Abstract

Due to their lack of toxicity to mammalian cells and good serum stability, proline-rich antimicrobial peptides (PR-AMPs) have been proposed as promising candidates for the treatment of infections caused by antimicrobial-resistant bacterial pathogens. It has been hypothesized that these peptides act on multiple targets within bacterial cells, and therefore the likelihood of the emergence of resistance was considered to be low. Here, we show that spontaneous Escherichia coli mutants resistant to pyrrhocoricin arise at a frequency of approximately 6 × 10−7. Multiple independently derived mutants all contained a deletion in a nonessential gene that encodes the putative peptide uptake permease SbmA. Sensitivity could be restored to the mutants by complementation with an intact copy of the sbmA gene. These findings question the viability of the development of insect PR-AMPs as antimicrobials.

INTRODUCTION

Growing bacterial resistance to antibiotics poses a considerable threat to public health. Despite major developments in antibiotic chemotherapy, the incidence of acute infections with multidrug-resistant bacteria is increasing at an alarming rate (1–3). Antimicrobial agents with novel modes of action are required, preferably ones acting on targets that have not yet encountered selective pressure in the clinical setting. Ideally, such a target would be essential for growth and survival of the bacteria in vivo and sufficiently different from its homologs in the human host to provide selectivity. Proline-rich antimicrobial peptides (PR-AMPs) isolated from mammals and insects represent a promising class of drug candidates exhibiting those features (4–8). These peptides are important components of the innate immune defense against Gram-negative bacterial infections and, as such, they show very low toxicity toward mammalian cells and good serum stability (4, 9).

Although PR-AMPs from different sources show significant diversity at the level of amino acid sequence, they share several common features important for their function and that are thought to have been acquired through convergent evolution: (i) a high content of proline residues (25 to 50%), (ii) a net positive charge due to the presence of arginine residues, (iii) a broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity predominantly against Gram-negative bacteria, and (iv) a marked loss of activity in all d-enantiomers (4).

Among the most studied insect-derived PR-AMPs are apidaecin, drosocin, and pyrrhocoricin, isolated from honeybees (Apis mellifera) (10), Drosophila melanogaster (11), and the European sap sucking bug Pyrrhocoris apterus (12), respectively. These peptides and/or their derivatives are active in the submicromolar to micromolar concentration range and show very similar selectivity against Gram-negative bacteria, including Enterobacteriaceae, Agrobacterium tumefaciens, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and against a few Gram-positive species, including Micrococcus luteus and Bacillus megaterium (5, 8, 10, 12, 13). Pyrrhocoricin and drosocin contain a glycosylated threonine, but glycosylation is not required for full biological activity (5).

In contrast to other types of antimicrobial peptides that act by disrupting bacterial membranes, PR-AMPs isolated from mammals and insects have a remarkable ability to penetrate the cell envelope without apparent membrane damage and kill the bacteria by deactivating essential intracellular microbial targets (4). One of the internal targets of drosocin, pyrrhocoricin, apidaecin, and mammalian PR-AMP Bac7 is the molecular chaperone DnaK (14–16). However, there is experimental evidence that DnaK is not the primary target. First, it was established that ΔdnaK mutants are viable and still susceptible to PR-AMPs Bac7 (4) and Api88 (apidaecin derivative) (17). Second, pyrrhocoricin and apidaecin bind nonspecifically to the chaperonin GroEL (18, 19), which may be an additional target. Thus, the primary bacterial target of insect PR-AMPs is yet to be identified, although it is also possible that the killing mechanism involves actions on multiple targets.

Due to their lack of toxicity to mammalian cells and good serum stability, PR-AMPs have been proposed as promising drug candidates in treating emerging/reemerging antimicrobial-resistant bacterial pathogens. Sequences of pyrrhocoricin, apidaecin, and oncocin (a peptide from the milkweed bug [Oncopeltus fasciatus], the amino acid sequence of which is 70% identical to pyrrhocoricin) have been optimized for clinical applications, producing peptides with increased serum stability and in vivo activity (17, 20, 21). These efforts continue under the assumption that, since insect PR-AMPs may have multiple targets within bacterial cells, the likelihood for emergence of resistance is low compared to that for current antibiotics with single molecular targets. In this paper, we show for the first time that spontaneous Escherichia coli mutants resistant to pyrrhocoricin arise at a relatively high frequency (6 × 10−7) through disruption of the nonessential gene sbmA, which encodes a putative peptide uptake permease. This finding has an important impact on the field, as it raises questions about the viability of developing insect PR-AMPs as drugs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, reagents, media, and growth conditions.

E. coli K-12 C600 (F− thi-1 thr-1 leuB6 lacY1 tonA21 supE44 λ−) was used throughout (22). Cultures were grown at 37°C either in quarter-strength cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton II broth (MHIIB; BD) with shaking at 180 rpm (unless stated otherwise) or on 1.5% agar plates prepared in quarter-strength MHIIB. For maintenance of the plasmid, the medium was supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml). The T7 expression vector pET-22b(+) (PT7, Ampr, oripBR322, lacI, C-terminal 6×His) and KOD Hot Start DNA polymerase were from Novagen. Pyrrhocoricin (H2N-VDKGSYLPRPTPPRPIYNRN-CONH2) was synthesized by GenScript.

Determination of the MIC of pyrrhocoricin.

Bacteria were grown overnight on agar plates, after which one colony was inoculated into liquid medium (7.5 ml) and the culture was grown to the mid-logarithmic phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of 0.4 to 0.6). Cell concentrations (CFU/ml) were calculated based on the observation that an OD600 of 1.0 corresponds to approximately 3.8 × 108 CFU/ml. The mid-logarithmic phase culture was diluted in the same medium to 105 CFU/ml. MICs were determined using a standard 2-fold serial broth dilution method (23) in flat-bottomed 96-well polystyrene plates (BD Falcon). Each well contained 90 μl of 105 CFU/ml of bacteria and 10 μl of 2-fold serial dilutions of pyrrhocoricin prepared in sterile water. The controls on each plate were (i) bacteria without the peptide and (ii) medium alone. The plates were incubated overnight without shaking. Cell growth was monitored by measuring OD600 of the culture using a Tecan Infinite M200 microplate reader. The MIC was determined as the lowest concentration of pyrrhocoricin that inhibited detectable bacterial growth. The MIC values were determined from two technical repeats of three biological replicates.

LL-37 resistance.

MICs of the human antimicrobial peptide LL-37 (24) were determined as for pyrrhocoricin with the following minor modification: polypropylene plates (Greiner) were used to avoid binding of cationic LL-37 to the plate, and each well contained 87.5 μl of 105 CFU/ml of bacteria and 12.5 μl of 2-fold serial dilutions of LL-37.

Isolation of E. coli mutants resistant to pyrrhocoricin.

