Abstract

Background/Aims

Despite improvements in endoscopic hemostasis and pharmacological therapies, upper gastrointestinal (UGI) ulcers repeatedly bleed in 10% to 20% of patients, and those without early endoscopic reintervention or definitive surgery might be at a high risk for mortality. This study aimed to identify the risk factors for intractability to initial endoscopic hemostasis.

Methods

We analyzed intractability among 428 patients who underwent emergency endoscopy for bleeding UGI ulcers within 24 hours of arrival at the hospital.

Results

Durable hemostasis was achieved in 354 patients by using initial endoscopic procedures. Sixty-nine patients with Forrest types Ia, Ib, IIa, and IIb at the second-look endoscopy were considered intractable to the initial endoscopic hemostasis. Multivariate analysis indicated that age ≥70 years (odds ratio [OR], 2.06; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.07 to 4.03), shock on admission (OR, 5.26; 95% CI, 2.43 to 11.6), hemoglobin <8.0 mg/dL (OR, 2.80; 95% CI, 1.39 to 5.91), serum albumin <3.3 g/dL (OR, 2.23; 95% CI, 1.07 to 4.89), exposed vessels with a diameter of ≥2 mm on the bottom of ulcers (OR, 4.38; 95% CI, 1.25 to 7.01), and Forrest type Ia and Ib (OR, 2.21; 95% CI, 1.33 to 3.00) predicted intractable endoscopic hemostasis.

Conclusions

Various factors contribute to intractable endoscopic hemostasis. Careful observation after endoscopic hemostasis is important for patients at a high risk for incomplete hemostasis.

Keywords: Aged, Cerebro-cardiovascular diseases, Hematemesis, Melena, Shock, Forrest type

INTRODUCTION

Acute hemorrhage from upper gastrointestinal (UGI) ulcers is a major cause of morbidity and mortality, as well as a common medical emergency. The incidence of cardiovascular or cerebrovascular diseases is increasing along with the increasing population of elderly individuals in Japan, and such diseases are usually treated with low-dose aspirin (LDA). However, LDA is one of the most important risk factors for bleeding UGI ulcers,1 and the prevalence of bleeding peptic ulcers associated with LDA is gradually increasing.2 Although endoscopic hemostasis for UGI bleeding is generally acceptable, it can be difficult to completely achieve in some patients, and excessive hemorrhage from UGI ulcers can be fatal. Endoscopic treatment of UGI bleeding has recently advanced along with the administration of high-dose intravenous proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). Despite improvements in endoscopic hemostasis and pharmacological therapies, UGI ulcers rebleed in 10% to 20% of patients,3,4,5,6 and those without early endoscopic reintervention or definitive surgery might be at a high risk for mortality. In fact, mortality rates related to ulcer bleeding have remained essentially unchanged at 5% to 8% during the past three decades.4,7

Therefore, determining which factors are involved in rebleeding after an initial endoscopic hemostasis is extremely important for patients with bleeding UGI ulcers. In addition, understanding the factors that contribute to intractable or insufficient initial endoscopic hemostasis is needed to advance the management of such ulcers.

Here, we aimed to define which factors are associated with intractability to endoscopic hemostasis in patients with bleeding UGI ulcers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Institutional Review Board of Aichi Medical University Hospital approved this retrospective, single-center study, which was performed at the Department of Gastroenterology at Aichi Medical University Hospital in Japan. Between April 2000 and December 2010, 428 patients with hematemesis, melena, or both, due to bleeding UGI ulcers underwent emergency endoscopy within 24 hours of arrival at Aichi Medical University Hospital, and all were admitted thereafter. According to the Forrest classification,8 patients with the following bleeding types were indicated for endoscopic hemostasis: Ia, spurting; Ib, oozing; IIa, nonbleeding visible vessels; IIb, adherent blood clots. Ulcers with stages IIc (black base) or III (clear ulcer base) were excluded from endoscopic hemostasis. Only patients with active bleeding ulcers (Forrest types Ia and Ib) and ulcers with stigmata of a recent hemorrhage (Forrest types IIa and IIb) were ultimately enrolled. We excluded patients with bleeding from a nonulcer etiology (varices, hemorrhagic erosive gastritis, Mallory-Weiss tears, vascular ectasia, or malignancies), coagulopathy, or a history of gastrectomy.

Endoscopic hemostasis was achieved by injecting hypertonic saline-epinephrine solution (HSE)9 or ethanol, using argon plasma coagulation (APC),10 hemostatic clips,11,12 or both HSE and hemostatic clips, as needed. After the initial endoscopic hemostasis, patients received acid-suppressive treatment with histamine-2 blockers or PPIs. A scheduled second-look endoscopy was performed within 24 hours after the initial endoscopic hemostasis when symptoms that are considered to indicate rebleeding from UGI ulcers, such as recurrent hematemesis or hematochezia, fresh blood outflow in nasogastric aspirate, or circulatory instability such as shock, were absent. Emergency endoscopy was done immediately after the initial endoscopic hemostasis when a clinical suspicion of rebleeding was present. Forrest types Ia, Ib, IIa, and IIb at the scheduled or emergency endoscopy were defined as being intractable to endoscopic hemostasis, and a second endoscopic hemostatic procedure was scheduled. Endoscopic hemostasis of Forrest types IIc and III at the scheduled or emergency endoscopy was considered successful, and ulcers that were considered not to require further hemostasis were not treated endoscopically again. After a second attempt at hemostasis, a scheduled or emergency endoscopy was done by using the same strategy as in the second-look endoscopy. Patients underwent a third endoscopic hemostatic procedure if necessary. Endoscopic hemostasis was repeated until all exposed vessels with Forrest types Ia, Ib, IIa, or IIb changed to types IIc or III. Emergency surgery or transarterial embolization (TAE), or death due to vascular comorbidities, was also defined as intractable endoscopic hemostasis. Durable hemostasis was defined as a successful hemostatic procedure and the absence of bleeding indicators during hospitalization. We retrospectively documented the patients' age, sex, history of comorbid illnesses, history of UGI ulcers, smoking, alcohol consumption, LDA use with or without antithrombotic drugs, steroid drugs, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), initial hemodynamic status including systolic blood pressure and heart rate, and initial hemoglobin and serum albumin levels. Hemodynamic instability diagnosed as a shock was defined as a systolic blood pressure of <90 mm Hg or a heart rate of >100 beats per minute. We evaluated the ulcer location, size, and number; size of exposed vessels on the bottom of the ulcer; and Forrest bleeding patterns. Bleeding ulcers were located in areas described as the upper (U), middle (M), and lower (L) parts of the stomach, the duodenal bulb (DB), and the second portion of the duodenum (DS), to determine factors associated with bleeding ulcers.

