ABSTRACT

An understanding of the antigen-specific B-cell response to the influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) is critical to the development of universal influenza vaccines, but it has not been possible to examine these cells directly because HA binds to sialic acid (SA) on most cell types. Here, we use structure-based modification of HA to isolate HA-specific B cells by flow cytometry and characterize the features of HA stem antibodies (Abs) required for their development. Incorporation of a previously described mutation (Y98F) to the receptor binding site (RBS) causes HA to bind only those B cells that express HA-specific Abs, but it does not bind nonspecifically to B cells, and this mutation has no effect on the binding of broadly neutralizing Abs to the RBS. To test the specificity of the Y98F mutation, we first demonstrated that previously described HA nanoparticles mediate hemagglutination and then determined that the Y98F mutation eliminates this activity. Cloning of immunoglobulin genes from HA-specific B cells isolated from a single human subject demonstrates that vaccination with H5N1 influenza virus can elicit B cells expressing stem monoclonal Abs (MAbs). Although these MAbs originated mostly from the IGHV1-69 germ line, a reasonable proportion derived from other genes. Analysis of stem Abs provides insight into the maturation pathways of IGVH1-69-derived stem Abs. Furthermore, this analysis shows that multiple non-IGHV1-69 stem Abs with a similar neutralizing breadth develop after vaccination in humans, suggesting that the HA stem response can be elicited in individuals with non-stem-reactive IGHV1-69 alleles.

IMPORTANCE Universal influenza vaccines would improve immune protection against infection and facilitate vaccine manufacturing and distribution. Flu vaccines stimulate B cells in the blood to produce antibodies that neutralize the virus. These antibodies target a protein on the surface of the virus called HA. Flu vaccines must be reformulated annually, because these antibodies are mostly specific to the viral strains used in the vaccine. But humans can produce broadly neutralizing antibodies. We sought to isolate B cells whose genes encode influenza virus antibodies from a patient vaccinated for avian influenza. To do so, we modified HA so it would bind only the desired cells. Sequencing the antibody genes of cells marked by this probe proved that the patient produced broadly neutralizing antibodies in response to the vaccine. Many sequences obtained had not been observed before. There are more ways to generate broadly neutralizing antibodies for influenza virus than previously thought.

INTRODUCTION

Identification of broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs) against influenza virus and determination of their crystal structures have encouraged efforts to develop broadly protective influenza vaccines (1–6). Most known influenza virus bnAbs bind a conserved epitope in the stem domain of hemagglutinin (HA), neutralize virus in vitro, and are protective when administered to mice or ferrets (2, 7, 8). Like the prototypic bnAbs F10 and CR6261, many derive from the IGHV1-69 germ line gene (2, 7, 9–12). A vaccine that could elicit bnAbs at protective titers would diminish the threat posed by pandemic influenza and reduce the need for annual vaccination. To better characterize the immune response to vaccination in clinical trials, we sought to develop tools for flow cytometric analysis of the antigen-specific response to influenza virus antigen HA.

Isolation of influenza virus HA-specific B cells by flow cytometry has been problematic to date. Though others have reported enrichment for HA-binding B cells by flow cytometry (13), we find that recombinant HA labels most cells. We inferred that nonspecific cell labeling by HA was due to binding to its cell-surface receptor, sialic acid (SA) (14). HA binds SA at a conserved shallow pocket at its membrane-distal end, termed the receptor binding site (RBS). As SA is a component of N-linked sugars attached to many eukaryotic proteins, and is also part of several surface glycolipids (15), receptor activity for HA confounds identification of influenza virus HA-specific B cells.

To address this problem, we sought to modify HA to prevent binding to SA. To this end, we used knowledge of the structure of HA to eliminate specificity for SA yet preserve binding of antibodies directed to the RBS. We then employed this modified HA, termed HAΔSA, as a flow cytometry probe to characterize the B-cell profile of an individual enrolled in a phase I influenza vaccine trial. We find that B cells targeting conserved sites are largely stem specific and broadly neutralizing. Here, our methodology revealed that both IGHV1-69-dependent and -independent pathways lead to production of anti-stem bnAbs. Moreover, although inheritance of the major allele of IGVH1-69 is important, it is not obligatory for eliciting stem-directed antibodies in response to vaccination.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical samples.

Clinical samples used in this study were collected in a phase I clinical trial (VRC 310) (16). Briefly, H5 DNA vaccine manufactured at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Vaccine Research Center's (VRC) Vaccine Pilot Plant, operated by SAIC (Frederick, MD), consisting of a closed-circular plasmid DNA macromolecule (VRC-9123) that expresses an A/Indonesia/5/2005 (H5N1) HA sequence, was administered as a prime. Primed subjects were boosted 4 to 24 weeks later with H5N1 monovalent inactivated vaccine (MIV) (A/Indonesia/05/2005), at a concentration of 90 μg/0.5 ml, produced by Sanofi Pasteur (Swiftwater, PA) in accordance with the methods used to manufacture the licensed influenza virus vaccine Fluzone. A control group received MIV twice with a 24-week interval. The subject from whom antibodies were cloned in this study received the MIV 4 weeks after the DNA prime. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) drawn 2 weeks after vaccination were used for flow cytometry and sorting experiments as detailed below. All procedures were approved by the NIAID Institutional Review Board.

Expression of HA probes.

HA probes consisting of the extracellular domain of HA C-terminally fused to the trimeric FoldOn of T4 fibritin, the biotinylatable AviTag sequence GLNDIFEAQKIEWHE, and a hexahistidine affinity tag were made synthetically and cloned into pVRC8400, a plasmid containing the cytomegalovirus (CMV) IE enhancer/promoter, human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) R region and splice donor site, and the CMV IE splice acceptor site upstream of the open reading frame. Mutations 190N and 192T to create ΔRBS (introduction of the sequence N-X-T at positions 190 to 192 leads to N-linked glycosylation at residue 190) or the mutation Y98F to create ΔSA was introduced by site-directed mutagenesis. Mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing. Plasmid DNA was prepared by Maxiprep (Origene). 293F cells grown in FreeStyle medium (Invitrogen) in baffled flasks were diluted to 1.2 × 106 cells/ml and transfected with 500 μg/liter of HA probe plasmid and 25 μg/liter of plasmid encoding strain-matched influenza virus neuraminidase (NA) using 1 ml per liter of culture volume of 293Fectin transfection reagent. At day 5, the media was clarified by centrifugation at 2,000 × g and filtered, concentrated, diafiltered against 4 volumes of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 20 mM imidazole (pH 8), and loaded on Ni Sepharose Fast Flow resin (GE Healthcare) by gravity flow. The resin was washed with 6 column volumes of PBS with 60 mM imidazole and the protein was eluted in 5 column volumes of PBS with 500 mM imidazole. The eluted protein was stored at 4°C overnight, concentrated with a centrifugal concentrator, and loaded on a Superdex 200 16/60 column. The fractions corresponding to trimeric HA (peak at 60 ml) were pooled and concentrated to 2 mg/ml protein. Eight hundred microliters of protein in 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0) was biotinylated using biotin protein ligase (Avidity) by the addition of 100 μl of Biomix-A, 100 μl of Biomix-B, and 2.5 μl of biotin ligase BirA and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The resulting biotinylated protein was exchanged into PBS with a centrifugal concentrator to remove excess biotin. Biotinylation was confirmed by capture with streptavidin-coated plates and was detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with anti-HA antibody.

