Abstract

Background

Hypertension is the most prevalent comorbidity in individuals with chronic kidney disease (CKD). It is unknown, however, whether the association of the CKD measures, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and albuminuria, with mortality or end-stage renal disease (ESRD) differs by hypertensive status.

Methods

We performed a meta-analysis of 45 cohorts (25 general population, 7 high-risk and 13 CKD cohorts), including 1,127,656 participants (364,344 with hypertension). Adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for all-cause mortality (84,078 deaths from 40 cohorts) and ESRD (7,587 events from 21 cohorts) by hypertensive status were obtained for each study and pooled using random-effects models.

Findings

Low eGFR and high albuminuria were associated with mortality in both non-hypertensive and hypertensive individuals in the general population and high-risk cohorts. Mortality risk was higher in hypertensives as compared to non-hypertensives at preserved eGFR but a steeper relative risk gradient among non-hypertensives than hypertensives at eGFR range 45-75 ml/min/1.73m2 led to similar mortality risk at lower eGFR. With a reference eGFR of 95 mL/min/1.73m2 in each group to explicitly assess interaction, adjusted HR for all-cause mortality at eGFR 45 mL/min/1.73m2 was 1.77 (95% CI, 1.57-1.99) in non-hypertensives versus 1.24 (1.11-1.39) in hypertensives (P for overall interaction =0.0003). Similarly, for albumin-creatinine ratio (ACR) of 300 mg/g (vs. 5 mg/g), HRs were 2.30 (1.98-2.68) in non-hypertensives versus 2.08 (1.84-2.35) in hypertensives (P for overall interaction=0.019). Similar results were observed for cardiovascular mortality. The associations of eGFR and albuminuria with ESRD, however, did not differ by hypertensive status. Results in CKD cohorts were comparable to results in general and high-risk population cohorts.

Interpretation

Low eGFR and elevated albuminuria were more strongly associated with mortality among individuals without hypertension than in those with hypertension, but the associations with ESRD were similar. CKD should be considered at least an equally relevant risk factor for mortality and ESRD in non-hypertensive as it is in hypertensive individuals.

Funding

The US National Kidney Foundation (sources include Abbott and Amgen).

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a major health problem, affecting 10 to 16% of the general adult population in Asia, Europe, Australia and the USA,1-6 and is associated with increased risk of mortality, cardiovascular disease and progression to renal failure.6-10 Reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and elevated albuminuria, the two key kidney measures for CKD definition,1 frequently coexist with traditional cardiovascular risk factors, with hypertension being the most common.5, 11 The prevalence of hypertension ranges from approximately 22% in stage 1 to over 80% in stage 4 CKD.5,11 Prevalence of hypertension increases with both decreased GFR and elevated albuminuria.11 Whereas screening for CKD in the general population setting is a matter of debate,12 screening high-risk individuals such as hypertensives is recommended by current guidelines.13-15

Since hypertension is not only a cause but also a consequence of CKD,16 one may expect that hypertensive individuals encounter a vicious circle of hypertension-CKD interrelation and therefore have stronger CKD-risk associations. Reliable data directly comparing key kidney measures with either mortality or end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in hypertensive versus non-hypertensive individuals, however, is lacking.17 In fact, the presence of CKD has been proposed as a marker of hypertension and other traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes, with questionable relevance in the absence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors.17, 18 Hence, data evaluating associations of reduced eGFR and elevated albuminuria with mortality and ESRD in absence versus presence of hypertension will provide important insights for patient-care and public health. We report results of a large-scale meta-analysis evaluating whether hypertensive status modifies the association of decreased eGFR and increased albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality and ESRD.

Methods

Study selection criteria

Details of the study selection of the Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium (CKD-PC) are presented elsewhere.6-10, 19 Briefly, to be included in the Consortium, a general population or a high-risk cohort (i.e. cohorts selected on the basis of cardiovascular disease or cardiovascular risk factors) had to have at least 1000 participants, with baseline information on estimated GFR (eGFR) and albuminuria, and either mortality or ESRD, with a minimum of 50 events. The eligibility criterion for cohorts enrolling exclusively individuals with CKD was similar, except that studies with fewer than 1000 participants were included. This study was approved by the institutional review board at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Exposures, effect modifier and outcome variables definitions

We used the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation to estimate GFR from age, sex, race, and serum creatinine concentration.20 In studies where serum creatinine was not standardized to isotope dilution mass spectrometry (IDMS), we utilized a previously established calibration factor, that is, reduction of creatinine levels by 5%.21 Albuminuria was ascertained by albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR), urine albumin excretion rate, protein-to-creatinine ratio (PCR) or quantitative dipstick.

Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg, or use of antihypertensive medication in the general and high-risk population cohorts. In primary analyses of CKD cohorts, hypertension status was categorized only by the aforementioned systolic and diastolic blood pressure values, because antihypertensive medication was used in ≥97% of participants in 4 cohorts and information on antihypertensive medication was not available in 1 cohort. Other categorizations of hypertension status used in sensitivity analyses are shown in supplementary Appendix page 40.

Outcomes of interest were all-cause and cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality, and ESRD. Cardiovascular mortality was defined as death due to myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke, or sudden cardiac death. ESRD was defined as start of renal replacement therapy or death coded as due to kidney disease other than acute kidney injury.

Covariates

History of cardiovascular disease was defined as previous myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization, heart failure, or stroke. Diabetes mellitus was defined as fasting glucose concentration ≥7.0 mmol/L (≥126 mg/dL), non-fasting glucose concentration ≥11.1 mmol/L (≥200 mg/dL) or hemoglobin A1c ≥ 6.5%, or use of glucose lowering drugs or self-reported diabetes. Smoking was dichotomized to current smokers versus former or never-smokers. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as body weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Statistical analysis

Investigators from each study were asked to either send individual-level data to the data coordination center (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD) or analyze their data in accordance with an analytical plan using centrally developed statistical code. Subjects with missing values for either eGFR or albuminuria were excluded. Whereas, values of the effect-modifier (hypertensive status or blood-pressure) were not imputed, missing values for all other covariates were imputed using simple mean imputation. The analysis overview and analytic notes for individual studies are described in the supplementary Appendix page 39. Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) of mortality and ESRD associated with eGFR and albuminuria in hypertensive versus non-hypertensive individuals, adjusted for age, sex, race (black vs. non-black), history of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, serum total cholesterol (continuous), BMI (continuous), smoking, and albuminuria (log-transformed ACR or PCR as continuous variables or dipstick proteinuria as categorical variable) for eGFR analysis or eGFR splines for ACR analysis.

In each study, eGFR linear splines (knots at each 15 ml/min/1.73m2 from 30 to 105 ml/min/1.73m2 [90 ml/min/1.73m2 in CKD cohorts]) and their product terms with hypertension were fitted, providing HRs for eGFR (relative to the reference eGFR = 95 mL/min/1.73m2 in general and high risk cohorts and eGFR = 50 mL/min/1.73m2 in CKD cohorts) in both non-hypertensive and hypertensive groups. From this model, the interaction was evaluated as the ratio of HRs in hypertensive versus non-hypertensive at each 1 mL/min/1.73m2 of eGFR from 15 to 120 mL/min/1.73m2 (point-wise interaction). HRs and ratios of HRs for each eGFR value and their standard errors were obtained in each cohort and then pooled using random effects meta-analysis. To assess overall interaction over the total range of eGFR, the coefficients of the product terms of eGFR splines and hypertension status were pooled using inverse-variance weighting. The same approach was applied to ACR risk association, with knots at 10, 30, and 300 mg/g and a reference at ACR = 5 mg/g in the general and high-risk populations and knots at 30, 300, 1000 mg/g and reference at ACR = 100 mg/g in CKD cohorts. Point-wise interaction of the ACR-risk association was assessed at approximate 8% increments of ACR. Finally, to visualize the impact of hypertension on the risk of mortality and ESRD, risk estimates of both hypertensive and non-hypertensive groups were compared to a single reference point of eGFR=95 (50 in CKD cohorts) mL/min/1.73m2 and ACR=5 (100 in CKD cohorts) mg/g of non-hypertensive individuals.

We also performed categorical analyses by comparing the risk in 32 categories of eGFR (<15, 15-29, 30-44, 45-59, 60-74, 75-89, 90-104, ≥105 mL/min/1.73m2) and albuminuria (ACR: <10, 10-29, 30-299, ≥300 mg/g; PCR <15, 15-49, 50-499, ≥500 mg/g; or dipstick test results: negative, trace, 1+, 2+ or more), in general and high-risk cohorts. In CKD cohorts, the categorical analysis was based on 20 categories of eGFR (<15, 15-29, 30-44, 45-74, ≥75 mL/min/1.73m2) and albuminuria (ACR <30, 30-299, 300-999, ≥1,000 mg/g; PCR <50, 50-499, 500-1,499, ≥1,500 mg/g; or dipstick test results: negative/trace, 1+, 2+, 3+ or more).

