Abstract

Chagas disease is endemic in Latin America and an emerging infectious disease in the United States. No effective treatments are available. The TcG1, TcG2, and TcG4 antigens are highly conserved in clinically relevant Trypanosoma cruzi isolates and are recognized by B and T cells in infected hosts. Delivery of these antigens as a DNA prime/protein boost vaccine (TcVac2) elicited lytic antibodies and type 1 CD8+ T cells that expanded upon challenge infection and provided >90% control of parasite burden and myocarditis in chagasic mice. Here we determined if peripheral blood can be utilized to capture the TcVac2-induced protection from Chagas disease. We evaluated the serum levels of T. cruzi kinetoplast DNA (TckDNA), T. cruzi 18S ribosomal DNA (Tc18SrDNA), and murine mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) as indicators of parasite persistence and tissue damage and monitored the effect of sera on macrophage phenotype. Circulating TckDNA/Tc18SrDNA and mtDNA were decreased by >3- to 5-fold and 2-fold, respectively, in vaccinated infected mice compared to nonvaccinated infected mice. Macrophages incubated with sera from vaccinated infected mice exhibited M2 surface markers (CD16, CD32, CD200, and CD206), moderate proliferation, a low oxidative/nitrosative burst, and a regulatory/anti-inflammatory cytokine response (interleukin-4 [IL-4] plus IL-10 > tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α]). In comparison, macrophages incubated with sera from nonvaccinated infected mice exhibited M1 surface markers, vigorous proliferation, a substantial oxidative/nitrosative burst, and a proinflammatory cytokine response (TNF-α ≫ IL-4 plus IL-10). Cardiac infiltration of macrophages and TNF-α and oxidant levels were significantly reduced in TcVac2-immunized chagasic mice. We conclude that circulating TcDNA and mtDNA levels and macrophage phenotype mediated by serum constituents reflect in vivo levels of parasite persistence, tissue damage, and inflammatory/anti-inflammatory state and have potential utility in evaluating disease severity and efficacy of vaccines and drug therapies.

INTRODUCTION

Trypanosoma cruzi, a parasitic protozoan, affects ∼13 million people in countries of Latin America where it is endemic (1). Approximately 30 to 40% of infected individuals eventually develop chronic Chagas disease manifested by cardiomyopathy and/or gastrointestinal involvement (2). It is a cause of significant morbidity and mortality in areas of endemicity in Mexico and Central and South America but also among immigrant residents in areas of the world where it is not endemic (3, 4). The globalization of Chagas disease has brought new challenges and opportunities for developing vaccines and drug therapies against T. cruzi infection and Chagas disease (5).

The current approach to testing the efficacy of vaccines or drugs has been the observation of suppression of acute parasitemia and tissue parasite burden and mortality rates postinfection (reviewed in references 6 and 7). This strategy provides quantitative measures of the efficacy of vaccines or drugs efficacy in experimental models, but it is not applicable to test the vaccine or drug efficacy in humans. Further, this approach is not useful for identifying chronically infected individuals who may be at risk of clinical disease development or to evaluate the treatment efficacy in chronic chagasic disease. The cure in chronic patients is routinely determined based upon the conversion to negative serology, which can take 8 to 10 years posttreatment (8) and occur in only ∼15% of treated adult subjects (9, 10). A lack of efficient tools to measure treatment efficacy or cure has prevented the testing of vaccines or new drugs in chagasic patients.

We have recently shown that prophylactic vaccination before challenge infection (11–14) or treatment of chronically infected experimental animals with the antiparasite drug benznidazole (15), which resulted in the host's ability to control acute parasitemia and tissue parasite burden (11–14), consequently prevented myocardial oxidative and inflammatory pathology (15–17) and led to preservation of the hemodynamic function of the heart (15). Because oxidative/inflammatory adducts result in cellular damage, we hypothesize that the damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) are released in the peripheral blood and can be captured by the phagocyte activation pattern.

In this study, our objective was to determine (i) whether serum/plasma samples carry the host's signature of inflammatory/oxidative disease state and can be captured by the in vitro activation profile of macrophages (Mϕ) and (ii) if the efficacy of a vaccine in control of tissue parasite burden and disease is reflected in the peripheral blood signature of Mϕ activation. Our data suggest that circulatory factors in chronically infected chagasic mice and those released by infected cardiomyocytes signal the activation and proliferation of proinflammatory Mϕ and phagocyte production of tissue-degrading enzymes. Vaccination (TcVac2)-induced control of chronic myocarditis was reflected by antiproliferative and anti-inflammatory responses of Mϕ to circulatory factors in vaccinated infected mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice, immunization, and challenge infection.

C57BL/6 female mice (6 to 8 weeks old) were obtained from Harlan Labs (Indianapolis, IN). Trypomastigotes of T. cruzi (SylvioX10) were maintained and propagated by continuous in vitro passage in C2C12 cells. Animal experiments were performed according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (18) and approved by the UTMB Animal Care and Use Committee.

The cDNAs for TcG1, TcG2, and TcG4 (from the SylvioX10 isolate; GenBank accession numbers AY727914, AY727915, and AY727917, respectively) were cloned in eukaryotic expression plasmid pCDNA3.1 (11). Plasmids encoding interleukin-12 (IL-12) (pcDNA3.msp35 and pcDNA3.msp40) and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (pCMVI.GM-CSF) have been previously described (19). Recombinant plasmids were transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α competent cells, grown in L broth containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin, and purified by anion-exchange chromatography using the Endo-free Qiagen maxiprep kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA). The cDNAs for TcG1, TcG2, and TcG4 were cloned in frame with a C-terminal His tag into the pET-22b plasmid (Novagen, Gibbstown, NJ). Plasmids were transformed in BL21(DE3) pLysS competent cells, and recombinant proteins purified using polyhistidine fusion peptide metal chelation chromatography were confirmed to be free of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) contamination (12, 19).

C57BL/6 mice were injected in the quadriceps muscle with TcVac2 vaccine, consisting of two doses of antigen- and cytokine-encoding plasmids (25 μg each plasmid DNA/mouse, intramuscular) and two doses of recombinant proteins (25 μg each protein emulsified in 5 μg saponin and 100 μl phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]/mouse, intradermal). All vaccine doses were delivered at 3-week intervals. Two weeks after the last immunization, mice were challenged with T. cruzi trypomastigotes (10,000/mouse). Mice were sacrificed at day 120 postinfection (p.i.), corresponding to the chronic disease phase, and serum/plasma and tissue samples were stored at −80°C.

Cardiomyocyte infection and spent medium.

HL-1 cardiomyocytes were mock treated or infected with T. cruzi (cell/parasite ratio, 1:10) for 48 h. Culture supernatants were centrifuged at 5,000 × g, and aliquots were stored at −80°C (20).

