Abstract

This study compares lexical access and expressive and receptive vocabulary development in monolingual and bilingual toddlers. More specifically, the link between vocabulary size, production of translation equivalents, and lexical access in bilingual infants was examined as well as the relationship between the Communicative Development Inventories and the Computerized Comprehension Task. Twenty-five bilingual and 18 monolingual infants aged 24 months participated in this study. The results revealed significant differences between monolingual and bilinguals’ expressive vocabulary size in L1 but similar total vocabularies. Performance on the Computerized Comprehension Task revealed no differences between the two groups on measures of both reaction time and accuracy, and a strong convergent validity of the Computerized Comprehension Task with the Communicative Development Inventories was observed for both groups. Bilinguals with a higher proportion of translation equivalents in their expressive vocabulary showed faster access to words in the Computerized Comprehension Task.

Keywords: bilingualism, infancy, lexicon, lexical access

In many parts of the world, growing up bilingual is the norm rather than the exception. A substantial proportion of these bilingual children acquire their two languages simultaneously from birth. A major debate in bilingual research is whether bilingual children acquire their first language at the same rate and in the same way as monolingual children. Research on bilingualism has a long history in which many aspects of language development have been examined. More specifically, morphosyntax, lexicon, and phonology have been compared between bilingual and monolingual children. Despite this research, it remains unclear what distinguishes the early stages of bilingual and monolingual lexical development (for a review, see Genesee & Nicoladis, 2007). The present study compares lexical development in 24-month-old bilingual and monolingual children. More specifically, we explore the consistency between vocabulary measures from a parental report and a laboratory-based test. Furthermore, we investigate the relation between exposure to a second language, receptive and expressive vocabulary, proportion of translation equivalents (TEs), and lexical access in young children. By measuring reaction time with a computerized word comprehension test, we were able to compare the mechanisms of lexical access in young bilinguals and monolinguals and examine for the first time the link between TEs and speed of lexical access in young bilinguals.

Throughout the elementary school years, standardized measures of oral language proficiency (expressive and receptive vocabulary size) reveal a gap between monolingual and bilingual children (Bialystok, Luk, Peets, & Yang, 2010; Cobo-Lewis, Pearson, Eilers, & Umbel, 2002; Eilers, Pearson, & Cobo-Lewis, 2006). Even as adults, bilinguals tend to have a smaller vocabulary size in each of their spoken languages when compared to monolinguals (Perani et al., 2003; Portocarrero, Burright, & Donovick, 2007). In addition, bilinguals show deficits in lexical retrieval when performing a verbal fluency task and experience more interference in lexical decision tasks (Gollan, Montoya, Fennema-Notestine, & Morris, 2005; Ransdell & Fischler, 1987; Rosselli et al., 2000). Finally, bilingual children and adults show poorer accuracy and slower reaction times in picture naming tasks (Kohnert & Bates, 2002), even when naming pictures in their first language (Ivanova & Costa, 2008).

Several explanations for these differences between the language development of monolingual and bilingual children may be proposed. Differences in vocabulary size and access may be attributed to experiential differences in the processes of acquisition and language use. For example, bilinguals may encounter specific items in a context where only one language is used, thereby decreasing the number of words acquired in that language. With regard to lasting deficits in lexical retrieval, two main hypotheses have been proposed. One proposition is the weaker links hypothesis, which attributes the poorer access seen in bilinguals to the differences in the frequency with which associative networks between words and concepts are used, with monolinguals being exposed to a greater frequency than bilinguals in a particular language (Gollan, Montoya, Cera, & Sandoval, 2008). In contrast, the competition hypothesis proposes that more effortful processing is required by bilinguals to access words in each language than by monolinguals because of the need to inhibit interference from the competing language (Dijkstra, 2005; Green, 1998).

Research examining first language acquisition in bilingual children has shown that they produce their first words at about the same time as monolingual children (Genesee, 2003; Patterson & Pearson, 2004; Petitto et al., 2001). Nevertheless, evidence for differences in vocabulary development in bilingual and monolingual children is mixed depending on the age of the child and whether receptive or expressive vocabulary is being reported. For example, in large samples of preschooland school-aged children, a smaller receptive vocabulary size in L1 has been reported in bilinguals compared to monolinguals (Bialystok et al., 2010; Mahon & Crutchley, 2006). Other studies conducted on small samples have shown a non-significant trend in the same direction when comparing monolinguals’ and bilinguals’ receptive vocabulary size (Cromdal, 1999; Yan & Nicoladis, 2009). Moreover, when expressive language is measured, school-aged bilinguals tend to have a smaller vocabulary size even when both languages are combined (Yan & Nicoladis, 2009). In younger bilinguals (below the age of 3 years), total receptive and expressive vocabulary size have been reported to be comparable to that of monolinguals, although these bilinguals tend to have fewer words in each of their separate expressive languages (Junker & Stockman, 2002; Marchman, Fernald, & Hurtado, 2009; Oller & Eilers, 2002; Pearson, Fernández, & Oller, 1993, 1995; Petitto & Kovelman, 2003). A variable that influences a child’s total vocabulary size is the amount of time he/she is exposed to a given language, where greater exposure is associated with a larger vocabulary size (David & Wei, 2008; Pearson, Fernández, Lewedag, & Oller, 1997). Therefore, estimates of vocabulary size need to be accompanied by detailed information about language exposure history.

