Abstract

Objective

Symptoms of bipolar disorder are increasingly recognized among children and adolescents, but little is known about the course of bipolar disorder among adults who experience childhood onset of symptoms.

Methods

We examined prospective outcomes during up to two years of naturalistic treatment among 3,658 adult bipolar I and II outpatients participating in a multicenter clinical effectiveness study, the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Age at illness onset was identified retrospectively by clinician assessment at study entry.

Results

Compared to patients with onset of mood symptoms after age 18 years (n = 1,187), those with onset before age 13 years (n = 1,068) experienced earlier recurrence of mood episodes after initial remission, fewer days of euthymia, and greater impairment in functioning and quality of life over the two-year follow-up. Outcomes for those with onset between age 13 and 18 years (n = 1,403) were generally intermediate between these two groups.

Conclusion

Consistent with previous reports in smaller cohorts, adults with retrospectively obtained early-onset bipolar disorder appear to be at greater risk for recurrence, chronicity of mood symptoms, and functional impairment during prospective observation.

Keywords: age of onset, bipolar disorder, chronicity, depression, maintenance, mania, recurrence

In a large, population-based survey of adults, about half of psychiatric disorders exhibited an onset by age 14 and 75% by age 24 (1). In particular, the retrospective onset of bipolar disorder in childhood and adolescence is increasingly recognized (2, 3), and has been associated with poorer outcomes, and particularly with high rates of recurrence (3–7).

However, little is known about the course of bipolar disorder among adults who experience childhood onset of symptoms. This feature of illness has both clinical and nosological importance. From a clinical perspective, it is of great interest whether early onset has prognostic significance once these individuals reach adulthood, particularly as many individuals with childhood onset do not enter treatment until that time (8, 9). More generally, understanding the adult course may be informative about the continuity—or lack thereof —between the diagnosis made in children and that in adults, given that the clinical presentation among children often differs from that in adults (10). Specifically, children and adolescents with bipolar disorder have been described as having a primarily mixed presentation, high rates of rapid cycling, longer episodes, and frequent switches of polarity (5, 7). One recent prospective cohort study found that 44% of children diagnosed with bipolar I disorder went on to have manic episodes as young adults (11).

Initial studies in adults utilized retrospective assessment of both onset age and illness course (3, 12, 13). To date, two studies have examined prospective outcomes of retrospectively obtained childhood-onset bipolar disorder in adults. The two studies included fewer than 25 subjects and 67 subjects, respectively, with onset before age 13 (8, 14). Importantly, neither study accounted for the potential confounding effects of time since first episode or described recurrences, functional impairment, or quality of life. Furthermore, no study has examined the length of euthymic intervals, which may be especially important in defining a more pernicious course.

The Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) study included longitudinal assessments of mood state and functional status in over 3,500 individuals with bipolar I and II disorder, with up to two years of follow-up (15, 16). We sought to extend cross-sectional findings of a more severe course among individuals with retrospectively obtained childhood onset by examining the prospective course of childhood-, adolescent-, and adult-onset bipolar patients in this cohort. We hypothesized that bipolar patients with childhood onset of mood symptoms would experience shorter periods of euthymia prior to recurrence compared with those with adult-onset symptoms. We further hypothesized that childhood-onset patients would experience a more chronic course, marked by a smaller proportion of days euthymic as well as greater functional impairment during follow-up (17).

Methods

Study overview

STEP-BD was a multicenter study designed to evaluate longitudinal outcomes in individuals with bipolar disorder. The study combined a large, prospective study utilizing a common disease-management model and a series of randomized, controlled trials, which shared a battery of common assessments (16). All participants received standardized ongoing assessment, regardless of whether they were participating in randomized treatment; this report includes data from the prospective naturalistic study only. Subjects were recruited between 1999 and 2005.

Participants

STEP-BD participation was offered to diagnostically eligible patients seeking outpatient treatment at participating sites. To enter STEP-BD, participants were required to be at least 15 years of age and to meet DSM-IV criteria (18) for bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder, cyclothymia, bipolar disorder not otherwise specified (NOS), or schizoaffective disorder, bipolar subtype. Exclusion criteria were limited to unwillingness or inability to comply with study assessments, inability to give informed consent, being non-English speaking, and being an inpatient at time of enrollment, although hospitalized patients could enter STEP-BD following discharge. The study was approved by the human research committees of all participating treatment centers, and oral and written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to participation in study procedures. For participants age 15–17, written assent was obtained, with written informed consent obtained from a parent or legal guardian. The present report includes up to two years of prospective data on all bipolar I and II participants who entered STEP-BD.

Assessments

Treating psychiatrists participated in an accredited continuing medical education program that offered instruction in Model Practice Procedures (MPP) for the routine care of bipolar patients (16). These common procedures included standardized evaluation tools and simple conventions for recording clinical data. Treating psychiatrists were required to demonstrate proficiency in the main evaluation tools: the Affective Disorders Evaluation (ADE), the baseline evaluation assessment, and the Clinical Monitoring Form (CMF), a standardized rating scale and progress note used at every patient visit (19). Further information about STEP methods can be found in Sachs et al. (16).

