Abstract

We report on the use of photo elicitation interviewing (PEI) with 13 participants in a qualitative study of formerly homeless men and women with serious mental illness. Following a respondent-controlled approach, participants were asked to take up to 18 photographs visually portraying positive and negative aspects of their lives and to subsequently narrate the meaning of the photos in a one-on-one interview. Thematic analysis of the photos (N = 205) revealed two approaches to PEI: (a) a “slice of life” and (b) “then vs. now.” Examples show how PEIs yielded deeper, more elaborate accounts of participants’ lives compared to earlier verbal-only interviews. Participants spoke of the benefits of PEI and preferred taking positive as opposed to negative photographs depicting their lives. Implications of PEI as a means of complementing verbal-only data are discussed. By moving away from predetermined content and meaning, respondent-controlled PEIs enhance empowerment and enable creativity.

Keywords: homelessness, mental health and illness, photography / photovoice

The use of visual data in qualitative research has burgeoned in recent years (Spencer, 2011). One such approach is photo elicitation interviewing (PEI; Collier & Collier, 1986; Harper, 2002; Margolis & Pauwels, 2011; Pink, 2007; Spencer). Based on “the simple idea of inserting a photograph into a research interview” (Harper, p. 13), PEI offers an alternative to verbal-only methods of capturing perceptions or experiences. In their definitive book on photo elicitation, Collier and Collier noted that photographs stimulate new thoughts and memories prompted by—but not necessarily contained in—the images. Bukowski and Buetow (2011) added that photographs have surface content as visual records, but they can also make the “invisible visible” (p. 739) by evoking feelings, memories, and thoughts that require verbalization to be accessible to researchers. Because adding sight to sound (through the use of photographs) expands sensory awareness and increases the reflexive process (Harris & Guillemin, 2012), PEI allows researchers to glean insights that might not be accessible via verbal-only methods.

Originating from anthropological research, PEI was first noted in Collier’s (1957) study incorporating photographs as a means of understanding the impact of environmental stressors on neighborhoods and families. Since then, PEI has gained popularity in other disciplines and the associated methods have evolved and expanded (Harper, 2002; Oliffe & Bottorff, 2007; Rose, 2007). This growing diversity in visual methods for research has brought about some confusion in distinguishing the varied approaches. PEI, for example, has often been conflated with a related visual method—photovoice (Wang & Burris, 1997), although the latter is a more recent phenomenon dating to the 1990s.

Photovoice is described as a means of participatory action and empowerment in communities seeking to improve health and influence policy (Carlson, Engebretson, & Chamberlain, 2006; Wang & Burris, 1997). Like photovoice, PEI entails mutuality between researchers and respondents as they focus on visual objects of shared interest (Lapenta, 2011; Rose, 2007). PEI, however, is different from photovoice in a couple of ways. First, PEI is not embedded within a communal participatory or action-oriented agenda, but rather involves photographs and subsequent interviews individualized for reasons particular to the study (Harper, 2002). Such reasons might include obtaining sensitive personal information participants would not be comfortable sharing in a communal setting or a study goal that does not entail community-based participatory action. Second, although PEI is often used in studies focused on health, its applications are more broad-based than those of photovoice, ranging from documentation of traditional cultures (Mead & Bateson, 1942) to psychology experimentation (Epstein, Stevens, McKeever, & Baruchel, 2006).

Despite growing interest in PEI, the methods are far from standardized and researchers have defined and used it in varied ways (Clark-Ibanez, 2004; Harper, 2002; Lapenta, 2011). A crucial pivot point lies in deciding who takes the photographs and interprets them—the researcher, the respondent, or both parties working together. Traditionally, researchers have controlled the visual media used in their studies. Gong and colleagues (2012), for example, used selected photographs and associative memory techniques with home care workers to trigger explanations of difficult aspects of their work with the elderly and disabled. In contrast, respondent-controlled PEI, sometimes referred to as auto-driven (Clark, 1999) or reflexive photography (Prosser, 1998), leaves the decision on what to photograph up to the respondent, with the subsequent interview an exercise in joint meaning making with the interviewer.

