Abstract

The acquired carbapenem-hydrolyzing oxacillinase (OXA) OXA-143 has thus far been detected only in Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from Brazil. The aim of this study was to characterize three OXA-143 variants: OXA-231 and OXA-253 from carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii isolates and OXA-255 in a carbapenem-susceptible Acinetobacter pittii isolate originating from Brazil, Honduras, and the United States, respectively. The 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) technique identified the same transcription initiation site for all blaOXA-143-like genes and revealed differences in the putative promoter regions. However, all cloned OXA-143 variants conferred carbapenem resistance on A. baumannii ATCC 17978 and OXA-255 conferred carbapenem resistance on A. pittii SH024, which was correlated with blaOXA-255 gene expression. This is the first description of OXA-143-like outside A. baumannii. Detection of OXA-143-like in the United States and Honduras indicates its dissemination through the American continent.

INTRODUCTION

Acinetobacter baumannii and Acinetobacter pittii are members of the “A. baumannii group,” which, together with A. nosocomialis, comprise three phenotypically similar clinically relevant Acinetobacter species (1, 2). A. baumannii and A. pittii cause nosocomial infections and are associated with clinical outbreaks (3–5). While A. pittii is frequently found on both intact and diseased human skin and mucous membranes, it is prevalent on general wards and is usually susceptible to carbapenems. A. baumannii mainly affects patients in intensive care (6, 7). Carbapenems are considered the drugs of choice to treat infections caused by multidrug-resistant (MDR) A. baumannii. However, over the last decade carbapenem resistance has increased in A. baumannii, compromising available treatment options. The most common carbapenem resistance determinants in Acinetobacter spp. are carbapenem-hydrolyzing oxacillinases (OXA). A. baumannii isolates harbor the intrinsic OXA-51, of which >80 variants have been identified, and five groups of acquired OXA (OXA-23, -40, -58, -143, and -235) (8, 9). Of these, only OXA-23, OXA-40, and OXA-58 have been detected in other Acinetobacter species. For example, blaOXA-23-like, blaOXA-40-like, and blaOXA-58-like have been described for carbapenem-nonsusceptible A. pittii isolates from China, Colombia, France, Germany, and the Irish Republic (10–13). blaOXA genes are often associated with insertion sequences (IS) that mediate their mobility and overexpression, thereby leading to carbapenem resistance. However, blaOXA-40 and blaOXA-143 seem to be exceptions to this (14). OXA-143 was first identified in 2009 in a carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii isolate and can be detected by multiplex PCR (15, 16). To date, OXA-143 has been reported only for A. baumannii isolates from certain states in Brazil (15, 17). However, outside Brazil, most blaOXA screening is performed using the OXA multiplex PCR described by Woodford et al., which does not include blaOXA-143-like primers (18).

The aim of this study was to characterize blaOXA-143 variants in two A. baumannii isolates and one A. pittii isolate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, species identification, carbapenem susceptibility testing, and A. baumannii molecular typing.

Carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii isolates AF81 and AF260 as well as carbapenem-susceptible A. pittii isolate AF726 were initially identified as blaOXA-143-like positive by multiplex PCR (Table 1) (16). AF81 originated from Brazil, AF260 originated from Honduras, and AF726 originated from the state of Indiana in the United States. Imipenem and meropenem susceptibility of Acinetobacter isolates and transformants was determined by Etest (bioMérieux, Nürtingen, Germany) according to standard protocols. To confirm species identification, gyrB multiplex PCR and rpoB sequencing were performed, as described previously (1). Isolates AF81 and AF260 were typed by repetitive sequence-based PCR (rep-PCR) (19).

TABLE 1.

Characterization of clinical isolates AF81, AF260, and AF726a

| Isolate | Country of origin | Date of isolation (mo/day/yr) | Carbapenem MIC (μg/ml) |

Species identification | OXA-MPLX PCR | OXA-51 variant and rep-PCR type | OXA-143 variant | Replicon type and plasmid transfer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPM | MEM | ||||||||

| AF81 | Brazil | 01/04/2008 | >32 | >32 | A. baumannii | 51, 143 | OXA-51, unclustered | 231 | GR 19, transferable |

| AF260 | Honduras | 02/01/2008 | >32 | >32 | A. baumannii | 51, 143 | OXA-65, IC5 | 253 | GR 12, transferable |

| AF726 | USA (Indiana) | 08/29/2007 | 0.75 | 1 | A. pittii | 143 | ND | 255 | ND |

IPM, imipenem; MEM, meropenem; ND, not detected; MPLX, multiplex; IC, international clone; GR, group.