The ADE (16) utilizes adaptations of the mood and psychosis modules from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (18). It was administered by ADE-certified psychiatrists to all participants at study entry, and was the primary means of establishing diagnosis. The ADE also included systematic assessment of lifetime and recent course of illness based on patient report, including age at onset, number of lifetime prior episodes, proportion of days in each mood state, number of episodes in the prior year, and longest period of euthymia. In particular, age at onset was assessed by, first, systematic inquiry into DSM-IV-defined episodes of mania, hypomania, mixed states, or depression. Subjects were then asked to identify the age at which they first experienced such combinations of symptoms of mania/hypomania or of depression (i.e., not merely onset of any one symptom), with other life events (e.g., grade in school) used if necessary to help determine onset age. Age at first psychiatric contact or treatment was not assessed. Collateral informants and sources of information such as medical records were utilized whenever available.

The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI Version 4.4) (20) was used to confirm bipolar diagnosis and establish comorbid Axis I illness. It was administered by MINI-certified study clinicians on study entry. The MINI is a brief structured interview designed to identify the major Axis I psychiatric disorders in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) (21) and the tenth revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) (22). The MINI has been compared to the DSM-III-R (23) and found to have acceptably high validation and reliability scores (20). The MINI and ADE were completed by different study clinicians, and a consensus diagnosis of one of the eligible bipolar disorders was required on both the ADE and MINI for study entry.

The CMF (16, 19), which collects DSM-IV criteria for depressive, manic, hypomanic, or mixed states, was administered by CMF-certified study clinicians at each follow-up visit to determine current mood state. Data from 94 clinicians completing training and certification on the CMF revealed intraclass correlations for degree of agreement with gold standard ratings on 11 symptoms within the depressive symptom domain, and seven symptoms within the domain of mood elevation ranging from 0.828 to 0.997.

The Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (QLESQ), short form (24), is a 16-item self-report questionnaire assessing enjoyment and satisfaction in a variety of domains of daily functioning, with higher scores indicating greater degree of satisfaction. The QLESQ was completed by the patient on a quarterly basis over the first year, and every six months after that.

The clinician-rated Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation-Range of Impaired Functioning Tool (LIFE-RIFT) (25), a measure of psychosocial/functional impairment, was also administered on a quarterly basis for the first year of the study, and every six months thereafter. Scores for each of the four scored items (work, relationships, recreation, and life satisfaction), indicating the areas of greatest impairment, range from 1 to 5, yielding a total score from 4–20, with higher scores indicating greater impairment.

Intervention

Participants in the Standard Care Pathway of STEP-BD could receive any clinically indicated intervention. As noted above, clinicians were trained to utilize model practice procedures, including evidence-based pharmacology (16). Clinician concordance with medical recommendations contained in contemporary bipolar treatment guidelines for treatment of acute episodes was greater than 80% (26).

Outcomes

While independent study assessments were conducted at fixed intervals (quarterly for Year 1, semiannually thereafter), participants were seen in follow-up as often as clinically indicated. Clinical status was assessed at each follow-up visit with the CMF and was used to define the mood states which represent the primary outcome measure. Remission (defined in other STEP-BD reports as recovery, or durable recovery) was defined as two or fewer syndromal features of mania, hypomania, or depression for at least eight weeks, consistent with standard DSM-IV criteria for partial or full remission and with criteria used in the prior NIMH Collaborative Study of Depression (27). Recurrence was defined as meeting full DSM-IV criteria for a manic, hypomanic, mixed, or depressive episode on any one follow-up visit. Occurrence of subsyndromal mood symptoms during follow-up was not considered recurrence.

A measure of proportion of days ‘euthymic’ in the first year was also derived from longitudinal observations, based on proportion of days at which individuals were considered to be in recovery. As patients in this naturalistic study were assessed at variable intervals, estimation of clinical status between visits was required. Assessors were not formally blinded to age of onset data, but were neither routinely aware of this data nor aware of the hypotheses to be tested.

The derivation of this variable was the result of multiple sensitivity analyses examining the possible biasing effects of variable follow-up interval and incorporation of multiple assessment types (28). In brief, the CMF served as the primary source of clinical status information for patients during the longitudinal follow-up, but other sources of information were included in the assignment of ‘percentage of days well’ to provide a continuous record for assignment of daily clinical status. Specifically, the study’s serious adverse event [(SAE), e.g., psychiatric hospitalizations, suicide attempts] log and the Montgomery- sberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (29) and Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) (30) scores from quarterly independent evaluations by trained raters (15) provided additional information for confirmation of the CMF status. Where there was a discrepancy between the CMF score and other assessments, the ‘worst’ score was used (i.e., MADRS or YMRS scores indicative of a mood episode, or a psychiatric hospitalization, were scored as the loss of recovering status). The following imputation procedure was used to assign a count of ‘days well’ over study intervals: when two identical status ratings were present at the beginning and end of any interval of time, each day of that interval was assigned the same clinical status rating. When clinical status differed at the start and end of a time interval, the midpoint of that time interval was defined as the day of change to the new clinical status. Imputation was not applied in examining survival outcomes or any other measures.

