Abstract

Ceftaroline has been approved for acute bacterial skin infections and community-acquired bacterial pneumonia. Limited clinical experience exists for use outside these indications. The objective of this study was to describe the outcomes of patients treated with ceftaroline for various infections. Retrospective analyses of patients receiving ceftaroline ≥72 h from 2011 to 2013 were included. Clinical and microbiological outcomes were analyzed. Clinical success was defined as resolution of all signs and symptoms of infection with no further need for escalation while on ceftaroline treatment during hospitalization. A total of 527 patients received ceftaroline, and 67% were treated for off-label indications. Twenty-eight percent (148/527) of patients had bacteremia. Most patients (80%) were initiated on ceftaroline after receipt of another antimicrobial, with 48% citing disease progression as a reason for switching. The median duration of ceftaroline treatment was 6 days, with an interquartile range of 4 to 9 days. A total of 327 (62%) patients were culture positive, and the most prevalent pathogen was Staphylococcus aureus, with a frequency of 83% (271/327). Of these patients, 88.9% (241/271) were infected with methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA). Clinically, 88% (426/484) achieved clinical success and hospital mortality was seen in 8% (40/527). While on ceftaroline, adverse events were experienced in 8% (41/527) of the patients and 9% (28/307) were readmitted within 30 days after discharge for the same infection. Patients treated with ceftaroline for both FDA-approved and off-label infections had favorable outcomes. Further research is necessary to further describe the role of ceftaroline in a variety of infections and its impact on patient outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

Antimicrobial resistance in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens continues to challenge clinicians in the management of all types of infections. A limited number of new or novel compounds are available to address antimicrobial resistance due to these difficult-to-treat bacterial pathogens (1). In particular, the emergence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in both hospital and community settings continues to be a clinical and economic burden. Reports of vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (VISA) and heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (hVISA) and their association with vancomycin treatment failure have increased the need for alternative antimicrobials for the treatment of MRSA infections (2–4). In addition, there have been increasing reports of clinical failures and the emergence of resistance with other antimicrobials such as linezolid and daptomycin (4–6). These disturbing trends suggest a need for new and effective alternative treatment strategies for MRSA infections.

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) has launched the “10 × 20” initiative to address the limited pipeline for novel therapeutics to treat drug-resistant pathogens, including MRSA (7). Since the IDSA's initiative, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved two novel antimicrobial agents. One of these new antimicrobial agents is ceftaroline fosamil, a prodrug form of ceftaroline, which is an advanced-generation cephalosporin that has bactericidal activity against Gram-negative pathogens such as Enterobacteriaceae and Haemophilus influenzae and Gram-positive pathogens such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus pyogenes, Streptococcus agalactiae, and Staphylococcus aureus. Of interest, ceftaroline binds to PBP 2a and therefore is the first beta-lactam with potent bactericidal activity against MRSA. Ceftaroline fosamil was approved by the U.S. FDA for the treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI) and community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP) in October 2010 (8).

Ceftaroline has also performed well against Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens in multiple clinical studies (9–12). For the treatment of CABP, including infections with multidrug-resistant S. pneumoniae, pooled success frequency was 84.3% (11, 12). For the treatment of ABSSSI, including infections with MRSA, pooled success frequency was 91.6%. When used for the treatment of ABSSSI caused by MRSA, pooled success frequency was 93.4% (9, 10). While these clinical success frequencies are encouraging, there are few data available regarding the success of ceftaroline in more-complicated infections such as recurrent ABSSSI, hospital-acquired bacterial pneumonia, or complicated bloodstream infections (BSI). To date, there have only been a few cases reported in the literature on the use of ceftaroline in complicated infections outside its approved indications (13, 14). Thus, in the absence of comparative data from randomized trials, clinicians are routinely searching for additional information on the use of these new agents in complicated situations such as multidrug-resistant infections or in patients who are not responding to standard treatment. Therefore, the objectives of this retrospective observational case series were to describe and characterize outcomes of patients who were treated with ceftaroline for a variety of infections types.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was a retrospective observational study conducted at the Detroit Medical Center (Detroit, MI), The Ohio State University Medical Center (Columbus, OH), University of Florida Health Shands Hospital (Gainesville, FL), Henry Ford Hospital (Detroit, MI), and Alexian Brothers Medical Center (Elk Grove, IL). Data were collected retrospectively through medical records, and each respective Institutional Review Board provided their approval prior to commencement of the study. All patients that received ceftaroline for ≥72 h from 1 January 2011 through 30 June 2013 were included in this study. Patients were excluded if ceftaroline was used for prophylactic therapy or if they had an infection caused by a pathogen known to be resistant to ceftaroline (e.g., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae, or fungal, parasitic, or viral agents) alone without a known MRSA infection.

