ABSTRACT

pUL34 and pUL31 of herpes simplex virus (HSV) comprise the nuclear egress complex (NEC) and are required for budding at the inner nuclear membrane. pUL31 also associates with capsids, suggesting it bridges the capsid and pUL34 in the nuclear membrane to initiate budding. Previous studies showed that capsid association of pUL31 was precluded in the absence of the C terminus of pUL25, which along with pUL17 comprises the capsid vertex-specific complex, or CVSC. The present studies show that the final 20 amino acids of pUL25 are required for pUL31 capsid association. Unexpectedly, in the complete absence of pUL25, or when pUL25 capsid binding was precluded by deletion of its first 50 amino acids, pUL31 still associated with capsids. Under these conditions, pUL31 was shown to coimmunoprecipitate weakly with pUL17. Based on these data, we hypothesize that the final 20 amino acids of pUL25 are required for pUL31 to associate with capsids. In the absence of pUL25 from the capsid, regions of capsid-associated pUL17 are bound by pUL31. Immunogold electron microscopy revealed that pUL31 could associate with multiple sites on a single capsid in the nucleus of infected cells. Electron tomography revealed that immunogold particles specific to pUL31 protein bind to densities at the vertices of the capsid, a location consistent with that of the CVSC. These data suggest that pUL31 loads onto CVSCs in the nucleus to eventually bind pUL34 located within the nuclear membrane to initiate capsid budding.

IMPORTANCE This study is important because it localizes pUL31, a component previously known to be required for HSV capsids to bud through the inner nuclear membrane, to the vertex-specific complex of HSV capsids, which comprises the unique long region 25 (UL25) and UL17 gene products. It also shows this interaction is dependent on the C terminus of UL25. This information is vital for understanding how capsids bud through the inner nuclear membrane.

INTRODUCTION

Like that of all herpesviruses, the icosahedral herpes simplex virus (HSV) capsid contains 12 vertices (1–3). Eleven are identical and comprise 5 copies of the major HSV capsid protein, while the 12th vertex is composed of 12 copies of pUL6 and serves as the portal through which viral DNA is inserted (2, 4–9). The 11 5-fold symmetric structures, designated pentons, are linked to neighboring hexons by triplexes, which are located on the capsid surface and comprise two copies of VP23 and one copy of VP19C (2). Triplexes of the same biochemical composition also link the 150 hexons to one another throughout the capsid (1, 2, 10–12). A complex designated the capsid vertex-specific complex (CVSC) overlies triplexes linking pentons to hexons and is composed of the unique long region 25 (UL25) and UL17 gene products (designated pUL25 and pUL17, respectively) (13–16). The first 27 amino acids of pUL25 are essential for capsid binding (17). pUL17 also augments pUL25 capsid association (18). The atomic structure of a domain composed of the final 446 amino acids (aa) of pUL25 has been solved by X-ray crystallography (19).

Three types of intracellular capsids accumulate in herpesvirus-infected cells, and these capsids differ in their content: C capsids contain viral DNA, B capsids contain cleaved scaffold proteins, and A capsids lack DNA and most internal proteins (20). It is believed that A capsids result from aborted attempts to package viral DNA; thus, the scaffold is expelled, but DNA is not successfully packaged. A capsids accumulate in cells infected with viral mutants lacking functional pUL25, indicating a role for this gene in retention of viral DNA (21).

DNA-containing capsids (C capsids) preferentially bud through the inner nuclear membrane (INM) of infected cells in a process termed primary envelopment (22). pUL31 and pUL34 are required for primary envelopment and comprise the nuclear egress complex (NEC) (23–28). HSV-1 pUL31 is a nuclear phosphoprotein that localizes at the nuclear rim through interaction with the nucleoplasmic N terminus of pUL34, a type II integral membrane protein embedded in the inner nuclear membrane. The composition of the NEC and its function in primary envelopment are conserved in all herpesviruses investigated to date (25, 29–32).

In a previous study, we showed that pUL31 interacts with wild-type (WT) capsids (33). In that study, pUL31 was not detected in association with capsids containing truncated pUL25 lacking the final 476 amino acids. This observation suggested that the interaction between pUL31 in the NEC and the C terminus of pUL25 in the CVSC was responsible for linking the capsid to the inner nuclear membrane. Potentially inconsistent with this hypothesis, however, was the observation that in pseudorabies virus, an alphaherpesvirus of swine, pUL31 was observed in association with capsids lacking the entirety of pUL25 (34). The present studies were undertaken, in part, to address this apparent discrepancy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

CV1 cells were purchased from ATCC and propagated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% newborn calf serum, 100 U/ml of penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. C8-1 cells expressing HSV-1 unique long region 25 (UL25), derived from Vero cells and used for propagating the UL25 null HSV-1, were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) as described above, with the addition of 250 μg/ml of G418 as described previously (21).

The viruses used in this study are listed in Table 1. The herpes simplex virus type 1 F strain (HSV-1[F]), referred to as “wild type” in this study, was from Bernard Roizman (35). Recombinant viruses vFH416 (220S), vFH418 (560S), and vFH421 were derived from the KOS strain of HSV-1 and contain stop codons in UL25 at codons 220 and 560, or deletion of the first 50 codons of UL25, respectively (17, 36). Viruses vJB90, vJB92, and vJB95 were derived from HSV-1(F) strain using an HSV-1(F) bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) and reconstituted in eukaryotic cells as described previously (37, 38). Viruses vJB90, bearing a hemagglutinin (HA) tag insertion between codons A39 and S40 of UL31, vJB92, bearing an HA tag in UL31 and deletion of the codons from amino acids (aa) 6 to 573 of UL25, and vJB95 bearing an HA tag in UL31 and deletion of the codons from aa 561 to 580 of UL25, were generated by En Passant mutagenesis (39). The primers used to construct these mutant viruses were as follows: 5′-TCCTCTGCGGCCGGCGGGACTCTGGGCGTGGTGCGTCGGGCCTACCCATACGACGTCCCAGACTACGCTTCGCGGAAGAGCCTGTAGGGATAACAGGGTAATCGATTT-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAGCTCCTGTTTGCGGGCGTGAGGCGGCAGGCTCTTCCGGGAAGCGTAGTCTGGGACGTCGTATGGGTAGCCAGTGTTACAACCAATTAACC-3′ (reverse) for vJB90, 5′-GTTATTTTCGCTCTCCGCCTCTCGCAGATGGACCCGTACTGCTTCATTCCACAGTACCTGTCGTAGGGATAACAGGGTAATCGATTT-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCCCACCACCCACTGAACCGCCGACAGGTACTGTGGAATGAAGCAGTACGGGTCCATCTGCGAGCCAGTGTTACAACCAATTAACC-3′ (reverse) for vJB92, and 5′-GGCTCCAACACCAAGCGTTTCTCCGCGTTCAACGTTAGCAGCTAGTGGGTGGTGGGCGAGGGGTAGGGATAACAGGGTAATCGATTT-3′ (forward) and 5′-TTTCTCCCTAATGCCCCCTCCCCCCTCGCCCACCACCCACTAGCTGCTAACGTTGAACGCGGAGCCAGTGTTACAACCAATTAACC-3′ (reverse) for vJB95. The HA tag coding sequence is shown in bold. The kanamycin resistance gene sequences are underlined. The resulting BAC DNA was cotransfected with Cre recombinase expression plasmid DNA into either CV1 cells or C8-1 cells, and the reconstituted viruses were further plaque purified. The genotypes of mutant viruses were confirmed by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP), and DNA sequencing of PCR amplicons of the relevant regions (data not shown); the replication properties of these viruses are summarized in Table 1, and the other phenotypes are described in the Results section.

TABLE 1.

Viruses used in this study

| Virusa | Genotypeb: |

Phenotypec | Source or reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UL31 | UL25 | |||

| HSV-1(F) | WT | WT | WT | 35 |

| vFH416 (220S) | WT | Stop at aa 220 | Replicates in C8-1 cells | 17, 36 |

| vFH418 (560S) | WT | Stop at aa 560 | Replicates in C8-1 cells | 17, 36 |

| vFH421 | WT | Deletion of aa 1–50 | Replicates in C8-1 cells | 17, 36 |

| vJB90 | UL31-HA | WT | As WT | This study |

| vJB92 | UL31-HA | Deletion of entire ORF | Replicates in C8-1 cells | This study |

| vJB95 | UL31-HA | Deletion of aa 561–580 | Replicates in C8-1 cells | This study |

vFH416, vFH418, and vFH421 were generated by bacterial artificial chromosome mutagenesis from the HSV-1 KOS strain as described previously (17, 36). vJB90, vJB92, and vJB95 were generated by bacterial artificial chromosome mutagenesis from the HSV-1(F) strain as described in Materials and Methods.