PCR, sequencing, and cloning.

The presence of blaOXA genes was confirmed by multiplex PCR as described previously (8). Primers used for sequencing and cloning are shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material. blaOXA-51-like sequencing of isolates AF81 and AF260 was performed using primers OXA-69A and OXA-69B (20). blaOXA-143-like of isolate AF81 was amplified using primer pair OXA-231_F and OXA-231_R, cloned into pCR4-TOPO for sequencing (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany), and transferred into chemically competent Escherichia coli DH5α cells (New England BioLabs, Frankfurt am Main, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. To sequence blaOXA-143-like from isolate AF260, total DNA was restricted by EcoRV endonuclease and shotgun cloned into pBBR1MCS, as previously described (21). blaOXA-143-like-containing inserts of pBBR1MCS and pCR4-TOPO were amplified by PCR and sequenced by primer walking. To sequence blaOXA-143-like of AF726, total DNA was restricted by EcoRI endonuclease, self-ligated using Quick ligase (New England BioLabs), amplified by inverse PCR, and sequenced by primer walking. The blaOXA-143 variants were numbered by the Lahey β-lactamase database (http://www.lahey.org/Studies/).

Assessment of blaOXA-143-like transferability.

To determine the transferability of blaOXA-143 variants, plasmids isolated from AF81, AF260, and AF726 were used for transformation. Electroporation was performed with reference strains A. baumannii ATCC 17978 (plasmids of AF81 and AF260) and A. pittii SH024 (plasmid of AF726). Selection of A. baumannii transformants was performed on Mueller-Hinton agar (Oxoid, Wesel, Germany) supplemented with ticarcillin (150 μg/ml). Selection of A. pittii transformants was performed on Mueller-Hinton agar supplemented with 25, 40, 60, or 80 μg/ml of ticarcillin. The presence of blaOXA-143-like in the transformants was confirmed by PCR. In addition, plasmid replicon typing was performed with the clinical isolates, the reference strains, and the OXA transformants, as previously described (22).

Effect of OXA-143 variants on carbapenem susceptibility.

To further characterize the impact of the three blaOXA-143-like variants on carbapenem susceptibility, the genes were amplified using primers listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material, cloned into the shuttle vector pWH1266, and transferred into A. baumannii reference strain ATCC 17978 by electroporation (23). Transformants were selected on Luria-Bertani agar (Oxoid) supplemented with 30 μg/ml of tetracycline. In addition, blaOXA-143-like of isolate AF726 was transferred into the A. pittii reference strain SH024 using the same selective medium.

Determination of blaOXA-143-like transcriptional initiation sites and gene expression.

To identify the transcriptional start site of the three blaOXA-143 variants, 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) was performed using the 5′ RACE system for rapid amplification of cDNA ends, version 2.0 (Invitrogen). Primers used for 5′ RACE are shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Total RNA was prepared using the Qiagen RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Amplicons of dC-tailed cDNA were purified and sequenced. In order to analyze differences in carbapenem susceptibility, blaOXA-143-like expression in the A. pittii strains was investigated based on independent experiments. Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed as described previously (8). blaOXA-143-like expression in the A. pittii transformant was compared to gene expression in AF726 and was normalized against expression of the rpoB reference gene. Standard curves for blaOXA-143-like and rpoB were included. Primers used for standard curves and qRT-PCR are shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The blaOXA-231, blaOXA-253, and blaOXA-255 nucleotide sequences are available in GenBank under the following accession numbers: JQ326200 (blaOXA-231), KC479324 (blaOXA-253), and KC479325 (blaOXA-255).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Species identification, blaOXA detection, OXA-51-like sequencing, and A. baumannii typing.

gyrB multiplex PCR and rpoB sequencing confirmed AF81 and AF260 as A. baumannii and AF726 as A. pittii. Multiplex PCR confirmed the presence of blaOXA-143-like in all three isolates, as well as the presence of blaOXA-51-like in the two A. baumannii isolates. Sequencing of blaOXA-51-like identified blaOXA-51 and blaOXA-65 in isolates AF81 and AF260, respectively, which were not associated with ISAba1 (Table 1). Rep-PCR identified AF260 as international clone 5 (24), while AF81 did not cluster with any of the international clones. However, AF81 shared 98.5% similarity to A. baumannii 135040, the strain in which OXA-143 was first identified (15).

