Abstract

The apicomplexan parasites Cryptosporidium parvum and Cryptosporidium hominis are major etiologic agents of human cryptosporidiosis. The infection is typically self-limited in immunocompetent adults, but it can cause chronic fulminant diarrhea in immunocompromised patients and malnutrition and stunting in children. Nitazoxanide, the current standard of care for cryptosporidiosis, is only partially efficacious for children and is no more effective than a placebo for AIDS patients. Unfortunately, financial obstacles to drug discovery for diseases that disproportionately affect low-income countries and technical limitations associated with studies of Cryptosporidium biology impede the development of better drugs for treating cryptosporidiosis. Using a cell-based high-throughput screen, we queried the Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV) Open Access Malaria Box for activity against C. parvum. We identified 3 novel chemical series derived from the quinolin-8-ol, allopurinol-based, and 2,4-diamino-quinazoline chemical scaffolds that exhibited submicromolar potency against C. parvum. Potency was conserved in a subset of compounds from each scaffold with varied physicochemical properties, and two of the scaffolds identified exhibit more rapid inhibition of C. parvum growth than nitazoxanide, making them excellent candidates for further development. The 2,4-diamino-quinazoline and allopurinol-based compounds were also potent growth inhibitors of the related apicomplexan parasite Toxoplasma gondii, and a good correlation was observed in the relative activities of the compounds in the allopurinol-based series against T. gondii and C. parvum. Taken together, these data illustrate the utility of the Open Access Malaria Box as a source of both potential leads for drug development and chemical probes to elucidate basic biological processes in C. parvum and other apicomplexan parasites.

INTRODUCTION

Cryptosporidiosis is a disease of the gastrointestinal tract most commonly caused in humans by the intracellular apicomplexan parasites Cryptosporidium parvum and Cryptosporidium hominis (1). While the disease is a significant cause of self-limited diarrhea in immunocompetent individuals (2, 3) who may be exposed to parasites through contaminated municipal (4) and recreational water (5) supplies or through occupational exposures (6), the burden of cryptosporidiosis is even more substantial in immunocompromised and pediatric populations. Immunodeficient individuals, including AIDS patients and patients maintained on immunosuppressive regimens following organ transplantation, risk developing chronic, fulminant, and sometimes fatal disease (2). Diarrhea is also a leading cause of death in children <5 years of age (7), and the recent Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS) identified Cryptosporidium as a major cause of life-threatening diarrhea during the first 2 years of life (8). Moreover, cryptosporidiosis has been associated with malnutrition and persistent deficits in development (8–10) in this population. While Cryptosporidium infections constitute a significant etiology of diarrhea cases in the developed world, concurrent factors, including poor sanitation, malnutrition, and high rates of HIV infection with limited access to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), place the highest burden of disease on the developing world (11, 12).

The ideal drug for treating cryptosporidiosis would be inexpensive, require a minimal dosing schedule, and be available as an orally administered agent that is safe and efficacious in children and immunocompromised patients of all ages. While oral administration is desirable, it is unclear if the optimal anticryptosporidial agent should be absorbed systemically or retained in the intestinal lumen. The tendency of immunodeficient patients to develop uncontrolled Cryptosporidium infections suggests that an effective chemotherapeutic should result in rapid clearance of the parasite with minimal reliance on host immune function. Unfortunately, despite the significant morbidity and mortality associated with cryptosporidiosis, no such therapy exists. Nitazoxanide (NTZ), the current standard of care, is only partially effective at treating cryptosporidiosis in immunocompetent adults and children, and it is no more effective than a placebo in AIDS patients who suffer from the disease (13).

Despite the pressing need for new therapies, private pharmaceutical companies are typically unwilling to make the large resource investments (14) that are needed to develop novel therapies for diseases, like cryptosporidiosis, which disproportionately affect poor countries (15). In an effort to assuage the costs associated with research and development and ultimately engage the pharmaceutical sector, public-private partnerships, like the Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV), have been established. These partnerships have been instrumental in the development of novel antimalarial agents, such as the widely used pediatric formulation of Coartem Dispersible (artemether-lumefantrine) (16). Building on these successes, the MMV recently compiled the Open Access Malaria Box, a collection of 400 compounds selected from >19,000 structurally unique molecules that were shown to have activity against the erythrocytic stage of Plasmodium falciparum in 3 large phenotypic high-throughput screening (HTS) campaigns undertaken by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) (17), the Genomics Institute of the Novartis Research Foundation (GNF) (18), and St. Jude Children's Research Hospital (19). The collection is intended to provide starting points for hit-to-lead drug discovery campaigns and facilitate a better understanding of parasite and host biology in order to identify druggable targets and pathways for P. falciparum and other medically important pathogens (20). Additionally, the Open Access Malaria Box was assembled from commercially available compounds, which facilitates the sourcing of compounds and their near neighbors for efficient confirmation of the activities and explorations of structure-activity relationships (SAR).

Our group recently developed a cell-based HTS assay for C. parvum, which measures the growth of parasites within intestinal epithelial cells. We used this assay to screen a library of drug-repurposing candidates, demonstrating its utility for identifying drugs for follow-up testing and for generating insights into the basic biological processes of this genetically intractable parasite (21). Although C. parvum and C. hominis exhibit genetic divergence from other apicomplexan parasites, including the notable absence of potentially promising drug targets (e.g., the apicoplast), a number of other pathways representing potentially druggable targets are conserved between apicomplexan protozoa (22, 23). For example, bioinformatic analysis has revealed the conservation of calcium-mediated pathways across multiple apicomplexans (24), and the cross-reactivity of inhibitors of calcium-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs) has been demonstrated in vitro against C. parvum and Toxoplasma gondii (25), underscoring a potential role for the repurposing of drug screening hits between Apicomplexa.

In this study, we utilized our assay to query the Open Access Malaria Box for compounds with potential activity against C. parvum. Through a combination of high-throughput screening and confirmatory assays, SAR studies, and additional in vitro follow-up, we identified three unique chemical scaffolds as promising hits for further development as novel therapies for cryptosporidiosis. This work constitutes the first application of the Open Access Malaria Box to Cryptosporidium and serves to illustrate the utility of this resource as a rich source of potential screening hits and biological probes for non-Plasmodium applications.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental compounds.

The MMV Open Access Malaria Box (20) was diluted to a final concentration of 1.67 mM, arrayed into the center 308 wells of V-bottom polypropylene 384-well source plates (Whatman), and stored at −80°C. The source plates were warmed to 37°C and briefly centrifuged prior to use. A 384 solid pin Multi-Blot replicator tool (V&P Scientific) was used to transfer approximately 70 nl of the tested compound to the assay plate, for a final concentration of approximately 2.3 μM. The controls on each compound source plate included wells containing dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) only (vehicle) and NTZ to provide a final assay concentration of 6.6 μM (the approximate 90% inhibitory concentration [IC90]). Select pure compounds were purchased from commercial sources (Fig. 1 and 2), and near-neighbor molecules for 2,4-diamino-quinazoline and allopurinol-based SAR studies were purchased from Princeton Biomolecules (Langhorne, PA) and Life Chemicals (Ontario, Canada), respectively.