WT, wild type; HA, hemagglutinin; ORF, open reading frame.

C8-1 is a UL25 complementing line as described previously (21).

The HSV-1(F) BAC was obtained from Y. Kawaguchi, University of Tokyo (37), pEP-kan-S, used in the BAC mutagenesis, was obtained from Klaus Osterrieder, University of Berlin, the GS1783 bacterial Escherichia coli host strain was obtained from Greg Smith, Northwestern University, and pCAGGS-nlsCre expressing Cre recombinase in mammalian cells was obtained from Michael Kotlikoff, Cornell University.

Capsid purification.

Capsid purification was carried out as described previously (33). Briefly, CV1 cells (4 × 108) were infected with viruses at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 PFU/cell. The cells were harvested 20 h after infection and lysed in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris [pH 7.6], 500 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT] and protease inhibitor), and the cell lysates were precleared by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The capsids were pelleted by spinning the lysates through a 35% (wt/vol) sucrose cushion at 24,000 rpm for 1 h, resuspended, and banded on a 20 to 50% (wt/vol) sucrose gradient at 24,500 rpm for 1 h. The gradient was fractionated from the bottom to the top of the tube with a Buchler Auto Densiflow IIC fraction collector, the fractions were precipitated with trichloroacetic acid (TCA), and the pellets were resuspended in SDS sample buffer.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting.

CVI cells (8 × 106) were infected with HSV-1(F) or UL25 mutants at an MOI of 10 PFU per cell. At 18 h after infection, the cells were harvested and then lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (20mM Tris [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.25% deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, and protease inhibitor cocktail), and the lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. Rabbit anti-pUL31 polyclonal antibodies (1:80 dilution) or chicken anti-pUL17 antibodies (1:80 dilution) and rabbit anti-chicken IgY (1:100 dilution) were added to the precleared lysates for 2 h followed with addition of Gamma Bind G Sepharose 4B slurry (GE Healthcare) overnight at 4°C with rotation. The Sepharose beads bound to protein were washed four times with excess RIPA buffer, and the bound proteins were eluted into SDS sample buffer.

The detailed procedures for immunoblotting were described previously (33). The primary antibodies were diluted as follows: anti-pUL31 (rabbit), 1:1,000 (23); anti-pUL17 (chicken), 1:2,000 (40); anti-pUL25 (mouse monoclonal antibody [MAb] 4A11 E10; a gift from Fred Homa, University of Pittsburgh), 1:1,000 (17); anti-VP5 (mouse MAb H1.4; Biodesign), 1:1,000; and anti-pUL26/VP22a/VP21 (mouse MAb MCA406; AbD SeroTec), 1:2,000; and anti-HA (HA-probe, sc805, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), 1:200. The horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies were used according to the manufacturers' protocols. Bound antibodies were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, Thermo Scientific) followed by exposure on X-ray film.

Transmission electronic microscopy.

Capsids were purified as described above, and capsid-containing light-scattering bands were collected with Pasteur pipettes. The purified capsids were loaded onto 300 mesh Formvar-coated nickel grids stabilized with evaporated carbon film and incubated with 8- to 10-nm colloidal gold beads conjugated with mouse anti-HA monoclonal antibody (bsm-0966M-Gold; Bioss). The grids were washed extensively, negatively stained, and examined with a transmission electron microscope.

To prepare thin sections for electronic microscopy examination, CV1 cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5 and maintained at 37°C until harvesting at 14 to 18 h postinfection (hpi). Cells were harvested by scraping, pelleted by centrifugation, fixed with 4% formaldehyde and 0.25% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), and incubated first at room temperature for 30 min and then at 4°C for 90 min. Fixed cells were washed three times for 5 min per wash in sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 4°C, dehydrated with increasing ethanol concentrations at 4 and −20°C, and embedded stepwise at −20°C with increasing concentrations of LRWhite (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Fort Washington, PA). The samples were polymerized in gel capsules at 50°C overnight. Sixty-nanometer sections, collected on 300-mesh nickel grids (EMS), were probed with 10-nm-diameter gold anti-HA tag (bsm-0966M 10-nm gold MAb HA tag [12CA5]; Bioss, Woburn, MA) diluted 1:20 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)–Tween 20–1% fish gelatin. After incubation for 3 h at room temperature and five washes in PBS–Tween 20–1% fish gelatin, the sections were counterstained with 2% aqueous uranyl acetate for 20 min and then Reynolds lead citrate for 7 min. Stained grids were viewed with Tecnai 12 Biotwin transmission electron microscope. All images were collected digitally and were processed using Adobe Photoshop software for illustrative purposes.

Electron tomography.

Purified B capsids were loaded onto 300-mesh Formvar-coated copper grids stabilized with evaporated carbon film. The grids were incubated with 8- to 10-nm colloidal gold beads conjugated with mouse anti-HA monoclonal antibody, extensively washed, and negatively stained as described above. The grids were loaded onto a Gatan 626 specimen holder for electron tomography data collection. We used an FEI TF20 transmission electron microscope to record electron tomographic tilt series. The instrument was operated at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV, and images were recorded at a nominal magnification of 29,000× with an underfocus value of 4.00 μm. Tilt series were acquired with FEI's batch tomography on a 16-megapixel TVIPS charge-coupled device (CCD) camera with a binning factor of 2, giving a final pixel size of 0.77 nm. The tilt angles ranged from −70° to +70°, with an interval angle of 1°.

We used Etomo of IMOD (41) for alignment of the frames in each tilt series and for three-dimensional (3D) tomographic reconstruction. Key steps include X-ray removal, fiducial model fixation, boundary creations using the Slicer window, patching tracking for alignment, and back projection for 3D reconstruction. The processed slices were viewed and analyzed with the 3dmod, and Slicer modules of IMOD. Commercial software Amira was used to segment capsids with attached gold-conjugated antibodies for 3D visualization and color rendering.

RESULTS

Previous studies showed that pUL31 did not associate with capsids purified from cells infected with a virus bearing a stop codon at UL25 position 104, indicating that capsid association of pUL31 required the final 476 amino acids (aa) of pUL25 (33). To more precisely map regions of pUL25 required for the association of pUL31 with the capsid, we analyzed viruses lacking the entire UL25 open reading frame (ORF), as well as viruses bearing stop codons at positions 212 and 560.

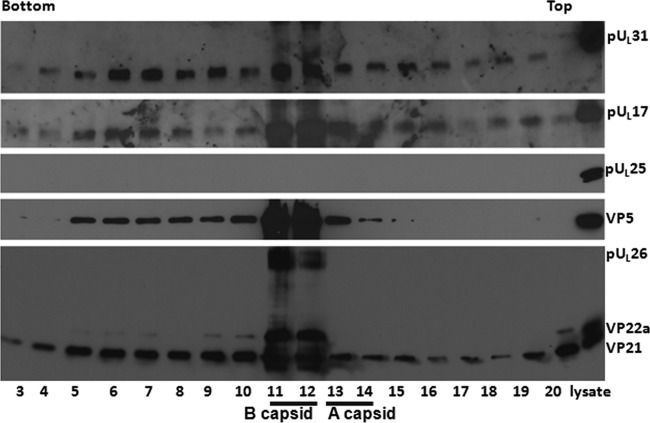

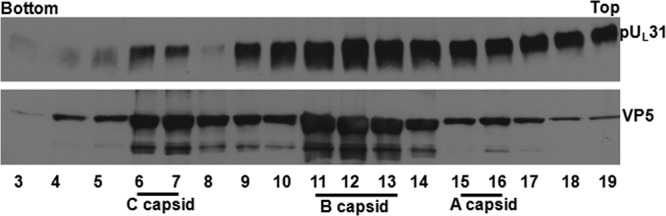

As a control, capsids were collected from cells infected with wild-type virus HSV-1(F). The capsids were separated by centrifugation on continuous sucrose gradients as detailed in Materials and Methods. Fractions of 0.5 ml were collected, and protein within them was precipitated with TCA, solubilized in SDS, and electrophoretically separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels. After transfer to nitrocellulose membranes, the proteins were probed with antibodies against pUL31. The fractions were also probed with antibodies to the major capsid protein VP5 to identify fractions that contained capsids. The results (Fig. 1 reiterate those already published (33) and show that UL31 immunoreactivity partially overlapped that of VP5 within the gradient. Specifically, pUL31 immunoreactivity was detected in fractions 4 to 19, with the highest concentrations in fractions 6 and 7 and 9 to 14. Significant amounts of immunoreactivity were also present in fractions 15 to 19. Fractions 6 and 7 and 11 to 14 also contained substantial VP5 immunoreactivity, indicating peaks attributable to C and B capsids, respectively.

