Abstract

This study was designed to determine whether the relation between parents’ recency of (lifetime) marijuana use (RMU) and their adolescent children’s subsequent marijuana initiation was mediated by the adolescents’ expectancies regarding the consequences of usage, their anticipated severity of punishment for use, and their evaluative attitudes toward marijuana. Parents and their initially marijuana-abstinent adolescent children drawn from the National Survey of Parents and Youth were studied (N = 1399). A bootstrapped multiple mediation analysis tested whether adolescents’ expectations, anticipated punishment, and attitudes toward marijuana collected in the first year of the longitudinal study mediated the relationship between parents’ RMU and their adolescent children’s marijuana initiation one year later. Analysis revealed a statistically significant association between the parental measure and youths’ subsequent initiation (p < .001). The three mediators were related significantly to parents’ RMU and adolescents’ usage. Individually, each variable mediated the association of the parental measure and that of their initially abstinent adolescents when usage was assessed one year later. The results offer insight into the positive association of parents’ RMU with their child’s marijuana use, and provide insights that may be useful in future prevention efforts.

Keywords: adolescent attitudes, marijuana, marijuana usage, expectations, parental behavior

Marijuana is the illicit substance most frequently used by 12–17 year olds in the United States. The 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health revealed that of 7.4% of youths this age had used marijuana (a 10% increase from 2007), and 58.5% of the 2.4 million recent marijuana initiates had not yet reached their 18th birthday (SAMHSA, 2011). Though peers become increasingly influential in adolescence, parents still yield extraordinary sway over their children’s drug use (Andrews, Hops, Ary, Tildesley, & Harris, 1993; Hassandra et al., 2001; Maldonado-Molina, Reingle, Delcher, & Branchini, 2011). Positive parenting, characterized by authoritative parenting practices (i.e., being both warm and demanding), reduces the influence of peer drug use on children’s decisions to use drugs (Dorius, Bahr, Hoffmann, & Harmon, 2004), consistent with Lac and Crano’s (2009) meta-analysis, which revealed that parental monitoring was significantly and inversely associated with adolescent marijuana use.

This is not to suggest that parents’ influence over their children is always beneficial. Parents who currently use drugs are more likely—sometimes up to three times more likely—to have children who also use drugs (Johnson, Shontz, & Locke, 1984; SAMHSA, 2006). Research has yet to determine conclusively why this relationship exists. There may be many indirect paths through which parental drug use influences adolescent behavior. For example, research indicates that parents who use drugs obtain lower scores on such parenting measures as “connectedness & bonding” and “rules setting & discipline” (Brook, Balka, Fei, & Whiteman, 2006; Maalouf, 2010). The current study examines an additional path, one that assesses the association of the recency of parental marijuana use with adolescents’ outcome expectations regarding use, their expected likelihood of punishment, and their attitudes towards marijuana. All of these factors could affect the likelihood of drug initiation.

Outcome expectations (Tolman, 1932, 1959) refer to the perceived positive and negative outcomes associated with engagement in a specific act (e.g., If I smoke marijuana, I will become more social/creative/stupid). They have proven powerful predictors of substance use (Alfonso & Dunn, 2007; Budd, Bleiker & Spencer, 1983; Siegel, Alvaro, Patel, & Crano, 2009; Stacy, Newcomb, & Bentler, 1991). Expectations of physical and social effects predict marijuana use (Skenderian, Siegel, Crano, Alvaro, & Lac, 2008; Stacy, Galaif, Sussman, & Dent, 1996), alcohol use (Brown, 1985; Patrick, Wray-Lake, Finlay, & Maggs, 2010; Stacy et al., 1991), inhalant (Siegel et al., 2008, 2009), and tobacco use (Jøsendal & Aarø, 2012; Halpern-Felsher, Biehl, Kropp, & Rubinstein, 2004). Expectations of outcomes of alcohol use, for example, predict frequency and quantity of drinking over and above demographic factors, previous drinking levels, and alcohol-related attitudes (Carey, 1995); and expectations of inhalant use predict usage over and above demographic variables, prior use, sensation seeking, peer deviance, and parental monitoring (Siegel et al., 2008). If adolescents witness, learn, or infer that a parent used drugs without harmful consequence, they may be less likely to associate usage with negative repercussions.

