Abstract

Rice false smut caused by Villosiclava virens is an economically important disease of grains worldwide. The genetic diversity of 153 isolates from six fields located in Wuhan (WH), Yichang Wangjia (YCW), Yichang Yaohe (YCY), Huanggang (HG), Yangxin (YX), and Jingzhou (JZ) in Hubei province of China were phylogenetically analyzed to evaluate the influence of environments and rice cultivars on the V. virens populations. Isolates (43) from Wuhan were from two rice cultivars, Wanxian 98 and Huajing 952, while most of the other isolates from fields YCW, YCY, HG, YX, and JZ originated from different rice cultivars with different genetic backgrounds. Genetic diversity of isolates was analyzed using random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) and single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP). The isolates from the same cultivars in Wuhan tended to group together, indicating that the cultivars had an important impact on the fungal population. The 110 isolates from individual fields tended to cluster according to geographical origin. The values of Nei's gene diversity (H) and Shannon's information index (I) showed that the genetic diversity among isolates was higher between than within geographical populations. Furthermore, mean genetic distance between groups (0.006) was higher than mean genetic distance within groups (0.0048) according to MEGA 5.2. The pairwise population fixation index (FST) values also showed significant genetic differentiation between most populations. Higher genetic similarity of isolates from individual fields but different rice cultivars suggested that the geographical factor played a more important role in the selection of V. virens isolates than rice cultivars. This information could be used to improve the management strategy for rice false smut by adjusting the cultivation measures, such as controlling fertilizer, water, and planting density, in the rice field to change the microenvironment.

INTRODUCTION

Rice false smut, caused by Villosiclava virens (anamorph: Ustilaginoidea virens) (1, 2), is an economically important disease of grain around the world. V. virens invades spikelets via the small gap between the lemma and palea (3) and then infects filaments and finally transforms individual infected grains into smut balls (4), which then become covered by powdery dark-green chlamydospores. V. virens reduces grain yield and quality, and the ustiloxin from its chlamydospores is toxic to both humans and animals (5–7).

Rice false smut used to be recognized as a minor disease, because false smut balls (yellowish or greenish) were observed only in the high-yielding rice field. However, it is no longer a minor disease in light of the large-scale cultivation of high-yielding cultivars and the change of rice farming systems (8). Rice false smut occurs in most rice-producing areas of Asia, Africa, the Americas, and Europe, but it causes the most damage in China, Japan, India, and the Philippines (9–12). The disease has caused severe damage in the major rice-growing regions Sichuan, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Hunan, and Hubei of China, where the disease appears to gain in importance each year (13).

Many studies examined the influence of rice cultivar, fertility, and climate on the occurrence of rice false smut disease. Susceptibility of rice cultivars to V. virens varies, for instance, the japonica type is more susceptible than the indica type, and early-maturing cultivars are more resistant than late-maturing cultivars (8, 13, 14). Several studies revealed that too much nitrogen fertilizer increased the occurrence of false smut (13, 15, 16). Some studies also showed that warm weather, low day-night temperature difference, high humidity, and little sunlight favored false smut development (8).

Most studies about false smut disease focused on disease occurrence and prevention, and there are only limited studies on the diversity of V. virens. Molecular markers have been widely used for the identification, taxonomy, evolution, as well as genetic diversity of bacteria, protozoa, fungi, plants, and animals (17–24), such as restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) (25), random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) (26), amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) assays (27), simple sequence repeats (SSR) (28), inter-simple sequence repeats (ISSR) (29, 30), and single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) (31). Several reports on genetic diversity of V. virens have been published in recent years. Zhou et al. investigated V. virens from northern, southern, and central areas of China with RAPD and found that there was no distinct geographical relationship among strains (32). Pan et al. analyzed the V. virens isolates from one rice field in Changping, Beijing, China, by AFLP and found there was no specific interaction between rice cultivars and V. virens (33). Zhou et al. analyzed the genetic diversity of V. virens isolates from northern China using AFLP markers, and results indicated no relationship between isolates and rice cultivars from Beijing and Liaoning province (34). Tan et al. reported that most V. virens strains from different regions of Hunan province were genetically very similar (35). Zhang et al. investigated V. virens from indica rice in Sichuan province and found that isolates from different geographical environments were more similar than isolates from the same rice cultivars (36). Yang et al. assessed the genetic diversity of V. virens from Fujian province with RAPD markers and found there was no obvious correlation between origin and rice cultivars (37). Sun et al. used SNP-rich sequences to evaluate the genetic diversity of 162 V. virens isolates from 15 provinces covering five major rice-growing areas in China, and significant genetic differences between different geographical populations were found (38). Most isolates in these studies came from a very limited number of rice cultivars. In our research, most of the V. virens isolates (except for WH isolates) in individual fields were derived from different rice cultivars with different genetic backgrounds that ensured a high level of host diversity of V. virens isolates in each field, which provided a reliable evaluation for the role of geographic environment and rice cultivar in V. virens population selection.

The objectives of the present study were (i) to analyze the genetic diversity of V. virens isolates collected from single fields of Hubei province based on RAPD and SNP profiles and (ii) to evaluate whether hosts or geographic environments play a key role in the selection of pathogen populations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal isolates and culture conditions.

Forty-three V. virens isolates were collected from two cultivars in an experimental field at Huazhong Agricultural University; 23 (labeled W) were from cultivar Wanxian 98, and 20 (labeled H) were from cultivar Huajing 952. These 43 V. virens isolates were used to evaluate the genetic diversity relative to the cultivar from which they were isolated.

