ABSTRACT

The impact of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) on human health is substantial, but vaccines that prevent primary EBV infections or treat EBV-associated diseases are not yet available. The Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA-1) is an important target for vaccination because it is the only protein expressed in all EBV-associated malignancies. We have designed and tested two therapeutic EBV vaccines that target the rhesus (rh) lymphocryptovirus (LCV) EBNA-1 to determine if ongoing T cell responses during persistent rhLCV infection in rhesus macaques can be expanded upon vaccination. Vaccines were based on two serotypes of E1-deleted simian adenovirus and were administered in a prime-boost regimen. To further modulate the response, rhEBNA-1 was fused to herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D (HSV-gD), which acts to block an inhibitory signaling pathway during T cell activation. We found that vaccines expressing rhEBNA-1 with or without functional HSV-gD led to expansion of rhEBNA-1-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cells in 33% and 83% of the vaccinated animals, respectively. Additional animals developed significant changes within T cell subsets without changes in total numbers. Vaccination did not increase T cell responses to rhBZLF-1, an immediate early lytic phase antigen of rhLCV, thus indicating that increases of rhEBNA-1-specific responses were a direct result of vaccination. Vaccine-induced rhEBNA-1-specific T cells were highly functional and produced various combinations of cytokines as well as the cytolytic molecule granzyme B. These results serve as an important proof of principle that functional EBNA-1-specific T cells can be expanded by vaccination.

IMPORTANCE EBV is a common human pathogen that establishes a persistent infection through latency in B cells, where it occasionally reactivates. EBV infection is typically benign and is well controlled by the host adaptive immune system; however, it is considered carcinogenic due to its strong association with lymphoid and epithelial cell malignancies. Latent EBNA-1 is a promising target for a therapeutic vaccine, as it is the only antigen expressed in all EBV-associated malignancies. The goal was to determine if rhEBNA-1-specific T cells could be expanded upon vaccination of infected animals. Results were obtained with vaccines that target EBNA-1 of rhLCV, a virus closely related to EBV. We found that vaccination led to expansion of rhEBNA-1 immune cells that exhibited functions fit for controlling viral infection. This confirms that rhEBNA-1 is a suitable target for therapeutic vaccines. Future work should aim to generate more-robust T cell responses through modified vaccines.

INTRODUCTION

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), a gamma-1 herpesvirus also called human herpesvirus 4, is a common human pathogen that infects more than 95% of humans once they reach adulthood (1). Although primary infections are in general benign, EBV establishes persistent infection through its latency in B cells, where it occasionally reactivates. This can lead to EBV-associated malignancies in certain populations (2). For example, when the immune system becomes compromised, as it does during infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or immunosuppression following organ transplant, its ability to control EBV declines, and EBV-associated malignancies can arise (2). In Southern China, EBV-associated nasopharyngeal carcinoma afflicts 0.05% of all males over the age of 50 (3). EBV-associated gastric carcinomas are highly prevalent in Eastern Asia, Eastern Europe, and Africa (4), and EBV is tightly linked to endemic forms of Burkitt's lymphoma in Central Africa (5). Overall, EBV is associated with about 200,000 new cases of cancer annually and around 1% of all human cancers worldwide (4, 6). EBV has also been linked to autoimmune disorder (7). The impact of EBV on human health is thus substantial, but vaccines to prevent primary EBV infections or treat EBV-associated diseases are not yet available.

An effective therapeutic EBV vaccine would need to target antigens produced during latency, when most viral protein expression is downregulated (8). Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA-1) functions to maintain the viral episome and is essential for viral DNA replication during latency. It is the only antigen expressed during all forms of latency (9) and in all EBV-associated malignancies (10). EBNA-1 is thus a primary target for a therapeutic EBV vaccine. Like many antigens of herpesviruses, EBNA-1 subverts CD8+ T cell responses, thus potentially enhancing the virus's ability to persist and escape immune surveillance. EBNA-1 mRNA contains a purine-rich domain that encodes a large glycine-alanine repeat (GAr) sequence that can interfere with EBNA-1-specific CD8+ T cell responses, either by direct inhibition of GAr-containing protein synthesis or proteasome-mediated degradation, thus leading to reduced antigen presentation (11–13). As a result, induction and effector functions of EBNA-1-specific CD8+ T cell responses are impaired. Nevertheless, EBNA-1 specific CD8+ (14, 15) and CD4+ (16) T cells are frequently detected in EBV-infected humans. These T cells are capable of controlling EBV-infected cells in vitro (17, 18), and the loss of EBNA-1-specific T cells has been correlated with numerous EBV-associated diseases (19–22); this suggests that EBNA-1-specific T cells play an important role in controlling infections in vivo.

We designed and tested vaccines that target the rhesus (rh) lymphocryptovirus (LCV) EBNA-1. Rhesus macaques are naturally infected with rhLCV, a gamma-1 herpesvirus that is closely related to EBV (23, 24). Most rhesus macaques become infected during infancy, and rhLCV persists for life in a latent form in B cells. Like EBV, rhLCV has been associated with virus-positive B cell lymphomas upon immunosuppression (24). EBV and rhLCV share a high degree of sequence homology, they have identical repertoires of lytic and latent genes (25), and they elicit similar immune responses (26). The rhLCV model is therefore ideal for preclinical testing of EBV vaccines.

The goal of this study was to test if prototype vaccines expressing rhEBNA-1 could expand ongoing CD8+ and CD4+ rhEBNA-1-specific T cell responses in adult rhesus macaques with persistent rhLCV infections. We developed and tested two vaccine regimens based on replication-defective adenovirus (Ad) vectors derived from chimpanzee serotypes (AdC). Vaccines expressed a GAr-deleted form of rhEBNA-1. To further modulate the response, rhEBNA-1 was fused to herpes simplex virus (HSV) glycoprotein D (gD), which binds the herpesvirus entry mediator (HVEM) and blocks its interaction with the immunoinhibitory B and T lymphocyte attenuator (BTLA) during T cell activation. HVEM-binding and -nonbinding versions of HSV-gD were tested. Vaccination increased the number of circulating rhEBNA-1-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cells in rhesus macaques with persistent rhLCV infections regardless of gD binding ability. Responses were highly functional, and T cells produced various combinations of the cytokines gamma interferon (IFN-γ), interleukin-2 (IL-2), and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α). T cells also produced granzyme B, which indicates that vaccination increased the cytolytic potential of rhEBNA-1-specific T cells. These preliminary studies confirm that rhEBNA-1 is a suitable target for therapeutic rhLCV and presumably EBV vaccines.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Vaccine vectors.

The rhEBNA-1 gene was deleted from the GAr domain, and a Flag epitope was inserted as described previously (27). Start and stop codons were also removed, and the final gene product was amplified by PCR with the following primers: Fw, 5′-ACCGGTAGGGAGGGTGGTTTGGGAGG-3′, and Rv, 5′-ACGCGTCGACCTCCTGCCCCGCCGCGTCGAC −3′. Primers were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). DNA fragments were cloned into the ApaI site of the pRE4 vector as described previously (28). The correct in-frame cloning of the rhEBNA-1-encoding gene was confirmed by restriction enzyme digestion followed by visualization of bands by gel electrophoresis and DNA sequencing. To generate pSh-SgD-rhEBNA-1 and pSh-NBEFSgD-rhEBNA-1 vectors, the GAr-deleted rhEBNA-1 gene was ligated into pShuttle vectors containing sequences encoding the previously described (29) mutated versions of HSV-1 gD, which showed either increased (SgD) or reduced (NBEFSgD) binding to HVEM (28). Transgenes were under the control of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) enhancer and promoter. Restriction enzyme digests followed by gel electrophoresis and nucleotide sequencing confirmed correct insertion of the rhEBNA-1 sequences into pShuttle.

We then cloned the inserts including the regulatory elements from the pShuttle vectors into the E1 domain of molecular clones of E1-deleted AdC vectors of simian serotype 25 (SAdV-25) and serotype 23 (SAdV-23), used for primary and booster immunizations, respectively. Vectors based on these serotypes are from here on referred to as AdC68 (SAdV-25) and AdC6 (SAdV-23) vectors.

Recombinant AdC vectors were rescued and propagated on HEK 293 cells as described previously (30). Virus was purified and titrated as previously described (30). Vector batches were quality controlled by determining virus particle (vp) to infectious unit (multiplicity of infection [MOI]) ratios. They were tested for replication-competent Ad and endotoxin contaminations. The genetic integrity of AdC vectors was determined by restriction enzyme digestion of purified viral DNA. AdC-gDNP and AdC-gD vectors have been described previously (29, 31).

Immunoblotting.

Expression of the different forms of rhEBNA-1 from recombinant AdC vectors was confirmed upon infection of CHO cells stably transfected to express the coxsackie adenovirus receptor (CAR) by Western blot analysis. An AdC68 vector expressing gD was used as a control vector. Briefly, CHO-CAR cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FBS), 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 1% pyruvate, and 1% nonessential amino acids at 37°C in 5% CO2 until they reached 80% confluence in wells of a 6-well plate. Medium was then replaced with 1 ml of serum-free DMEM, and about 106 cells were infected with 1010, 109, or 108 vps of vector per well. After 2 h, 1 ml complete DMEM was added to each well, and cells were harvested after 48 h.