FIG 1.

Immunoblotting of capsids purified from cells infected with HSV-1(F). Capsids of HSV-1 were purified from infected CV1 cells as described in Materials and Methods. The capsid-containing sucrose gradient was fractionated, and the proteins in each fraction were precipitated with TCA and dissolved in SDS loading buffer. Fractions 3 to 19 from the bottom to the top of the gradient were separated on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel (SDS-PAGE), followed by immunoblotting with antibodies to pUL31 and VP5 sequentially, and the results were revealed by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL).

In the next series of experiments, capsids were purified from cells infected with mutant viruses encoding absence or truncation of pUL25 or lacking pUL17. The genotypes of these recombinant viruses, as well as others used in this study, are summarized in Table 1.

The sucrose gradients bearing the capsids were fractionated, and the proteins were precipitated with TCA and probed on immunoblots with antibodies directed against pUL31, pUL17, pUL25, VP5, and the major scaffold protein VP22a.

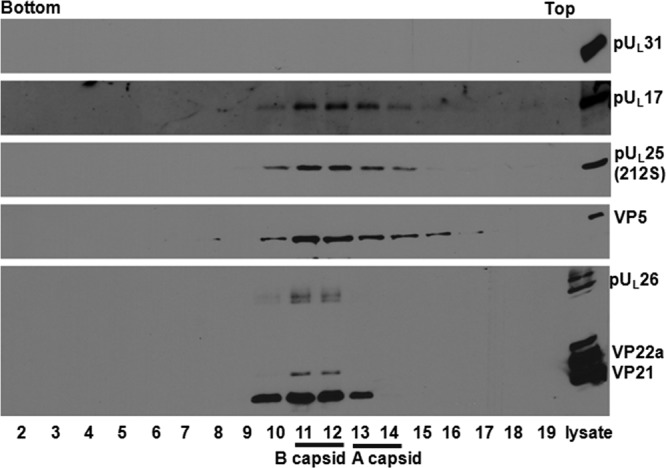

Figure 2 shows an immunoblot of purified fractionated capsids from cells infected with the virus bearing a stop codon at UL25 position 212. The rightmost lane contains unfractionated lysate from infected cells as a control for the immunoblotting reaction. Fractions 10 to 16 contained VP5-specific immunoreactivity, indicating the presence of capsids within these fractions. As expected, fractions 10 to 15 also contained pUL17 and pUL25 immunoreactivity, since these proteins are capsid components. The absence of pUL17 and pUL25 immunoreactivity in fraction 16 may reflect the presence of fewer capsids in this fraction. Fractions 10 to 13 contained immunoreactivity specific for scaffold proteins, suggesting that these particular fractions contained a prominent number of B capsids. Despite the presence of capsids within fractions 10 to 16, none of these fractions contained pUL31-specific immunoreactivity. This absence was not a consequence of poor reactivity with the pUL31 antibody inasmuch as this antibody readily detected pUL31 within the lane containing the unfractionated cellular lysate. We conclude that pUL25 amino acids C terminal to position 212 were essential for pUL31 association with capsids.

FIG 2.

Immunoblotting of 212 S capsids. About 4 × 108 CV1 cells were infected with 212 S virus (with pUL25 truncated at codon 212) at an MOI of 5 PFU per cell. Nuclear capsids were purified as described in Materials and Methods. The capsids were separated through a continuous sucrose gradient, 0.5-ml fractions were collected with a fractionator, and proteins were precipitated with TCA and dissolved in SDS loading buffer. The samples were separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel, with lanes from left to right corresponding to fractions collected from the bottom to top of the gradient. The far-right lane contains unfractionated lysates from infected cells. Immunoblotting was performed with antibodies to pUL31, pUL17, pUL25, VP5, and scaffold proteins VP22a and VP21, respectively, and the results were revealed by ECL.

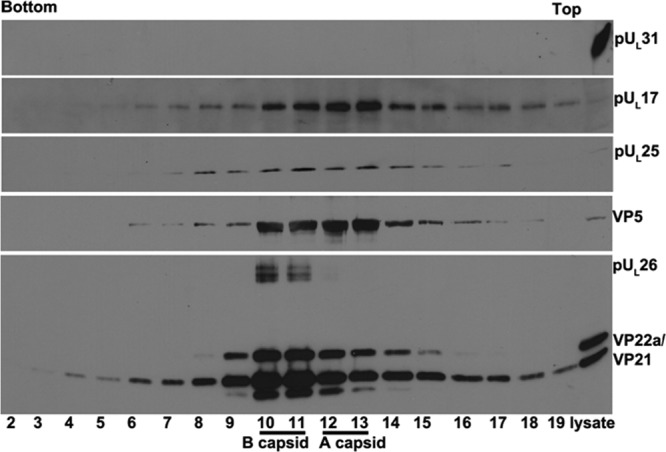

Figure 3 illustrates a similar experiment to those in previous figures, except that capsids were purified from cells infected with a virus bearing a stop codon in place of UL25 codon 560. VP5- and pUL25-specific immunoreactivity was detectable in fractions 8 to 16, although fractions 10 to 13 contained significantly more VP5 immunoreactivity than the other fractions. pUL17 immunoreactivity was detected in fractions 7 to 19, but it was also most concentrated in fractions 10 to 13. The scaffold protein VP21 was present in most fractions, but it was most concentrated in fractions 10 to 13. The scaffold protein VP22a was only detectable in fractions 9 to 15, indicating the presence of numerous B capsids within these fractions. In contrast to these results, pUL31 was not detected in any fraction derived from the sucrose gradient. Ample immunoreactivity was detected in the cellular lysate, however. These data indicate that the final 20 amino acids of pUL25 were required for association of pUL31 with capsids.

FIG 3.

Immunoblotting of 560S capsids. CV1 cells were infected with HSV-1 recombinant virus vFH418 (with pUL25 truncated at codon 560), and capsids were purified as described in Materials and Methods. The continuous sucrose gradient containing capsids was fractionated from bottom to top, and the protein in each fraction was precipitated with TCA and dissolved in SDS loading buffer. Denatured proteins in fractions 2 to 19 and from a sample of virus-infected lysates (far right lane) were separated on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, transferred to nitrocellulose, and then probed with antibodies to pUL31, pUL17, pUL25, VP5, or scaffold proteins VP22a and VP21. Bound antibodies were revealed using ECL.