Circulating DNA levels.

Total DNA from plasma samples was isolated using the QIAamp circulating nucleic acid kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA), according to instructions provided by the manufacturer. Circulating plasma DNA (50 ng) was used as a template, and real-time PCR was performed on an iCycler thermal cycler with SYBR green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and oligonucleotide pairs specific for T. cruzi kinetoplast DNA (TckDNA) (forward, 5′-GGGTTCGATTGGGGTTGGTGT-3′; reverse, 5′-AAATAATGTACGGGG/TGAGATGCATGA-3′) and T. cruzi 18S ribosomal DNA (Tc18SrDNA) (forward, 5′-TAGTCATATGCTTGTTTC-3′; reverse, 5′-GCAACAGCATTAATATACGC-3′). Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) (GenBank accession number J01420) was amplified using the primers (forward, 5′-ACCATTTGCAGACGCCATAA-3′; reverse, 5′-TGAAATTGTTTGGGCTACGG-3′) that specifically bind to mtDNA and not the mtDNA-like sequence present in the nuclear genome (21). Data were normalized to the murine GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) gene (forward, 5′-TGTGATGGGTGTGAACCACGAGA-3′; reverse, 5′-GAGCCCTTCCACAATGCCAAAGT-3′), and fold change was calculated as 2−ΔΔCT, where ΔCT represents CT (sample) − CT (control) (22).

Treatment of Mϕ with serum samples.

THP-1 human monocytes were differentiated into Mϕ by overnight incubation with 50 ng/ml phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA) and then rested at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 48 h in RPMI complete medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). THP-1 (human) or RAW264.7 (murine) Mϕ were distributed in 48-well plates (4 × 105/well/300 μl) and incubated for 24 h in the presence of 10% serum from normal, infected, and vaccinated infected mice. Culture supernatants and cells were stored at −80°C.

Mϕ proliferation and surface markers.

Macrophages were in vitro stimulated with serum samples for 24 h as described above except that alamarBlue (10% final concentration; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was added during incubation. The reduction of alamarBlue by viable, metabolically active cells to fluorescent resorufin (excitation, 560 nm; emission, 590 nm) was monitored using a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Surface expression of markers of activation and functional phenotype was monitored by flow cytometry. Briefly, THP-1 Mϕ were in vitro stimulated for 24 h with serum samples or for 4 days with recombinant human cytokines (50 ng/ml gamma interferon [IFN-γ], 20 ng/ml IL-4, and 20 ng/ml IL-10; Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) (23). Cells were washed and then labeled for 30 min on ice with human fluorescence-conjugated peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP)/Cy5.5 anti-CD14, phycoerythrin (PE)/Cy5 anti-CD80, PE/Cy7 anti-CD64, allophycocyanin (APC)/Cy7 anti-CD16, PE anti-CD163, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) anti-CD32, Pacific blue anti-CD200, and APC anti-CD206 antibodies (prediluted, 5 to 20 μl/test; BD Biosciences, CA, USA). Stained cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and visualized on an LSRII Fortessa Cell Analyzer by six-color flow cytometry, acquiring 30 to 50,000 events in a live cell gate, and further analysis was performed using FlowJo software (version 7.6.5; TreeStar, San Carlo, CA). Cells stained with isotype-matched IgGs were used as controls.

Cytokine release.

Culture supernatants of Mϕ incubated with sera from vaccinated infected mice and control mice were utilized for the measurement of cytokine release (IL-4, IL-10, IFN-γ, and TNF-α) using optEIA enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), according to the manufacturer's specifications.

Oxidative and nitrosative burst.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) were monitored by using fluorescent probes from Invitrogen. Briefly, Mϕ were incubated with 5-μM chloromethyl 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA), and its oxidation by intracellular ROS, resulting in the formation of fluorescent dichlorodihydrofluorescein (excitation, 498 nm; emission, 598 nm), was measured by fluorimetry (24). For in situ ROS detection, 10-μm cryostat tissue sections were equilibrated in Kreb's buffer and incubated in dark for 30 min with 5 μM dihydroethidium (DHE). DHE, when oxidized, converts to dihydroethidium (intercalates nuclear DNA) and emits bright red fluorescence (excitation, 518 nm; emission, 605 nm) (15). Fluorescence was detected on a BX-53 microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA), and images were captured by using a mounted digital camera.

The NO level (an indicator of inducible nitric oxide synthase [iNOS] activity) was monitored by assaying total nitrite in supernatants by the Greiss assay. Briefly, samples were incubated for 10 min with 100 μl of 1% sulfanilamide made in 5% phosphoric acid–0.1% N-(1-napthyl) ethylenediamine dihydrochloride (1:1, vol/vol). Formation of diazonium salt was monitored at 545 nm (standard curve, 0 to 100 μM sodium nitrite).

MMP2/MMP9 assay.

We measured matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP2)/MMP9 activity by using the InnoZyme gelatinase activity assay kit (Calbiochem, Billerica, MA). Briefly, supernatants of cultured Mϕ treated with serum samples from vaccinated infected mice and control mice were diluted in activation buffer (1:3, vol/vol) and incubated for 3 h with thiopeptide substrate specific for type IV collagenases (MMP2/gelatinase A and MMP9/gelatinase B). The cleavage of the substrate by MMP2/MMP9 in the presence or absence of p-aminophenylmercuric acetate (an activator of proenzyme MMP2/MMP9), resulting in the release of fluorescence (excitation, 320 nm; emission, 405 nm) was monitored by fluorimetry.

Immunohistochemistry.

To visualize in situ Mϕ population, paraffin-embedded 5-μm tissue sections (3 slides/mouse, n = 4/group) were deparaffinized and incubated sequentially with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 20% acetic acid (to block nonspecific activity). Tissue sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with mouse monoclonal-anti-Mac-1 or rabbit anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (1:50 dilution; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) antibodies. After washing, slides were incubated at room temperature for 1 h each with biotinylated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG (1:100 dilution) and streptavidin-conjugated alkaline phosphatase, and color was developed with a Red AP (for Mac-1) or 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate–nitroblue tetrazolium (BCIP-NBT) (for TNF-α) kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). All slides were counterstained with methyl green (which stains nuclei). The number of Mϕ per microscopic field (mf) was calculated by counting Mac-1+ cells (identified by a partial or complete ring of pink color outlining the cell membrane) in the heart and skeletal muscle tissue sections, and the mean of the total cells per microscopic field (>5 mfs/slide) was calculated (25). Tissue sections were scored for TNF-α staining and DHE fluorescence as a percentage of total histological field quantified by using Simple PCI software (version 6.0; Compix, Sewickly, PA) (12, 14).

Data analysis.