The data collected through medical records included baseline patient demographics, comorbid conditions, and APACHE II and Charlson comorbidity index scores at the time of the infection (15, 16); the microbiological data included the infecting organism and susceptibilities, source of infection, and dosage and duration of all antimicrobial therapies. The site of infection was determined by the diagnosing practitioner's discretion, with the exception of infective endocarditis (IE) (17) and bone and joint infection (18), which were assessed using standardized criteria. Outcomes that were evaluated include clinical and microbiological success, hospital and intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay, adverse drug events, mortality during hospitalization, 30-day readmission, and 30-day mortality. Adverse drug events were recorded only if a direct causal relationship to ceftaroline was suspected and documented in the patients' medical records by the primary health care provider. Clinical success was defined as resolution of all signs and symptoms of infection with no need for escalation of antimicrobials while on ceftaroline. Clinical failure was defined as inadequate response to ceftaroline therapy or resistant, worsening, or new recurrent signs and symptoms at the end of ceftaroline therapy. Microbiological response was evaluated in patients with follow-up cultures at the end of ceftaroline therapy during hospitalization. Microbiological success was defined as eradication of the infecting organism, and microbiological failure was defined as persistence of the infecting organism (9, 10). Patients with nonevaluable outcomes were those for whom medical records did not contain all necessary information to determine the response at the end of inpatient ceftaroline therapy. The rationale to use ceftaroline was also collected if this information was documented in the patient's medical records by the prescriber. Categories of rationale for ceftaroline use were disease progression (19), simplification of regimen from multiple medications, adverse or allergic reaction to prior antimicrobial agent, anticipated risk of toxicity to other antimicrobial agents, and preferred empirical coverage for MRSA. When available, isolates were collected from one of the participating centers (Detroit Medical Center) retrospectively for extended microbiologic assessment at a central research laboratory facility (Anti-Infective Research Laboratory, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI). S. aureus isolates were screened and confirmed for hVISA as previously described (20, 21) for bloodstream pathogens, and nonsusceptible MICs were confirmed by methods using Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines or the manufacturer's package insert (6, 8, 22). Study data were collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), Vanderbilt University, electronic data capture tools hosted at Wayne State University (23).

SPSS Statistics, version 21.0 (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), was used to perform descriptive statistics, including data frequencies and distributions for categorical data; median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous data were used to illustrate the study population.

RESULTS

Overall, 630 patients were given ceftaroline over the 2.5-year analysis period; of these, 527 (83.7%) received ceftaroline for at least 72 h during hospitalization and were included in both effectiveness and safety evaluation. (See Table S1 in the supplemental material for a distribution of patients from each hospital site.) The classification of infections and number of patients treated by ceftaroline was as follows: ABSSSI, 185 patients (35.1%); bacteremia, 148 patients (28.1%); pneumonia, 99 patients (18.8%); bone and joint infection, 81 patients (15.4%); and other type, 14 patients (2.7%). Within this cohort, 33.2% (175/527) were given ceftaroline for FDA-approved indications, 82.3% (144/175) for ABSSSI, and 17.7% (31/175) for CABP. The most common off-label indication for ceftaroline use was bacteremia (148 patients [42%]), followed by bone and joint infections (81 [23%]), pneumonia (which consisted of nosocomial pneumonia and/or MRSA pneumonia; 68 [19.3%]), other ABSSSI (necrotizing fasciitis, gangrene, or diabetic foot infections; 41 [11.6%]), and 14 other infections including 7 (2%) intra-abdominal, 4 (1.1%) central nervous system (spinal epidural or brain abscess), and 3 (0.9%) genitourinary infections, documented as their primary infection per prescriber. Patients were predominately older adults with a median age of 60 years and commonly had predisposing baseline conditions such as diabetes and heart disease. See Table 1 for the common baseline characteristics of the population. The concomitant percentages for sites of infections with bacteremia were 26.3% (35/133) for infective endocarditis, 23.3% (31/133) for bone and joint infection, 22.6% (30/133) for pneumonia, 7.5% (10/133) for ABSSSI, 7.5% (10/133) for intravenous-catheter-related infection, 5.3% (7/133) for prosthetic-device-related infection, 4.5% (6/133) for deep-abscess-related (e.g., epidural and brain) infection, and 3% (4/133) for unknown source.