Flow cytometric analysis and cell sorting.

Labeling of HA probes was achieved by the sequential addition of fluorescently labeled streptavidin, with HA in excess to streptavidin. Streptavidin labeled with phycoerythrin (PE) or allophycocyanin (APC) was used. Flow cytometric analysis of 293F cells transfected with membrane-bound IgM was performed as reported (17). The appropriate concentration of probe, typically ∼0.05 μg probe per sample, was determined by titration against human PBMCs or a B-cell hybridoma specific for H5 HA. Human PBMCs were stained with the following labeled monoclonal antibodies: CD3-QD655, CD14-QD800, and CD27-QD605 (Invitrogen); CD19-ECD (Beckman Coulter); CD20-Cy7APC (Biolegend); CD21 BV450 (BD Horizon); CD24-Cy7PE, CD22-Cy5PE, CD38-Ax680, IgM-Cy5.5-peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP), and IgG-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (BD Pharmingen). Cell viability was assessed using Aqua Blue amine-reactive dye (Invitrogen). Samples were analyzed using an LSR II instrument (BD Immunocytometry Systems) configured to detect 18 fluorochromes. One to two million events were collected per sample and analyzed using FlowJo software version 9.5.2 (TreeStar). For cell sorting, 92 live CD3− CD19+ CD14− H1+ H5+ cells were sorted into a 96-well plate containing lysis buffer. Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) amplification was performed according to the method of Tiller et al. (18), and PCR products were sequenced by Genewiz, Inc. Sequences were analyzed using IGMT/V-QUEST (19, 20) and grouped into clones in which the complementarity-determining region H3 (CDR-H3) sequence of every member was identical.

Cloning of antibodies.

Immunoglobulin heavy chain or kappa light chains were constructed by gene synthesis and inserted into plasmid pVRC8400 containing the respective IgG heavy-chain or kappa light-chain constant region fragments by using restriction enzymes AgeI and SalI, or AgeI and BsiWI, respectively. Lambda light chains were amplified using PCR from the RT-PCR product and cloned into pVRC8400 containing a light-chain constant region fragment using the restriction enzymes AgeI and XhoI. Antibodies were expressed from 293F cells transiently transfected with 250 μg/liter each of heavy and light chains and were purified with protein A Sepharose resin. For affinity measurement studies, corresponding Fab fragments were generated using PCR methods to replace the appropriate portion of the heavy-chain constant region with a C-terminal hexahistidine tag for expression and purification by affinity chromatography.

Neutralization and hemagglutination assays.

HA-pseudotyped viruses were prepared and used in neutralization and hemagglutination assays as previously described (21). The HA and NA genes used were derived from the following strains: H1N1 A/South Carolina/1/1918 (1918 SC), H1N1 A/PR8/8/34 (1934 PR8), H1N1 A/Fort Monmouth/1/47 (1947 FM), H1N1 A/New Caledonia/20/1999 (1999 NC), H1N1 A/Brisbane/59/07 (2007 Bris), H1N1 A/Mexico/4114/2009 (2009 Mex), H5N1 A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (2004 VN), H5N1 A/Indonesia/05/05 (2005 Indo), and H5N1 A/Nigeria/641/2006 (2006 Nige). Production of HA-ferritin nanoparticles (np) is described in reference 22. Hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) was performed by preincubation of H1N1 A/New Caledonia/20/1999 influenza virus (4 HA units) with serially diluted monoclonal antibody (50 μg at 0.781 μg/ml) for 30 min followed by application of 0.5% chicken red blood cells. The mixture was incubated at room temperature, and measurements were taken after 30 min. Ferret sera taken before (n = 6) or after (n = 24) vaccination with 1999 NC were pretreated with receptor-destroying enzyme, heat inactivated, and tested as described above. The Pearson correlation was calculated using the computer program PRISM.

ELISA to verify antigenicity of HAΔSA probe.

Ninety-six-well plates (Immulon 4HBX) were coated overnight at 4°C with either 0.70 HA units/well of purified PR8 virus or 200 ng/well of PR8 HA probe in PBS and then washed with PBS containing 0.05% (vol/vol) Tween 20 and blocked with PBS–0.5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) for 2 h. The following antibodies were tested: PEG-1, Y8-2C6, Y8-3B3, Y8-10C2, H37-76, Y8-1A6, and H37-101 (Sa site); H35-C3, H28-E23, H28-D14, H37-72, Y8-1C1, H36-6, H37-22, and H37-41 (Sb site); H17 L10, H17 L19, and 230-5 (Ca1 site); H18-L9, H37-90, and H18-S210 (Ca2 site); and H19-A15, H9-D3, H35-C10, H35-C12, and H120-2 (Cb site). Anti-HA Ab was titrated from nondetectable to saturating binding levels and incubated with antigen overnight at 4°C. After primary incubation, plates were washed, and rat anti-mouse kappa conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Southern Biotech) was used to visualize monoclonal Ab (MAb) binding. Plates were developed for 5 min using tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate (KPL Biomedical) and halted by the addition of 0.1 N HCl, after which plates were read at 450 nm. Ab avidities were determined using PRISM software, and all avidities reported demonstrated excellent fit for one-site binding with Hill slope curve fitting (R2 values, >0.98).

Binding studies using biolayer interferometry on the Octet Red384 system and ELISA.

Affinity measurements were obtained using purified Fab fragments in solution, binding to biotinylated HA noncovalently conjugated to streptavidin-coated plates according to previously described methods (23). ELISA was performed using 96-well MaxiSorb plates (Thermo Scientific) with 200 ng HA per well in phosphate-buffered saline. Blocking and dilution of antibodies were performed with blocking/diluent solution (Immune Technologies) and binding was detected with anti-human secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and SureBlue TMB Microwell peroxidase (KPL).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Sequences for HA probes were deposited in GenBank as accession numbers KF998099, KF998100, KF998101, and KF998102. Sequences for immunoglobulin genes were deposited in GenBank as accession numbers KJ149297 to KJ149446.

RESULTS

Design of the HA-specific B-cell probe.

