Abstract

Burkholderia pseudomallei is a Gram-negative rod and the causative agent of melioidosis, an emerging infectious disease of tropical and subtropical areas worldwide. B. pseudomallei harbors a remarkable number of virulence factors, including six type VI secretion systems (T6SS). Using our previously described plaque assay screening system, we identified a B. pseudomallei transposon mutant defective in the BPSS1504 gene that showed reduced plaque formation. The BPSS1504 locus is encoded within T6SS cluster 1 (T6SS1), which is known to be involved in the pathogenesis of B. pseudomallei in mammalian hosts. For further analysis, a B. pseudomallei BPSS1504 deletion (BpΔBPSS1504) mutant and complemented mutant strain were constructed. B. pseudomallei lacking the BPSS1504 gene was highly attenuated in BALB/c mice, whereas the in vivo virulence of the complemented mutant strain was fully restored to the wild-type level. The BpΔBPSS1504 mutant showed impaired intracellular replication and formation of multinucleated giant cells in macrophages compared with wild-type bacteria, whereas the induction of actin tail formation within host cells was not affected. These observations resembled the phenotype of a mutant lacking hcp1, which is an integral component of the T6SS1 apparatus and is associated with full functionality of the T6SS1. Transcriptional expression of the T6SS components vgrG, tssA, and hcp1, as well as the T6SS regulators virAG, bprC, and bsaN, was not dependent on BPSS1504 expression. However, secretion of Hcp1 was not detectable in the absence of BPSS1504. Thus, BPSS1504 seems to serve as a T6SS component that affects Hcp1 secretion and is therefore involved in the integrity of the T6SS1 apparatus.

INTRODUCTION

Burkholderia pseudomallei is a Gram-negative soil saprophyte that is distributed in tropical and subtropical areas around the world. The bacterium causes melioidosis, an often fatal infectious disease that affects human and a wide range of animals. Frequent infection routes are inoculation via abrasions and minor cuts by contaminated soil or water, as well as inhalation of aerosols (1, 2). Typical clinical manifestations include pneumonia and sepsis, with high mortality rates even after appropriate antibiotic treatment (1, 3). Various underlying diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure, and chronic lung diseases, are proven risk factors for the acquisition of clinically manifest melioidosis (1).

As a facultative intracellular pathogen, B. pseudomallei is able to invade host cells, escape from the endolysosome, survive within the cytosol, and to spread directly from cell to cell (4–6). Numerous virulence factors are known to contribute to this intracellular lifestyle, which is crucial for full virulence of the pathogen (7–9). B. pseudomallei harbors a remarkable number of various secretion systems, including three type III and six type VI secretion systems (T3SS and T6SS, respectively) (6, 10–12). T6SS are widely distributed among Gram-negative bacteria and are considered to inject effector proteins into eukaryotic or bacterial cells (13–17). The hemolysin-coregulated protein (Hcp) and valine-glycine repeat protein G (VgrG) are hallmarks of all T6SS and secreted components of the T6SS apparatus itself (10, 18). The secretion of Hcp is considered to be a reliable indicator for a functional T6SS (18). A recent study analyzed the relevance of each single Hcp that is present in the various T6SS clusters of B. pseudomallei for virulence (10). The authors found that only deletion of Hcp from cluster 1 (Hcp1) led to a strong attenuation of B. pseudomallei, suggesting a prominent role of the T6SS cluster 1 (T6SS1; BPSS1496 to BPSS1511) for the virulence in mammalian hosts.

At present, there is vivid activity in unraveling the quite complex regulatory cascades of T6SS gene expression and the remarkable cross talk between T3SS and T6SS proteins in B. pseudomallei BprC, encoded within cluster 3 of the T3SS in B. pseudomallei, was found to regulate T6SS1 gene expression (19, 20), and the T3SS regulator BsaN was shown to be involved in the transcriptional activation of the T6SS1 regulator virA-virG (virAG) (20). VirAG represents a two-component sensor-regulator system that is encoded within the T6SS1 cluster, upregulating other T6SS1 genes, such as hcp1, after internalization of bacteria in host cells (19, 21). It was also demonstrated previously that iron and zinc could negatively regulate T6SS1 gene expression (21).

In the present report, we identified the BPSS1504 gene, located within the T6SS1 cluster of B. pseudomallei, to be a critical component for the pathogenicity of this versatile pathogen. An experimental murine model of melioidosis was used to demonstrate the remarkable contribution of BPSS1504 to in vivo virulence. We also examined the role of BPSS1504 for intracellular survival and induction of multinucleated giant cell (MNGC) and actin tail formation in mammalian cells. Using quantitative real-time PCR, we investigated the influence of BPSS1504 on the expression of other T6SS1-associated components and regulators. Finally, we examined the influence of BPSS1504 on Hcp1 secretion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. B. pseudomallei and Escherichia coli strains were grown on LB agar or in LB broth at 37°C. If not stated otherwise, antibiotics were added at the following concentrations: 50 μg/ml ampicillin (Ap), 37.5 μg/ml kanamycin (Km), 3,000 μg/ml zeocin, and 25 μg/ml polymyxin B. Kmr gene-containing plasmids used for conjugation of B. pseudomallei strain E8 were selected with 1,000 μg/ml Km. All experiments with B. pseudomallei were carried out in biosafety level 3 (BSL3) laboratories.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids and bacterial strains used in this study

| Plasmid or strain | Relevant characteristic(s)a | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR2.1-TOPO | TA cloning vector; Kmr Apr | Invitrogen |

| pCR2.1-TOPO-ΔBPSS1504 | pCR2.1-TOPO cloning vector containing 647-bp fragment upstream and 827-bp fragment downstream of BPSS1504 ORF; Kmr Apr | This study |

| pCR2.1-TOPO-Δhcp1 | pCR2.1-TOPO cloning vector containing 793-bp fragment upstream and 550-bp fragment downstream of BPSS1498 (hcp1) ORF; Kmr Apr | This study |

| pEX-Km5 | Kmr; gusA reporter gene; B. pseudomallei optimized sacB gene | 22 |

| pEX-KM5-ΔBPSS1504 | pEX-Km5 containing 647-bp fragment upstream and 827-bp fragment downstream of ORF BPSS1504 | This study |

| pEX-KM5-Δhcp1 | pEX-Km5 containing 792-bp fragment upstream and 550-bp fragment downstream of ORF BPSS1498 (hcp1) | This study |

| pUC18TminiTn7-Zeo-loxP | Apr Zeor; mobilizable mini-Tn7 base vector with loxP-PEM7-ble-loxP fragment | 24 |

| pUC18TminiTn7-Zeo-BPSS1504 | pUC18TminiTn7-Zeo-loxP containing BPSS1504 ORF | This study |

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| SM10(pOT182) | Mobilizing strain for transfer of Tn5-OT182 into B. pseudomallei; Kmr Cmr Gmr Tcr Apr | 43 |

| RHO3 | SM10(λpir)Δasd::FRTΔaphA::FRT Kms; DAP auxotroph | 22 |

| DH5α | Cloning host | Invitrogen |

| DH5α(pTNS3) | Helper strain for conjugal transfer; Apr | 24 |

| HB101(pRK2013) | Helper strain for conjugal transfer | 41 |

| B. pseudomallei | ||

| E8 | Wild-type strain (soil isolate) | 42 |

| BpTn5::BPSS1504 complemented mutant | E8 derivate, BPSS1504 ORF disrupted by Tn5-OT182; Tcr | This study |

| BpΔBPSS1504 mutant | E8 derivate, BPSS1504 ORF deleted | This study |

| BpΔBPSS1504::BPSS1504 complemented mutant | ΔBPSS1504 mutant with chromosomal miniTn7-Zeo-BPSS1504 | This study |

| BpΔBPSS1539 (BpΔbsaU) | E8 derivate, BPSS1539 (bsaU) ORF deleted | 44 |

| BpΔhcp1 | E8 derivate, hcp1 ORF deleted | This study |

Abbreviations: DAP, 2,6-diaminopimelic acid; Apr, ampicillin resistant; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistant; Gmr, gentamycin resistant; Kmr, kanamycin resistant; Tcr, tetracycline resistant; Zeor, zeocin resistant.