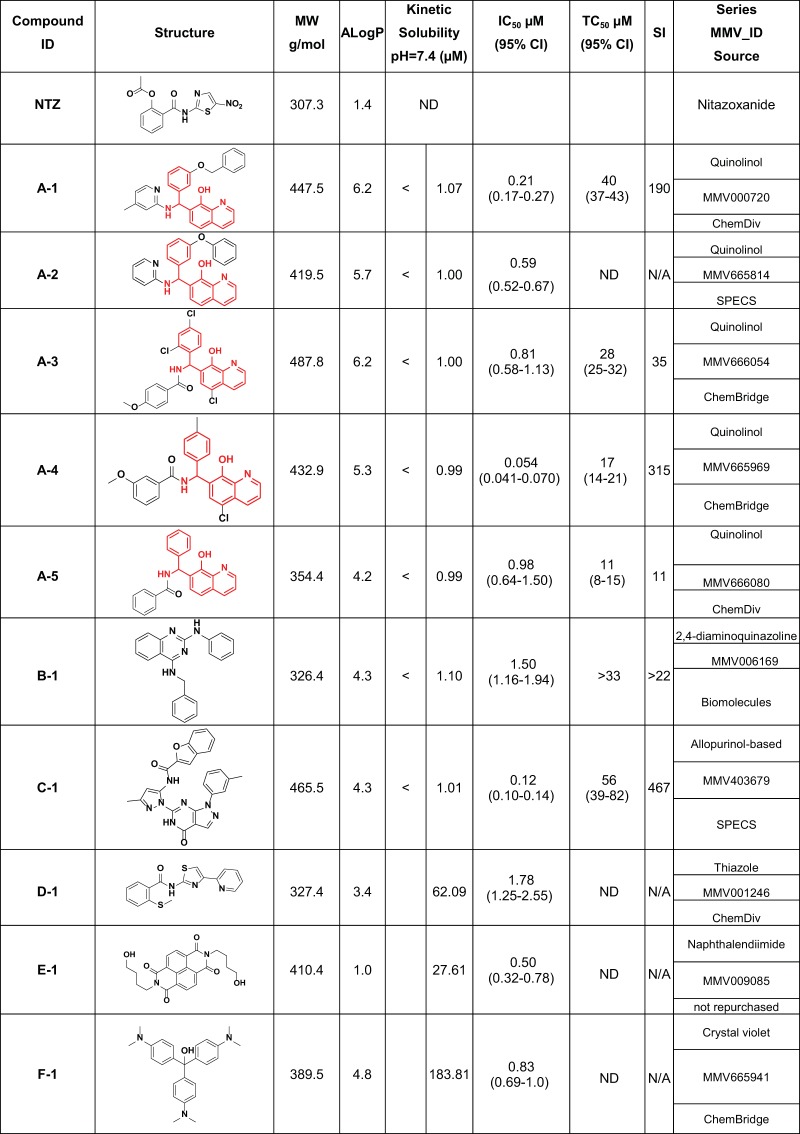

FIG 1.

Open Access Malaria Box screening hits with confirmed activity. MMV identifiers (IDs) and structures (converted from SMILES notation to structures using ACD/ChemSketch version 12.01) were provided by the MMV as part of the supporting information for the Open Access Malaria Box. The commercial source indicates the vendor from whom compounds were purchased for follow-up testing. Compound E-1 (MMV009085) was recovered from the MMV Malaria Box and was not purchased for follow-up (as indicated in the Series MMV_ID source and the comment column in Fig. 2). IC50s were determined by combining data from at least two biological replicates of dose-response experiments generated using a repurchased compound (except for E-1, for which the IC50s are from a single experiment using a cherry-picked compound). The common quinolin-8-ol chemical scaffold is highlighted in red for compounds A-1 to A-5.

FIG 2.

A-6 (MMV666022) and its enantiomers exhibit different activities against C. parvum. During in vitro follow-up, the quinolin-8-ol A-6 (MMV666022) was purchased and its IC50 against C. parvum determined. The compound has a chiral center (identified by the asterisk), and its two enantiomers were separated by chiral high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (see the supplemental material). The two enantiomers were found to vary in potency by almost a log. The IC50s are a combination of data from at least two biological replicates. The AlogP and molecular weight (MW) data are provided in the supporting information for the Open Access Malaria Box.

Cryptosporidium growth assays.

C. parvum oocysts (Iowa strain) (Bunch Grass Farms, Deary, ID) stored in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 1,000 IU/ml penicillin and 1 mg/ml streptomycin were prepared for use by treatment with 10 mM HCl (37°C, 10 min), followed by 2 mM sodium taurocholate (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS with Ca2+ and Mg2+ (16°C, 10 min) in order to stimulate excystation (26). The high-throughput screen was carried out as previously described (21) by inoculating >90% confluent human ileocecal adenocarcinoma (HCT-8) cells (ATCC) with ∼5.5 × 103 primed oocysts per well. The experimental compounds or DMSO (vehicle) were added 3 h after infection, and the cells were incubated for 48 h. For experiments evaluating the minimum effective exposure times, the medium was removed from the wells at the time points indicated and replaced with growth medium with 0.25% DMSO, which was incubated for the remainder of a 72-h period (approximately 4 to 5 doubling times [21]).

Sample preparation for microscopy was conducted as previously described (21). After being washed and fixed, the cells were probed with a mixture of biotinylated Vicia villosa lectin (VVL) (26) (0.67 μg/ml) (Vector Laboratories) and streptavidin-conjugated Alexa Fluor 568 (1.33 μg/ml) (Invitrogen) diluted in 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA)-PBS with 0.1% Tween 20 for 1 h at 37°C to label vegetative forms of C. parvum, and the nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33258. Imaging was performed using a Nikon Eclipse TI2000 epifluorescence microscope with a motorized stage and an EXi Blue digital camera (QImaging, Surrey, British Columbia, Canada); NIS-Elements Advanced Research software (Nikon USA, Melville, NY) was used to direct the acquisition of a three-by-three 20× field photo of the center of each well (covering approximately 13% of the surface area of each well). The images were exported as .tif files into ImageJ and analyzed by using the batch process function to execute previously validated macros to enumerate nuclei and parasites (21).

Compounds that exhibited ≥80% inhibition in at least one screening replicate were recovered from the source plates, diluted in DMSO, and further diluted into growth medium with 20% bovine serum immediately prior to being added to the assay plates to generate 10-point dose-response curves (0.002 to 5 μM) in order to determine a preliminary 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50). Once activity was confirmed, the compounds were prioritized based on selectivity over a cell toxicity assay (selectivity index [SI], >10), existing information regarding the efficacy and/or mechanism of action, and perceived metabolic liabilities. The purchased compounds were used to generate more complete dose-response curves around the preliminary IC50.

Cell toxicity assay.