Current or prior parental usage also may lead adolescents to expect less severe punishment for marijuana initiation. Although there are relatively few studies on perceived parental punishment influencing adolescent drug use per se, evidence suggests that the perception of expected punishment influences children’s social behaviors (Wang, Zhang, Xu, Chen, & Liu, 2007). Theoretically, injunctive norms represent what people perceive as the likely response to their actions (Parsai, Voisine, Marsiglia, Kulis, & Nieri, 2009). Parental injunctive norms represent how adolescents think their parents would react if they discovered their children using drugs (Kulis, Napoli, & Marsiglia, 2002). For adolescents, current (or even past) parental marijuana usage may suggest a weak injunctive norm. If so, they may perceive usage as more acceptable and fear punishment less that those who assume a strong injunction against drug use. Following this logic, parents’ recency of marijuana use (RMU) may be associated with adolescents’ perceptions.

Attitudes, posited as the result of outcome expectations and the value placed on the associated outcome (Ajzen, 2012), also should be affected by parents’ RMU. Attitudes are evaluative integrations of thoughts and feelings experienced with respect to an object (Crano & Prislin, 2006). They have long been associated with intentions and behavior (Ajzen, 2012). Indeed, research has shown that more positive attitudes towards marijuana use were related to marijuana use initiation (Lac, Alvaro, Crano, & Siegel, 2009; Malmberg et al., 2011). It is possible that parents’ RMU is associated with children’s more positive attitudes toward marijuana, which research suggests is an antecedent to use (Ajzen & Fishbein, 2005; Hemovich, Lac, & Crano, 2011; Lac et al., 2009; Sayeed et al., 2005).

This study is designed to investigate the strength of these postulated expectancy-based paths through which parental RMU is associated with children’s marijuana use. We hypothesize that parents’ RMU is linked to adolescents’ expectations and attitudes, which are associated with subsequent marijuana use. We hypothesize a negative relationship between RMU and children’s concern with punishment for marijuana use. These children also will associate marijuana with more favorable outcomes than children of abstinent parents, or those who have used in the more distant (vs. recent) past, and they will hold more favorable attitudes toward the drug. Finally, we posit that adolescents’ outcome expectations, attitudes, and punishment beliefs will be associated with future marijuana use, and that these factors will mediate the relationship between parents’ RMU and their children’s usage.

Method

Data used in this secondary analysis were collected and archived in the National Survey of Parents and Youth (NSPY), a four-year panel survey conducted to evaluate the National Youth Anti-drug Media Campaign (David, Hornik, & Maklan, 2010). The sampling methodology applied in the NSPY was comprehensive, designed to develop a nationally representative sample of children and their parents. Respondents were interviewed four times, at approximately yearly intervals, from November 1999 to June 2004 and received $20 for each interview (see Crano, Siegel, Alvaro, Lac, & Hemovich, 2008, for procedural details).

Respondents

Marijuana-abstinent respondents at the first round of data collection (R1), aged 12 to 17 years, were used in the analysis (172 sample respondents who reported marijuana use at R1 were excluded from the analyses, as the research is concerned with initiation). Nine to 11 year olds also were excluded, as they answered different, abbreviated, surveys. To maximize sample size, data from the first two rounds (R1–R2) of the panel survey were used; respondents 18-year olds at R1 were excluded as they would have aged out of the study before completing R2; 1399 parent-child pairs with complete data across R1 and R2 constituted the respondent sample. Only one parent for each child was interviewed (891 mothers and 508 fathers).

Measures

General marijuana outcome expectations

Eight questions at R1 were used to create an index of expectations toward marijuana use: “How likely is it that the following would happen to you if you used marijuana, even once or twice, over the next 12 months, I would…1. Damage my brain? 2. Mess up my life? 3. Do worse in school? 4. Be acting against my moral beliefs? 5. Lose my ambition? 6. Lose my friend’s respect? 7. Have a good time with my friends? 8. Be more creative and imaginative?” Item responses ranged from 1 (very unlikely) to 5 (very likely), M = 4.14, SD = .87. Items were reflected so that high scores represent negative marijuana outcome expectations. The scale was internally consistent (α = .88).

