Abstract

Variability in neonatal vancomycin pharmacokinetics and the lack of consensus for optimal trough concentrations in neonatal intensive care units pose challenges to dosing vancomycin in neonates. Our objective was to determine vancomycin pharmacokinetics in neonates and evaluate dosing regimens to identify whether practical initial recommendations that targeted trough concentrations most commonly used in neonatal intensive care units could be determined. Fifty neonates who received vancomycin with at least one set of steady-state levels were evaluated retrospectively. Mean pharmacokinetic values were determined using first-order pharmacokinetic equations, and Monte Carlo simulation was used to evaluate initial dosing recommendations for target trough concentrations of 15 to 20 mg/liter, 5 to 20 mg/liter, and ≤20 mg/liter. Monte Carlo simulation revealed that dosing by mg/kg of body weight was optimal where intermittent dosing of 9 to 12 mg/kg intravenously (i.v.) every 8 h (q8h) had the highest probability of attaining a target trough concentration of 15 to 20 mg/liter. However, continuous infusion with a loading dose of 10 mg/kg followed by 25 to 30 mg/kg per day infused over 24 h had the best overall probability of target attainment. Initial intermittent dosing of 9 to 15 mg/kg i.v. q12h was optimal for target trough concentrations of 5 to 20 mg/liter and ≤20 mg/liter. In conclusion, we determined that the practical initial vancomycin dose of 10 mg/kg vancomycin i.v. q12h was optimal for vancomycin trough concentrations of either 5 to 20 mg/liter or ≤20 mg/liter and that the same initial dose q8h was optimal for target trough concentrations of 15 to 20 mg/liter. However, due to large interpatient vancomycin pharmacokinetic variability in neonates, monitoring of serum concentrations is recommended when trough concentrations between 15 and 20 mg/liter or 5 and 20 mg/liter are desired.

INTRODUCTION

Premature and very low birth weight (VLBW) infants (≤1,500 g) admitted to neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) are susceptible to Gram-positive infections due to their immunocompromised state and exposure to procedures such as central venous line insertions. Late-onset sepsis (occurring after 3 days of age) can occur in as many as 21% of VLBW infants (1) and is associated with neonatal complications, prolonged hospital stay, mortality, and morbidity (1, 2). More than 50% of systemic infections in neonates are caused by coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS), and the majority of these are methicillin resistant (1, 2). Therefore, neonates with suspected late-onset sepsis typically receive vancomycin (1, 3).

The pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) parameter that is most widely accepted as the best predictor of outcome (clinical and microbiological) with vancomycin is the ratio of the area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) to the MIC, and recent guidelines have recommended an AUC/MIC ratio of ≥400 as the PK/PD target for clinical efficacy in the treatment of serious methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections (4, 5). Unfortunately, determination of the AUC for vancomycin in clinical settings is not feasible, and thus, vancomycin trough concentrations have been adopted as a surrogate marker for determining the likelihood of AUC target attainment where vancomycin trough concentrations of 15 to 20 mg/liter have been recommended for complicated infections in adults (4, 5). Despite the widespread use of vancomycin in neonates, there is a lack of consensus for optimal dosing in this patient population. There is no evidence of correlation between serum vancomycin concentrations and clinical cure, microbiological cure, or nephrotoxicity in neonates (6–8). However, vancomycin trough concentrations are routinely monitored in neonates, and controversy exists with regard to the optimal target vancomycin trough levels, resulting in numerous different target trough concentration ranges being recommended in the literature for these patients (e.g., 5 to 10 mg/liter, 5 to 12 mg/liter, 5 to 15 mg/liter, 5 to 20 mg/liter, or 12 to 15 mg/liter) (9–19). In addition, the majority of the previous studies describing vancomycin pharmacokinetics in neonates have included small, heterogeneous groups with differing demographics, clinical conditions, lengths of infusion period, serum sampling times, and pharmacokinetic models (1-compartment versus 2-compartment models) (8–17). As a result, the published data (8–17) provide conflicting reports of significant covariates of clearance (CL) and do not provide practical dosing recommendations for the target trough concentrations used in practice today.

Recent guidelines (4, 20) for the treatment of MRSA infections in adults and children recommend higher trough concentration targets of 15 to 20 mg/liter to treat complicated infections, such as health care-associated pneumonia, meningitis, endocarditis, and osteomyelitis. These guidelines acknowledge that data in children were limited. Two recent neonatal studies (15, 18) assessed higher vancomycin target trough concentrations; however, the results from these studies highlight the continued question regarding appropriate vancomycin dosing in neonates and the lack of data to support practical initial dosing for vancomycin in neonates.

Although continuous infusion of vancomycin has been described for the neonatal population (19, 21, 22, 23) and adults (24–30), no practical dosing guidelines for neonates currently exist for the use of continuous infusion. There is no clinical evidence to date to suggest that continuous infusion of vancomycin is more effective than intermittent dosing of vancomycin. However, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis (24) identified that continuous infusion may be less toxic than intermittent dosing in the treatment of staphylococcal bacteremia in adults, likely because it may provide an opportunity to minimize the total daily exposure to vancomycin (30). Further study to develop reasonable dosing guidelines for continuous infusion in neonates that will achieve a steady-state level of 15 to 20 mg/liter and minimize the total daily dose is warranted.

Therefore, the aims of this study were to determine the pharmacokinetics of vancomycin in neonates, identify significant covariates of vancomycin pharmacokinetics in neonates, and develop a practical initial dosing recommendation with the highest probability of attaining levels in plasma most commonly targeted among NICUs (trough concentrations of 15 to 20 mg/liter, 5 to 20 mg/liter, and ≤20 mg/liter with intermittent dosing and a steady-state concentration of 15 to 20 mg/liter with continuous infusion).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Location.

This study was conducted in the level III NICU at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre (SHSC) in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. SHSC is a 1,275-bed tertiary care teaching hospital with 41 NICU beds. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Board (REB) at SHSC on 23 November 2011.

Patient eligibility.

Neonates admitted to the NICU prior to 1 March 2012 who received more than 24 h of vancomycin and had at least one set of steady-state vancomycin levels (peak and trough concentrations or a peak and second postdose random level obtained at the earliest around the third dose) were eligible. Patients were excluded if they were still inpatients at the time of chart review (since REB approval was for a retrospective study), developed acute renal failure (urine output of <1 ml/kg of body weight/h or serum creatinine [sCr] of >100 μmol/liter) before initiation of vancomycin, required renal replacement therapy while receiving vancomycin, or had a calculated vancomycin half-life (t1/2) greater than 4 standard deviations from the mean t1/2 observed in the study population without the availability of another set of levels to confirm the accuracy of this calculated t1/2.

Study design.

A retrospective chart review of 50 patients meeting the established inclusion criteria was conducted. A chronological list of patients admitted to the NICU between 12 September 2010 and 29 February 2012 that had been prescribed vancomycin was generated using the SPIRIT (Stewardship Program Integrating Resource Information Technology) database (31) of the Antimicrobial Stewardship Program at SHSC. Additional patients who received vancomycin prior to 12 September 2010 were identified through review of the vancomycin-monitoring binder utilized by the NICU clinical pharmacists.

Data collection.

All data collected from patient charts, the SPIRIT database, and electronic patient records (EPR) were entered into a Microsoft Excel database. Relevant data collected included the following:

the date of admission to the NICU,

the number of days in the NICU prior to vancomycin therapy,

the number of days from birth to initiation of vancomycin therapy,

gender,

gestational age,

postnatal age (PNA) at the time of vancomycin initiation,

the corrected gestational age (CGA) at the time of vancomycin initiation,

birth weight,

weight at the time closest to the initiation of vancomycin administration,

weight at a time within 24 h of the time that we obtained a set of vancomycin levels,

Apgar scores at 1 and 5 min of age,

indication for vancomycin therapy,

the date vancomycin therapy was initiated,

the date vancomycin therapy was discontinued,

microbiological culture results and sensitivity,

the initial vancomycin dose,

the occurrence of nephrotoxicity (defined as [i] an increase in sCr that was 25% above baseline or [ii] an output in urine of <1 ml/kg/h at the time nearest to vancomycin discontinuation, 2 weeks after vancomycin discontinuation, or at the latest time a value was available),

the baseline serum albumin level (the earliest result available for a patient in the NICU),

the serum albumin level taken at the time nearest to the time that we obtained a set of vancomycin levels,

prior and concomitant use of nephrotoxins (prior use is defined as nephrotoxins prescribed within the 2 weeks prior to vancomycin initiation [nephrotoxins included indomethacin, ibuprofen, furosemide, amphotericin B, gentamicin, tobramycin, and amikacin]),

NICU survival (yes/no), and

a size that is small for the infant's gestational age (SGA) (yes/no) (defined as a birth weight below that of the 10th percentile for a specific gestational age in North American infants).

