Abstract

Virtually all bacteria possess a peptidoglycan layer that is essential for their growth and survival. The β-lactams, the most widely used class of antibiotics in human history, inhibit d,d-transpeptidases, which catalyze the final step in peptidoglycan biosynthesis. The existence of a second class of transpeptidases, the l,d-transpeptidases, was recently reported. Mycobacterium tuberculosis, an infectious pathogen that causes tuberculosis (TB), is known to possess as many as five proteins with l,d-transpeptidase activity. Here, for the first time, we demonstrate that loss of l,d-transpeptidases 1 and 2 of M. tuberculosis (LdtMt1 and LdtMt2) alters cell surface morphology, shape, size, organization of the intracellular matrix, sorting of some low-molecular-weight proteins that are targeted to the membrane or secreted, cellular physiology, growth, virulence, and resistance of M. tuberculosis to amoxicillin-clavulanate and vancomycin.

INTRODUCTION

The peptidoglycan layer is present in virtually all bacteria and is essential for its survival and growth. This layer is classically described as a structural component that is assembled outside the membrane, that is largely cross-linked by 4→3 transpeptide linkages, and that gives shape and turgidity to the cell but otherwise is not dynamic (1). Based on this paradigm of peptidoglycan biology, 3→3 transpeptide linkages observed in Mycobacterium spp. and Escherichia coli were considered unusual and were speculated to be modifications or derivatives of 4→3 linkages (2–5). Recent studies have demonstrated that the peptidoglycan layer of Mycobacterium spp. is largely cross-linked by 3→3 transpeptide linkages (6–8). A significant effort was made to identify l,d-transpeptidases based on the hypothesis that they may be close sequence homologs of d,d-transpeptidases (9, 10). In E. coli, altered growth rates and susceptibility to β-lactams have been reported in relation to changes in the composition of 3→3 linkages in the peptidoglycan (4, 11). An increase in the proportion of 3→3 transpeptide linkages reduces growth rates and subsequently decreases the susceptibility of E. coli to β-lactams.

Inhibition of the biosynthesis of the peptidoglycan layer has been successfully exploited, as drugs that target this layer are the most widely used antibiotics to treat bacterial infections in humans. β-Lactams, a class of drugs that inhibit peptidoglycan biosynthesis, comprise more than half of all antibiotics regularly prescribed to treat bacterial infections (12). The β-lactams act by inhibiting d,d-transpeptidases (also known as penicillin-binding proteins), a class of enzymes that catalyze the formation of transpeptide linkages between the fourth amino acid of one peptide stem and the third amino acid of another stem. Recently, a complementary class of enzymes, namely, l,d-transpeptidases, that transfer peptide linkage between the l and d centers of the third and the fourth amino acids of donor peptide to the third amino acid of acceptor peptide has been identified in numerous bacteria, including Enterococcus faecium, Bacillus subtilis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Clostridium difficile, and E. coli (6, 13–18). Despite the significance of d,d-transpeptidases, which serve as targets to the most widely used class of antibiotics, the study of the relevance of l,d-transpeptidases to the physiology of the cell and susceptibility to drugs has only recently begun. Within 6 months following the first report describing the crystal structure and mechanism of l,d-transpeptidation by LdtMt2 (19), four additional reports describing structural details of l,d-transpeptidases of M. tuberculosis were published (20–23).

The M. tuberculosis genome encodes as many as five proteins with l,d-transpeptidase activity, namely, LdtMt1 to LdtMt5 (6, 16, 24). While biochemical properties and the contribution of LdtMt2 to the physiology of M. tuberculosis have been reported (16, 19–22), studies of LdtMt1 have been limited to biochemical characterization (6, 23). In this study, for the first time, we have generated and studied M. tuberculosis strains lacking LdtMt1 and both LdtMt1 and LdtMt2 and describe the cellular phenotypes associated with the loss of these l,d-transpeptidases. We report that the M. tuberculosis strain that lacks both ldtMt1 and ldtMt2 displays altered cellular morphology, size, physiology, and in vitro and in vivo growth and enhanced susceptibility to amoxicillin-clavulanate and a glycopeptide drug, vancomycin. In addition, the mutant is defective in sorting of low-molecular-weight proteins that are otherwise either targeted to the membrane or secreted. Our observations demonstrate that loss of both ldtMt1 and ldtMt2 results in phenotypes that are unique and/or severe compared to the single mutants lacking only ldtMt1 or ldtMt2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and in vitro growth conditions.

A clinical isolate of M. tuberculosis, CDC1551 (25), was used as the wild-type strain and as the parent strain for generating a knockout strain lacking ldtMt1. A previously generated M. tuberculosis mutant of CDC1551 lacking a functional copy of ldtMt2 (strain M2) (16) served as the parent strain for generating a double-knockout strain lacking both ldtMt2 and ldtMt1 (strain M12). The ldtMt1 knockout mutant (strain M1) was constructed as described previously (26). M1 was complemented with a wild-type copy of ldtMt1 (yielding strain M1c1) via previously reported techniques and with pMH94 as the integrating plasmid (27). Similarly, M12 was complemented with wild-type copies of ldtMt1 (yielding strain M12c1), ldtMt2 (yielding strain M12c2), or both ldtMt1 and ldtMt2 (yielding strain M12c12). All strains were grown under standard conditions, in Middlebrook 7H9 broth (Difco) supplemented with 0.5% glycerol, 10% oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase (OADC), and 0.05% Tween 80 with constant shaking at 37°C. Additional description is provided in the supplemental materials and methods.

RNA isolation and quantitative RT-PCR.

Cultures were grown to either exponential or stationary phase, pelleted by centrifugation, and resuspended in TRIzol (Invitrogen). Total RNA was then extracted from the lysed cells as described previously (28). Reverse transcription was carried out using SuperScriptIII (Invitrogen) and 50 ng of random primers (Invitrogen) per the manufacturer's directions. Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR was performed using SYBR green master mix (Applied Biosystems) in a StepOnePlus system (Applied Biosystems). Gene expression levels were normalized to that of sigA, a housekeeping gene whose expression levels have been shown to remain constant throughout growth (29). Additional protocol descriptions and primer sequences are provided in the supplemental materials and methods.