Identification of OXA-143-like-encoding genes.

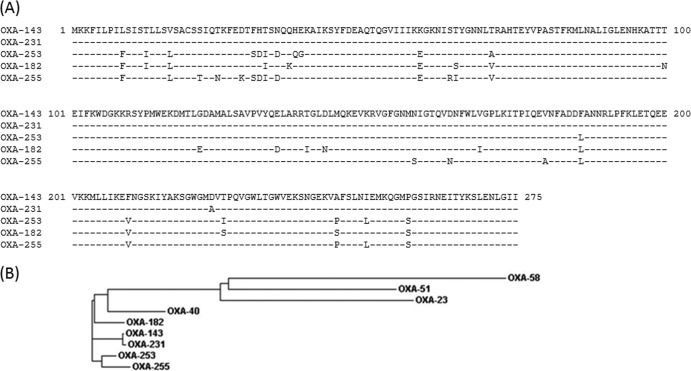

To amplify and sequence blaOXA-143-like, flanking primers were designed based on blaOXA-143 (GenBank accession no. GQ861437), which amplified the gene in AF81 but failed to amplify the gene in the other two isolates. Therefore, shotgun cloning was performed, and we cloned from AF260 an approximately 10-kb insert into pBBR1MCS, which was partially sequenced. Inverse PCR of AF726 revealed the presence of an approximately 3.5-kb amplicon which was also partially sequenced. Based on these sequences, blaOXA-143-like flanking primers specific for AF260 and AF726 were designed and used for cloning into pWH1266 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). blaOXA-143-like sequencing revealed three OXA-143 variants which were assigned as OXA-231 (AF81), OXA-253 (AF260), and OXA-255 (AF726) by the Lahey β-lactamase database (Table 1). OXA-231 possessed one amino acid substitution compared to OXA-143 (D224→A) (Fig. 1A) and has been recently detected in another A. baumannii isolate from Brazil (25). OXA-253 shared 94% amino acid identity with OXA-143 (17 amino acid substitutions), while OXA-255 shared 92% amino acid identity with OXA-143 (21 amino acid substitutions). High similarity of OXA-253 and OXA-255 was also seen with OXA-182 (17 and 22 amino acid substitutions, respectively [Fig. 1A]). OXA-182 was detected in South Korea using blaOXA-143-like primers (26). Although OXA-253 and OXA-255 share similar amino acid identity with OXA-182 and OXA-143, they differ in their numbers of identical and positive (including conservative substitutions) amino acids. OXA-253 shares 258 of 275 identical amino acids with both enzymes, while the number of positive amino acids it shares with OXA-182 is higher than it shares with OXA-143 (266 and 262, respectively). In contrast, OXA-255 shares more identical amino acids with OXA-143 than OXA-182 (254 and 253, respectively) but fewer positive amino acids (261 and 264, respectively). This can be visualized in a phylogenetic tree of OXA variants (Fig. 1B). Thus, the OXA-143-like group shows large variations suggesting an ancient lineage, similar to OXA-51-like (27, 28).

FIG 1.

(A) Alignment of OXA-143-like amino acid sequences. Variants are sorted according to their amino acid identity with OXA-143. OXA-231 is closely related to OXA-143, with only one amino acid change at position 224. (B) Phylogenetic tree of OXA variants. This neighbor-joining tree was generated using Clustal Omega (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/).

blaOXA-143-like transferability.

Clinical plasmids containing blaOXA-231 and blaOXA-253 were transferable into ATCC 17978. Replicon typing of ATCC 17978 transformants revealed that blaOXA-231 and blaOXA-253 were encoded on plasmids that harbored group (GR) 19 and GR 12 replicase genes, respectively (Table 1). Despite repeated attempts to transfer blaOXA-255 and selection of transformants using ticarcillin concentrations as low as 25 μg/ml, the gene was not transferrable to either A. pittii or A. baumannii reference strains using plasmid preparations from AF726. Furthermore, plasmid replicon typing did not identify a known replicon in AF726. However, sequencing of blaOXA-255 flanking regions identified sequences bracketing the blaOXA-255 as plasmid sequences, which might indicate that this gene was initially plasmid located and subsequently integrated into the chromosome (see below).

Genetic environment of blaOXA-143-like.