Finally, the blood urea nitrogen (BUN) level, sCr (Jaffe reaction) level, and urine output over 24 h were obtained at baseline (the earliest results available for a patient in the NICU), at the time nearest to the time that we obtained a set of vancomycin levels, at the time nearest to vancomycin discontinuation, and at the time nearest to 2 weeks after vancomycin discontinuation or the latest time for which a value was available.

Vancomycin pharmacokinetics.

The pharmacokinetic profile of vancomycin in neonates may be characterized using a 1-, 2-, or 3-compartment model. The distribution phase ranges from 0.5 to 1 h in adults (5) and has been reported as 0.05 to 0.49 h in neonates and infants (6, 32). Once vancomycin distribution is complete, it follows first-order elimination. It is at this point that clinically important first-order pharmacokinetic principles can be applied to determine appropriate dosing necessary to attain desired vancomycin trough concentrations as a surrogate marker for AUC/MIC ratio target attainment. When neonates are prescribed vancomycin therapy at SHSC, the initial vancomycin serum concentrations are obtained after the third dose, which assumes that drug concentrations are at steady state. Vancomycin peak concentrations in the NICU at this institution are obtained 1 h following the end of a 1-h infusion, and trough concentrations are obtained just prior to administration of the next dose. It is assumed that the distribution phase of vancomycin is reliably completed by the time a peak serum concentration is drawn and that vancomycin is in the first-order elimination phase (1-compartment model). The peak vancomycin concentration is obtained for no other reason than that two points (the steady-state peak and trough or two postdose concentrations) are required to use first-order pharmacokinetic equations to determine the optimal dose and interval for vancomycin to attain the desired vancomycin steady-state target concentration (trough concentrations of 15 to 20 mg/liter, 5 to 20 mg/liter, and ≤20 mg/liter and the steady-state level with continuous infusion of 15 to 20 mg/liter). Vancomycin concentrations were analyzed using first-order pharmacokinetic principles (33) to calculate extrapolated trough and peak concentrations, the elimination rate constant (kel), the t1/2, the volume of distribution (V), an estimate of total body clearance (CL), the AUC at 24 h (AUC24), a desired dose (in mg and mg/kg/dose, each rounded off to the nearest 1 mg), the dosing interval, and the continuous-infusion loading dose (in mg and mg/kg, each rounded off to the nearest 1 mg). To determine the desired dose and interval for intermittent dosing, a desired peak of 30 mg/liter and desired troughs of 18 mg/liter, 12 mg/liter, and 10 mg/liter were used for steady-state target concentrations of 15 to 20 mg/liter, 5 to 20 mg/liter, and ≤20 mg/liter, respectively. To determine the desired continuous-infusion loading dose and continuous-infusion rate, a desired concentration at the end of a 24-h infusion of 18 mg/liter was utilized for the steady-state target concentration of 15 to 20 mg/liter. The peak of 30 mg/liter was chosen to minimize the fluctuation in levels between peak and trough concentrations, and the trough concentrations of 18 mg/liter, 12 mg/liter, and 10 mg/liter were chosen as midpoints in the desired steady-state target concentrations.

Statistics.

Descriptive statistics were used for patient characteristics and microbiological results (mean, standard deviation, and range). The geometric mean, standard deviation, and range are reported for pharmacokinetics parameters (kel, t1/2, V, CL, AUC24), since these are known to have lognormal distributions.

Univariate linear regression (SPSS 13.01) was used to identify significant covariates (P < 0.2) associated with V (liters) and CL (liters/h) of vancomycin in neonates. Parameters that were included in the univariate regression were parameters that would be known to the clinician prior to the initiation of vancomycin and were not calculated using other parameters put into the regression analysis. Any covariates determined to be significant in univariate analysis (P < 0.2) were then included in multiple linear regression (MLR) analysis (SPSS 13.01) to identify those that remained statistically significant in the best model (lowest P value, with a maximum P of <0.05 considered statistically significant) to predict V (liters) and CL (liters/h). The parameters entered as independent variables included the number of days in the NICU prior to initiation of vancomycin, the number of days from birth to vancomycin initiation, gender, gestational age, PNA at time of vancomycin initiation, CGA at time of vancomycin initiation, birth weight, weight closest to vancomycin initiation, SGA status, Apgar scores at 1 and 5 min of age, BUN level at baseline, sCr level at baseline, sCr level just prior to vancomycin initiation, 24-h urine output (ml/h) at baseline, 24-h urine output (ml/h) at vancomycin initiation, and albumin level at baseline. V and CL calculated from regression equations derived from MLR were then compared to actual patient V and CL values to evaluate the predictive performance of the regression equations. If the predictive performance of the regression equation for either V or CL was poor (R2 ≤ 0.5) and the data plot of predicted V or CL versus actual V or CL, respectively, identified a dichotomous plot, then a Classification and Regression Tree (CART) analysis (CART professional extended edition; Salford Systems) would be completed to identify breakpoints in input parameters of either the V or CL regression equations.

Mean pharmacokinetic data were used to derive initial dosing recommendations, which were then evaluated using Monte Carlo simulation (Oracle Crystal Ball, Fusion edition) (MCS). The means and standard deviations for kel's, V's, and weights of the study patients were input, and 1 million iterations of possible kel, V, and weight values were run to determine the probability of attaining target vancomycin steady-state concentrations of 15 to 20 mg/liter, 5 to 20 mg/liter, and ≤20 mg/liter with any given dosing simulation in neonates. For all simulations involving mg/kg dosing, the weight was assumed to have a normal distribution, the mean and standard deviation for weight from our population pharmacokinetic data were entered into the simulation, and the weight range permitted for random selection in the simulation was 0.4 to 6 kg. The optimal initial dosing regimen was defined as the regimen most likely to attain predetermined criteria that may theoretically correspond to maximal clinical efficacy while minimizing toxicity. For the higher target trough concentrations of 15 to 20 mg/liter, the criteria selected in an attempt to balance efficacy and safety parameters were as follows: (i) a trough concentration of 15 to 20 mg/liter in 70% of patients, (ii) a trough concentration of ≤12 mg/liter in ≤25% of patients, (iii) trough concentrations of ≥25 mg/liter in <10% of patients, (iv) peak concentrations of <40 mg/liter in 70% of patients, (v) peak concentrations of >80 mg/liter in <10% of patients, and (vi) AUC24/MIC ratios of ≥400 in 70% of patients. For the target trough concentrations of 5 to 20 mg/liter and ≤20 mg/liter, criteria were as follows: (i) trough concentrations of 5 to 20 mg/liter in 70% of patients, (ii) trough concentrations of ≤20 mg/liter in 70% of patients, (iii) trough concentrations of ≥25 mg/liter in <10% of patients, (iv) peak concentrations of <40 mg/liter in 70% of patients, and (v) peak concentrations of >80 mg/liter in <10% of patients. As part of each MCS, an assessment of the probability of attaining an AUC24/MIC ratio of ≥400 was completed to assess the likelihood of meeting the optimal PK/PD vancomycin target for serious MRSA infections. In this part of the analysis, MICs were assumed to have a normal distribution (34) truncated at a minimum of 0.5 mg/liter and a maximum of 2 mg/liter, with a mean of 1 mg/liter and a standard deviation of 0.4 mg/liter, resembling the current MIC distribution for MRSA worldwide (35–45). If CART analysis identified breakpoints for vancomycin V and/or CL, then mean pharmacokinetic data and their associated standard deviations for identified subgroups would be analyzed by separate Monte Carlo simulations.

RESULTS

Demographics.

Fifty-eight neonates were screened for inclusion in this retrospective study. Eight neonates were excluded (six had only vancomycin trough concentrations measured, and two were inpatients at the time of chart review). A total of 50 neonates were included in this study, and 58 sets of vancomycin levels were evaluated. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The most common initial vancomycin dosing regimen used in our NICU was 10 mg/kg intravenously (i.v.) every 8 h (q8h), which was independent of gestational age, PNA, and CGA (8). Twenty-nine neonates (58%) had a positive culture, and CoNS were the most commonly identified bacteria (72%) (Table 2). The mean vancomycin pharmacokinetic parameters are detailed in Table 3.

