Abstract

Knowledge of the diversity of mercury (Hg)-methylating microbes in the environment is limited due to a lack of available molecular biomarkers. Here, we developed novel degenerate PCR primers for a key Hg-methylating gene (hgcA) and amplified successfully the targeted genes from 48 paddy soil samples along an Hg concentration gradient in the Wanshan Hg mining area of China. A significant positive correlation was observed between hgcA gene abundance and methylmercury (MeHg) concentrations, suggesting that microbes containing the genes contribute to Hg methylation in the sampled soils. Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) showed that the hgcA gene diversity in microbial community structures from paddy soils was high and was influenced by the contents of total Hg, SO42−, NH4+, and organic matter. Phylogenetic analysis showed that hgcA microbes in the sampled soils likely were related to Deltaproteobacteria, Firmicutes, Chloroflexi, Euryarchaeota, and two unclassified groups. This is a novel report of hgcA diversity in paddy habitats, and results here suggest a link between Hg-methylating microbes and MeHg contamination in situ, which would be useful for monitoring and mediating MeHg synthesis in soils.

INTRODUCTION

Mercury (Hg) pollution is a global issue, because Hg can be transported long distances and also can be converted later into highly neurotoxic methylmercury (MeHg) via microbial processes in the environment (1–3). It has been argued that inorganic Hg(II) is methylated via the methylcobalamin cofactor and an acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) pathway (4–6). A recent study (7) identified Hg methylation genes, hgcA (that encodes a putative corrinoid protein) and hgcB (that encodes a 2[4Fe-4S] ferredoxin), in Hg-methylating microbes. This provides corroboration of a mechanistic model of Hg methylation. A methyl group is transferred from the methylated HgcA protein to inorganic Hg(II), and an HgcB protein is required for the turnover (8). Hg-methylating microbes in the environment have been identified mainly as sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) (9, 10), iron-reducing bacteria (IRB) (3, 11, 12), and methanogens (13–15). Recently, additional microbial species containing hgcAB orthologs from novel environmental niches also have been shown to have mercury methylation capacity (16). The direct linkage between functional genes influencing MeHg synthesis and Hg-methylating microbes in natural environments, however, has not been investigated.

While community characterization of Hg methylators (for example, SRB) has been studied by correlating Hg methylation activities with specific taxa in a variety of habitats (17–19), no direct association has been found due to a lack of knowledge regarding functional genes involved in microbial Hg methylation in the environment so far. It has been reported that at least four microorganism phyla contain a gene involved in Hg methylation, hgcA or hgcB, including Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, and Euryarchaeota (7, 10). However, whether the genes contribute a selective advantage related to Hg concentration or toxicity remains unclear (20). Moreover, the effects of environmental factors on the community that possesses the genes are completely unknown, although distribution patterns of microorganisms are usually influenced by a variety of factors in the environment (e.g., environmental variables and spatial and time factors) (21–24). Paddy soils represent a typical freshwater environment that usually produces anaerobic conditions attributed to oxygen depletion after flooding (25), in which inorganic Hg(II) may be methylated by some anaerobic microorganisms (26). The environmental risks of inorganic Hg(II) in paddy soils become more serious as a consequence of its potential methylation by anaerobic microorganisms. Recent studies (27, 28) reported high MeHg content present in both paddy soil and rice grains from Guizhou province in southwest China. Consequently, production of MeHg in paddy soils by microorganisms has become a paramount public health concern (29); therefore, understanding the controls of Hg and MeHg cycling in rice paddies is crucial. Our knowledge of Hg-methylating microbes in paddy soils, however, currently is very limited. Therefore, a detailed molecular characterization of the diversity of Hg-methylating microbes will be important to guide research for monitoring and mitigating MeHg production in rice fields.

The recent identification of two functional genes involved in Hg methylation (7) provided the possibility for developing a molecular biomarker for detecting Hg methylation-related genes from environmental samples (8, 15). HgcA drives the first step in Hg methylation by microorganisms through transferring the methyl group, so it is very important to characterize the microbial community containing hgcA genes in paddy soils. The objectives of this study were to assess the presence and structural diversity of hgcA genes in paddy soil by using newly developed primer pairs for hgcA genes and to examine potential shifts in hgcA-contained microbial community structure associated with different total Hg levels.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling and analytical methods.

