Abstract

Memory B cells formed in response to microbial antigens provide immunity to later infections; however, the inability to detect rare endogenous antigen-specific cells limits current understanding of this process. Using an antigen-based technique to enrich these cells, we found that immunization with a model protein generated B memory cells that expressed isotype-switched immunoglobulins (swIg) or retained IgM. The more numerous IgM+ cells were longer lived than the swIg+ cells. However, swIg+ memory cells dominated the secondary response due to the capacity to become activated in the presence of neutralizing serum Ig. Thus, we propose that memory relies on swIg+ cells until they disappear and serum Ig falls to a low level, in which case memory resides with durable IgM+ reserves.

Memory B cells are generated during the primary immune response to foreign antigens. This process is initiated when naïve B cells expressing surface immunoglobulin (Ig) bind the antigen in secondary lymphoid organs, receive signals from helper T cells, and proliferate (1). This proliferation produces short-lived Ig-secreting plasmablasts and germinal center cells, many of which switch their Ig constant region from IgM to IgG, IgA, or IgE, and acquire somatic mutations in the variable region (1–3). Cells that acquire Ig mutations that improve antigen binding gain a survival advantage and emerge from the germinal center reaction as long-lived surface switched Ig (swIg)+ memory cells, or surface Ig− plasma cells that maintain serum Ig levels (4). Following subsequent exposure to antigen, the memory cells proliferate rapidly and generate plasmablasts, which boost the amount of antigen-specific Ig in the serum to aid in antigen clearance (1, 4). There is, however, evidence for the existence of IgM+ memory B cells that have or have not passed through germinal centers or undergone somatic mutation (5).

Recently, genetic labeling of B cells that expressed activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), which is required for isotype switching and somatic mutation (6), suggested that IgM+ memory cells make up part of the memory B cell pool in mice (7). Whether these cells were antigen-specific was not addressed. Thus, the relative contribution of IgM+ B cells, especially those that may not express AID, to the antigen-specific memory pool remains unclear.

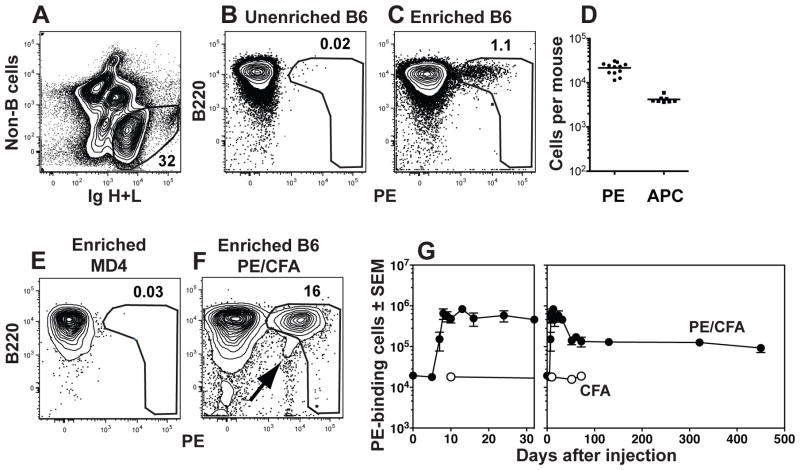

We sought to gain a comprehensive view of all memory B cells in normal mice by tracing the fate of antigen-specific precursors throughout the primary immune response on the basis of antigen-specificity alone without the complications related to the use of Ig transgenic mice (8, 9). Phycoerythrin (PE) and allophycocyanin were chosen as model foreign antigens because their fluorescent properties allowed direct flow cytometric detection of B cells expressing complementary Ig (10, 11). Naïve PE-specific B cells could not, however, be detected in a conventional 106-cell sample of the 2×108 spleen and lymph node cells from a mouse that had never been exposed to PE (Fig. 1A and B). To solve this problem, antigen-specific B cells from the entire spleen and lymph node cell sample were enriched with magnetic beads (12). Naïve PE-specific B cells, mainly of the CD43− CD21− CD23+ B2 phenotype were detected among the cells in a sample that bound to a magnetic column after staining with PE and then anti-PE antibody-coated magnetic beads (Fig. 1C). The unbound cells generated a PE-specific antibody response when transferred into B cell-deficient hosts that was only 20% that of unfractionated spleen and lymph nodes, suggesting that about 80% of the naïve PE-specific B cell population was captured by the enrichment procedure. The PE-specific B cells that were missed may have had Ig that bound PE with very low affinity. The enrichment approach revealed that naïve B6 mice contained about 20,000 PE-specific B cells (Fig. 1D) in the spleen and lymph nodes. In contrast, naïve mice contained only 4,000 B cells specific for allophycocyanin (fig. 1D), demonstrating that pre-immune populations specific for different antigens vary in size. PE-binding cells were not detected in PE-enriched samples from MD4 transgenic mice (13) that contain only monoclonal hen egg lysozyme-specific B cells (fig. 1E), demonstrating the specificity of the enrichment method.