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic of 50 neonatesd | No. (%) | Mean ± SD (range) |

|---|---|---|

| Gestational age (wk) | 27.4 ± 2.5 (23.7–33.7) | |

| Postnatal age (days) | 17.1 ± 12.6 (2–53) | |

| Corrected gestational age (wk) | 29.8 ± 2.5 (24.9–34.4) | |

| Birth wt (kg) | 1.02 ± 0.42 (0.52–2.68) | |

| Small-for-gestational-age status | 3 (6) | |

| Male gender | 31 (62) | |

| NICU survival | 48 (96) | |

| Apgar score at 1 min | 6a (1–9) | |

| Apgar score at 5 min | 8a (2–9) | |

| Indication for vancomycin initiationb | ||

| Sepsis | 31 (58) | |

| NEC | 18 (34) | |

| Sepsis and NEC | 2 (4) | |

| Skin and soft tissue infection | 1 (2) | |

| Peritoneal effusion | 1 (2) | |

| Day of life at initiation of vancomycin | 17.1 ± 12.6 (2–53) | |

| Wt at time of vancomycin initiation | 1.25 ± 0.69 (0.59–4.73) | |

| Vancomycin dose (mg/kg/day) | 37 ± 16 (13–80) | |

| Vancomycin dosing interval (h) | 8a (6–12) | |

| Serum creatinine concn nearest time of vancomycin initiation (μmol/liter) | 56 ± 29 (19–168) | |

| Vancomycin trough concn (mg/liter)c | 58 | 13.8 ± 6.4 (5.5–38.9) |

Median.

Three neonates were treated with two separate courses of vancomycin during the study period, with each respective indication accounted for in each course of antibiotic received (thus, n = 53).

Trough concentrations were extrapolated to the end of the dosing interval using first-order kinetic equations.

NEC, necrotizing enterocolitis.

TABLE 2.

Bacterial isolates from positive cultures around the start of vancomycin treatment

| Organism(s) | No. of isolates (%) (n = 50)a | No. (%) of isolates from indicated source of culture |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | Sputum | Urine | Line | Wound | ||

| Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus spp. | 36 (72) | 23 (46) | 6 (12) | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | 4 (8) |

| Methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Enterococcus spp. | 4 (8) | 0 | 0 | 4 (8) | 0 | 0 |

| Beta-hemolytic Streptococcus, group B | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 |

| Gram-negative organismsb | 5 (10) | 1 (2) | 3 (6) | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 |

| Otherc | 3 (6) | 0 | 2 (4) | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 |

All percentages were determined from the total number of isolates (n = 50) in the denominator.

There was a total of 5 Gram-negative organisms, including Escherichia coli (2), Klebsiella spp. (1), and Enterobacter spp. (2).

There was a total of 3 other organisms, including Bacillus cereus, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and Ureaplasma urealyticus.

TABLE 3.

Mean pharmacokinetic parametersa

| Parameter | Mean | 95% CI | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| kel (h−1) | 0.1103 | 0.1011–0.1195 | 0.0278–0.2022 |

| t1/2 (h) | 6.3 | 5.4–7.2 | 3.4–25.0 |

| V (liters) | 0.68 | 0.60–0.77 | 0.32–1.94 |

| V (liters/kg) | 0.61 | 0.57–0.66 | 0.36–1.30 |

| CL (liters/h) | 0.075 | 0.062–0.089 | 0.025–0.250 |

| CL (liters/h/kg) | 0.068 | 0.061–0.074 | 0.033–0.130 |

| AUC24 (mg/h/liter) | 449 | 409–489 | 264–979 |

Fifty-eight sets of vancomycin levels from 50 patients were tested. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Univariate and multivariate analyses.

Statistically significant predictors (P < 0.2) of vancomycin V (liters) and CL (liters/h) identified by univariate analysis are detailed in Table 4. The only covariates that remained statistically significant following MLR for V (liters) were PNA (P < 0.001) and birth weight (P < 0.001). The model that best predicted V (P < 0.001 and R2 = 0.695) with MLR was a V (liters) of −0.154 plus 0.013 (the PNA at the time of vancomycin initiation in days) plus 0.679 (the birth weight in kg). Covariates that remained statistically significant following MLR for CL (liters/h) included PNA (P < 0.001), birth weight (P < 0.001), weight at the time closest to vancomycin initiation (P = 0.006), and albumin at baseline (P = 0.004). The model that best predicted CL (P < 0.001 and R2 = 0.848) was a CL (liters/h) of −0.115 plus 0.003 (the PNA at vancomycin initiation in days) plus 0.066 (the birth weight in kg) plus 0.002 (baseline albumin in g/liter) plus 0.019 (weight closest to the time of vancomycin initiation in kg).

TABLE 4.

Parameters assessed by univariate and multivariate analyses

| Parameter | Clearance |

Volume of distribution |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate P valuea | Multivariate P valueb | Univariate P valuea | Multivariate P valueb | |

| Gender | 0.011 | 0.867 | 0.013 | 0.631 |

| Gestational age (wk) | 0.001 | 0.261 | <0.001 | 0.637 |

| Postnatal age (days) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.013 | <0.001 |

| Corrected gestational age (wk) | <0.001 | 0.262 | <0.001 | 0.639 |

| Apgar score at 1 min | 0.589 | 0.207 | ||

| Apgar score at 5 min | 0.314 | 0.506 | ||

| Birth wt (kg) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Small-for-gestational-age status | 0.272 | 0.292 | ||

| Wt closest to vancomycin initiation (kg) | <0.001 | 0.006 | <0.001 | 0.837 |

| No. of days in NICU prior to vancomycin initiation | <0.001 | 0.192 | 0.059 | 0.692 |

| No. of days from birth to vancomycin initiation | <0.001 | >0.999 | 0.013 | >0.999 |

| BUN at baseline | 0.138 | 0.881 | 0.037 | 0.818 |

| Serum creatinine at baseline | 0.010 | 0.470 | 0.001 | 0.306 |

| Serum creatinine at vancomycin initiation | <0.001 | 0.209 | 0.219 | |

| Albumin at baseline | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.011 | 0.157 |

| 24-h urine output at baseline (ml/h) | 0.001 | 0.371 | <0.001 | 0.470 |

| 24-h urine output at vancomycin initiation | 0.006 | 0.619 | 0.002 | 0.583 |

Covariates for which the P value was <0.2 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis.

Covariate values that remained significantly different (P < 0.05) after multivariate analysis were used to determine the best-fit model to predict CL and V.

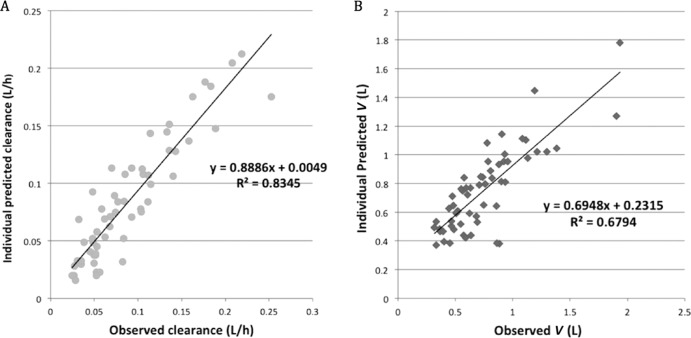

CART analysis.

CART was not used in the analysis, since the predicted CL (liters/h) and V (liters) values determined from the derived MLR equations for the population analyzed showed good predictive performance, with R2 values of 0.83 and 0.68, respectively (Fig. 1A and B), and a continuous linear relationship for predicted versus observed CL and V scatterplots. Therefore, clinically relevant breakpoints for vancomycin CL (liters/h) or V (liters) in neonates do not exist for any input parameters used to predict CL and V from the regression equations derived in this study.

FIG 1.

Scatterplots of individual patient predicted (based on multiple linear regression model equation) versus observed CL (liter/h) (A) and V (liters) (B).

Monte Carlo simulation.