Total cellular protein was prepared by washing cells 2 times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). They were then suspended in RIPA buffer (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with complete protease inhibitor (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Cells were transferred to a new tube and incubated for 1 h on ice. Tubes were spun for 30 min at 4°C to pellet debris, and lysate was transferred to new tubes. Ten microliters of lysate was mixed with 10 μl of 2× loading buffer (Laemmli blue dye, 2-mercaptoethanol) and boiled for 5 min. Protein samples were then separated with 4 to 15% gradient sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and proteins were transferred to a 0.45-μm polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) transfer membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature in 5% fat-free milk dissolved in PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20. After washing, expression of chimeric rhEBNA-1 proteins was detected with a mouse monoclonal antibody specific for the Flag epitope (M2; Sigma, St. Louis, MO), diluted 1:1,000 in 5% milk, PBS, and 0.1% Tween 20 and incubated at 4°C overnight. Blots were then washed, incubated for 1 h with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (1:30,000; KPL), and developed with Super Signal West Pico chemiluminescence substrate (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Membranes were washed extensively between all steps. Membranes were treated with stripping buffer (Thermo Scientific) for 15 min, washed in PBS-Tween (PBST), blocked, and reprobed as described above. To detect gD, membranes were probed with a polyclonal anti-gD serum R6 (R45) diluted 1:500. Donkey anti-rabbit IgG HRP (Amersham Biosciences, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) was used as a secondary antibody at 1:10,000. For loading control, we stripped and reprobed with a 1:20,000 dilution of a β-actin-specific antibody (AC-15; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and then with 1:30,000 goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP as described above.

Immunofluorescence.

Expression of transgene products by AdC vectors was further measured by immunofluorescence. Cells (106) were infected as described above with 1010 or 109 vps of vector and washed. PBS (1 ml) supplemented with 10 mM EDTA was added to each well, and cells were incubated at 37°C for 5 min. Cells were harvested, washed, and transferred to a 96-well plate, where they were stained with mouse anti-Flag antibody for 30 min, washed, and probed with goat anti-mouse IgG-Alexa Fluor 700 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Cells were washed twice more, fixed with BD stabilizing fixative (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and then analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) using LSRII (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and DiVa software.

HVEM binding assay.

CHO-CAR cells (106) were infected with 1010 vps of AdC vectors as described above. After 48 h, cells were harvested and total cellular protein was prepared as described above. Protein extracts were kept at −80°C until use. Western blotting and densitometry (AlphaEaseFC software version 3.3.0; Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA) were used to normalize the amount of chimeric protein in the extracts.

To measure the gD fusion proteins' ability to bind HVEM, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plates were coated with 50 μl per well of a 5-μg/ml concentration of HVEM (29) diluted in 0.1 M carbonate coating buffer (pH 9.6) and incubated overnight at 4°C. Plates were washed 5 times and then blocked for 1.5 h in 5% milk-PBS-0.05% Tween 20 at room temperature. After washing, normalized protein extract was serially diluted in blocking solution and added to the plates for 1.5 h. To detect captured chimeric protein, 50 μl mouse anti-Flag antibody diluted 1:1,000 in 5% milk-PBST was added for 1 h, followed by 50 μl goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP diluted 1:1,000 for 30 min with washings after each step. A TMB (3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine) substrate solution (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) was then added to each well, plates were stored in the dark for 15 min, and the reaction was stopped by adding 2 N HCl. The optical density at 450 nm was determined using a microtiter plate reader.

In vitro stimulation.

Dendritic cells (DCs) were generated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of an rhLCV-seropositive rhesus macaque by culturing in the presence of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and IL-4 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). They were subsequently matured in the presence of monocyte-conditioned medium as previously described (32). Matured DCs were infected with recombinant AdC vectors at an MOI of 50 per cell and cultured overnight. Effector CD8+ T cells were generated by stimulating PBMCs from the same animal with an rhEBNA-1 peptide pool followed by depletion of CD4+ T cells as described previously (33). Twenty thousand AdC vector- or rhEBNA-1 peptide-pulsed DCs were used as antigen-presenting cells (APCs) in the presence or absence of 50,000 CD8+ T cells in an IFN-γ enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay. After 16 h of incubation, IFN-γ-secreting cells were visualized following the manufacturer's instructions (Mabtech, Cincinnati, OH) as described previously (33). The activated CD8+ T cells were enumerated by counting the number of spots using an automated reader and analysis software (Zellnet, Fort Lee, NJ), and the results were expressed as the number of spot-forming cells per 106 CD8+ T cells. Positive and negative controls were CD8+ T cells cultured in the presence of phytohemagglutinin (PHA) or medium alone.

Microneutralization assay for Ad-specific NAs.

Neutralizing antibody (NA) titers were determined as described previously (34) on HEK 293 cells infected with AdC vectors expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP).

Nonhuman primates.

Fifteen female adult, healthy, and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-uninfected macaques (Macaca mulatta) of Indian origin aged 6 to 20 years were enrolled into the study. Animals were housed at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center (YNPRC, Atlanta, GA) at either the field station or the main station. All animals except PH1019 and PWw were born at YNPRC. Animals were negative for NAs to AdC68 and AdC6, except for one animal (RZi7) with a low titer (1:10) to AdC6. All animals tested positive for rhLCV infection by serologic testing for serum antibodies against the rhLCV small viral capsid antigen (35). Mamu phenotypes were also determined. A detailed analysis of baseline rhEBNA-1- and rhBZLF-1-specific immune responses was conducted and is discussed elsewhere (26).

Additional samples were obtained from five rhLCV-seronegative rhesus macaques housed in the extended specific-pathogen-free colony at the New England Primate Research Center, Harvard Medical School, Southborough, MA.

All procedures involving handling of animals were performed according to approved protocols and upon review by the respective Institutional Animal Care and Usage Committees.

Immunization regimen of rhesus macaques.

Fifteen animals were divided into 3 groups with similar age distribution and rhEBNA-1 immune response status. Group 1 animals (n = 6) received 1011 vps of AdC68-SgD-rhEBNA-1, group 2 animals (n = 6) received 1011 vps of AdC68-NBEFSgD-rhEBNA-1, and group 3 animals (n = 3) received 1011 vps of an AdC68 vector expressing an irrelevant antigen (i.e., nucleoprotein of influenza A virus) fused into gD (AdC68-gDNP). Animals were boosted 15 weeks after priming with 1011 vps of the corresponding AdC6 vectors expressing the same antigens used for priming. All vaccines were given intramuscularly (i.m.). See Table 3 for the basic characteristics of the animals enrolled in the study and the vaccines that they received.

TABLE 3.

Characteristics and responsiveness of rhesus macaques enrolled in this studya

| Group | NHP ID | Age (yr) | MHC alleles | Response to vaccination |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD8 | CD4 | ||||

| Group 1 (SgD-rhEBNA-1) | Rya-6 | 12 | A.04, A.25 | R | R |

| B.01, B.17 | |||||

| PH1019 | 10 | A.08, A.18b | R | R | |

| B.17, B.83 | |||||

| RTn-5 | 15 | A.01, A.08 | NR | R | |

| B.12b, B47 | |||||

| RQt-5 | 13 | A.04, A.12 | NR | R | |

| B.43a | |||||

| RRi-9 | 7 | A.03, A.04 | NR | R | |

| B.01, B.12b | |||||

| RLy-9 | 6 | A.04 | NR | NR | |

| B.28b, B.47 | |||||

| Group 2 (NBEFSgD-rhEBNA-1) | RNw-9 | 6 | A.04, A.08 | R | R |

| B.12b, B.15a | |||||

| RZI-7 | 9 | A.01, A.07/19 | R | R | |

| B.17, B.55, B.69a | |||||

| RVw-6 | 10 | A.01, A.08 | R | R | |

| B.01, B.02 | |||||

| RTp-4 | 15 | A.04 | R | R | |

| B.12b, B.28b | |||||

| PWw | 13 | A.02, A.08 | NR | R | |

| B.12b, B.28b | |||||

| RCv-5 | 13 | A.04 | NR | R | |

| B.02, B.12b | |||||

| Group 3 (gD-NP) | Ryc-3 | 19 | A.01, A.03 | NR | NR |

| B.12b, B.47 | |||||

| RCj-7 | 9 | A.07, A.224 | NR | NR | |

| B.15a, B.23 | |||||

| RLz-5 | 12 | A.04 | NR | NR | |

| B.12b, B.69a | |||||

Abbreviations: R, responders; NR, nonresponders; NHP, nonhuman primate; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; ID, identification number.

Isolation and preservation of lymphocytes.

PBMCs were isolated from blood as described previously (26). They were tested immediately after isolation or frozen in 90% FBS and 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at −80°C until testing.

ICS.

The magnitude and function of rhEBNA-1- and rhBZLF-1-specific T cells were assessed by intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) after stimulation with peptide pools (26). Samples collected at different time points were tested in parallel for each animal to minimize variability. RhEBNA-1 was used at a final concentration of 2 μg of each peptide per ml, and rhBZLF1 was used at a final concentration of 1 μg of each peptide per ml. Frozen cells were thawed and immediately washed with Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) supplemented with 2 units/ml DNase I, resuspended with RPMI medium, and stimulated for 6 h with anti-CD28 (clone CD28.2), anti-CD49d (clone 9F10), and brefeldin A. Cells were stained with violet-fluorescent reactive dye-Pacific Blue (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), anti-CD14-Pacific Blue (clone M5E2), anti-CD16-Pacific Blue (clone 3G8), anti-CD8-APC-H7 (clone SK1), anti-CD4-Alexa Fluor 700 (clone OKT4), anti-CD95-PE-Cy5 (clone DX2), and anti-CD28-Texas Red (clone CD28.2, Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) for 30 min at 4°C. Additionally, cells were stained with anti-CCR7-PE (clone 150503). After fixation and permeabilization with Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) for 30 min at 4°C, cells were stained with anti-IFN-γ-APC (clone B27), anti-IL-2-fluorescein isothiocyanate (-FITC) (clone MQ1-17H12), anti-TNF-α-PE-Cy7 (clone MAb11, R&D System), and anti-CD3-PerCp-Cy5.5 (clone SP34-2) for 30 min at 4°C. Cells were washed twice, fixed with BD stabilizing fixative (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and then analyzed by FACS using LSRII (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and DiVA software. Flow cytometric acquisition and analysis of samples were performed on at least 500,000 events. Postacquisition analyses were performed with FlowJo (TreeStar, Ashland, OR). Data shown on graphs represent values of peptide-stimulated cells from which background values have been subtracted. Polyfunctionality pie chart graphs were generated using SPICE software (NIH, Bethesda, MD; http://exon.niaid.nih.gov/spice/). Single-color controls used CompBeads anti-mouse Igk (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) for compensation. Unless otherwise noted, antibodies were purchased from BD (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

The above-described experiment was repeated in 6 of the animals with the addition of an antibody for staining of intracellular granzyme B. Anti-granzyme B PE-Cy5.5 (clone GB11; Life Science Products, Chestertown, MD) was added after the fixation and permeabilization steps. Responses were tested at weeks 0, 2, 8, and either week 17 or week 19 after vaccination.