The Wanshan area was one of the major Hg-producing regions in the world, located in the eastern region of Guizhou province, southwest China (109°12′E, 27°31′N). The Wanshan area has a typical hilly and karstic terrain with a subtropical humid climate, and it is the site of serious Hg pollution resulting from waste discharge following a long-term history of Hg mining (28, 30). Soil profiles were collected from four sites (referred to as sites S1, S2, S3, and S4) located at different distances from the Hg mining site. Total Hg concentrations in the soil samples declined from S1 to S4. A total of 48 soil samples (three replicates from each plot) were taken at different depths (0 to 20 cm, 20 to 40 cm, 40 to 60 cm, and 60 to 80 cm) at the 4 sites. Each soil sample was passed through a 2.0-mm sieve and stored at −20°C prior to molecular analyses. One soil subsample (0.149 mm) was air dried for general property analyses, and another one was freeze-dried for the analysis of total Hg and MeHg. For total Hg analysis, soil samples were first digested with HNO3-HCl (10 ml; 1:1, vol/vol) in a Teflon tube at 100°C for 2 h, and the Hg concentration in the solution was determined using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). Two standard reference materials, GBW-07401 (GSS-1) and GBW-07405 (GSS-5), were included in the analytical process for quality assurance/quality control. MeHg was extracted using CuSO4-methanol/sovent extraction according to a method described previously (30), after which MeHg levels were determined using high-performance liquid chromatography–ICP-MS (31). Percentages of MeHg recovery ranged from 85 to 125%. The basic chemical characteristics of the tested soils from the four sites are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Primer design and amplification of hgcA genes.

A primer pair for detecting the hgcA gene was designed against HgcA orthologs in 6 confirmed and 2 putative Hg-methylating microbes retrieved from the NCBI database (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Selected hgcA sequences were aligned with DNAMAN (version 7.0; Lynnon Biosoft, USA) and are shown in Fig. S1. Forward (hgcA4F; 5′-GGNRTYAAYRTCTGGTGYGC-3′) and reverse (hgcA4R; 5′-CGCATYTCCTTYTYBACNCC-3′) primers were developed according to nucleotide sequences in conserved regions, including the conserved HgcA motif. A 25-μl PCR mixture contained 12.5 μl premix (TaKaRa Bio Inc., Japan), 0.5 μl of each 10 μM primer pair, 2 μl DNA template (1 to 10 ng), and 9.5 μl PCR-grade water. Optimized PCR thermal cycling parameters were the following: 94°C for 5 min (1 cycle); 94°C for 1 min, 60°C (reduced by −0.5°C per cycle) for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min (10 cycles); and 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min (30 cycles). Following this, reaction mixtures were further extended at 72°C for 10 min. PCR products were checked using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis.

DNA extraction and quantification of hgcA gene.

Total microbial DNA was extracted from 0.5-g soil samples using Ultraclean soil DNA isolation kits (MoBio Laboratory, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Soil DNA from paddy soils was diluted 10-fold and subjected to real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) to determine the abundance of hgcA in each sample. The abundance of the hgcA gene was quantified using the primer pairs described above. The qPCR was performed on an iQ5 thermocycler (Bio-Rad, USA) in a 25-μl reaction mixture containing 12.5 μl SYBR premix Ex Taq (TaKaRa Bio Inc., Japan), 1 μl DNA template, and 0.5 μl each of 10 μM solutions of primers hgcA4F and hgcA4R. Thermal cycling parameters for qPCR were the same as those mentioned above. Melting curve analysis was performed at the end of PCR runs to check for specificity of amplification reactions.

To prepare standard curves, hgcA gene sequences were amplified from extracted DNA with the primer pair described above (hgcA4F/hgcA4R). PCR amplicons were ligated to a pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, USA) and transformed into Escherichia coli JM109 cells. Positive clones containing the target gene insert were sequenced, and the most abundant one was used for plasmid DNA extraction. After measuring the DNA concentration with a Nanodrop ND-1000 UV-visible spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Co., USA), the purified plasmid DNA was diluted serially in 10-fold steps and subjected to real-time PCR in triplicate to generate an external standard curve.

Construction of hgcA gene clone libraries.

In total, 12 topsoils (three replicates from four sites) were selected for the construction of hgcA gene clone libraries. PCR products from DNA samples from the paddy soils were generated as described above using primer pair hgcA4F/hgcA4R and then purified with the Wizard SV gel and PCR clean-up system (Promega, USA). Purified PCR products were ligated into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, USA) and then transformed into E. coli JM109 (TaKaRa Bio Inc., Japan) according to the manufacturer's protocols. Positive clones (about 100 clones per library) were selected randomly from these clone libraries and sequenced using the M13F primer in an ABI 3700 sequencer (Applied Biosystems, USA). Sequences showing more than 80% identity were grouped into the same operational taxonomic units (OTUs) using the Mothur program (32).