To determine the factors involved in intractability to the initial endoscopic hemostasis, we compared patients whose bleeding UGI ulcers were successfully treated with the hemostasis with those who were intractable.

Statistical analysis

Associations between ulcer-related parameters such as the position, bleeding type, size, and number and size of exposed vessels on the bottom of ulcers, and the background of patients such as sex, age, comorbid illness, a history of UGI ulcers, smoking, alcohol consumption, LDA with or without antithrombotic drugs, steroid drugs and NSAIDs, and intractability to the initial endoscopic hemostasis were initially evaluated by using univariate analysis. Factors with a significant effect on the prevalence of intractability to initial endoscopic hemostatic procedures were identified by using multiple logistic analysis that included parameters with a p-value of <0.1 on univariate regression analysis. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were determined for each variable. All data were statistically analyzed with JMP ver. 9.02 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). A p-value of <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

Prognosis and outcome after endoscopic hemostasis

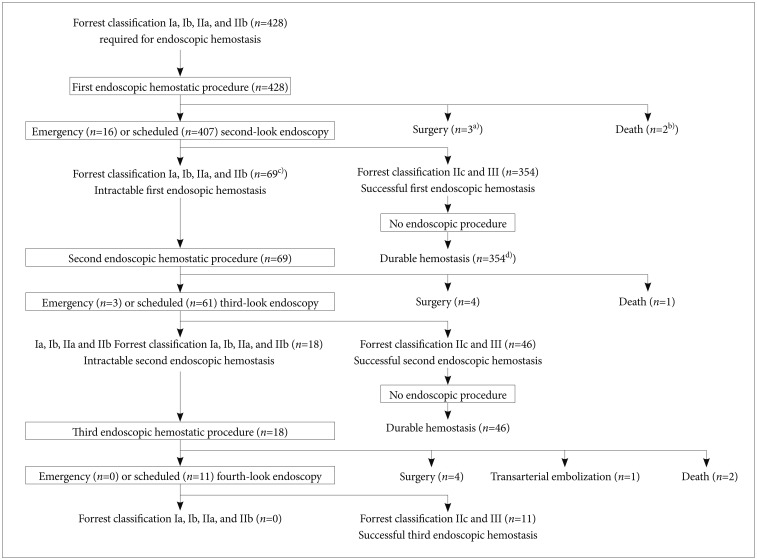

Fig. 1 shows the prognoses of all 428 patients who underwent initial endoscopic hemostasis. Among 423 patients (98.8%) who required an emergency or scheduled second-look endoscopy, the initial endoscopic hemostatic procedure was deemed successful in 354 of them (83.7%) with Forrest type IIc or III, and further endoscopic therapy was not required. Thus, 354 of 428 patients (82.7%) were considered to have durable hemostasis because bleeding did not occur during hospitalization (Fig. 1). In contrast, 69 of 423 patients (16.3%) with Forrest types Ia, Ib, IIa, or IIb who were considered intractable to the initial endoscopic hemostatic procedure at an emergency or scheduled second-look endoscopy required a second endoscopic hemostasis (Fig. 1). Three of 428 patients (0.7%) underwent emergency surgery because the initial endoscopic hemostatic procedure did not stop bleeding from UGI vessels (Fig. 1). Two of 428 patients (0.5%) died of cerebral infarction (Fig. 1). The condition of these two patients worsened soon after initial endoscopic hemostasis, and therefore they were unable to tolerate further procedures such as a second endoscopic hemostasis, surgery, or TAE. Three patients who underwent emergency surgery and the two patients who died were considered intractable to the initial endoscopic hemostasis. After a second endoscopic hemostatic procedure, 46 of 69 patients (66.7%) achieved durable hemostasis; however, 18 of 64 (28.1%) had type Ia, Ib, IIa, and IIb vessels that remained intractable after a second endoscopic hemostatic procedure at an emergency or scheduled third-look endoscopy. These 18 patients required a third endoscopic hemostatic procedure. Four patients underwent surgery because bleeding from UGI vessels did not stop at the second endoscopic hemostatic procedure, and one patient died of myocardial infarction before an emergency or scheduled third-look endoscopy. Of the 18 patients who underwent a third endoscopic hemostatic procedure, 11 achieved durable hemostasis. However, one and four patients were treated with TAE and surgery, respectively, because the third endoscopic hemostatic procedure was incomplete. Two patients died of cerebral infarction before an emergency or scheduled third-look endoscopy. The overall success rate of endoscopic hemostasis was 96.0% (411 of 428 patients). Transarterial embolization and surgery were required for one patient (0.2%) and 11 patients (2.6%), respectively, and five patients (1.2%) died.