Heterogeneity of the pooled estimates was assessed by the χ2 test for heterogeneity and the I2 statistic. In all analyses, a P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were done with Stata 11.2 (www.stata.com).

Results

Overall, 742,240 participants without hypertension and 347,256 with hypertension were followed for 6,277,878 and 2,970,318 person-years in the combined general (25 cohorts) and high-risk populations (7 cohorts), respectively (Table 1). In the CKD cohorts, 21,072 participants without hypertension and 17,088 with hypertension were followed for 86,970 and 72,299 person-years, respectively. The mean age of participants and the prevalence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors, especially diabetes, was higher in hypertensive individuals (Table 1 and supplementary Table 1). Due to similarity in range of eGFR and albuminuria (Table 1) and risk, general population and high-risk cohorts were combined in the primary meta-analysis.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of individual studies by hypertensive status.

| Study | Region | N (%HTN) | F/U, yrs | Non-hypertensives | Hypertensives | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Age (SD) | % Female | % Blacks | % DM | SBP mean |

DBP mean |

eGFR mean (SD) |

% Albuminuri¶ | Age (SD) | % Female | % Blacks | % DM | SBP mean |

DBP mean |

eGFR mean (SD) |

% Albuminuri¶ | ||||

| General population | |||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Aichi | Japan | 4731 (26%) | 7.4 | 47 (6.9) | 23% | 0% | 5% | 122 | 75 | 98 (13.5) | 1% | 51 (6.5) | 12% | 0% | 12% | 141 | 88 | 94 (14.5) | 5% |

| ARIC* | USA | 11396 (48%) | 10.6 | 62 (5.6) | 54% | 14% | 11% | 118 | 68 | 86 (13.4) | 4% | 64 (5.7) | 58% | 31% | 23% | 139 | 74 | 83 (17.6) | 14% |

| AusDiab* | Australia | 11134 (33%) | 9.9 | 46 (12.4) | 58% | 0% | 4% | 120 | 67 | 90 (15.3) | 3% | 62 (12.6) | 50% | 0% | 18% | 149 | 77 | 78 (16.8) | 14% |

| Beaver Dam CKD | USA | 4850 (50%) | 11.6 | 59 (10.8) | 55% | 0% | 6% | 119 | 73 | 83 (16.2) | 2% | 65 (10.8) | 57% | 0% | 14% | 145 | 81 | 76 (18.9) | 6% |

| Beijing* | China | 1559 (56%) | 3.9 | 57 (9.6) | 55% | 0% | 21% | 112 | 72 | 87 (13.1) | 3% | 62 (9.0) | 47% | 0% | 33% | 136 | 81 | 81 (14.5) | 8% |

| CHS* | USA | 2980 (64%) | 8.4 | 78 (4.8) | 53% | 10% | 11% | 122 | 66 | 76 (15.4) | 11% | 78 (4.9) | 62% | 20% | 19% | 146 | 72 | 73 (18.3) | 26% |

| CIRCS | Japan | 11871 (36%) | 17.0 | 52 (8.7) | 64% | 0% | 3% | 122 | 75 | 91 (14.4) | 2% | 57 (8.1) | 56% | 0% | 7% | 148 | 89 | 85 (15.2) | 5% |

| COBRA* | Pakistan | 2872 (44%) | 4.1 | 50 (10.0) | 45% | 0% | 16% | 125 | 80 | 106 (14.6) | 5% | 54 (11.2) | 62% | 0% | 28% | 152 | 93 | 100 (19.9) | 15% |

| ESTHER | Germany | 9632 (60%) | 5.0 | 61 (6.6) | 58% | 0% | 15% | 123 | 77 | 84 (20.4) | 8% | 63 (6.5) | 53% | 0% | 22% | 151 | 88 | 84 (20.2) | 15% |

| Framingham* | USA | 2956 (40%) | 10.5 | 56 (9.4) | 56% | 0% | 5% | 119 | 73 | 92 (17.0) | 8% | 63 (8.7) | 49% | 0% | 16% | 143 | 79 | 83 (19.3) | 19% |

| Gubbio* | Italy | 1681 (39%) | 10.7 | 53 (5.7) | 55% | 0% | 4% | 120 | 74 | 85 (11.5) | 2% | 56 (5.3) | 56% | 0% | 8% | 145 | 85 | 83 (11.6) | 8% |

| HUNT* | Norway | 9643 (82%) | 12.0 | 47 (15.4) | 56% | 0% | 19% | 124 | 74 | 102 (17.4) | 4% | 66 (12.2) | 55% | 0% | 17% | 157 | 88 | 81 (18.3) | 14% |

| IPHS | Japan | 95441 (49%) | 14.0 | 56 (10.3) | 70% | 0% | 4% | 121 | 73 | 89 (13.2) | 1% | 63 (9.0) | 61% | 0% | 7% | 147 | 85 | 82 (13.8) | 4% |

| MESA* | USA | 6733 (45%) | 6.2 | 59 (9.9) | 51% | 20% | 8% | 115 | 69 | 85 (14.9) | 4% | 66 (9.5) | 55% | 37% | 19% | 141 | 76 | 78 (17.4) | 16% |

| MRC | UK | 12301 (76%) | 6.4 | 81 (4.7) | 54% | 0% | 7% | 126 | 67 | 59 (14.5) | 7% | 81 (4.3) | 63% | 0% | 8% | 156 | 77 | 57 (14.6) | 8% |

| NHANES III* | USA | 15563 (29%) | 8.5 | 40 (16.8) | 54% | 27% | 7% | 116 | 71 | 107 (21.3) | 7% | 63 (15.6) | 51% | 29% | 24% | 148 | 81 | 83 (23.3) | 24% |

| Ohasama | Japan | 1956 (41%) | 10.4 | 61 (9.9) | 68% | 0% | 9% | 121 | 69 | 85 (12.8) | 6% | 66 (8.6) | 59% | 0% | 11% | 144 | 79 | 80 (13.5) | 11% |

| Okinawa 83§ | Japan | 9556 (40%) | 16.9 | 47 (15.1) | 60% | 0% | N/A | 119 | 74 | 79 (16.0) | 14% | 58 (14.2) | 59% | 0% | N/A | 151 | 89 | 69 (15.9) | 31% |

| Okinawa 93§ | Japan | 93053 (30%) | 6.9 | 52 (15.4) | 59% | 0% | N/A | 119 | 72 | 80 (17.1) | 2% | 62 (12.7) | 53% | 0% | N/A | 148 | 86 | 72 (15.9) | 7% |

| PREVEND* | Netherlands | 8382 (33%) | 9.7 | 45 (10.9) | 54% | 1% | 2% | 119 | 70 | 92 (14.0) | 6% | 58 (11.4) | 41% | 1% | 8% | 150 | 82 | 81 (16.4) | 22% |

| RanchoBernardo* | USA | 1474 (55%) | 10.5 | 65 (11.8) | 59% | 0% | 6% | 120 | 73 | 79 (15.3) | 7% | 75 (10.2) | 61% | 0% | 17% | 148 | 78 | 69 (17.2) | 20% |

| REGARDS* | USA | 27244 (59%) | 5.1 | 63 (9.5) | 53% | 28% | 11% | 119 | 73 | 89 (16.7) | 8% | 66 (9.1) | 55% | 49% | 28% | 134 | 79 | 83 (21.6) | 20% |

| Severance | Korea | 76201 (25%) | 10.0 | 44 (11.0) | 50% | 0% | 4% | 115 | 70 | 92 (14.2) | 4% | 52 (11.6) | 48% | 0% | 11% | 145 | 82 | 84 (15.1) | 9% |

| Taiwan | Taiwan | 515426 (17%) | 8.1 | 39 (12.3) | 51% | 0% | 3% | 114 | 70 | 95 (16.3) | 1% | 55 (13.5) | 48% | 0% | 14% | 152 | 86 | 80 (18.3) | 6% |

| ULSAM* | Sweden | 1102 (75%) | 11.6 | 71 (0.6) | 0% | 0% | 11% | 127 | 76 | 78 (9.5) | 6% | 71 (0.6) | 0% | 0% | 21% | 154 | 86 | 75 (11.0) | 19% |

| High-risk cohorts | |||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| ADVANCE* | Multi | 10595 (83%) | 4.8 | 65 (6.4) | 39% | 0% | 100 % | 124 | 73 | 83 (16.6) | 25% | 66 (6.4) | 43% | 0% | 100% | 149 | 82 | 77 (17.2) | 32% |

| CARE | Canada | 4098 (85%) | 4.8 | 56 (9.5) | 9% | 1% | 9% | 119 | 75 | 80 (15.1) | 8% | 59 (9.3) | 15% | 4% | 15% | 131 | 79 | 75 (16.0) | 14% |