Phylogenetic and analysis.

To check for similarities, representative hgcA gene sequences were compared to entries in the NCBI database using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST). Phylogenetic analysis of hgcA sequences in the NCBI database, as well as sequences obtained from the current study, were performed using MEGA version 5.0, and neighbor-joining trees were constructed using Kimura two-parameter distance with 1,000 replicates to generate bootstrap values.

Statistical analysis.

Alpha diversity of hgcA genes was estimated using Mothur software (33). Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) (Canoco 4.5 for Windows) was used to explore relationships between the various microbial species detected and environmental factors. Variables to be included in the model were chosen by forward selection at the 0.05 baseline. Significance of the constrained ordination process was tested using a Monte Carlo permutation test. A Venn diagram illustrating the similarity of the hgcA-containing microbial communities in paddy soils from the different sites was generated using the gplot package in the R statistical software (http://www.r-project.org). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess differences among soil variables in all the sites, and all results were represented as means with the associated standard errors. Statistical significance was assessed using SPSS 13.0 software. Bivariate correlations were conducted to estimate the link among different parameters.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Sequences from different OTUs were deposited in the GenBank nucleotide sequence database under the following accession numbers: KJ184661 to KJ184836.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Primer design for amplification of hgcA genes.

PCR amplification with the degenerate pair of primers designed here for the hgcA gene produced a single product of 680 bp. The products were successfully amplified from the 48 tested soils. Methanospirillum hungatei (DSM 864; provided by Xiuzhu Dong) was used as a positive control for the hgcA gene, since it has been confirmed to be able to methylate Hg in a recent study (15). All obtained sequences were translated into amino acid sequences and aligned with the HgcA orthologs from several confirmed Hg-methylating microbes (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material) in which the highly conserved regions were observed, including the confirmed conserved motif of HgcA, N(V/I)WCA(A/G)GK (7). They were also very similar to corrinoid iron-sulfur protein (CFeSP) associating with the acetyl-CoA pathway that can transfer MeHg+ as the substrate (34). Together, these results provide multiple assurances for choosing the correct sequences in primer design. Therefore, we concluded that the primers we designed were effective in the amplification of the hgcA genes from all 48 tested soil samples, including those from the deep soil samples, and that the presence of the hgcA genes in the rice paddies is widely spread.

Abundance of the hgcA gene and its contribution to MeHg production.