Statistical analysis

Consistent with previous work (3, 8), the group was separated into three cohorts—childhood or prepubertal onset (age < 13), adolescent onset (age 13–18), and adult onset (age > 18) —and compared in terms of baseline features and longitudinal outcomes.

The baseline comparisons utilized chi-square or ANOVA with post-hoc pairwise comparisons, as appropriate. Survival analyses, in which age at onset grouping was used to predict time to recurrence, included any subject who achieved at least eight weeks of recovery status (i.e., remission) during the prospective follow-up. Time to an event/censoring was defined as the number of days from baseline (first remission) to the time at first event (recurrence of manic/hypomanic/mixed or depressive episode), calculated from date of completion of the first eight-week period of recovery. For survival analysis only, subjects were censored at the point of their last available CMF assessment within the two years after entering the risk set, or after more than 120 days without a study visit. Groups were compared using the log rank test from Kaplan-Meier survival analysis; follow-up analyses utilized Cox regression with covariates for bipolar I versus II, duration of illness (years since first episode), and mood state at entry (in a mood episode or recovered). To examine clinical variables which might confound the association between onset age and outcome, those variables which differed between age groups were also incorporated individually into Cox regression models.

Comparisons of the three groups on proportion of days well in the first year of follow-up utilized linear regression adjusted for bipolar subtype (I versus II), mood state at study entry (euthymic versus symptomatic), and duration of illness. Modeling of QLESQ and total LIFE-RIFT during two-year follow-up utilized mixed-effects models adjusted for bipolar subtype, mood state at study entry, duration of illness, and baseline QLESQ or LIFE-RIFT score. All analyses utilized Stata 10.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Demographic and diagnostic characteristics

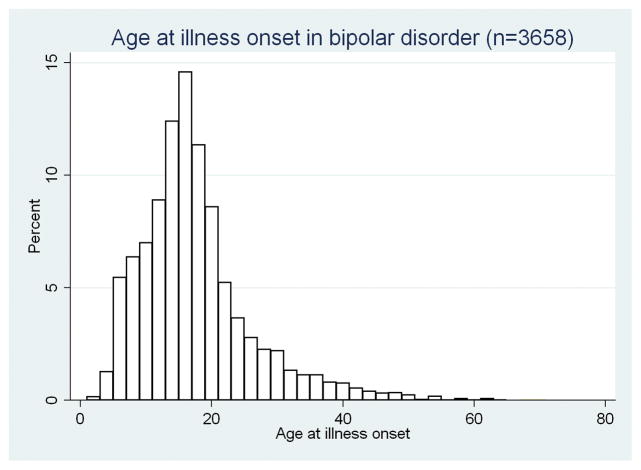

STEP-BD enrolled a total of 4,360 individuals, of whom 4,107 fully completed baseline evaluations; 3,750 (91%) were diagnosed with bipolar I disorder or bipolar II disorder. The remainder, who met criteria for bipolar disorder NOS, cyclothymia, or schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type, were excluded from the present analysis because by definition their mood episodes were briefer or less clearly delineated, and thus onset of mood disorder was more difficult to define. Of the 3,750 individuals identified, age of onset was reported for 3,658, forming the cohort analyzed here, which included 1,068 (29.2%) with childhood/prepubertal onset, 1,403 (38.4%) with adolescent onset, and 1,187 (32.5%) with adult onset. A histogram of onset-age distribution is shown in Figure 1; 2,786 (76.2%) experienced onset before age 21.

Figure 1.

Age at illness onset in bipolar disorder (n = 3,658).

Characteristics of the full STEP-BD cohort by age of onset are presented in Table 1. Consistent with cross-sectional findings from a subset of 1,000 patients (3), subjects with childhood onset were younger and significantly more likely to be female, to have bipolar II disorder, to have rapid cycling in the prior year, and to have substance use disorder and comorbid anxiety disorder in the past year. Those with earlier onset were also less likely to be euthymic at study entry [χ2(2 df) = 72.0, p < 0.001], more likely to be depressed [χ2(2 df) = 10.8, p = 0.004], and more likely to be elevated (hypomanic, manic, or mixed) [χ2(2 df) = 58.1, p < 0.001] . As expected, age at onset was inversely correlated with illness duration (r = −0.34, p < 0.0001). Use of lithium, valproate, or antipsychotics at recovery did not differ significantly between onset-age groups (p ≫ 0.10 for all comparisons).