MIC.

The MICs of standard drugs used for treatment of tuberculosis (TB), as well as cell wall-acting drugs, were determined for the wild type and strains M1, M2, and M12. The MICs were determined using the standard broth dilution method (30). MICs were determined at both 2 and 3 weeks of incubation. The MIC studies were repeatable, and values shown are from one representative experiment of three independent experiments performed. Additional description is provided in the supplemental materials and methods.

Transmission and field emission scanning electron microscopy.

To study the cell surface morphologies of M. tuberculosis strains at exponential and stationary phases of growth, bacteria were immobilized to poly-l-lysine charged coverslips for 30 min and processed for field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM). Similarly, for transmission electron microscopy (TEM), live bacterial suspensions were fixed and embedded in Spurr's resin. Detailed descriptions of FESEM and TEM are provided in the supplemental materials and methods.

Proteomics study.

Wild-type M. tuberculosis and M12 were grown in Middlebrook 7H9 broth at 37°C. Cultures (50 ml) of each strain at exponential phase were centrifuged, washed twice with 10 mM NH4HCO3, resuspended in lysis buffer (10 mM NH4HCO3, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF]), and lysed by sonication. The mixture was centrifuged, and the soluble fraction containing cytosolic protein was isolated. Equal amounts of protein from each strain was digested with trypsin and subjected to iTRAQ labeling and analysis as per the manufacturer's protocol (AB Sciex). The labeled peptides were analyzed using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), and the MS/MS spectra were extracted using Xtract and an MS2 processor with Proteome Discoverer (v1.3; Thermo Scientific). Mascot (Matrix Science) was used to map peptide spectra and identify M. tuberculosis proteins.

In vivo growth and virulence studies.

The strains used for in vivo growth and virulence studies were as follows: (i) wild type, (ii) M1, (iii) M1c1, (iv) M2, (v) M12, (vi) M12c12, (vii) M12c1, and (viii) M12c2. Four- to six-week-old female BALB/c mice (Charles River) were infected via the aerosol route in a Glas-Col Middlebrook inhalation exposure system (Glas-Col Inc.).

For growth studies, 200 mice were divided into 8 groups of 25 and infected with appropriate strains to deliver ∼3 log10 CFU to the lungs. Four mice from each group were sacrificed 1 day following infection to determine lung implantation at baseline. At 2, 4, 8, 12, and 16 weeks, four mice from each group were sacrificed to determine the bacterial burden. Lungs and spleens were aseptically removed and mechanically homogenized in 0.8 ml of sterile 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) using 2-mm glass beads and a mini-beadbeater (BioSpec Products). Organ homogenates were plated on Middlebrook 7H11 selective plates (Becton, Dickinson) at appropriate dilutions, and CFU were counted after incubation for 4 weeks at 37°C.

For in vivo virulence studies, 160 mice were divided into 8 groups of 20 and were infected with appropriate strains to deliver ∼4 log10 CFU to the lungs. To determine implantation, four mice from each group were sacrificed 1 day following infection, and the lungs were removed and homogenized as described above. Survival was followed for each animal; data were analyzed by a Kaplan-Meier survival curve, and significance was determined by a log rank test in GraphPad Prism (P < 0.0001).

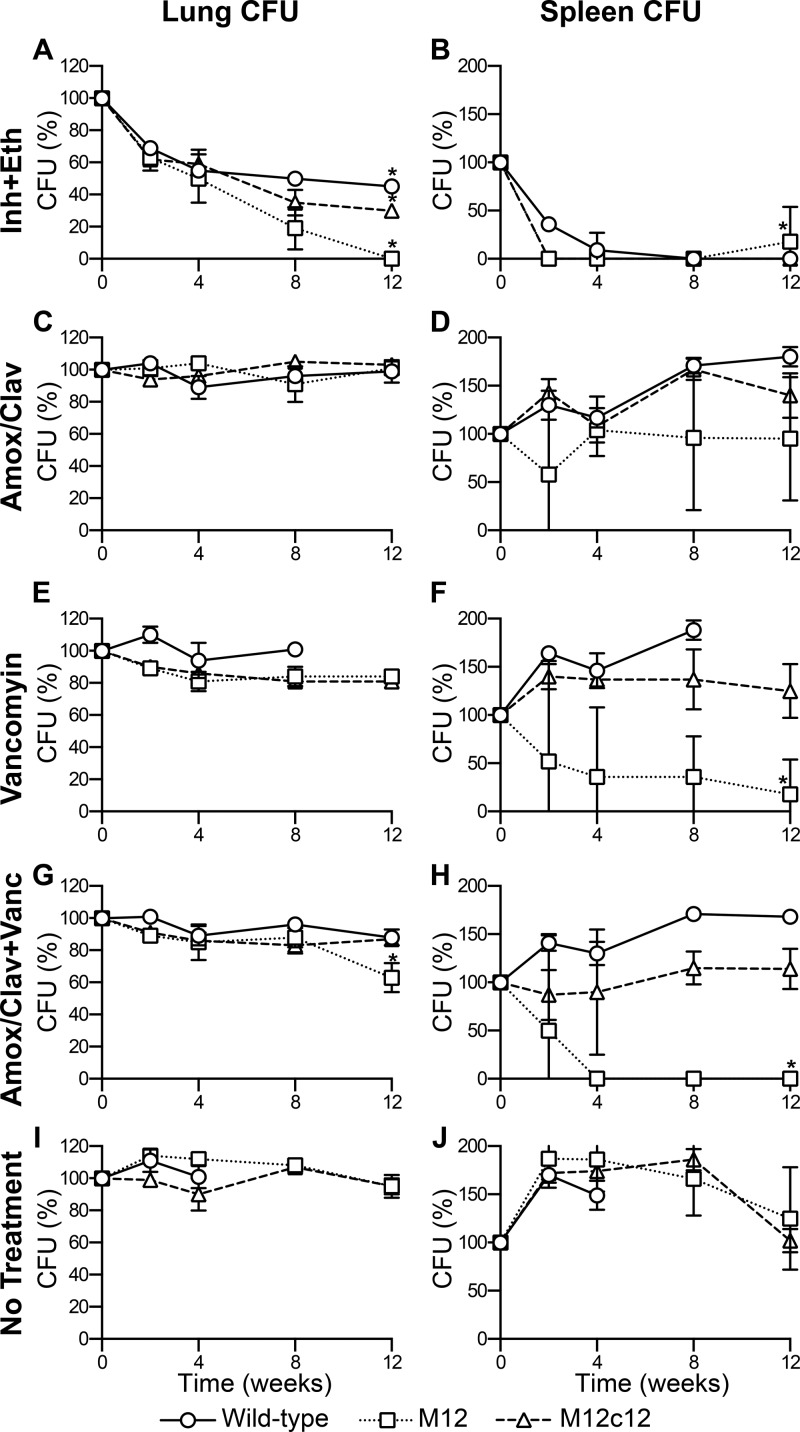

In vivo antibiotic susceptibility study.