Most studies on very young bilinguals’ lexical development rely on parental reports, such as the MacArthur–Bates Communicative Development Inventories (CDI; Fenson et al., 1993). These measures tend to underestimate bilingual children’s vocabulary size (De Houwer, Bornstein, & Leach, 2005; Houston-Price, Mather, & Sakkalou, 2007). To avoid such underestimation, the CDI should be completed by multiple reporters, a requirement that is difficult to meet, especially for working families (De Houwer et al., 2005; Marchman & Martínez-Sussman, 2002). Thus, studies using direct, laboratory-based assessments are essential to provide an accurate estimate of early lexical development in bilinguals. To our knowledge, only one study has reported high concurrent validity of the CDI with laboratory measures of vocabulary development (Marchman & Martínez-Sussman, 2002). The current study compares receptive and expressive vocabulary size in monolingual and bilingual toddlers, as well as replicates and extends the concurrent validity of the CDI with a laboratory-based measure of vocabulary size.

Another issue that arises with respect to early bilingualism research is whether or not the vocabulary learned in one language is independent of the vocabulary learned in the other (De Houwer et al., 2005). When a bilingual child knows the word for a concept in both languages, this is known as a TE (e.g. “dog” and “chien”). This issue is important because the acquisition of TEs violates the principle of mutual exclusivity (one word for each object) documented in young word learners. The presence of TEs in very young bilinguals also provides evidence against the hypothesis of a fused or unitary linguistic system in bilinguals and is consistent with the idea that bilinguals have two distinct lexical systems, making it necessary to switch across the two systems (Genesee & Nicoladis, 2007; Patterson & Pearson, 2004).

Research on early lexical development has shown that young bilingual children acquire TEs by the middle of the second year (Genesee & Nicoladis, 2007; Junker & Stockman, 2002; Quay, 1995; Schelleter, 2002). The proportion of TEs in a child’s overall vocabulary tends to be low before the age of 18 months and increases steadily, reaching about 30% by the end of the second year (David & Wei, 2008; Lanvers, 1999; Nicoladis & Secco, 2000; Pearson et al., 1995). Individual children vary in the number of TEs they have in their vocabulary and in the rate of acquisition of TEs (David & Wei, 2008; Pearson et al., 1995). As is the case for vocabulary size, the proportion of TEs is influenced by language exposure, with more balanced exposure producing more TEs (David & Wei, 2008; Pearson et al., 1997). Individual variability in the proportion of TEs is well documented across children who are at the same stage of lexical development; however, the causes for this variability remain to be investigated. The current study examines the relation between the proportion of TEs, exposure to a second language, and receptive and expressive vocabulary size in bilingual toddlers.

Language comprehension in young bilinguals has received less attention than has language production or preverbal speech processing (Bosch & Sebastián-Gallés, 2001; Werker & Byers-Heinlein, 2008). Yet, an understanding of the process through which bilingual children learn to comprehend their two languages is critical for documenting early lexical access. Such access is typically tested using word comprehension tasks in studies with bilingual adults and children. In one of the few systematic studies on this issue, parents of 13-month-old French–Dutch bilingual infants were provided with a checklist of words and asked to indicate the number of words their child understood (De Houwer, Bornstein, & De Coster, 2006). All children in the sample had TEs (M = 17%), but there was a lot of variability, ranging from 1% to 61%. These findings suggest that near the start of language comprehension, in the beginning of the second year of life, some bilingual infants understand the meanings of words in both their languages.

There are few studies on young bilingual children’s lexical development that use laboratory-based tests, and those that exist indicate both similarities and differences between monolingual and bilingual infants in word recognition and word learning. With regard to word recognition, a study including a behavioral task and Event Related Potentials (ERP) recordings indicated that 10-month-old bilingual infants showed recognition of familiar words in each of their languages. This ability to recognize familiar words occurred at the same age as reported for monolingual infants (Vihman, Thierry, Lum, Keren-Portnoy, & Martin, 2007). Recent studies have shown that parental reports of receptive and expressive vocabularies predicted performance on word comprehension in a preferential looking task for both bilingual and monolingual infants (Houston-Price et al., 2007; Marchman et al., 2009; Styles & Plunkett, 2009). Regarding bilinguals’ ability to learn new words, research findings are mixed. When compared to monolingual infants, bilingual infants showed a delay in the ability to associate words and objects when the words sounded similar (Fennell, Byers-Heinlein, & Werker, 2007). However, data from a recent study suggest that 17-month-old bilinguals are more adept at learning word–object associations when productions of the Nonce words in each of their languages were included (Mattock, Polka, Rvachew, & Krehm, 2010).

To summarize, much of the research on bilingual language acquisition has focused on expressive vocabulary development based on parental reports, particularly the CDI. Consequently, lexical retrieval in word comprehension contexts is poorly understood in very young bilingual children. The current study aims to fill this gap by examining the accuracy and speed of lexical access in 24-month-old monolingual and bilingual infants. The design includes a wide range of variables to provide a comprehensive assessment of early lexical development in bilinguals. Will young bilinguals demonstrate slower word retrieval in a comprehension task when compared to monolinguals with a similar total lexicon size? In addition, the relation between reaction time and accuracy during a word comprehension task and the proportion of TEs, language exposure, and vocabulary size in young bilingual children is explored. The inclusion of these variables was motivated by the limited data available on how the linguistic input received by bilingual infants predicts vocabulary development, as well as the level of bilingualism measured by the proportion of TEs. Are bilingual children who are exposed to a balanced input of two languages more likely to acquire TEs? Additionally, an important issue was to examine whether the proportion of TEs in young bilinguals’ vocabulary would impact their speed of lexical access, as it does in adult bilinguals. Adult bilinguals name pictures more quickly when TEs are presented explicitly or when they know the TEs of the target words (Costa & Caramazza, 1999; Gollan et al., 2005). Since picture naming cannot be used with young children, we tested lexical access with the Computerized Comprehension Task (CCT), an assessment tool building on the preferential looking and picture book approaches (Friend & Keplinger, 2003). This standardized task requires infants to touch images on a screen in response to auditory prompts from an experimenter and has been found to be successful in testing infants as young as 16 months. To our knowledge, no study has examined reaction time and accuracy of word comprehension in very young bilinguals.