Fig. 1.

Prognosis of 428 patients who underwent endoscopic hemostasis. Process of patients and procedures after initial endoscopic hemostasis. a)Three patients underwent emergency surgery because bleeding from vessels associated with upper gastrointestinal did not stop after an initial endoscopic hemostatic procedure. b)Two patients died of cerebral infarction before a scheduled or emergency second-look endoscopy. c)Sixty-nine of 423 patients (16.3%) had Ia, Ib, IIa, or IIb vessels that were considered intractable to the initial endoscopic hemostatic procedure at a scheduled or emergency second-look endoscopy, and they required second endoscopic hemostasis. d)Three hundred fifty-four of 423 patients (83.7%) with Forrest class IIc or III at a scheduled or emergency second-look endoscopy had durable hemostasis. Initial endoscopic hemostatic procedure was considered successful for these patients.

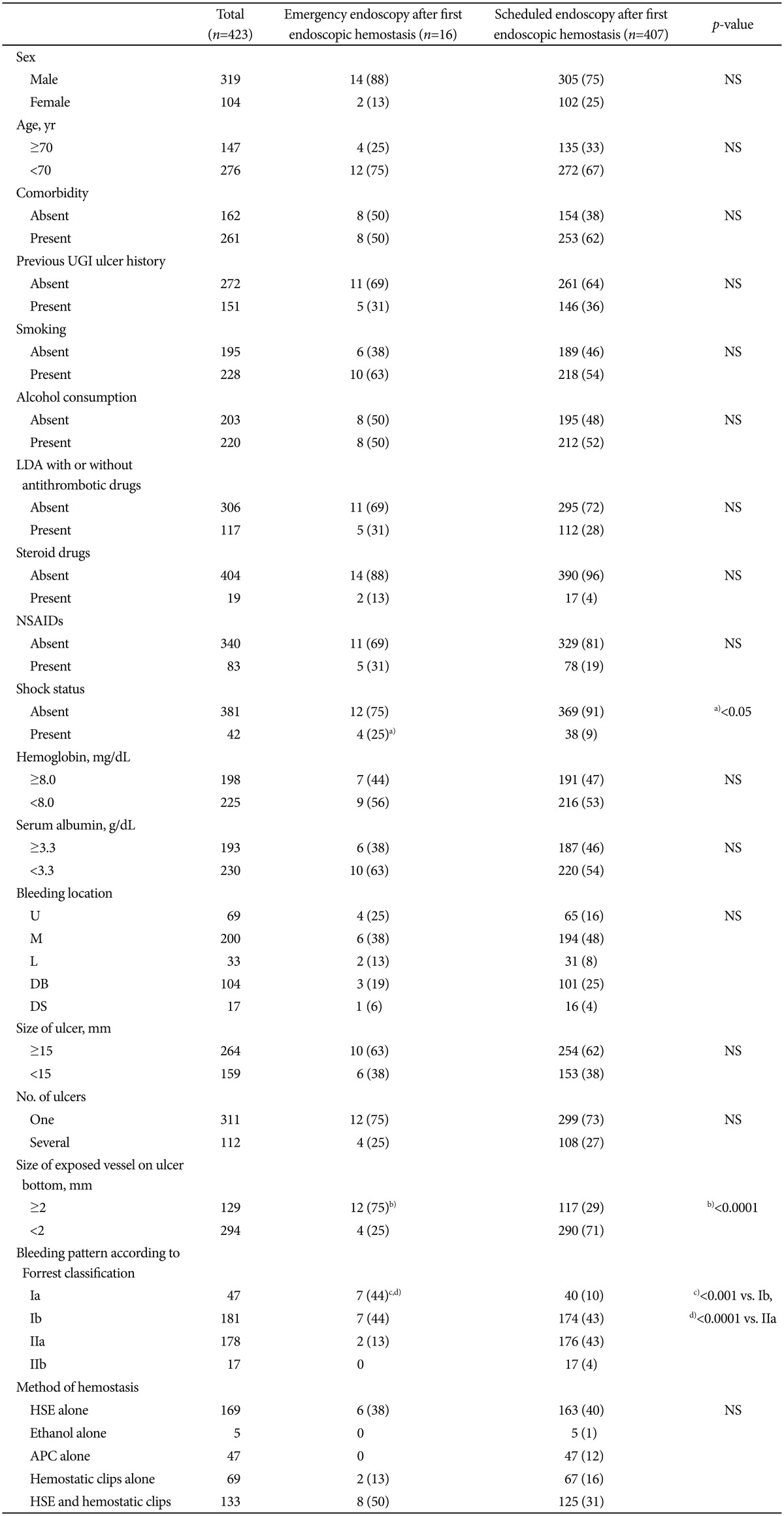

Relation between intractable endoscopic hemostasis and background of patients and ulcer features