Transposon mutagenesis.

B. pseudomallei strain E8 was mutagenized with Tn5-OT182 and examined for mutants exhibiting defects in plaque formation in a plaque assay screen using Ptk2 cells as previously described (7). In one of the mutants that exhibited reduced plaque formation compared to the wild-type (WT) strain, the transposon insertion site was identified as described previously (7) and found to be inserted behind base 2413 of the BPSS1504 locus.

Targeted mutagenesis.

To construct markerless deletion B. pseudomallei mutants, the sacB-based vector pEX-Km5 was used as previously described (22). The bsaU mutant was constructed as previously described (44). Up- and downstream PCR products of the BPSS1504 and hcp1 (BPSS1498) loci were fused together by overlap extension PCR and cloned into pEX-Km5, resulting in the plasmids pEX-KM5-ΔBPSS1504 and pEX-Km5-Δhcp1, respectively. The pEX-KM5 plasmids were introduced into E. coli RHO3 by heat shock transformation and selected on LB plates containing 37.5 μg/ml Km and 400 μg/ml 2,6-diaminopimelic acid (DAP). Grown colonies were incubated overnight in LB broth containing 300 μg/ml DAP and 37.5 μg/ml Km in a rotating incubator. For conjugation, 100 μl of B. pseudomallei E8 overnight culture was mixed with 200 to 1,200 μl of pEX-KM5-ΔBPSS1504 or pEX-Km5-Δhcp1 containing E. coli RHO3 overnight culture, and LB broth was added to a final volume of 1.5 ml. Bacterial suspensions were centrifuged for 1 min at 6,000 × g, and cell pellets were washed with 1 ml of 10 mM MgSO4. Bacteria were resuspended in 30 μl of 10 mM MgSO4, delivered onto cellulose-acetate membrane filters (diameter, 13 mm; pore size, 0.45 μm; Satorius-Stedim) on prewarmed LB agar plates containing 400 μg/ml DAP, and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. Membrane filters were transferred in 1.5-ml tubes with 1 ml LB broth and centrifuged for 30 to 60 s at 5,000 × g. Bacterial pellets were resuspended in 400 μl LB broth, plated onto LB agar plates containing 1,000 μg/ml Km, and incubated for 48 h at 37°C. Growing colonies were subcultivated on LB agar plates containing 1,000 μg/ml Km and 50 μg/ml 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-glucuronic acid (X-Gluc). Blue colonies that were verified by PCR to hold the pEX-KM5 constructs were transferred into YT broth (10 g/liter yeast extract, 10 g/liter tryptone) (AppliChem) for 4 h in a rotating incubator at 37°C and 140 rpm, subsequently plated onto YT agar plates containing 15% sucrose, and incubated at 37°C for 48 h. Growing colonies were tested by PCR for mutated genes.

Complementation.

To complement the B. pseudomallei BPSS1504 deletion (BpΔBPSS1504) mutant, we used the mini-Tn7 system as recently described (23). The forward primer BPSS1504for-HindIII and reverse primer BPSS1504rev-KpnI (Table 2) were used to amplify the open reading frame (ORF) BPSS1504 of B. pseudomallei E8 by using genomic DNA as the template. Following digestion, this fragment was cloned into the pUC18T mini-Tn7T-Zeo vector (24), transformed into E. coli DH5α, and delivered into the BpΔBPSS1504 mutant by four-parent mating using the donor strain E. coli DH5α(pUC18T mini-Tn7T-Zeo-BPSS1504) and two E. coli helper strains [E. coli HB101(pRK2013) and E. coli DH5α (pTNS3)] as recently described (23, 24). Selection was performed on 4% glycerol-containing LB agar plates with zeocin and polymyxin B. Successful insertion of BPSS1504 into the BpΔBPSS1504 recipient strain was verified by PCR. The mini-Tn7 elements were transposed to the att Tn7 site downstream of the glutamine-6-phosphate synthase-encoding gene glmS2 on chromosome 2, as verified by PCR.

TABLE 2.

PCR primers used for construction of plasmids

| Primer name | Sequence (5′→3′)a | PCR amplification |

|---|---|---|

| OT182-RT | 5′-ACATGGAAGTCAGATCCTGG-3′ | Sequencing primer for identification of Tn5-OT182 integration site |

| BPSS1504up_for1a | 5′-CGACGACCCAGTTCGACCTGAAG-3′ | Forward primer for BPSS1504 upstream fragment |

| BPSS1504up_rev2a | 5′-CGTGTGAACGAGGTCGGACATGGAAGGATCCGAACGAATGCGCGGCTCAG-3′ | Reverse primer for BPSS1504 upstream fragment |

| BPSS1504dn_for2a | 5′-CGGCTGAGCCGCGCATTCGTTCGGATCCTTCCATGTCCGACCTCG TTCAC-3′ | Forward primer for BPSS1504 downstream fragment |

| BPSS1504dn_rev1a | 5′-AGGTCCGCGTCGAAGAACATCGTC-3′ | Reverse primer for BPSS1504 downstream fragment |

| BPSS1504KOver_for | 5′-AGCTCGACGAAGGCAAGATCG-3′ | Primer 195 bp upstream of BPSS1504 ORF |

| BPSS1504KOver_rev | 5′-TCAGGTCGCATTGCAGCCAG-3′ | Primer 208 bp downstream of BPSS1504 ORF |

| BPSS1504for-HindIII | 5′-CCGCTAGCTAAAGCTTATGAAAATCGTCAAACCCGAAACG-3′ | Forward primer for BPSS1504 ORF |

| BPSS1504rev-KpnI | 5′-CCGATCACTTGGTACCTGGAAGGCGTCGAGGGAATC-3′ | Reverse primer for BPSS1504 ORF |

| Hcp1up_for | 5′-GTGACCGATCTGCCGCTCTAC-3′ | Forward primer for hcp1 upstream fragment |

| Hcp1up_rev | 5′-CCCGCGACGATTCGCGATCAGCCATTCTGAGATATATTCCGGCCAGCATG-3′ | Reverse primer for hcp1 upstream fragment |

| Hcp1dn_for | 5′-GCGCCATGCTGGCCGGAATATATCTCAGAATGGCTGATCGCGAATCGTCG-3′ | Forward primer for hcp1 downstream fragment |

| Hcp1dn_rev | 5′-AGGCGAACGAGCTCGTCCTCG-3′ | Reverse primer for hcp1 downstream fragment |

| Tn7L | 5′-ATTAGCTTACGACGCTACACCC-3′ | Primer annealing to the Tn7 transposon left end |

| BPGLMS1 | 5′-GAGGAGTGGGCGTCGATCAAC-3′ | Primer downstream of glmS1 |

| BPGLMS2 | 5′-ACACGACGCAAGAGCGGAATC-3′ | Primer downstream of glmS2 |

| BPGLMS3 | 5′-CGGACAGGTTCGCGCCATGC-3′ | Primer downstream of glmS3 |

HindIII and KpnI restriction sites are underlined.

Cell lines.