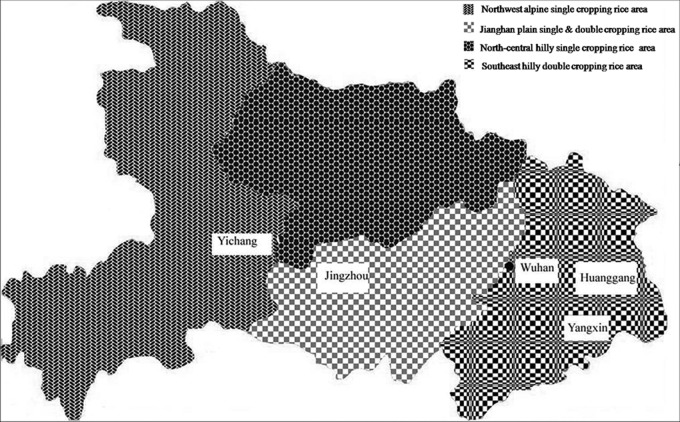

A total of 110 V. virens isolates were collected from 5 fields near the cities of Yichang (YC), Huanggang (HG), Yangxin (YX), and Jingzhou (JZ), Hubei province, China (Table 1). There are two geographically different locations in Yichang city, i.e., Yichang Wangjia (YCW) and Yichang Yaohe (YCY). Hubei province consists of four rice-growing areas characterized by different geographical conditions and climates: the northwest alpine single-cropping rice area, the north-central hilly single-cropping rice area, the southeast hilly double-cropping rice area, and the Jianghan plain single- and double-cropping rice area (Fig. 1). Hubei (except for the alpine area) has a subtropical monsoon climate characterized by high humidity and abundant light, heat, and rainfall. The northwest alpine single-cropping rice area (including Yichang) is complex, with many mountain ranges. Therefore, the temperature variation is substantial, and the temperature limitation allows for only single cropping. The north-central hilly single-cropping rice area has an annual average temperature of 15.3 to 15.9°C, which is suitable for single-season rice production. The southeast hilly double-cropping rice area (including Huanggang, Yangxin, and Wuhan) is located along the Yangtze River. The annual average temperature is 15.7 to 17°C, which is suitable for double-cropping rice. The Jianghan plain single- and double-cropping rice area (including Jingzhou) is the alluvial plain of the Yangtze River and Hanjiang River. The annual average temperature is 15.9 to 16.9°C, which supports single and double cropping. Even for isolates collected in the same growing season, there were substantial differences in weather conditions between these sampling sites. These environmental factors affect the growth of rice and also affect the occurrence of rice false smut. The 110 V. virens isolates were used to explicitly assess the population structure relative to rice cultivar and geographical environment.

TABLE 1.

Villosiclava virens isolates used in this study

| Population | Location | No. of isolates | No. of cultivars | Yr of isolation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WH | Wuhan | 43 | 2 | 2012 |

| YCW | Yichang Wangjia | 16 | 16 | 2010 |

| 12 | 12 | 2011 | ||

| YCY | Yichang Yaohe | 9 | 9 | 2011 |

| YX | Yangxin | 32 | 32 | 2010 |

| JZ | Jingzhou | 8 | 7 | 2010 |

| 13 | 13 | 2011 | ||

| HG | Huanggang | 20 | 17 | 2011 |

| Total | 153 | 96 |

FIG 1.

Characteristics of four rice-growing areas in Hubei province. Yangxin and Huanggang are in the southeast hilly double-cropping rice area, Yichang and Jingzhou are in the northwest alpine single-cropping rice area, and Jianghan is in the plain single- and double-cropping rice areas. The template map, obtained from www.nipic.com (no. 272563773), was modified to show the different rice-cropping areas.

Single-spore isolates were obtained from false smut balls of different cultivars (one isolate per ball) and cultured on potato sucrose agar (PSA) at 28°C. All of the isolates were stored at −80°C in 25% glycerol (long-term storage) and at 4°C on PSA medium (short-term storage).

Extraction of genomic DNA.

Isolates were grown in 50 ml of potato sucrose broth (PSB) for 7 days at 28°C on a 160-rpm orbital shaker. For each isolate, 100 mg of mycelial dry weight was harvested by filtration. Mycelium was ground in liquid nitrogen for total genomic DNA extraction using the EasyPure plant genomic DNA kit (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer's recommendation. The DNA was visualized by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and stored at −20°C for further use.

RAPD analysis.

Out of 116 RAPD primers, 18 generated polymorphisms among tested isolates in preliminary experiments (Table 2). Amplification reactions were performed in a 25-μl reaction volume containing 1 U of Easy Taq DNA polymerase (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China), 1× PCR buffer provided by the manufacturer, 200 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), 0.4 μM primer, and 30 ng of template DNA. Amplification was carried out in a MyCycler thermal cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., CA) programmed for 5 min at 94°C; 40 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 36°C, and 2 min at 72°C; and a final extension of 5 min at 72°C. PCR products were detected in a 1% agarose gel and visualized using a UV transilluminator.

TABLE 2.

Primers for creating RAPD profiles and SNP analysis

| Primer name | Primer sequence (5′→3′) |

|---|---|

| S304 | CCGCTACCGA |

| S341 | CCCGGCATAA |

| S359 | GGACACCACT |

| S372 | TGGCCCTCAC |

| S376 | GAGCGTCGAA |

| S385 | ACGCAGGCAC |

| S395 | AAGAGAGGGG |

| S18 | CCACAGCACT |

| S1397 | GAGCCCGACT |

| SNP-F2 | AGCCCGGACTCGCAGTAC |

| SNP-F3 | GCACTGCCATTGTCTGTG |

| SNP-F4 | TGCCGCCCCGCAAGATCTCT |

| S320 | CCCAGCTAGA |

| S350 | AAGCCCGAGG |

| S368 | GAACACTGGG |

| S374 | CCCGCTACAC |

| S379 | CACAGGCGGA |

| S392 | GGGCGGTACT |

| S399 | GAGTGGTGAC |

| S30 | GTGATCGCAG |

| S1414 | AAGTGCGACC |

| SNP-R2 | CGACTACAGAGACGCTTCGC |

| SNP-R3 | TCTTAGTTTCCCTGTTTTCG |

| SNP-R4 | CGAATAAGCACAAATGCAGT |

Polymorphic bands were scored 1 and 0 for the presence and absence of bands, respectively. The polymorphic data were entered into the software package Numerical Taxonomy Multivariate Analysis System (NTSYS-pc), version 2.10 (Department of Ecology and Evolution, State University of New York) to establish a dendrogram using the unweighted-pair group method using average linkages (UPGMA) algorithm in the SAHN program. The values of genetic diversity, genetic identity, and genetic distance were calculated by the software Popgen 32 (Department of Renewable Resources, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada). The genetic distance data then were imported into the software MEGA 5.2 (39) to construct the phenogram among geographically different groups.

SNP analysis.

Based on genomic sequences of V. virens, three SNP primer pairs, which could amplify SNP-rich regions, were used in this study (Table 2 and Shaojie Li, personal communication). Two of the three SNP-rich genomic regions were the same as those previously reported, but they were obtained with different primers (38). Amplification reactions were performed in a 50-μl reaction volume containing 2.5 U of Easy Taq DNA polymerase (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China), 1× PCR buffer provided by the manufacturer, 200 μM each dNTP, 0.4 μM each primer, and 50 ng of template DNA. Amplification was carried out in a MyCycler thermal cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., CA) with the following profile: 94°C for 3 min; 35 cycles at 94°C for 40 s, 60°C (SNPF2-R2, SNPF4-R4) or 56°C (SNPF3-R3) for 40 s, 72°C for 1 min; and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min.

Sequencing was conducted at Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI; Shenzhen, China) and assembled by DNASTAR software (DNASTAR Inc., Nevada City, CA). The sequences were aligned with the program Clustal W in the software MEGA 5.2. The maximum parsimony (MP) method was used to construct phylogenetic trees. The following settings were used: heuristic search using close neighbor interchange (CNI; level 1) with initial trees generated by random addition (100 repetitions). The genetic distance between groups then was computed by MEGA 5.2, and the dendrogram between geographically different groups based on genetic distance data was constructed.

Population genetic analysis.