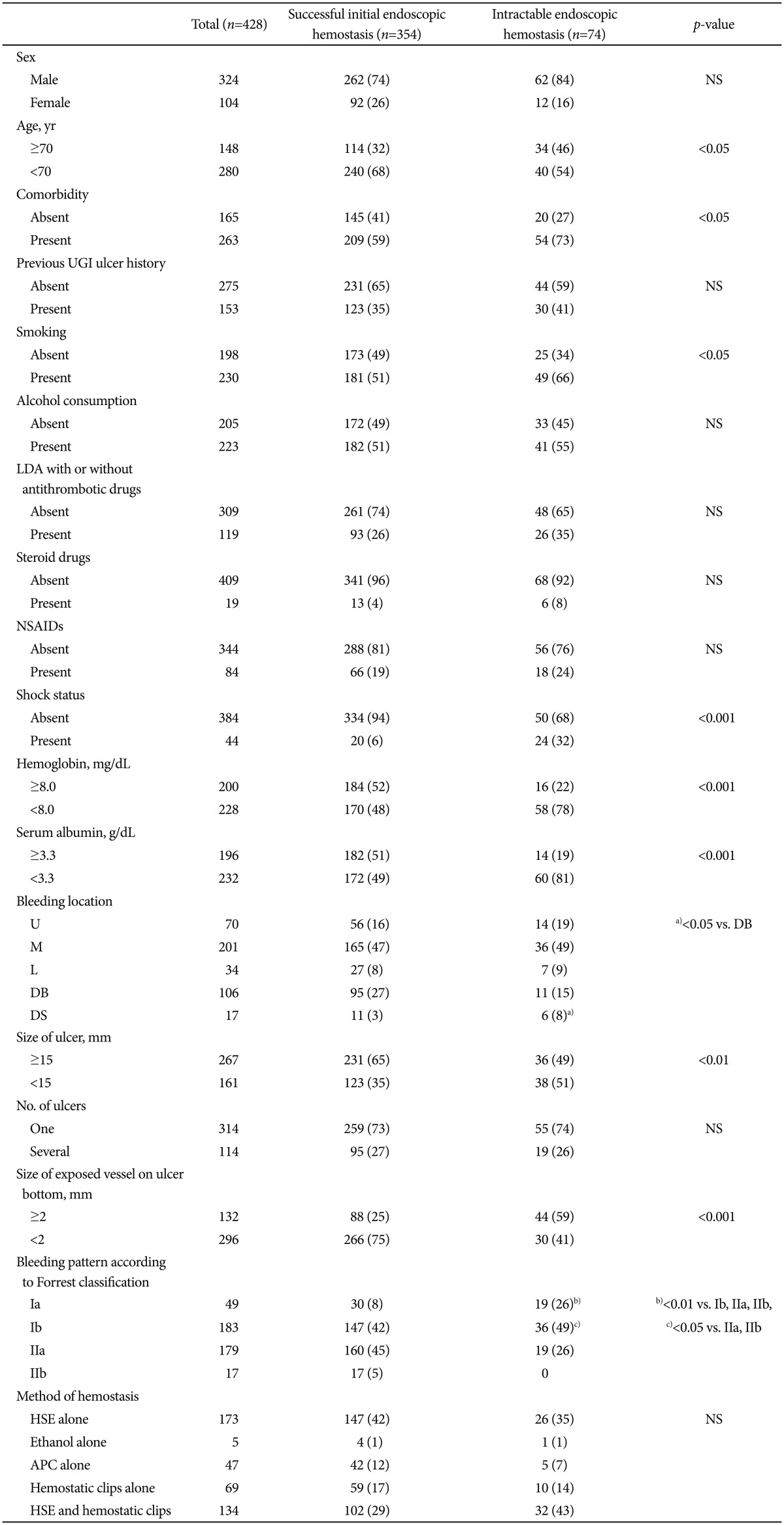

Table 1 shows the hemostatic parameters in the patients' backgrounds and the status of ulcers at the initial endoscopic hemostatic procedure. To determine the risk factors for intractability to endoscopic hemostasis, we assigned the 428 patients into groups according to whether the initial endoscopic hemostasis was successful (durable, n=354) or intractable (n=74) (Table 1, Fig. 1). Univariate analysis significantly related intractable endoscopic hemostasis with age ≥70 years (p<0.05), comorbidity (p<0.05), smoking (p<0.05), shock (p<0.001), hemoglobin <8.0 mg/dL (p<0.001), and serum albumin <3.3 g/dL (p<0.001) (Table 1). Intractable endoscopic hemostasis was also significantly associated with bleeding in the DS (p<0.05 compared with the DB), ulcers ≥15 mm (p<0.01), exposed vessels with a diameter of ≥2 mm on the ulcer bottom (p<0.001), and Forrest bleeding types Ia (p<0.01 vs. Ib, IIa, IIb) and Ib (p<0.05 vs. IIa, IIb), but not with any other factors (Table 1). In addition, bleeding locations comprised the anterior wall (AW); posterior wall (PW); giant curvature; and lesser curvature of the U, M, or L parts of the stomach, AW, PW, superior wall, and inferior wall of the DB, or AW, PW, and the outer and inner walls of the DS. However, bleeding location did not significantly differ between a successful initial and an intractable endoscopic hemostasis.

Table 1.

Univariate Analysis of Hemostatic Parameters, Ulcers and Backgrounds of Patients at Initial Endoscopic Hemostasis

Values are presented as number or number (%).

NS, not significant; UGI, upper gastrointestinal; LDA, low-dose aspirin; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; U, upper parts of the stomach; M, middle parts of the stomach; L, lower parts of the stomach; DB, duodenal bulb; DS, second portion of duodenum; HSE, hypertonic saline-epinephrine solution; APC, argon plasma coagulation.

Intractable endoscopic hemostasis was also significantly associated with bleeding in a)DS (p<0.05 compared with DB), Forrest bleeding types b)Ia (p<0.01 vs. Ib, IIa, IIb) and c)Ib (p<0.05 vs. IIa, IIb).