For the in vivo antibiotic susceptibility study, 270 mice were divided into 3 groups of 90 and aerosol infected with either the wild type, M12, or M12c12, to obtain an ∼3-log10 CFU implantation in the lungs. Mice from each infection were randomized into 5 treatment groups. The no-treatment negative-control groups consisted of 24 mice, four of which were sacrificed 1 day following infection (week −2) to determine the bacterial burden at the time of implantation. Further, four of the negative-control mice were sacrificed at week 0 to establish the level of infection at the start of treatment. Two weeks after infection, mice were treated with either (i) isoniazid (25 mg/kg) plus ethambutol (100 mg/kg), (ii) amoxicillin-clavulanate (200 mg/kg amoxicillin, 50 mg/kg clavulanate), (iii) vancomycin (100 mg/kg), (iv) amoxicillin-clavulanate plus vancomycin, or (v) no drug. Mice were treated once daily, 5 days a week, with all drugs. Isoniazid plus ethambutol and amoxicillin-clavulanate were given by oral gavage, while vancomycin was given by intraperitoneal (IP) injection. Mice were sacrificed at weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12 to assess efficacy of treatment. Two-tailed Student's t test (P < 0.05) was performed to assess significance in CFU measurements.

RESULTS

Role of LdtMt1 in the physiology of M. tuberculosis.

LdtMt1 and LdtMt2 are paralogs that catalyze the 3→3 transpeptidation reaction between two stem peptides of the peptidoglycan (6, 16). Despite this potential functional redundancy, loss of LdtMt2 causes distinct growth, colony morphology, and drug susceptibility phenotypes (16). We studied the relevance of LdtMt1 to the physiology of M. tuberculosis by generating M. tuberculosis strains lacking only ldtMt1 (referred to as M1) and lacking both ldtMt2 and ldtMt1 (referred to as M12).

M1 was complemented using the stably integrating plasmid pMH94/Zeo containing a single full-length copy of ldtMt1 (yielding M1c1). The genotypes of the mutant and the complement were confirmed by Southern blot (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) and expression of ldtMt1 was verified using quantitative RT-PCR (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The size and shape of M. tuberculosis colonies of the wild-type parent and M1 on Middlebrook 7H10 solid media were identical. Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) revealed that the cell size and morphology of M1 and wild-type M. tuberculosis were similar. The average cell lengths of the wild type, M1, and the complemented strains were 1.8 μm, 1.7 μm, and 1.8 μm, respectively (Fig. 1A to D and 2A and B). Individual cells from all three strains ranged in length from 1 to 3 μm. The cell surface morphologies of M1, the wild type, and the complemented strains were indistinguishable from each other when observed using FESEM at either exponential or stationary phase (Fig. 1 and 2). The study of cross sections of each bacterial strain using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealed diffusely distributed electron-dense regions of condensed genomic DNA that is characteristic of a healthy M. tuberculosis cell (Fig. 2E and F) (31). In addition, the peptidoglycan layer was readily visible and had a thickness between 10 and 20 nm, identical to what was observed for the wild type (Fig. 2I and J). In vitro growth rates for the wild type, M1, and M1c1 were found to be indistinguishable (Fig. 3A). Therefore, loss of LdtMt1 alone did not alter in vitro growth rate or colony and cell shape and morphology.

FIG 1.

Field emission scanning electron microscopy to assess cell morphology and length of M. tuberculosis. FESEM images of late-exponential-phase wild-type (blue) (A), M1 (red) (B), M1c1 (pink) (C), M2 (green) (E), M2c2 (maroon) (F), M12 (purple) (H), M12c12 (lime green) (I), M12c1 (yellow) (J), and M12c2 (orange) (K) are shown. Magnification, ×20,000 (bar, 200 nm). (D, G, and L) Statistical analysis of cell lengths for wild-type, mutant, and complemented strains. Values are means and standard deviations (SD); n ≥ 100 for each sample. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed, with all strains being compared to wild-type M. tuberculosis (*, P < 0.05). M12, M12c1, and M2 were found to be significantly shorter than wild-type M. tuberculosis.

FIG 2.

Scanning and transmission electron microscopy to assess intracellular morphology. Images of wild-type M. tuberculosis (A, E, and I), M1 (B, F, and J), M2 (C, G, and K), and M12 (D, H, and L) were obtained from culture at exponential phase of in vitro growth by FESEM (A to D) and TEM (E to L). (D) White arrows indicate cell surface depressions in M12 cells. (I, J, K, and L) Black arrows indicate the cell wall of M. tuberculosis. (A to D) Magnification, ×35,000 (bar, 200 nm); (E to H) magnification, ×80,000 (bar, 100 nm); (I to L) magnification, ×100,000 (bar, 20 nm).

FIG 3.

Growth of wild-type, M1, M2, and M12 strains in both in vitro and in vivo settings. In vitro growth (A, E, and I) of wild-type (blue), M1 (red), M1c1 (pink), M2 (green), M2c2 (maroon), M12 (purple), M12c12 (lime green), M12c1 (yellow), and M12c2 (orange) in 7H9 broth. In vivo growth in the lungs (B, F, and J) and spleens (C, G, and K) of mice infected with the strains listed above was assessed. Bacterial burdens in the lungs and spleen were determined by enumerating CFU. Values are means ± SD (n = 4/group). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis (D, H, and L) of mice infected with all strains (n = 15/group) is also shown.