The fixation index (FST) is a means of measuring population differentiation and genetic distance. The pairwise FSTs can be used as short-term genetic distances between populations, with the application of a slight transformation to linearize the distance with population divergence time. Here, FST values of pairwise population comparisons were calculated using Arlequin 3.1 (40) based on DNA sequences and RAPD data. Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) tests were performed to assess population variance among and within populations using GenALEx 6.5 (41) on the basis of DNA sequences and RAPD data. Principal coordinate analysis (PCA) was performed to evaluate the genetic differences among isolates within populations, which was carried out by GenALEx 6.5.

RESULTS

Genetic diversity of isolates from the same cultivars in one field.

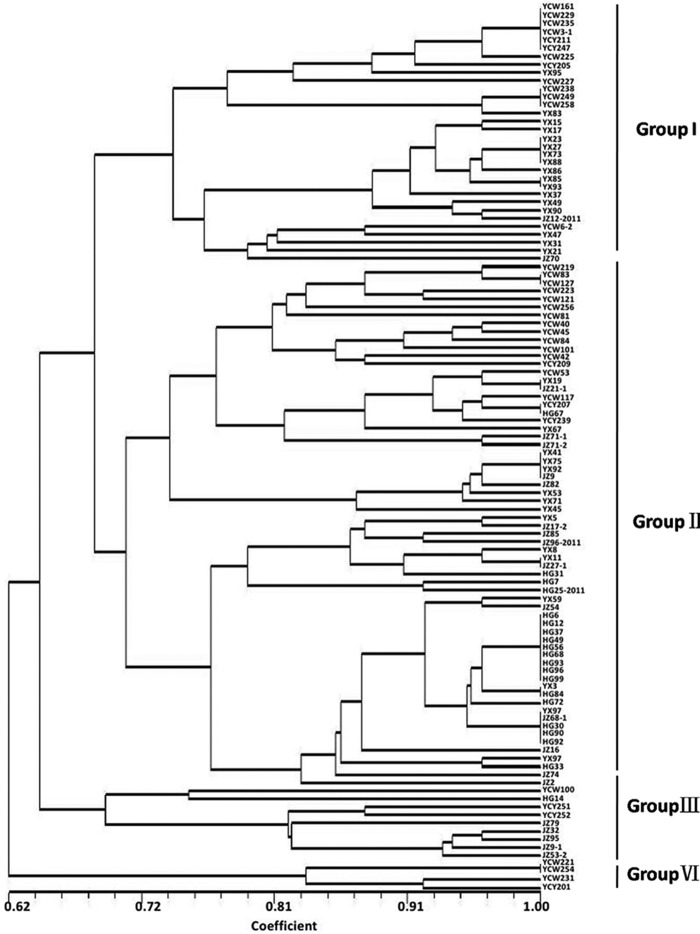

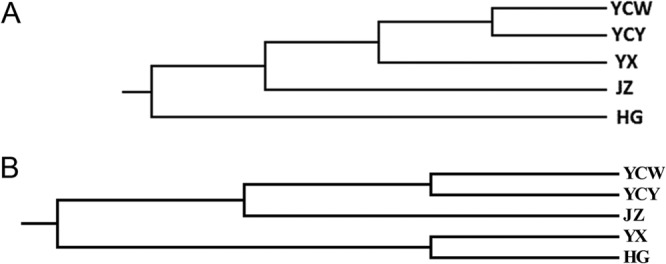

A total of 18 RAPD primers were used to generate 20 unambiguous DNA fragments for analysis. Three highly discriminating genomic sequences (646-, 639-, and 445-bp fragments) were sequenced and aligned for a total of 1,730 nucleotide positions for SNP analysis. Based on RAPD and SNP data, the phylogenetic trees of 43 isolates from the field at Huazhong Agricultural University were constructed. Both methods showed that isolates from the same cultivar tended to group together (Fig. 2). The pairwise FST values (RAPD, 0.36107; SNP, 0.50809) showed significant genetic differentiation when W isolates and H isolates were compared (P < 0.001). These data suggested that rice cultivars have an important impact on the V. virens populations.

FIG 2.

Dendrograms of RAPD and SNP analysis of 43 isolates collected from two rice cultivars (Wanxian 98 and Huajing 952) in one field of Huazhong Agricultural University. Isolates from the same cultivar tended to group together. (A) Dendrogram according to genetic distance by RAPD analysis. With 18 RAPD primers, 20 unambiguous bands were used to score 1 and 0 as presence and absence, respectively. (B) Dendrogram according to genetic distance by SNP analysis. The MP tree was inferred from the 1,730-bp combined DNA sequence data set. The numbers labeled at each node indicate the bootstrap percentages (n = 1000).