Based on past research with very young bilinguals, it was predicted that bilingual children’s expressive vocabulary size in L1 would be smaller than that of monolinguals but that the vocabulary of the two groups would be comparable when bilinguals’ L1 and L2 vocabularies are combined. We expected performance on the word comprehension task in L1 to differ across the two groups, with monolinguals outperforming bilinguals in accuracy and reaction time. Finally, it was predicted that the proportion of TEs for bilinguals would be linked to exposure and vocabulary size in L2 and that processes of lexical retrieval (e.g. latency) would be facilitated by the level of bilingualism of the children, as assessed by the proportion of TEs in the vocabulary. Taken together, this study provides a unique opportunity to examine early lexical development in very young bilinguals with a range of assessment tools.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited from birth lists provided by a government health agency. In addition, some participants were recruited using birth announcements from local newspapers. Children with any hearing or visual problems were not eligible to participate. In total, 75 children were tested. Of these, some were excluded due to fussiness (n = 9), their L1 being neither English nor French (n = 5), noncompliance or an inability to complete testing or the required questionnaires (n = 7), or not meeting the language selection criteria (n = 11). The remaining sample (n = 43) was split into monolinguals and bilinguals based on the exposure to their first language.

The selection criterion for monolinguals required infants’ overall exposure to their first language (L1), either French or English, to be greater than 90%. The final monolingual sample was composed of 18 infants, which included 8 females and 10 males ranging from 23.1 to 26.1 months of age (M = 24.9, standard deviation (SD) = .8). The sample’s overall L1 exposure ranged from 90.6% to 100% (M = 97.1, SD = 3.4) and their L1 vocabulary ranged from 7 to 564 words (M = 335, SD = 161). Twelve monolingual children spoke English, and six spoke French.

The selection criteria for bilinguals required infants to have been exposed to their L2 from birth and to have either French or English as their L1. The final bilingual sample was composed of 25 infants aged between 23.5 and 25.9 months (M = 24.3, SD = .5) and included 15 females and 10 males. L2 exposure ranged from 18% to 49% (M = 35.0, SD = 9.5), with all children except three having more than 25% exposure to L2. Bilinguals were exposed to their L2 for an average of 42.3 h per week. Monolinguals’ average exposure to a second language was 1.9 h per week. Since the participants lived in a multilingual city, the selection criterion is similar to, but somewhat less conservative than that used in other bilingualism studies (David & Wei, 2008; Pearson et al., 1997). Nine of the bilingual children spoke English–French, 11 spoke French–English, 3 spoke English–Italian, 1 spoke English–Hebrew, and 1 spoke French–Turkish.1

Materials

Language exposure questionnaire

The infants’ language exposure to L1 and L2 was measured by the language exposure questionnaire, which has been used to identify monolinguals and bilinguals in previous research (Bosch & Sebastián-Gallés, 1997; Fennell et al., 2007). Language exposure was calculated using two estimates, a direct as well as an indirect one. Indirect exposure was deemed appropriate as recent research has shown that toddlers learn words through media exposure (Krcmar, Grela, & Lin, 2007; Zimmerman, Christakis, & Meltzoff, 2007). The questionnaire was administered in an interview format. The first estimate (direct exposure) measured the amount of time an infant spent interacting with family or friends in any language over a week’s time. Parents were asked information regarding who speaks to the child (e.g. parents, daycare staff, and siblings), in what language, since when, and for how many hours per week. To calculate the direct language exposure for each child, the percentage of time the child is directly exposed to each language in a given week was determined. The second estimate (indirect exposure) measured the percentage of time the infant spent exposed to any language throughout the course of a day. This measure included exposure to television and radio. These two percentages were averaged to produce an overall exposure measure for L1 and L2.

MacArthur-Bates CDI: Words and sentences

The CDI is a parent report vocabulary checklist consisting of 680 words containing nouns, verbs, and adjectives that measures a child’s expressive vocabulary between the ages of 16 and 30 months (Fenson et al., 1993). The American English (Fenson et al., 1993), French Canadian (Trudeau, Frank, & Poulin-Dubois, 1999), Hebrew (Maital, Dromi, Sagi, & Bornstein, 2000), Turkish (Küntay et al., 2009), and Italian (Caselli & Casadio, 1995) adaptations were used. Although we requested that each CDI be filled out by the person who spoke the target language with the child, 56% of the children had the CDI completed by two reporters.

CCT

This computer program was created by Friend and Keplinger (2003) to assess language comprehension in very young children. This task is more appropriate to assess the accuracy and speed of word retrieval in 24-month-old toddlers than procedures based on visual fixation time. The program presents 41 pairs of images representing nouns (23 pairs), verbs (11 pairs), and adjectives (7 pairs) in the child’s first language. The two images appear simultaneously on a computer touch screen, one on the left-hand side and the other on the right-hand side. The images are matched on size, color, brightness, difficulty, and word class (noun, adjective, and verbs). Word difficulty was determined based on normative parent report data from the CDI: words and gestures (Dale & Fenson, 1996). Words were classified as easy if they were comprehended by more than 66% of 16-month-olds, moderately difficult if comprehended by 33%–66%, and difficult if comprehended by less than 33%. There were similar numbers of easy, moderate, and difficult word pairs in the task. The children were instructed to touch the appropriate image on the screen. A touch to the target image produced a reinforcing auditory signal, while no such reinforcement occurred when the nontarget image was touched. In addition, target images appeared equally often on the right- and left-hand sides. The original program only measured accuracy and was modified to provide reaction time as well. Accuracy was calculated as the sum of correct answers for all 41 trials. Reaction time was measured from the moment the image was presented until the infant touched the screen for each trial. Images appeared on the screen for 7 s and then disappeared. If the child did not touch the screen, the next picture was presented, and that trial was coded as missing. The CCT was presented in either English or French according to the child’s L1. A French adaptation of the CCT was available that included a few changes from the original version in order to account for cultural differences.