Alignment of blaOXA and the surrounding sequences revealed high similarity of blaOXA-231 flanking regions compared to blaOXA-143 (GenBank accession no. GQ861437). The degrees of similarity were 98% for 193 bp upstream of blaOXA-231 and 99% for 198 bp downstream of the gene. Accordingly, the start codon of a replicase gene was detected downstream of blaOXA-231 (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Flanking regions of the other two bla genes were not conserved, which explains why we were initially unable to amplify the whole genes from AF260 and AF726.

Downstream of blaOXA-255, a putative peptidase gene was detected which showed 77% similarity to a peptidase encoded on A. baumannii plasmid p3ABSDF (GenBank accession no. CU468233) (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Upstream of the blaOXA-255 gene, an open reading frame coding for 136 amino acids of a putative TonB-dependent receptor plug domain was detected. Conserved domains of the plug superfamily function as gates within channel-forming TonB-dependent receptors, which are important for the iron uptake in Gram-negative bacteria (29). A BLAST search revealed 51% amino acid identity with a hypothetical protein previously described for Acinetobacter species NIPH1867 (locus tag WP_005210788), containing a TonB-dependent siderophore receptor domain.

In contrast, the sequence upstream of blaOXA-253 showed 91% similarity with the sequence upstream of blaOXA-40-like in A. baumannii plasmid pAC92 (GenBank accession no. JN982952), containing a putative inner membrane protein and an XerC/D recombination site (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Analysis of the partial protein sequence revealed only one amino acid difference compared to another A. baumannii membrane protein (locus tag WP_000465837). The XerC/D site (5′-ACTTCGTATAATATCCATTATGTTAAAT-3′) was located 74 bp upstream of blaOXA-253. In addition, another putative XerC/D recombination site (5′-ATATTGTATAACCTATATTATGTTATTT-3′) was identified 111 bp downstream of the gene. XerC/D recombination sites are often associated with blaOXA-40-like genes. However, our results indicate that the three OXA-143 variants described in this report might have evolved from different progenitors. This might also include OXA-182, as a putative transposase gene has been detected downstream of the bla gene, which is not part of the flanking regions of the other variants. Interestingly, the available upstream sequence of blaOXA-182 (20 bp) is 100% identical with the same region upstream of blaOXA-143, which further indicates relatedness of this OXA to the OXA-143 group.

Impact of OXA-231, OXA-253, and OXA-255 on carbapenem susceptibility.

Cloning of blaOXA-143-like into pWH1266 and transfer into A. baumannii ATCC 17978 conferred carbapenem resistance. Imipenem and meropenem MICs increased from 0.25 μg/ml in the reference strain to >32 μg/ml in all transformants (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). Furthermore, OXA-255conferred carbapenem resistance on A. pittii SH024, with imipenem and meropenem MICs increasing from 0.25 and 0.5 μg/ml to 16 and >32 μg/ml, respectively (see Table S3 in the supplemental material).

Identification of blaOXA-143-like transcription initiation sites and blaOXA-255 expression.

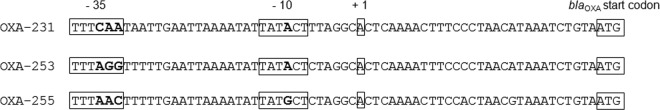

In order to identify the transcriptional initiation site of blaOXA-143-like and deduce the promoter region, 5′ RACE was performed. We identified the same transcriptional initiation site for all blaOXA-143-like genes 30 bp upstream of the start codon (Fig. 2). Six base pairs upstream of the transcriptional initiation site, the same −10 box was identified in AF81 and AF260 (TATACT), while a substitution was present in AF726 (TATGCT). Interestingly, sequence alignment of the blaOXA-231 and blaOXA-143 upstream regions revealed the presence of the same putative promoters. The spacer region between the −10 and −35 boxes had an optimal size of 17 bp. Putative −35 boxes harbored 3 nucleotide differences (Fig. 2). Based on carbapenem MICs of ATCC 17978 transformants harboring recombinant pWH1266, OXA-143-like variants and their different promoter sequences did not seem to significantly influence carbapenem susceptibility (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). However, because OXA-255 did not confer carbapenem resistance on the clinical isolate AF726, while OXA-255-transformed ATCC 17978 and A. pittii SH024 were carbapenem resistant, we investigated expression of blaOXA-255 in A. pittii. Expression analysis revealed that although blaOXA-255 was expressed in AF726, it was overexpressed 24-fold in the SH024 transformant, which correlated with carbapenem resistance. This suggests that the blaOXA-255 promoter is functioning and that there may be other regulatory mechanisms that affect its overexpression in the clinical isolate.