Expectations of punishment

Adolescents were asked at R1 about the severity of punishment they expected to receive if caught using controlled substances with the following item: “If one of your {parents/caregivers} knew that you used tobacco or alcohol, how likely is it that he or she would punish you in some way?” Response options ranged from 1 (not at all likely) to 5 (very likely). The response distribution for this measure (M = 4.18, SD = .92) was as follows: 1 (n=35), 2 (n=43), 3 (n=88), 4 (n=219), 5 (n=1061). In the absence of questions relating specifically to marijuana, this item served as a proxy for expected parental responses to controlled substance use.

Attitudes toward marijuana use

Two items from R1 were averaged to create a measure of youths’ attitudes toward marijuana use: “Your using marijuana, even once or twice, over the next 12 months, would be…” 1 (extremely bad) to 7 (extremely good) and 1 (extremely unenjoyable) to 7 (extremely enjoyable), r = .62, p < .001; M = 1.41, SD = .89.

Recency of parent marijuana use

RMU use was measured at R1. Parents were asked: “Have you ever, even once, smoked marijuana?” Those responding yes were asked, “How long has it been since you last smoked marijuana?” Responses were coded so that higher scores indicated more recent use. Those answering no received a score of 1 (n = 689); other answers were scored as follows: 2 (yes, more than 20 years ago, n = 297), 3 (yes, 16 to 20 years ago, n = 148), 4 (yes, 11 to 15 years ago, n = 101), 5 (yes, 6 to 10 years ago, n = 61), 6 (yes, 1 to 5 years ago, n = 68), 7 (yes, within the past year, n = 26), or 8 (yes, during the last 30 days, n = 9).

Adolescents’ marijuana use

Adolescents’ use was measured at R2, which was administered approximately one year after R1. The originally abstinent respondents from R1 were asked at R2, “Have you ever, even once, smoked marijuana?” Those responding yes were asked, “How long has it been since you last smoked marijuana?” Those answering no received a score of 1 (n = 1279); other answers were scored as follows: 2 (yes, more than 30 days but within the last 12 months, n = 78), or 3 (yes, during the last 30 days, n = 42). These rates of initiation are in the range of other national studies (SAMHSA, 2011).

Several demographic variables were collected at R1, including the respondent’s age (M = 13.56, SD = 1.45), gender (there were 693 females and 706 males), race/ethnicity (967 respondents were Caucasian; 196 were African American, 185 were Hispanic, and 51 were Asian), and parent’s education (200 less than high school diploma, 466 high school diploma, 380 some college, and 353 college degree).

Results

Entering gender, race, and parent’s education, as well as which parent was interviewed (mother or father) as covariates in the forthcoming regression analyses did not significantly affect the relationship between parents’ RMU and adolescents’ initiation of marijuana use; however, age was significantly associated with R2 marijuana use (r = .12, p < .001) and so was included as a covariate in all analyses. As shown in Table 1, children’s R1 expectations, anticipated punishment, and attitudes toward marijuana were all significantly related (all p < .001) to parents’ RMU scores (also assessed at R1). Direction of all correlations was consistent with hypotheses.

Table 1.

Correlations between child marijuana use, parent marijuana use, expectation of punishment, attitude, and expectations.

| Item | V1 | V2 | V3 | V4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1. Child Marijuana Use | - | |||

| V2. Parent Marijuana Use | .13*** | - | ||

| V3. Punish | −.14*** | −.13*** | - | |

| V4. Attitude | .18*** | .08** | −.19*** | - |

| V5. Expectations | −.13*** | −.07* | .24*** | .34*** |

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

All variables were measured at R1, except Child Marijuana Use, which was measured at R2.