Procedure

Participants were first brought into a reception room where they were familiarized with the experimenter and the environment. Parents were asked to sign a consent form and complete a short demographic questionnaire. Once completed, the experimenter filled in the language exposure questionnaire with the information provided by the parents. Depending on language exposure, infants were classified as either monolingual or bilingual. If classified as monolingual, parents were asked to complete the CDI and the total number of words indicated the child’s total vocabulary. If a participant was classified as bilingual, parents were asked to complete the CDI in both languages. In order to measure a child’s vocabulary size in L1, the number of words indicated on the L1 CDI was summed. To determine the total vocabulary size, words in L1 and L2 were added, and from this, total words similar in sound and spelling (cognates) were subtracted (e.g. jeans, jeans). The proportion of TEs for each child was calculated by multiplying the number of TEs by two and dividing this number by the total vocabulary size minus the cognates, semicognates, and nonequivalents. A nonequivalent is a word that does not have a translation on the CDI in the child’s other language, and a semicognate is a pair of words (one from each language) that sound similar but have a slightly different spelling (e.g. mittens, mitaines).

Next, the participant was led into an adjoining room to start the administration of the CCT in their dominant language. The participant was placed in a baby seat attached to the table with a touch screen located at arm’s reach, with the parent seated behind him/her. The experimenter was next to the child and controlled the presentation of the images on the screen. Four training trials using easy words were administered before the test phase to allow the child to become familiar with the task. The training trials could be administered as many times as necessary for the child to understand the task. At the start of each trial, the screen was blank, and the experimenter asked the child “Where’s the ____?, touch the _____,” or “Who is _____?, touch the one who is _____,” or “Which is _____?, touch the ____ one” for nouns, verbs, and adjectives, respectively. Then, the two images appeared on the screen. If the child touched the correct image he or she was reinforced with a unique auditory signal. During the test phase, if the child did not respond within the first 7 s, the reaction time was not recorded. In addition, if a child responded in less than 300 ms, that trial was excluded from the analysis because it was considered to be an anticipatory response. This was done to ensure that the participant did not respond arbitrarily to the question. This task lasted approximately 10 min, and only children who responded to more than half of the 41 trials were included in the final analysis. At the end of the visit, the child was given a small toy, and parents received a $50 financial compensation for their time.

Results

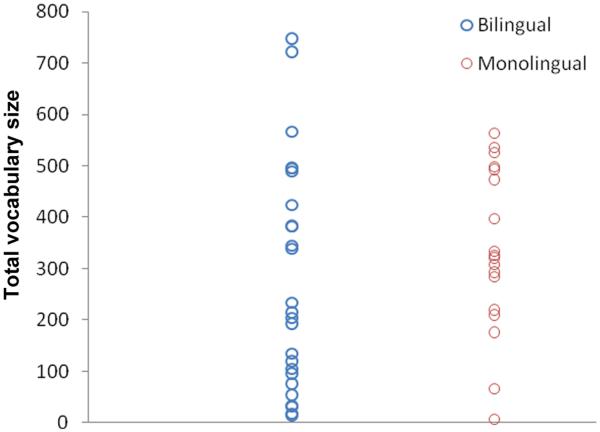

The first analysis compared expressive vocabulary size as measured by the CDI in monolingual and bilingual toddlers. As shown in Table 1, the total expressive vocabulary of monolinguals (L1: M = 335 words, SD = 16, range: 7–564) tended to be larger than that of bilinguals (L1 + L2: M = 276 words, SD = 220, range: 15–748), but the difference was not statistically significant. However, an examination of the distribution of total vocabulary by language group as shown in Figure 1 shows a clustering of bilingual children with very low scores and a clustering of monolingual children with higher scores, suggesting an overall difference between groups that is not statistically significant because of lack of power in the design. Nonetheless, as expected, when only the L1 vocabulary for each language group was considered, monolinguals (M = 335 words, SD = 161) had a significantly larger vocabulary than the bilingual children (M = 187 words, SD = 146), t(41) = −3.14, p < .01.

Table 1.

Mean scores on CDI and CCT task for bilinguals and monolinguals.

| Monolinguals (n = 18) |

Bilinguals (n = 25) |

t-test |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | M | SD | M | SD | t | p |

| Total vocabulary | 335 | 161 | 276 | 220 | −.95 | .35 |

| LI total vocabulary | 335 | 161 | 187 | 146 | −3.14 | .00 |

| Accuracy on CCTa | 63.82 | 15.34 | 62.80 | 18.56 | −.18 | .86 |

| Reaction time on CCT (correct trials)a |

2869 | 730 | 2804 | 546 | −.31 | .76 |

CCT: Computerized Comprehension Task.

For the bilingual sample, only 20 participants completed the CCT.

Figure 1.

Scatterplot of total vocabulary size by language group.