It has been previously reported that mutants of uropathogenic E. coli CFT073 resistant to pyrrhocoricin were identified after several passages in the presence of sublethal doses of the peptide (25), although the mechanism of resistance was not investigated. In this study, we used the pyrrhocoricin-sensitive laboratory strain E. coli K-12, substrain C600 (MIC of 5 μM). Four independent mutants (Mut1, Mut2, Mut3, and Mut4) were obtained by iterative selection for pyrrhocoricin resistance in liquid culture. Mut1 was isolated following six serial passages in liquid broth supplemented with the fixed sublethal concentration of the peptide (1.25 μM) (the sublethal concentration was chosen as one quarter of the MIC of wild-type E. coli). On day 1, overnight culture of wild-type bacteria grown in quarter-strength MHIIB was diluted to 4 × 108 CFU/ml in MHIIB supplemented with the peptide and maintained by 20-fold serial dilution in 1 ml of the same medium every 20 h.

Mutants with higher resistance to pyrrhocoricin (Mut2, Mut3, and Mut4) were isolated following serial passage of E. coli in increasing concentrations of this peptide. Mut2 was generated by selection for progressive resistance to 1.3, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 40, 80, 100, 120, 140, 160, and then 180 μM pyrrhocoricin over the period of 13 days. Mut3 was obtained by selection against 1.3, 3.8, 11.3, 33.7, 101.3, 125, 150, and 175 μM pyrrhocoricin over 14 days. Mut4 was obtained by selection against 1.3, 5, 20, 80, 125, 150, and 175 μM pyrrhocoricin over 15 days. Control serial passages in the absence of the peptide were also included, and the resulting cultures showed no change in MIC.

The approximate frequency at which mutants capable of growth at 10× MIC of pyrrhocoricin arise was determined in a single step from plates inoculated with 109, 108, and 107 CFU, with the peptide included in the solid medium. Two biological repeats were performed (each in duplicate); the frequency was calculated as the mean number of colonies appearing on a plate divided by the number of CFU inoculated.

High-throughput genome sequencing and analysis.

Genomic DNA was extracted from wild-type E. coli K-12 C600 (MIC of 5 μM) and Mut2 (MIC > 640 μM) using a GenElute bacterial genomic DNA kit (Sigma-Aldrich). High-throughput sequencing was performed on an Illumina GAIIx (Illumina, USA) by the Micromon High-Throughput Sequencing Facility (Monash University, Australia) using a multiplexed 150-bp paired-end protocol. Raw sequence data from both samples was aligned independently to the reference genome sequence of E. coli K-12 substrain W3110 (NCBI accession number NC_007779.1) (26) by using CLC genomics Workbench v. 5.5 (CLCbio) with default settings. Potential regions of difference were confirmed by PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing (see below). All nucleotide numbering here refers to locations on the reference E. coli K-12 W3110 genome sequence.

PCR and Sanger sequencing.

All oligonucleotide primers used in PCR, DNA sequencing, and cloning experiments are listed in Table 1. The 1,978-bp region containing the 1,917-bp dnaK gene was amplified from genomic DNA of wild-type E. coli C600, Mut1, Mut2, Mut3, and Mut4 (three colonies from each) using primers dnaK-F and dnaK-R and KOD Hot Start DNA polymerase, purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen), and sequenced by the Micromon High-Throughput Sequencing Facility using the conventional Sanger method. The sequences were aligned using the ClustalW2 program (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2) (27).

TABLE 1.

Sequences of the oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence/position | Used in: |

|---|---|---|

| dnaK-F | 12,136GACCGAATTCATAGTGGAGACG12,157a | PCR amplification of the dnaK gene |

| dnaK-R | 14,113CCCGTGTCAGTATAATTACCC14,093 | PCR amplification of the dnaK gene |

| sbmA-del-F | 395,804CGGTCATGCGGTTAATACACAG395,825 | PCR amplification of the sbmA gene |

| sbmA-del-R | 397,168CCTGACTACTACACCCCGCTAA397,147 | PCR amplification of the sbmA gene |

| DB-F | 390,900GCGTTGACCGAATCTACTGGGT390,921 | Mapping of the deletion boundaries in E. coli C600 mutants |

| DB-R | 397,995CACCTTTCTCTAACTGACGGCG397,974 | Mapping of the deletion boundaries in E. coli C600 mutants |

| DB-R1 | 397,410GGTCAATCTCTTGCCAGGCGAT397,389 | Mapping of the deletion boundaries in E. coli C600 mutants |

| sbmA-pET22-F | GCATCACATATGTTTAAGTCTTTTTTCCAb | Cloning of sbmA in E. coli C600 mutants Mut2 to Mut4 |

| sbmA-pET22-R | ACATGCGAGCTCGCTCAAGGTATGGGGc | Cloning of sbmA in E. coli C600 mutants Mut2 to Mut4 |

| T7 forward | CCCGCGAAATTAATACGACTCACTA | Sequencing of sbmA-complemented and resistant mutants |

| T7 reverse | GCTAGTTATTGCTCAGCGG | Sequencing of sbmA-complemented and resistant mutants |

Numbers indicate nucleotide positions with reference to the published genome of E. coli K-12 substrain W3110 (NCBI accession number NC_007779.1).

The NdeI restriction site is underlined.

The SacI restriction site is underlined.

The deletion of the sbmA gene in the genomic DNA of Mut1 to Mut4 was verified by PCR amplification of a 1.4-kb fragment using oligonucleotide primers sbmA-del-F and sbmA-del-R flanking the sbmA gene region, followed by analysis of the PCR products on a 1% agarose gel. To verify the deletion boundary of genome-sequenced Mut2 and to establish the deletion boundaries in the other mutants (Mut1, Mut3, and Mut4), their genomic DNA was PCR amplified using oligonucleotide primers DB-F, DB-R, and DB-R1 that bind upstream and downstream of the deleted region, and the PCR products were sequenced.

Cloning and overexpression of sbmA in Mut2, Mut3, and Mut4.

The gene encoding SbmA of E. coli K-12 C600 was amplified from genomic DNA using KOD Hot Start DNA polymerase and oligonucleotide primers sbmA-pET22-F/R (Table 1), incorporating unique NdeI and SacI restriction sites to aid cloning into the high-copy expression vector pET-22b(+), which provides a C-terminal His6 tag on the expressed protein. The resulting plasmid was confirmed by sequencing and transformed into Mut2, Mut3, and Mut4 cells, which were then grown in quarter-strength MHIIB supplemented with 100 μg/ml ampicillin to an OD600 of 0.6 to 0.8, at which point SbmA expression was induced by adding 0.5 mM isopropyl-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (IPTG), and growth continued for 3 h at 37°C. A cell aliquot was saved for the analysis of protein expression by SDS-PAGE, and the cells were then used for determination of MIC as described above, with the only difference being that the liquid medium was supplemented with 0.5 mM IPTG. In control samples, the MIC was determined for the mutants transformed with the empty pET-22b(+) vector. To prepare samples for SDS-PAGE analysis on a 15% gel, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C, resuspended in buffer containing 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and lysed using a Branson sonicator. The protein concentration was determined using the Bradford assay (28).

Selection for resistance to pyrrhocoricin in sbmA-complemented Mut2 and Mut3.