MCS of dosing regimens in milligrams for intermittent and continuous infusion in neonates consistently had a poorer probability of plasma target concentration attainment than weight-based (mg/kg) regimens (Tables 5 to 9). For the initial dosing regimen commonly used in our neonatal patients (10 mg/kg i.v. q8h) at the time of this study, MCS indicated an achievement of target trough levels of 15 to 20 mg/liter, 5 to 20 mg/liter, and ≤20 mg/liter in 18%, 79%, and 85% of patients, respectively (Table 5). The probabilities of reaching the target trough level of 15 to 20 mg/liter in neonates with adequate renal function were 15 to 23% and 15 to 21% for patients administered 6 to 8 mg/kg i.v. q6h and 9 to 12 mg/kg i.v. q8h, respectively (Table 5). Correspondingly, the probabilities of reaching a target AUC/MIC ratio of ≥400 in neonates with adequate renal function were 38 to 60% and 47 to 69% for patients administered 6 to 8 mg/kg i.v. q6h and 9 to 12 mg/kg i.v. q8h, respectively (Table 5). Since the probabilities of achieving the predefined targets proposed in our study were similar in simulations using mg/kg dosing q6h and q8h, 9 to 12 mg/kg i.v. q8h was selected as a reasonable initial dosing regimen based on administration convenience. If a loading dose is desired for a hemodynamically unstable critically ill neonate, MCS showed that 25 mg/kg was optimal for intermittent-infusion vancomycin dosing (Table 7). When continuous-infusion regimens were explored, a loading dose of 10 mg/kg with an infusion of 25 to 30 mg/kg/24 h offered the highest probability (28 to 32% of patients) of attaining a target steady-state concentration between 15 and 20 mg/liter (Table 8). The probability of reaching target trough concentrations between 5 and 20 mg/liter or ≤20 mg/liter was adequate with dosing of 9 to 15 mg/kg i.v. q12h (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Monte Carlo simulation results for intermittent infusiona

| Time of intermittent infusion | Dosing regimen (mg/kg) | Total daily dose (mg)b | % probability of attaining the following target: |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trough concn of ≤8 mg/liter (goal: ≤25%) | Trough concn of ≤12 mg/liter (goal: ≤25%) | Trough concn of 5–20 mg/liter (goal: ≥70%) | Trough concn of 15–20 mg/liter (goal: ≥70%) | Trough concn of ≤20 mg/liter (goal: ≥70%) | Trough concn of ≥25 mg/liter (goal: <10%) | Peak concn of ≤40 mg/liter (goal: ≥70%) | Peak concn of ≥80 mg/liter (goal: <10%) | AUC24/MICc of ≥400 (goal: ≥70%) | |||

| q6h | 5 | 20 | 39.6 | 72.6 | 84.8 | 9.6 | 95.8 | 1.3 | 99.5 | 0.0 | 25.6 |

| 6 | 24 | 25.9 | 58.2 | 85.0 | 15.3 | 90.7 | 3.4 | 98.1 | 0.0 | 38.2 | |

| 7 | 28 | 17.0 | 45.3 | 80.6 | 19.8 | 83.6 | 7.0 | 95.1 | 0.0 | 49.9 | |

| 8 | 32 | 11.0 | 34.4 | 73.7 | 22.6 | 75.4 | 12.0 | 89.9 | 0.1 | 60.2 | |

| 9 | 36 | 7.3 | 26.0 | 65.7 | 23.9 | 66.7 | 18.0 | 82.7 | 0.2 | 69.0 | |

| 10 | 40 | 4.8 | 19.6 | 57.6 | 23.7 | 58.2 | 24.6 | 74.0 | 0.5 | 76.0 | |

| 11 | 44 | 3.3 | 14.7 | 49.8 | 22.6 | 50.1 | 31.5 | 64.4 | 1.0 | 81.6 | |

| 12 | 48 | 2.2 | 11.1 | 42.7 | 21.0 | 42.9 | 38.4 | 54.8 | 1.9 | 86.0 | |

| 13 | 52 | 1.5 | 8.3 | 36.2 | 19.0 | 36.3 | 45.2 | 45.4 | 3.2 | 89.3 | |

| 14 | 56 | 1.1 | 6.3 | 30.8 | 17.0 | 30.8 | 51.3 | 37.1 | 4.9 | 91.8 | |

| 15 | 60 | 0.8 | 4.8 | 26.0 | 15.0 | 26.0 | 57.1 | 29.7 | 7.3 | 93.8 | |

| q8h | 6 | 18 | 58.3 | 85.0 | 74.1 | 4.9 | 98.3 | 0.4 | 99.7 | 0.0 | 19.7 |

| 7 | 21 | 46.2 | 76.4 | 80.1 | 8.2 | 96.4 | 1.1 | 98.8 | 0.0 | 28.8 | |

| 8 | 24 | 36.2 | 67.3 | 82.4 | 11.7 | 93.4 | 2.4 | 97.0 | 0.0 | 38.1 | |

| 9 | 27 | 28.2 | 58.4 | 82.1 | 15.1 | 89.6 | 4.2 | 93.8 | 0.0 | 47.1 | |

| 10 | 30 | 21.9 | 50.1 | 79.3 | 17.8 | 85.0 | 6.6 | 89.1 | 0.07 | 55.3 | |

| 11 | 33 | 17.1 | 42.7 | 76.3 | 19.9 | 80.0 | 9.6 | 82.9 | 0.15 | 62.7 | |

| 12 | 36 | 13.3 | 36.1 | 71.8 | 21.4 | 74.5 | 13.1 | 75.4 | 0.35 | 69.1 | |

| 13 | 39 | 10.5 | 30.6 | 67.1 | 22.1 | 69.1 | 17.0 | 67.4 | 0.7 | 74.4 | |

| 14 | 42 | 8.3 | 25.9 | 62.2 | 22.3 | 63.6 | 21.1 | 59.0 | 1.2 | 79.0 | |

| 15 | 45 | 6.6 | 21.9 | 57.2 | 22.1 | 58.3 | 25.4 | 50.7 | 1.9 | 82.8 | |

| q12h | 5 | 10 | 96.1 | 99.5 | 19.2 | 0.1 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 2.3 |

| 6 | 12 | 92.1 | 98.6 | 29.5 | 0.3 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 5.0 | |

| 7 | 14 | 86.8 | 97.2 | 39.4 | 0.8 | 99.8 | 0.0 | 99.9 | 0.0 | 9.0 | |

| 8 | 16 | 80.8 | 94.9 | 48.3 | 1.5 | 99.6 | 0.1 | 99.6 | 0.0 | 13.9 | |

| 9 | 18 | 74.3 | 92.1 | 55.8 | 2.5 | 99.2 | 0.2 | 99.0 | 0.0 | 19.6 | |

| 10 | 20 | 67.9 | 88.7 | 62.0 | 3.7 | 98.7 | 0.4 | 97.8 | 0.0 | 25.7 | |

| 11 | 22 | 61.6 | 84.8 | 66.9 | 5.2 | 97.8 | 0.7 | 95.7 | 0.0 | 32.0 | |

| 12 | 24 | 55.7 | 80.7 | 70.5 | 6.7 | 96.8 | 1.1 | 92.5 | 0.0 | 38.2 | |

| 13 | 26 | 50.2 | 76.4 | 73.1 | 8.2 | 95.4 | 1.6 | 88.3 | 0.0 | 44.2 | |

| 14 | 28 | 45.3 | 72.1 | 74.8 | 9.8 | 93.9 | 2.4 | 83.1 | 0.1 | 50.0 | |

| 15 | 30 | 40.7 | 67.9 | 75.7 | 11.3 | 92.1 | 3.3 | 76.8 | 0.2 | 55.4 | |

| 16 | 32 | 36.6 | 63.6 | 76.0 | 12.8 | 90.1 | 4.3 | 70.0 | 0.4 | 60.4 | |

| 18 | 34 | 29.7 | 55.6 | 75.0 | 15.3 | 85.6 | 6.8 | 55.6 | 1.0 | 69.0 | |

| 20 | 36 | 24.3 | 48.6 | 72.7 | 17.1 | 80.8 | 9.8 | 42.0 | 2.2 | 76.0 | |

Dosing was in mg/kg. The weight range was limited to 0.4 to 6 kg. Shading indicates dosing regimens that attained the best probability of desired target concentration attainment, while minimizing undesirably high or low concentrations.

Total daily dose for a 1-kg neonate.

Assuming a MIC range of 0.5 to 2 mg/liter, with a mean MIC of 1 mg/liter. AUC24, area under the 24-h serum concentration-time curve.

TABLE 9.