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline features of onset-age groups (n = 3,658)

| Childhood n (%) | Adolescent n (%) | Adult n (%) | Total n (%) | χ2 (2 df) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 415 (38.9) | 588 (41.9) | 565 (47.6) | 1568 (42.9) | 18.39 | < 0.001 |

| Currently married | 341 (34.5) | 447 (33.9) | 460 (41.4) | 1248 (36.5) | 17.10 | < 0.001 |

| Currently employed | 436 (44.2) | 626 (47.4) | 463 (41.7) | 1525 (44.6) | 8.18 | 0.017 |

| Education (any college, or more) | 82.4 (77.3) | 1112 (84.2) | 943 (84.9) | 2818 (82.4) | 25.51 | < 0.001 |

| Household income > study median | 395 (44.6) | 584 (48.8) | 523 (51.5) | -- | 8.36 | 0.015 |

| Bipolar I | 730 (68.4) | 993 (70.8) | 878 (74) | 2601 (71.1) | 8.75 | 0.013 |

| Caucasian | 952 (89.1) | 1266 (90.2) | 1062 (89.5) | 3280 (89.7) | 0.86 | 0.65 |

| Current substance use disorder | 198 (18.5) | 239 (17) | 109 (9.2) | 546 (14.9) | 46.73 | < 0.001 |

| Current anxiety disorder | 506 (47.4) | 476 (33.9) | 299 (25.2) | 1281 (35) | 122.82 | < 0.001 |

| Current ADHD | 163 (17.1) | 95 (7.4) | 44 (4.1) | 302 (9.1) | 112.35 | < 0.001 |

| Rapid cyclinga | 636 (59.6) | 652 (46.5) | 381 (32.1) | 1669 (45.6) | 171.44 | < 0.001 |

| History of suicide attempt | 509 (49.3) | 531 (39.0) | 303 (26.0) | 1343 (37.7) | 128.28 | < 0.001 |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | F (2 df) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at entry | 37.35 (12.00) | 36.90 (12.12) | 45.31 (12.58) | 39.76 (12.82) | 180.97 | < 0.001 |

| Age at onset | 8.73 (2.59) | 15.44 (1.68) | 26.61 (8.30) | 17.11 (8.73) | 3658.95 | < 0.001 |

| Days depresseda | 50.61 (27.95) | 43.73 (29.06) | 35.44 (30.25) | 43.04 (29.73) | 74.98 | < 0.001 |

| Days anxiousa | 43.94 (34.12) | 35.14 (33.83) | 26.22 (30.52) | 34.79 (33.59) | 78.57 | < 0.001 |

| Days irritablea | 40.13 (31.47) | 32.27 (30.33) | 23.54 (27.03) | 31.72 (30.34) | 85.36 | < 0.001 |

| Days elevateda | 23.25 (22.61) | 19.74 (20.44) | 16.13 (19.82) | 19.59 (21.08) | 31.75 | < 0.001 |

| Euthymic | 340 (31.84) | 581 (41.41) | 587 (49.45) | 1508 (41.22) | 72.04 | < 0.001 |

| Depressed | 365 (34.18) | 441 (31.43) | 330 (27.80) | 1136 (31.06) | 10.82 | 0.004 |

| Manic/hypomanic/mixed | 220 (20.60) | 187 (13.33) | 113 (9.52) | 520 (14.22) | 58.06 | < 0.001 |

In the past year.

ADHD = attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.

When aligning the columns, please align the left parenthesis.

