Abstract

Diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis (DCL) is characterized by the presence of a large number of lesions at several anatomic sites (head, limbs and trunk). The lesions include papules, nodules and areas of diffuse infiltration that do not ulcerate and reveal abundant parasites on histopathological examination. DCL and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) co-infections are seldom reported. We report two cases of DCL in HIV positive patients without visceral involvement. DCL is emerging as a new opportunistic infection associated with HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

Keywords: Diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis, human immunodeficiency virus infection, opportunistic infection

INTRODUCTION

Leishmaniasis, a globally prevalent parasitic disease occurs in three forms viz. visceral, cutaneous and mucocutaneous. Although estimated to cause the ninth largest disease burden among individual infectious diseases, leishmaniasis is largely ignored in discussions of tropical disease priorities.[1]

In India, foci of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) have been reported from some pockets of Thar Desert of Rajasthan, Punjab, Himachal Pradesh and Kerala. The most affected area in Rajasthan is Bikaner district.[2,3,4] Jaipur district is considered non-endemic for Leishmania. Incidence of infections caused by Leishmania in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients is increasing throughout the world. Although visceral leishmaniasis is the most frequent form of Leishmania infection seen in HIV-infected patients, CL and HIV co-infections are also becoming frequent in these individuals.[5] These infections may be associated with multiple disseminated and atypical cutaneous lesions, which respond poorly to standard treatment and cause frequent relapses. We report two cases of diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis (DCL) because of its rarity and association with HIV infection, also because they were initially thought to be cases of histoplasmosis but later diagnosed as DCL.

CASE REPORTS

DCL with HIV infection

Case 1

This was a case report of a 50-year-old male agriculturist, diagnosed as HIV positive 1½ years back on antiretroviral therapy (ART), who presented with a 6 month history of asymptomatic skin lesions over his limbs. Physical examination revealed multiple, diffuse, non-ulcerating, papulonodular and non-itchy skin lesions of size 2-18 mm [Figure 1]. History revealed that the lesions first appeared on the feet and then over the hands. There was no history of travel to endemic areas of leishmaniasis. There was no hepatosplenomegaly and lymphadenopathy. The laboratory investigations revealed anemia hemoglobin (Hb - 8.3 g/dL). The liver function tests, renal function tests, lipid profile and blood sugar were within the normal limits. The platelet count was 2 lacs/μL and the total leucocyte count was 5,100/μL.

Figure 1.

Multiple papulonodular lesions of varying size over hands in a human immunodeficiency virus infected patient suffering from diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis (case 1)

Chest X-ray and ultrasound of abdomen were normal. His CD4 count was 126 cells/μL and HIV viral load was <47 copies/mL. The patient was initially suspected to be having histoplasmosis, which was ruled out by skin biopsy.

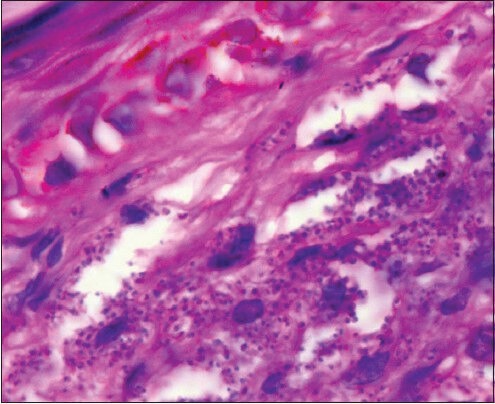

Punch biopsy of skin lesions showed sheets of histiocytic cells in the sub epithelial tissue, stuffed with numerous amastigotes of Leishmania. Mild lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrate was also noted [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Microphotograph of skin biopsy showing collection of amastigote forms of leishmania (LD bodies) within the histiocytes and also extracellularly (H and E, ×400) (case 1)

The patient was treated with ketoconazole 200 mg twice a day and 450 mg rifampicin daily for 1 month along with ART (nevirapine, stavudine and lamivudine). The patient improved on treatment but later was lost to follow-up.

