Abstract

Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli serotype O157:H7 causes outbreaks of diarrhea, hemorrhagic colitis, and the hemolytic-uremic syndrome. E. coli O157:H7 intimately attaches to epithelial cells, effaces microvilli, and recruits F-actin into pedestals to form attaching and effacing lesions. Lipid rafts serve as signal transduction platforms that mediate microbe-host interactions. The aims of this study were to determine if protein kinase C (PKC) is recruited to lipid rafts in response to E. coli O157:H7 infection and what role it plays in attaching and effacing lesion formation. HEp-2 and intestine 407 tissue culture epithelial cells were challenged with E. coli O157:H7, and cell protein extracts were then separated by buoyant density ultracentrifugation to isolate lipid rafts. Immunoblotting for PKC was performed, and localization in lipid rafts was confirmed with an anti-caveolin-1 antibody. Isoform-specific PKC small interfering RNA (siRNA) was used to determine the role of PKC in E. coli O157:H7-induced attaching and effacing lesions. In contrast to uninfected cells, PKC was recruited to lipid rafts in response to E. coli O157:H7. Metabolically active bacteria and cells with intact lipid rafts were necessary for the recruitment of PKC. PKC recruitment was independent of the intimin gene, type III secretion system, and the production of Shiga toxins. Inhibition studies, using myristoylated PKCζ pseudosubstrate, revealed that atypical PKC isoforms were activated in response to the pathogen. Pretreating cells with isoform-specific PKC siRNA showed that PKCζ plays a role in E. coli O157:H7-induced attaching and effacing lesions. We concluded that lipid rafts mediate atypical PKC signal transduction responses to E. coli O157:H7. These findings contribute further to the understanding of the complex array of microbe-eukaryotic cell interactions that occur in response to infection.

INTRODUCTION

Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) serotype O157:H7 is responsible for outbreaks of diarrhea, hemorrhagic colitis, and hemolytic-uremic syndrome (1). Humans become infected by eating fecally contaminated foodstuffs, through person-to person transmission, or through direct contact with asymptomatically colonized ruminants, particularly cattle (2). Current treatment of EHEC O157:H7 infection remains predominantly supportive in nature (3), since some studies have reported that antibiotics can exacerbate the severity of illness (4). Antibiotics are not efficacious in treating infections because (i) they eliminate competing commensal gut microflora, leading to overgrowth of E. coli O157:H7, (ii) they cause lysis of infecting strains, followed by the release of Shiga toxins, and (iii) induce the expression of phage-harbored Shiga toxin (4). Therefore, alternative therapeutic approaches are required to treat EHEC O157:H7 infections. An improved understanding of the pathobiology of disease could potentially yield novel therapeutic agents that could then be used to interrupt the infectious process.

Enteropathogenic E. coli and enterohemorrhagic E. coli are two closely related noninvasive enteric pathogens that contain the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) pathogenicity island (5). LEE encodes a type III secretion apparatus and effector proteins that cause effacement of brush border microvilli and F-actin cytoskeleton rearrangements. This cytoskeletal rearrangement at the surface of infected host cells just below intimately adherent bacteria results in the formation of adhesion pedestals (6).

EHEC O157:H7 infection is characterized by intimate bacterial attachment to epithelial cells through a variety of adherence factors (7). Bacterial effector proteins encoded on a 35-kb pathogenicity island (LEE) are injected into the cytosol of infected cells through a type III secretion apparatus (8). EspE, also known as translocating intimin receptor (Tir), is one of the effectors that is injected into host cells, where it acts as a receptor for the eaeA gene-encoded bacterial outer membrane protein intimin (9). EspE-intimin interactions give rise to intimate attachment of EHEC O157:H7 to eukaryotic cells, the recruitment of host actin to form dense adhesion pedestals, and the effacement of intestinal brush border microvilli, collectively known as the attaching-effacing lesion (1). One way in which the infectious process can be interrupted is to block the adhesion of enteric pathogens to epithelial cells (10).

Localized translocation of signaling proteins in lipids rafts at the host plasma membrane likely generates localized signal transduction responses (11). Previous studies suggested that the ability of EPEC to raise intracellular calcium levels and generate diacylglycerol (DAG) led to the proposal that EPEC activates calcium-dependent protein kinases, including protein kinase C (PKC), in host epithelia. For instance, SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis bands from EPEC-infected HEp-2 cells resemble those seen in cells exposed to PKC stimulators, such as phorbol esters (12). Whether activation of the secondary messenger PKC is involved in EHEC O157:H7-induced attaching and effacing lesion formation is currently not known, and this forms the basis of the studies described here.

The structure and dynamics of the actin cytoskeleton in cells are regulated by a number of actin-binding proteins, including α-actinin, which is an actin filament-bundling and cross-linking protein that organizes F-actin into three-dimensional structures (13). Activities of actin-binding proteins are controlled through various signaling pathways to ensure proper spatial and temporal regulation of actin dynamics in cells.

Phosphoinositide derivatives are involved in subcellular localization of F-actin. For example, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-biphosphate and phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate are enriched at the plasma membrane, where they control multiple reactions, including organization of the actin cytoskeleton (11). Both phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (14) and PKC family protein kinases have been implicated in regulation of signal transduction that leads to actin reorganization. Therefore, we hypothesized that PKC plays a role in the formation of EHEC O157:H7-induced attaching and effacing lesions.

PKC comprises a family of serine/threonine kinases that are involved in the regulation of diverse cellular responses (15). There are three PKC subfamilies and 12 isoforms currently identified; they are activated through different mechanisms (16). Complementary experimental approaches have been used to investigate the biology of PKC, with both antibodies and inhibitors employed to evaluate the expression and activities of PKC isoforms in epithelial cells responding to external stimuli (17, 18), including intestinal pathogens (19).