Fig. 1.

Detection of PE-binding B cells. (A) B cells were identified by flow cytometry in spleen and lymph node samples as cells that did not bind a cocktail of antibodies specific for CD4, CD8, CD11c, Gr1, or F480 (non-B cells) and expressed Ig heavy and light chains (H+L, both intracellular and extracellular). The cells with large amounts of Ig are plasmablasts. (B) Representative flow cytometric analysis of unenriched spleen and lymph node B cells from a naïve B6 mouse after staining with PE. (C) Representative flow cytometric analysis of spleen and lymph node B cells from a naïve B6 mouse after staining with PE and enrichment with anti-PE magnetic beads. (D) Number of PE- or allophycocyanin (APC)-specific B cells in individual naïve B6 mice. The bar indicates the mean. (E–F) Representative flow cytometric analysis of spleen and lymph node B cells from a naïve MD4 Rag1−/− mouse (E) or a B6 mouse, 24 days after subcutaneous injection of 15 μg PE and CFA (F), that were stained with PE and enriched with anti-PE magnetic beads. The PE gate was drawn to exclude cells that bind antigen-antibody complexes (arrow in F). (G) Combined data from multiple experiments showing the numbers of PE-binding B cells in the spleen and lymph nodes at the indicated times after subcutaneous injection of 15 μg PE and CFA (filled circles) or CFA alone (open circles) shown over the first 32 (left panel) or 450 (right panel) days. The mean and SEM (N=3–6) is shown for all time points except the day 61 time point for PE and CFA injected mice, where (N=2) and the mean is shown without error bars, and the day 52 and day 72 time points for CFA alone injected mice (N=1). (27)

PE-binding B cells increased dramatically in the draining lymph nodes of B6 mice after subcutaneous injection of PE in complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA), but not CFA alone (Fig. 1F and 1G). Importantly, our gating strategy excluded the B220−, PElow non-B cells (Fig. 1F) that were capable of capturing secreted Igs (14). The PE-specific B cells peaked at ~106 cells by day 13, then declined to a stable population of ~150,000 cells (Fig. 1G).

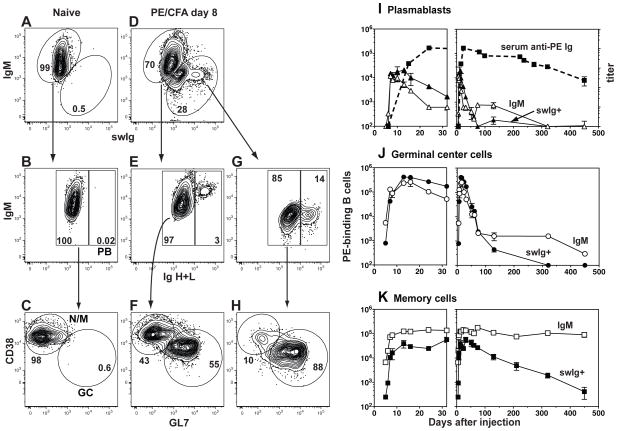

CD38, GL7 and Ig isotype switching were monitored to assess the cell types present in the PE-specific B cell population (15, 16). PE-specific B cells in naïve mice expressed IgM and CD38 but not GL7 and contained low amounts of intracellular Ig as expected for naïve cells (Fig. 2A–C). In contrast, the PE-specific population present 8 days after PE/CFA injection contained subsets that expressed IgM or swIg (Fig. 2D), which could be divided further into intracellular Ighigh plasmablasts (Fig. 2E and G), CD38− GL7+ germinal center cells, and CD38+ GL7− naïve/memory cells (Fig. 2F and 2H).