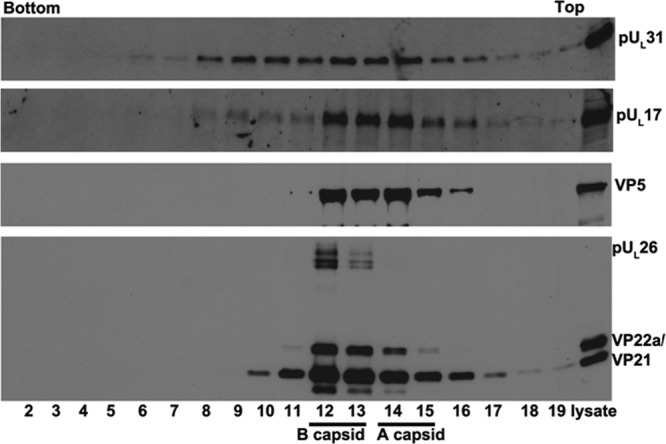

Figure 4 illustrates a similar experiment to those shown in Fig. 1 to 3, except that capsids were purified from cells infected with a virus lacking the entire UL25 open reading frame. Like mutant viruses with pUL25 C-terminus truncations, two light-scattering bands were observed in the sucrose gradient containing lysates of cells infected with the UL25 null virus, suggesting B and A capsids were produced by this virus. As in previous experiments, capsids were most concentrated near the middle of the sucrose gradient and specifically within fractions 12 to 16 of this particular gradient (Fig. 4), as revealed by VP5 immunoreactivity. pUL17 was also most concentrated in these fractions, although some immunoreactivity was also detected in fractions 8 to 11. The VP22a scaffold protein was most concentrated in fractions 12 to 14, indicating the presence of at least some B capsids within these fractions. The absence of VP22a from fractions 15 and 16 suggests that the VP5 immunoreactivity in these fractions was a consequence of a large number of A capsids within them. This was consistent with previous reports of the UL25 truncation mutant, which produces an abnormally high number of A capsids (21). Surprisingly, and in contrast to the results in Fig. 2 and 3, pUL31 immunoreactivity was readily detected in fractions 8 to 16 of the sucrose gradient. These data indicate that in the complete absence of pUL25, pUL31 can still associate with capsids.

FIG 4.

Immunoblotting of capsids of UL25 null mutant. Capsids of HSV-1 mutant virus vJB92 (lacking the entire UL25 ORF) were purified from infected CV1 cells on a continuous sucrose gradient as described in Materials and Methods. Proteins in each fraction were precipitated with TCA and dissolved in SDS loading buffer. Fractions 2 to 19 were collected from the bottom to the top of the gradient. Proteins within these fractions and the unfractionated lysate (far-right lane) were separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel, followed by immunoblotting with antibodies to pUL31, pUL17, VP5, or viral scaffold proteins VP22a and VP21, respectively. Bound antibodies were revealed by ECL.

Previous reports demonstrated that capsid association of pUL25 was dependent on the first 50 amino acids (aa) of this protein, as revealed by study of recombinant virus vFH421, which lacks the first 50 aa of pUL25. Figure 5 shows immunoreactivity of pUL17, pUL25, VP5, and scaffold proteins in fractions from a sucrose gradient containing capsids purified from cells infected with vFH421. This virus, like all lethal UL25 mutants, fails to stably package DNA, producing only A and B capsids (36). VP5 and the scaffold proteins VP22a, VP21, and pUL26 were most concentrated in fractions 11 and 12, with smaller amounts of VP5 in fractions 5 to 10, 13, and 14 and smaller amounts of VP21 in all fractions. We deduce from the presence of V22a that fractions 11 and 12 contained B capsids. Because fraction 13 contained substantial VP5 immunoreactivity, but no Vp22a, we conclude that this fraction contained a substantial number of A capsids. pUL17 immunoreactivity was most concentrated in capsid-containing fractions 11 to 13, with less in other fractions. Not surprisingly, pUL25 was not detected in any gradient fraction, confirming the conclusion that association of pUL25 with capsids is dependent on its first 50 aa. Surprisingly, and consistent with the results obtained from analysis of the UL25 null virus, pUL31 was most concentrated in vFH421 capsid-containing fractions, with less in other fractions. We conclude that under conditions in which pUL25 cannot associate with capsids, pUL31 can still associate. In contrast, C-terminal truncation of capsid-bound pUL25 by as little as 20 amino acids precludes pUL31 from binding capsids.

FIG 5.

Immunoblotting of capsids from cells infected with a mutant lacking the first 50 amino acids of pUL25. Capsids of HSV-1 mutant virus vFH421 (lacking the codons from aa 1 to 50 of pUL25) were purified from infected CV1 cells by continuous sucrose gradient fractionation as described in Materials and Methods. The proteins in each fraction were precipitated with TCA and dissolved in SDS loading buffer. Fractions 3 to 20 collected from the bottom to the top of the gradient and a sample of unfractionated lysate (far right lane) were separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel, and the presence of proteins was determined by immunoblotting using antibodies to pUL31, pUL25, pUL17, VP5, or viral scaffold proteins VP22a and VP21.