Synthetic peptides.

The rhEBNA1 peptide pool consists of 85 15-mer peptides overlapping by 10 amino acids except for the GAr domain, where peptides overlap by 5 amino acids (Genemed Synthesis Inc., San Antonio, TX; NeoBioSci, Cambridge, MA). The peptide pools used for testing of prevaccination samples contained peptides to the GAr domain, and we continued to use these pools although the vaccine does not carry these sequences of rhEBNA-1. To account for its large size, the rhEBNA-1 peptide pool was divided into two pools, one with peptides 1 to 42 and the other with peptides 43 to 85; responses were combined after normalization and subtraction of background values. The rhBZLF1 peptide pool consists of 60 15-mer peptides with 11-amino-acid overlap. Peptides were reconstituted in DMSO.

Statistical analysis.

For statistical analyses of data, several comparisons were made. To assess the overall magnitude of vaccine responses, areas under the curve (AUC) using increases of cytokine producing T cells (normalized after subtraction of background responses) over baseline counts (normalized after subtraction of background responses) were calculated. For these calculations, negative values were set at 0. The AUCs for animals belonging to both rhEBNA-1 vaccine groups were compared to the AUCs of control animals by using unpaired Mann-Whitney tests. Comparisons between all three groups or between the three types of T cell subsets were conducted by analysis of variance (ANOVA). Comparisons for individual patterns of functions were made by Fisher's least significant difference test by ANOVA. All multiple comparisons were Bonferroni adjusted to control for type I error rate, and P values of <0.05 were considered significant. Data were analyzed using Prism version 6a software.

RESULTS

Construction and in vitro testing of vectors.

To test if vaccination can expand ongoing rhEBNA-1-specific T cell responses, we developed several vaccines expressing rhEBNA-1 in which the GAr domain was removed from the coding sequence. In one version, the truncated protein was genetically fused into the C-terminal domain of a mutated herpes simplex virus one (HSV-1) glycoprotein D (gD), termed “super gD” (SgD). As we have previously shown, HSV-1 gD and SgD augment T cell responses to antigens fused into their C terminus by binding the bimodal herpesvirus entry mediator (HVEM) (36) and preventing inhibitory molecules from binding (29, 37). To control for the effect of SgD, a second vaccine expressed the truncated rhEBNA-1 within a version of SgD with strongly reduced binding to HVEM (NBEFSgD-rhEBNA-1) (28, 29). Schematic representations of the chimeric proteins are shown in Fig. 1A. In a third version, the GAr-deleted rhEBNA-1 was expressed without a fusion partner (rhEBNA-1). Finally, to control for any nonspecific effects of vaccination, we used a vaccine that expressed gD fused to an irrelevant antigen, i.e., the nucleoprotein of influenza A virus (gDNP). Vaccines based on recombinant E1-deleted AdC68 and AdC6 viral vectors were used to deliver the antigens.

FIG 1.

AdC vaccine constructs and in vitro testing. (A) Schematic representation of the chimeric proteins SgD-rhEBNA-1 (top) and NBEFSgD-rhEBNA-1 (bottom). TM, transmembrane domain; light gray band, mutation to create SgD; dark gray bands, mutations that block HVEM binding (20). (B) Western blot analyses of protein lysates harvested from CHO-CAR cells infected with 1010, 109, or 108 vp of the indicated constructs. (C) Cell surface staining of infected CHO-CAR cells for SgD-EBNA1 and NBEFSgD-EBNA1. Cells were infected for 48 h with 1010 or 109 vps of AdC68-SgD-EBNA1 or AdC68-NBEFSgD-EBNA1 or 1010 vps of AdC68-gD and stained with mouse anti-Flag antibody and probed with goat anti-mouse IgG-Alexa Fluor 700. (D) An HVEM binding assay was used to test the ability of the chimeric proteins to bind their receptor. Normalized protein extracts from CHO-CAR cells infected with AdC68 encoding SgD-rhEBNA-1 show enhanced HVEM binding (when comparing AUC by one-way ANOVA: versus AdC68-NBEFSgD-rhEBNA-1, P = 0.0036; versus AdC68-rhEBNA-1, P = 0.0035). (E) Mature DCs from an rhLCV-seropositive rhesus macaque were infected with the indicated Ad vectors or pulsed with rhEBNA-1 peptide and then cocultured with autologous rhEBNA-1-specific CD4+-depleted CD8+ T cells. rhEBNA-1-specific responses were measured by an IFN-γ ELISPOT assay after 16 h, and results are shown as average spots per 106 CD8+ T cells based on quadruple experiments for the DC + T cells and triplicate experiments for the other samples. Significant differences are denoted by asterisks: all P values are <0.0001, except for peptide versus AdC68-rhEBNA-1 (P = 0.0009) and AdC68-gDrhEBNA-1 (P = 0.0036). P values were calculated using one-way ANOVA, with a P value of <0.05 considered significant. All multiple comparisons were Bonferroni adjusted to control for type I errors.

We quantified rhEBNA-1 expression levels by immunoblotting protein lysates from AdC vector-infected CHO-CAR cells. The transgene product was detected with antibodies against the Flag epitope (Fig. 1B, top panel) or gD (Fig. 1B, middle panel). The two versions of the gD-rhEBNA-1 fusion proteins achieved similar levels of expression at the expected size of 90 kDa. The 55-kDa band detected only by the gD antibody is unrelated to rhEBNA-1, since it was also expressed by vectors encoding gD only and therefore reflects either a gD degradation product, an alternative splicing event, or cross-reactivity with an Ad vector-derived protein. The AdC-rhEBNA-1 vector expressed markedly higher levels of rhEBNA-1 than did the AdC-SgD-rhEBNA-1 vector (not shown), which would have made it difficult to determine whether differences in vaccinated animals were due to blockade of the HVEM pathway or to levels of rhEBNA-1 expression. We therefore used the two vectors with similar levels of rhEBNA-1 expression but differing abilities to block the HVEM pathway (SgD-rhEBNA-1 and NBEFSgD-rhEBNA-1) for in vivo comparisons.

Cell surface staining of infected CHO-CAR cells for SgD-rhEBNA-1 and NBEFSgD-rhEBNA-1 with an antibody to Flag showed similar expression levels (Fig. 1C). This indicates that the gD transmembrane domain redirected rhEBNA-1 from the nucleus to the cell surface at similar levels regardless of the version of gD.

The chimeric proteins were tested in an HVEM binding assay to confirm enhanced and reduced binding to SgD and NBEFSgD, respectively. Normalized protein extracts from cells infected with AdC68 vectors encoding SgD-rhEBNA-1, NBEFSgD-rhEBNA-1, or rhEBNA-1 were added to plates coated with HVEM. Figure 1D shows the enhanced binding of SgD-rhEBNA-1 compared to NBEFSgD-rhEBNA-1 and rhEBNA-1 without gD, both of which failed to bind HVEM at the tested concentrations of protein.

To test if our vaccines could stimulate rhEBNA-1-specific effector T cells, rhesus macaque DCs were infected with the AdC68-rhEBNA-1 or AdC68-gD-rhEBNA-1 viral vectors and cultured with autologous rhEBNA-1-specific CD8+ T cells. T cell responses were measured by an IFN-γ ELISPOT assay. As shown in Fig. 1E, the rhEBNA-1 antigen could be efficiently processed and presented to rhEBNA-1-specific CD8+ T cells. DCs infected with the AdC68-gDrhEBNA vector were able to induce IFN-γ secretion by rhEBNA-1-specific T cells, and responses were comparable to those elicited by an AdC68-rhEBNA-1 vector that lacked gD. Empty vector or noninfected DCs did not induce a response. IFN-γ was produced by responding T cells, since cultures containing only infected DCs failed to produce IFN-γ.

Vaccination increases the frequency of rhEBNA-1-specific T cell responses.

To test if our vaccines could induce or expand rhEBNA-1-specific T cell responses in vivo, animals were injected i.m. with 1011 vps of AdC68 vectors expressing SgDrhEBNA-1 (group 1), NBEFSgDrhEBNA-1 (group 2), or gDNP (group 3). They were boosted 15 weeks later with the same doses of AdC6 vectors expressing the same inserts. Responses were measured from blood collected 2 months prior to and on the day of vaccination to determine baseline responses and those at 2, 4, and 8 weeks after priming and 2, 4, and 6 weeks after boosting (weeks 17, 19, and 21) to test for vaccine-induced changes. RhEBNA-1-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cell responses were measured by ICS for IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α (15). We also analyzed the effects of vaccination on T cell subsets, i.e., effector (EFF), effector memory (EM), and central memory (CM) cells identified by additional stains for CD95, CD28, and CCR7. Results obtained by ICS were normalized to numbers of responding cells per 106 live CD3+ cells, and background data were subtracted. We used two criteria to define vaccine-induced increases of rhLCV-specific T cell responses. First, average normalized numbers of specific T cells from 5 rhLCV-seronegative animals were used to determine the detection limit of the assay; numbers of total cytokine-producing T cells (after background subtraction) had to be 2 standard deviations (SDs) above this limit. Second, animals were classified as vaccine responders if rhEBNA-1-specific cytokine responses increased 2 SDs or more above mean baseline responses for at least 3 time points after vaccination. Animals that met these criteria only within T cell subsets were also viewed as responders, as the additional stains used to identify EFF, EM, and CM cells increase staining sensitivity by reducing background noise. Details on individual immune responses can be found in Table 1 (CD8+ responses) and Table 2 (CD4+ responses).