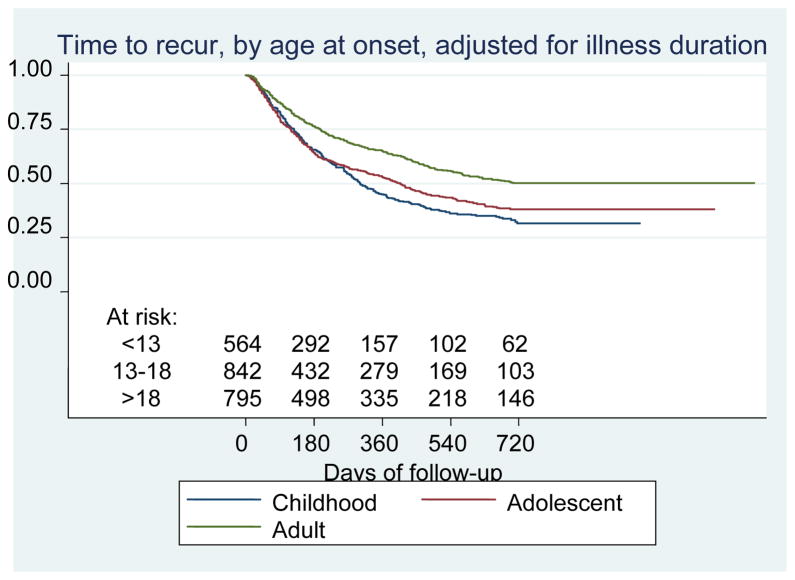

We first examined the hypothesis that those individuals with early onset of bipolar disorder would experience shorter times to recurrence. Figure 2 illustrates the Kaplan- Meier survival curves adjusted for illness duration for the 2,237 subjects, with at least one prospectively observed recovery period of eight or more weeks (i.e., remission). These analyses included a mean of 8.6 visits (SD 6.7, range 2–45) over a mean follow-up of 309 days (median 211 days). Those with childhood onset experienced the earliest recurrence (log-rank χ2 = 14.98, p = 0.0001, childhood versus adult-onset), and those with adolescent onset also experienced recurrence sooner than those with adult onset (χ2 = 6.87, p = 0.01, adolescent versus adult onset). No significant difference was identified between child- and adolescent-onset groups (χ2 = 1.79, p = 0.18). Median days to recurrence were 308, 418, and 542 for the child-, adolescent- , and adult-onset age groups, respectively. In Cox regression adjusting for illness duration and bipolar I versus II status, onset at or before age 18 was associated with earlier recurrence than onset after age 18 [hazard ratio (HR) 1.17 (1.03–1.38)], but onset before 13 did not confer significant additional hazard [HR 1.08 (0.92–1.26)]. In all three groups, the majority of recurrences were major depressive episodes [74.4%, 74.1%, and 72.1% for child, adolescent, and adult groups, respectively; χ2(2 df) = 0.52, p = 0.78]; manic recurrences comprised 6.9%, 7.4%, and 10.9% of all recurrences in the three groups [χ2(2 df) = 4.16, p = 0.12]; mixed episodes comprised 6.2%, 4.1%, and 4.1% [χ2(2 df) = 2.07, p = 0.36]; and the remainder were hypomanic. Incorporating individual clinical and sociodemographic features which differed significantly between onset-age groups (Table 1) in no case led to a change in HR for recurrence by 10% or greater, suggesting an absence of confounding.

Figure 2.

Time to recurrence of depression, mania, hypomania or mixed episodes during up to two years of follow-up, by retrospectively-obtained onset-age group, adjusted for illness duration.

We next examined the hypothesis that early onset would also be associated with greater chronicity, in terms of proportion of days well in the first year of follow-up. Individuals had a mean of 7.2 visits (SD 5.9) in addition to the baseline and quarterly visits. For childhood-, adolescent-, and adult-onset patients, the percent of days euthymic was 42.0 (SD 0.3), 47.1 (SD 0.3), and 54.0 (SD 0.3), respectively; F (2 df) = 35.9, p < 0.0001. Post hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction indicated significant differences between all three groups (p < 0.001). These differences remained significant (p < 0.05) in a regression model incorporating terms for illness at study entry, illness duration, and bipolar I versus II status (not shown).

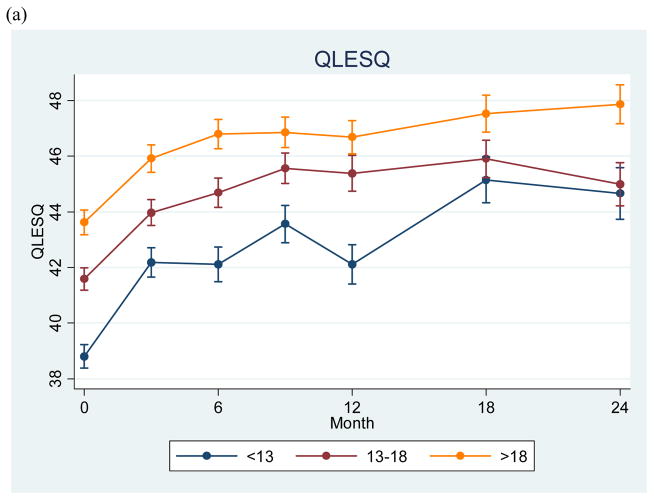

Finally, we examined functional status and quality of life at study entry and quarterly follow-ups over two years (Fig. 3a and 3b). A univariate ANOVA indicated significant differences for LIFE-RIFT total scores at study entry (F = 22.49, p < 0.0001). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons indicated that the childhood-onset and adolescent-onset groups were each more impaired than the adult-onset group (p < 0.0001). The childhood-onset group functioned significantly more poorly than the adolescent-onset group at baseline (p < 0.0001), but the adolescent- and adult-onset groups did not differ significantly (p = 0.13). Likewise, an ANOVA indicated significant differences for QLESQ scores at study entry (F = 24.13, p < 0.0001), with significantly poorer quality of life for the earlier-onset group in all pairwise comparisons (p < 0.0001 for childhood-onset versus the two other groups, p = 0.005 for the adolescent- versus adult-onset group). Differences remained significant (p < 0.05) in regression models after adjustment for illness at study entry, illness duration, and bipolar I versus II status.

Figure 3.