Fig. 2.

Detection of PE-specific plasmablasts, germinal center cells, and memory B cells. PE-binding cells enriched from the spleen and lymph nodes of (A–C) a naive B6 mouse or (D–H) a B6 mouse on day 8 after subcutaneous injection of PE and CFA, identified as shown in Fig. 1. (A and D) Flow cytometry based gating strategy used to identify cells expressing surface IgM and/or surface and intracellular IgG1, IgG2c, IgG2b, IgG3, IgA, and IgE. (B, E and G) Flow cytometry based gating strategy used to identify Iglow non-plasmablasts (left) or Ighigh plasmablasts (PB) (right) within the IgM+ or swIg+ populations. (C, F and H) Flow cytometry based gating strategy used to identify CD38+ GL7− naive/memory or CD38− GL7+ germinal center (GC) cells within the non-PB populations. (I–K) Combined data from multiple experiments showing the numbers of IgM+ (open symbols, solid line) or swIg+ (filled symbols, solid line) PE-binding plasmablasts (I), germinal center cells (J), or memory cells (K) in the spleen and lymph nodes after subcutaneous injection of PE and CFA on day 0. The mean and SEM (N=3–6) is shown for all time points except days 5, 7, 24, 61, and 74 where (N=2) and the mean is shown without error bars. The mean titer and SEM (N=4–10) of total PE-specific Ig in the serum is shown (dashed line) in (I). (27)

These populations underwent dramatic changes over time. PE-specific plasmablasts, both IgM+ and swIg+, peaked at ~20,000 cells between days 10–13 as PE-specific Ig appeared in the serum, and then declined rapidly by day 30 (Fig. 2I). IgM+ and swIg+ PE-specific germinal center cells peaked on day 13 at 400,000 cells, and declined slowly out to day 100 (Fig. 2J), probably due to the slow release of PE from the CFA emulsion (17).

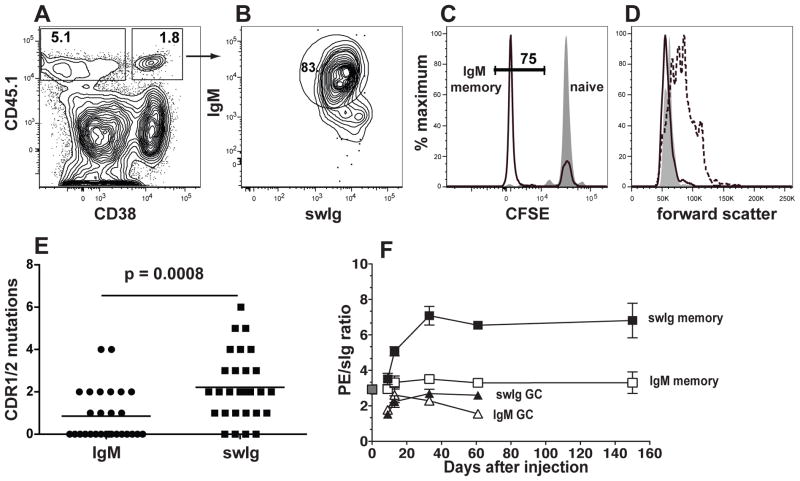

CD38+ GL7− PE-specific swIg+ memory cells were first detected on day 6, peaked on day 30 at ~60,000 cells and declined to very low numbers by day 450 (Fig. 2K). By day 7, CD38+ GL7− PE-specific IgM+ cells began to increase over naïve levels, peaked on day 10 at ~120,000 cells (Fig. 2K) and remained remarkably stable until at least day 450. To confirm that the CD38+ GL7− PE-specific IgM+ cells in primed mice were genuine memory cells, we labeled IgM+ B cells from CD45.1+ naïve mice with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) and transferred them into naïve CD45.2+ hosts to track their division history. Nine days after PE/CFA injection, 75% of the CD45.1+ CD38+ IgM+ PE-specific B cells (Fig. 3A and B) had lost CFSE (Fig. 3C) but were no longer blasts (Fig. 3D). Thus, both populations fit the definition of memory cells (18), having responded to antigenic stimulation, retained CD38 expression, and become quiescent. The difference in the lifespan of the populations could not be explained by differential expression of the survival-promoting BAFFR (19. swIg+ cells, however, had higher amounts of TACI, which may inhibit B cell survival (20).