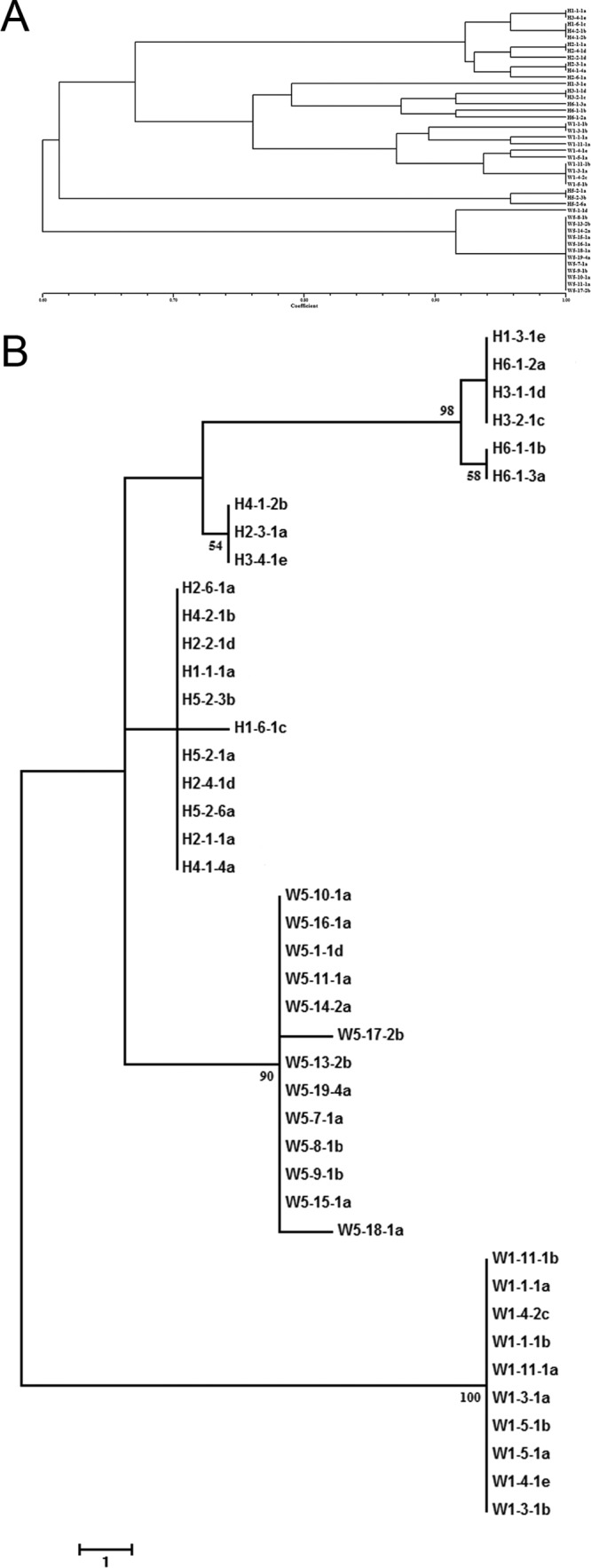

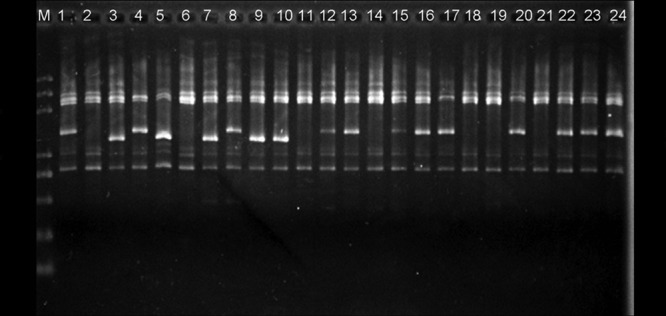

Phylogenetic analysis of 110 isolates based on RAPD markers.

RAPD analyses were carried out with 110 isolates of V. virens from five fields in Hubei province. With 18 RAPD primers, 21 unambiguous bands were scored. Electrophoresis patterns of primer S385 are shown in Fig. 3 as an example. Among these isolates from different fields, two distinct bands were recorded (the 1.3- and 1.5-kb bands; Fig. 3).

FIG 3.

RAPD profiles of 24 Villosiclava virens isolates obtained with primer S385. M, DNA molecule size marker. The largest to smallest bands are 5.0, 3.0, 2.0, 1.0, 0.75, 0.5, 0.25, and 0.1 kb in length. Lanes 1 to 24 represent isolates JZ2, JZ9, JZ12-2011, JZ68-1, JZ71-1, YX15, YX17, YX21, YX37, YX49, YCW53, YCW81, YCW83, YCW117, YCW121, YCY201, YCY205, YCY207, YCY239, YCY247, HG67, HG68, HG93, and HG96, respectively.

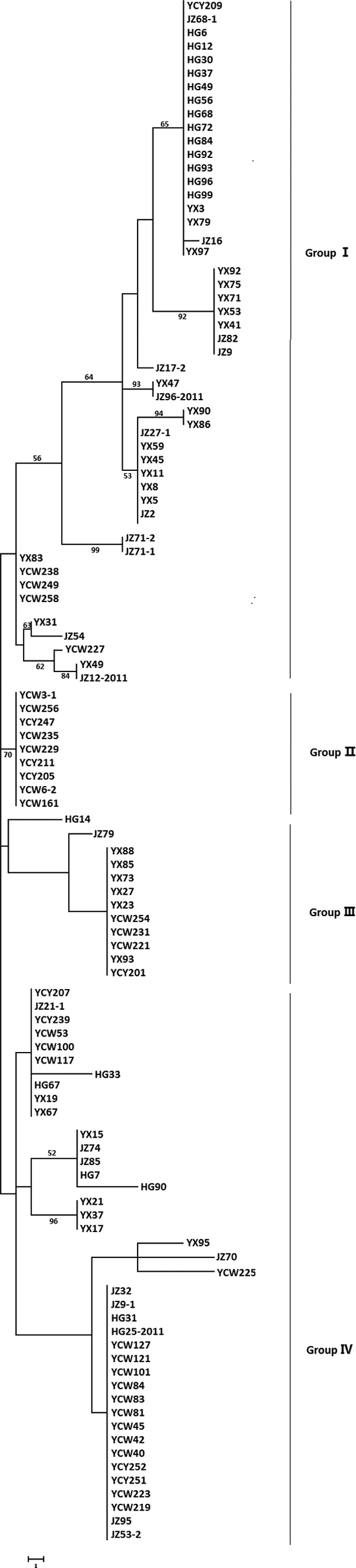

As shown in Fig. 4, most isolates from Huanggang city clustered together, whereas isolates from the other four locations did not. Four genetic groups were divided at a 0.69 genetic distance level: 53.13% of YX isolates were classified into group I, 95% and 66.67% of HG isolates and JZ isolates, respectively, were in group II, and 81.08% of YC isolates were clustered in the combined groups I and II (Fig. 4). The identity of some isolates from the same field but from different rice cultivars reached 100%, such as HG6, HG12, HG37, HG49, HG56, HG68, HG93, HG96, and HG99; YCW161, YCW229, YCW235, and YCW3-1; YX23, YX27, YX73, and YX88, etc. (Fig. 4). On the other hand, the isolates HG12, HG72, HG84, and HG96, obtained from rice cultivar Wanxian 98, showed high similarity, and YCY211 and YCW161 from Wanxian 98 shared 100% identity (Fig. 4). Other isolates from the same rice cultivars were not in the same subgroups (Table 3).

FIG 4.

Dendrogram constructed with the UPGMA clustering method for 110 isolates of V. virens based on 18 RAPD primers. Four groups were divided at 0.69 genetic distance level, and most isolates were grouped in group I and group II. Group I was composed of isolates from Yichang and Yangxin, and group II consisted of Huanggang, Jingzhou, and Yichang isolates.

TABLE 3.

Isolates from the same rice cultivars

| Rice cultivar | Isolate names | Phylogenetic pattern by |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| RAPD analysis | SNP analysis | ||

| Jinyou 718 | YX19, YCW235 | Separate | Separate |

| Shenliangyou 5814 | YCY247, YCW258 | Separate | Separate |

| Benliangyou 639 | YX49, YCW229 | Separate | Separate |

| Tianliangyou 616 | YX53, YCY209 | Separate | Separate |

| Keyou 8377 | YX88, YCY252 | Separate | Separate |

| Deyou 8258 | HG7, YCW45 | Separate | Separate |

| Q you no.8 | YX75, HG67 | Separate | Separate |

| Yixiang 3724 | JZ53-2, JZ9 | Separate | Separate |

| Wanxian 98 | YCY211, YCW161, YCW121 | YCY211 together with YCW161 but separate from YCW121 | YCY211 together with YCW161 but separate from YCW121 |

As shown in Table 4, the percentage of polymorphic loci for all isolates (87.50%) was higher than those for geographical populations, which varied from 58.33% to 83.33%. The Nei's gene diversity (H) and Shannon's information index (I) for all isolates were 0.2713 and 0.4106, and for geographical populations they ranged from 0.1876 to 0.2646 and 0.2813 to 0.3985, respectively. The values of H and I revealed similar tendencies, in that all isolates as a group had higher genetic diversity than isolates of individual geographical populations. Considering that increasing numbers of isolates from the same cultivars can increase the similarity of individual populations, thereby decreasing the variance among isolates in the same fields, the minimum number of isolates from the same cultivars may provide the best assessments of environmental impacts. In the present study, most isolates among individual geographical populations were from different cultivars. The higher similarity among isolates in individual fields (even from different cultivars) indicated that the geographical factor influences populations more than host cultivars.