Monte Carlo simulation results for continuous infusion with mg dosinga

| Dosing regimen | % probability of attaining the following target: |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post LD of 12–25 mg/liter (goal: ≥70%) | Post LD of 15–20 mg/liter (goal: ≥70%) | Post LD of >25 mg/liter (goal: <10%) | Css of ≤12 mg/liter (goal: ≤25%) | Css of 15–20 mg/liter (goal: ≥70%) | Css ≥25 mg/liter (goal: <10%) | AUC24/MIC of ≥400b (goal: ≥70%) | |

| 5-mg LD | 12.3 | 4.6 | 0.5 | ||||

| 7-mg LD | 24.9 | 9.5 | 3.3 | ||||

| 9-mg LD | 36.4 | 14.2 | 8.4 | ||||

| 10-mg LD | 41.3 | 16.4 | 11.5 | ||||

| 11-mg LD | 45.4 | 18.3 | 14.8 | ||||

| 20-mg LD | 44.9 | 18.9 | 49.7 | ||||

| 15 mg/24 h | 84.5 | 5.3 | 1.2 | 10.8 | |||

| 20 mg/24 h | 71.2 | 9.4 | 4.1 | 20.0 | |||

| 25 mg/24 h | 57.4 | 13.4 | 8.6 | 29.8 | |||

| 30 mg/24 h | 44.7 | 16.6 | 14.0 | 39.4 | |||

AUC24, area under the 24-h serum concentration-time curve; Css, steady-state serum concentration; LD, loading dose.

We assumed a MIC range of 0.5 to 2 mg/liter, with a mean MIC of 1 mg/liter.

TABLE 7.

Monte Carlo simulation for intermittent-infusion mg/kg loading dosesa

| LD (mg/kg) | % probability of attaining the following target: |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trough concn post LD of ≤8 mg/liter (goal: ≤25%) | Trough concn post LD of ≤12 mg/liter (goal: ≤25%) | Trough concn post LD of 5–20 mg/liter (goal: ≥70%) | Trough concn post LD of 15–20 mg/liter (goal: ≥70%) | Trough concn post LD of ≤20 mg/liter (goal: ≥70%) | Trough concn post LD of ≥25 mg/liter (goal: <10%) | Peak LD of ≤40 mg/liter (goal: ≥70%) | Peak LD of ≥80 mg/liter (goal: <10%) | |

| 15 | 29.0 | 70.2 | 93.0 | 9.9 | 98.0 | 0.3 | 96.9 | 0.0 |

| 16 | 23.8 | 63.7 | 93.0 | 13.0 | 96.8 | 0.6 | 94.7 | 0.0 |

| 20 | 10.6 | 40.1 | 86.6 | 24.2 | 87.9 | 3.3 | 77.6 | 0.0 |

| 25 | 4.2 | 20.1 | 69.8 | 30.1 | 70.2 | 12.0 | 46.2 | 0.5 |

| 30 | 1.8 | 10.7 | 51.0 | 27.4 | 51.2 | 26.0 | 21.2 | 3.1 |

LD, loading dose. Shading indicates dosing regimens that attained the best probability of desired target concentration attainment, while minimizing undesirably high or low concentrations.

TABLE 8.

Monte Carlo Simulation results for continuous infusion with mg/kg dosinga

| Dosing regimenb | % probability of attaining the following target: |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post LD of 12–25 mg/liter (goal: ≥70%) | Post LD of 15–20 mg/liter (goal: ≥70%) | Post LD of >25 mg/liter (goal: <10%) | Css of ≤12 mg/liter (goal: ≤25%) | Css of 15–20 mg/liter (goal: ≥70%) | Css of ≥25 mg/liter (goal: <10%) | AUC24/MICc of ≥400 (goal: ≥70%) | |

| 5-mg/kg LD | 7.6 | 1.1 | 0.0 | ||||

| 7-mg/kg LD | 43.0 | 13.7 | 0.2 | ||||

| 9-mg/kg LD | 76.3 | 35.2 | 2.2 | ||||

| 10-mg/kg LD | 83.1 | 40.9 | 5.4 | ||||

| 11-mg/kg LD | 83.7 | 41.3 | 10.6 | ||||

| 12-mg/kg LD | 79.3 | 37.6 | 18.0 | ||||

| 15-mg/kg LD | 52.6 | 18.8 | 47.5 | ||||

| 20-mg/kg LD | 14.7 | 2.5 | 85.3 | ||||

| 15 mg/kg/24 h | 84.2 | 4.2 | 0.0 | 11.3 | |||

| 20 mg/kg/24 h | 56.6 | 16.2 | 1.0 | 25.7 | |||

| 25 mg/kg/24 h | 32.2 | 27.5 | 4.8 | 41.2 | |||

| 27 mg/kg/24 h | 24.9 | 30.2 | 7.5 | 47.1 | |||

| 28 mg/kg/24 h | 21.8 | 30.9 | 9.3 | 50.0 | |||

| 29 mg/kg/24 h | 19.0 | 31.5 | 11.0 | 52.7 | |||

| 30 mg/kg/24 h | 16.6 | 31.7 | 13.1 | 55.4 | |||

| 32 mg/kg/24 h | 12.5 | 31.4 | 17.5 | 60.3 | |||

| 35 mg/kg/24 h | 8.1 | 29.4 | 25.1 | 66.9 | |||

AUC24, area under the 24-h serum concentration-time curve; Css, steady-state serum concentration; LD, loading dose. Shading indicates dosing regimens that attained the best probability of desired target concentration attainment, while minimizing undesirably high or low concentrations.

The weight range was limited to 0.4 to 6 kg.

We assumed a MIC range of 0.5 to 2 mg/liter, with a mean MIC of 1 mg/liter.

TABLE 6.

Monte Carlo simulation results for intermittent infusion with milligram dosesa

| Time of intermittent infusion | Dosing regimen (mg) | Total daily dose (mg) | % probability of attaining the following target: |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trough concn of ≤8 mg/liter (goal: ≤25%) | Trough concn of ≤12 mg/liter (goal: ≤25%) | Trough concn of 5–20 mg/liter (goal: ≥70%) | Trough concn of 15–20 mg/liter (goal: ≥70%) | Trough concn of ≤20 mg/liter (goal: ≥70%) | Trough concn of ≥25 mg/liter (goal: <10%) | Peak concn of ≤40 mg/liter (goal: ≥70%) | Peak concn of ≥80 mg/liter (goal: <10%) | AUC24/MICb of ≥400 (goal: ≥70%) | |||