In this article, we report on use of respondent-controlled PEI to explore aspects of participants’ lives more easily broached via images than direct verbal elicitation alone. To accomplish this, we draw on experience derived from Phase 1 of a longitudinal qualitative study of formerly homeless adults living in New York City. Research questions included (a) Can PEI be used to elicit sensitive or less-tangible phenomena that are omitted from verbal-only interviews? (b) How do study participants use visual data and accompanying interviews when exercising control over the PEI process? This study is among the first to examine uses of PEI with this population.

The New York Recovery Study: Rationale for Use of PEI

The New York Recovery Study (NYRS) began in 2010 as a longitudinal qualitative study of newly housed (formerly homeless) adults with serious mental illnesses such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. The promise of mental health recovery, once considered chimerical, has been empirically demonstrated and adopted as a critical goal in mental health services (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2009). The NYRS was guided by empowerment theory in its focus on individual self-determination as key to mental health recovery (Padgett & Henwood, 2009). As conceptualized by Freire (1970), empowerment theory includes both praxis and outcome, with praxis entailing action and reflection. The NYRS focused on praxis as it closely aligns with the recovery model tenet that recovery is an idiosyncratic journey of progress and self-reflection (Deegan, 2002). The use of qualitative methods was considered an optimal fit for this process-oriented approach (Morse, 2008).

The study’s design involved interviewing study participants every 6 months for 18 months to learn about their individual trajectories of recovery from and with serious mental illness. With regard to empowerment praxis, NYRS study questions focused on personal strengths as well as barriers to recovery experienced by participants as they entered housing and attempted to pursue a recovered life. Although mental health recovery has objective dimensions such as symptom reduction, enhanced daily functioning, and positive social relationships, it is invariably a subjective experience (Deegan, 2002). Indeed, each of these so-called objective dimensions depends on the respondent’s report as well as clinical observation. Recovery also embodies less-tangible phenomena such as hope, empowerment, and feeling part of society (SAMHSA, 2009).

In prior research with members of this population, we found it less productive to ask participants about abstract things such as hope, as well as concrete topics such as their goals for the future. We also found it difficult and bordering on insensitive to broach the subject of recent or past traumatic events. Direct questioning in pilot interviews was met with disclaimers or scripts picked up from years of therapy and rehabilitation; for example, “I had some bad things happen to me that I can’t talk about,” or “I’m just focused on taking it one day at a time.” This combination of concerns about sensitive topics, eliciting less-tangible phenomena, and the desire to foster more empowering methods made the incorporation of PEI a valuable addition to the NYRS methodological toolkit in 2011.

Methods

In-depth interviews in the NYRS centered on a priori domains such as mental health status and substance use; minimally structured questions and probes were used to leave room for additional information about key events in participants’ lives. In this context, the addition of PEI was considered optimal for giving participants further opportunities to share information. Reviewing the options available, we settled on using PEI according to these principles: (a) visual data to enhance and deepen (non-PEI) interviews, (b) participant control of the photography with minimal direction, (c) shared meaning making and reflection with the study interviewer, and (d) respect for privacy and sensitivity.

Participant Sampling

Participants were purposively sampled based on the interviewers’ nominations. Interviewers were social work or public health graduate students who had previous experience working with the study population. The offer to engage in PEI was made within 2 weeks of the verbal-only baseline interview. Participants were selected based on verbal capacity and level of engagement in the study. Those not invited were having difficulties with psychiatric or physical illness. Participants who agreed were invited to participate in two PEIs scheduled about a year apart to ascertain change over time in the content of their photographs and their narratives of recovery. At the last session, the participant would be allowed to keep the camera. This report focuses on the first wave of PEIs.

Sample Characteristics

Sixteen (out of 39) individuals were nominated and 2 refused participation, citing new physical ailments and reluctance to use a camera; 1 participant was later withdrawn for ethical reasons described below. Demographic characteristics of the remaining 13 participants included 2 women and 11 men. Nine were African American, 1 was Hispanic, and 3 were White. Average age of the sample was 45 years; 9 were high school graduates or the equivalent and 4 had some college education. In terms of gender and ethnicity, this purposive subsample was representative of the larger sample from which they were drawn, as well as the larger population of formerly homeless adults in New York City.