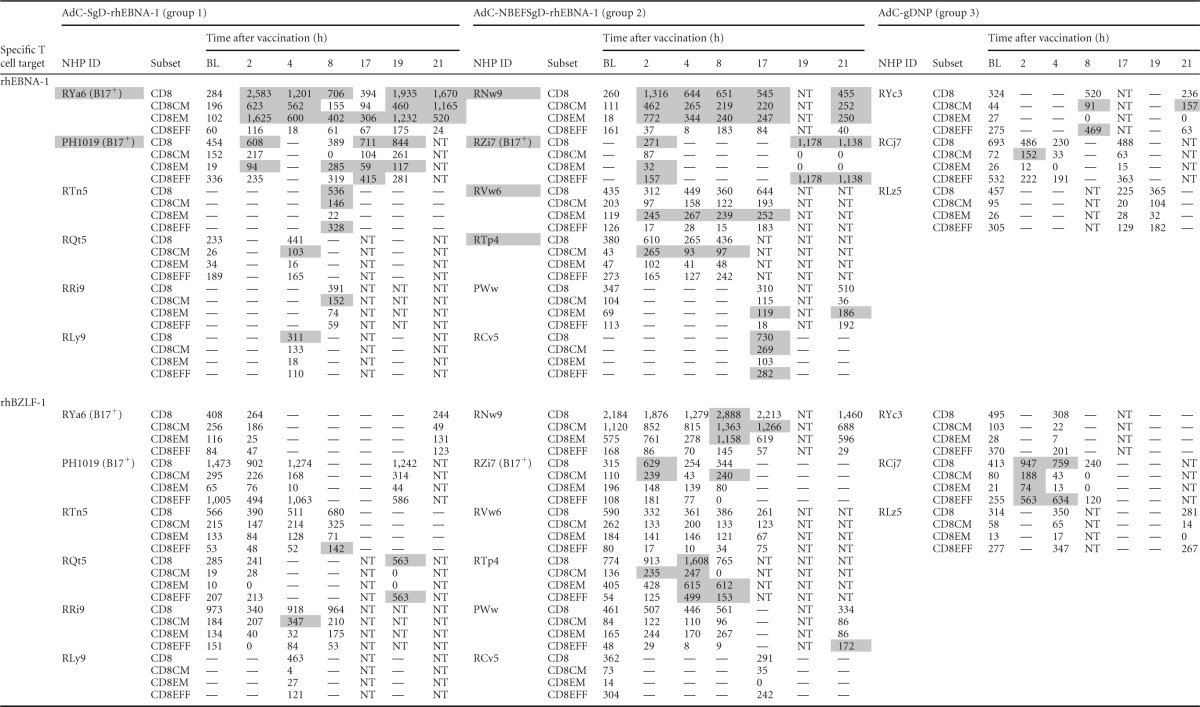

TABLE 1.

Number of CD8+ T cells/106 live CD3+ cellsa

RhEBNA-1-specific (top) and rhBZLF-1-specific (bottom) CD8+ T cell responses are shown at all pre- and postvaccination time points. Responses are normalized to 106 live CD3+ T cells after subtraction of background data for individual animals. —, values below the detection limit (based on rhLCV-seronegative rhesus macaques); data for time points at which the parental CD8+ T cell response was below the detection limit are not shown in the table (and were also omitted from the graphs). Peptide-specific vaccine responses greater than 2 SDs from the mean baseline are highlighted in gray. BL, baseline; NT, not tested; NHP, nonhuman primate; ID, identification number.

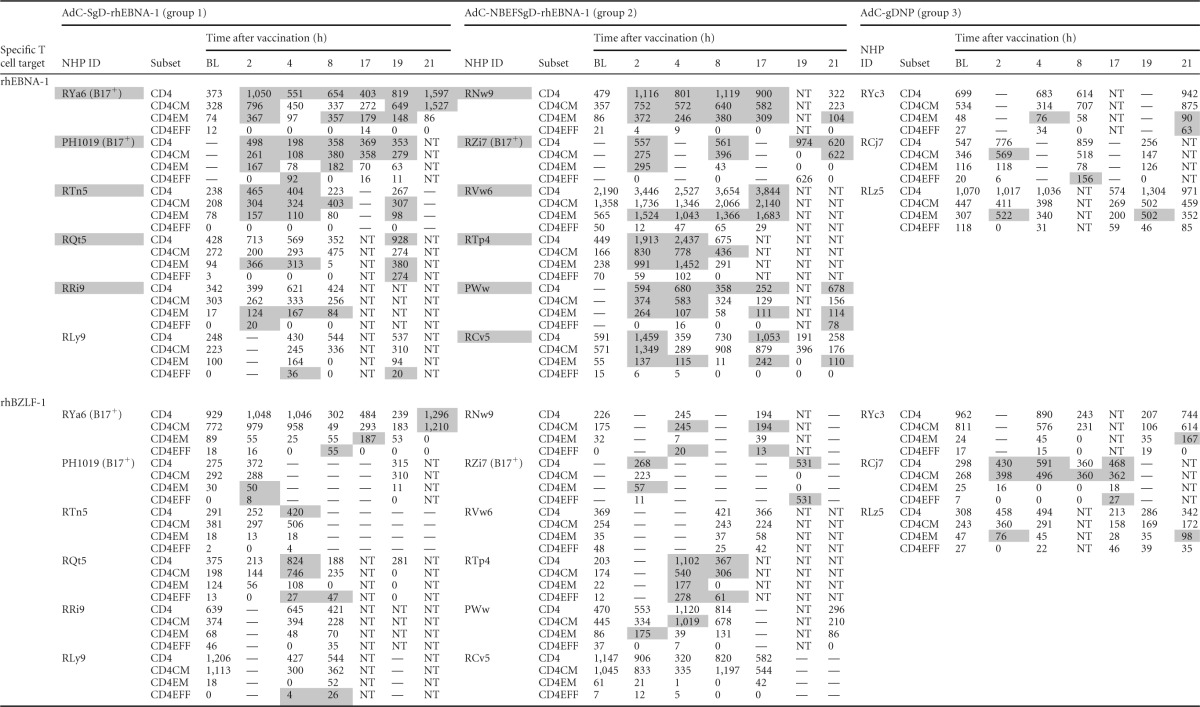

TABLE 2.

CD4+ T cell responses to rhEBNA-1 and rhBZLF-1a

RhEBNA-1-specific (top) and rhBZLF-1-specific (bottom) CD4+ T cell responses are shown at all pre- and postvaccination time points. Responses are normalized to 106 live CD3+ T cells after subtraction of background data for individual animals. —, values below the detection limit (based on rhLCV-seronegative rhesus macaques); data for time points at which the parental CD4+ T cell response was below the detection limit are not shown in the table (and were also omitted from the graphs). Peptide-specific vaccine responses greater than 2 SDs from the mean baseline are highlighted in gray. NHP, nonhuman primate; ID, identification number; BL, baseline; NT, not tested.

Based on these criteria, 50% (6/12) of the animals were identified as vaccine responders for rhEBNA-specific CD8+ T cells, and 92% (11/12) were vaccine responders for rhEBNA-1-specific CD4+ T cells (summarized in Table 3; primary data are provided in Tables 1 and 2). The one vaccine nonresponder was from group 1. Increases in rhEBNA-1-specific T cell responses were driven by the rhEBNA-1 vaccines, as none of the group 3 animals who received the control vectors qualified as vaccine responders. Additionally, none of the animals qualified as responders when T cells were tested against an irrelevant rhLCV antigen, i.e., no animals in any group developed sustained T cell increases against rhBZLF1, a highly immunogenic immediate early antigen of rhLCV (Tables 1 and 2).

Magnitude and differentiation status of rhLCV-specific CD8+ T cells after vaccination.

Numbers of rhEBNA-1-specific CD8+ T cells increased after vaccination. Increases were most pronounced and sustained within the CD8EM subset, while numbers of rhEBNA-1-specific CD8CM and CD8EFF cells increased only transiently (Fig. 2A). Increases of rhEBNA-1-specific T cells as measured by area under the curve were significantly larger than the corresponding rhBZLF-1-specific responses for overall CD8+ T (P = 0.048 by the Mann-Whitney test) and CD8EM (P = 0.039) cells (Fig. 2B). Increases of rhEBNA-1-specific T cells were also significantly larger than those of controls (for overall and EM cells, P = 0.048 and 0.024, respectively). For all vaccine responders, rhEBNA-1-specific CD8+ T cells increased about 4-fold from baseline, with an average increase of 474 total T cells and 277 CD8EM cells (6.5-fold change) per 106 live CD3+ cells after vaccination. Corresponding rhBZLF-1-specific responses and rhEBNA-1-specific responses within the control group remained stable or contracted, which indicates that increases in rhEBNA-1-specific CD8+ T cells were a result of vaccination.

FIG 2.

Magnitude of peptide-specific CD8+ T cell responses upon vaccination. PBMCs were stimulated with specific peptide pools, and ICS was used to measure production of IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α. Mean counts of rhEBNA-1-specific (A) and rhBZLF-1-specific (B) total cytokine-producing CD8+ T cells ± SD are plotted as a change from baseline (BL) for all vaccine responders of groups 1 (×, black line) and 2 (asterisk, gray line) and all animals of group 3 (+, dashed line). Peptide-specific CD8+ T cell responses are shown for overall, CM, EM, and EFF subsets (left to right). Raw data were used to calculate changes from baseline, and any values below the limit of detection were excluded from the calculation of the mean. All values are presented as numbers of responding cells per 106 live CD3+ cells. To calculate the sum of the peptide-specific response, we subtracted normalized background activity and then summed the 7 possible different combinations of functions. Significant differences were determined by comparing areas under the curve (AUC) and are as follows. For rhEBNA-1 versus rhBZLF-1 for all vaccine responders, CD8+ overall, P = 0.048, and EM, P = 0.039. For RhEBNA-1 for all vaccine responders versus controls, CD8+ overall, P = 0.048, and EM, P = 0.024. RhEBNA-1 CD8EM responses were also significant for vaccine responders within group 1 (rhEBNA-1 versus rhBZLF-1, P = 0.0081; rhEBNA-1 responders versus controls, P = 0.012). P values were calculated using two-sided Mann-Whitney tests (all responders grouped) or ANOVA (comparisons between all three groups), with a P value of <0.05 considered significant.