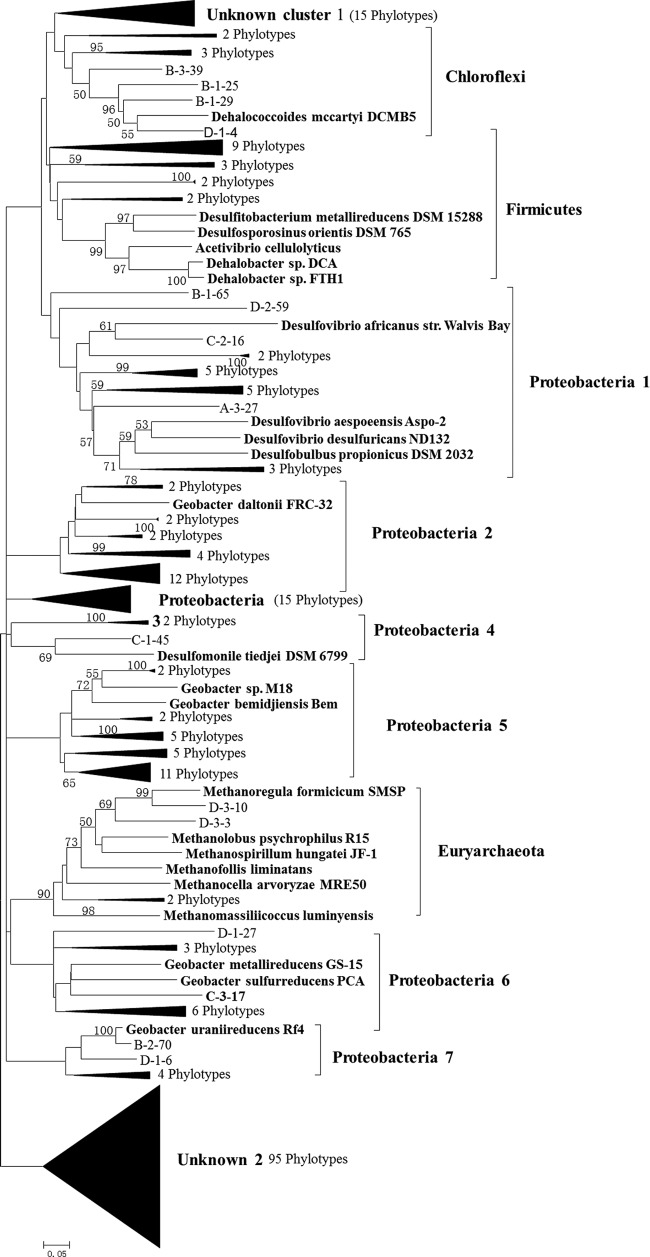

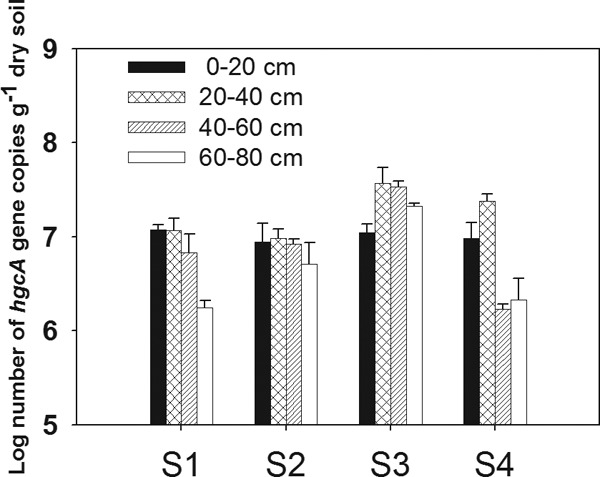

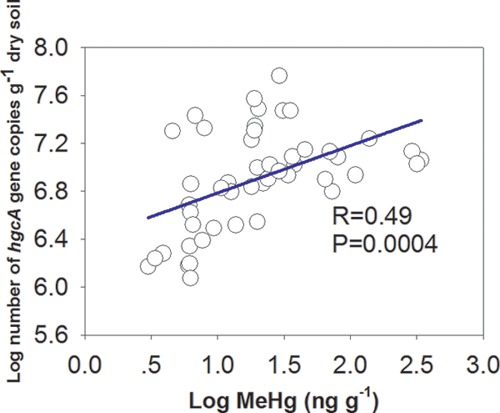

In order to understand the association between hgcA gene abundance and MeHg concentrations, hgcA gene copy numbers in the soil profiles at the four sites were quantified using qPCR (Fig. 1). We found different distribution patterns with respect to the hgcA abundance along the soil profile at the four sites, but the reasons for these differences remain unclear. Interestingly, this pattern is similar to the distribution of total bacterial abundance (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Positive linear correlation of hgcA gene abundance with MeHg content indicated their contribution to the production of MeHg in the soils (Fig. 2). However, the mercury methylation was affected not only by the hgcA gene abundance but also by the availability of Hg(II) and other soil factors. As shown in Table S3, the MeHg content was also correlated with SO42−, organic matter (OM), NH4+, and total Hg content, indicating that these environmental factors are highly influential in affecting MeHg production in natural habitats (35–37).

FIG 1.

Abundance of hgcA genes in soil profiles from the four sites (S1, S2, S3, and S4) in the Wanshan Hg mining area, Guizhou, China.

FIG 2.

Regression between hgcA abundance and MeHg concentration in soils from the Wanshan Hg mining area.

Diversity of hgcA genes in paddy fields.

Our study's goal was to explore the hgcA gene diversity of microbial communities, especially in rice paddies surrounding the Hg mining area. We selected topsoils for analyzing the microbial community because topsoil is more easily disturbed by anthropogenic activity than deeper soil. Topsoils that constitute the arable layers also have a high potential for being a significant environmental risk if they accumulate MeHg. All constructed clone libraries showed relatively high coverage. The high coverage was also reflected by the respective rarefaction curves, which tended to approach a plateau (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). The relatively low α diversity of the observed hgcA gene at site S1 (Table 1) could be associated with the highest total Hg or MeHg content. Whereas the total Hg concentration was negatively correlated with the soil microbial community in previous studies (38–40), there was no clearly linear correlation shown between α diversity of the hgcA+ microbial community and total Hg levels in the present study. This might result from miscellaneous effects of other variables in the paddy soils.