| KEEP | USA | 77895 (66%) | 4.2 | 46 (14.6) | 72% | 28% | 18% | 119 | 74 | 95 (21.1) | 7% | 59 (14.0) | 66% | 33% | 35% | 141 | 82 | 81 (22.8) | 15% |

| KP Hawaii†§ | USA | 38174 (30%) | 2.4 | 58 (14.6) | 51% | 0% | 48% | 123 | N/A | 80 (22.9) | 30% | 61 (14.0) | 50% | 0% | 49% | 156 | N/A | 76 (23.0) | 39% |

| MRFIT | USA | 12854 (66%) | 24.9 | 45 (5.9) | 0% | 4% | 4% | 124 | 82 | 89 (12.6) | 3% | 47 (5.9) | 0% | 9% | 5% | 141 | 95 | 87 (13.4) | 4% |

| Pima* | USA | 5049 (18%) | 13.8 | 30 (12.2) | 60% | 0% | 20% | 115 | 68 | 124 (14.8) | 15% | 45 (15.5) | 40% | 0% | 61% | 141 | 84 | 104 (26.1) | 46% |

| ZODIAC* | Netherlands | 1094 (87%) | 7.9 | 61 (12.9) | 43% | 0% | 100% | 125 | 76 | 82 (17.6) | 21% | 69 (10.8) | 59% | 0% | 100% | 159 | 86 | 69 (17.3) | 42% |

| CKD cohorts‡ | |||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| AASK | USA | 1094 (80%) | 8.8 | 56 (9.6) | 40% | 100% | 0% | 122 | 78 | 45 (13.7) | 48% | 54 (10.9) | 38% | 100% | 0% | 157 | 100 | 46 (14.8) | 65% |

| BC CKD | Canada | 17426 (43%) | 3.3 | 69 14.0) | 45% | 0% | 36% | 124 | 70 | 37 (19.3) | 73% | 69 (13.8) | 45% | 1% | 41% | 154 | 78 | 36 (19.0) | 79% |

| CRIB | UK | 305 (74%) | 6.1 | 57 (15.4) | 29% | 0% | 19% | 127 | 76 | 25 (11.0) | 79% | 64 (13.4) | 36% | 7% | 17% | 162 | 88 | 21 (11.1) | 89% |

| Geisinger (ACR)* | USA | 3290 (31%) | 3.5 | 70 (9.7) | 54% | 1% | 96% | 122 | 68 | 51 (8.0) | 39% | 70 (10.0) | 54% | 2% | 96% | 152 | 77 | 51 (8.8) | 52% |

| Geisinger (Dipstick) | USA | 4294 (34%) | 3.9 | 72 (11.1) | 61% | 1% | 28% | 120 | 68 | 49 (10.2) | 23% | 73 (11.3) | 62% | 1% | 27% | 153 | 78 | 49 (10.9) | 28% |

| GLOMMS-1 (ACR)*§ | UK | 537 (64%) | 4.2 | 74 (10.1) | 51% | 0% | 89% | N/A | N/A | 32 (7.5) | 44% | 72 (10.4) | 51% | 0% | 95% | N/A | N/A | 33 (7.7) | 54% |

| GLOMMS-1(PCR)†§ | UK | 470 (61%) | 4.2 | 73 (15.1) | 50% | 0% | 18% | N/A | N/A | 29 (8.6) | 95% | 68 (15.0) | 46% | 0% | 25% | N/A | N/A | 29 (10.1) | 95% |

| KPNW | USA | 1626 (51%) | 4.6 | 71 (10.0) | 54% | 3% | 39% | 122 | 71 | 46 (11.5) | 29% | 72 (9.6) | 58% | 3% | 39% | 156 | 81 | 46 (11.3) | 33% |

| MASTERPLAN* | Netherlands | 636 (42%) | 4.1 | 59 (13.4) | 34% | 1% | 32% | 123 | 73 | 37 (14.5) | 86% | 63 (10.6) | 26% | 5% | 39% | 155 | 85 | 35 (14.3) | 83% |

| MDRD† | USA | 1730 (39%) | 14.1 | 49 (12.9) | 43% | 9% | 4% | 121 | 77 | 42 (21.6) | 79% | 53 (12.2) | 35% | 17% | 9% | 150 | 89 | 38 (19.9) | 87% |

| MMKD† | Multi | 202 (60%) | 4.0 | 42 (13.5) | 34% | 0% | 0% | 120 | 76 | 54 (33.2) | 94% | 49 (10.3) | 34% | 0% | 0% | 150 | 95 | 43 (26.9) | 96% |

| NephroTest* | France | 900 (40%) | 2.6 | 56 (15.4) | 33% | 10% | 20% | 123 | 70 | 45 (21.9) | 58% | 65 (11.9) | 27% | 8% | 34% | 156 | 82 | 39 (18.4) | 72% |

| RENAAL* | Multiple | 1513 (77%) | 3.1 | 60 (7.9) | 33% | 18% | 100% | 128 | 75 | 43 (13.4) | 100% | 60 (7.3) | 38% | 14% | 100% | 160 | 85 | 40 (13.0) | 100% |

| STENO* | Denmark | 886 (48%) | 8.8 | 41(10.0) | 45% | 0% | 100% | 124 | 74 | 91 (23.3) | 39% | 46 (11.5) | 42% | 0% | 100% | 156 | 85 | 77 (27.0) | 60% |

| Sunnybrook* | Canada | 3251 (45%) | 2.3 | 69(14.7) | 41% | 0% | 50% | 120 | 69 | 38 (15.4) | 81% | 71 (13.1) | 47% | 0% | 54% | 155 | 80 | 36 (15.4) | 88% |

Studies with ACR,

Studies with PCR

In CKD cohorts, definition of hypertension did not incorporate antihypertensive drug use, hypertension was only defined on blood-pressure values ≥140 mmHg systolic and/or ≥90 mmHg diastolic.

Studies using cohort-specific definition for hypertension, see analytic notes in supplementary appendix, page 39.

Proportion of participants with ACR ≥30 mg/g or PCR ≥50 mg/g or dipstick protein ≥1+.

Individual studies acronyms and notes are listed in the supplementary appendix, page 37.

All-cause and cardiovascular mortality

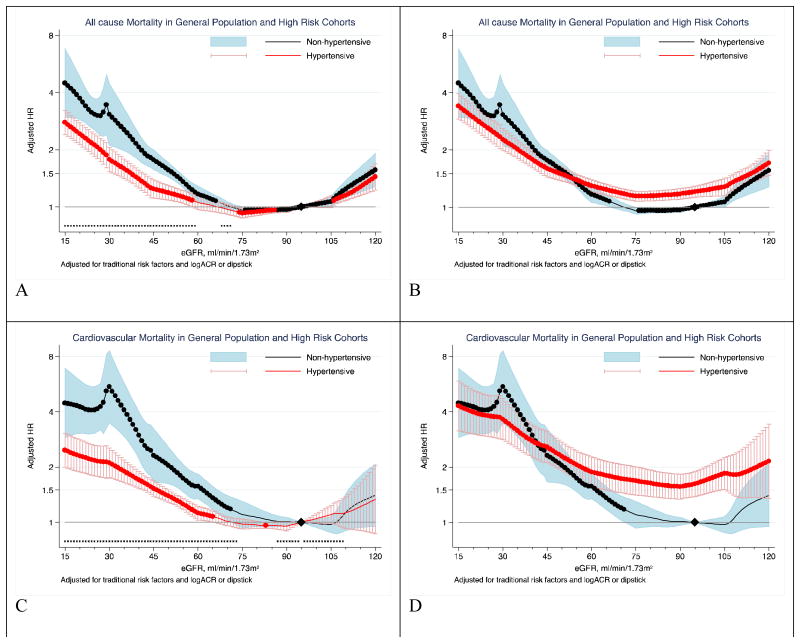

Of the general population and high-risk cohorts, 30 studies had data on all-cause mortality (27,836 deaths [cumulative incidence, 4.1%] in non-hypertensives vs. 47,335 [15.0%] in hypertensives) and 23 studies had data on cardiovascular mortality (6,601 deaths [0.9%] in non-hypertensives vs. 15,634 deaths [6.8%] in hypertensives) (supplemental Table 1). With a reference at eGFR 95 mL/min/1.73m2 among non-hypertensives, hypertensives had a higher risk of mortality in the eGFR range of above ∼55 for all-cause and ∼45 mL/min/1.73m2 for cardiovascular mortality (Figure 1, A and C). However, non-hypertensives demonstrated a steeper relative risk gradient at the eGFR range 45-75 ml/min/1.73m2, and their risk of mortality outcomes was similar or even higher as compared to hypertensives at eGFR below ∼45 ml/min/1.73m2. When separate references were set at eGFR of 95 mL/min/1.73m2 in both hypertensive and non-hypertensive groups to explicitly depict eGFR-hypertension interaction (Figure 1 B and D), significant point-wise interaction at eGFR levels below 59 mL/min/1.73m2 for all-cause mortality and below 73 mL/min/1.73m2 for cardiovascular mortality. The overall interaction of hypertension with eGFR was significant for all-cause mortality (average relative HR for 15ml/min/1.73m2 lower eGFR between hypertensives vs. non-hypertensives 0.95 [95% CI, 0.92-0.98], P for overall interaction = 0.0003) and cardiovascular mortality (average relative HR 0.89 [0.83-0.96], P for overall interaction = 0.0004). Although we observed moderate heterogeneity of the overall interaction for all-cause (I2=56%) and cardiovascular mortality (I2= 66%), most cohorts were in agreement with a weaker association for low eGFR in hypertensives compared to non-hypertensives (relative HR <1.0, supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 1. Hazard ratios of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality according to eGFR in non-hypertensives (black-line) versus hypertensives (red-line).