Direct Effects of Parent Lifetime Use/Nonuse

R2 usage of children of lifetime abstinent parents (n = 689) was compared with that of children whose parents had used at some point in the past (n = 710) in a logistic regression analysis. With past usage and youth age entered as predictors, the analysis revealed that children of parents who had ever used marijuana were significantly more likely to use marijuana than children whose parents had never used the substance (B =.851, SE= .18, Wald χ2 = 22.39, df = 1, p <.001, OR = 2.34).

Mediation

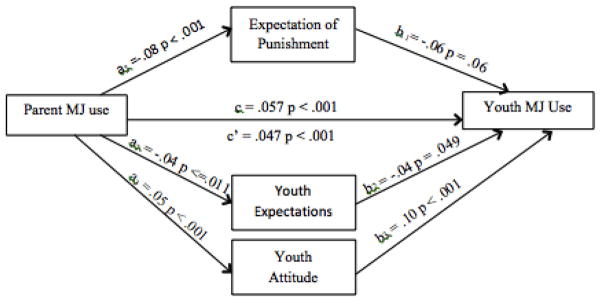

Recency of parents’ marijuana use (RMU) and its association with factors thought to affect adolescents’ usage were investigated in a series of mediation analyses. The mediation of expectations of parental punishment, marijuana outcome expectations, and attitudes on the relationship between parents’ RMU and their children’s marijuana use (with age as a covariate) was assessed using a bootstrapped multiple mediation method (Antonakis, Bendahan, Jacquart, & Lalive, 2010; Bollen, 1987, 1989; Preacher & Hayes, 2004, 2008). In this analysis 20,000 bootstrapped samples were drawn to estimate indirect effects of each of the mediators. Bias corrected and accelerated 95% confidence intervals (CI’s) were computed to determine statistical significance of the ab paths of each mediator. A CI that does not include zero provides evidence of a significant indirect effect, or significant mediation (Preacher & Hayes, 2008; Hayes, 2009). The parent and adolescent use variables were skewed, but the bootstrapped approach adjusts for bias and skewness in the sampling distribution (Antonakis et al., 2010; Preacher & Hayes, 2004, 2008). The results of the mediation model are presented in Figure 1. The point estimates, SE’s and 95% BCa CI are reported in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Mediation Model.

Note. All variables were measured at R1 except Youth Marijuana Use, which was measured at R2, and the effects were controlled for age measured at R1.

Table 2.

Bootstrapped Point Estimate and Confidence Intervals for the Indirect Effect of Expectations of Punishment, Attitude, and Expectations on Child Marijuana Use.

| Point Estimate | SE | BCa 95% CI

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

|

| ||||

| Punishment | .0042 | .0024 | .0007 | .0106 |

| Attitude | .0047 | .0022 | .0015 | .0103 |

| Expectations | .0015 | .0011 | .0001 | .0047 |

| Total Effect | .0104 | .0034 | .0049 | .0183 |

Note. Bca = bias corrected and accelerated.

Total effects

Taken together, adolescents’ attitudes, expectations of parental punishment, and marijuana outcome expectations at R1 significantly mediated the effects of parental RMU on adolescents’ usage initiations at R2. The total effect of RMU on adolescent marijuana use (path c) was statistically significant (b = −.06, se = .011, p < .001). When the three mediators were entered simultaneously, the direct effect (path c) remained significant, (b = −.05, se = .011, p < .001). The total indirect effect through the three mediators (paths a1b1 + a2b2 + a3b3) was the difference between the total and direct effects. The point estimate was .010, and the 95% BCa confidence intervals of .005 to .018 did not include zero, indicating statistically significant partial mediation.

Specific indirect effects

Decomposing the overall mediation model provides more precise information. The directions of paths a1 and b1 for expectations of parental punishment were consistent with the hypothesis that children of parents with lower RMU scores had higher expectations of being punished. The more severe the expected punishment, the less likely were the abstinent adolescents (at R1) to use marijuana one year later. Parental RMU (path a1) significantly predicted children’s expectations of parental punishment (b = −.076, se = .015, p < .001), and expectations of parental punishment (path b1) significantly predicted adolescent marijuana use at R2, (b = −.055, se = .020, p = .006). The indirect effect of expectations of parental punishment had a point estimate of .004; the 95% BCa confidence interval of .001 to .011 did not include zero, demonstrating that expectations of punishment significantly mediated the relationship between parental RMU and adolescent marijuana use.