Recent studies indicated that the bacterial effector proteins are inserted into cholesterol- and sphingolipid-enriched patches in the eukaryotic cell plasma membrane bilayer; these patches are variously referred to as lipid rafts and detergent-resistant microdomains (20, 21). These islands of a liquid-ordered phase are dispersed focally in the lipid bilayer of the plasma membrane (22, 23). Such cholesterol-enriched microdomains serve as platforms for the recruitment of cell signaling complexes, such as phosphoinositides, into a microenvironment where they are sheltered from nonraft enzymes, which can interfere with signal transduction processes (24). Lipid rafts play an essential role in mediating signal transduction responses in eukaryotic cells (25). The aims of the present study, therefore, were to determine if E. coli O157:H7 affects PKC signaling in host epithelial cells and whether lipid rafts are involved in the signaling responses to this enteric pathogen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissue culture cell lines.

HEp-2 cells (CCL23; American Type Culture Collection [ATCC], Manassas, VA) and intestine 407 (fetal intestinal epithelial cells [ATCC]) were cross-contaminated with HeLa cell-derived genetic material. Epithelial cells were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 in minimal essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% sodium bicarbonate, 1% amphotericin B (Fungizone), and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (all media and supplemental reagents were obtained from Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY).

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli serotype O157:H7, strains CL56, 86-24, CVD451, 85-289, and 85-170 and E. coli strain CL15 (O113:H21) were grown on 5% sheep blood agar (Table 1) (26). Isolated colonies were cultured overnight in Penassay broth at 37°C and then regrown in fresh broth for 3 h at 37°C prior to use. Heat-killed (boiled for 30 min) and formaldehyde-fixed (incubated in 12% formaldehyde for 6 h to 18 h at 4°C) bacteria were used to determine the effects of nonviable bacteria.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and treatments used in the in vitro studies (14)

| E. coli straina | Treatment | Description | Sourceb | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CL56 (EHEC O157:H7) | Boiled | Nonviable with disrupted structure | HC, HUS | |

| Chloramphenicol | Inhibits bacterial protein synthesis | 2, 17 | ||

| Formaldehyde fixed | Kills bacteria, maintains structural integrity | |||

| CL15 (O113:H21) | LEE pathogenicity island absent | HC, HUS | 38 | |

| 86-24 | Wild-type EHEC | HC, HUS | 17 | |

| CVD 451 | Type III secretion-deficient mutant of parental strain 86-24 | Lab strain | 17 | |

| 85-289 | Wild-type EHEC O157:H7 | HC, HUS | 17 | |

| 85-170 | Stx1- and Stx2-negative mutant of parental strain 85-289 | Lab strain | 17 |

The various strains of E. coli and related mutants were grown overnight on sheep blood agar from frozen stocks at 37°C, then grown overnight in Penassay broth, and used to infect model cell lines to delineate microbe-host cell interactions through signaling cross talk (14).

HC, hemorrhagic colitis isolate; HUS, hemolytic uremic syndrome isolate.

Prior to infection of tissue culture cells, bacteria were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in antibiotic-free MEM. For chloramphenicol treatment to arrest bacterial protein synthesis, mid-log-phase bacteria were pelleted and resuspended in chloramphenicol (100 μg/ml) for 6 to 18 h at 4°C (27, 28). Bacteria were added to epithelial cells grown in 10-cm-diameter tissue culture dishes (Starstedt Inc., Montreal, Quebec, Canada) at a multiplicity of infection of approximately 100 bacteria to 1 eukaryotic cell for 1 h at 37°C in antibiotic-free MEM. Uninfected cells were used as a negative control. Cells incubated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; 100 nM), a general activator of protein kinase C (29), were used as a positive control. After 0.5, 1, and 3.5 h of bacterial infection, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.0) to remove nonadherent bacteria and then processed for isolation of detergent-resistant microdomains.

Depletion of cholesterol by use of MβCD.

HEp-2 cells were treated with methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD; 1 to 10 mM; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) to disrupt cholesterol-enriched microdomains by reducing the levels of cholesterol in the plasma membrane (30). Prior to bacterial infection, epithelial cells were incubated with MβCD (10 mM) in antibiotic-free MEM for 1 h at 37°C. The medium was aspirated from cell monolayers, and cells were washed with PBS prior to bacterial infection (31).

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

Eukaryotic cells were seeded onto Lab-Tek four-well chamber slides (Nalge Nunc, Inc., Naperville, IL) and allowed to adhere overnight at 37°C. The tissue culture medium was changed to antibiotic-free medium prior to bacterial infection. Cells were then infected with 109 CFU E. coli in 50 μl at a multiplicity of infection of 100:1 at 37°C in 5% CO2. After 3.5 h of incubation, nonadherent bacteria were removed by washing tissue culture cells three times in PBS (pH 7.4). Cells were then fixed in 100% cold methanol for 10 min at room temperature. Following 3 washes in PBS, fixed cells were incubated with a mouse monoclonal immunoglobulin G anti-α-actinin primary antibody (1:100 dilution; Sigma) for 1 h at 37°C. After washing in PBS, monolayers were incubated with a fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (1:100 dilution; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA) for 1 h and protected from the light. Slides were mounted using SlowFade antifade kits (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and analyzed under alternating phase-contrast and fluorescence microscopy (Leitz Dialux 22; Leica Canada, Inc., Toronto, Ontario, Canada).

Quantification of attaching and effacing lesions was performed by using immunofluorescence microscopy: more than 100 cells in four random fields with at least 25 HEp-2 cells stained for α-actinin were quantified per well. Results are expressed as the average number of α-actinin foci ± the standard error of the mean (SEM) per cell from four separate experiments.

Treatment with pharmacological inhibitors.