HCT-8 cells were grown to confluence in 384-well plates. The growth medium was removed and replaced with fresh medium containing experimental compounds and incubated for an additional 48 h, at which point the medium was discarded from all wells. The outer 76 wells of each plate were trypsinized (to provide blank wells), and fresh medium was added to all wells. The CellTiter AQueous assay (Promega) was then used to assess cell viability, according to the manufacturer's instructions. The plates were incubated for 70 min, and absorbance was read at 490 nm with a PowerWave microplate reader (BioTek).

Data handling and analysis.

The ImageJ outputs were imported into Microsoft Excel for data organization and analysis. The percent inhibition compared to the DMSO controls was determined to facilitate the combination of data from individual biological replicates, and GraphPad Prism version 6.00 was used to generate dose-response curves (see below). Vortex version 2011.09.11589 (Dotmatics Limited) was used for figure construction.

To generate dose-response curves, the parasite counts were averaged for each infected well treated with a different concentration of the experimental compound (n = 11 wells), minus the average signal from 3 uninfected wells treated with the corresponding concentration of drug. The percent inhibition values from at least two biological replicates were combined to generate dose-response curves in GraphPad Prism. IC50s were calculated as per the following equation, with the bottom and top values constrained to 0 and 100, respectively: Y = Bottom + (Top − Bottom)/(1 + 10LogIC50 − X × Hill slope), where Y is the percent inhibition, X is the drug concentration, and Hill slope is the largest absolute value of the slope of the curve.

To generate the cell toxicity curves, the average absorbances of the 76 blank wells were subtracted from all experimental values on each plate, and the absorbance of each compound-treated well was normalized to the average absorbance of the DMSO-only wells to yield the percentage of DMSO-only values. These were calculated for each treatment group (n = 14 wells per compound concentration), and the data from two biological replicates were combined to generate dose-response curves in GraphPad Prism. The 50% toxic concentration (TC50) values were calculated using the equation above, with the bottom and top constraints set to 0 and 100, respectively.

YFP-based T. gondii growth assay.

The growth of yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-expressing T. gondii strain RH was monitored, as previously described (27), with the following modifications. The parasites and cells were cultured in HyClone DMEM/high modified medium without phenol red (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and supplemented with 1 or 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). A total of 5 × 103 human foreskin fibroblasts (in culture medium supplemented with 10% FBS) were seeded onto each well of a black/clear 384-well tissue culture-treated Special Optics plate (BD Falcon) and grown at 37°C in 5% CO2. Upon reaching 100% confluence, the medium was replaced with 30 μl of culture medium supplemented with 1% FBS. YFP parasites were harvested by syringe release, passed through a 3-μm Nuclepore filter (Whatman), pelleted (1,100 × g), and resuspended to a final concentration of 1 × 105 parasites/ml. Two thousand parasites were added to each well to begin the assay, followed immediately by the addition of test compounds serially diluted from DMSO stocks in culture medium supplemented with 1% FBS. The final DMSO concentrations ranged from 0.018 to 0.12%. The plates were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2, and fluorescence was read daily from the bottom of the plate with the lid in place using a Synergy 2 microplate reader (BioTek) set to a sensitivity of 60, with an excitation filter of 485/20 and an emission filter of 528/20. Pyrimethamine was used as a positive control in all assays. The assay was run for 7 days, and IC50 curves were calculated as above using fluorescence measurements from day 5, the time at which the control (DMSO treatment) parasites consistently reached maximal growth.

RESULTS

HTS of MMV Open Access Malaria Box.

The MMV Open Access Malaria Box was screened in two separate biological replicates for activity against C. parvum. The screening data (presented as the percent inhibition) for both replicates are available for all 400 compounds in Table S1 in the supplemental material, along with descriptive data provided by the MMV, including ChEMBL (see https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl/) identifiers, original GlaxoSmithKline/St Jude/Novartis compound identifiers, canonical simplified molecular-input line-entry system (SMILES) representation of molecules, locations in Open Access Malaria Box plates, classification as drug- or probe-like, in vitro activity against P. falciparum, and some in silico physicochemical parameters (for a complete explanation, see Table S1 in reference 20).

The final concentration of NTZ (positive control for in vitro inhibition of C. parvum) used in the source plates was calculated to achieve 90% inhibition (IC90, 6.6 μM) following the transfer of the compounds to the assay plate. However, the average inhibition rates for the wells treated with NTZ were only 53% and 50% for plates 1 and 2, respectively, suggesting that the pin transfer was slightly less efficient than originally intended. With this in mind, we chose to pursue further any compound that exhibited ≥80% inhibition in at least one biological replicate, resulting in a list of 19 compounds. We then reviewed the images associated with these compounds to assess the integrity of the host cell monolayers. The monolayer was absent or severely damaged for eight of the compounds (either as a result of compound toxicity or mechanical disruption during sample processing); these were considered to be false positives and were excluded from further analysis. Next, we recovered (“cherry picked”) the other 11 compounds from the source plates and used them to generate 10-point dose-response curves. Ten of the 11 cherry-picked compounds were confirmed to have inhibitory activity against C. parvum, and 9 of these 10 compounds were repurchased for final determination of IC50 values (Fig. 1). Overall, our screening pipeline confirmed anti-Cryptosporidium activity for 2.5% (10/400) of the Open Access Malaria Box compounds.

Confirmatory dose-response curves, host cell toxicity, and SAR series.

The 10 active compounds identified in the screen were composed of 5 compounds (A-1 to A-5; Fig. 1) containing a common chemical scaffold [7-(amino(phenyl)methyl)quinolin-8-ol], as well as five other unrelated molecules (B-1, C-1, D-1, E-1, and F-1; Fig. 1). The presence of near-neighbor molecules in our original screening hits provided confidence in the anti-Cryptosporidium activity of the quinolin-8-ol scaffold, prompting us to pursue further these five molecules. The other five singleton compounds were prioritized for follow-up based on: (i) existing in vitro or in vivo data regarding their potency and efficacy in other applications, probable mechanism of action, or pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic profiles; (ii) evaluation of their chemical structure for drug-like potential and metabolic liabilities; and (iii) availability of near neighbors for SAR studies. Based on these criteria, two additional chemical scaffolds, represented by the molecules B-1 (Fig. 1; 2,4-diamino-quinazoline scaffold) and C-1 (Fig. 1; allopurinol-based scaffold), were selected for follow-up.

Quinolin-8-ol series.