TABLE 1.

Alpha diversity of the hgcA+ microbial community in paddy soils

| Soil sitea | No. of sequences | Coverage | Sobsb | Shannon index | Simpson index | Chao 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 257 | 0.90 ± 0.059 a | 27 ± 7 b | 2.85 ± 0.28 b | 0.072 ± 0.0227 a | 38.54 ± 18.35 b |

| S2 | 258 | 0.75 ± 0.016 b | 39 ± 3 a | 3.32 ± 0.11 a | 0.035 ± 0.0125 b | 66.22 ± 9.08 a |

| S3 | 254 | 0.80 ± 0.043 ab | 36 ± 4 ab | 3.27 ± 0.22 a | 0.041 ± 0.0170 b | 49.74 ± 6.47 ab |

| S4 | 264 | 0.79 ± 0.022 b | 35 ± 3 ab | 3.18 ± 0.14 ab | 0.047 ± 0.0084 ab | 64.08 ± 9.38 a |

S1, S2, S3, and S4 indicate the four sampling sites with different soil Hg contents.

Number of observed OTUs.

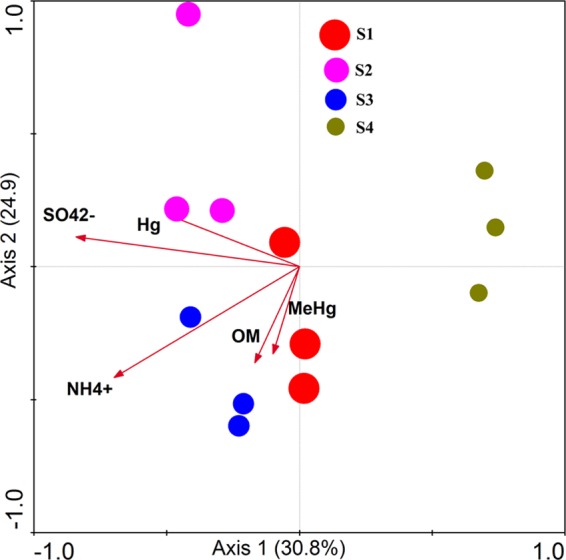

According to the CCA, the effects of individual environmental factors on community varied across the four sites (Fig. 3). The parameter of pH values in CCA was rejected due to its inflation factor being higher than 20. The variance in the relationship between species (OTU) and environmental factors was explained by the two CCA axes, with 55.7% total variance contribution. HgcA communities were separated into four distinct clusters corresponding to different sites. However, we found similar OTUs of soil hgcA genes in the Venn diagram (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material), in which 10 OTUs were shared among all four sites. The SO42− concentration was found to be the most significant variable that influenced the community structure, and it was shown to stimulate MeHg production and enhance SRB activities in sediments (10, 41), even though it is well known that sulfide generated from sulfate reduction could inhibit microbial Hg methylation (42). In the current study, the NH4+ content was the second important impact variable, followed by the contents of total Hg and OM. The influence of NH4+ on the community may be exerted in the soil OM in which ammonification was stimulated by anaerobic conditions, resulting in ammonium accumulation.

FIG 3.

Relationships (CCA) between hgcA diversity and the biogeochemical factors in soils (the contents of organic matter [OM], MeHg, NH4+, SO42−, and total Hg). Values on axes represent cumulative percent variations of species-environment relationships explained by consecutive axes. The sizes of circles represent relative mean MeHg levels.

Phylogenetic analysis of hgcA gene sequences.

A phylogenetic tree of hgcA gene sequences from our samples was constructed by using confirmed hgcA genes as reference species retrieved from NCBI (Fig. 4). The results showed that all hgcA gene sequences fell into 12 distinct clusters at the phylum level. These included different frequencies of Proteobacteria (7 subclusters), Firmicutes, Chloroflexi, Euryarchaeota, and 2 unclassified clusters (Fig. 5). All Proteobacteria families classified belonged to Deltaproteobacteria, a phylum with which most currently confirmed Hg-methylating bacteria are affiliated (3, 43). The majority of the Deltaproteobacteria-like sequences were related to sulfate-reducing and iron-reducing bacteria. Interestingly, a few Euryarchaeota-like sequences were detected and were closely related to Methanomicrobia, which has been considered the principal Hg methylator in Lake Periphyton and in some other habitats according to previous studies (13, 15). Most Euryarchaeota-like sequences were found at S4, where the total Hg content was similar to local background levels and the sulfate concentration was not high enough to inhibit methanogenesis activity compared to that at the other sites. It remains unclear, however, whether the presence of Euryarchaeota methylators was linked to Hg levels or other soil factors. These sparse distributions of hgcA microbial phylotypes have been thought to be irrelevant to Hg toxicity in the soil (20). They may reflect the gene loss or even lateral gene transfer among distantly related taxa (7). We noticed the phylogenetic discrepancies between the taxonomy groups based on OTU identification with the hgcA and 16S rRNA genes. This is not surprising, because prokaryotes (and some eukaryotes) are asexual and could not form species in a genetic way. Instead, the ecological species can be a species as a set of individuals that can be considered to be identical in the relevant ecological function (44).