Selection for resistance to pyrrhocoricin in sbmA-complemented Mut2 and Mut3 was carried out in three biologically independent experiments. In the first experiment, sbmA expression was induced in Mut2 and Mut3 with 0.5 mM IPTG for 3 h in liquid culture containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin as described above, after which 7.5 × 106 cells were plated onto 1 ml of agar supplemented with 0.5 mM IPTG, 100 μg/ml ampicillin, and 50, 100, or 150 μM pyrrhocoricin and incubated at 37°C. After 16 h, two resistant colonies of complemented Mut2 (here named I-Mut2-1 and I-Mut2-2, where prefix I- refers to the first independent experiment) and one resistant colony of complemented Mut3 (named I-Mut3-1) were picked from the plate with 150 μM pyrrhocoricin and streaked onto a fresh plate for single clones; the agar contained the same concentrations of IPTG, ampicillin, and pyrrhocoricin. In the second biologically independent experiment, the same protocol was repeated, but this time the plates did not contain ampicillin. Under these conditions, resistant clones were found after overnight incubation for Mut3 but not for Mut2. Two resistant colonies of complemented Mut3 (named II-Mut3-2 and II-Mut3-3, where prefix II refers to the second independent experiment) were picked from the plate with 150 μM pyrrhocoricin and streaked onto a fresh plate (with the same concentrations of IPTG and pyrrhocoricin) for single clones. The MIC of II-Mut3-2 and II-Mut3-3 was determined as described above. In the third biologically independent experiment, the same protocol was repeated, but this time neither the liquid medium nor plates contained ampicillin. Under these conditions, resistant colonies were found after overnight incubation for Mut3 but not for Mut2. One resistant colony of complemented Mut3 (named III-Mut3-4, where prefix III refers to the third independent experiment) was picked from the plate with 150 μM pyrrhocoricin and streaked onto a fresh plate for single clones. The MICs of I-Mut2-1, I-Mut2-2, I-Mut3-1, II-Mut3-2, II-Mut3-3, and III-Mut3-4 were determined as described earlier. To analyze the stability of the cloned sbmA gene in the pET-22b(+) plasmid through its amplification in E. coli cells, the plasmid was extracted from all of the above-described mutants and from the control grown in the absence of pyrrhocoricin using the Qiagen plasmid minikit and sequenced using T7 forward and T7 reverse primers.

RESULTS

Isolation of E. coli C600 mutants with decreased susceptibility to pyrrhocoricin.

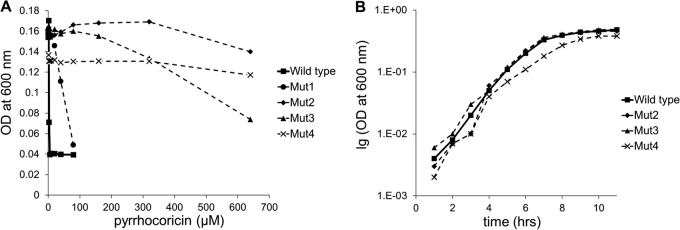

Four independent mutants of E. coli K-12 substrain C600 (Mut1, Mut2, Mut3, and Mut4) with increased resistance to pyrrhocoricin were identified following in vitro selection by serial passage in liquid culture. Mut1 with an MIC of >80 μM was isolated following six serial passages in the presence of a sublethal concentration of the peptide (Fig. 1A). Such a model, which uses low inocula of bacteria and passages in the presence of sublethal doses of an antimicrobial agent, closely simulates the in vivo situation. Mutants with significantly higher resistance to pyrrhocoricin, as indicated by a more-than-100-fold increase in the MIC from its wild-type value (Mut2, Mut3, and Mut4, MIC > 640 μM) (Fig. 1A), were isolated following serial passages over 13 to 15 days in increasing (up to 180 μM) concentrations of the peptide. Only one out of the three mutants resistant to pyrrhocoricin (Mut4) showed a lower growth rate than the other mutants and the parental strain (Fig. 1B); the observed growth defect is therefore unlikely to be linked to resistance. As DnaK has been previously suggested to be the likely target of pyrrhocoricin, we have determined the sequence of the dnaK gene in wild-type E. coli and all the mutants and found it to be identical to the parent strain. Thus, we have eliminated the possibility that a mutation in dnaK is responsible for the decreased susceptibility.

FIG 1.

(A) Sensitivity of wild-type E. coli C600 and Mut1 to Mut4 to pyrrhocoricin. The MIC value was 5 μM for the wild-type bacteria, higher than 80 μM for Mut1, and higher than 640 μM for Mut2, Mut3, and Mut4. (B) Growth curve for wild-type E. coli C600 and highly resistant mutants Mut2 to Mut4.

Analysis of the genome sequence to identify genetic determinants conferring peptide resistance.

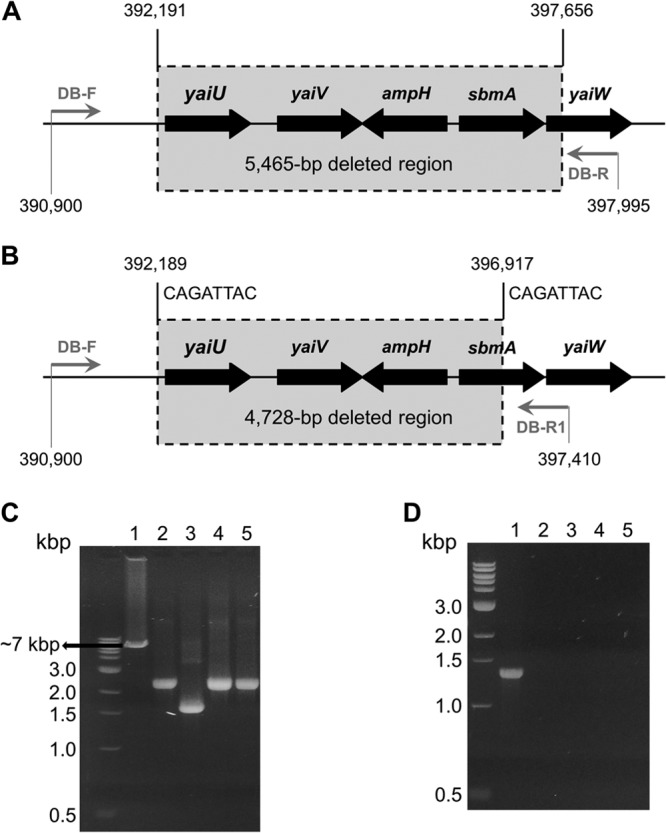

In order to elucidate genetic determinants that confer resistance to pyrrhocoricin, we determined and compared the entire genome sequences of the parent strain and one of its resistant mutants, Mut2. This analysis revealed only one difference: a chromosomal deletion of a 5,465-bp region in Mut2, removing (fully or partially) the following five genes: yaiU, encoding a hypothetical outer membrane protein (26); yaiV and yaiW, encoding putative DNA-binding transcriptional regulators; ampH, encoding a bifunctional dd-endopeptidase/dd-carboxypeptidase (29, 30); and sbmA, encoding a dimeric transporter (31–33) (Fig. 2A). The deletion was confirmed by sequencing the products of PCR amplification of genomic DNA of wild-type E. coli and Mut2 by using primers flanking the deletion boundary (Fig. 2A, Table 1).

FIG 2.