All in vitro and in vivo experiments were conducted with triplicate observations per sample (n = 8 mice/group), and data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). All data were analyzed using InStat version 3 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA) or SPSS version14.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Data were tested to be normally distributed by histogram and Q-Q methods. Normally distributed data were analyzed by the Student t test (for comparison of 2 groups) and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's post hoc test (for comparison of multiple groups). Data sets that were found not to be normally distributed were analyzed with the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Mann-Whitney test to assess the differences between pairwise comparisons. Significance is shown as follows: * or #, P < 0.05; ** or ##, P < 0.01; *** or ###, P < 0.001 (*, normal versus infected, vaccinated infected, or cytokine treated; #, infected versus vaccinated infected).

RESULTS

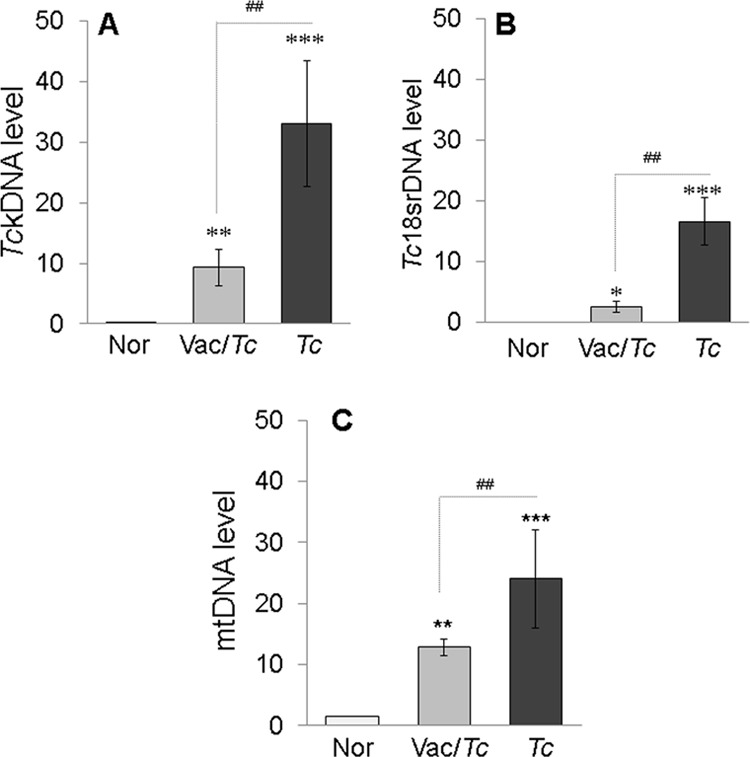

We first determined if TcVac2-induced control of parasite burden and tissue damage, documented by us in a previous study (12), is reflected in circulation. For this, total DNA isolated from sera of vaccinated infected and control mice was analyzed by real-time PCR for high-copy-number parasite and host DNAs. We found that the circulating levels of TckDNA and Tc18SrDNA were significantly increased in nonvaccinated infected mice, and were controlled by >3- to 5-fold in vaccinated infected mice (Fig. 1A and B) (all P < 0.01 by the Kruskal-Wallis test). Likewise, circulating levels of murine mtDNA, measured as a marker of host cellular injury and death, were significantly increased in nonvaccinated infected mice and were controlled by >2-fold in vaccinated infected mice (Fig. 1C) (P < 0.01 by the Kruskal-Wallis test). These data suggested that the circulating TcDNA and host mtDNA provide an indication of the host's in vivo state and capture the vaccine's efficacy in reducing parasite persistence and tissue damage.

FIG 1.

Serum levels of T. cruzi and host DNAs in chagasic mice (with or without TcVac2 vaccination). Mice were vaccinated with TcVac2 as detailed in Materials and Methods and 2 weeks after the last immunization were infected with T. cruzi (10,000 trypomastigotes per mouse). Serum samples were collected at day 120 postinfection, corresponding to the chronic disease phase. Total DNA isolated from serum samples was subjected to real-time PCR for T. cruzi kDNA (A), the T. cruzi 18S rDNA sequence (B), and the murine mtDNA sequence (C). Data were normalized to the murine GAPDH gene. In all figures, data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 8/group, triplicate observations/sample), and significance is presented for normal versus infected or vaccinated infected (*) and for infected versus vaccinated infected (#) (*, P < 0.05; ** and ##, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

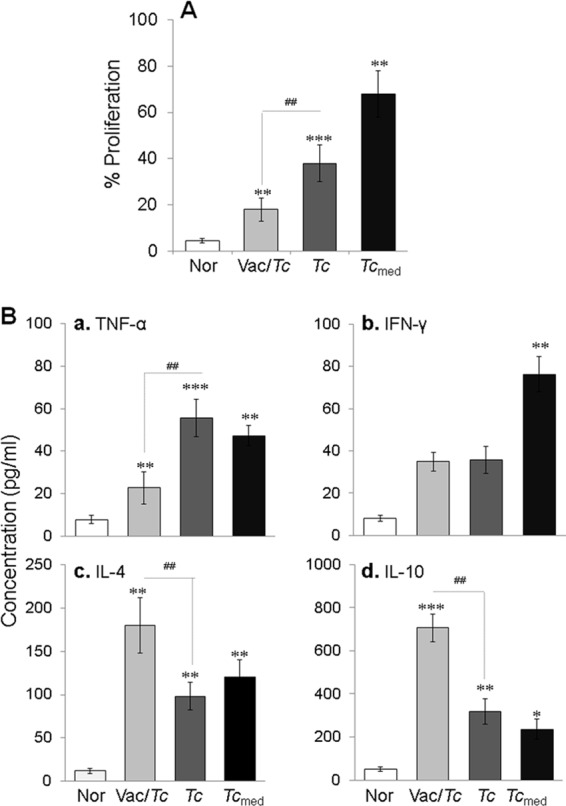

To assess the peripheral signature of vaccine's efficacy via Mϕ responses, we incubated the cultured Mϕ with serum samples from vaccinated infected and nonvaccinated infected mice and first examined the Mϕ proliferation and cytokine response (Fig. 2). Our data showed that the incubation of Mϕ with sera from vaccinated infected mice resulted in a low level of proliferation (Fig. 2A) (P < 0.01 to 0.001 by ANOVA) that was associated with a predominant release of type 2 cytokines (IL-4 plus IL-10 ≫ TNF-α plus IFN-γ) compared to normal controls (Fig. 2B, panels a, b, and d [P < 0.01 to 0.001 by ANOVA] and panel c [all P < 0.01 by the Kruskal-Wallis test]). In contrast, incubation with sera from nonvaccinated infected mice or medium from infected cardiomyocytes resulted in a prolific macrophage proliferation that was 2- to 3-fold higher than that noted for Mϕ incubated with sera from vaccinated infected mice (Fig. 2A) (P < 0.01 to 0.001 by ANOVA). Further, Mϕ incubated with sera from infected mice or spent medium from infected cardiomyocytes exhibited up to 3-fold and 2-fold increases in TNF-α and IFN-γ release, respectively, and 2-fold and 3-fold declines in IL-4 and IL-10 release, respectively, compared to that noted in supernatants of Mϕ incubated with sera from vaccinated infected mice (Fig. 2B, panels a, b, and d [P < 0.01 to 0.001 by ANOVA] and panel c [P < 0.01 by the Kruskal-Wallis test]). These data suggested that (i) circulatory factors in chronically infected chagasic mice and those released by infected cardiomyocytes signal the proliferation and activation of proinflammatory Mϕ and (ii) the vaccine-induced control of chronic myocarditis is reflected by the antiproliferative and anti-inflammatory response of Mϕ.