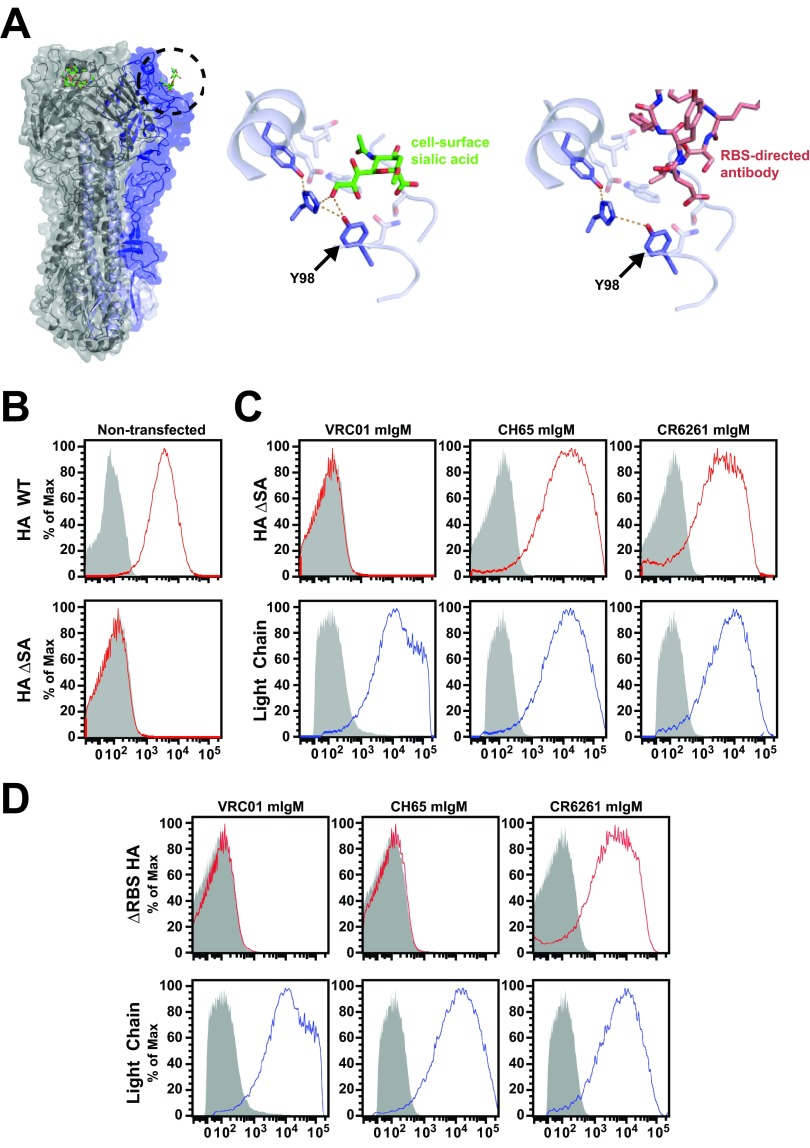

In a previous study, we used HA in which the RBS is blocked by introduction of an artificial glycosylation site to overcome nonspecific binding (17). However, this protein, called HAΔRBS, is not useful as a general purpose HA probe, because it cannot bind antibodies directed at or near the RBS. Instead, to eliminate nonspecific binding, we considered using one of the various point mutations that have been shown by others to ablate SA binding (14, 24, 25). Comparison of crystal structures of HA in complex with an SA analog (26) or with the RBS-directed antibody CH65 (5) (Fig. 1A) suggested that one of these known mutations, Y98F, would not affect binding of this particular RBS-directed antibody or that of others similar to it. The CDR-H3 loop of CH65 projects into the RBS and makes contacts with HA that are chemically analogous to those made by SA. However, SA makes additional polar contacts with Y98 that are not mimicked by CH65. The Y98F mutation removes a single oxygen atom from HA; this is sufficient to prevent binding to SA. In this work, we describe HA bearing the mutation Y98F as HAΔSA. We hypothesized that HAΔSA would specifically bind B cells expressing antibody against HA, enabling reliable flow cytometric isolation of these cells, and furthermore, that isolation of immunoglobulin genes from H1/H5 cross-reactive B cells would yield antibodies that target the conserved stem epitope on HA.

FIG 1.

Design and characterization of influenza virus HA-specific flow cytometry probe HAΔSA. (A) Crystal structures of HA in complex with SA analog or CH65 antibody illustrating interaction with tyrosine 98. Influenza virus HA (gray) is shown with one unit of the trimer colored (blue). The SA analog LSTc is shown bound to each unit. The circled area is shown enlarged, in complex with either SA (middle, green) or the CDR-H3 loop of the antibody CH65 (right, red). Tyrosine 98 makes polar contacts (dashed lines) with the adjacent histidine 183 and with SA (middle), but not the antibody (right). Mutation of tyrosine 98 to phenylalanine (right) removes the possibility of forming this polar contact with SA but has no effect on the interaction with the antibody. As the interaction with SA is weak (mM binding constant), removal of this polar contact eliminates binding. (B) HAΔSA mutation eliminates nonspecific binding. Wild-type (HA WT) or mutant (HA ΔSA) HA probes were conjugated to streptavidin-PE and used to label 293F cells grown in suspension. The no-probe control is shown in gray. Wild-type HA labels cells nonspecifically (top); HAΔSA does not (bottom). (C) Validation of the HAΔSA probe using cultured 293F cells transfected with membrane-bound IgM antibody genes. Cells transfected with the membrane-bound IgM form of HIV Env-specific control antibody VRC01, or RBS-directed antibody HA-specific CH65, or stem-directed antibody CR6261 express the respective antibody on the cell surface (anti-light-chain labeling, blue). Cells transfected with HA-directed antibody are labeled by HAΔSA, but those that express the anti-HIV antibody are not (HAΔSA labeling, red). The no-probe controls are shown in gray. (D) HAΔRBS labels only the stem-directed antibody CR6261, not the RBS-directed antibody CH65. The experiment was performed as described for that in panel C.

HAΔSA and HAΔRBS were expressed as soluble recombinant proteins, C-terminally fused to trimeric T4 fibritin FoldOn and the AviTag sequence, which allows for enzymatic conjugation to one biotin molecule per HA monomer. As envisaged, HAΔSA preserves binding to CH65 and to CR6261 with no change in affinity relative to that of HA (Table 1). We also tested the RBS-directed cross-neutralizing monoclonal antibody C05 (27). It too binds HAΔSA, 6-fold more strongly than HA (Table 1). Based on our results with these two antibodies that bind the RBS, we believe that most HA-specific antibodies should also bind HA with the Y98F mutation; therefore, sorting with HAΔSA probes should minimally bias the repertoire of recovered antibodies.

TABLE 1.

HAΔSA mutation does not affect binding to influenza virus antibodies CR6261, CH65, and C05a

| Interaction | KD (M) | kon (1/s · M) | koff (1/s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CR6261 to HA | 4.40 × 10−9 | 1.36 × 104 | 5.99 × 10−5 |

| CR6261 to HAΔSA | 4.76 × 10−9 | 1.36 × 104 | 6.46 × 10−5 |

| CH65 to HA | 5.87 × 10−7 | 1.26 × 105 | 7.38 × 10−2 |

| CH65 to HAΔSA | 4.71 × 10−7 | 1.33 × 105 | 6.26 × 10−2 |

| C05 to HA | 3.33 × 10−8 | 2.96 × 104 | 9.88 × 10−4 |

| C05 to HAΔSA | 5.55 × 10−9 | 1.50 × 105 | 8.32 × 10−4 |

kon, association rate constant; koff, dissociation rate constant.

The biotinylated HA proteins were bound to fluorescently labeled streptavidin, and the resulting probes were used to characterize cells by flow cytometry. Similar to human lymphocytes, wild-type HA bound to 293F cells nonspecifically (Fig. 1B). HAΔSA did not stain nontransfected cells (Fig. 1B) nor cells transfected with a negative-control anti-HIV antibody; in contrast, it labeled cells transfected with CH65 or CR6261 IgM (Fig. 1C). As expected, HAΔRBS bound to cells transfected with stem-directed CR6261 IgM, but not CH65 (Fig. 1D). HAΔSA probes were made for each of the serotypes of influenza virus type A that currently circulate or recently have circulated in humans, including pre-2009 seasonal H1N1 (A/New Caledonia/20/1999), 2009 pandemic H1N1 (A/California/4/2009, H1/1999), and H3N2 (A/Perth/16/2009), as well as for H5N1 (A/Indonesia/05/2005, H5/2005).