There were no significant differences in rhEBNA1-specific CD8+ T cell responses between groups 1 and 2. However, the number of rhEBNA-1-specific CD8EM subset responses of group 1 but not group 2 increased significantly more after vaccination than the corresponding rhBZLF-1 responses (P = 0.0081) or rhEBNA-1 responses of control animals (P = 0.012).

The selective increases of rhEBNA-1-specific CD8EM cells caused shifts in the proportions of the three CD8+ T cell subsets (Fig. 3A), while the proportions of rthBZLF-1-specific subsets did not change following vaccination (not shown). At baseline, most rhEBNA-1-specific responses were CD8CM or CD8EFF cells. After vaccination, the proportion of rhEBNA-1-specific CD8EM cells increased to nearly double the proportion at baseline for every time point (Fig. 3A, white bars). This shift, which clearly indicates that vaccination preferentially induced or expanded CD8EM cells, became significant by week 8 (P = 0.035).

FIG 3.

Proportions of peptide-specific CD8+ and CD4 +T cell subsets upon vaccination. The proportions of rhEBNA-1-specific CD8+ (A) and CD4+ (B) EFF (dark gray), CM (light gray), and EM (white) subsets are shown as a percentage of the total response at baseline and weeks 2, 8, and 17 after vaccination. For each subset, normalized counts were divided by the sum of all three subsets to determine the relative proportions. Results for individual animals are shown as filled circles, and responses for all vaccine responders are displayed as floating bars (5th to 95th percentiles) with lines at the median. Significant differences were determined by comparing the percentage of a given subset after vaccination to the percentage at baseline and are as follows: rhEBNA1-specific CD8EM and CD4EM cells at week 2, P = 0.035 and 0.045, respectively. P values were calculated using the two-sided Mann-Whitney test, with a P value of <0.05 considered significant.

Magnitude and differentiation status of rhLCV-specific CD4+ T cells after vaccination.

RhEBNA-1-specific CD4+ T cell responses increased after vaccination. These increases were pronounced within both CD4CM and CD4EM subsets, while CD4EFF responses remained stable (Fig. 4A). Increases of rhEBNA-1-specific T cells as measured by AUC were significantly larger than the corresponding rhBZLF-1-specific responses for overall CD4+ T (P = 0.0003), CD4CM (P = 0.0019), and CD4EM (P = 0.02) cells (Fig. 4B). Increases of rhEBNA-1-specific T cells were also significantly larger than the same responses among animals that received the control vaccine (overall and CM, P = 0.02 and 0.039, respectively). Numbers of rhEBNA-1-specific CD4+ T cells increased about 3-fold from baseline, with an average increase of 424 total T cells, 212 CD4CM cells, and 191 CD4EM cells per 106 live CD3+ cells. Corresponding rhBZLF-1-specific responses and rhEBNA-1-specific responses within the control group remained stable or contracted, therefore indicating that increases in rhEBNA-1-specific CD4+ T cells were a result of vaccination.

FIG 4.

Magnitude of peptide-specific CD4+ T cell responses upon vaccination. Mean counts of rhEBNA-1-specific (A) and rhBZLF-1-specific (B) cytokine-producing CD4+ T cells ± SD are plotted as a change from baseline (BL). This figure is organized in the same fashion as Fig. 2. Significant differences are as follows. For rhEBNA-1 versus rhBZLF-1 for all vaccine responders, CD4+ overall, P = 0.0003; CM, P = 0.0019; EM, P = 0.02. For RhEBNA-1 for all vaccine responders versus controls, CD4+ overall, P = 0.02; CM, P = 0.039. RhEBNA-1 responses were also significant for vaccine responders within group 2 (for group 2 versus group 1, CD4+ overall, P = 0.0173; for group 2 rhEBNA-1 versus group 2 rhBZLF-1, CD4+ overall, P = 0.002; CM, P = 0.0009; EM, P = 0.021; for group 2 rhEBNA-1 versus control rhEBNA-1, CD4+ overall, P = 0.024; CM, P = 0.047; EM, P = 0.038). Responses of RhEBNA-1 CD4EFF cells were significantly lower than those of both CD4CM (P = 0.0058) and CD4EM (P = 0.019) cells. P values were calculated using two-sided Mann-Whitney tests (all responders grouped) or ANOVA (comparisons between all three groups), with a P value of <0.05 considered significant.

RhEBNA1-specific overall CD4+ T cell responses were significantly larger for group 2 responders than for group 1 (P = 0.0173, AUC, by the Mann-Whitney test); however, subset responses between the same groups were not significantly different. The number of rhEBNA-1-specific T cells within group 2 but not group 1 also increased significantly more after vaccination than the corresponding rhBZLF-1 responses (for overall, CM, and EM cells, P = 0.002, 0.0009, and 0.021, respectively) or rhEBNA-1 responses of control animals (for overall, CM, and EM cells, P = 0.024, 0.047, and 0.038, respectively). This may suggest that vaccines expressing rhEBNA-1 with a non-HVEM-binding version of gD induced more-potent CD4+ T cell responses than did the SgDrhEBNA-1 vaccines.

The distribution of rhEBNA-1-specific CD4+ CM and EM subsets shifted after vaccination (Fig. 3B), while rhBZLF-1-specific CD4+ T cell subsets remained stable (not shown). The shift in rhEBNA-1-specific subset proportions, which was significant at week 2 (P = 0.045), was caused by pronounced increases of CD4EM cells, which resulted in a relative reduction in the percentage of CD4CM cells.

Cytokine profile of rhLCV-specific T cells after vaccination.

We assessed T cell functions after vaccination using Boolean gating to analyze seven possible different combinations of IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α production (26). Cytokine profiles following vaccination were analyzed at weeks 2 and 8 after priming and at week 2 after the boost.

Vaccination caused transient shifts in the cytokine profile of rhEBNA-1-specific CD8+ T cells (Fig. 5A). At baseline, most rhEBNA-1-specific CD8+ T cells produced IFN-γ (light blue; EFF, 65%; CM, 25%; EM, 36%) or IL-2 alone (pink; EFF, 26%; CM, 34%; EM, 22%). The percentage of CD8CM and CD8EM cells producing IFN-γ increased significantly by 2 weeks after priming (week 2; CM, 56%, P = 0.0006; EM, 71%, P = 0.0006) and 2 weeks after boosting (week 17; CM, 59%, P = 0.0005; EM, 71%, P = 0.0018). The average percentage of CD8CM cells producing IL-2 alone, a cytokine generally associated with more resting T cells, significantly decreased at weeks 2 (11%, P = 0.011), 8 (10%, P = 0.0049), and 17 (11%, P = 0.02) after vaccination. In addition, there was a transient increase in the percentage of IFN-γ+IL-2+ CD8CM cells at week 8 (baseline, 12%; week 8, 45%, P = 0.012). As a result, the proportion of polyfunctional CD8CM responses increased at week 8. The proportion of cells producing single-, double-, and triple-cytokine responses did not change at any time point for CD8EFF or CD8EM cells. Overall, these results confirm that AdC vectors preferentially expanded rhEBNA-1-specific T cell responses that produced IFN-γ, a cytokine with potent antiviral activity.

FIG 5.

Cytokine profiles of rhLCV-specific T cells upon vaccination. Pies represent the average percentages of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells making each combination of IFN-γ (g), IL-2 (2), and TNF-α (a) following stimulation with specific peptides. RhEBNA-1-specific (A) and rhBZLF-1-specific (B) CD8EFF, CD8CM, and CD8EM responses are shown at baseline (BL) and at weeks 2, 8, and 17 after vaccination. The same time points are shown for rhEBNA-1specific (C) and rhBZLF-1-specific (D) CD4CM and CD4EM responses. Numbers of peptide-specific CD4EFF responses were all very low and are therefore not shown. For all responding animals, normalized cell counts were calculated for each function within every subset. Values for each of the seven possible combinations of functions were then divided by the sum of all seven, and pie charts reflect the ratios of those means. Significant differences are described in Results.

As expected, the cytokine profile of rhBZLF-1-specific CD8+ T cells did not markedly change after vaccination. Most rhBZLF-1-specific CD8+ T cells produced IFN-γ alone (light blue; EFF, 54%; CM, 47%; EM, 51%) or in combination with IL-2 (yellow; EFF, 11%; CM, 20%; EM, 20%) at baseline and at weeks 2, 8, and 17 after vaccination (Fig. 5B). The only significant change was a decrease in the percentage of IFN-γ+ CD8EM cells at week 8 (26%, P = 0.017) and therefore a transient decrease in the proportion of single-cytokine-producing cells. This shift was most likely caused by decreases in the magnitude of rhBZLF-1 responses after vaccination.

Vaccination increased the absolute numbers of polyfunctional rhEBNA-1-specific CD4+ T cells without changing the cytokine pattern. RhEBNA-1-specific CD4+ T cells were highly polyfunctional at baseline and at weeks 2, 8, and 17 after vaccination (Fig. 5C). At each of these time points, large proportions of cells produced two or three cytokines (baseline CM, 44%; EM, 49%) as well as IFN-γ (CM, 19%; EM, 28%) and IL-2 alone (CM, 25%; EM, 8%). The only significant change after vaccination was an increase in the proportion of IFN-γ+ CD4EM cells at week 17 (50%, P = 0.037); however, the ratio of triple, double, and single responses did not change. Thus, vaccine-induced CD4+ T cell responses remained highly polyfunctional.