FIG 2.

Proliferation and cytokine release by Mϕ in response to chagasic sera (with or without TcVac2 vaccination). Mϕ were incubated with serum samples for 48 h. (A) Macrophage proliferation determined by alamarBlue assay. (B) The TNF-α (a), IFN-γ (b), IL-4 (c), and IL-10 (d) levels in cell-free supernatants were measured by an ELISA. See Fig. 1 for the definition of symbols.

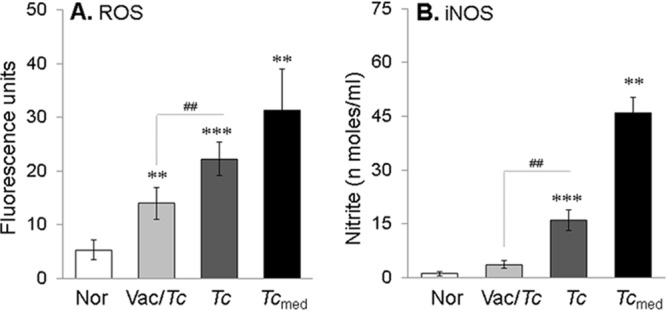

Mϕ produce O2− from NADPH oxidase (NOX2) activity and NO from iNOS activation, and this oxidative/nitrosative burst is an important indicator of phagocyte cytotoxicity. Our data showed that intracellular ROS and NO release was increased by 4.2 to 5.9 and >15-fold, respectively, in Mϕ incubated with sera from nonvaccinated infected mice or spent medium from cardiomyocytes in vitro infected with T. cruzi for 48 h compared to that noted with normal controls (Fig. 3A and B) (P < 0.01 to 0.001 by ANOVA). In comparison, the intracellular ROS level was decreased by >2-fold in Mϕ incubated with sera from vaccinated infected mice (Fig. 3A) (P < 0.01 by ANOVA), and NO release was merely detectable in the supernatants of Mϕ incubated with sera from vaccinated infected mice (Fig. 3B) (P < 0.01 by ANOVA). These data suggested that circulatory factors in chronically infected chagasic mice signal the Mϕ activation of the NOX2- and iNOS-dependent oxidative and nitrosative burst and that the proinflammatory circulatory factors were absent in the sera of vaccinated infected mice, resulting in a control of cytotoxic responses by macrophages.

FIG 3.

Chagasic sera elicit an oxidative/nitrosative burst in Mϕ (with or without TcVac2 vaccination). Mϕ were cultured for 24 h in the presence of serum samples from infected and vaccinated infected mice. (A) H2DCFDA oxidation by intracellular ROS was monitored by fluorimetry. (B) Nitrate/nitrite levels in the supernatants as determined by Greiss reagent assay. See Fig. 1 for the definition of symbols.