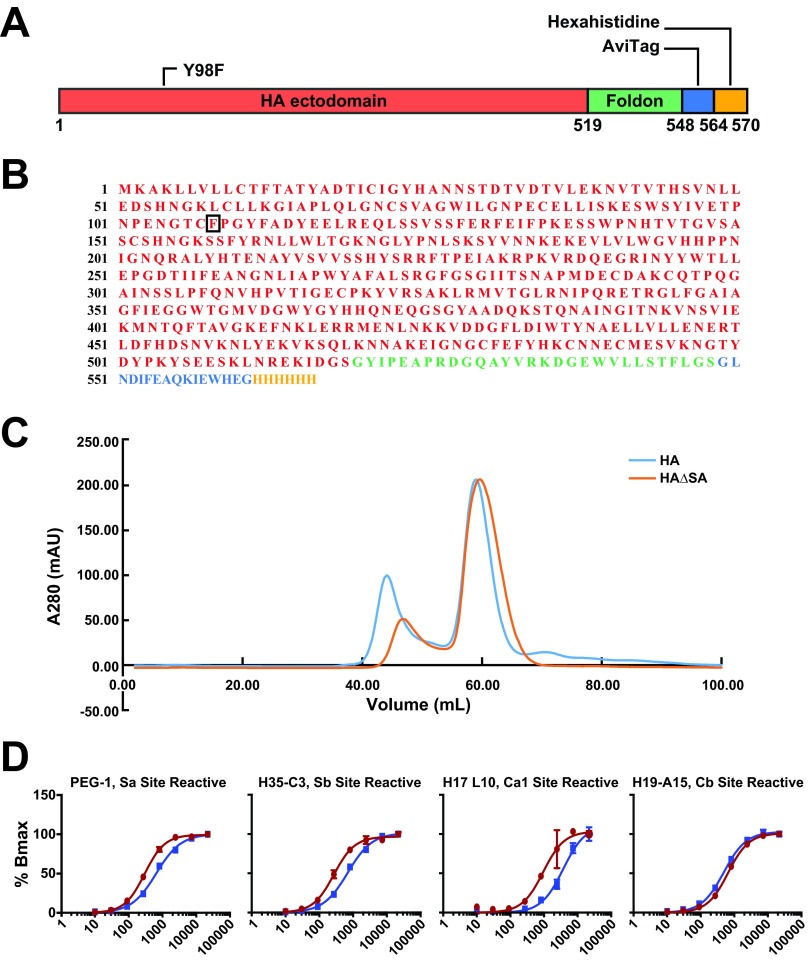

The design of the H1/1999 HAΔSA probe and its sequence are shown in Fig. 2A and B. Sequences for all probes were deposited in GenBank. HAΔSA probes form native-like trimers (Fig. 2C). To ensure that Y98F does not allosterically alter other epitopes, 25 head-specific antibodies against the 1934 H1N1 PR8 strain were tested using HAΔSA matched to that strain. Of these antibodies, 24 of 25 bound HAΔSA similarly to PR8 virus (Fig. 2D).

FIG 2.

Schematic diagram and characterization of the HAΔSA probe. (A) Schematic diagram for HAΔSA probe. The ectodomain of HA (red), including the native N-terminal signal peptide, was fused to the T4 fibritin FoldOn (green), an AviTag (blue), and a hexahistidine purification tag (yellow). Numbering is according to the protein sequence of the construct. Position 98 of HA1 (HA numbering) was mutated to phenylalanine as described in the text. (B) Protein sequence for the H1/1999 HAΔSA probe, colored as in panel A. (C) Gel filtration chromatography of HA or HAΔSA on Superdex 200 16/60 column. HA and HAΔSA have similar elution profiles. Both elute at 58 ml, consistent with formation of the desired trimeric complex. A280, absorption at 280 nm; mAU, milliabsorbance units. (D) A panel of antibodies specific to the five antigenic sites of PR8 HA was tested against the PR8 HAΔSA probe and whole PR8 virus by ELISA titration. Representative ELISA curve plots for Sa, Sb, Ca1/Ca2, and Cb site-reactive antibodies are shown. Of the 25 tested, only one antibody, H37-76, was poorly reactive to the HAΔSA probe.

Hemagglutination with HA nanoparticles.

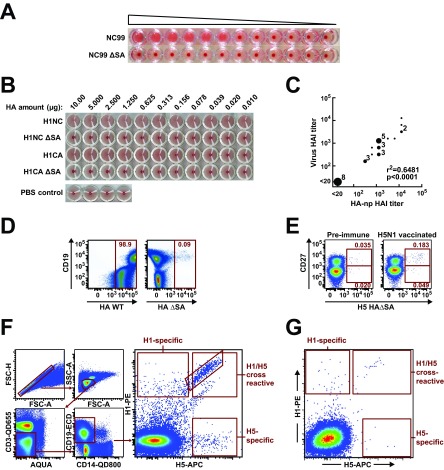

We next evaluated the effect of this mutation in a hemagglutination assay that uses a synthetic HA nanoparticle (22) in place of live virus. Hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) by serum antibody is an established correlate of influenza vaccine efficacy. We find that native HA in the form of HA np or HA-pseudotyped lentiviral vectors (21, 28) agglutinates red blood cells; in contrast, HAΔSA in either form does not (Fig. 3A and B). HA nanoparticles and virus gave comparable titers when ferret antisera were tested (Fig. 3C). These results demonstrate that HA np can be used to perform an HAI assay and that binding is dependent on SA engagement even when the structure of the RBS remains intact.

FIG 3.

H1 and H5 HAΔSA probes identify B cells expressing strain-specific and cross-reactive antibodies against influenza virus HA. (A) Hemagglutination by lentivirus pseudotyped with H1N1 wild-type HA (NC99) or HAΔSA (NC99 ΔSA). Pseudovirus was diluted 1:4 from left to right. (B) Hemagglutination by HA-ferritin nanoparticles displaying the respective seasonal (NC99) or pandemic (CA09) H1N1 HA or HAΔSA. Pseudotyped lentivirus or HA-ferritin nanoparticles (np) (22) agglutinate red blood cells; the respective Y98F mutants of HA do not. Concentrations were determined by UV absorbance and serial dilutions performed from left to right as indicated. Formation of a dark red dot indicates failure to agglutinate at a given concentration. (C) Correlation between HAI measured with virus or HA np. Sera from ferrets vaccinated against A/New Caledonia/20/99 (H1N1) were tested against virus or strain-matched HA np. (D) Validation of the HAΔSA probe using B cells from a human donor. Human donor PBMCs were analyzed by flow cytometry. The wild-type probe labels nearly all cells (left); the HAΔSA probe does not (right). Probes were purified and labeled in the same manner, and identical concentrations of each probe were used to label the cells. (E) Effect of vaccination for H5N1 influenza virus on the frequency of H5+ cells. PBMC samples from one subject (VRC 310-036) drawn before vaccination for H5N1 (left), or 2 weeks afterward (right), were labeled with the HAΔSA probe corresponding to the vaccine strain, the B-cell maturation marker CD27, and other B-cell markers as described in Materials and Methods. Vaccination against H5N1 influenza virus increases the proportion of antigen-specific CD19+ CD27− and CD19+ CD27+ B cells, detected by the H5 HAΔSA probe. (F) Sorting for H1/H5 cross-reactive B cells. PMBCs were sequentially gated to isolate lymphocytes and to remove doublets, CD3+ T cells, CD14+ monocytes, and dead cells stained by the Aqua viability dye. Antigen specificity of CD19+ B cells was assessed using binding to H1 HAΔSA conjugated to streptavidin-PE and H5 HAΔSA conjugated to streptavidin-APC. A set of 92 single B cells from a single subject (VRC 310-018) were index-sorted and subjected to antibody gene sequencing. (G) PBMCs from a prevaccination sample from the same patient were analyzed as in panel F.