Panels A through D represents results of all-cause (A and B) and cardiovascular (C and D) mortality in the combined general and high-risk populations. Panels A and C use eGFR of 95 mL/min/1.73m2 among non-hypertensive as a single reference point (diamond) for both hypertensive and non-hypertensive individuals to visualize the main effect of hypertension on risk. Panels B and D use eGFR of 95 mL/min/1.73m2 among hypertensives and non-hypertensives as the reference point (diamond) for hypertensives and non-hypertensives to visualize interaction between eGFR and hypertensive status, respectively.. Significant interaction between hypertension and eGFR is represented by “x” signs on the bottom of the right panels. Hazard ratios were adjusted for age, sex, race, smoking, history of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, serum total cholesterol concentration, body mass index, and albuminuria (log-ACR, log-PCR or categorical dipstick proteinuria [negative, trace, 1+, ≥2+])

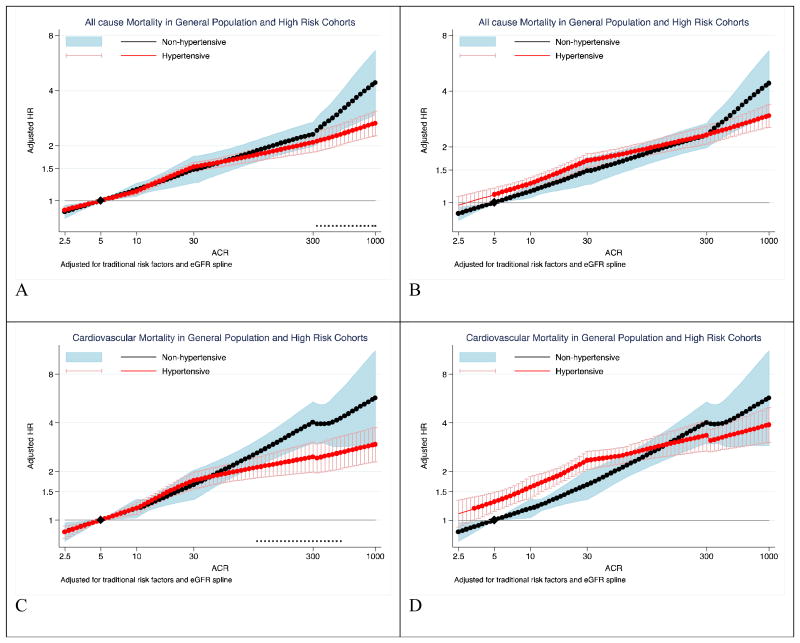

Higher ACR was associated with greater risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among both non-hypertensive and hypertensive individuals (Figure 2). Individuals with hypertension had higher mortality risk compared to those without hypertension at ACR below ∼100 mg/g (Figure 2A and C). However, non-hypertensives had a steeper relative risk gradient in the ACR range >30 mg/g, and their mortality risk was comparable or even higher as compared to hypertensives at ACR values above ∼100 mg/g. With separate references at ACR of 5 mg/g in each group, significant point-wise interaction was observed in the ACR range above 300 mg/g for all-cause mortality and above100 mg/g for cardiovascular mortality (Figure 2 B and D). Overall interaction was significant for all-cause mortality (average relative HR for 10-fold higher ACR 0.91 [95% CI, 0.83-0.98], P for overall interaction = 0.019) but did not reach significance for cardiovascular mortality (0.87 [0.74-1.03], P for overall interaction =0.11). The majority of studies showed a stronger risk association for ACR in non-hypertensives compared to hypertensives with low heterogeneity (I2=14% all-cause mortality and 0% for cardiovascular mortality) (supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 2. Hazard ratios of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality according to ACR in non-hypertensives (black-line) versus hypertensives (red-line).

Panels A through D represents results of all-cause (A and B) and cardiovascular (C and D) mortality in the combined general and high-risk populations. Panels A and C use ACR of 5 mg/g among non-hypertensive as a single reference point (diamond) for both hypertensive and non-hypertensive individuals to visualize the main effect of hypertension on risk. Panels B and D use ACR of 5 mg/g among hypertensives and non-hypertensives as the reference point (diamond) for hypertensives and non-hypertensives to visualize interaction between ACR and hypertensive status, respectively. Significant interaction between hypertension and ACR is represented by “x” signs in the right panels. Hazard ratios were adjusted for age, sex, race, smoking, history of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, serum total cholesterol concentration, body mass index, and eGFR splines.

The risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality increased with lower eGFR and higher albuminuria categories for both non-hypertensive and hypertensive individuals (Table 2). The association of eGFR and albuminuria categories with risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality was generally stronger in non-hypertensives as compared to hypertensives, with significant interaction observed in eGFR categories <60 (<75 for cardiovascular mortality) mL/min/1.73m2 and in the albuminuria category of ACR ≥300 mg/g or dipstick ≥2+. Supplemental Figures 3 through 6 show higher HRs of mortality outcomes in non-hypertensives compared to hypertensives for the eGFR category of 30-44 mL/min/1.73m2 (vs. 90-104) and albuminuria category of ACR ≥300 mg/g or dipstick ≥2+ (vs. ACR<10 or dipstick -), with mild to moderate heterogeneity across cohorts (I2 ranging from 22.5% to 40.1%, P from 0.037 to 0.17).

Table 2. Cross-tabulation of hazard ratios for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality according to eGFR and albuminuria clinical categories by hypertensive status in the combined general and high-risk population cohorts.

| eGFR | Non-hypertensives | Hypertensives | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACR/Dipstick | Overall | ACR/Dipstick | Overall | |||||||

| <10 / Dip “-” | 10-29 / Dip “±” | 30-299 / Dip “1+” | 300+ / Dip “≥2+” | <10 / Dip “-” | 10-29 / Dip “±” | 30-299 / Dip “1+” | 300+ / Dip “≥2+” | |||