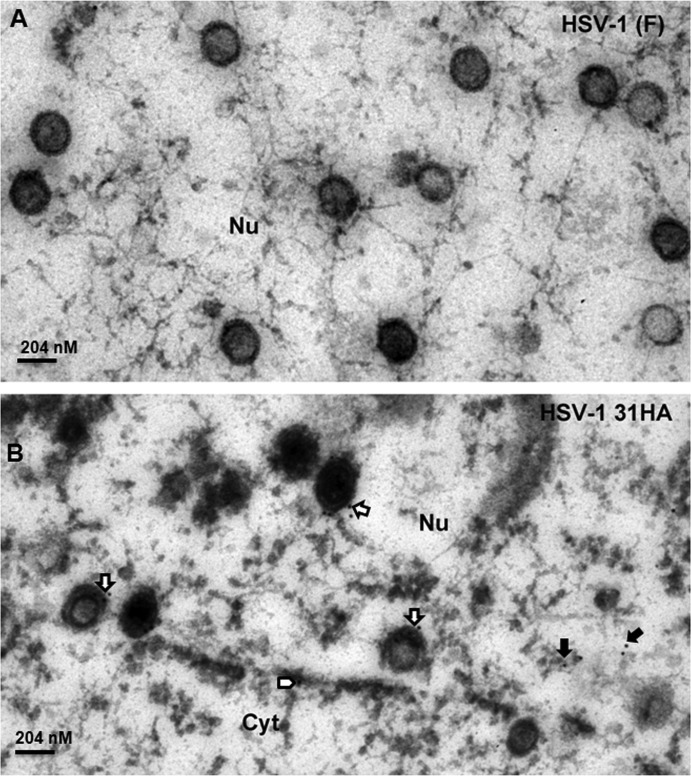

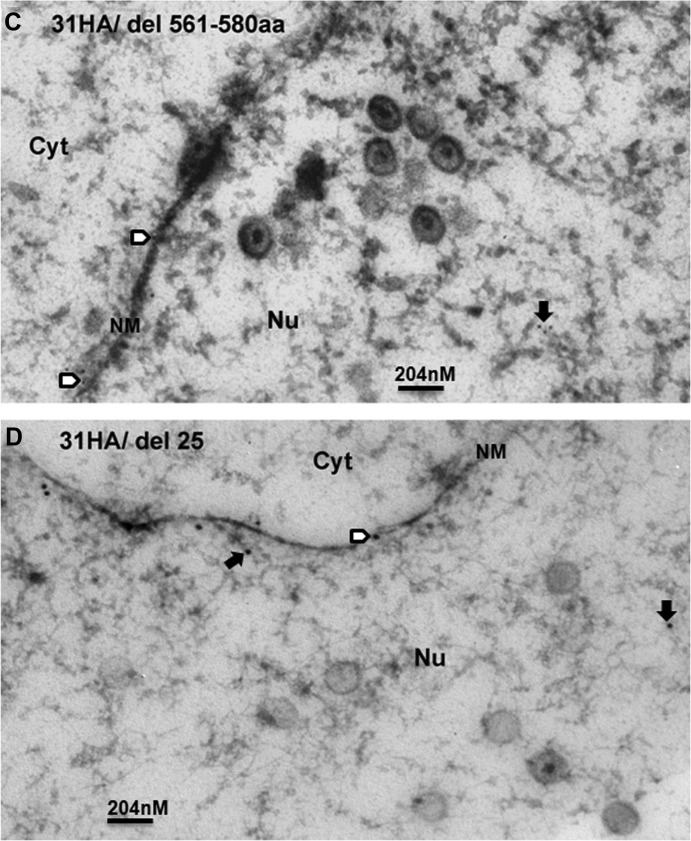

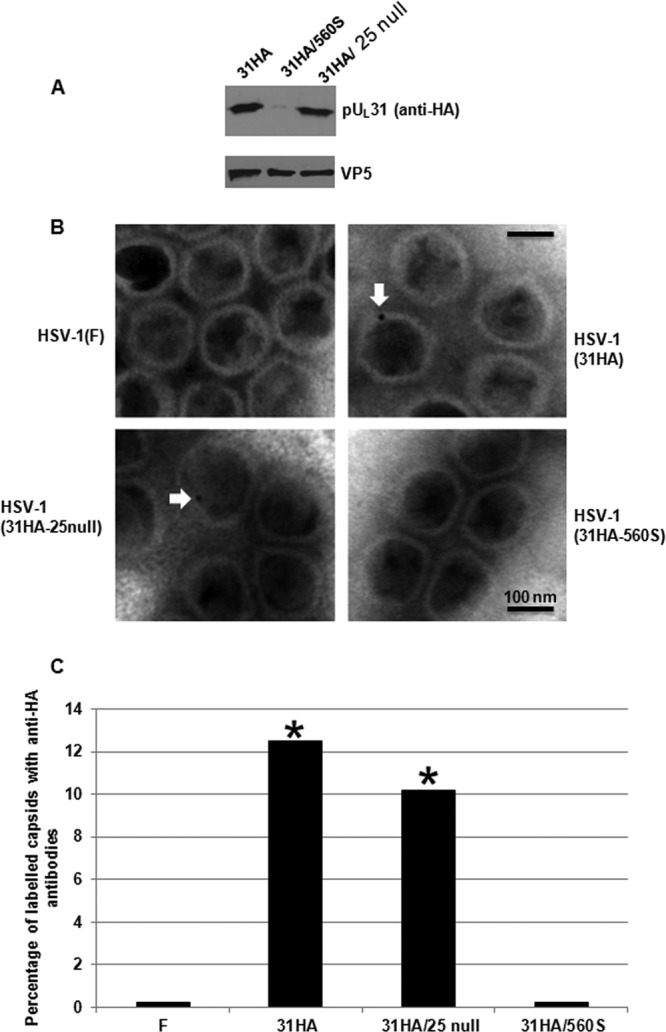

To confirm the pUL31 capsid association, we generated new recombinant viruses in which DNA encoding an influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) tag was inserted between pUL31 codons 39 and 40. Additional viruses were constructed that encoded the same HA-tagged pUL31, but encoded (i) a stop codon at codon 560 of UL25 or (ii) a complete removal of the UL25 open reading frame. Cells were infected with these recombinant viruses or wild-type virus, fixed at 18 h after infection in Epon, and thin sections were reacted with the HA antibody. The results are shown in Fig. 6B, C, and D. As a negative control, cells infected with HSV-1(F) were not labeled significantly at the nuclear rim or nucleoplasm (Fig. 6A). Importantly, some intranuclear capsids of cells infected with UL31-HA-encoding virus were labeled with gold beads (Fig. 6B, open arrows), indicating that the pUL31 associated with these capsids. Some capsids were labeled with more than 1 gold bead, suggesting multiple copies of pUL31 were present at multiple sites on a single capsid. In contrast, capsids of cells infected with viruses bearing UL31-HA and UL25 truncated at codon 560 were not labeled significantly above that observed in HSV-1(F) capsids (Fig. 6C and A, respectively.) To our surprise, anti-HA antibodies did not label capsids in cells infected with viruses bearing UL31-HA and lacking the entire UL25 ORF (Fig. 6D), although pUL31 was detected in association with capsids purified from cells infected with the UL25 null virus (Fig. 4 and Fig. 7A). We conclude that pUL31 can associate with intranuclear capsids in the nucleoplasm. Moreover, both C-terminal truncation and removal of pUL25 precluded association of pUL31 immunoreactivity with capsids observed in situ. The latter observation was in contrast to observations obtained from immunoblot analysis of pUL25 null capsids.

FIG 6.

Immunogold analysis of pUL31 localization in infected cells. (A) HSV-1(F). (B) HSV-1 UL31-HA. (C) HSV-1 UL31-HA with deletion of aa 561 to 580. (D) HSV-1 UL31-HA with UL25 ORF deleted. Cells were infected with the indicated viruses at 5 PFU per cell. At 18 h after infection, the cells were fixed and embedded. Thin sections were reacted with HA-specific antibody to localize pUL31. Bound antibody was revealed by goat anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to 10-nm-diameter gold beads. Sections were examined by transmission electron microscopy. Open arrows indicate the capsids labeled with gold beads, solid arrows indicate free gold beads in nuclear (Nu) plasma, and open arrowheads indicate gold beads in nuclear membrane (NM). Cyt, cytoplasm. The size standard bar is 204 nm, and capsids are approximately 125 nm in diameter.

FIG 7.

pUL31 association with purified B capsids. (A) Immunoblotting of purified B capsids with anti-HA antibody and anti-VP5 antibody. (B) Examples of immunogold labeling of B capsids with 10-nm-diameter gold-conjugated anti-HA antibody. (C) More than 1,000 capsids of each type were scored as labeled or unlabeled. The histogram indicates the percentage of labeled capsids under each circumstance. GraphPad software was using for statistical analyses using Fisher's exact test. *, P < 0.01.

To further ensure that pUL31 associated with capsids, capsids were purified from cells infected with these viruses, and the capsids within light-scattering bands were collected with a Pasteur pipette. B capsids were denatured in SDS, separated on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel, transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed with antibodies against HA and as a loading control, VP5. As shown in Fig. 7A, pUL31-HA was readily detected in capsids of pUL31-HA-tagged virus and the virus bearing pUL31-HA, but lacking the entire UL25 open reading frame. In contrast, very little HA immunoreactivity was associated with capsids from cells infected with the virus encoding tagged UL31 and UL25 truncated at codon 560. Taken together, the data were consistent with the results using the UL31 polyclonal antibody and indicated that pUL31 binds capsids lacking pUL25 (Fig. 4 and 5) but does not associate with capsids bearing UL25 that lacks the final 20 amino acids (Fig. 3).

Purified capsids were also attached to coated grids. Anti-HA mouse monoclonal antibody conjugated with 10-nm-diameter gold beads was reacted with the attached capsids, and after extensive washing, labeled capsids were observed by transmission electron microscopy. After counting at least 1,000 capsids of each type, the percentage of labeled capsids was calculated. As shown in Fig. 7B and C, pUL31-HA was detected in more than 12% of capsids bearing full-length pUL25 and pUL31-HA. Approximately 10% of capsids lacking the entire pUL25 were labeled with the HA antibody. In contrast, fewer than 0.5% of wild-type capsids were labeled; a similar low percentage of capsids purified from cells infected with the virus encoding pUL31-HA and lacking the final 20 amino acids of pUL25 was labeled with HA antibody. These data were consistent with the other experiments shown herein and indicate that while the final 20 amino acids of pUL25 are required for pUL31 to associate with capsids, pUL31 can associate with capsids lacking pUL25. We speculate that pUL25 masks other regions of the capsid with which pUL31 can associate. However, in cases in which pUL25 associates with capsids, the final 20 amino acids of this protein are required for pUL31 association.