PEI Implementation

After providing informed consent, participants were asked to take up to 18 photographs over a 2-week period, of which some should reflect positive aspects of their lives and some reflect negative or challenging aspects. The minimal instructions ensured that participants would exercise control over what to shoot and what to narrate about the photographs in a manner representative of their life experience. Participants were also given a brief tutorial on using a digital camera, a handout outlining safety tips on taking photographs in the community, and a set of photo release permission forms (to be signed and returned if they took identifiable photos of individuals). To remind participants of the various camera functions and the task they had agreed to complete, we gave them an instructional sheet and attached a small laminated tag to the camera briefly detailing the assignment.

Implementation of PEI had very few glitches. Two participants needed an additional instructional session on camera use and 1 lost his camera. At the designated time of the PEI, the interviewer (who had conducted the previous verbal-only interview and knew the participant) took the camera to a local drugstore and made hard copies of the photos (taking 10 to 15 minutes). Hard copies of the photos allowed participants to arrange and present them in the order they chose, thereby increasing their control over the interview.

Recorded interviews took place in a private office, with the participant presenting the photos and narrating their meaning to the interviewer. Interviewers asked general questions such as, “Why did you take that picture?” or “Can you tell me more about that?” Participants were given a $30 cash incentive and round-trip subway fare for the interview session. The digital version of the photographs was uploaded to a secure server for storage and later analysis. All protocols were approved by our university’s human subjects committee.

Ethical Issues

As Pink (2007) noted, ethical decisions continue to arise throughout a PEI study. We were fortunate to have only one concerning incident—a participant photographed several individuals whom he described as gang members and drug dealers visiting the apartment of a family member. He arrived at the interview without signed consent forms, assuring us that he received verbal permission from the individuals photographed. Although signed permission forms were later provided, we thought it prudent for all concerned to exclude him and those photos from the PEI participant group.

The potential for emotional upset triggered by painful memories was an ongoing ethical concern in the study and was not unique to the PEI methods. As with the non- PEI interviews, we had a protocol in place to make referrals for counseling to anyone who appeared distraught or asked for assistance (none has been needed thus far). In practice, some PEI sessions were accompanied by tears and many of the photos brought to the surface a welter of emotions. These sessions also included rueful humor and small celebrations of life. None of the participants asked to withdraw from further participation or to withhold their photographs from the study.

Benefits of PEI for the Study: Deeper, More Elaborated Accounts

PEI gave us the opportunity to compare what we learned from participants through their verbal-only interviews with what they expressed when using photos as a medium of expression. The reflexive process made possible by introducing respondent-controlled visual stimuli led to deeper and more elaborated accounts as well as new information. These accounts did not conflict with what had been previously shared in the verbal-only interviews. In the paragraphs below, we offer illustrative examples of these findings.

Greater Detail

Ian (all names are pseudonyms) returned with photographs that detailed his life experiences in ways that he had been reluctant to talk about in the verbal-only interview. Figure 1 was taken of a building in New York City’s East Village, where his girlfriend had lived with her parents and Ian had spent many pleasant times. Ian’s reason for taking the photo, however, was to talk about her death because of a heroin overdose in a nearby park. In his earlier non-PEI interview, neither the girlfriend nor her death had been mentioned.

This right here is the apartment that my ex-girlfriend lived in. … I was very much in love with her. Unfortunately she was a heroin addict. I didn’t know anything about heroin. I was just a drinker. We didn’t share that in common. I tried to get sober for her and she tried to get clean for me. Um, unfortunately [she] died of a drug overdose, of a heroin overdose.

In his non-PEI interview, Ian had little to say about his family, noting that they lived in New Jersey. In his PEI interview, Ian offered a more detailed description of his family relationships, noting where he lived and his building’s proximity to family members (see Figure 2):

Another important thing is this is my building, but the reason I took this picture is you might be able to see the bridge here … it’s just God watching out for me because another of the wonderful things that happened to me is all of my loved ones live in New Jersey. But the fact that I literally live right under the foot of the George Washington Bridge [on the Manhattan side] is such a wonderful thing because my mother or my sisters can just jump on the highway and get off at the bridge and they don’t have to drive through Manhattan … it’s just very simple. I’ve been seeing so much more of my family. It may not seem like that big of a deal but it’s a very big deal, because it keeps me in very close contact … I can cross the street and jump on the bus [to traverse the bridge].

Figure 1.

Ian’s girlfriend’s apartment.

Figure 2.

Ian’s proximity to family members.