Analysis of the deletion of the region around the sbmA gene in pyrrhocoricin-resistant E. coli C600 mutants. (A) Genomic structure of the deleted region in Mut2. Nucleotide positions are indicated with reference to the published E. coli K-12 W3110 genome. Gray horizontal arrows show the positions of the forward and reverse PCR primers (Table 1). (B) The deletion boundaries in Mut1, Mut3, and Mut4 are close to but different from those in Mut2. Eight-nucleotide direct repeats that likely mediate the site-specific recombination leading to deletion are shown on top. (C, D) Confirmation of deletion of the sbmA-containing region in Mut1 to Mut4 by PCR. (C) The products of PCR amplification of the sbmA gene from the wild type (lane 1) and mutant E. coli C600 strains (lanes 2 to 5, Mut1, Mut2, Mut3, and Mut4, respectively), using flanking primers sbmA-del-F and sbmA-del-R (Table 1). Expected size of the PCR product was 1.4 kb. (D) PCR-amplified DB-F/DB-R fragments (Table 1). Lane 1 (parental strain), anticipated size (7,096 bp) is consistent with the mobility on the gel; lanes 2 to 5 (Mut1 to Mut4, respectively), size estimation from the gel, 2.4 kb for Mut1, Mut3, and Mut4 and 1.6 kb for Mut2. The PCR products for all mutants were sequenced and were shown to be 2,368 bp for Mut1, Mut3, and Mut4 (due to a 4,728-bp deletion) and 1,631 bp for Mut2 (due to a 5,465-bp deletion).

Since SbmA has been previously implicated in internalization of other antimicrobial proline-rich peptides by Gram-negative bacteria, such as, for example, Bac7 by E. coli (34) and PR-39 by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (35), we wished to establish the role of the deletion of sbmA in the observed resistance to pyrrhocoricin. First, we confirmed by PCR that the genomic DNA of the remaining three resistant mutants, Mut1, Mut3, and Mut4, also had a deletion in the sbmA region (Fig. 2C). We then established by PCR that the deletion in these mutants is approximately 700 bp shorter than that in Mut2 (Fig. 2D) and mapped the deletion boundaries by sequencing the amplified fragments containing the region of interest. All three mutants had the same 4,728-bp chromosomal deletion that had a 5′-breakpoint only two base pairs from that in Mut2 (Fig. 2B). This deletion eliminated (fully or partially) the yaiU, yaiV, ampH, and sbmA genes. The yaiW gene remained intact; however, we note that yaiW and the upstream located sbmA form an operon (36), and deletion of their common promoter would abolish transcription of yaiW.

The observation that three of the four resistant mutants had an identical deletion prompted us to search the nucleotide sequence at the deletion sites for potential highly homologous motifs that could mediate the excision by a specific mechanism. This analysis identified two eight-nucleotide direct repeats that flank the deletion sites in each of these three resistant mutants (Mut1, Mut3, and Mut4) (Fig. 2B), strongly suggestive of a site-specific deletion event mediated via recombination points. However, a similar deletion mechanism could not be detected for Mut2.

Determination of the frequency of spontaneous deletions resulting in pyrrhocoricin resistance, using a single-step selection, yielded an average value of 6 × 10−7, which falls within the range found for spontaneous point mutations in E. coli (37, 38).

Genetic complementation of deletion mutants with sbmA restored susceptibility to pyrrhocoricin.

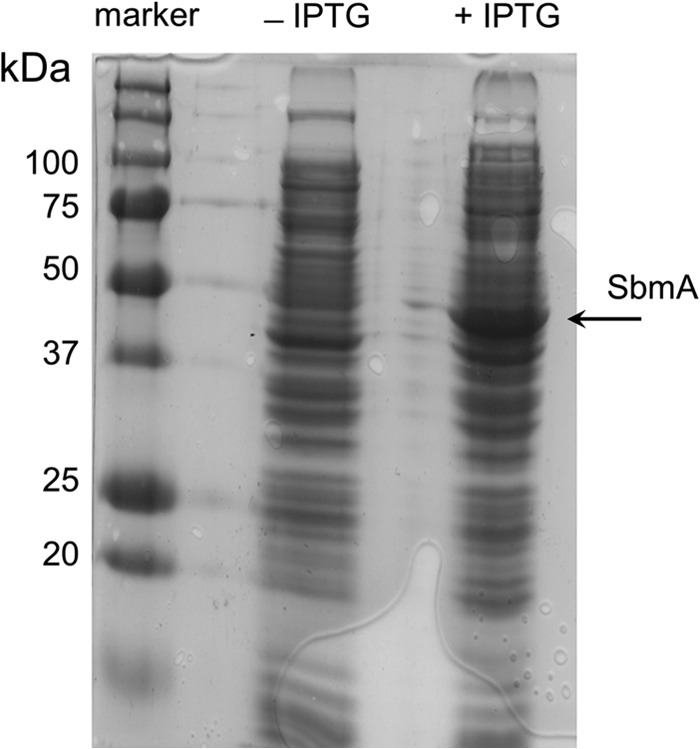

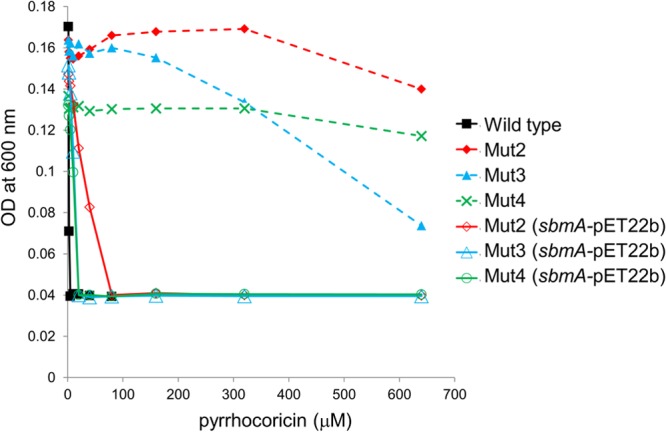

The three mutants that showed high-level resistance (>100 times the wild-type MIC) to pyrrhocoricin, Mut2 to Mut4, were genetically complemented with an IPTG-inducible high-copy-number expression plasmid that encoded SbmA or with the empty control plasmid. Protein expression was induced in the complemented strains for 3 h (Fig. 3), after which each strain was used to measure the MIC of pyrrhocoricin in the presence of IPTG. These experiments showed that complementation with sbmA restored sensitivity to this peptide to the levels close to those of the wild-type strain (Fig. 4), indicating that resistance in the deletion mutants was largely due to inactivation of sbmA.

FIG 3.

Confirmation of expression of SbmA (46.5 kDa) from a multicopy plasmid pET-22b(+) in the complemented deletion mutant Mut2. Fifteen micrograms of total protein from the uninduced (−IPTG) or induced (+IPTG) samples was loaded per lane.

FIG 4.

Sensitivity to pyrrhocoricin of Mut2 to Mut4 genetically complemented with an IPTG-inducible high-copy-number plasmid expressing SbmA (solid line). Sensitivity of noncomplemented mutants is shown in a dashed line for comparison. Expression of the transporter largely restored sensitivity to pyrrhocoricin.

Passage of sbmA-complemented Mut2 and Mut3 in the presence of pyrrhocoricin strongly selected for sbmA gene disruptions.