| All-cause mortality | ||||||||||

| >105 |

1.22 (1.12, 1.34) |

1.63 (1.40, 1.91) |

2.94 (1.98, 4.36) |

8.00 (4.36, 14.7) |

1.18 (1.09, 1.29) |

1.27 (1.15, 1.40) |

1.45 (1.26, 1.69) |

2.40 (1.90, 3.01) |

3.62 (2.42, 5.41) |

1.23 (1.15, 1.31) |

| 90-104 | Reference† |

1.52 (1.30, 1.79) |

1.84 (1.54, 2.20) |

4.41 (2.97, 6.55) |

Reference | Reference† |

1.35 (1.23, 1.48) |

1.73 (1.57, 1.91) |

2.89 (2.13, 3.91) |

Reference |

| 75-89 |

0.93 (0.87, 0.98) |

1.30 (1.11, 1.52) |

1.72 (1.45, 2.04) |

2.61 (1.90, 3.58) |

0.92 (0.87, 0.98) |

0.94 (0.88, 0.99) |

1.27 (1.16, 1.38) |

1.58 (1.4, 1.78) |

2.18 (1.76, 2.71) |

0.95 (0.90, 1.00) |

| 60-74 | 1.02 (0.94, 1.10) |

1.3 (1.07, 1.57) |

1.95 (1.65, 2.30) |

3.84 (2.37, 6.22) |

1.00 (0.93, 1.08) |

0.99 (0.91, 1.06) |

1.31 (1.15, 1.49) |

1.77 (1.57, 2.00) |

2.32 (1.89, 2.85) |

1.01 (0.94, 1.09) |

| 45-59 |

1.35* (1.16, 1.56) |

1.90 (1.49, 2.42) |

2.59* (2.02, 3.33) |

4.12 (2.83, 6.00) |

1.33* (1.19, 1.49) |

1.11* (1.01, 1.22) |

1.62 (1.44, 1.82) |

1.90* (1.59, 2.28) |

2.72 (2.14, 3.45) |

1.15* (1.05, 1.25) |

| 30-44 |

2.29* (1.82, 2.89) |

3.17* (2.62, 3.84) |

3.89* (2.73, 5.53) |

5.15 (2.95, 9.00) |

1.96* (1.65, 2.32) |

1.53* (1.32, 1.77) |

2.34* (2.07, 2.63) |

2.80* (2.25, 3.49) |

4.24 (3.17, 5.68) |

1.60* (1.44, 1.79) |

| 15-29 |

3.55* (2.16, 5.83) |

4.86 (2.06, 11.5) |

6.52 (3.86, 11.0) |

14.8* (7.07, 30.8) |

3.85* (2.68, 5.54) |

2.18* (1.56, 3.06) |

3.94 (3.15, 4.91) |

3.7 (2.46, 5.56) |

5.26* (4.02, 6.90) |

2.18* (1.87, 2.54) |

| <15 |

5.14 (1.83, 14.4) |

12.8* (7.28, 22.7) |

21.19 (6.12, 73.4) |

25.7 (9.16, 72.2) |

6.06 (3.51, 10.5) |

8.42 (2.94, 24.2) |

5.98* (3.64, 9.81) |

7.89 (5.94, 10.5) |

9.74 (7.24, 13.1) |

3.62 (3.19, 4.11) |

| Overall | Reference |

1.31 (1.19, 1.45) |

1.73 (1.54, 1.93) |

2.80* (2.31, 3.39) |

Reference |

1.31 (1.25, 1.38) |

1.65 (1.54, 1.77) |

2.33* (2.07, 2.63) |

||

| Cardiovascular mortality | ||||||||||

| >105 | 1.16 (0.90, 1.49) |

1.99 (1.28, 3.09) |

5.47 (3.18, 9.43) |

13.41* (7.05, 25.5) |

1.19 (0.93, 1.54) |

1.32 (1.00, 1.75) |

1.28 (0.94, 1.76) |

2.56 (1.82, 3.62) |

2.34* (1.25, 4.40) |

1.17 (0.93, 1.48) |

| 90-104 | Reference† |

1.54 (1.26, 1.89) |

1.80 (1.23, 2.62) |

7.70* (3.17, 18.7) |

Reference | Reference† |

1.48 (1.17, 1.86) |

1.67 (1.38, 2.03) |

2.68* (2.00, 3.61) |

Reference |

| 75-89 | 1.04 (0.92, 1.18) |

1.64 (1.20, 2.25) |

2.25 (1.72, 2.95) |

6.17* (3.68, 10.4) |

1.05 (0.97, 1.14) |

0.98 (0.92, 1.04) |

1.29 (1.14, 1.45) |

1.83 (1.50, 2.25) |

2.54* (1.98, 3.26) |

0.99 (0.94, 1.05) |

| 60-74 |

1.23* (1.02, 1.49) |

1.34 (0.92, 1.97) |

3.47* (2.67, 4.50) |

4.47 (2.33, 8.58) |

1.23* (1.05, 1.45) |

1.03* (0.96, 1.10) |

1.37 (1.20, 1.57) |

2.10* (1.83, 2.41) |

2.83 (2.10, 3.81) |

1.06* (0.99, 1.14) |

| 45-59 |

1.72* (1.32, 2.24) |

2.65* (1.75, 4.02) |

4.57* (3.30, 6.33) |

8.75* (5.79, 13.2) |

1.77* (1.44, 2.17) |

1.35* (1.22, 1.48) |

1.81* (1.54, 2.13) |

2.23* (1.89, 2.65) |

3.50* (2.42, 5.06) |

1.35* (1.22, 1.50) |

| 30-44 |

4.29* (3.39, 5.43) |

5.31* (3.28, 8.58) |

5.26 (2.77, 10.0) |

9.74 (3.74, 25.4) |

3.36* (2.55, 4.43) |

1.93* (1.66, 2.25) |

2.85* (2.10, 3.86) |

3.7 (2.92, 4.69) |

5.36 (4.21, 6.83) |

1.92* (1.68, 2.19) |

| 15-29 |

6.94* (4.12, 11.7) |

11.9 (2.63, 53.5) |

18.7 (5.33, 65.32) |

73.6* (15.2, 357) |

6.21* (3.65, 10.6) |

2.96* (1.98, 4.43) |

2.98 (1.52, 5.83) |

2.35 (1.35, 4.09) |

6.38* (4.73, 8.60) |

2.12* (1.77, 2.53) |

| <15 | 2.60 (0.33, 20.4) |

33.0 (10.5, 103) |

8.59 (2.57, 28.7) |

14.1 (5.20, 38.0) |

5.69 (3.07, 10.6) |

7.40 (2.74, 20.0) |

8.57 (4.20, 17.5) |

7.75 (4.63, 13.0) |

3.56 (2.48, 5.09) |

|

| Overall | Reference |

1.50 (1.29, 1.74) |

2.04 (1.74, 2.39) |

3.26* (2.32, 4.57) |

Reference |

1.38 (1.26, 1.51) |

1.79 (1.58, 2.03) |

2.33* (1.99, 2.74) |

||

Values are hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs fro all-cause mortality (top) and cardiovascular mortality (bottom). Colors indicate increase in HRs from low (green) to high (red); bold values shows statistical significance (P<0.05) relative to the reference category, and stars denotes significant interaction with hypertensive status (P<0.05) for the corresponding category.

The pooled crude incidence rate (per 1000 person-years) in the reference category of non-hypertensives versus hypertensives was 2.9 versus 8.8 for all-cause and 0.5 versus 3.0 for cardiovascular mortality, respectively.

Largely similar results were observed when the general population with ACR and dipstick and high-risk cohorts were analyzed separately (Supplemental Figures 7 and 8). In analyses categorizing individuals as normotensives (systolic/diastolic blood pressure <120/80 mmHg), pre-hypertensives (systolic/diastolic blood pressure 120-139/80-89 mmHg), controlled (systolic/diastolic blood pressure <140/90 mmHg under antihypertensive drugs use) and uncontrolled hypertensives (systolic/diastolic blood pressure ≥140/90, we observed the strongest risk associations in normotensives and the weakest risk association in uncontrolled hypertensives (supplemental Figure 9). Subdivision of the hypertensive group into treated versus untreated hypertensives resulted in similar risk associations in each hypertension category (supplemental Figure 10). When hypertensive status was defined by only blood pressure values (systolic/diastolic blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg, supplemental Figure 11), or systolic and diastolic blood pressures were modeled as continuous variables, consistently stronger CKD-mortality associations were observed at lower blood pressure (supplemental Figures 12-15).

Finally, in CKD cohorts the associations of eGFR and albuminuria with mortality outcomes were largely comparable to the results of the combined general population and high-risk cohorts (supplemental Figure 16). Association of ACR with mortality was less steep in both non-hypertensive and hypertensive groups in the CKD cohorts than in the respective combined general population and high-risk cohorts.

End-stage renal disease

In the 5 general population and high-risk cohorts with information on antihypertensive drugs, blood pressure, and incident ESRD (282 ESRD events [cumulative incidence, 1.0%] in non-hypertensives vs. 807 events [2.1%] in hypertensives), low eGFR and high ACR were associated with higher risk of ESRD in both non-hypertensives and hypertensives (supplemental Figure 17). Although significant interaction was observed in the range of eGFR 55 to 72 ml/min/1.73m2 (higher HR for eGFR in hypertensives than in non-hypertensives), the test for overall interaction did not reach significance (P=0.07). Moreover, the eGFR-ESRD relationship also was comparable in analyses categorizing hypertension status based only on blood pressure, without taking antihypertensive treatment into account (supplemental Figure 18, P for overall interaction=0.20). Neither point-wise nor overall interaction of ACR with hypertensive status on ESRD was significant (P for overall interaction=0.92, supplemental Figure 17).

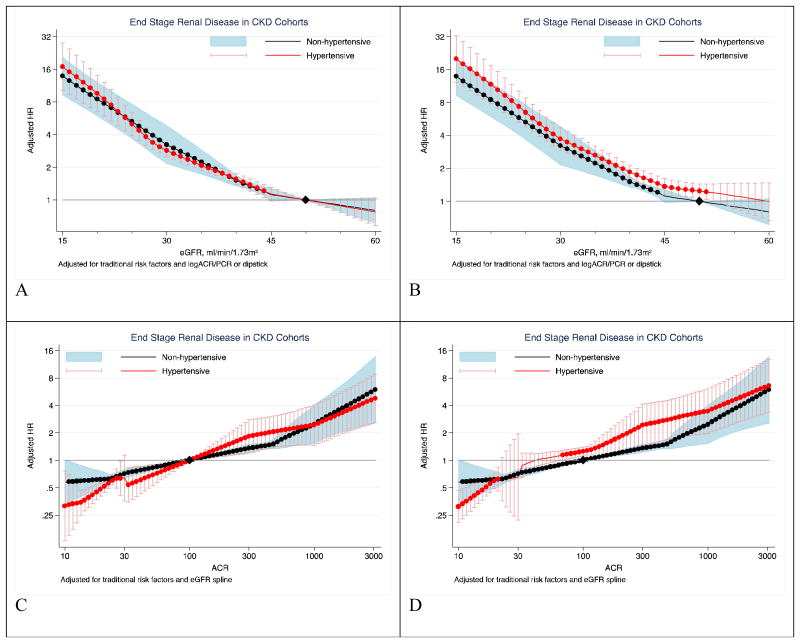

In the 13 CKD cohorts with a total of 5,924 ESRD events (2,597 events [cumulative incidence, 13.9%] in non-hypertensives; 3,327 events [9.7%] in hypertensives), a clear dose-response association of low eGFR and high ACR with ESRD was observed in both the non-hypertensive and hypertensive groups (Figure 3). These associations did not differ by hypertensive status (P for overall interaction=0.42 for eGFR and 0.64 for ACR). Similarly, categorical analyses of eGFR and albuminuria did not demonstrate interaction of hypertensive status with either eGFR or albuminuria (Table 3). Likewise, no significant interaction was observed in analyses incorporating antihypertensive medication use in the definition of hypertension (supplemental Figure 19).