In his baseline interview, Walter spoke sparingly about his drug abuse, saying he had been lured into smoking crack by a woman during a sexual encounter, “and that’s the high that I’ve been chasing ever since.” During the PEI, however, he offered details on the circumstances of his drug abuse and his determination to avoid negative places, especially a neighborhood in Queens that he had returned to while trying to stay clean:

I’d say three months into the [rehabilitation] program, and like people just like throwing stuff down to my feet, telling me I ain’t got to pay for it. I’m talking about drugs, you know, alcohol, you know, they just tried to get me hooked again, you know? But I’m a strong person. I can walk away.

New Information

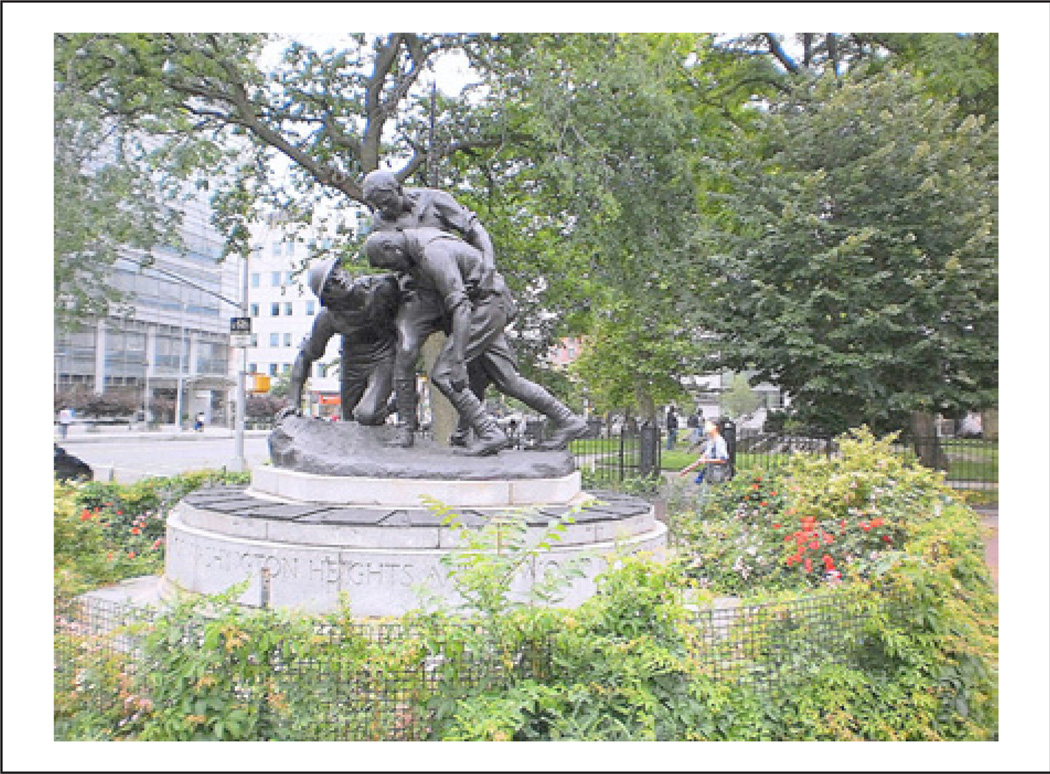

Reflecting on his current sobriety and determination to abstain from drugs and alcohol, Walter shared photos of parks and street life to show the difference in how he saw his environment compared to when he was using (see Figure 3). These quotidian images and accompanying narration were not elicited in the earlier interview yet were volunteered during the PEI:

I didn’t have time when I was getting high to look at these types of things. … They was there, but I probably didn’t see it because I didn’t have time for it. … These are some beautiful places. Maybe some places I was walking by but I wasn’t thinking about taking no pictures or looking at the scenery. All I was thinking about was gettin’ me a dollar, whatever, to get a hit.

Figure 3.

Walter’s sculptures in the park.

Though avoiding mention of his childhood in the baseline interview, Lawrence took advantage of the PEI project to go to long-forgotten places around the city’s boroughs. One of these spots was Coney Island with its boardwalk and piers: “It just came back to me like it was yesterday. I remember being right out there and my grandfather showing me how to bait the hook and everything else like that.” Jose challenged the interviewer to guess why he took a photo of a missing-person flyer in a subway station (see Figure 4), and then explained:

I took the picture not because of the tracks or nothing. I took the picture [pointing to the flyer] because when people with mental health problems like me, that’s what happens. They end up being gone [said with emphasis]. They don’t know where they at, you know, they stop taking their meds [medications]. I don’t wanna be like that. They are around the city, lost … and God forbid something was to happen, you know? Oh, we’re not saying this person might punch somebody off the track because he’s miserable. So I took that picture because that could be me.