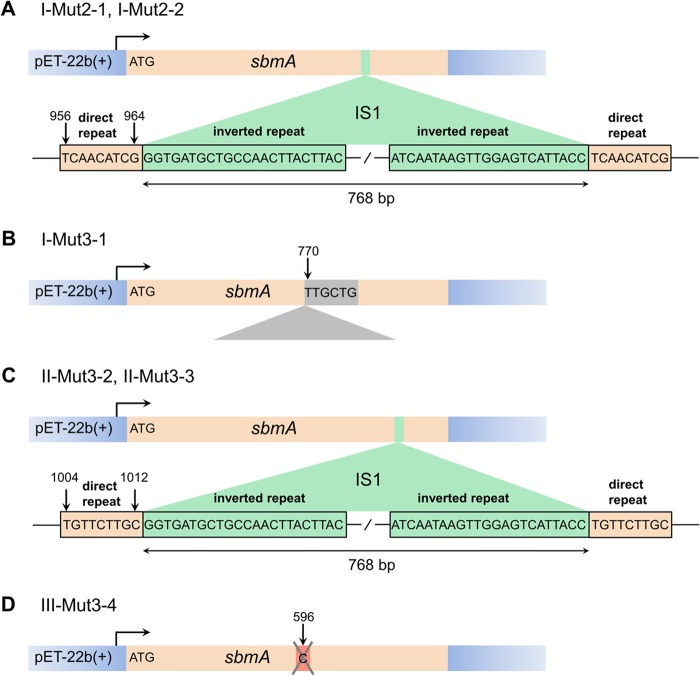

We wanted to isolate spontaneously resistant derivatives of Mut2 and Mut3 complemented with multicopy sbmA in an attempt to identify mutations in the primary intracellular target of pyrrhocoricin, while ensuring SbmA-mediated peptide internalization. The growth of resistant clones identified by the passage of sbmA-complemented Mut2 and Mut3 in the presence of pyrrhocoricin was nearly indistinguishable from the growth of noncomplemented Mut2 and Mut3 (MICs of I-Mut2-1 and I-Mut2-2 were 500 to 600 μM; MIC of I-Mut3-1 was ≈640 μM; and MICs of II-Mut3-2, II-Mut3-3, and III-Mut3-4 were >640 μM), suggesting that the plasmid in the resistant clones might have undergone rearrangements that disrupted the sbmA gene or T7 promoter. Plasmid DNA isolated from these clones was sequenced using T7 forward and T7 reverse primers to identify the nature of possible rearrangements. This analysis showed that the sbmA gene copy in the sbmA-pET-22b(+) plasmid present in resistant clones I-Mut2-1 and I-Mut2-2 was disrupted by an ∼0.8-kb insertion approximately 950 bp downstream of the start codon (Fig. 5A). A homology search using BLASTN (blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) (39) identified the sequence as a type 1 E. coli insertion sequence (IS1), a 768-bp element with a 23-bp inverted repeat on either end (40). Insertion of this sequence generated 9-bp direct repeats of the target sequence on either side (Fig. 5A), in line with the previous reports on the mechanism of IS1 insertion. Similarly, the sbmA coding region in clones II-Mut3-2 and II-Mut3-3 was disrupted by the IS1 inserted at a different site, between positions 1004 and 1012 (Fig. 5C). In clone I-Mut3-1, the sbmA coding region contained an insertion of a sequence of unknown origin with partial homology to 16S rRNA (Fig. 5B). Finally, a single-base deletion of cytosine at position 596 was identified in the sbmA region of the recombinant plasmid in clone III-Mut3-4 (Fig. 5D). Thus, induction of heterologous expression of SbmA in the presence of pyrrhocoricin invariably selected for mutants with the sbmA gene disrupted by insertion or deletion, even in multicopy plasmids. In contrast, the sbmA region of the plasmid isolated from the (−pyrrhocorin +IPTG) sbmA-complemented Mut2 control remained intact, suggesting that, in the absence of the peptide, the product of the sbmA gene expressed from a multicopy plasmid is not toxic to the cells.

FIG 5.

Mutations in the sbmA gene sustained by the recombinant sbmA-pET-22b(+) plasmid when gene expression was induced in the presence of pyrrhocoricin. (A) Disruption of the sbmA coding region by the 768-bp transposon insertion (E. coli insertion sequence 1 [IS1]) between positions 956 and 964 in clones I-Mut2-1 and IMut2-2. The sequences of 9-bp direct repeats of the target sequence, originating from the insertion, and the 23-bp inverted repeats at the IS1 termini are shown. (B) sbmA gene disruption by a sequence of unknown origin inserted in the coding sequence before nucleotide 770 in clone I-Mut3-1. (C) The IS1 transposon inserted between positions 1004 and 1012 of the sbmA coding region in clones II-Mut3-2 and II-Mut3-3. (D) A single-base deletion in sbmA identified in clone III-Mut3-4.

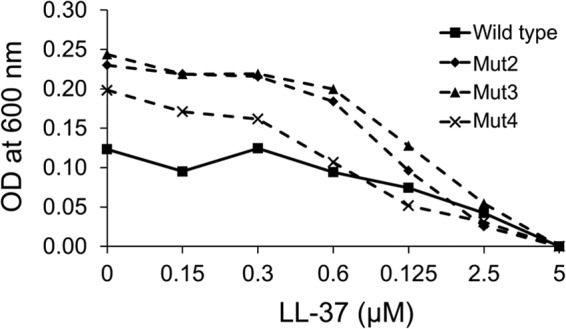

Mutants with decreased susceptibility to pyrrhocoricin do not show cross-resistance to LL-37.

Mut2 to Mut4 displayed the same sensitivity to the unrelated cationic, membrane-active antimicrobial peptide LL-37 from the cathelicidin family as the parental strain (MIC of 5 μM) (Fig. 6). This observation suggested that (i) spontaneous deletions of the sbmA region resulting in pyrrhocoricin resistance are not associated with any significant changes in the overall permeability or charge of the cell wall and (ii) SbmA shows selectivity toward pyrrhocoricin and pyrrhocoricin-like peptides.

FIG 6.

Sensitivity to LL-37 of wild-type E. coli C600 and Mut2 to Mut4. The MIC value was 5 μM for both the wild-type bacteria and mutants.

DISCUSSION

It has long been proposed that insect-derived PR-AMPs are promising lead compounds for drug design since they have the advantage of low toxicity, high selectivity, and good serum stability (17, 20, 21). It has also been hypothesized that these peptides act on multiple targets within bacterial cells, and therefore the likelihood of the emergence of spontaneous resistance would be correspondingly low. This is the first report that challenges this view by showing that E. coli can easily acquire resistance to pyrrhocoricin through disruption of the nonessential gene that encodes SbmA, a putative peptide uptake permease.