The directions of paths a2 and b2 for marijuana expectancies revealed a positive association between parents’ RMU and their children’s positive expectations toward usage. Furthermore, the more positive their expectations, the more likely were adolescents to use marijuana one year later. Parental RMU (path a2) was significantly associated with children’s expectancies (b = −.036, se = .014, p = .011), and expectancies (path b3) were significantly linked to adolescent marijuana use at R2 (b = −.043, se = .022, p < .05). The indirect effect of expectancies had a point estimate of .002; the 95% BCa confidence interval of .0001 to .0047 did not include zero, leading to the conclusion that expectancies significantly mediated the relationship between parents’ RMU and adolescent marijuana use.

The directions of paths a3 and b3 for attitudes toward marijuana were consistent with the prediction that children of parents with high RMU scores would express more positive attitudes toward marijuana, and the more positive their attitudes, the more likely they were to use the drug one year later. RMU (path a2) significantly predicted R1 attitudes (b = .049, se = .014, p < .001), and attitudes (path b2) significantly predicted adolescent marijuana use at R2, (b = −096, se = .021, p < .001). The indirect effect of attitude had a point estimate of .005; the 95% BCa confidence interval of .002 to .010 did not include zero. Adolescents’ attitudes toward marijuana mediated the relationship between parents’ and adolescents’ marijuana use.

Discussion

The central goals of the analyses were to determine the association between the recency of parents’ marijuana use (RMU) and their children’s initiation of use, and the factors that mediated the relationship. As shown, if parents had ever used marijuana, the odds of their children initiating the drug’s use were more than twice that of children whose parents had never done so. This result is remarkable insofar as the parents who reported use had, on average, quit between 11 to 20 years prior to the research (Mean RMU was 3.39). Furthermore, the analyses revealed reasons for this significant association, and thus, may contribute to adolescent drug prevention in ways that might benefit future research and applied preventive interventions.

The findings are consistent with, and extend, previous research that indicated an association between parental use and their children’s attitudes toward marijuana (Andrews et al., 1993; LaBrie, Hummer, Lac, & Lee, 2010). These earlier studies, however, were based on convenience samples, and thus were not confidently generalizable to the population at large. The NSPY made use of a nationally representative youth sample, and in addition, allowed for assessment of the effects of the recency of parental marijuana use (RMU), information that was not available in most prior examinations of this issue.

Analysis revealed that the association of parents’ RMU with their children’s marijuana use was mediated by three variables: their children’s general expectations of usage outcomes, attitudes toward marijuana use, and estimates of likely punishment. There is no doubt that teenage drug use is related to many personal and environmental features (Castellanos-Ryan, Rubia, & Conrod, 2011; Ersche, Turton, Pradhan, Bullmore, & Robbins, 2010), but a significant factor in adolescents’ marijuana initiation and use may be the expectations arising from their close and long-term interaction with parents. The implications of this possibility should not be minimized. There may be little we can do to alter behavior that occurred many years in the past, but the effects of that behavior may be attenuated. Making salient to parents the importance of the drug-relevant messages they convey to their children, and the subtle implicit cues of which they must be aware may help reduce the odds of their abstinent children initiating marijuana use. Most parents, for example, are unaware that marijuana’s potency has risen steadily over the past 30 years, as have the drug’s attendant dangers (NIDA, http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/marijuana-abuse/how-does-marijuana-produce-its-effects). This suggests that youth drug prevention efforts may be profitably directed toward parents, who would prove more open and nonreactive than the primary prevention target, their children.

Limitations

As with almost all secondary analyses, the original research instruments and design of the NSPY limited available analyses. The measure of parental marijuana usage, for example, combined recency of use with a dichotomous use/nonuse indicator. The direct effects and RMU analyses, however, helped to offset this limitation. Another limitation was that the survey did not assess adolescents’ knowledge of their parents’ (current or prior) drug use. Even so, the consistency of the results and their fit with expectations suggest that the measures, while improvable, provided important information. The lack of variables specific to the research questions might have attenuated the strength of observed relations, and this could have fostered the relatively small but significant effect sizes across the mediation variables. Recall that in a national sample, even small effects imply large population differences (Derzon & Lipsey, 2002).