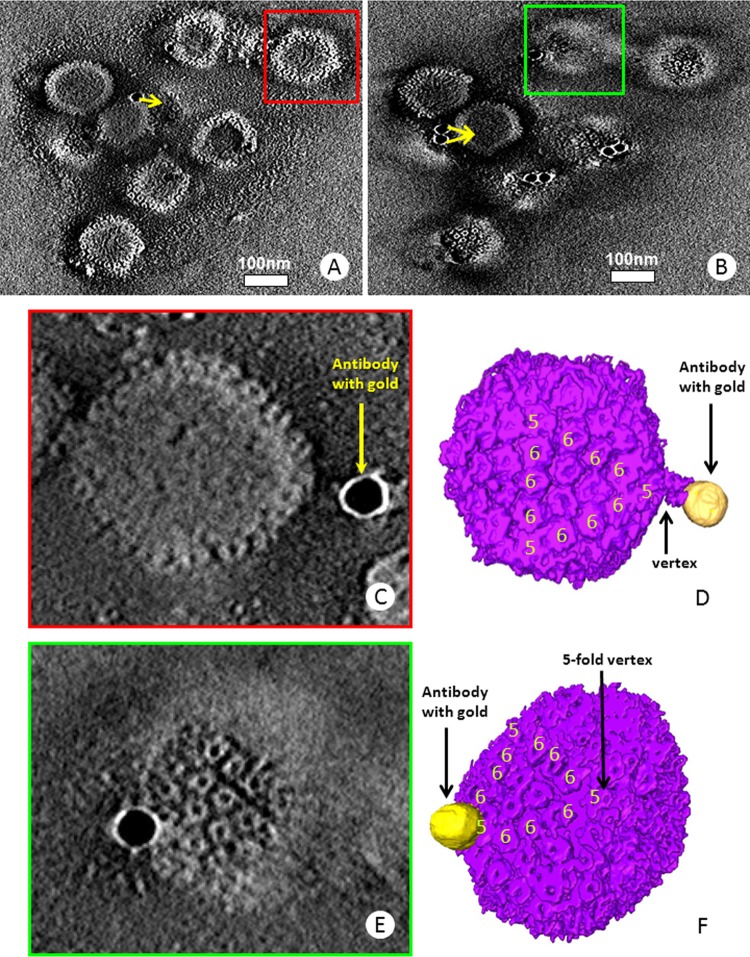

To determine the exact region of the capsid with which pUL31 associated, we subjected the capsids labeled with anti-HA antibodies to electron tomography and obtained three-dimensional electron tomograms from a total of 10 sets of tilt series. These 10 data sets all reveal the specific locations of gold-conjugated antibodies bound to capsids, as exemplified by those shown in Fig. 8 and Movie S1 in the supplemental material. Most of the capsids in the tomogram have one or two gold particles bound per capsid. Pentons and hexons characteristic of herpesvirus capsids can be readily identified in the slices of the electron tomogram (Fig. 8). Two different capsids with two different beads were segmented out for 3D visualization (Fig. 8C to F). In one case, the bead was superimposed directly on the capsid near a penton. In the other example, the bead was located at a distance from the pentonic vertex but was linked to that vertex by a tubular density that is consistent in length with the heavy and light chains of the immunoglobulin conjugate. Although the resolution is somewhat limiting, the location at pentonic vertices is consistent with the position of the CVSC that links pentons to hexons and comprises at least pUL25 and pUL17.

FIG 8.

Electron tomography of pUL31 association with purified capsids. (A and B) Two density slices from 1 of the 10 electron tomograms of immunogold-labeled B capsids. The arrows point to the capsid the gold particles are bound to. The full tomogram is shown in Movie S1 in the supplemental material. (C and D) Density slice (C) and colored surface view (D) of the capsid in the red box in panel A. Segments of the capsid are shown with the attachment of the gold particle (antibody) on the pentonic vertex of the capsid. (E and F) Density slice (E) and colored surface view (F) of the capsid in the green box in panel B. In panel C or E, only the slice revealing the attachment site along with the density in between the gold particle and the capsid is shown. In panel D or F, pentons are labeled with the number 5 and hexons with the number 6.

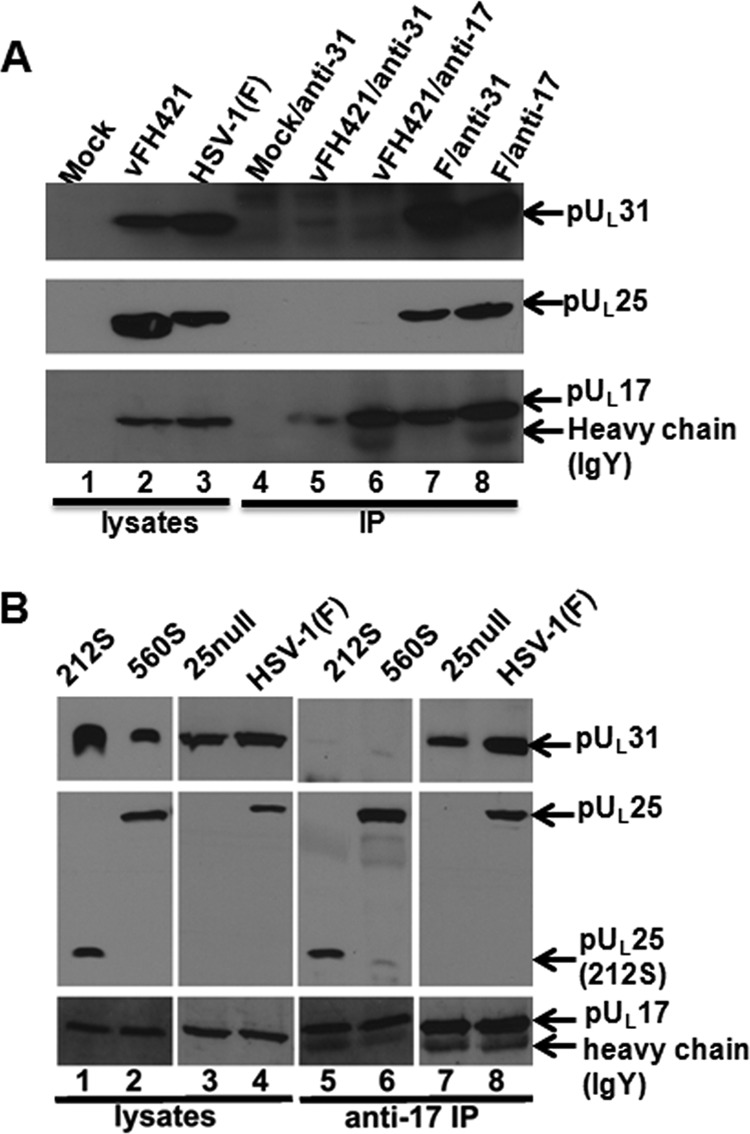

We previously showed that pUL25 and pUL17, the two components of the CVSC, coimmunoprecipitated with pUL31. These immunoprecipitated complexes could be derived from capsid-free proteins or disruption of capsids. We took advantage of the vFH421 virus to determine whether capsid-free pUL25 (albeit lacking the first 50 amino acids) could interact with pUL31. Lysates of cells infected with vFH421 or wild-type virus were subjected to immunoprecipitation with the pUL31- or pUL17-specific antibodies. As shown in Fig. 9A, and as we have shown in previous studies, the three proteins were efficiently coimmunoprecipitated from HSV-1(F) lysates with either antibody. In contrast, while pUL17 antibody immunoprecipitated pUL17 from vFH421-infected cell lysates robustly, no pUL25 and minimal amounts of pUL31 were coimmunoprecipitated. Results of the pUL31 immunoprecipitation from vFH421-infected cell lysates were puzzling inasmuch as pUL31 did not immunoprecipitate well with pUL31-specific antibody, despite the fact that this immunoprecipitation was robust from HSV-1(F)-infected cell lysates. This result aside, we conclude that pUL31 association with pUL25 requires its first 50 amino acids. In the absence of these residues, pUL31 associates with pUL17, albeit weakly.

FIG 9.

Coimmunoprecipitation of pUL17, pUL25, and pUL31 in cells infected with wild-type and UL25 mutant viruses. CV1 cells were infected with HSV-1(F) or the UL25 mutants indicated above the panel. At 18 h postinfection, the cells were lysed and reacted with anti-pUL17 or anti-pUL31 antibodies. Antigen-antibody complexes were purified and electrophoretically separated on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel. (A) Viruses used for infection are indicated at the top of each lane. The first 3 lanes contain cellular lysates only. Lanes 4 to 8 contain immunoprecipitation reactions. Labels above each lane indicate the virus used for infection, followed by a forward slash and the antibody used for immunoprecipitation. To the right are the antigens recognized by immunoblotting. (B) The cell lysates (lanes 1 to 4) and materials immunoprecipitated with pUL17-specific antibody (lanes 5 to 8) were transferred to nitrocellulose and subsequently probed with the antibodies indicated to the right. Bound antibodies were visualized using appropriate conjugates and ECL chemistry.