B-cell profiling in response to vaccination.

H1/1999 and H5/2005 HAΔSA probes were used to quantify antigen-specific B cells sampled before or following H5 DNA-prime/monovalent inactivated H5N1 boost vaccination in the clinical trial VRC 310 (16, 29). The contrast between the results obtained with wild-type HA and with HAΔSA was dramatic: wild-type HA bound to more than 98% of human B cells, while HAΔSA bound less than 0.1% of B cells (Fig. 3D). Furthermore, the H5 HAΔSA probe bound to an increased proportion of B cells following vaccination with H5N1 (Fig. 3E, F, and G) compared to prevaccination levels. To isolate the cross-reactive neutralizing antibody gene sequences expressed by these cells and thereby confirm the specificity of HAΔSA probes, we sorted single cells from the H1/H5 double-positive memory B-cell pool from a postvaccination PBMC sample (Fig. 3F). In the postvaccination sample, of total CD19+ B cells, 7.3% had a class-switched memory phenotype (IgG+ CD27+); of these, 3.4% were HA specific. Within this population of HA-specific memory B cells, 74.3% were cross-reactive with both H1 and H5 probes. Using established methods (18), we amplified the immunoglobulin genes by RT-PCR and sequenced the resulting DNA fragments, obtaining sequences for 77 heavy-chain genes and the corresponding light chain for 66 of these (Fig. 4). The majority of known HA stem-directed bnAbs employ the IGVH1-69 gene (17). Similarly, we observed that 78% of the 77 antibodies from H1/H5 double-positive B cells derive from the IGVH1-69 germ line. We used the sequence of the CDR-H3 loop to cluster the antibodies into 15 clonal families, each containing between two and five sequences, leaving 42 unique antibodies.

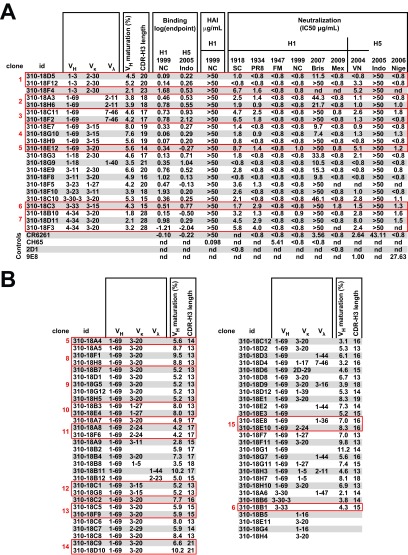

FIG 4.

H1/H5 cross-reactive antibodies bind H1 and H5 HAs and neutralize HA-pseudotyped lentivirus vectors. (A) Monoclonal antibodies for 22 selected sequences were expressed and tested by ELISA for binding to H1 or H5 HA, for HAI, and for their ability to neutralize replication-defective lentiviral vector pseudotyped with HA from the various H1 and H5 strains indicated. Binding is expressed as the base-10 logarithm of the concentration in μg/ml. HAI is expressed as the minimum concentration at which agglutination is inhibited in μg/ml; none of the cloned antibodies showed HAI activity. Neutralization is reported as the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) in μg/ml. Most antibodies neutralize all tested strains similarly. For unknown reasons, the pseudovirus made from the H5N1 A/Indonesia/05/2005 strain used for vaccination in this study is not neutralized well by the antibodies tested, nor by the control antibody CR6261. 2D1 and 9E8 are head-specific monoclonal antibodies against H1 and H5, respectively (28, 36). Clonally related antibodies are indicated. (B) Genetic characteristics of further H1/H5 cross-reactive antibodies not expressed. id, identifier; nd, tests not performed; VK, variable kappa-chain gene; Vγ, variable lambda-chain gene.

Twenty-two representative antibodies were cloned, expressed, and tested for binding to H1 or H5 HA by ELISA. Most bound H1 and H5 HAs equivalently (Fig. 4A). We have previously described a modified HA, HAΔStem, that has been used to confirm the specificity of antibodies for binding to the same epitope as bnAbs F10 and CR6261 (21). None of the 22 antibodies tested bound HAΔStem, demonstrating that all bind at or near the highly conserved stem epitope. Also, as expected for stem-directed antibodies, none of the cloned antibodies have HAI activity (Fig. 4A). Genetic characteristics for the remaining antibodies are shown (Fig. 4B). The antibodies appear to be specific to group 1 influenza virus strains, because they do not bind HA of 1968 H3N2 influenza virus (data not shown). The antibodies were further tested for neutralizing activity against diverse H1 and H5 influenza virus strains using a pseudotyped lentiviral reporter assay (Fig. 4A). All 22 antibodies neutralized the pseudoviruses tested to a similar extent, demonstrating neutralizing breadth comparable to that of known stem-directed bnAbs. Although neutralization of viruses by antibody can occur through a variety of mechanisms, elicitation of nonneutralizing antibodies remains relevant to vaccine protection for both HIV and influenza virus (30). It is therefore arguably surprising that all the antibodies isolated here have activity in this pseudovirus neutralization assay. Since the probe only presents the stem structure of the pretriggered native HA trimer, not intermediate or postfusion versions of the stem, these results are consistent with the postulate that any antibody bound to the native trimer should have some level of neutralizing activity. However, as these results are limited to a single subject, further studies will be necessary to assess the frequency at which B cells expressing nonneutralizing antibodies are recovered using this method. We compared the affinities of these antibodies to reference stem-directed monoclonal antibody CR6261. Four representative antibodies were expressed as Fab fragments and tested against H1/1999 HA using an Octet Red384 system. They had affinities for HA (equilibrium dissociation constant [KD], 2 to 20 nM) that were similar to those of CR6261 (KD, 4 nM) (Tables 1 and 2).

TABLE 2.