TABLE 4.

Genetic diversity of isolates from different fields in Hubei province of China

| Population | No. of isolates | Polymorphic locia (%) | Nei's locus diversity (H) | Shannon's index (I) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YCW | 28 | 83.33 | 0.2646 | 0.3985 |

| YCY | 9 | 75.00 | 0.2472 | 0.3757 |

| YX | 32 | 75.00 | 0.2097 | 0.3304 |

| JZ | 21 | 83.33 | 0.2370 | 0.3639 |

| HG | 20 | 58.33 | 0.1876 | 0.2813 |

| Total | 110 | 87.50 | 0.2713 | 0.4106 |

The percentage of polymorphic loci was calculated by the formula (A/B) × 100, where A indicates the number of polymorphic bands and B the total number of amplified bands.

Based on genetic distance (Table 5), a dendrogram of geographic populations was generated. YCW and YCY populations were the most closely related, whereas the HG population was most distant from other populations (Fig. 5A).

TABLE 5.

Genetic distances among different geographic groups according to RAPD and SNP analysis

| Population | RAPD analysis |

SNP analysis |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YX | HG | YCW | YCY | YX | HG | YCW | YCY | |

| YX | ||||||||

| HG | 0.1322 | 0.0060 | ||||||

| YCW | 0.0342 | 0.1175 | 0.0066 | 0.0073 | ||||

| YCY | 0.0360 | 0.0969 | 0.0082 | 0.0061 | 0.0064 | 0.0039 | ||

| JZ | 0.0414 | 0.0865 | 0.0544 | 0.0526 | 0.0064 | 0.0060 | 0.0060 | 0.0058 |

FIG 5.

Dendrograms from RAPD and SNP analysis of different geographic populations in Hubei province. (A) Dendrogram according to genetic distance by RAPD analysis. YCW and YCY populations were closely related, whereas the HG population was the most distant from other populations. (B) Dendrogram according to genetic distance by SNP analysis. YCW and YCY populations were closely related, whereas the HG and YX populations were distant from other populations.

Phylogenetic analysis of 110 isolates based on SNP markers.

The isolates were also phylogenetically analyzed by using SNP markers. Results showed that they were divided into four genetic groups on the basis of a 1,730-bp SNP-rich sequence; 75.68% of YC isolates were clustered in groups II and IV, while 59.38%, 65%, and 57.14% of YX isolates, HG isolates, and JZ isolates, respectively, were clustered in group I (Fig. 6). Consistent with RAPD analysis, HG84, HG99, HG93, HG92, HG37, HG12, HG49, HG68, HG72, HG30, HG6, HG96, and HG56 from 10 rice cultivars in the Huanggang field were clustered together; YCW127, YCW121, YCW223, YCW83, YCW84, YCW45, YCW81, YCW40, YCW42, YCW219, and YCW101 from 11 rice cultivars in the Yichang Wangjia field were in the same clade; and YX73, YX88, YX93, YX27, YX85, and YX23 from 6 rice cultivars in the Yangxin field were in the same clade (Fig. 6). The isolates HG12, HG72, HG84, and HG96, obtained from cultivar Wanxian 98, shared 100% identity; YCY211 and YCW161 from Wanxian 98 shared 100% identity (Fig. 6). Other isolates from identical rice cultivars were distributed in different clades (Table 3).

FIG 6.

Phylogeny of 110 isolates of V. virens. The MP tree was inferred from the 1,730-bp combined DNA sequences data set. The numbers labeled at each node indicate the bootstrap percentages (n = 1,000). Four genetic groups were generated; group I and group IV were the larger groups. Group I included isolates from Yangxin (YX), Huanggang (HG), and Jingzhou (JZ), while Yichang (YCY and YCW) isolates were most clustered in groups II and IV.

Genetic distances within individual groups ranged from 0.004 to 0.006 with a mean value of 0.0048, which was lower than the mean genetic distance between groups (0.006). These results are consistent with the RAPD results and show that isolates from different geographic populations had higher levels of genetic diversity than isolates from individual geographical populations. Based on genetic distances (Table 5), a dendrogram of geographic populations was generated. Similar to RAPD analysis, YCW and YCY populations were most closely related, whereas the HG and YX populations were distant from other populations (Fig. 5B).

Population genetic analysis.

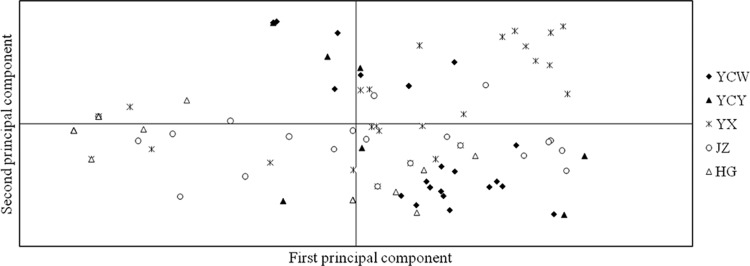

Based on the RAPD and SNP data, different populations were compared, and the pairwise FST values showed significant genetic differentiation between most compared populations, except for the YCW versus YCY population (from different fields in the same city), but both methods also showed minor inconsistencies (YX versus JZ and YCY versus JZ) (Table 6). The distance-based AMOVA showed that genetic variation was 83% (RAPD) and 81% (SNP) within the populations, while 17% (RAPD) and 19% (SNP) of variation was observed among populations, indicating that rich genetic diversity existed in individual geographic populations. The data support that rice cultivars have a significant impact on V. virens populations. PCA showed no clear separation of isolates from different populations, but isolates of the same populations tended to cluster together (Fig. 7). This suggests that rice cultivars play an important role for the formation of V. virens populations, but the geographical environments play an even more important role.

TABLE 6.

Pairwise FST values between different populationsa

| Population | RAPD analysis |

SNP analysis |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YX | HG | YCW | YCY | YX | HG | YCW | YCY | |

| YX | ||||||||

| HG | 0.3237*** | 0.1490*** | ||||||

| YCW | 0.1263*** | 0.3064*** | 0.2646*** | 0.4603*** | ||||

| YCY | 0.0782* | 0.2504*** | −0.0065 | 0.1273* | 0.3536** | 0.0081 | ||

| JZ | 0.0591* | 0.2122*** | 0.1366*** | 0.0866* | 0.0248 | 0.1186** | 0.1569*** | 0.0503 |

*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

FIG 7.