Loss of LdtMt1 and LdtMt2 severely alters cellular shape, intracellular morphology, and physiology.

Based on the apparent lack of phenotype in the absence of LdtMt1, we hypothesized that the phenotype of M. tuberculosis lacking both LdtMt2 and LdtMt1 would be similar to that of the mutant lacking LdtMt2. To test this hypothesis, we generated an M. tuberculosis strain lacking both ldtMt2 and ldtMt1 (M12). This strain was complemented with ldtMt1 (yielding M12c1), ldtMt2 (yielding M12c2), or both ldtMt1 and ldtMt2 (yielding M12c12), and these strains were used as control strains when appropriate (see Fig. S1 and S2 in the supplemental material). Unlike the parent wild-type M. tuberculosis strain, whose cell length was 1.8 μm, M12 was consistently shorter, with an average cell length of 1.0 μm (ranging from 0.6 to 1.9 μm; n ≥ 100; P < 0.05) (Fig. 1H). Complementation of M12 with wild-type copies of ldtMt1 and ldtMt2 restored the cell length phenotype (Fig. 1I). The wild type and strain M12c12 have the classical rod shape, but M12 cells have deep surface depressions and bulges (Fig. 1H and 2D). These cell surface depressions and bulges were observed in M2, but they were rare and not as conspicuous (Fig. 1E and 2C). This phenotype is further aggravated in the late exponential phase of growth, as M12 cells completely lost their rod shape and appeared as atypical amorphous structures (Fig. 1H). M1, M2, and the complemented strains did not exhibit this phenotype (Fig. 1). Based on these cell structure deformities, we studied the effect of loss of ldtMt2 and ldtMt1 on the organization of the intracellular components. Unlike the parent wild-type strain, M12 possesses large unstained vacuole-like structures (Fig. 2E and H). These structures do not exist in M1 and M2 (Fig. 2F and G). We were further able to assess the thickness of the peptidoglycan layer in each strain. Wild-type, M1, and M2 strains had a readily visible peptidoglycan layer with a thickness between 10 and 20 nm (Fig. 2I to K). M12 had a darkly staining peptidoglycan layer with a thickness ranging between 8 and 15 nm (Fig. 2L).

Loss of LdtMt1 and LdtMt2 severely alters protein localization.

We studied if the altered cell shape and vacuole like structures unique to M12 affected protein expression and localization. For this, we analyzed the cytosolic protein content of the wild type and M12 using a proteomics approach. All proteins expressed during the exponential phase were identified and quantified. We observed a differential abundance of proteins in the two strains (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). We further analyzed the proteins that are highly abundant in the cytosol of M12 and observed that localization of 95% of these proteins is altered. While 52.5% of these proteins have been experimentally shown to be membrane bound and the remaining 42.5% are secreted by wild-type M. tuberculosis, these proteins are largely sequestered in the cytoplasm of M12 (Fig. 4A; also, see Table S1). In addition, an overwhelming majority of these proteins are of low molecular weight, and the distribution of their molecular weights does not overlap the overall distribution of proteins of M. tuberculosis (Fig. 4B; also, see Table S1). Proteins that were differentially abundant in the cytoplasm of M12 had a geometric mean molecular mass of 21.63 ± 2.291 kDa, which is significantly smaller than that of proteins in wild-type M. tuberculosis (36.17 ± 0.4928 kDa) (Student's t test, P < 0.05) (Fig. 4B).

FIG 4.

Proteomic analysis of cytosolic proteins of wild-type M. tuberculosis versus M12. (A) Distribution of proteins whose targeting was altered in M12. Proteins that are otherwise membrane bound or secreted by wild-type M. tuberculosis are sequestered in the cytoplasm in M12. (B) Gaussian curve of the frequency distribution of the molecular masses of proteins whose localization has been altered. Proteins in the wild-type strain have a geometric mean molecular mass of 36.17 ± 0.4928 kDa, with a median of 30.6 kDa. Proteins in M12 that show an altered distribution have a geometric mean molecular mass of 21.63 ± 2.291 kDa, with a median of 17.0 kDa. Two-tailed Student's t test was performed to assess significance (*, P < 0.05).

Loss of LdtMt1 and LdtMt2 severely attenuates growth and virulence of M. tuberculosis.

We studied the relevance of LdtMt1 to the growth rate of M. tuberculosis by assessing growth of M1, M2, and M12 in vitro and in vivo. Although the growth rate of M1 in vitro was indistinguishable from that of the wild-type strain, M12 proliferated at one-third to one-fourth the rate of the wild type (Fig. 3I) and did not form clumps, which are characteristic of M. tuberculosis. Although loss of LdtMt2 alone attenuated growth of M. tuberculosis (Fig. 3E) (16), loss of both LdtMt2 and LdtMt1 further aggravated the ability of M. tuberculosis to grow (Fig. 3I). Growth of M12c2 and M12c12 was partially restored (Fig. 3I), although low expression levels of ldtMt2 in the complement strains relative to wild-type expression levels likely prevented full restoration of growth in these strains (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

Next, we studied the relevance of LdtMt1 on growth in vivo by assessing growth of all eight strains in BALB/c mice. An aerosolized infection with each strain resulted in implantation of ∼3 log10 CFU in the lungs of mice. The bacterial burdens in the lungs and spleens of mice infected with M1 were similar to those in mice infected with the wild type or the complemented strains throughout the course of infection (Fig. 3B and C). However, the burden of M12 in the lungs was consistently 3 log10 CFU lower than that of the wild type at both the acute (prior to 4 weeks of infection) and chronic (after 8 weeks of infection) stages of disease (Fig. 3J). This was further confirmed by the lack of observable inflammation and gross pathology in the lungs of mice (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Although M12 disseminated to the spleen at the same rate as the wild type, it failed to proliferate, and the M12 burden was consistently 2 log10 CFU lower than that of the wild type throughout the course of infection (Fig. 3K).

