Abstract

We developed a multiplex SYBR green real-time PCR for the BD Max instrument (BD Diagnostics, Sparks, MD) to detect a panel of carbapenemases. The assay was evaluated with 152 consecutive isolates sent to the German National Reference Laboratory, and 65/65 of the carbapenemase-positive and 87/87 of the carbapenemase-negative strains were identified correctly.

TEXT

Rapid detection and differentiation of carbapenemases are important for epidemiological investigations and infection control measures, thereby contributing to the prevention of global spread and optimization of antimicrobial therapy (1). Phenotype-based techniques can be used to identify carbapenemases (2–7), yet the specificity and sensitivity of those procedures vary. Other assays use matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF) (8), enzymatic measurements like the Carba NP test (9), and spectrophotometry (10). However, phenotypic and functional assays are often followed by molecular detection of the encoding carbapenemase genes. Molecular analysis is laborious, but fully automated PCR platforms might circumvent this restriction. Multiplexing allows detection in an economically reasonable manner (11).

In our study, SYBR green real-time PCR on the BD Max system (BD Diagnostics, Sparks, MD) combined with melt curve analysis was developed to detect frequent carbapenemases in cultured isolates. Primers were mixed in two multiplex PCRs (master mix 1 [MM1] and MM2) that were selected on differences in the melting points of the amplicons. Panel 1 (MM1) amplified IMP-1, IMP-2, GES, KPC, VIM-2, and 16S rRNA as an internal amplification control. Panel 2 (MM2) detected OXA-23-like, VIM-1, OXA-48-like, and NDM (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). One to 2 colonies of a suspect isolate were added to 0.5 ml of 10 mM Tris-1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) containing 0.1-mm glass beads (BioSpec, Bartlesville, OK). The sample was vortexed and incubated at 95°C for 10 min, and the cleared supernatant was directly used for the PCR. Each single reaction consisted of forward and reverse primers for each of the carbapenemases (final concentration, 0.25 μM), a primer for 16S rRNA (only MM1, 0.05 μM), 6.25 μl of 2× ABsolute SYBR green mix No Rox (Thermo Scientific, Schwerte, Germany), and PCR-grade water up to 10 μl. Then 2.5 μl of the strain lysate was combined with 10 μl of the respective master mix and pipetted manually into a microfluidic BD Max PCR cartridge. The PCR was run in the PCR-only mode at 95°C for 15 min for 30 PCR cycles (98°C, 30 s; 56°C, 20 s; 72°C, 51.1 s) followed by melt curve analysis from 60°C to 100°C in 0.2°C steps.