Subtle changes in the cytokine profile of rhBZLF-1-specific CD4+ T cells over time indicate that these cells may have shifted toward a response closer to resting memory. CD8CM cells produced mostly IL-2+ (pink, 47%) or TNF-α+ (purple, 18%) at baseline and at weeks 2, 8, and 17 after vaccination (Fig. 5D). However, the proportion of IL-2+ CD8CM cells increased significantly at week 17 (73%) compared to all other time points before and after vaccination (versus baseline, P = 0.0047; versus week 2, P < 0.0001; versus week 8, P = 0.0004). Additionally, the large proportion of CD8EM cells that produced IFN-γ at baseline (30%) and at week 2 after vaccination (27%) decreased significantly by week 8 (8%, P = 0.0013). IFN-γ is typically associated with cells that are fully activated, and therefore such decreases further support the notion that rhBZLF-1 CD4+ T cells were transitioning toward a response closer to resting memory.

Vaccination expands rhEBNA-1-specific T cells with cytolytic potential.

Target cell lysis is one of the most crucial T cell functions involved in clearing virus-infected cells. While cytokine production provides information on the T cells' functional capacity, it does not directly assess their ability to lyse target cells. We therefore measured production of granzyme B, a lytic enzyme that promotes target cell apoptosis. Granzyme B was measured in CD8+ and CD4+ T cells for three of the highest responders from each vaccine group using the same methods as those described above. Because granzyme B is stored in cytolytic granules regardless of activation status, peptide-specific responses were considered positive only if granzyme B was produced in combination with one or more cytokines.

We found that vaccine-induced rhEBNA-1-specific CD8+ T cells produced granzyme B. Although the proportion of granzyme B+ CD8+ T cells was largest at baseline (Fig. 6A), absolute numbers of granzyme B-producing CD8+ T cells tended to increase after vaccination. At baseline, most cells produced granzyme B together with TNF-α, but by week 2 after vaccination there was a significant increase in the magnitude of cells producing granzyme B with IFN-γ (shown in light blue; P < 0.0001). In contrast, there were significant decreases in numbers of rhBZLF-1-specific CD8+ T cells that produced granzyme B with TNF-α at every time point after vaccination (week 2, P = 0.0004; week 8, P = 0.0105; week 17/19, P < 0.0001). As a result, the proportion of rhBZLF-1-specific granzyme B+ responses decreased significantly at weeks 2 (P = 0.0313) and 17/19 (P = 0.0173). As expected, the majority of granzyme B+ rhEBNA-1-specific CD8+ T cells were low in CCR7, a homing marker for lymphatic tissues, as is typical for CD8EM cells (Fig. 6B). Expression of CCR7 on granzyme B+ rhEBNA-1-specific CD8+ T cells was compared to expression of CCR7 on CD8EFF cells, memory CD8+ T cells, and naive CD8+ T cells. As expected, CCR7 expression on CD8EFF cells (orange) was similar to that on granzyme B+ rhEBNA-1-specific CD8+ T cells, both of which were reduced in comparison to CCR7 expression on CD8+ memory (blue) and CD8+ naive (green) T cells.

FIG 6.

Granzyme B production by rhLCV-specific T cells. Six of the highest vaccine responders (three from each group) were evaluated for granzyme B-producing T cells. PBMCs were stimulated with overlapping peptide pools, and ICS was used to measure production of granzyme B (denoted B), IFN-γ (g), IL-2 (2), and TNF-α (a). Bars reflect the average magnitudes of granzyme B+ CD8+ (A) and CD4+ (C) memory cells producing each combination of cytokines after stimulation with specific peptides. The total sums of all peptide-specific cytokine responses at each time point are listed above the bars. Total values reflect the sum of every combination of the four functions tested; cells that produced only granzyme B were excluded. RhEBNA-1-specific (left) and rhBZLF-1-specific (right) responses are shown at baseline (BL) and at weeks 2, 8, and 17/19 after vaccination. CCR7 expression by rhEBNA-1-specific memory CD8+ T cells that produce granzyme B with all combinations of cytokines (red) is shown in comparison to total nonspecific memory (blue), naive (green), and effector (orange) populations. (B) Responses are shown at baseline and week 8 for one representative vaccine responder. Responses at weeks 2 and 17/19 were the same as at week 8 and are therefore not shown. Significant differences are described in Results.

Vaccination induced a sustained increase in numbers of rhEBNA-1-specific CD4+ T cells that produced granzyme B—mostly with TNF-α and/or IFN-γ (Fig. 6C). The numbers of granzyme B+/IFN-γ+ and granzyme B+/IFN-γ+/TNF-α+ CD4+ T cells increased more than 6 and 10 times from baseline, respectively. Responses were significantly larger than baseline by 2 weeks (B+γ+, P = 0.0046) and 8 weeks (B+γ+α+, P = 0.0046) after vaccination. Despite these changes, the average proportion of granzyme B+ responses did not significantly change from baseline, where more than one-quarter of specific CD4+ memory T cells produced granzyme B in combination with other factors. In contrast, numbers of granzyme B+ rhBZLF-1-specific CD4+ T cells progressively declined following vaccination. There was a significant decrease in the number of rhBZLF-1-specific CD4+ T cells that produced granzyme B with TNF-α at week 17/19 (P = 0.0128), and as a result, the proportion of granzyme B+ responses also decreased significantly at the same time points (P = 0.03). This decrease in rhBZLF-1-specific granzyme B+ CD4+ T cells further indicates their differentiation toward a more resting phenotype. RhLCV-specific cytolytic T cells are crucial for controlling the outgrowth of virus-infected cells (38, 39), and we have shown that rhEBNA-1-specific T cells expanded through vaccination produce the cytolytic molecule granzyme B.

DISCUSSION

EBV is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. While the development of a vaccine to prevent infection or treat EBV-associated diseases is of high priority (4), therapeutic vaccines that aim to expand ongoing immune responses to persisting viruses like EBV face a unique set of challenges. Neutralizing antibodies are generally ill suited to clear cells that have already been infected, and T cells may be difficult to expand if recurrent antigen exposure by viral reactivations has caused terminal differentiation and functional T cell impairments (40). EBNA-1 is an important target for immune responses that aim to reduce EBV reservoirs in latently infected cells because it is the only antigen synthesized during all stages of latency and in all EBV-associated malignancies. Despite its importance, the ability to boost rhEBNA-1 T cell responses in rhesus macaques has never been tested. In this proof-of-concept study, we are the first to report that ongoing rhEBNA-1-specific T cell responses during persistent rhLCV infection in rhesus macaques can be expanded upon vaccination.

We developed and tested two prime-boost vaccine regimens based on replication-defective chimpanzee-derived adenoviral (AdC) vectors that express rhEBNA-1. Because humans are our eventual target population, we chose simian-derived Ad vectors rather than Ad vectors based on human serotypes in order to prevent neutralization of the vaccine construct by antibodies to the vaccine carrier (34). Ad vectors derived from chimpanzee serotypes (41) are highly immunogenic (42–45), have low prevalence rates in human cohorts (46), and are well suited for clinical development (47). Vaccines expressed a GAr-deleted form of rhEBNA-1 that was fused to HSV-gD to potentially further promote T cell recall responses. The N terminus of HSV-gD binds to the bimodal HVEM (36) and prevents inhibitory molecules like BTLA from binding and signaling during T cell activation (37). To control for this effect, an HVEM-nonbinding version of HSV-gD was also tested. Animals were distributed as evenly as possible between vaccine groups based on age, Mamu phenotype, and rhLCV-specific T cell responses. Because T cells targeting persisting viruses tend to fluctuate in response to reactivations, we enumerated and characterized rhEBNA-1- and rhBZLF-1-specific T cell responses at two time points prior to vaccination (26) and set stringent criteria to assess if vaccination expanded rhEBNA-1-specific T cells. We found that vaccination increased the numbers of circulating rhEBNA-1-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cells regardless of gD binding ability and that booster immunization was relatively ineffective. Vaccination augmented mainly CD8EM, CD4CM, and CD4EM cells. Responses were highly functional, and T cells produced various combinations of the cytokines IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α and the cytolytic molecule granzyme B. Furthermore, responses were vaccine specific, as T cell responses to the lytic antigen rhBZLF-1 did not increase following vaccination.

The ability to increase both CD8+ and CD4+ T cell responses through vaccination was an important finding of this study. While CD8+ T cells can eliminate virus-infected cells, CD4+ T cells can also target virus that persists in major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II+ cells. rhLCV-infected B cells and also some EBV-associated malignancies express both MHC classes I and II (48), and EBNA-1-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cells are both capable of lysing target cells in vitro (17, 18). Vaccination expanded specific CD8+ T cell responses in 2/6 animals from group 1 and 4/6 animals from group 2. Two of the vaccine responders from group 2 (RVw-6 and RTp-4) developed significant changes within T cell subsets (EM and CM, respectively) without changes in total numbers. This indicates a vaccine-specific effect on the phenotype of rhEBNA-1-specific T cells. One animal (RZi-7) developed a response after vaccination that was not detected at baseline, which indicates that vaccination may have induced new responses, although it is also possible that vaccination increased the magnitude of ongoing responses from below to above our limit of detection in this animal. Interestingly, the Mamu genotype may have influenced responsiveness, as all three of the Mamu B*17+ animals developed vaccine-specific CD8+ T cell responses. In comparison, a larger number of animals (11/12) developed specific CD4+ T cell responses to vaccination, including all three that did not have detectable rhEBNA-1-specific CD4+ T cells at baseline. About one-half of the vaccine responders from each group (group 1, 3/5; group 2, 3/6) developed significant changes within T cell subsets without changes in total numbers. It is perhaps not surprising that vaccination stimulated more CD4+ than CD8+ T cell responses, as EBNA-1-specific CD4+ T cell epitopes are more immunodominant in both humans (49, 50) and rhesus macaques (26).