We evaluated the relevance of LdtMt1 to virulence of M. tuberculosis by determining morbidity and mortality rates in the mouse model of TB (32). For this, eight groups of mice were infected with the eight strains of M. tuberculosis to establish an infection with ∼4 log10 CFU in the lungs. Mice infected with wild-type M. tuberculosis were morbid before death and had a median survival time of 33 days, while 100% of the cohort infected with M12 survived, were healthy, and showed no signs of morbidity (Fig. 3L). The experiment was terminated at 9 months postinfection, as we considered that additional time would yield only marginal data on morbidity and mortality for each group. Although the mice infected with M12c12 and M12c2 showed signs of extreme morbidity, characterized by weight loss, hunched back, and ruffled fur, the mortality rates were only 10% and 20% for these groups of mice, respectively, at 9 months after infection. Mice infected with M12c1 showed signs of morbidity and also had 90% survival 9 months after infection (Fig. 3L).

Loss of LdtMt1 and LdtMt2 sensitizes M. tuberculosis to vancomycin and amoxicillin-clavulanate.

We hypothesized that the loss of LdtMt2 and LdtMt1 would affect the susceptibility of M. tuberculosis to inhibitors that target the biosynthesis of peptidoglycan. To study this, we determined the MICs of isoniazid, cycloserine, amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, imipenem, meropenem, ertapenem, cefoxitin, vancomycin, and teicoplanin against the wild type, M1, M2, and M12. The MICs of isoniazid and cycloserine were 0.025 to 0.05 and 2.5 to 5 μg/ml, respectively, for all strains. The MICs of vancomycin against M12 and the wild type were 1.3 to 1.7 and 30 to 40 μg/ml, respectively (Table 1). Therefore, M12 was 20-fold more sensitive to vancomycin than the wild-type strain. The MICs of amoxicillin-clavulanate against M12 and wild-type M. tuberculosis were 0.158 to 0.211 and 1.282 to 1.375 μg/ml, respectively (Table 1). Therefore, M12 was 8-fold more sensitive to amoxicillin-clavulanate than the wild-type strain.

TABLE 1.

MICs of standard regimen drugs and cell wall-acting antibiotics

| Drug | MIC (μg/ml)a |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | M1 | M2 | M12 | |

| Isoniazid | 0.25–0.05 | 0.25–0.05 | 0.25–0.05 | 0.25–0.05 |

| Cycloserine | 2.5–5 | 2.5–5 | 2.5–5 | 2.5–5 |

| Amoxicillin | 20–40 | 20–40 | 20–40 | 20–40 |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanate | 1.282–1.375 | 1.282–1.375 | 0.282–0.375 | 0.158–0.211 |

| Imipenem | 16.9–22.5 | 16.9–22.5 | 9.5–12.7 | 7.12–9.5 |

| Meropenem | 5–10 | 5–10 | 5–10 | 5–10 |

| Ertapenem | 20–40 | 10–20 | 10–20 | 5–10 |

| Cefoxitin | >40 | >40 | >40 | 20–40 |

| Vancomycin | 30–40 | 22.5–30 | 9.5–12.7 | 1.3–1.7 |

| Teicoplanin | >40 | >40 | 12.7–16.9 | 3–4 |

As very little variation was seen between experiments, the data from one representative experiment are shown.

Based on these observations, we studied the relevance of the loss of both LdtMt2 and LdtMt1 on the in vivo susceptibility to amoxicillin-clavulanate and vancomycin. BALB/c mice infected with wild-type M. tuberculosis, M12, or M12c12 were treated daily with (i) isoniazid plus ethambutol, (ii) amoxicillin-clavulanate, (iii) vancomycin, (iv) amoxicillin-clavulanate plus vancomycin, or (v) no drug. The isoniazid-plus-ethambutol-treated group served as the positive control, as these drugs are part of the standard regimen for treatment of TB. The no-treatment group served as a negative control. The combination of isoniazid and ethambutol was equally effective against all three strains, with CFU levels in the lungs decreasing by ∼4 log10 in all groups over the 12-week span of treatment (Fig. 5A and B). The bacterial burden in mice infected with wild-type M. tuberculosis and treated with amoxicillin-clavulanate, vancomycin, or amoxicillin-clavulanate plus vancomycin was similar to that in the no-treatment group, with a bacterial burden in the lungs of ∼6 log10 CFU at 8 weeks (Fig. 5). Mice infected with wild-type M. tuberculosis and treated showed signs of morbidity, including loss of weight, hunched backs, and ruffled fur. Eight mice in the no-treatment group and five mice in the vancomycin-only treatment group died during the first 4 weeks of treatment. It is worth noting that although mice infected with wild-type M. tuberculosis and treated with amoxicillin-clavulanate plus vancomycin were morbid by the end of treatment, there were no deaths in this group. Pervasive inflammatory lesions were observed by gross pathology of the lungs of control mice infected with wild-type M. tuberculosis that received no treatment. Mice infected with wild-type M. tuberculosis and treated with amoxicillin-clavulanate plus vancomycin had similar lung lesions (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material).

FIG 5.

Activity of amoxicillin-clavulanate and vancomycin against M. tuberculosis strains. Bacterial burden in the lungs and spleens of mice infected with the wild type (circles), M12 (squares), or M12c12 (triangles) and treated with isoniazid plus ethambutol (A and B), amoxicillin-clavulanate (C and D), vancomycin (E and F), or amoxicillin-clavulanate plus vancomycin (G and H) or not treated (I and J). Because of the different levels of infection at the start of treatment, CFU counts were normalized to those at week 0 and are plotted as a percentage, where the CFU count at week 0 is designated 100%. Normalized means ± SD are shown for all treatments (n = 4/time point/group). Two-tailed Student's t test (*, P < 0.05) was performed at week 12 for each treatment and infecting strain to assess the significance of the treatment relative to no treatment.

The bacterial burden in mice infected with M12c12 showed a trend similar to the burden in mice infected with wild-type M. tuberculosis. Treatment with amoxicillin-clavulanate, vancomycin, or amoxicillin-clavulanate plus vancomycin resulted in a bacterial burden similar to that of the no-treatment group, remaining around ∼5 log10 CFU after 12 weeks of treatment (Fig. 5), with any differences being insignificant by two-tailed Student's t test. Mice infected with M12c12 and treated showed signs of morbidity similar to those seen for mice infected with wild-type M. tuberculosis. There were no deaths in this infection group. Lung pathology observed for mice infected with M12c12 was similar to that for mice infected with the wild type (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material).