Figure 4.

Jose’s missing-person poster.

Claude chose to talk about his daily life by asking a friend to take photos of him in various activities, including doing push-ups, cooking breakfast, and sitting on a park bench:

Sometimes I go to the park. … I sit there and think. I think about my life. What should I do to have a better life, stuff like that. And sometimes I write down everything that happens to me during the day. I write it down in the journal. You know, every positive thing, even the negative things.

Claude also used a photo to tell us of his pride in cooking nutritionally:

I’m the only one who knows how to cook. He [roommate] is cooking bad … he buys a lot of meats, hot dogs, pork chops and stuff like that. … He only fries food, that’s why he got a big stomach. Yeah, but me, I know how to cook. When I get my food stamps I buy vegetables, you know, healthy food, that’s what I do.

Stacey dedicated nearly all of her photos to a family visit to her mother in a nursing home, a visit that included her brother, nephew, sister, and boyfriend. In describing the visit, she used the photos to comment on her family relationships as well as thoughts about her past and hoped-for future:

To me it is like my mother is in jail. … Because I remember being in jail, going to jail. And being confined and you can’t get out. … When I was in jail, my mother came to see me one time. All the years I have been going in and out of jail … it took me a while to get myself together but I straightened my life out. Then for me seeing her in there … At that age I don’t want to be like that … it just depresses me. It makes me want to be stronger because I don’t want to be like her. … She is going through what I went through but in a different way. … And now she is homeless. And I was homeless. You know what I am saying? And she had three extra bedrooms and wouldn’t even take me in, with my kids … so that’s how I look at all that.

Each of the above examples served the purpose of enhancing our understanding of participants’ lives and relationships. This meant delving into traumatic events, unpacking daily routines, expressing concerns about an uncertain future, and showing pride in newfound skills such as cooking. That these were prompted by visual data provided by the participants was a manifestation of the control they exercised over both the photographs and accompanying narration.

Challenges of PEI for the Study: Resistance to Negative Portrayals in the Photographs

A majority of participants (8/13) rejected our request for negative or challenging photographs to counterbalance positive ones. Their reasons are summarized in the following quotes:

It was hard … you know, you say negative and positive, I think I’m doing a lot of things positive, you know? If you woulda given me the camera two years ago, I’d probably showed you a lot of stuff that I been doing negative—maybe not a lot [said with emphasis], but more than what I’m showing you. But, you know, this is what’s going on around me, that’s how I’m taking it.

I couldn’t really find too much negative stuff. I mean I seen a couple of things but I couldn’t take no pictures of it [laughs], like somebody selling drugs. I seen that. Guys in the building smoking weed [marijuana] or whatever. Can’t really take pictures like that … you wind up getting beat up [laughs].

Jane took only positive photos but brought to the interview a list of the negative aspects of her life, explaining, “I can’t take anything negative [reaching for list]. Sometimes I am lonely. How do you take a picture of loneliness? You know sometimes I feel very alone, even if I have someone around me.” The fact that 8 participants resisted producing negative photographs contrasted with the willingness of all participants to talk about negative events and problems in interviews, both verbal-only and PEI. Negative events included loss of child custody, childhood sexual abuse, deaths of close family members, extended periods of incarceration, and past acts of violence against others. Jane’s comment about portraying loneliness points to one possible explanation: some problems are not amenable to visualization. Moreover, the thought and planning required to photographically depict negative aspects of one’s life requires time and emotional involvement spent on one’s own without a sympathetic listener, as in an interview.

A Typology of Approaches to PEI Used by Study Participants

All of the photos submitted (N = 205) were reviewed and categorized independently by four members of the study team to detect common themes in how PEI was approached in the absence of directives beyond the positive/negative valence requested. Based on consensus discussion, we arrived at agreement on two fundamental approaches that we labeled as “a slice of life” and “then vs. now.” Each participant’s set of photographs coherently fit into one of these categories and the data were saturated; that is, all of the photographs fit into one of these two categories.