Principal component analysis (PCA) based on RAPD data for 110 individual isolates from five single fields in Hubei province. Individuals within the same population are marked using the same symbols. The first and second principal coordinates account for 22.76% and 15.66% of the variation, respectively. There was no clear separation among individuals from different populations, but isolates in the same populations tended to gather together.

DISCUSSION

V. virens isolates from a single field located at Huazhong Agricultural University tended to group according to their cultivar origin, confirming that there was great similarity among the isolates from the same cultivars in one field. Therefore, it is possible that the gene-for-gene interaction also occurred in the pathosystem between rice and V. virens, and such interaction caused the virulence specificity. The other 110 V. virens isolates were collected primarily from different cultivars with different genetic backgrounds but located in same fields in Hubei province, i.e., 20 HG isolates were from 17 cultivars, 32 YX isolates from 32 cultivars, 21 JZ isolates from 19 cultivars, 28 YCW isolates from 27 cultivars, and 9 YCY isolates from 9 cultivars. Analysis of these isolates provides an opportunity to elucidate the selection pressure for populations imposed by geographical environment and cultivar. If isolates from different cultivars of the same field tend to be most similar genetically, then geographic environments play a more important role than rice cultivars in shaping population structure. Collecting a single isolate versus many isolates from individual rice cultivars may be an advantage for our analysis, because multiple isolates may increase the similarity of isolates in individual geographical populations and overshadow environmental effects. Most studies used multiple isolates from limited cultivars. For instance, the V. virens isolates used for analysis of genetic diversity were from only one field (33) or no more than 8 cultivars per field (32, 35–37).

The RAPD method is a convenient means of investigating genetic variation, but the reproducibility of this technique can be poor (42). In our research, only the clear and reproducible polymorphic bands were recorded, and results were confirmed by SNP markers. The genetic diversity of V. virens isolates from north China was analyzed by AFLP, and V. virens isolates from other provinces of China, including Fujian and Hunan, were assessed by RAPD (32, 33, 35, 37, 43, 44). In this study, the 1,730-bp sequence used for SNP analysis was stable after 50 transfers on PSA for isolates YCY239 and YX92, indicating the stability of this marker. SNP and RAPD results were largely consistent. The selected RAPD primers and the 1,730-bp sequence can be widely used in the future for genetic diversity analysis in V. virens.

The phylogenetic trees generated based on RAPD and SNP were generally in agreement. They both showed that most isolates from the same rice cultivar but from different fields did not cluster together, while isolates from different cultivars of the same field tended to cluster together. Since it is not obvious whether the genetic variation is geography or host specific, the software Popgen 3.2 was used to analyze the RAPD data and assess whether geographical factor or rice cultivar plays a major role in population selection. The values of Nei's gene diversity (H) and Shannon's information index (I) showed that the genetic diversity of all isolates (even some isolates from different geographical fields were from the same rice cultivars) was higher than that of each geographical subpopulation from different cultivars, suggesting that isolates had a higher level of genetic correlation with geographic distribution than with rice cultivars. Similar results were obtained with our SNP data set. Evidence of other plant-pathogenic fungi grouping according to their geographical locations was reported. For example, the combined ISSR and RAPD data set of 51 French and Spanish Monilinia fructicola isolates showed a pronounced divergence according to geographic region (45). Even though there was no clear correlation between Macrophomina phaseolina and geographical origin or host species origin, a tendency to cluster according to geographical origin was observed (46).

Some researchers point out that V. virens can be influenced by geographical environment, because isolates in the same region showed a high degree of similarity (36). Other investigators found that most strains from the same rice cultivar clustered together regardless of the geographic origin (35). Yang et al. did not find that isolates were genetically linked to geographic origin or rice cultivars (37). Our data indicated that geographic origin influences population structure more than rice cultivar. The pairwise FST values in population genetic analysis further showed significant genetic differentiation between most compared populations. It is reasonable that different rice cultivars are suitable for different geographical environments; thus, they form different V. virens populations. Some isolates from the same cultivar in different locations, e.g., YCY211 and YCW161 from Wanxian 98, showed 100% identity based on both RAPD and SNP data, suggesting that the rice false smut disease also is a kind of seed-borne disease. In contrast to other studies, we had different data sets to analyze the effects of geographical environments and rice cultivars for the selection of V. virens. The first data set of 43 isolates was from just two cultivars in one field; thus, it can enhance the evaluation of the effect of rice cultivar. The second data set of 110 isolates was from five different geographical fields, and almost every isolate was from a different rice cultivar.

The HG population had the lowest genetic diversity, while the YCW, YCY, JZ, and YX isolates had higher genetic diversity. The RAPD and SNP results both showed that HG6, HG12, HG37, HG49, HG56, HG68, HG93, HG96, and HG99, isolated from 8 different rice cultivars, had 100% identity, among which HG12 and HG96 were collected from the same rice cultivar, Wanxian 98, indicating that these strains had extremely similar genetic backgrounds, even though they were from different rice cultivars. Meanwhile, the identity among HG30, HG90, and HG92 also reached 100%, suggesting a high similarity coefficient in the HG isolates from different rice cultivars. The isolates from Huanggang city showed a high degree of identity and low diversity, which indicated that the diversity of V. virens was associated with geography and not rice cultivar. Genetic diversity was correlated with genetic recombination through sexual crosses (38). The genetic diversity of V. virens in Huanggang was lower than that in other fields, and this lower genetic divergence suggests that sexual reproduction in Huanggang is less active than that in other fields. Low temperature favors the formation of sclerotia and Huanggang is frequently exposed to extreme heat compared to other rice-cropping areas (47), which might affect sexual reproduction and consequently genetic diversity of V. virens isolates in Huanggang. The YCW population showed the closest relationship with YCY isolates (Fig. 4 and Table 6), probably because they both belong to YC city and shared similar environments.

In our research, JZ53-2 (isolated in 2010) and JZ9 (isolated in 2011) were both from the same field in Jingzhou city and the same rice cultivar, Yixiang 3724; YCW161 (isolated in 2010) and YCW121 (isolated in 2011) were both from the same field in Yichang Wangjia and the same rice cultivar, Wanxian 98, but they clustered separately, supporting our conclusions that rice cultivars impose less stress on populations than the environment. This phenomenon was also reported by Wang et al. (44).

FST values of pairwise populations were used to evaluate the genetic differences between different populations. Most populations showed significant genetic differentiation according to the pairwise FST values based on the RAPD data and SNP data. This is consistent with the conclusion that geographical environment have important impacts on the fungal population. It also confirms that YCW was closely related to the YCY population. Although significant differences between YX and JZ, YCY, and JZ were not found based on SNP data, FST values from RAPD data revealed differences among these populations. PCA allows for visualizing the patterns of genetic relationship without altering the data itself and finds patterns within a multidimensional data set. PCA using RAPD data showed more samples based on the first two principal components than SNP data (data not shown), but it was the same as genetic differences among isolates within populations and gene flow between different populations.