FIG 4.

Phylogenetic analysis of hgcA sequences retrieved from paddy soils based on neighbor-joining analysis using MEGA 5.0. The designation of clones includes the name of the site (A, B, C, and D represent clones from S1, S2, S3, and S4, respectively) and clone code. Bootstrap values (>50%) are indicated at branch points. The scale bar represents 5% estimated sequence divergence.

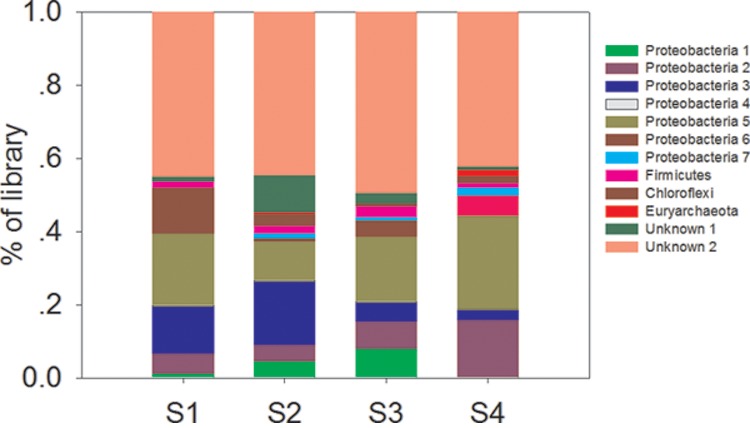

FIG 5.

OTU-based relative abundance of hgcA families in different-colored clusters at the four different sites.