The IC50s for the 5 quinolin-8-ol compounds identified by our screening pipeline ranged from 0.054 μM to 0.98 μM, with >11-fold selectivity [TC50(HCT-8)/IC50(C. parvum)] (compounds A-1 to A-5; Fig. 1), and the most potent compound in this series, A-4 (IC50, 0.054 μM), also exhibited the highest selectivity index (SI, 315). Further review of the contents of the Open Access Malaria Box revealed a 6th member of the quinolin-8-ol series (A-6; Fig. 2) that was not identified by our HTS (the compound exhibited 53.7% and 11.6% inhibition for screening replicates 1 and 2, respectively). This compound was purchased, and a dose-response curve was generated, revealing an IC50 of 0.24 μM. The structures of A-series compounds each contain a chiral center at the benzylic position. A chiral separation was performed for molecule A-6 (see Supplemental Data 1 in the supplemental material), and dose-response curves were generated for the (−) and (+) enantiomers (molecules [−]-A6 and [+]-A-6, respectively; Fig. 2). Interestingly, the two enantiomers showed an approximately 10-fold difference in potency (Fig. 2), suggesting an important role for stereochemistry in the mechanism of action of the molecules. In general, the compounds in the quinolin-8-ol series occupy the lipophilic end of the drug-like space, and they exhibit variable potency and other physicochemical parameters, including size, partition coefficient (XlogP), and topological polar surface area (tPSA) (summarized in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The nonsubstituted quinolin-8-ol compound, A-5, already shows a micromolar IC50 against C. parvum and might be considered the minimal requirement for activity, although a more-in-depth SAR series would prove useful. Interestingly, modifying the substitution pattern on the aromatic rings may substantially tune the potency, as depicted by compounds A-3 and A-6. Finally, based on our experience with molecule A-6, chiral separation of other series members may result in the identification of stereoisomers with enhanced potency.

2,4-Diamino-quinazoline series.

Confirmatory dose-response curves for B-1 revealed an IC50 of 1.50 μM and a selectivity index of >22. Twenty-six near-neighbor compounds were purchased, and dose-response curves were generated. The potency ranged from 0.44 μM to undetectable at the concentrations tested (>10 μM). TC50 values were determined for the seven most potent compounds, and SIs were >20 for all compounds tested (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). In addition to potency, molecular size, XlogP, and tPSA varied across the chemical series (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The importance of the nitrogen atom in position 2 in this chemical scaffold is of particular interest. With a similar lipophilicity and substitution pattern in position 4, it seems that the potency is dramatically influenced by the substituents on the aromatic ring at position 2, as shown by compounds B-4 and B-13. More interesting is that this same aromatic ring can be replaced by an aliphatic cyclopentyl ring, allowing for a similar activity level as that of the initial hit (B-1), while making this compound (B-5) more drug-like, as it reduces the number of aromatic rings in the molecule. Finally, initial attempts to include more polar compounds resulted in a loss of activity (see Fig. S2), but this needs further investigation, as the choice of commercially available analogues was limited.

Allopurinol-based series.

The activity of C-1 was confirmed, as the compound exhibited an IC50 of 0.12 μM and an SI of 467. Forty-one commercially available analogs were purchased for SAR studies, and all compounds inhibited C. parvum growth at submicromolar concentrations, with IC50s ranging from 0.04 μM to 0.69 μM. TC50 values were determined for the 9 most potent compounds, and selectivity indices ranged from ∼156 to >1,500 (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). The relationship between potency and other physicochemical parameters is illustrated in Fig. S3 in the supplemental material. Starting from an already potent but large and lipophilic hit (C-1), this early SAR suggests that potency can be maintained while reducing the molecular weight via the removal of the acyl group, yielding compound C-35, with an IC50 of 0.19 μM. The amide portion of the scaffold is nonetheless useful to modulate the polarity, as depicted with C-26, the most polar molecule, with a tPSA of 139 Å2. Finally appending a cyclopropyl amide allowed the formation of C-4, a very potent (IC50, 0.046 μM) and drug-like molecule (molecular mass, 389 g/mol; tPSA, 106 A2; XlogP, 2.93). As mentioned earlier, the parameters that guide in vivo efficacy are not yet determined, and this series shows potential in being able to modulate the physicochemical properties while maintaining overall potency.

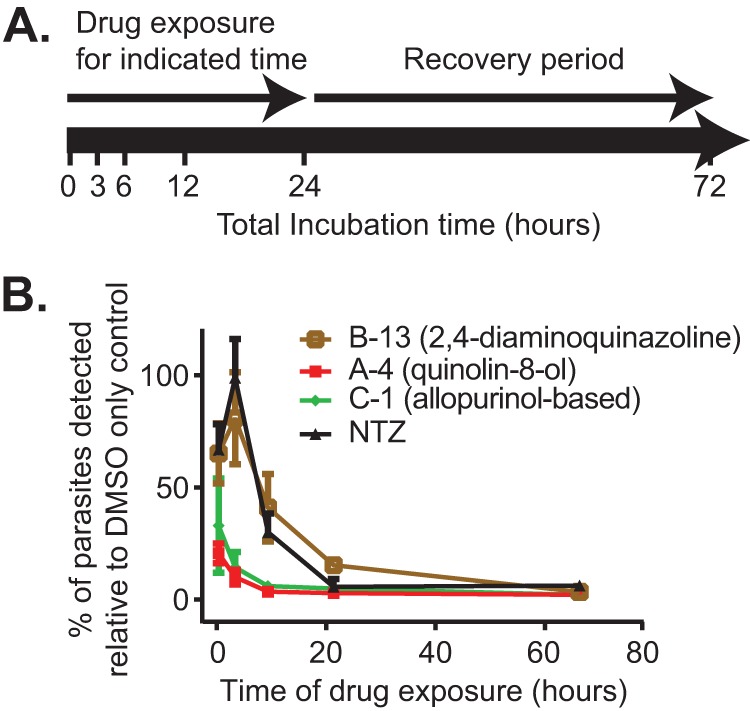

Determination of minimum effective exposure time.

The ability to rapidly inhibit Cryptosporidium growth is an important factor for prioritizing hits for further follow-up and comparing their activity profiles to that of NTZ. By modifying our screening assay, we were able to gain some insights into the minimum duration of drug exposure required for each of our experimental compounds to exhibit their maximal effect. Briefly, host cell monolayers were infected, and the IC90 dose of NTZ or a representative compound from each novel scaffold (quinolin-8-ol, 2,4-diamino-quinazoline, or allopurinol-based) was added 3 h after infection. The medium was then removed from the compound-treated wells (and from matched control wells treated with DMSO) after 3, 6, 12, or 24 h of drug exposure, replaced with growth medium containing DMSO, and incubated at 37°C for the duration of the 72-h culture period (Fig. 3A). The monolayers were then fixed, stained, and imaged as described in Materials and Methods. The data were normalized to the corresponding DMSO-only controls. The parasites treated with NTZ for <6 h recovered fully, and some recovery was observed for treatments of as long as 24 h (Fig. 3B), indicating that viable parasites persisted despite treatment with the drug. Compound B-13 (representing the 2,4,diamino-quinazoline series; Fig. 3B) exhibited inhibition kinetics similar to those of NTZ. Compounds C-1 (representative of the allopurinol-based series; Fig. 3B) and A-4 (representative of the quinolin-8-ol series, Fig. 3B) both showed faster inhibition, as evidenced by the lack of parasite growth recovery following a shorter treatment window. These data suggest that allopurinol-based and quinolin-8-ol compounds act more rapidly against C. parvum than NTZ.

FIG 3.