To determine whether the final 20 amino acids of pUL25 were required for coimmunoprecipitation with pUL31, we infected cells with wild-type virus or viruses bearing stop codons at position 212 or 560 of UL25. Lysates of the infected cells were then subjected to immunoprecipitation with ant-pUL17 antibody, followed by immunoblotting with antibodies against pUL25, pUL17, and pUL31. The results, shown in Fig. 9B, indicated that anti-pUL17 antibody immunoprecipitated pUL17 and coimmunoprecipitated pUL31 and pUL25 from lysates of wild-type virus-infected cells, as shown previously. While the pUL17-specific antibody coimmunoprecipitated truncated pUL25 from lysates of cells infected with the two viruses bearing stop codons in different positions of pUL25, pUL31 did not coimmunoprecipitate with these truncated UL25 proteins. This was the case despite the presence of readily detectable pUL31 in the lysates of cells infected with the UL25 truncation mutants. These data indicate that the C terminus of pUL25 is necessary for pUL31 to interact with the pUL17/pUL25 complex. Interestingly, pUL31 was coimmunoprecipitated by the pUL17 antibody in the complete absence of pUL25 (i.e., from lysates of cells infected with the UL25 null mutant). The interaction with pUL17 might help explain how pUL31 can associate with capsids in the absence of pUL25.

DISCUSSION

The data in this report verify that pUL31 is a minor component of capsids and identify regions of pUL25 necessary for pUL31 to associate with the capsid. The data also indicate that the UL31 protein localizes on the external surface of capsids on or near pentonic vertices. This position is consistent with those of pUL25 and pUL17, which comprise the CVSC (14, 15). Higher-resolution studies will be required to further refine the site on the capsid with which pUL31 associates.

The data are consistent with reports using pseudorabies virus, a herpesvirus of swine, in which it was shown that pUL31 can associate with pUL25 null capsids (34). In the present report, pUL31 also associated with purified HSV-1 UL25 null capsids; however, C-terminal truncation of pUL25 by as little as 20 amino acids precluded capsid association of pUL31. These results suggest that pUL31 normally requires the C terminus of pUL25 to associate with capsids, but in the complete absence of pUL25, pUL31 can still associate. We show that pUL17, the other component of the CVSC, coimmunoprecipitates with pUL31 in the complete absence of pUL25. This interaction might explain how pUL31 can associate with pUL25 null capsids, inasmuch as these contain some pUL17. Together, these data suggest that while pUL31 can associate with both components of the CVSC, pUL25 is the most important contributor to pUL31 binding under normal circumstances. We hypothesize that when pUL25 binds capsids, it masks the pUL31 association regions on pUL17. Thus, in the complete absence of pUL25 from the capsid, pUL31 can still bind. However, when pUL25 does associate with the capsid, as is normally the case, its last 20 amino acids are essential for pUL31 to associate with capsids. It should be noted that immunogold labeling of cells infected with a virus lacking the entire UL25 open reading frame and containing an epitopically tagged UL31 protein demonstrated that pUL31 did not associate efficiently with intranuclear pUL25 null capsids (Fig. 6D), but pUL31 was detected from purified capsids (Fig. 4 and 7A). Thus, association of pUL31 with pUL17 in UL25 null capsids may occur more readily after lysis of the cell, rather than within the intact nucleus.

We and others have hypothesized in previous studies that pUL25 enrichment in C capsids allows binding of pUL31, which in turn targets them to the NEC, culminating in budding from the nucleus (15, 33). The hypothesis is appealing to us because it suggests that the virus conserves resources by reserving most budding reactions for capsids containing DNA. Consistent with this idea, precluding pUL25 association with capsids by removing its first 50 amino acids precludes pUL31 binding to pUL25. However, pUL31 still associates with these capsids and UL25 null capsids, probably through weak interactions with pUL17. While we speculate that these observations may result from off-pathway effects, because in situ immunogold analysis suggests only poor association of pUL31 with capsids in the absence of pUL25 (Fig. 6D), the result is potentially confounding to our model.

Based on the intensity of immunolabeling of purified capsids, we suspect that there is relatively low occupancy of pUL31 on or near capsid pentonic vertices, compared to occupancy of CVSC components. It is also possible that the association of pUL31 with capsids is relatively weak, and some pUL31 is lost during capsid purification. Although there is no direct evidence to support this idea, a weak pUL31-CVSC interaction might be advantageous to virus replication because pUL31 and pUL34 must disassociate from the capsid before capsids are released into the cytosol, while the pUL31/pUL34 complex remains associated with the outer nuclear membrane. Previous evidence suggests that this de-envelopment reaction is regulated by phosphorylation of pUL31 and glycoprotein B by the viral kinase encoded by unique short region 3 (US3) (42, 43). We should also note that pUL31 plays an important role in optimizing gene expression, a function that could contribute to observed defects in accumulation of viral DNA, cleavage of viral DNA, or other aspects of viral replication (44, 45). Whether the capsid association of pUL31 reported here and the other roles of pUL31 reported previously are interrelated or contribute to primary envelopment requires further investigation.

In summary, we have shown that pUL31 associates with the vertices of intranuclear capsids and that the last 20 amino acids of pUL25 are required for this association. It will be of interest to determine whether this region of pUL25 is sufficient to mediate capsid binding or could act to block nucleocapsid envelopment in infected cells.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

These studies were supported by NIH grants AI52341 to J.D.B. and AI069015 to Z.H.Z.