Mice infected with M12 and untreated had a peak bacterial burden of 4.5 log10 CFU in the lungs at week 2 of treatment (Fig. 5I), after which a slight drop and plateau were established. In mice infected with M12 and treated with amoxicillin-clavulanate, the bacterial burden remained relatively constant in the lungs at ∼4 log10 CFU throughout the 12 weeks of treatment (Fig. 5C). The same was observed in the spleens, with CFU remaining constant at ∼2 log10 (Fig. 5D). This was further reflected in the presence of disseminated lesions in the lungs of mice treated with amoxicillin-clavulanate (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Mice infected with M12 and treated with vancomycin showed a 0.6-log10-CFU drop in the lungs by week 12 of treatment (P < 0.05). This slight bactericidal effect was more prominently seen in the spleen, where a 1-log10-CFU decrease was observed by the end of treatment (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5E and F). Gross pathology indicated the presence of very few lesions throughout infection (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material) and no inflammation of tissue, as indicated by changes in organ weight and size (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). Finally, mice infected with M12 and treated with amoxicillin-clavulanate plus vancomycin showed a decrease in the bacterial burden in the lungs from 4 log10 CFU at the start of treatment to 2.5 log10 CFU by 12 weeks of treatment (P < 0.005) (Fig. 5G). The bactericidal effects of amoxicillin-clavulanate plus vancomycin were made more evident by the bacterial burden in the spleen, which reached culture negativity after 4 weeks of treatment and maintained this level through the remainder of the study (Fig. 5H). Gross pathology of the lungs of this group of mice indicated the presence of minimal lesions throughout the course of treatment, with no lesions being observed by week 12 (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). In addition, the lungs or the spleen weights remained constant throughout the course of treatment, indicating negligible inflammation due to the infection with M12 (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material).

DISCUSSION

The peptidoglycan layer is a structural organelle that is essential for growth and survival of bacteria. The biosynthesis of the peptidoglycan begins in the cytosol and culminates in formation of the cell wall (1, 33, 34). In addition to LdtMt1 and LdtMt2, a recent publication has annotated three paralogs, namely, those encoded by Rv1433 (MT0501), Rv0192 (MT0202), and Rv0483 (MT0501), as LdtMt3, LdtMt4, and LdtMt5 (24). M. tuberculosis strains lacking LdtMt3, LdtMt4, or LdtMt5 lack altered growth or colony phenotypes and are indistinguishable from the parent strain (16).

Here we have demonstrated that a combined loss of ldtMt2 and ldtMt1 severely alters cell size, growth rates in vitro and in vivo, virulence, and susceptibility to vancomycin and amoxicillin-clavulanate of M. tuberculosis. We also affirmed the dominance of LdtMt2 as the main l,d-transpeptidase (16). In addition, we observed an atypical cell shape, surface morphology, and distinct organization of the cytosolic matrix that are unique to the mutant lacking both ldtMt2 and ldtMt1 (Fig. 3). The large vacuole-like structures that are abundant in the cytosolic matrix of M12 are similar to those previously described as lipid inclusion bodies (35, 36). It is possible that these vacuole-like structures are aggregates of fatty acids and lipids that M12 fails to transport across the membrane due to changes in the cell resulting from the loss of these transpeptidases. Whether the possible accumulation of fatty acids and lipids within the cytosol contributes to the inability of cells to clump remains to be investigated. Preliminary results with Nile red staining indicate potential lipid bodies being hoarded within M12 cells and not within wild-type cells. This hypothesis was not tested further, as such testing was beyond the scope of this study. Assessment of protein expression and localization revealed that the loss of ldtMt1 and ldtMt2 alters localization of several proteins that are otherwise targeted to the membrane or secreted (Fig. 4; also, see Table S1 in the supplemental material). These proteins range from major secreted antigens encoded by Rv1174c (37), Rv1810 (38), Rv1926c (39), Rv1980c (38–40), Rv3004 (37), and Rv3312A (41) to integral membrane proteins (see Table S1). Notably, an l,d-transpeptidase, LdtMt4, encoded by Rv0192 (24), is 4.4-fold more abundant in the cytoplasm of M12 than in that of the wild-type strain. Further analysis revealed that the median molecular weights of proteins whose localizations have been altered are significantly lower than those of proteins in the wild type (Fig. 4; also, see Table S1). These data suggest that changes in the peptidoglycan from loss of LdtMt1 and LdtMt2 alter the cell's ability to secrete and target a range of proteins to the cell membrane. These observations implicate the peptidoglycan layer in sorting of proteins in M. tuberculosis.

We also demonstrate that these paralogs do not compensate for the loss of LdtMt1 and LdtMt2, as M12 exhibited altered cellular, physiological, and virulence phenotypes. Additional studies are warranted to determine cellular functions of these paralogs.

The crystal structure of LdtMt2 was recently reported by four independent groups (19–22). These studies also report molecular interactions with the substrate and the carbapenem class of drugs and the mechanism of catalysis by LdtMt2. A single transmembrane domain at the N terminus anchors the protein to the plasma membrane, while the extracellular domain with the catalytic site protrudes into the peptidoglycan layer. A crystal structure of LdtMt1 and a detailed description of its active site and its interaction with imipenem have also been recently reported (23).

M. tuberculosis possesses both l,d- and d,d-transpeptidases that catalyze the final steps of the peptidoglycan biosynthesis pathway by generating 3→3 and 4→3 transpeptide linkages (3, 6). Since the recent discovery of l,d-transpeptidases (6, 13, 16), independent laboratories have carried out studies to determine if they can be inhibited by the β-lactam class of drugs (6, 8, 16, 19–22, 42, 43), which classically have been demonstrated to target d,d-transpeptidases (12). Although β-lactams are rarely used for treatment of M. tuberculosis infection, recent reports demonstrate that the carbapenem subclass of β-lactams are effective against a range of M. tuberculosis strains (44–46). Although certain carbapenems have been demonstrated to bind to and inhibit l,d-transpeptidase activity (19, 21–23), it is not known if their M. tuberculosis growth-inhibitory activity is a result of inhibition of specific or multiple transpeptidases. The in vivo study demonstrated that loss of ldtMt1 and ldtMt2 makes M. tuberculosis uniquely susceptible when exposed to a combination of amoxicillin-clavulanate and vancomycin. Although a less-than-desirable decline in bacterial burden was observed in the lungs of mice, sterilization of the spleen by 4 weeks of treatment suggests utility of this drug combination if l,d-transpeptidase activity is inhibited. Although these data merit further investigation, such investigation was beyond the scope of this study. We expect that the findings reported herein will facilitate further validation of l,d-transpeptidases as targets whose inhibition can usher in a new class of antibacterials with broad-spectrum activity.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Shaaretha Pelly and Leighanne A. Brammer Basta for constructive discussions and Mike Delanoy for technical assistance with electron microscopy.