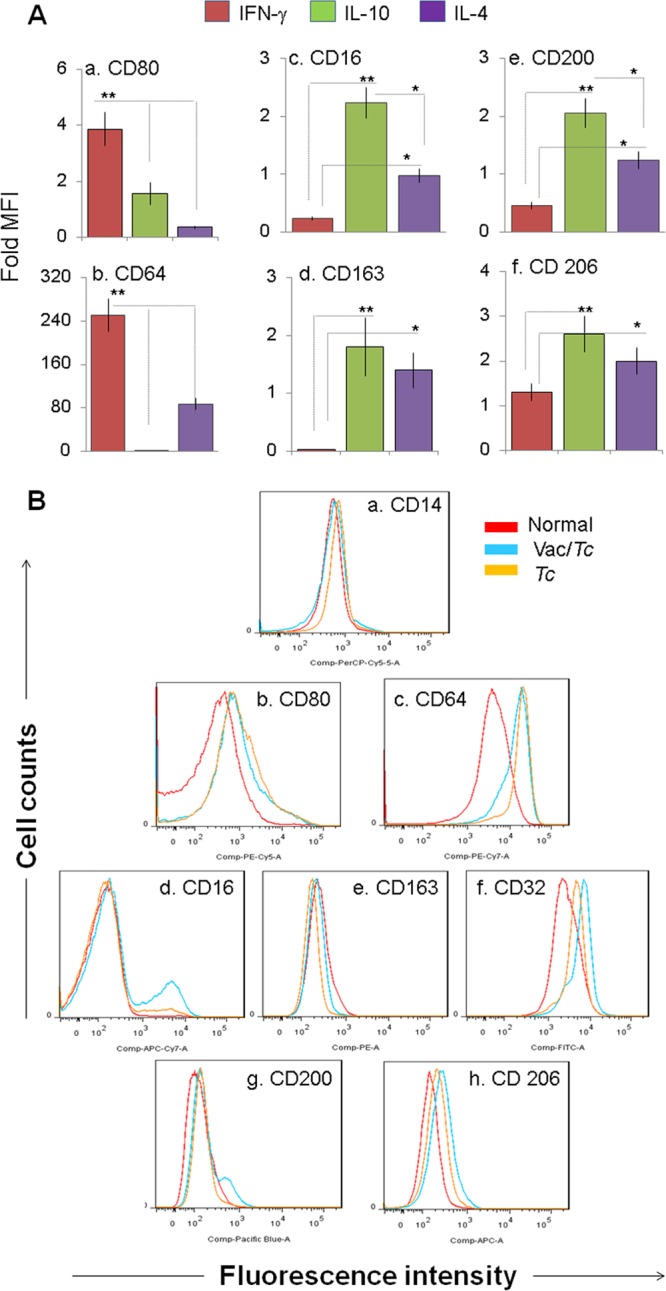

Next, we determined if the proinflammatory versus anti-inflammatory activation profile correlated with surface expression of physiological indicators of Mϕ phenotype. We first investigated the relative expression of a broad panel of surface molecules by flow cytometry after 4 days of in vitro polarization of human THP-1 monocytes with IFN-γ, IL-4, or IL-10. IFN-γ-treated Mϕ displayed a robust and specific upregulation of the costimulatory molecule CD80 and the high-affinity Fcγ receptor I (CD64) compared to the unpolarized and IL-4- or IL-10-polarized Mϕ (Fig. 4A, panels a and b) (all P < 0.01 by ANOVA). In comparison to IFN-γ-treated Mϕ, IL-10-treated Mϕ showed a high level of upregulation of the Fcγ receptor III (CD16), the scavenger receptor CD163, and the inhibitory receptors CD200 and CD206 (Fig. 4A, panels c to f) (all P < 0.01 by ANOVA). The IL-4-treated Mϕ also exhibited a significant increase in CD16+, CD163+, CD200+, and CD206+ phenotype compared to that noted in IFN-γ-treated Mϕ (Fig. 4A, panels c to f) (all P < 0.05 to 0.01 by ANOVA); however, the extent of expression of CD16 and CD200 markers was much lower than that observed in IL-10-treated Mϕ (Fig. 4A, panels c and e) (all P < 0.05 to 0.01 by ANOVA). These data suggested that CD80/CD64 are robust phenotypic markers for MϕIFN-γ, the CD16hi/CD200hi profile was MϕIL-10 specific, the CD16lo/CD200lo profile was MϕIL-4 specific, and the CD163+/CD206+ phenotype was associated with both MϕIL-10 and MϕIL-4.

FIG 4.

Expression of phenotypic markers on Mϕ polarized with chagasic sera (with or without TcVac2 vaccination). (A) THP-1 monocytes were in vitro cultured in medium supplemented with IFN-γ, IL-4, or IL-10. The polarized subsets were examined for surface expression of CD80 and CD64 for the MϕIFN-γ phenotype (a and b) and for CD163, CD16, CD200, and CD206 for the Mϕ IL-10/IL-4 phenotype (c to f) by flow cytometry. (B) THP-1 monocytes were in vitro treated with serum samples from normal (red), vaccinated infected (blue), and nonvaccinated infected (yellow) mice. Shown are flow cytometry analyses for surface expression of IFN-γ-, IL-10-, and IL-4-inducible phenotypic markers. See Fig. 1 for the definition of symbols.

The surface marker profile of Mϕ incubated with sera from vaccinated infected or nonvaccinated infected mice is shown in Fig. 4B and in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material. We noted a distinct and statistically significant increase in surface expression of IL-10- and/or IL-4-inducible CD16, CD32, CD200, and CD206 in Mϕ incubated with sera from vaccinated infected mice compared to that noted upon incubation with sera from nonvaccinated infected mice (Fig. 4B panels d to h; see Fig. S1d to h in the supplemental material) (all P < 0.05 to 0.01 by ANOVA). A similar level of increase in the frequency of Mϕ exhibiting the IFN-γ-inducible proinflammatory phenotype (CD80 and CD64) was noted with sera from vaccinated infected and nonvaccinated infected mice (see Fig. S1b and c in the supplemental material). These data showed the vaccinated mice that control chronic myocarditis exhibit a peripheral signature of repair/immunoregulatory Mϕ. In comparison, immunopathology and tissue damage in chronic Chagas disease was presented by ex vivo inflammatory programming of Mϕ.

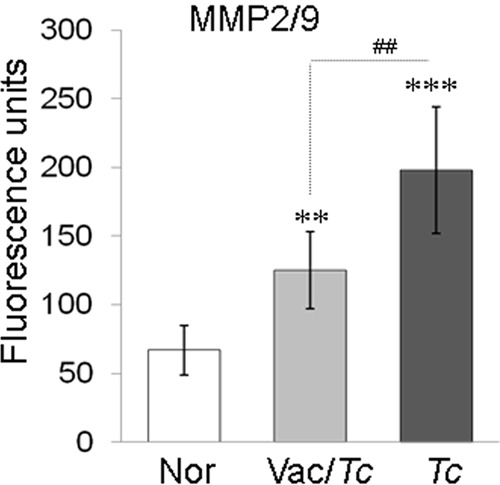

Metalloproteinases and cysteine proteases are employed by Mϕ to cleave and activate chemokines to attract other inflammatory cells and degrade the extracellular matrix (ECM) to gain entry into tissues. Increased expression of MMP2/MMP9 and cathepsin B in chagasic hearts had been noted (26) and implicated in ECM degradation, gradual slippage of ventricular layers, and formation of an apical aneurysm in the heart, a hallmark of disease (27, 28). Macrophages incubated with sera from chronically infected mice exhibited a 3-fold increase in MMP2/MMP9 activity compared to that in normal controls (Fig. 5) (P < 0.001 by ANOVA). In comparison, incubation of Mϕ with sera from vaccinated infected mice resulted in a >70% decline in MMP2/MMP9 activity (Fig. 5) (P < 0.01 by ANOVA). These data suggested that production of tissue-degrading enzymes by phagocytes is elicited by soluble factors present in sera of chagasic mice and that this response is significantly controlled with TcVac2-dependent control of Chagas disease.

FIG 5.

Macrophage MMP2/MMP9 activity in response to chagasic sera (with or without TcVac2 vaccination). Mϕ were incubated with serum samples for 48 h. Cell-free supernatants were utilized to measure MMP-2/MMP-9 activity. See Fig. 1 for the definition of symbols.