We have established that spontaneous E. coli mutants resistant to pyrrhocoricin arise at a relatively high frequency (6 × 10−7), close to that of spontaneous point mutations. The possibility that a mutation in the dnaK gene encoding a proposed intracellular target is responsible for the decreased susceptibility was ruled out by sequencing the dnaK gene in resistant mutants isolated in several biologically independent experiments. Full genome sequencing of one representative resistant mutant identified only one difference with the parental strain, a chromosomal deletion affecting a cluster of five genes, including sbmA. Further analysis identified a similar deletion in the sbmA region, albeit with small variations in the deletion boundaries, in every resistant mutant. Inspection of the full genome sequences of the previously characterized pyrrhocoricin-resistant and pyrrhocoricin-sensitive Gram-negative strains showed that sbmA or its homolog bacA is present in all susceptible strains but absent from resistant ones (Table 2). This analysis was consistent with our observation that spontaneous chromosomal deletion of sbmA in E. coli, which is naturally sensitive to pyrrhocoricin, results in resistance. It also suggested that SbmA plays an important role in the mechanism of action of pyrrhocoricin. Indeed, we have proven that resistance in the deletion mutants was due largely to inactivation of sbmA rather than to any of the other four genes in the deleted region, by showing that expression of SbmA from an endogenous plasmid restored sensitivity to pyrrhocoricin to levels close to those of the wild type. This conclusion was further supported by our observation that passage of the resistant deletion mutants in the presence of pyrrhocoricin after complementation with a plasmid expressing SbmA, which restores sensitivity, strongly selected for secondary resistant mutants in which the sbmA gene was disrupted by DNA insertions or deletions.

TABLE 2.

Correlation between susceptibility to pyrrhocoricin and the presence of the sbmA (bacA) gene in Gram-negative bacteria

| Gram-negative species | Sensitive to pyrrhocoricin? | sbmA (bacA) present? | SbmA/BacA Uniprot identifier | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Yes | Yes | sbma_ecoli | 5, 8, 12, 34, 36, 49 |

| Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium | Yes | Yes | h8m5q1_saltm | 8, 12, 37, 49, 50, 51 |

| Haemophilus influenzae | Yes | Yes | y1467_haein | 5, 8, 51 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Yes | Yes | r4yhq1_klepn | 5, 12 |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | Yes | Yes | q7cxd9_agrt5 | 5, 49, 50 |

| Enterobacter cloacae | Yes | Yes | g8lp73_entcl | 5, 12 |

| Helicobacter pylori | No | No | 5, 8, 12 | |

| Moraxella catarrhalis | No | No | 5, 8, 12 | |

| Serratia marcescens | No | No | 5, 8, 12 | |

| Alcaligenes faecalis | No | No | 5, 8, 12 | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | No | No | 5, 8, 12 | |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | No | No | 5, 8, 12 | |

| Haemophilus ducreyi | No | No | 5, 8, 12 | |

| Moraxella catarrhalis | No | No | 5, 8, 12 | |

| Burkholderia cepacia | No | No | 5, 8, 12 | |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | No | No | 5, 8, 12 | |

| Neisseria meningitidis | No | No | 5, 8, 12 | |

| Enterococcus faecalis | No | No | 5, 8, 12 | |

| Xanthomonas campestris | No | No | 5, 8, 12 | |

| Erwinia carotovora | No | No | 5, 8, 12 |

SbmA and BacA are homologous inner membrane proteins that make up the peptide uptake permease (PUP) family (41). SbmA is dimeric and shares homology with the transmembrane domain of ABC transporters; however, it lacks the nucleotide binding domain, and its function requires an electrochemical gradient across the inner membrane rather than ATP hydrolysis (32, 33). Although the sbmA gene is found in many bacteria, in particular in most Enterobacteriaceae, its product has been shown not to be essential under laboratory conditions (31, 35).

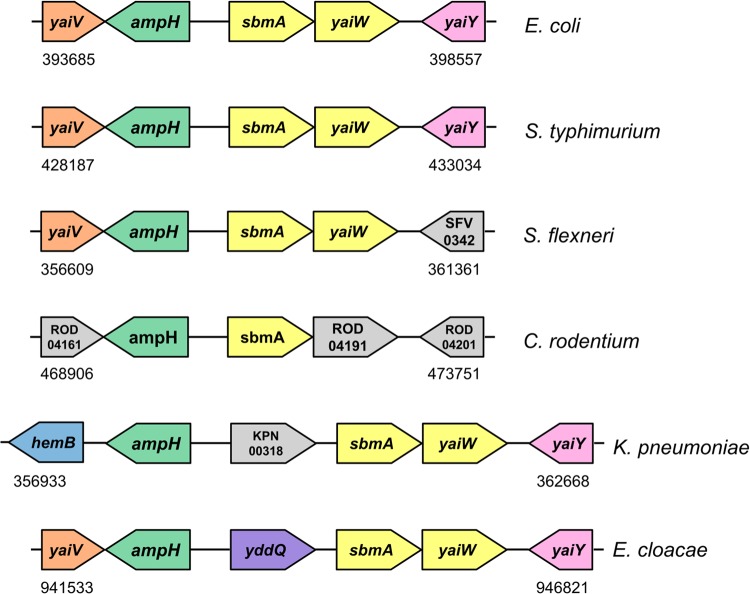

The physiological role of SbmA is not yet known, but BacA from Mycobacterium tuberculosis was recently revealed to be the sole importer of exogenous vitamin B12 and other corrinoids in vitro (42). We note that in the genomes of Gram-negative enteric bacteria adapted to grow in the mammalian intestine, the sbmA gene is adjacent to or proximal to ampH (Fig. 7). Conservation of proximity between two genes across different genomes may indicate a functional association. AmpH is a periplasmic peptidoglycan (PG) peptidase that belongs to the class C subdivision of low-molecular-mass penicillin-binding proteins (LMM PBPs) (30) and is thought to play a role in PG remodeling during cell division or in PG recycling. It is known that over 90% of the products generated during the PG turnover are captured by E. coli and reutilized rather than being lost into the growth medium (43). PG degradation associated with cell wall remodelling and recycling is carried out in the periplasm by a combined action of lytic transglycosylases, amidases, and carboxy peptidases, the latter including LMM PBPs. The resulting anhydromuropeptides are transported into the cytoplasm by the highly specific AmpG permease, whereas free PG peptides are thought to be taken up by peptide permeases. While AmpG permease has been characterized extensively, much less is known about other inner membrane permeases/transporters involved in PG recycling. Our observation that the gene encoding the putative peptide uptake permease SbmA is conserved adjacent to the gene encoding PG peptidase AmpH in the genomes of Gram-negative enteric bacteria suggests that SbmA may be implicated in recycling of PG in the intestinal environment, where the ability to recycle can have survival value under nutrient-limited conditions.

FIG 7.

Schematic representation of the genomic regions adjacent to sbmA in E. coli K-12 W3110 (NCBI NC_007779.1) (26), Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strain LT2 (NCBI NC_003197.1) (52), Shigella flexneri 5 8401 (NCBI NC_008258.1) (53), Citrobacter rodentium ICC168 (GenBank FN543502.1) (54), Klebsiella pneumoniae MGH 78578 (Genome Sequencing Center of Washington University, http://genome.wustl.edu/genomes/view/klebsiella_pneumoniae/; GenBank accession no. CP000647.1), Enterobacter cloacae EcWSU1 (GenBank accession no. CP002886.1) (55). Numbers show the location in the genome. Arrows indicate gene transcription direction. One color for sbmA and yaiW (yellow) indicates that they form an operon.