The next and most important set of analyses focused on the convergent validity of the CCT as a measure of word comprehension in monolingual and bilingual toddlers and the comparative reaction time and accuracy of the two language groups. For these analyses, only children who completed both the CCT and CDI were included (monolinguals: n = 18; bilinguals: n = 20). Within the bilingual group, 1.3% (n = 11) of the trials were excluded from the analyses and 1.5% (n = 11) of the trials were excluded in the monolingual group due to anticipatory responses. As shown in Table 1, monolingual and bilingual children performed similarly on the CCT (only administered in their L1 for bilinguals) for both measures of accuracy (number of correct trials out of 41) and reaction time. The proportion of correct responses out of the attempted trials was also similar for the two groups (M = 72.0% and M = 75.5%, for bilinguals and monolinguals, respectively, t(36) = .73, p = .48). We also compared the proportion of correct trials for each difficulty level on the CCT. There were no between-group differences in terms of accuracy across the different difficulty levels on the CCT, including the difficult words (Bilinguals: M = 61.3%, SD = 20.9 and Monolinguals: M = 60.8%, SD = 14.7, t(36) = .60, p = .56).

As expected, children’s accuracy on the CCT was positively correlated with the size of their total vocabulary on the CDI for both the bilingual group, r(18) = .64, p < .01, and monolingual group, r(16) = .59, p < .01. Previous research with English- and Spanish-speaking monolingual children has shown that performance on the CCT is convergent with parental report of receptive vocabulary size (Friend & Keplinger, 2008). The current findings show that such convergence is also observed for bilinguals, even when expressive vocabulary from the CDI is compared to word comprehension from the CCT. Furthermore, the relationship between the comprehension of words on the CCT and the production of those same words on the CDI was examined. This analysis was only performed on the bilingual group because the CDI data of the monolinguals indicated that they produced almost all of the words included in the CCT. A comparison of accuracy on the CCT for these two groups of words revealed that infants performed better on trials with words reported by parents on the CDI (M = 65.3%, SD = 24.8) than on those that contained words that were not reported (M = 52%, SD = 29.4), t(16) = 2.19, p < .04. Thus, these findings provide evidence for the item-level accuracy of both measures of the lexicon and demonstrate a match between the CCT and the CDI for a population of bilingual infants.

The relation between exposure to L2, expressive vocabulary size in L2, and percentage of TEs in the sample of bilinguals was examined (see Table 2). The mean proportion of TEs was 37.4% (SD = 21.2), with significant variability across children (range: 0%–72.2%). As expected, the proportion of words in L2 (M = 33.7, SD = 13.4, range: 1%–51.5%) was positively correlated with the proportion of TEs, r(23) = .68, p <.01, and overall exposure to L2, r(23) = .67, p <.01. Furthermore, there was a tendency for children with more exposure to L2 to possess a higher percentage of TEs in their vocabulary, r(23) = .31, p = .07.

Table 2.

Intercorrelations between L2 exposure, expressive vocabulary, proportion of TE, and CCT measures in bilinguals.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Overall exposure to L2 | – | −.31 | −.48b | .67b | .31 | −.11 | −.32 |

| 2. Total vocabulary | – | .96b | .10 | .65b | .64b | −.22 | |

| 3. LI total vocabulary | – | −.13 | .46b | .61b | −.12 | ||

| 4. Proportion of words in L2 | – | .68b | .35 | −.50b | |||

| 5. TEs | – | .58b | −.49a | ||||

| 6. Accuracy on CCT (n = 20) | – | −.28 | |||||

| 7. RT on CCT (correct trials) (n = 20) | – |

TE: translation equivalent; CCT: Computerized Comprehension Task.

Correlation is significant at the .05 level (one tailed).

Correlation is significant at the .01 level (one tailed).

The proportion of TEs was positively correlated with accuracy on the CCT, r(18) = .58, p < .01, and negatively correlated with reaction time, r(18) = −.49, p < .01. To verify that the children with a higher proportion of TEs did not simply have a larger vocabulary (which could explain their better performance on the CCT), the correlations were recalculated while controlling for total vocabulary size. The correlation for accuracy, r(17) = .29, p = .11, was no longer significant, but the correlation between reaction time and the proportion of TEs remained significant, r(17) = −.46, p < .05. Therefore, while vocabulary size cannot be ruled out as a contributing factor, the robust correlation between TEs and reaction time shows that it is not the only factor. Thus, like in adult bilinguals, these reaction time findings suggest that TEs facilitate lexical access. Ideally, the reaction times to the specific words in the CCT that are TEs (as reported in the CDI) should be lower than those that are not TEs. Unfortunately, because the CCT contains only 41 target words, only four children had a sufficient proportion of TEs included in the CCT (range: .38–.70) to make this comparison possible. Nevertheless, the reaction time on the TEs (M = 2265ms) was, as expected, lower than the words that were not TEs (M = 2707ms), t(3) = 2.76, p <. 06.

Discussion

According to parental reports, our sample of 24-month-old bilinguals had developed an expressive vocabulary size in L1 that was smaller than that of monolinguals. This is consistent with other studies reporting expressive vocabulary size in L1 in very young bilinguals (Pearson et al., 1993). The total vocabulary reported for the bilingual group was statistically similar to that of the monolingual children, although more bilinguals than monolinguals tended to have small vocabularies. These results support the view that that there is a deficit in young bilinguals’ expressive vocabulary in L1 but such deficit is attenuated or eliminated when both L1 and L2 words are combined (Junker & Stockman, 2002; Marchman et al., 2009; Pearson et al., 1993).