FIG 2.

Alignment of blaOXA-143-like predicted promoter sequences. The start codon, the transcription initiation site, and the −10 and −35 boxes are boxed. Differences in the −10 and −35 boxes are marked by bold type.

Conclusion.

To date, the OXA-143 subclass has predominantly been described as occurring in carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii isolates from Brazil (17, 25, 30, 31). This study constitutes the first detection of OXA-143 variants in Honduras and the United States and indicates the spread of this carbapenemase in the Western Hemisphere. The occurrence of OXA-255 conferring carbapenem resistance on A. baumannii and on A. pittii highlights the potential of this OXA to spread within the genus Acinetobacter.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Meredith Hackel for kindly providing the Acinetobacter isolates.

P.G.H. and H.S. were supported by a grant from Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF), Germany, Klinische Forschergruppe Infektiologie (grant number 01 KI 0771). E.Z. was supported by Magic Bullet. Magic Bullet is a project funded by the European Union-Directorate General for Research and Innovation through the Seventh Framework Program for Research and Development (grant agreement 278232) and has been running since 1 January 2012 (duration, 36 months).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 24 February 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02618-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nemec A, Krizova L, Maixnerova M, van der Reijden TJ, Deschaght P, Passet V, Vaneechoutte M, Brisse S, Dijkshoorn L. 2011. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-Acinetobacter baumannii complex with the proposal of Acinetobacter pittii sp. nov. (formerly Acinetobacter genomic species 3) and Acinetobacter nosocomialis sp. nov. (formerly Acinetobacter genomic species 13TU). Res. Microbiol. 162:393–404. 10.1016/j.resmic.2011.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dijkshoorn L, Nemec A, Seifert H. 2007. An increasing threat in hospitals: multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5:939–951. 10.1038/nrmicro1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peleg AY, de Breij A, Adams MD, Cerqueira GM, Mocali S, Galardini M, Nibbering PH, Earl AM, Ward DV, Paterson DL, Seifert H, Dijkshoorn L. 2012. The success of Acinetobacter species; genetic, metabolic and virulence attributes. PLoS One 7:e46984. 10.1371/journal.pone.0046984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Visca P, Seifert H, Towner KJ. 2011. Acinetobacter infection—an emerging threat to human health. IUBMB Life 63:1048–1054. 10.1002/iub.534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang J, Chen Y, Jia X, Luo Y, Song Q, Zhao W, Wang Y, Liu H, Zheng D, Xia Y, Yu R, Han X, Jiang G, Zhou Y, Zhou W, Hu X, Liang L, Han L. 2012. Dissemination and characterization of NDM-1-producing Acinetobacter pittii in an intensive care unit in China. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18:E506–E513. 10.1111/1469-0691.12035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peleg AY, Seifert H, Paterson DL. 2008. Acinetobacter baumannii: emergence of a successful pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 21:538–582. 10.1128/CMR.00058-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schleicher X, Higgins PG, Wisplinghoff H, Korber-Irrgang B, Kresken M, Seifert H. 2013. Molecular epidemiology of Acinetobacter baumannii and Acinetobacter nosocomialis in Germany over a 5-year period (2005–2009). Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 19:737–742. 10.1111/1469-0691.12026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Higgins PG, Perez-Llarena FJ, Zander E, Fernandez A, Bou G, Seifert H. 2013. OXA-235, a novel class D β-lactamase involved in resistance to carbapenems in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:2121–2126. 10.1128/AAC.02413-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans BA, Hamouda A, Amyes SG. 2013. The rise of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Curr. Pharm. Des. 19:223–238. 10.2174/138161213804070285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boo TW, Walsh F, Crowley B. 2006. First report of OXA-23 carbapenemase in clinical isolates of Acinetobacter species in the Irish Republic. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 58:1101–1102. 10.1093/jac/dkl345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans BA, Hamouda A, Towner KJ, Amyes SG. 2010. Novel genetic context of multiple blaOXA-58 genes in Acinetobacter genospecies 3. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:1586–1588. 10.1093/jac/dkq180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonnin RA, Docobo-Pérez F, Poirel L, Villegas M-V, Nordmann P. 2014. Emergence of OXA-72-producing Acinetobacter pittii clinical isolates. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 43:195–196. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2013.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang H, Guo P, Sun H, Yang Q, Chen M, Xu Y, Zhu Y. 2007. Molecular epidemiology of clinical isolates of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter spp. from Chinese hospitals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:4022–4028. 