The rat-kangaroo kidney epithelial cell line Ptk2 and the human lung epithelial cell line A549 were cultivated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). The murine macrophage-like cell line RAW264.7 (RAW) was cultured in DMEM containing the FCS supplement 4% Panexin BMM (PAN Biotech, Germany) (25) or in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS.

Animal infection experiments.

Female 8- to 12-week-old BALB/c mice were purchased from Charles River (Germany). Animals were housed under specific-pathogen-free conditions. Mice received the indicated dose of B. pseudomallei strains intranasally and were monitored daily after infection. To evaluate the bacterial burden of internal organs, mice were sacrificed 48 h after infection, and their lungs, spleens, and livers were homogenized and plated onto Ashdown agar plates in appropriate dilutions. Data are presented as the total bacterial count per organ. All in vivo studies were approved by the local authorities.

BMM.

C57BL/6 and Caspase-1−/− mice were described previously (26). Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMM) were generated and cultivated in a serum-free cell culture system as recently described (25). Briefly, tibias and femurs were removed aseptically, and bone marrow cells were flushed with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and centrifuged at 450 × g for 10 min. Cells were resuspended in RPMI medium containing 5% Panexin BMM (PAN Biotech), 2 ng/ml recombinant murine granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (PAN Biotech), and 50 μM mercaptoethanol and cultivated for 10 days at 37°C and 5% CO2. Twenty-four hours prior to infection experiments, BMM were harvested and seeded in well plates as indicated.

Invasion and replication assays.

To determine the bactericidal capacity of mammalian cells, the respective cell lines or primary macrophages were seeded in 48-well plates (BMM, 1.5 × 105; A549, 5 × 104; RAW, 9 × 104 cells per well) and infected with B. pseudomallei strains at the indicated multiplicity of infection (MOI) for 30 min. Cells were washed twice with PBS, and medium containing 125 μg/ml Km was added to each well. At the indicated time points (with time zero taken as 20 min after incubation under antibiotic-containing medium), the number of intracellular CFU was determined as previously described (27).

MNGC formation assay.

RAW cells were seeded in an 8-well chamber slide (Nagle Nunc International) with 4.5 × 104 cells per well in 200 μl medium 18 to 24 h prior to infection. Cells were infected at an MOI of ∼2 of B. pseudomallei strains for 30 min and washed twice with PBS, medium containing 125 μg/ml Km was added, and the cells were further incubated for 16 h. Cells were washed three times with PBS and fixed with methanol before Giemsa staining was performed. For enumeration of MNGC formation, approximately 800 nuclei per well were counted, and the percentage of MNGC formation was calculated as follows: % MNGC formation = (no. of nuclei within MNGC/total no. of nuclei) × 100.

Actin tail formation assay.

Ptk2 cells were seeded on cover slides in 24-well plates (1.2 × 105 cells per well) 1 day prior to infection. Cells were infected with the respective B. pseudomallei strains (MOI of ∼60). Bacteria were centrifuged onto the cells at 400 × g for 4 min before plates were incubated for 45 min at 37°C and 5% CO2. Infected cells were washed with PBS, and medium containing 250 μg/ml kanamycin was added to each well. After 3 h and 6 h of further incubation, cells were washed three times with PBS and incubated for at least 15 min in methanol at −20°C. After additional washing steps, cells were incubated in IF buffer (0.2% bovine serum albumin [BSA], 0,05% saponin; 0,1% sodium acid in PBS [pH 7.4]) for 1 h to prevent unspecific antibody binding. Cells were then incubated with the monoclonal mouse anti-B. pseudomallei extracellular polysaccharide (EPS) antibody 3015γ2b (7) and polyclonal rabbit anti-β-actin antibody (Cell Signaling, Frankfurt am Main, Germany) overnight at 4°C. After the washing steps, cells were incubated with the secondary antibodies Alexa Fluor 488 anti-mouse IgG2b (Invitrogen, Germany) and Cy3-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Dianova, Germany) for 1 h before slides were covered with Fluoprep (bioMérieux, Germany). Intracellular bacteria and their association with actin filaments were visualized by fluorescence microscopy with a BZ-9000 microscope (Keyence Corporation). Images were analyzed with the BZ-image viewer and BZ-analyzer version 1.4.

LDH assay.

To quantify the extent of cell damage after infection, release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) in cell culture supernatants was determined. BMM were seeded in 96-well plates (3 × 104 cells per well) and infected at the indicated MOI with B. pseudomallei strains for 30 min. Cells were washed twice with PBS, and 100 μl of medium containing 125 μg/ml Km was added to each well to eliminate extracellular bacteria. At the indicated time points, cell culture supernatant was collected, and LDH activity was detected by using the CytoTox-One homogeneous membrane integrity assay kit (Promega Corp., Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 50 μl of the supernatant was added to the kit reagent, and the mixture was incubated for 10 min. After addition of stopping solution, the fluorescence intensity (excitation wavelength, 560 nm; emission wavelength, 590 nm) was measured using a microplate reader (Infinite type M200 Pro; Tecan).

Real-time cell status analysis.

RAW264.7 cells were seeded in 96-well E-plates (2 × 104 cells per well) and grown for 24 h at 37°C and 5% CO2, before they were infected with the indicated B. pseudomallei strains (MOI of ∼20) for 30 min. Cells were further incubated in medium containing 125 μg/ml Km for 6 days. Cellular events were monitored in real time by measuring the electrical impedance across microelectrodes integrated in the bottom of the E-plates using the xCELLigence system (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). The xCELLigence system calculates changes in impedance as a dimensionless parameter called the “cell index.”

RNA isolation and gene expression analysis.

RAW cells were seeded in 6-well plates (6.5 × 105 cells per well) and infected with B. pseudomallei (MOI of ∼100) for 30 min following incubation in Km-containing medium. Total RNA was isolated after 2 h and 5 h of incubation time using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). DNA was removed from the samples using DNase I (Fermentas). Reverse transcription was performed using Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase and random primers (both from Promega). T3SS and T6SS genes were analyzed using the Maxima SYBR green quantitative PCR (qPCR) master mix (Fermentas) in a Light Cycler 480 (Light Cycler software version 1.5; Roche). The relative mRNA levels of genes were calculated with the Efficiency method using 16S rRNA as the reference gene. Each assay was performed in duplicate. The PCR primers are listed in Table 3. Expression analysis of BPSS1504 was not successful using Taq polymerase-based real-time PCR, and results were verified by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR using KOD HotStart polymerase (Novagen). The 23S rRNA served as a reference gene. PCR products were visualized after electrophoresis through a 1.5% agarose gel containing SybrSafe (Invitrogen).

TABLE 3.

List of PCR primers used for expression analysis

| Gene | Sequence (5′→3′) |

|---|---|

| BPSS1504 | 5′-CACGATCGACGACGAAGAC-3′ |

| 5′-ATGTTCGTCGGCGTGCGCTTC-3′ | |

| bsaN | 5′-AATAAATCGGCGCTGGTTATCGGC-3′ |

| 5′-AGCAATTTCGCCGCCTCGAATAAC-3′ | |

| bprC | 5′-GCGGAACAGCCGATAGAG-3′ |

| 5′-CATCGAGCAGCATCTTCATC-3′ | |

| vgrG | 5′-CTCACGTCCGGCAACAAGTTC-3′ |

| 5′-TTGCCGCCCATCGACACC-3′ | |

| tssA | 5′-GTCGACAAGGACGACTTCAA-3′ |

| 5′-GAGCGTGAGCTGGAGGTT-3′ | |

| hcp1 | 5′-GATCACCCACATGGACCAATAC-3′ |

| 5′-TGCCCGATTCCGCGTGTTC-3′ | |

| virG | 5′-CCCCATAGCGTCTCCACCTC-3′ |

| 5′-GATCCGAAGCATCCCGAACTG-3′ | |

| 23S rRNA | 5′-TTTCCCGCTTAGATGCTTT-3′ |

| 5′-AAAGGTACTCTGGGGATAA-3′ | |

| 16S rRNA | 5′-GGCTAGTCTAACCGCAAGGA-3′ |

| 5′-TCCGATACGGCTACCTTGTT-3′ |

Western blot analysis.