Binding kinetics and affinity for representative H1/H5 cross-reactive antibodies

| Antibody | VH segment | KD (M) | kon (1/s · M) | koff (1/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 310-18A3 | 1-69 | 1.70 × 10−9 | 1.04 × 105 | 1.76 × 10−5 |

| 310-18D5 | 1-3 | 6.70 × 10−9 | 1.04 × 105 | 7.04 × 10−5 |

| 310-18F3 | 4-34 | 2.05 × 10−8 | 7.30 × 104 | 1.49 × 10−4 |

| 310-18F5 | 3-13 | 8.00 × 10−9 | 2.41 × 105 | 1.93 × 10−4 |

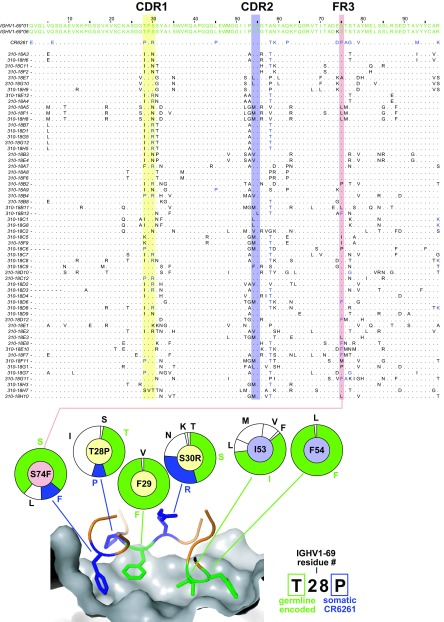

Previously, we defined the structural and genetic basis for maturation of IGHV1-69 influenza virus bnAbs (17). Notably, only maturation of the heavy chain is required and as few as 7 mutations are sufficient for full activity. Maturation of the CDR-H1 loop to stabilize a noncanonical conformation, preservation of phenylalanines 29 and 54, and the introduction of additional hydrophobic residues in FR3 were all shown to be important. A sequence alignment of the IGVH1-69 genes isolated illustrates that each of these mutations is common in this set of novel antibodies (Fig. 5). However, our data also demonstrate that use of the IGVH1-69 gene is not obligatory. The remaining antibodies derive from a variety of IGHV segments (IGHV1-3, IGHV1-8, IGHV3-11, IGHV3-23, IGHV3-30, IGHV3-33, and IGHV4-34). In this study, we report 77 sequences from a single subject. All antibodies tested displayed similar binding to HA and ability to neutralize virus and are stem directed.

FIG 5.

Sequences of novel IGHV1-69 cross-reactive antibodies are consistent with the structural basis for development of broadly neutralizing influenza virus antibodies. (A) Multiple sequence alignment of cloned IGHV1-69 VH gene segments compared to germ line alleles present in this subject, 1-69*01 and -*06 (green) and CR6261 (somatically mutated residues in blue). Residues conserved from the IGHV1-69-encoded protein are denoted by dots; somatically mutated residues in each antibody are denoted by black letters or, when congruent with CR6261, by blue letters. Shaded areas correspond to colors in panel B. (B) Structure of the HA stem epitope (gray surface) in complex with the VH portion of CR6261 (contact residues shown as colored sticks). The CDR-H3 also contributes two non-germ line-encoded contacts (not shown). Germ line-encoded residues are drawn in green; somatically mutated residues in blue. Pie charts represent the observed frequency of each amino acid at the residue indicated; the color of the center of each pie chart corresponds to the shading used in the sequence alignment in panel A; the wedges of each pie chart are colored green to denote the germ line residue, or blue to denote the residue found in CR6261, or white if other. The previously described structural basis for development of this class of antibody included strict conservation of F29 and F54, preference for hydrophobicity at F53, mutations at 28 and 30 that stabilize the bound conformation of the CDR-H1 (arginine [R] and the next most frequent residue, asparagine [N], are chemically similar) and, optionally, mutation of residue 74 to phenylalanine [F].

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrates that it is possible to analyze and isolate individual HA-specific B cells by flow cytometry with a structurally designed probe. Identification of HA-specific B cells by flow cytometry has been hampered by the fact that HA binds SA, a nearly ubiquitous surface component of eukaryotic cells. Using a point mutation chosen based on crystal structures of HA, we removed this activity yet preserved binding of antibodies targeting HA, including those that bind at the RBS. With this feature in place, we developed an assay to profile HA-specific B cells that target conserved regions of influenza virus vulnerability and in so doing identify the features needed for these antibodies to develop.

This approach has utility not only for the analysis of the immune response to influenza virus in animals and humans but also for the evaluation of influenza vaccines. With this approach, one can rapidly isolate B cells expressing monoclonal antibodies specific to HA from a given strain of influenza virus, or to two or more distinct influenza virus strains, in order to profile HA-specific B cells that target conserved regions of vulnerability. This analysis enabled us also to deduce the pathway of antibody development underpinning a cross-reactive response and thereby evaluate the immunogenicity of a vaccine platform. Our results indicate that both IGHV1-69 and non-IGHV1-69 stem-directed responses can be elicited by vaccination and have similar neutralization potency. We also report that the recently described HA-ferritin nanoparticles (22) agglutinate red blood cells and therefore may be useful for HAI immunoassays where live virus is not readily available.

Analysis of PBMCs obtained from a phase I influenza vaccine trial revealed that HAΔSA probes were highly specific for B cells that bind wild-type HA and that antibodies cloned from H1/H5 cross-reactive B cells identified using HAΔSA probes were largely stem directed and broadly neutralizing. While initially it was thought that stem-directed bnAbs are exceedingly rare, others have since demonstrated that infection with 2009 pandemic H1N1 frequently triggered stem-reactive antibodies (31–33), and stem-directed antibodies are prevalent in human serum samples (34, 35). Our results now suggest that H5N1 vaccination also initiates expansion of B cells expressing stem-directed bnAbs.

Every one of the antibodies tested bound the epitope that was the same as (or similar to) that of bnAbs F10 and CR6261, because none bound a variant of HA in which that epitope is blocked by an artificially introduced glycosylation, HAΔStem (21). However, we note two distinct modes of elicitation: IGHV1-69-dependent and IGHV1-69-independent pathways of antibody development. IGHV1-69-derived antibodies represented the dominant mode of elicitation, accounting for 77% of stem-reactive antibodies in this subject. In the published reports of HA stem-directed bnAbs (2, 7, 9–12), there are a total of 52 antibodies reported, 43 (82%) of which are IGHV1-69. Indeed, we have shown recently that specific engagement of HA stem epitope by germ line IGHV1-69 directs affinity maturation toward stem-directed, broad neutralization activity (17). Furthermore, the IGHV1-69 bnAbs elicited by vaccination in the present study bear the hallmarks that we previously defined as obligate for achieving full neutralization activity (17): maturation of the CDR-H1 leading to stabilization of that loop in a noncanonical conformation, preservation of phenylalanines 29 and 54, and the introduction of additional hydrophobic residues in FR3 (Fig. 5). Our data allow us to refine our knowledge of these characteristics. In contrast to what is seen in previously known IGHV1-69 lineage stem antibodies, in this subject, mutation of residue 74 to leucine is observed as frequently as mutation to phenylalanine; residue 28, proline in CR6261, mutates more commonly to isoleucine; at position 30, mutation to arginine, observed for CR6261, is the most common mutation, but asparagine is also often seen.