This work was supported by NIH grants 1R56AI087749 and DP2OD008459 to G.L.

G.L. conceived the study, G.L. and M.K.S. designed the study, M.K.S. carried out the study, W.R.B. participated in discussions and provided material support, and G.L. and M.K.S. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 24 January 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.01396-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vollmer W, Holtje JV. 2004. The architecture of the murein (peptidoglycan) in gram-negative bacteria: vertical scaffold or horizontal layer(s)? J. Bacteriol. 186:5978–5987. 10.1128/JB.186.18.5978-5987.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wietzerbin J, Das BC, Petit JF, Lederer E, Leyh-Bouille M, Ghuysen JM. 1974. Occurrence of D-alanyl-(D)-meso-diaminopimelic acid and meso-diaminopimelyl-meso-diaminopimelic acid interpeptide linkages in the peptidoglycan of mycobacteria. Biochemistry 13:3471–3476. 10.1021/bi00714a008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crick DC, Brennan PJ. 2008. Biosynthesis of the arabinogalactan-peptidoglycan complex, p 25–40 In Daffe M, Reyrat J. (ed), The mycobacterial cell envelope. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tuomanen E, Cozens R. 1987. Changes in peptidoglycan composition and penicillin-binding proteins in slowly growing Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 169:5308–5310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caparros M, Pisabarro AG, de Pedro MA. 1992. Effect of D-amino acids on structure and synthesis of peptidoglycan in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 174:5549–5559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lavollay M, Arthur M, Fourgeaud M, Dubost L, Marie A, Veziris N, Blanot D, Gutmann L, Mainardi JL. 2008. The peptidoglycan of stationary-phase Mycobacterium tuberculosis predominantly contains cross-links generated by L,D-transpeptidation. J. Bacteriol. 190:4360–4366. 10.1128/JB.00239-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lavollay M, Fourgeaud M, Herrmann JL, Dubost L, Marie A, Gutmann L, Arthur M, Mainardi JL. 2011. The peptidoglycan of Mycobacterium abscessus is predominantly cross-linked by L,D-transpeptidases. J. Bacteriol. 193:778–782. 10.1128/JB.00606-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar P, Arora K, Lloyd JR, Lee IY, Nair V, Fischer E, Boshoff HI, Barry CE., III 2012. Meropenem inhibits D,D-carboxypeptidase activity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 86:367–381. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08199.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goffin C, Ghuysen JM. 2002. Biochemistry and comparative genomics of SxxK superfamily acyltransferases offer a clue to the mycobacterial paradox: presence of penicillin-susceptible target proteins versus lack of efficiency of penicillin as therapeutic agent. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66:702–738. 10.1128/MMBR.66.4.702-738.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flores AR, Parsons LM, Pavelka MS., Jr 2005. Characterization of novel Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium smegmatis mutants hypersusceptible to beta-lactam antibiotics. J. Bacteriol. 187:1892–1900. 10.1128/JB.187.6.1892-1900.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tuomanen E, Cozens R, Tosch W, Zak O, Tomasz A. 1986. The rate of killing of Escherichia coli by beta-lactam antibiotics is strictly proportional to the rate of bacterial growth. J. Gen. Microbiol. 132:1297–1304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walsh C. 2003. Antibiotics: actions, origins, resistance. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mainardi JL, Fourgeaud M, Hugonnet JE, Dubost L, Brouard JP, Ouazzani J, Rice LB, Gutmann L, Arthur M. 2005. A novel peptidoglycan cross-linking enzyme for a beta-lactam-resistant transpeptidation pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 280:38146–38152. 10.1074/jbc.M507384200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bielnicki J, Devedjiev Y, Derewenda U, Dauter Z, Joachimiak A, Derewenda ZS. 2006. B. subtilis ykuD protein at 2.0 A resolution: insights into the structure and function of a novel, ubiquitous family of bacterial enzymes. Proteins 62:144–151. 10.1002/prot.20702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biarrotte-Sorin S, Hugonnet JE, Delfosse V, Mainardi JL, Gutmann L, Arthur M, Mayer C. 2006. Crystal structure of a novel beta-lactam-insensitive peptidoglycan transpeptidase. J. Mol. Biol. 359:533–538. 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta R, Lavollay M, Mainardi JL, Arthur M, Bishai WR, Lamichhane G. 2010. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein LdtMt2 is a nonclassical transpeptidase required for virulence and resistance to amoxicillin. Nat. Med. 16:466–469. 10.1038/nm.2120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peltier J, Courtin P, El Meouche I, Lemee L, Chapot-Chartier MP, Pons JL. 2011. Clostridium difficile has an original peptidoglycan structure with a high level of N-acetylglucosamine deacetylation and mainly 3–3 cross-links. J. Biol. Chem. 286:29053–29062. 10.1074/jbc.M111.259150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanders AN, Pavelka MS. 2013. Phenotypic analysis of E. coli mutants lacking L,D-transpeptidases. Microbiology 159:1842–1852. 10.1099/mic.0.069211-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erdemli SB, Gupta R, Bishai WR, Lamichhane G, Amzel LM, Bianchet MA. 2012. Targeting the cell wall of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: structure and mechanism of L,D-transpeptidase 2. Structure 20:2103–2115. 10.1016/j.str.2012.09.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Both D, Steiner EM, Stadler D, Lindqvist Y, Schnell R, Schneider G. 2013. Structure of LdtMt2, an L,D-transpeptidase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 69:432–441. 10.1107/S0907444912049268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim HS, Kim J, Im HN, Yoon JY, An DR, Yoon HJ, Kim JY, Min HK, Kim SJ, Lee JY, Han BW, Suh SW. 2013. Structural basis for the inhibition of Mycobacterium tuberculosis L,D-transpeptidase by meropenem, a drug effective against extensively drug-resistant strains. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 69:420–431. 10.1107/S0907444912048998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li WJ, Li DF, Hu YL, Zhang XE, Bi LJ, Wang DC. 2013. Crystal structure of L,D-transpeptidase LdtMt2 in complex with meropenem reveals the mechanism of carbapenem against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell Res. 23:728–731. 