To analyze Hcp1 secretion of B. pseudomallei, we infected RAW cells with the indicated B. pseudomallei strains. Twenty-four hours prior to infection, 107 RAW cells were seeded into 250-ml cell culture flasks. Cells were infected with B. pseudomallei strains (MOI as indicated) for 30 min. The infected cells were then incubated in medium containing 250 μg/ml Km for 16 h and subsequently lysed with 10 ml TNE-Triton (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-114) containing one tablet of Complete Mini Protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). To remove intracellular bacteria, cell lysates were centrifuged for 10 min at 12,000 × g and 4°C and subsequently filtrated (pore size, 0.22 μm; Acrodisc). Proteins were precipitated by addition of 15 ml isopropanol and then incubated at 4°C for at least 30 min. Proteins were harvested by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 15 min and washed twice with 100% ethanol. Protein pellets were air dried, resuspended in 8 M urea–2 M thiourea, and stored at −20°C. To obtain a DnaK-positive sample, 0.8 ml from the unfiltered lysate of B. pseudomallei WT-infected cells was heat inactivated prior to precipitation of the proteins. Equal amounts of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked with Roti-Block (Roth) for 1 h at room temperature and subsequently incubated overnight at 4°C with either anti-Hcp1, anti-DnaK (Abcam), or anti-GAPDH (anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) antibodies (Cell Signaling), respectively. Polyclonal mouse anti-Hcp1 serum was kindly provided by D. DeShazer (U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, Fort Detrick, MD). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG was used as a secondary antibody (Cell Signaling) for 1 h at room temperature. The LumiGLO system (Cell Signaling) was used for detection. Membranes were analyzed using the Fusion FX 7 machine and Fusion 1 software (Peqlab).

Statistics.

To determine significant differences between groups, either Student's t test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test followed by Bonferroni's posttest was used as indicated for each experiment. Survival curves were compared using the log rank Kaplan-Meier test. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 4.0.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Identification of the BPSS1504 locus as an essential component for the intact intracellular life cycle of B. pseudomallei.

We previously screened B. pseudomallei transposon mutants for defects in the intracellular life cycle by using the plaque-assay screening approach that led us to identify various genes contributing to in vivo virulence of B. pseudomallei (7, 23). Using this approach, a mutant in which the BPSS1504 locus was disrupted showed strong delayed plaque formation (data not shown). However, this transposon mutant exhibited a rather untypical yellowish colony morphology, which might be caused by polar side effects of the transposable element. We therefore constructed a markerless deletion mutant (BpΔBPSS1504) strain and a complemented mutant (BpΔBPSS1504::BPSS1504) strain to exclude unspecific side effects for further analyses. The deletion mutant as well as the complemented mutant exhibited normal, characteristic B. pseudomallei morphology.

BPSS1504 codes for a hypothetical protein that is located within cluster 1 of the six T6SS apparatuses that are present in B. pseudomallei. BPSS1504 is also designated gene locus “tag-AB” according to Shalom et al. (11) or “tssF” in B. mallei according to Schell et al. (12). The gene BMAA0736 from B. mallei shares ∼99% similarity with BPSS1504, and gene BTH_II0862 from B. thailandensis (E264) shares ∼85% similarity. The C terminal of BPSS1504 contains a pentapeptide repeat domain exhibiting homologies to other pentapeptide repeat proteins, such as MfpA of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Qnr of Enterococcus faecalis (28, 29). The pentapeptide repeat domains of MfpA and Qnr were shown to inhibit the DNA-gyrase by mimicking the B-form of DNA and therefore confer resistance against fluoroquinolone by protecting bacterial DNA from the detrimental activity of these antibiotics (28–30). Anyway, B. pseudomallei strains lacking the BPSS1504 locus did not show any differences in the susceptibility against fluoroquinolones, such as ciprofloxacin (data not shown). Other T6SS genes of B. pseudomallei also contain pentapeptide repeat domains, such as BPSS0526, contained within T6SS cluster 2, and BPSS0182/0183, located within T6SS cluster 4 (12). The functions of these genes have not been addressed yet. Interestingly, the T3SS effector proteins PipB and PipB2 from Salmonella spp. also contain pentapeptide repeat domains. PipB2 was shown to contribute to the formation of Salmonella-induced filaments. However, the exact role of the pentapeptide domain in PipB2 is still unclear (31, 32).

Basic characterization of the BpΔBPSS1504 deletion mutant revealed normal growth in LB and minimal Vogel-Bonner medium. No significant differences in motility and biofilm formation compared to the WT strain E8 were observed (data not shown).

The BpΔBPSS1504 mutant is highly attenuated in mice.

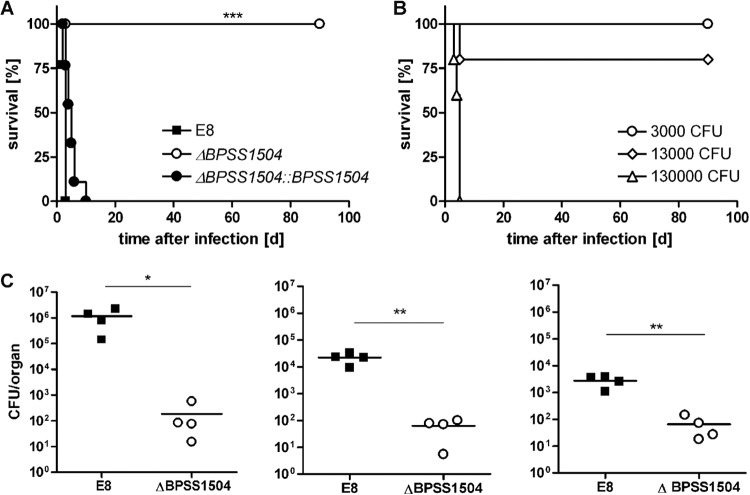

To examine whether single deletion of BPSS1504 might be associated with in vivo virulence, we infected BALB/c mice intranasally with approximately ∼300 to 600 CFU of either the B. pseudomallei WT, BpΔBPSS1504 mutant, or complemented mutant strain. Mice infected with WT bacteria succumbed within the first days after infection, whereas BpΔBPSS1504 strain-infected mice survived for the observed period of time (Fig. 1A). Animals were sacrificed at day 62 (n = 5) or 118 (n = 4) after infection, and no remaining bacteria were detected in lung, liver, and spleen. Significant differences in the bacterial loads in these organs were detected 48 h after infection with 30 CFU (Fig. 1C). Complementation of the mutant fully restored the ability to cause disease in vivo (Fig. 1A). Infection with various doses of the BpΔBPSS1504 strain revealed that mice eventually succumbed within 5 days when receiving very high infection doses (1.3 × 105 CFU) (Fig. 1B), showing that disruption of BPSS1504 led to strong attenuation but did not render the pathogen completely avirulent.

FIG 1.