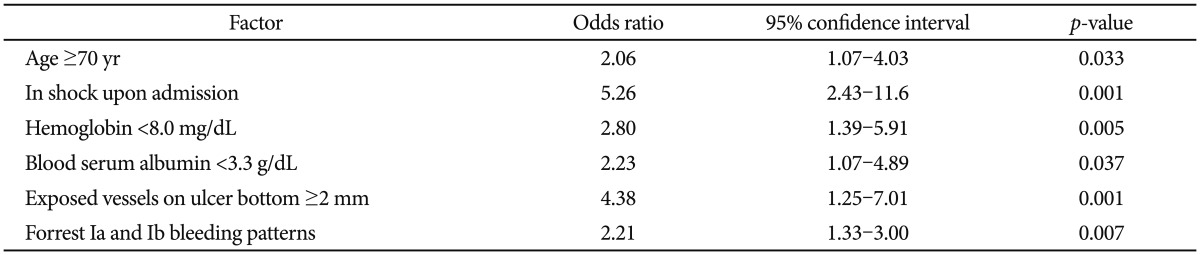

Risk factors for intractability to endoscopic hemostasis determined by using multivariate logistic progression analysis

Multivariate logistic progression analysis indicated that age ≥70 years is a predictor of intractable endoscopic hemostasis (OR, 2.06; 95% CI, 1.07 to 4.03; p=0.033) (Table 2). Hemoglobin <8.0 mg/dL (OR, 2.80; 95% CI, 1.39 to 5.91; p=0.005) and serum albumin <3.3 g/dL (OR, 2.23; 95% CI, 1.07 to 4.89; p=0.037) were also risk factors for intractable endoscopic hemostasis (Table 2). Patients with shock on admission had about a 5-fold higher risk of intractability after the initial endoscopic hemostasis. Having exposed vessels with a diameter of ≥2 mm on the bottom of ulcers (OR, 4.38; 95% CI, 1.25 to 7.01; p=0.001) and Forrest types Ia and Ib bleeding (OR, 2.21; 95% CI, 1.33 to 3.00; p=0.007) were predictors of intractable endoscopic hemostasis (Table 2). Exposed vessels with a diameter of ≥2 mm on the bottom of ulcers were more important predictors of intractability than Forrest types Ia and Ib bleeds.

Table 2.

Multivariate Analysis of Factors Predicting Intractability to Initial Endoscopic Hemostasis

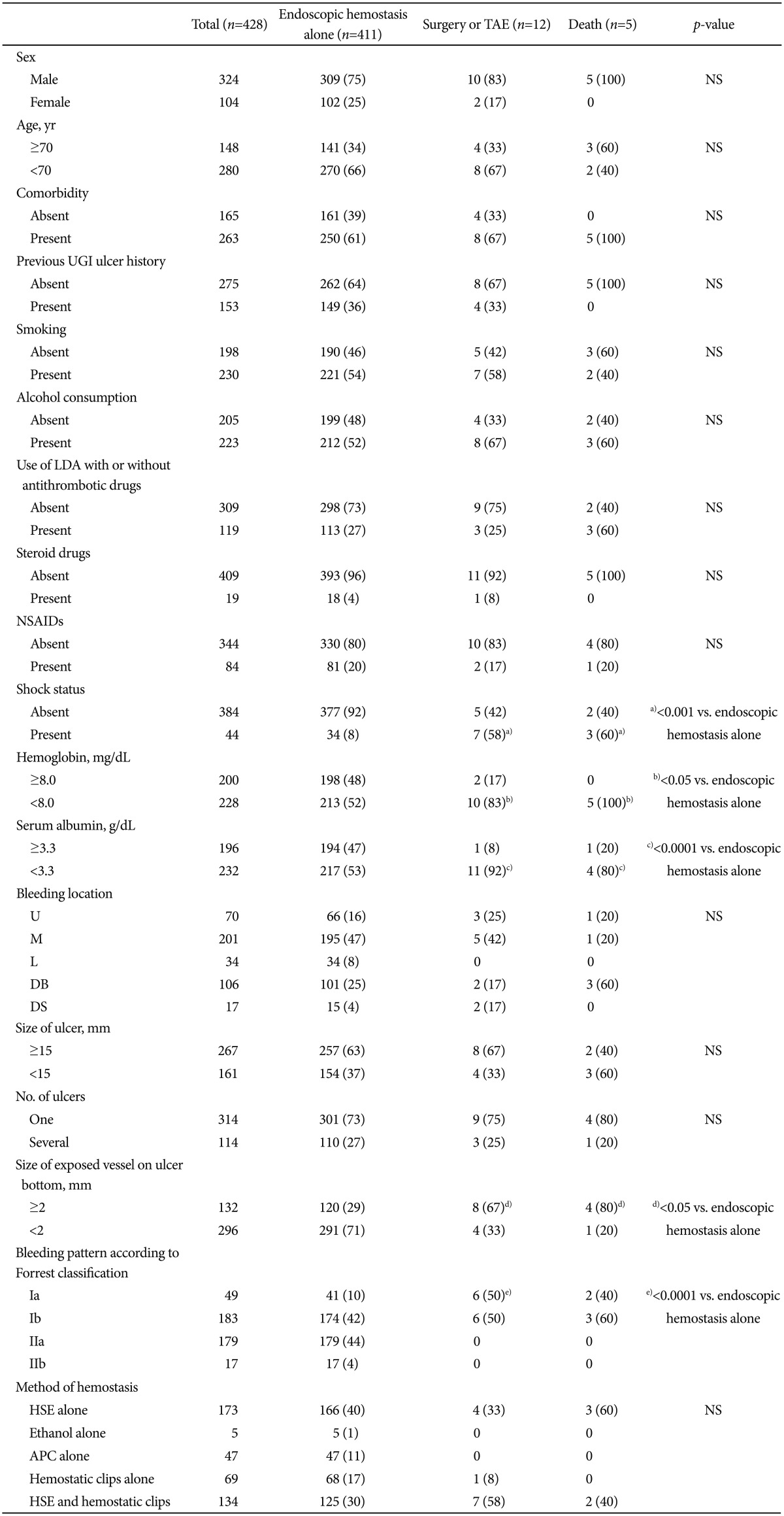

Relation between background and ulcer features among patients treated with endoscopic hemostasis alone, surgery, or TAE, and those who died