TABLE 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients treated with ceftaroline

| Baseline characteristic | Median value (IQR) or no. (%) of patients (n = 527) |

|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 60 (49–72) |

| APACHE II score | 11 (8–16) |

| Charlson comorbidity score | 2 (1–4) |

| Actual body wt (kg) | 80.2 (68.5–101) |

| Male gender | 304 (57.7) |

| ICU admission | 170 (32.3) |

| Prior hospitalization (1 yr) | 314 (59.6) |

| Previous antibiotics (3 mo) | 158 (30) |

| Previously given vancomycin (6 mo) | 98 (18.6) |

| Previous surgery | 120 (22.8) |

| Previous MRSA infection (1 yr) | 85 (16.1) |

| Diabetes | 212 (40.2) |

| Heart disease | 177 (33.6) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 118 (22.4) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 67 (12.7) |

| Hemodialysis | 43 (8.2) |

Three hundred twenty-seven (62%) patients had positive cultures, with Staphylococcus aureus (82.9%, 271/327) being the most commonly identified pathogen. Of these, 88.9% (241/271) were MRSA. Of 55 blood isolates of MRSA screened, six MRSA from IE cases were identified as hVISA. There were 68 other Gram-positive pathogens (27 coagulase-negative staphylococci, 21 streptococci, and 17 others), and 67 infections were caused by Gram-negative organisms, most frequently Klebsiella pneumoniae. Polymicrobial infections were observed in 22.3% (73/327) of patients, with the most common being Enterobacteriaceae with S. aureus. One hundred five S. aureus isolates had ceftaroline susceptibility performed by Etest based on the participating institution's clinical laboratory with a reported median MIC of 0.5 mg/liter (range, 0.25 to 2 mg/liter). Three (2.9%) of these isolates were found to be nonsusceptible to ceftaroline, with MICs of 1.5 mg/liter or 2 mg/liter.

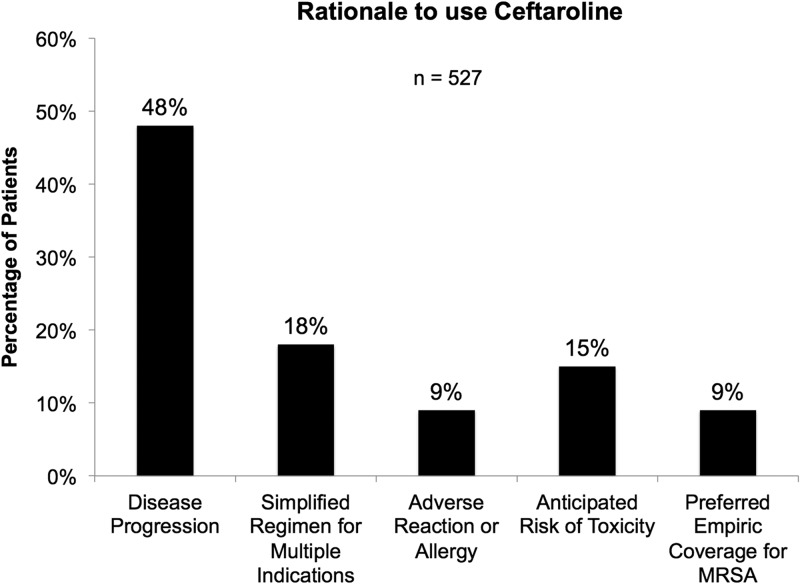

Overall, 422 (80.1%) patients were given another antimicrobial prior to the start of ceftaroline, and the median time to switching to ceftaroline was 3 days (IQR, 1 to 6 days). Vancomycin, daptomycin, and linezolid were the three most common antimicrobials prescribed prior to the initiation of ceftaroline (70% [295/422], 14% [60/422], and 6% [24/422], respectively). Figure 1 describes the rationale for use of ceftaroline, most frequently prescribed to patients following disease progression on prior therapy (48%, 253/527). Of these, 10 patients were found to have an elevated vancomycin MIC, 1.5 mg/liter or higher, and 14 cases had vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (VISA) and/or daptomycin-nonsusceptible (DNS) S. aureus. Four hundred fifty-two (85.8%) patients received ceftaroline dosed at 600 mg intravenously every 12 h or the equivalent with renal adjustment. The remaining 14.4% (76) were treated at an off-label dose of 600 mg intravenously every 8 h or equivalent. The median duration of ceftaroline therapy during hospitalization was 6 days (IQR, 4 to 9 days), and 29.2% (154) of patients were given another antimicrobial in combination with ceftaroline; 42% (64/154) received metronidazole and 42% (65/154) another antistaphylococcal agent. Seventy percent (371/527) were given an antimicrobial to continue treatment for outpatient management; 49% (180/371) were continued on treatment with ceftaroline. Within the S. aureus BSI subpopulation, 33.1% (44/133) were treated with off-label dosing. The median duration of ceftaroline therapy during hospitalization was 9 days (IQR, 4 to 16 days), and 30.8% of patients (41/133) were given another antimicrobial in combination with ceftaroline for S. aureus BSI. The most common antimicrobial agent that was administered concomitantly with ceftaroline was metronidazole. There were 71.4% of patients (95/133) that were given antibiotics as outpatients. Of these, 51.6% (49/95) were given ceftaroline as outpatient treatment for their S. aureus BSI.