Intranasal infection of BALB/c mice. (A) Mortality curves of animals (n = 9) infected with the B. pseudomallei WT (345 to 690 CFU), BpΔBPSS1504 mutant (220 to 560 CFU), and BpΔBPSS1504::BPSS1504 complemented mutant strain (295 to 474 CFU). Curves were compared by using the log rank Kaplan-Meier test. Pooled data from two independent experiments are shown. (B) Mortality curves of animals infected with 3 × 103, 1.3 × 104, and 1.3 × 105 CFU of the BpΔBPSS1504 mutant. Data from a single experiment are shown. (C) Determination of bacterial loads in lung, spleen, and liver (n = 4) 48 h after infection with ∼30 CFU. Data from a single experiment are shown. Significant differences were calculated using Student's t test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

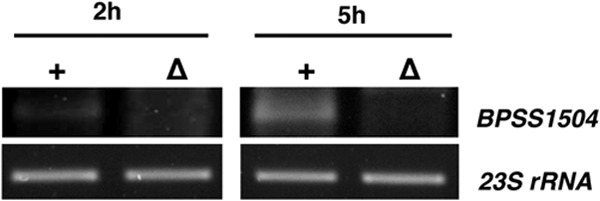

BPSS1504 is expressed upon infection of macrophages.

We next evaluated whether BPSS1504 is expressed during infection of host cells. It was recently shown that the expression of various T6SS1 genes increased after internalization of B. pseudomallei in RAW macrophages and peaked around 5 to 6 h after infection (19, 33). As shown in Fig. 2, we found BPSS1504 to be expressed in B. pseudomallei after internalization of RAW macrophages and that the expression level increased from 2 h to 5 h after infection.

FIG 2.

mRNA expression analysis of BPSS1504 in B. pseudomallei WT (+) and BpΔBPSS1504 mutant strain (Δ) 2 h and 5 h after infection of RAW macrophages. cDNA was subjected to PCR using BPSS1504-specific primers, and PCR products were visualized after gel electrophoresis. One out of two experiments with similar results is shown.

BPSS1504 contributes to the intracellular replication of B. pseudomallei in mammalian cells.

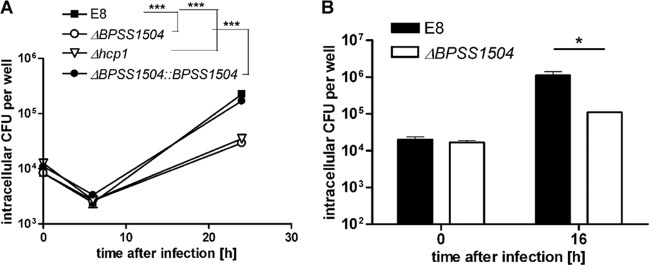

Having shown that BPSS1504 is expressed upon intracellular infection, we examined the role of BPSS1504 in invasion and intracellular replication by infecting phagocytic and nonphagocytic cells. As shown in Fig. 3A, we did not find significant differences in the uptake of WT bacteria and BpΔBPSS1504 mutant bacteria by primary macrophages. However, the ability to multiply inside these cells was reduced after infection with the BpΔBPSS1504 strain. A similar phenotype was found in a BpΔhcp1 mutant strain lacking a functional T6SS1 (Fig. 3A). This is in accordance with a report describing impaired intracellular replication of a BpΔhcp1 mutant in RAW cells (10). Complementation of the ΔBPSS1504 strain fully restored the ability to replicate within macrophages (Fig. 3A). Normal invasion but impaired intracellular replication of the BpΔBPSS1504 strain was also detected in the human lung epithelial cell line A549 (Fig. 3B). Thus, BPSS1504 does not seem to have any role in active invasion but codetermines the ability to replicate inside host cells, as was shown for other T6SS1 genes, such as hcp1, or in the absence of the T6SS regulator genes virAG (10, 19; this study).

FIG 3.

Invasion and intracellular replication assays. (A) Infection of BALB/c BMM (MOI of ∼4) with the B. pseudomallei WT, BpΔBPSS1504 mutant, BpΔBPSS1504::BPSS1504 complemented mutant, and BpΔhcp1 mutant. (B) Infection of A549 cells (MOI of ∼20). Values are means ± standard deviations from triplicate determinations. One out of three independent experiments with similar results is shown. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's posttest. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001.

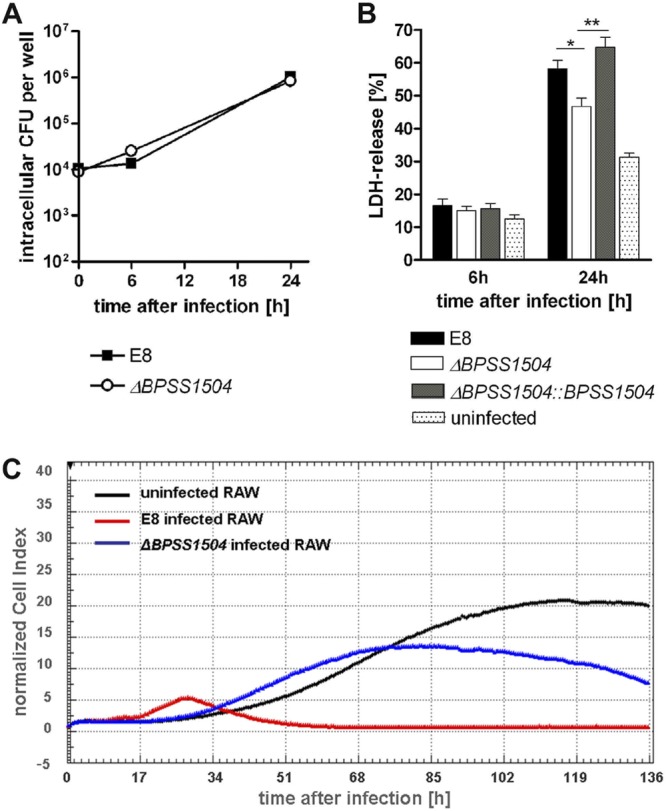

BPSS1504 contributes to the induction of cell death in macrophages.

We next assessed whether BPSS1504 might be involved in the induction of cell death. In preliminary experiments, we found reduced LDH release in C57BL/6 BMM 20 h after infection with BpΔBPSS1504 bacteria compared to WT bacteria (data not shown). However, this could be explained by the fact that lower intracellular bacterial load in BpΔBPSS1504 strain-infected cells (Fig. 3A) per se might have caused reduced cytotoxicity. We therefore were seeking for intracellular conditions in which WT and mutant bacteria show comparable intracellular growth kinetics. Recently, we reported that macrophages lacking caspase-1 exhibited impaired killing activity against B. pseudomallei (3). Testing of the intracellular survival kinetics in these cells revealed comparable intracellular replication kinetics of the WT and BpΔBPSS1504 mutant in the absence of caspase-1 (Fig. 4A). Under these conditions, we still found the BpΔBPSS1504 mutant to cause slightly but significantly reduced LDH release in macrophages compared to the maternal strain E8, whereas complementation of BPSS1504 compensated the observed phenotype to the WT level (Fig. 4B). In addition, we monitored the cell status of RAW cells infected with the B. pseudomallei WT and BpΔBPSS1504 mutant by real-time cell status analysis for several days (for details, see Materials and Methods). As shown in Fig. 4C, cells infected with WT B. pseudomallei detached from the button of the culture plate within 42 h after infection. In contrast, cells infected with the BpΔBPSS1504 strain were able to divide and grow for another 2 days: after that, the number of adherent cells only slowly decreased. Thus, BPSS1504 is clearly involved in cytotoxic effects caused by B. pseudomallei.

FIG 4.