Fig. 3.

Properties of the PE-specific IgM+ memory B cell population. (A–D) PE-binding cells enriched from B6 recipients of CD45.1+ CFSE-labeled B cells, 9 days after subcutaneous injection of PE and CFA or CFA alone identified as shown in Fig. 1. (A) Flow cytometry based gating strategy used to identify CD45.1+ donor PE-specific B cells that did (right) or did not (left) express CD38. (B) Flow cytometry based gating strategy used to identify CD38+,CD45.1+ PE-specific B cells that expressed IgM. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of CFSE expression in CD45.1+ PE-specific CD38+ IgM+ cells from mice injected with CFA alone (filled) or PE and CFA (black line). The frequency of CFSElow cells is indicated for PE and CFA injected mice. (D) Representative flow cytometric analysis of forward light scatter of PE-specific IgM+ CD38+ naïve cells from mice injected with CFA alone (filled), or PE-specific CD38+ IgM+ memory cells (black line), or CD38− IgM+ cells from mice injected with PE and CFA (dashed line). (E) The number of mutations resulting in amino acid substitutions, in the CDR1 and 2 VH genes for each of 28 PE-binding IgM+ or IgG1+ clones from mice injected 25 days earlier with PE and CFA. Statistical significance was established with an unpaired Student’s t-test. (F) Combined data from two independent experiments showing the ratio of PE fluorescence intensity divided by total Ig fluorescence intensity for naive (grey filled square) IgM+ memory (open squares), swIg+ memory (black filled squares), IgM+ germinal center (open triangles), or swIg+ germinal center (black filled triangles) cells at the indicated times after PE and CFA injection. The mean and SEM (N=3–4) is shown for all time points except day 0 and day 61 where (N=2) and the mean is shown without error bars. (27)

Both swIg+ and IgM+ PE-specific memory cells were T cell dependent. The populations differed, however, in that IgM+ memory cells retained IgD, expressed lower amounts of memory cell surface markers (21, and contained fewer mutations in complementarity determining regions (CDR) 1 and 2 of the heavy chain (Fig. 3E,than swIg+ memory cells. In accordance with the latter finding, swIg+ but not the IgM+ memory cell population underwent affinity maturation manifested by increased PE binding capacity until the germinal center reaction peaked (Fig. 3F). Thus, the IgM+ memory cells showed less evidence of germinal center selection, affinity maturation, and differentiation than swIg+ memory cells.

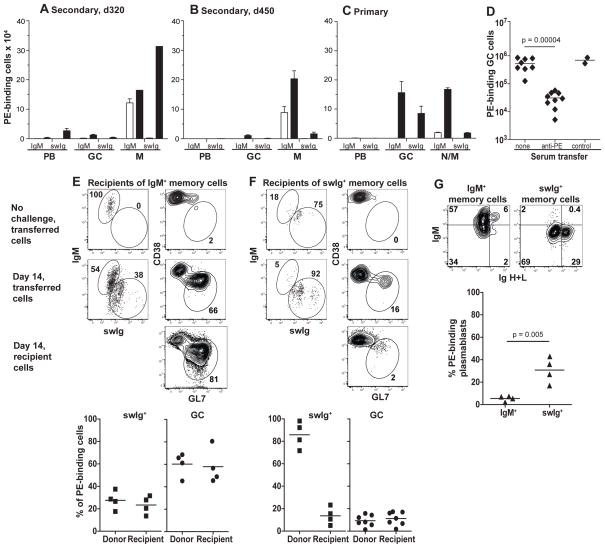

Immunized mice were then challenged with an intraperitoneal injection of PE to assess memory B cell function. Mice that were primed with PE 320 days earlier and contained 100,000 PE-specific IgM+ and 2,000 swIg+ memory cells produced 25,000 swIg+ plasmablasts but very few IgM+ plasmablasts or germinal center cells of either type (Fig. 4A). The number of swIg+ memory cells increased 150-fold over the pre-challenge level, whereas the number of IgM+ memory cells increased less than 2-fold (Fig. 4A). Thus, antigen re-stimulation caused swIg+ memory cells to generate plasmablasts and more memory cells without new germinal center cells, whereas IgM+ memory cells responded poorly.

Fig. 4.