Cells were pretreated for 3 h with the general protein kinase C inhibitor bisindolylmaleimide I (10 mM; Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) or Gö6983 (10 or 60 nM; Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) (32). Gö6983 selectively inhibits PKCα, PKCβ, PKCγ, PKCδ, and PKCζ (50% inhibitory concentrations of 7 nM, 7 nM, 6 nM, 10 nM, and 60 nM respectively), while it is inactive against PKCμ. The myristoylated PKCζ pseudosubstrate and PKCα pseudosubstrate (60 μM; Biosource, Camarillo, CA) were used to prevent activation of PKC isoforms (33). Foci of α-actinin formed on cells were quantified as a measure of attaching and effacing lesions (31) that had formed after 3 to 4 h of bacterial challenge. For analysis of PKC in detergent-resistant membranes, epithelial cells were pretreated with the inhibitors and then challenged with bacteria for 1 h at 37°C.

Isolation of detergent-resistant membranes.

Infected epithelial cells were scraped and pelleted in 4 ml of sterile PBS in 15-ml conical tubes. Cells were then lysed with 0.8 ml TN buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10% sucrose, 1% Triton X-100, leupeptin, 2 μg/ml pepstatin A, 10 μg/ml aprotonin, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM Na3VO4) for 30 min on ice, and samples were mixed with 1.7 ml of Optiprep (Axis-Shield PoC AS, Oslo, Norway) and transferred into SW41 centrifuge tubes (catalogue number 344059; Beckman Instruments, Inc., Palo Alto, CA). Optiprep (60%) was diluted with TN buffer to produce 35% and 5% solutions (14), which were then layered on top of samples; the mixtures were then centrifuged at 160,000 × g for 20 h at 4°C. Eight 1.5-ml fractions were then collected from the top to bottom of the gradient generated by ultracentrifugation (34). The low-density, detergent-resistant lipid rafts migrated to the interphase between 5% and 35%, which is represented herein as fraction 3.

Immunoblotting.

Aliquots of each fraction were analyzed for PKC and caveolin-1. Proteins (10 μl of a 1-mg/ml solution) were separated using precast 10% Tris-HCl (Bio-Rad) SDS-PAGE gels with a protein ladder standard (broad-molecular-range ladder; Bio-Rad) at 120 V for 1 to 1.25 h at room temperature. After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Pall Corporation, Pensacola, FL) at 100 V for 1.5 h at 4°C and incubated in Odyssey blocking buffer (Li-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) for 0.5 to 1 h at room temperature. Blocking buffer was then decanted off, and the membrane was probed with anti-caveolin-1 (1:1,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., CA) and primary antibody against PKC (1:1,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) overnight at 4°C on a shaker. After washing the membrane four times (5 min per wash) with PBS plus 0.1% Tween, IRDye 800 goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:20,000; Rockland Immunochemicals, Gilbertsville, PA) was added and incubated for 1 h at room temperature on a shaker. Immunoblots were then washed with PBS plus 0.1% Tween 4 times and with PBS alone once. The membrane was then scanned, and bands were detected by using an Odyssey system (Li-Cor Biosciences) with the 800-nm channel. The integrative intensities of detected bands were obtained by using the software provided with the imaging system (Li-Cor Biosciences).

Transfection.

Small interfering RNAs (siRNA; PKCα siRNA, PKCδ siRNA, and PKCζ siRNA, all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were transfected into HEp-2 cells by using Oligofectamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol (35). Cells were plated into 6-well plates, and when culture confluence reached 50%, siRNA (50 nM) and 10 μl Oligofectamine in 1.5 ml of OPTI-ME was added into each well for 48 h of incubation of cells prior to exposure to EHEC O157:H7. Verification of siRNA knockdown was performed as described previously (36). Western blotting was performed according to a standard protocol (37). Briefly, cells were lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 1% Triton X-100). Proteins were collected (20 μg per well), separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane, and then probed with PKC isoform-specific antibodies (PKC isoform antibody sampler kit; catalog number 9960; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). Band signals were produced by using SuperSignal chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL).

Data analyses.

The results are reported as means ± SEM. To test for significance of the differences between two groups, a two-tailed Student's t test was employed, with a P value of <0.05 considered statistically significant. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for data derived from more than two experimental groups (38).

RESULTS

PKC is recruited to lipid rafts in response to EHEC O157:H7.

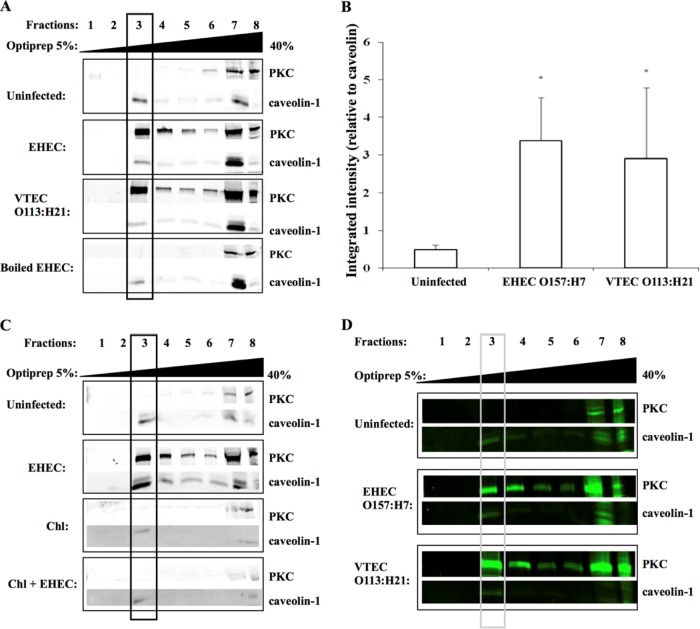

Following E. coli O157:H7 challenge of HEp-2 cells, PKC was present in the sucrose fraction that contained caveolin-1 (Fig. 1A and B), which was used as a marker protein for enrichment of lipid rafts (14). PKC translocation to detergent-resistant membranes was not observed when tissue culture cells were infected with heat-killed bacteria, demonstrating that activation and recruitment of PKC to lipid rafts was triggered by exposure of epithelial cells to live microorganisms. Chloramphenicol-treated bacteria also did not induce the movement of PKC to lipid rafts (Fig. 1C), suggesting that signaling was induced by newly synthesized bacterial proteins. Translocation of PKC to detergent-resistant membranes was also observed when intestine 407 cells were challenged with EHEC O157:H7 (Fig. 1D).