We thank Fred Homa for recombinant viruses and helpful discussions and Ivo Atanasov for assistance in electron tomography.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 22 January 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.03175-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhou ZH, Dougherty M, Jakana J, He J, Rixon FJ, Chiu W. 2000. Seeing the herpesvirus capsid at 8.5 A. Science 288:877–880. 10.1126/science.288.5467.877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newcomb WW, Trus BL, Booy FP, Steven AC, Wall JS, Brown SC. 1993. Structure of the herpes simplex virus capsid molecular composition of the pentons and the triplexes. J. Mol. Biol. 232:499–511. 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trus BL, Homa FL, Booy FP, Newcomb WW, Thomsen DR, Cheng N, Brown JC, Steven AC. 1995. Herpes simplex virus capsids assembled in insect cells infected with recombinant baculoviruses: structural authenticity and localization of VP26. J. Virol. 69:7362–7366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trus BL, Newcomb WW, Booy FP, Brown JC, Steven AC. 1992. Distinct monoclonal antibodies separately label the hexons or the pentons of herpes simplex virus capsid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89:11508–11512. 10.1073/pnas.89.23.11508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rochat RH, Liu X, Murata K, Nagayama K, Rixon FJ, Chiu W. 2011. Seeing the portal in herpes simplex virus type 1 B capsids. J. Virol. 85:1871–1874. 10.1128/JVI.01663-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cardone G, Winkler DC, Trus BL, Cheng N, Heuser JE, Newcomb WW, Brown JC, Steven AC. 2007. Visualization of the herpes simplex virus portal in situ by cryo-electron tomography. Virology 361:426–434. 10.1016/j.virol.2006.10.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang JT, Schmid MF, Rixon FJ, Chiu W. 2007. Electron cryotomography reveals the portal in the herpesvirus capsid. J. Virol. 81:2065–2068. 10.1128/JVI.02053-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trus BL, Cheng N, Newcomb WW, Homa FL, Brown JC, Steven AC. 2004. Structure and polymorphism of the UL6 portal protein of herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol. 78:12668–12671. 10.1128/JVI.78.22.12668-12671.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newcomb WW, Juhas RM, Thomsen DR, Homa FL, Burch AD, Weller SK, Brown JC. 2001. The UL6 gene product forms the portal for entry of DNA into the herpes simplex virus capsid. J. Virol. 75:10923–10932. 10.1128/JVI.75.22.10923-10932.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trus BL, Booy FP, Newcomb WW, Brown JC, Homa FL, Thomsen DR, Steven AC. 1996. The herpes simplex virus procapsid: structure, conformational changes upon maturation, and roles of the triplex proteins VP19C and VP23 in assembly. J. Mol. Biol. 263:447–462. 10.1016/S0022-2836(96)80018-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spencer JV, Newcomb WW, Thomsen DR, Homa FL, Brown JC. 1998. Assembly of the herpes simplex virus capsids: preformed triplexes bind to the nascent capsid. J. Virol. 72:3944–3951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou ZH, Prasad BV, Jakana J, Rixon FJ, Chiu W. 1994. Protein subunit structures in herpes simplex virus A-capsid determined from 400 kV spot-scan electron cryomicroscopy. J. Mol. Biol. 242:456–469. 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toropova K, Huffman JB, Homa FL, Conway JF. 2011. The herpes simplex virus 1 UL17 protein is the second constituent of the capsid vertex-specific component required for DNA packaging and retention. J. Virol. 85:7513–7522. 10.1128/JVI.00837-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conway JF, Cockrell SK, Copeland AM, Newcomb WW, Brown JC, Homa FL. 2010. Labeling and localization of the herpes simplex virus capsid protein UL25 and its interaction with the two triplexes closest to the penton. J. Mol. Biol. 397:575–586. 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.01.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trus BL, Newcomb WW, Cheng N, Cardone G, Marekov L, Homa FL, Brown JC, Steven AC. 2007. Allosteric signaling and a nuclear exit strategy: binding of UL25/UL17 heterodimers to DNA-filled HSV-1 capsids. Mol. Cell 26:479–489. 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newcomb WW, Homa FL, Brown JC. 2006. Herpes simplex virus capsid structure: DNA packaging protein UL25 is located on the external surface of the capsid near the vertices. J. Virol. 80:6286–6294. 10.1128/JVI.02648-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cockrell SK, Huffman JB, Toropova K, Conway JF, Homa FL. 2011. Residues of the UL25 protein of herpes simplex virus that are required for its stable interaction with capsids. J. Virol. 85:4875–4887. 10.1128/JVI.00242-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thurlow JK, Murphy M, Stow ND, Preston VG. 2006. Herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA-packaging protein UL17 is required for efficient binding of UL25 to capsids. J. Virol. 80:2118–2126. 10.1128/JVI.80.5.2118-2126.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowman BR, Welschhans RL, Jayaram H, Stow ND, Preston VG, Quiocho FA. 2006. Structural characterization of the UL25 DNA-packaging protein from herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol. 80:2309–2317. 10.1128/JVI.80.5.2309-2317.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gibson W, Roizman B. 1972. Proteins specified by herpes simplex virus. VIII. Characterization and composition of multiple capsid forms of subtypes 1 and 2. J. Virol. 10:1044–1052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McNab AR, Desai P, Person S, Roof LL, Thomsen DR, Newcomb WW, Brown JC, Homa FL. 1998. The product of the herpes simplex virus type 1 UL25 gene is required for encapsidation but not for cleavage of replicated DNA. J. Virol. 72:1060–1070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roizman B, Furlong D. 1974. The replication of herpesviruses, p 229–403 In Fraenkel-Conrat H, Wagner RR. (ed), Comprehensive virology, 3rd ed. Plenum Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reynolds AE, Ryckman B, Baines JD, Zhou Y, Liang L, Roller RJ. 2001. UL31 and UL34 proteins of herpes simplex virus type 1 form a complex that accumulates at the nuclear rim and is required for envelopment of nucleocapsids. J. Virol. 75:8803–8817. 10.1128/JVI.75.18.8803-8817.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reynolds AE, Wills EG, Roller RJ, Ryckman BJ, Baines JD. 2002. Ultrastructural localization of the herpes simplex virus type 1 UL31, UL34, and US3 proteins suggests specific roles in primary envelopment and egress of nucleocapsids. J. Virol. 76:8939–8952. 10.1128/JVI.76.17.8939-8952.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fuchs W, Klupp BG, Granzow H, Osterrieder N, Mettenleiter TC. 2002. The interacting UL31 and UL34 gene products of pseudorabies virus are involved in egress from the host-cell nucleus and represent components of primary enveloped but not mature virions. J. Virol. 76:364–378. 10.1128/JVI.76.1.364-378.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ye GJ, Roizman B. 2000. The essential protein encoded by the UL31 gene of herpes simplex virus 1 depends for its stability on the presence of the UL34 protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:11002–11007. 10.1073/pnas.97.20.11002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klupp BG, Granzow H, Mettenleiter TC. 2001. Effect of the pseudorabies virus US3 protein on nuclear membrane localization of the UL34 protein and virus egress from the nucleus. J. Gen.Virol. 82:2363–2371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roller R, Zhou Y, Schnetzer R, Ferguson J, Desalvo D. 2000. Herpes simplex virus type 1 UL34 gene product is required for viral envelopment. J. Virol. 74:117–129. 10.1128/JVI.74.1.117-129.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holland LE, Sandri-Goldin RM, Goldin AL, Glorioso JC, Levine M. 1984. Transcriptional and genetic analyses of the herpes simplex virus type 1 genome: coordinates 0.29 to 0.45. J. Virol. 49:947–959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lake CM, Hutt-Fletcher LM. 2004. The Epstein-Barr virus BFRF1 and BFLF2 proteins interact and coexpression alters their cellular localization. Virology 320:99–106. 10.1016/j.virol.2003.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gonnella R, Farina A, Santarelli R, Raffa S, Feederle R, Bei R, Granato M, Modesti A, Frati L, Delecluse HJ, Torrisi MR, Angeloni A, Faggioni A. 2005. Characterization and intracellular localization of the Epstein-Barr virus protein BFLF2: interactions with BFRF1 and with the nuclear lamina. J. Virol. 79:3713–3727. 10.1128/JVI.79.6.3713-3727.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lotzerich M, Ruzsics Z, Koszinowski UH. 2006. Functional domains of murine cytomegalovirus nuclear egress protein M53/p38. J. Virol. 80:73–84. 10.1128/JVI.80.1.73-84.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang K, Baines JD. 2011. Selection of HSV capsids for envelopment involves interaction between capsid surface components pUL31, pUL17, and pUL25. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:14276–14281. 10.1073/pnas.1108564108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leelawong M, Guo D, Smith GA. 2011. A physical link between the pseudorabies virus capsid and the nuclear egress complex. J. Virol. 85:11675–11684. 10.1128/JVI.05614-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ejercito PM, Kieff ED, Roizman B. 1968. Characterization of herpes simplex virus strains differing in their effects on social behavior of infected cells. J. Gen. Virol. 2:357–364. 10.1099/0022-1317-2-3-357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cockrell SK, Sanchez ME, Erazo A, Homa FL. 2009. Role of the UL25 protein in herpes simplex virus DNA encapsidation. J. Virol. 83:47–57. 10.1128/JVI.01889-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tanaka M, Kagawa H, Yamanashi Y, Sata T, Kawaguchi Y. 2003. Construction of an excisable bacterial artificial chromosome containing a full-length infectious clone of herpes simplex virus type 1: viruses reconstituted from the clone exhibit wild-type properties in vitro and in vivo. J. Virol. 77:1382–1391. 10.1128/JVI.77.2.1382-1391.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liang L, Tanaka M, Kawaguchi Y, Baines JD. 2004. Cell lines that support replication of a novel herpes simplex 1 UL31 deletion mutant can properly target UL34 protein to the nuclear rim in the absence of UL31. Virology 329:68–76. 10.1016/j.virol.2004.07.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tischer BK, von Einem J, Kaufer B, Osterrieder N. 2006. Two-step RED-mediated recombination for versatile high-efficiency markerless DNA manipulation in Eschericia coli. Biotechniques 40:191–197. 10.2144/000112096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wills E, Scholtes L, Baines JD. 2006. Herpes simplex virus 1 DNA packaging proteins encoded by UL6, UL15, UL17, UL28, and UL33 are located on the external surface of the viral capsid. J. Virol. 80:10894–10899. 10.1128/JVI.01364-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kremer JR, Mastronarde DN, McIntosh JR. 1996. Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using IMOD. J. Struct. Biol. 116:71–76. 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mou F, Wills E, Baines JD. 2009. Phosphorylation of the herpes simplex virus 1 UL31 protein by the US3 encoded kinase regulates localization of the nuclear envelopment complex and egress of nucleocapsids. J. Virol. 83:5181–5191. 10.1128/JVI.00090-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wisner TW, Wright CC, Kato A, Kawaguchi Y, Mou F, Baines JD, Roller RJ, Johnson DC. 2009. Herpesvirus gB-induced fusion between the virion envelope and outer nuclear membrane during virus egress is regulated by the viral US3 kinase. J. Virol. 83:3115–3126. 10.1128/JVI.01462-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roberts KL, Baines JD. 2011. UL31 of herpes simplex virus 1 is necessary for optimal NF-κB activation and expression of viral gene products. J. Virol. 85:4947–4953. 10.1128/JVI.00068-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chang YE, Van Sant C, Krug PW, Sears AE, Roizman B. 1997. The null mutant of the UL31 gene of herpes simplex virus 1: construction and phenotype of infected cells. J. Virol. 71:8307–8315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.