Conclusion

It has long been established that children of parents who use drugs are more likely to use drugs themselves. What was less clear was why this relationship held, and what could be done about it. Our research suggests that parental usage and the recency of that use can have an influence on children’s marijuana initiation. Children of more recent parent marijuana users expected less severe reproofs for initiating marijuana use, held more positive outcome expectancies of use, and were more positively attuned to the drug. Given this association of parents’ behavior with their offspring’s marijuana initiation, future adolescent drug prevention interventions might logically be targeted to parents, rather than adolescents, the focal targets of the campaign. Interventions targeting parents have the potential to influence parental attitudes (Summers, Wood, Russell, & MacGill, 2012), thereby altering parental behavior, and may indirectly affect adolescents’ attitudes, as they are less likely to counter-argue messages directed toward parents (Crano, Siegel, Alvaro, & Patel, 2007).

For parents who currently use marijuana, preventive communications should stress the fact that their actions may influence their children’s expectations, attitudes, and ultimately, initiation of marijuana use. If results of the type found in this study were transmitted persuasively, it is conceivable that the ensuing effects on adolescent drug use might prove stronger than those seen in response to prevention campaigns that target the adolescents directly, raising the intriguing possibility that the path to moderating adolescent marijuana use might best run through the parent.

Acknowledgments

The research presented in this article was supported by Grant # 1R01DA030490 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

Footnotes

The contents of the article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of NIDA.

References

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. In: Van Lange PM, Kruglanski AW, Higgins E, editors. Handbook of theories of social psychology. Vol. 1. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Ltd; 2012. pp. 438–459. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. The Influence of Attitudes on Behavior. In: Albarracín D, Johnson BT, Zanna MP, editors. The handbook of attitudes. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2005. pp. 173–221. [Google Scholar]

- Alfonso J, Dunn ME. Differences in the marijuana expectancies of adolescents in relation to marijuana use. Substance use & Misuse. 2007;42:1009–1025. doi: 10.1080/10826080701212386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Hops H, Ary D, Tildesley E, Harris J. Parental influence on early adolescent substance use: Specific and nonspecific effects. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1993;13:285–310. doi: 10.1177/0272431693013003004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Antonakis J, Bendahan S, Jacquart P, Lalive R. On making causal claims: A review and recommendations. The Leadership Quarterly. 2010;21:1086–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.10.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Total, direct, and indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology. 1987;17:37–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Structural equations with latent variables. New York: Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Balka EB, Fei K, Whiteman M. The Effects of Parental Tobacco and Marijuana Use and Personality Attributes on Child Rearing in African-American and Puerto Rican Young Adults. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2006;15:157–168. doi: 10.1007/s10826-005-9010-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA. Expectancies versus background in the prediction of college drinking patterns. Journal of Consulting And Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:123–130. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.53.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd R, Bleiker S, Spencer C. Exploring the use and non-use of marijuana as reasoned actions: An application of Fishbein and Ajzen’s methodology. Drug And Alcohol Dependence. 1983;11:217–224. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(83)90081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB. Alcohol-related expectancies predict quantity and frequency of heavy drinking among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1995;9:236–241. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.9.4.236. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos-Ryan N, Rubia K, Conrod PJ. Response inhibition and reward response bias mediate the predictive relationships between impulsivity and sensation seeking and common and unique variance in conduct disorder and substance misuse. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2011;35:140–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crano WD, Prislin R. Attitudes and persuasion. Annual Review Of Psychology. 2006;57:345–374. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crano WD, Siegel JT, Alvaro EM, Lac A, Hemovich V. The at-risk marijuana nonuser: Expanding the standard distinction. Prevention Science. 2008;9:129–137. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0090-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crano WD, Siegel JT, Alvaro EM, Patel NM. Overcoming adolescents’ resistance to anti-inhalant appeals. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:516–524. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.4.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David S, Hornik R, Maklan D. National Survey of Parents and Youth (NSPY), 1998–2004 -- Restricted Use Files [Computer file]. ICPSR27868-v1. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]; 2010. 2010-06-17. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Derzon JH, Lipsey MW. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of mass-communication for changing substance-use knowledge, attitudes, and behavior. In: Crano WD, Burgoon M, editors. Mass Media and Drug Prevention: Classic and Contemporary Theories and Research. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 231–258. [Google Scholar]