FIG 1.

PKC translocation to lipid rafts following EHEC O157:H7 challenge. (A) Immunoblots of protein kinase C from ultracentrifugation fractions prepared from HEp-2 epithelial cell extracts. The presence of PKC in caveolin-1-enriched fractions indicates recruitment to lipid rafts in response to bacterial challenge. (B) Integrated intensity of PKC expression over caveolin-1 expression in fraction 3 of EHEC-infected and uninfected cells. Data are from four independent experiments. *, P < 0.05. (C) PKC was not recruited to lipid rafts in HEp-2 cells challenged with chloramphenicol-treated EHEC O157:H7, indicating that metabolically active bacteria are required for host signaling. (D) Translocation of PKC to lipid rafts in response to EHEC challenge also occurred in intestine 407 epithelial cells. MOI, 100:1. Rabbit anti-PKC and rabbit anti-caveolin-1 primary antibodies (1:1,000) and IRDye 800 goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:20,000) were used.

PKC recruitment to lipid rafts is independent of known EHEC virulence factors.

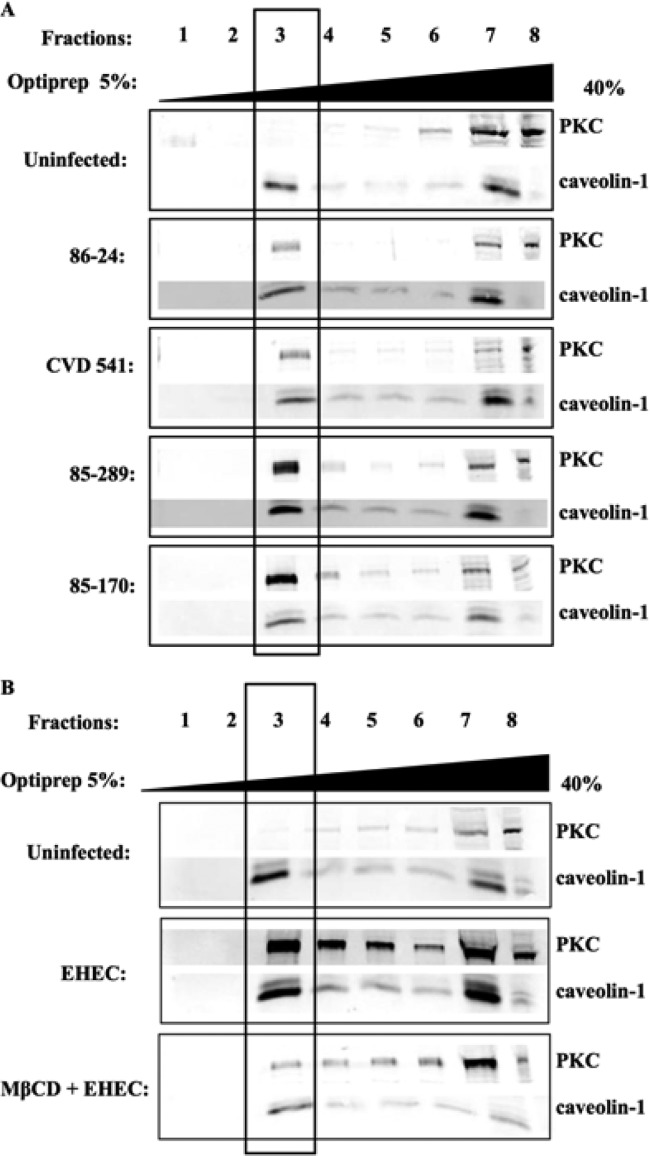

As shown in Fig. 2A, an increase in PKC in caveolin-enriched fractions was observed in response to infection with E. coli strain CL15 (serotype O113:H21), suggesting that PKC recruitment is independent of the attaching and effacing (eaeA) intimin gene also found in EHEC, because this Shiga toxin-producing E. coli isolate is eaeA negative and does not cause attaching and effacing lesions (39). HEp-2 cells challenged with EHEC strain CVD451, a type III secretion-deficient mutant (27), and the parental strain (86-24) also demonstrated PKC recruitment to caveolin-1-enriched fractions of the sucrose gradients. Similarly, exposure of epithelial cells to E. coli 85-170, a Stx1- and Stx2-negative strain (27), and Stx-expressing strain 85-289 also resulted in PKC movement to the caveolin-1-enriched fraction of a sucrose gradient (Fig. 2A). Taken together, these findings suggest that PKC activation and movement to detergent-resistant membranes in response to EHEC O157:H7 challenge is independent of both the LEE-encoded type III secretion system and the production of Shiga toxins.

FIG 2.

Recruitment of PKC to cholesterol-enriched microdomains is independent of the type III secretion system and the production of Shiga toxins 1 and 2, but dependent on intact lipid rafts. (A) The presence of PKC in caveolin-1-enriched lipid rafts was observed following challenge of HEp-2 cells with either a type III secretion mutant (CVD 451) and its parental strain, 86-24, or a Shiga toxin-negative mutant (85-170) and its Shiga toxin-positive parental strain, 85-289. These findings indicated that EHEC O157:H7-induced recruitment of host signaling proteins is independent of the EHEC type III secretion system and the production of Shiga toxins. (B) MβCD disruption of lipid rafts resulted in a decrease in PKC, which corresponded with a decrease in caveolin in fraction 3. These findings suggest that PKC is associated with lipid rafts. MOI, 100:1. Rabbit anti-PKC and rabbit anti-caveolin-1 primary antibody (1:1,000) and IRDye 800 goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:20,000) were used.