Determination of minimum effective exposure time. (A) Schematic describing the experimental design. Beginning 3 h after infection, the infected cells were treated with experimental compound or 0.25% DMSO (vehicle) for 3, 6, 12, or 24 h, at which point the growth medium containing the compound was replaced with compound containing 0.25% DMSO for the duration of the 72-h culture period. The infected cells treated with experimental compounds for 69 h provided a control for the anti-Cryptosporidium activity of the compounds. The cells were then fixed, stained, and imaged. (B) Parasites treated with nitazoxanide (NTZ) or 2,4-diamino-quinazoline (B-13) for 6 h exhibited full recovery, and parasites treated with these compounds exhibited partial recovery despite treatment for up to 24 h. Parasites treated with representative quinolin-8-ol (A-4) and allopurinol-based (C-1) compounds showed no parasite recovery following a shorter treatment interval. n = 3; error bars represent the standard deviation.

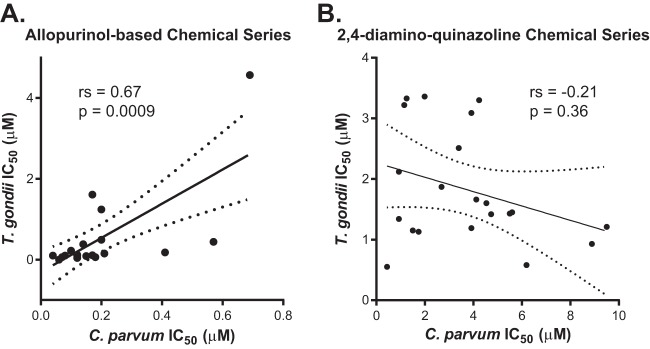

Activity against T. gondii.

The fact that hits from previous screens against P. falciparum were active against C. parvum in our screen supports the idea that druggable targets may be conserved between these two parasites. T. gondii, another medically important apicomplexan, is amenable to genetic manipulation and has been used as a model organism to study Cryptosporidium (28). We therefore tested whether members of the newly identified chemical series were also active against T. gondii to determine if the conservation of druggable pathways might extend to other apicomplexan parasites. Compounds of the quinolin-8-ol series exhibited various levels of cytotoxicity against the human foreskin fibroblast host cells used in the assay, making comparisons of the activities of these compounds difficult. In contrast, we found that members of the 2,4-diamino-quinazoline and allopurinol-based series inhibited T. gondii growth with no evidence of cytotoxicity (see Tables S2 and 3, respectively, in the supplemental material; also, data not shown), facilitating the comparison of IC50s from these two series against C. parvum and T. gondii (Fig. 4). Compounds with IC50s outside the range assayed (≥5 μM for the allopurinol-based series and ≥10 μM for the 2,4-diamino-quinazolines) were excluded from the analysis. There was a good correlation between the relative potency of the allopurinol-based series (Spearman's rank correlation coefficient [ρ] = 0.67) against T. gondii and C. parvum, suggesting that these compounds may act on a conserved target. In contrast, there was no significant correlation among compounds in the 2,4-diamino-quinazoline series (ρ = −0.21).

FIG 4.

Correlation of the relative potencies of allopurinol-based and 2,4-diamino-quinazoline compounds against C. parvum and T. gondii. (A) IC50s against C. parvum and T. gondii were plotted for 21 compounds from the allopurinol-based chemical series (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). One compound exhibited an IC50 against C. parvum and T. gondii that was outside the assayed range (i.e., >5 μM) and was excluded from the analysis. The Spearman rank correlation coefficient (rs) was determined to be 0.67 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.32 to 0.86; P = 0.0009), suggesting good correlation between the compound activities. (B) IC50s against C. parvum and T. gondii were plotted for 21 compounds in the 2,4-diamino-quinazoline chemical series (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Five compounds exhibited IC50s against C. parvum and/or T. gondii that were outside the assayed range (i.e., >10 μM) and were excluded from the analysis. There appeared to be no correlation between the compound activities (rs = −0.21; 95% CI, −0.60 to 0.26; P = 0.36).

DISCUSSION

We utilized a previously validated cell-based high-throughput screening assay (21) to query the 400 compounds in the MMV Open Access Malaria Box for inhibitory activity against C. parvum. While the repurposing of hits from other screens differs from the repurposing of existing drugs, in that the development of a drug still requires pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic optimization, preclinical efficacy studies in animals, and resource-intensive phase I through III clinical trials, it might expedite the discovery of compounds that inhibit relevant biological targets. Additionally, many of these compounds were previously characterized, and this information may prove to be extremely useful in the later development steps, particularly target deconvolution.

Our screen demonstrated anti-Cryptosporidium activity for 2.5% of the Open Access Malaria Box compounds, which is on par with the results of our previous screen of a drug-repurposing library (3.3% hit rate) (21). Given the likelihood of conserved targets between C. parvum and P. falciparum, it is a little surprising that our hit rate was not higher. This may be a result of nonconserved targets between the parasites or differences in host cell and/or parasite permeability to compounds. More likely, this is a result of inefficient pin transfer of the test compounds (as evidenced by less inhibition than was expected by the NTZ control), resulting in a lower sensitivity for the assay at the cutoff for follow-up testing employed in our screening pipeline. As is necessary for any screening approach, our hit definition was set to identify a workable number of compounds for follow-up, and despite the relatively modest sensitivity of the assay, it enabled the identification of compounds with a high likelihood of confirmed activity when cherry-picked for follow-up testing (10 of 11 compounds [91%]). However, it should be noted that additional Open Access Malaria Box compounds with potentially useful anti-Cryptosporidium activities likely remain unidentified, and follow-up testing on additional compounds that inhibited C. parvum growth at levels short of our hit definition might be fruitful.

The Open Access Malaria Box is composed of 200 drug-like compounds (i.e., compliant with Lipinski's rules [29]) as well as 200 probe-like molecules that exhibit more physicochemical diversity (20). However, the observation that many existing antimicrobial drugs do not adhere to Lipinski's rules (30) has prompted calls to expand the chemical space explored in drug development projects (30–32). Moreover, the ideal pharmacokinetic profile for optimizing drug efficacy against Cryptosporidium is not entirely apparent, and it may be affected by the need to optimize drug exposure within the epithelium of the small intestine and by unique features of the Cryptosporidium parasitophorous vacuole (33, 34). Consequently, in order to facilitate wider chemical diversity, we chose not to include the “drug-like” classification as a criterion for hit prioritization. This strategy allowed us to capitalize on the fact that the Malaria Box intentionally includes near-neighbor compounds (many of which are classified as probe-like) (20), and it facilitated the discovery of the quinolin-8-ol series as a potent chemical scaffold (IC50 range, 0.054 to 0.98 μM). In addition to the quinolin-8-ol series, our discovery pipeline revealed two other novel scaffolds (allopurinol-based and 2,4-diamino-quinazoline series) with potent activity against C. parvum.