The results in this study imply that geographical environments influence genetic variation of V. virens more than rice cultivars. V. virens is a biotrophic plant pathogen (4) that is quite different from other biotrophic/hemibiotrophic plant pathogens but similar to necrotrophic pathogens to a certain degree, implying that the identification of resistant germ plasma is difficult. Actually, cultivars immune to V. virens have not been identified to date. This information could be used to improve the management strategy for rice false smut by adjusting cultivation measures such as fertilizer, water, and planting density in the rice field to change the microenvironment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Guido Schnabel, School of Agricultural, Forestry & Environmental Sciences, Clemson University, USA, for his critical comments and review of the manuscript.

This material is based upon work supported by the Special Fund for Agroscientific Research in the Public Interest (no. 200903039-3) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (no. 2013PY108).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 28 February 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.White JF, Jr, Sullivan R, Moy M, Patel R, Duncan R. 2000. An overview of problems in the classification of plant-parasitic Clavicipitaceae. Stud. Mycol. 45:95–105 http://www.fungalbiodiversitycentre.com/publications/1045/content/pdf/095-105.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanaka E, Ashizawa T, Sonoda R, Tanaka C. 2008. Villosiclava virens gen. nov., comb. nov., teleomorph of Ustilaginoidea virens, the causal agent of rice false smut. Mycotaxon 106:491–501 http://www.researchgate.net/publication/234130822 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashizawa T, Takahashi M, Arai M, Arie T. 2012. Rice false smut pathogen, Ustilaginoidea virens, invades through small gap at the apex of a rice spikelet before heading. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 78:255–259. 10.1007/s10327-012-0389-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang YX, Jin J, Hu DW, Yong ML, Xu Y, He LP. 2013. Elucidation of the infection process of Ustilaginoidea virens (teleomorph: Villosiclava virens) in rice spikelets. Plant Pathol. 62:1–8. 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2012.02629.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luduena RF, Roach MC, Prasad V, Banerjee M, Koiso Y, Li Y, Iwasaki S. 1994. Interaction of ustiloxin A with bovine brain tubulin. Biochem. Pharmacol. 47:1593–1599. 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90537-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakamura K, Izumiyama N, Ohtsubo K, Koiso Y, Iwasaki S, Sonoda R, Fujita Y, Yaegashi H, Sato Z. 1994. “Lupinosis”-like lesions in mice caused by ustiloxin, produced by Ustilaginoieda virens: a morphological study. Nat. Toxins 2:22–28. 10.1002/nt.2620020106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y, Koiso Y, Kobayashi H, Hashimoto Y, Iwasaki S. 1995. Ustiloxins, new antimitotic cyclic peptides: interaction with porcine brain tubulin. Biochem. Pharmacol. 49:1367–1372. 10.1016/0006-2952(95)00072-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang DW, Wang S, Fu SF. 2004. Research advance on false smut of rice. Liaoning Agric. Sci. 2004:21–24. 10.3969/j.issn.1002-1728.2004.01.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahonsi MO, Adeoti AA. 2002. False smut on upland rice in eight rice producing locations of Edo State, Nigeria. J. Sustain. Agric. 20:81–94. 10.1300/J064v20n03_08 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atia MMM. 2004. Rice false smut (Ustilaginoidea virens) in Egypt. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 111:71–82 http://www.jpdp-online.com/artikel.dll/2004-01-s071-082-atia-ricep_NjE1NjU.PDF [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duhan JC, Jakhar SS. 2000. Prevalence and incidence of bunt and false smut in paddy (Oryza sativa) seeds in Haryana. Seed Res. (New Delhi) 28:181–185 http://www.cabdirect.org/abstracts/20013069387.html [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ashizawa T, Takahashi M, Moriwaki J, Hirayae K. 2010. Quantification of the rice false smut pathogen Ustilaginoidea virens from soil in Japan using real-time PCR. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 128:221–232. 10.1007/s10658-010-9647-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang JY, Zeng LX, Chen S, Li CY, Wei JL, Tan XQ, Zhu XY. 2011. Research advance on rice false smut (Ustilaginoidea virens) in China. Guangdong Agric. Sci. 38:77–79. 10.3969/j.issn.1004-874X.2011.02.032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen ZY, Nie YF, Liu YF. 2009. Identification of rice resistant to rice false smut and the virulence differentiation of Ustilaginoidea virens in Jangsu province. Jiangsu J. Agric. Sci. 25:737–741. 10.3969/j.issn.1000-4440.2009.04.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brooks SA, Anders MM, Yeater KM. 2011. Influences from long-term crop rotation, soil tillage, and fertility on the severity of rice grain smuts. Plant Dis. 95:990–996. 10.1094/PDIS-09-10-0689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang HK, Lin FC. 2008. Research advances in rice false smut, Ustilaginoiden virens. Acta Agric. Zhejiangensis 20:385–390. 10.3969/j.issn.1004-1524.2008.05.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reddy JM, Raoof MA, Ulaganathan K. 2012. Development of specific markers for identification of Indian isolates of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ricini. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 134:713–719. 10.1007/s10658-012-0047-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weber B, Halterman DA. 2012. Analysis of genetic and pathogenic variation of Alternaria solani from a potato production region. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 134:847–858. 10.1007/s10658-012-0060-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mandal AK, Dubey SC. 2012. Genetic diversity analysis of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum causing stem rot in chickpea using RAPD, ITS-RFLP, ITS sequencing and mycelial compatibility grouping. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 28:1849–1855. 10.1007/s11274-011-0981-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu MJ, Cox KD, Schnabel G, Luo CX. 2011. Monilinia species causing brown rot of peach in China. PLoS One 6:e24990. 10.1371/journal.pone.0024990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chalmers KJ, Waugh R, Sprent JI, Simons AJ, Powell W. 1992. Detection of genetic variation between and within populations of Gliricidia sepium and G. maculata using RAPD markers. Heredity 69(Part 5):465–472 http://www.nature.com/hdy/journal/v69/n5/pdf/hdy1992151a.pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han CS, Xie G, Challacombe JF, Altherr MR, Bhotika SS, Brown N, Bruce D, Campbell CS, Campbell ML, Chen J, Chertkov O, Cleland C, Dimitrijevic M, Doggett NA, Fawcett JJ, Glavina T, Goodwin LA, Green LD, Hill KK, Hitchcock P, Jackson PJ, Keim P, Kewalramani AR, Longmire J, Lucas S, Malfatti S, McMurry K, Meincke LJ, Misra M, Moseman BL, Mundt M, Munk AC, Okinaka RT, Parson-Quintana B, Reilly LP, Richardson P, Robinson DL, Rubin E, Saunders E, Tapia R, Tesmer JG, Thayer N, Thompson LS, Tice H, Ticknor LO, Wills PL, Brettin TS, Gilna P. 2006. Pathogenomic sequence analysis of Bacillus cereus and Bacillus thuringiensis isolates closely related to Bacillus anthracis. J. Bacteriol. 