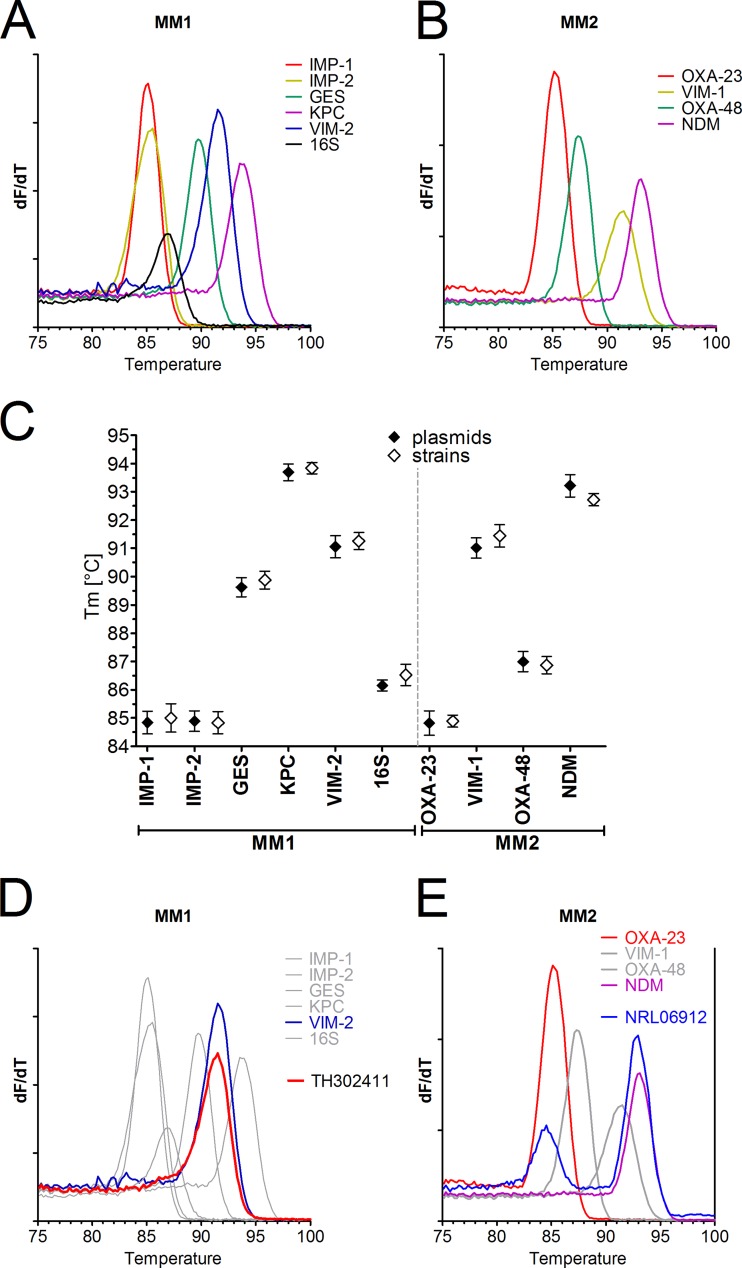

Using plasmids encoding the various carbapenemases, we observed clearly distinct melting temperatures (Fig. 1A and B). Only IMP-1 and IMP-2 could not be differentiated. Melting temperatures were consistent and highly reproducible (Fig. 1C). The strains harboring a carbapenemase gene could be identified by comparison to the reference temperatures obtained with plasmids (an example is shown in Fig. 1D). Even the combined presence of two carbapenemase genes in one isolate could be differentiated (Fig. 1E). As shown for plasmids, we also observed consistent and reproducible melting points with cultured isolates that showed agreement with the data obtained with plasmids (Fig. 1C).

FIG 1.

Development of a multiplex PCR for detection of carbapenemases based on amplicon melting point differences. Plasmids encompassing amplicons of the indicated carbapenemases were amplified by a SYBR green multiplex PCR mix for IMP-1, IMP-2 (IMP-8/-16), GES, VIM-2, KPC, and 16S rRNA (master mix 1 [MM1]) (A) or OXA-23-like, OXA-48-like, VIM-1, and NDM (master mix 2 [MM2]) in the PCR-only mode on the BD Max cycler followed by melt curve analysis (B). The first derivate dF/dT is shown. (C) Plasmids were tested in 4 replicates on 3 different BD Max cyclers (n = 12, mean ± SD) (closed symbols). In a similar manner, one typical strain from a reference collection, encoding a respective carbapenemase, was tested in 3 replicates on 3 BD Max cyclers (n = 9, mean ± SD) (open symbols). The melting point temperatures (Tm) are indicated for the various amplicons detected by MM1 and MM2. (D) A clinical isolate (TH302411) analyzed by amplification with master mix 1 was identified as VIM-2 positive by comparison to the reference panel. (E) An isolate (NRL06912) with two carbapenemases (OXA-23 and NDM) was tested with master mix 2.

To further evaluate the assay, we analyzed 89 carbapenemase-positive strains that contained carbapenemase genes covered by the primer panel and 40 strains that were negative for carbapenemases (a collection received from the German National Reference Laboratory [NRL], see the supplemental material). Of the positive strains, 81 (91.0%) were correctly identified with the assay (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Of the carbapenemase genes, 8 (9.0%) were not detected due to missing amplification. The failures occurred only among IMP-type variants. All 40 of the strains with decreased carbapenem susceptibility and without detection of a defined carbapenemase were concordantly negative in our assay.