MβCD treatment reduces PKC recruitment to lipid rafts in response to EHEC O157:H7.

Cells were pretreated with methyl-β-cyclodextrin (10 mM) to deplete cholesterol from the plasma membrane and thereby disrupt the formation of lipid rafts (31). As shown in Fig. 2B, the depletion of cholesterol reduced the total amount of caveolin-1 and PKC in fraction 3. The amount of PKC normalized against the caveolin-1 expression level indicated that MβCD caused a reduction in PKC recruitment to lipid rafts when challenged with EHEC O157:H7. These findings indicated that intact lipid rafts play a role in PKC signal transduction responses in epithelial cells challenged with E. coli O157:H7.

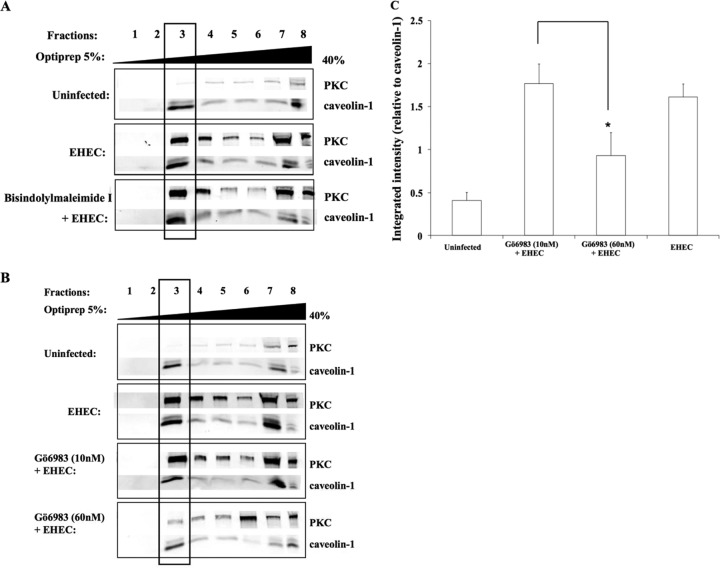

Recruitment of PKC to lipid rafts and EHEC O157:H7-induced attaching and effacing lesions are blocked by specific PKC isoform inhibitors.

Pretreatment of epithelial cells with the pan-PKC inhibitor bisindolylmaleimide I (10 mM) for 3 h prior to EHEC O157:H7 challenge did not result in a reduction in the amount of PKC present in lipid rafts (Fig. 3A). Cells pretreated with a low dose of the PKC inhibitor Gö6983 (10 nM) also did not show reduced translocation of PKC to lipid rafts in response to EHEC O157:H7 (Fig. 3B). By contrast, epithelial cells pretreated with a higher dose of the PKC inhibitor Gö6983 (60 nM) showed a reduction in PKC levels present in caveolin-enriched membrane fractions (Fig. 3C), suggesting that an atypical PKC isoform is involved in PKC activation and subsequent recruitment of other isoforms to lipid rafts in response to challenge with EHEC O157:H7 (40).

FIG 3.

EHEC O157:H7 induces recruitment of atypical PKC isoforms to lipid rafts. (A) HEp-2 cells pretreated with bisindolylmaleimide I did not block the recruitment of PKC to lipid rafts in response to EHEC O157:H7 infection, indicating that the classical isoform of PKC is not involved in the infection process. MOI, 100:1. Rabbit anti-PKC and rabbit anti-caveolin-1 primary antibody (1:1,000) and IRDye 800 goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:20,000) were used. (B) PKC recruitment to rafts in EHEC O157:H7-challenged epithelial cells treated with the PKC inhibitor Gö6983 at 10 nM suggested that neither the classical nor the novel isoforms of PKC are recruited to lipid rafts. By contrast, inhibition by a higher concentration (60 nM) of the inhibitor indicated that atypical PKC isoforms are likely to be involved. (C) Densitometry quantification of PKC recruited to lipid rafts in response to EHEC O157:H7 challenge following exposure to various concentrations of Gö6983. Data are from three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05. MOI, 100:1.

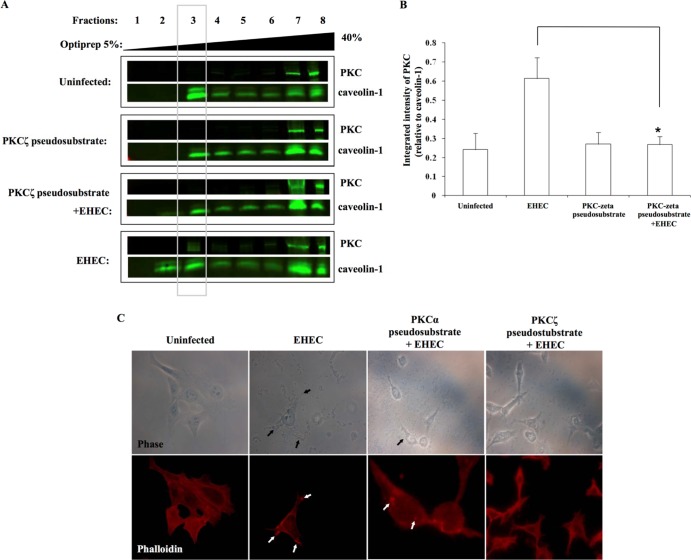

Myristoylated PKCζ pseudosubstrate-pretreated epithelial cells demonstrated a decrease in the amount of PKC contained in caveolin-1-enriched sucrose gradient fractions following EHEC O157:H7 challenge of the epithelial cells in tissue culture (Fig. 4A and B). Additional evidence that the PKCζ isoform is involved in EHEC O157:H7-induced rearrangement of the cytoskeleton was provided by our finding that attaching and effacing lesions were reduced in infected epithelial cells that had been pretreated with a PKCζ pseudosubstrate (Fig. 4C). By contrast, a PKCα pseudosubstrate did not prevent induction of attaching and effacing lesions in epithelial cells exposed to EHEC O157:H7.