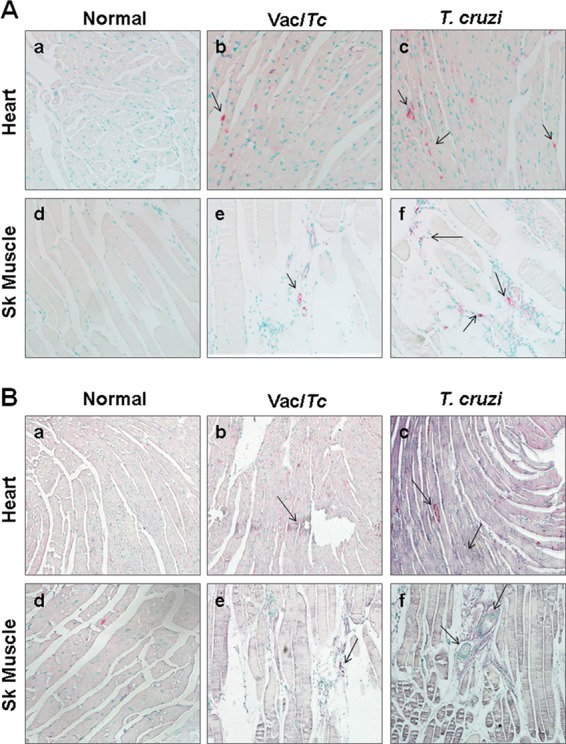

Finally, we scored the extent of Mϕ infiltration and proinflammatory cytokine (TNF-α) and oxidative responses in the hearts and skeletal tissues of vaccinated infected and nonvaccinated infected mice during the chronic disease phase to enumerate the impact of proinflammatory Mϕ in the disease process. Immunohistochemistry with anti-mac1 antibody (Mϕ marker) showed that the Mϕ infiltration was significantly decreased in the hearts (5 ± 1.2 versus 10 ± 2 Mϕ/mf; P < 0.05 by ANOVA) and skeletal muscles (6 ± 1 versus 18 ± 2.2 Mϕ/mf; P < 0.01 by ANOVA) of vaccinated chronically infected mice compared to nonvaccinated chronically infected mice (Fig. 6A, compare panels b and c and panels e and f). Most of the infiltrating macrophages in the myocardia of nonvaccinated chronically infected mice were TNF-α positive (Fig. 6B, panels c and f, arrows). We noted a significant decline in myocardial (10% versus 60% of total area; P < 0.001 by ANOVA) and skeletal muscle (25% versus 62% of total area; P < 0.05 by ANOVA) levels of TNF-α in vaccinated chronically infected mice compared to nonvaccinated chronically infected mice (Fig. 6B, compare panels b and c and panels e and f). In situ staining with DHE showed that the ROS level was decreased by >2-fold (30% versus 82% of total area; P < 0.001 by ANOVA) in the myocardia of vaccinated infected mice compared to nonvaccinated infected mice (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). These data suggested that TcVac2 control of parasite and associated tissue damage was reflected by a significant decline in myocardial infiltration of macrophages and proinflammatory cytokine and ROS production in vaccinated infected mice.

FIG 6.

In vivo macrophage infiltration and cytokine response in chagasic mice (with or without TcVac2 vaccination). Paraffin-embedded tissue sections were subjected to immunostaining with antibodies against Mϕ (pink color) and TNF-α (blue color). (A) Immunostaining with anti-Mac-1 antibody (arrows indicate the abundance of Mac-1-stained Mϕ). (B) Immunostaining with Mac-1/anti-TNF-α antibodies (arrows indicate the gray/blue staining of TNF-α+ macrophages. Shown are representative micrographs from hearts and skeletal tissues of normal (a and d), vaccinated infected (b and e), and nonvaccinated infected (c and f) mice.

DISCUSSION

We have previously shown that immunization of mice with TcVac2 (DNA prime/protein boost) subunit vaccine, consisting of TcG1, TcG2, and TcG4 antigenic candidates, provided resistance to T. cruzi infection. Mice immunized with TcVac2 responded to T. cruzi infection with a rapid and potent expansion of type 1 antibodies, CD8+ T cells, and proinflammatory cytokines that effectively controlled the acute parasitemia and tissue parasite burden. Consequently, evolution of chronic immunopathology and tissue damage, an outcome of parasite persistence and consistent immune activation, was absent in vaccinated mice (12).

Our data in the present study demonstrate that the DNA signature of peripheral blood provides cues to the vaccine-induced control of parasite burden and tissue damage. Sera from mice vaccinated with TcVac2 exhibited a significant decline in circulating levels of high-copy-number TckDNA and Tc18SrDNA in the chronic phase of infection (Fig. 1A and B), similarly to what we have previously noted in heart and skeletal muscle biopsy specimens from vaccinated infected mice (12). The mtDNA copy number is substantively high in the heart (>500 copies/cardiomyocyte). Our finding of an increase in serum mtDNA level (Fig. 1C) with a corresponding decline in myocardial mtDNA content in chagasic mice (unpublished data) and humans (29) suggests that the circulating mtDNA can be used as a marker of cellular injury and death. This notion is supported by the observation that TcVac2-immunized mice, which were equipped to control T. cruzi-induced chronic tissue necrosis and injury (12), also exhibited low levels of mtDNA in circulation (Fig. 1C).

The persistence of inflammatory responses associated with tissue fibrosis and cell death is a hallmark of chronic Chagas disease. We have found that Mϕ present in chagasic hearts (Fig. 6) as well as those in vitro exposed to sera from chagasic mice (or spent medium from T. cruzi-infected cardiomyocytes) polarized toward a proinflammatory phenotype (CD64hi CD80hi) (Fig. 4) with extensive production of TNF-α/IFN-γ cytokines (Fig. 2) and MMP2/MMP-9 tissue-degrading enzymes (Fig. 5). In comparison, TcVac2-induced protection from parasite persistence and inflammation (12) was presented by a significant decline in the TNF-α+ Mϕ population in the heart and reflected by M2 polarization of Mϕ (CD200+, CD206+, CD16+, CD32+, IL-4, and IL-10 producing) upon in vitro incubation with sera from TcVac2-vaccinated infected mice (Fig. 4 and 6). Others have shown that the early production of type 1 cytokines (IFN-γ and TNF-α) correlates with resistance to T. cruzi infection (30–32), while a complete absence or deficiency of immunoregulatory cytokines (e.g., IL-10) can result in uncontrolled inflammatory pathology in the infected host (33, 34). Increased peripheral blood levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α (35–38) and increased production of IFN-γ by peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (39) have been correlated with clinical disease in chagasic patients, while a predominance of IL-10-producing PBMCs was noted in seropositive subjects in indeterminate phase (39). These studies point to the importance of both inflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses during different phases of T. cruzi infection and disease development and suggest that in vitro polarization of Mϕ with serum samples provides an easy tool to assess the disease state and the efficacy of vaccines and drug therapies against T. cruzi and Chagas disease, to be validated in future studies.

The current literature strongly suggests that intraphagosomal survival of T. cruzi from ROS and NO, which are produced by activation of NOX2 and iNOS, respectively, and promote peroxynitrite-mediated killing, is key to the parasite's existence in the host (reviewed in reference 40). A persistence of oxidative stress in chronic chagasic hearts when the parasite burden is present at the minimal level has also been noted (15, 17) and suggested to intensify cardiomyocyte necrosis and cardiac contractile dysfunction (reviewed in reference 41). Our observation of activation of the oxidative/nitrosative burst along with a proinflammatory cytokine response and tissue migratory properties in Mϕ incubated with sera of chagasic mice provides the first indication that a feedback cycle of Mϕ activation by circulatory factors might contribute to chronic inflammation and oxidative damage in Chagas disease. The finding of mild to no activation of the oxidative/nitrosative burst in Mϕ incubated with sera from vaccinated infected mice further supports this notion and suggests that therapies capable of reprogramming the macrophages toward an immunoregulatory/anti-inflammatory phenotype will be beneficial in preventing the progression of oxidative and inflammatory pathology in Chagas disease.

Damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) are released from cells during tissue injury and can act as “alarmins” (42) to activate innate immune cells through the engagement of Toll-like (43) and Nod-like (44) receptors. Bacterial and viral DNA molecules have been shown to be recognized by Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3), TLR7, and TLR9 and to activate AIM2 inflammasome-dependent IL-1β production (45). TLR3−/−, TLR7−/−, and TLR9−/− mice are susceptible to T. cruzi infection, and it has been suggested that DNA-dependent TLRs/MYD88 play an important role in bridging innate to acquired immunity in the context of control of T. cruzi infection (46). We propose that circulating parasite DNA and host mtDNA mediate chronic inflammatory responses in chagasic disease via activation of inflammatory macrophages. This notion is supported by the observation of an increase in circulating DNA levels (Fig. 1) and enhanced activation of inflammatory macrophages by serum components of chagasic mice (Fig. 2 to 4). A substantial infiltration of TNF-α-producing macrophages was also noted in chagasic hearts (Fig. 6). Importantly, circulating DNA levels as well as serum-mediated inflammatory activation of macrophages and myocardial infiltration of TNF-α+ macrophages were significantly decreased in TcVac2-immunized mice. Future studies evaluating the composition of circulating DNA and its role in activation of inflammatory responses will provide insights into the pathological significance of circulating DNA in chronic severity of Chagas disease.