Figure 3. Hazard ratios of ESRD according to eGFR and ACR in non-hypertensives (black-line) versus hypertensives (red-line).

Panels A and B shows eGFR association with ESRD and panels C and D shows ACR association with ESRD in CKD cohorts. Left panels use eGFR of 50 mL/min/1.73m2 (B) and ACR of 5 mg/g (C) among non-hypertensive as a single reference point (diamond) for both hypertensive and non-hypertensive individuals. Right panels use eGFR of 50 mL/min/1.73m2 (A) and ACR of 100 mg/g (C) as the reference points (diamond) in each hypertensive and non-hypertensive groups, respectively. Because there were few participants with eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73m2 in the CKD cohorts by definition, the associations were only shown below 60. Hazard ratios were adjusted for age, sex, race, smoking, history of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, serum total cholesterol concentration, body mass index, and albuminuria (log-ACR, log-PCR or categorical dipstick proteinuria [negative, trace, 1+, ≥2+]) or eGFR splines, as appropriate.

Table 3. Cross-tabulation of hazard ratios for ESRD according to eGFR and albuminuria clinical categories by hypertension status in the CKD cohorts.

| eGFR | Non-hypertensives | Hypertensives | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACR/Dipstick | ACR/Dipstick | |||||||||

| <30 / Dip “-/±” | 30-29 9/ Dip “1+” | 300-999 / Dip “2+” | 1000+ / Dip “≥3+” | <30 / Dip “-/±” | 30-29 9/ Dip “1+” | 300-999 / Dip “2+” | 1000+ / Dip “≥3+” | |||

| ESRD | ||||||||||

| ≥75 | 0.53 (0.03, 9.85) |

0.91 (0.52, 1.62) |

1.62 (0.86, 3.04) |

2.40 (0.36, 15.93) |

0.56 (0.26, 1.22) |

0.79 (0.32, 1.94) |

1.48 (0.81, 2.71) |

1.43 (0.48, 4.26) |

3.61 (1.89, 6.89) |

0.69 (0.30, 1.56) |

| 45-74 | Reference† |

1.81 (1.31, 2.50) |

1.99 (1.19, 3.33) |

6.01 (3.78, 9.57) |

Reference | Reference† |

2.61 (1.17, 5.81) |

4.90 (1.80, 13.3) |

6.12 (3.35, 11.2) |

Reference |

| 30-44 |

1.96 (1.33, 2.88) |

3.43 (2.11, 5.58) |

5.08 (3.62, 7.12) |

15.6 (6.62, 36.9) |

2.02 (1.70, 2.39) |

1.88 (0.67, 5.28) |

5.65 (2.11, 15.1) |

8.57 (3.24, 22.7) |

17.1 (6.52, 44.8) |

2.26 (1.80, 2.85) |

| 15-29 |

5.45 (2.97, 10.00) |

9.41 (6.33, 14.0) |

21.4 (10.4, 44.3) |

44.1 (15.9, 122) |

7.90 (5.47, 11.4) |

5.45 (2.81, 10.6) |

12.5 (6.41, 24.5) |

27.0 (8.66, 84.2) |

50.6 (15.1, 170) |

7.73 (5.60, 10.7) |

| 0-14 |

6.26 (2.61, 15.0) |

17.5 (12.2, 25.2) |

30.3 (20.6, 44.4) |

28.7 (17.4, 47.4) |

28.0 (13.9, 56.6) |

- |

14.4 (9.24, 22.5) |

23.9 (15.5, 37.0) |

34.1 (22.3, 52.0) |

25.9 (12.9, 52.0) |

| Reference |

1.86 (1.52, 2.28) |

2.94 (2.35, 3.69) |

5.80 (3.86, 8.70) |

Reference |

2.27 (1.58, 3.24) |

3.88 (2.17, 6.95) |

7.08 (4.02, 12.5) |

|||

Values are hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs for end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Colors indicate increase in HRs from low (green) to high (red); bold values shows statistical significance (P<0.05) relative to the reference category, and stars denotes significant interaction with hypertensive status (P<0.05) for the corresponding category.

The pooled crude incidence rate (per 1000 person-years) ESRD in the reference category of non-hypertensives versus hypertensives was 4.14 versus 6.37.

Stratified analyses

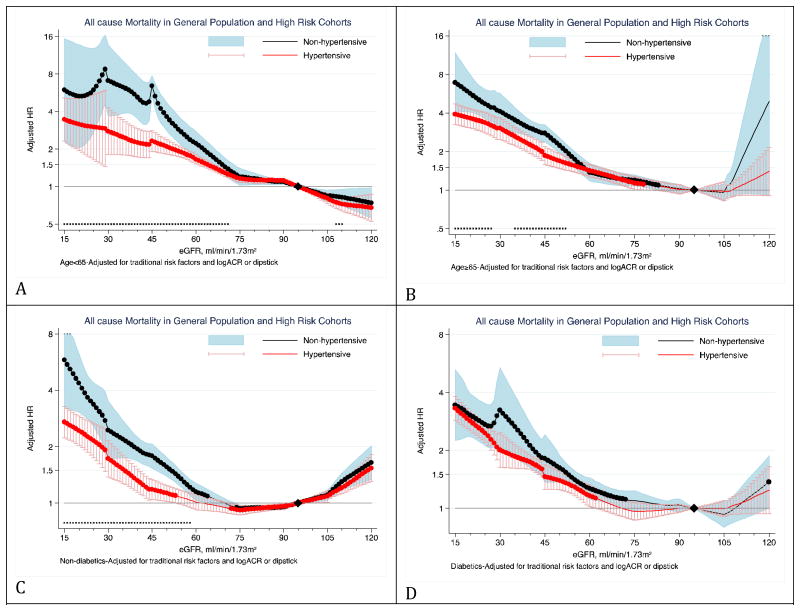

The stronger eGFR-mortality association in non-hypertensives as compared to hypertensives was more evident in the absence of diabetes (Figure 4 and supplemental Figure 20). Similar attenuation in diabetics was not observed for the ACR association with mortality outcomes (supplemental Figures 21 and 22). There was no significant interaction of hypertensive status with either eGFR or ACR for the associations with ESRD among individuals with or without diabetes in the CKD cohorts (supplemental Figures 23 and 24).

Figure 4. Hazard ratios of all-cause mortality for eGFR in non-hypertensives (black-line) versus hypertensives (red-line) according to diabetes status.

Panels A through D show eGFR association with all-cause mortality in non-diabetics (panel A and B) versus diabetics (panel C and D) in the combined general and high-risk populations. Significant interaction between hypertension and eGFR is represented by “x” signs. Hazard ratios were adjusted for age, sex, race, smoking, history of cardiovascular disease, serum total cholesterol concentration, body mass index, and albuminuria (log-ACR, log-PCR or categorical dipstick proteinuria [negative, trace, 1+, ≥2+]).

Finally, stratified analyses according to gender, age (< vs. ≥65 years), and history of cardiovascular disease for all-cause mortality demonstrated that there was a more pronounced multiplicative interaction of eGFR and ACR with hypertensive status in the lower risk strata (i.e., age <65 years, no history of cardiovascular disease) (supplemental Figures 25 and 28). One exception was gender where higher risk in non-hypertensives was more evident in males compared to females (supplemental Figures 29 and 30). This was particularly the case for ACR, as the higher risk of all-cause mortality in non-hypertensives versus hypertensives was only observed in males.