Our previous paper raised the concern that the stem-directed response may be limited by human genetic polymorphism at the IGHV1-69 locus (17). Genomically encoded Phe54 is critical for engagement of the HA stem epitope by germ line IGHV1-69 (12). However, approximately one in 10 persons are homozygous for a single nucleotide polymorphism that replaces Phe54 with Leu54, which eliminates the capacity of germ line IGHV1-69 to bind the HA stem (12). Thus, the question of whether or not effective non-IGHV1-69 stem responses can be elicited by vaccination remained an outstanding issue. Our analysis now indicates that a diminished IGHV1-69 response would not by itself impede elicitation of broadly neutralizing stem-reactive antibodies by vaccination. The non-IGHV1-69 antibodies we recovered are diverse in sequence but had neutralizing activity similar to that of IGHV1-69 antibodies. These antibodies derive from a variety of IGHV segments, some previously seen among stem-directed antibodies (IGHV3-23, -3-30, and -1-8) and others that are novel (IGHV1-3, -3-11, -3-33, and -4-34). This result confirms the important observation made previously that stem-directed MAbs are not exclusively of IGHV1-69 origin (3, 11) and further suggests that the repertoire of such stem MAbs is more diverse than previously known. While no conserved modes of IGHV1-69-independent HA recognition emerge from the current data set, we speculate that specific strategies may exist. Along these lines, the three IGVH4-34 antibodies isolated are clonally related, have low heavy-chain variable (VH) maturation (<3%), and have an unusually long CDR-H3 of 28 residues; hence for this antibody family, interaction of the germ line precursor with antigen likely depends on the CDR-H3. Though the stem epitope recognized by IGVH1-69 antibodies is compact (342 Å2 for CR6261), it is unlikely that heavy-chain only interaction is the mode of access favored by other antibody lineages, and one should expect to see such CDR-H3 dependent modes. The existence of alternative developmental pathways to stem-directed neutralizing antibodies is reassuring for those who aim to design vaccines to elicit universal coverage. The non-IGHV1-69 antibodies cloned here have neutralizing activity similar to that of their IGHV1-69 counterparts. Further studies using samples from the VRC 310 trial will be directed toward identifying genetic commonalities across patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of the VRC 310 Study Team and the participation of study volunteers.

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Vaccine Research Center, NIAID, National Institutes of Health.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding agency.