In summary, our data suggest that circulatory factors in chronically infected chagasic mice and those released by infected cardiomyocytes signal the proliferation and activation of proinflammatory Mϕ that contribute to tissue damage presented during chronic Chagas disease. Vaccination with TcVac2 controlled the chronic tissue damage in chagasic mice, and this was reflected by antiproliferative and anti-inflammatory responses of Mϕ. Our results provide impetus to assess the potential utility of in vitro phenotypic and functional profiling of macrophages in response to circulatory factors in diagnosing the severity of clinical disease and monitoring the efficacy of drugs and vaccines in providing cure from infection and chronic disease in Chagas disease patients.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) (2R01AI05478) and the National Heart Lung Blood Institute (R01HL094802) of the National Institutes of Health to N.J.G. J.E.O. was a recipient of summer internship from NIAID T35 training grant AI078878 (principal investigator, Lynn Soong). T.S.S. and L.T. were recipients of a fellowship from the Summer Undergraduate Research Program of the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences at UTMB. S.G. was a recipient of a Sealy Center for Vaccine Development (SCVD) postdoctoral fellowship.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 13 January 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.01186-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. 2010. Chagas disease control and elimination. Report of the secretariat. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA63/A63_17-en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rassi A, Jr, Rassi A, Marin-Neto JA. 2010. Chagas disease. Lancet 375:1388–1402. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60061-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bern C, Kjos S, Yabsley MJ, Montgomery SP. 2011. Trypanosoma cruzi and Chagas' disease in the United States. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 24:655–681. 10.1128/CMR.00005-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basile L, Jansa JM, Carlier Y, Salamanca DD, Angheben A, Bartoloni A, Seixas J, Van Gool T, Canavate C, Flores-Chavez M, Jackson Y, Chiodini PL, Albajar-Vinas P. 2011. Chagas disease in European countries: the challenge of a surveillance system. Euro Surveill. 16(37):pii=19968 http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=19968 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanowitz HB, Weiss LM, Montgomery SP. 2011. Chagas disease has now gone global. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 5:e1136. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhatia V, Wen J-J, Zacks MA, Garg NJ. 2009. American trypanosomiasis and perspectives on vaccine development, p 1407–1434 In Stanberry LR, Barrett AD. (ed), Vaccines for biodefense and emerging and neglected diseases. Academic Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vázquez-Chagoyán JC, Gupta S, Garg NJ. 2011. Vaccine development against Trypanosoma cruzi and Chagas disease. Adv. Parasitol. 75:121–146. 10.1016/B978-0-12-385863-4.00006-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cancado JR. 1999. Criteria of Chagas disease cure. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 94(Suppl 1):331–335. 10.1590/S0074-02761999000700064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Viotti R, Vigliano C, Lococo B, Bertocchi G, Petti M, Alvarez MG, Postan M, Armenti A. 2006. Long-term cardiac outcomes of treating chronic Chagas disease with benznidazole versus no treatment: a nonrandomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 144:724–734. 10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fabbro DL, Streiger ML, Arias ED, Bizai ML, del Barco M, Amicone NA. 2007. Trypanocide treatment among adults with chronic Chagas disease living in Santa Fe city (Argentina), over a mean follow-up of 21 years: parasitological, serological and clinical evolution. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 40:1–10. 10.1590/S0037-86822007000100001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhatia V, Sinha M, Luxon B, Garg NJ. 2004. Utility of Trypanosoma cruzi sequence database for the identification of potential vaccine candidates: In silico and in vitro screening. Infect. Immun. 72:6245–6254. 10.1128/IAI.72.11.6245-6254.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta S, Garg NJ. 2010. Prophylactic efficacy of TcVac2 against Trypanosoma cruzi in mice. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 4:e797. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta S, Garg NJ. 2012. Delivery of antigenic candidates by a DNA/MVA heterologous approach elicits effector CD8(+)T cell mediated immunity against Trypanosoma cruzi. Vaccine 30:7179–7186. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.10.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta S, Garg NJ. 2013. TcVac3 induced control of Trypanosoma cruzi infection and chronic myocarditis in mice. PLoS One 8:e59434. 10.1371/journal.pone.0059434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wen JJ, Gupta S, Guan Z, Dhiman M, Condon D, Lui C, Garg NJ. 2010. Phenyl-alpha-tert-butyl-nitrone and benzonidazole treatment controlled the mitochondrial oxidative stress and evolution of cardiomyopathy in chronic chagasic rats. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 55:2499–2508. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wen JJ, Garg N. 2004. Oxidative modification of mitochondrial respiratory complexes in response to the stress of Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 37:2072–2081. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wen JJ, Dhiman M, Whorton EB, Garg NJ. 2008. Tissue-specific oxidative imbalance and mitochondrial dysfunction during Trypanosoma cruzi infection in mice. Microbes Infect. 10:1201–1209. 10.1016/j.micinf.2008.06.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Research Council. 2011. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals, 8th ed. National Academies Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhatia V, Garg NJ. 2008. Previously unrecognized vaccine candidates control Trypanosoma cruzi infection and immunopathology in mice. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 15:1158–1164. 10.1128/CVI.00144-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petersen CA, Burleigh BA. 2003. Role for interleukin-1 beta in Trypanosoma cruzi-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Infect. Immun. 71:4441–4447. 10.1128/IAI.71.8.4441-4447.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parfait B, Rustin P, Munnich A, Rotig A. 1998. Co-amplification of nuclear pseudogenes and assessment of heteroplasmy of mitochondrial DNA mutations. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 247:57–59. 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garg NJ, Bhatia V, Gerstner A, deFord J, Papaconstantinou J. 2004. Gene expression analysis in mitochondria from chagasic mice: alterations in specific metabolic pathways. Biochem. J. 381:743–752. 10.1042/BJ20040356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rey-Giraud F, Hafner M, Ries CH. 2012. In vitro generation of monocyte-derived macrophages under serum-free conditions improves their tumor promoting functions. PLoS One 7:e42656. 10.1371/journal.pone.0042656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ba X, Gupta S, Davidson M, Garg NJ. 2010. Trypanosoma cruzi induces the reactive oxygen species-PARP-1-RelA pathway for up-regulation of cytokine expression in cardiomyocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 285:11596–11606. 10.1074/jbc.M109.076984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dhiman M, Garg NJ. 2011. NADPH oxidase inhibition ameliorates Trypanosoma cruzi-induced myocarditis during Chagas disease. J. Pathol. 225:583–596. 10.1002/path.2975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gutierrez FR, Lalu MM, Mariano FS, Milanezi CM, Cena J, Gerlach RF, Santos JE, Torres-Duenas D, Cunha FQ, Schulz R, Silva JS. 2008. Increased activities of cardiac matrix metalloproteinases matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 and MMP-9 are associated with mortality during the acute phase of experimental Trypanosoma cruzi infection. J. Infect. Dis. 197:1468–1476. 10.1086/587487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fares RC, Gomes JD, Garzoni LR, Waghabi MC, Saraiva RM, Medeiros NI, Oliveira Prado R, Sangenis LH, Chambela MD, Araujo FF, Teixeira-Carvalho A, Damasio MP, Valente VA, Ferreira KS, Sousa GR, Rocha MO, Correa-Oliveira R. 2013. Matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 are differentially expressed in patients with indeterminate and cardiac clinical forms of Chagas disease. Infect. Immun. 81:3600–3608. 10.1128/IAI.00153-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bautista-Lopez NL, Morillo CA, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Quiroz R, Luengas C, Silva SY, Galipeau J, Lalu MM, Schulz R. 2013. Matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 as diagnostic markers in the progression to Chagas cardiomyopathy. Am. Heart J. 165:558–566. 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wan X-X, Gupta S, Zago MP, Davidson MM, Dousset P, Amoroso A, Garg NJ. 2012. Defects of mtDNA replication impaired the mitochondrial biogenesis during Trypanosoma cruzi infection in human cardiomyocytes and chagasic patients: the role of Nrf1/2 and antioxidant response. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 1:e003855. 10.1161/JAHA.112.003855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller MJ, Wrightsman RA, Stryker GA, Manning JE. 1997. Protection of mice against Trypanosoma cruzi by immunization with paraflagellar rod proteins requires T cell, but not B cell, function. J. Immunol. 158:5330–5337 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reed SG. 1988. In vivo administration of recombinant IFN-gamma induces macrophage activation, and prevents acute disease, immune suppression, and death in experimental Trypanosoma cruzi infections. J. Immunol. 140:4342–4347 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zacks MA, Wen JJ, Vyatkina G, Bhatia V, Garg NJ. 2005. An overview of chagasic cardiomyopathy: pathogenic importance of oxidative stress. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 77:695–715. 10.1590/S0001-37652005000400009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holscher C, Mohrs M, Dai WJ, Kohler G, Ryffel B, Schaub GA, Mossmann H, Brombacher F. 2000. Tumor necrosis factor alpha-mediated toxic shock in Trypanosoma cruzi-infected interleukin 10-deficient mice. Infect. Immun. 68:4075–4083. 10.1128/IAI.68.7.4075-4083.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reed SG, Brownell CE, Russo DM, Silva JS, Grabstein KH, Morrissey PJ. 1994. IL-10 mediates susceptibility to Trypanosoma cruzi infection. J. Immunol. 153:3135–3140 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cunha-Neto E, Kalil J. 2001. Heart-infiltrating and peripheral T cells in the pathogenesis of human Chagas' disease cardiomyopathy. Autoimmunity 34:187–192. 10.3109/08916930109007383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cunha-Neto E, Rizzo LV, Albuquerque F, Abel L, Guilherme L, Bocchi E, Bacal F, Carrara D, Ianni B, Mady C, Kalil J. 1998. Cytokine production profile of heart-infiltrating T cells in Chagas' disease cardiomyopathy. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 31:133–137. 10.1590/S0100-879X1998000100018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Higuchi MD, Ries MM, Aiello VD, Benvenuti LA, Gutierrez PS, Bellotti G, Pileggi F. 1997. Association of an increase in CD8+ T cells with the presence of Trypanosoma cruzi antigens in chronic, human, chagasic myocarditis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 56:485–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Higuchi Mde L, Gutierrez PS, Aiello VD, Palomino S, Bocchi E, Kalil J, Bellotti G, Pileggi F. 1993. Immunohistochemical characterization of infiltrating cells in human chronic chagasic myocarditis: comparison with myocardial rejection process. Virchows Arch. A Pathol. Anat. Histopathol. 423:157–160. 10.1007/BF01614765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Souza PE, Rocha MO, Rocha-Vieira E, Menezes CA, Chaves AC, Gollob KJ, Dutra WO. 2004. Monocytes from patients with indeterminate and cardiac forms of Chagas' disease display distinct phenotypic and functional characteristics associated with morbidity. Infect. Immun. 72:5283–5291. 10.1128/IAI.72.9.5283-5291.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Piacenza L, Alvarez MN, Peluffo G, Radi R. 2009. Fighting the oxidative assault: the Trypanosoma cruzi journey to infection. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 12:415–421. 10.1016/j.mib.2009.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gupta S, Wen JJ, Garg NJ. 2009. Oxidative stress in Chagas disease. Interdiscip. Perspect. Infect. Dis. 2009:190354. 10.1155/2009/190354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bianchi ME. 2007. DAMPs, PAMPs and alarmins: all we need to know about danger. J. Leukoc. Biol. 81:1–5. 10.1189/jlb.0306164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Q., Raoof M, Chen Y, Sumi Y, Sursal T, Junger W, Brohi K, Itagaki K, Hauser CJ. 2010. Circulating mitochondrial DAMPs cause inflammatory responses to injury. Nature 464:104–107. 10.1038/nature08780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mills KH. 2011. TLR-dependent T cell activation in autoimmunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 11:807–822. 10.1038/nri3095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thompson MR, Kaminski JJ, Kurt-Jones EA, Fitzgerald KA. 2011. Pattern recognition receptors and the innate immune response to viral infection. Viruses 3:920–940. 10.3390/v3060920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bafica A, Santiago HC, Goldszmid R, Ropert C, Gazzinelli RT, Sher A. 2006. TLR9 and TLR2 signaling together account for MyD88-dependent control of parasitemia in Trypanosoma cruzi infection. J. Immunol. 177:3515–3519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.