FIG 1.

Rationale for the use of ceftaroline by prescriber.

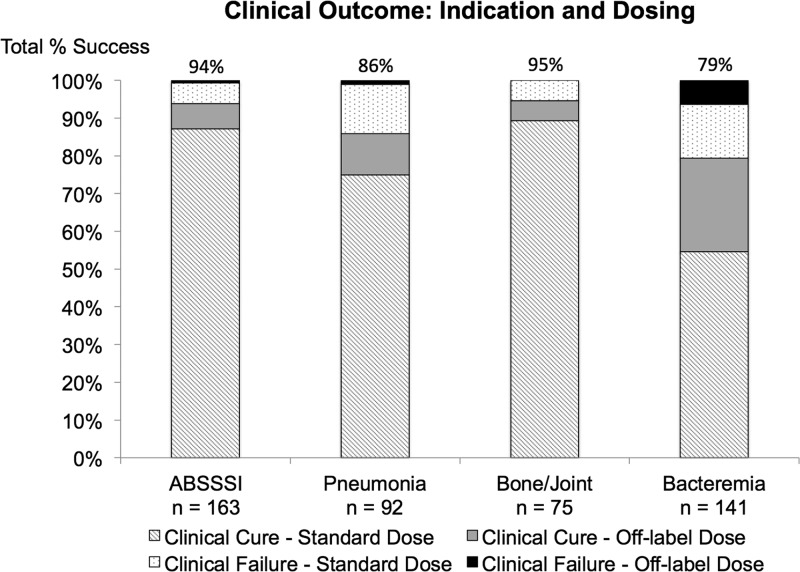

There were 484 (91.8%) clinically evaluable patients at the end of ceftaroline therapy. Overall, 88% (426) of these were categorized as clinical success for the treatment of their infection with ceftaroline therapy. Stratification of clinical success and failure by ceftaroline dosing and classification of the infection is described in Fig. 2. The median hospital length of stay was 12 days (IQR, 7 to 21 days), and the median ICU length of stay was 8 days (IQR, 4 to 17 days). Mortality during hospitalization was 7.6% (40/527). Bacteremia and pneumonia had the highest mortality rate; 14.2% (21/148) and 13.1% (13/99), respectively. A thirty-day follow-up was available for 307 patients (58.3%); the 30-day all-cause mortality was 15.5% (47/307), and the 30-day readmission rate for the same infection was 9.1% (28/307). The bone and joint infection was the most common infection associated with 30-day readmission, 11.5% (9/78). Among patients with S. aureus BSI (of which 123/133 [92.5%] were MRSA), 129/133 (97.0%) S. aureus BSI were clinically evaluable; of these, 101/129 (78.3%) had clinical success with ceftaroline. Those with concomitant S. aureus infective endocarditis and pneumonia were found to have the highest frequency of clinical failure (IE, 10/33, 30.3%; pneumonia, 8/29, 27.6%) and mortality (8/35, 22.9%; 6/30, 20%). Within the patients with S. aureus BSI, 120/133 (90.2%) were microbiologically evaluable; of these, 90.8% (109/120) had microbiological success.

FIG 2.

Clinical outcomes stratified by ceftaroline dosing and indication for clinically evaluable patients. For ABSSSI, 142/151 patients (94.0%) had clinical success by standard dose and 11/12 (91.7%) had clinical success by off-label dose; for pneumonia, 69/81 (85.2%) had clinical success by standard dose and 10/11 (90.9%) had clinical success by off-label dose; for bone and joint, 67/71 (94.4%) had clinical success by standard dose and 4/4 (100.0%) had clinical success by off-label dose; for bacteremia, 77/97 (79.4%) had clinical success by standard dose and 35/44 (79.5%) had clinical success by off-label dose.