Participants who chose a “slice-of-life” approach (n = 7) concentrated on the present rather than the past. Their photographs displayed quotidian aspects of their lives such as cleanly washed dishes (Figure 5) or the neighborhood park (Figure 6). Of the park shown in Figure 6, Jane said, “That’s kind of like where I get my little peace from. … Sometimes I reflect when I am there, you know. I try to work things out that are going bad in my life.” The second approach—“then vs. now”—was adopted by 6 participants who portrayed the “bad old days” to contrast with their current situation. In addition to revealing his girlfriend’s death, Ian showed us a photograph of a bar where he used to drink heavily (Figure 7), which he then contrasted to a photograph of certificates documenting his recent accomplishments in attaining sobriety (Figure 8).

Figure 5.

“Slice of life”: Dishes.

Figure 6.

“Slice of life”: Park.

Figure 7.

“Then vs. now”: Bar Ian used to frequent.

Figure 8.

“Then vs. now”: Ian’s sobriety certificates.

In his own version of “then vs. now,” George spoke about the depths of his addiction, which included selling drugs (Figure 9): “Lots of my negative stuff was in this house here. I was getting high and everything like that here. … I was selling drugs out of here.” Later in the interview, George shared a photograph of a zoo park entrance, saying, “I am interested in the Bronx Zoo. I figured it is something positive ’cause I got to go there one day … look at the animals and stuff like that.” Similarly, Stacey used her family’s visit to her mother to reflect on her past incarceration, and on feeling neglected by her mother yet also pitying her. She went on to affirm her resolution to pursue a more stable and productive life.

Figure 9.

“Then vs. now”: House where George used to sell drugs.

In reflecting on the preference for positivity in the visual images, we returned to the analyses to see if participants who incorporated negative photographs differed in approach from those who took only positive photographs. We found that the 8 participants who resisted taking negative photographs fit almost equally into the two thematic categories. Thus, preferring to focus on the positive did not correspond to how they approached visual data collection. Contrasting past and present, or focusing on the latter, formed the basis for positive imagery.

Benefits of PEI for the Participants

PEI was described as therapeutic—a way to connect or reconnect with people and places that held meaning. Most had never owned or used a camera, let alone a digital camera. According to the participants, PEI gave them something to do, a reason to go out and a reason to reflect on their lives. Jose commented afterward, “I guess things [are] going pretty good for me. I didn’t realize it until taking these pictures. I’m not doing so bad.”

Walter was gratified that he was able to keep hard copies of the photos: “I’d like to keep them. Thank you ma’am, because this is something positive in my life I can look at, and I want to show them.” Walter later presented his photos to a group of peers as evidence of or testimony to his progress in recovery. Samuel ended his PEI interview talking about what he had enjoyed during his photographic excursions: “The freedom of it. I can take pictures of whatever I want. … This is a new beginning. I trust myself, I can handle it.”

Lawrence took his camera to Brooklyn’s Coney Island Pier, a place he had not been to in over 30 years, and shared this fond reminiscence: “This one means so much to me because I’m forty-eight years old now. Last time I was there was with my grandfather when I was about twelve years old. And that’s the place I caught my first fish.” Joe recounted his experience enthusiastically: “Oh it was fun. … It opened up a whole new world. … I was doin’ somethin’. I fell in love with the camera.”

Discussion

Individualized PEI offers a feasible and rewarding means of understanding sensitive and less-tangible aspects in the lives of vulnerable populations. The logistical and ethical challenges we encountered were minor compared to the benefits. In our experience, respondent-controlled PEI proved to be valuable in deepening and expanding the data beyond what they had shared in verbal-only interviews. It also empowered participants through control of the camera and of their accompanying narratives. Through the PEI encounter, they were able to critically reflect on meaningful aspects of their lives.

The themes “slice of life” and “then vs. now” shed light on how participants viewed themselves and their lives-as-lived. These themes also set the stage for future analyses. For example, the finding that some participants chose to focus on the present and others introduced a past-vs.-present contrast might be tied to differential progress toward recovery over time. In this context, we plan to examine their views of the future, because a common concern expressed by members of this population was how to overcome cumulative adversity amidst an uncertain future (Padgett, 2007)

By staying close to participants’ views of their life, our findings are consistent with studies having similar goals of documentation. For example, a study of homeless Maori women in New Zealand reflected their concerns with safety in public places, health problems associated with addictions, and the search for social support (Bukowski & Buetow, 2011). In taking note of the emotional reactions stirred by the visual images, this article echoes the work of Clark-Ibanez (2004) and Harris and Guillemin (2012), who found that PEI introduced an unprecedented degree of intimacy between participants and researchers. What proved important in our usage was the trusted one-on-one nature of the PEI encounter—an important fit for the individuals we sought to study and learn from.