Effects of BPSS1504 deletion on the cytotoxicity caused by B. pseudomallei. (A) Invasion and intracellular replication of the B. pseudomallei WT and BpΔBPSS1504 mutant (MOI of ∼4) in caspase-1−/− BMM. (B) LDH release after infection of caspase-1−/− BMM with the B. pseudomallei WT, BpΔBPSS1504 mutant, and BpΔBPSS1504::BPSS1504 complemented mutant (MOI of ∼5). Values are means ± standard deviations from triplicate determinations. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's posttest. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. (C) Real-time cell status analysis of RAW cells. One out of three independent experiments with similar results is shown.

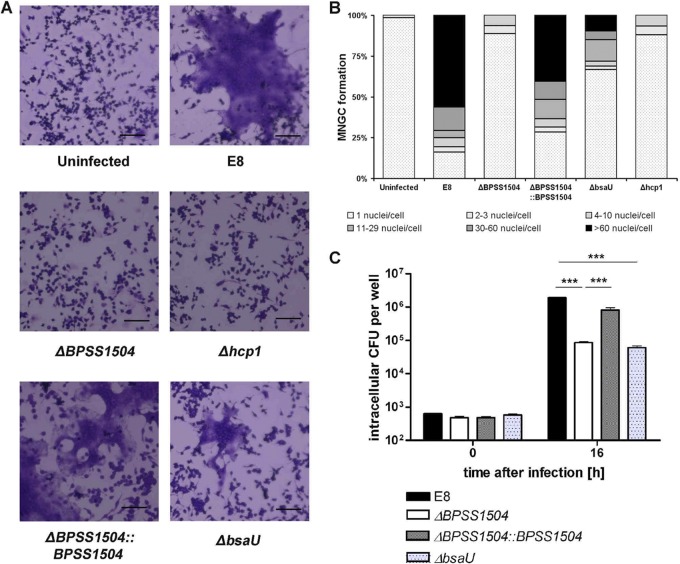

BPSS1504 contributes to the formation of MNGC.

T6SS proteins, such as Hcp1, are known to be involved in the induction of MNGC formation of macrophages after B. pseudomallei and Burkholderia mallei infection (10, 19, 34). We therefore assessed and quantified the ability of the BpΔBPSS1504 mutant to induce MNGC in RAW macrophages. We found that impaired MNGC formation in the absence of BPSS1504 showed a comparable level to the MNGC formation of cells infected with B. pseudomallei lacking hcp1 (Fig. 5A and B). To exclude that this phenotype might simply be due to the decreased intracellular bacterial load compared to that of WT bacteria (Fig. 5C), a B. pseudomallei mutant with a defect in the bsaU gene (BpΔbsaU) belonging to the apparatus of the T3SS cluster 3 was included as a control. The BpΔbsaU strain was previously found to be trapped within LAMP-1-positive lysosomes after infection and showed delayed escape into the cytosol (7, 35). In addition, the T3SS3 bsa locus was reported not to be directly required for MNGC formation (36). Infection of RAW cells with the BpΔbsaU mutant resulted in similar intracellular bacterial loads compared with the BpΔBPSS1504 mutant (Fig. 5C). However, the BpΔbsaU mutant clearly was able to induce more MNGC than the BpΔBPSS1504 and BpΔhcp1 mutants (Fig. 5A and B). The ability to induce MNGC was fully restored to the WT level in the BpΔBPSS1504::BPSS1504 complemented mutant strain (Fig. 5A and B). These data clearly implicate a role for BPSS1504 in MNGC formation to a similar degree as in the BpΔhcp1 strain.

FIG 5.

Induction of MNGC formation in RAW macrophages after infection. (A) Representative details from RAW cells infected with the B. pseudomallei WT, BpΔBPSS1504 mutant, BpΔBPSS1504::BPSS1504 complemented mutant, BpΔhcp1 mutant, and BpΔbsaU mutant (MOI of ∼2) are shown. (B) Percentage of MNGC after infection (MOI of ∼2). (C) Intracellular replication of the B. pseudomallei WT, BpΔBPSS1504 mutant, BpΔBPSS1504::BPSS1504 complemented mutant, and BpΔbsaU mutant (MOI of ∼2). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's posttest. ***, P < 0.001. One out of three independent experiments with similar results is shown.

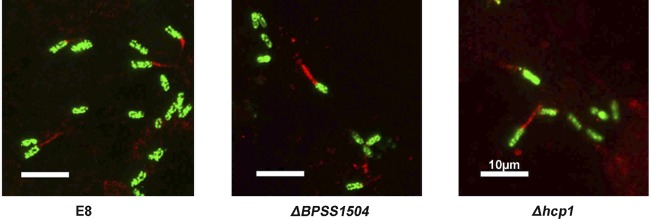

BPSS1504 and hcp1 do not influence the formation of actin tails.

When assessing the ability of the BpΔBPSS1504 mutant to induce the formation of actin tails in PtK2 cells by immunofluorescence microscopy, we found the mutant formed normal actin tails like the WT bacteria (Fig. 6). It was shown that the T6SS regulator virAG regulates expression of bimA (19), the gene responsible for actin tail formation (37–39). However, normal actin tail formation in the absence of BPSS1504 was in accordance with the fact that the BpΔBPSS1504 strain exhibited normal expression of bimA in HepG2 and RAW macrophages, as verified by semiquantitative RT-PCR (data not shown). To our knowledge, the formation of actin tails in a BpΔhcp1 mutant has not been described so far. Similar to B. pseudomallei lacking BPSS1504 expression, we did not find the BpΔhcp1 mutant to exhibit defects in the formation of actin tails (Fig. 6). Thus, single deletion of either BPSS1504 or hcp1 does not seem to affect actin polymerization.

FIG 6.

Actin tail formation of the B. pseudomallei WT and BpΔBPSS1504 and BpΔhcp1 mutants. Representative details from infected Ptk2 cells (MOI of ∼60) are shown. Red indicates cells stained with anti-β-actin and Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody for actin labeling, and green indicates bacteria stained with anti-EPS and secondary Alexa Fluor antibody.

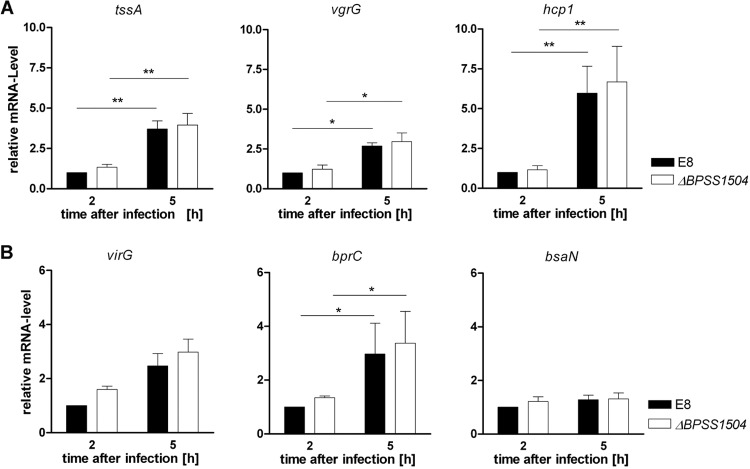

Expression of various T6SS1 genes and T6SS regulators was normal in the absence of BPSS1504.