Discussion

In this meta-analysis of 1,089,496 participants from 32 general and high-risk populations, low eGFR and high ACR showed dose-dependent associations with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality and ESRD in both non-hypertensive and hypertensive individuals. The associations of eGFR and ACR with mortality outcomes were stronger in non-hypertensives as compared to hypertensive individuals, whereas the eGFR and ACR associations with ESRD did not differ by hypertensive status. Dose-dependent associations of low eGFR and high ACR also were observed in the 13 CKD cohorts with 38,160 participants. In these cohorts, however, neither the associations with mortality nor with ESRD differed by hypertensive status. The observed interaction of eGFR and ACR with mortality outcomes in the general and high-risk population cohorts was not due to presence of diabetes. Interaction of the kidney measures with diabetes is explicitly assessed in the accompanying paper.22

A few studies have reported a stronger association of eGFR with mortality in non-hypertensive individuals as compared to hypertensive individuals.23-26 Although in our analysis individual studies were frequently underpowered to detect statistically significant interaction between hypertension and eGFR, the direction of the effect modification were largely consistent across cohorts. The interaction of low eGFR with hypertension on mortality outcomes was mainly driven by a steeper association of eGFR with mortality outcomes in non-hypertensives in the preserved eGFR range down to eGFR of approximately 45 mL/min/1.73m2. In the eGFR range below 45 ml/min/1.73m2, low eGFR showed similar relative risk gradient for mortality outcomes in both non-hypertensive and hypertensives. This finding was consistent in the three types of cohorts (general population, high-risk, and CKD cohorts). A previously reported J-shaped association between eGFR and mortality (i.e., paradoxically increased risk at higher eGFR)19 was observed in both non-hypertensives and hypertensives, particularly in older individuals, probably inherent to creatinine-based eGFR equations reflecting muscle-wasting in some individuals.

We also observed stronger association of albuminuria with mortality outcomes among non-hypertensives compared to hypertensives. Unlike eGFR, the association between ACR and mortality outcomes and ESRD was monotonic without J-shape in both hypertension and non-hypertension groups. This would be a nice property for ACR in terms of risk prediction, although further studies are required to assess its usefulness for improvement in risk prediction.27 Although, ACR is considered a more sensitive and thus preferable method in clinical and laboratory guidelines.1, 28 we observed similar interaction of hypertension on mortality when we combined ACR and dipstick proteinuria categories (Table 2).

The association of eGFR and ACR with ESRD was similar in hypertensive versus non-hypertensive individuals in all three types of cohorts. The increased risk of ESRD conferred by CKD in hypertensives might be attenuated by antihypertensive treatment.29 In the CKD cohorts, the majority of participants were on antihypertensive treatment which led us to classify study-participants as hypertensive based on blood pressure values only. Nevertheless, in sensitivity analysis of a subset of CKD cohorts with sufficient number of participants with normal blood pressure not using antihypertensive drugs, incorporation of antihypertensive medication use in the definition of hypertension showed similar results.

Possible explanations for the relatively stronger association of low eGFR and high ACR with mortality in non-hypertensive as compared to hypertensive individuals include comorbid conditions such as changes in cardiac structure or function (e.g., heart failure)30, 31 and autonomic dysregulations,32 that predispose for mortality and can limit blood pressure increase. However, sensitivity analysis stratified by history of cardiovascular disease, that also incorporated heart failure, did not demonstrate any evidence for an influence of prior cardiovascular disease on the observed interaction. Nevertheless, we cannot deny the involvement of undiagnosed heart failure. It is also possible that low eGFR and high ACR in non-hypertensives are due to etiologies with a worse prognosis (e.g., glomerulonephritis). Moreover, antihypertensive treatment may affect levels of serum creatinine and albuminuria and reduce the risk of mortality,33, 34 to some extent independent of blood pressure lowering,34 and may contribute to this interaction. However, largely similar associations of eGFR and ACR with mortality outcomes by hypertensive status were observed when we compared treated versus untreated hypertension. Nevertheless, we should not interpret that antihypertensive treatment has no effect on the risk reduction, since there is possibility of bias by treatment indication in observational studies (e.g., high-risk individuals with long-term hypertension are likely to be treated).

These results provide evidence that the association of low eGFR and high albuminuria with mortality and ESRD in non-hypertensive individuals is stronger or equal to the associations in hypertensive individuals. This was consistently demonstrated when we treated the key exposures (eGFR and ACR) and the effect modifier (blood pressure) as continuous and categorical variables. Our findings suggest that CKD warrants attention and management irrespective hypertension status. Nevertheless, we caution against over-interpretation of these results, which are based on observational studies.

This study has several limitations. Measurements of creatinine, albuminuria and blood pressure were not standardized across all studies. Some studies measured creatinine and albuminuria in fresh samples, whereas other studies used frozen samples. Majority of studies with dipstick albuminuria measurements were from Asia, and general population-based studies with ACR mainly consists of whites. Nevertheless, analyses by cohort type showed comparable results. Also, our consortium relatively underrepresents blacks, particularly from Africa, and most of them were from cohorts in the US. Information on the number of antihypertensive drugs, duration of antihypertensive treatment, diet and exercise were not included. Finally, given that our results were primarily based on observational cohorts, there is a possibility of residual confounding. Finally, future studies are needed to assess whether any cause-specific mortality is driving the all-cause mortality interaction.

In conclusion, in this large-size pooled analysis, the eGFR and ACR associations with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality were similar or even stronger in non-hypertensive individuals as compared to hypertensive individuals. The presence of CKD in non-hypertensive individuals should be considered at least an equally relevant risk factor for mortality and ESRD as it is in hypertensive individuals.

Panel: Research in context

Systematic review

Given the high prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in hypertensive individuals, clinical guidelines recommend screening for CKD in hypertensive individuals.13-15 However, whether the association of CKD with cardiovascular disease or mortality in hypertensive versus non-hypertensives is similar or not is unknown. Electronic searches (e.g., PubMed) revealed only a few studies that focused on the association of blood pressure values with mortality outcomes in subjects with CKD.23-26

We meta-analyzed individual-level data from 45 cohorts with over 1 million participants to compare mortality and end-stage renal disease risk in hypertensive versus non-hypertensive individuals. The participating cohorts were categorized as general population, high-risk population and CKD population. Although details on the emergence of the CKD Prognosis Consortium are published elsewhere,6-10 briefly, these studies were identified by electrical searches, discussion between investigators, and a call for participation through a published position statement of KDOQI and KDIGO and the KDIGO website (www.kdigo.org).6

Interpretation

CKD association was stronger with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among individuals without hypertension than in those with hypertension, but the associations with ESRD were similar.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The CKD-PC Data Coordinating Center is underpinned by a program grant from the US National Kidney Foundation (NKF funding sources include Abbott and Amgen). A variety of sources have supported enrollment and data collection including laboratory measurements, and follow-up in the collaborating cohorts of the CKD-PC. These funding sources of the collaborating cohorts are listed in web appendix page 33-35. Mahmoodi's fellowship at Johns Hopkins School of Public Health is supported by grants of Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research and the Dutch Kidney Foundation.

Role of the Funding Source: The sponsors had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, and data interpretation or writing of the manuscript. BKM, KM, and JC had full access to all analyses and all authors had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publications informed by discussions with the collaborators.

Footnotes

Contributors: KM, MW, JC, PEdJ, and BCA conceived the study concept and design. KM and JC with the Data Coordinating Center members listed below collected data from collaborating cohorts, and the CKD-PC investigators/collaborators listed below acquired their cohort data. BKM, KM, MW, JC, and the Data Coordinating Center members analyzed the data. All authors took part in the interpretation of the data. BKM, KM, JC and BCA, drafted the manuscript, and all authors provided critical revisions of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All collaborators shared data and were given the opportunity to comment on the manuscript. KM and JC obtained funding for CKD-PC and individual cohort and collaborator support is listed in web appendix p 46-48.