RhLCV-specific cytolytic T cells are crucial for controlling the outgrowth of virus-infected cells (38, 39, 51), but utilization of the perforin/granzyme pathway is largely dependent on T cell specificity (52, 53). Importantly, we found that numbers of rhEBNA-1-specific CD8+ T cells producing granzyme B increased after vaccination. We also found large and sustained increases in numbers of granzyme B-producing CD4+ T cells. By just 2 weeks after vaccination, numbers of specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cells producing granzyme B had increased about 3 times over baseline levels. Most granzyme B was produced in combination with IFN-γ and/or TNF-α, which is typical for cytolytic EFF/EM T cells. While in vitro killing assays would have provided the most direct functional analysis, granzyme B expression by flow cytometry serves as a surrogate assay that provides a more quantitative assessment of numbers of potentially lytic cells. Our findings suggest that both CD8+ and CD4+ rhEBNA-1-specific T cells may participate in the elimination of rhLCV-infected cells.

It is also interesting that numbers of granzyme B+ rhBZLF-1-specific T cells decreased after vaccination. Within the same population, numbers of IFN-γ+ cells decreased and IL-2+ cells increased. Together, this indicates that rhBZLF-1-specific T cells were differentiating toward a more resting phenotype. Such differentiation could reflect a vaccine-induced reduction in rhLCV reactivation events. It would have been of interest to measure rhLCV loads before and after vaccination, as this would have provided the most direct evidence of vaccine efficacy or lack thereof. Unfortunately, only 1 in 105 to 106 peripheral B cells carries EBV in healthy subjects (35, 54). Because the viral genome is present at such low levels, it is difficult to detect viral load fluctuations in live animal studies, in which peripheral blood samples are limited.

We were intrigued to find that differences in immune responses between animals vaccinated with either rhEBNA-1 vaccine regimen were too subtle to clearly demonstrate an effect of HSV-gD. This is because we have previously shown that expression of antigen within HSV-gD augments primary antigen-specific CD8+ T cell responses in mice, and such responses were larger than with antigen alone or when expressed within a nonbinding HSV-gD (29). This study was the first to test the same approach for the expansion of ongoing T cell responses during a persistent viral infection in rhesus macaques. While differences in T cell responses to rhEBNA-1 expressed within the binding (group 1) or nonbinding (group 2) version of gD were not significant, it is interesting that only animals who received the vaccine with binding gD developed increased CD8EM responses that were significantly larger than corresponding rhBZLF-1 responses as well as rhEBNA-1-specific responses of control animals. The opposite was found for CD4+ responses, whereby only animals that received the nonbinding version of gD developed significant increases in CD4CM and CD4EM responses.

To determine if additional factors influenced whether or not an animal responded to vaccination, we compared baseline immune responses between responders and nonresponders. Total numbers of rhEBNA-1-specific CD8+ or CD4+ T cells were largely comparable at baseline (data not shown), so it is unlikely that differences in prevaccination T cell responses influenced whether or not an animal responded. In terms of cytokine production, vaccine responders tended to have a higher proportion of polyfunctional rhEBNA-1-specific CD8CM cells at baseline than did nonresponders (data not shown, P = 0.048), which could suggest a higher proliferative capacity of polyfunctional T cells than of those with a more restricted functional profile.

A previous study explored the feasibility of EBNA-1-specific immunotherapy for treatment of EBV-associated cancer (55). In this study, an Ad-based vaccine expressing a GAr-depleted sequence of EBNA-1 fused to epitopes of latent membrane protein (LMP) of EBV was tested for in vitro expansion of T cells obtained from patients with EBV-associated recurrent metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. More than one-half of the T cell lines contained EBNA-1-specific CD8+ T cells following in vitro expansion, demonstrating that humans develop EBNA-1-specific CD8+ T cells, which can be expanded upon further antigenic stimulation. While adoptive transfer of ex vivo-expanded EBV-specific T cells has resulted in sustained clinical responses in some patients (56), adoptive immunotherapy is costly, requires access to highly specialized health care facilities, and is therefore an impractical solution for the thousands of patients diagnosed annually with EBV-associated diseases. Another study showed that EBNA-1-specific CD8+ T cells could be isolated from healthy human adults as well as from patients with posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disease (57). These results are in agreement with our studies, which showed not only that rhLCV-infected rhesus macaques mount an rhEBNA-1-specific CD8+ T cell response upon natural infection but also that these CD8+ T cells can be expanded in vivo upon vaccination. Responses were sufficiently robust to allow for their detection directly ex vivo without further expansion through extended in vitro culture.

Our study is the first to assess rhEBNA-1-based vaccines in a seropositive nonhuman primate study. We showed that rhEBNA-1-specific T cells can be expanded through vaccination and also that these T cells are highly functional. The main limitation of the vaccines was that only one-half of the animals showed increases in CD8+ T cell responses, and responsiveness appeared to be influenced by the Mamu genotype. This suggests that the numbers of potently MHC class I-binding epitopes are limited within rhEBNA-1 (58). Our stringent criteria for responsiveness, which stipulated that T cell counts had to increase significantly over baseline at three of the tested time points, combined with the limited numbers of animals, may have prevented us from identifying weak responders.

In summary, the results presented here confirm that rhEBNA-1 is a valid target for a T cell vaccine to rhLCV. Future studies should aim at generating more-robust rhEBNA-1-specific T cell responses. It would be of interest to monitor the effect of vaccination on viral load or on the frequency of virus-infected cells as a potential readout for a positive vaccine response (54). Additional testing of modified vaccines in rhLCV-seropositive and -seronegative rhesus macaques is also warranted to further explore rhEBNA-1-based vaccines for prevention and treatment of EBV-associated diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grants from the NIH/NCI to P.M.L. (1RC2CA148325) and to the Yerkes National Primate Research Center (P51OD11132). R.L. was further supported by the University of Pennsylvania Training Grant in Vaccines and Immune Therapy (grant 5T32AI70099-4) awarded from the GTV graduate program of the University of Pennsylvania. Services at the New England Primate Research Center were supported by a base grant (P51OD011103).