SAR studies of all three series revealed near-neighbor compounds with increased activity. The potency of the quinolin-8-ol and allopurinol-based series varied by >1 log (IC50, 0.054 μM to 0.98 μM and IC50, 0.04 μM to 0.69 μM, respectively), while the 2,4-diamino-quinazoline series exhibited the widest range in potency (IC50, 0.44 μM to 9.50 μM) and included 5 molecules that showed no activity at the concentrations tested. The three series include a wide range of tPSA values, which may provide insights into the relative importance of passive membrane diffusion of the molecules. Additionally, the allopurinol-based series exhibits a lower LogP than the quinolin-8-ol or 2,4-diamino-quinazolines. This difference may be useful in the future for examining the impact of tissue distribution of the compounds on in vivo efficacy. A comparison of these parameters with the IC50s (see Fig. S1 to S3 in the supplemental material) shows that potency is retained despite various physicochemical properties; this underscores the potential utility of these various compounds as tools for improving our understanding of the ideal product profile for a drug to treat cryptosporidiosis. An important next step in assessing these chemical series will be conducting animal studies for in vivo validation, while simultaneously evaluating the pharmacologic properties of the variants of each scaffold to enable correlations of efficacy with oral absorption and other characteristics.

Given the risk of fulminant infection in immunocompromised patients, rapid action is a highly desirable quality for an anti-Cryptosporidium therapy. The full inhibition of parasite growth was not achieved by NTZ until 24 h of drug treatment, suggesting that C. parvum parasites do not die during 24 h of exposure to NTZ. In contrast, as little as 6 h of treatment with compounds C-1 (allopurinol-based) and A-4 (quinolin-8-ol) achieved the maximal level of parasite inhibition. While not direct evidence of a parasiticidal mechanism of action, these data demonstrate that the rate of action of the allopurinol-based and quinolin-8-ol series is considerably faster than that of NTZ, making these compounds attractive candidates for further development.

Compounds that have been highly optimized for the inhibition of P. falciparum were intentionally excluded from the Malaria Box in an effort to increase the utility of the collection for drug development campaigns targeting other microbes (20). In addition to providing the original rationale to screen the collection against C. parvum, the potential for cross-reactivity of these compounds among other apicomplexans prompted us to examine the activities of the three scaffolds we identified against T. gondii. While several of the quinolin-8-ol compounds tested initially appeared to have selective activity against T. gondii (J. Foderaro and G. Ward, unpublished data), our analysis of this series was complicated by toxicity to the foreskin fibroblast cell line that was observed on the final day of the T. gondii growth assay. The observed toxicity may reflect the different durations of compound exposure for the cell lines employed in the C. parvum and T. gondii assays (2 days versus 7 days, respectively). It is also possible that the transformed HCT-8 cell line used for the Cryptosporidium assay is relatively resistant to the quinolin-8-ol compounds by virtue of the expression of an ABC transporter that confers drug resistance (as is common in malignant cell lines), or by another mechanism. Thus, although the selectivity of these compounds for C. parvum ranges from moderate (11-fold for A-5) to excellent (315-fold for A-4), host toxicity may limit the development of the quinolin-8-ol series. On the other hand, the allopurinol and 2,4-diamino-quinazoline scaffolds were selectively active against T. gondii, and a good correlation between the relative potencies of the allopurinol-based compounds suggests that the target may be conserved between the different parasites. Poor correlations between the compounds of the 2,4,-diaminoquinazoline series may be suggestive of parasite divergence or result from technical differences in the growth assays used to determine the IC50s. For example, it is important to note that IC50s were calculated for C. parvum following 2 days of drug exposure but after 5 days of drug exposure for the T. gondii assay. Differences between the permeability of the C. parvum parasitophorous vacuole and to that of the T. gondii parasitophorous vacuole may also result in differences in drug delivery to the target in each parasite and underscore the physicochemical differences between the compounds. Knowledge of the differences in susceptibility between C. parvum and T. gondii may be particularly useful, as functional Cryptosporidium proteins can be expressed in the genetically tractable T. gondii, providing a relevant model organism to facilitate target identification for novel anti-Cryptosporidium compounds (35).

Knowledge of the mechanisms of action for these chemical series may provide new insights into Cryptosporidium biology and also aid in drug development (e.g., by enabling target-based approaches). Thus, a potential advantage of screening the Malaria Box or any other collection of relatively well-characterized compounds is the possibility to capitalize on this knowledge for target identification. We used the chemical structure search function of the Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) SciFinder database (https://scifinder.cas.org) to query the existing literature and patents for information on analogs of the quinolin-8-ol, 2,4-diamino-quinazoline, or allopurinol-based scaffolds. The 8-hydroxyquinoline moiety is a known chelator of divalent metals, and previous reports indicate potential roles for quinolin-8-ol derivatives in the treatment of both cancers and infections (36–39). Since the stereoisomers of compound A-6 differ in potency against C. parvum by nearly 10-fold, they may affect parasite growth by inhibiting the function of a specific metal-binding protein. However, a specific protein target for the quinolin-8-ol series in either Plasmodium or Cryptosporidium is not known.

Structure-based searches of the 2,4-diamino-quinazoline scaffold identified the near-neighbor molecule, N2N4-dibenzylquinazoline-2,4-diamine (DBeQ, purchased and tested as OSSL_324373) (see Table S2 in the supplemental material), which is a potent, specific, and reversible inhibitor of p97, an ATPase associated with diverse cellular activities (AAA ATPase; also called CDC48) that is implicated in protein trafficking and the degradation of incorrectly folded proteins (40). A previously reported bioinformatic analysis concluded that p97 functions in the P. falciparum endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-associated degradation (ERAD) pathway, a streamlined protein quality-control pathway that is critical for the control of ER stress. Furthermore, pharmacologic interference with different proteins of the ERAD pathway (including p97 with DBeQ) in P. falciparum inhibits parasite growth (41). The aligned protein sequences of P. falciparum p97 (GenBank accession no. XP_966179.2) and its C. parvum homolog (GenBank accession no. XP_627893.1) are 76% identical, suggesting that DBeQ and other compounds based on the 2,4-diamino-quinazoline chemical scaffold might inhibit C. parvum and T. gondii growth by a similar mechanism. Similarly, the C. parvum homolog and T. gondii homolog (GenBank accession no. XP_002365921.1) are 82% identical. As noted above, differences in the relative potency of the different 2,4-diamino-quinazoline compounds against P. falciparum and the poor correlation of the potency of this series against C. parvum and T. gondii might reflect technical differences in the assays or differences in the access of the compounds to the target. However, the mechanism of action might also be different in the three parasites, and further studies will be required to distinguish these possibilities.

Structure-based searches using the allopurinol-based scaffold were less informative, and the basis of activity of this series of compounds against P. falciparum is unknown. Allopurinol is an inhibitor of the host enzyme xanthine oxidase, which functions in the degradation of purines (42). However, relevant concentrations of allopurinol and its active metabolite, oxypurinol, do not affect C. parvum growth (R. Jumani and C. Huston, unpublished data), so it is likely that the allopurinol-based compounds reported here inhibit C. parvum growth via a target in the parasite or some alternative target in the host cell. It is tempting to speculate that the antiparasitic activities of the allopurinol-based chemicals are related to their similarity to purines, but given the numerous cellular functions of purine-based molecules, a concerted effort will be required for target identification.