Functional capabilities of memory B cells. (A–D) PE-binding cells enriched from the spleen and lymph nodes of B6 mice and identified as shown in Figs. 1 and 2. (A–C) Closed bars represent the numbers of plasmablasts on day 4 and germinal center cells or memory cells on day 14 after intraperitoneal injection of PE and CFA into day 320 memory (A), day 450 memory (B), or naïve (C) mice. Open bars represent numbers before the intraperitoneal challenge injection. The mean and SEM (N=3–4) is shown for all groups except for the day 320 memory cells after challenge where (N=2) and the mean is shown without error bars (range=102,678). (D) Numbers of PE-binding germinal centers present on day 12–14 in mice left untreated, or injected with serum from mice immunized with PE or control antigens (chicken ovalbumin or allophycocyanin) on days 3–6 after antigen injection. Statistical significance was established with an unpaired Student’s t-test. (E–F) Flow cytometric analysis of PE-specific cells of donor or recipient origin in the spleen and lymph nodes of CD45.1+ recipients of IgM+ (E) or swIg+ (F) CD45.2+ memory cells before and 10–14 days after PE and CFA challenge. Gates used to identify IgM+, swIg+, and germinal center cells are shown. Scatterplots show the percentage of the indicated cell types present in the PE-binding populations of donor or recipient origin in individual mice 10–14 days after PE and CFA challenge. (G) PE-specific cells derived from transferred IgM+ or swIg+ memory cells in individual recipient mice 5 days after PE and CFA challenge. Plasmablasts were identified as Ighigh cells. Statistical significance was established with an unpaired Student’s t-test. (27)

One possibility, however, was that IgM+ memory cells switched Ig isotype after challenge and contributed to the swIg+ progeny. This possibility was difficult to assess as long as swIg+ memory cells were present at the time of challenge. Therefore, the secondary response was tested in mice that were primed with PE 450 days earlier and contained 100,000 PE-specific IgM+ and scarcely any swIg+ memory cells. These mice generated very few swIg+ cells of any kind after challenge, indicating that the IgM+ memory cells did not undergo isotype switching. The IgM+ memory cells increased only 2-fold after challenge (Fig. 4B) in contrast to the robust primary response of naïve IgM+ cells to intraperitoneal injection of PE, which generated many IgM+ and swig+ germinal center and memory cells (Fig. 4C).

Several lines of evidence suggested that the poor secondary response of IgM+ memory cells was related to anti-PE Ig present during challenge. Injection of hyper-immune serum containing anti-PE Ig inhibited the generation of germinal center cells from naïve cells (Fig. 4D). In addition, purified IgM+ memory cells underwent isotype switching and germinal center cell formation when transferred into naïve recipient mice and then challenged with PE (Fig. 4E). In contrast, purified swIg+ memory cells responded to PE in naïve recipient mice as they did in immune mice by producing memory cells but very few germinal center cells (Fig. 4F). Notably, the presence of swIg+ (Fig. 4F) but not IgM+ (Fig. 4E) memory cells inhibited germinal center formation by the naïve cells of the adoptive recipients (Fig. 4F). This inhibitory effect correlated with rapid production of plasmablasts by swIg+ but not IgM+ (Fig. 4G) memory cells after challenge. Thus, IgM+ memory cells were not intrinsically hyporesponsive in immune hosts, but were functionally inhibited by antigen-specific Igs produced either before challenge by plasma cells or after challenge by memory cell-derived plasmablasts. Inhibitory FcγRIIb (22) was probably not involved because IgM+ and swIg+ memory cells expressed equal amounts of this receptor.

PE- and allophycocyanin-specific naïve B cells accounted for about 1:5,000 and 1:25,000 of all B cells in mice. These high frequencies are likely related to the presence of multiple epitopes on these large multimeric proteins (23). It will be of interest to use the enrichment approach to enumerate naïve B cells specific for monomeric antigens, although antigen mulitmerization may be required (24).

Naïve PE-specific B cells generated IgM+ memory cells following immunization with PE and CFA (Fig. 2K) or mixed with lipopolysaccharide or alum, suggesting that this is a general feature of the primary immune response. These memory cells had few mutations in their IgM molecules indicating inefficient selection in germinal centers. It is possible that these poorly mutated IgM molecules had a high enough natural affinity for PE to trigger memory cell differentiation before extensive somatic mutation could occur.