| q6h | 6 | 24 | 47.4 | 70.7 | 69.1 | 9.3 | 90.1 | 5.3 | 94.8 | 0.2 | 27.8 |

| 7 | 28 | 38.0 | 62.3 | 71.0 | 11.6 | 85.6 | 8.3 | 91.5 | 0.5 | 35.6 | |

| 8 | 32 | 30.3 | 54.5 | 70.5 | 13.5 | 80.8 | 11.6 | 87.7 | 1.0 | 43.0 | |

| 9 | 36 | 24.2 | 47.4 | 68.5 | 15.0 | 75.7 | 15.3 | 83.5 | 1.7 | 49.8 | |

| 10 | 40 | 19.2 | 40.9 | 65.4 | 16.2 | 70.6 | 19.2 | 79.0 | 2.7 | 56.0 | |

| 11 | 44 | 15.3 | 35.3 | 61.9 | 16.9 | 65.6 | 23.2 | 74.4 | 3.9 | 61.5 | |

| 12 | 48 | 12.3 | 30.4 | 58.0 | 17.3 | 60.7 | 27.3 | 69.7 | 5.2 | 66.4 | |

| 13 | 52 | 9.8 | 26.1 | 54.1 | 17.5 | 56.1 | 31.3 | 65.1 | 6.8 | 70.7 | |

| 14 | 56 | 7.9 | 22.4 | 50.0 | 17.4 | 51.6 | 35.3 | 60.4 | 8.5 | 74.5 | |

| 15 | 60 | 6.4 | 19.2 | 46.2 | 17.0 | 47.3 | 39.3 | 55.7 | 10.4 | 77.9 | |

| 16 | 64 | 5.2 | 16.6 | 42.5 | 16.5 | 43.4 | 43.0 | 51.3 | 12.3 | 80.7 | |

| 17 | 68 | 4.2 | 14.2 | 39.2 | 16.0 | 39.8 | 46.6 | 47.1 | 14.3 | 83.2 | |

| 18 | 72 | 3.5 | 12.3 | 35.9 | 15.4 | 36.4 | 50.1 | 43.1 | 16.5 | 85.4 | |

| q8h | 6 | 18 | 70.6 | 86.9 | 52.5 | 4.3 | 96.8 | 1.4 | 97.6 | 0.0 | 16.1 |

| 7 | 21 | 62.4 | 81.6 | 59.4 | 6.0 | 94.8 | 2.5 | 95.6 | 0.1 | 22.0 | |

| 8 | 24 | 54.9 | 76.1 | 64.2 | 7.6 | 92.5 | 3.9 | 93.1 | 0.3 | 27.8 | |

| 9 | 27 | 48.0 | 70.6 | 67.1 | 9.2 | 89.8 | 5.7 | 90.1 | 0.6 | 33.6 | |

| 10 | 30 | 41.9 | 65.1 | 68.7 | 10.7 | 86.8 | 7.6 | 86.8 | 1.0 | 39.4 | |

| 11 | 33 | 36.4 | 60.0 | 69.1 | 12.0 | 83.7 | 9.7 | 83.4 | 1.7 | 44.8 | |

| 12 | 36 | 31.6 | 54.9 | 68.7 | 13.2 | 80.5 | 12.0 | 79.7 | 2.4 | 49.9 | |

| 13 | 39 | 27.5 | 50.3 | 67.6 | 14.1 | 77.2 | 14.5 | 75.8 | 3.4 | 54.5 | |

| 14 | 42 | 23.8 | 45.8 | 66.1 | 15.0 | 73.9 | 16.9 | 71.9 | 4.4 | 58.9 | |

| 15 | 45 | 20.8 | 41.8 | 64.1 | 15.7 | 70.6 | 19.5 | 68.0 | 5.6 | 62.9 | |

| 16 | 48 | 18.1 | 38.1 | 62.0 | 16.1 | 67.2 | 22.2 | 64.0 | 7.0 | 66.5 | |

| 17 | 51 | 15.8 | 34.7 | 59.7 | 16.4 | 64.0 | 24.8 | 60.1 | 8.4 | 69.8 | |

| 18 | 54 | 13.9 | 31.7 | 57.3 | 16.7 | 60.9 | 27.5 | 56.3 | 9.9 | 72.7 | |

| q12h | 6 | 12 | 92.0 | 97.5 | 21.6 | 0.8 | 99.7 | 0.1 | 99.3 | 0.0 | 6.0 |

| 7 | 14 | 88.5 | 96.0 | 27.9 | 1.3 | 99.3 | 0.2 | 98.4 | 0.0 | 9.0 | |

| 8 | 16 | 84.7 | 94.1 | 33.8 | 1.9 | 98.9 | 0.4 | 97.1 | 0.0 | 12.4 | |

| 9 | 18 | 80.6 | 92.0 | 39.3 | 2.6 | 98.3 | 0.7 | 95.4 | 0.1 | 16.1 | |

| 10 | 20 | 76.3 | 89.6 | 44.2 | 3.4 | 97.5 | 1.1 | 93.3 | 0.2 | 20.1 | |

| 11 | 22 | 72.4 | 87.2 | 48.3 | 4.2 | 96.6 | 1.6 | 91.1 | 0.4 | 23.8 | |

| 12 | 24 | 68.1 | 84.5 | 52.1 | 5.0 | 95.6 | 2.2 | 88.5 | 0.7 | 28.0 | |

| 13 | 26 | 64.2 | 81.9 | 55.2 | 5.8 | 94.5 | 2.8 | 85.8 | 1.1 | 31.8 | |

| 14 | 28 | 60.5 | 79.1 | 57.7 | 6.6 | 93.3 | 3.6 | 83.0 | 1.6 | 35.6 | |

| 15 | 30 | 56.8 | 76.4 | 59.9 | 7.5 | 92.1 | 4.3 | 80.0 | 2.2 | 39.4 | |

| 16 | 32 | 53.4 | 73.6 | 61.5 | 8.3 | 90.7 | 5.2 | 76.9 | 2.9 | 43.0 | |

| 17 | 34 | 50.2 | 70.9 | 62.7 | 8.9 | 89.2 | 6.2 | 73.8 | 3.7 | 46.5 | |

| 18 | 36 | 47.0 | 68.2 | 63.8 | 9.7 | 87.7 | 7.2 | 70.7 | 4.6 | 49.9 | |

Shading indicates dosing regimens that attained the best probability of desired target concentration attainment, while minimizing undesirably high or low concentrations.

Assuming a MIC range of 0.5 to 2 mg/liter, with a mean MIC of 1 mg/liter. AUC24, area under the 24-h serum concentration-time curve.

DISCUSSION

While vancomycin has been used for more than 60 years, controversy continues regarding optimal PK/PD targets, dosing, and monitoring in adult and pediatric patients. Previous published data evaluating vancomycin pharmacokinetics in neonates are based on small, heterogeneous populations where trough concentration targets were not those currently used in clinical practice. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the pharmacokinetics of vancomycin in neonates, identify significant covariates of vancomycin pharmacokinetics in neonates, and develop a practical initial-dosing recommendation with the highest probability of attaining plasma levels which are currently most commonly targeted among NICUs (trough concentrations of 15 to 20 mg/liter, 5 to 20 mg/liter, and ≤20 mg/liter with intermittent dosing and a steady-state concentration of 15 to 20 mg/liter with continuous infusion).

Our study included 50 neonates and a total of 58 sets of vancomycin levels to determine neonatal vancomycin pharmacokinetics (Table 3). The mean vancomycin half-life was 6.3 h, with a mean V of 0.61 liters/kg. We identified significant (P < 0.05) covariates of both vancomycin CL (PNA [days], birth weight [kg], weight closest to vancomycin initiation [kg], and albumin at baseline [g/liter]) and V (PNA [days] and birth weight [kg]). Although the models for both V (liters) and CL (liters/h) had a good predictive capability (Fig. 1A and B), the derived equations would be cumbersome to use in clinical practice since a number of parameters would need to be identified and put into complex equations for V and CL, following which the calculated V and CL would need be put into first-order equations to determine initial vancomycin dosing. Using MCS (1 million iterations), initial vancomycin dosing of either 6 to 8 mg/kg i.v. q6h or 9 to 12 mg/kg i.v. q8h had the best probability of attaining a target trough concentration of 15 to 20 mg/liter. However, due to large interpatient vancomycin pharmacokinetic variability, the probability of target attainment with either dosing regimen was less than 25% when the narrow target trough concentration of 15 to 20 mg/liter was desired, a finding similar to that of Mehrotra et al. (18), who evaluated 10 mg vancomycin/kg i.v. q8h in neonates. This observation supports the continued need for individualized pharmacokinetics (peak and trough concentrations) to determine optimal maintenance dosing for vancomycin in neonates when the target trough concentration is 15 to 20 mg/liter. In hemodynamically unstable, acutely ill neonates, a loading dose may be desirable to attain target trough concentrations within the first 24 h of therapy. If a loading dose is desired, then our findings showed that 25 mg/kg provided the best probability of attaining the target trough concentrations of 15 to 20 mg/liter. For target trough concentrations of 5 to 20 mg/liter and ≤20 mg/liter, our study found that 9 to 15 mg/kg i.v. q12h was adequate to achieve the targets (56 to 76% and 92 to 99%, respectively). For reasons of practicality, we recommend a dosing regimen of 10-mg/kg vancomycin i.v. q12h for vancomycin trough concentrations of either 5 to 20 mg/liter or ≤20 mg/liter or 10-mg/kg vancomycin i.v. q8h for trough concentrations of 15 to 20 mg/liter. Dosing recommendations using continuous-infusion mg/kg vancomycin dosing were also derived in our study and provided a consistently higher probability of attaining a steady-state level between 15 and 20 mg/liter. However, continuous-infusion vancomycin therapy may be logistically problematic in the neonatal population due to limited i.v. access.

Our study observed vancomycin pharmacokinetic parameters similar to those of previous studies in neonates (6, 18, 32). Birth weight (kg) and PNA (days) were identified as significant predictors of vancomycin V in this study. Other studies determined that weight at the time of vancomycin initiation and CGA were covariates of V (14, 16, 17, 46). The difference in findings may be explained by the various levels of the clinical conditions of neonates in previous studies, where neonates admitted to level III NICUs would have the highest severity of illness, resulting in rapid fluid shifts and large variability in vancomycin V's. PNA, birth weight, weight at the time of vancomycin initiation, and baseline albumin were identified as significant covariates of vancomycin CL in this study. In a recent population pharmacokinetic analysis of 214 neonates, significant covariates of vancomycin CL were found to be weight at the time of vancomycin initiation, CGA, and renal function (47). CGA has been considered to be a better predictor of clearance than gestational age or PNA alone, as CGA is highly correlated to weight and physiological maturation of renal function (8, 18). However, CGA was not identified as a significant covariate of vancomycin CL in our population, most likely due to the small variability in gestational ages in our study. Serum creatinine, as a surrogate marker of renal function, was not identified as a significant covariate in vancomycin clearance in this study. Changes in the development of renal function in neonates are correlated with CGA, and renal function increases after the first 1 to 2 weeks of life (48). Most of the neonates in this study were initiated on vancomycin for late-onset infection (after 3 days of age), and the mean PNA at vancomycin initiation was 17 days (Table 1). As a result, renal function may not have been identified as a significant covariate in our model, since we were unlikely to have captured neonates with significant interindividual differences in renal elimination. We are not aware of any other neonatal or pediatric study that has found serum albumin to be a significant covariate of vancomycin clearance.