We declare that an intellectual property application has been filed by NIH based on data presented in this paper.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 5 February 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Ekiert DC, Bhabha G, Elsliger MA, Friesen RH, Jongeneelen M, Throsby M, Goudsmit J, Wilson IA. 2009. Antibody recognition of a highly conserved influenza virus epitope. Science 324:246–251. 10.1126/science.1171491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sui J, Hwang WC, Perez S, Wei G, Aird D, Chen LM, Santelli E, Stec B, Cadwell G, Ali M, Wan H, Murakami A, Yammanuru A, Han T, Cox NJ, Bankston LA, Donis RO, Liddington RC, Marasco WA. 2009. Structural and functional bases for broad-spectrum neutralization of avian and human influenza A viruses. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16:265–273. 10.1038/nsmb.1566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corti D, Voss J, Gamblin SJ, Codoni G, Macagno A, Jarrossay D, Vachieri SG, Pinna D, Minola A, Vanzetta F, Silacci C, Fernandez-Rodriguez BM, Agatic G, Bianchi S, Giacchetto-Sasselli I, Calder L, Sallusto F, Collins P, Haire LF, Temperton N, Langedijk JP, Skehel JJ, Lanzavecchia A. 2011. A neutralizing antibody selected from plasma cells that binds to group 1 and group 2 influenza A hemagglutinins. Science 333:850–856. 10.1126/science.1205669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ekiert DC, Friesen RH, Bhabha G, Kwaks T, Jongeneelen M, Yu W, Ophorst C, Cox F, Korse HJ, Brandenburg B, Vogels R, Brakenhoff JP, Kompier R, Koldijk MH, Cornelissen LA, Poon LL, Peiris M, Koudstaal W, Wilson IA, Goudsmit J. 2011. A highly conserved neutralizing epitope on group 2 influenza A viruses. Science 333:843–850. 10.1126/science.1204839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whittle JR, Zhang R, Khurana S, King LR, Manischewitz J, Golding H, Dormitzer PR, Haynes BF, Walter EB, Moody MA, Kepler TB, Liao HX, Harrison SC. 2011. Broadly neutralizing human antibody that recognizes the receptor-binding pocket of influenza virus hemagglutinin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:14216–14221. 10.1073/pnas.1111497108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dreyfus C, Laursen NS, Kwaks T, Zuijdgeest D, Khayat R, Ekiert DC, Lee JH, Metlagel Z, Bujny MV, Jongeneelen M, van der Vlugt R, Lamrani M, Korse HJ, Geelen E, Sahin O, Sieuwerts M, Brakenhoff JP, Vogels R, Li OT, Poon LL, Peiris M, Koudstaal W, Ward AB, Wilson IA, Goudsmit J, Friesen RH. 2012. Highly conserved protective epitopes on influenza B viruses. Science 337:1343–1348. 10.1126/science.1222908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Throsby M, van den Brink E, Jongeneelen M, Poon LL, Alard P, Cornelissen L, Bakker A, Cox F, van Deventer E, Guan Y, Cinatl J, ter Meulen J, Lasters I, Carsetti R, Peiris M, de Kruif J, Goudsmit J. 2008. Heterosubtypic neutralizing monoclonal antibodies cross-protective against H5N1 and H1N1 recovered from human IgM+ memory B cells. PLoS One 3:e3942. 10.1371/journal.pone.0003942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friesen RH, Koudstaal W, Koldijk MH, Weverling GJ, Brakenhoff JP, Lenting PJ, Stittelaar KJ, Osterhaus AD, Kompier R, Goudsmit J. 2010. New class of monoclonal antibodies against severe influenza: prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy in ferrets. PLoS One 5:e9106. 10.1371/journal.pone.0009106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corti D, Suguitan AL, Jr, Pinna D, Silacci C, Fernandez-Rodriguez BM, Vanzetta F, Santos C, Luke CJ, Torres-Velez FJ, Temperton NJ, Weiss RA, Sallusto F, Subbarao K, Lanzavecchia A. 2010. Heterosubtypic neutralizing antibodies are produced by individuals immunized with a seasonal influenza vaccine. J. Clin. Invest. 120:1663–1673. 10.1172/JCI41902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wrammert J, Koutsonanos D, Li GM, Edupuganti S, Sui J, Morrissey M, McCausland M, Skountzou I, Hornig M, Lipkin WI, Mehta A, Razavi B, Del Rio C, Zheng NY, Lee JH, Huang M, Ali Z, Kaur K, Andrews S, Amara RR, Wang Y, Das SR, O'Donnell CD, Yewdell JW, Subbarao K, Marasco WA, Mulligan MJ, Compans R, Ahmed R, Wilson PC. 2011. Broadly cross-reactive antibodies dominate the human B cell response against 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus infection. J. Exp. Med. 208:181–193. 10.1084/jem.20101352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li GM, Chiu C, Wrammert J, McCausland M, Andrews SF, Zheng NY, Lee JH, Huang M, Qu X, Edupuganti S, Mulligan M, Das SR, Yewdell JW, Mehta AK, Wilson PC, Ahmed R. 2012. Pandemic H1N1 influenza vaccine induces a recall response in humans that favors broadly cross-reactive memory B cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:9047–9052. 10.1073/pnas.1118979109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomson CA, Wang Y, Jackson LM, Olson M, Wang W, Liavonchanka A, Keleta L, Silva V, Diederich S, Jones RB, Gubbay J, Pasick J, Petric M, Jean F, Allen VG, Brown EG, Rini JM, Schrader JW. 2012. Pandemic H1N1 influenza infection and vaccination in humans induces cross-protective antibodies that target the hemagglutinin stem. Front. Immunol. 3:87. 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doucett VP, Gerhard W, Owler K, Curry D, Brown L, Baumgarth N. 2005. Enumeration and characterization of virus-specific B cells by multicolor flow cytometry. J. Immunol. Methods 303:40–52. 10.1016/j.jim.2005.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. 2000. Receptor binding and membrane fusion in virus entry: the influenza hemagglutinin. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:531–569. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alberts B, Bray D, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Watson J. 1994. Molecular biology of the cell, 3rd ed. Garland Science, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ledgerwood J, Zephir K, Hu Z, Wei C-J, Chang L, Enama M, Hendel C, Sitar S, Bailer R, Koup R, Mascola J, Nabel G, Graham B, VRC 310 Study Team 2013. Prime-boost interval matters: A randomized phase I study to identify the minimum interval necessary to observe the h5 DNA influenza vaccine priming effect. J. Infect. Dis. 208:418–422. 10.1093/infdis/jit180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lingwood D, McTamney PM, Yassine HM, Whittle JR, Guo X, Boyington JC, Wei CJ, Nabel GJ. 2012. Structural and genetic basis for development of broadly neutralizing influenza antibodies. Nature 489:566–570. 10.1038/nature11371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tiller T, Meffre E, Yurasov S, Tsuiji M, Nussenzweig MC, Wardemann H. 2008. Efficient generation of monoclonal antibodies from single human B cells by single cell RT-PCR and expression vector cloning. J. Immunol. Methods 329:112–124. 10.1016/j.jim.2007.09.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brochet X, Lefranc MP, Giudicelli V. 2008. IMGT/V-QUEST: the highly customized and integrated system for IG and TR standardized V-J and V-D-J sequence analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 36:W503–W508. 10.1093/nar/gkn316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giudicelli V, Brochet X, Lefranc MP. 2011. IMGT/V-QUEST: IMGT standardized analysis of the immunoglobulin (IG) and T cell receptor (TR) nucleotide sequences. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2011:695–715. 10.1101/pdb.prot5633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei CJ, Boyington JC, Dai K, Houser KV, Pearce MB, Kong WP, Yang ZY, Tumpey TM, Nabel GJ. 2010. Cross-neutralization of 1918 and 2009 influenza viruses: role of glycans in viral evolution and vaccine design. Sci. Transl. Med. 2:24ra21. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanekiyo M, Wei C-J, Yassine HM, McTamney PM, Boyington JC, Whittle JRR, Rao SS, Kong W-P, Wang L, Nabel GJ. 2013. Self-assembling influenza nanoparticle vaccines elicit broadly neutralizing H1N1 antibodies. Nature 499:102–106. 10.1038/nature12202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joyce MG, Kanekiyo M, Xu L, Biertumpfel C, Boyington JC, Moquin S, Shi W, Wu X, Yang Y, Yang ZY, Zhang B, Zheng A, Zhou T, Zhu J, Mascola JR, Kwong PD, Nabel GJ. 2013. Outer domain of HIV-1 gp120: Antigenic optimization, structural malleability, and crystal structure with antibody VRC-PG04. J. Virol. 87:2294–2306. 10.1128/JVI.02717-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin J, Wharton SA, Lin YP, Takemoto DK, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC, Steinhauer DA. 1998. Studies of the binding properties of influenza hemagglutinin receptor-site mutants. Virology 241:101–111. 10.1006/viro.1997.8958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bradley KC, Galloway SE, Lasanajak Y, Song X, Heimburg-Molinaro J, Yu H, Chen X, Talekar GR, Smith DF, Cummings RD, Steinhauer DA. 2011. Analysis of influenza virus hemagglutinin receptor binding mutants with limited receptor recognition properties and conditional replication characteristics. J. Virol. 85:12387–12398. 10.1128/JVI.05570-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gamblin SJ, Haire LF, Russell RJ, Stevens DJ, Xiao B, Ha Y, Vasisht N, Steinhauer DA, Daniels RS, Elliot A, Wiley DC, Skehel JJ. 2004. The structure and receptor binding properties of the 1918 influenza hemagglutinin. Science 303:1838–1842. 10.1126/science.1093155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ekiert DC, Kashyap AK, Steel J, Rubrum A, Bhabha G, Khayat R, Lee JH, Dillon MA, O'Neil RE, Faynboym AM, Horowitz M, Horowitz L, Ward AB, Palese P, Webby R, Lerner RA, Bhatt RR, Wilson IA. 2012. Cross-neutralization of influenza A viruses mediated by a single antibody loop. Nature 489:526–532. 10.1038/nature11414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang ZY, Wei CJ, Kong WP, Wu L, Xu L, Smith DF, Nabel GJ. 2007. Immunization by avian H5 influenza hemagglutinin mutants with altered receptor binding specificity. Science 317:825–828. 10.1126/science.1135165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ledgerwood JE, Wei CJ, Hu Z, Gordon IJ, Enama ME, Hendel CS, McTamney PM, Pearce MB, Yassine HM, Boyington JC, Bailer R, Tumpey TM, Koup RA, Mascola JR, Nabel GJ, Graham BS. 2011. DNA priming and influenza vaccine immunogenicity: two phase 1 open label randomised clinical trials. Lancet Infect. Dis. 11:916–924. 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70240-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reading SA, Dimmock NJ. 2007. Neutralization of animal virus infectivity by antibody. Arch. Virol. 152:1047–1059. 10.1007/s00705-006-0923-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palese P, Wang TT. 2011. Why do influenza virus subtypes die out? A hypothesis. mBio 2(5):e00150–11. 10.1128/mBio.00150-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krammer F, Pica N, Hai R, Tan GS, Palese P. 2012. Hemagglutinin stalk-reactive antibodies are boosted following sequential infection with seasonal and pandemic H1N1 influenza virus in mice. J. Virol. 86:10302–10307. 10.1128/JVI.01336-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pica N, Hai R, Krammer F, Wang TT, Maamary J, Eggink D, Tan GS, Krause JC, Moran T, Stein CR, Banach D, Wrammert J, Belshe RB, Garcia-Sastre A, Palese P. 2012. Hemagglutinin stalk antibodies elicited by the 2009 pandemic influenza virus as a mechanism for the extinction of seasonal H1N1 viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:2573–2578. 10.1073/pnas.1200039109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sui J, Sheehan J, Hwang WC, Bankston LA, Burchett SK, Huang CY, Liddington RC, Beigel JH, Marasco WA. 2011. Wide prevalence of heterosubtypic broadly neutralizing human anti-influenza A antibodies. Clin. Infect. Dis. 52:1003–1009. 10.1093/cid/cir121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller MS, Tsibane T, Krammer F, Hai R, Rahmat S, Basler CF, Palese P. 2013. 1976 and 2009 H1N1 influenza virus vaccines boost anti-hemagglutinin stalk antibodies in humans. J. Infect. Dis. 207:98–105. 10.1093/infdis/jis652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu R, Ekiert DC, Krause JC, Hai R, Crowe JE, Jr, Wilson IA. 2010. Structural basis of preexisting immunity to the 2009 H1N1 pandemic influenza virus. Science 328:357–360. 10.1126/science.1186430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]