The remarkable stability of the IgM+ memory cells compared to swIg+ memory cells was not related to selective enrichment of IgM+ cells, migration of swIg+ cells to bone marrow, or homeostatic proliferation. The instability of swIg+ memory cells may be related inhibitory signals through TACI20) or deleterious off-target mutations induced by AID (25). Despite being shorter-lived and outnumbered by IgM+ memory cells, swIg+ memory cells dominated the secondary response because of a capacity to be activated in the presence of high affinity neutralizing serum Ig. However, even swIg+ memory cells could not produce germinal center cells perhaps because their plasmablast progeny secreted enough Ig to clear the antigen very quickly. The failure to be activated efficiently in the face of Ig from swIg+ memory cells or plasma cells suggests that IgM+ memory cells do not contribute to the secondary response until these molecules decline. Serum Ig induced by certain subunit vaccines has been reported to fall over time in humans (26), suggesting that IgM+ cells could become the reservoirs of humoral immune memory for these vaccines. Due to their lower affinity and ability to produce germinal center cells, IgM+ memory cells may also be useful for responding to antigenic variants produced by mutating pathogens.

Materials and Methods

Animals

C57BL/6 (B6) mice, Tcra−/− mice, and CD45.1+ congenic (B6. SJL-Ptprca Pep3b/BoyJ) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). MD4 RAG-1−/− mice (1, 2) were bred in a specific pathogen-free facility in accordance with University of Minnesota and NIH guidelines. Six- to 8-week-old, sex-matched mice were used for experiments.

Injections

PE (Prozyme, Hayward, CA) or PE and DVSA GFP (Diversa Corporation, San Diego, CA) were emulsified with CFA (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Mice were immunized by injection of 50 μl of emulsion containing 15 μg of PE or 15 μg of PE and 15 μg of DVSA into a single subcutaneous site at the base of the tail. In another case, 50 μg of PE was mixed with 5 μg of LPS (List Biological, Campbell, CA) and injected intravenously or with 15 μg of PE absorbed to alum and injected intraperitoneally. To measure turnover of memory B cells, previously immunized mice were injected in the peritoneum with 1 mg bromodeoxyduridine (BrdU) (Sigma) and then given 0.8 mg/ml BrdU in their drinking water for 14 days. Fresh BrdU water was provided every 2–3 days. Previously immunized mice, or naïve mice that were adoptively transferred with memory cells, were challenged with an intraperitoneal injection of 60 μg of PE emulsified in CFA in a volume of 200 μl. Hyper-immune serum was generated by injecting mice subcutaneously with 15 μg of PE, allophycocyanin (Prozyme, Hayward, CA) or chicken ovalbumin (Sigma) emulsified in CFA, followed 50–100 days later by an intraperitoneal booster injection of 50 μg of soluble PE, allophycocyanin, or chicken ovalbumin, respectively. Serum was harvested 5–7 days after the boost. Two hundred μl was injected intraperitoneally into mice 3 and 4, or 5 and 6 days after subcutaneous injection of PE and CFA.

PE-enrichment method

Explanted lymph nodes and spleens were minced in collagenase and EDTA as previously described (3, 4). Bone marrow cells were prepared by crushing leg bones with a mortar and pestle in EHAA medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing 5 mM EDTA. All cell suspensions were then passed through fine mesh, washed, and suspended in 0.2 ml of culture supernatant containing 24G2 antibody (ATCC, Manassas, VA) plus 1% rat serum (Sigma) to block Fc receptors, except in experiments were the FcγRIIb was measured. Each sample was incubated with 1 μg PE for 30 minutes at 4°C, washed with sorter buffer (PBS containing 0.1% NaN3 and 2% fetal bovine serum), and then incubated with 25 or 50 μl of anti-PE microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA) for 15 minutes at 4°C. Samples were then washed, suspended in 3 ml of sorter buffer, and passed over magnetized LS columns (Miltenyi Biotech). The columns were washed with sorter buffer to remove unlabeled cells. After the last wash, the columns were removed from the magnetic field, and bound cells were eluted in 5 ml of sorter buffer. A small portion of each eluted sample was removed for a viable cell count. Samples collected at days 6–50 had a significant number of PE-specific cells that were not retained on the column. Thus, at these time points the cell population that flowed through the column was evaluated along with the population that bound the column to ensure that all PE-specific cells in each sample were detected. Allophycocyanin-binding B cells were enriched by a similar procedure except that cells were incubated with allophycocyanin at room temperature.