We thank C. Cole for assisting us in formatting the manuscript and David O'Connor and Roger Wiseman (Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA) for helping us with genotyping of the animals.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 12 February 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Cohen JI. 2000. Epstein-Barr virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 343:481–492. 10.1056/NEJM200008173430707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thorley-Lawson DA, Gross A. 2004. Persistence of the Epstein-Barr virus and the origins of associated lymphomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 350:1328–1337. 10.1056/NEJMra032015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cao SM, Simons MJ, Qian CN. 2011. The prevalence and prevention of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in China. Chin. J. Cancer 30:114–119. 10.5732/cjc.010.10377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen JI, Fauci AS, Varmus H, Nabel GJ. 2011. Epstein-Barr virus: an important vaccine target for cancer prevention. Sci. Transl. Med. 3:107fs107. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henle W, Henle G. 1974. The Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) in Burkitt's lymphoma and nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Ann. Clin. Lab Sci. 4:109–114 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rickinson A, Kieff E. 2007. Epstein-Barr Virus, p 2655–2700 In Knipe D, Howley P. (ed), Virology, 5th ed. Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lossius A, Johansen JN, Torkildsen O, Vartdal F, Holmoy T. 2012. Epstein-Barr virus in systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis-association and causation. Viruses 4:3701–3730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tempera I, Klichinsky M, Lieberman PM. 2011. EBV latency types adopt alternative chromatin conformations. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002180. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leight ER, Sugden B. 2000. EBNA-1: a protein pivotal to latent infection by Epstein-Barr virus. Rev. Med. Virol. 10:83–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frappier L. 2012. Contributions of Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1) to cell immortalization and survival. Viruses 4:1537–1547. 10.3390/v4091537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dantuma NP, Sharipo A, Masucci MG. 2002. Avoiding proteasomal processing: the case of EBNA1. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 269:23–36. 10.1007/978-3-642-59421-2_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levitskaya J, Sharipo A, Leonchiks A, Ciechanover A, Masucci MG. 1997. Inhibition of ubiquitin/proteasome-dependent protein degradation by the Gly-Ala repeat domain of the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:12616–12621. 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tellam JT, Lekieffre L, Zhong J, Lynn DJ, Khanna R. 2012. Messenger RNA sequence rather than protein sequence determines the level of self-synthesis and antigen presentation of the EBV-encoded antigen, EBNA1. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1003112. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tellam J, Connolly G, Green KJ, Miles JJ, Moss DJ, Burrows SR, Khanna R. 2004. Endogenous presentation of CD8+ T cell epitopes from Epstein-Barr virus-encoded nuclear antigen 1. J. Exp. Med. 199:1421–1431. 10.1084/jem.20040191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Voo KS, Fu T, Wang HY, Tellam J, Heslop HE, Brenner MK, Rooney CM, Wang RF. 2004. Evidence for the presentation of major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1 peptides to CD8+ T lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 199:459–470. 10.1084/jem.20031219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Munz C, Bickham KL, Subklewe M, Tsang ML, Chahroudi A, Kurilla MG, Zhang D, O'Donnell M, Steinman RM. 2000. Human CD4(+) T lymphocytes consistently respond to the latent Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen EBNA1. J. Exp. Med. 191:1649–1660. 10.1084/jem.191.10.1649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee SP, Brooks JM, Al-Jarrah H, Thomas WA, Haigh TA, Taylor GS, Humme S, Schepers A, Hammerschmidt W, Yates JL, Rickinson AB, Blake NW. 2004. CD8 T cell recognition of endogenously expressed Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1. J. Exp. Med. 199:1409–1420. 10.1084/jem.20040121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nikiforow S, Bottomly K, Miller G, Munz C. 2003. Cytolytic CD4(+)-T-cell clones reactive to EBNA1 inhibit Epstein-Barr virus-induced B-cell proliferation. J. Virol. 77:12088–12104. 10.1128/JVI.77.22.12088-12104.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heller KN, Arrey F, Steinherz P, Portlock C, Chadburn A, Kelly K, Munz C. 2008. Patients with Epstein Barr virus-positive lymphomas have decreased CD4(+) T-cell responses to the viral nuclear antigen 1. Int. J. Cancer 123:2824–2831. 10.1002/ijc.23845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moormann AM, Heller KN, Chelimo K, Embury P, Ploutz-Snyder R, Otieno JA, Oduor M, Munz C, Rochford R. 2009. Children with endemic Burkitt lymphoma are deficient in EBNA1-specific IFN-gamma T cell responses. Int. J. Cancer 124:1721–1726. 10.1002/ijc.24014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piriou E, van Dort K, Nanlohy NM, van Oers MH, Miedema F, van Baarle D. 2005. Loss of EBNA1-specific memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in HIV-infected patients progressing to AIDS-related non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 106:3166–3174. 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fogg MH, Wirth LJ, Posner M, Wang F. 2009. Decreased EBNA-1-specific CD8+ T cells in patients with Epstein-Barr virus-associated nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:3318–3323. 10.1073/pnas.0813320106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moghaddam A, Rosenzweig M, Lee-Parritz D, Annis B, Johnson RP, Wang F. 1997. An animal model for acute and persistent Epstein-Barr virus infection. Science 276:2030–2033. 10.1126/science.276.5321.2030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rivailler P, Carville A, Kaur A, Rao P, Quink C, Kutok JL, Westmoreland S, Klumpp S, Simon M, Aster JC, Wang F. 2004. Experimental rhesus lymphocryptovirus infection in immunosuppressed macaques: an animal model for Epstein-Barr virus pathogenesis in the immunosuppressed host. Blood 104:1482–1489. 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruf IK, Moghaddam A, Wang F, Sample J. 1999. Mechanisms that regulate Epstein-Barr virus EBNA-1 gene transcription during restricted latency are conserved among lymphocryptoviruses of Old World primates. J. Virol. 73:1980–1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leskowitz RM, Zhou XY, Villinger F, Fogg MH, Kaur A, Lieberman PM, Wang F, Ertl HC. 2013. CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses to latent antigen EBNA-1 and lytic antigen BZLF-1 during persistent lymphocryptovirus infection of rhesus macaques. J. Virol. 87:8351–8362. 10.1128/JVI.00852-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blake NW, Moghaddam A, Rao P, Kaur A, Glickman R, Cho YG, Marchini A, Haigh T, Johnson RP, Rickinson AB, Wang F. 1999. Inhibition of antigen presentation by the glycine/alanine repeat domain is not conserved in simian homologues of Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1. J. Virol. 73:7381–7389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Connolly SA, Landsburg DJ, Carfi A, Wiley DC, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ. 2003. Structure-based mutagenesis of herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D defines three critical regions at the gD-HveA/HVEM binding interface. J. Virol. 77:8127–8140. 10.1128/JVI.77.14.8127-8140.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lasaro MO, Tatsis N, Hensley SE, Whitbeck JC, Lin SW, Rux JJ, Wherry EJ, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ, Ertl HC. 2008. Targeting of antigen to the herpesvirus entry mediator augments primary adaptive immune responses. Nat. Med. 14:205–212. 10.1038/nm1704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou D, Zhou X, Bian A, Li H, Chen H, Small JC, Li Y, Giles-Davis W, Xiang Z, Ertl HC. 2010. An efficient method of directly cloning chimpanzee adenovirus as a vaccine vector. Nat. Protoc. 5:1775–1785. 10.1038/nprot.2010.134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DiMenna L, Latimer B, Parzych E, Haut LH, Topfer K, Abdulla S, Yu H, Manson B, Giles-Davis W, Zhou D, Lasaro MO, Ertl HC. 2010. Augmentation of primary influenza A virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses in aged mice through blockade of an immunoinhibitory pathway. J. Immunol. 184:5475–5484. 10.4049/jimmunol.0903808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Messmer D, Ignatius R, Santisteban C, Steinman RM, Pope M. 2000. The decreased replicative capacity of simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239Delta(nef) is manifest in cultures of immature dendritic cellsand T cells. J. Virol. 74:2406–2413. 10.1128/JVI.74.5.2406-2413.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fogg MH, Kaur A, Cho YG, Wang F. 2005. The CD8+ T-cell response to an Epstein-Barr virus-related gammaherpesvirus infecting rhesus macaques provides evidence for immune evasion by the EBNA-1 homologue. J. Virol. 79:12681–12691. 10.1128/JVI.79.20.12681-12691.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen H, Xiang ZQ, Li Y, Kurupati RK, Jia B, Bian A, Zhou DM, Hutnick N, Yuan S, Gray C, Serwanga J, Auma B, Kaleebu P, Zhou X, Betts MR, Ertl HC. 2010. Adenovirus-based vaccines: comparison of vectors from three species of adenoviridae. J. Virol. 84:10522–10532. 10.1128/JVI.00450-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rao P, Jiang H, Wang F. 2000. Cloning of the rhesus lymphocryptovirus viral capsid antigen and Epstein-Barr virus-encoded small RNA homologues and use in diagnosis of acute and persistent infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3219–3225 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC87360/pdf/jm003219.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rajcani J, Vojvodova A. 1998. The role of herpes simplex virus glycoproteins in the virus replication cycle. Acta Virol. 42:103–118 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stiles KM, Whitbeck JC, Lou H, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ, Krummenacher C. 2010. Herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D interferes with binding of herpesvirus entry mediator to its ligands through downregulation and direct competition. J. Virol. 84:11646–11660. 10.1128/JVI.01550-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khanolkar A, Yagita H, Cannon MJ. 2001. Preferential utilization of the perforin/granzyme pathway for lysis of Epstein-Barr virus-transformed lymphoblastoid cells by virus-specific CD4+ T cells. Virology 287:79–88. 10.1006/viro.2001.1020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gudgeon NH, Taylor GS, Long HM, Haigh TA, Rickinson AB. 2005. Regression of Epstein-Barr virus-induced B-cell transformation in vitro involves virus-specific CD8+ T cells as the principal effectors and a novel CD4+ T-cell reactivity. J. Virol. 79:5477–5488. 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5477-5488.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shin H, Wherry EJ. 2007. CD8 T cell dysfunction during chronic viral infection. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 19:408–415. 10.1016/j.coi.2007.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lasaro MO, Ertl HC. 2009. New insights on adenovirus as vaccine vectors. Mol. Ther. 17:1333–1339. 10.1038/mt.2009.130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fitzgerald JC, Gao GP, Reyes-Sandoval A, Pavlakis GN, Xiang ZQ, Wlazlo AP, Giles-Davis W, Wilson JM, Ertl HC. 2003. A simian replication-defective adenoviral recombinant vaccine to HIV-1 gag. J. Immunol. 170:1416–1422 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/170/3/1416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pinto AR, Fitzgerald JC, Giles-Davis W, Gao GP, Wilson JM, Ertl HC. 2003. Induction of CD8+ T cells to an HIV-1 antigen through a prime boost regimen with heterologous E1-deleted adenoviral vaccine carriers. J. Immunol. 171:6774–6779 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/171/12/6774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reyes-Sandoval A, Fitzgerald JC, Grant R, Roy S, Xiang ZQ, Li Y, Gao GP, Wilson JM, Ertl HC. 2004. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific immune responses in primates upon sequential immunization with adenoviral vaccine carriers of human and simian serotypes. J. Virol. 78:7392–7399. 10.1128/JVI.78.14.7392-7399.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tatsis N, Lasaro MO, Lin SW, Haut LH, Xiang ZQ, Zhou D, Dimenna L, Li H, Bian A, Abdulla S, Li Y, Giles-Davis W, Engram J, Ratcliffe SJ, Silvestri G, Ertl HC, Betts MR. 2009. Adenovirus vector-induced immune responses in nonhuman primates: responses to prime boost regimens. J. Immunol. 182:6587–6599. 10.4049/jimmunol.0900317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xiang Z, Li Y, Cun A, Yang W, Ellenberg S, Switzer WM, Kalish ML, Ertl HC. 2006. Chimpanzee adenovirus antibodies in humans, sub-Saharan Africa. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12:1596–1599. 10.3201/eid1210.060078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barnes E, Folgori A, Capone S, Swadling L, Aston S, Kurioka A, Meyer J, Huddart R, Smith K, Townsend R, Brown A, Antrobus R, Ammendola V, Naddeo M, O'Hara G, Willberg C, Harrison A, Grazioli F, Esposito ML, Siani L, Traboni C, Oo Y, Adams D, Hill A, Colloca S, Nicosia A, Cortese R, Klenerman P. 2012. Novel adenovirus-based vaccines induce broad and sustained T cell responses to HCV in man. Sci. Transl. Med. 4:115ra1. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haigh TA, Lin X, Jia H, Hui EP, Chan AT, Rickinson AB, Taylor GS. 2008. EBV latent membrane proteins (LMPs) 1 and 2 as immunotherapeutic targets: LMP-specific CD4+ cytotoxic T cell recognition of EBV-transformed B cell lines. J. Immunol. 180:1643–1654 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/180/3/1643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hislop AD, Taylor GS, Sauce D, Rickinson AB. 2007. Cellular responses to viral infection in humans: lessons from Epstein-Barr virus. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 25:587–617. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Landais E, Saulquin X, Houssaint E. 2005. The human T cell immune response to Epstein-Barr virus. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 49:285–292. 10.1387/ijdb.041947el [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Long HM, Haigh TA, Gudgeon NH, Leen AM, Tsang CW, Brooks J, Landais E, Houssaint E, Lee SP, Rickinson AB, Taylor GS. 2005. CD4+ T-cell responses to Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) latent-cycle antigens and the recognition of EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines. J. Virol. 79:4896–4907. 10.1128/JVI.79.8.4896-4907.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]