The present study replicates and extends previous results by comparing reaction time and accuracy in word comprehension between monolinguals and bilinguals using the CCT. Both groups performed similarly with an equivalent proportion of correct responses. The accuracy scores were, as expected, higher than those reported in younger infants (Friend & Keplinger, 2003). There was, however, variability in the scores, which rules out the possibility of a ceiling effect as an explanation for the similar performance between the monolingual and bilingual group. More importantly, measuring reaction time revealed no differences between the two groups on word retrieval. This finding is noteworthy because, to date, only one other study has compared word comprehension in monolingual and bilingual infants, although the focus of the study was on parental report of TEs in receptive vocabulary (De Houwer et al., 2006). Finally, the study demonstrates that bilingual infants do not show any delays in receptive vocabulary development in their L1 when it is assessed at an age when comprehension is well developed and when it is measured using a laboratory-based test.

The strong concurrent relation between measures of receptive vocabulary size from the CCT and parental report of productive L1 and of total vocabulary is an important methodological contribution to research on early bilingual language acquisition. It provides an alternative to obtaining data from parent reports, it offers a more objective measure of children’s language development, and it extends assessment of children’s vocabulary into the more subtle domain of comprehension. The finding that the CCT is sensitive to lexical comprehension of individual items in bilinguals confirms that parents’ inferences about their infant’s lexicon are not underestimated if word comprehension tasks are sufficiently stringent (Houston-Price et al., 2007; Styles & Plunkett, 2009). To date, the convergent validity of the CCT with parental report has been restricted to monolingual infants’ receptive vocabulary (Friend & Keplinger, 2003). Having demonstrated that this test can be used with a bilingual population, we believe that it may be used in addition to assessments based on parental report. Bilingual infants were only tested in their L1 on the CCT and it would be important for future research to examine the consistency in lexical access across L1 and L2 in such young children. As well, it would be equally important to examine the relationship between receptive vocabulary as measured by the CDI, and performance on the CCT.

The present results also provide new insight into the relation between language exposure and lexical development in very young bilinguals. First, our findings confirm the expected link between exposure and lexical development. The amount of L2 exposure was related to the proportion of L2 vocabulary and not to total vocabulary. This is consistent with studies showing that the quantity of exposure matters in early bilingual language acquisition (David & Wei, 2008; Pearson et al., 1997). This relation between exposure and bilingual development is more complex; however, as shown by the finding that exposure to L2 was not strongly correlated to the proportion of TEs in bilingual infants. Furthermore, a more balanced exposure does not systematically lead to a higher proportion of TEs. To date, only one study has reported a significant relationship between exposure and TEs but the correlation was based on a small sample of 13 children who each provided multiple data points (David & Wei, 2008). Thus, although a balanced language exposure is likely to generate a balanced vocabulary, our results indicate that a balanced vocabulary does not strongly predict a high proportion of TEs. A possible explanation for this finding may be that bilingual infants are exposed to their languages in different environments. The words acquired in these environments are therefore context-specific and reduces a child’s number of TEs. No doubt, future research examining TEs on larger samples will be needed to clarify this issue.

An important result is the correlation between the proportion of TEs and accuracy and reaction time on the CCT. The positive relation between the proportion of TEs and accuracy was expected since the presence of a large number of TEs was linked to a large total vocabulary (L1 and L2 combined). This may explain why the correlation between the proportion of TEs and accuracy was no longer significant when total vocabulary was partialled out. More importantly, the more TEs children had in their vocabulary, the faster they retrieved the target words on the CCT task, as measured by the latency to touch the correct image. Moreover, the relation between reaction time on the CCT and the percentage of TEs was robust and independent of total vocabulary. This suggests that the TE distracter (TE in competing language) acts as an identity prime at the semantic level even in very young bilinguals. To our knowledge, this is the first study to show that TEs facilitate and do not inhibit lexical retrieval in bilingual toddlers. This result speaks against the competition hypothesis in lexical retrieval because knowledge of the TE distracter does not seem to create interference, at least in these early stages of vocabulary acquisition. If TEs created interference, then reaction time would be higher for those infants who have more TEs. This facilitation has been well documented in adult bilinguals and has been accounted for by the distractor’s contribution to the activation level of the target through its activation of the shared conceptual node (Finkbeiner, Gollan, & Caramazza, 2006). The fact that a similar facilitatory translation identity effect was found in such young bilinguals is impressive.

In sum, the present results highlight the importance of using various assessments in the study of lexical development of very young monolingual and bilingual children. We observed both similarities and differences in expressive and receptive vocabularies. These similarities were present despite the diverse language backgrounds of our bilingual population. But of course, as we reviewed earlier, bilingualism may also bring different developmental paths than monolinguals as research with older children and adults has shown (Bialystok, 2009). For example, throughout the elementary school years, standardized measures of expressive and receptive vocabulary size reveal a gap between monolingual and bilingual children. In addition, adult bilinguals show poorer accuracy and slower reaction times in picture naming tasks compared to monolinguals. These deficits in lexical access, however, are often reported for sequential bilinguals (bilinguals who learn one language at a time), who tend to be included in the population tested in many studies with older bilinguals. More specifically, sequential bilinguals may demonstrate a different developmental path than simultaneous bilinguals. A full understanding of language development in bilinguals cannot be achieved, as shown in the present study, without multiple measures that assess both production and comprehension at the early stages of lexical development.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research was partially supported by a grant awarded by the Canadian Language and Literacy Research Network to Diane Poulin-Dubois, Ellen Bialystok, and Agnes Blaye, by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council grant (2003-07) to Diane Poulin-Dubois and by grant R01HD052523 from the US National Institutes of Health to Ellen Bialystok.

Footnotes

Note

The results comparing the monolinguals and bilinguals were the same with or without the five children with language pairings other than French and English.

About the authors

Diane Poulin-Dubois is a Professor of Psychology at Concordia University, Montréal, Canada. Her research focuses on the development of language development and social cognition in infancy.

Ellen Bialystok is Distinguished Research Professor of Psychology at York University in Toronto, Canada. Her research investigates the cognitive consequences of bilingualism across the lifespan.