Next we analyzed, in a blinded study, 152 consecutive isolates sent to the NRL in an entire half-month period (Table 1). The collection had a positivity rate of 65/152 (42.8%) for the presence of carbapenemases (including GES β-lactamase). All of the carbapenemase-positive strains (65/65) and all of the negative strains (87/87) were identified correctly. Thus, the described assay on the BD Max instrument is a valuable tool for simultaneously discriminating 8 carbapenemases from different Ambler classes and GES β-lactamases among Enterobacteriaceae and nonfermenters. Only 4 isolates showed a weak amplicon with an atypical melting temperature that did not fit to any of the reference curves (Table 1). Those isolates were Proteus mirabilis strains with an unspecific amplicon. We calculated the assay's expected performance for all Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Acinetobacter baumannii isolates sent to the NRL in the entire year 2012 (n = 1,150). Based on the included primer, the assay would have detected 582/586 (99.0%) carbapenemases in Enterobacteriaceae, 138/154 (89.6%) in P. aeruginosa, and 359/410 (87.6%) in A. baumannii, giving rise to a theoretical overall sensitivity of 93.7%.

TABLE 1.

Performance of the BD Max carbapenemase assay in a routine setting on consecutively collected samples

| Carbapenemase type | Species (no.)a | BD Max comparison to NRL |

% of all carbapenemases or GES enzymes (n = 645) | Remark | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. concordant | No. discordant | ||||

| KPC-2/-3 | klpn (8) | 8 | 0 | 12.3 | |

| NDM-1/-6 | esco (1), klpn (2), acba (2) | 5 | 0 | 7.7 | |

| NDM-1/-6 and OXA-23 | acba | 1 | 0 | 1.5 | |

| OXA-23 | acba (12), prmi (1) | 13 | 0 | 20.0 | |

| OXA-48/-181 | klpn (7), esco (3) | 10 | 0 | 15.3 | 1 OXA-181 isolate identified as OXA-48-like |

| VIM-1 | klox (3), encl (2), esco (6), klpn (2) | 13 | 0 | 20.0 | |

| VIM-2 | psae (10) | 10 | 0 | 15.3 | |

| GES | psae (5) | 5 | 0 | 7.7 | |

| Isolates without carbapenemase | 87 (83)b | 0 | |||

acba, Acinetobacter baumannii; encl, Enterobacter cloacae; esco, Escherichia coli; klox, Klebsiella oxytoca; klpn, Klebsiella pneumoniae; prmi, Proteus mirabilis; psae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Four isolates (Proteus mirabilis isolates) showed a weak amplicon with an undefined melting temperature (Tm) of 83.7°C in MM2. Sequencing of the amplicons identified an unrelated genomic region in P. mirabilis amplified with the OXA-23-like primer pair. The results were rated negative.

The basis of most current assays is gel-based PCR that may be followed by sequencing (12). Thus, our assay speeds up analysis. The second advantage is the potential for fully automated carbapenemase detection. In this study, the assay was initially evaluated in the PCR-only mode using the BD Max system as a real-time cycler. However, the setup of this platform allows running of in-house assays with automated nucleic acid extraction and PCR. Flexible changes in the composition of the primer panels used would be possible. For the fully automated PCR, we used an ExK-DNA-3 extraction kit (BD). Two PCR mixes of 18 μl each were prepared in conical snap-in tubes fitting the BD Max extraction strip and sealed using an adhesive cover foil (PlateMax sealer, sealed twice for 8 s at 180°C; Axygen). This mix was added into position 2 of the unitized reaction strip. Position 3 was filled with 100 μl of 10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA (pH 8) buffer to neutralize the elution solution. A colony was picked and added together with 750 μl water into the sample buffer tube. The full process was run as a type 2 reaction (liquid primer probes). Using defined strains in 3 to 6 repeats, we observed melting temperatures as follows: IMP-1, 85.0 ± 0.4°C (mean ± standard deviation [SD]); IMP-2, 84.5 ± 0.4°C; 16S, 86.6 ± 0.2°C; GES, 89.4 ± 0.3°C; VIM-2, 90.5 ± 0.2°C; KPC, 93.1 ± 0.4°C; OXA-23-like, 84.8 ± 0.4°C; OXA-48-like, 87.0 ± 0.2°C; VIM-1, 91.5 ± 0.1°C; and NDM, 92.8 ± 0.2°C. Melting temperatures were well separated as observed with plasmids and strains in the PCR-only mode (Fig. 1C). The results confirm feasibility in the fully automated detection mode.

