedo D, et al. Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum Intl Pub Group; New York: 2000. p. 183. [Google Scholar]

- 56.DasGupta S, Fornari A, Geer K, Hahn L, Kumar V, Lee HJ, et al. Medical education for social justice: Paulo Freire revisited. J Med Humanit. 2006;27:245–51. doi: 10.1007/s10912-006-9021-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Campo R. “The medical humanities,” for lack of a better term. J Amer Med Assoc. 2005;294:1009. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.9.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Friedman L. The precarious position of the medical humanities in the medical school curriculum. Acad Med. 2002;77:320–2. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200204000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]