All previous studies that evaluated dosing requirements in this population used weight-based dosing but did not evaluate the probability of achieving the targets with non-weight-based (fixed-dosage-based) regimens in neonates. Since weight was a significant covariate for both V and CL, we hypothesized that mg-based dosing would decrease the probability of attaining target trough levels. MCS confirmed that mg-based dosing for both intermittent and continuous infusion reduced the predicted probability of attaining target vancomycin trough concentrations of 15 to 20 mg/liter, 5 to 20 mg/liter, and ≤20 mg/liter compared to mg/kg dosing in neonates. Therefore, we removed the fixed-dosage regimens to simplify both our intermittent and continuous-infusion vancomycin dosing recommendations in neonates.

At the time of this study, two neonatal studies assessed vancomycin dosing requirements to meet the higher target trough concentrations of 15 to 20 mg/liter. Lo et al. (15) provided a dosing nomogram (mg/kg) that accounted for CGA and SGA status. However, these recommendations are based on MCS's targeting trough concentrations of 5 to 20 mg/liter and may delay appropriate antibiotic therapy to critically ill neonates when targets of 15 to 20 mg/liter may be optimal. Mehrotra et al. (18) explored various serum creatinine-based dosing nomograms to achieve the target trough concentrations of 15 to 20 mg/liter using MCS. Predictability of vancomycin CL using a serum creatinine-based dosing nomogram may be limited, as creatinine in the first week of life reflects residual maternal creatinine, and in preterm neonates the decline in serum creatinine occurs at a lower rate than in full-term neonates (49). Our study is the first study in neonates that assessed initial vancomycin dosing requirements for both intermittent and continuous-infusion dosing for targeted concentrations (trough and steady state, respectively) between 15 and 20 mg/liter. In addition to the published studies by Lo et al. (15) and Mehrotra et al. (18), our study demonstrates that the attainment of the narrow target of 15 to 20 mg/liter is challenging in neonates and further emphasizes the need for serum monitoring and subsequent dosage adjustments. Future studies are needed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the dosing recommendations made in this study, and the feasibility of continuous-infusion dosing in NICUs needs to be further explored when the target of 15 to 20 mg/liter is difficult to attain with intermittent dosing.

Since this is a retrospective study, we had little control over potential confounders. Specific study design limitations that may bias our results included the following: (i) assumptions of apparent steady-state vancomycin peak and trough concentrations; (ii) assumptions of the timing of vancomycin dosing and timing of serum samples; (iii) the determination of vancomycin total body clearance by calculation, rather than by direct measure from blood and urine collection; (iv) the determination of area under the curve by calculation, based on a 1-compartment model (with only 2 blood samples per patient, obtained at relatively consistent time points relative to dosing) rather than by generation of a complete serum concentration-versus-time profile for vancomycin in each patient; (v) extrapolations from adult recommendations for the need of higher target trough concentrations for complicated MRSA infections; and (vi) assumptions of generalizability to other neonates in other NICUs. A prospective clinical trial to validate the recommended dosing regimens and evaluate the safety and efficacy of the proposed dosing strategies in our study is required.

Conclusions.

Initial intermittent vancomycin dosing of 9 to 12 mg/kg i.v. q8h in neonates with adequate renal function maximizes the probability of attaining vancomycin trough concentrations of 15 to 20 mg/liter. However, the probability of attaining this narrow target range remains low due to large interpatient vancomycin pharmacokinetic variability. This observation supports the continued need for individualized vancomycin pharmacokinetics (peak and trough concentrations) to determine optimal maintenance dosing for vancomycin in neonates when the target trough concentration is 15 to 20 mg/liter. We recommend a dosing regimen of 10 mg/kg vancomycin i.v. q12h for desired vancomycin trough concentrations of either 5 to 20 mg/liter or ≤20 mg/liter or a dose of 10 mg/kg vancomycin i.v. q8h for a target trough concentration of 15 to 20 mg/liter. Dosing recommendations using continuous-infusion mg/kg vancomycin dosing were also derived in our study and resulted in a consistently higher probability of attaining a steady-state level between 15 and 20 mg/liter. However, continuous-infusion vancomycin therapy may be logistically problematic in the neonatal population. A prospective clinical trial to validate the recommended dosing regimens and evaluate the safety and efficacy of the proposed dosing strategies identified in our study is required.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Sincere thanks go to Nick Daneman, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Department of Microbiology and Division of Infectious Diseases, for reviewing the manuscript and providing constructive feedback.