Longitudinal measures of quality of life (A) and functional status (B) among individuals with retrospectively-obtained childhood, adolescent, and adult onset of bipolar disorder.

QLESQ = Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire; LIFE-RIFT = Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation-Range of Impaired Functioning Tool. This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), NIH. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NIMH. This article was approved by the publication committee of the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Individual disclosures are listed before the references.

In mixed-effects regression models, we examined change in LIFE-RIFT and QLESQ scores during 24-month follow-up, adjusting for baseline values as well as bipolar subtype and mood state at study entry. No significant differences in slopes were observed for the three groups (p ≫ 0.05 for childhood- and adolescent-onset groups).

Discussion

This study examined the implication of retrospectively obtained childhood or adolescent onset of illness for prospectively observed course of illness in bipolar disorder, using measures of recurrence, symptom chronicity, and functional impairment/quality of life. We confirmed previous cross-sectional findings indicating a more chronic, severe, and recurrent course for individuals with childhood-onset illness (3–6, 8). During up to two years of prospective follow-up, individuals with childhood onset experienced shorter periods of euthymia than those with adolescent or adult onset. On average, they spent a greater proportion of time symptomatic and experienced poorer functioning and quality of life than those with adult onset. In most respects, the adolescent-onset group was intermediate between the childhood- and adult-onset groups. Moreover, while all three groups experienced some improvement in functioning and quality of life during two-year follow-up, functional outcomes remained poorer in the earlier-onset groups.

These results extend previous reports of poorer outcomes among childhood and adolescent-onset bipolar patients (3–6, 8, 11). They further demonstrate that these outcomes reflect differences both in chronicity—defined as total symptom burden over time—and recurrence. These results are consistent with recent studies that emphasize the chronic as well as the recurrent nature of bipolar illness for many patients (27, 31–34), and further suggest that childhood-onset bipolar disorder patients are at particularly high risk for such a course, consistent with prior findings (8).

A key confounder to consider in adult studies of childhood illness onset is the effect of illness duration. A possible and straightforward explanation for the observed association between early onset and greater morbidity could be that, with greater illness duration, patients accumulate more ‘insults’ (either neurobiologically or psychosocially, or both). This may be particularly the case for individuals with greater delay in treatment initiation (35). However, the observed differences we report here do not appear to be a result of longer illness duration; adjusting for these clinical variables did not meaningfully change the results. Similarly, differences between onset groups persisted despite adjustment for mood state at study entry. We elected to adjust for these features, despite the risk of ‘overcorrecting’ by including proxies for age at onset, to clarify that early onset appears to confer added risk for poor outcomes beyond simply greater risk of illness at study entry or longer illness duration.

We note multiple limitations of this analysis. Most importantly, examining an adult cohort introduces a potential selection bias: individuals whose childhood symptoms resolve, remain mild enough not to seek specialty care in a study such as STEP-BD, or ultimately lead to a different diagnosis would not be represented in the present cohort. This could lead us to overestimate the consequences of childhood-onset illness. Consistent with ascertainment bias, our childhood-onset cohort is predominantly female, while some prospective childhood-onset bipolar cohorts are predominantly male (5). Further, retrospectively obtained age of onset is particularly vulnerable to recall bias, particularly when the interval between symptom onset and assessment may be several decades. To account for this possibility, we included mood state at initial assessment (euthymic versus symptomatic) in all models. If, as our results suggest, early-onset subjects are more likely to be symptomatic at any given time, this approach would lead us to underestimate the association between onset age and outcome. As STEP-BD did not include systematic assessment of age at initial treatment, we were unable to examine the effect of duration of untreated illness (8, 35). Finally, inter-rater reliability of age-at-onset determination was not formally assessed, and subsequent raters were not fully blinded to age of onset, though they were not aware of the hypothesis reported here.

From both a neurobiological and a clinical perspective, the degree of continuity between child- and adult-onset bipolar is a critical question. Neuroimaging studies, for example, suggest areas of overlap as well as discontinuity [for reviews, see DelBello et al. (36) and Strakowski et al. (37)]. Likewise, some interventions may be effective in children as well as adults (38–40), while others differ in effects across ages (41–43). Our findings indicate important differences in clinical outcomes, without clear discontinuities: those with adolescent onset appear to be a more heterogeneous group, resembling adult-onset groups in some respects and early-onset groups in others.

More broadly, these results suggest that a substantial subset of those individuals who go on to have DSM-IV-defined bipolar I or II disorder will have onset in childhood or adolescence. They suggest that individuals with earlier onset may be at risk for a more chronic as well as recurrent course in adulthood, with poorer functioning and quality of life. Finally, they underscore the need to develop better strategies for early identification and early interventions which achieve and maintain symptomatic remission and enhance functioning over the course of development.

Acknowledgments

This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), NIH, Contract N01MH80001 and K23MH067060 (RHP).