Agnès Blaye is a professor of cognitive developmental psychology at Aix- Marseille University. Her research interests include the development of executive control in children.

Alexandra Polonia is currently a research coordinator in the Concordia Infant Research Laboratory. Her research interests include language development in both monolingual and bilingual infants.

Jessica Yott is currently a doctoral student at Concordia University in Montreal, Canada. Her research interests include the development of language, executive functioning, and Theory of Mind during infancy.

References

- Bialystok E. Bilingualism: The good, the bad, and the indifferent. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2009;12:3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok E, Luk G, Peets KF, Yang S. Receptive vocabulary differences in monolingual and bilingual children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2010;13:525–531. doi: 10.1017/S1366728909990423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch L, Sebastián-Gallés N. Native language recognition abilities in four month-old infants from monolingual and bilingual environments. Cognition. 1997;65:33–69. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(97)00040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch L, Sebastián-Gallés N. Evidence of early language discrimination abilities in infants from bilingual environments. Language and Speech. 2001;2:29–49. doi: 10.1207/S15327078IN0201_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caselli MC, Casadio P. Il primo vocabolario del bambino: Guido all’uso del questionario MacArthur per la valutazione della comunicazione e del linguaggio nei primi anni di vita [The child’s first vocabulary: User’s guide to the MacArthur questionnaire for the evaluation of language and communication in the first years of life] Franco Angeli; Milano: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cobo-Lewis A, Pearson B, Eilers R, Umbel V. Effects of bilingualism and bilingual education on oral and written English skills: A multifactor study of standardized test outcomes. In: Oller DK, Eilers R, editors. Language and literacy in bilingual children. Multilingual Matters; Clevedon, UK: 2002. pp. 64–97. [Google Scholar]

- Costa A, Caramazza A. Is lexical selection language specific? Further evidence from Spanish-English bilinguals. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 1999;2:231–244. [Google Scholar]

- Cromdal J. Childhood bilingualism and metalinguistic skills: Analysis and control in young Swedish-English bilinguals. Applied Psycholinguistics. 1999;20:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Dale PS, Fenson L. Lexical development norms for young children. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 1996;28:125–127. [Google Scholar]

- David A, Wei L. Individual differences in the lexical development of French-English bilingual children. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. 2008;11:598–618. [Google Scholar]

- De Houwer A, Bornstein MH, De Coster S. Early understanding of two words for the same thing: A CDI study of lexical comprehension in infant bilinguals. International Journal of Bilingualism. 2006;10:331–347. [Google Scholar]

- De Houwer A, Bornstein MH, Leach DB. Assessing early communicative ability: A cross-reporter cumulative score for the MacArthur CDI. Journal of Child Language. 2005;32:735–758. doi: 10.1017/s0305000905007026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra AFJ. Bilingual visual word recognition and lexical access. In: Kroll JF, de Groot AMB, editors. Handbook of bilingualism: Psycholinguistic approaches. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2005. pp. 179–201. [Google Scholar]

- Eilers R, Pearson B, Cobo-Lewis A. The social circumstances of bilingualism: The Miami experience. In: McCardle P, Hoff E, editors. Child bilingualism. Multilingual Matters; Clevedon, UK: 2006. pp. 68–90. [Google Scholar]

- Fennell CT, Byers-Heinlein K, Werker JF. Using speech sounds to guide word learning: The case of bilingual infants. Child Development. 2007;78:1510–1525. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenson L, Dale PS, Reznick JS, Thal D, Bates E, Hartung JP, Reilly JS. The MacArthur Communicative Development Inventories: User’s guide and technical manual. Singular Publishing Group; San Diego, CA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Finkbeiner M, Gollan TH, Caramazza A. Lexical access in bilingual speakers: What’s the (hard) problem? Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2006;9:153–166. [Google Scholar]

- Friend M, Keplinger M. An infant-based assessment of early lexicon acquisition. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments and Computers. 2003;35:302–309. doi: 10.3758/bf03202556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friend M, Keplinger M. Reliability and validity of the Computerized Comprehension Task (CCT): Data from American English and Mexican Spanish infants. Journal of Child Language. 2008;35:77–98. doi: 10.1017/s0305000907008264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genesee F. Rethinking bilingual acquisition. In: deWaele JM, editor. Bilingualism: Challenges and directions for future research. Multilingual Matters; Clevedon, UK: 2003. pp. 158–182. [Google Scholar]

- Genesee F, Nicoladis E. Bilingual acquisition. In: Hoff E, Shatz M, editors. Handbook of language development. Blackwell; Oxford, UK: 2007. pp. 324–342. [Google Scholar]

- Gollan TH, Montoya RI, Cera CM, Sandoval TC. More use almost always means smaller a frequency effect: Aging, bilingualism, and the weaker links hypothesis. Journal of Memory and Language. 2008;58:787–814. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollan TH, Montoya RI, Fennema-Notestine C, Morris SK. Bilingualism affects picture naming but not picture classification. Memory & Cognition. 2005;33:1220–1234. doi: 10.3758/bf03193224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DW. Mental control of the bilingual lexico-semantic system. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 1998;1:67–81. [Google Scholar]

- Houston-Price C, Mather E, Sakkalou E. Discrepancy between parental reports of infants’ receptive vocabulary and infants’ behaviour in a preferential looking task. Journal of Child Language. 2007;34:701–724. doi: 10.1017/s0305000907008124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova I, Costa A. Does bilingualism hamper lexical access in highly-proficient bilinguals? Acta Psychologica. 2008;127:277–288. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junker DA, Stockman IJ. Expressive vocabulary of German-English bilingual toddlers. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2002;11:381–394. [Google Scholar]