10.1128/AAC.01259-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poirel L, Naas T, Nordmann P. 2010. Diversity, epidemiology, and genetics of class D β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:24–38. 10.1128/AAC.01512-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins PG, Poirel L, Lehmann M, Nordmann P, Seifert H. 2009. OXA-143, a novel carbapenem-hydrolyzing class D β-lactamase in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:5035–5038. 10.1128/AAC.00856-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins PG, Lehmann M, Seifert H. 2010. Inclusion of OXA-143 primers in a multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for genes encoding prevalent OXA carbapenemases in Acinetobacter spp. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 35:305. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mostachio AK, Levin AS, Rizek C, Rossi F, Zerbini J, Costa SF. 2012. High prevalence of OXA-143 and alteration of outer membrane proteins in carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter spp. isolates in Brazil. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 39:396–401. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woodford N, Ellington MJ, Coelho JM, Turton JF, Ward ME, Brown S, Amyes SG, Livermore DM. 2006. Multiplex PCR for genes encoding prevalent OXA carbapenemases in Acinetobacter spp. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 27:351–353. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Healy M, Huong J, Bittner T, Lising M, Frye S, Raza S, Schrock R, Manry J, Renwick A, Nieto R, Woods C, Versalovic J, Lupski JR. 2005. Microbial DNA typing by automated repetitive-sequence-based PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:199–207. 10.1128/JCM.43.1.199-207.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Héritier C, Poirel L, Fournier PE, Claverie JM, Raoult D, Nordmann P. 2005. Characterization of the naturally occurring oxacillinase of Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:4174–4179. 10.1128/AAC.49.10.4174-4179.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfeifer Y, Wilharm G, Zander E, Wichelhaus TA, Gottig S, Hunfeld KP, Seifert H, Witte W, Higgins PG. 2011. Molecular characterization of blaNDM-1 in an Acinetobacter baumannii strain isolated in Germany in 2007. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:1998–2001. 10.1093/jac/dkr256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bertini A, Poirel L, Mugnier PD, Villa L, Nordmann P, Carattoli A. 2010. Characterization and PCR-based replicon typing of resistance plasmids in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:4168–4177. 10.1128/AAC.00542-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi KH, Kumar A, Schweizer HP. 2006. A 10-min method for preparation of highly electrocompetent Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells: application for DNA fragment transfer between chromosomes and plasmid transformation. J. Microbiol. Methods 64:391–397. 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins PG, Dammhayn C, Hackel M, Seifert H. 2010. Global spread of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:233–238. 10.1093/jac/dkp428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gionco B, Pelayo JS, Venancio EJ, Cayo R, Gales AC, Carrara-Marroni FE. 2012. Detection of OXA-231, a new variant of blaOXA-143, in Acinetobacter baumannii from Brazil: a case report. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67:2531–2532. 10.1093/jac/dks223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim CK, Lee Y, Lee H, Woo GJ, Song W, Kim MN, Lee WG, Jeong SH, Lee K, Chong Y. 2010. Prevalence and diversity of carbapenemases among imipenem-nonsusceptible Acinetobacter isolates in Korea: emergence of a novel OXA-182. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 68:432–438. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evans BA, Hamouda A, Towner KJ, Amyes SG. 2008. OXA-51-like β-lactamases and their association with particular epidemic lineages of Acinetobacter baumannii. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 14:268–275. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01919.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zander E, Nemec A, Seifert H, Higgins PG. 2012. Association between β-lactamase-encoding blaOXA-51 variants and DiversiLab rep-PCR-based typing of Acinetobacter baumannii isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50:1900–1904. 10.1128/JCM.06462-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferguson AD, Deisenhofer J. 2002. TonB-dependent receptors—structural perspectives. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1565:318–332. 10.1016/S0005-2736(02)00578-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Werneck JS, Picao RC, Girardello R, Cayo R, Marguti V, Dalla-Costa L, Gales AC, Antonio CS, Neves PR, Medeiros M, Mamizuka EM, Elmor de Araujo MR, Lincopan N. 2011. Low prevalence of blaOXA-143 in private hospitals in Brazil. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:4494–4495; author reply, 4495. 10.1128/AAC.00295-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Antonio CS, Neves PR, Medeiros M, Mamizuka EM, Elmor de Araujo MR, Lincopan N. 2011. High prevalence of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii carrying the blaOXA-143 gene in Brazilian hospitals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:1322–1323. 10.1128/AAC.01102-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.