Table 3 shows the univariate analysis of the hemostatic parameters, ulcers, and backgrounds of patients according to the prognosis at the initial endoscopic hemostasis. Surgical treatment or TAE (n=12) and death (n=5) were significantly associated with shock (p<0.001 compared with endoscopic hemostasis alone [n=411]), hemoglobin <8.0 mg/dL (p<0.05 vs. endoscopic hemostasis alone), serum albumin <3.3 g/dL (p<0.0001 vs. endoscopic hemostasis alone), and exposed vessels on the ulcer bottom with a diameter of ≥2 mm (p<0.05 vs. endoscopic hemostasis alone). Forrest bleeding type Ia was significantly associated with surgical treatment or TAE (p<0.0001 vs. endoscopic hemostasis alone) and strongly tended to be related to death (p=0.07 vs. endoscopic hemostasis alone). However, multivariate logistic progression analysis did not uncover any predictive factors for prognosis among patients treated with endoscopic hemostasis alone, surgery, or TAE, or those who died.

Table 3.

Univariate Analysis of Hemostatic Parameters, Ulcers and Backgrounds of Patients according to Prognosis at Initial Endoscopic Hemostasis

Values are presented as number or number (%).

TAE, transarterial embolization; NS, not significant; UGI, upper gastrointestinal; LDA, low-dose aspirin; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; U, upper parts of the stomach; M, middle parts of the stomach; L, lower parts of the stomach; DB, duodenal bulb; DS, second portion of duodenum; HSE, hypertonic saline-epinephrine solution; APC, argon plasma coagulation.

Shock status was significantly related to surgical treatment or TAE, and a)death (p<0.001 compared with endoscopic hemostasis alone), b)hemoglobin <8.0 mg/dL (p<0.05 vs. endoscopic hemostasis alone), c)serum albumin <3.3 g/dL (p<0.0001 vs. endoscopic hemostasis alone), and d)exposed vessels with diamaters of ≥2 mm on ulcer bottom (p<0.05 vs. endoscopic hemostasis alone). Forrest bleeding types Ia was significantly associated with patients treated with surgery or e)TAE (p<0.0001 vs. endoscopic hemostasis alone) and had a high tendency to be associated with death (p=0.07 vs. endoscopic hemostasis alone).

Univariate analysis of hemostatic parameters, ulcers, and backgrounds of patients with emergency/scheduled endoscopy after the first endoscopic hemostasis

Univariate analysis was used to assess 423 patients, excluding three who required surgery and two who died after the first endoscopic hemostasis. Sixteen patients (3.8%) and 407 patients (96.2%) underwent an emergency endoscopy and a scheduled endoscopy, respectively, after the first endoscopic hemostasis (Fig. 1). Table 4 shows the outcomes of univariate analysis between the two groups of hemostatic parameters, ulcers, and backgrounds of these patients at the initial endoscopic hemostasis. Emergency endoscopy after the first endoscopic hemostasis was significantly associated with shock (p<0.05), exposed vessels with a diameter of ≥2 mm on the ulcer bottom (p<0.0001), and Forrest bleeding type Ia (p<0.001 compared with Ib, <0.0001 compared with IIa). The results of the risk factors for emergency endoscopy after the first endoscopic hemostasis were similar to those for intractability to endoscopic hemostasis determined by using univariate or multivariate analysis.

Table 4.

Univariate Analysis of Hemostatic Parameters, Ulcers and Backgrounds of Patients with Emergency/Scheduled Endoscopy after First Endoscopic Hemostasis

Values are presented as number or number (%).

NS, not significant; UGI, upper gastrointestinal; LDA, low-dose aspirin; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; U, upper parts of the stomach; M, middle parts of the stomach; L, lower parts of the stomach; DB, duodenal bulb; DS, second portion of duodenum; HSE, hypertonic saline-epinephrine solution; APC, argon plasma coagulation.

Emergency endoscopy after first endoscopic hemostasis significantly associated with a)present shock status (p<0.05), b)size of exposed vessels with diameters ≥2 mm on ulcer bottom (p<0.0001), Forrest bleeding type c)Ia (p<0.001 compared with Ib, d)p<0.0001 compared with IIa).

DISCUSSION

We found that endoscopic hemostasis was a useful initial approach to treating bleeding UGI ulcers, and we identified the risk factors for intractability to this procedure. Among 428 patients with UGI bleeding ulcers treated with immediate endoscopic hemostasis, 354 acquired durable hemostasis, and 74 (17.3%) did not. We used multivariate analysis of data from these groups to evaluate factors associated with intractability to endoscopic hemostasis. The results identified age ≥70 years, shock on admission, hemoglobin <8.0 mg/dL, serum albumin <3.3 g/dL, exposed vessels with a diameter of ≥2 mm on the bottom of ulcers, and Forrest types Ia and Ib bleeds as risk factors for intractability to endoscopic hemostasis.