Having shown that lack of BPSS1504 in B. pseudomallei clearly resulted in classical T6SS-associated phenotypes that are similar to that of a BpΔhcp1 mutant (10; this study), we were interested in whether expression of hcp1 or other T6SS1-related components might be affected in the BpΔBPSS1504 mutant. Since T6SS1 genes are upregulated in B. pseudomallei upon internalization in eukaryotic host cells, we infected RAW cells with B. pseudomallei to ensure that BPSS1504 is expressed at a relevant level (Fig. 2). Consistent with data from others (19, 33), we found significantly increased expression of essential T6SS1 components, such as vgrG, tssA, and hcp1 in B. pseudomallei 5 h after infection of macrophages (Fig. 7A). However, no significant difference in mRNA expression of these genes was detected in the BpΔBPSS1504 mutant compared to that of the maternal strain, E8 (Fig. 7A). In addition, expression of the T6SS regulators virG, bprC, and bsaN was not altered in the absence of BPSS1504 (Fig. 7B). Thus, BPSS1504 does not seem to have regulatory functions for the expression of T6SS1-associated genes.

FIG 7.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of T6SS genes and regulators in the B. pseudomallei WT and BpΔBPSS1504 mutant after internalization in RAW macrophages (MOI of ∼100). (A) Expression analysis of the T6SS1 components tssA, vgrG, and hcp1. (B) Expression analysis of the T6SS1 regulator genes virG, bprC, and bsaN. Statistical analyses were performed using Student's t test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. Values are the means ± standard deviations from four independent experiments.

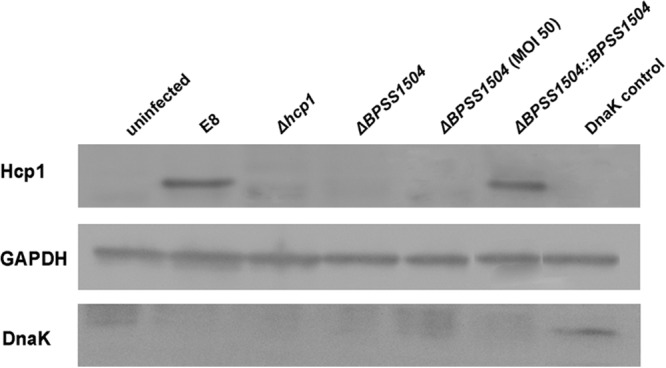

Lack of BPSS1504 impairs Hcp1 secretion.

Since BPSS1504 deletion resulted in phenotypes that resembled a BpΔhcp1 mutant without affecting the expression of hcp1 and other T6SS1 key genes (Fig. 7), we next assessed whether BPSS1504 might affect the integrity of the T6SS1 apparatus. Since normal Hcp secretion is considered to be a reliable indicator for a functional T6SS (18, 21, 40), we tested the ability of the BpΔBPSS1504 mutant to secrete Hcp1 into host cells. For that purpose we infected RAW macrophages with the B. pseudomallei WT, the BpΔBPSS1504 mutant, and the complemented mutant strain. The BpΔhcp1 mutant was included as a negative control. As shown in Fig. 8, Hcp1 was detectable in cells after infection with WT bacteria and the BpΔBPSS1504::BPSS1504 complemented strain at an MOI of 2, whereas we were not able to detect secreted Hcp1 in the ΔBPSS1504 mutant strain, even after infection with the high doses (MOI of ∼50). Absence of the bacterial cytosolic protein DnaK from all samples indicated that Hcp1 was not present due to lysed bacteria.

FIG 8.

Secretion of Hcp1 within RAW cells by Western blot analysis. RAW cells were infected with the indicated B. pseudomallei strains for 30 min at an MOI of ∼2, if not stated otherwise, and incubated for 16 h in Km-containing medium. Proteins were harvested after removal of intracellular bacteria by filtration (for further details, see Materials and Methods). A DnaK-positive control was obtained by harvesting B. pseudomallei-infected RAW cells without removing the remaining bacteria.

Together, we found BPSS1504 to be an important component involved in the T6SS1-dependent virulence of B. pseudomallei. The BpΔBPSS1504 mutant exhibited a similar phenotype to a BpΔhcp1 mutant, including normal invasion and actin tail formation but impaired intracellular replication and a severely reduced ability to induce MNGC formation. While expression of T6SS regulator and effector genes, including hcp1, was not changed in the absence of BPSS1504, we found BPSS1504 to affect Hcp1 secretion. Thus, BPSS1504 seems to be involved in the functionality and integrity of the T6SS1 apparatus.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

V.H. was supported by a grant of the Graduate College 840 (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) to I.S. and K.B.

We are grateful to Mark. P. Stevens and David DeShazer for providing antibodies. We thank Claudia Wiede for excellent technical assistance.