We learned the importance of vigilance regarding ethical issues, whether arising from the inclusion of people who did not give permission to be photographed or from the occasional wells of emotion tapped by the photographs and their narration. These emotions were offset by trust and rapport but also by the participant’s control over the material that induced the feelings. Of the four principles of use outlined earlier, one—shared meaning making— did not prove to be viable. Participants did not seek (nor did we insist on) this. Instead, they came fully prepared to share their photographs and narrate them without the need to coconstruct meaning with the interviewer.

PEI interviews have stand-alone value in portraying participants’ lives as they want them presented—both visually and verbally (Clark-Ibanez, 2004). However, we did not consider them to be a substitute for non-PEI interviews because the overall study had aims that needed to be addressed and questions answered. In addition, participants’ tendencies to skew toward positive aspects of their life in the photos and the focus on the first round of PEIs in a larger study made for an incomplete picture. The two themes are manifest representations intended to stay close to participants’ meanings. Still in progress, the larger study will afford more opportunities and data for interpretation by assembling each participant’s information (multiple interviews, observational data when available, and PEI interviews and photos when available) for cross-case and grounded theory analyses.

We acknowledge that our use of PEI was for specific purposes that might not fit the needs of other researchers. For example, instructions could be more directive regarding the content of the photographs (or not directive at all). The cocreation of meaning might be more appropriate for other studies, as well as the extension of PEI to all participants. Nevertheless, our experiences, in combination with those of others (Bukowski & Buetow, 2011; Clark-Ibanez, 2004), have shown how PEI can yield new and richer insights into participants’ lives that might not have emerged from verbal-only interviews. They also used the camera as a means of emotional catharsis and creative expression that went beyond literal depictions and descriptions.

These experiences are consistent with the work of neuropsychologists who have found that pictures and words are processed by the brain in differing ways, with the former having more immediate emotional impact (Kim, Yoon, & Park, 2004). According to LeClerc and Kensinger (2011), “For pictures, the effect of emotion might be in evidence immediately and might be evoked relatively automatically, whereas activation of emotional responses for word stimuli may require more in depth and controlled processing” (p. 520). LeClerc and Kensinger’s reference to the positivity effect in memory—that is, a tendency to have more positive than negative appraisals when recalling events—is a plausible explanation for another of our experiences: the resistance to taking negative photographs. This resistance is in line with societal norms favoring use of cameras to capture happy rather than sad or unmemorable occasions. Specific to our study population, participants are frequently urged by providers and family members to stay positive and leave behind the people, places, and things that had caused so many problems earlier.

Research on emotion processing and regulation by the brain raises interesting questions about the varied responses to visual and verbal stimuli. Although beyond the scope of this article, these questions can provide a fruitful line of inquiry in qualitative health research. Photographic images are likely to tap differing and more immediate memories and emotional reactions than verbal statements (Harris & Guillemin, 2012). As we have shown, such differences do not necessarily connote discrepant or conflicting information.

It is difficult to think of a better way to invite participants to approach their lives both literally and metaphorically. Moreover, the introduction of PEI brought active engagement that fit with an ethos of consumer empowerment constituting a key part of the larger study’s raison d’être. It also afforded participants the opportunity to be creative in both visual and verbal representations. In the future, we plan to organize a public-gallery showing of photographs taken by those participants who wish to “go public” with their work.

Conclusion

Photo elicitation interviews (PEIs) complement verbal-only methods in research, particularly when study participants have had painful or sensitive life experiences that are difficult to verbalize, and when they are able to exert control over the images they choose to share. By moving away from predetermined content and meaning, respondent- controlled PEIs enhance empowerment and enable creativity. Qualitative research has much to gain by using PEIs alone or in connection with other forms of data. Vulnerable and underserved populations, such as the persons featured in this article, are likely to benefit from this approach because it offers them an opportunity to “show and tell” both literally and figuratively.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH084903).