Investigators for STEP-BD:

STEP-BD contract: Gary S. Sachs, MD (PI), Michael E. Thase, MD (Co-PI), Mark S. Bauer, MD (Co-PI).

STEP-BD sites and principal investigators:

Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX (Lauren B. Marangell, MD); Case University, Cleveland, OH (Joseph R. Calabrese, MD); Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA (Andrew A. Nierenberg, MD); Portland VA Medical Center, Portland, OR (Peter Hauser, MD); Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA (Terence A. Ketter, MD); University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Denver, CO (Marshall Thomas, MD); University of Massachusetts Medical Center, Worcester, MA (Jayendra Patel, MD); University of Oklahoma College of Medicine, Tulsa, OK (Mark D. Fossey, MD); University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia, PA (Laszlo Gyulai, MD); University of Pittsburgh, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, Pittsburgh, PA (Michael E. Thase, MD); University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX (Charles L. Bowden, MD).

Additional details on past and current participants in STEP-BD can be located at http://www.stepbd.org/research/STEPAcknowledgementList.pdf.

Footnotes

Disclosures

RHP has received research support from Eli Lilly & Co. and Elan/Eisai; has received advisory/consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly & Co., and Pfizer; speaker’s fees or honoraria from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly & Co., GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer; and has equity holdings and patents for Concordant Rater Systems, LLC. MPD has received research support from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly & Co., Johnson & Johnson, Shire, Janssen, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Repligen, Martek, Somerset, NIDA, NIMH, NIAAA, NARSAD, and the Thrasher Foundation; has served on the speakers bureau for Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, and the France Foundation; and has served as a consultant to/advisory board member for or received honoraria from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly & Co., the France Foundation, Kappa Clinical, NIDA, and Pfizer. JRC has received federal funding from the Department of Defense, Health Resources Services Administration, and NIMH; has received grant/research support from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Cephalon, the Cleveland Foundation, Eli Lilly & Co., GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, NARSAD, Repligen, and the Stanley Medical Research Institute; has been an advisory board member for Abbott, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dainippon Sumitomo, Forest, the France Foundation, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, OrthoMcNeil, Repligen, Solvay/Wyeth, and Supernus Pharmaceuticals; and has been involved in CME activities with AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, the France Foundation, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, and Solvay/Wyeth. CLB has received research funding from NIMH, Abbott, GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, and Eli Lilly & Co.; and is a consultant for Abbott, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Sanofi-aventis, and Eli Lilly & Co. MT has served as an advisor or consultant to AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Cyberonics, Eli Lilly & Co., GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, MedAvante, Neuronetics, Novartis, Organon, Sepracor, Shire, Supernus, and Wyeth; has served on the speakers bureaus for AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cyberonics, Eli Lilly & Co., GlaxoSmithKline, Organon, Sanofi-aventis, and Wyeth; has provided expert testimony for Jones Day (Wyeth litigation) and Phillips Lytle (GlaxoSmithKline litigation); is a shareholder with MedAvante; receives income from royalties and/or patents with American Psychiatric Publishing, Guilford Publications, and Herald House; and his spouse is the senior medical director for Advogent. AAN has received grant support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cederroth, Cyberonics, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Lichtwer Pharma, Eli Lilly & Co., NARSAD, NIMH, Pfizer, the Stanley Foundation, and Wyeth-Ayerst; has served as a consultant for Abbott, BrainCells, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GHenaissance, GlaxoSmithKline, Innapharma, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Eli Lilly & Co., Novartis, Pfizer, Sepracor, Shire, and Somerset; and has received honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cyberonics, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly & Co., and Wyeth-Ayerst. GS has received research support from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly & Co., GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Memory Pharmaceuticals, NIMH, Novartis, Pfizer, Repligen, Shire, and Wyeth; has served on the speakers bureaus of Abbott, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly & Co., GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Memory Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi-aventis, and Wyeth; has served as an advisory board member or consultant for Abbott, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, CNS Response, Elan Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly & Co., GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Memory Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Novartis, Organon, Pfizer, Repligen, Sanofi-aventis, Shire, Sigma-Tau, Solvay, and Wyeth; and his spouse is a shareholder with Concordant Rater Systems. EBD, DJM, MO, RA and SRW have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chengappa KN, Kupfer DJ, Frank E, et al. Relationship of birth cohort and early age at onset of illness in a bipolar disorder case registry. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1636–1642. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.9.1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perlis RH, Miyahara S, Marangell LB, et al. Long-Term implications of early onset in bipolar disorder: data from the first 1000 participants in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:875–881. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geller B, Tillman R, Craney JL, Bolhofner K. Four-year prospective outcome and natural history of mania in children with a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:459–467. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.5.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geller B, Craney JL, Bolhofner K, Nickelsburg MJ, Williams M, Zimerman B. Two-year prospective follow-up of children with a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:927–933. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strober M, Schmidt-Lackner S, Freeman R, Bower S, Lampert C, DeAntonio M. Recovery and relapse in adolescents with bipolar affective illness: a five-year naturalistic, prospective follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:724–731. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199506000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birmaher B, Axelson D, Strober M, et al. Clinical course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:175–183. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leverich GS, Post RM, Keck PE, Jr, et al. The poor prognosis of childhood-onset bipolar disorder. J Pediatr. 2007;150:485–490. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.10.