We have no competing interest and funding to declare.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 10 March 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Stoll BJ, Hansen N, Fanaraoff AA, Carlo WA, Ehrenkranz RA, Lemons JA, Donovan EF, Stark AR, Tyson JE, Oh W, Bauer CR, Korones SB, Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Stevenson DK, Papile LA, Poole WK. 2002. Late-onset sepsis in very low birth weight neonates: the experiences of the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics 110:285–291. 10.1542/peds.110.2.285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark R, Powers R, White R, Bloom B, Sánchez P, Benjamin DK., Jr 2004. Nosocomial infection the NICU: a medical complication or unavoidable problem. J. Perinatol. 24:382–388. 10.1038/sj.jp.7211120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubin LG, Sánchez PJ, Siegel J, Levine G, Saiman L, Jarvis WR. 2002. Evaluation and treatment of neonates with suspected late-onset sepsis: a survey of neonatologists' practices. Pediatrics 110(4):e42. 10.1542/peds.110.4.e42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, Daum RS, Fridkin SK, Gorwiwtz RJ, Kaplan SL, Karchmer AW, Levine DP, Murray BE, Rybak MJ, Talan DA, Chambers HF. 2011. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children. Clin. Infect. Dis. 52:285–292. 10.1093/cid/cir034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rybak M, Lomaestro B, Rotschafer J, Moellering R, Jr, Craig W, Billeter M, Dalovisio JR, Levine DP. 2009. Therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin in adult patients: a consensus review of American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 66:82–98. 10.2146/ajhp080434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodvold KA, Everett JA, Pryka RD, Kraus DM. 1997. Pharmacokinetics and administration regimens of vancomycin in neonates, infants and children. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 33:32–51. 10.2165/00003088-199733010-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marsot A, Boulamery A, Bruguerolle B, Simon N. 2012. Vancomycin a review of population pharmacokinetic analyses. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 51:1–13. 10.2165/11596390-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Hoog M, Schoemaker RC, Mouton JW, van den Anker JN. 2000. Vancomycin population pharmacokinetics in neonates. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 67:360–367. 10.1067/mcp.2000.105353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Capparelli EV, Lane JR, Romanowski GL, McFeely EJ, Murray W, Sousa P, Kildoo C, Connor JD. 2001. The influences of renal function and maturation on vancomycin elimination in newborns and infants. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 41:927–934. 10.1177/00912700122010898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gabriel MH, Kildoo GC, Gennrich JL, Mondanlou HD, Collins SR. 1991. Prospective evaluation of a vancomycin dosage guidelines for neonates. Clin. Pharm. 10:129–132 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grimsley C, Thomson AH. 1999. Pharmacokinetics and dose requirements of vancomycin in neonates. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 81:F221–F227. 10.1136/fn.81.3.F221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.James A, Koren G, Milliken J, Soldin S, Prober C. 1987. Vancomycin pharmacokinetics and dose recommendations for preterm infants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 31:52–54. 10.1128/AAC.31.1.52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimura T, Sunakawa K, Matsuura N, Kubo H, Shimada S, Yago K. 2004. Population pharmacokinetics of arbekacin, vancomycin, and panipenem in neonates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1159–1167. 10.1128/AAC.48.4.1159-1167.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lisby-Sutch SM, Nahata MC. 1988. Dosage guidelines for the use of vancomycin based on its pharmacokinetics in infants. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 35:637–642. 10.1007/BF00637600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lo Y-L, van Hasselt JG, Heng SC, Lim CT, Lee TC, Charles BG. 2010. Population pharmacokinetics of vancomycin in premature Malaysian neonates: identification of predictors for dosing determination. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:2626–2632. 10.1128/AAC.01370-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDougal A, Ling EW, Levine M. 1995. Vancomycin pharmacokinetics and dosing in premature neonates. Ther. Drug Monit. 17:319–326. 10.1097/00007691-199508000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reed MD, Kliegman RM, Weiner JS, Huang M, Yamashita TS, Blumer JL. 1987. The clinical pharmacology of vancomycin in seriously ill preterm infants. Pediatr. Res. 22:360–363. 10.1203/00006450-198709000-00024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehrotra N, Tang L, Phelps SJ, Meibohm B. 2012. Evaluation of vancomycin dosing regimens in preterm and term neonates using Monte Carlo simulations. Pharmacotherapy 32:408–419. 10.1002/j.1875-9114.2012.01029.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel AD, Anand D, Lucas C, Thomson AH. 2012. Intermittent versus continuous infusion of vancomycin in neonates. Arch. Dis. Child. 97:e20. 10.1136/archdischild-2012-301728.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rybak MJ, Lomaetro B, Rotschafer JC, Moellering RC, Craig WA, Billeter M, Dalovisio JR, Levine DP. 2009. Vancomycin therapeutic guidelines: a summary of consensus recommendations from the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Clin. Infect. Dis. 49:325–327. 10.1086/600877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pawlotsky F, Thomas A, Kergueris MF, Debillon T, Roze JC. 1998. Constant rate of infusion of vancomycin in premature neonates: a new dosage schedule. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 46:163–167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Plan O, Cambonie G, Barbotte E, Meyer P, Devine C, Milesi C, Pidoux O, Badr M, Picaud JC. 2008. Continuous-infusion vancomycin therapy for preterm neonates with suspected or documented gram-positive infections: a new dosage schedule. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 93:F418–F421. 10.1136/adc.2007.128280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao W, Lopez E, Biran V, Durrmeyer X, Fakhoury M, Jacqz-Aigrain E. 2013. Vancomycin continuous infusion in neonates: dosing optimisation and therapeutic drug monitoring. Arch. Dis. Child. 98:449–453. 10.1136/archdischild-2012-302765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cataldo MA, Tacconelli E, Grilli E, Pea F, Petrosillo N. 2012. Continuous versus intermittent infusion of vancomycin for the treatment of gram-positive infections: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67:17–24. 10.1093/jac/dkr442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ingram PR, Lye DC, Tambyah PA, Goh WP, Tam VH, Fisher DA. 2008. Risk factors for nephrotoxicity associated with continuous vancomycin infusion in outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62:168–171. 10.1093/jac/dkn080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.James JK, Palmer SM, Levine DP, Rybak MJ. 1996. Comparison of conventional dosing versus continuous-infusion vancomycin therapy for patients with suspected or documented gram-positive infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:696–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pea F, Viale P. 2008. Should the currently recommended twice-daily dosing still be considered the most appropriate regimen for treating MRSA ventilator-associated pneumonia with vancomycin? Clin. Pharmacokinet. 47:147–152. 10.2165/00003088-200847030-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rello J, Sole-Violan J, Sa-Borges M, Garnacho-Montero J, Muñoz E, Sirgo G, Olona M, Diaz E. 2005. Pneumonia caused by oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus treated with glycopeptides. Crit. Care Med. 33:1983–1987. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000178180.61305.1D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roberts JA, Taccone FS, Udy AA, Vincent JL, Jacobs F, Lipman J. 2011. Vancomycin dosing in critically ill patients: robust methods for improved continuous-infusion regimens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:2704–2709. 10.1128/AAC.01708-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wysocki M, Delatour F, Faurisson F, Rauss A, Pean Y, Misset B, Thomas F, Timsit JF, Similowski T, Mentec H, Mier L, Dreyfuss D. 2001. Continuous versus intermittent infusion of vancomycin in severe Staphylococcal infections: prospective multicenter randomized study. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2460–2467. 10.1128/AAC.45.9.2460-2467.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elligsen M, Walker SAN, Simor A, Daneman N. 2012. Prospective audit and feedback of antimicrobial stewardship in critical care: program implementation, experience, and challenges. Can. J. Hosp. Pharm. 65:31–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Hoog M, Mouton JW, van den Anker JN. 2004. Vancomycin pharmacokinetics and administration regimens in neonates. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 43:417–440. 10.2165/00003088-200443070-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DiPiro JT, Blouin RA, Pruemer JM. 1988. Concepts in clinical pharmacokinetics—a self-instructional course. American Society of Hospital Pharmacists, Bethesda, MD [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lambert RJ, Lambert R. 2006. Population distributions of minimum inhibitory concentration—increasing accuracy and utility. J. Appl. Microbiol. 100:999–1010. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.02842.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simor AE, Louie L, Watt C, Gravel D, Mulvey MR, Campbell J, McGeer A, Bryce E, Loeb M, Matlow A. 2010. Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:2265–2268. 10.1128/AAC.01717-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nichol KA, Adam HJ, Roscoe DL, Golding GR, Lagace-Wiens PR, Hoban DJ, Zhanel GG, Canadian Antimicrobial Resistance Alliance 2013. Changing epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Canada. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 68(Suppl 1):i47–i55. 10.1093/jac/dkt026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sader HS, Flamm RK, Farrell DJ, Jones RN. 2012. Activity analyses of staphylococcal isolates from pediatric, adult, and elderly patients: AWARE Ceftaroline Surveillance Program. Clin. Infect. Dis. 55(Suppl 3):S181–S186. 10.1093/cid/cis560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Celikbilek N, Ozdem B, Gurelik FC, Guvenman S, Guner HR, Acikgoz ZC. 2011. In vitro susceptibility of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates to vancomycin, teicoplanin, linezolid and daptomycin. Mikrobiyoloji Bulteni 45:512–518 (In Turkish) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pitz AM, Yu F, Hermsen ED, Rupp ME, Fey PD, Olsen KM. 2011. Vancomycin susceptibility trends and prevalence of heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus in clinical methicillin-resistant S. aureus isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:269–274. 10.1128/JCM.00914-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mendes RE, Sader HS, Jones RN. 2010. Activity of telavancin and comparator antimicrobial agents tested against Staphylococcus spp. isolated from hospitalised patients in Europe (2007–2008). Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 36:374–379. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gales AC, Sader HS, Ribeiro J, Zoccoli C, Barth A, Pignatari AC. 2009. Antimicrobial susceptibility of gram-positive bacteria isolated in Brazilian hospitals participating in the SENTRY Program (2005–2008). Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 13:90–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sader HS, Fey PD, Limaye AP, Madinger N, Pankey G, Rahal J, Rybak MJ, Snydman DR, Steed LL, Waites K, Jones RN. 2009. Evaluation of vancomycin and daptomycin potency trends (MIC creep) against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates collected in nine U.S. medical centers from 2002 to 2006. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:4127–4132. 10.1128/AAC.00616-09 (Author Correction, 54:1383, 2010, ) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones RN, Sader HS, Flamm RK. 2013. Update of dalbavancin spectrum and potency in the USA: report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (2011). 2013. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 75:304–307. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.11.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Biedenbach DJ, Bell JM, Sader HS, Fritsche TR, Jones RN, Turnidge JD. 2007. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Gram-positive bacterial isolates from the Asia-Pacific region and an in vitro evaluation of the bactericidal activity of daptomycin, vancomycin, and teicoplanin: a SENTRY Program Report (2003–2004). Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 30:143–149. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Balode A, Punda-Polic V, Dowzicky MJ. 2013. Antimicrobial susceptibility of gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria collected from countries in Eastern Europe: results from the Tigecycline Evaluation and Surveillance Trial (T.E.S.T.) 2004–2010. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 41:527–535. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2013.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Asbury WH, Darsey EH, Rose WB, Murphy JE, Buffington DE, Capers CC. 1993. Vancomycin pharmacokinetics in neonates and infants: a retrospective evaluation. Ann. Pharmacother. 27:490–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anderson BJ, Allegaert K, van den Anker JN, Cossey V, Holford NH. 2007. Vancomycin pharmacokinetics in preterm neonates and the prediction of adult clearance. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 63:75–84. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02725.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alcorn J, McNamara PJ. 2003. Pharmacokinetics in the newborn. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 55:667–686. 10.1016/S0169-409X(03)00030-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bartelink IH, Rademaker CM, Schobben AF, van den Anker JN. 2006. Guidelines on paediatric dosing on the basis of developmental physiology and pharmacokinetic considerations. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 45:1077–1097. 10.2165/00003088-200645110-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]