CKD-PC investigators/collaborators (The study acronyms/abbreviations are listed in Web Appendix page 37): AASK: Jackson Wright, Lawrence Appel, Tom Greene, Brad C Astor; ADVANCE: John Chalmers, Stephen MacMahon, Mark Woodward, Hisatomi Arima; Aichi: Hiroshi Yatsuya, Kentaro Yamashita, Hideaki Toyoshima, Koji Tamakoshi; AKDN: Marcello Tonelli, Brenda Hemmelgarn, Aminu Bello, Matt James; ARIC: Josef Coresh, Brad C Astor, Kunihiro Matsushita, Yingying Sang; AusDiab: Robert C Atkins, Kevan R Polkinghorne, Steven Chadban; Beaver Dam CKD: Anoop Shankar, Ronald Klein, Barbara EK Klein, Kristine E Lee; Beijing Cohort: Haiyan Wang, Fang Wang, Luxia Zhang, Li Zuo,; British Columbia CKD: Adeera Levin, Ognjenka Djurdjev ; CARE: Marcello Tonelli, Frank M Sacks, Gary C Curhan; CHS: Michael Shlipak, Carmen Peralta, Ronit Katz, Linda Fried; CIRCS: Hiroyasu Iso, Akihiko Kitamura, Tetsuya Ohira, Kazumasa Yamagishi; COBRA: Tazeen H Jafar, Muhammad Islam, Juanita Hatcher, Neil Poulter, Nish Chaturvedi; CRIB: Martin J Landray, Jonathan R Emberson, John N Townend, David C Wheeler; ESTHER: Dietrich Rothenbacher, Hermann Brenner, Heiko Müller, Ben Schöttker; Framingham: Caroline S Fox; Shih-Jen Hwang, James B Meigs; Geisinger: Robert M Perkins; GLOMMS-1 Study: Nick Fluck, Laura E Clark, Gordon J Prescott, Angharad Marks, Corri Black; Gubbio: Massimo Cirillo; HUNT: Stein Hallan, Knut Aasarød, Cecilia M Øien, Marie Radtke; IPHS: Fujiko Irie, Hiroyasu Iso, Toshimi Sairenchi, Kazumasa Yamagishi; Kaiser Permanente NW: David H Smith, Jessica W Weiss, Eric S Johnson, Micah L Thorp; KEEP: Allan J Collins, Joseph A Vassalotti, Suying Li, Shu-Cheng Chen; KP Hawaii: Brian J Lee; MASTERPLAN: Jack F Wetzels, Peter J Blankestijn, Arjan D van Zuilen; MDRD: Mark Sarnak, Andrew S Levey, Vandana Menon; MESA: Michael Shlipak, Mark Sarnak, Carmen Peralta, Ronit Katz, Holly J Kramer, Ian H de Boer; MMKD: Florian Kronenberg, Barbara Kollerits, Eberhard Ritz; MRC Older People: Paul Roderick, Dorothea Nitsch, Astrid Fletcher, Christopher Bulpitt; MRFIT: Areef Ishani, James D Neaton; NephroTest: Marc Froissart, Benedicte Stengel, Marie Metzger, Jean-Philippe Haymann, Pascal Houillier, Martin Flamant; NHANES III: Brad C Astor, Josef Coresh, Kunihiro Matsushita; Ohasama: Takayoshi Ohkubo, Hirohito Metoki, Masaaki Nakayama, Masahiro Kikuya, Yutaka Imai; Okinawa 83/93: Kunitoshi Iseki; Pima Indian: Robert G Nelson, William C Knowler; PREVEND: Ron T Gansevoort, Paul E de Jong, Bakhtawar K Mahmoodi, Hans Hillege; Rancho Bernardo: Simerjot Kaur Jassal, Elizabeth Barrett-Connor, Jaclyn Bergstrom; RENAAL: Hiddo J Lambers Heerspink, Barry E Brenner, Dick de Zeeuw; Renal REGARDS: David G Warnock, Paul Muntner, Suzanne Judd, William McClellan; Severance: Sun Ha Jee, Heejin Kimm, Jaeseong Jo, Yejin Mok; STENO: Peter Rossing, Hans-Henrik Parving; Sunnybrook: Navdeep Tangri, David Naimark; Taiwan GP: Chi-Pang Wen, Sung-Feng Wen, Chwen-Keng Tsao, Min-Kuang Tsai; ULSAM: Johan Ärnlöv, Lars Lannfelt, Anders Larsson; ZODIAC: Henk J Bilo, Hanneke Joosten, Nanno Kleefstra, Klaas H Groenier, Iefke Drion

CKD-PC Steering Committee: Brad C. Astor, Josef Coresh (Chair), Ron T. Gansevoort, Brenda R Hemmelgarn, Paul E. de Jong, Andrew S. Levey, Adeera Levin, Kunihiro Matsushita, Chi-Pang Wen, and Mark Woodward

CKD-PC Data Coordinating Center: Shoshana H Ballew (Coordinator), Josef Coresh (Principal investigator), Morgan Grams, Bakhtawar K Mahmoodi, Kunihiro Matsushita (Director), Yingying Sang (Lead programmer), Mark Woodward (Senior statistician); administrative support: Laura Camarata, Xuan Hui, Jennifer Seltzer, Heather Winegrad

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

References

- 1.K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:S1–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chadban SJ, Briganti EM, Kerr PG, et al. Prevalence of kidney damage in Australian adults: The AusDiab kidney study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:S131–8. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000070152.11927.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298:2038–47. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.17.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hallan SI, Coresh J, Astor BC, et al. International comparison of the relationship of chronic kidney disease prevalence and ESRD risk. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2275–84. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005121273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wen CP, Cheng TYD, Tsai MK, et al. All-cause mortality attributable to chronic kidney disease: a prospective cohort study based on 462 293 adults in Taiwan. Lancet. 2008;371:2173–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60952-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levey AS, de Jong PE, Coresh J, et al. The definition, classification, and prognosis of chronic kidney disease: a KDIGO Controversies Conference report. Kidney Int. 2011;80:17–28. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsushita K, van der Velde M, Astor BC, et al. Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: a collaborative meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:2073–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60674-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Velde M, Matsushita K, Coresh J, et al. Lower estimated glomerular filtration rate and higher albuminuria are associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. A collaborative meta-analysis of high-risk population cohorts. Kidney Int. 2011;79:1341–52. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gansevoort RT, Matsushita K, van der Velde M, et al. Lower estimated GFR and higher albuminuria are associated with adverse kidney outcomes. A collaborative meta-analysis of general and high-risk population cohorts. Kidney Int. 2011;80:93–104. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Astor BC, Matsushita K, Gansevoort RT, et al. Lower estimated glomerular filtration rate and higher albuminuria are associated with mortality and end-stage renal disease. A collaborative meta-analysis of kidney disease population cohorts. Kidney Int. 2011;79:1331–40. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Renal Data System, USRDS 2011 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Bethesda, MD: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hallan SI, Stevens P. Screening for chronic kidney disease: which strategy? J Nephrol. 2010;23:147–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crowe E, Halpin D, Stevens P. Early identification and management of chronic kidney disease: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1530. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, et al. 2007 ESH-ESC Practice Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension: ESH-ESC Task Force on the Management of Arterial Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2007;25:1751–62. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282f0580f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ritz E. Hypertension and kidney disease. Clin Nephrol. 2010;74(Suppl 1):S39–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Couser WG. Chronic kidney disease the promise and the perils. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:2803–5. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007080964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El Nahas M. Cardio-Kidney-Damage: a unifying concept. Kidney Int. 2010;78:14–8. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsushita K, Mahmoodi BK, Woodward M, et al. Comparison of risk prediction using the CKD-EPI equation and the MDRD study equation for estimated glomerular filtration rate. JAMA. 2012;307:1941–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.3954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–12. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. Expressing the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate with standardized serum creatinine values. Clin Chem. 2007;53:766–72. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.077180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fox CS, Matsushita K, Woodward M, et al. Associations of Kidney Disease Measures with Mortality and End-Stage Renal Disease in Individuals With and Without Diabetes: A Meta-analysis of 1,024,977 Individuals. Lancet. 2012 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61350-6. submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kovesdy CP, Anderson JE. Reverse epidemiology in patients with chronic kidney disease who are not yet on dialysis. Semin Dial. 2007;20:566–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2007.00335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berl T, Hunsicker LG, Lewis JB, et al. Impact of achieved blood pressure on cardiovascular outcomes in the Irbesartan Diabetic Nephropathy Trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2170–9. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004090763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kovesdy CP, Trivedi BK, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Anderson JE. Association of low blood pressure with increased mortality in patients with moderate to severe chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:1257–62. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfk057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weiss JW, Johnson ES, Petrik A, Smith DH, Yang X, Thorp ML. Systolic blood pressure and mortality among older community-dwelling adults with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56:1062–71. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clase CM, Gao P, Tobe SW, et al. Estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria as predictors of outcomes in patients with high cardiovascular risk: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:310–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-5-201103010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller WG, Bruns DE, Hortin GL, et al. Current issues in measurement and reporting of urinary albumin excretion. Clin Chem. 2009;55:24–38. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.106567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sarafidis PA, Stafylas PC, Kanaki AI, Lasaridis AN. Effects of renin-angiotensin system blockers on renal outcomes and all-cause mortality in patients with diabetic nephropathy: an updated meta-analysis. Am J Hypertens. 2008;21:922–9. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2008.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borsboom H, Smans L, Cramer MJ, et al. Long-term blood pressure monitoring and echocardiographic findings in patients with end-stage renal disease: reverse epidemiology explained? Neth J Med. 2005;63:399–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guder G, Frantz S, Bauersachs J, et al. Reverse epidemiology in systolic and nonsystolic heart failure: cumulative prognostic benefit of classical cardiovascular risk factors. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2:563–71. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.825059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brotman DJ, Bash LD, Qayyum R, et al. Heart rate variability predicts ESRD and CKD-related hospitalization. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1560–70. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009111112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tocci G, Paneni F, Palano F, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers and diabetes: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled clinical trials. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24:582–90. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2011.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turnbull F. Effects of different blood-pressure-lowering regimens on major cardiovascular events: results of prospectively-designed overviews of randomised trials. Lancet. 2003;362:1527–35. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14739-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.