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 4 March 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Limmathurotsakul D, Peacock SJ. 2011. Melioidosis: a clinical overview. Br. Med. Bull. 99:125–139. 10.1093/bmb/ldr007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes JL, Ketheesan N. 2005. Route of infection in melioidosis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11:638–639. 10.3201/eid1104.041051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peacock SJ. 2006. Melioidosis. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 19:421–428. 10.1097/01.qco.0000244046.31135.b3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones AL, Beveridge TJ, Woods DE. 1996. Intracellular survival of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Infect. Immun. 64:782–790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breitbach K, Rottner K, Klocke S, Rohde M, Jenzora A, Wehland J, Steinmetz I. 2003. Actin-based motility of Burkholderia pseudomallei involves the Arp 2/3 complex, but not N-WASP and Ena/VASP proteins. Cell. Microbiol. 5:385–393. 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00277.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stevens MP, Wood MW, Taylor LA, Monaghan P, Hawes P, Jones PW, Wallis TS, Galyov EE. 2002. An Inv/Mxi-Spa-like type III protein secretion system in Burkholderia pseudomallei modulates intracellular behaviour of the pathogen. Mol. Microbiol. 46:649–659. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03190.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pilatz S, Breitbach K, Hein N, Fehlhaber B, Schulze J, Brenneke B, Eberl L, Steinmetz I. 2006. Identification of Burkholderia pseudomallei genes required for the intracellular life cycle and in vivo virulence. Infect. Immun. 74:3576–3586. 10.1128/IAI.01262-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lazar Adler NR, Govan B, Cullinane M, Harper M, Adler B, Boyce JD. 2009. The molecular and cellular basis of pathogenesis in melioidosis: how does Burkholderia pseudomallei cause disease? FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 33:1079–1099. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00189.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galyov EE, Brett PJ, DeShazer D. 2010. Molecular insights into Burkholderia pseudomallei and Burkholderia mallei pathogenesis. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 64:495–517. 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burtnick MN, Brett PJ, Harding SV, Ngugi SA, Ribot WJ, Chantratita N, Scorpio A, Milne TS, Dean RE, Fritz DL, Peacock SJ, Prior JL, Atkins TP, Deshazer D. 2011. The cluster 1 type VI secretion system is a major virulence determinant in Burkholderia pseudomallei. Infect. Immun. 79:1512–1525. 10.1128/IAI.01218-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shalom G, Shaw JG, Thomas MS. 2007. In vivo expression technology identifies a type VI secretion system locus in Burkholderia pseudomallei that is induced upon invasion of macrophages. Microbiology 153:2689–2699. 10.1099/mic.0.2007/006585-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schell MA, Ulrich RL, Ribot WJ, Brueggemann EE, Hines HB, Chen D, Lipscomb L, Kim HS, Mrazek J, Nierman WC, Deshazer D. 2007. Type VI secretion is a major virulence determinant in Burkholderia mallei. Mol. Microbiol. 64:1466–1485. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05734.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pukatzki S, Ma AT, Sturtevant D, Krastins B, Sarracino D, Nelson WC, Heidelberg JF, Mekalanos JJ. 2006. Identification of a conserved bacterial protein secretion system in Vibrio cholerae using the Dictyostelium host model system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:1528–1533. 10.1073/pnas.0510322103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cascales E. 2008. The type VI secretion toolkit. EMBO Rep. 9:735–741. 10.1038/embor.2008.131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Filloux A, Hachani A, Bleves S. 2008. The bacterial type VI secretion machine: yet another player for protein transport across membranes. Microbiology 154:1570–1583. 10.1099/mic.0.2008/016840-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hood RD, Singh P, Hsu F, Guvener T, Carl MA, Trinidad RR, Silverman JM, Ohlson BB, Hicks KG, Plemel RL, Li M, Schwarz S, Wang WY, Merz AJ, Goodlett DR, Mougous JD. 2010. A type VI secretion system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa targets a toxin to bacteria. Cell Host Microbe 7:25–37. 10.1016/j.chom.2009.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russell AB, Hood RD, Bui NK, LeRoux M, Vollmer W, Mougous JD. 2011. Type VI secretion delivers bacteriolytic effectors to target cells. Nature 475:343–347. 10.1038/nature10244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silverman JM, Brunet YR, Cascales E, Mougous JD. 2012. Structure and regulation of the type VI secretion system. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 66:453–472. 10.1146/annurev-micro-121809-151619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Y, Wong J, Sun GW, Liu Y, Tan GY, Gan YH. 2011. Regulation of type VI secretion system during Burkholderia pseudomallei infection. Infect. Immun. 79:3064–3073. 10.1128/IAI.05148-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun GW, Chen Y, Liu Y, Tan GY, Ong C, Tan P, Gan YH. 2010. Identification of a regulatory cascade controlling type III secretion system 3 gene expression in Burkholderia pseudomallei. Mol. Microbiol. 76:677–689. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07124.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burtnick MN, Brett PJ. 2013. Burkholderia mallei and Burkholderia pseudomallei cluster 1 type VI secretion system gene expression is negatively regulated by iron and zinc. PLoS One 8:e76767. 10.1371/journal.pone.0076767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lopez CM, Rholl DA, Trunck LA, Schweizer HP. 2009. Versatile dual-technology system for markerless allele replacement in Burkholderia pseudomallei. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:6496–6503. 10.1128/AEM.01669-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Norville IH, Breitbach K, Eske-Pogodda K, Harmer NJ, Sarkar-Tyson M, Titball RW, Steinmetz I. 2011. A novel FK-506-binding-like protein that lacks peptidyl-prolyl isomerase activity is involved in intracellular infection and in vivo virulence of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Microbiology 157:2629–2638. 10.1099/mic.0.049163-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi KH, Mima T, Casart Y, Rholl D, Kumar A, Beacham IR, Schweizer HP. 2008. Genetic tools for select-agent-compliant manipulation of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:1064–1075. 10.1128/AEM.02430-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eske K, Breitbach K, Kohler J, Wongprompitak P, Steinmetz I. 2009. Generation of murine bone marrow derived macrophages in a standardised serum-free cell culture system. J. Immunol. Methods 342:13–19. 10.1016/j.jim.2008.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Breitbach K, Sun GW, Kohler J, Eske K, Wongprompitak P, Tan G, Liu Y, Gan YH, Steinmetz I. 2009. Caspase-1 mediates resistance in murine melioidosis. Infect. Immun. 77:1589–1595. 10.1128/IAI.01257-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Breitbach K, Klocke S, Tschernig T, van Rooijen N, Baumann U, Steinmetz I. 2006. Role of inducible nitric oxide synthase and NADPH oxidase in early control of Burkholderia pseudomallei infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 74:6300–6309. 10.1128/IAI.00966-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hegde SS, Vetting MW, Roderick SL, Mitchenall LA, Maxwell A, Takiff HE, Blanchard JS. 2005. A fluoroquinolone resistance protein from Mycobacterium tuberculosis that mimics DNA. Science 308:1480–1483. 10.1126/science.1110699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vetting MW, Hegde SS, Zhang Y, Blanchard JS. 2011. Pentapeptide-repeat proteins that act as topoisomerase poison resistance factors have a common dimer interface. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 67:296–302. 10.1107/S1744309110053315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tran JH, Jacoby GA. 2002. Mechanism of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:5638–5642. 10.1073/pnas.082092899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henry T, Couillault C, Rockenfeller P, Boucrot E, Dumont A, Schroeder N, Hermant A, Knodler LA, Lecine P, Steele-Mortimer O, Borg JP, Gorvel JP, Meresse S. 2006. The Salmonella effector protein PipB2 is a linker for kinesin-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:13497–13502. 10.1073/pnas.0605443103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knodler LA, Steele-Mortimer O. 2005. The Salmonella effector PipB2 affects late endosome/lysosome distribution to mediate Sif extension. Mol. Biol. Cell 16:4108–4123. 10.1091/mbc.E05-04-0367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chieng S, Carreto L, Nathan S. 2012. Burkholderia pseudomallei transcriptional adaptation in macrophages. BMC Genomics 13:328. 10.1186/1471-2164-13-328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burtnick MN, DeShazer D, Nair V, Gherardini FC, Brett PJ. 2010. Burkholderia mallei cluster 1 type VI secretion mutants exhibit growth and actin polymerization defects in RAW 264.7 murine macrophages. Infect. Immun. 78:88–99. 10.1128/IAI.00985-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bast A, Schmidt IH, Brauner P, Brix B, Breitbach K, Steinmetz I. 2011. Defense mechanisms of hepatocytes against Burkholderia pseudomallei. Front. Microbiol. 2:277. 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.French CT, Toesca IJ, Wu TH, Teslaa T, Beaty SM, Wong W, Liu M, Schroder I, Chiou PY, Teitell MA, Miller JF. 2011. Dissection of the Burkholderia intracellular life cycle using a photothermal nanoblade. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:12095–12100. 10.1073/pnas.1107183108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stevens JM, Ulrich RL, Taylor LA, Wood MW, Deshazer D, Stevens MP, Galyov EE. 2005. Actin-binding proteins from Burkholderia mallei and Burkholderia thailandensis can functionally compensate for the actin-based motility defect of a Burkholderia pseudomallei bimA mutant. J. Bacteriol. 187:7857–7862. 10.1128/JB.187.22.7857-7862.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sitthidet C, Korbsrisate S, Layton AN, Field TR, Stevens MP, Stevens JM. 2011. Identification of motifs of Burkholderia pseudomallei BimA required for intracellular motility, actin binding, and actin polymerization. J. Bacteriol. 193:1901–1910. 10.1128/JB.01455-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stevens MP, Stevens JM, Jeng RL, Taylor LA, Wood MW, Hawes P, Monaghan P, Welch MD, Galyov EE. 2005. Identification of a bacterial factor required for actin-based motility of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Mol. Microbiol. 56:40–53. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04528.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pukatzki S, McAuley SB, Miyata ST. 2009. The type VI secretion system: translocation of effectors and effector-domains. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 12:11–17. 10.1016/j.mib.2008.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Phadnis SH, Das HK. 1987. Use of the plasmid pRK 2013 as a vehicle for transposition in Azotobacter vinelandii. J. Biosci. 12:131–135. 10.1007/BF02702964 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wuthiekanun V, Smith MD, Dance DA, Walsh AL, Pitt TL, White NJ. 1996. Biochemical characteristics of clinical and environmental isolates of Burkholderia pseudomallei. J. Med. Microbiol. 45:408–412. 10.1099/00222615-45-6-408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Merriman TR, Lamont IL. 1993. Construction and use of a self-cloning promoter probe vector for Gram-negative bacteria. Gene 126:17–23. 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90585-Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bast A, Krause K, Schmidt I, Pudla M, Brakopp S, Hopf V, Breitbach K, Steinmetz I. Caspase-1-dependent and -independent cell death pathways in Burkholderia pseudomallei type infection of macrophages. PLoS Pathog., in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]