Several studies have examined risk factors for intractability to endoscopic hemostasis. Rockall et al.13 found that comorbidities such as heart failure, ischemic heart disease, and renal failure were factors indicating a high risk for rebleeding. A systematic review of 10 articles14 revealed that predictors for rebleeding after endoscopic hemostasis comprised hemodynamic instability, comorbidity, active bleeding, and large ulcers. We found here that hemodynamic instability presenting as shock and active bleeding presenting as Forrest types Ia and Ib bleeding were predictors of intractability to endoscopic hemostasis. Our results therefore agreed with the reported findings.14 However, comorbid illness was not a risk factor for intractability to endoscopic hemostasis, which differed from previous findings.14,15 The reason for this might be associated with the strategies used to achieve hemostasis and that the number of hemostatic approaches was limited in the published clinical trial.14 We found that patients aged ≥70 years and hemoglobin <8.0 mg/dL were also independent risk factors for intractability to endoscopic hemostasis. These findings are broadly compatible with those of three other studies.16,17,18 Previous evaluations of risk factors among patients with nonvariceal UGI bleeding, by using multivariate analysis, included age >65 years16 and low initial hemoglobin values among the clinical predictors of increased risk for persistent or recurrent bleeding.17,18 Many patients are administered with LDA as an antithrombotic therapy for the secondary prevention of cerebral and/or myocardial vascular events. However, LDA intake is considered an important risk factor for UGI bleeding, as the relative risk is about 2-fold higher and it is not related to either the formulation (plain or entericcoated) or dosage of LDA.19 Among 119 of our patients who were administered with LDA, 26 (21.8%) were intractable to the initial endoscopic hemostasis. However, LDA, steroids, and NSAIDs were not risk factors for intractability to endoscopic hemostasis, which agreed with previous findings.20,21,22 Serum albumin <3.3 g/dL was a predictor of intractable endoscopic hemostasis. Hypoalbuminemia might reflect a reduction in serum coagulation factors. Both hypoalbuminemia and a loss of serum coagulation factors might delay mucosal healing after injury and result in intractability to endoscopic hemostasis. We believe that serum albumin <3.3 g/dL is a novel predictor of intractable endoscopic hemostasis for UGI bleeding ulcers. Vessels with a diameter of ≥2 mm exposed on the bottom of ulcers also predicted intractable endoscopic hemostasis. Precisely treating large exposed vessels with hemostasis is generally difficult, and HSE injection, APC, and hemostatic clips might be insufficient. Thus, larger exposed vessels might not disappear so rapidly after endoscopic hemostasis, resulting in intractability. Although a systematic review related endoscopic hemostatic intractability with bleeding location, such as posterior duodenal or lesser gastric curve ulcers,14 we found that bleeding locations did not significantly differ between a successful initial and an intractable endoscopic hemostasis. That might be because both the skill of those implementing the endoscopic hemostatic procedures and the devices used for endoscopic hemostasis have improved recently. Therefore, mature endoscopic hemostasis would reduce the likelihood of a relation between bleeding location and endoscopic hemostatic intractability.

Since various factors contribute to intractability, careful observation after endoscopic hemostasis is needed, particularly for patients at a high risk for incomplete hemostasis. Our patients with Forrest types IIc and III never underwent additional further endoscopic hemostasis, and none of them developed symptoms of rebleeding during hospitalization. These results indicated that types IIc and III vessels do not require treatment with endoscopic hemostasis. Diagnosing vessels on UGI ulcers based on the Forrest classification might avoid ineffective endoscopic treatment and unnecessary observational endoscopy, and thus reduce medical care expenses.

Recently, TAE has been considered as an alternative to salvage surgery. Some retrospective studies have compared TAE with surgery in patients for whom endoscopic treatment failed.23,24,25,26,27 All of these studies found that TAE reduced the number of complications and the need for surgery without increasing overall mortality. Although several studies have demonstrated that TAE is useful for treating acute hemorrhage from UGI ulcers,28,29,30 the choice of TAE or surgery after a failed endoscopic treatment depended on the discretion of the operating surgeon or physician. Moreover, the selection of TAE or surgery after a failed endoscopic treatment might also be affected by institutional TAE limitations. We attempted TAE in only one patient for whom a third endoscopic hemostasis failed. This was a limitation of treatment for bleeding UGI ulcers at Aichi Medical University Hospital.