- Dorius CJ, Bahr SJ, Hoffmann JP, Harmon E. Parenting practices as moderators of the relationship between peers and adolescent marijuana use. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:163–178. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00012.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ersche DD, Turton AJ, Pradhan S, Bullmore ET, Robbins TW. Drug addiction endophenotypes: Impulsive versus sensation-seeking personality traits. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;68:770–773. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenblatt J. Adolescent self-reported behaviors and their association with marijuana use. SAMHSA. National Household Survey on Drug Abuse 1994–1996 1998 [Google Scholar]

- Halpern-Felsher BL, Biehl M, Kropp RY, Rubinstein ML. Perceived risks and benefits of smoking: Differences among adolescents with different smoking experiences and intentions. Preventive Medicine: An International Journal Devoted To Practice And Theory. 2004;39:559–567. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassandra M, Vlachopoulos SP, Kosmidou E, Hatzigeorgiadis A, Goudas M, Theodorakis Y. Predicting students’ intention to smoke by theory of planned behaviour variables and parental influences across school grade levels. Psychology & Health. 2011;26:1241–1258. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2011.605137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, Preacher KJ. Quantifying and testing indirect effects in simple mediation models when the constituent paths are nonlinear. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2010;45:627–660. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2010.498290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemovich V, Lac A, Crano WD. Understanding early-onset drug and alcohol outcomes among youth: The role of family structure, social factors, and interpersonal perceptions of use. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2011;16:249–267. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2010.532560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobus JJ, Bava SS, Cohen-Zion MM, Mahmood OO, Tapert SF. Functional consequences of marijuana use in adolescents. Pharmacology, Biochemistry And Behavior. 2009;92:559–565. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson GM, Shontz FC, Locke TP. Relationships between adolescent drug use and parental drug behaviors. Adolescence. 1984;19:295–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jøsendal O, Aarø LE. Adolescent smoking behavior and outcome expectancies. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 2012;53:129–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2011.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulis S, Napoli M, Marsiglia FF. Ethnic pride biculturalism, and drug use norms of urban American Indian adolescents. Social Work Research. 2002;26:101–113. doi: 10.1093/swr/26.2.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Lac A, Lee CM. Direct and indirect effects ofinjunctive norms on marijuana use: The role of reference groups. Journal Of Studies On Alcohol And Drugs. 2010;71:904–908. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lac A, Alvaro EM, Crano WD, Siegel JT. Pathways from parental knowledge and warmth to adolescent marijuana use: An extension to the theory of planned behavior. Prevention Science. 2009;10:22–32. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0111-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lac A, Crano WD. Monitoring matters: Meta-analytic review reveals the reliable linkage of parental monitoring with adolescent marijuana use. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2009;4:578–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01166.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maalouf WE. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A. 2010. The role of parenting skills in the intergenerational transmission of marijuana use behavior; p. 71. [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado-Molina MM, Reingle JM, Delcher C, Branchini J. The role of parental alcohol consumption on driving under the influence of alcohol: Results from a longitudinal, nationally representative sample. Accident Analysis And Prevention. 2011;43:2182–2187. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmberg M, Overbeek G, Vermulst AA, Monshouwer K, Vollebergh WM, Engels RE. The theory of planned behavior: Precursors of marijuana use in early adolescence? Drug And Alcohol Dependence. 2011;123:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsai M, Voisine S, Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Nieri T. The protective and risk effects of parents and peers on substance use, attitudes, and behaviors of Mexican and Mexican American female and male adolescents. Youth & Society. 2009;40:353–376. doi: 10.1177/0044118X08318117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Wray-Lake L, Finlay AK, Maggs JL. The long arm of expectancies: Adolescent alcohol expectancies predict adult alcohol use. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2010;45:17–24. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agp066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope HG, Jr, Gruber AJ, Hudson JI, Cohane G, Huestis MA, Yurgelun-Todd D. Early-onset cannabis use and cognitive deficits: what is the nature of the association? Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;69:303–310. doi: 10.1016/S0376-8716(08)00334-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/BF03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe DC. The limits of family influence: Genes, experience, and behavior. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Sayeed S, Fishbein M, Hornik R, Cappella J, Ahern RK. Adolescent Marijuana Use Intentions: Using Theory to Plan an Intervention. Drugs: Education, Prevention & Policy. 2005;12:19–34. doi: 10.1080/09687630410001712681. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schweinsburg AD, Brown SA, Tapert SF. The influence of marijuana use on neurocognitive functioning in adolescents. Current Drug Abuse Review. 2008;1:99–111. doi: 10.2174/1874473710801010099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon EE, Mathias CW, March DM, Dougherty DM, Liguori A. Teenagers do not always lie: Characteristics and correspondence of telephone and in-person reports of adolescent drug use. Drug And Alcohol Dependence. 2007;90:288–291. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel JT, Alvaro EM, Crano WD, Skenderian J, Lac A, Patel N. Influencing inhalant intentions by changing socio-personal expectations. Prevention Science. 2008;9:153–165. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0091-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel JT, Alvaro EM, Patel N, Crano WD. “…you would probably want to do it. Cause that’s what made them popular”: Exploring perceptions of inhalant utility among young adolescent non-users and occasional users. Substance Use and Misuse. 2009;44:597–615. doi: 10.1080/10826080902809543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skenderian JJ, Siegel JT, Crano WD, Alvaro EE, Lac A. Expectancy change and adolescents’ intentions to use marijuana. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:563–569. doi: 10.1037/a0013020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squeglia LM, Jacobus J, Tapert SF. The influence of substance use on adolescent brain development. Clinical EEG and Neuroscience Journal. 2009;40:31–38. doi: 10.1177/155005940904000110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacy AW, Galaif ER, Sussman S, Dent CW. Self-generated drug outcomes in high-risk adolescents. Psychology Of Addictive Behaviors. 1996;10:18–27. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.10.1.18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stacy AW, Newcomb MD, Bentler PM. Cognitive motivation and drug use: A 9-year longitudinal study. Journal Of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:502–515. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2005 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Office of Applied Studies; Rockville, MD: 2006. NSDUH Series H-30, DHHS Publication No. SMA 06-4194. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MKD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2011. NSDUH Series H-41, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 11-4658. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Summers A, Wood SM, Russell JR, Macgill SO. An evaluation of the effectiveness of a parent-to-parent program in changing attitudes and increasing parental engagement in the juvenile dependency system. Child and Youth Services Review. 2012;34:2036–2041. [Google Scholar]

- Tang Z, Orwin RG. Marijuana initiation among American youth and its risks as dynamic processes: Prospective findings from a national longitudinal study. Substance Use & Misuse. 2009;44:195–211. doi: 10.1080/10826080802347636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapert SF, Granholm E, Leedy NG, Brown SA. Substance use and withdrawal: neuropsychological functioning over 8 years in youth. Journal of International Neuropsychological Society. 2002;8:873–883. doi: 10.1017/S1355617702870011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman EC. Purposive behavior in animals and men. London England: Century/Random House UK; 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Toman EC. Principles of purposive behavior. In: Koch S, editor. Psychology: A study of science. New York: McGraw Hill; 1959. pp. 92–157. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhang Y, Xu Q, Chen S, Liu J. Mediating effect of children’s self-concept on the relationship between parents’ negative punishments and children’s social behaviors. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2007;15:603–605. [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC, Stinchfield RD, Henly GA, Schwartz RH. Validity of adolescent self-report of alcohol and other drug involvement. International Journal of the Addictions. 1990;25:1379–1395. doi: 10.3109/10826089009068469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]