The natural function of SbmA is known to be hijacked by different classes of exogenous antimicrobial peptides, including microcins B17 and B25 secreted by some enteric bacteria (31, 44), the glycopeptide bleomycin (45), antisense peptide phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomers (46), and peptide nucleic acids (47). The peptides described above kill bacteria without membrane lysis; once inside the cytoplasm, they act on one or more intracellular targets. Recently, mammalian PR-AMPs Bac5, Bac7, and PR-39 and insect PR-AMP apidaecin were added to that group (32, 34, 35). Our finding that a different insect-derived PR-AMP (pyrrhocoricin) requires SbmA to kill E. coli is in line with these studies and suggests that pyrrhocoricin also uses SbmA to traverse the inner membrane and reach the cytoplasm, limiting the spectrum of activity of the peptide to bacterial species expressing the transporter or homologous proteins.

Previous studies showed that disruption of the sbmA gene in E. coli resulted in only a slight (4- to 6-fold) attenuation in avian septicemia, suggesting that SbmA may not be essential in vivo (48). Similarly, the sbmA mutants of a closely related species, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2, were shown to be as fit as the wild-type strain both in vitro and in mice (35). Thus, the growing consensus that antimicrobial activity of several classes of PR-AMPs is dependent on the presence of a transporter that appears not to be essential in some Gram-negative bacteria and which, as shown in our study, can easily be lost by bacteria resulting in resistance raises serious concerns over the long-term viability of such compounds as antibacterial drugs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The parental E. coli K-12 C600 strain and LL-37 peptide were gifts from J. I. Rood and J. D. Boyce, respectively (Department of Microbiology, Monash University). We thank Chen Khoo for technical support.