Biographies

Deborah K. Padgett, PhD, MPH, is a professor at New York University School of Social Work in New York, New York, USA.

Bikki Tran Smith, MA, is the project director at the New York Recovery Study and a master’s student at New York University School of Social Work in New York, New York, USA.

Katie-Sue Derejko, MA, MPH, is a research scientist at the New York Recovery Study at New York University School of Social Work in New York, New York, USA.

Benjamin F. Henwood, PhD, MSW, is an assistant professor at the University of Southern California School of Social Work, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Emmy Tiderington, MSW, is a research scientist at the New York Recovery Study and a doctoral student at New York University School of Social Work in New York, New York, USA.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Bukowski K, Buetow S. Making the invisible visible: A photovoice exploration of homeless women’s health and lives in central Auckland. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;72:739–746. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carlson ED, Engebretson J, Chamberlain RM. Photovoice as a social process of critical consciousness. Qualitative Health Research. 2006;16:836–852. doi: 10.1177/1049732306287525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark CD. The autodriven interview: A photographic viewfinder into children’s experiences. Visual Sociology. 1999;14:39–50. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark-Ibanez M. Framing the social world through photo-elicitation interviews. American Behavioral Scientist. 2004;47:1507–1527. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collier J. Photography in anthropology: A report on two experiments. American Anthropologist. 1957;59:843–859. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collier J, Collier M. Visual anthropology. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deegan PE. Recovery as a self-directed process of healing and transformation. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health. 2002;17(3):5–21. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Epstein I, Stevens B, McKeever P, Baruchel S. Photo elicitation interview (PEI): Using photos to elicit children’s perspectives. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2006;5(3):1–9. Retrieved from www.ualberta.ca/~iiqm/backissues/5_3/PDF/epstein.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freire P. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Seabury Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gong F, Casteneda D, Zhang X, Stock L, Ayala L, Baron S. Using the associative imagery technique in qualitative health research: The experiences of homecare workers and consumers. Qualitative Health Research. 2012;22:1414–1424. doi: 10.1177/1049732312452935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harper D. Talking about pictures: A case for photo elicitation. Visual Studies. 2002;17:13–26. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris A, Guillemin M. Expanding sensory awareness in qualitative interviewing: A portal into the otherwise unexplored. Qualitative Health Research. 2012;22:689–699. doi: 10.1177/1049732311431899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim KH, Yoon HW, Park HW. Spatiotemporal brain activation pattern during word/picture perception by native Koreans. NeuroReport. 2004;15:1099–1103. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200405190-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lapenta F. Some theoretical and methodological views of photo-elicitation. In: Margolis E, Pauwells L, editors. Sage handbook of visual research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2011. pp. 201–213. [Google Scholar]

- 15.LeClerc CM, Kensinger EA. Neural processing of emotional pictures and words: A comparison of young and older adults. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2011;36:519–538. doi: 10.1080/87565641.2010.549864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Margolis E, Pauwels L, editors. The Sage handbook of visual research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mead M, Bateson G. Balinese character: A photographic analysis. New York: New York Academy of Sciences; 1942. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morse J. Styles of collaboration in qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Health Research. 2008;18:3–4. doi: 10.1177/1049732307309451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oliffe JL, Bottorff J. Further than the eye can see? Photo elicitation and research with men. Qualitative Health Research. 2007;17:850–858. doi: 10.1177/1049732306298756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Padgett DK. There’s no place like (a) home: Ontological security in the third decade of the"homelessness crisis” in the United States. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64:1925–1936. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Padgett DK, Henwood BF. Obtaining large-scale funding for empowerment-oriented qualitative research: A report from personal experience. Qualitative Health Research. 2009;19:868–874. doi: 10.1177/1049732308327815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pink S. Doing visual ethnography. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prosser J. Image-based research. London: Routledge; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rose G. Visual methodologies: An introduction to the interpretation of visual materials. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spencer S, editor. Visual research methods in the social sciences: Awakening visions. New York: Routledge; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Guiding principles of recovery. SAMHSA News. 2009;17(5) Retrieved from www.samhsa.gov/samhsanewsletter/Volume_17_Number_5/GuidingPrinciples.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang C, Burris M. Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education and Behavior. 1997;24:369–387. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]