188:3382–3390. 10.1128/JB.188.9.3382-3390.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bielecki A, Polok K. 2012. Genetic variation and species identification among selected leeches (Hirudinea) revealed by RAPD markers. Biologia 67:721–730. 10.2478/s11756-012-0063-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tibayrenc M, Meubauer K, Barnabe C, Guerrini F, Skarecky D, Ayala FJ. 1993. Genetic characterization of six parasitic protozoa: parity between random-primer DNA typing and multilocus enzyme electrophoresis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90:1335–1339. 10.1073/pnas.90.4.1335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Enkerli J, Ghormade V, Oulevey C, Widmer F. 2009. PCR-RFLP analysis of chitinase genes enables efficient genotyping of Metarhizium anisopliae var. anisopliae. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 102:185–188. 10.1016/j.jip.2009.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bidochka M, McDonald M, Leger R, Roberts D. 1994. Differentiation of species and strains of entomopathogenic fungi by random amplification of polymorphic DNA (RAPD). Curr. Genet. 25:107–113. 10.1007/BF00309534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inglis GD, Duke GM, Goettel MS, Kabaluk JT. 2008. Genetic diversity of Metarhizium anisopliae var. anisopliae in southwestern British Columbia. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 98:101–113. 10.1016/j.jip.2007.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Budak H, Shearman RC, Parmaksiz I, Dweikat I. 2004. Comparative analysis of seeded and vegetative biotype buffalograsses based on phylogenetic relationship using ISSRs, SSRs, RAPDs, and SRAPs. Theor. Appl. Genet. 109:280–288. 10.1007/s00122-004-1630-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nazrul MI, Bian Y. 2011. Differentiation of homokaryons and heterokaryons of Agaricus bisporus with inter-simple sequence repeat markers. Microbiol. Res. 166:226–236. 10.1016/j.micres.2010.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luan F, Zhang S, Wang B, Huang B, Li Z. 2013. Genetic diversity of the fungal pathogen Metarhizium spp., causing epizootics in Chinese burrower bugs in the Jingting Mountains, eastern China. Mol. Biol. Rep. 40:515–523. 10.1007/s11033-012-2088-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riahi L, Zoghlami N, Dereeper A, Laucou V, Mliki A, This P. 2013. Single nucleotide polymorphism and haplotype diversity of the gene NAC4 in grapevine. Ind. Crops Products 43:718–724. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.08.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou YL, Fan JJ, Zeng CZ, Liu XZ, Wang S, Zhao KJ. 2004. Preliminary analysis of genetic diversity and population structure of Ustilaginoidea virens. Zhi Wu Bing Li Xue Bao 34:442–448. 10.3321/j.issn:0412-0914.2004.05.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pan YJ, Fan JJ, Binying FU, Wang J, Jianlong XU, Chen H, Zhikang LI, Zhou Y. 2006. Genetic diversity of Ustilaginoidea virens revealed by AFLP I: genetic structure of the pathogen in a field. Zhi Wu Bing Li Xue Bao 36:337–341. 10.3321/j.issn:0412-0914.2006.04.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou YL, Pan YJ, Xie XW, Zhu LH, Xu JL, Wang S, Li ZK. 2008. Genetic diversity of rice false smut fungus, Ustilaginoidea virens, and its pronounced differentiation of populations in North China. J. Phytopathol. 156:559–564. 10.1111/j.1439-0434.2008.01387.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan XP, Song JW, Liu EM, Liu NX, Wang JH, Xiao QM. 2008. Analysis of genetic diversity of Ustilaginoidea virens in Hunan. Hunan Nong Ye Da Xue Xue Bao 34:694–697 http://d.g.wanfangdata.com.cn/Periodical_hunannydx200806018.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang M, Li JS, Liu J, Song W, Dai HX. 2009. Preliminary analysis of genetic diversity of Ustilaginoidea virens strains of indica rice from Sichuan province. Zhi Wu Bao Hu Xue Bao 36:113–118 http://d.g.wanfangdata.com.cn/Periodical_zwbhxb200902003.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang XJ, Wang ST, Yao JN, Du YX, Chen FR. 2011. Analysis of genetic diversity of Ustilaginoidea virens from Fujian province based on RAPD markers. J. Agric. Biotechnol. 19:1110–1119. 10.3969/j.issn.1674-7968.2011.06.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun X, Kang S, Zhang Y, Tan X, Yu Y, He H, Zhang X, Liu Y, Wang S, Sun W, Cai L, Li S. 2013. Genetic diversity and population structure of rice pathogen Ustilaginoidea virens in China. PLoS One 8:e76879. 10.1371/journal.pone.0076879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. 2011. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28:2731–2739. 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Excoffier L, Laval G, Schneider S. 2005. Arlequin (version 3.0): an integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evol. Bioinformatics 1:47–50 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2658868/pdf/ebo-01-47.pdf [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peakall R, Smouse PE. 2012. GenAlEx 6.5: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research—an update. Bioinformatics 28:2537–2539. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones C, Edwards K, Castaglione S, Winfield M, Sala F, van de Wiel C, Bredemeijer G, Vosman B, Matthes M, Daly A, Brettschneider R, Bettini P, Buiatti M, Maestri E, Malcevschi A, Marmiroli N, Aert R, Volckaert G, Rueda J, Linacero R, Vazquez A, Karp A. 1997. Reproducibility testing of RAPD, AFLP and SSR markers in plants by a network of European laboratories. Mol. Breed. 3:381–390. 10.1023/A:1009612517139 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pan YJ, Wang S, Yang H, Liu XZ, Xie XW, Zhou YL. 2007. Effect of rice varieties on the population structure of Ustilaginoidea virens. Zhi Wu Bing Li Xue Bao 37:214–216. 10.3321/j.issn:0412-0914.2007.02.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang ST, Lin TB, Gan L, Shi NN, Yang XJ, Chen FR. 2012. Analysis of cultural characteristics and genetic diversity of Ustilaginoidea virens from some regions in China. Zhi Wu Bing Li Xue Bao 39:217–223 http://d.g.wanfangdata.com.cn/Periodical_zwbhxb201203005.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 45.Villarino M, Larena I, Martinez F, Melgarejo P, Cal AD. 2012. Analysis of genetic diversity in Monilinia fructicola from the Ebro Valley in Spain using ISSR and RAPD markers. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 132:511–524. 10.1007/s10658-011-9895-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Myaek-Perez N, Lopez-Castaneda C, Gonzalex-Chavira M, Garcia-Espinoa R, Acosta-Gallegos J, Vega OM, Simpson A. 2001. Variability of Mexican isolates of Macrophomina phaseolina based on pathogenesis and AFLP genotype. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 59:257–264. 10.1006/pmpp.2001.0361 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liao ZW, Gong XM, Hu CX, Zou J, Li XK. 2007. Nutrient status in paddy soils from different regions in Hubei province. J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. 26:186–190. 10.3321/j.issn:1000-2421.2007.02.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]