In addition to providing a manageable collection of chemically diverse screening molecules for malarial drug development, the creation of the MMV Open Access Malaria Box was intended to be a useful tool for researchers studying other microbes. By screening the Open Access Malaria Box against C. parvum, we identified three novel chemical scaffolds with potent anti-Cryptosporidium activity, demonstrating the utility of the library in drug discovery campaigns for other apicomplexan parasites. The inclusion of near-neighbor compounds proved to be a useful feature of the Malaria Box, as it was extremely helpful in guiding our hit prioritization for follow-up in the case of the quinolin-8-ol scaffold. Additionally, the ease with which near-neighbor compounds can be purchased for singleton compounds in the collection facilitated the identification of two additional chemical series. The ability to easily acquire the compounds needed for robust SAR studies allowed us to identify multiple potent compounds that exhibit a range of physicochemical properties, providing an excellent tool to further elucidate the pharmacokinetic profile of an ideal drug to treat cryptosporidiosis, which is a critical next step in the preclinical development of these chemical scaffolds. Follow-up efforts at target identification are also required and, in some cases, can be guided by prior knowledge of the mechanisms of action of these compounds against P. falciparum.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Nick Westwood and Fanny Tran for helpful discussions.

This work was funded by an MMV challenge grant and NIH grants NIAID R21AI101381 (to C.D.H.) and NIAID R01AI054961 (to G.E.W.). K.B. is supported by NIH grant T32AI0055402-06AI. C.D.H. and K.B. are inventors for a U.S. patent application covering the use of chemical scaffolds described in this study for the treatment of cryptosporidiosis. The purpose of this application is to enable their further development for clinical use, and this did not affect the study design, interpretation of data, or writing of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 24 February 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02641-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Xiao L, Fayer R, Ryan U, Upton SJ. 2004. Cryptosporidium taxonomy: recent advances and implications for public health. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17:72–97. 10.1128/CMR.17.1.72-97.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen XM, Keithly JS, Paya CV, LaRusso NF. 2002. Cryptosporidiosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 346:1723–1731. 10.1056/NEJMra013170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoder JS, Wallace RM, Collier SA, Beach MJ, Hlavsa MC. 2012. Cryptosporidiosis surveillance–United States, 2009–2010. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 61:1–12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mac Kenzie WR, Hoxie NJ, Proctor ME, Gradus MS, Blair KA, Peterson DE, Kazmierczak JJ, Addiss DG, Fox KR, Rose JB, Davis JP. 1994. A massive outbreak in Milwaukee of Cryptosporidium infection transmitted through the public water supply. N. Engl. J. Med. 331:161–167. 10.1056/NEJM199407213310304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hlavsa MC, Roberts VA, Anderson AR, Hill VR, Kahler AM, Orr M, Garrison LE, Hicks LA, Newton A, Hilborn ED, Wade TJ, Beach MJ, Yoder JS. 2011. Surveillance for waterborne disease outbreaks and other health events associated with recreational water—United States, 2007–2008. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 60:1–32 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2012. Outbreak of cryptosporidiosis associated with a firefighting response—Indiana and Michigan, June 2011. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 61:153–156 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Black RE, Cousens S, Johnson HL, Lawn JE, Rudan I, Bassani DG, Jha P, Campbell H, Walker CF, Cibulskis R, Eisele T, Liu L, Mathers C, Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group of WHO and UNICEF 2010. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2008: a systematic analysis. Lancet 375:1969–1987. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60549-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kotloff KL, Nataro JP, Blackwelder WC, Nasrin D, Farag TH, Panchalingam S, Wu Y, Sow SO, Sur D, Breiman RF, Faruque AS, Zaidi AK, Saha D, Alonso PL, Tamboura B, Sanogo D, Onwuchekwa U, Manna B, Ramamurthy T, Kanungo S, Ochieng JB, Omore R, Oundo JO, Hossain A, Das SK, Ahmed S, Qureshi S, Quadri F, Adegbola RA, Antonio M, Hossain MJ, Akinsola A, Mandomando I, Nhampossa T, Acácio S, Biswas K, O'Reilly CE, Mintz ED, Berkeley LY, Muhsen K, Sommerfelt H, Robins-Browne RM, Levine MM. 2013. Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. Lancet 382:209–222. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60844-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guerrant DI, Moore SR, Lima AA, Patrick PD, Schorling JB, Guerrant RL. 1999. Association of early childhood diarrhea and cryptosporidiosis with impaired physical fitness and cognitive function four–seven years later in a poor urban community in northeast Brazil. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 61:707–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macfarlane DE, Horner-Bryce J. 1987. Cryptosporidiosis in well-nourished and malnourished children. Acta Paediatr. Scand. 76:474–477. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1987.tb10502.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Connor RM, Shaffie R, Kang G, Ward HD. 2011. Cryptosporidiosis in patients with HIV/AIDS. AIDS 25:549–560. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283437e88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shirley DA, Moonah SN, Kotloff KL. 2012. Burden of disease from cryptosporidiosis. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 25:555–563. 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328357e569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abubakar I, Aliyu SH, Arumugam C, Hunter PR, Usman NK. 2007. Prevention and treatment of cryptosporidiosis in immunocompromised patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (1):CD004932. 10.1002/14651858.CD004932.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adams CP, Brantner VV. 2006. Estimating the cost of new drug development: is it really $802 million? Health Aff. (Millwood) 25:420–428. 10.1377/hlthaff.25.2.420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reich MR. 2000. The global drug gap. Science 287:1979–1981. 10.1126/science.287.5460.1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdulla S, Sagara I, Borrmann S, D'Alessandro U, González R, Hamel M, Ogutu B, Mårtensson A, Lyimo J, Maiga H, Sasi P, Nahum A, Bassat Q, Juma E, Otieno L, Björkman A, Beck HP, Andriano K, Cousin M, Lefèvre G, Ubben D, Premji Z. 2008. Efficacy and safety of artemether-lumefantrine dispersible tablets compared with crushed commercial tablets in African infants and children with uncomplicated malaria: a randomised, single-blind, multicentre trial. Lancet 372:1819–1827. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61492-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gamo FJ, Sanz LM, Vidal J, de Cozar C, Alvarez E, Lavandera JL, Vanderwall DE, Green DV, Kumar V, Hasan S, Brown JR, Peishoff CE, Cardon LR, Garcia-Bustos JF. 2010. Thousands of chemical starting points for antimalarial lead identification. Nature 465:305–310. 