Flow Cytometry

Antibodies used for flow cytometry were from eBioscience (San Diego, CA) unless otherwise indicated. Cell suspensions were incubated with FITC-labeled anti-GL7 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), PercP-Cy5.5-labeled anti-B220, APC-labeled anti-mouse IgM, Alexa Fluor 700-labeled anti-CD38, and APC-eFluor780-labeled anti-CD4, CD8, F480, CD11c, and Gr-1 antibodies. The cells were then fixed in 2% formaldehyde for 20 minutes in ice, permeabilized with 0.5% saponin (Sigma), and incubated with biotin-labeled anti-IgG1 (A85-1), IgG2c (5.7), IgG2b (R12-3), IgG3(R40-82) (all from BD Biosciences), IgA (RMA-1), and IgE (RME-1) antibodies (both from Biolegend, San Diego, CA) followed by Pacific Blue-labeled streptavidin and Pacific Orange labeled anti-mouse Ig H+L antibody (both from Invitrogen). In some cases, FITC-labeled anti-IgD, CD80, CD73, VLA-4, CD16/32 (BD Biosciences), or CD44 antibodies were used instead of anti-GL7 antibody. In other cases, FITC-labeled anti-B220, PercP-Cy5.5-labeled anti-IgM, and APC-labeled anti-TACI or anti-BAFFR antibodies were substituted for FITC-labeled anti-GL7, PercP-Cy5.5-labeled anti-B220, and APC-labeled anti-mouse IgM antibodies. For detection of BrdU, samples were subjected to an additional fixation with Cytofix/Cytoperm™ (BD Biosciences), followed by incubation with 1 mg/ml DNAse I (Sigma) for 60 minutes at 37°C, culture supernatant containing 24G2 antibody plus 1% rat serum for 10 minutes at 4°C, and FITC-labeled anti-BrdU (BD Biosciences) for 30 minutes at 4°C. For marginal zone and B1 cell detection, cell suspensions were prepared in the absence of collagenase to prevent cleavage of CD23 (5), and incubated with FITC-labeled anti-CD23 antibody (BD), PercP-Cy5.5-labeled anti-B220, APC-labeled anti-CD93, Alexa Fluor 650-labeled anti-IgM, eFluor-450-labeled anti-CD21, biotin-labeled CD43 (BD), and APC-eFluor780-labeled anti-CD4, CD8, F480, CD11c, and Gr-1 antibodies, followed by an incubation with V500-labled streptavidin (BD). The cells were then fixed in 2% formaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.5% saponin (Sigma), and incubated with Alexa Fluor 350-labeled anti-mouse Ig H+L antibody. Flow cytometry was performed on a 4-laser (355nm, 405nm, 488nm, 633nm) LSR II device (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR). Fluorescent AccuCheck counting beads (Invitrogen) were used to calculate total numbers of live lymphocytes in the column bound and flow through suspensions.

Adoptive transfer experiments

PE-depleted B6 spleen and lymph node suspensions were prepared by incubating half of the cells obtained from two pooled mice with 1 μg PE followed by anti-PE microbeads, and passing over a magnetized LS column as described above. The other half of the sample was kept as an undepleted control. Both samples contained similar number of cells, since the PE-depletion column removed less than 1% of the cells. All of the cells from each sample were then injected intravenously into MD4 RAG-1−/− hosts. Purified naïve B cells were prepared from spleen and lymph nodes of CD45.1+ congenic mice with a negative selection kit from Miltenyi Biotech. The B cells were washed in EHAA medium, adjusted to a final concentration of 5×107 cells/ml in EHAA medium, and incubated with 5 μM CFSE (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 10 min at 37°C before they were injected intravenously into B6 mice.

Purified IgM and swIg+ memory cells were prepared from spleen and lymph nodes of B6 mice injected subcutaneously 30–50 days previously with 15 μg PE and CFA. IgM+ memory cells were purified by isolating B cells using a negative selection kit from Miltenyi Biotech, then depleting swIg+ cells, germinal center cells and plasmablasts by incubation with biotin-labeled anti-IgG1, IgG2c, IgG2b, IgG3, IgA, IgE, GL7, and anti-CD138/syndecan-1 (BD) antibodies followed by streptavidin-magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotech). Purified switched memory cells were prepared by depleting IgM+ cells, helper T cells, germinal center cells and plasmablasts by incubation with APC-labeled anti-IgM and FITC-labeled anti-GL7, CD4, and CD138/syndecan-1 (R and D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) antibodies, followed by anti-APC and anti-FITC magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotech). The eluted cells were injected intravenously into CD45.1+ congenic mice.