FIG 4.

Atypical isoforms of PKC are present in lipid rafts following EHEC O157:H7 challenge of epithelial cells. (A) Immunoblots of cell fractions following exposure of HEp-2 epithelial cells to a PKCζ inhibitor (60 μM) decreased PKC in caveolin-1-enriched sucrose gradient fraction number 3 in response to EHEC O157:H7. (B) Densitometry quantification demonstrated a significant reduction in the amount of PKCζ in lipid raft-containing fraction 3 in HEp-2 cells exposed to the PKCζ pseudosubstrate prior to EHEC O157:H7 challenge (MOI, 100:1; 1 h). Data are from four independent experiments. *, P < 0.05. (C) EHEC O157:H7 challenge of HEp-2 epithelial cells pretreated with a PKCα pseudosubstrate (60 μM) induced attaching and effacing lesions. By contrast, cells pretreated with the PKC-ζ pseudosubstrate (60 μM) showed a reduction in the number of attaching and effacing lesions formed in response to EHEC O157:H7.

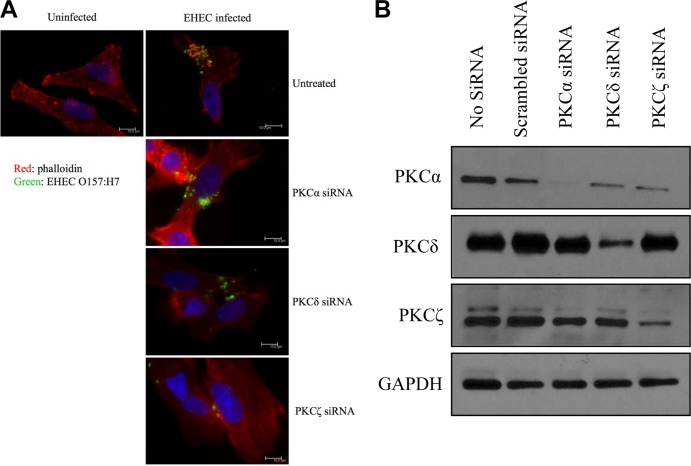

PKC siRNA inhibits EHEC O157:H7-induced attaching and effacing lesions.

Pretreatment of cells with either PKCα or PKCδ siRNA did not inhibit EHEC-induced formation of attaching and effacing lesions (Fig. 5A). However, epithelial cells pretreated with PKCζ siRNA no longer demonstrated attaching and effacing lesions (Fig. 5A), indicating that it is the PKCζ isoform that is involved in EHEC-induced rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton. Western blot analysis demonstrated that siRNA knockdown was efficient in reducing the expression of PKCα, PKCδ, and PKCζ (Fig. 5B).

FIG 5.

PKCζ mediates EHEC O157:H7-induced attaching and effacing lesion formation. (A) Fluorescent-labeled phalloidin staining of F-actin in HEp-2 epithelial cells showed the presence of attaching and effacing lesions following EHEC O157:H7 challenge of cells in the absence of siRNA or in the presence of both PKCα siRNA and PKCδ siRNA. By contrast, cells pretreated with PKCζ siRNA and then incubated with EHEC O157:H7 no longer demonstrated attaching and effacing lesions subjacent to adherent bacteria (green). (B) Western blot analysis demonstrated that siRNA knockdown reduced the expression of PKCα, PKCδ, and PKCζ.

DISCUSSION

This study provides novel findings indicating, for the first time, that EHEC O157:H7 activates the ζ isoform of the secondary messenger PKC through plasma membrane lipid rafts to induce attaching and effacing lesions. PKC activation is not the result of preformed bacterial surface structures, because recruitment to caveolin-1-enriched fractions was observed only when epithelial cells were challenged with live microorganisms actively undergoing protein synthesis. It is known that EHEC O157:H7 is capable of disrupting intestinal barrier function and causes gut inflammation by manipulating key signal transduction cascades in host cells (41).

Previous studies have shown that the presence of cholesterol-enriched plasma membrane lipid rafts are required for attaching and effacing lesions induced by EHEC O157:H7 (20, 31). When lipid rafts were disrupted with the cholesterol-sequestering reagent methyl-β-cyclodextrin, EHEC challenge no longer induced the translocation of PKC to the caveolin-1-enriched membrane fraction. This finding provided evidence that EHEC O157:H7 induces rearrangements in the host cytoskeleton, and the formation of adhesion pedestals occurs via signal transduction events in functionally intact lipid rafts.

Epithelial cells challenged with chloramphenicol-treated bacteria, used to block prokaryotic protein synthesis (28), did not result in the presence of PKC in the caveolin-1-enriched membrane fractions. This finding indicates that newly synthesized bacterial proteins trigger the recruitment of PKC to lipid rafts in the host cell plasma membrane. Identification of the precise bacterial factor(s) that mediates this event is the subject of ongoing research in our laboratory.

Although production of Shiga toxins has been reported to promote bacterial colonization of the human intestine (42), EHEC O157:H7-derived Shiga toxins do not play a role in recruiting PKC to lipid rafts (43). PKC translocation to the membrane or binding to DAG induces PKC activation (44). However, PKC activation and its destined membrane site is determined by the PKC isoforms and the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway. Various PKCs have also been suggested to self-regulate the translocation of their isoforms to the cell membrane (36).

The possibility of the involvement of an atypical PKC isoform, instead of classical PKC, in the EHEC O157:H7 infectious process was suggested when pretreatment of cells with the classical PKC inhibitor bisindolylmaleimide I (40) did not block translocation of PKC to lipid rafts. Cells pretreated with the lower concentration of a concentration-dependent PKC inhibitor (Gö6983) confirmed this result. Furthermore, a higher concentration of the Gö6983 inhibitor significantly reduced levels of PKC in caveolin-1-enriched fractions following EHEC O157:H7 challenge; these findings also suggest that bacterial challenge activates an atypical isoform of PKC (45). The effects of the pharmacological inhibitors were complemented and confirmed when we used a highly specific myristolated PKCζ pseudosubstrate. In this study, EHEC-induced translocation of PKC required the activation of PKCζ.