In conclusion, age ≥70 years, shock on hospital admission, hemoglobin <8.0 mg/dL, serum albumin <3.3 g/dL, exposed vessels with a diameter of ≥2 mm on the ulcer bottom, and Forrest types Ia and Ib bleeds were identified as independent risk factors associated with an intractable initial endoscopic hemostasis in patients with peptic UGI bleeds. Additional studies are required to validate our results and document the impact of initial risk stratification for intractability to endoscopic hemostasis for the emergency management of UGI bleeding.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Derry S, Loke YK. Risk of gastrointestinal haemorrhage with long term use of aspirin: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2000;321:1183–1187. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7270.1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakayama M, Iwakiri R, Hara M, et al. Low-dose aspirin is a prominent cause of bleeding ulcers in patients who underwent emergency endoscopy. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:912–918. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0074-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Selection of patients for early discharge or outpatient care after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. National Audit of Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage. Lancet. 1996;347:1138–1140. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90607-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barkun A, Sabbah S, Enns R, et al. The Canadian Registry on Nonvariceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding and Endoscopy (RUGBE): Endoscopic hemostasis and proton pump inhibition are associated with improved outcomes in a real-life setting. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1238–1246. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramsoekh D, van Leerdam ME, Rauws EA, Tytgat GN. Outcome of peptic ulcer bleeding, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, and Helicobacter pylori infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:859–864. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00402-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Leerdam ME, Vreeburg EM, Rauws EA, et al. Acute upper GI bleeding: did anything change? Time trend analysis of incidence and outcome of acute upper GI bleeding between 1993/1994 and 2000. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1494–1499. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silverstein FE, Gilbert DA, Tedesco FJ, Buenger NK, Persing J. The national ASGE survey on upper gastrointestinal bleeding. II. Clinical prognostic factors. Gastrointest Endosc. 1981;27:80–93. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(81)73156-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forrest JA, Finlayson ND, Shearman DJ. Endoscopy in gastrointestinal bleeding. Lancet. 1974;2:394–397. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)91770-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ikeda Y, Takakuwa R, Hatakeyama H, et al. Evaluation of endoscopic local injection of hypertonic saline-epinephrine solution and surgical treatment on hemorrhagic gastroduodenal ulcer. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1989;90:1545–1547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cipolletta L, Bianco MA, Rotondano G, Piscopo R, Prisco A, Garofano ML. Prospective comparison of argon plasma coagulator and heater probe in the endoscopic treatment of major peptic ulcer bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:191–195. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70163-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishiaki M, Tada M, Yanai H, Tokiyama H, Nakamura H, Okita K. Endoscopic hemostasis for bleeding peptic ulcer using a hemostatic clip or pure ethanol injection. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:1042–1044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hachisu T. Evaluation of endoscopic hemostasis using an improved clipping apparatus. Surg Endosc. 1988;2:13–17. doi: 10.1007/BF00591392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Risk assessment after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Gut. 1996;38:316–321. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.3.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elmunzer BJ, Young SD, Inadomi JM, Schoenfeld P, Laine L. Systematic review of the predictors of recurrent hemorrhage after endoscopic hemostatic therapy for bleeding peptic ulcers. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2625–2632. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Urayama N, Shiraishi K, Aoyama K, et al. Factors predicting incomplete endoscopic hemostasis in bleeding gastroduodenal ulcers. Hepatogastroenterology. 2010;57:519–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaramillo JL, Galvez C, Carmona C, Montero JL, Mino G. Prediction of further hemorrhage in bleeding peptic ulcer. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:2135–2138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin HJ, Wang K, Perng CL, Lee FY, Lee CH, Lee SD. Natural history of bleeding peptic ulcers with a tightly adherent blood clot: a prospective observation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43:470–473. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(96)70288-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng CL, Lin CH, Kuo CJ, et al. Predictors of rebleeding and mortality in patients with high-risk bleeding peptic ulcers. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2577–2583. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-1093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Abajo FJ, Garcia Rodriguez LA. Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation associated with low-dose aspirin as plain and enteric-coated formulations. BMC Clin Pharmacol. 2001;1:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6904-1-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brullet E, Calvet X, Campo R, Rue M, Catot L, Donoso L. Factors predicting failure of endoscopic injection therapy in bleeding duodenal ulcer. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43(2 Pt 1):111–116. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(06)80110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chung IK, Kim EJ, Lee MS, et al. Endoscopic factors predisposing to rebleeding following endoscopic hemostasis in bleeding peptic ulcers. Endoscopy. 2001;33:969–975. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-17951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong SK, Yu LM, Lau JY, et al. Prediction of therapeutic failure after adrenaline injection plus heater probe treatment in patients with bleeding peptic ulcer. Gut. 2002;50:322–325. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.3.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eriksson LG, Ljungdahl M, Sundbom M, Nyman R. Transcatheter arterial embolization versus surgery in the treatment of upper gastrointestinal bleeding after therapeutic endoscopy failure. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19:1413–1418. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2008.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ripoll C, Banares R, Beceiro I, et al. Comparison of transcatheter arterial embolization and surgery for treatment of bleeding peptic ulcer after endoscopic treatment failure. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;15:447–450. doi: 10.1097/01.rvi.0000126813.89981.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Venclauskas L, Bratlie SO, Zachrisson K, Maleckas A, Pundzius J, Jonson C. Is transcatheter arterial embolization a safer alternative than surgery when endoscopic therapy fails in bleeding duodenal ulcer? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:299–304. doi: 10.3109/00365520903486109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong TC, Wong KT, Chiu PW, et al. A comparison of angiographic embolization with surgery after failed endoscopic hemostasis to bleeding peptic ulcers. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:900–908. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larssen L, Moger T, Bjornbeth BA, Lygren I, Klow NE. Transcatheter arterial embolization in the management of bleeding duodenal ulcers: a 5.5-year retrospective study of treatment and outcome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:217–222. doi: 10.1080/00365520701676443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ljungdahl M, Eriksson LG, Nyman R, Gustavsson S. Arterial embolisation in management of massive bleeding from gastric and duodenal ulcers. Eur J Surg. 2002;168:384–390. doi: 10.1080/110241502320789050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holme JB, Nielsen DT, Funch-Jensen P, Mortensen FV. Transcatheter arterial embolization in patients with bleeding duodenal ulcer: an alternative to surgery. Acta Radiol. 2006;47:244–247. doi: 10.1080/02841850600550690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katano T, Mizoshita T, Senoo K, et al. The efficacy of transcatheter arterial embolization as the first-choice treatment after failure of endoscopic hemostasis and endoscopic treatment resistance factors. Dig Endosc. 2012;24:364–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2012.01285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]