Forty-one of 527 patients (7.8%) experienced an adverse reaction (Table 2). The median duration from time of initiation of ceftaroline to the onset of adverse reaction was 6 days (IQR, 4 to 13 days) with a range of 3 to 49 days. Of the patients who received off-label dose, 13/76 (17.1%) experienced an adverse reaction. There were five people that were treated with ceftaroline for longer than 49 days during hospitalization and for whom no adverse reactions were observed. (See Table S2 in the supplemental material for additional descriptive analyses of infection subsets.)

TABLE 2.

Adverse events documented by the primary team

| Adverse event | No. of patients (%)a (n = 527) |

|---|---|

| Diarrhea ± nausea | 5 (0.9)* |

| Vomiting ± nausea | 3 (0.6) |

| Nausea | 1 (0.2) |

| Constipation | 1 (0.2)* |

| Rash (erythematous or maculopapular) | 5 (0.9)*** |

| Renal failure | 6 (1.1)*** |

| Acute interstitial nephritis | 1 (0.2) |

| Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea | 3 (0.6) |

| Hypokalemia | 2 (0.4)* |

| Hyperkalemia | 1 (0.2) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 1 (0.2)* |

| Elevated transaminases and anemia | 1 (0.2) |

| Headache | 1 (0.2) |

| Seizures | 1 (0.2) |

| Chest pain | 1 (0.2)* |

| Fevers | 1 (0.2) |

| Leukopenia | 1 (0.2)* |

| Allergic reaction to ceftaroline | 1 (0.2) |

| Nonsusceptibility to ceftaroline | 4 (0.8)* |

| VRE bacteremia | 1 (0.2) |

Asterisks (*) indicate that a patient case was receiving off-label dose when the adverse reaction occurred; the number of asterisks corresponds to the frequency of cases with off-label dosing of ceftaroline.

DISCUSSION

The results of this large observational retrospective analysis provide preliminary clinical experience with the effectiveness and safety of ceftaroline for various types of infections not responding to other antibiotics. Of interest, approximately 50% of the patients were switched to ceftaroline due to disease progression on prior antibiotic treatment. Therefore, the data presented here may offer some insight into the utility of ceftaroline for the treatment of infections not responding to other antibiotics. Our study's clinical success frequency of 88% (426/484) was similar to the pooled clinical cure from prior trials (89.6%). This was despite our study population having a higher prevalence of comorbid conditions, MRSA infections, and critical illness, as well as a predominance of off-label indications (e.g., complicated bacteremia). Overall, we experienced a low proportion of adverse events within our data. Compared to the pooled phase III trials, our number of adverse events was lower; however, due to the retrospective nature of our data, we are limited to what was available in the medical records (9–12).

Approximately 80% of patients in this cohort received another antimicrobial prior to the use of ceftaroline for the treatment of infection, most commonly vancomycin. This is of interest since vancomycin failure has been previously correlated with switch to an alternative therapy due to disease progression (24, 25). The rationale for switching from vancomycin to another antimicrobial may also be due to a variety of problems associated with the use of this agent, including the development of nonsusceptibility and risk of adverse reactions such as nephrotoxicity (19, 26, 27). Vancomycin therapy has become more challenging since the publication of the consensus guidelines that advocate more-aggressive dosing and therapeutic monitoring (28). Alternative agents such as daptomycin and linezolid have also had some challenges, including treatment failure and the emergence of resistance, especially in the situation of salvage therapy. This may have also accounted for some use of ceftaroline in our patient population (4–6), as ceftaroline has demonstrated in vitro activity against these resistant pathogens (29, 30).

In our patient population, ceftaroline was dosed more frequently (e.g., every 8 h) in 75 (14%) of the patients in our analysis. Providing a more frequent dosing such as administration every 8 h will provide a higher target attainment (%T>MIC) as observed in an in vitro model against several MRSA isolates (31). Since the majority of these patients received ceftaroline as salvage therapy, one may propose that this dosing scheme was prescribed due to failure of prior antibiotics and worsening of infection, as has been described previously (13, 14). Combination therapy with ceftaroline was also observed in our patient population. The most frequent coadministered agent was metronidazole to expand coverage to obligate anaerobic organisms in mixed infections such as diabetic foot. Ceftaroline has limited in vitro activity against most anaerobic pathogens from the respiratory tract and those potentially associated with skin infections except for Bacteroides spp. (not including Bacteroides fragilis) and beta-lactamase-producing Prevotella isolates (32). Ceftaroline was also used in combination with other antistaphylococcal agents (e.g., daptomycin), mostly seen in BSI cases. The MRSA guidelines have suggested that a combination of a beta-lactam with vancomycin or daptomycin may be an alternative for managing severe MRSA infections, especially a high-inoculum infection such as infective endocarditis (19). This combination of ceftaroline and daptomycin has been evaluated previously in an in vitro model and in a case report where ceftaroline was used as salvage therapy in conjunction with daptomycin for daptomycin-nonsusceptible S. aureus endocarditis (29, 30).