Overall, a few weaknesses of this assay were observed: The assay missed some IMP-type carbapenemases, which has also been reported for commercial multiplex PCR assays (13). The importance of IMP-type isolates can be questioned for our region, because among the analyzed consecutive isolates no single IMP-positive isolate was present. With respect to the choice of molecular targets in our study, some carbapenemases frequently found in the A. baumannii complex (e.g., OXA-58) are lacking. However, for Enterobacteriaceae and P. aeruginosa, the most frequent carbapenemases are covered. Another disadvantage is that at present two extraction reactions must be run in the automated mode. A new reaction strip that allows running of two PCRs from one extraction is in development.

In conclusion, the results of our study show that melting point-based identification of PCR-amplified carbapenemase resistance genes on the BD Max system allows easy, rapid, sensitive, and specific detection of carbapenemases.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Robert Koch Institute with funds provided by the German Ministry of Health (grant 1369-402). BD Diagnostics supported the study by providing consumables but had no influence on the design or evaluation of the entire study.

A.H.D. and S.Z. have each received a speaker's honorarium from BD Diagnostics. M.K. has received speaker or consultancy fees or research grants from Amplex, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Becton, Dickinson, bioMérieux, Bio-Rad, Infectopharm, MSD, Pfizer, Roche Diagnostics, and Siemens Healthcare.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 12 February 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00373-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Miriagou V, Cornaglia G, Edelstein M, Galani I, Giske CG, Gniadkowski M, Malamou-Lada E, Martinez-Martinez L, Navarro F, Nordmann P, Peixe L, Pournaras S, Rossolini GM, Tsakris A, Vatopoulos A, Canton R. 2010. Acquired carbapenemases in Gram-negative bacterial pathogens: detection and surveillance issues. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16:112–122. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03116.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pasteran F, Mendez T, Guerriero L, Rapoport M, Corso A. 2009. Sensitive screening tests for suspected class A carbapenemase production in species of Enterobacteriaceae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:1631–1639. 10.1128/JCM.00130-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giske CG, Gezelius L, Samuelsen O, Warner M, Sundsfjord A, Woodford N. 2011. A sensitive and specific phenotypic assay for detection of metallo-β-lactamases and KPC in Klebsiella pneumoniae with the use of meropenem disks supplemented with aminophenylboronic acid, dipicolinic acid and cloxacillin. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 17:552–556. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03294.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nordmann P, Poirel L. 2013. Strategies for identification of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 68:487–489. 10.1093/jac/dks426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vasoo S, Cunningham SA, Kohner PC, Simner PJ, Mandrekar JN, Lolans K, Hayden MK, Patel R. 2013. Comparison of a novel, rapid chromogenic biochemical assay, the Carba NP test, with the modified Hodge test for detection of carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative bacilli. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51:3097–3101. 10.1128/JCM.00965-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marchiaro P, Mussi MA, Ballerini V, Pasteran F, Viale AM, Vila AJ, Limansky AS. 2005. Sensitive EDTA-based microbiological assays for detection of metallo-β-lactamases in nonfermentative gram-negative bacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:5648–5652. 10.1128/JCM.43.11.5648-5652.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2010. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 20th informational supplement. CLSI M100-S20. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burckhardt I, Zimmermann S. 2011. Using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry to detect carbapenem resistance within 1 to 2.5 hours. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:3321–3324. 10.1128/JCM.00287-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nordmann P, Poirel L, Dortet L. 2012. Rapid detection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 18:1503–1507. 10.3201/eid1809.120355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernabeu S, Poirel L, Nordmann P. 2012. Spectrophotometry-based detection of carbapenemase producers among Enterobacteriaceae. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 74:88–90. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monteiro J, Widen RH, Pignatari AC, Kubasek C, Silbert S. 2012. Rapid detection of carbapenemase genes by multiplex real-time PCR. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67:906–909. 10.1093/jac/dkr563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nordmann P, Gniadkowski M, Giske CG, Poirel L, Woodford N, Miriagou V. 2012. Identification and screening of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18:432–438. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03815.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaase M, Szabados F, Wassill L, Gatermann SG. 2012. Detection of carbapenemases in enterobacteriaceae by a commercial multiplex PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50:3115–3118. 10.1128/JCM.00991-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.