- Kohnert K, Bates E. Balancing bilinguals II: Lexical comprehension and cognitive processing in children learning Spanish and English. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2002;45:347–359. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/027). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krcmar M, Grela B, Lin K. Can toddlers learn vocabulary from television? An experimental approach. Media Psychology. 2007;10:41–63. [Google Scholar]

- Küntay AC, Acarlar F, Aksu-Koç A, Maviş I, Sofu H, Topbaşet S, Turan F. Turkish Communicative Development Inventory (TİGE) Unpublished manuscript, Koç University; Istanbul, Turkey: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lanvers U. Lexical growth patterns in a bilingual infant: The occurrence and significance of equivalents in the bilingual lexicon. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. 1999;2:30–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mahon M, Crutchley A. Performance of typically-developing school-age children with English as an additional language (EAL) on the British Picture Vocabulary Scales II (BPVS II) Child Language Teaching and Therapy. 2006;22:333–353. [Google Scholar]

- Maital SL, Dromi E, Sagi A, Bornstein MH. The Hebrew communicative development inventory: Language specific properties and cross-linguistic generalizations. Journal of Child Language. 2000;27:43–67. doi: 10.1017/s0305000999004006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchman VA, Fernald A, Hurtado N. How vocabulary size in two languages relates to efficiency in spoken word recognition by young Spanish-English bilinguals. Journal of Child Language. 2009;37:817–840. doi: 10.1017/S0305000909990055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchman VA, Martínez-Sussman C. Concurrent validity of caregiver–parent report measures of language for children who are learning both English and Spanish. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research. 2002;45:993–997. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/080). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattock K, Polka L, Rvachew S, Krehm M. The first steps in word learning are easier when the shoe fits: Comparing monolingual and bilingual infants. Developmental Science. 2010;13:229–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoladis E, Secco G. The role of a child’s productive vocabulary in the language choice of a bilingual family. First Language. 2000;58:3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Oller DK, Eilers RE, editors. Language and literacy in bilingual children. Multilingual Matters; Clevedon, UK: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson J, Pearson BZ. Bilingual lexical development: Influences, contexts, and processes. In: Goldstein G, editor. Bilingual language development and disorders in Spanish-English speakers. Paul Brookes; Baltimore, MD: 2004. pp. 77–104. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson BZ, Fernández S, Lewedag V, Oller DK. Input factors in lexical learning of bilingual infants (ages 10 to 30 months) Applied Psycholinguistics. 1997;18:41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson BZ, Fernández S, Oller DK. Cross-language synonyms in the lexicons of bilingual infants: One language or two? Journal of Child Language. 1995;22:345–368. doi: 10.1017/s030500090000982x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson BZ, Fernández SC, Oller DK. Lexical development in bilingual infants and toddlers: Comparison to monolingual norms. Language Learning. 1993;43:93–120. [Google Scholar]

- Perani D, Abutalebi J, Paulesu E, Brambati S, Scifo P, Cappa SF, Fazio F. The role of age of acquisition and language usage in early, high-proficient bilinguals: An fMRI study during verbal fluency. Human Brain Mapping. 2003;19:170–182. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petitto LA, Katerelos M, Levy B, Gauna K, Tétrault K, Ferraro V. Bilingual signed and spoken language acquisition from birth: Implications for mechanisms underlying bilingual language acquisition. Journal of Child Language. 2001;28:1–44. doi: 10.1017/s0305000901004718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petitto LA, Kovelman I. The bilingual paradox: How signing-speaking bilingual children help us resolve bilingual issues and teach us about the brain’s mechanisms underlying all language acquisition. Learning Languages. 2003;8:5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Portocarrero JS, Burright RG, Donovick PJ. Vocabulary and verbal fluency of bilingual and monolingual college students. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2007;22:415–422. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quay S. The bilingual lexicon: Implications for studies of language choice. Journal of Child Language, 1995;22:369–387. doi: 10.1017/s0305000900009831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransdell SE, Fischler I. Memory in a monolingual mode: When are bilinguals at a disadvantage? Journal of Memory & Language. 1987;26:392–405. [Google Scholar]

- Rosselli M, Ardila A, Araujo K, Weekes VA, Caracciolo V, Padilla M, Ostrosky-Solís F. Verbal fluency and verbal repetition skills in healthy older Spanish-English bilinguals. Applied Neuropsychology. 2000;7:17–24. doi: 10.1207/S15324826AN0701_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schelleter C. The effect of form similarity on bilingual children’s lexical development. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2002;5:93–107. [Google Scholar]

- Styles SJ, Plunkett K. What is “word understanding” for the parent of a one-year-old? Matching the difficulty of a lexical comprehension task to parental CDI report. Journal of Child Language. 2009;36:895–908. doi: 10.1017/S0305000908009264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trudeau N, Frank I, Poulin-Dubois D. Une adaptation en français québécois du MacArthur Communicative Development Inventory [A Quebec-French Adaptation of the MacArthur Communicative Development Inventory] La revue d’orthophonie et d’audiologie. 1999;23:61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Vihman MM, Thierry G, Lum J, Keren-Portnoy T, Martin P. Onset of word form recognition in English, Welsh and English–Welsh bilingual infants. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2007;28:475–493. [Google Scholar]

- Werker JF, Byers-Heinlein K. Bilingualism in infancy: First steps in perception and comprehension. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2008;12:144–151. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan S, Nicoladis E. Finding le mot juste: Differences between bilingual and monolingual children’s lexical access in comprehension and production. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2009;12:323–323. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman FJ, Christakis DA, Meltzoff AN. Media viewing by children under 2 years old. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161:473–479. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.5.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]