In this study, ceftaroline was most often used to treat S. aureus infections, especially S. aureus causing BSI. A previous report from Ho and colleagues described 6 cases of MRSA infection in which therapy was switched from vancomycin and/or daptomycin to ceftaroline (13). We observed a similar pattern of use among cases of S. aureus BSI, in which ceftaroline was prescribed after an average of 6 days of vancomycin or daptomycin. However, ceftaroline was not prescribed “early” for S. aureus BSI as documented by the Murray et al. study (33), in which daptomycin was prescribed after a median of 1.7 days of initial vancomycin. Instead, our data were consistent with those of Moore and colleagues, whose median duration of initial vancomycin therapy was 5 days (IQR, 3 to 9) prior to the switch to daptomycin (34). The clinical (78%) and microbiological (91%) success rates observed in S. aureus BSI were similar to that reported with vancomycin and daptomycin for patients with S. aureus BSI in previous clinical trials (34, 35). Furthermore, the duration of bacteremia calculated from the first day of antistaphylococcal therapy was 6 days, or 2.5 days from the start of ceftaroline. As expected, concomitant endocarditis or pneumonia along with S. aureus BSI was associated with the highest mortality rates, similar to what has been previously described in the literature for these infections (35–37).

Our large observational study incorporates a diverse population of patients across the United States; however, by its retrospective nature this study does have some limitations. The study design is descriptive, and we are not able to make direct inference to other comparator agents (e.g., vancomycin or daptomycin) for MRSA infections. In addition, the 30-day follow-up may be considered too short for evaluating the readmission outcome; therefore, a longer duration for assessment may be needed to fully capture the potential for relapse, recurrence, and readmission for infections requiring long durations of therapy (e.g., bloodstream infections or bone and joints infections) (19, 38). Further, the retrospective nature of our study design prevents us from establishing the true rationale for ceftaroline use. In addition, patterns for ceftaroline use may not be generalizable to all populations; however, the large nature of this study sample should improve its external validity.

In conclusion, this observational case series evaluation suggests that ceftaroline is favorable for various types of off-label indications, including bloodstream infections. Ceftaroline was also well tolerated, with low frequencies of adverse events. A longer duration of ceftaroline therapy is still warranted to fully evaluate its tolerability. The use of frequent dosing, 600 mg intravenously every 8 h, or combination therapy may have potential in the treatment of severe infections and deserves further investigations, especially in patients with bloodstream infections. Although our observational data appear promising, they should be validated with appropriately designed clinical studies before ceftaroline can be recommended for widespread use in such off-label situations as bone and joint infections and bloodstream infections.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

No financial support was received for the conduct of this study.

We acknowledge Christina K. Wong and Abdalhamid M. Lagnf (Wayne State University) for assistance with screening and data collection.