The distribution patterns of each cluster in the four sites were different (Fig. 5). The proportion of Proteobacteria cluster 2 tended to increase when the percentage of Proteobacteria cluster 3 organisms decreased, which could reflect differences in Hg concentration. However, these distribution patterns also could have been due to unknown factors and need to be further studied. Therefore, our results suggest that direct amplification of Hg methylation genes from environmental genomic DNA or RNA could establish the link between potential MeHg contamination and Hg-methylating microbes in nature, a puzzle which has gone unsolved for decades.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Tamar Barkay for constructive suggestions.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41201523 and 41090281).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 28 February 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.04225-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hu H, Lin H, Zheng W, Tomanicek SJ, Johs A, Feng X, Elias DA, Liang L, Gu B. 2013. Oxidation and methylation of dissolved elemental mercury by anaerobic bacteria. Nat. Geosci. 6:751–754. 10.1038/ngeo1894 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schaefer JK, Rocks SS, Zheng W, Liang L, Gu B, Morel FMM. 2011. Active transport, substrate specificity, and methylation of Hg(II) in anaerobic bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:8714–8719. 10.1073/pnas.1105781108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu RQ, Flanders JR, Mack EE, Turner R, Mirza MB, Barkay T. 2012. Contribution of coexisting sulfate and iron reducing bacteria to methylmercury production in freshwater river sediments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46:2684–2691. 10.1021/es2033718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barkay T, Wagner-Döbler I. 2005. Microbial transformations of mercury: potentials, challenges, and achievements in controlling mercury toxicity in the environment. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 57:1–52. 10.1016/S0065-2164(05)57001-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi SC, Chase T, Bartha R. 1994. Metabolic pathways leading to mercury methylation in Desulfovibrio desulfuricans LS. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:4072–4077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsu-Kim H, Kucharzyk KH, Zhang T, Deshusses MA. 2013. Mechanisms regulating mercury bioavailability for methylating microorganisms in the aquatic environment: a critical review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47:2441–2456. 10.1021/es304370g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parks JM, Johs A, Podar M, Bridou R, Hurt RA, Smith SD, Tomanicek SJ, Qian Y, Brown SD, Brandt CC, Palumbo AV, Smith JC, Wall JD, Elias DA, Liang L. 2013. The genetic basis for bacterial mercury methylation. Science 339:1332–1335. 10.1126/science.1230667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poulain AJ, Barkay T. 2013. Cracking the mercury methylation code. Science 339:1280–1281. 10.1126/science.1235591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Compeau GC, Bartha R. 1985. Sulfate-reducing bacteria: principal methylators of mercury in anoxic estuarine sediment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 50:498–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilmour CC, Henry EA, Mitchell R. 1992. Sulfate stimulation of mercury methylation in freshwater sediments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 26:2281–2287. 10.1021/es00035a029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleming EJ, Mack EE, Green PG, Nelson DC. 2006. Mercury methylation from unexpected sources: molybdate-inhibited freshwater sediments and an iron-reducing bacterium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:457–464. 10.1128/AEM.72.1.457-464.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerin EJ, Gilmour CC, Roden E, Suzuki MT, Coates JD, Mason RP. 2006. Mercury methylation by dissimilatory iron-reducing bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:7919–7921. 10.1128/AEM.01602-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamelin S, Amyot M, Barkay T, Wang Y, Planas D. 2011. Methanogens: principal methylators of mercury in lake periphyton. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45:7693–7700. 10.1021/es2010072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wood JM, Kennedy FS, Rosen CG. 1968. Synthesis of methylmercury compounds by extracts of a methanogenic bacterium. Nature 220:173–174. 10.1038/220173a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu RQ, Reinfelder JR, Hines ME, Barkay T. 2013. Mercury methylation by the methanogen Methanospirillum hungatei. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79:6325–6330. 10.1128/AEM.01556-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilmour CC, Podar M, Bullock AL, Graham AM, Brown S, Somenahally AC, Johs A, Hurt R, Bailey KL, Elias D. 2013. Mercury methylation by novel microorganisms from new environments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47:11810–11820. 10.1021/es403075t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King JK, Kostka JE, Frischer ME, Saunders FM. 2000. Sulfate-reducing bacteria methylate mercury at variable rates in pure culture and in marine sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2430–2437. 10.1128/AEM.66.6.2430-2437.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winch S, Mills HJ, Kostka JE, Fortin D, Lean DRS. 2009. Identification of sulfate-reducing bacteria in methylmercury-contaminated mine tailings by analysis of SSU rRNA genes. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 68:94–107. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2009.00658.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu RQ, Adatto I, Montesdeoca MR, Driscoll CT, Hines ME, Barkay T. 2010. Mercury methylation in Sphagnum moss mats and its association with sulfate-reducing bacteria in an acidic Adirondack forest lake wetland. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 74:655–668. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2010.00978.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilmour CC, Elias DA, Kucken AM, Brown SD, Palumbo AV, Schadt CW, Wall JD. 2011. Sulfate-reducing bacterium Desulfovibrio desulfuricans ND132 as a model for understanding bacterial mercury methylation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:3938–3951. 10.1128/AEM.02993-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cao P, Zhang LM, Shen JP, Zheng YM, Di HJ, He JZ. 2012. Distribution and diversity of archaeal communities in selected Chinese soils. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 80:146–158. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01280.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu HW, Zhang LM, Yuan CL, He JZ. 2013. Contrasting Euryarchaeota communities between upland and paddy soils exhibited similar pH-impacted biogeographic patterns. Soil Biol. Biochem. 64:18–27. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.04.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu YR, He JZ, Zhang LM, Zheng YM. 2012. Effects of long-term fertilization on the diversity of bacterial mercuric reductase gene in a Chinese upland soil. J. Basic Microbiol. 52:35–42. 10.1002/jobm.201100211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu YR, Zheng YM, Zhang LM, He JZ. 2014. Linkage between community diversity of sulfate-reducing microorganisms and methylmercury concentration in paddy soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 21:1339–1348. 10.1007/s11356-013-1973-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu XZ, Zhang LM, Prosser JI, He JZ. 2009. Abundance and community structure of sulfate reducing prokaryotes in a paddy soil of southern China under different fertilization regimes. Soil Biol. Biochem. 41:687–694. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2009.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rothenberg SE, Feng XB. 2012. Mercury cycling in a flooded rice paddy. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 117:G03003. 10.1029/2011JG001800 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feng X, Li P, Qiu G, Wang S, Li G, Shang L, Meng B, Jiang H, Bai W, Li Z, Fu X. 2008. Human exposure to methylmercury through rice intake in mercury mining areas, Guizhou province, China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42:326–332. 10.1021/es071948x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang H, Feng X, Larssen T, Shang L, Li P. 2010. Bioaccumulation of methylmercury versus inorganic mercury in rice (Oryza sativa L.) grain. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44:4499–4504. 10.1021/es903565t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meng B, Feng X, Qiu G, Liang P, Li P, Chen C, Shang L. 2011. The process of methylmercury accumulation in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Environ. Sci. Technol. 45:2711–2717. 10.1021/es103384v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qiu G, Feng X, Li P, Wang S, Li G, Shang L, Fu X. 2008. Methylmercury accumulation in rice (Oryza sativa L.) grown at abandoned mercury mines in Guizhou, China. J. Agric. Food Chem. 56:2465–2468. 10.1021/jf073391a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen D, Jing M, Wang X. 2005. Determination of methyl mercury in water and soil by HPLC–ICP-MS. Agilent Technologies, Columbia, MD [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schloss PD, Westcott SL. 2011. Assessing and improving methods used in operational taxonomic unit-based approaches for 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:3219–3226. 10.1128/AEM.02810-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, Hall JR, Hartmann M, Hollister EB, Lesniewski RA, Oakley BB, Parks DH, Robinson CJ, Sahl JW, Stres B, Thallinger GG, Van Horn DJ, Weber CF. 2009. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:7537–7541. 10.1128/AEM.01541-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doukov TI, Iverson TM, Seravalli J, Ragsdale SW, Drennan CLA. 2002. Ni-Fe-Cu center in a bifunctional carbon monoxide dehydrogenase/acetyl-CoA synthase. Science 298:567–572. 10.1126/science.1075843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi SC, Bartha R. 1994. Environmental-factors affecting mercury methylation in estuarine sediments. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 53:805–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gu B, Bian Y, Miller CL, Dong W, Jiang X, Liang L. 2011. Mercury reduction and complexation by natural organic matter in anoxic environments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:1479–1483. 10.1073/pnas.1008747108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han S, Obraztsova A, Pretto P, Deheyn DD, Gieskes J, Tebo BM. 2008. Sulfide and iron control on mercury speciation in anoxic estuarine sediment slurries. Mar. Chem. 111:214–220. 10.1016/j.marchem.2008.05.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duran R, Ranchou-Peyruse M, Menuet V, Monperrus M, Bareille G, Goni MS, Salvado JC, Amouroux D, Guyoneaud R, Donard OFX, Caumette P. 2008. Mercury methylation by a microbial community from sediments of the Adour Estuary (Bay of Biscay, France). Environ. Pollut. 156:951–958. 10.1016/j.envpol.2008.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hayyis-Hellal J, Vallaeys T, Garnier-Zarli E, Bousserrhine N. 2009. Effects of mercury on soil microbial communities in tropical soils of French Guyana. Appl. Soil Ecol. 41:59–68. 10.1016/j.apsoil.2008.08.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu YR, Zheng YM, Shen JP, Zhang LM, He JZ. 2010. Effects of mercury on the activity and community composition of soil ammonia oxidizers. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 17:1237–1244. 10.1007/s11356-010-0302-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benoit JM, Gilmour CC, Mason RP, Heyes A. 1999. Sulfide controls on mercury speciation and bioavailability to methylating bacteria in sediment pore waters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 33:951–957. 10.1021/es9808200 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gilmour CC, Riedel GS, Ederington MC, Bell JT, Benoit JM, Gill GA, Stordal MC. 1998. Methylmercury concentrations and production rates across a trophic gradient in the northern Everglades. Biogeochemistry 40:327–345. 10.1023/A:1005972708616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ranchou-Peyruse M, Monperrus M, Bridou R, Duran R, Amouroux D, Salvado JC, Guyoneaud R. 2009. Overview of mercury methylation capacities among anaerobic bacteria including representatives of the sulphate-reducers: implications for environmental studies. Geomicrobiol. J. 26:1–8. 10.1080/01490450802599227 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prosser JI, Bohannan BJ, Curtis TP, Ellis RJ, Firestone MK, Freckleton RP, Green JL, Green LE, Killham K, Lennon JJ, Osborn AM, Solan M, van der Gast CJ, Young JP. 2007. The role of ecological theory in microbial ecology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5:384–392. 10.1038/nrmicro1643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.