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirschfeld RM, Lewis L, Vornik LA. Perceptions and impact of bipolar disorder: how far have we really come? Results of the national depressive and manic-depressive association 2000 survey of individuals with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:161–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anonymous. National Institute of Mental Health research roundtable on prepubertal bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:871–878. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200108000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geller B, Tillman R, Bolhofner K, Zimerman B. Child bipolar I disorder: prospective continuity with adult bipolar I disorder; characteristics of second and third episodes; predictors of 8-year outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:1125–1133. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.10.1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bellivier F, Golmard JL, Henry C, Leboyer M, Schurhoff F. Admixture analysis of age at onset in bipolar I affective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:510–512. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bellivier F, Golmard JL, Rietschel M, et al. Age at onset in bipolar I affective disorder: further evidence for three subgroups. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:999–1001. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.5.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coryell W, Solomon D, Turvey C, et al. The long-term course of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:914–920. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perlis RH, Ostacher MJ, Patel JK, et al. Predictors of recurrence in bipolar disorder: primary outcomes from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:217–224. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sachs GS, Thase ME, Otto MW, et al. Rationale, design, and methods of the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53:1028–1042. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00165-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geller B, Zimerman B, Williams M, et al. Diagnostic characteristics of 93 cases of a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype by gender, puberty and comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2000;10:157–164. doi: 10.1089/10445460050167269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.First MB, Spitzer R, Gibbon M. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sachs GS, Guille C, McMurrich SL. A clinical monitoring form for mood disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2002;4:323–327. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2002.01195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59 (Suppl 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1987. Revised. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, Blumenthal R. Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire: a new measure. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1993;29:321–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leon AC, Solomon DA, Mueller TI, et al. A brief assessment of psychosocial functioning of subjects with bipolar I disorder: the LIFE-RIFT. Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation-Range of Impaired Functioning Tool. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2000;188:805–812. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200012000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dennehy EB, Bauer MS, Perlis RH, Kogan JN, Sachs GS. Concordance with treatment guidelines for bipolar disorder: data from the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2007;40:72–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keller MB, Lavori PW, Coryell W, Endicott J, Mueller TI. Bipolar I: a five-year prospective follow-up. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1993;181:238–245. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199304000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Otto MW, Simon NM, Wisniewski SR, et al. Prospective 12-month course of bipolar disorder in out-patients with and without comorbid anxiety disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:20–25. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.104.007773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Montgomery SA, Åsberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–435. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. A Prospective Investigation of the Natural History of the Long-term Weekly Symptomatic Status of Bipolar II Disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:261–269. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.3.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:530–537. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.6.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tohen M, Hennen J, Zarate CM, Jr, et al. Two-year syndromal and functional recovery in 219 cases of first-episode major affective disorder with psychotic features. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:220–228. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Judd LL, Schettler PJ, Akiskal HS, et al. Residual symptom recovery from major affective episodes in bipolar disorders and rapid episode relapse/recurrence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:386–394. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.4.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldberg JF, Ernst CL. Features associated with the delayed initiation of mood stabilizers at illness onset in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:985–991. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DelBello MP, Adler CM, Strakowski SM. The neurophysiology of childhood and adolescent bipolar disorder. CNS Spectr. 2006;11:298–311. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900020794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strakowski SM, Delbello MP, Adler CM. The functional neuroanatomy of bipolar disorder: a review of neuroimaging findings. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:105–116. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DelBello MP, Kowatch RA, Adler CM, et al. A double-blind randomized pilot study comparing quetiapine and divalproex for adolescent mania. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:305–313. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000194567.63289.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Delbello MP, Schwiers ML, Rosenberg HL, Strakowski SM. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of quetiapine as adjunctive treatment for adolescent mania. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:1216–1223. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200210000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perlis RH, Welge JA, Vornik LA, Hirschfeld RM, Keck PE., Jr Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of mania: a meta-analysis of randomized, placebo–controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:509–516. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Delbello MP, Findling RL, Kushner S, et al. A pilot controlled trial of topiramate for mania in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:539–547. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000159151.75345.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kushner SF, Khan A, Lane R, Olson WH. Topiramate monotherapy in the management of acute mania: results of four double-blind placebo-controlled trials. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8:15–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tramontina S, Zeni CP, Pheula G, Rohde LA. Topiramate in adolescents with juvenile bipolar disorder presenting weight gain due to atypical antipsychotics or mood stabilizers: an open clinical trial. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2007;17:129–134. doi: 10.1089/cap.2006.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]