Conflicts of interests: A.M.C. received grant support from Cubist, Forest, and the Michigan Department of Community Health. S.L.D. received grant support from Cubist and Forest and served as a consultant for Forest, Durata, Premier, and Pfizer. D.A.G. received grant support from Astellas and Cubist, served as a consultant with Forest, Cubist, Rempex, and Merck, and served on the speaker's bureau for Astellas and Merck. K.S.K. received grant support from Forest, served as a consultant for Forest, and served on the speaker's bureau for Forest. R.P.M. served on the speaker's bureau for Cubist. J.M.P. received grant support from Forest, served as a consultant for Cubist, and served on the speaker's bureau for Pfizer and Forest. M.J.R. received grant support from Cubist, Forest, Cerexa, Trius, the National Institutes of Health, and the Michigan Department of Community Health, served as a consultant for Durata, Trius, Cubist, Forest, Cepheid, and Theravance, and served on the speaker's bureau for Cubist, Forest, and Novartis. All other authors declare that they have no potential conflict of interests.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 18 February 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02371-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boucher HW, Talbot GH, Bradley JS, Edwards JE, Gilbert D, Rice LB, Scheld M, Spellberg B, Bartlett J. 2009. Bad bugs, no drugs: no ESKAPE! An update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48:1–12. 10.1086/595011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Hal SJ, Paterson DL. 2011. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the significance of heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:405–410. 10.1128/AAC.01133-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khatib R, Jose J, Musta A, Sharma M, Fakih MG, Johnson LB, Riederer K, Shemes S. 2011. Relevance of vancomycin-intermediate susceptibility and heteroresistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:1594–1599. 10.1093/jac/dkr169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelley PG, Gao W, Ward PB, Howden BP. 2011. Daptomycin non-susceptibility in vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (VISA) and heterogeneous-VISA (hVISA): implications for therapy after vancomycin treatment failure. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:1057–1060. 10.1093/jac/dkr066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joson J, Grover C, Downer C, Pujar T, Heidari A. 2011. Successful treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus mitral valve endocarditis with sequential linezolid and telavancin monotherapy following daptomycin failure. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:2186–2188. 10.1093/jac/dkr234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruiz ME, Guerrero IC, Tuazon CU. 2002. Endocarditis caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: treatment failure with linezolid. Clin. Infect. Dis. 35:1018–1020. 10.1086/342698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2010. The 10 x '20 Initiative: pursuing a global commitment to develop 10 new antibacterial drugs by 2020. Clin. Infect. Dis. 50:1081–1083. 10.1086/652237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forest Laboratories, Inc. July 2013. Telfaro (ceftaroline fosamil). Package information. Forest Laboratories, Inc., St. Louis, MO [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corey GR, Wilcox MH, Talbot GH, Thye D, Friedland D, Baculik T, CANVAS 1 investigators 2010. CANVAS 1: the first phase III, randomized, double-blind study evaluating ceftaroline fosamil for the treatment of patients with complicated skin and skin structure infections. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65(Suppl 4):iv41–51. 10.1093/jac/dkq254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilcox MH, Corey GR, Talbot GH, Thye D, Friedland D, Baculik T, CANVAS 2 investigators 2010. CANVAS 2: the second phase III, randomized, double-blind study evaluating ceftaroline fosamil for the treatment of patients with complicated skin and skin structure infections. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65(Suppl 4):iv53–iv65. 10.1093/jac/dkq255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.File TM, Jr, Low DE, Eckburg PB, Talbot GH, Friedland HD, Lee J, Llorens L, Critchley IA, Thye DA, FOCUS 1 investigators. 2011. FOCUS 1: a randomized, double-blinded, multicentre, phase III trial of the efficacy and safety of ceftaroline fosamil versus ceftriaxone in community-acquired pneumonia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66(Suppl 3):iii19–32. 10.1093/jac/dkr096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Low DE, File TM, Jr, Eckburg PB, Talbot GH, David Friedland H, Lee J, Llorens L, Critchley IA, Thye DA, FOCUS 2 investigators 2011. FOCUS 2: a randomized, double-blinded, multicentre, phase III trial of the efficacy and safety of ceftaroline fosamil versus ceftriaxone in community-acquired pneumonia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66(Suppl 3):iii33–44. 10.1093/jac/dkr097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ho TT, Cadena J, Childs LM, Gonzalez-Velez M, Lewis JS., II 2012. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia and endocarditis treated with ceftaroline salvage therapy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67:1267–1270. 10.1093/jac/dks006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin JC, Aung G, Thomas A, Jahng M, Johns S, Fierer J. 2013. The use of ceftaroline fosamil in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis and deep-seated MRSA infections: a retrospective case series of 10 patients. J. Infect. Chemother. 19:42–49. 10.1007/s10156-012-0449-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. 1985. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit. Care Med. 13:818–829. 10.1097/00003246-198510000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. 1987. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 40:373–383. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li JS, Sexton DJ, Mick N, Nettles R, Fowler VG, Jr, Ryan T, Bashore T, Corey GR. 2000. Proposed modifications to the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 30:633–638. 10.1086/313753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lew DP, Waldvogel FA. 2004. Osteomyelitis. Lancet 364:369–379. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16727-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, Daum RS, Fridkin SK, Gorwitz RJ, Kaplan SL, Karchmer AW, Levine DP, Murray BE, Rybak JM, Talan DA, Chambers HF, Infectious Diseases Society of America 2011. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children. Clin. Infect. Dis. 52:e18–e55. 10.1093/cid/ciq146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walsh TR, Bolmstrom A, Qwarnstrom A, Ho P, Wootton M, Howe RA, MacGowan AP, Diekema D. 2001. Evaluation of current methods for detection of staphylococci with reduced susceptibility to glycopeptides. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2439–2444. 10.1128/JCM.39.7.2439-2444.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wootton M, Howe RA, Hillman R, Walsh TR, Bennett PM, MacGowan AP. 2001. A modified population analysis profile (PAP) method to detect hetero-resistance to vancomycin in Staphylococcus aureus in a UK hospital. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 47:399–403. 10.1093/jac/47.4.399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2013. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 23rd informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S23. CLSI, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. 2009. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 42:377–381. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Casapao AM, Leonard SN, Davis SL, Lodise TP, Patel N, Goff DA, Laplante KL, Potoski BA, Rybak MJ. 2013. Clinical outcomes in patients with heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (hVISA) bloodstream infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:4252–4259. 10.1128/AAC.00380-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kopp BJ, Nix DE, Armstrong EP. 2004. Clinical and economic analysis of methicillin-susceptible and -resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Ann. Pharmacother. 38:1377–1382. 10.1345/aph.1E028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Hal SJ, Lodise TP, Paterson DL. 2012. The clinical significance of vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration in Staphylococcus aureus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 54:755–771. 10.1093/cid/cir935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Hal SJ, Paterson DL, Lodise TP. 2013. Systematic review and meta-analysis of vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity associated with dosing schedules that maintain troughs between 15 and 20 milligrams per liter. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:734–744. 10.1128/AAC.01568-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis SL, Scheetz MH, Bosso JA, Goff DA, Rybak MJ. 29 July 2013. Adherence to the 2009 consensus guidelines for vancomycin dosing and monitoring practices: a cross-sectional survey of U.S. hospitals. Pharmacotherapy 33:1256–1263. 10.1002/phar.1327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rose WE, Schulz LT, Andes D, Striker R, Berti AD, Hutson PR, Shukla SK. 2012. Addition of ceftaroline to daptomycin after emergence of daptomycin-nonsusceptible Staphylococcus aureus during therapy improves antibacterial activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:5296–5302. 10.1128/AAC.00797-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Werth BJ, Sakoulas G, Rose WE, Pogliano J, Tewhey R, Rybak MJ. 2013. Ceftaroline increases membrane binding and enhances the activity of daptomycin against daptomycin-nonsusceptible vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus in a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:66–73. 10.1128/AAC.01586-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vidaillac C, Leonard SN, Rybak MJ. 2009. In vitro activity of ceftaroline against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus in a hollow fiber model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:4712–4717. 10.1128/AAC.00636-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Citron DM, Tyrrell KL, Merriam CV, Goldstein EJ. 2010. In vitro activity of ceftaroline against 623 diverse strains of anaerobic bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:1627–1632. 10.1128/AAC.01788-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murray KP, Zhao JJ, Davis SL, Kullar R, Kaye KS, Lephart P, Rybak MJ. 2013. Early use of daptomycin versus vancomycin for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia with vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration >1 mg/L: a matched cohort study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 56:1562–1569. 10.1093/cid/cit112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moore CL, Osaki-Kiyan P, Haque NZ, Perri MB, Donabedian S, Zervos MJ. 2012. Daptomycin versus vancomycin for bloodstream infections due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with a high vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration: a case-control study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 54:51–58. 10.1093/cid/cir764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fowler VG, Jr, Boucher HW, Corey GR, Abrutyn E, Karchmer AW, Rupp ME, Levine DP, Chambers HF, Tally FP, Vigliani GA, Cabell CH, Link AS, DeMeyer I, Filler SG, Zervos M, Cook P, Parsonnet J, Bernstein JM, Price CS, Forrest GN, Fatkenheuer G, Gareca M, Rehm SJ, Brodt HR, Tice A, Cosgrove SE. 2006. Daptomycin versus standard therapy for bacteremia and endocarditis caused by Staphylococcus aureus. N. Engl. J. Med. 355:653–665. 10.1056/NEJMoa053783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holmes NE, Turnidge JD, Munckhof WJ, Robinson JO, Korman TM, O'Sullivan MV, Anderson TL, Roberts SA, Gao W, Christiansen KJ, Coombs GW, Johnson PD, Howden BP. 2011. Antibiotic choice may not explain poorer outcomes in patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and high vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentrations. J. Infect. Dis. 204:340–347. 10.1093/infdis/jir270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zahar JR, Clec'h C, Tafflet M, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Jamali S, Mourvillier B, De Lassence A, Descorps-Declere A, Adrie C, Costa de Beauregard MA, Azoulay E, Schwebel C, Timsit JF. 2005. Is methicillin resistance associated with a worse prognosis in Staphylococcus aureus ventilator-associated pneumonia? Clin. Infect. Dis. 41:1224–1231. 10.1086/496923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lipsky BA, Berendt AR, Cornia PB, Pile JC, Peters EJ, Armstrong DG, Deery HG, Embil JM, Joseph WS, Karchmer AW, Pinzur MS, Senneville E, Infectious Diseases Society of America 2012. 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of diabetic foot infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 54:e132–e173. 10.1093/cid/cis346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.