Atypical isoforms of PKC, including PKCζ, are key regulators of critical intracellular signal transduction pathways induced by extracellular stimuli (46), including colonic epithelial cell proliferation (47), regulation of the integrity of intercellular tight junctions (48), and the activation of host immune responses to bacterial infection (49). PKC has the ability to induce translocation of other signaling proteins to lipid rafts in response to microbial pathogens (50). This complex signaling mechanism leads to the regulation of actin-regulating proteins, including Arp2/3, N-WASP, Nck, and α-actinin. Future research will characterize how PKC interacts with these actin-regulating molecules in EHEC-O157-challenged epithelium.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by an operating grant from the Canadian Institute for Health Research (CIHR MOP-89894). G.S.-T. was the recipient of a CIHR Graduate Scholarship Award and research training funding support provided by the SickKids Foundation. P.M.S. is the recipient of a Canada Research Chair in Gastrointestinal Disease.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 3 February 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Kaper JB, Nataro JP, Mobley HL. 2004. Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:123–140. 10.1038/nrmicro818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barlow RS, Mellor GE. 2010. Prevalence of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli serotypes in Australian beef cattle. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 7:1239–1245. 10.1089/fpd.2010.0574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tarr PI, Gordon CA, Chandler WL. 2005. Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli and haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Lancet 365:1073–1086. 10.016/S0140-6736(05)71144-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panos GZ, Betsi GI, Falagas ME. 2006. Systematic review: are antibiotics detrimental or beneficial for the treatment of patients with Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection? Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 24:731–742. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03036.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jandu N, Shen S, Wickham ME, Prajapati R, Finlay BB, Karmali MA, Sherman PM. 2007. Multiple seropathotypes of verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli (VTEC) disrupt interferon-gamma-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription (Stat)-1. Microb. Pathog. 42:62–71 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2006.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hazen TH, Sahl JW, Fraser CM, Donnenberg MS, Scheutz F, Rasko DA. 2013. Refining the pathovar paradigm via phylogenomics of the attaching and effacing Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110:12810–12815. 10.1073/pnas.1306836110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gyles CL. 2007. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli: an overview. J. Anim. Sci. 85:E45–E62. 10.2527/jas.2006/508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Welinder-Olsson C, Kaijser B. 2005. Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC). Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 37:405–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campellone KG, Robbins D, Leong JM. 2004. EspFU is a translocated EHEC effector that interacts with Tir and N-WASP and promotes Nck-independent actin assembly. Dev. Cell 7:217–228. 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collado MC, Meriluoto J, Salminen S. 2007. Role of commercial probiotic strains against human pathogen adhesion to intestinal mucus. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 45:454–460. 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2007.02212.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saarikangas J, Zhao H, Lappalainen P. 2010. Regulation of the actin cytoskeleton-plasma membrane interplay by phosphoinositides. Physiol. Rev. 90:259–289. 10.1152/physrev.00036.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baldwin TJ, Brooks SF, Knutton S, Manjarrez Hernandez HA, Aitken A, Williams PH. 1990. Protein phosphorylation by protein kinase C in HEp-2 cells infected with enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 58:761–765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goosney DL, de Grado M, Finlay BB. 1999. Putting E. coli on a pedestal: a unique system to study signal transduction and the actin cytoskeleton. Trends Cell Biol. 9:11–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen-Tu G, Schauer DB, Jones NL, Sherman PM. 2010. Detergent-resistant microdomains mediate activation of host cell signaling in response to attaching-effacing bacteria. Lab. Invest. 90:266–281. 10.1038/labinvest.2009.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dempsey EC, Newton AC, Mochly-Rosen D, Fields AP, Reyland ME, Insel PA, Messing RO. 2000. Protein kinase C isozymes and the regulation of diverse cell responses. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 279:L429–L438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steinberg SF. 2004. Distinctive activation mechanisms and functions for protein kinase Cδ. Biochem. J. 384:449–459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Disatnik MH, Buraggi G, Mochly-Rosen D. 1994. Localization of protein kinase C isozymes in cardiac myocytes. Exp. Cell Res. 210:287–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mochly-Rosen D, Henrich CJ, Cheever L, Khaner H, Simpson PC. 1990. A protein kinase C isozyme is translocated to cytoskeletal elements on activation. Cell Regul. 1:693–706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sokolova O, Vieth M, Naumann M. 2013. Protein kinase C isozymes regulate matrix metalloproteinase-1 expression and cell invasion in Helicobacter pylori infection. Gut 62:358–367. 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allen-Vercoe E, Waddell B, Livingstone S, Deans J, DeVinney R. 2006. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli Tir translocation and pedestal formation requires membrane cholesterol in the absence of bundle-forming pili. Cell. Microbiol. 8:613–624. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00654.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zobiack N, Rescher U, Laarmann S, Michgehl S, Schmidt MA, Gerke V. 2002. Cell-surface attachment of pedestal-forming enteropathogenic E. coli induces a clustering of raft components and a recruitment of annexin 2. J. Cell Sci. 115:91–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Goot FG, Harder T. 2001. Raft membrane domains: from a liquid-ordered membrane phase to a site of pathogen attack. Semin. Immunol. 13:89–97 http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/smim.2000.0300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zaas DW, Duncan M, Rae Wright J, Abraham SN. 2005. The role of lipid rafts in the pathogenesis of bacterial infections. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1746:305–313 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vieira FS, Corra G, Einicker Lamas M, Coutinho Silva R. 2010. Host cell lipid rafts: a safe door for microorganisms? Biol. Cell 102:391–407. 10.1042/BC20090138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manes S, Ana Lacalle R, Gomez-Mouton C, Martinez AC. 2003. From rafts to crafts: membrane asymmetry in moving cells. Trends Immunol. 24:320–326. 10.1016/S1471-4906(03)00137-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ismaili A, Philpott DJ, Dytoc MT, Sherman PM. 1995. Signal transduction responses following adhesion of verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 63:3316–3326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ceponis PJ, McKay DM, Ching JC, Pereira P, Sherman PM. 2003. Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 disrupts Stat1-mediated gamma interferon signal transduction in epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 71:1396–1404. 10.1128/IAI.71.3.1396-1404.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jandu N, Ceponis PJ, Kato S, Riff JD, McKay DM, Sherman PM. 2006. Conditioned medium from enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli-infected T84 cells inhibits signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 activation by gamma interferon. Infect. Immun. 74:1809–1818. 10.1128/IAI.74.3.1809-1818.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grigat J, Soruri A, Forssmann U, Riggert J, Zwirner J. 2007. Chemoattraction of macrophages, T lymphocytes, and mast cells is evolutionarily conserved within the human alpha-defensin family. J. Immunol. 179:3958–3965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kilsdonk EP, Yancey PG, Stoudt GW, Bangerter FW, Johnson WJ, Phillips MC, Rothblat GH. 1995. Cellular cholesterol efflux mediated by cyclodextrins. J. Biol. Chem. 270:17250–17256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riff JD, Callahan JW, Sherman PM. 2005. Cholesterol-enriched membrane microdomains are required for inducing host cell cytoskeleton rearrangements in response to attaching-effacing Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 73:7113–7125. 10.1128/IAI.73.11.7113-7125.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sakwe AM, Rask L, Gylfe E. 2005. Protein kinase C modulates agonist-sensitive release of Ca2+ from internal stores in HEK293 cells overexpressing the calcium sensing receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 280:4436–4441. 10.1074/jbc.M411686200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xin M, Gao F, May WS, Flagg T, Deng X. 2007. Protein kinase Cζ abrogates the proapoptotic function of Bax through phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 282:21268–21277. 10.1074/jbc.M701613200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Macdonald JL, Pike LJ. 2005. A simplified method for the preparation of detergent-free lipid rafts. J. Lipid Res. 46:1061–1067. 10.1194/jlr.D400041-JLR200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lodyga M, De Falco V, Bai X, Kapus A, Melillo R, Santoro M, Liu M. 2009. XB130, a tissue-specific adaptor protein that couples the RET/PTC oncogenic kinase to PI 3-kinase pathway. Oncogene 28:937–949. 10.1038/onc.2008.447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiao H, Bai X-H, Kapus A, Lu W-Y, Mak AS, Liu M. 2010. The protein kinase C cascade regulates recruitment of matrix metalloprotease 9 to podosomes and its release and activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30:5545–5561. 10.1128/MCB.00382-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim H, Zamel R, Bai XH, Liu M. 2013. PKC activation induces inflammatory response and cell death in human bronchial epithelial cells. PLoS One 8(5):e64182. 10.1371/journal.pone.0064182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bewick V, Cheek L, Ball J. 2004. Statistics review 9: one-way analysis of variance. Crit. Care 8:130–136. 10.1186/cc2836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shen S, Mascarenhas M, Rahn K, Kaper JB, Karmali MA. 2004. Evidence for a hybrid genomic island in verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli CL3 (serotype O113:H21) containing segments of EDL933 (serotype O157:H7) O islands 122 and 48. Infect. Immun. 72:1496–1503. 10.1128/IAI.72.3.1496-1503.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cuschieri J, Umanskiy K, Solomkin J. 2004. PKC-zeta is essential for endotoxin-induced macrophage activation. J. Surg. Res. 121:76–83. 10.1016/j.jss.2004.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guttman JA, Li Y, Wickham ME, Deng W, Vogl AW, Finlay BB. 2006. Attaching and effacing pathogen-induced tight junction disruption in vivo. Cell. Microbiol. 8:634–645. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00656.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robinson CM, Sinclair JF, Smith MJ, O'Brien AD. 2006. Shiga toxin of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli type O157:H7 promotes intestinal colonization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:9667–9672. 10.1073/pnas.0602359103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Proulx F, Seidman EG, Karpman D. 2001. Pathogenesis of Shiga toxin-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatr. Res. 50:163–171. 10.1203/00006450-200108000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Urtreger AJ, Kazanietz MG, Bal de Kier Joffe ED. 2012. Contribution of individual PKC isoforms to breast cancer progression. IUBMB Life 64:18–26. 10.1002/iub.574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang P, Chan J, Dragoi A-M, Gong X, Ivanov S, Li Z-W, Chuang T, Tuthill C, Wan Y, Karin M. 2005. Activation of IKK by thymosin alpha-1 requires the TRAF6 signalling pathway. EMBO Rep. 6:531–537. 10.1038/sj.embor.7400433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hirai T, Chida K. 2003. Protein kinase Cζ (PKCζ): activation mechanisms and cellular functions. J. Biochem. 133:1–7. 10.1093/jb/mvg017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Umar S, Sellin JH, Morris AP. 2000. Increased nuclear translocation of catalytically active PKC-zeta during mouse colonocyte hyperproliferation. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 279:G223–G237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tomson FL, Koutsouris A, Viswanathan VK, Turner JR, Savkovic SD, Hecht G. 2004. Differing roles of protein kinase C-zeta in disruption of tight junction barrier by enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Gastroenterology 127:859–869. 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Savkovic SD, Koutsouris A, Hecht G. 2003. PKC zeta participates in activation of inflammatory response induced by enteropathogenic E. coli. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 285:C512–C521. 10.1152/ajpcell.00444.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bauer B, Jenny M, Fresser F, Uberall F, Baier G. 2003. AKT1/PKBα is recruited to lipid rafts and activated downstream of PKC isotypes in CD3-induced T cell signaling. FEBS Lett. 541:155–162 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00287-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]