A.R. is an Australian Research Council Research Fellow. J.G.-B. is supported by a Larkins Fellowship from Monash University.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 3 March 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2013. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. CDC, Atlanta, GA: http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hancock REW. 2007. The end of an era. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 6:28. 10.1038/nrd2223 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho J, Tambyah PA, Paterson DL. 2010. Multiresistant Gram-negative infections: a global perspective. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 23:546–553. 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32833f0d3e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scocchi M, Tossi A, Gennaro R. 2011. Proline-rich antimicrobial peptides: converging to a non-lytic mechanism of action. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 68:2317–2330. 10.1007/s00018-011-0721-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Otvos L., Jr 2002. The short proline-rich antibacterial peptide family. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 59:1138–1150. 10.1007/s00018-002-8493-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gennaro R, Zanetti M, Benincasa M, Podda E, Miani M. 2002. Pro-rich antimicrobial peptides from animals: structure, biological functions and mechanism of action. Curr. Pharm. Des. 8:763–778. 10.2174/1381612023395394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bulet P, Hetru C, Dimarcq JL, Hoffmann D. 1999. Antimicrobial peptides in insects; structure and function. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 23:329–344. 10.1016/S0145-305X(99)00015-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cudic M, Condie BA, Weiner DJ, Lysenko ES, Xiang ZQ, Insug O, Bulet P, Otvos L., Jr 2002. Development of novel antibacterial peptides that kill resistant isolates. Peptides 23:2071–2083. 10.1016/S0196-9781(02)00244-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Otvos L, Jr, Bokonyi K, Varga I, Otvos BI, Hoffmann R, Ertl HC, Wade JD, McManus AM, Craik DJ, Bulet P. 2000. Insect peptides with improved protease-resistance protect mice against bacterial infection. Protein Sci. 9:742–749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casteels P, Ampe C, Jacobs F, Vaeck M, Tempst P. 1989. Apidaecins: antibacterial peptides from honeybees. EMBO J. 8:2387–2391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bulet P, Dimarcq JL, Hetru C, Lagueux M, Charlet M, Hegy G, Van Dorsselaer A, Hoffmann JA. 1993. A novel inducible antibacterial peptide of Drosophila carries an O-glycosylated substitution. J. Biol. Chem. 268:14893–14897 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cociancich S, Dupont A, Hegy G, Lanot R, Holder F, Hetru C, Hoffmann JA, Bulet P. 1994. Novel inducible antibacterial peptides from a hemipteran insect, the sap-sucking bug Pyrrhocoris apterus. Biochem. J. 300:567–575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bulet P, Urge L, Ohresser S, Hetru C, Otvos L., Jr 1996. Enlarged scale chemical synthesis and range of activity of drosocin, an O-glycosylated antibacterial peptide from Drosophila. Eur. J. Biochem. 238:64–69. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0064q.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kragol G, Lovas S, Varadi G, Condie BA, Hoffmann R, Otvos L., Jr 2001. The antibacterial peptide pyrrhocoricin inhibits the ATPase actions of DnaK and prevents chaperone-assisted protein folding. Biochemistry 40:3016–3026. 10.1021/bi002656a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liebscher M, Roujeinikova A. 2009. Allosteric coupling between lid and interdomain linker in DnaK revealed by inhibitor binding studies. J. Bacteriol. 191:1456–1462. 10.1128/JB.01131-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scocchi M, Lüthy C, Decarli P, Mignogna G, Christen P, Gennaro R. 2009. The proline-rich antibacterial peptide Bac7 binds to and inhibits in vitro the molecular chaperone DnaK. Int. J. Pept. Res. Therapeut. 15:147–155. 10.1007/s10989-009-9182-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Czihal P, Knappe D, Fritsche S, Zahn M, Berthold N, Piantavigna S, Müller U, van Dorpe S, Herth N, Binas A, Köhler G, de Spiegeleer B, Martin LL, Nolte O, Sträter N, Alber G, Hoffmann R. 2012. Api88 is a novel antibacterial designer peptide to treat systemic infections with multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens. ACS Chem. Biol. 7:1281–1291. 10.1021/cb300063v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Otvos L, Jr, O I, Rogers ME, Consolvo PJ, Condie BA, Lovas S, Bulet P, Blaszczyk-Thurin M. 2000. Interaction between heat shock proteins and antimicrobial peptides. Biochemistry 39:14150–14159. 10.1021/bi0012843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou YS, Chen WN. 2011. iTRAQ-coupled 2-D LC-MS/MS analysis of cytoplasmic protein profile in Escherichia coli incubated with apidaecin IB. J. Proteomics 75:511–516. 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Otvos L, Jr, Wade JD, Lin F, Condie BA, Hanrieder J, Hoffmann R. 2005. Designer antibacterial peptides kill fluoroquinolone-resistant clinical isolates. J. Med. Chem. 48:5349–5359. 10.1021/jm050347i [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knappe D, Piantavigna S, Hansen A, Mechler A, Binas A, Nolte O, Martin LL, Hoffmann R. 2010. Oncocin (VDKPPYLPRPRPPRRIYNR-NH2): a novel antibacterial peptide optimized against Gram-negative human pathogens. J. Med. Chem. 53:5240–5247. 10.1021/jm100378b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Appleyard RK. 1954. Segregation of new lysogenic types during growth of a doubly lysogenic strain derived from Escherichia coli K-12. Genetics 39:440–452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amsterdam D. 1996. Susceptibility testing of antimicrobials in liquid media, p 52–111 In Lorian V. (ed), Antibiotics in laboratory medicine, 4th ed. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, MD [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chromek M, Slamová Z, Bergman P, Kovács L, Podracká L, Ehrén I, Hökfelt T, Gudmundsson GH, Gallo RL, Agerberth B, Brauner A. 2006. The antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin protects the urinary tract against invasive bacterial infection. Nat. Med. 12:636–641. 10.1038/nm1407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cudic M, Lockatell CV, Johnson DE, Otvos L., Jr 2003. In vitro and in vivo activity of an antibacterial peptide analog against uropathogens. Peptides 24:807–820. 10.1016/S0196-9781(03)00172-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayashi K, Morooka N, Yamamoto Y, Fujita K, Isono K, Choi S, Ohtsubo E, Baba T, Wanner BL, Mori H, Horiuchi T. 2006. Highly accurate genome sequences of Escherichia coli K-12 strains MG1655 and W3110. Mol. Syst. Biol. 10.1038/msb4100049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. 2007. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23:2947–2948. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bradford MM. 1976. Rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248–254. 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henderson TA, Young KD, Denome SA, Elf PK. 1997. AmpC and AmpH, proteins related to the class C beta-lactamases, bind penicillin and contribute to the normal morphology of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 179:6112–6121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gonzalez-Leiza SM, de Pedro MA, Ayala JA. 2011. AmpH, a bifunctional DD-endopeptidase and DD-carboxypeptidase of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 193:6887–6894. 10.1128/JB.05764-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laviña M, Pugsley AP, Moreno F. 1986. Identification, mapping, cloning and characterization of a gene (sbmA) required for microcin B17 action on Escherichia coli K-12. J. Gen. Microbiol. 132:1685–1693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Runti G, Del Carmen Lopez Ruiz M, Stoilova T, Hussain R, Jennions M, Choudhury HG, Benincasa M, Gennaro R, Beis K, Scocchi M. 2013. Functional characterization of SbmA, a bacterial inner membrane transporter required for importing the antimicrobial peptide Bac7(1–35). J. Bacteriol. 195:5343–5351. 10.1128/JB.00818-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corbalan N, Runti G, Adler C, Covaceuszach S, Ford R, Lamba D, Beis K, Scocchi M, Vincent PA. 2013. Functional and structural study of the dimeric inner membrane protein SbmA. J. Bacteriol. 195:5352–5361. 10.1128/JB.00824-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mattiuzzo M, Bandiera A, Gennaro R, Benincasa M, Pacor S, Antcheva N, Scocchi M. 2007. Role of the Escherichia coli SbmA in the antimicrobial activity of proline-rich peptides. Mol. Microbiol. 66:151–163. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05903.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pränting M, Negrea A, Rhen M, Andersson DI. 2008. Mechanism and fitness costs of PR-39 resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:2734–2741. 10.1128/AAC.00205-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rezuchova B, Miticka H, Homerova D, Roberts M, Kormanec J. 2003. New members of the Escherichia coli σE regulon identified by a two-plasmid system. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 225:1–7. 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00480-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strazewski P. 1988. Mispair formation in DNA can involve rare tautomeric forms in the template. Nucleic Acids Res. 16:9377–9398. 10.1093/nar/16.20.9377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Topal MD, Fresco JR. 1976. Complementary base pairing and the origin of substitution mutations. Nature 263:285–289. 10.1038/263285a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403–410. 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krebs JE, Goldstein ES, Kilpatrick ST. 2013. Transposable elements and retroviruses, p 408–440 In Lewin's essential genes, 3rd ed. Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, Sudbury, MA [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saier MH. 2000. Families of transmembrane transporters selective for amino acids and their derivatives. Microbiology 146:1775–1795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gopinath K, Venclovas C, Ioerger TR, Sacchettini JC, McKinney JD, Mizrahi V, Warner DF. 2013. A vitamin B12 transporter in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Open Biol. 3:120175. 10.1098/rsob.120175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park JT, Uehara T. 2008. How bacteria consume their own exoskeletons (turnover and recycling of cell wall peptidoglycan). Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 72:211–227. 10.1128/MMBR.00027-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salomon RA, Farias RN. 1995. The peptide antibiotic microcin 25 is imported through the TonB pathway and the SbmA protein. J. Bacteriol. 177:3323–3325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yorgey P, Lee J, Kordel J, Vivas E, Warner P, Jebaratnam D, Kolter R. 1994. Posttranslational modifications in microcin B17 define an additional class of DNA gyrase inhibitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91:4519–4523. 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Puckett SE, Reese KA, Mitev GM, Mullen V, Johnson RC, Pomraning KR, Mellbye BL, Tilley LD, Iversen PL, Freitag M, Geller BL. 2012. Bacterial resistance to antisense peptide phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomers. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:6147–6153. 10.1128/AAC.00850-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ghosal A, Vitali A, Stach JE, Nielsen PE. 2013. Role of SbmA in the uptake of peptide nucleic acid (PNA)-peptide conjugates in E. coli. ACS Chem. Biol. 8:360–367. 10.1021/cb300434e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li G, Laturnus C, Ewers C, Wieler LH. 2005. Identification of genes required for avian Escherichia coli septicemia by signature-tagged mutagenesis. Infect. Immun. 73:2818–2827. 10.1128/IAI.73.5.2818-2827.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bencivengo AM, Cudic M, Hoffmann R, Otvos L. 2003. The efficacy of the antibacterial peptide, pyrrhocoricin, is finely regulated by its amino acid residues and active domains. Lett. Pept. Sci. 8:201–209. 10.1007/BF02446518 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hoffmann R, Bulet P, Urge L, Otvos L., Jr 1999. Range of activity and metabolic stability of synthetic antibacterial glycopeptides from insects. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1426:459–467. 10.1016/S0304-4165(98)00169-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.LeVier K, Walker GC. 2001. Genetic analysis of the Sinorhizobium meliloti BacA protein: differential effects of mutations on phenotypes. J. Bacteriol. 183:6444–6453. 10.1128/JB.183.21.6444-6453.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McClelland M, Sanderson KE, Spieth J, Clifton SW, Latreille P, Courtney L, Porwollik S, Ali J, Dante M, Du F, Hou S, Layman D, Leonard S, Nguyen C, Scott K, Holmes A, Grewal N, Mulvaney E, Ryan E, Sun H, Florea L, Miller W, Stoneking T, Nhan M, Waterston R, Wilson RK. 2001. Complete genome sequence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2. Nature 413:852–856. 10.1038/35101614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nie H, Yang F, Zhang X, Yang J, Chen L, Wang J, Xiong Z, Peng J, Sun L, Dong J, Xue Y, Xu X, Chen S, Yao Z, Shen Y, Jin Q. 2006. Complete genome sequence of Shigella flexneri 5b and comparison with Shigella flexneri 2a. BMC Genomics 7:173. 10.1186/1471-2164-7-173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Petty NK, Bulgin R, Crepin VF, Cerdeno-Tarraga AM, Schroeder GN, Quail MA, Lennard N, Corton C, Barron A, Clark L, Toribio AL, Parkhill J, Dougan G, Frankel G, Thomson NR. 2010. The Citrobacter rodentium genome sequence reveals convergent evolution with human-pathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 192:525–538. 10.1128/JB.01144-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Humann JL, Wildung M, Cheng C-H, Lee T, Drew JC, Triplett EW, Main D, Schroeder BK. 2011. Complete genome of the onion pathogen Enterobacter cloacae EcWSU1. Stand. Genomic Sci. 5:279–286. 10.4056/sigs.2174950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]