ELISA

Mouse sera were titrated in 96-well plates coated with 20 μg/ml PE and blocked with 1% BSA. Plate-bound Ig of all isotypes was detected by incubating the wells sequentially with horseradish peroxidase-labeled anti-mouse Ig H+L (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL), and ABTS Peroxidase Substrate (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD). The titer at half-maximal OD 405 was calculated for each sample.

Mutation Analysis

PE-enriched cell suspensions were sorted for CD38+, GL7−, PE-specific cells using a FACSAria (BD Biosciences). Six hundred thousand cells were washed in PBS and frozen at −80°C. RNA was prepared from frozen pellets that were lysed in Trizol (Invitrogen), extracted with chloroform, and applied to an RNAeasy column (Qiagen). cDNA was made from 40 ng of RNA using a high capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (ABI, Carlsbad, CA) as directed by the manufacturer. Degenerate PCR analysis was performed as previously described (6). Briefly, Ig variable regions were amplified from 2 μl of cDNA using rTaq (Takara, Madison, WI) enzyme along with degenerate primers designed to amplify nine of the variable gene families and a specific primer to either Cμ or Cγ1. PCR products were then separated on a 1% agarose gel, and the 500 bp fragments were excised and gel purified (Qiagen). The fragments were then treated with EcoRI and BglII restriction enzymes (NEB, Ipswich, MA), cloned into pBluescript II SK+ using EcoRI and BamHI compatible ends, and sequenced using the T7 primer. Variable genes were identified using the IgBLAST software from the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Student’s t-test was performed to determine statistical significance.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Walter and R. Speier for expert technical assistance and all members of the Jenkins Lab for helpful discussions. This work was supported by grants from the NIH (R01 AI036914 and R37 AI 027998 to M.K.J., F32 AI091033 to J. J. T.), the Cancer Research Institute (J.J.T.), and the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Aging (R.W.M. and P.J.G.).

Footnotes

27. Material and methods available online.

References

- 1.McHeyzer-Williams LJ, McHeyzer-Williams MG. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:487. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tarlinton DM. Immunol Cell Biol. 2008;86:133. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maul RW, Gearhart PJ. Adv Immunol. 2010;105:159. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(10)05006-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoshida T, et al. Immunol Rev. 2010;237:117. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tangye SG, Good KL. J Immunol. 2007;179:13. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muramatsu M, et al. Cell. 2000;102:553. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dogan I, et al. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1292. doi: 10.1038/ni.1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Le TV, Kim TH, Chaplin DD. J Immunol. 2008;181:6027. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tomayko MM, Steinel NC, Anderson SM, Shlomchik MJ. J Immunol. 2010;185:7146. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayakawa K, Ishii R, Yamasaki K, Kishimoto T, Hardy RR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:1379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.5.1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schittek B, Rajewsky K. Nature. 1990;346:749. doi: 10.1038/346749a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin F, Oliver AM, Kearney JF. Immunity. 2001;14:617. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodnow CC, et al. Nature. 1988;334:676. doi: 10.1038/334676a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bell J, Gray D. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1233. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ridderstad A, Tarlinton DM. J Immunol. 1998;160:4688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Todd DJ, et al. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2151. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freund J, Casals J, Hosmer EP. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1937;37:509. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tarlinton D. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:785. doi: 10.1038/nri1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mackay F, Cancro MP. Semin Immunol. 2006;18:261. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seshasayee D, et al. Immunity. 2003;18:279. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson SM, Tomayko MM, Ahuja A, Haberman AM, Shlomchik MJ. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2103. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ravetch JV. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:121. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80168-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu JY, Jiang T, Zhang JP, Liang DC. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:16945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.16945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newman J, Rice JS, Wang C, Harris SL, Diamond B. J Immunol Methods. 2003;272:177. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(02)00499-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hasham MG, et al. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:820. doi: 10.1038/ni.1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amanna IJ, Carlson NE, Slifka MK. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1903. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]