Case 2

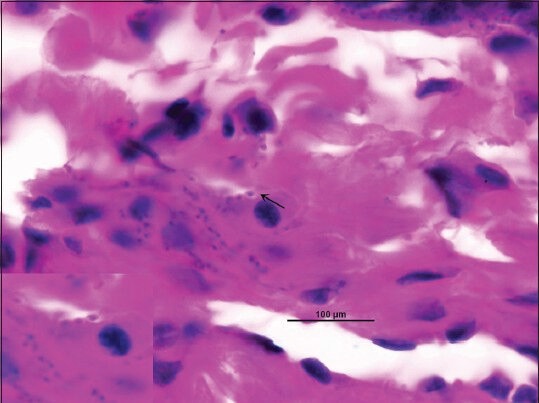

This was a second case of a 43-year-old male laborer, diagnosed as HIV positive 2 years back who was on ART and anti-tubercular treatment for the past 9 months. He presented with a 7 month history of asymptomatic skin lesions all over his body. Physical examination revealed multiple bilateral asymmetrical diffuse, papulonodular, non-itchy skin lesions of size 2-25 mm on the face, trunk and extremities. Lesions first appeared on the arm and progressively spread to involve the face, legs and trunk [Figure 3]. There were no signs of ulceration and scarring. There was no lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly. There was no history of travel to endemic areas of leishmaniasis. The patient was initially suspected to be suffering from histoplasmosis, but skin biopsy taken from the nodules ruled it out. Laboratory investigations revealed anemia (Hb-9.1 g/dL). Liver function tests, renal function tests and lipid profile were normal. Ultrasonography of the abdomen was normal. His CD4 count was 50 cells/μL and HIV viral load was 1750 copies/mL. Punch biopsy of skin lesions revealed sheets of histiocytic cells in the sub epithelial tissue, stuffed with numerous amastigotes of Leishmania. Mild lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrate was also noted [Figure 4].

Figure 3.

Multiple papulonodular lesions of varying size over elbow in an human immunodeficiency virus infected patient suffering from diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis (case 2)

Figure 4.

Microphotograph showing intracellular and extracellular amastigote forms of leishmania (LD bodies) in biopsy specimen (H and E, ×1000)

The patient was treated with ketoconazole 200 mg twice daily and 450 mg rifampicin daily for 1 month along with ART (nevirapine, stavudine and lamivudine). The patient initially responded to treatment but later on expired due to chest infection.

DISCUSSION

Leishmaniases are emerging as an important disease in HIV infected persons living in several sub-tropical and tropical regions around the world, including the mediterranean. The HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome pandemic is spreading at an alarming rate in Africa and the Indian subcontinent, areas also with high prevalence of leishmaniases. The number of cases of Leishmania/HIV co-infection is expected to rise owing to the overlapping geographical distribution of the two infections.[6]

DCL is a rare form of leishmaniasis characterized by numerous non-ulcerating papules and nodules with an abundant parasite load, lack of visceral involvement, negative delayed - type hypersensitivity response and a chronic course with incomplete response to treatment and frequent relapses. DCL is characterized by a lack of cell mediated immune response to the parasite as a result of which the multiplication continues unabated. DCL patients have a polarized immune response with high levels of immunosuppressive cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-10, transforming growth factor β and IL-4 and low concentrations of interferon gamma. Profound immunosuppression leads to widespread cutaneous disease.[7] Co-infection of HIV and Leishmania produces cumulative deficiency of the cell mediated immunity, a key factor for primary protection against infection, recurrences, or metastasis of parasites. Such an HIV-infected patient has an atypical and severe clinical presentation of DCL in terms of number (>200), sites and types of lesions (papulonodular).[8]

Both our cases had multiple (>200) papulonodular skin lesions and can be related with low levels of CD4+ T cells which leads to evolution of the disease and its clinical presentation. Although cultures of the biopsy or the aspirate and molecular tests have evolved, demonstration of amastigotes in material obtained from a lesion remains the diagnostic gold standard. In both our patients, punch biopsy of the skin revealed macrophages studded with amastigote forms of the parasite.

Isoenzyme analysis and polymerase chain reaction allow identification of Leishmania to the species level. Leishmania amazonensis and Leishmania mexicana in South and Central America and Leishmania aethiopica in Ethiopia and Kenya has been reported to cause DCL. In the present cases Leishmania species was not characterized as such facilities are limited to reference centers. The present cases most probably were caused by Leishmania tropica as no other species has been reported from Rajasthan. In a region where Leishmania is considered non-endemic (or underreported) these findings warrant further studies/epidemiological investigations, especially with possible risks for immunosuppressed patients. Furthermore DCL in patients with unclear status warrants HIV testing.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alvar J, Vélez ID, Bern C, Herrero M, Desjeux P, Cano J, et al. Leishmaniasis worldwide and global estimates of its incidence. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35671. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rastogi V, Nirwan PS. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: An emerging infection in a non-endemic area and a brief update. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2007;25:272–5. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.34774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma NL, Mahajan VK, Kanga A, Sood A, Katoch VM, Mauricio I, et al. Localized cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania donovani and Leishmania tropica: Preliminary findings of the study of 161 new cases from a new endemic focus in Himachal Pradesh, India. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72:819–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.S M S, T S A, R J, K V, Philip RR, Paul N. Searching for cutaneous leishmaniasis in tribals from kerala, India. J Glob Infect Dis. 2010;2:95–100. doi: 10.4103/0974-777X.62874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khandelwal K, Bumb RA, Mehta RD, Kaushal H, Lezama-Davila C, Salotra P, et al. A patient presenting with diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis (DCL) as a first indicator of HIV infection in India. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;85:64–5. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okwor I, Uzonna JE. The immunology of Leishmania/HIV co-infection. Immunol Res. 2013;56:163–71. doi: 10.1007/s12026-013-8389-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sunder S. Leishmaniasis. In: Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser HS, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, editors. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th ed. U.S.A: McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing Division; 2012. pp. 1709–15. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herrera E, Sanchez P, Bosch RJ. Disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis in an HIV-infected patient. Int J STD AIDS. 1995;6:125–6. doi: 10.1177/095646249500600214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]