10.1038/nature09107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meister S, Plouffe DM, Kuhen KL, Bonamy GM, Wu T, Barnes SW, Bopp SE, Borboa R, Bright AT, Che J, Cohen S, Dharia NV, Gagaring K, Gettayacamin M, Gordon P, Groessl T, Kato N, Lee MC, McNamara CW, Fidock DA, Nagle A, Nam TG, Richmond W, Roland J, Rottmann M, Zhou B, Froissard P, Glynne RJ, Mazier D, Sattabongkot J, Schultz PG, Tuntland T, Walker JR, Zhou Y, Chatterjee A, Diagana TT, Winzeler EA. 2011. Imaging of Plasmodium liver stages to drive next-generation antimalarial drug discovery. Science 334:1372–1377. 10.1126/science.1211936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guiguemde WA, Shelat AA, Bouck D, Duffy S, Crowther GJ, Davis PH, Smithson DC, Connelly M, Clark J, Zhu F, Jiménez-Díaz MB, Martinez MS, Wilson EB, Tripathi AK, Gut J, Sharlow ER, Bathurst I, El Mazouni F, Fowble JW, Forquer I, McGinley PL, Castro S, Angulo-Barturen I, Ferrer S, Rosenthal PJ, DeRisi JL, Sullivan DJ, Lazo JS, Roos DS, Riscoe MK, Phillips MA, Rathod PK, Van Voorhis WC, Avery VM, Guy RK. 2010. Chemical genetics of Plasmodium falciparum. Nature 465:311–315. 10.1038/nature09099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spangenberg T, Burrows JN, Kowalczyk P, McDonald S, Wells TN, Willis P. 2013. The open access Malaria Box: a drug discovery catalyst for neglected diseases. PLoS One 8:e62906. 10.1371/journal.pone.0062906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bessoff K, Sateriale A, Lee KK, Huston CD. 2013. Drug repurposing screen reveals FDA-approved inhibitors of human HMG-CoA reductase and isoprenoid synthesis that block Cryptosporidium parvum growth. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:1804–1814. 10.1128/AAC.02460-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abrahamsen MS, Templeton TJ, Enomoto S, Abrahante JE, Zhu G, Lancto CA, Deng M, Liu C, Widmer G, Tzipori S, Buck GA, Xu P, Bankier AT, Dear PH, Konfortov BA, Spriggs HF, Iyer L, Anantharaman V, Aravind L, Kapur V. 2004. Complete genome sequence of the apicomplexan, Cryptosporidium parvum. Science 304:441–445. 10.1126/science.1094786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu P, Widmer G, Wang Y, Ozaki LS, Alves JM, Serrano MG, Puiu D, Manque P, Akiyoshi D, Mackey AJ, Pearson WR, Dear PH, Bankier AT, Peterson DL, Abrahamsen MS, Kapur V, Tzipori S, Buck GA. 2004. The genome of Cryptosporidium hominis. Nature 431:1107–1112. 10.1038/nature02977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wernimont AK, Artz JD, Finerty P, Jr, Lin YH, Amani M, Allali-Hassani A, Senisterra G, Vedadi M, Tempel W, Mackenzie F, Chau I, Lourido S, Sibley LD, Hui R. 2010. Structures of apicomplexan calcium-dependent protein kinases reveal mechanism of activation by calcium. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17:596–601. 10.1038/nsmb.1795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphy RC, Ojo KK, Larson ET, Castellanos-Gonzalez A, Perera BG, Keyloun KR, Kim JE, Bhandari JG, Muller NR, Verlinde CL, White AC, Jr, Merritt EA, Van Voorhis WC, Maly DJ. 2010. Discovery of potent and selective inhibitors of calcium-dependent protein kinase 1 (CDPK1) from C. parvum and T. gondii. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 1:331–335. 10.1021/ml100096t [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gut J, Nelson RG. 1999. Cryptosporidium parvum: synchronized excystation in vitro and evaluation of sporozoite infectivity with a new lectin-based assay. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 46:56S–57S [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gubbels MJ, Li C, Striepen B. 2003. High-throughput growth assay for Toxoplasma gondii using yellow fluorescent protein. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:309–316. 10.1128/AAC.47.1.309-316.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Striepen B, Kissinger JC. 2004. Genomics meets transgenics in search of the elusive Cryptosporidium drug target. Trends Parasitol. 20:355–358. 10.1016/j.pt.2004.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. 2001. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 46:3–26. 10.1016/S0169-409X(00)00129-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Payne DJ, Gwynn MN, Holmes DJ, Pompliano DL. 2007. Drugs for bad bugs: confronting the challenges of antibacterial discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 6:29–40. 10.1038/nrd2201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bauer RA, Wurst JM, Tan DS. 2010. Expanding the range of ‘druggable' targets with natural product-based libraries: an academic perspective. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 14:308–314. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keller TH, Shi PY, Wang QY. 2011. Anti-infectives: can cellular screening deliver? Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 15:529–533. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang BQ, Chen XM, LaRusso NF. 2004. Cryptosporidium parvum attachment to and internalization by human biliary epithelia in vitro: a morphologic study. J. Parasitol. 90:212–221. 10.1645/GE-3204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lumb R, Smith K, O'Donoghue PJ, Lanser JA. 1988. Ultrastructure of the attachment of Cryptosporidium sporozoites to tissue culture cells. Parasitol. Res. 74:531–536. 10.1007/BF00531630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Striepen B, White MW, Li C, Guerini MN, Malik SB, Logsdon JM, Jr, Liu C, Abrahamsen MS. 2002. Genetic complementation in apicomplexan parasites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:6304–6309. 10.1073/pnas.092525699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baum EZ, Crespo-Carbone SM, Klinger A, Foleno BD, Turchi I, Macielag M, Bush K. 2007. A MurF inhibitor that disrupts cell wall biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:4420–4426. 10.1128/AAC.00845-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coombs GS, Schmitt AA, Canning CA, Alok A, Low IC, Banerjee N, Kaur S, Utomo V, Jones CM, Pervaiz S, Toone EJ, Virshup DM. 2012. Modulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling and proliferation by a ferrous iron chelator with therapeutic efficacy in genetically engineered mouse models of cancer. Oncogene 31:213–225. 10.1038/onc.2011.228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fraser RS, Creanor J. 1975. The mechanism of inhibition of ribonucleic acid synthesis by 8-hydroxyquinoline and the antibiotic lomofungin. Biochem. J. 147:401–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Phillips JP. 1956. The reactions of 8-quinolinol. Chem. Rev. 56:271–297. 10.1021/cr50008a003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chou TF, Brown SJ, Minond D, Nordin BE, Li K, Jones AC, Chase P, Porubsky PR, Stoltz BM, Schoenen FJ, Patricelli MP, Hodder P, Rosen H, Deshaies RJ. 2011. Reversible inhibitor of p97, DBeQ, impairs both ubiquitin-dependent and autophagic protein clearance pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:4834–4839. 10.1073/pnas.1015312108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harbut MB, Patel BA, Yeung BK, McNamara CW, Bright AT, Ballard J, Supek F, Golde TE, Winzeler EA, Diagana TT, Greenbaum DC. 2012. Targeting the ERAD pathway via inhibition of signal peptide peptidase for antiparasitic therapeutic design. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:21486–21491. 10.1073/pnas.1216016110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Terkeltaub R, Bushinsky DA, Becker MA. 2006. Recent developments in our understanding of the renal basis of hyperuricemia and the development of novel antihyperuricemic therapeutics. Arthritis Res. Ther. 8:S4. 10.1186/ar1909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.