10.1038/cr.2013.53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Correale S, Ruggiero A, Capparelli R, Pedone E, Berisio R. 2013. Structures of free and inhibited forms of the L,D-transpeptidase LdtMt1 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 69:1697–1706. 10.1107/S0907444913013085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cordillot M, Dubee V, Triboulet S, Dubost L, Marie A, Hugonnet JE, Arthur M, Mainardi JL. 2013. In vitro cross-linking of Mycobacterium tuberculosis peptidoglycan by l,d-transpeptidases and inactivation of these enzymes by carbapenems. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:5940–5945. 10.1128/AAC.01663-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valway SE, Sanchez MP, Shinnick TF, Orme I, Agerton T, Hoy D, Jones JS, Westmoreland H, Onorato IM. 1998. An outbreak involving extensive transmission of a virulent strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 338:633–639. 10.1056/NEJM199803053381001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barkan D, Rao V, Sukenick GD, Glickman MS. 2010. Redundant function of cmaA2 and mmaA2 in Mycobacterium tuberculosis cis cyclopropanation of oxygenated mycolates. J. Bacteriol. 192:3661–3668. 10.1128/JB.00312-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee MH, Pascopella L, Jacobs WR, Jr, Hatfull GF. 1991. Site-specific integration of mycobacteriophage L5: integration-proficient vectors for Mycobacterium smegmatis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and bacille Calmette-Guerin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 88:3111–3115. 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hatfull GF, Jacobs WR., Jr 2000. Some common methods in mycobacterial genetics, p 313–320 In Hatfull GF, Jacobs WR., Jr (ed), Molecular genetics of mycobacteria. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manganelli R, Dubnau E, Tyagi S, Kramer FR, Smith I. 1999. Differential expression of 10 sigma factor genes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 31:715–724. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01212.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cynamon MH, Speirs RJ, Welch JT. 1998. In vitro antimycobacterial activity of 5-chloropyrazinamide. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:462–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paul TR, Beveridge TJ. 1993. Ultrastructure of mycobacterial surfaces by freeze-substitution. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. 279:450–457. 10.1016/S0934-8840(11)80416-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hingley-Wilson SM, Sambandamurthy VK, Jacobs WR., Jr 2003. Survival perspectives from the world's most successful pathogen, Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Immunol. 4:949–955. 10.1038/ni981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Heijenoort J. 1996. Murein synthesis, p 1025–1034 In Neidhardt FC, Curtiss R, III, Ingraham JL, Lin ECC, Low KB, Magasanik B, Reznikoff WS, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger HE. (ed), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meroueh SO, Bencze KZ, Hesek D, Lee M, Fisher JF, Stemmler TL, Mobashery S. 2006. Three-dimensional structure of the bacterial cell wall peptidoglycan. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:4404–4409. 10.1073/pnas.0510182103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barksdale L, Kim KS. 1977. Mycobacterium. Bacteriol. Rev. 41:217–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neyrolles O, Hernandez-Pando R, Pietri-Rouxel F, Fornes P, Tailleux L, Barrios Payan JA, Pivert E, Bordat Y, Aguilar D, Prevost MC, Petit C, Gicquel B. 2006. Is adipose tissue a place for Mycobacterium tuberculosis persistence? PLoS One 1:e43. 10.1371/journal.pone.0000043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malen H, Berven FS, Fladmark KE, Wiker HG. 2007. Comprehensive analysis of exported proteins from Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. Proteomics 7:1702–1718. 10.1002/pmic.200600853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Covert BA, Spencer JS, Orme IM, Belisle JT. 2001. The application of proteomics in defining the T cell antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proteomics 1:574–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malen H, Softeland T, Wiker HG. 2008. Antigen analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv culture filtrate proteins. Scand. J. Immunol. 67:245–252. 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2007.02064.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mattow J, Schaible UE, Schmidt F, Hagens K, Siejak F, Brestrich G, Haeselbarth G, Muller EC, Jungblut PR, Kaufmann SH. 2003. Comparative proteome analysis of culture supernatant proteins from virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv and attenuated M. bovis BCG Copenhagen. Electrophoresis 24:3405–3420. 10.1002/elps.200305601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Souza GA, Leversen NA, Malen H, Wiker HG. 2011. Bacterial proteins with cleaved or uncleaved signal peptides of the general secretory pathway. J. Proteomics 75:502–510. 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kastrinsky DB, Barry CE. 2010. Synthesis of labeled meropenem for the analysis of M. tuberculosis transpeptidases. Tetrahedron Lett. 51:197–200. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.10.124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dubee V, Triboulet S, Mainardi JL, Etheve-Quelquejeu M, Gutmann L, Marie A, Dubost L, Hugonnet JE, Arthur M. 2012. Inactivation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis l,d-transpeptidase LdtMt1 by carbapenems and cephalosporins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:4189–4195. 10.1128/AAC.00665-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hugonnet JE, Tremblay LW, Boshoff HI, Barry CE, III, Blanchard JS. 2009. Meropenem-clavulanate is effective against extensively drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science 323:1215–1218. 10.1126/science.1167498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mainardi JL, Hugonnet JE, Gutmann L, Arthur M. 2011. Fighting resistant tuberculosis with old compounds: the carbapenem paradigm. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 17:1755–1756. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03699.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.England K, Boshoff HI, Arora K, Weiner D, Dayao E, Schimel D, Via LE, Barry CE., III 2012. Meropenem-clavulanic acid shows activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:3384–3387. 10.1128/AAC.05690-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.